Abstract

Progress in therapy has made survival into adulthood a reality for most children, adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer today. Notably, this growing population remains vulnerable to a variety of long-term therapy-related sequelae. Systematic ongoing follow-up of these patients is, therefore, important to provide for early detection of and intervention for potentially serious late-onset complications. In addition, health counseling and promotion of healthy lifestyles are important aspects of long-term follow-up care to promote risk reduction for health problems that commonly present during adulthood. Both general and subspecialty pediatric health care providers are playing an increasingly important role in the ongoing care of childhood cancer survivors, beyond the routine preventive care, health supervision, and anticipatory guidance provided to all patients. This report is based on the guidelines that have been developed by the Children’s Oncology Group to facilitate comprehensive long-term follow-up of childhood cancer survivors (www.survivorshipguidelines.org).

Keywords: childhood cancer, treatment, survival, late effects, guidelines, long-term follow-up

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is diagnosed in approximately 12 400 children and adolescents younger than 20 years each year in the United States.1 Before 1970, almost all children with cancer died from their primary disease. However, rapid improvements in multimodal treatment regimens (chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgery), coupled with aggressive supportive-care regimens, have resulted in survival rates that continue to increase at a fast pace. The current overall survival rate for childhood malignancies is estimated at 79%.2 This translates into approximately 300 000 childhood cancer survivors now in the United States, many of whom may seek ongoing care from pediatricians and other pediatric subspecialty providers.3 As the number of childhood cancer survivors continues to grow, there is a concomitant increase in the number of survivors being cared for in the primary care setting. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS), the largest and most extensively characterized cohort of 5-year childhood cancer survivors in North America, reported that survivors receive most of their care from primary care providers.4 Furthermore, the proportion of survivors reporting a cancer-related visit decreases with increasing time from cancer diagnosis. Thus, the general pediatrician is likely to have an increasingly vital role in caring for this rapidly growing population.

Cancer and its treatment may result in a variety of physical and psychosocial effects that predispose childhood cancer survivors to excess morbidity and early mortality when compared with the general population.5-12 Virtually every organ system can be affected by the chemotherapy, radiation, and/or surgery required to achieve cure of pediatric malignancies. Late complications of treatment may include problems with organ function, growth and development, neurocognitive function and academic achievement, and the potential for additional cancers. Cancer and its treatment also have psychosocial consequences that may adversely affect family/peer relationships, vocational and employment opportunities, and insurance and health care access. A child’s life is forever changed when touched by the cancer experience, and it is critical to assist the child and his or her family with rehabilitation into a society that places high value on good health and proper performance. Moreover, late effects after childhood cancer are common. Two of every 3 childhood cancer survivors will develop at least one late-onset therapy-related complication; in 1 of every 4 cases, the complication will be severe or life threatening.13 Childhood cancer survivors, therefore, require ongoing comprehensive long-term follow-up care to optimize long-term outcomes by successfully monitoring for and treating the late effects that may occur as a result of previous cancer therapies.

Because health risks associated with cancer are unique to the age at treatment and specific therapeutic modality, follow-up evaluations and health screening should be individualized on the basis of treatment history. To facilitate comprehensive and systematic follow-up of childhood cancer survivors, the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) organized exposure-based health screening guidelines. This clinical report presents the pediatrician with guidance in providing high-quality long-term follow-up care and health supervision for survivors of pediatric malignancies by incorporating long-term follow-up guidelines developed by the COG into their practice14 and by maintaining ongoing interaction with pediatric oncology subspecialists to facilitate communication regarding any changes in follow-up recommendations specific to the childhood cancer survivors under their care.

METHODS: DEVELOPMENT OF LONG-TERM FOLLOW-UP GUIDELINES

The COG is a cooperative clinical trials group supported by the National Cancer Institute with more than 200 member institutions. In January 2002, at the request of the Institute of Medicine, a multidisciplinary panel within COG initiated the process of developing comprehensive risk-based, exposure-related recommendations for screening and management of late treatment-related complications potentially resulting from therapy for childhood cancers. The resulting comprehensive resource, the Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers (COG LTFU Guidelines),14 is designed to raise awareness of the risk of late treatment-related sequelae to facilitate early identification and intervention for these complications, standardize follow-up care, improve quality of life, and provide guidance to health care professionals, including pediatricians, who supervise the ongoing care of childhood cancer survivors.

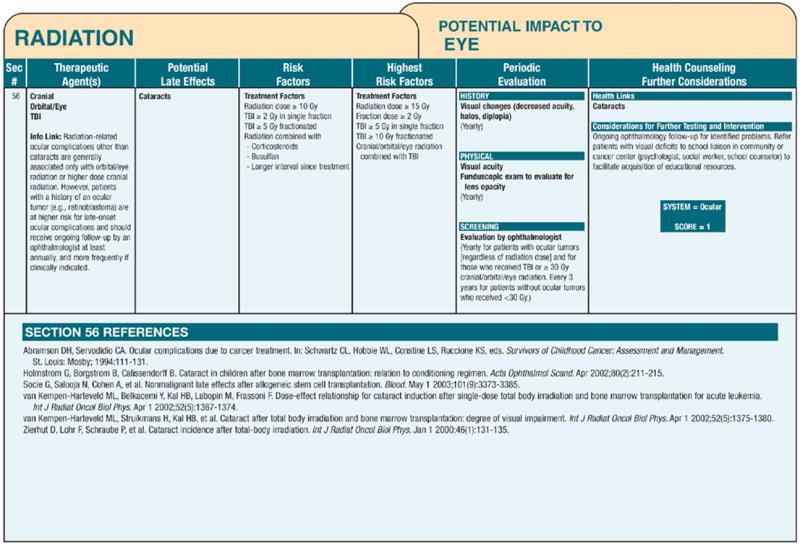

The methodology used in developing these guidelines has been described elsewhere.15 Briefly, evidence for development of the COG LTFU Guidelines was collected by conducting a complete search of the medical literature for the previous 20 years via MEDLINE. After the screening recommendations were developed, a multidisciplinary panel (including experts from pediatric oncology and other pediatric subspecialties, nursing, radiation oncology, behavioral medicine, and patient advocacy) reviewed and revised the guidelines. A panel of experts in the late effects of childhood and adolescent cancer treatment then reviewed and scored the guidelines using a modified version of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network “Categories of Consensus” system.16 Each score reflects the strength of data from the literature linking specific late complications with therapeutic exposures, coupled with an assessment of the appropriateness of screening recommendations on the basis of collective clinical experience of the expert panel. The COG LTFU Guidelines are, therefore, a hybrid of evidence-based and consensus-driven approaches to guideline development. Task forces within COG monitor the literature on an ongoing basis and provide recommendations for guideline revision as new information becomes available. These task forces include general pediatricians and other primary care providers to incorporate a primary care perspective and facilitate effective dissemination of these guidelines into the “real-world” setting. Table 1 provides a summary of selected treatment exposures and associated late effects by organ system as outlined in the COG LTFU Guidelines. Fig 1 provides an example of an exposure-based recommendation from the COG LTFU Guidelines.

Table 1.

Potential Late Effects of Selected Therapeutic Interventions for Childhood Cancer by Organ System

| Organ System | Therapeutic Exposures | Potential Late Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy | Radiation therapy field(s) | Surgery | ||

| Skin | -- | All fields | -- | Dysplastic nevi Skin cancer |

| Ocular | Busulfan Corticosteroids |

Cranial Orbital/eye TBI |

Neurosurgery | Cataracts Retinopathy (XRT doses ≥30 Gy only) Ocular nerve palsy (neurosurgery only) |

| Auditory | Cisplatin Carboplatin (in myeloablative doses only) |

≥30 Gy to: - Cranial - Ear/infratemporal - Nasopharyngeal |

-- | Sensorineural hearing loss Conductive hearing loss (XRT only) Eustachian tube dysfunction (XRT only) |

| Dental | Any chemotherapy before development of secondary dentition | Head and neck fields that include the oral cavity or salivary glands (eg, cranial, oropharyngeal, mantle, TBI) | -- | Dental maldevelopment (tooth/root agenesis, microdontia, enamel dysplasia) Periodontal disease Dental caries Osteoradionecrosis (XRT doses ≥40 Gy) |

| Cardiovascular | Anthracycline agents (eg, doxorubicin, daunorubicin) | Chest (eg, mantle, mediastinal) Upper abdominal |

-- | Cardiomyopathy Congestive heart failure Arrhythmia Subclinical left ventricular dysfunction XRT only: - Valvular disease - Atherosclerotic heart disease - Myocardial infarction - Pericarditis, pericardial fibrosis |

| Pulmonary | Bleomycin Busulfan Carmustine Lomustine |

Chest (mantle, mediastinal, whole lung) TBI |

Pulmonary resection Lobectomy |

Pulmonary fibrosis Interstitial pneumonitis Restrictive/obstructive lung disease Pulmonary dysfunction |

| Breast | -- | Chest (mantle, mediastinal, axillary, whole lung, TBI) | -- | Breast tissue hypoplasia Breast cancer (XRT doses ≥20 Gy) |

| Gastrointestinal | -- | Abdominal, pelvic (doses ≥30 Gy) | Laparotomy Pelvic/spinal surgery |

Chronic enterocolitis GI tract strictures Adhesions/obstruction Fecal incontinence Colon cancer (XRT only; doses ≥30 Gy) |

| Liver | Antimetabolites (mercaptopurine, thioguanine, methotrexate) | Abdominal (doses ≥30 Gy) | -- | Hepatic dysfunction Veno-occlusive disease (VOD) Hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis Cholelithiasis |

| Renal | Cisplatin Carboplatin Ifosfamide Methotrexate |

Abdominal (including kidney) | Nephrectomy | Glomerular toxicity Tubular dysfunction Renal insufficiency Hypertension |

| Bladder | Cyclophosphamide Ifosfamide | Pelvic (including bladder) Lumbar-sacral spine |

Spinal surgery Cystectomy |

Hemorrhagic cystitis Bladder fibrosis Dysfunctional voiding Neurogenic bladder Bladder malignancy (cyclophosphamide, XRT) |

| Sexual/reproductive (males) | Alkylating agents (eg, busulfan, carmustine, lomustine, cyclophosphamide, mechlorethamine, melphalan, procarbazine) | Hypothalamic-pituitary Testicular Pelvic TBI |

Pelvic/spinal surgery Orchiectomy |

Delayed/arrested puberty Hypogonadism Infertility Erectile/ejaculatory dysfunction |

| Sexual/reproductive (females) | Alkylating agents (eg, busulfan, carmustine, lomustine, cyclophosphamide, mechlorethamine, melphalan, procarbazine) | Hypothalamic-pituitary Pelvic Ovarian Lumbar-sacral spine TBI |

Oophorectomy | Delayed/arrested puberty Premature menopause Infertility Uterine vascular insufficiency (XRT only) Vaginal fibrosis/stenosis (XRT only) |

| Endocrine/metabolic | -- | Hypothalamic-pituitary Neck (thyroid) |

Thyroidectomy | Growth hormone deficiency Precocious puberty Hypothyroidism Thyroid nodules/cancer XRT doses ≥40 Gy: Hyperprolactinemia Central adrenal insufficiency Gonadotropin deficiency Hyperthyroidism |

| Musculoskeletal | Corticosteroids Methotrexate |

-- | -- | Osteopenia/osteoporosis Osteonecrosis |

| -- | All fields | -- | Reduced/uneven growth Reduced function/mobility Hypoplasia, fibrosis Radiation-induced fracture (doses ≥40 Gy) Scoliosis/kyphosis (trunk fields only) Secondary benign or malignant neoplasms |

|

| -- | -- | Amputation Limb sparing |

Reduced/uneven growth Reduced function/mobility |

|

| Neurocognitive | Methotrexate (intrathecal administration or IV doses ≥1000 mg/m2) Cytarabine (IV doses ≥1000 mg/m2) |

Cranial Ear/infratemporal Total body irradiation |

Neurosurgery | Neurocognitive deficits (executive function, attention, memory, processing speed, visual motor integration) Learning deficits Diminished IQ |

| Central nervous system | Methotrexate, cytarabine (intrathecal administration or IV doses ≥1000 mg/m2) | Doses ≥40 Gy to: Cranial Orbital/eye Ear/infratemporal Nasopharyngeal |

Neurosurgery | Leukoencephalopathy (spasticity, ataxia, dysarthria, dysphagia, hemiparesis, seizures [chemotherapy and XRT]) Motor and sensory deficits Cerebrovascular complications (stroke, moya moya, occlusive cerebral vasculopathy [XRT and surgery]) Brain tumor (any XRT dose) |

| Peripheral nervous system | Plant alkaloids (vincristine, vinblastine) Cisplatin, carboplatin |

-- | Spinal surgery | Peripheral sensory or motor neuropathy |

| Immunologic | Abdomen, left upper quadrant, spleen (doses ≥40 Gy) | Splenectomy | Life-threatening infection related to functional or anatomic asplenia Note: Functional asplenia can also occur as a consequence of active chronic graft-versus-host disease following hematopoietic stem cell transplant |

|

| Psychosocial | Any | Any | Any | Social withdrawal, educational problems, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress |

Gy = Gray; XRT = radiation therapy; TBI = total body irradiation; IV = intravenous

Note: This table briefly summarizes potential late effects for selected therapeutic exposures only; the complete set of Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines from the Children’s Oncology Group, including screening recommendations, is available at www.survivorshipguidelines.org.

Fig 1.

Example of an exposure-based recommendation from the COG LTFU Guidelines.

The COG LTFU Guidelines are designed for use in asymptomatic survivors presenting for routine health maintenance at least 2 years after completion of therapy.15 They are not designed for disease-related surveillance, which generally continues under the guidance of the treating oncologist throughout the period when the patient remains at risk of relapse from his or her primary disease. This period of risk varies depending on diagnosis and is generally highest in the first few years, with the risk decreasing significantly as time from diagnosis lengthens.

CLINICAL APPLICATION OF THE COG LTFU GUIDELINES

Malignancies presenting in the pediatric age range encompass a spectrum of diverse histological subtypes that have been managed with heterogeneous and evolving treatment approaches. Over the last 20 years, treatment protocols for localized and biologically favorable presentations of pediatric cancers have been modified substantially to reduce the risk of therapy-related complications. Conversely, therapy has been intensified for many advanced and biologically unfavorable pediatric cancers to optimize disease control and long-term survival. Thus, not all childhood cancer survivors have similar risks of late treatment effects, including those with the same diagnosis. The diversity and potential interplay of factors contributing to cancer-related morbidity are illustrated in the case presentations summarized in Table 2. In general, the risk of late effects is directly proportional to the intensity of therapy required to achieve and maintain disease control. Longer treatment with higher cumulative doses of chemotherapy and radiation, multimodal therapy, and relapse therapy increase the risk of late treatment effects. Specifically, the risk of late effects is related to the type and intensity of cancer therapy (eg, surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation) and the patient’s age at the time of treatment. Chemotherapy most often results in acute effects, some of which may persist and cause problems as the survivor ages. Many radiation-related effects on growth and development, organ function, and carcinogenesis may not manifest until many years after cancer treatment. The young child is especially at risk of delayed treatment toxicity affecting linear growth, skeletal maturation, intellectual function, sexual development, and organ function. Because pediatricians provide care across a continuum of developmental periods, they must also recognize that childhood cancer survivors face unique vulnerabilities related to their age at diagnosis and treatment.

Table 2.

Examples of 2 Survivors: Factors Contributing to Cancer-Related Morbidity

| Factor | Example 1. Leukemia | Example 2. Solid tumor |

|---|---|---|

| Host | 3-year-old white male | 16-year-old black female |

| Tumor | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, B lineage, average risk, without CNS involvement | Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the chest wall, stage II |

| Treatment | Vincristine | Vincristine |

| Corticosteroids | Dactinomycin | |

| Antimetabolites (PO, IV, intrathecal) | Chest radiation (36 Gy) | |

| Asparaginase | ||

| Cyclophosphamide (moderate dose) | ||

| Doxorubicin (low dose) | ||

| Potential late effects | Peripheral neuropathy | Peripheral neuropathy |

| Osteopenia/osteoporosis | Cardiac complications (cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, arrhythmia, subclinical left ventricular dysfunction, valvular disease, atherosclerotic heart disease, myocardial infarction, pericarditis, pericardial fibrosis) | |

| Osteonecrosis | Pulmonary complications (fibrosis, interstitial pneumonitis, restrictive/obstructive lung disease) | |

| Cataracts | Esophageal stricture | |

| Hepatic dysfunction | Breast tissue hypoplasia | |

| Renal insufficiency | Breast cancer | |

| Neurocognitive deficits | Scoliosis/kyphosis | |

| Leukoencephalopathy | Shortened trunk height | |

| Hemorrhagic cystitis, bladder malignancy | Secondary benign or malignant neoplasms in radiation field | |

| Secondary myelodysplasia or myeloid leukemia | ||

| Gonadal dysfunction | ||

| Cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, arrhythmia | ||

| Dental maldevelopment, periodontal disease, excessive dental caries | ||

| Genetics/familial | Diabetes mellitus, type 2 | Hypertension |

| Early coronary artery disease | ||

| Comorbid conditions | Obesity | Hypertension |

| Health behaviors | Sedentary lifestyle | Smoker |

| Aging | Bone mineral (osteoporosis) | Cardiomyopathy |

CNS indicates central nervous system; PO, oral; IV, intravenous; Gy, Gray.

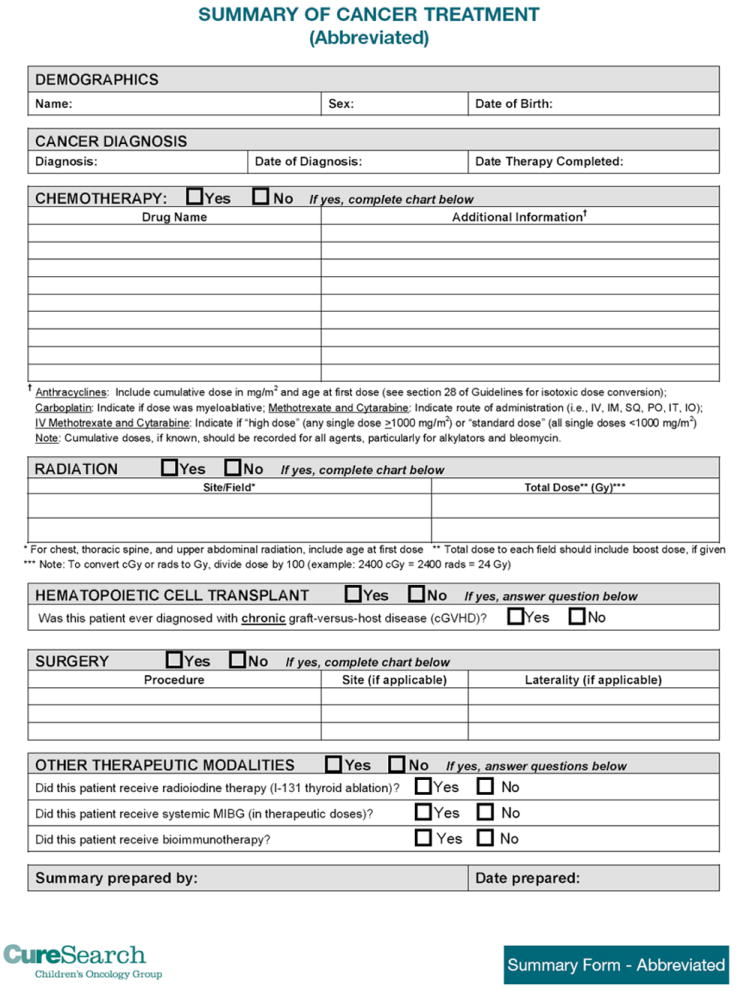

Risk-based care involving a systematic plan for lifelong screening, surveillance, and prevention that incorporates risks on the basis of previous cancer, cancer therapy, genetic predispositions, lifestyle behaviors, and comorbid health conditions is recommended for all survivors.10,17 Information critical to the coordination of risk-based care includes the date of cancer diagnosis, cancer histology, organs/tissues affected by cancer, and specific treatment modalities such as surgical procedures, chemotherapeutic agents, and radiation treatment fields and doses and history of bone marrow or stem cell transplant and blood product transfusion. Knowledge of cumulative chemotherapy dosages (eg, for anthracycline agents), or dose intensity of administration (eg, for methotrexate), also is important in estimating risk and screening frequency. This pertinent clinical information can be organized into a treatment summary that interfaces with the COG LTFU Guidelines to facilitate identification of potential late complications and recommended follow-up care (Fig 2). Because of the diversity and complexity of pediatric cancer therapies, the treating pediatric oncology center represents the optimal resource for this treatment information. Furthermore, the need for ongoing, open lines of communication between the pediatric cancer center and the primary care provider is critical.

Fig 2.

Sample template for cancer treatment summary containing essential data elements necessary for generating long-term follow-up guidelines.

Coordination of risk-based care for childhood cancer survivors requires a working knowledge about cancer-related health risks and appropriate screening evaluations, or access to a resource that contains this information. Individualized recommendations for long-term follow-up care of childhood cancer survivors can be customized from the COG LTFU Guidelines on the basis of each patient’s treatment history, age, and gender into a “survivorship care plan” that is ideally developed by, or in coordination with, the pediatric oncology subspecialist. In addition, the COG LTFU Guidelines provide information to assist with risk stratification, allowing the health care provider to address specific treatment-related health risks that may be magnified in individual patients because of familial or genetic predisposition, sociodemographic factors, or maladaptive health behaviors. The patient education materials, known as “Health Links,” that accompany the COG LTFU Guidelines, are specifically tailored to enhance health supervision and promotion in this population by providing simplified explanations of guideline-specific topics in lay language.18 The COG LTFU Guidelines, associated patient education materials, and supplemental resources to enhance guideline application, including clinical summary templates, can be downloaded from www.survivorshipguidelines.org. A Web-based platform that will allow online generation of therapeutic summaries with simultaneous output of patient-specific guidelines on the basis of exposure history, age, and gender is currently under development.19

DISCUSSION/RECOMMENDATIONS

Pediatricians are uniquely qualified to deliver ongoing health care to childhood cancer survivors, because they are already familiar with health maintenance and supervision for healthy children and adolescents and also provide care for patients with complex chronic medical conditions. The concept of the “medical home” has been endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics as an effective model for coordinating the complex health care requirements of children with special needs, such as childhood cancer survivors, to provide care and preventive services that are accessible, continuous, comprehensive, family centered, coordinated, compassionate, and culturally effective.20,21 Within this framework, the pediatrician is able to view the cancer survivor in the context of the family and to assist not only the survivor but also the parents and siblings in adapting to the “new normal” of cancer survivorship. The focus of care for the childhood cancer survivor seen in the general pediatric practice is not the cancer from which the patient has now recovered but, rather, the actual and potential sequelae of cancer and its therapy. Childhood cancer survivors are at a substantially increased risk of morbidity and mortality when compared with the general population.5-12 Their follow-up evaluations should be individualized on the basis of their treatment history and may include screening for such potential complications as thyroid or cardiac dysfunction, second malignant neoplasms, neurocognitive difficulties, and many others.13 The COG LTFU Guidelines should be used to guide development of individualized follow-up plans for each patient on the basis of his or her particular risk of late complications, which should be developed through a shared partnership that includes the general pediatric and pediatric oncology subspecialty providers, the child, and the family. The COG LTFU Guidelines can assist the clinician in maintaining a balance between overscreening (which could potentially cause undue fear of unlikely but remotely plausible complications as well as higher medical costs resulting from unnecessary screening) and underscreening (which could miss potentially life-threatening complications, thus resulting in lost opportunities for early intervention that could minimize morbidity). Ultimately, as with all clinical practice guidelines, decisions regarding specific screening and ongoing clinical management for individual patients should be tailored to take all relevant factors (such as therapeutic exposures, medical and psychosocial history, and comorbidities) into consideration.

The pediatrician must also be aware that the childhood cancer experience is unique in that some survivors, given their young age at diagnosis, may not remember their cancer diagnosis or the treatment that they received. For others, parents may not have told the child about their cancer history. It is, therefore, not surprising that when childhood cancer survivors have been questioned regarding knowledge of their diagnosis and treatment, important deficits have been identified.22 The pediatrician may need to request a cancer treatment summary and “survivorship care plan” from the pediatric oncology center if this is not provided at the time that the child transitions back to the primary care setting. Many pediatric oncology centers offer ongoing multidisciplinary follow-up care for childhood cancer survivors on an annual, one-time, or as-needed basis. Some follow-up clinics are comprehensive, offering ongoing care and risk-based screening for childhood cancer survivors, and other follow-up clinics are consultative in nature and develop risk-based recommendations for ongoing follow-up (included in survivorship care plans) that can be carried out in the primary care setting. In any case, the components of a survivorship care plan should include recommendations for late-effects screening generated from the COG LTFU Guidelines on the basis of therapeutic exposures, identification of the provider(s) who will be coordinating the indicated screening evaluations, and identification of the provider(s) responsible for communicating and explaining the results to the patient and/or caregivers.

In addition to screening for late effects on the basis of previous therapeutic exposures, health counseling and promotion of healthy lifestyles are important aspects of long-term follow-up care in this population. Oeffinger and colleagues have shown that survivors of childhood cancer have a high rate of chronic health conditions when followed long-term.13 For this reason, it is essential for the pediatrician to provide anticipatory guidance regarding health promotion and disease prevention aimed at minimizing the risk of future morbidity and mortality. For example, survivors who are at risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease, and osteoporosis should be counseled regarding the importance of eating a well-balanced diet (high in calcium, low in fat) and participating in a regular exercise. The COG LTFU Guidelines can be used to facilitate targeted education regarding health promotion. In addition to the verbal counseling completed in the office setting, the survivor should also receive written and/or Web-based educational material that can be used to further reinforce their knowledge about their risks for specific late effects. These written and Web-based health education materials are called “Health Links” and are available with the COG LTFU Guidelines at www.survivorshipguidelines.org. They can be printed for distribution in the primary care office setting and are available for viewing by patients and their caregivers on the Internet.18

Again, it must be emphasized that the pediatrician is not alone in caring for the childhood cancer survivor. There are numerous multidisciplinary long-term follow-up programs for childhood cancer survivors, and most of these programs will work collaboratively with pediatricians to assist with the development of individualized survivorship care plans. Depending on geographic location, insurance coverage, and other considerations, some patients may return to the primary oncology center for annual or periodic visits, and their long-term follow-up care may be partially or entirely accomplished through these specialized centers, with the pediatrician providing the primary pediatric health care for those patients. However, for many survivors, long distances or other barriers may make specialized long-term follow-up impractical, and the pediatrician is often called on to provide both long-term follow-up and primary care for childhood cancer survivors in the community setting. Telephone consultation with the primary oncology team or associated long-term follow-up center is generally available to facilitate this ongoing care. For survivors who are identified as having chronic health problems as a result of their previous cancer therapy, the pediatrician can also work with the primary oncology center to obtain assistance with referrals to subspecialists knowledgeable in issues related to childhood cancer survivorship. In addition, a listing of COG-affiliated subspecialty survivorship clinics is available (www.childrensoncologygroup.org). These clinics are also excellent venues for pediatric residents to learn about the unique health care needs of childhood cancer survivors and of the long-term therapy-related risks that they continue to face across their lifespan; however, there are currently no formal mechanisms for including cancer survivorship in the training of medical students and pediatric residents.

Ensuring a smooth transition from pediatric to adult-oriented health care services poses additional challenges in the care of childhood cancer survivors as they age out of the pediatric health care system. Pretransition planning is a critical element in the successful transition from pediatric to adult-oriented health care for all adolescents and young adults with special health care needs, including childhood cancer survivors, and the medical home model provides a strong foundation for this planning.23,24 The pretransition plan should outline the roles of patient, family, subspecialty and community health care providers in the ongoing care of the survivor to ensure a successful transition. Adolescent and young adult survivors should be well versed regarding their own health maintenance needs, their potential health risks, necessary ongoing screening related to their cancer therapy, and health-related behaviors that can reduce their risk of potential adverse sequelae. They need to be aware of the importance of maintaining continuous health insurance coverage to ensure access to screening for their late effects. This can be challenging, because many adolescent and young adult survivors are still defining career goals and have, therefore, not yet attained employer-based health insurance coverage. The adolescent or young adult cancer survivor may be grappling with unique treatment-related health issues, such as infertility, at a time when their sexual maturity and personal relationships are developing. Some may also be at risk of early death because of primary disease recurrence or second malignant neoplasms,25 which in turn may require frank discussions regarding advanced directives. Adolescent and young adult survivors should, therefore, leave the pediatric health care environment equipped with a comprehensive survivorship care plan, along with the knowledge and skills required to keep abreast of new information relating to their potential health risks as that information emerges.

Although late treatment effects can be anticipated in many cases on the basis of therapeutic exposures, the risk to an individual patient is modified by multiple factors. The cancer patient may present with premorbid health conditions that influence tolerance to therapy and increase the risk of treatment-related toxicity. Cancer-related factors, including histology, tumor site, and tumor genetics, often dictate treatment modality and intensity. Host-related factors, such as age at diagnosis, race, and gender, may affect the risk of several treatment-related complications. Sociodemographic factors, such as household income, educational attainment, and socioeconomic status, often influence access to health insurance, remedial services, and appropriate risk-based health care. Organ senescence in aging survivors may accelerate presentation of age-related health conditions in survivors with subclinical organ injury or dysfunction resulting from cancer treatment. Genetic or familial characteristics may also enhance susceptibility to treatment-related complications. Problems experienced during and after treatment may further increase morbidity. Health behaviors, including tobacco and alcohol use, sun exposure, and dietary and exercise habits, may increase the risk of specific therapy-related complications. Although much is known about factors predisposing to cancer-related morbidity and mortality in this growing population, there is still much to learn to inform the development of interventions that will optimize survival rates for pediatric malignancies while limiting or eliminating therapy-related toxicities. This fact underscores the importance of long-term follow-up for childhood cancer survivors to accurately define health outcomes, characterize high-risk groups, and implement risk-reducing interventions.

SUMMARY

Given the high incidence of late effects experienced by childhood cancer survivors, it is essential that individuals who were treated for cancer during childhood receive long-term follow-up care from knowledgeable providers so their care is appropriately tailored to their specific treatment-related risk factors. This is an exciting time for providing care to childhood cancer survivors. Discussion regarding the best models for providing survivorship care are emerging concomitantly with the availability of the COG LTFU Guidelines. A recent review by Oeffinger and McCabe26 proposed a “shared-care model” that includes roles for both the primary care provider and the cancer subspecialist in the care of cancer survivors. In this model, the generalist is responsible for routine health maintenance, management of comorbid diseases, and ongoing management of the physical and emotional needs of the survivor. The oncology subspecialist provides the generalist with the survivorship care plan and is available for ongoing consultation with the generalist regarding any areas of uncertainty. Most importantly, the emphasis is on providing ongoing 2-way communication between the generalist and specialist to optimize the follow-up care for childhood cancer survivors.

Ultimately, the goal of this clinical report from the American Academy of Pediatrics is to increase the awareness of general pediatricians to the readily available resource of the COG LTFU Guidelines. These guidelines can, in turn, be used to develop a comprehensive yet individualized survivorship care plan for each childhood cancer survivor. The pediatrician works collaboratively with the pediatric oncology subspecialist, who develops the cancer treatment summary and survivorship care plan. The survivorship care plan can be used by the general pediatricians as a “road map” for providing risk-based, long-term follow-up care in the community setting. Ultimately, ongoing communication between the pediatric cancer center and the primary care pediatrician is the cornerstone for providing high-quality care to this vulnerable patient population.

Acknowledgments

RESEARCH GRANT SUPPORT This work was supported in part by the Children’s Oncology Group grant U10 CA098543 from the National Cancer Institute.

Dr. Hudson is also supported by the Cancer Center Support (CORE) grant CA 21765 from the National Cancer Institute and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

ABBREVIATIONS

- COG

Children’s Oncology Group

- COG LTFU Guidelines

Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers

AAP Section on Hematology/Oncology Executive Committee, 2007-2008

Stephen A. Feig, MD, FAAP, Chairperson

Alan S. Gamis, MD, FAAP

Jeffrey D. Hord, MD, FAAP

Eric D. Kodish, MD

Brigitta U. Mueller, MD, FAAP

Eric J. Werner, MD, FAAP

Roger L. Berkow, MD, FAAP, Past Chairperson

Children’s Oncology Group

*Smita Bhatia, MD, MPH

*Jacqueline Casillas, MD, MSHS

*Melissa M. Hudson, MD

*Wendy Landier, RN, MSN, CPNP

*Lead authors

References

- 1.Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1973-1998. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(1):43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hewitt M, Weiner SL, Simone JV, editors. National Research Council. Childhood Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Hudson MM, et al. Health care of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(1):61–70. doi: 10.1370/afm.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Yasui Y, et al. Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA. 2003;290(12):1583–1592. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurney JG, Kadan-Lottick NS, Packer RJ, et al. Endocrine and cardiovascular late effects among adult survivors of childhood brain tumors: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2003;97(3):663–673. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mertens AC, Yasui Y, Neglia JP, et al. Late mortality experience in five-year survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(13):3163–3172. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mertens AC, Yasui Y, Liu Y, et al. Pulmonary complications in survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer. A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2002;95(11):2431–2441. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Obesity in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(7):1359–1365. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM. Long-term complications following childhood and adolescent cancer: foundations for providing risk-based health care for survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(4):208–236. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.4.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sklar CA, Mertens AC, Walter A, et al. Changes in body mass index and prevalence of overweight in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: role of cranial irradiation. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2000;35(2):91–95. doi: 10.1002/1096-911x(200008)35:2<91::aid-mpo1>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace WH, Blacklay A, Eiser C, et al. Developing strategies for long term follow up of survivors of childhood cancer. BMJ. 2001;323(7307):271–274. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Children’s Oncology Group. Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers. Version 3.0. Arcadia, CA: Children’s Oncology Group; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman DA, et al. Development of risk-based guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors: the Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines from the Children’s Oncology Group Late Effects Committee and Nursing Discipline. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(24):4979–4990. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winn RJ, Botnick WZ. The NCCN guideline program: a conceptual framework. Oncology (Williston Park) 1997;11(11A):25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oeffinger KC. Longitudinal risk-based health care for adult survivors of childhood cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 2003;27(3):143–167. doi: 10.1016/s0147-0272(03)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eshelman D, Landier W, Sweeney T, et al. Facilitating care for childhood cancer survivors: integrating children’s oncology group long-term follow-up guidelines and health links in clinical practice. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2004;21(5):271–280. doi: 10.1177/1043454204268875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Cancer Institute. Passport for care: an internet-based survivorship care plan. NCI Cancer Bulletin. 2006;3(23):8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Academy of Pediatrics, Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1):184–186. [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Academy of Pediatrics. National Center of Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs. [April 8, 2008]; Available at: www.medicalhomeinfo.org.

- 22.Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, et al. Childhood cancer survivors’ knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA. 2002;287(14):1832–1839. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.14.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6 Pt 2):1304–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly AM, Kratz B, Bielski M, Rinehart PM. Implementing transitions for youth with complex chronic conditions using the medical home model. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6 Pt 2):1322–1327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mertens AC. Cause of mortality in 5-year survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(7):723–726. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5117–5124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]