Abstract

Insulin signalling in the hypothalamus plays a role in maintaining body weight. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 is an important mediator of insulin signalling in the hypothalamus. Foxo1 stimulates the transcription of the orexigenic neuropeptide Y and Agouti-related protein through the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt signalling pathway, but the role of hypothalamic Foxo1 in insulin resistance and obesity remains unclear. Here, we identify that a high-fat diet impaired insulin-induced hypothalamic Foxo1 phosphorylation and degradation, increasing the nuclear Foxo1 activity and hyperphagic response in rats. Thus, we investigated the effects of the intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) microinfusion of Foxo1-antisense oligonucleotide (Foxo1-ASO) and evaluated the food consumption and weight gain in normal and diet-induced obese (DIO) rats. Three days of Foxo1-ASO microinfusion reduced the hypothalamic Foxo1 expression by about 85%. i.c.v. infusion of Foxo1-ASO reduced the cumulative food intake (21%), body weight change (28%), epididymal fat pad weight (22%) and fasting serum insulin levels (19%) and increased the insulin sensitivity (34%) in DIO but not in control animals. Collectively, these data showed that the Foxo1-ASO treatment blocked the orexigenic effects of Foxo1 and prevented the hyperphagic response in obese rats. Thus, pharmacological manipulation of Foxo1 may be used to prevent or treat obesity.

Obesity is a major public health problem, associated with morbidity and mortality, and continues to increase worldwide (Zimmet et al. 2001). Food intake and energy expenditure are tightly regulated by complex physiological mechanisms, and a disturbance in these processes may lead to obesity (Spiegel et al. 2005). The hypothalamus is critical in the regulation of food intake-controlling neural circuits, which produce a number of peptides that influence food intake. The hypothalamus receives and integrates neural, metabolic and humoral signals from the periphery, such as insulin and leptin from pancreatic and adipose tissue, respectively (Schwartz et al. 2000). However, the underlying mechanisms by which these hormones regulate the food intake are unclear.

Insulin acts at the same hypothalamic areas as leptin to suppress feeding (Carvalheira et al. 2003). The insulin receptor (IR) is a protein with endogenous tyrosine kinase activity that, following activation by insulin, undergoes rapid autophosphorylation and, subsequently, phosphorylates intracellular protein substrates, including IRS-1 and IRS-2 (Cheatham & Kahn, 1995). After stimulation by insulin, IRS-1 and IRS-2 associate with several proteins, including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) (Folli et al. 1992; Saad et al. 1993; Williamson et al. 2003). Downstream from PI3K, the serine threonine kinase, Akt, is activated and plays a pivotal role in the regulation of various biological processes, including apoptosis, proliferation, differentiation, and intermediary metabolism (Downward, 1998; Chen et al. 2001). Among the targets of activated Akt is forkhead transcriptional factor subfamily forkhead box O1 (Foxo1 or FKHR), which is inhibited by Akt-mediated phosphorylation (Tang et al. 1999).

It has been suggested that hypothalamic Foxo1 is an important regulator of food intake and energy balance (Kim et al. 2006; Kitamura et al. 2006). Nuclear Foxo1 expression stimulates the transcription of the orexigenic neuropeptide Y and Agouti-related protein and suppresses the transcription of anorexigenic proopiomelanocortin (POMC) by antagonizing the activity of signal transducer-activated transcript-3 (STAT3) (Kim et al. 2006; Kitamura et al. 2006). In addition, the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway can exclude the Foxo1 from the nucleus and lead Foxo1 to proteosomal degradation (Matsuzaki et al. 2003; Aoki et al. 2004). These molecular events can repress Foxo1-induced orexigenic signals in the hypothalamus. In the present study, we sought to determine the contribution of the hypothalamic Foxo1 on food intake and body weight in diet-induced obesity (DIO) rats. Moreover, we examined the effects of intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) microinfusion of Foxo1 antisense oligonucleotide (Foxo1-ASO) in the hypothalamus of control and DIO rats and evaluated the food intake and body weight.

Methods

Experimental animals

Male 4-week-old Wistar rats from the University of Campinas Breeding Center were randomly divided into two groups: control, fed standard rodent chow ad libitum, and DIO, fed a fat-rich diet ad libitum (Table 1). This diet composition has been previously used (Ropelle et al. 2006; Pauli et al. 2008). For Western blot analysis, hypothalami and other tissues were obtained from six to eight rats of each group after 8 weeks of dieting. The University's Ethical Committee approved the protocols. The animals were maintained on a 12-h artificial light, 12-h dark cycle and kept in individual cages.

Table 1.

Components of rat chow and high fat diet

| Ingredients | Standard chow (g kg−1) | kcal kg−1 | High fat diet (g kg−1) | kcal kg−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cornstarch (Q.S.P.) | 397.5 | 1590 | 115.5 | 462 |

| Casein | 200 | 800 | 200 | 800 |

| Sucrose | 100 | 400 | 100 | 400 |

| Dextrinated starch | 132 | 528 | 132 | 528 |

| Lard | — | — | 312 | 2808 |

| Soybean oil | 70 | 630 | 40 | 360 |

| Cellulose | 50 | — | 50 | — |

| Mineral mix | 35 | — | 35 | — |

| Vitamin mix | 10 | — | 10 | — |

| l-Cysteine | 3 | — | 3 | — |

| Choline | 2.5 | — | 2.5 | — |

| Total | 1000 | 3948 | 1000 | 5358 |

Physiological and metabolic parameters

After 6 h of fasting, control and DIO rats were submitted to an insulin tolerance test (1 U (kg body weight)−1 of insulin). Rats were injected with insulin and blood samples were collected at 0, 4, 8, 12 and 16 min from the tail for serum glucose determination. The rate constant for plasma glucose disappearance was calculated using the formula 0.693/biological half life (t½). The plasma glucose t½ was calculated from the slope of last square analysis of the plasma glucose concentration during the linear phase of decline (Bonora et al. 1989). Plasma glucose was determined using a glucose meter (Roche Diagnostic, Rotkreuze, Switzerland), and RIA was used to measure serum insulin, according to a previous description (Scott et al. 1981). Following the experimental procedures, the rats were killed under anaesthesia (200 mg kg−1 thiopental) following the recommendations of the NIH.

Intracerebroventricular cannulation

The Wistar rats were stereotaxically instrumented under sodium amobarbital (15 mg (kg body weight)−1) anaesthesia with chronic unilateral 26-gauge stainless steel indwelling guide cannulae, aseptically placed into the lateral ventricle (0.2 mm posterior, 1.5 mm lateral, and 4.2 mm ventral to bregma), as previously described (Pereira-da-Silva et al. 2003). After a 1 week recovery period, all rats were submitted to experimental protocols.

Foxo1 antisense oligonucleotide (Foxo1-ASO)

Sense and antisense Foxo1 oligonucleotides were diluted in TE buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm EDTA) and injected (Hamilton syringe) twice a day at 08.00 h and 16.00 h, with a total volume of 2.0 μl per dose (final concentrations of 0.1, 0.2 and 0.4 nmol), 24, 48 and 72 h after the onset of the experimental period. Rats were randomly assigned to treatment conditions: rats without oligonucleotide treatment (control); rats with sense (5′GAT GCT GGA CAT GGG AGA T 3′) oligonucleotide treatment (Sense) and rats with antisense (5′ATC TCC CAT GTC CAG CAT C 3′) oligonucleotide treatment (ASO).

Treatments and measurement of food intake

Rats deprived of food for 6 h with free access to water were i.c.v. injected (2 μl) with saline or insulin (10−6m). Thereafter standard chow was given and food intake was determined by measuring the difference between the weight of chow given and the weight of chow at the end of a 12 h period. Similar studies were carried out in rats that were initially injected i.c.v. with sense or Foxo1-ASO (4 nmol).

Protein analysis by immunoblotting

As soon as anaesthesia was assured by the loss of pedal and corneal reflexes, 2.0 μl of normal saline or insulin (10−6m) was injected i.c.v. using a Hamilton syringe. Ten minutes after insulin injection, the cranium was opened and the basal diencephalon, including the preoptic area and hypothalamus, was excised. The hypothalami were pooled and 200 μg of protein was used as whole tissue extract. For evaluated insulin-induced Foxo1 expression, hypothalamus was excised 30 min after insulin injection, as shown for Kim and colleagues (Kim et al. 2006). Tissues were pooled, minced coarsely and homogenized immediately in extraction buffer (1% Triton X-100, 100 mm Tris, pH 7.4, containing 100 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 100 mm sodium fluoride, 10 mm EDTA, 10 mm sodium vanadate, 2 mm phenylmethanesulphonylfluoride (PMSF) and 0.1 mg ml−1 aprotinin) at 4°C with a Polytron PTA 20S generator (Brinkmann Instruments model PT 10/35) operated at maximum speed for 15 s. The extracts were centrifuged at 9 000 g and 4°C in a Beckman 70.1 Ti rotor (Palo Alto, CA, USA) for 45 min to remove insoluble material, and the supernatants of these tissues were used for protein quantification, using the Bradford method (Bradford, 1976). Proteins were denatured by boiling in Laemmli sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970) containing 100 mm DTT, run on SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Antibodies used for immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were anti-phosphotyrosine, anti-IR, anti-IRS-2 anti-Akt, anti-phospho-Akt, anti-α-tubulin and anti-histone (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., CA, USA), anti-phospho-Foxo1 and anti-Foxo1 (Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA). Blots were exposed to preflashed Kodak XAR film with Cronex Lightning Plus intensifying screens at −80°C for 12–48 h. Band intensities were analysed by optical densitometry (Scion Image software, ScionCorp, Frederick, MD, USA) of the developed autoradiographs.

Nuclear extraction

To characterize the expression and subcellular localization of Foxo1, a subcellular fractionation protocol was employed as described previously (Prada et al. 2006). The hypothalami from untreated rats or rats treated with Foxo1-ASO (0.4 nmol), according to the protocols described above, were minced and homogenized in 2 vol. of STE buffer (0.32 m sucrose, 20 mm Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 2 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 100 mm sodium fluoride, 100 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 10 mm sodium orthovanadate, 1 mm PMSF, and 0.1 mg ml−1 aprotinin) at 4°C with a Polytron homogenizer. The homogenates were centrifuged (1000 g, 25 min, 4°C) to obtain pellets. The pellets were washed once with STE buffer (1000 g, 10 min, 4°C) and suspended in Triton buffer (1% Triton X-100, 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 200 mm EDTA, 10 mm sodium orthovanadate, 1 mm PMSF, 100 mm NaF, 100 mm sodium pyrophosphate, and 0.1 mg ml−1 aprotinin), kept on ice for 30 min, and centrifuged (15 000 g, 30 min, 4°C) to obtain the nuclear fraction. The samples were used for immunoprecipitation with Foxo1 antibody and Protein A-Sepharose 6MB (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech UK Ltd). Thereafter they were treated with Laemmli buffer with 100 mm DTT and heated in a boiling water bath for 5 min, and aliquots (100 μg of protein) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-CBP/p300 or Foxo1 antibodies, as described elsewhere (Gasparetti et al. 2003).

Statistical analysis

All numerical results are expressed as the means ±s.e.m. of the indicated number of experiments. The results of blots are presented as direct comparisons of bands in autoradiographs and quantified by densitometry using the Scion Image software. Data were analysed by ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis of significance (Bonferroni test) when appropriate, comparing experimental and control groups. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

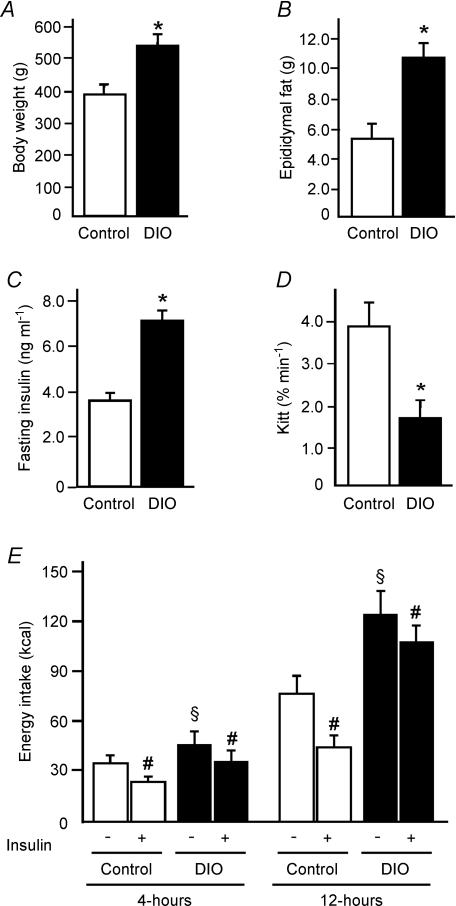

Metabolic parameters and energy intake of control and DIO rats

Figure 1 shows comparative data regarding control and DIO rats. Rats fed on the high-fat diet for 8 weeks had a greater body weight, epididymal fat pad weight and fasting serum insulin than age-matched controls. The glucose disappearance rate (Kitt) was decreased in DIO animals when compared to control groups (Fig. 1A–D). The fasting glucose concentration was similar between the groups (data not shown).

Figure 1. Metabolic parameters and energy intake of control and diet-induced obese (DOI) rats.

A, total body weight. B, epididymal fat pad weight. C, fasting serum insulin. D, insulin tolerance test. E, energy intake 4 and 12 h after saline or insulin infusion in the hypothalamus of control and DOI rats. Bars represent means ±s.e.m. of eight rats. *P < 0.004 versus control, #P < 0.04 versus respective saline groups, §P < 0.01 obese rats plus saline versus control plus saline.

Next, we evaluated the effect of insulin (2 μl, 10−6m) or its saline vehicle on the control of food intake. In the control and DIO rats treated with saline, we observed that the energy intake was higher in DIO rats, 27% and 63% during 4 and 12 h, respectively, when compared to control animals. Insulin induced reductions in the 4 and 12 h of food intake of both control and DIO rats. In the control group, insulin reduced food intake by about 31% and 41% during 4 and 12 h, respectively, while in the obese rats the same dose induced reductions of about 21% and 14% respectively, indicating that insulin was much less effective in DIO rats (Fig. 1E).

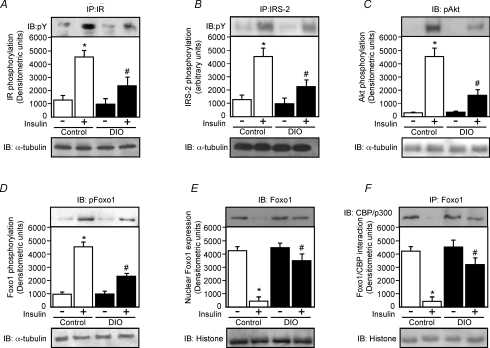

Intracerebroventricular insulin activates the hypothalamic IR/IRS-2/Akt/Foxo1 pathway in control rats to a greater extent than in DIO rats

Insulin (2 μl, 10−6m) i.c.v. induced increases in IR, IRS-2, Akt and Foxo1 phosphorylation in hypothalamus from both control and DIO rats. However, insulin was much less effective in inducing IR, IRS-2, Akt and Foxo1 phosphorylation in DIO rats when compared to control rats (Fig. 2A–D, upper panels). We did not observe differences in IR, IRS-2, Akt and Foxo1 phosphorylation between control and DIO groups treated with saline.

Figure 2. Effects of i.c.v. infusion of insulin on insulin signalling in the hypothalamus of control and DIO rats.

A–D, upper panels, representative blots show the insulin-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor (IR; A), insulin receptor substrate-2 (IRS-2; B), Akt serine phosphorylation (C) and Foxo1 phosphorylation of control and DIO rats (D). A–D, lower panels, total protein expression of α-tubulin. The evaluation of nuclear Foxo1 expression (E) and the association between Foxo1 and CBP/p300 (F), were performed using nuclear extract of control and DIO rats as described in Methods. The results of scanning densitometry were expressed as arbitrary units. Bars represent means ±s.e.m. of six rats. *P < 0.001 versus control plus saline, #P < 0.01 versus DIO plus saline.

In addition, we evaluated the Foxo1 nuclear expression and the association between Foxo1 and CBP/p300 in control and DIO rats after insulin and saline injection. In the hypothalamus of control rats, insulin reduced Foxo1 expression in the nuclear fraction by 89%, compared with a 22% reduction in the hypothalamus from DIO rats (Fig. 2E, upper panel). Insulin also reduced Foxo1/CBP interaction by 89% in control rats and 29% in the hypothalamus of DIO rats (Fig. 2F, upper panel). We did not observe differences in Foxo1 nuclear expression and Foxo1/CBP binding between control and DIO groups treated with saline.

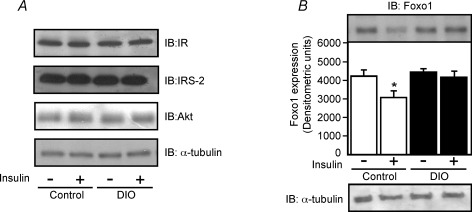

Insulin reduced Foxo1 expression in the hypothalamus of control but not in DIO rats

Previous studies suggested that insulin controlled the Foxo1 expression in the hypothalamus of lean mice (Kim et al. 2006). We sought to determine the effects of i.c.v. infusion of insulin on the expression of Foxo1 in the hypothalamus of control and DIO rats. First, we observed that insulin did not change the IR, IRS-2 and Akt protein expression in the hypothalamus of control and DIO rats (Fig. 3A). However, 30 min of insulin i.c.v. infusion reduced Foxo1 expression in the hypothalamus of control rats by about 27%. Interestingly, in the hypothalamus of DIO rats, insulin did not change the Foxo1 expression (Fig. 3B). We did not observe differences in Foxo1 expression between control and DIO groups treated with saline.

Figure 3. Effects of i.c.v. insulin infusion on Foxo1 expression in the hypothalamus of control and DIO rats.

A, representative blots show the protein expression of insulin receptor (IR), insulin receptor substrate-2 (IRS-2) and Akt in the hypothalamus of control and DIO rats injected with saline (2.0 μl) or insulin (2.0 μl, 10−6m). B, representative blots show the protein expression of Foxo1 in the hypothalamus of control and DIO rats injected with saline (2.0 μl) or insulin (2.0 μl, 10−6m). The results of scanning densitometry were expressed as arbitrary units. Bars represent means ±s.e.m. of six rats. *P < 0.03 versus control plus saline.

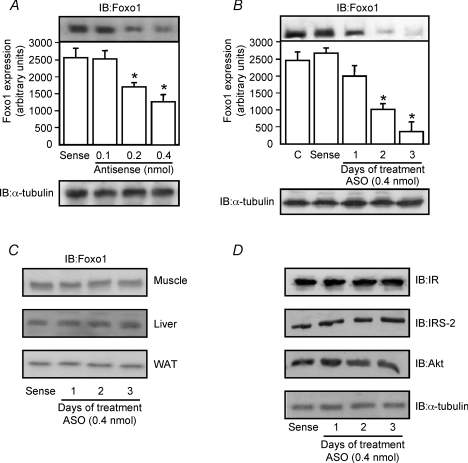

Determining the dose–response and time course effects of i.c.v.-injected Foxo1 antisense upon hypothalamic Foxo1 expression

To evaluate the effect of Foxo1-ASO on Foxo1 expression in the hypothalamus, i.c.v.-cannulated control rats were treated for 1 day with antisense Foxo1 at low doses (0.1 and 0.2 nmol Foxo1-ASO) or at a high dose (0.4 nmol Foxo1-ASO). As shown in Fig. 4, a single infusion of Foxo1-ASO (0.4 nmol) induced a reduction of Foxo1 expression by about 50% in the hypothalamus of control animals. In addition, injection of a high dose (0.4 nmol) of Foxo1-ASO for 1, 2 and 3 days was able to reduce Foxo1 expression in a time-dependent manner. Three days after Foxo1-ASO treatment we observed a great reduction (85%) in the expression of Foxo1 in the hypothalamus of control rats (Fig. 4B). This treatment with Foxo1-ASO did not change the IR, IRS-2 and Akt protein expression in the hypothalamus of control rats (Fig. 4D, upper panels) and did not change the Foxo-1 protein expression in the peripheral tissues such as gastrocnemius muscle, liver and white adipose tissue (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Effects of i.c.v. Foxo1-ASO injection in hypothalamic Foxo1 expression in lean rats.

Representative Western blots demonstrating the dose-dependent effect of 24 h of treatment with saline, sense or Foxo1-ASO in lean rats (A) and hypothalamic Foxo1 expression in a time-dependent manner after central infusions of Foxo1-ASO in lean rats (B). C, representative Western blots show the protein expression of Foxo1 in the gastrocnemius muscle, hepatic tissue and white adipose tissue after i.c.v. infusion of Foxo1-ASO in lean rats during 3 days (0.4 nmol). D, representative Western blots show the protein expression of IR, IRS-2, Akt and α-tubulin in the hypothalamus of lean rats after i.c.v. infusion of Foxo1-ASO in lean rats during 3 days (0.4 nmol). The results of scanning densitometry were expressed as arbitrary units. Bars represent means ±s.e.m. of eight rats. *P < 0.01 versus sense treatment.

Effects of Foxo1-ASO treatment on food intake and body weight in control and DIO rats

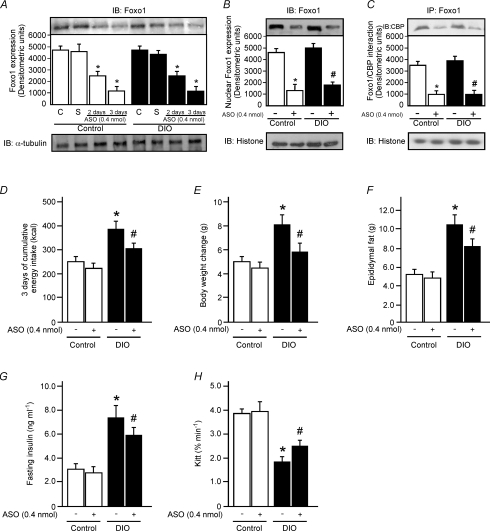

To determine the impact of Foxo1-ASO treatment on food intake and body weight, we injected Foxo1-ASO (0.4 nmol) in the hypothalamus of control and DIO rats during 3 days. Foxo1-ASO reduced Foxo1 expression in control and DIO rats in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). The nuclear Foxo1 expression was reduced by about 71 and 64% in control and DIO rats, respectively, when compared to the respective control group treated with sense after 3 days (Fig. 5B). We also observed that Foxo1-ASO reduced Foxo1/CBP interaction by about 70% and 73% in control and DIO rats, respectively, when compared to the respective control group treated with sense after 3 days (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. The effect of central infusion of Foxo1-ASO on total Foxo1 expression, food intake and body weight in control and DIO rats.

Hypothalamic Foxo1 expression was evaluated after 72 h of central infusions of Foxo1-ASO in lean and DIO rats. Rats received i.c.v. saline (C), sense (S) or Foxo1-ASO (0.4 nmol) during 2 or 3 days (A). The evaluation of nuclear Foxo1 expression (B) and the association between Foxo1 and CBP/p300 (C) were performed using nuclear extract of control and DIO rats as described in Methods. Determination of 3 days of cumulative energy intake (D), body weight change (E), epididymal fat pad weight (F), fasting serum insulin (G) and insulin tolerance test (H) of control and DIO rats 3 days after Foxo1-ASO or sense i.c.v. infusion. Bars represent means ±s.e.m. of 6–8 rats; *P < 0.001, ASO versus control plus sense; #P < 0.03, versus DIO plus sense.

Three days after Foxo1-ASO treatment the cumulative food intake, body weight, epididymal fat pad weight, fasting insulin levels and insulin sensitivity were similar in control animals when compared to sense-injected control rats (Fig. 5D–H). However, 3 days after Foxo1-ASO treatment in DIO rats, there was a reduction in cumulative food intake (21%), body weight change (28%), epididymal fat pad weight (22%) and fasting serum insulin levels (19%) and an increase in insulin sensitivity (34%) when compared to sense-injected DIO rats (Fig. 5D–H). The fasting glucose concentration was similar between the groups (data not shown).

Discussion

During the last decade, advances have been made in the characterization of the role played by the hypothalamus in the coordination of food intake and energy expenditure (Friedman, 2000; Flier, 2004). Multiple hypothalamic neuronal signalling pathways and the cross talk between these pathways are involved in the control of energy intake (Schwartz et al. 2000; Minokoshi et al. 2004; Cota et al. 2006; Ropelle et al. 2007, 2008b). In addition to leptin, insulin is also able to reduce food intake (Schwartz et al. 2000; Carvalheira et al. 2001; Niswender et al. 2003). It has been demonstrated that the increased responsiveness of leptin and insulin action in the hypothalamus could be pathophysiologically important in the prevention of obesity (Picardi et al. 2008; Ropelle et al. 2008a) and Foxo1 is a distal protein of the insulin signalling that contributed to anorexigenic effects of insulin (Romanatto et al. 2007; Belgardt et al. 2008). In the present study, we demonstrate that intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) microinfusion of insulin reduced Foxo1 expression in the hypothalamus of control but not in rats with diet-induced obesity (DIO). We showed that the injection of Foxo1 antisense oligonucleotide (Foxo1-ASO) in the hypothalamus leads to reduced Foxo1 expression in both control and DIO rats, and reduced food consumption and body weight gain in DIO but not in control rats.

As in peripheral tissues, neuronal insulin action involves the IR/IRS/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signal transduction pathway (Schwartz et al. 2000). The hypothalamic insulin signalling increases after either i.c.v. or systemic insulin administration (Niswender et al. 2003) and the inhibitory effect of i.c.v. insulin on both food intake (Carvalheira et al. 2001; Niswender et al. 2003) and the impairment in this pathway contribute to the hyperphagic response (Carvalheira et al. 2003; De Souza et al. 2005). On the other hand, the improvement in the hypothalamic IR/IRS-2/Akt pathway increases insulin-induced anorexigenic signals (Flores et al. 2006). Foxo1 is a downstream target of Akt. Activation of Akt phosphorylates Foxo1, leading to its nuclear exclusion and proteosomal degradation (Matsuzaki et al. 2003; Aoki et al. 2004), and thereby inhibiting its anorexigenic actions. Here, we showed that i.c.v. insulin infusion increased the IR/IRS-2/Akt/Foxo1 phosphorylation in control rats to a greater extent than in DIO animals. This aberrant molecular signalling also reduced insulin-induced Foxo1 degradation in the hypothalamus of DIO rats compared with control rats. These data suggest that hypothalamic Foxo1 phosphorylation and degradation are required for the induction of anorexia by insulin, establishing a signalling pathway through which insulin acts in hypothalamus neurons to control food intake.

Foxo1 is expressed in cells in the hypothalamus, in POMC and Agouti-related protein (AgRP) neurons (Kitamura et al. 2006). In these neurons, Foxo1 stimulates the transcription of the orexigenic neuropeptide Y (NPY) and AgRP through the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway, and suppresses the transcription of anorexigenic POMC by antagonizing the activity of STAT3 in lean mice (Kim et al. 2006; Kitamura et al. 2006). Different groups have demonstrated that the hypothalamic Foxo1 expression controls food intake in rodents (Kim et al. 2006; Kitamura et al. 2006). It has been proposed that insulin and leptin decrease hypothalamic Foxo1 expression. In agreement with this, activation of insulin signalling by expression of PI3K and Akt or treatment with insulin and leptin inhibits Foxo1-stimulated NPY transcription (Kim et al. 2006).

In the present study, we sought to determine the effects of Foxo1-ASO in the hypothalamus of DIO rats. The i.c.v. treatment with Foxo1-ASO promoted reduction of Foxo1 protein expression in a time- and dose-dependent manner. Foxo1-ASO also reduced nuclear interaction between Foxo1 and CBP/p300 in the hypothalamus of control and DIO rats. Three days of treatment with Foxo-ASO (4 nmol) reduced the cumulative energy intake, body weight gain and epididymal fat pad weight, fasting insulin levels and increased insulin sensitivity in DIO but not in control animals. Although Kim and colleagues showed that bilateral injection of the Foxo1 siRNA into the arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus decreased daily food intake and body weight in lean mice (Kim et al. 2006), our results showed that a daily infusion of Foxo1-ASO during 3 days reduced the cumulative food intake in DIO but not in control animals. Our data are in accordance with Kitamura and coworkers who explored the contribution of loss-of-function of Foxo1 on orexigenic signalling and food intake using two different approaches in lean mice. The injection of a dominant-negative of Foxo1 prevented induction of AgRP expression caused by fasting but the AgRP expression was similar in mice under normal conditions. Furthermore, in Foxo1 haploinsufficient mice (Foxo1+/−), the food intake was similar under basal conditions when compared to wild-type littermate controls and the difference in food intake occurred only after i.c.v. leptin infusion in Foxo1+/− mice when compared to control mice (Kitamura et al. 2006). These apparent contradictory results in lean animals may be related to the different approaches and model of rodent and deserves further investigation.

The in vivo physiological importance of Foxo transcription factors in the brain has been reported. Several studies showed that Foxo1 is expressed in different areas of murine brain, including hippocampus, neocortex, hypothalamus and other areas (Fukunaga et al. 2005; Hoekman et al. 2006; Kitamura et al. 2006). In the hypothalamus of rodents, Foxo1 is expressed in a majority of cells in the arcuate nucleus, ventromedial hypothalamus and dorsomedial hypothalamus (Kitamura et al. 2006). Although the Foxo1-ASO injection into the third ventricle of rats reduced Foxo1 expression in a tissue-specific manner as demonstrated in Fig. 4, we cannot exclude the possibility that Foxo1-ASO reduced the Foxo1 expression in other areas of the brain.

Collectively, these data showed that central insulin resistance diminished insulin-induced Foxo1 phosphorylation and insulin-induced Foxo1 degradation. Thus, we identify that a high-fat diet impaired the hypothalamic Foxo1 phosphorylation and increased the nuclear activity, increasing the hyperphagic response in rats. Foxo1-ASO treatment blocked the orexigenic effects of hypothalamic Foxo1 and prevented the hyperphagic response in these animals. Thus, pharmacological manipulation of Foxo1 may be used to prevent or treat obesity.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by grants from Fundacão de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) and Conselho Nacional de desenvolvimento científico e tecnológico (CNPq).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AgRP

Agouti-related peptide

- Akt

protein kinase B

- ASO

antisense oligonucleotide

- CBP

citrate binding protein

- DIO

diet-induced obesity

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid

- Foxo1

forkhead box protein

- i.c.v.

intracerebroventricular

- IR

insulin receptor

- IRS-1

insulin receptor substrate 1

- IRS-2

insulin receptor substrate 2

- Kitt

glucose disappearance rate

- NPY

neuropeptide Y

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

- POMC

proopiomelanocortin

- RIA

radioimmunossay

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- STAT3

signal transducer-activated transcript-3

- PMSF

phenylmethanesulphonylfluoride

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

Author contributions

E.R.R.: conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published; J.R.P.: conception and design; P.P.: conception and design; D.E.C.: conception and design; G.Z.R.: conception and design; J.C.M.: conception and design; M.J.S.F.: conception and design; G.d.L.: conception and design; R.A.P.: final approval of the version to be published; J.B.C.C.: drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; L.A.V.: drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; M.J.S.: drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; C.T.D.S: conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published.

References

- Aoki M, Jiang H, Vogt PK. Proteasomal degradation of the FoxO1 transcriptional regulator in cells transformed by the P3k and Akt oncoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13613–13617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405454101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgardt BF, Husch A, Rother E, Ernst MB, Wunderlich FT, Hampel B, Klockener T, Alessi D, Kloppenburg P, Bruning JC. PDK1 deficiency in POMC-expressing cells reveals FOXO1-dependent and -independent pathways in control of energy homeostasis and stress response. Cell Metab. 2008;7:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonora E, Moghetti P, Zancanaro C, Cigolini M, Querena M, Cacciatori V, Corgnati A, Muggeo M. Estimates of in vivo insulin action in man: comparison of insulin tolerance tests with euglycemic and hyperglycemic glucose clamp studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;68:374–378. doi: 10.1210/jcem-68-2-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalheira JB, Ribeiro EB, Araujo EP, Guimaraes RB, Telles MM, Torsoni M, Gontijo JA, Velloso LA, Saad MJ. Selective impairment of insulin signalling in the hypothalamus of obese Zucker rats. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1629–1640. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1246-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalheira JB, Siloto RM, Ignacchitti I, Brenelli SL, Carvalho CR, Leite A, Velloso LA, Gontijo JA, Saad MJ. Insulin modulates leptin-induced STAT3 activation in rat hypothalamus. FEBS Lett. 2001;500:119–124. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02591-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheatham B, Kahn CR. Insulin action and the insulin signaling network. Endocr Rev. 1995;16:117–142. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-2-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Kim O, Yang J, Sato K, Eisenmann KM, McCarthy J, Chen H, Qiu Y. Regulation of Akt/PKB activation by tyrosine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31858–31862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100271200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D, Proulx K, Smith KA, Kozma SC, Thomas G, Woods SC, Seeley RJ. Hypothalamic mTOR signaling regulates food intake. Science. 2006;312:927–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1124147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza CT, Araujo EP, Bordin S, Ashimine R, Zollner RL, Boschero AC, Saad MJ, Velloso LA. Consumption of a fat-rich diet activates a proinflammatory response and induces insulin resistance in the hypothalamus. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4192–4199. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downward J. Mechanisms and consequences of activation of protein kinase B/Akt. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:262–267. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flier JS. Obesity wars: molecular progress confronts an expanding epidemic. Cell. 2004;116:337–350. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores MB, Fernandes MF, Ropelle ER, Faria MC, Ueno M, Velloso LA, Saad MJ, Carvalheira JB. Exercise improves insulin and leptin sensitivity in hypothalamus of Wistar rats. Diabetes. 2006;55:2554–2561. doi: 10.2337/db05-1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folli F, Saad MJ, Backer JM, Kahn CR. Insulin stimulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity and association with insulin receptor substrate 1 in liver and muscle of the intact rat. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22171–22177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JM. Obesity in the new millennium. Nature. 2000;404:632–634. doi: 10.1038/35007504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga K, Ishigami T, Kawano T. Transcriptional regulation of neuronal genes and its effect on neural functions: expression and function of forkhead transcription factors in neurons. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;98:205–211. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fmj05001x3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparetti AL, de Souza CT, Pereira-da-Silva M, Oliveira RL, Saad MJ, Carneiro EM, Velloso LA. Cold exposure induces tissue-specific modulation of the insulin-signalling pathway in Rattus norvegicus. J Physiol. 2003;552:149–162. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.050369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekman MF, Jacobs FM, Smidt MP, Burbach JP. Spatial and temporal expression of FoxO transcription factors in the developing and adult murine brain. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006;6:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MS, Pak YK, Jang PG, Namkoong C, Choi YS, Won JC, Kim KS, Kim SW, Kim HS, Park JY, Kim YB, Lee KU. Role of hypothalamic Foxo1 in the regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:901–906. doi: 10.1038/nn1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura T, Feng Y, Kitamura YI, Chua SC, Jr, Xu AW, Barsh GS, Rossetti L, Accili D. Forkhead protein FoxO1 mediates Agrp-dependent effects of leptin on food intake. Nat Med. 2006;12:534–540. doi: 10.1038/nm1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki H, Daitoku H, Hatta M, Tanaka K, Fukamizu A. Insulin-induced phosphorylation of FKHR (Foxo1) targets to proteasomal degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11285–11290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934283100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minokoshi Y, Alquier T, Furukawa N, Kim YB, Lee A, Xue B, Mu J, Foufelle F, Ferre P, Birnbaum MJ, Stuck BJ, Kahn BB. AMP-kinase regulates food intake by responding to hormonal and nutrient signals in the hypothalamus. Nature. 2004;428:569–574. doi: 10.1038/nature02440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswender KD, Morrison CD, Clegg DJ, Olson R, Baskin DG, Myers MG, Jr, Seeley RJ, Schwartz MW. Insulin activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus: a key mediator of insulin-induced anorexia. Diabetes. 2003;52:227–231. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli JR, Ropelle ER, Cintra DE, Carvalho-Filho MA, Moraes JC, De Souza CT, Velloso LA, Carvalheira JB, Saad MJ. Acute physical exercise reverses S-nitrosation of the insulin receptor, insulin receptor substrate 1 and protein kinase B/Akt in diet-induced obese Wistar rats. J Physiol. 2008;586:659–671. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-da-Silva M, Torsoni MA, Nourani HV, Augusto VD, Souza CT, Gasparetti AL, Carvalheira JB, Ventrucci G, Marcondes MC, Cruz-Neto AP, Saad MJ, Boschero AC, Carneiro EM, Velloso LA. Hypothalamic melanin-concentrating hormone is induced by cold exposure and participates in the control of energy expenditure in rats. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4831–4840. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picardi PK, Calegari VC, Prada PO, Moraes JC, Araujo E, Marcondes MC, Ueno M, Carvalheira JB, Velloso LA, Saad MJ. Reduction of hypothalamic protein tyrosine phosphatase improves insulin and leptin resistance in diet-induced obese rats. Endocrinology. 2008;149:3870–3880. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prada PO, Pauli JR, Ropelle ER, Zecchin HG, Carvalheira JB, Velloso LA, Saad MJ. Selective modulation of the CAP/Cbl pathway in the adipose tissue of high fat diet treated rats. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4889–4894. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanatto T, Cesquini M, Amaral ME, Roman EA, Moraes JC, Torsoni MA, Cruz-Neto AP, Velloso LA. TNF-α acts in the hypothalamus inhibiting food intake and increasing the respiratory quotient – effects on leptin and insulin signaling pathways. Peptides. 2007;28:1050–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropelle ER, Fernandes MF, Flores MB, Ueno M, Rocco S, Marin R, Cintra DE, Velloso LA, Franchini KG, Saad MJ, Carvalheira JB. Central exercise action increases the AMPK and mTOR response to leptin. PLoS ONE. 2008a;3:e3856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Ropelle ER, Pauli JR, Fernandes MF, Rocco SA, Marin RM, Morari J, Souza KK, Dias MM, Gomes-Marcondes MC, Gontijo JA, Franchini KG, Velloso LA, Saad MJ, Carvalheira JB. A central role for neuronal AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in high-protein diet-induced weight loss. Diabetes. 2008b;57:594–605. doi: 10.2337/db07-0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropelle ER, Pauli JR, Prada PO, de Souza CT, Picardi PK, Faria MC, Cintra DE, Fernandes MF, Flores MB, Velloso LA, Saad MJ, Carvalheira JB. Reversal of diet-induced insulin resistance with a single bout of exercise in the rat: the role of PTP1B and IRS-1 serine phosphorylation. J Physiol. 2006;577:997–1007. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.120006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropelle ER, Pauli JR, Zecchin KG, Ueno M, de Souza CT, Morari J, Faria MC, Velloso LA, Saad MJ, Carvalheira JB. A central role for neuronal adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase in cancer-induced anorexia. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5220–5229. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad MJ, Folli F, Kahn JA, Kahn CR. Modulation of insulin receptor, insulin receptor substrate-1, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in liver and muscle of dexamethasone-treated rats. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2065–2072. doi: 10.1172/JCI116803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte D, Jr, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG. Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature. 2000;404:661–671. doi: 10.1038/35007534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott AM, Atwater I, Rojas E. A method for the simultaneous measurement of insulin release and B cell membrane potential in single mouse islets of Langerhans. Diabetologia. 1981;21:470–475. doi: 10.1007/BF00257788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel A, Nabel E, Volkow N, Landis S, Li TK. Obesity on the brain. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:552–553. doi: 10.1038/nn0505-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang ED, Nunez G, Barr FG, Guan KL. Negative regulation of the forkhead transcription factor FKHR by Akt. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16741–16746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson D, Gallagher P, Harber M, Hollon C, Trappe S. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway activation: effects of age and acute exercise on human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2003;547:977–987. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.036673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature. 2001;414:782–787. doi: 10.1038/414782a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]