Abstract

Nodulation factor (NF) signal transduction in the legume-rhizobium symbiosis involves calcium oscillations that are instrumental in eliciting nodulation. To date, Ca2+ spiking has been studied exclusively in the intracellular bacterial invasion of growing root hairs in zone I. This mechanism is not the only one by which rhizobia gain entry into their hosts; the tropical legume Sesbania rostrata can be invaded intercellularly by rhizobia at cracks caused by lateral root emergence, and this process is associated with cell death for formation of infection pockets. We show that epidermal cells at lateral root bases respond to NFs with Ca2+ oscillations that are faster and more symmetrical than those observed during root hair invasion. Enhanced jasmonic acid or reduced ethylene levels slowed down the Ca2+ spiking frequency and stimulated intracellular root hair invasion by rhizobia, but prevented nodule formation. Hence, intracellular invasion in root hairs is linked with a very specific Ca2+ signature. In parallel experiments, we found that knockdown of the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase gene of S. rostrata abolished nodule development but not the formation of infection pockets by intercellular invasion at lateral root bases, suggesting that the colonization of the outer cortex is independent of Ca2+ spiking decoding.

INTRODUCTION

Leguminous plants have coevolved with nitrogen-fixing rhizobia to establish a sophisticated root endosymbiosis. In a developmental process guided by reciprocal signal exchange, the plants form new organs, nodules, to house bacteria that reduce molecular dinitrogen and feed their host with ammonia. In most studied interactions, nodulation occurs in a susceptible root zone with developing root hairs (zone I). This process is activated by bacterial signals, the lipochitooligosaccharidic nodulation (Nod) factors (NFs) (D'Haeze and Holsters, 2002; Jones et al., 2007). In response to NFs, root hairs form a curl that provides a pocket for a microbial colony. Concomitantly, cortical cell division is triggered for organ formation. Purified NFs elicit several physiological responses in susceptible root hair cells, such as calcium influx, membrane depolarization, and rhythmic Ca2+ oscillations (spiking) in and around the nucleus (Oldroyd and Downie, 2004).

The molecular basis of legume symbiosis has been particularly well studied in Medicago truncatula and Lotus japonicus, in which essential nodulation genes have been identified through forward genetics and map-based cloning. Characterization of plant mutants that are affected in NF signal perception or transduction revealed that NFs are perceived by LysM domain–containing receptor-like kinases, such as lysine motif receptor-like kinase3 (LYK3)-LYK4/Nod factor perception (NFP) of M. truncatula and Nod factor receptor1 (NFR1)/NFR5 of L. japonicus (Ben Amor et al., 2003; Limpens et al., 2003; Madsen et al., 2003; Radutoiu et al., 2003, 2007; Arrighi et al., 2006). Other plant nodulation functions are common with the more ancient symbiosis with arbuscular mycorrhiza and include putative cation transporters (does not make infection1 [DMI1] of M. truncatula and CASTOR/POLLUX of L. japonicus) (Ané et al., 2004; Imaizumi-Anraku et al., 2005), a leucine-rich repeat-type receptor-like kinase (DMI2) of M. truncatula, symbiosis receptor-like kinase (SYMRK) of L. japonicus, and nodulation receptor kinase of M. sativa (Endre et al., 2002; Stracke et al., 2002), two nucleoporins (NUP133 and NUP85) of L. japonicus (Kanamori et al., 2006; Saito et al., 2007), and a calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase (CCaMK) of M. truncatula (Lévy et al., 2004; Mitra et al., 2004). Transcription factors of the GRAS (gibberellin-insensitive, repressor of gal-3, and SCARECROW) family nodulation signaling pathway (NSP1 and NSP2) of M. truncatula and the ethylene response factor required for nodulation (ERN) family of M. truncatula are involved in NF-specific gene expression. Together with the transcriptional regulator nodulation inception (NIN) identified in L. japonicus and M. truncatula, they regulate downstream responses, such as cytokinin signaling for primordium initiation (Schauser et al., 1999; Kaló et al., 2005; Smit et al., 2005; Gonzalez-Rizzo et al., 2006; Heckmann et al., 2006; Marsh et al., 2007; Middleton et al., 2007; Murray et al., 2007; Tirichine et al., 2007; Frugier et al., 2008).

Ca2+ oscillations have been shown to direct gene expression in animal systems (Gu and Spitzer, 1995; Dolmetsch et al., 1997; De Koninck and Schulman, 1998). In plants, Ca2+ oscillations are involved in abscisic acid signaling in guard cells, in pollen tube elongation, and in the NF signal transduction pathway of legumes (Holdaway-Clarke et al., 1997; Li et al., 1998; Allen et al., 2001; Oldroyd et al., 2001b; Oldroyd and Downie, 2006). NF-induced Ca2+ spiking is correlated with nodulin gene expression, is influenced by the hormones ethylene and jasmonate (JA) and by the developmental context in the root, and is blocked by inhibitors of Ca2+ pumps and channels (Pingret et al., 1998; Oldroyd et al., 2001a; Engstrom et al., 2002; Miwa et al., 2006a, 2006b; Sun et al., 2006).

The nonnodulating mutants dmi3 of M. truncatula and sym9 of pea (Pisum sativum) show normal Ca2+ spiking and are affected in a CCaMK-encoding gene (Lévy et al., 2004; Mitra et al., 2004), which is presumably required for the interpretation of the Ca2+ signature (Oldroyd and Downie, 2004). CCaMK has a kinase domain, a calmodulin (CaM) binding domain with strong homology to CaM-dependent kinase II in animals, and a C-terminal Ca2+ binding domain with three EF hands homologous to the neuronal Ca2+ binding protein visinin (Patil et al., 1995). Autophosphorylation of CCaMK after EF hand binding of Ca2+ ions enhances the Ca2+/CaM association that subsequently suppresses autoinhibition, thus activating the kinase domain and allowing substrate phosphorylation (Patil et al., 1995; Gleason et al., 2006; Tirichine et al., 2006). CCaMK is expressed in roots and in developing nodules (Lévy et al., 2004), and transcripts have been detected in a few cell layers directly adjacent to the meristem of indeterminate nodules. CCaMK localizes to the nucleus of root cells, corresponding to the site where the Ca2+ spiking intensity is the highest and the possible target proteins NSP1 and NSP2 accumulate (Ehrhardt et al., 1996; Kaló et al., 2005; Limpens et al., 2005; Smit et al., 2005). Functional analysis has indicated that the CCaMK proteins are important for nodule organogenesis and root hair invasion and that gain of function results in the formation of spontaneous nodules (Gleason et al., 2006; Tirichine et al., 2006). Nonlegume CCaMK homologs can interpret the NF-induced Ca2+ signature and restore nodule formation in the M. truncatula dmi3 mutant, although not necessarily allowing normal bacterial invasion (Gleason et al., 2006; Godfroy et al., 2006). These data suggest that root hair invasion has more stringent requirements for correct interpretation of specific spiking patterns than initiation of organ development.

Nodule initiation mechanisms have mostly been studied in legumes in which bacteria enter via root hair curling (RHC) followed by intracellular invasion. However, the legume family is diverse, and many variations occur on the theme of nodulation. For instance, the tropical shrub Sesbania rostrata has versatile nodulation features as an adaptation to temporarily flooded habitats. Aeroponic roots of S. rostrata are covered with root hairs, and nodules can form in the susceptible zone I via root hair invasion according to the classic scheme. S. rostrata can skip the RHC mode of invasion and nodulate on the stem at bases of adventitious roots and also at lateral root bases (LRBs) of submerged roots. During LRB nodulation, the microsymbiont Azorhizobium caulinodans enters through cracks in the epidermis, colonizes the outer cortex, and forms intercellular infection pockets mediated by NF-induced cell death. Although both RHC and LRB invasions depend on NFs, the structural NF requirements are less stringent for LRB nodulation than for RHC (D'Haeze and Holsters, 2002; Goormachtig et al., 2004a). Thus, on the same plant, nodules can be formed at different positions and, hence, in a different physiological and hormonal context.

A major determinant for the switch between nodulation modes in S. rostrata is the gaseous hormone ethylene that accumulates upon waterlogging (Goormachtig et al., 2004a). Ethylene is a potent inhibitor of RHC invasion and of NF-induced Ca2+ spiking in M. truncatula (Oldroyd et al., 2001a). In S. rostrata, ethylene inhibits RHC invasion but positively regulates LRB nodulation and is required, together with H2O2 and gibberellic acid, for infection pocket formation and nodulation (D'Haeze et al., 2003; Lievens et al., 2005). Hence, in S. rostrata, LRB invasion allows nodulation under conditions that inhibit nodulation in zone I (Goormachtig et al., 2004b). This versatility provides a tool to investigate requirements that are specific to one invasion mode or shared between both. At the gene expression level, LRB nodulation seems simpler than the RHC mechanism (Capoen et al., 2007).

Ca2+ spiking is a key component in the activation of zone I nodulation via RHC invasion, but nothing is known about its role in legume species with alternative modes of nodulation and infection. We have assessed the importance of Ca2+ spiking during LRB nodulation in S. rostrata. Under conditions that promote LRB nodulation, NFs trigger faster Ca2+ oscillations than during RHC nodulation. Modulation of the ethylene or JA levels slowed down the Ca2+ spiking frequency and stimulated RHC invasion but was incompatible with nodule development. In parallel, we studied the function of CCaMK of S. rostrata during LRB nodulation using RNA interference (RNAi).

Our data show that, although Ca2+ spiking is a common component of the signaling pathways for RHC and LRB nodule formation, the situation is different for each type of bacterial invasion. Indeed, RHC infection is strongly correlated with Ca2+ oscillations of the appropriate frequency, while intercellular rhizobial invasion at LRBs probably functions independently of Ca2+ spiking and CCaMK.

RESULTS

Comparison of NF-Induced Ca2+ Oscillations at LRBs and in Root Zone I

As a first approach to investigate the role of Ca2+ spiking during LRB nodulation, we studied NF-induced Ca2+ oscillations in zone I and at LRBs. In aeroponic roots of S. rostrata, growing root hairs respond to azorhizobia with curling, infection thread invasion, and concomitant formation of nodules in zone I (Goormachtig et al., 2004a). To visualize Ca2+ spiking, we microinjected the Ca2+-sensitive dye Oregon Green into zone I root hairs after the root had been briefly submerged in liquid medium (see Methods). The root hairs did not respond to NFs as far as Ca2+ responses were concerned, an observation in accordance with the quick inhibition of RHC nodulation by submergence (Goormachtig et al., 2004a).

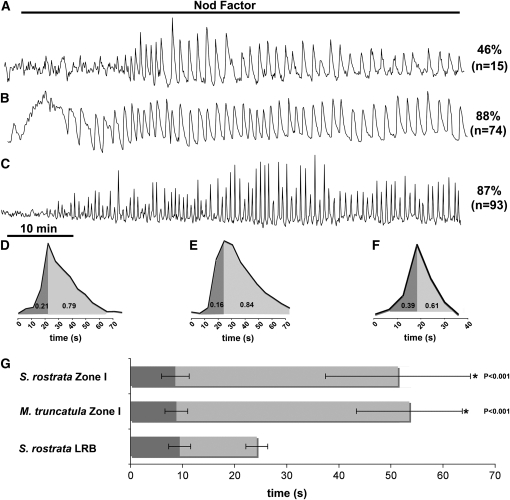

To circumvent this limitation, roots were grown hydroponically in medium supplemented with 7 μM l-α-(2-aminoethoxyvinyl)-glycine (AVG), an inhibitor of ethylene synthesis. Such roots have normal root hairs and RHC nodulation (Goormachtig et al., 2004a). Growing root hairs in zone I were microinjected with Oregon Green and subsequently exposed to NFs. Approximately 50% of the cells responded and showed Ca2+ oscillations with an average period of 179.8 ± 77.6 s and an asymmetric spike shape: the upward and downward phases corresponded to 21 and 79% of the spike duration, respectively (Figures 1A and 1D), which is similar to the spike shape in M. truncatula zone I root hairs treated with Sinorhizobium meliloti NFs (Figures 1B and 1E). The M. truncatula spikes showed a rapid increase in Ca2+ that constituted 16% of the spike duration and a slow reduction in Ca2+ levels (Figure 1E). In S. rostrata, the average period was longer than in M. truncatula (179.8 ± 77.6 s versus 92.8 ± 24.0 s), with a greater variation between cells as indicated by the higher standard deviation (77.6 s compared with 24.0 s in M. truncatula; Figures 1A, 1B, 1D, and 1E) (see also Miwa et al., 2006a).

Figure 1.

NF-Induced Ca2+ Spiking Patterns in S. rostrata Compared with a M. truncatula Reference.

(A) to (C) Representative Ca2+ spiking traces; the percentage of visualized cells that initiated Ca2+ spiking upon exposure to NFs is shown, and the number of cells tested is given in parentheses.

(A) Ca2+ spiking traces in zone I root hairs of S. rostrata.

(B) Ca2+ spiking traces in zone I root hairs of M. truncatula.

(C) Ca2+ spiking traces in root hair initials at LRBs of S. rostrata.

(D) to (F) Schematic representation of the average spike shape of traces depicted in (A) to (C), respectively. The numbers in the curve are averages of the proportion of upward and downward parts of the spike.

(G) Statistical analysis of Ca2+ spiking shapes. Average times taken from at least 30 Ca2+ spikes are presented for several traces under each condition. The upward phases (dark gray) were identical, but the downward phases (light gray) were significantly different (P < 0.001). Error bars indicate sd. Statistically significant differences in comparison with S. rostrata LRBs are indicated with an asterisk as well as the P value.

In the absence of AVG, hydroponic roots of S. rostrata have no root hairs, except at LRBs, where several root hair initials are present (Mergaert et al., 1993). At these positions, NFs trigger cortical cell division for nodule formation, cell death for invasion, as well as outgrowth and deformation of the root hair initials. However, the root hairs are not invaded by infection threads and the bacteria colonize the cortex intercellularly. Antagonists of ethylene synthesis or perception as well as inhibitors of reactive oxygen species production inhibit both NF-dependent root hair outgrowth and LRB nodulation (D'Haeze et al., 2003). As these root hair initials located at LRBs were markers for NF responses during LRB nodulation and were amenable to microinjection, we screened them for NF-induced Ca2+ spiking. NF application induced a distinct spiking signature in these root hair initials: 87% of the cells responded with an average spiking period of 55.5 ± 20.8 s (Figures 1C and 1F). The LRB-associated spikes were more symmetrical than the zone I–associated spikes in M. truncatula and S. rostrata, with upward and downward phases representing 39 and 61% of the spike duration, respectively (Figures 1F and 1G).

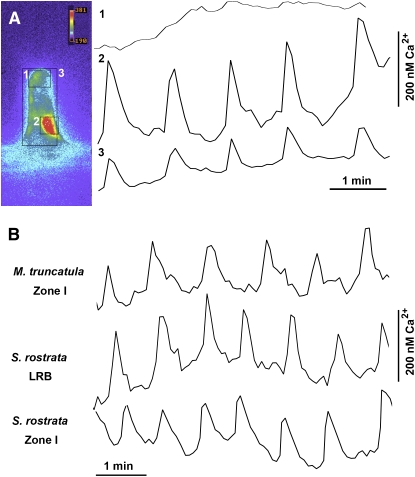

A drawback of Oregon Green as a calcium indicator is that it cannot be used to measure changes in the amplitude of Ca2+ oscillations. To address this issue, we injected the different cell types with a ratiometric calcium indicator, dextran-linked 1-[6-amino-2-(5-carboxy-2-oxazolyl)-5-benzofuranyloxy]-2-(2-amino-5-methylphenoxy) ethane-N,N,N',N'-tetraacetic acid, penta-potassium salt (Fura-2). Amplitudes were measured in zone I cells of M. truncatula (n = 3) and in LRB cells of S. rostrata under hydroponic conditions without (n = 6) and with 7 μM AVG (n = 5). All spikes analyzed confirmed the nuclear localization of NF-induced Ca2+ spiking and an amplitude (200 to 250 nM) similar to published data (Figure 2A) (Walker et al., 2000). Thus, the NF-induced Ca2+ oscillations had similar amplitudes in all tested tissues (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Fura-2 Calibration of Ca2+ Spiking.

(A) Image of a M. truncatula root hair injected with dextran-linked Fura-2, showing the (peri-)nuclear localization of the calcium responses. Squares 1, 2, and 3 mark the different areas where the measurements were made to produce the traces on the right: (1) Ca2+ changes in the root hair tip during a typical experiment, (2) Ca2+ oscillations when only the nucleus is considered, and (3) an average for the whole root hair.

(B) Representative traces for Ca2+ spiking events in all cell types discussed, visualized with the Fura-2 ratiometric dye. Traces are given for M. truncatula root hairs (cells tested n = 3) and S. rostrata cells under hydroponic conditions without (LRB, n = 6) and with 7 μM AVG (zone I, n = 5). No significant amplitude differences can be seen.

Phospholipase D (PLD) and Ca2+-ATPases have been implicated in NF-induced Ca2+ spiking and gene expression in root hairs of M. truncatula (den Hartog et al., 2001, 2003; Engstrom et al., 2002). We used the Ca2+-ATPase antagonists cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) and 2,5-di-t-1,4-benzohydroquinone (BHQ) and the PLD antagonist n-butanol to assess whether similar mechanisms are involved in the generation of LRB-associated Ca2+ spiking. Both CPA and BHQ inhibited NF-induced LRB Ca2+ spiking in S. rostrata (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). Suppression by BHQ was transient, with spontaneous reversion of the Ca2+ spiking within ∼10 min after application, similarly to what was observed in M. truncatula (Engstrom et al., 2002). The primary alcohol n-butanol can accept the phosphatidyl moiety produced by PLD, resulting in a decreased production of phosphatidic acid, in contrast with tert-butanol that provides a valuable control (Parmentier et al., 2003). Addition of 0.5% n-butanol reversibly inhibited LRB-associated Ca2+ spiking, whereas tert-butanol had no effect (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). These data suggest that similar mechanisms generate Ca2+ spiking in zone I root hairs and in root hair initials at LRBs.

Hormonal Modulation of the LRB-Associated Ca2+ Signature Correlates with Root Hair Invasion and Loss of Nodulation

Ca2+ spiking in M. truncatula root hairs is influenced by hormones. Ethylene has an inhibitory effect because addition of the ethylene biosynthesis precursor 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid blocks NF-induced Ca2+ spiking, while the ethylene biosynthesis inhibitor AVG enhances the number of cells responsive to both Ca2+ spiking and intracellular infection (Oldroyd et al., 2001a). JA application also abolishes Ca2+ spiking, or, at lower concentrations, extends the period of the individual Ca2+ spikes (Sun et al., 2006).

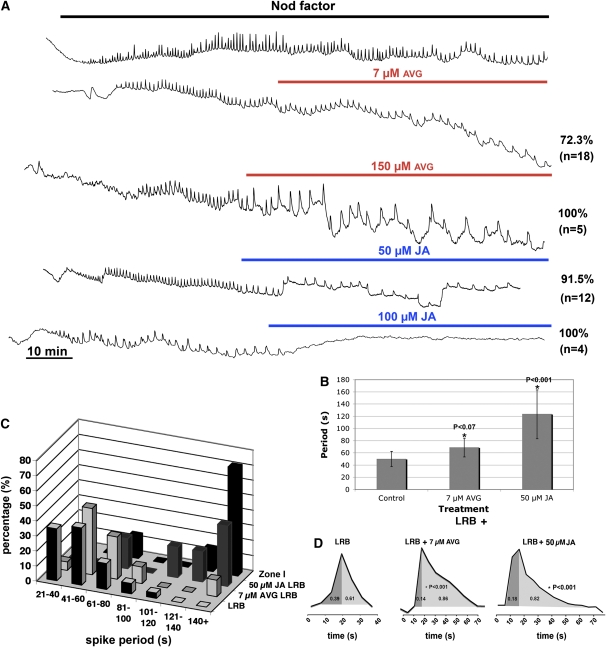

We assessed the effect of these two hormones on the NF-induced Ca2+ spiking responses at LRBs of S. rostrata. Quantification of the distribution of spiking signatures showed that the average spiking period of root hair initials at LRBs tended to be short; however, it was extended by treatment with 7 μM AVG or 50 μM JA to lengths observed in zone I of S. rostrata or M. truncatula (Figures 3A to 3C). Ca2+ spiking was strongly affected by 150 μM AVG and totally abolished by 100 μM JA (Figure 3A). Addition of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid in concentrations ranging from 40 to 1000 μM had no effect.

Figure 3.

Hormonal Influences on NF-Induced Ca2+ Spiking Signatures.

(A) Representative examples of altered traces observed in root hair cells at LRBs after treatments with AVG and JA. Concentrations are indicated above the relevant trace; the top trace is a reference, showing NF-induced Ca2+ spiking in untreated roots. The frequency is reduced without inhibition of Ca2+ spiking by 7 μM AVG and 50 μM JA. Spiking is strongly affected by 150 μM AVG and is totally inhibited by 100 μM JA. The percentage of visualized cells that initiated Ca2+ spiking is shown, and the number of cells tested is given in parentheses.

(B) Effect of treatment with 7 μM AVG and 50 μM JA on the average period of Ca2+ spiking. Error bars indicate sd. Statistically significant differences between treatment and control are indicated with an asterisk as well as the P value.

(C) Shift in distribution of Ca2+ spiking periods at LRBs toward the distribution found in zone I root hairs after treatment with 7 μM AVG or 50 μM JA. For each treatment, the percentage of cells with a period in the indicated range was plotted against their spiking periods, and the spiking period was compared between the different treatments.

(D) Schematic representation of spike shapes derived from several representative traces. The numbers in the curves are average proportions of upward and downward segments of the spikes. A statistically significant difference was observed for the downward phase of AVG-treated compared with untreated root hairs at LRBs (indicated with an asterisk; the P value is also shown). [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Hence, Ca2+ spiking at LRBs was suppressed or slowed down by JA, while increased ethylene levels did not affect the LRB signature; by contrast, interference with ethylene biosynthesis by the addition of AVG retarded the Ca2+ spiking frequency. Treatment with 7 μM AVG also changed the shape of the Ca2+ spike, by expanding the second phase, resulting in more asymmetrical spikes that resembled those in M. truncatula or S. rostrata zone I root hairs (Figure 3D).

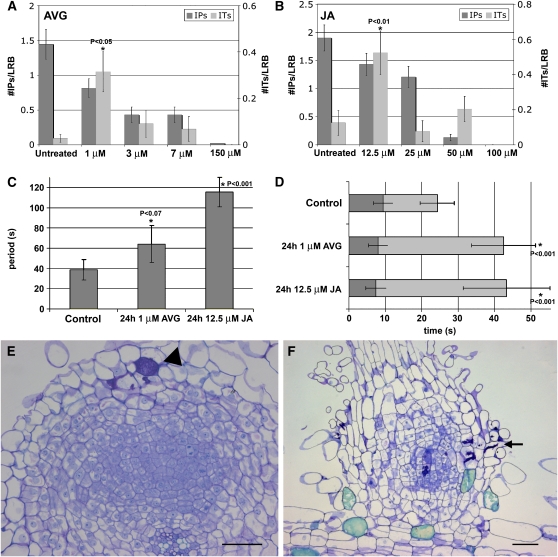

Because application of AVG or JA shifts the Ca2+ spiking signature at LRBs, we wanted to investigate the effect of the hormones on nodulation and on rhizobial invasion. For a quantitative analysis, hydroponic roots were pretreated for 24 h with different concentrations of AVG or JA before inoculation with A. caulinodans strain ORS571 (pRG960SD-32) that expresses the β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene uidA. Three days after inoculation (DAI), roots were stained for GUS and LRBs were excised for stereomicroscopy observation. Ten plants were used per treatment, and four or five LRBs per root were scored for numbers of intercellular infection pockets and intracellular infection threads. The data (Figures 4A and 4B) demonstrate that pretreatment with low concentrations of AVG or JA stimulated intracellular invasion of the root hairs. In control roots, infection threads were observed only very occasionally. Treatment with 1 μM AVG or 12.5 μM JA significantly increased the number of infection threads in root hairs and decreased the number of intercellular infection pockets (Figures 4A and 4B). Both infection thread and infection pocket formation were reduced by higher concentrations of AVG and JA and completely inhibited by 150 or 100 μM JA.

Figure 4.

Effects of AVG on LRB Nodulation and Bacterial Invasion.

(A) Graphs showing the effect of 24-h pretreatment at several AVG concentrations on infection pocket (IP) and infection thread (IT) formation. The dark- and light-gray bars show the number of IPs and ITs per LRB, respectively, as observed under stereomicroscopy. A significant increase in ITs can be seen after pretreatment with 1 μM AVG when compared with the untreated control plants (indicated with an asterisk; the P value is also given). Error bars indicate sd.

(B) As for (A) but for JA pretreatment. A significant increase in ITs can be seen after pretreatment with 12.5 μM JA when compared with the untreated control plants (indicated with an asterisk; the P value is also shown). Error bars indicate sd.

(C) Effect of 24-h pretreatment with 1 μM AVG and 12.5 μM JA on the average period of Ca2+ spiking. Error bars indicate sd. A significant change can be seen after pretreatment with 1 μM AVG and 12.5 μM JA when compared with the untreated control plants (indicated with an asterisk; the P value is also shown).

(D) Statistical analysis of the change in Ca2+ spike shapes after 24-h pretreatment with either 1 μM AVG or 12.5 μM JA. The dark and light bars represent the upward and downward part of the spike, respectively. Error bars indicate sd. A significant change can be seen in the 1 μM AVG and 12.5 μM JA pretreatments compared with the untreated control plants (indicated with an asterisk; the P value is also shown).

(E) and (F) Semithin sections of a developing LRB nodule at 3 DAI with A. caulinodans (E) and pretreated for 24 h with 7 μM AVG before inoculation with A. caulinodans (F). Typical features of nodule development and the changes that occur upon hormonal pretreatment are noticeable at the light microscopic level. Arrowhead and arrow indicate infection pocket and infected root hair, respectively. Bars = 100 μm.

Previously, 7 μM AVG had been shown to block LRB nodulation completely (D'Haeze et al., 2003). Similar observations were made upon JA treatment. Treatment with 25 μM JA reduced the number of LRB nodules by 75% (on average 11.4 nodules on untreated roots versus 2.6 nodules on treated roots).

The concentrations of AVG and JA that affected bacterial invasion and nodule formation were in general lower than those required for the Ca2+ spiking switch. Presumably, the 24-h pretreatment in the nodulation experiments improved penetration of the compounds, whereas in the Ca2+ spiking analysis, the effects were measured 10 min after addition of AVG and JA. To examine this possible explanation, we pretreated hydroponic roots for 24 h at the low concentrations used in the infection assays (Figures 4C and 4D) and visualized Ca2+ spiking upon application of NFs. Indeed, 24 h of pretreatment with 1 μM AVG (n = 7) and 12.5 μM JA (n = 7) significantly extended the spiking period compared with untreated cells (n = 10) (Figure 4C) and shifted the spike shape to one resembling that after 10-min high-concentration treatment (Figures 3D and 4D). Hence, 24-h pretreatments at low concentrations and minute-long treatments at high concentrations have similar effects on Ca2+ spiking, suggesting that penetration of the compounds is not immediate and is dose dependent.

A semithin section through a control (Figure 4E) and an AVG-pretreated (Figure 4F) sample illustrate the differences in the LRB responses to A. caulinodans inoculation at the microscopic level. Whereas in the control a nodule develops opposite infection pockets (Figure 4E), pretreatment with 7 μM AVG interfered with nodule development and infection pocket formation, but led to invaded root hairs (Figure 4F). Limited cell division was occasionally seen (as in Figure 4F), but nodules never developed.

Together, these observations suggest that intracellular root hair invasion is associated with a particular NF-induced Ca2+ signature. Indeed, shifting the fast spiking pattern at LRBs toward slower frequencies, resembling the default signature in susceptible zone I root hairs, correlated with intracellular infection threads; however, the same conditions were incompatible with nodule initiation opposite these root hair infection sites.

S. rostrata CCaMK Expression during LRB Nodulation

CCaMK is a critical component of the NF signaling pathway and presumably functions in decoding NF-induced Ca2+ spiking. To assess whether Ca2+ spiking decoding is relevant for LRB nodulation, we investigated the role of CCaMK. To identify S. rostrata CCaMK, the CCaMK cDNA sequences of M. truncatula, pea, rice (Oryza sativa), and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) were aligned. PCR primers were designed to amplify a well-conserved CCaMK region from a S. rostrata nodule cDNA library. A full-length cDNA clone was isolated by rapid amplification of cDNA ends. The corresponding protein of 522 amino acids was most homologous to L. japonicus CCaMK and M. truncatula DMI3, with 90.4 and 89.0% amino acid similarity, respectively. The putative protein had a kinase domain with a conserved Thr (Thr-270) for autophosphorylation, a CaM binding domain, and three EF hand domains for Ca2+ binding at the C terminus (see Supplemental Figure 2A online). DNA gel blot hybridization with a 652-bp probe containing the CaM binding domain showed only one band after genomic DNA digestion with different restriction enzymes, indicating that S. rostrata CCaMK is a single gene. A 1824-bp promoter region upstream of the start codon was isolated from genomic DNA of S. rostrata and fused to the cDNA sequence. The resulting construct was introduced into roots of the nodulation-defective M. truncatula dmi3-1 mutant by Agrobacterium rhizogenes transformation. Transgenic roots were inoculated with S. meliloti 1021, and functional nodules were observed (see Supplemental Figure 2B online) in five out of six transgenic roots. The complementation nodules had a normal morphology, with an apical meristem, infection zone, and a large fixation zone with cells fully occupied by symbiosomes (see Supplemental Figure 2B online). Hence, S. rostrata CCaMK is the functional ortholog of the M. truncatula CCaMK.

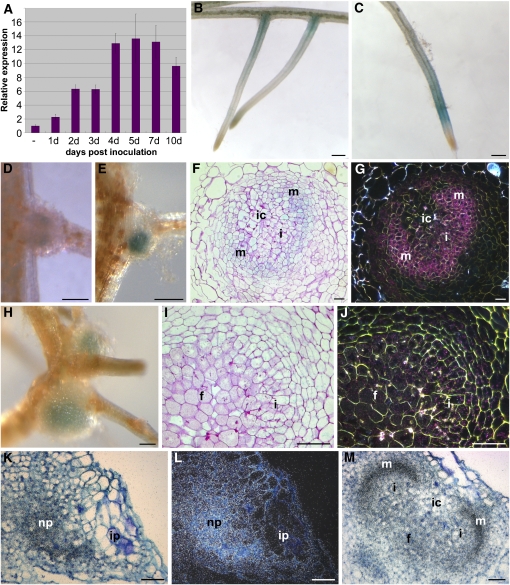

S. rostrata CCaMK transcripts were present in adventitious rootlets, and the transcript level gradually increased during stem nodulation, with a maximum at 4 to 5 DAI (Figure 5A). To localize the expression of CCaMK, the 1824-bp promoter region was used to drive the transcription of the uidA reporter gene. In uninoculated transgenic roots, GUS staining was observed in zones that are potentially responsive to nodulation, i.e., at the LRBs (Figure 5B) and in root zone I (Figure 5C). At 2 DAI with A. caulinodans, the promoter was active in the nodule primordia at LRBs (Figure 5D). One day later, when zonation was initiated, CCaMK was still expressed in the nodule primordium (Figure 5E). Sectioning indicated that GUS was found mainly in the developing nodule and was low in cortical cells of the infection center (Figures 5F and 5G). In maturing nodules, CCaMK was associated with the infection zone and, to a lesser extent, the fixation zone (Figures 5H to 5J).

Figure 5.

Expression Analysis of S. rostrata CCaMK during LRB Nodule Development.

(A) qRT-PCR on developing stem nodules, relative to the constitutive S. rostrata UBI1. Tissues used are peels taken from the stem containing the dormant adventitious roots that were treated as described. Error bars indicate sd (n = 3).

(B) to (J) CCaMK:GUS expression in S. rostrata hydroponic roots. GUS staining is visible in uninoculated roots ([B] and [C]) and at 2 (D), 3 (E), and 6 (H) DAI with A. caulinodans ORS571. Microscopic sections are shown of 4-d-old ([F] and [G]) and 6-d-old ([I] and [J]) developing nodules viewed under bright-field and dark-field optics (signals seen as blue and pink spots, respectively).

(K) to (M) In situ transcript localization of CCaMK during stem nodule development at 3 ([K] and [L]) and 4 (M) DAI. In bright-field and dark-field images, signals are seen as black and white spots, respectively.

f, fixation zone; i, infection zone; ic, infection center; m, meristem; np, nodule primordium. Bars = 500 μm in (B) to (E) and (H) and 100 μm in (F), (G), and (I) to (M).

A similar pattern of CCaMK expression was observed in adventitious root nodules on S. rostrata stems by means of RNA in situ analysis. At the early stages of nodule development, cells of the nodule primordium accumulated CCaMK transcripts (Figures 5K and 5L), with the strongest transcript accumulation near the meristem and weakest expression in the infection zone and in nitrogen-fixing cells (fixation zone). Very low CCaMK expression was observed around bacterial infection pockets or progressing intercellular infection threads in the outer cortex (Figures 5K and 5L) or in the infection center (Figure 5M). This observation revealed that CCaMK expression correlated strongly with nodule development and was low in cortical cells during intercellular rhizobial invasion.

Knockdown of S. rostrata CCaMK Arrests Nodule Development but Not Intercellular Colonization

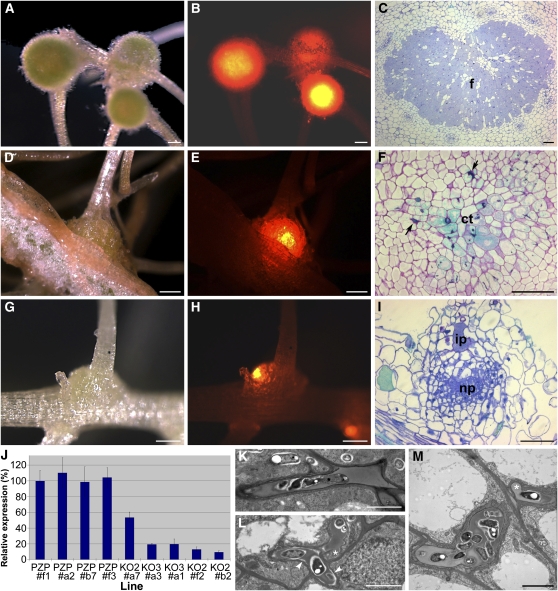

To investigate the function of CCaMK during LRB nodulation, we reduced CCaMK transcript levels in transgenic S. rostrata roots by RNAi. Two constructs covering regions of ∼200 bp (CCaMK-KO2 and CCaMK-KO3) were introduced into S. rostrata by transformation with A. rhizogenes 2659 (Van de Velde et al., 2003). Plants with transgenic roots, identified by green fluorescent protein (GFP) cotransformation, were transferred to tubes with nitrogen-deprived Norris medium and inoculated with A. caulinodans ORS571 (pBHRdsREDT3) after 9 to 14 d. In control transgenic roots transformed with the empty vector (n = 34), developing nodules at LRBs were observed at 4 DAI; mature determinate nodules formed by 7 DAI (Figures 6A and 6B). In lines transformed with either of the two knockdown constructs (n = 99), 59% of the transgenic roots developed normal nodules; in 25%, the nodulation level was strongly reduced with nodules smaller than those of the controls. Nevertheless, these small nodules contained bacteria (Figures 6D and 6E). In the remaining 16% of transgenic roots, only small bumps were observed that were, nevertheless, colonized by bacteria (Figures 6G and 6H).

Figure 6.

CCaMK RNAi Knockdown Phenotypes in S. rostrata Hairy Roots.

(A) to (I) Root nodule at 7 DAI grown on a control line ([A] to [C]) and a moderate KO2 a7 ([D] to [F]) and strong KO2 b2 ([G] to [I]) CCaMK knockdown line. A bright-field image (left column), a dsRED fluorescence image (depicting bacteria; middle column), and a microscopic section (right column) are shown in each row. Arrows in (F) indicate broad infection threads.

(J) Relative CCaMK expression level of knockdown root lines (KO2 and KO3) compared with controls (empty PZP vector), as obtained from qRT-PCR with constitutive Sr UBI1. Error bars indicate sd (n = 3).

(K) to (M) TEM images of infection thread structures in a control (K) and in CCaMK knockdown nodules ([L] and [M]). Arrowheads and asterisks indicate low electron-dense rims and bulges in infection threads, respectively.

ct, central tissue; f, fixation zone; ip, infection pocket; np, nodule primordium. Bars = 500 μm in (A), (B), (D), (E), (G), and (H), 100 μm in (C), (F), and (I), and 2 μm in (K) to (M).

CCaMK transcript levels were determined using quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) in a subset of the lines with small nodules (n = 10), mere bumps (n = 8) and in control lines (n = 6) (Figure 6J). A strong correlation was found between the degree of transcript reduction and the severity of the phenotype. Lines with the strongest decrease in expression (lower than 20%; e.g., KO3#a3, KO3#a1, KO2#f2, and KO2#b2) formed only bumps (Figures 6G-I), whereas those with moderately reduced expression (between 55 and 20%, such as KO2#a7) had small nodule-like structures (Figures 6D-F). Hence, a decrease in CCaMK transcript numbers in transgenic RNAi roots had a dosage-dependent effect on the nodule size, meaning that nodule development was hampered.

Light and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) showed that the central tissue of nodules in lines with a moderately reduced CCaMK expression (such as KO2#a7) had a few infected cells at 7 DAI, most of which were not completely filled with symbiosomes (cf. Figures 6F and 6C). Some infection threads in the infection center were abnormally broad (Figure 6F). TEM analysis indicated that these infection threads had aberrant shapes with bulged outgrowths and often a rim of low electron-dense material at the walls (Figures 6L and 6M, in comparison with Figure 6K). Nodules that appeared on an incidental GFP-negative root of these lines provided an internal control: they had a normal size and a central tissue with many fixing cells that were completely filled with bacteroids, identical to lines transformed with an empty vector (Figure 6C). In transgenic roots with strongly reduced CCaMK expression, only a few cortical cells divided at 7 DAI, but the cortex at the LRBs was colonized by bacteria in infection pockets (Figure 6I) and aberrant infection threads occurred.

In conclusion, the phenotypes observed in CCaMK RNAi knockdown roots show that nodule development and infection thread progression were severely disturbed and nodule-like structures contained few or almost no bacteroids in the central tissue, but intercellular invasion of the cortex with infection pocket formation was hardly affected.

DISCUSSION

Several lines of evidence link Ca2+ spiking in zone I root hairs of legume roots to NF signaling for nodulation. First, NFs from incompatible rhizobia or NFs lacking key modifications are unable to induce proper Ca2+ oscillations (Ehrhardt et al., 1996; Oldroyd et al., 2001a, 2001b). Second, plant mutants that are blocked at the earliest stages of the symbiosis are impaired in NF-induced Ca2+ spiking, including mutations in genes coding for the putative LysM-type NF receptors, putative ion channels, a membrane-bound leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase, and components of the nucleoporin complex, functions presumably involved in generating or regulating spiking downstream of the NF perception (Catoira et al., 2000; Ben Amor et al., 2003; Madsen et al., 2003; Radutoiu et al., 2003; Imaizumi-Anraku et al., 2005; Kanamori et al., 2006; Miwa et al., 2006a; Saito et al., 2007). Third, one of the essential nodulation genes encodes a CCaMK protein (Catoira et al., 2000; Miwa et al., 2006a), a strong candidate for decoding the Ca2+ signal that leads to transcriptional changes. Moreover, gain-of-function mutations of CCaMK result in spontaneous nodule formation (Gleason et al., 2006; Tirichine et al., 2006). Besides these genetic data, several physiological lines of evidence are available. For instance, inhibitors of Ca2+ spiking suppress the induction of nodulin genes, such as early nodulin 11 (ENOD11) (Pingret et al., 1998; Engstrom et al., 2002; Miwa et al., 2006b), and, on average, ∼36 uninterrupted spikes are required to allow ENOD11 expression (Miwa et al., 2006a).

Until now, the role of Ca2+ spiking in symbiosis had been studied exclusively in legumes with zone I nodulation and intracellular invasion in growing root hairs. S. rostrata presents an alternative nodulation that differs in position, physiological environment, invasion mode, and the need for ethylene and has less stringent NF structural requirements (Goormachtig et al., 2004a). During LRB nodulation in S. rostrata, bacterial invasion skips the epidermis, allowing the study of the role of NF signaling components in the intercellular colonization of the cortex.

Here, we examined Ca2+ spiking patterns at LRBs and in root zone I of S. rostrata, and, in parallel, we studied the role of S. rostrata CCaMK in LRB nodulation. The outer cortical cells, where invasion takes place, were not amenable for microinjection with a Ca2+-sensitive dye. The only accessible targets were root hair initials present at LRBs of the otherwise hairless hydroponic roots. These epidermal cells respond to NFs and to bacterial inoculation by outgrowth and deformation, but they do not become invaded. Just like LRB nodulation, this response depends on NFs, H2O2, and ethylene (D'Haeze et al., 2003). As these root hair initial responses have the same signaling requirements as nodulation at LRBs, we used these cells to analyze Ca2+ spiking. We found that spike shape and frequency were different in LRB cells and zone I root hairs. The Ca2+ spiking at LRBs was faster than in zone I, and the shape of the spikes was more symmetrical (Figure 1). Despite these differences, a pharmacological analysis suggests a similar underlying mechanism for the generation of RHC- and LRB-associated Ca2+ spiking patterns, involving phospholipid signaling and Ca2+-ATPases (see Supplemental Figure 1 online).

The LRB Ca2+ spiking pattern could be modulated by altering hormone levels. As observed in M. truncatula (Sun et al., 2006), JA extended the period of Ca2+ spikes. In contrast with the situation in M. truncatula (Oldroyd et al., 2001a), excess ethylene had no effect on LRB Ca2+ spiking; on the contrary, inhibition of ethylene production either blocked it, or, at low concentrations, extended its period. Increased JA levels or reduced ethylene levels also affected the spike shape, rendering it more asymmetric, thus shifting the signature toward the pattern observed in zone I root hairs. Modulating the levels of these hormones prominently influenced the downward phase of the Ca2+ spike, which is associated with the resequestration of Ca2+ into the internal store (Figure 3). Therefore, the target for ethylene and JA might be the Ca2+-ATPase that functions in the reuptake of calcium.

Interestingly, the hormonal modulations that conferred zone I identity to the Ca2+ spiking pattern at LRBs stimulated infection thread formation. In the absence of AVG or JA, intracellular infection threads were rarely observed. At low concentrations, AVG or JA promoted intracellular invasion in root hairs, whereas at high concentrations they negatively affected LRB nodulation and reduced the number of both infection pockets and infected root hairs. With Fura-2 as a ratiometric dye, no significant amplitude differences were found between the cell types, indicating that shape and period are the determining factors for the shift in infection strategy (Figures 2 and 4). These findings correlate a defined Ca2+ spiking profile with the capacity for intracellular root hair invasion, be it in a zone I or in a LRB developmental context. The hormonal changes negatively affected LRB nodule development and infection pocket formation (Figures 4E and 4F), which could be caused either via the altered spiking signature or directly by the modified hormone levels.

Additional data were obtained from the study of the role of CCaMK in LRB nodulation. CCaMK proteins are plausible candidates to interpret the NF-triggered Ca2+ signature and to transmit information for gene expression, nodule formation, and infection thread progression. A S. rostrata CCaMK cDNA clone, corresponding to a unique gene, complemented the dmi3-1 mutation of the M. truncatula CCaMK gene. qRT-PCR demonstrated that expression of CCaMK is upregulated during nodulation at adventitious root bases. A promoter-GUS reporter construct and in situ hybridization revealed expression in nodule primordia and in the proximal cells of the meristematic zone of developing nodules (Figure 5). In M. truncatula nodules, CCaMK, DMI1, and DMI2 transcripts are localized in the apical preinfection zone (Bersoult et al., 2005; Limpens et al., 2005; Riely et al., 2007), and DMI2 and NFP promoter activity has been observed in the nodule primordium prior to penetration by infection threads (Bersoult et al., 2005; Arrighi et al., 2006).

Interestingly, downregulation of CCaMK expression by RNAi severely interfered with nodule formation but hardly affected the primary intercellular cortical invasion. The degree of transcript reduction and the impairment of nodule development correlated well. Lines with <20% residual transcripts merely developed small bumps at the LRBs, implying that CCaMK is important for nodulation. All suppressed lines had large infection pockets and intercellular infection threads, suggesting that signaling via CCaMK is not essential to initiate these structures (Figure 6). However, intracellular cortical infection threads were abnormal, resembling the lumpy structures observed in S. rostrata SYMRK knockdown lines and wild-type plants upon invasion with NF-deficient bacteria (Figure 6) (Capoen et al., 2005; Den Herder et al., 2007). Thus, proper infection thread progression in S. rostrata requires cell-autonomous NF perception with signal transduction that involves both CCaMK and, as shown previously, SYMRK (Capoen et al., 2005).

Our data show that initiation and development of nodule primordia at LRBs require CCaMK and that CCaMK plays a role in the progression of infection threads (Figure 6). The similar requirements for CCaMK in RHC nodulation in M. truncatula (Lévy et al., 2004) allow us to conclude that Ca2+ oscillations are a basic component in nodule primordia initiation and infection thread progression both in an RHC and LRB context. Different Ca2+ signatures are associated with RHC and LRB nodulation, but, at present, we cannot conclude whether the Ca2+ spiking pattern observed in root hair initials is representative of the pattern in cortical cells during LRB nodulation.

Rhizobial invasion via RHC depends on CCaMK (Catoira et al., 2000; Tirichine et al 2006). Here, we report that this type of invasion correlates with a specific Ca2+ spiking pattern, suggesting that a frequency-dependent phosphorylation of CCaMK targets might be an important step in this process. By contrast, infection pocket formation seems independent of CCaMK (Figure 6), implying a mechanism for the initiation of cortical cell death that does not depend on Ca2+ oscillations.

Based on these observations, we propose a model with a dual pathway downstream of the primary NF perception at LRBs. NF perception by specific receptors would cause Ca2+ spiking, of which the decoding by CCaMK is essential for nodule formation. In parallel, NF perception generates secondary signals that, independently of Ca2+ spiking, are essential for the outer cortex colonization with infection pocket formation. Plausible mediators of these primary intercellular invasion events are H2O2 and ethylene (D'Haeze et al., 2003).

Our data also confirm the key role for ethylene in submergence-adapted nodulation in S. rostrata: under waterlogged conditions, when ethylene accumulates, RHC nodulation in zone I is suppressed (D'Haeze et al., 2003), while LRB nodulation that requires ethylene is prevalent. We demonstrate that the root hairs present on hydroponic roots can perceive NFs but cannot mount a calcium response with the appropriate period for root hair infection, presumably because of inhibiting hormones that accumulate in hydroponic roots. This problem is circumvented via a Ca2+-independent intercellular infection pathway with infection pocket formation allowing the accumulation of sufficient numbers of rhizobia to generate a greatly amplified signal for further nodule invasion.

In conclusion, we have shown that ethylene and JA modulate the Ca2+ oscillations that are activated by rhizobial NFs at LRBs of S. rostrata and that a specific Ca2+ signature correlates well with the intracellular invasion mode. The physiological context and, in particular, the ethylene concentration, influences Ca2+ spiking and the choice of the developmental pathway that is activated by NF signaling in S. rostrata, thus contributing to the phenotypic plasticity that is characteristic of nodulation of this tropical legume.

METHODS

Biological Material

Sesbania rostrata Brem seedlings were germinated and grown in tubes with liquid medium (hydroponic roots) or in Leonard jars (aeroponic roots) according to the procedures described (Fernández-López et al., 1998). Medicago truncatula A17 seedlings were germinated and grown as described (Sun et al., 2006). Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS571 labeled with the red fluorescent protein (DsRED; Clontech) was obtained by introducing the plasmid pBHRdsREDT3 (Smit et al., 2005) into A. caulinodans ORS571 by electroporation. The A. caulinodans ORS571 (pBHRdsREDT3), ORS571 (pBBR5-hem-gfp5-S65T) (D'Haeze et al., 2004), and ORS571 (pRG960SD-32) (D'Haeze et al., 1998) strains were grown on yeast extract broth medium with appropriate antibiotics (Van den Eede et al., 1987). NFs were purified from A. caulinodans cultures as previously described (Mergaert et al., 1993).

Ca2+ Spiking Analysis

For Ca2+ spiking analysis (Ehrhardt et al., 1996; Wais et al., 2000), micropipettes were made from borosilicate capillaries with an electrode puller (model 773; Campden Instruments). Needles were preloaded with either dextran-linked Fura-2 or Oregon Green and Texas Red (10,000 molecular weight; Molecular Probes). Cells were injected via iontophoresis with a cell amplifier (model Intra 767; World Precision Instruments) and a stimulus generator (World Precision Instruments).

Plants were mounted on slides containing buffered nodulation medium (Ehrhardt et al., 1992) for microinjection of suitable root hairs and subsequent imaging. After microinjection, cells were visualized for 10 min to verify viability; only cells that still showed cytoplasmic streaming were challenged with 10 pM purified A. caulinodans or Sinorhizobium meliloti NFs. For visualization, an inverted epifluorescence microscope (TE2000; Nikon) equipped with a monochromator (Optoscan; Cairn Research) was used. Cells were imaged with a CCD camera (ORCA-ER; Hamamatsu) and an image splitter (Optosplit; Cairn Research). Subsequently, data were analyzed with MetaFluor software (Universal Imaging). All traces shown are the fluorescence intensity ratio of Oregon Green to Texas Red; although not considered a ratiometric method, all intensity shifts caused by cytoplasmic streaming in the cells being visualized were canceled out.

For Fura-2 calibrations, measured ratios were calibrated in vitro with a series of standards using the Fura-2 Ca2+ calibration kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). The emission ratio was linear for calcium concentrations within a biologically relevant range (0 to 650 nM).

For the pharmacological tests on Ca2+ spiking at LRBs, concentrations of compounds were 1, 3, 7, or 150 μM AVG (Sigma-Aldrich); 12.5, 25, 50, or 100 μM JA (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.5% (v/v) n-butanol (Sigma-Aldrich), and 10 μM CPA (Sigma-Aldrich). Spiking cells were visualized for at least 30 min before addition of the compounds, and changes were measured 10 min afterward to avoid transition effects.

To obtain zone I root hairs on hydroponic roots, S. rostrata seedlings were germinated overnight and directly transferred to 7 μM AVG. Spiking was tested 7 to 10 d later.

Excel software (Microsoft) was used for statistical analysis of the Ca2+ spiking experiments. To measure the frequencies and periodicity of the spikes, the time between Ca2+ spike maxima was measured and averaged, and the standard deviations were subsequently calculated. For the spike shape analysis, individual spikes were assessed for the time to reach a maximum from baseline (the upward slope) to the time to return to baseline (the downward slope). Typically, for all statistical analyses, at least 30 spikes were measured from a minimum of five traces. When necessary, we ascertained statistical significance with t tests assuming unequal variance.

Some traces were detrended with a moving average. The number of points used in the moving average is particular to each trace and was chosen to be as low as possible while retaining features of interest. Outliers in the traces were removed and replaced with linear interpolation (Brockwell and Davis, 2002). The number of points used to calculate the moving average for every trace are 150 for M. truncatula, 19 for S. rostrata, 25 for 7 μM AVG, 25 for LRB (Figure 1), and 25 and 19 for BHQ and CPA, respectively (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). It should be noted that this detrending differs from the derivation often used in the literature on NF-induced Ca2+ spiking literature: Y = X(n+1)-Xn, where Y is the point-to-point change in fluorescence, and X(n+1) and Xn are the intensity measurements at time points (n + 1) and (n) (Wais et al., 2000). This formula was not used in this study.

Pharmacological Assays on LRB Nodulation

All experiments were repeated at least twice per time point. Stock solutions (1000×) of AVG (Sigma-Aldrich) and JA (Sigma-Aldrich) were made according to the manufacturer's instructions, and equal amounts of the solvent were tested as controls. Compounds were added 6 d after germination, and 24 h after their addition, S. rostrata seeds were inoculated with A. caulinodans ORS571 (pRG960SD-32). At the concentrations used, neither the solvents nor the inhibitors influenced growth of plants and bacteria. For the statistical analysis of the infection assays (Figure 4), frequencies of infection thread and infection pocket formation were analyzed by generalized linear modeling, using a logarithmic link function and a Poisson distribution of frequencies in the Genstat software suite (Payne and Lane, 2005).

Microscopy

Roots were stained for GUS activity as previously described (D'Haeze et al., 1998) before overnight clearing in a chloral hydrate solution (Sabatini et al., 1999). Subsequently, infection threads and infection pockets were counted under a stereomicroscope. For semithin sectioning and light microscopy, LRBs were excised and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and embedded in Technovit 7100 (Kulzer Histo-Technik). Sections of 4 μm were cut, stained with toluidine blue or Ruthenium Red, mounted with Depex (Sigma-Aldrich) (Den Herder et al., 2007), and analyzed with a Diaplan bright-field microscope (Leitz). GFP and dsRED analyses (Van de Velde et al., 2003) and TEM (D'Haeze et al., 1998) were done as described.

Identification of the S. rostrata CCaMK Promoter and Open Reading Frame

Nested primers were chosen in conserved regions of CCaMK proteins from other plant species. RT-PCR on S. rostrata nodule cDNA revealed a 652-bp fragment. The full-length sequence was obtained by 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (Smart RACE cDNA amplification kit; Clontech), and the complete open reading frame was amplified with primers SrDmi3FLS (5′-GGGAATTCAAAGACTTGAT-3′) and SrDmi3FLAS (5′-GATGCAATAAAAACTAAATTTGGAAG-3′) and anchored into the pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). The full-length open reading frame was transferred to the pDONR221 entry vector (Invitrogen).

The S. rostrata CCaMK promoter was identified with the Universal GenomeWalker kit (Clontech) applied to genomic DNA, and the 1824-bp region upstream of the start codon was amplified with primers attB4-SrDMI3promFullS (5′-GGGGACAACTTTGTATAGAAAAGTTGTGATGGACCACTTTG-3′) and attB1-SrDMI3promFullAS (5′-GGGGACTGCTTTTTTGTACAAACTTGGTGGTGCACAAAACA-3′) and recombined in the pDONR P4-P1 (Invitrogen).

Expression Analysis of S. rostrata CCaMK

qRT-PCR was performed with primers Dmi3-Q2S (5′-TTTCATTGCTCCGTCTAATCGC-3′) and Dmi3-Q2AS (5′-GCTTTGCTGATTGGGAAATGCC-3′) or Dmi3-Q3S (5′-AACAAAAGGTGGAGAGAAAAGC-3′) and Dmi3-Q3AS (5′-ACAAGGCATCTGAGACTGAAAC-3′) on the Lightcycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics) with the SYBR Green I master mix (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The constitutively active S. rostrata UBI1 gene was amplified with primers SrUBI1Q-S (5′-GGGAAGCAGTTGGAGGATGG-3′) and SrUBI1Q-AS (5′-AGACGCAGAACAAGGTGAAGG-3′) (Capoen et al., 2007) to determine relative values with the qBase software (Hellemans et al., 2007). One representative result from three biological repeats is shown.

To analyze the promoter-GUS activity, the Multisite Gateway three-fragment vector construction kit (Invitrogen) was used to fuse the promoter with the uidA gene (in pDONR207-GUS) and the T35S terminator (in pENTR-R2-T35S-L3) into vector pKm43GW-rolD for coexpression with GFP. To obtain transgenic roots, S. rostrata embryonic axes were transformed (Van de Velde et al., 2003). A 652-bp region was used as template to produce a 35S-labeled antisense probe for the in situ hybridization that was performed according to Goormachtig et al. (1997).

RNAi of S. rostrata CCaMK

Knockdown constructs (SrCCaMK-KO2 and SrCCaMK-KO3) were produced by recombining two regions of CCaMK in the pK7GWIWG2-D binary GATEWAY vector (Invitrogen) (Karimi et al., 2002). For the SrCCaMK-KO2 and SrCCaMK-KO3 constructs, the primers Dmi3KO2-Sense (5′-CAAAAAAGCAGGCTTCACACTACAAGGAAAAG-3′) and Dmi3KO2-Asense (5′-AGAAAGCTGGGTAAATTTGGAAGAATTTG-3′); and Dmi3KO3-Sense (5′-CAAAAAAGCAGGCTTGGATGCAAATAGTGATG-3′) and Dmi3KO3-Asense (5′-AGAAAGCTGGGTCAGAAGTTAGATGGCACAG -3′) were used, respectively. To obtain transgenic roots, S. rostrata embryonic axes were transformed as described, and composite plants carrying transgenic roots were selected by GFP (Van de Velde et al., 2003). The empty vector pPZP200-egfp was used as control. The knockdown level was determined from transgenic roots cultured in vitro on a plate by qRT-PCR as described above.

Dmi3-1 Complementation

For complementation of the M. truncatula dmi3-1 mutant, the S. rostrata CCaMK promoter and open reading frame were recombined with Multisite Gateway recombination into the vector pKm43GW-rolD (Invitrogen). The generation of transgenic roots on M. truncatula dmi3-1 seedlings and infection with S. meliloti was performed according to the previously described procedure (Boisson-Dernier et al., 2001).

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers EU622875 (S. rostrata CCaMK, complete coding sequence) and EU622876 (S. rostrata CCaMK, promoter region and 5′ untranslated region).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Mechanisms of Ca2+ Spiking in S. rostrata LRB-Associated Root Hair Cells.

Supplemental Figure 2. CCaMK Sequence Alignment and Functional Complementation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Grant Calder, Hiroki Miwa, and Allan Downie for useful discussions, Saul Hazledine and James Brown for statistical analyses, Patrick Smit and Sharon Long for providing the dsRED plasmid and M. truncatula NFs, respectively, and Martine De Cock for help in preparing the manuscript. This work was supported by the European Union Grain Legume Integrated Project (Food-CT-2004-506223). G.O. is funded by a David Philips Fellowship and a grant-in-aid of the Biotechnology and Biological Science Research Council, a Wolfson Research Merit award of the Royal Society, and the European Molecular Biology Organization Young Investigator Program. W.C. is grateful to the Institute for the Promotion of Innovation by Science and Technology in Flanders for a predoctoral fellowship and the European Molecular Biology Organization for both short- and long-term fellowships, respectively. J.D.H. was a Research Fellow of the Research Foundation-Flanders.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: marcelle.holsters@psb.vib-ugent.be.

Some figures in this article are displayed in color online but in black and white in the print edition.

Online version contains Web-only data.

References

- Allen, G.J., Chu, S.P., Harrington, C.L., Schumacher, K., Hoffmann, T., Tang, Y.Y., Grill, E., and Schroeder, J.I. (2001). A defined range of guard cell calcium oscillation parameters encodes stomatal movements. Nature 411 1053–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ané, J.-M., et al. (2004). Medicago truncatula DMI1 required for bacterial and fungal symbioses in legumes. Science 303 1364–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrighi, J.-F., et al. (2006). The Medicago truncatula lysine motif-receptor-like kinase gene family includes NFP and new nodule-expressed genes. Plant Physiol. 142 265–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Amor, B., Shaw, S.L., Oldroyd, G.E.D., Maillet, F., Penmetsa, R.V., Cook, D., Long, S.R., Dénarié, J., and Gough, C. (2003). The NFP locus of Medicago truncatula controls an early step of Nod factor signal transduction upstream of a rapid calcium flux and root hair deformation. Plant J. 34 495–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersoult, A., Camut, S., Perhald, A., Kereszt, A., Kiss, G.B., and Cullimore, J.V. (2005). Expression of the Medicago truncatula DMI2 gene suggests roles of the symbiotic nodulation receptor kinase in nodules and during early nodule development. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 18 869–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisson-Dernier, A., Chabaud, M., Garcia, F., Bécard, G., Rosenberg, C., and Barker, D.G. (2001). Agrobacterium rhizogenes-transformed roots of Medicago truncatula for the study of nitrogen-fixing and endomycorrhizal symbiotic associations. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 14 695–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockwell, P.J., and Davis, R.A. (2002). Introduction to Time Series and Forecasting, Springer Text in Statistics, 2nd ed. (Berlin: Springer).

- Capoen, W., Den Herder, J., Rombauts, S., De Gussem, J., De Keyser, A., Holsters, M., and Goormachtig, S. (2007). Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals common and specific tags for root hair and crack-entry invasion in Sesbania rostrata. Plant Physiol. 144 1878–1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capoen, W., Goormachtig, S., De Rycke, R., Schroeyers, K., and Holsters, M. (2005). SrSymRK, a plant receptor essential for symbiosome formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102 10369–10374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catoira, R., Galera, C., de Billy, F., Penmetsa, R.V., Journet, E.-P., Maillet, F., Rosenberg, C., Cook, D., Gough, C., and Dénarié, J. (2000). Four genes of Medicago truncatula controlling components of a Nod factor transduction pathway. Plant Cell 12 1647–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Haeze, W., De Rycke, R., Mathis, R., Goormachtig, S., Pagnotta, S., Verplancke, C., Capoen, W., and Holsters, M. (2003). Reactive oxygen species and ethylene play a positive role in lateral root base nodulation of a semiaquatic legume. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100 11789–11794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Haeze, W., Gao, M., De Rycke, R., Van Montagu, M., Engler, G., and Holsters, M. (1998). Roles for azorhizobial Nod factors and surface polysaccharides in intercellular invasion and nodule penetration, respectively. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 11 999–1008. [Google Scholar]

- D'Haeze, W., Gao, M., and Holsters, M. (2004). A gfp reporter plasmid to visualize Azorhizobium caulinodans during nodulation of Sesbania rostrata. Plasmid 51 185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Haeze, W., and Holsters, M. (2002). Nod factor structures, responses, and perception during initiation of nodule development. Glycobiology 12 79R–105R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Koninck, P., and Schulman, H. (1998). Sensitivity of CaM kinase II to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Science 279 227–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hartog, M., Musgrave, A., and Munnik, T. (2001). Nod factor-induced phosphatidic acid and diacylglycerol pyrophosphate formation: A role for phospholipase C and D in root hair deformation. Plant J. 25 55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hartog, M., Verhoef, N., and Munnik, T. (2003). Nod Factor and elicitors activate different phospholipid signaling pathways in suspension-cultured alfalfa cells. Plant Physiol. 132 311–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Den Herder, J., Vanhee, C., De Rycke, R., Corich, V., Holsters, M., and Goormachtig, S. (2007). Nod factor perception during infection thread growth fine-tunes nodulation. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20 129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch, R.E., Lewis, R.S., Goodnow, C.C., and Healy, J.I. (1997). Differential activation of transcription factors induced by Ca2+ response amplitude and duration. Nature 386 855–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt, D.W., Atkinson, E.M., and Long, S.R. (1992). Depolarization of alfalfa root hair membrane potential by Rhizobium meliloti Nod factors. Science 256 998–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt, D.W., Wais, R., and Long, S.R. (1996). Calcium spiking in plant root hairs responding to Rhizobium nodulation signals. Cell 85 673–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endre, G., Kereszt, A., Kevei, Z., Mihacea, S., Kaló, P., and Kiss, G.B. (2002). A receptor kinase gene regulating symbiotic nodule development. Nature 417 962–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engstrom, E.M., Ehrhardt, D.W., Mitra, R.M., and Long, S.R. (2002). Pharmacological analysis of Nod factor-induced calcium spiking in Medicago truncatula. Evidence for the requirement of type IIA calcium pumps and phosphoinositide signaling. Plant Physiol. 128 1390–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-López, M., Goormachtig, S., Gao, M., D'Haeze, W., Van Montagu, M., and Holsters, M. (1998). Ethylene-mediated phenotypic plasticity in root nodule development on Sesbania rostrata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 12724–12728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frugier, F., Kosuta, S., Murray, J.D., Crespi, M., and Szczyglowski, K. (2008). Cytokinin: Secret agent of symbiosis. Trends Plant Sci. 13 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason, C., Chaudhuri, S., Yang, T., Muñoz, A., Poovaiah, B.W., and Oldroyd, G.E.D. (2006). Nodulation independent of rhizobia induced by a calcium-activated kinase lacking autoinhibition. Nature 441 1149–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfroy, O., Debellé, F., Timmers, T., and Rosenberg, C. (2006). A rice calcium- and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase restores nodulation to a legume mutant. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19 495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Rizzo, S., Crespi, M., and Frugier, F. (2006). The Medicago truncatula CRE1 cytokinin receptor regulates lateral root development and early symbiotic interaction with Sinorhizobium meliloti. Plant Cell 18 2680–2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goormachtig, S., Alves-Ferreira, M., Van Montagu, M., Engler, G., and Holsters, M. (1997). Expression of cell cycle genes during Sesbania rostrata stem nodule development. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 10 316–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goormachtig, S., Capoen, W., and Holsters, M. (2004. a). Rhizobium infection: Lessons from the versatile nodulation behaviour of water-tolerant legumes. Trends Plant Sci. 9 518–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goormachtig, S., Capoen, W., James, E.K., and Holsters, M. (2004. b). Switch from intracellular to intercellular invasion during water stress-tolerant legume nodulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 6303–6308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X., and Spitzer, N.C. (1995). Distinct aspects of neuronal differentiation encoded by frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ transients. Nature 375 784–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckmann, A.B., Lombardo, F., Miwa, H., Perry, J.A., Bunnewell, S., Parniske, M., Wang, T.L., and Downie, J.A. (2006). Lotus japonicus nodulation requires two GRAS domain regulators, one of which is functionally conserved in a non-legume. Plant Physiol. 142 1739–1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans, J., Mortier, G., De Paepe, A., Speleman, F., and Vandesompele, J. (2007). qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative PCR data. Genome Biol. 8 R19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdaway-Clarke, T.L., Feijó, J.A., Hackett, G.R., Kunkel, J.G., and Hepler, P.K. (1997). Pollen tube growth and the intracellular cytosolic calcium gradient oscillate in phase while extracellular calcium influx is delayed. Plant Cell 9 1999–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi-Anraku, H., et al. (2005). Plastid proteins crucial for symbiotic fungal and bacterial entry into plant roots. Nature 433 527–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, K.M., Kobayashi, H., Davies, B.W., Taga, M.E., and Walker, G.C. (2007). How rhizobial symbionts invade plants: The Sinorhizobium–Medicago model. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5 619–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaló, P., et al. (2005). Nodulation signaling in legumes requires NSP2, a member of the GRAS family of transcriptional regulators. Science 308 1786–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori, N., et al. (2006). A nucleoporin is required for induction of Ca2+ spiking in legume nodule development and essential for rhizobial and fungal symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 359–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, M., Inzé, D., and Depicker, A. (2002). GATEWAY™ vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant Sci. 7 193–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévy, J., et al. (2004). A putative Ca2+ and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase required for bacterial and fungal symbioses. Science 303 1361–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.-h., Llopis, J., Whitney, M., Zlokarnik, G., and Tsien, R.Y. (1998). Cell-permeant caged InsP3 ester shows that Ca2+ spike frequency can optimize gene expression. Nature 392 936–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievens, S., Goormachtig, S., Den Herder, J., Capoen, W., Mathis, R., Hedden, P., and Holsters, M. (2005). Gibberellins are involved in nodulation of Sesbania rostrata. Plant Physiol. 139 1366–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limpens, E., Franken, C., Smit, P., Willemse, J., Bisseling, T., and Geurts, R. (2003). LysM domain receptor kinases regulating rhizobial Nod factor-induced infection. Science 302 630–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limpens, E., Mirabella, R., Fedorova, E., Franken, C., Franssen, H., Bisseling, T., and Geurts, R. (2005). Formation of organelle-like N2-fixing symbiosomes in legume root nodules is controlled by DMI2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102 10375–10380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, E.B., Madsen, L.H., Radutoiu, S., Olbryt, M., Rakwalska, M., Szczyglowski, K., Sato, S., Kaneko, T., Tabata, S., Sandal, N., and Stougaard, J. (2003). A receptor kinase gene of the LysM type is involved in legume perception in rhizobial signals. Nature 425 637–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, J.F., Rakocevic, A., Mitra, R.M., Brocard, L., Sun, J., Eschstruth, A., Long, S.R., Schultze, M., Ratet, P., and Oldroyd, G.E.D. (2007). Medicago truncatula NIN is essential for rhizobial-independent nodule organogenesis induced by autoactive calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Plant Physiol. 144 324–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergaert, P., Van Montagu, M., Promé, J.-C., and Holsters, M. (1993). Three unusual modifications, a d-arabinosyl, an N-methyl, and a carbamoyl group, are present on the Nod factors of Azorhizobium caulinodans strain ORS571. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90 1551–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, P.H., et al. (2007). An ERF transcription factor in Medicago truncatula that is essential for Nod factor signal transduction. Plant Cell 19 1221–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, R.M., Gleason, C.A., Edwards, A., Hadfield, J., Downie, J.A., Oldroyd, G.E., and Long, S.R. (2004). A Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase required for symbiotic nodule development: Gene identification by transcript-based cloning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 4701–4705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa, H., Sun, J., Oldroyd, G.E.D., and Downie, J.A. (2006. a). Analysis of calcium spiking using a cameleon calcium sensor reveals that nodulation gene expression is regulated by calcium spike number and the developmental status of the cell. Plant J. 48 883–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa, H., Sun, J., Oldroyd, G.E.D., and Downie, J.A. (2006. b). Analysis of Nod-factor-induced calcium signaling in root hairs of symbiotically defective mutants of Lotus japonicus. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19 914–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J.D., Karas, B.J., Sato, S., Tabata, S., Amyot, L., and Szczyglowski, K. (2007). A cytokinin perception mutant colonized by Rhizobium in the absence of nodule organogenesis. Science 315 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd, G.E.D., and Downie, J.A. (2004). Calcium, kinases and nodulation signalling in legumes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5 566–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd, G.E.D., and Downie, J.A. (2006). Nuclear calcium changes at the core of symbiosis signalling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9 351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd, G.E.D., Engstrom, E.M., and Long, S.R. (2001. a). Ethylene inhibits the Nod factor signal transduction pathway of Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell 13 1835–1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd, G.E.D., Mitra, R.M., Wais, R.J., and Long, S.R. (2001. b). Evidence for structurally specific negative feedback in the Nod factor signal transduction pathway. Plant J. 28 191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier, J.-H., Smelcer, P., Pavicevic, Z., Basic, E., Idrizovic, A., Estes, A., and Malik, K.U. (2003). PKC-ζ mediates norepinephrine-induced phospholipase D activation and cell proliferation in VSMC. Hypertension 41 794–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil, S., Takezawa, D., and Poovaiah, B.W. (1995). Chimeric plant calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase gene with a neural visinin-like calcium-binding domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92 4897–4901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne, R.W., and Lane, P.W. (2005). GenStat® Release Reference Manual, Part 3: Procedure Library PL16. (Oxford, UK: VSN International).

- Pingret, J.-L., Journet, E.-P., and Barker, D.G. (1998). Rhizobium Nod factor signaling: Evidence for a G protein–mediated transduction mechanism. Plant Cell 10 659–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radutoiu, S., Madsen, L.H., Madsen, E.B., Felle, H.H., Umehara, Y., Grønlund, M., Sato, S., Nakamura, Y., Tabata, S., Sandal, N., and Stougaard, J. (2003). Plant recognition of symbiotic bacteria requires two LysM receptor-like kinases. Nature 425 585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radutoiu, S., Madsen, L.H., Madsen, E.B., Jurkiewicz, A., Fukai, E., Quistgaard, E.M.H., Albrektsen, A.S., James, E.K., Thirup, S., and Stougaard, J. (2007). LysM domains mediate lipochitin–oligosaccharide recognition and Nfr genes extends the symbiotic host range. EMBO J. 26 3923–3935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riely, B.K., Lougnon, G., Ané, J.-M., and Cook, D.R. (2007). The symbiotic ion channel homolog DMI1 is localized in the nuclear membrane of Medicago truncatula roots. Plant J. 49 208–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini, S., Beis, D., Wolkenfelt, H., Murfett, J., Guilfoyle, T., Malamy, J., Benfey, P., Leyser, O., Bechtold, N., Weisbeek, P., and Scheres, B. (1999). An auxin-dependent distal organizer of pattern and polarity in the Arabidopsis root. Cell 99 463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito, K., et al. (2007). NUCLEOPORIN85 is required for calcium spiking, fungal and bacterial symbioses, and seed production in Lotus japonicus. Plant Cell 19 610–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauser, L., Roussis, A., Stiller, J., and Stougaard, J. (1999). A plant regulator controlling development of symbiotic root nodules. Nature 402 191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit, P., Raedts, J., Portyanko, V., Debellé, F., Gough, C., Bisseling, T., and Geurts, R. (2005). NSP1 of the GRAS protein family is essential for rhizobial Nod factor-induced transcription. Science 308 1789–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke, S., Kistner, C., Yoshida, S., Mulder, L., Sato, S., Kaneko, T., Tabata, S., Sandal, N., Stougaard, J., Szczyglowski, K., and Parniske, M. (2002). A plant receptor-like kinase required for both bacterial and fungal symbiosis. Nature 417 959–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J., Cardoza, V., Mitchell, D.M., Bright, L., Oldroyd, G., and Harris, J.M. (2006). Crosstalk between jasmonic acid, ethylene and Nod factor signaling allows integration of diverse inputs for regulation of nodulation. Plant J. 46 961–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirichine, L., et al. (2006). Deregulation of a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase leads to spontaneous nodule development. Nature 441 1153–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirichine, L., Sandal, N., Madsen, L.H., Radutoiu, S., Albrektsen, A.S., Sato, S., Asamizu, E., Tabata, S., and Stougaard, J. (2007). A gain-of-function mutation in a cytokinin receptor triggers spontaneous root nodule organogenesis. Science 315 104–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Velde, W., Mergeay, J., Holsters, M., and Goormachtig, S. (2003). Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated transformation of Sesbania rostrata. Plant Sci. 165 1281–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Eede, G., Dreyfus, B., Goethals, K., Van Montagu, M., and Holsters, M. (1987). Identification and cloning of nodulation genes from the stem-nodulating bacterium ORS571. Mol. Gen. Genet. 206 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Wais, R.J., Galera, C., Oldroyd, G., Catoira, R., Penmetsa, R.V., Cook, D., Gough, C., Dénarié, J., and Long, S.R. (2000). Genetic analysis of calcium spiking responses in nodulation mutants of Medicago truncatula. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 13407–13412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S.A., Viprey, V., and Downie, J.A. (2000). Dissection of nodulation signaling using pea mutants defective for calcium spiking induced by Nod factors and chitin oligomers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 13413–13418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.