Abstract

A significant number of eukaryotic regulatory proteins are predicted to have disordered regions. Many of these proteins bind DNA, which may serve as a template for protein folding. Similar behavior is seen in the prokaryotic LacI/GalR family of proteins that couple hinge-helix folding with DNA binding. These hinge regions form short α-helices when bound to DNA, but appear to be disordered in other states. An intriguing question is whether and to what degree intrinsic helix propensity contributes to the function of these proteins. In addition to its interaction with operator DNA, the LacI hinge helix interacts with the hinge helix of the homodimer partner as well as to the surface of the inducer-binding domain. To explore the hierarchy of these interactions, we made a series of substitutions in the LacI hinge helix at position 52, the only site in the helix that does not interact with DNA and/or the inducer-binding domain. The substitutions at V52 have significant effects on operator binding affinity and specificity, and several substitutions also impair functional communication with the inducer-binding domain. Results suggest that helical propensity of amino acids in the hinge region alone does not dominate function; helix-helix packing interactions appear to also contribute. Further, the data demonstrate that variation in operator sequence can overcome side chain effects on hinge helix folding and/or hinge•hinge interactions. Thus, this system provides a direct example whereby an extrinsic interaction (DNA binding) guides internal events that influence folding and functionality.

Keywords: LacI, helical propensity, allostery, DNA binding

Protein folding has long been a fundamental issue in biological sciences. Beyond the general question of how a polypeptide sequence adopts a three-dimensional structure, coupled folding and binding have been identified as a key feature of partially unstructured proteins in multiple regulatory processes (e.g., transcription regulation, signal transduction, membrane transport and signaling (6-9)). Indeed, more and more intrinsically disordered proteins are found to fold upon binding to their target partners, ligands, or even small ions (10-13). In the case of transcription regulation, mutual cooperative folding of both protein and DNA has been observed (6, 11, 14, 15). In this paper, coupled folding is explored in greater detail for the hinge helix of the lactose repressor protein (LacI)1.

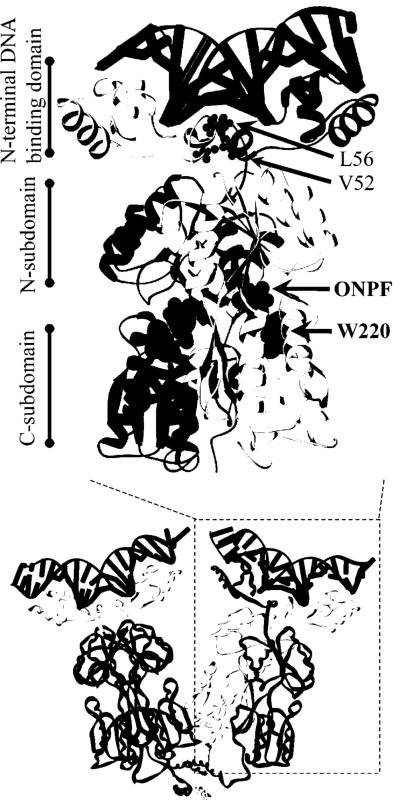

LacI is a premier model for the regulation of gene expression and allosteric transition in biological systems (2)2. This 150-kDa homotetramer is a dimer of functionally independent dimers, with one operator-binding site and two sugar-binding sites per dimer (Figure 1A). Each monomer consists of distinct domains: a helix-turn-helix (HTH) N-terminal DNA-binding domain; a hinge helix region; a core domain (including N- and C-subdomains), with the inducer-binding site sandwiched between the subdomains; and a C-terminal tetramerization domain (14-18). The hinge helix is the covalent connection between the two functional domains. This region (residues 50 −58) is folded in the presence of cognate operator DNA, but has no electron density in the X-ray structures of apo-LacI or LacI bound to IPTG (14). In NMR structures of the truncated protein alone or with nonspecific DNA the hinge is disordered, but folded in the presence of operator DNA (19-21). Thus, in addition to its importance in high-affinity DNA binding and inducer response, the hinge region may also be part of a switch between nonspecific and specific operator binding (14, 15, 19-22).

Figure 1.

(A). Structure of LacI dimer bound to DNA (top, black ladder) and anti-inducer, ONPF (middle, gray spacefilling). One monomer is in dark gray, the other light gray. The hinge helix side chains of L56, which intercalate into the minor groove of DNA (24), are shown as a gray ball/stick (top), and those of V52 are black ball/stick. W220 (middle, spacefill) is shown in black. The coordinates are from Protein Data Bank file 1efa (15). The protein is composed of the N-terminal DNA binding domain, the core domain (each monomer comprising N- and C-subdomains with an inducer-binding site between them), and the C-terminal tetramerization domain (not present in the dimeric structure shown). Below: The structure of tetrameric LacI bound to Osym DNA (shown as black ladder on the top of each dimer), with two monomers of right-hand dimer colored as black and light gray, respectively, and two monomers in the left-hand dimer colored to correspond with the structural domains described above. (B). Interactions between the hinge helix of a single monomer (“Hinge Helix A”) and other regions in the LacI•DNA complex. Columns of numbers represent residues of the protein; DNA basepairs of Osym are represented by columns of letters. Lines between any pair of numbers/letters indicate an interaction occurs between them. For clarity, the interactions of hinge helix A are separated onto three networks, which were made using the structure of 1efa (15) and the program RESMAP (25, 68). The interactions between 55 and 117/118 are “long” hydrogen bonds μ slightly above 3.5 Å but below 3.6 and 3.7 Å, respectively. The position of V52 and the central basepairs of Osym are indicated by asterisks. Note that position 52 is the only residue in the hinge helix that does not interact with DNA or the core inducer-binding domain.

Residues of the hinge helix participate both in high affinity operator-binding and in allosteric communication between the core inducer binding site and the DNA binding domain (14, 15, 21, 23, 24). This helix interacts with minor-groove bases through side chains of Asn50, Ala53, Gln54, Leu56, and Ala57 (Figure 1B) (25). Asn50 anchors the helix to the DNA backbone, and Leu56 intercalates between the central base-pair step (Figure 1A) (15, 17, 24). Insertion of the Leu56 side chains forces the operator to bend away from the minor groove by ∼45°. Besides its interactions with DNA, the two hinge helices of a dimer participate in protein•protein interactions (Figure 1B) (15, 17, 24). Contacts between Val52, Ala53, Gln 55, and Leu56 comprise a helix-helix interface with V52 being the point of closest approach (15, 17, 24). Asn50 and Asn51 contact the N-subdomain of the partner monomer, and Gln55 interacts with the core N-subdomain of the same monomer (Figure 1B). All of these interfaces are interrupted by the conformational change triggered by IPTG binding to the core domain (15, 17).

Both protein•DNA and hinge•hinge interactions appear important to the stability of the hinge helix. Thus, at least three elements are required for complex formation: helix formation, protein•protein contacts, and protein•DNA interactions. To begin parsing the various contributions to this complex, we focused on the side chain at position 52, which does not contact DNA or the inducer-binding domain (15, 17, 24, 25) (Figure 1B). Our expectation was that mutations at this site would allow assessment of the relative importance of helix propensity to coupled folding and binding. Thirteen substitutions were introduced at position 52, and their influence on LacI function was examined in the context of variant operator sequences. Surprisingly, functional effects do not always correlate with the helix propensities of the substituted amino acids: Hinge-helix•hinge-helix interactions and extrinsic protein•operator interactions appear to dominate. Moreover, several substitutions that impair allostery, presumably through impeding the requisite hinge region alterations, were identified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Unless otherwise specified, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO), except IPTG was from RPI (Troy, NY), urea from Fluka (Milwaukee, WI), and polynucleotide kinase from NEB (Beverly, MA).

Plasmids and Mutagenesis

Mutations in the lac repressor gene were generated in the pJC1 plasmid using site-specific mutagenesis (Quickchange, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) (26, 27). Oligonucleotides (TACATTCCCAACCGCXXXGCACAACAACTGG, where XXX was specific to each substitution) were used as primers to mutate the lacI gene from the wild-type version. PCR was executed using the temperature steps: 95 °C for 30s, 55 °C for 1 min, and 68 °C for 12 mins; this cycle was repeated 18 times. The PCR product was digested with Dpn1 to degrade template DNA and used to transform XL1-blue or DH5α cells to amplify the mutated plasmids. The entire lacI gene of each mutant produced was sequenced by Seqwright Inc. (Houston, TX).

Protein purification

Protein was expressed in BLIM bacterial cells (28). Growth was in 2xYT media overnight at 37°C with constant shaking. After centrifugation, the cell pellet was resuspended in breaking buffer (0.2 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 0.2 M KCl, 0.01 M Mg(OAc)2, 0.3 mM DTT, 5% glucose) with a small amount of lysozyme added, and frozen at −20°C (27, 29, 30). To initiate purification, cells were thawed on ice, and DNase was added to digest genomic DNA. PMSF (∼7 mg/100 ml) was added to inhibit protease activity. Following centrifugation, the crude supernatant was brought to 35% saturated ammonium sulfate. After centrifugation, the ammonium sulfate precipitate was resuspended, dialyzed against 0.09 M KP buffer (0.09 M potassium phosphate, 5% glucose, 0.3 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.5), and loaded on a phosphocellulose column (27, 29, 30). Protein was eluted from the phosphocellulose column by a gradient composed of equal volumes of 0.12 M KP buffer (0.12 M potassium phosphate, 5% glucose, 0.3 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.5) and 0.3 M KP buffer (0.3 M potassium phosphate, 5% glucose, 0.3 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.5). Purified protein was stored in elution buffer (∼0.18 M potassium phosphate, 5% glucose, 0.3 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.5). SDS-PAGE was employed to determine protein purity as >95%. The activity of purified protein, generally ≥ 90%, was determined by stoichiometric DNA binding assays (30-33).

Magnetic circular dichroism measurements

Magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) spectropolarimetery was used to determine the extinction coefficient of V52W due to an additional tryptophan residue in this mutant (34). From absorbance of the protein sample at 280 nm and the concentration of tryptophan in the protein calculated from MCD, the extinction coefficient of V52W was determined to be 1.3 (± 0.08) × 105 M−1cm−1, about 1.5-fold that for wild-type tetramer, which has two tryptophan residues per monomer.

DNA binding/operator release

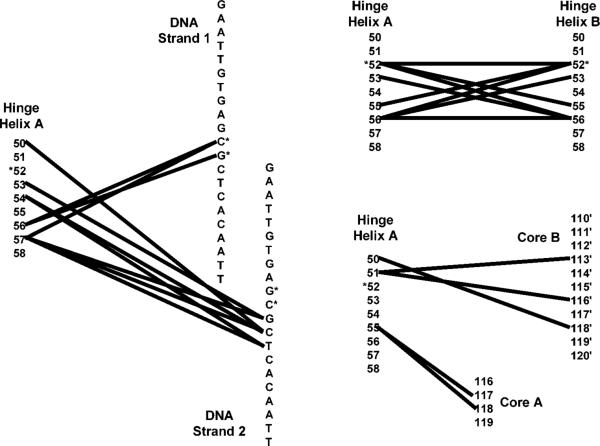

For DNA binding and operator release experiments, the nitrocellulose filter binding assay was employed (32, 33, 35). Multiple operator DNA sequences (O1, Osym, OdisB, and OdisC) were used in these experiments (Figure 2) (36, 37) (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA). After hybridization in polynucleotide kinase buffer (70 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, pH 7.6), the dsDNA was labeled with [32P]-ATP using polynucleotide kinase. A Nick column (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) was used to purify labeled DNA from free nucleotide. In affinity assays, operator concentration was generally set at least 10-fold below the Kd, whereas protein concentration was varied. A Fuji phosphorimager was then used to quantify the radioactively-labeled complex retained on the nitrocellulose filters (Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, NH). If present, inducer (IPTG) concentration was 1 mM.

Figure 2.

Sequence of the variant operators used for the DNA binding studies. The 40 base pair sequences are shown. The region of the O1 operator protected by LacI from DNase footprinting is highlighted in bold and outlined letters (83). Symmetric sites within each operator are underlined and are shown in the sequences in similar print to the O1 sequence. The two half-sites are labeled as proximal and distal based on the natural operator, O1.

The program Igor Pro (Wavemetrics, CA) was used to fit data for affinity assays using the equation:

| (1) |

where Yobs is the radioactivity retained at a specific protein concentration, Ymax is the measured radioactivity when all of the DNA is bound to repressor, Kd is the equilibrium dissociation constant, and c is the background radioactivity in the absence of protein. The value of the Hill coefficient, n, was either fixed at 1 or allowed to float, in which case the values are found to be ∼1.

In operator release experiments, constant concentrations of protein (at ∼80% saturation for operator binding in the absence of inducer, see figure legends) were incubated with ∼2 × 10−12 M operator to form LacI-DNA complex, then IPTG (varied from ∼10−8 to 10−4 M) was added to the reaction to release operator (30, 31, 38, 39). Again, the retained operator was quantified using a Fuji phosphorimager. The resulting data were fit with the program Igor Pro (Wavemetrics, CA) to the equation:

| (2) |

Equation 2 is derived from equation 1 to allow decreasing values for DNA binding as a function of inducer binding. Yobs is observed radioactivity at a specific IPTG concentration; Ymax is the maximum change in radioactivity between conditions of zero and saturating inducer; n is the Hill coefficient; [IPTG]mid is the concentration of IPTG where 50% operator is bound; and c is the background value.

IPTG binding

IPTG binding was quantified from the fluorescence emission intensity decrease above 340 nm that is coincident with IPTG binding (40-42). Protein concentration was set at 1.5 × 10−7 M monomer, with IPTG concentration varied. The experiments were performed in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.15 M KCl using an SLM-Aminco AB2 spectrofluorometer with an excitation wavelength of 285 mn. The emission spectra from 300 to 380 nm were recorded. For IPTG binding in the presence of operator DNA, protein concentration was 5 × 10−7 M monomer, and operator concentration was 1 × 10−6 M. Values for total fluorescence between 340 and 380 nm were fit to equation 2 with [IPTG]mid substituted by the equilibrium dissociation constant Kd, and Y and c values representing fluorescence intensities.

RESULTS

Generation of V52 Mutants and Protein Purification

Based on genetic analysis (43, 44) and the properties of amino acids, thirteen substitutions — V52A, V52D, V52E, V52F, V52G, V52H, V52L, V52P, V52Q, V52R, V52S, V52T, and V52W — were generated to explore the role of the side chain at position 52 in hinge helix function. Functional effects of V52C were previously reported by Falcon and Matthews (29, 37). The entire gene of each LacI variant was sequenced fully to confirm that no other mutation was present. Mutant repressors were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified by phosphocellulose column chromatography. All mutant proteins purified in a manner similar to tetrameric wild-type protein. The purification process is sensitive to oligomerization state (27, 45-47), and not surprisingly gel filtration confirmed that all mutant proteins exhibit the molecular weight anticipated for tetramer, ∼150 kDa (data not shown).

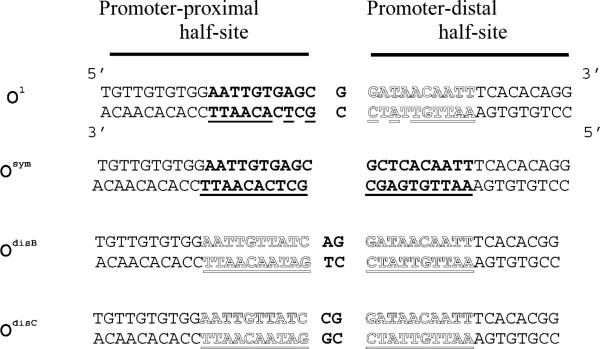

Operator O1 binding of V52 mutants

Operator O1 binding affinity of individual V52 mutant proteins was determined using nitrocellulose filter binding (Figure 3 and Table 1) (32, 35). Wide-ranging differences were found for the V52 variant proteins. Notably, V52G binds O1 operator ∼6-fold weaker, and V52P has O1 operator-binding affinity only ∼2-fold lower than wild type, effects that are less than anticipated for helix-breaking residues. In contrast, both positively and negatively charged residues have profound effects on O1 operator binding. Although glutamate has been suggested to form a ring via a special structure with its Cγ carbon (48), abolition of O1 DNA binding was also observed for V52D. Similarly, O1 operator binding affinity is decreased ∼25-fold in V52R. Neutralization of negative charge at the Cγ carbon of glutamate by the amide group in glutamine largely restores O1 operator-binding affinity. The observed operator binding behavior is very consistent with the phenotype previously for each of these substitutions (Table 1) (43). Since no or very weak operator binding was observed for V52D, V52E, and V52R, few additional experiments were possible for these three mutants.

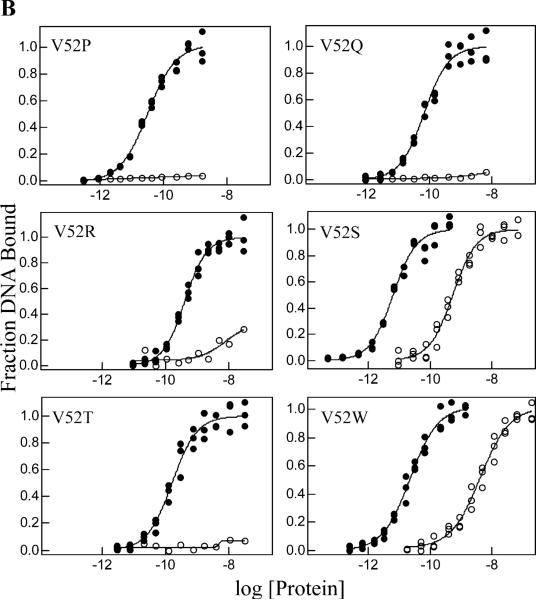

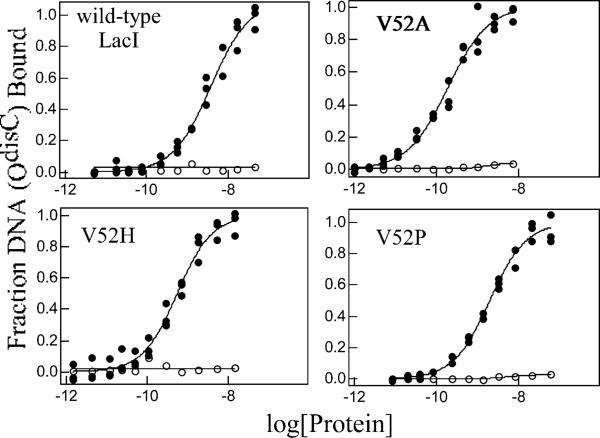

Figure 3.

Operator O1 binding and inducibility of wild-type LacI and V52 mutants. Experiments were performed in buffer containing 0.01 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.15 M KCl, 0.3 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5% DMSO in the absence (closed circles) or presence (open circles) of IPTG. The experiments were conducted as described in Materials and Methods with operator concentration below 1.5 × 10−13 M for V52A and V52H and below 1.5 × 10−12 M for other proteins. IPTG concentration was 1 mM. Data shown are for single determinations (triplicate points), and the results from multiple determinations are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. (A) Wild-type LacI, V52A, V52F, V52G, V52H, and V52L; (B) V52P, V52Q, V52R, V52S, V52T, and V52W. Note that V52A, V52H, V52S, and V52W retain significant affinity in the presence of inducer.

Table 1.

Operator O1-binding properties of V52 variantsa

| Kd (M × 1011)b | mutant/WT | Side Chain Effect | Phenotypec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTLacI | 1.5 ± 0.4 | + | ||

| V52A | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.15 | Smaller | +s |

| V52C-redd | 0.34 ± 0.12 | 0.23 ± 0.08 | Smaller/Polar | +s |

| V52D | >1000 | >1000 | Charged | NDe |

| V52E | NBDf | >1000 | Charged | −+ |

| V52F | 4.1 ± 2 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | Bulkier | + |

| V52G | 9.0 ± 2.0 | 6.0 ± 1.6 | Helix Breaking | +− |

| V52H | 0.30 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.09 | Charged | +s |

| V52L | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | Bulkier | +ws |

| V52P | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | Helix Breaking | + |

| V52Q | 7.0 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 1.2 | Polar | + |

| V52R | 37 ± 7 | 25 ± 6.6 | Charged | −+ |

| V52S | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | Polar | +ws |

| V52T | 18 ± 8 | 12 ± 3.2 | Polar | NDe |

| V52W | 2.1 ± 1 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | Bulkier | NDe |

Values shown represent a minimum of 3 measurements and up to 6 measurements.

Operator binding experiments were performed in buffer containing 0.01 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.15 M KCl, 0.3 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5% DMSO. Operator O1 DNA concentration was below 1.5 × 10−13 M for V52A and V52H proteins and below 1.5 × 10−12 M for other proteins.

Data from Suckow et al. (43): +, repression > 200-fold; +−, repression 200- to 20- fold; −+, repression 20- to 4-fold; and -, repression < 4-fold; s, Is phenotype (insensitive to inducer); ws, weak Is phenotype.

Reduced V52C: data are from Falcon and Matthews (37).

ND: not determined.

NBD: no binding detected.

Inducibility of V52 mutants

Besides its important role in high affinity operator binding, the hinge region is crucial for allostery in LacI. For wild-type LacI, O1 binding is diminished >4 orders of magnitude in the presence of inducer (30). However, four mutants (V52A, V52H, V52S, and V52W) retain high affinity for operator O1 DNA in the presence of saturating inducer (Figure 3 and Table 2), consistent with the is phenotype observed for V52A, V52H, and V52S (Table 1) (43). To further examine the effects of substitutions on the allosteric transition of this protein, operator release experiments were conducted. Nitrocellulose filter binding was used to monitor decreased levels of bound DNA as a function of inducer concentration (30, 31, 38, 39). Results are presented in Table 3 and Figure 4. Operator is released at higher IPTG concentration for V52H and V52S, and perhaps for V52W. The remaining mutants release operator at an inducer concentration near that for wild-type LacI.

Table 2.

|

O1 |

Osym |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd (M × 10−11) | + IPTGc (M × 10−11) | Kd (M × 10−11)d | + IPTGe (M × 10−11) | |||

| WTLacI | 1.5 ± 0.4 | >10000 | >1000 | 0.18 ± 0.06 | >10000 | >1000 |

| V52A | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 6.2 ± 3.5 | 31 ± 4.7 | 0.22 ± 0.12 | 0.5 ± 0.09 | 2.3 ± 1.3 |

| V52C-redf | 0.34 ± 0.02 | >10000 | >1000 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 47 ± 10 | 1100 ± 305 |

| V52F | 4.1 ± 2 | >10000 | >1000 | 0.32 ± 0.03 | 32 ± 2 | 100 ± 9.4 |

| V52G | 9.0 ± 2.0 | >10000 | >1000 | 1.0 ± 0.25 | >10000 | >1000 |

| V52H | 0.30 ± 0.2 | 18 ± 5 | 60 ± 40 | 0.17 ± 0.06 | 1.8 ± 0.90 | 10.6 ± 3.8 |

| V52L | 2.9 ± 0.2 | >10000 | >1000 | 0.34 ± 0.06 | 33 ± 7 | 97 ± 17 |

| V52P | 3.2 ± 0.7 | >10000 | >1000 | 1.1 ± 0.13 | >10000 | >1000 |

| V52Q | 7.0 ± 0.2 | >10000 | >1000 | 0.66 ± 0.12 | >10000 | >1000 |

| V52S | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 76 ± 8 | 84 ± 18.8 | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 3.2 ± 0.90 | 17 ± 2.7 |

| V52T | 18 ± 8 | >10000 | >1000 | 2.9 ± 1.2 | >10000 | >1000 |

| V52W | 2.1 ± 1 | 400 ± 140 | 190 ± 91 | 0.23 ± 0.06 | 22 ± 8 | 96 ± 25 |

Standard deviations shown represent a minimum of 3 measurements and up to 6 measurements. Notice that three mutants (V52A, V52H, and V52P) bind Osym comparably to O1.

Operator binding experiments were performed in buffer containing 0.01 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.15 M KCl, 0.3 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5% DMSO.

For O1 binding in the presence of IPTG, operator concentration was below 1.5 × 10−12 M.

Operator Osym concentration was below 1.5 × 10−13 M.

Operator Osym concentration was below 1.5 × 10−13 M for V52A protein and below 1.5 × 10−12 M for other proteins.

From Falcon and Mathews (37).

Table 3.

Inducer-binding properties of V52 mutantsa

| [IPTG]mid (M × 106) operator releaseb | KR/I (M×106)c | [IPTG]mid/ KR/I | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WTLacI | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.3 |

| V52A | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.6 |

| V52D | NDd | 1.3 ± 0.2 | |

| V52E | NDd | 1.1 ± 0.2 | |

| V52F | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.5 |

| V52G | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.3 |

e e

|

6.9 ± 2.0 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 5.3 ± 0.9 |

| V52L | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 1.0 |

| V52P | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.5 |

| V52Q | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.3 |

| V52R | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.5 |

| 4.5 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | |

| V52T | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.5 |

| 4.2 ± 0.7 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 1.0 |

Values shown represent a minimum of 3 measurements and up to 6 measurements.

Operator release experiments were performed in buffer containing 0.01 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.15 M KCl, 0.3 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5% DMSO. Protein concentration was as follows: wild-type, 2.4 × 10−10 M; V52A, 1 × 10−11 M; V52R, 5 × 10−9 M; V52Q, 5 × 10−10 M; V52G, 3.5 × 10−9 M; V52H, 2.1 × 10−11 M; V52L, 2.1 × 10−10 M; V52F, 2.4 × 10−10 M; V52P, 1.5 × 10−10 M; V52S, 2.4 × 10−10 M; V52T, 3.5 × 10−9 M; V52W, 2.4 × 10−10 M.

IPTG binding experiments were conducted in buffer containing 0.01 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.15 M KCl.

ND: not determined (insufficient DNA binding affinity).

Boxes highlight mutants with differential behavior.

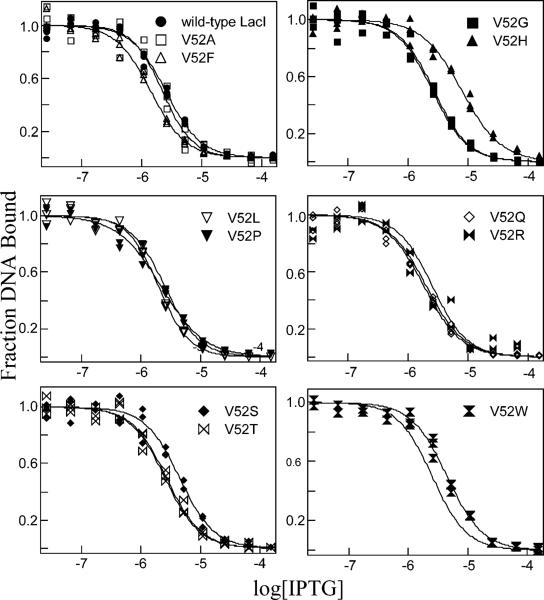

Figure 4.

Operator release by IPTG of wild-type protein and V52 variants. The buffer was 0.01 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.15 M KCl, 0.3 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 5% DMSO, and various concentrations of IPTG were added. In the experiments shown, operator concentration was 1.5 × 10−12 M, and protein concentrations were as follows: wild-type, 2.4 × 10−10 M; V52A, 1 × 10−11 M; V52F, 2.4 × 10−10 M; V52R, 5 × 10−9 M; V52G, 3.5 × 10−9 M; V52H, 2.1 × 10−11 M; V52L, 2.1 × 10−10 M; V52P, 1.5 × 10−10 M; V52Q, 5 × 10−10 M; V52S, 2.4 × 10−10 M; V52T, 3.5 × 10−9 M; V52W, 2.4 × 10−10 M. Data for a single experiment are shown (triplicate points), and the results from multiple measurements are summarized in Table 3. Dotted lines correspond to the wild-type data and are provided for comparison.

IPTG binding of V52 mutants

The operator release experiment involves inducer binding as well as the conformational change that diminishes operator affinity (31, 49, 50). Therefore, the change of [IPTG]mid could derive from either changed inducer binding or altered allosteric transition. To distinguish these two processes for V52 mutants, IPTG binding affinity was measured for V52 mutants by monitoring changes in tryptophan fluorescence as a function of IPTG concentration (40). The major fluorophore monitored for IPTG binding is W220, which exhibits a shift of the spectrum to lower wavelength upon LacI binding to inducer (40-42), a situation presented even in V52W. All LacI variants exhibit IPTG binding affinity comparable to wild-type protein (Table 3), consistent with the anticipation that the conformation of inducer binding pocket is unchanged in these V52 mutants (14-16).

One way to monitor the allosteric transition is the ratio between [IPTG]mid for the release experiment and the Kd for IPTG binding affinity. In wild-type repressor and many other variants, this value is ∼2 (30, 49). The ratio decreases slightly in V52A, V52F, V52Q, and V52R, whereas this value is increased in V52H, V52S, and V52W. The remaining mutants have allosteric ratios comparable to wild type. These results indicate that the allosteric transition may be partially impeded in V52H, V52S, and V52W.

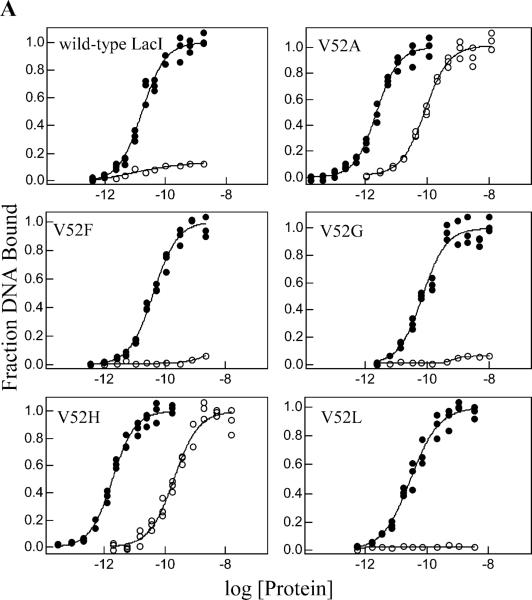

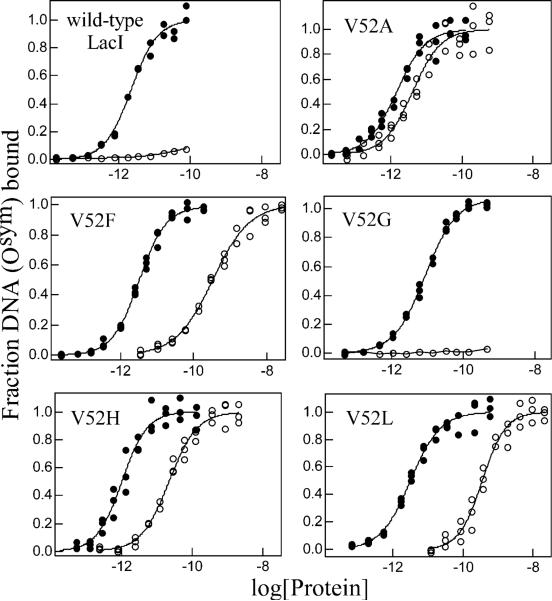

Osym binding of V52 mutants

Previous studies show that varying operator sequence can affect several aspects of LacI DNA binding function (51-53). Falcon and Matthews combined varied operator sequences with mutations in the hinge helix (V52C-oxidized, Q60G, and a series of glycine insertion mutants) and found differential effects on affinity and allostery (29, 36, 37, 39). Thus, to explore effects on substitutions at V52, three additional operator sequences (Osym, OdisB, and OdisC) with different half-site sequences and central spacing were used (Figure 2).

Osym contains a symmetric sequence that is derived from the promoter proximal half-site and has no central base pair (Figure 2) (54). This “optimized” operator binds wild-type LacI with ∼8-fold higher affinity than O1. As shown in Figure 5 and Table 2, most V52 variants bind Osym with increased affinities compared to O1 and with similar magnitude to wild-type LacI. However, V52A and V52H, which have enhanced O1 binding, do not show enhanced binding with Osym. V52P binds to Osym with affinity comparable to wild-type LacI binding to O1, effectively decreasing Osym binding affinity ∼6-fold relative to wild-type protein (Table 2). The effects of glycine substitution are similar for both operator sequences.

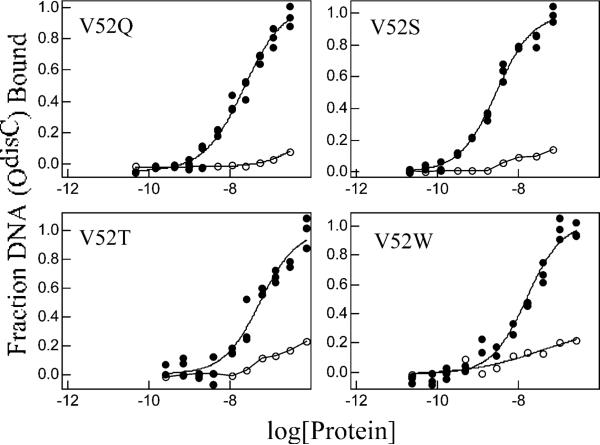

Figure 5.

Osym binding and inducibility of wild-type LacI and V52 mutants. Buffer was 0.01 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.15 M KCl, 0.3 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5% DMSO in the absence (closed circles) or presence (open circles) of IPTG. The experiments were conducted as described in Materials and Methods with Osym concentration below 1.5 × 10−13 M in the absence of inducer. In the presence of 1 mM IPTG, operator concentration was below 1.5 × 10−13 M for V52A and below 1.5 × 10−12 M for other proteins. Data are shown for single determinations (triplicate points), and the results from multiple determinations are summarized in Table 2. (A) Wild-type LacI, V52A, V52F, V52G, V52H, and V52L; (B) V52P, V52Q, V52S, V52T, and V52W. Note that V52A, V52F, V52H, V52L, V52S, and V52W show high affinity Osym binding in the presence of a saturating inducer.

Like O1, Osym binding is dramatically diminished when wild-type LacI binds inducer. However, in addition to the four mutants (V52A, V52H, V52S, and V52W) that exhibit decreased response to inducer binding for O1, two more mutants — V52L and V52F — retain high affinity for Osym binding in the presence of IPTG (Figure 5 and Table 2). In addition, V52A, V52F, V52H, V52L, and V52S have a significantly lower “allosteric ratio” (binding in the presence /absence of IPTG) for Osym than O1 (see Table 2). Interestingly, V52A decreases this ratio to only ∼2-fold, reminiscent the operator binding properties of oxidized disulfide-linked V52C (29, 37), and suggesting nearly total loss of allosteric communication between the operator and inducer binding site.

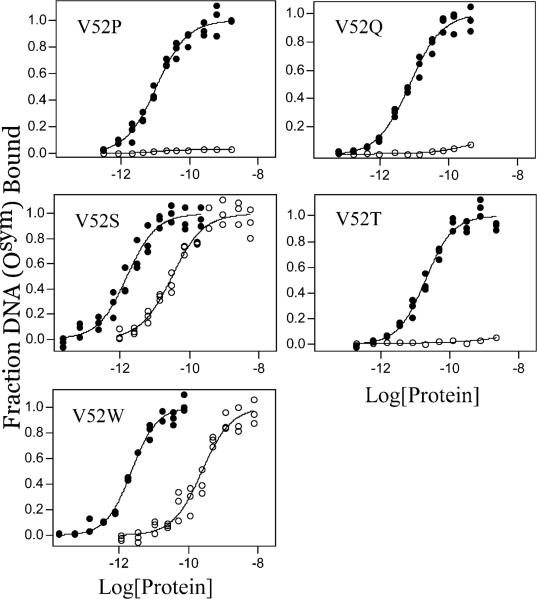

OdisB and OdisC binding of V52 mutants

Previous work indicated that wild-type LacI can bind with high affinity to an operator with distal-site symmetry but with increased spacing between the half sites (37, 55, 56). Thus, OdisB, a symmetric promoter distal-site sequence with A-G in the center, and OdisC, a symmetric promoter distal-site sequence with C-G in the center (Figure 2), were employed to further examine the effects of operator sequence variation on functions of V52 mutants. Among the ten proteins examined, only V52Q and V52S exhibited measurable binding for OdisB (Table 4), and this binding remained inducer-sensitive. In contrast, when wild-type and V52 variant proteins were assayed with the OdisC operator, high affinity operator binding was observed for multiple variants (Figure 6 and Table 4). Interestingly, V52P exhibited enhanced OdisC binding compared to wild-type LacI, and even the weak binder of O1 and Osym, V52T, bound OdisC with detectable affinity. With OdisC, all variants that clearly bind are fully inducible (Figure 7 and Table 4), though V52C-red has been shown to be compromised (perhaps due to a residual amount of disulfide formation (36)). The generally higher affinity for OdisC compared to OdisB for V52 LacI variants may result from enhanced flexibility of central C-G step and its ability to adopt greater positive rolls in OdisC (36, 57, 58)

Table 4.

|

OdisB (M × 10−10) |

OdisC (M × 10−10) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd | + IPTG | Kd | + IPTG | |

| WTLacI | >1000 | >1000 | 38 ± 8 | >1000 |

| V52A | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | |

| V52C-redc | >1000 | >1000 | ||

| V52F | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 |

| V52G | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 |

| V52H | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | |

| V52L | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 |

| V52P | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | |

| V52Q | >1000 | 280 ± 65 | >1000 | |

| V52S | >1000 | >1000 | ||

| V52T | >1000 | >1000 | 500 ± 40 | >1000 |

| V52W | >1000 | >1000 | 210 ± 40 | >1000 |

Standard deviations shown represent a minimum of 3 measurements and up to 4 measurements.

Operator binding experiments were performed in buffer containing 0.01 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.15 M KCl, 0.3 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5% DMSO. Operator (OdisC or OdisB) concentration was below 1.5 × 10−12 M.

From Falcon and Mathews (37).

dBoxes highlight mutants with differential behavior.

Figure 6.

OdisC binding and inducibility of wild-type LacI and V52 mutants. Buffer was 0.01 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.15 M KCl, 0.3 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5% DMSO in the absence (closed circles) or presence (open circles) of IPTG. OdisC concentration was below 1.5 × 10−12 M. When present, IPTG concentration was 1 mM. Data are shown for single determinations (triplicate points), and the results from multiple determinations are summarized in Table 4. (A) Wild-type LacI, V52A, V52H, and V52P; (B) V52Q, V52S, V52T, and V52W.

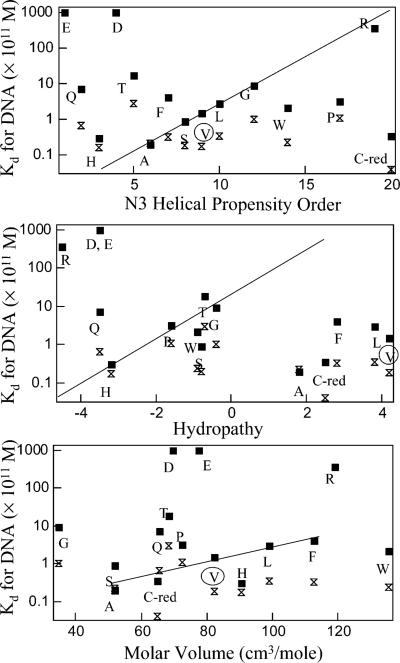

Figure 7.

Correlation between DNA binding affinities (O1-squares and Osym-bowties) of V52 mutants and N3 helical propensity order (top) (69-73), hydropathy (middle) (75), and molar volume (bottom) (74). For helical propensity versus Kd, a trend is noted with a line but has many obvious outliers. No trend is seen for hydropathy versus Kd, but data suggest a correlation between affinity and molar volume for about one-half of the substitutions. We predict that this may reflect enhanced hinge•hinge packing interactions.

DISCUSSION

The LacI•operator complex has two features now known to be common in protein•DNA interactions: protein folding coupled with DNA binding, and altered (non B-form) DNA structure. Both of these elements have been observed in a number of other systems, suggesting that they may be important characteristics of genetic regulation (e.g., (11, 36, 37, 59-65)). In LacI and its homologues, the hinge helix is responsible for both of these features.

The hinge region is the only covalent connection between the effector binding core domain and N-terminal DNA binding domain. For LacI and PurR, the hinge folds into a helix only upon cognate operator binding, whereas this region remains unstructured in other states, apparently even when bound to nonspecific DNA (14, 15, 19-21, 23, 24, 66, 67). The hinge helix participates in multiple interfaces (Figure 1B) — between the partner hinge helices within the dimer, between the hinge helix and the top surfaces of the core N-subdomains, and between the minor groove of DNA and side chains in the hinge helix (25, 68). Alterations in each of these interactions may affect hinge function (14, 15, 19, 21). In the hinge region, residues 50 and 51 contact DNA and the N-subdomain; residues at 53, 56, and 57 are highly conserved among the LacI/GalR family and are required for DNA binding and specificity; residues 53 and 56 are also involved in hinge•hinge contacts; residue 54 contacts DNA; and residue 55 contacts the core N-subdomain (Figure 1B). Residue 52 is involved in the hinge•hinge interface, but does not interact with DNA or the inducer-binding domain (Figure 1B). Substitution at this site provides opportunity to parse helix-folding contributions from other factors.

To that end, the correlation between helical propensity of the hinge region and LacI function was examined. V52 occupies the third position of the hinge helix (N3). Residue and position-specific helical propensities are available for this position and are plotted versus Kd for O1 and Osym (Figure 7) (69-73). Higher propensity order numbers indicate decreased likelihood to form an α-helix. As shown by the line in Figure 7, a weak correlation is suggested for a few substitutions, but D, E, T, Q, P, W, and C-reduced do not follow this correlation. Thus, helical propensity at this position of the hinge region may contribute to, but does not dominate, LacI function in terms of high affinity operator binding.

For several substitutions, we can rationalize alternative interactions that appear to counter high helical propensity. V52D and V52E substitutions should not diminish helix formation substantially, but DNA binding is abolished. We surmise that the negative charge so close to the phosphate backbone and within the hinge•hinge interface negatively influences interactions requisite for function. Interestingly, V52R also results in substantial loss in operator affinity, presumably due to charge repulsion in the required hinge•hinge interface but perhaps also to lower helix propensity.

Correlation between operator-binding affinity and other properties (e.g., hydropathy and molar volume) of amino acids was also examined. Charged and polar amino acids have lower hydropathy, whereas molar volume is related to the size of amino acids and might reflect trends of steric hindrance (74, 75). As shown in Figure 7, the relationship between O1/Osym operator binding affinities and these properties (hydropathy and molar volume) shows that the only consistent observation is that the charged residues are extreme outliers. About one-half of the substitutions may show correlation between binding affinity and molar volume, suggesting contributions from change helix•helix packing. For the other half of the variants, other factors must determine DNA binding affinity of LacI variants at position 52.

When the variants are grouped by their overall functional properties, patterns do emerge that can be correlated with probable structural effects (Table 5). The first group of substitutions (A, H, S, and C-red) generally exhibit increased DNA binding affinity and decreased inducibility for DNA sequences examined. These substitutions may enhance helix formation as well as contributing to the stability of the hinge•hinge interface. The histidine imidazole may ring stack, and the hydroxyl of serine may form hydrogen bonds in this apolar interface (76). Note that for histidine, we expect that the pKa would be lowered to avoid the presumed charge repulsion seen with arginine.

Table 5.

Overall binding effects and causesa

| Variant | DNA binding observations compared to wild-type LacI | Most likely effects of substitution | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | O1 | Osym | OdisC | ||

| Group 1: | A | ↑WT affinity | ∼WT affinity | ↑WT affinity | Enhanced helix propensity and enhanced hinge•hinge stability |

| ↓↓inducibility | ↓↓↓inducibility | ∼inducibility | |||

| H | ↑WT affinity | ∼WT affinity | ↑WT affinity | Enhanced helix propensity and enhanced hinge•hinge stability | |

| ↓↓inducibility | ↓↓inducibility | ∼inducibility | |||

| S | ↑WT affinity | ∼WT affinity | ∼WT affinity | Enhanced hinge•hinge interaction | |

| ↓inducibility | ↓↓inducibility | ∼inducibility | |||

| C-red | ↑WT affinity | ↑WT affinity | ↑↑WT affinity | Enhanced hinge•hinge interaction; may have some spontaneous disulfide bond formation | |

| ∼inducibility | ↓inducibility | ↓↓inducibility | |||

| Group 2 | F | ∼WT affinity | ∼WT affinity | No binding | Increased molecular volume, altered hinge•hinge interaction |

| ∼inducibility | ↓inducibility | ||||

| L | ∼WT affinity | ∼WT affinity | No binding | Increased molecular volume and hydropathy, decreased hinge stability, altered hinge•hinge interaction | |

| ∼inducibility | ↓inducibility | ||||

| W | ∼WT affinity | ∼WT affinity | ↓WT affinity | Increased molecular volume, altered hinge•hinge interaction | |

| ↓inducibility | ↓inducibility | ∼inducibility | |||

| Group 3 | G | ↓WT affinity | ↓WT affinity | No binding | Decreased helix stability |

| ∼inducibility | ∼inducibility | ||||

| P | ↓WT affinity | ↓WT affinity | ↑WT affinity | Decreased helix stability | |

| ∼inducibility | ∼inducibility | ∼inducibility | |||

| Group 4 | Q | ↓WT affinity | ↓WT affinity | No binding | Polarity affects hinge•hinge interaction |

| ∼inducibility | ∼inducibility | ||||

| T | ↓↓WT affinity | ↓↓WT affinity | ↓↓WT affinity | Polarity affects hinge•hinge interaction | |

| ∼inducibility | ∼inducibility | ∼inducibility | |||

| Group 5 | D, E | ↓↓↓↓WT affinity | Not Measured | Not measured | Abolished hinge folding and/or hinge•hinge interaction due to charge repulsion |

| R | ↓↓WT affinity | Not Measured | Not measured | Abolished hinge folding and/or hinge•hinge interaction due to charge repulsion | |

↑, increased over; ∼, comparable; ↓, diminished < 10-fold; ↓↓, 10−100-fold decreased; ↓↓↓: 100−1000-fold decreased, and ↓↓↓↓: ≥ 1000-fold decreased.

Substitutions of the second group (F, L, and W) are most like wild-type LacI, with only slightly diminished (if at all) DNA binding affinity. Unlike wild-type LacI, these variants frequently exhibit diminished response to inducer. The side chains for these residues all have increased molecular volume, which may influence the structure of the hinge•hinge interface in the presence of DNA. V52A, V52H, V52S, and V52W do not respond to inducer when bound to O1 (Table 2 and Figure 3), whereas all group 1 and 2 variants exhibit this behavior for Osym (Table 2 and Figure 5). However, note that diminished response to inducer does not always correlate with enhanced DNA binding (V52S/Osym, V52H/Osym, V52L/Osym, V52W/Osym, and V52W/O1). This observation suggests that the functions of allostery and DNA binding can be “uncoupled”.

A third group (G and P) exhibits decreased DNA binding affinity for both O1 and Osym that may be ascribed to decreased helix propensity. However, as noted earlier, this decrease is not as dramatic as might be expected for “helix breakers”.

Group 4 includes Q and T substitutions, which have some similarities to group 3 behaviors, with DNA binding affinity further decreased and normal response to inducer. However, threonine at V52 is singular in its effects on DNA binding. Although V52T remains inducible, operator affinity is diminished for all sequences examined, comparable for O1 to V52R. This result is interesting in that threonine is most isosteric to valine and might therefore be anticipated to have the least impact. However, the introduction of the hydrophilic hydroxyl into the hydrophobic environment of the hinge•hinge interface must be highly disruptive, paralleling the introduction of positive charge at this site. The glutamine substitution is less disruptive but exhibits similar effects. DNA binding affinity is dramatically decreased in group 5 (D, E, and R), presumably due to the charge-charge repulsion with DNA (D and E) and within the hinge•hinge interface (R), as mentioned previously.

Together, these data indicate that helix propensity may contribute to DNA binding affinity, but only if no other features impact the hinge•hinge interface (e.g., polarity, charge repulsion, steric influence, etc.). In Group 1 and 2 variants, which appear to either enhance hinge•hinge stability or alter hinge•hinge interaction, inducer response for operator binding is diminished. Thus, helix propensity and hinge•hinge interaction appear to contribute to inducibility. However, the observation that L and F substitutions at position 52 exhibit decreased inducibility for Osym, but not for O1 suggests that DNA sequences also play an important role in determining the functional properties of these V52 variants.

In fact, the effects of altered operator sequence on the binding properties of V52 mutants are seen in several instances (Table 6). These patterns do not always fall neatly into the groups of Table 5. More mutants exhibit decreased inducibility for Osym than for O1, but all substitutions capable of binding OdisC appear inducible (see Table 4). The ratio of operator binding affinities between different operator sequences (Osym/O1, OdisB/O1, and OdisC/O1) illuminates the effects of operator variants on different V52 mutant proteins (Table 6). The tighter binding proteins for O1 (V52A and V52H) bind Osym with affinities comparable to O1, whereas most mutants and wild-type LacI bind to Osym >5-fold tighter than to O1. In contrast, V52Q, which has lower affinity for O1, Osym, and OdisC, was able to bind OdisB, for which only one other mutant (V52S) exhibited detectable affinity. For OdisC/O1, V52A, V52H, and V52P retain their status of tighter binding relative to wild-type LacI, whereas V52W exhibits a large decrease in operator binding affinity.

Table 6.

Operator binding affinity ratiosa

| Osym/O1 | OdisB/O1 | OdisC/O1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WTLacI | 0.12 ± 0.33 | >100000 | 253 ± 68 |

| V52A | 1.1 ± 0.57 | >100000 | 75 ± 11 |

| V52C-redb | 0.29 ± 0.29 | >100000 | 2.3 ± 0.7 |

| V52F | 0.08 ± 0.10 | >100000 | >100000 |

| V52G | 0.11 ± 0.24 | >100000 | >100000 |

| V52H | 0.57 ± 0.52 | >100000 | 170 ± 110 |

| V52L | 0.12 ± 0.18 | >100000 | >100000 |

| V52P | 0.36 ± 0.14 | >100000 | 59 ± 13 |

| V52Q | 0.09 ± 0.18 | 390 ± 11 | 400 ± 11 |

| V52S | 0.21 ± 0.16 | 2600 ± 570 | 190 ± 42 |

| V52T | 0.16 ± 0.42 | >100000 | 280 ± 120 |

| V52W | 0.11 ± 0.27 | >100000 | 1000 ± 480 |

Note that operator variants affect operator binding affinities of V52 substitutions differently. Overall, Osym binds tighter to mutants (except V52A, V52H, and V52P) than O1, whereas OdisB and OdisC are generally weaker. Two tighter binders of O1 (V52A and V52H) lose their status as tighter binders for Osym and OdisB and regain tighter binding for OdisC. Notably, V52Q and V52S (which bind O1 much more weakly and about the same as wild-type, respectively) are the only two variants that bind OdisB, which suggests that DNA properties can functionally dominate features of protein structure.

From Falcon and Mathews (37).

Different operator sequences thus appear to play distinct roles in operator binding. This behavior was previously noted for other LacI hinge mutants (29, 36, 37, 39). The first of these proteins had a cysteine substitution position 52, so that a disulfide bond could be formed between the hinge helices. A second series of variants introduced 1−3 glycine insertions after the hinge helix but before the rest of the LacI core domain. In both cases, when operator DNA sequence was varied, allosteric response was altered in the repressor variant. Although these original substitutions cause rather drastic changes to protein structure, the current data for V52 substitutions show the same behavior with even conservative point mutations.

Structurally, the current and published data suggest that interactions between DNA, hinge helices, the N-terminal DNA binding domains, and the core domains are inter-dependent (36, 37, 55, 77, 78). In particular, OdisB binding by V52Q and V52S suggests that operator•protein interactions can even override intrinsic helix propensity and helix•helix interactions. Changes in DNA structure may influence the orientation and position of the hinge helices and thereby affect the other sets of interactions in which the hinge region is involved. We are now exploring possible structural alterations using small-angle X-ray scattering to correlate changes in protein dimensions with the degree of allosteric response.

Among the different members of the LacI/GalR family, residues at position 52 vary widely, with a slight preference for hydrophobic residues (76). An intriguing possibility is that variant lac operator sequences that are bound uniquely by V52 variants may mimic the different operator sequences recognized by various members of the LacI/GalR family. Indeed, many transcription factors regulate multiple operons (or the eukaryotic equivalents) which usually have varied DNA binding sites. Thus, in addition to altered affinity, different DNA binding sites may alter allosteric regulation of the protein, resulting in different levels of transcription for each gene.

Protein•DNA interactions have been the subject of significant study over the past several decades (e.g., (36, 37, 62, 78-82)). However, most of this work has focused on the role of protein, with DNA usually considered to be a passive partner in these interactions (36). We show here that for LacI, DNA sequence plays an active role in complex formation (19, 29, 36, 37, 39, 55, 78). These findings are consistent with the hypotheses of Kalodimos and colleagues, who suggested that the DNA sequence may shift and redistribute the equilibrium population of the protein conformational substates (19, 21, 22). The studies reported herein confirm that operator sequence may exert a dominant influence in the character of protein•DNA interactions, even influencing how protein function is allosterically regulated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Daniel J. Catanese, Jr. for assistance with the magnetic circular dichroism measurements, Drs. Graham Palmer and Yury Kamensky for access to the instrument and assistance with magnetic circular dichroism measurements, and members of the Matthews laboratory for stimulating discussions and effective feedback.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH Grant GM22441 and Robert A. Welch Grant C-576 to Kathleen Shive Matthews. Liskin Swint-Kruse is supported by NIH Grant P20 RR17708 from the Institutional Development Award program of the National Center for Research Resources.

ABBREVIATIONS: DBD, DNA binding domain of LacI; HTH, helix-turn-helix structure of LacI N-terminal domain; IPTG, isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside; LacI, lactose repressor protein; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; TMD, targeted molecular dynamics.

In the absence of lactose, tetrameric LacI binds to its target site upstream of the lac operon structural genes and inhibits mRNA transcription (1-3). A protein conformational change occurs upon the binding of inducer allolactose (or the gratuitous inducer IPTG), which decreases LacI operator affinity and releases repression (1, 3-5).

REFERENCE

- 1.Gilbert W, Müller-Hill B. Isolation of the lac repressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1966;56:1891–1898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.56.6.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthews KS, Nichols JC. Lactose repressor protein: Functional properties and structure. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1998;58:127–164. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Straney DC, Crothers DM. Effect of drug-DNA interactions upon transcription initiation at the lac promoter. Biochemistry. 1987;26:1987–1995. doi: 10.1021/bi00381a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin S-Y, Riggs AD. A comparison of lac repressor binding to operator and to nonoperator DNA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1975;62:704–710. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(75)90456-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jobe A, Bourgeois S. lac repressor-operator interaction. VI. The natural inducer of the lac operon. J. Mol. Biol. 1972;69:397–408. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Coupling of folding and binding for unstructured proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002;12:54–60. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laity JH, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. DNA-induced alpha-helix capping in conserved linker sequences is a determinant of binding affinity in Cys2-His2 zinc fingers. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;295:719–727. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu J, Winans SC. The quorum-sensing transcriptional regulator TraR requires its cognate signaling ligand for protein folding, protease resistance, and dimerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:1507–1512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aivazian D, Stern LJ. Phosphorylation of T cell receptor zeta is regulated by a lipid dependent folding transition. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:1023–1026. doi: 10.1038/80930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weaver LH, Kwon K, Beckett D, Matthews BW. Corepressor-induced organization and assembly of the biotin repressor: A model for allosteric activation of a transcriptional regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:6045–6050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111128198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Love JJ, Li X, Case DA, Giese K, Grosschedl R, Wright PE. Structural basis for DNA bending by the architectural transcription factor LEF-1. Nature. 1995;376:791–795. doi: 10.1038/376791a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crivici A, Ikura M. Molecular and structural basis of target recognition by calmodulin. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1995;24:85–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.24.060195.000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuxreiter M, Simon I, Friedrich P, Tompa P. Preformed structural elements feature in partner recognition by intrinsically unstructured proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;338:1015–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis M, Chang G, Horton NC, Kercher MA, Pace HC, Schumacher MA, Brennan RG, Lu P. Crystal structure of the lactose operon repressor and its complexes with DNA and inducer. Science. 1996;271:1247–1254. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5253.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell CE, Lewis M. A closer view of the conformation of the Lac repressor bound to operator. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:209–214. doi: 10.1038/73317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman AM, Fischmann TO, Steitz TA. Crystal structure of lac repressor core tetramer and its implications for DNA looping. Science. 1995;268:1721–1727. doi: 10.1126/science.7792597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bell CE, Lewis M. The Lac repressor: A second generation of structural and functional studies. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:19–25. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell CE, Barry J, Matthews KS, Lewis M. Structure of a variant of lac repressor with increased thermostability and decreased affinity for operator. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313:99–109. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalodimos CG, Boelens R, Kaptein R. Toward an integrated model of protein-DNA recognition as inferred from NMR studies on the lac repressor system. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:3567–3586. doi: 10.1021/cr0304065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalodimos CG, Biris N, Bonvin AMJJ, Levandoski MM, Guennuegues M, Boelens R, Kaptein R. Structure and flexibility adaptation in nonspecific and specific protein-DNA complexes. Science. 2004;305:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1097064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalodimos CG, Boelens R, Kaptein R. A residue-specific view of the association and dissociation pathway in protein--DNA recognition. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:193–197. doi: 10.1038/nsb763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalodimos CG, Folkers GE, Boelens R, Kaptein R. Strong DNA binding by covalently linked dimeric Lac headpiece: Evidence for the crucial role of the hinge helices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:6039–6044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101129898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spronk CAEM, Slijper M, van Boom JH, Kaptein R, Boelens R. Formation of the hinge helix in the lac repressor is induced upon binding to the lac operator. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:916–919. doi: 10.1038/nsb1196-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spronk CAEM, Bonvin AMJJ, Radha PK, Melacini G, Boelens R, Kaptein R. The solution structure of Lac repressor headpiece 62 complexed to a symmetrical lac operator. Structure. 1999;7:1483–1492. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)88339-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swint-Kruse L, Brown CS. Resmap: Automated representation of macromolecular interfaces as two-dimensional networks. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3327–3328. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nichols JC, Matthews KS. Combinatorial mutations of lac repressor: Stability of monomer-monomer interface is increased by apolar substitution at position 84. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:18550–18557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J, Matthews KS. Deletion of lactose repressor carboxyl-terminal domain affects tetramer formation. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:13843–13850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wycuff DR, Matthews KS. Generation of an AraC-araBAD promoter-regulated T7 expression system. Anal. Biochem. 2000;277:67–73. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Falcon CM, Swint-Kruse L, Matthews KS. Designed disulfide between N-terminal domains of lactose repressor disrupts allosteric linkage. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:26818–26821. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.26818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swint-Kruse L, Zhan H, Fairbanks BM, Maheshwari A, Matthews KS. Perturbation from a distance: Mutations that alter LacI function through long-range effects. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14004–14016. doi: 10.1021/bi035116x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swint-Kruse L, Matthews KS. Thermodynamics, protein modification, and molecular dynamics in characterizating lactose repressor protein: Strategies for complex analyses of protein structure-function. Methods Enzymol. 2004;379:188–209. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)79011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Gorman RB, Dunaway M, Matthews KS. DNA binding characteristics of lactose repressor and the trypsin-resistant core repressor. J. Biol. Chem. 1980;255:10100–10106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riggs AD, Bourgeois S, Newby RF, Cohn M. DNA binding of the lac repressor. J. Mol. Biol. 1968;34:365–368. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmquist B, Vallee BL. Tryptophan quantitation by magnetic circular dichroism in native and modified proteins. Biochemistry. 1973;12:4409–4417. doi: 10.1021/bi00746a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong I, Lohman TM. A double-filter method for nitrocellulose-filter binding: Application to protein-nucleic acid interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:5428–5432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Falcon CM, Matthews KS. Operator DNA sequence variation enhances high affinity binding by hinge helix mutants of lactose repressor protein. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11074–11083. doi: 10.1021/bi000924z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Falcon CM, Matthews KS. Engineered disulfide linking the hinge regions within lactose repressor dimer increases operator affinity, decreases sequence selectivity, and alters allostery. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15650–15659. doi: 10.1021/bi0114067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spotts RO, Chakerian AE, Matthews KS. Arginine 197 of lac repressor contributes significant energy to inducer binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:22998–23002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Falcon CM, Matthews KS. Glycine insertion in the hinge region of lactose repressor protein alters DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:30849–30857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laiken SL, Gross CA, von Hippel PH. Equilibrium and kinetic studies of Escherichia coli lac repressor-inducer interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 1972;66:143–155. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(72)80012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gardner JA, Matthews KS. Characterization of two mutant lactose repressor proteins containing single tryptophans. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:21061–21067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Royer CA, Gardner JA, Beecham JM, Brochon J-C, Matthews KS. Resolution of the fluorescence decay of the two tryptophan residues of lac repressor using single tryptophan mutants. Biophys J. 1990;58:363–378. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82383-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suckow J, Markiewicz P, Kleina LG, Miller J, Kisters-Woike B, Müller-Hill B. Genetic studies of the Lac repressor XV: 4000 single amino acid substitutions and analysis of the resulting phenotypes on the basis of the protein structure. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;261:509–623. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Markiewicz P, Kleina LG, Cruz C, Ehret S, Miller JH. Genetic studies of the lac repressor. XIV. Analysis of 4000 altered Escherichia coli lac repressors reveals essential and non-essential residues, as well as “spacers” which do not require a specific sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;240:421–433. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daly TJ, Matthews KS. Characterization and modification of a monomeric mutant of the lactose repressor protein. Biochemistry. 1986;25:5474–5478. doi: 10.1021/bi00367a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chakerian AE, Matthews KS. Characterization of mutations in oligomerization domain of lac repressor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:22206–22214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chakerian AE, Tesmer VM, Manly SP, Brackett JK, Lynch MJ, Hoh JT, Matthews KS. Evidence for leucine zipper motif in lactose repressor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:1371–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Creamer TP, Campbell MN. Determinants of the polyproline two helix from modeling studies. Adv Protein Chem. 2002;62:263–282. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(02)62010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swint-Kruse L, Zhan H, Matthews KS. Integrated insights from simulation, experiment, and mutational analysis yield new details of LacI function. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11201–11213. doi: 10.1021/bi050404+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barry JK, Matthews KS. Substitutions at histidine 74 and aspartate 278 alter ligand binding and allostery in lactose repressor protein. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3579–3590. doi: 10.1021/bi982577n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gilbert W, Gralla F, Majors J, Maxam A. In: Symposium on protein-ligand interactions. Sund H, Blauer G, editors. 1975. pp. 193–206. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Caruthers MH, Beaucage SL, Efcavitch JW, Fisher EF, Goldman RA, deHaseth PL, Mandecki W, Matteucci MD, Rosendahl MS, Stabinsky Y. Chemical synthesis and biological studies on mutated gene-control regions. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1983;47 Pt 1:411–418. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1983.047.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Betz JL, Sasmor HM, Buck F, Insley MY, Caruthers MH. Base substitution mutants of the lac operator: In vivo and in vitro affinities for lac repressor. Gene. 1986;50:123–132. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90317-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sadler JR, Sasmor H, Betz JL. A perfectly symmetric lac operator binds the lac repressor very tightly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1983;80:6785–6789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.22.6785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spronk CAEM, Folkers GE, Noordman AMGW, Wechselberger R, van den Brink N, Boelens R, Kaptein R. Hinge-helix formation and DNA bending in various lac repressor-operator complexes. EMBO J. 1999;18:6472–6480. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sasmor HM, Betz JL. Symmetric lac operator derivatives: Effects of half-operator sequence and spacing on repressor affinity. Gene. 1990;89:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90198-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dickerson RE. DNA bending: The prevalence of kinkiness and the virtues of normality. Nucleic Acids. Res. 1998;26:1906–1926. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.8.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Juo ZS, Chiu TK, Leiberman PM, Baikalov I, Berk AJ, Dickerson RE. How proteins recognize the TATA box. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;261:239–254. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spolar RS, Record MT., Jr. Coupling of local folding to site-specific binding of proteins to DNA. Science. 1994;263:777–784. doi: 10.1126/science.8303294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holmbeck SMA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. DNA-induced conformational changes are the basis for cooperative dimerization by the DNA binding domain of the retinoid X receptor. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;284:533–539. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tompa P, Csermely P. The role of structural disorder in the function of RNA and protein chaperones. FASEB J. 2004;18:1169–1175. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1584rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lejeune D, Delsaux N, Charloteaux B, Thomas A, Brasseur R. Protein-nucleic acid recognition: Statistical analysis of atomic interactions and influence of DNA structure. Proteins. 2005;61:258–271. doi: 10.1002/prot.20607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anzellotti AI, Ma ES, Farrell N. Platination of nucleobases to enhance noncovalent recognition in protein-DNA/RNA complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:483–485. doi: 10.1021/ic049086d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koudelka GB. Recognition of DNA structure by 434 repressor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:669–675. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dupureur CM. NMR studies of restriction enzyme-DNA interactions: Role of conformation in sequence specificity. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5065–5074. doi: 10.1021/bi0473758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lu F, Brennan RG, Zalkin H. Escherichia coli purine repressor: Key residues for the allosteric transition between active and inactive conformations and for interdomain signaling. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15680–15690. doi: 10.1021/bi981617k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Glasfeld A, Schumacher MA, Choi K-Y, Zalkin H, Brennan RG. A positively charged residue bound in the minor groove does not alter the bending of a DNA duplex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:13073–13074. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Swint-Kruse L. Using networks to identify fine structural differences between functionally distinct protein states. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10886–10895. doi: 10.1021/bi049450k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Koehl P, Levitt M. Structure-based conformational preferences of amino acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:12524–12529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Luque I, Mayorga OL, Freire E. Structure-based thermodynamic scale of α-helix propensities in amino acids. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13681–13688. doi: 10.1021/bi961319s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chou PY, Fasman GD. Conformational parameters for amino acids in helical, β-sheet, and random coil regions calculated from proteins. Biochemistry. 1974;13:211–222. doi: 10.1021/bi00699a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Iqbalsyah TM, Doig AJ. Effect of the N3 residue on the stability of the α-helix. Protein Sci. 2004;13:32–39. doi: 10.1110/ps.03341804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Penel S, Hughes E, Doig AJ. Side-chain structures in the first turn of the α-helix. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;287:127–143. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zamyatnin AA. Amino acid, peptide, and protein volume in solution. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 1984;13:145–165. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.13.060184.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Swint-Kruse L, Larson C, Pettitt BM, Matthews KS. Fine-tuning function: Correlation of hinge domain interactions with functional distinctions between LacI and PurR. Protein Sci. 2002;11:778–794. doi: 10.1110/ps.4050102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bell CE, Lewis M. Crystallographic analysis of Lac repressor bound to natural operator O1. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;312:921–926. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kalodimos CG, Bonvin AMJJ, Salinas RK, Wechselberger R, Boelens R, Kaptein R. Plasticity in protein-DNA recognition: Lac repressor interacts with its natural operator O1 through alternative conformations of its DNA-binding domain. EMBO J. 2002;21:2866–2876. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Steitz TA. Structural studies of protein-nucleic acid interaction: The sources of sequence-specific binding. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1990;23:205–280. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500005552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ohlendorf DH, Matthews BW. Structural studies of protein-nucleic acid interactions. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 1983;12:259–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.12.060183.001355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Morozov AV, Havranek JJ, Baker D, Siggia ED. Protein-DNA binding specificity predictions with structural models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5781–5798. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Feng H, Dong L, Klutz AM, Aghaebrahim N, Cao W. Defining amino acid residues involved in DNA-protein interactions and revelation of 3'-exonuclease activity in endonuclease V. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11486–11495. doi: 10.1021/bi050837c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gilbert W, Maizels N, Maxam A. Sequences of controlling regions of the lactose operon. Cold Spr. Harbor. Symp. 1973;38:845–855. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1974.038.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]