Abstract

Selective synthesis and release of FSH from pituitary gonadotropes is regulated by activins. Activins directly stimulate murine FSHβ (Fshb) subunit gene transcription through a consensus 8-bp Sma- and Mad-related protein-binding element (SBE) in the proximal promoter. In contrast, the human FSHB promoter is relatively insensitive to the direct effects of activins and lacks this SBE. The proximal porcine Fshb promoter, which is highly conserved with human, similarly lacks the 8-bp SBE, but is nonetheless highly sensitive to activins. We used a comparative approach to determine mechanisms mediating differential activin induction of human, porcine, and murine Fshb/FSHB promoters. We mapped an activin response element in the proximal porcine promoter and identified interspecies variation in a single base pair in close proximity that conferred strong binding of the forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 to the porcine, but not human or murine, promoters. Introduction of the human base pair into the porcine promoter abolished FOXL2 binding and activin A induction. FOXL2 conferred activin A induction to the porcine promoter in heterologous cells, whereas knockdown of the endogenous protein in gonadotropes inhibited the activin A response. The murine Fshb promoter lacks the high-affinity FOXL2-binding site, but its activin induction is FOXL2 sensitive. We identified a more proximal FOXL2-binding element in the murine promoter, which is conserved across species. Mutation of this site attenuated activin A induction of both the porcine and murine promoters. Collectively, the data indicate a novel role for FOXL2 in activin A-regulated Fshb transcription.

The forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 binds to distinct and conserved elements in the proximal FSHbeta subunit gene promoter, mediating activin induction in species-specific fashion.

FSH, a dimeric glycoprotein product of gonadotrope cells of the anterior pituitary gland, is fundamentally required for fertility. Female mice lacking the FSHβ (Fshb) subunit are infertile due to a block in ovarian follicle maturation beyond the preantral stage (1). Similarly, inactivating mutations in the human FSHB subunit that block mature hormone synthesis lead to primary amenorrhea and infertility in women (2,3,4). Inactivating mutations in the FSH receptor (FSHR/Fshr) in humans and mice produce similar phenotypes (5,6,7).

In rats and mice, there is a pronounced and selective elevation in FSH synthesis and secretion the morning after the preovulatory (primary) gonadotropin surges, which is largely dependent upon declines in ovarian inhibins (8). Inhibins are TGFβ superfamily proteins that selectively suppress pituitary FSH without affecting LH secretion (9,10,11). A second group of structurally related ligands, the activins, selectively stimulate FSH synthesis and secretion (12,13). The current model holds that intrapituitary activins stimulate FSH synthesis in gonadotrope cells via transcriptional regulation of the Fshb gene, the rate-limiting step in mature hormone synthesis. Gonadal inhibins produce their inhibitory effects on FSH in endocrine fashion by antagonizing autocrine/paracrine activins (14,15,16).

Activins, like other TGFβ ligands, signal via complexes of type I and type II receptor serine/threonine kinases. The type II receptors bind ligand and then trans-phosphorylate the type I receptors [also known as activin receptor-like kinase 4 (ALK4)]. This activates the type I receptors, which propagate intracellular signaling via phosphorylation of effector proteins, the best studied of which are Sma- and Mad-related proteins (Smads) 2 and 3. Phosphorylated Smads accumulate in the nucleus where they regulate target gene transcription in association with other nuclear proteins (17,18). Inhibins can bind activin type II receptors, but this binding does not promote type I receptor activation, providing a mechanism for competitive antagonism of activin signaling (19,20).

We and others showed that activins stimulate the rapid carboxyl-terminal phosphorylation and nuclear accumulation of Smads 2 and 3 in the murine gonadotrope cell line, LβT2 (21,22,23). We further demonstrated that activin A stimulates the formation of Smad2/3/4 complexes that can bind to a consensus 8-bp Smad-binding element (SBE) at −266/−259 of the murine Fshb promoter and that this cis-element is necessary for both rapid and robust trans-activation by activins (24). Similar data have been reported for the rat Fshb promoter (25,26). We further showed that the human FSHB promoter is relatively insensitive to the direct actions of activins/Smads and lacks the SBE. When we introduced the SBE into a human FSHB promoter-reporter, we observed a marked increase in activin A induction (24). Based on these observations, we postulated that, in the context of low inhibin levels, the presence of the 8-bp SBE permits rapid (direct) and robust activation of the rodent Fshb promoters by activins and generation of the secondary FSH surge on estrus morning (24).

In women, progesterone, estradiol, and inhibin A levels decline at the end of the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle (27), providing a permissive endocrine environment for increases in FSH synthesis and secretion at this stage of the cycle. Increases in FSH levels at the luteal-follicular phase transition, however, are modest compared with the secondary surge observed in rodents. We argued that this muted response might derive from the relative insensitivity of the human FSHB promoter to the direct actions of activins, due to the absence of the SBE.

Strikingly and in apparent contrast to this hypothesis, the porcine Fshb promoter is highly activin A responsive (28,29), but lacks the 8-bp SBE. Moreover, the proximal Fshb promoter in pig is more similar to human FSHB (∼90% identity within the proximal ∼330 bp) than murine Fshb (∼70%) (see Fig. 1). Thus, the simple presence or absence of the 8-bp SBE alone cannot explain all interspecies differences in activin responsiveness of the FSHB/Fshb promoter. Here, we compared the highly conserved human and porcine FSHB/Fshb promoters to discern additional and/or alternative activin-responsive cis-elements. Our results demonstrate a novel role for the forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 in species-specific responses of the Fshb/FSHB promoters to activins.

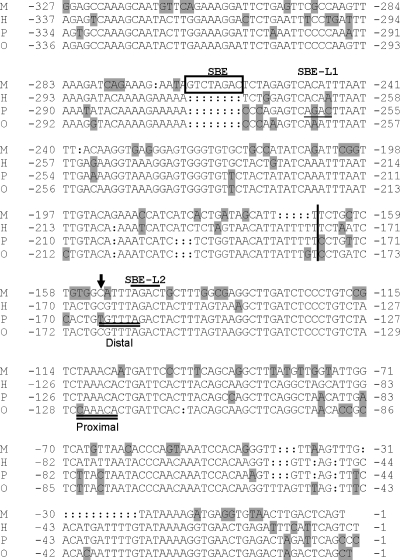

Figure 1.

Alignment of proximal Fshb/FSHB promoter sequences in mouse (M), human (H), pig (P), and sheep (O). In all cases, −1 refers to the first base pair 5′ to the start of transcription. Shaded nucleotides reflect differences from the consensus and colon denotes gaps introduced to facilitate the alignments. The 8-bp SBE in the rodent promoters is boxed. Two SBE-like elements in the porcine promoter are underlined (SBE-L1) and overlined (SBE-L2), respectively. The breakpoint in the human/porcine chimeric reporters is denoted by a thick vertical line. The distal FOXL2 binding site in the porcine promoter is double underlined, with the base pair mediating unique FOXL2 binding marked with an arrow. The conserved FOXL2 binding site is double underlined and marked “proximal.”

Results

cis-Elements required for activin induction map to the proximal Fshb promoter

In reporter assays in LβT2 cells, we observed previously that the −1369/+8 porcine promoter (−1369/+8 pFshb-luc) was highly activin A responsive (28). We confirmed and extended these results by examining time-dependent regulation of −1369/+8 pFshb-luc relative to a murine Fshb reporter of similar length (−1195/+1 mFshb-luc). The porcine promoter-reporter was more strongly stimulated by activin A than the murine reporter at 8 and 24 h (Fig. 2A). At 4 h, the two were stimulated to comparable levels. These data confirmed that the 8-bp SBE, which is absent in pig, was not required for potent activin A induction.

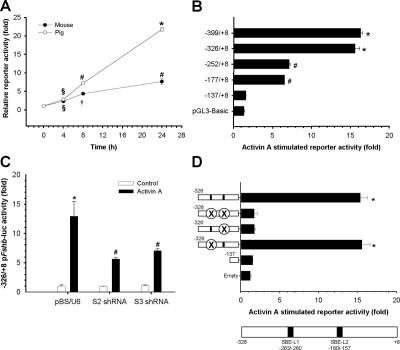

Figure 2.

A, LβT2 cells transfected with −1369/+8 porcine (open circles) or −1195/+1 murine (closed circles) Fshb-luc reporters (450 ng/well) were treated with 1 nm activin A for 0, 4, 8, or 24 h. Shown is the mean (+sd) reporter activity relative to basal activity in the absence of exogenous activin A for each construct. B, Cells were transfected with the indicated porcine Fshb reporters and treated as in panel A for 24 h. C, LβT2 cells were transfected with the −326/+8 pFshb-luc reporter along with pBS/U6 (empty vector), Smad2 (S2) shRNA, or Smad3 (S3) shRNA vectors. The following day, cells were treated for 24 h with 1 nm activin A. D, Cells were transfected with the porcine −326/+8 Fshb-luc reporter containing point mutations in two candidate SBEs (SBE-L1 and SBE-L2) alone and together. Alterations in the response to 24 h activin A were measured. A schematic representation of the relative positions of SBE-L1 and SBE-L2 is pictured below the graph. In panels A–D, all the treatments were performed in duplicate or triplicate, and experiments were repeated three times. Here and in subsequent figures, data shown are from representative experiments, and bars or points with different symbols differ significantly.

To delineate activin A-responsive regions of the porcine promoter, we prepared 5′-deletion constructs. Truncations to −767 or −399 did not significantly alter the fold activin A response relative to −1369; however, trimming the promoter to −137 or −73 completely abolished activin A induction (data not shown). Truncation from −399 to −326 was without effect, whereas deletion to −252 inhibited the fold activin A response by more than half. This level of activation was maintained through −177, but was completely lost with deletion of the sequence between −177 and −137 (Fig. 2B).

Having defined −326/+8 and −177/+8 as required for maximal and minimal activin A induction, we adopted a chimeric reporter strategy with segments of the highly conserved human and porcine proximal promoters to determine necessary and sufficient sequences for activin induction. (see schematic in supplemental Fig. S1A published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org). The data suggested that sequence present in the porcine but absent from the human promoter within 177 bp of the transcription start site was required for activin A induction. Additional differences upstream of −177 (particularly between −252 and −326, Fig. 2B) contributed to the overall magnitude of the activin A response, but only in the context of the permissive proximal promoter (supplemental Fig. S1A). Chimeric reporters with human and murine sequences similarly mapped necessary activin response element(s) to the proximal promoter (supplemental Fig. S1B).

A role for Smads in regulation of the porcine Fshb gene by activin A

The most thoroughly characterized effectors of activin signaling are the receptor-regulated Smad proteins, Smads 2 and 3. Although the proximal porcine Fshb promoter lacks the 8-bp SBE, it contains two minimal Smad recognition sequences, AGAC, within the activin A-responsive regions identified above: −263/−260 [hereafter referred to as “SBE-like 1,” (SBE-L1), see more below] within −326/−252 and −160/−157 (SBE-L2) within −177/−137 (Fig. 1). We therefore examined Smad induction of the porcine Fshb promoter. We knocked down Smad2 or Smad3 protein levels in LβT2 cells with previously validated short hairpin (sh) RNAs (22). Both constructs inhibited activin A induction by about 50% without affecting basal reporter activity (Fig. 2C).

Having established that activin A signaled through Smads 2 and 3, at least in part, to regulate the porcine Fshb promoter, we next probed the potential involvement of SBE-L1 and SBE-L2. We introduced mutations into the first 2 bp (from the 5′-end) of both sites alone and together in the context of the −326/+8 pFshb-luc reporter. Mutation of the more proximal site, SBE-L2, completely abolished the fold activin A response, whereas the SBE-L1 mutation had little or no effect (Fig. 2D). The SBE-L2 site is conserved in the murine Fshb promoter (−148/−145) and was previously shown to mediate part of the activin A and Smad3 responses of a murine reporter in LβT2 cells (30,31). We observed that mutations of this or the 8-bp SBE had equivalent inhibitory effects on the activin A response of a murine reporter (supplemental Fig. S1C). The effect of mutating both sites simultaneously was more pronounced than either alone, though there was still a residual activin A response at 24 h, indicating that mechanisms governing activin A induction of the murine and porcine Fshb promoters were both common and distinct. In both cases, SBE-L2 was necessary for the full activin A induction.

Common and distinct protein complexes bind the porcine and human promoters

We next examined whether SBE-L2 binds Smads 2, 3, and/or 4 using radiolabeled murine (−159/−137) or porcine (−172/−145) probes containing the SBE-L2 sequence in gel-shift analyses. Whereas we failed to detect activin A-stimulated protein-DNA complexes from LβT2 cells, we observed weak binding by recombinant Smads 3 and 4 (supplemental Fig. S2A). Mutation of any of the 4 bp individually within the 5′-AGAC-3′ element was sufficient to abrogate completely activin A induction of the −326/+8 porcine reporter (supplemental Fig. S2B). These base pairs are perfectly conserved in the FSHB/Fshb promoters across species, including the activin A-insensitive human (Fig. 1), indicating that, although necessary for activin induction, they are not sufficient.

We therefore searched for interspecies sequence differences in the proximity of this site. Within 17 bp 5′ to SBE-L2, 5 bp differ between the human and porcine promoters (a 30% difference). We therefore focused on this as a candidate region mediating differences in activin A sensitivity. We generated double-stranded DNA probes spanning −185/−145 of both the human and porcine promoters and used them in gel-shift analyses with LβT2 cell nuclear extracts. With the porcine probe, we detected four specific complexes (Fig. 3A, lane 1, labeled “a” through “d” at left) that could be competed completely by 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled homologous probe (lane 2). In contrast, the unlabeled human probe could compete for binding to complex a, but little or not at all to complexes b–d (lane 3). The radiolabeled human probe formed three discernible complexes with the LβT2 cell nuclear extracts (lane 4). Two showed similar migration to complexes a and b seen with the porcine probe. Only complex a was completely competed by the unlabeled porcine probe (lane 5). The human probe did not appear to bind the proteins in complexes c or d, but formed a novel, robust complex (labeled “e” at right), which was competed effectively by the unlabeled homologous probe (lane 6) but less so by the heterologous porcine probe (lane 5). Activin A treatment did not detectably alter complex binding to either probe (data not shown). Therefore, in subsequent binding experiments, nuclear extracts from activin A-treated LβT2 cells were used (except where noted).

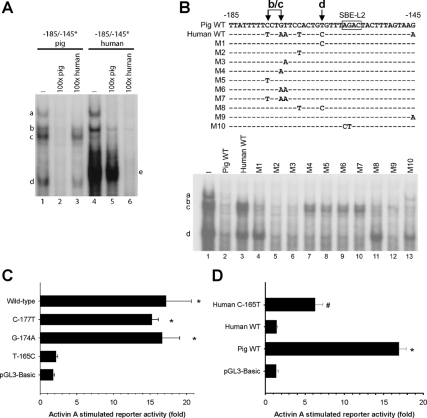

Figure 3.

A, Double-stranded radiolabeled (asterisks) probes corresponding to −185/−145 of the porcine (lanes 1–3) or human (lanes 4–6) Fshb/FSHB promoters were used in gel-shift analyses with LβT2 nuclear extracts. Specificity of complex formation was determined by coincubation with 100× molar excess of unlabeled homologous or heterologous probes (lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6). No complexes were observed when the probes were incubated without nuclear lysates (data not shown). B (top), Schematic representation of the porcine, human, and mutant competitor probes used in competition gel shift assays. Only the top strand is shown in each case. Conserved bases between probes are marked with a dash, and base changes are indicated with the corresponding letter. Bases determined to mediate differential complex formation are indicated at the top. B (bottom), Gel shifts were performed as described in panel A with the radiolabeled porcine probe. The indicated competitor probes (lanes 2–13), at 100× excess, were included to displace the binding observed in lane 1. In panels A and B and subsequent gel-shift assay figures, complexes are labeled at the left and right, free probe is not pictured, and lanes are numbered at the bottom. All presented gel-shift results are from representative experiments that were performed no fewer than two times. C, LβT2 cells were transfected with the −326/+8 pFshb-luc reporter containing the indicated point mutations and then treated with 1 nm activin A for 24 h. Fold activin A response is shown for all constructs. D, LβT2 cells were transfected as described in panel C with the indicated porcine and human Fshb/FSHB reporters and treated with activin A. In panels C and D, all treatments were performed in duplicate, and the experiments were repeated three times.

To determine the base pair(s) mediating the differential complex binding to the porcine promoter sequence, we prepared a series of unlabeled porcine competitor probes, which contained human base pair substitutions at one or more positions (Fig. 3B, top, labeled “M1–M10”). Collectively, the data indicate that the T at −165 of the porcine promoter is necessary for binding of complex d and that the AG at −160/−159, which is common to the promoters of both species, is necessary for maximal binding by complex a. Complexes b and c required C at −177 and G at −174 for binding to the porcine promoter sequence. Although the data with the radiolabeled human probe suggested that complex b might bind independently of complex c (Fig. 3A, lane 4), the competition experiments (e.g. Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 10) suggested that complex b observed with the human and porcine probes might contain distinct proteins, despite their similar mobilities. The key base pairs mediating differential binding of complexes b–d to the porcine promoter are indicated at the top of Fig. 3B.

A single base pair change alters activin A responsiveness of the human FSHB promoter

Having determined specific base pairs involved in binding of distinct protein complexes to the porcine Fshb promoter, we examined their potential roles in differential activin A induction. Introduction of the C-177T (M5) or G-174A (M4) mutations, which inhibited binding of complexes b and c, into the −326/+8 pFshb-luc reporter did not alter the fold activin A response (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the T-165C mutation (M1), which inhibited complex d binding, completely abrogated activin A induction. In reciprocal experiments, the porcine base pair at −165 was introduced into the human −329/+7 hFSHB-luc reporter (C-165T). Remarkably, this single base pair substitution conferred significant activin A induction to the human reporter (Fig. 3D).

The C at −165 in human is highly conserved in other species, including sheep and mouse (see arrow in Fig. 1). In fact, the T at this position is unique to pig among species in which the Fshb promoter has been thoroughly characterized. We had observed that the ovine Fshb promoter, although sensitive to activin A, was less so than the murine or porcine promoters when compared side by side (28). When the C at −167 was replaced with T, the ovine reporter became nearly as sensitive to activin A as the porcine promoter (data not shown). The comparable mutation in the murine reporter, C-153T, also significantly increased the activin A response of that promoter (supplemental Fig. S7B and see more below). Collectively, the data showed that the T at −165, just 5′ of SBE-L2, conferred heightened activin A induction to the porcine Fshb promoter relative to other species.

FOXL2 binds the porcine Fshb promoter

We next sought to identify the constituent protein(s) in complex d. Using an on-line transcription factor binding site prediction program (CONSITE, http://asp.ii.uib.no:8090/ cgi-bin/CONSITE/consite/) (32), a putative binding site for FREAC-4 (GTGTTTAG) was observed when the porcine, but not human, sequence was used in the search. The underlined T corresponds to bp −165, and is the only base pair in the predicted element that differed between pig and human. The AG at −160/−159 (italicized), which we showed was important for both the activin A response (Figs. 2D and supplemental Fig. S2B) and complex a and d binding (Figs. 3B and 4C), also appeared to be contained within the predicted binding element.

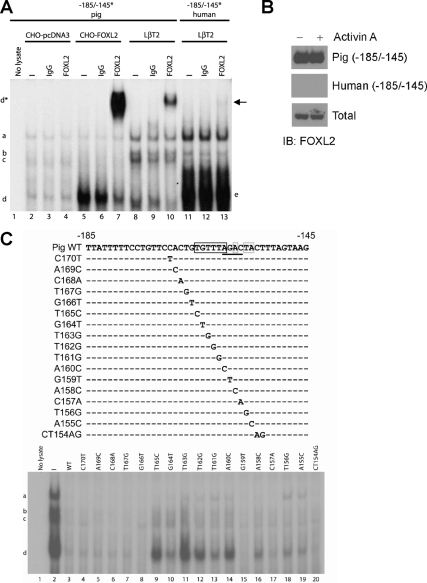

Figure 4.

A, Double-stranded radiolabeled (asterisks) probes corresponding to −185/−145 of the porcine (lanes 1–10) and human (lanes 11–13) Fshb/FSHB promoters were used in gel-shift analyses with nuclear extracts from CHO cells transfected with pcDNA3 (empty vector, lanes 2–4) or HA-FOXL2 (lanes 5–7), or from LβT2 cells (lanes 8–13). Supershifts were performed by coincubating with control IgG (lanes 3, 6, 9, 12) or with FOXL2 antibody (lanes 4, 7, 10, and 13). Arrow shows the faint complex in lane 13. B, Immunoblot (IB) was performed with the FOXL2 antibody on LβT2 whole-cell extracts (total; lower panel) as well as proteins eluted from biotinylated −185/−145 porcine (upper panel) or human (middle panel) DNA probes incubated with control (left lane) or activin A-stimulated (right lane) extracts. C (top), Schematic representation of the mutant porcine probes used in competition gel-shift assays as in Fig. 3B. C (bottom), Gel shifts were performed with the radiolabeled WT −185/−145 porcine probe and LβT2 nuclear extracts. The indicated competitor probes, at 100× excess, were included to displace the binding observed in lane 2.

FREAC-4, now referred to as forkhead box D1 (FOXD1), is a member of the forkhead box (FOX) transcription factor family. Members of this family have been implicated in activin/TGFβ signaling previously, both through their interactions with Smad proteins and through binding to cis-elements in close proximity to SBEs (33,34,35). FOXD1 expression in pituitary has not been reported to our knowledge; however, another family member, FOXL2, is expressed in murine gonadotrope cells and was implicated in the mechanism through which activin A regulates murine GNRH1 receptor (Gnrhr) (35,36) and follistatin (Fst; published during the revision of the present paper) (37) gene transcription. We therefore examined whether FOXL2 might be contained within complex d.

We performed gel shifts with LβT2 nuclear extracts using the −185/−145 porcine (Fig. 4A, lanes 8–10) or human radiolabeled probes (lanes 11–13) and observed the same complexes described in Fig. 3A. Here, we included control IgG (lanes 9 and 12) or a polyclonal antibody directed against amino acids 1–14 (MMASYPEPEDTAGT) of murine FOXL2 (lanes 10 and 13). BLASTP search of the nonredundant database did not reveal significant identity between this peptide and any forkhead transcription factor other than FOXL2 in mouse or other species. With the porcine probe, complex d, but not complexes a–c, was supershifted by the FOXL2 antibody (lane 10), but not by control IgG (lane 9). None of the complexes that formed with the human probe were detectably altered by either IgG or anti-FOXL2. However, we noted the appearance of a novel faint complex with the addition of the FOXL2 antibody (lane 13, arrow) that co-migrated at the same level as the supershifted complex d with the porcine probe (lane 10). These data suggested endogenous FOXL2 was contained within complex d and could bind to the porcine Fshb promoter sequence. DNA affinity pull-down (DNAP) assays confirmed the stronger binding of endogenous FOXL2 to the porcine than human promoter sequence (Fig. 4B). As with the gel-shift analyses, activin A treatment did not detectably alter FOXL2 binding.

To further confirm that FOXL2, and not a related protein, was contained within complex d, we used heterologous Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell nuclear extracts in gel-shift analyses. Extracts from cells transfected with empty vector (pcDNA3) formed two distinct complexes with the porcine probe with similar mobilities to complexes a and d (Fig. 4A, lane 2); however, upon closer inspection, the faster mobility complex appeared to migrate more slowly than complex d from LβT2 cells. In fact, this complex was unaltered by inclusion of the FOXL2 antibody (lane 4). When extracts from CHO cells transfected with a murine hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged FOXL2 expression vector were included, an intense complex with similar mobility to complex d appeared that was not observed in control lysates (compare lanes 2 and 5). This complex was supershifted by the FOXL2 antibody to a position comparable to that observed with endogenous proteins in LβT2 cells (compare lanes 7 and 10). Thus, these data confirmed that FOXL2 can bind within −185/−145 of the porcine Fshb promoter.

Introduction of the porcine base pair at −165 into the human reporter (C-165T) conferred activin A induction (Fig. 3D). We next asked whether this substitution was sufficient to confer enhanced FOXL2 binding to the human promoter. C-165T was introduced in the context of a radiolabeled −185/−145 human probe for use in gel shifts. We readily detected endogenous and exogenous FOXL2 binding to this modified probe (supplemental Fig. S3).

Characterization of the FOXL2-binding site

Although bp −165, −160, and −159 (e.g. Fig. 3B) appeared necessary for complex d (and hence FOXL2) binding, we next more systematically addressed which base pairs make up the FOXL2 cis-element. We performed gel shifts with LβT2 nuclear extracts and the radiolabeled WT porcine −185/−145 probe in the presence of the indicated competitor probes (Fig. 4C, top). As summarized by the boxed base pairs in Fig. 4C, FOXL2 binding (complex d) required bp −160→ −165 (black box, lanes 9–14) and, to a lesser extent, bp −155, −156, and −158 (gray boxes, lanes 16, 18, 19). The mutations to bp −165, −163, −162, and −160 were most disruptive to FOXL2 binding. Interestingly, the mutation to bp −159 did not affect FOXL2 binding (lane 15), suggesting that the effect of the 2-bp mutation on complex d binding observed in Fig. 3B (lane 13) was likely attributable to the base pair change at −160 alone. Nevertheless, bp −159 was required for activin A induction of the porcine promoter in reporter assays (supplemental Fig. S2B). These data suggested that FOXL2 bound via the sequence TGTTTAnAnTA, with the TGTTTA core sequence being most critical for binding. This sequence, with the exception of the T in the first position (bp −165), is perfectly conserved in human, suggesting that this single base pair difference alone accounted for differential FOXL2 binding between the two species.

FOXL2 confers activin A responsiveness to the porcine Fshb promoter in heterologous cells

Given that the C-165T mutation conferred both FOXL2 binding and activin A responsiveness to the human FSHB promoter in homologous cells, we asked whether FOXL2 is sufficient to confer activin A responsiveness in heterologous cells. We cotransfected two activin A-responsive heterologous cell lines, HepG2 and CHO, with the −326/+8 pFshb-luc reporter along with empty or FOXL2 expression vector. We then treated cells with 1 nm activin A or control media. In both cell lines, FOXL2 or activin A treatment alone had no effect. However, in the presence of FOXL2, activin A significantly induced promoter activity (Figs. 5A and supplemental Fig. S4A). Introduction of the T-165C mutation into the promoter abolished the response (Fig. 5B), indicating that the effect required the defined FOXL2 binding site. Interestingly, FOXL2 transfection did not confer activin A responsiveness to the human WT (data not shown) or C-165T FSHB promoters (supplemental Fig. S4B). The latter result was unexpected given the introduction of the FOXL2 binding element. Collectively, these data showed that FOXL2 can confer activin A responsiveness to the porcine Fshb promoter in heterologous cells; however, the presence of the FOXL2 binding site alone was insufficient for this response. In other words, additional differences between the porcine and human promoters contributed to activin A induction via FOXL2.

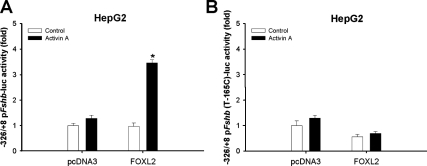

Figure 5.

A, HepG2 cells were transfected with 450 ng/well porcine Fshb reporter and 8.3 ng/well pcDNA3.0 or FOXL2. The following day, cells were treated for 24 h with control or activin A-containing media overnight. B, HepG2 cells were transfected as described in panel A with the T-165C mutant porcine Fshb reporter. Experiments in both panels were performed four times, and data were reported relative to the control condition (pcDNA3, no ligand).

A role for endogenous FOXL2 in activin A induction of porcine Fshb transcription

Next, we addressed the role of endogenous FOXL2 in activin A-regulated porcine Fshb reporter activity by knocking down FOXL2 expression by RNA interference (RNAi) in LβT2 cells. Two short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting different sequences in the Foxl2 mRNA significantly inhibited activin A-regulated porcine Fshb reporter activity and did so to similar extents (Fig. 6A). The same siRNAs similarly inhibited activin A induction of the human C-165T FSHB reporter in LβT2 cells (supplemental Fig. S5A) [and the murine Gnrhr promoter in αT3-1 cells (40) (supplemental Fig. S5B)]. These data suggested that endogenous FOXL2 might play a necessary role in activin A-regulated transcription.

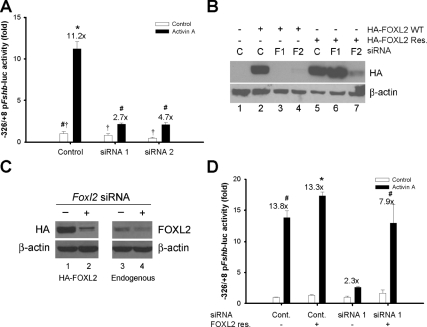

Figure 6.

A, LβT2 cells were cotransfected with 450 ng/well WT porcine Fshb-luc and 5 nm control, Foxl2 siRNA no. 1, or Foxl2 siRNA no. 2. The following day cells were treated overnight with control or activin A-containing media. Fold activin A induction is shown above the bars for each condition. B, CHO cells in 10-cm plates were cotransfected with 2 μg WT (lanes 2–4) or siRNA no. 1 resistant (Res., lanes 5–7) HA-FOXL2, and 5 nm control (C, lanes 1, 2, and 5), Foxl2 siRNA no. 1 (F1, lanes 3 and 6), or Foxl2 siRNA no. 2 (F2, lanes 4 and 7). Nuclear extracts were collected and subjected to Western blotting with HA and β-actin antibodies. C (left), LβT2 cells in 10-cm plates were transfected with 3 μg WT HA-FOXL2 (lanes 1 and 2) with control (lane 1) or Foxl2 siRNA no. 1 (lane 2). Nuclear extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis as in panel B. C (right), LβT2 cells were reverse transfected with control (lane 3) or Foxl2 siRNA no. 1 (lane 4) and then seeded in 10-cm plates. After 3 d, nuclear extracts were collected and subjected to Western blotting with a FOXL2-specific antibody. D, Cells were transfected as in panel A with a porcine reporter and control or Foxl2 siRNA no. 1. Cells were cotransfected with 0.15 ng/well pcDNA3 (−) or siRNA no. 1-resistant FOXL2 (+). The following day, cells were treated with activin A overnight. In panels A and D, all treatments were performed in triplicate, and the experiments were repeated three times. Cont., Control.

To confirm the specificity of the siRNAs, we performed a series of validation experiments using siRNA no. 1. First, we examined the effects of the siRNA on FOXL2 protein expression. Under our assay conditions, transfection efficiency of LβT2 cells is insufficient to obtain an accurate measure of the extent of RNAi-induced knockdown of mRNA/protein expression on a per cell basis (22). Therefore, to validate the siRNAs, we overexpressed HA-FOXL2 in CHO cells in the presence or absence of the Foxl2 siRNAs nos. 1 and 2 (F1 and F2 in Fig. 6B). Both siRNAs potently inhibited WT FOXL2 protein expression (Fig. 6B; compare lanes 2–4). To show specificity of the effect, we created a FOXL2 expression vector with a mutation rendering its mRNA product resistant to siRNA no. 1, while remaining sensitive to siRNA no. 2. The mutation changed the nucleotide, but not protein, sequence. The resistant (Res.) FOXL2 was expressed to comparable levels as WT (Fig. 6B, lanes 2 and 5); however, its expression was inhibited by siRNA no. 2 (lane 7), but not siRNA no. 1 (lane 6), confirming the specificity of the siRNAs for their target sequences. When transfected into homologous LβT2 cells, HA-FOXL2 was efficiently depleted by siRNA no. 1 (Fig. 6C, compare lanes 1 and 2). These data showed that siRNA no. 1 also worked efficiently in LβT2 cells to inhibit exogenous FOXL2 expression. Using a reverse transfection protocol, which improves transfection efficiency in LβT2 cells (38), we detected depletion of endogenous FOXL2 protein by siRNA no. 1 (Fig. 6C, lanes 3 and 4).

Next, we cotransfected LβT2 cells with the −326/+8 pFshb-luc reporter in the presence and absence of Foxl2 siRNA no. 1 and again observed significant antagonism of the activin A response (Fig. 6D). Here, however, we almost completely rescued activin A-stimulated reporter activity by cotransfecting the FOXL2 siRNA-resistant (Fig. 6D) but not the WT FOXL2 expression construct (data not shown). In contrast, the inhibitory effect of Foxl2 siRNA no. 2, which targets a distinct sequence, could not be rescued by either the FOXL2 siRNA-resistant or WT constructs (data not shown). Collectively, these data confirmed that the effects of the siRNAs were specific to their depletion of endogenous FOXL2 expression.

Finally, to demonstrate that the effect of FOXL2 knockdown was specific to activin A-regulated Fshb and did not reflect general inhibitory actions within the LβT2 cells, we examined the effects of the Foxl2 siRNAs on a FOXL2-independent response. In preliminary analyses, we observed that the T-165C mutation in the porcine promoter did not alter induction by GNRH1 (data not shown), suggesting that FOXL2 is not required for the actions of GNRH1 on this promoter. Indeed, neither of the Foxl2 siRNAs significantly impaired GNRH1-stimulated porcine (supplemental Fig. S5C) or murine Fshb reporter activity (data not shown). Collectively, these data showed that FOXL2 is a necessary and specific regulator of activin A-regulated Fshb transcription.

A role for FOXL2 in activin A induction of murine Fshb transcription

Because the defined FOXL2 binding site is restricted to the porcine Fshb promoter, we asked whether the mechanism we delineated was specific to this species. We therefore turned our attention back to the murine Fshb promoter. Knockdown of FOXL2 with siRNA no. 1 significantly impaired activin A induction of a murine Fshb reporter (supplemental Fig. S6A), although not as completely as observed with the porcine promoter. Nonetheless, these data suggested a role for the protein in activin A regulation of both the porcine and murine Fshb promoters. Moreover, the effect on the murine promoter provided a rationale for examining the effects of FOXL2 depletion on activin A induction of the endogenous murine Fshb gene in LβT2 cells.

As we articulated previously (22), the low transfection efficiency of LβT2 cells makes it difficult to assess the effects of RNAi-mediated knockdown (which occurs in some cells) on activin A-stimulated Fshb mRNA expression (which occurs in all or most cells). To circumvent this confound, we used ALK4TD as a surrogate for activin A, allowing us to assess the effects of activin-like signaling and RNAi-mediated knockdown in cotransfected cells. ALK4TD-stimulated murine Fshb promoter activity was suppressed by cotransfection of Foxl2 siRNA no. 1 (Fig. 7A). A similar effect was observed with ALK4TD-stimulated porcine Fshb-luc activity (data not shown). ALK4TD also stimulated increases in endogenous Fshb mRNA levels (Fig. 7B), as reported previously (22,39). Here too the Foxl2 siRNA significantly inhibited the response (Fig. 7B). Importantly, the siRNA did not inhibit expression of the transfected receptor (supplemental Fig. S6B). Collectively, these data showed that FOXL2 is also required for activin A/ALK4 induction of the murine Fshb gene.

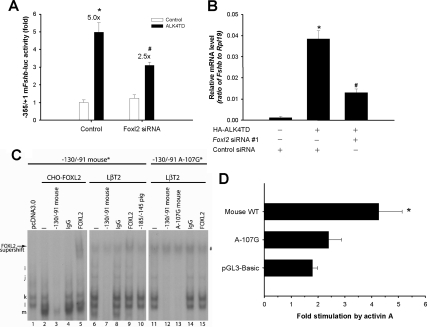

Figure 7.

A, LβT2 cells were cotransfected with 450 ng/well of murine −355/+1 Fshb-luc reporters and 5 nm control or Foxl2 siRNA no. 1 along with 100 ng/well pcDNA3 (empty vector) or ALK4TD. B, LβT2 cells cultured in six-well plates were cotransfected with 300 ng pcDNA3 or HA-ALK4TD and 5 nm control or Foxl2 siRNA no. 1. RNA was collected and subjected to quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Fshb mRNA levels. Treatments were performed in duplicate. C, Gel-shift analyses with radiolabeled murine −131/−91 WT probe and nuclear extracts from CHO cells transfected with pcDNA3 (lane 1) or HA-FOXL2 (lanes 2–5), or from LβT2 cells (lanes 6–10). Lanes 11–15 represent gel shifts with a radiolabeled A-107G mutant murine probe and LβT2 cells extracts. Complexes are labeled at the left; the arrow indicates supershifted complex m and # denotes a nonspecific band in LβT2 extracts. D, LβT2 cells were transfected with WT or A-107G mutant murine −355/+1 Fshb-luc reporters or empty reporter vector (pGL3-Basic) and treated overnight with activin A as in Fig. 3C. In panels A and D, all treatments were performed in triplicate, and the experiments were repeated three times.

A second, conserved, FOXL2 binding site resides in the proximal Fshb/FSHB promoter

A comparison of the murine and porcine promoters (Fig. 1) revealed a 2-bp mismatch between the two species within the core FOXL2 binding site in pig (Fig. 4C). The base pairs at −165/−164 in pig are TG, and the corresponding base pairs in mouse, −153/−152, are CA. We therefore predicted that FOXL2 effects on the murine gene were not likely to be mediated via the same genetic element. In fact, we observed that both base pairs in mouse needed to be changed to those observed in pig to confer strong binding of FOXL2 from LβT2 cells in gel-shift analyses (compare lanes 1, 2, and 14 in supplemental Fig. S7A). Interestingly, the same base pair substitutions significantly enhanced activin A induction of a murine Fshb reporter relative to WT (supplemental Fig. S7B). Collectively, these data suggested that FOXL2 likely acted elsewhere in the WT murine Fshb promoter.

We performed an in silico analysis of the murine promoter and identified a candidate forkhead binding element, 5′-TAAACA-3′, more proximally on the negative strand (−112/−107), which is conserved in pig and human. This sequence was an exact match to the reverse complement of the core FOXL2 binding site identified in the porcine promoter (5′-TGTTTA-3′; Fig. 4C). A radiolabeled −130/−91 murine probe, containing this putative cis-element, was incubated with nuclear extracts from CHO cells transfected with empty vector (Fig. 7C, lane 1) or murine FOXL2 (lanes 2–5). Control extracts formed two distinct complexes (lane 1, labeled “k” and “l”). An additional complex was detected when the probe was incubated with extracts containing FOXL2 (lane 2, labeled “m”). All the complexes were specific and could be competed completely by 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled homologous probe (lane 3). Complex m was supershifted in the presence of a FOXL2 antibody (lane 5) but not by IgG (lane 4). A nearly identical banding pattern was observed with LβT2 cell extracts (lane 6). Importantly, complex m was similarly displaced by the FOXL2 antibody (lane 9) and was competed by the porcine probe (−185/−145) containing the strong FOXL2 binding site (lane 10).

The above analysis showed that T-165 in the porcine promoter was critical for strong FOXL2 binding. This base pair corresponds to A-107 in the proximal element in mouse. When we introduced the mutation A-107G (comparable to T-165C), binding of complex m, which contains FOXL2, was specifically inhibited (compare lanes 6 and 11). Introduction of the A-107G mutation into a murine Fshb reporter significantly decreased its activin A induction in LβT2 cells (Fig. 7D). Collectively, these data suggested that FOXL2 binds to the proximal murine Fshb promoter to mediate activin induction.

The proximal FOXL2 element also contributes to activin induction of the porcine Fshb promoter

The proximal FOXL2 binding site in the murine promoter (hereafter “proximal” element) is conserved in the porcine and human promoters, unlike the more distal and unique FOXL2 element present in pig (hereafter “distal element”). We therefore examined a potential role for the proximal element (−125/−119) in activin A regulation of the porcine promoter. Introduction of the mutation A-119G to a porcine Fshb reporter (equivalent to A-107G in mouse) attenuated activin A induction, although to a lesser extent than the T-165C mutation (Fig. 8A). We confirmed, by gel-shift analysis and DNAP, that FOXL2 from LβT2 cells bound the proximal element in pig and that this binding was disrupted by the A-119G mutation (Fig. 8B, lanes 3 and 4; also compare complex m in lanes 1 and 8 in supplemental Fig. S8A).

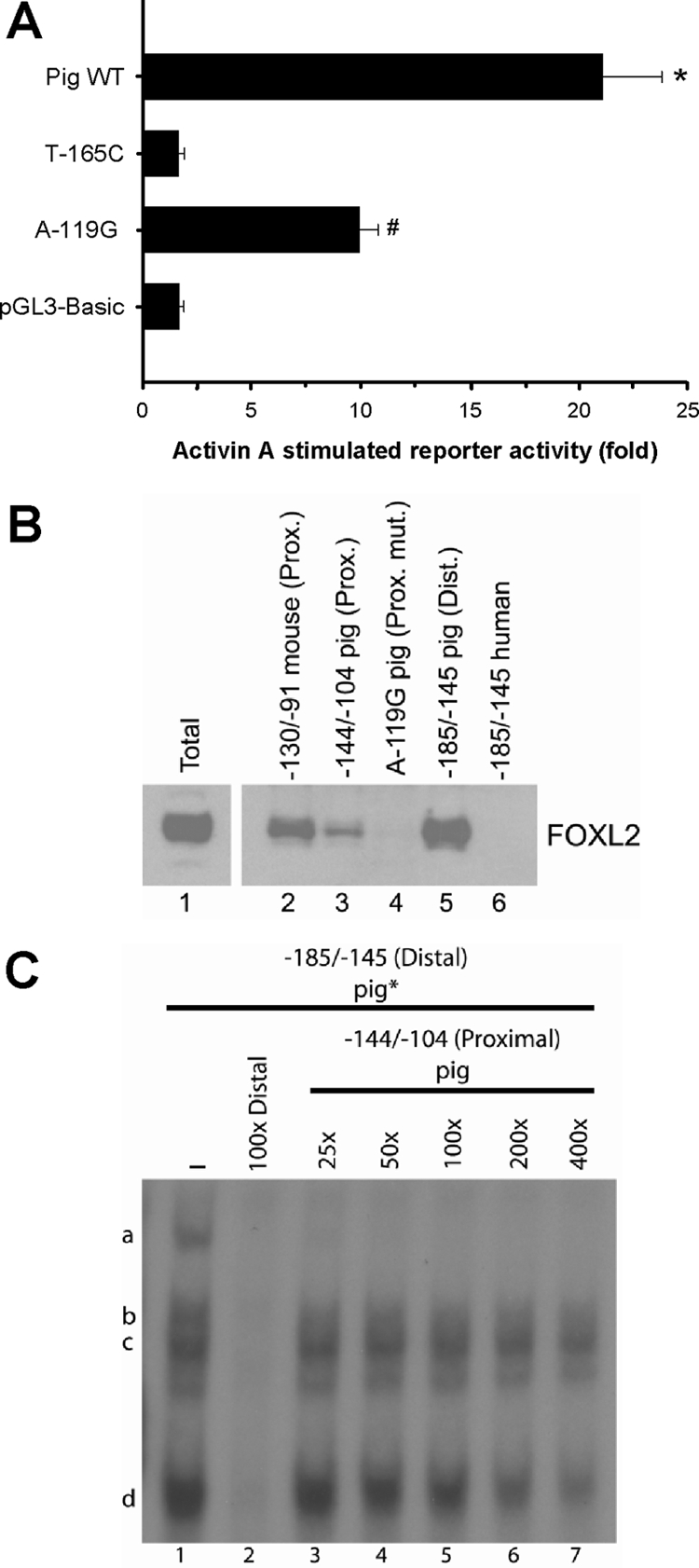

Figure 8.

A, LβT2 cells were transfected and treated as Fig. 3C with −326/+8 pFshb-luc or the indicated point mutants. B, Immunoblot was performed with the FOXL2 antibody on activin A-stimulated LβT2 whole-cell extracts (total; lane 1) as well as proteins eluted from the indicated biotinylated murine, porcine, or human probes. C, Gel-shift analyses were performed as in Fig. 3A with radiolabeled −185/−145 (distal) pig probe incubated with LβT2 nuclear extracts. Binding was competed using 100-fold homologous unlabeled probe (lane 2) or 25, 50, 100, 200, or 400-fold excess unlabeled −144/−104 pig (proximal) probe (lanes 3–7). Dist., Distal; Prox., proximal; Mut., mutant.

The sequence of the −144/−104 porcine probe used to demonstrate FOXL2 binding to the proximal element is perfectly conserved in human, suggesting the FOXL2 might also bind human FSHB. We therefore introduced the A-119G mutation in the context of the activin-responsive human C-165T FSHB reporter. The mutation significantly impaired activin A induction (supplemental Fig. S8B). Collectively, the data indicate that FOXL2 can bind the proximal Fshb/FSHB promoters of at least three species to regulate transcription.

Relative affinities of the proximal and distal FOXL2 binding sites

We noted that the distal element mutation (C-165T) was more disruptive to activin A induction of the porcine promoter than was the proximal site mutation (A-119G; Fig. 8A). We therefore questioned whether this might have derived from affinity differences between the two elements for FOXL2 binding. Consistent with this idea, DNAP experiments showed that the distal site precipitated more FOXL2 than the proximal site (Fig. 8B, lanes 3 and 5). To examine this more quantitatively, we performed gel-shift analyses with the radiolabeled distal probe (−185/−145) and examined the ability of unlabeled proximal probe (−144/−104) to displace FOXL2 (complex d) binding. Whereas 100-molar excess distal (homologous) probe completely displaced binding, considerably more proximal probe was required (Fig. 8C). Even at 400-fold excess, the proximal probe failed to completely displace FOXL2 binding to the distal probe (lane 7). In contrast, 100-fold excess porcine distal probe could completely displace FOXL2 binding to the murine proximal probe (Fig. 7C, lane 10). This is interesting in light of the fact that the proximal murine site seems to bind FOXL2 more strongly than the proximal porcine/human site (Fig. 8B; compare lanes 2 and 3). These data suggest that FOXL2 binds the different elements with the following order of affinity: distal pig more than proximal mouse more than proximal pig/human.

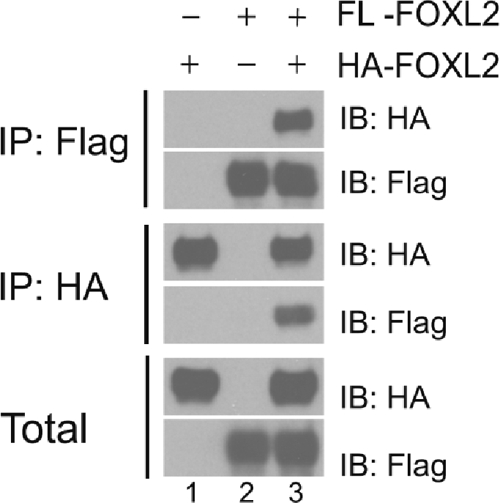

FOXL2 can self-associate in cells

Finally, given the enhanced activin A responsiveness of the porcine Fshb promoter relative to other species and the presence of two FOXL2 binding sites therein, we asked whether FOXL2 might regulate this gene through DNA-bound homodimers or higher order complexes. We therefore asked whether FOXL2 can self-associate. We cotransfected CHO cells with Flag- and HA-tagged versions of murine FOXL2. Coimmunoprecipitation, followed by Western blotting, showed that FOXL2 could form dimeric or higher order complexes with itself in living cells (Fig. 9, lane 3).

Figure 9.

CHO cells were transfected with HA-FOXL2 (lane 1), Flag-FOXL2 (lane 2), or the two in combination (lane 3). Whole-cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Flag or -HA agarose affinity gels. Precipitated proteins were eluted and run on SDS-PAGE (top four panels). Extracts before IP (Total, bottom two panels) were also included. Membranes were immunoblotted (IB) with HA or Flag antibodies.

Discussion

Activins are selective and potent regulators of Fshb subunit transcription and FSH secretion in several mammalian species. Using a comparative approach, we identified an important role for the forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 in activin A-induced porcine and murine Fshb promoter activities. We demonstrate that the porcine promoter contains two FOXL2 binding sites: a unique, high-affinity element and a more proximal, lower-affinity site, which is conserved across species (Fig. 1). The distal site is required for activin A induction of the porcine promoter, whereas the proximal site plays a less important (although still relevant) role in this species (Fig. 8A). In mouse, loss of the proximal site significantly diminishes activin A induction (Fig. 7D). Interestingly, the human promoter, which is largely insensitive to the direct effects of activins (40), contains the identical proximal FOXL2 element as pig. However, this site seems to bind FOXL2 more weakly than the proximal murine element (Fig. 8B). Moreover, the proximal site in pig is insufficient to support the activin A response, as evidenced by the T-165C (Fig. 3C) and −137/+8 (Fig. 2B) porcine reporters, both of which contain the proximal, but lack the distal, element. Thus, the importance of the different elements to the activin response may be related to their relative FOXL2 binding affinities (Fig. 8, B and C).

The determinants of this differential binding have not been established. A novel FOXL2 binding sequence was recently characterized using a random library/PCR-based screening method: [A/G)CCTTGAC (reverse complement of sequence in Ref. 41)]. The sites we identify here bear little resemblance to this element. Instead, we defined the distal FOXL2 element as TGTTTAnAnTA (Fig. 4C). The core of this element, TGTTTA, is perfectly conserved in the proximal site (on the opposite strand) in all three species. Importantly, our sequence matches the first 6 of 7 bp of the consensus forkhead binding element: T(G/A)TT(T/G)(A/G)(C/T) (reverse complement of sequence reported in Refs. 41 and 42). Our binding data (Fig. 4C) suggest that the base pair at position 7 (G in the distal element) is not critical for FOXL2 binding. In addition, the data clearly show roles for the base pairs at positions 8 (A), 10 (T), and 11 (A) in FOXL2 binding. In the proximal human/pig FOXL2 site, these base pairs (reverse complement for purposes of comparison) are A, A, and G. In mouse, they are A, G, and G. Therefore, both match the distal site at position 8, but not positions 10 or 11. This might help explain the stronger binding of FOXL2 to the distal porcine site. With respect to the differences in binding between the proximal sites from human/pig and mouse, the two differ at position 10. It is therefore possible, but not yet demonstrated, that the G in mouse is more favorable for FOXL2 binding than the A in the other two species.

Another possibility concerns the base pair at position 9, which is C in both the distal porcine and proximal murine element, but is T in the proximal human/pig element. First, this base pair may contribute weakly to binding (Fig. 4C, lane 17). Second, in the distal porcine site, it plays an important role in activin A induction (C-157A mutant in supplemental Fig. S2B). In the murine promoter, the base pair is G-115 (C on opposite strand), which is in the first position of a putative SBE. Although we and others have had difficulty in demonstrating endogenous Smad3 or 4 binding to this element, likely because of its low affinity for Smads (43), mutation of the two 3′-base pairs in this element (−113/−112) greatly diminishes both activin A and Smad3 induction of the murine promoter (31). There is precedent for FOXL2 and Smad3 binding to adjacent cis-elements in activin-responsive genes, Gnrhr and Fst (35,37). Indeed, we and others have observed a physical association between Smad3 and FOXL2 [Ref. 37 and Lamba, P., and D. J. Bernard, unpublished data). This not only provides a potential link between activin signaling and FOXL2, but may serve to stabilize the interaction of both proteins to their cis-elements (34). Because the putative SBE is present adjacent to the proximal FOXL2 site in the murine, but not human/pig, promoters, this could contribute to the relatively enhanced FOXL2 binding to the former. However, because the −113/−112 mutation reported earlier (31) would also be predicted to directly affect FOXL2 binding through perturbation of the base pair at −112, it remains unclear whether or not this GTCT element represents a true SBE in the murine promoter. Indeed, the mechanistic link between Smads and FOXL2 in the regulation of both the porcine and murine Fshb promoters needs to be more definitively established.

In summary, we have identified FOXL2 as a conserved player in activin A induction of Fshb transcription, although the mechanisms whereby the protein mediates its effects differ between species. The presence of two FOXL2 binding sites in the porcine Fshb promoter renders it particularly sensitive to the stimulatory effects of activins. Whether this involves direct interactions between two FOXL2 molecules (Fig. 9) concurrently bound to the two sites is currently unknown. Regardless, the unique means through which FOXL2 can interact with the porcine Fshb promoter may help explain how FSH levels remain elevated through most of the estrous cycle in this species, in the face of reduced inhibin levels (44). Similarly, the more proximal FOXL2 binding site in the rodent promoters may contribute to the activin-dependent secondary FSH surge observed on the morning of estrus in these animals. The human promoter contains a lower affinity proximal FOXL2 binding site than observed in mouse and lacks the high-affinity site in pig. These differences may contribute to the relative insensitivity of the human FSHB promoter to the direct actions of activins. Physiologically, this may serve to restrain increases in FSH levels at the end of the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle in the face of reduced inhibin A levels.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

DMEM with 4.5 g/liter glucose, l-glutamine, and sodium pyruvate was from (Multicell, Wisent Inc., St-Bruno, Quebec, Canada). Eagle’s MEM was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). DMEM/F-12 Ham’s media (1:1) with 2.5 mm l-glutamine, 15 mm HEPES was from HyClone Laboratories (South Logan, UT). Lipofectamine/Plus, Lipofectamine 2000, gentamycin, TRIzol, NuPAGE gels, SYBR green quantitative PCR master mix, and fetal bovine serum were purchased from Invitrogen (Burlington, Ontario, Canada). Human recombinant activin A was purchased from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN). The anti-FOXL2 (F0805), monoclonal anti-HA (H9658), M2 monoclonal (F3165), and polyclonal (F7425) anti-Flag antibodies, aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin, and phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, SB431542, GNRH1, EZview red anti-Flag M2 (F2426), and anti-HA (E6779) affinity gels and peptides (F4799 and I2149) were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Deoxynucleotide triphosphates, Taq polymerase, 5× Passive Lysis Buffer, T4 DNA ligase, T4 DNA polymerase, and restriction endonucleases were purchased from Promega Corp. (Madison, WI). Protease inhibitor tablets (Complete Mini) were purchased from Roche (Indianapolis, IN). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Homo-polymers polydeoxyinosinic acid and deoxycytidylic acid, ECL-plus reagent, and protein markers were purchased from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ). [γ-32P]ATP was from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA). Foxl2 and control siRNAs were from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO).

Constructs

The −1990/+1 mFshb-luc WT and SBE mutant, −1195/+1 mFshb-luc, −1028/+7 hFSHB WT and SBE+, −1369/+8 pFshb-luc, −1772/+38 mGnrhr-luc (from Colin Clay, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO) promoter reporters, Smad2 and Smad3 short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs), constitutively active HA-ALK4(T206D), and glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-Smad3MH1 and -Smad4MH1 expression constructs (from Bert Vogelstein, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) were described previously (22,24,28,45). The murine HA-FOXL2 expression vector was also a gift from C. Clay (Colorado State University) (35). Flag-FOXL2 was generated from the HA-FOXL2 vector by PCR using the primers in supplemental Table S1 and methods described previously (46).

The −767/+8 and −399/+8 pFshb-luc reporters were created by first digesting the −1369/+8 pFshb-luc reporter (28) with SacI to remove promoter sequences between −1369 to −768, and the remaining construct was religated to construct −767/+8 pFshb-luc. Next, the −767/+8 reporter was digested with SacI and blunted with T4 DNA polymerase, followed by digestion with PvuI. The reaction was run on an agarose gel, and the larger of two fragments was gel purified and self-ligated to generate −399/+8 pFshb-luc. The remaining 5′-deletions of the porcine promoter (−326/+8, −252/+8, −177/+8) were made by PCR with −399/+8 pFshb-luc as template. Appropriate forward primers (all of which contained MluI sites at their 5′-ends) were used with the same reverse primer, −17/+8 pFshb.R (which contained an XhoI site) (see supplemental Table S1 for primer sequences). The amplicons were digested with MluI and XhoI and ligated into the same sites in pGL3-Basic. To make the −137/+8 pFshb-luc reporter, a novel Sac1 site was introduced at −140/−135 (GATCTC→GAGCTC) of −767/+8 pFshb-luc using the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene), and the resulting DNA was digested with SacI, which dropped an insert from upstream of −767 (in the multiple cloning site) to the equivalent of −138 in the promoter. The remaining vector was religated to produce the −137/+8 reporter.

Human −329/+7 FSHB-luc was constructed by PCR using the −486/+7 hFSHB-luc reporter (described in Ref. 46) as template using the −329/−309.hFSHB.F and −21/+7.hFSHB.R primers in supplemental Table S1. The resulting PCR product was digested with MluI/XhoI and ligated into the same sites in pGL3-Basic.

All of the mutant reporters and siRNA-resistant vectors were generated using the QuikChange protocol and the primers in supplemental Table S1. The sequences of all constructs were verified (Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ).

Cell culture, transfections, and reporter assays

LβT2 and αT3-1 cells (gift from Dr. P. Mellon, University of California, San Diego) and HepG2 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultured as described previously (40,45). CHO cells (gift from Dr. P. Morris, Population Council, New York, NY) were cultured in DMEM/F12 1:1/10% fetal bovine serum. For reporter assays, the LβT2 cells were plated in 24-well plates at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells per well 3 d before transfection. αT3-1 cells were plated at similar density to LβT2 cells a day before transfection. CHO and HepG2 cells were plated in 24-well plates at a density of 3.5–5 × 104 cells per well 2 d before transfection. Cells were transfected overnight with Lipofectamine 2000 with the reporter and expression plasmids/siRNAs at the indicated concentrations. Total DNA transfected was balanced across conditions. Cells were treated with activin A, and lysates were assayed for luciferase activity as described previously (40,46). All experiments were performed a minimum of two to five times, with different preparations of the constructs, and all treatments were performed in duplicate or triplicate. In the experiments in which the activin induction of the different reporter constructs was compared, we report only the fold activin response and not basal reporter activities. In our experience, the latter can vary sufficiently between DNA preparations so as to obscure quantitatively meaningful comparisons. In the experiments in which different treatments were performed with the same reporter (e.g. shRNA/siRNA and overexpression of FOXL2), the effects on both basal and activin-induced reporter activity are reported. To assess knockdown of endogenous FOXL2 in LβT2 cells, cells were transfected with the Foxl2 siRNA no. 1 using a reverse transfection protocol as described earlier (46).

EMSA and DNA affinity pull-down assay

LβT2 cells were grown in 10-cm plates for gel shift and DNA affinity pull-down assays and stimulated or not with 1 nm activin A for 1 h before collection of nuclear or whole-cell lysates. Nuclear extracts were prepared and gel shifts were performed as described previously (24,46). Briefly, each binding reaction was composed of 50 mm KCl, 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.2), 5 mm dithiothreitol, 20% glycerol, 1 μg of polydeoxyinosinic deoxycytidylic acid, 5–6 μg nuclear extract in a final volume of 20 μl. The binding reaction was incubated with unlabeled competitor probes (100 or 500× molar concentration; see Figs. 3B and 4C for sequences) or antibody for 10 min at room temperature before the addition of 32P-labeled double-stranded probe (0.1 μm, final concentration). The reaction mix was incubated for 20 min at room temperature before loading on native polyacrylamide gels and running for 3 h at 4 C.

DNA affinity pull-down assays were performed as previously described (46) with whole-cell lysates from control or activin A-treated cells incubated with 50 pmol biotinylated double-stranded −185/−145 porcine Fshb or −185/−145 human FSHB probes (see supplemental Table S1) bound to streptavidin-coupled Dynabeads M-280 (Dynal; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After washes, bound proteins were eluted from the beads, separated on 7% NuPAGE Tris-Acetate mini gels, transferred to Protran nitrocellulose (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH), and probed with FOXL2 antibody. The details of the immunoblot protocol have been described previously (22).

Reverse transcription and quantitative real-time PCR

LβT2 cells were grown in six-well plates and transfected for 6 h with control siRNA alone, control siRNA with ALK4TD, or Foxl2 siRNA no. 1 and ALK4TD using Lipofectamine (n = 2 per treatment). The experiment was performed simultaneously in two plates so that samples could be collected for RNA and protein analyses. After 72 h in growth media, protein lysates were collected in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors or RNA extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) as described previously (22). The reverse transcription followed by real-time quantitative PCR was performed as described previously (45,46) in triplicate using SYBR green quantitative PCR master mix and the primers in supplemental Table S1. Quantification was performed by calculating ratio of the Fshb to Rpl19 mRNA, both determined using the relative standard curve method.

Coimmunoprecipitation assays

CHO cells grown in 10-cm dishes were transfected with HA-FOXL2 and/or Flag-FOXL2 either individually or together, and coimmunoprecipitation assays were performed as described elsewhere (46). Briefly, cells were harvested 24 h after transfection in cell lysis buffer (50 mm Tris HCl, pH 7.5; 150 mm NaCl; 1 mm EDTA; 1% Triton X-100). The lysates was divided in half after clarification and incubated with 40 μl gel volume of anti-Flag or anti-HA agarose affinity gels. After overnight incubation, the agarose beads were washed and proteins eluted using specific Flag or HA peptides as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Eluted proteins were collected and run on 7% NuPAGE Tris-acetate gels along with total proteins and probed with anti-Flag and anti-HA antibodies as described previously (22).

Statistics

All experiments were performed two to five times. The data presented are from representative experiments. Differences between means were compared using one-, two-, or three-way ANOVAs, followed by post hoc tests where appropriate (SYSTAT 10.2, Chicago, IL). In some experiments, data were log transformed when the variances were unequal between groups. In all the experiments, significance was assessed relative to P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Pamela Mellon (University of California San Diego) and P. Morris (Population Council) for the LβT2 and CHO cells, respectively. The murine HA-FOXL2 and human GST-Smad3MH1 and GST-Smad4MH1 expression vectors were generous gifts from Drs. Colin Clay (Colorado State University) and Bert Vogelstein (The Johns Hopkins University). We thank Dr. Bill Miller and Jesse Gore (North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC) for their review of an earlier version of the manuscript. Vishal Khivansara and Michelle Santos provided expert technical assistance during the initial phases of the study.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes for Health Research Grant MOP-89991 and National Institutes of Health R01 Grant HD47794 (to D.J.B.). S.T. holds a doctoral fellowship from the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec (FRSQ). D.J.B. is a Chercheur-boursier of FRSQ.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online March 26, 2009

Abbreviations: ALK4, Activin receptor-like kinase 4; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; DNAP, DNA affinity pull-down; FOX, forkhead box; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; HA, hemagglutinin; RNAi, RNA interference; SBE, Smad-binding element; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; siRNA, short interfering RNA; Smad, Sma- and Mad-related protein; WT, wild type.

References

- Kumar TR, Wang Y, Lu N, Matzuk MM 1997 Follicle stimulating hormone is required for ovarian follicle maturation but not male fertility. Nat Genet 15:201–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layman LC, Lee EJ, Peak DB, Namnoum AB, Vu KV, van Lingen BL, Gray MR, McDonough PG, Reindollar RH, Jameson JL 1997 Delayed puberty and hypogonadism caused by mutations in the follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit gene. N Engl J Med 337:607–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layman LC, Porto AL, Xie J, da Motta LA, da Motta LD, Weiser W, Sluss PM 2002 FSH β gene mutations in a female with partial breast development and a male sibling with normal puberty and azoospermia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:3702–3707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews CH, Borgato S, Beck-Peccoz P, Adams M, Tone Y, Gambino G, Casagrande S, Tedeschini G, Benedetti A, Chatterjee VK 1993 Primary amenorrhoea and infertility due to a mutation in the β-subunit of follicle-stimulating hormone. Nat Genet 5:83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aittomäki K, Lucena JL, Pakarinen P, Sistonen P, Tapanainen J, Gromoll J, Kaskikari R, Sankila EM, Lehväslaiho H, Engel AR, Nieschlag E, Huhtaniemi I, de la Chapelle A 1995 Mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene causes hereditary hypergonadotropic ovarian failure. Cell 82:959–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel MH, Wootton AN, Wilkins V, Huhtaniemi I, Knight PG, Charlton HM 2000 The effect of a null mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene on mouse reproduction. Endocrinology 141:1795–1803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierich A, Sairam MR, Monaco L, Fimia GM, Gansmuller A, LeMeur M, Sassone-Corsi P 1998 Impairing follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) signaling in vivo: targeted disruption of the FSH receptor leads to aberrant gametogenesis and hormonal imbalance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:13612–13617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoak DC, Schwartz NB 1980 Blockade of recruitment of ovarian follicles by suppression of the secondary surge of follicle-stimulating hormone with porcine follicular field. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 77:4953–4956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling N, Ying SY, Ueno N, Esch F, Denoroy L, Guillemin R 1985 Isolation and partial characterization of a Mr 32,000 protein with inhibin activity from porcine follicular fluid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82:7217–7221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivier J, Spiess J, McClintock R, Vaughan J, Vale W 1985 Purification and partial characterization of inhibin from porcine follicular fluid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 133:120–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson DM, Foulds LM, Leversha L, Morgan FJ, Hearn MT, Burger HG, Wettenhall RE, de Kretser DM 1985 Isolation of inhibin from bovine follicular fluid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 126:220–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling N, Ying SY, Ueno N, Shimasaki S, Esch F, Hotta M, Guillemin R 1986 Pituitary FSH is released by a heterodimer of the β-subunits from the two forms of inhibin. Nature 321:779–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale W, Rivier J, Vaughan J, McClintock R, Corrigan A, Woo W, Karr D, Spiess J 1986 Purification and characterization of an FSH releasing protein from porcine ovarian follicular fluid. Nature 321:776–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard DJ, Chapman SC, Woodruff TK 2001 Mechanisms of inhibin signal transduction. Recent Prog Horm Res 56:417–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilezikjian LM, Blount AL, Donaldson CJ, Vale WW 2006 Pituitary actions of ligands of the TGF-β family: activins and inhibins. Reproduction 132:207–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison CA, Gray PC, Vale WW, Robertson DM 2005 Antagonists of activin signaling: mechanisms and potential biological applications. Trends Endocrinol Metab 16:73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe Y, Minegishi T, Leung PC 2004 Activin receptor signaling. Growth Factors 22:105–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier JF, Findlay JK 2001 Roles of activin and its signal transduction mechanisms in reproductive tissues. Reproduction 121:667–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun JJ, Vale WW 1997 Activin and inhibin have antagonistic effects on ligand-dependent heteromerization of the type I and type II activin receptors and human erythroid differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 17:1682–1691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis KA, Gray PC, Blount AL, MacConell LA, Wiater E, Bilezikjian LM, Vale W 2000 Betaglycan binds inhibin and can mediate functional antagonism of activin signalling. Nature 404:411–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont J, McNeilly J, Vaiman A, Canepa S, Combarnous Y, Taragnat C 2003 Activin signaling pathways in ovine pituitary and LβT2 gonadotrope cells. Biol Reprod 68:1877–1887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard DJ 2004 Both SMAD2 and SMAD3 mediate activin-stimulated expression of the follicle-stimulating hormone β subunit in mouse gonadotrope cells. Mol Endocrinol 18:606–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suszko MI, Balkin DM, Chen Y, Woodruff TK 2005 Smad3 mediates activin-induced transcription of follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit gene. Mol Endocrinol 19:1849–1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamba P, Santos MM, Philips DP, Bernard DJ 2006 Acute regulation of murine follicle-stimulating hormone β subunit transcription by activin A. J Mol Endocrinol 36:201–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory SJ, Lacza CT, Detz AA, Xu S, Petrillo LA, Kaiser UB 2005 Synergy between activin A and gonadotropin-releasing hormone in transcriptional activation of the rat follicle-stimulating hormone-β gene. Mol Endocrinol 19:237–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suszko MI, Lo DJ, Suh H, Camper SA, Woodruff TK 2003 Regulation of the rat follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit promoter by activin. Mol Endocrinol 17:318–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messinis IE 2006 Ovarian feedback, mechanism of action and possible clinical implications. Hum Reprod Update 12:557–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KB, Khivansara V, Santos MM, Lamba P, Yuen T, Sealfon SC, Bernard DJ 2007 Bone morphogenetic protein 2 and activin A synergistically stimulate follicle-stimulating hormone β subunit transcription. J Mol Endocrinol 38:315–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West BE, Parker GE, Savage JJ, Kiratipranon P, Toomey KS, Beach LR, Colvin SC, Sloop KW, Rhodes SJ 2004 Regulation of the follicle-stimulating hormone β gene by the LHX3 LIM-homeodomain transcription factor. Endocrinology 145:4866–4879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JS, Rave-Harel N, McGillivray SM, Coss D, Mellon PL 2004 Activin regulation of the follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit gene involves Smads and the TALE homeodomain proteins Pbx1 and Prep1. Mol Endocrinol 18:1158–1170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGillivray SM, Thackray VG, Coss D, Mellon PL 2007 Activin and glucocorticoids synergistically activate follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit gene expression in the immortalized LβT2 gonadotrope cell line. Endocrinology 148:762–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelin A, Wasserman WW, Lenhard B 2004 ConSite: web-based prediction of regulatory elements using cross-species comparison. Nucl Acids Res 32:W249–W252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attisano L, Silvestri C, Izzi L, Labbé E 2001 The transcriptional role of Smads and FAST (FoxH1) in TGFβ and activin signalling. Mol Cell Endocrinol 180:3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Weisberg E, Fridmacher V, Watanabe M, Naco G, Whitman M 1997 Smad4 and FAST-1 in the assembly of activin-responsive factor. Nature 389:85–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth BS, Burns AT, Escudero KW, Duval DL, Nelson SE, Clay CM 2003 The gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor activating sequence (GRAS) is a composite regulatory element that interacts with multiple classes of transcription factors including Smads, AP-1 and a forkhead DNA binding protein. Mol Cell Endocrinol 206:93–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth BS, Egashira N, Haller JL, Butts DL, Cocquet J, Clay CM, Osamura RY, Camper SA 2006 FOXL2 in the pituitary: molecular, genetic, and developmental analysis. Mol Endocrinol 20:2796–2805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount AL, Schmidt K, Justice NJ, Vale WW, Fischer WH, Bilezikjian LM 2009 Foxl2 and Smad3 coordinately regulate follistatin gene transcription. J Biol Chem 284:7631–7645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury TB, Binder AK, Grammer JC, Nilson JH 2007 Maximal activity of the luteinizing hormone β-subunit gene requires β-catenin. Mol Endocrinol 21:963–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard DJ, Lee KB, Santos MM 2006 Activin B can signal through both ALK4 and ALK7 in gonadotrope cells. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 4:52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Fortin J, Lamba P, Bonomi M, Persani L, Roberson MS, Bernard DJ 2008 AP-1 and Smad proteins synergistically regulate human follicle-stimulating hormone β promoter activity. Endocrinology 149:5577–5591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benayoun BA, Caburet S, Dipietromaria A, Bailly-Bechet M, Batista F, Fellous M, Vaiman D, Veitia RA 2008 The identification and characterization of a FOXL2 response element provides insights into the pathogenesis of mutant alleles. Hum Mol Genet 17:3118–3127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrou S, Hellqvist M, Samuelsson L, Enerbäck S, Carlsson P 1994 Cloning and characterization of seven human forkhead proteins: binding site specificity and DNA bending. EMBO J 13:5002–5012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Wang YF, Jayaraman L, Yang H, Massagué J, Pavletich NP 1998 Crystal structure of a Smad MH1 domain bound to DNA: insights on DNA binding in TGF-β signaling. Cell 94:585–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox RV, Vatzias G, Naber CH, Zimmerman DR 2003 Plasma gonadotropins and ovarian hormones during the estrous cycle in high compared to low ovulation rate gilts. J Anim Sci 81:249–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamba P, Hjalt TA, Bernard DJ 2008 Novel forms of Paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 2 (PITX2): generation by alternative translation initiation and mRNA splicing. BMC Mol Biol 9:31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamba P, Khivansara V, D'Alessio AC, Santos MM, Bernard DJ 2008 Paired-like homeodomain transcription factors 1 and 2 regulate follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit transcription through a conserved cis-element. Endocrinology 149:3095–3108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.