Abstract

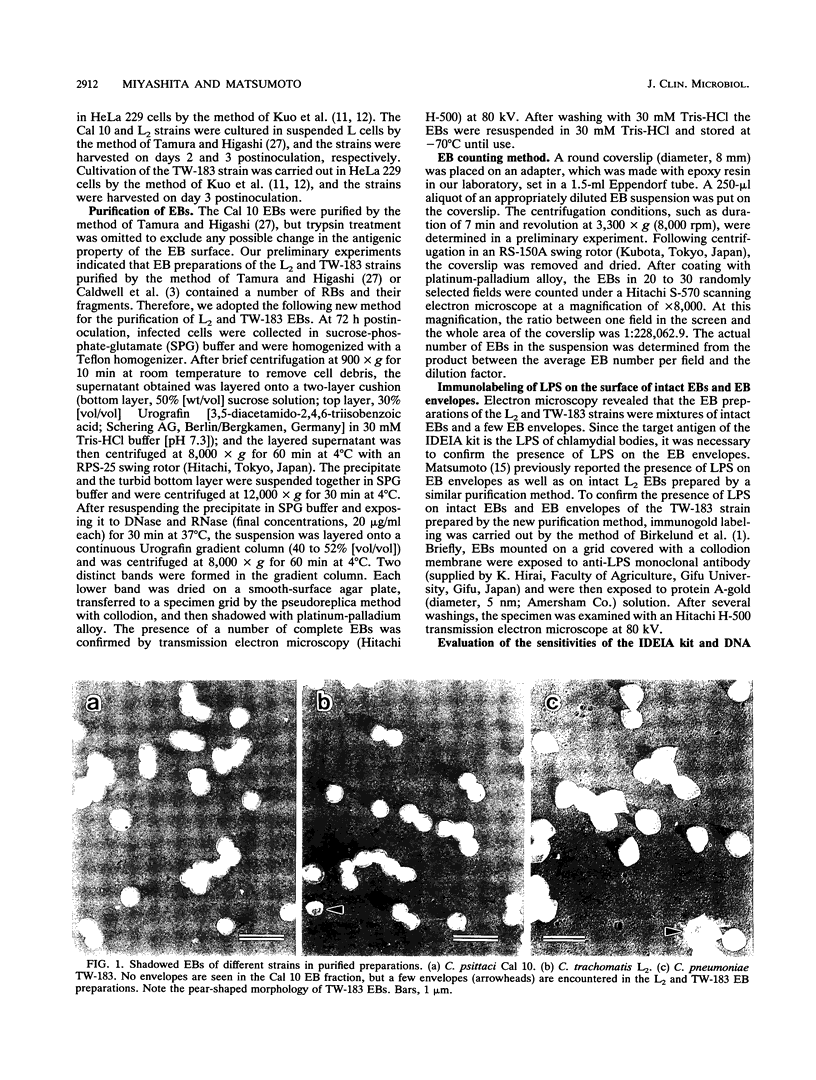

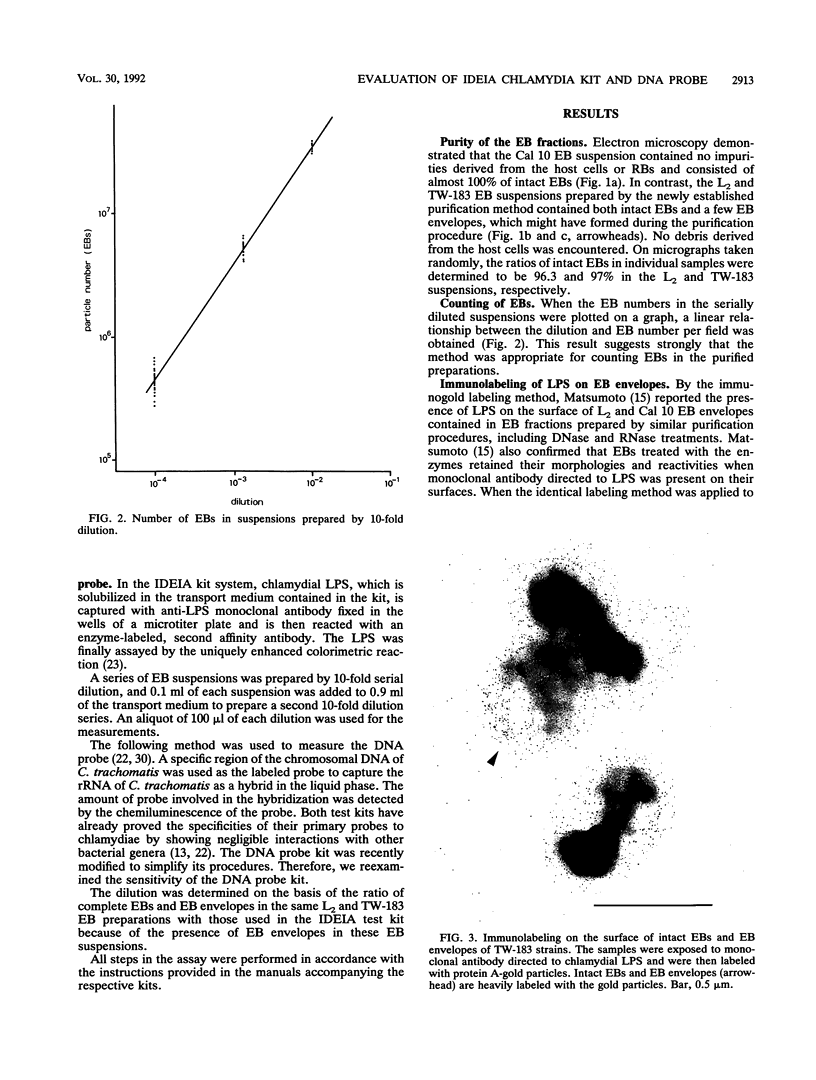

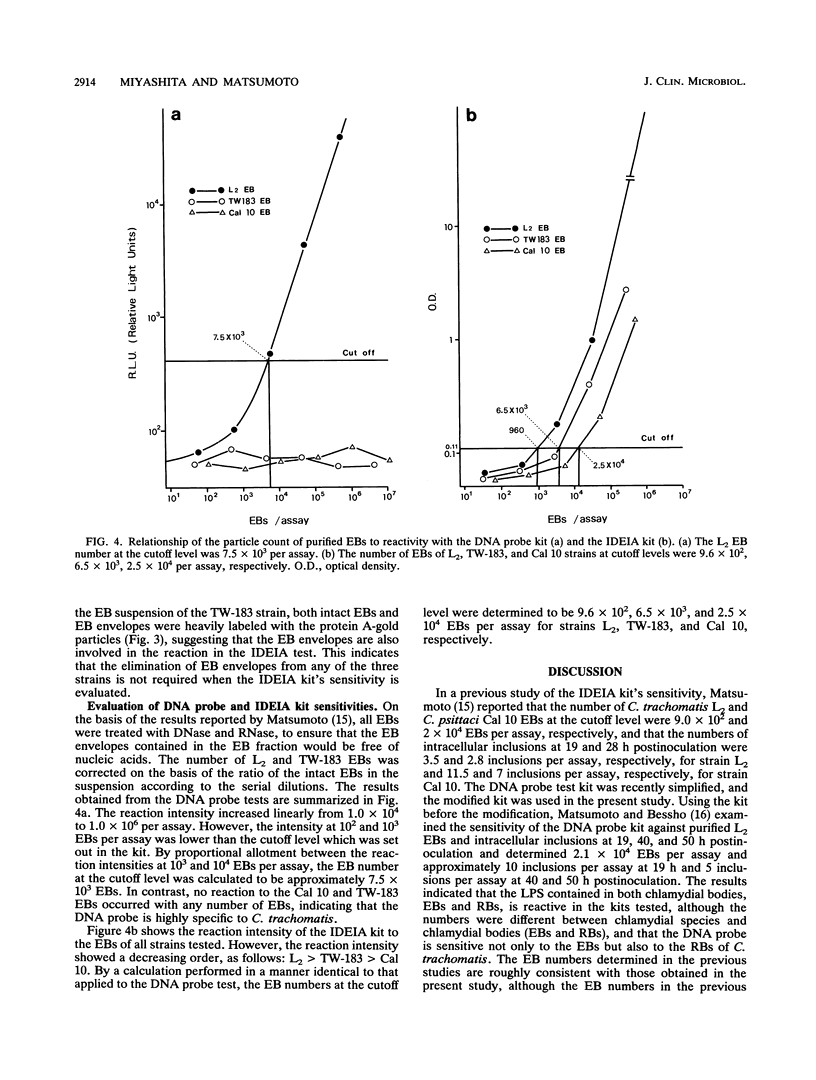

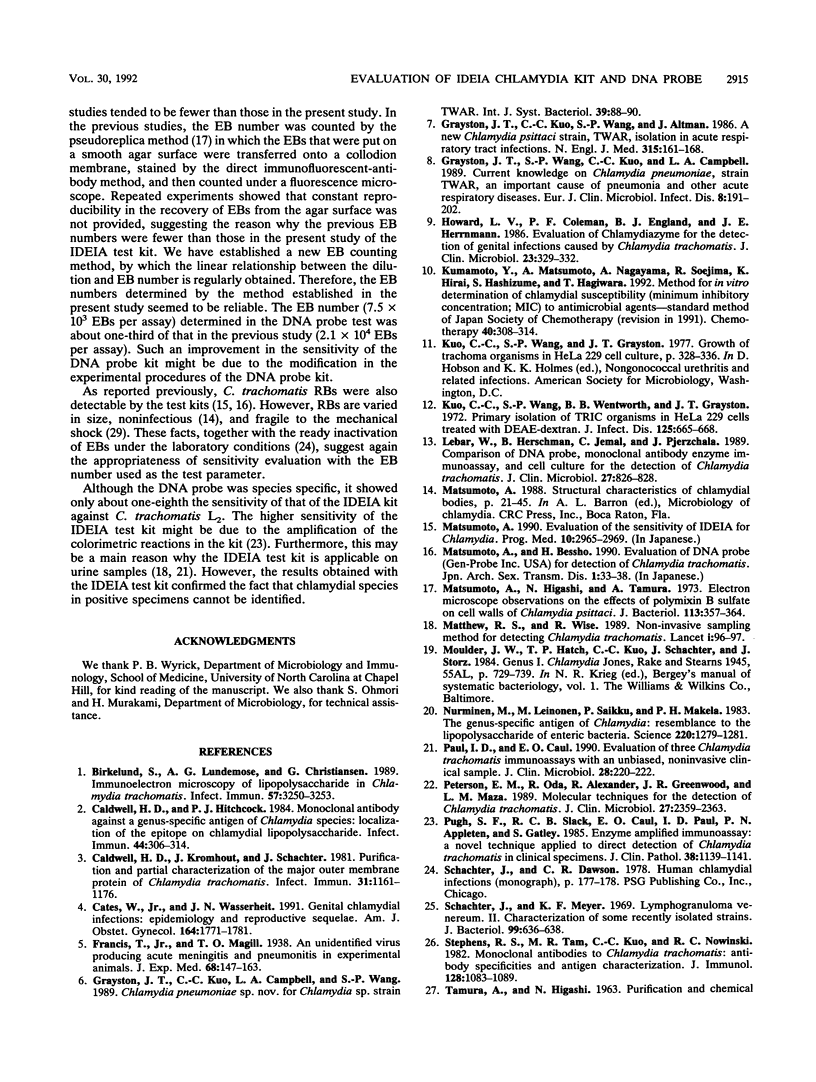

To evaluate the sensitivity of commercially available test kits for detection of chlamydiae, we established a method of purifying Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia pneumoniae elementary bodies (EBs). We then subjected the purified EBs, together with the purified EBs of Chlamydia psittaci, to the IDEIA Chlamydia (IDEIA) and DNA probe test kits to determine the EB numbers at the detection limits. The sensitivities of the test kits were thus compared. The results can be summarized as follows. (i) Intact EBs in the purified preparations were present at 100, 96.3, and 97% for the C. psittaci Cal 10, C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu (L2), and C. pneumoniae TW-183 strains, respectively. The preparations of the L2 and TW-183 EBs contained a few EB envelopes, which reacted with antilipopolysaccharide monoclonal antibodies, as did the intact EBs, indicating that elimination of EB envelopes is not required for testing of the IDEIA kit's sensitivity. (ii) We established a method of counting intact EBs and EB envelopes under a scanning electron microscope after sedimentation of EBs on a coverslip by centrifugation. (iii) The EB numbers per assay at the cutoff level, which is set up in the IDEIA kit, were 9.6 x 10(2), 6.5 x 10(3), and 2.5 x 10(4) for the L2, TW-183, and Cal 10 strains, respectively. When the same EB preparations were applied to the DNA probe kit, the EB number at the cutoff level was 7.5 x 10(3) per assay for the L2 strain, but no reaction occurred for the Cal 10 and TW-183 strains at any EB number, indicating that the DNA probe kit is highly specific for C. trachomatis. Although the IDEIA kit designed for detection of C. trachomatis showed a sensitivity superior to that of the DNA probe, the chlamydial species was not determined by the IDEIA kit.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Birkelund S., Lundemose A. G., Christiansen G. Immunoelectron microscopy of lipopolysaccharide in Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1989 Oct;57(10):3250–3253. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.10.3250-3253.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell H. D., Hitchcock P. J. Monoclonal antibody against a genus-specific antigen of Chlamydia species: location of the epitope on chlamydial lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1984 May;44(2):306–314. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.2.306-314.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell H. D., Kromhout J., Schachter J. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1981 Mar;31(3):1161–1176. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.3.1161-1176.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cates W., Jr, Wasserheit J. N. Genital chlamydial infections: epidemiology and reproductive sequelae. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991 Jun;164(6 Pt 2):1771–1781. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90559-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayston J. T., Kuo C. C., Wang S. P., Altman J. A new Chlamydia psittaci strain, TWAR, isolated in acute respiratory tract infections. N Engl J Med. 1986 Jul 17;315(3):161–168. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198607173150305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayston J. T., Wang S. P., Kuo C. C., Campbell L. A. Current knowledge on Chlamydia pneumoniae, strain TWAR, an important cause of pneumonia and other acute respiratory diseases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989 Mar;8(3):191–202. doi: 10.1007/BF01965260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard L. V., Coleman P. F., England B. J., Herrmann J. E. Evaluation of chlamydiazyme for the detection of genital infections caused by Chlamydia trachomatis. J Clin Microbiol. 1986 Feb;23(2):329–332. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.2.329-332.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C., Wang S., Wentworth B. B., Grayston J. T. Primary isolation of TRIC organisms in HeLa 229 cells treated with DEAE-dextran. J Infect Dis. 1972 Jun;125(6):665–668. doi: 10.1093/infdis/125.6.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBar W., Herschman B., Jemal C., Pierzchala J. Comparison of DNA probe, monoclonal antibody enzyme immunoassay, and cell culture for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Clin Microbiol. 1989 May;27(5):826–828. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.5.826-828.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto A., Higashi N., Tamura A. Electron microscope observations on the effects of polymixin B sulfate on cell walls of Chlamydia psittaci. J Bacteriol. 1973 Jan;113(1):357–364. doi: 10.1128/jb.113.1.357-364.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurminen M., Leinonen M., Saikku P., Mäkelä P. H. The genus-specific antigen of Chlamydia: resemblance to the lipopolysaccharide of enteric bacteria. Science. 1983 Jun 17;220(4603):1279–1281. doi: 10.1126/science.6344216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul I. D., Caul E. O. Evaluation of three Chlamydia trachomatis immunoassays with an unbiased, noninvasive clinical sample. J Clin Microbiol. 1990 Feb;28(2):220–222. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.2.220-222.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson E. M., Oda R., Alexander R., Greenwood J. R., de la Maza L. M. Molecular techniques for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Clin Microbiol. 1989 Oct;27(10):2359–2363. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.10.2359-2363.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh S. F., Slack R. C., Caul E. O., Paul I. D., Appleton P. N., Gatley S. Enzyme amplified immunoassay: a novel technique applied to direct detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in clinical specimens. J Clin Pathol. 1985 Oct;38(10):1139–1141. doi: 10.1136/jcp.38.10.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter J., Meyer K. F. Lymphogranuloma venereum. II. Characterization of some recently isolated strains. J Bacteriol. 1969 Sep;99(3):636–638. doi: 10.1128/jb.99.3.636-638.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens R. S., Tam M. R., Kuo C. C., Nowinski R. C. Monoclonal antibodies to Chlamydia trachomatis: antibody specificities and antigen characterization. J Immunol. 1982 Mar;128(3):1083–1089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAMURA A., HIGASHI N. PURIFICATION AND CHEMICAL COMPOSITION OF MENINGOPNEUMONITIS VIRUS. Virology. 1963 Aug;20:596–604. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(63)90284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAMURA A., IWANAGA M. RNA SYNTHESIS IN CELLS INFECTED WITH THE MENINGOPNEUMONITIS AGENT. J Mol Biol. 1965 Jan;11:97–108. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura A., Matsumoto A., Higashi N. Purification and chemical composition of reticulate bodies of the meningopneumonitis organisms. J Bacteriol. 1967 Jun;93(6):2003–2008. doi: 10.1128/jb.93.6.2003-2008.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods G. L., Young A., Scott J. C., Jr, Blair T. M., Johnson A. M. Evaluation of a nonisotopic probe for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in endocervical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990 Feb;28(2):370–372. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.2.370-372.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]