Abstract

Lab-on-a-chip systems offer a versatile environment in which low numbers of cells and molecules can be manipulated, captured, detected and analysed. We describe here a microfluidic device that allows the isolation, electroporation and lysis of single cells. A431 human epithelial carcinoma cells, expressing a green fluorescent protein-labelled actin, were trapped by dielectrophoresis within an integrated lab-on-a-chip device containing saw-tooth microelectrodes. Using these same trapping electrodes, on-chip electroporation was performed, resulting in cell lysis. Protein release was monitored by confocal fluorescence microscopy.

Keywords: lab-on-a-chip, single cell, proteomics

1. Introduction

Traditional cell studies carried out at the population level (105–107 cells) produce valuable information, but averaging the effects from cell-cycle-dependent states and inhomogeneous cellular responses contributes to difficulties in interpreting data. Adding to this, problems of detecting low-abundance proteins, due to signal swamping and non-specific protein loss in large sample volumes, have led scientists to try to advance our understanding of cellular behaviour using single-cell techniques. Already these methods have resulted in the development of a series of new technologies that enable single-cell handling, precision analysis and ultra-sensitive detection.

Lab-on-a-chip and microfluidics offer the prospect of providing integrated analytical and detection methods, with the technology providing a series of important advantages over bulk or large-scale analysis. For example, it is possible to analyse cells in low dead volumes (reducing sample dilution). Times taken for signals to diffuse from the cell to a microsensor, and indeed the nature of the profile of that diffusion, often mean that steady-state signals are reached faster and have higher signal-to-background ratios. Similarly, the diffusion profiles of gases and metabolites can be controlled and, if necessary, manipulated. Finally, the low thermal mass of these miniaturized devices makes it easy to control local temperature gradients.

The inherently small size of a cell (volume>fl>nl) complements the scales of lab-on-a-chip devices (where typically critical microfluidic channel dimensions may be between 30 and 100 μm in diameter). Working at these small scales necessitates that single-cell experimental systems differ from those associated with bulk methods. At the most fundamental level, the ability to locate and observe the cell is essential. This has led to new classes of machinable, low-autofluorescence and biocompatible polymers, thus enabling transparent microdevices to be made in which the cell can be readily addressed, optically.

In many cases the single cell, when positioned within the microchannel, will also need to be positioned or trapped in a predetermined location, making single-cell handling and manipulation necessary. The microsystem must be able to handle small volumes of fluid containing small quantities of analyte. Lab-on-a-chip or microfluidic systems have inherently large surface area-to-volume ratios, and strategies must be developed to ensure that molecules of interest are not lost to non-specific (adventitious) adsorption.

Microfluidic systems also provide an ability to control the local environment around the cell with precision, using methods that include having control over the physical or chemical nature of the surface to which the cell adheres, the local pH and temperature. If the cell is to be exposed to a variety of stimuli, multiple and often complex fluid-handling components (including valves and pumps) can be used. Together these ideas imply the need for the integration of cell positioning and chemical stimulation. If the cell is then to be analysed, lysis and analysis must be introduced onto the same platform to avoid sample loss or dilution, which would inevitably occur if multiple devices were used.

The field of microfluidics has been stepped up to meet these challenges, and over recent years the combination of microfluidics and nanotechnologies in lab-on-a-chip systems has fulfilled many of these requirements. Cells can be isolated, positioned and observed easily within microfluidic devices. Not only can their environment be precisely controlled, but high-electric fields can also be used to enable a variety of dynamic analytical methods, including electrophoresis, electroosmosis and dielectrophoresis (DEP).

1.1 Microfluidic devices for cell studies

The microfabrication of devices for biological studies has now evolved into an industry with two distinct, but overlapping, branches: array-based devices, whose success is widespread and has been extensively reviewed elsewhere (e.g. Blohm & Guiseppi-Elie 2001; Figeys 2002; Heller 2002; Templin et al. 2002), and lab-on-a-chip devices composed of enclosed microfluidic channels, chambers, and sometimes more complicated elements such as pumps and valves (Beebe et al. 2002; Sia & Whitesides 2003). Here we consider the progress of this second type of device towards a platform suitable for true single-cell studies.

Early lab-on-a-chip devices focused on the miniaturization of analytical chemical methods, in particular separations (Dolník et al. 1999), but there has been rapidly growing interest in using lab-on-a-chip devices for cell studies (Andersson & van der Berg 2003, 2004; Sims & Allbritton 2007). Cell manipulation within lab-on-a-chip devices and their subsequent stimulation and analysis are all currently active fields in which research is now focused on making measurements at the single-cell level.

The common methods employed for cell manipulation are mechanical, optical (Edel et al. 2007), magnetic or electric field based. For example, the mechanical trapping of cells using microfabricated filters (Carlson et al. 1997; Wilding et al. 1998) or other physical trapping designs has proved successful, although, in general, it does not offer the versatility of other methods (Rusu 2001; Cai et al. 2002). Laser tweezers and magnetic fields have been used to trap, sort and move cells (see Andersson & van der Berg (2003) and Yi et al. (2006) and references therein), and droplet-based microfluidics also lends itself naturally to the transport and isolation of single cells (Huebner et al. 2007). However, approaches involving the use of electric fields remain the most popular, combining the ease of field generation and control with speed and flexibility. In particular, electrophoresis and electroosmosis have both been used extensively for the transportation (and separation) of cells in microchannels (Manz et al. 1994; Li & Harrison 1997; Schasfoort 1999; Wong et al. 2004), while DEP has been successfully applied to manipulate a variety of cells (Markx et al. 1994; Becker et al. 1995; Fiedler et al. 1998; Wang et al. 2000).

Having positioned the cell, analysis in microfluidics can include visual (often fluorescence) observation of cells, their treatment with drugs or other stimuli or their electroporation. Single-cell analysis that has been performed on-chip now includes ion channel studies, drug injection and the active delivery of reagents to single cells, and has been recently reviewed thoroughly by Andersson & van der Berg (2004).

Finally, an essential element of a complete lab-on-a-chip system is the integration of cell lysis steps on-chip, so that the intracellular content can be analysed. Typical protocols for off-chip lysis include the use of enzymes, detergents or mechanical forces, but other lysis techniques may be more appropriate for integration into a microfluidic system (Belgrader 1999; Taylor et al. 2001; Schilling et al. 2002; Fox et al. 2006). While chemical lysis generally affects all membranes in the cell, including organelles, electroporation can be used to lyse only the outer cell membrane, keeping organelles intact. Furthermore, a recent publication has suggested the possibility of electroporation and lysis of organelles within a cell while keeping the outer membrane intact, highlighting the versatility and potential specificity of the approach (Gowrishankar et al. 2006). Recently, the use of electric fields to irreversibly electroporate cells has begun to be incorporated into microfluidic devices.

1.2 Microdevices for single-cell electroporation and lysis

When a pulsed electric field is applied across a cell, extra transmembrane potential (TMP) develops across the cellular membrane, which can compromise the membrane's integrity (Chang et al. 1992). The applied field causes pores to appear in the cellular membrane, which grow and eventually become hydrophilic at a threshold TMP of 0.5–1 V. Below the threshold TMP reversible electroporation occurs, in which pores are generated but can reseal. This process has been used for many years in bulk experiments to introduce molecules (proteins: Ho et al. 1997; DNA: Prasanna & Panda 1997, Suga et al. 2006; or drugs: Tsong & Kinosita 1985) into cells, and has been applied to single cells within a population using electrolyte-filled capillaries, pipettes and solid microelectrodes (Lundqvist et al. 1998; Haas et al. 2001; Nolkrantz et al. 2001, 2002; Rae & Levis 2002). However, at a TMP far above the threshold, irreversible electroporation leads to cell inactivation. Higher electric field strength (>10 kV cm−1) pulses cause mechanical breakdown of the cell membrane, providing a lysis technique to release cellular contents for analysis within microfluidic devices.

There are several advantages to miniaturizing electroporation and combining it with microfluidics. The small distances between the electrodes mean that low voltages are sufficient to generate high-electric field strengths between the electrodes, without electrolysis (and problems associated with local gas generation and pH shifts). The same generic microelectrodes can be used for both DEP and electroporation, introducing the possibility of trapping a single cell, electroporating it and determining the intracellular content.

In recent years, several publications have described the process of electroporation within microfluidic devices. One of the earliest devices designed for cell lysis by electroporation was by Lee & Tai (1999), who developed a micro cell-lysis device with a view to obtaining intracellular materials for further analysis. They used a saw-tooth electrode structure to lyse multiple cells and reported that yeast protoplasts and Escherichia coli could be lysed only with DC square pulses (not AC electric fields up to 20 kV cm−1 at 2 MHz), whereas Chinese cabbage protoplasts and radish protoplasts could be lysed with both DC and AC electric fields. This first step towards an efficient and integrated cell electroporation device, however, was not used at the single-cell level.

Huang & Rubinsky (1999, 2001; Davalos et al. 2000; Huang et al. 2003) published a series of articles studying the electroporation process itself, within microfluidic devices. They developed a chip that incorporates a single living cell in an electrical circuit, producing electrically measurable information about the state of an electroporated cell. The chip comprises three distinct layers, with the top and bottom layers made of n+ polysilicon and the middle layer a silicon nitride membrane with a hole smaller than the size of a cell etched in it. When the cells flow into the top layer of the device, a single cell becomes trapped in the hole due to the pressure difference between the top and bottom chambers. A pulsed voltage is then applied across the trapped cell using the conducting n+ polysilicon layers. The authors showed that the voltage for electroporation onset varies not only between cell types but also between individual cells from the same cell type, and went on to modify the device to perform impedance and optical measurements. More recently, Valero et al. (2005) have used a silicon and glass device with fabricated trapping sites to study the processes of apoptosis and necrosis in cells subject to electric fields. In their work, the voltage was applied over several trapped cells by gold wires and the process of the cell death studied by fluorescence.

A number of publications have since demonstrated the electroporation and lysis of individual cells within microfluidic chips, and the subsequent detection of some of the cellular contents. Gao et al. (2004) combined cell trapping, via adhesion to a channel wall, with lysis by an applied electric field, capillary electrophoresis (CE) separation and detection of glutathione into a glass microchip. In the same year, McClain et al. (2003) reported a flow-through microfluidic device combining cell lysis and CE separation by applying square wave pulses with a DC offset, achieving analysis rates of 7–12 cells min−1. In these cases, however, voltages were applied across the whole chip/separation channel via reservoirs; electrodes were not integrated into the design for specific, local electroporation of cells. Following these many advances, Olofsson et al. (2003) did a thorough review of single-cell electroporation in 2003.

Most recently, Lu et al. (2005) have reported a microfluidic electroporation device for cell lysis using a saw-tooth electrode design, with electrodes incorporated within the microfluidic channel. They used an AC field, minimizing electrolysis, and were able to lyse cells between the electrodes as they flowed through the channel. The dimensions of the integrated saw-tooth electrodes mean that small voltages were sufficient to electroporate the cells, and heating was negligible. However, this device was not used at the single-cell level.

We present here a study of single-cell DEP trapping, electroporation and lysis within a microfluidic lab-on-a-chip device. High throughput is not the goal; rather we aim to isolate and electroporate a single cell, with a view to the capture and analysis of the cellular content at the single-cell level. We use as a model system A431 human carcinoma cells that have been modified to express β-actin fused to enhanced green fluorescent protein (pEGFP–β-actin), allowing us to visualize and monitor the cell's cytoskeleton during trapping and electroporation using fluorescence confocal microscopy.

2. Experimental methods

2.1 Microfabrication of lab-on-a-chip structures

2.1.1 Microfluidic structures

The first step in microfabricating devices containing microchannels and chambers involved making a master structure, against which the elastomeric polymer, poly(dimethylsiloxane), PDMS, was moulded. A variety of structures including channels and sieves (for retaining beads) could be made using different photomasks. To this end, an AZ4562 positive photoresist (Origine) was spin-coated onto a silicon wafer at 4000g to a thickness of 6 μm. After baking the substrate for 1 min at 100°C, the resist was exposed through a suitable photomask for 12.5 s to UV light at 7 mW cm−2 with a Karl Suss MA6 Mask Aligner and was developed in a 1 : 4 ratio of an AZ400K developer : water mixture. The silicon wafer was then dry etched in an STS–ICP system, and the photoresist was removed with acetone. To prevent the PDMS features sticking to the master, a hexamethyldisilazane layer was spun on the wafer. A 10 : 1 mixture of PDMS base polymer and curing agent (Dow Corning) was poured onto the master, degased in a desiccator chamber to remove bubbles and cured at 70°C for 2 hours. As stated, a variety of different structures could be made in this manner.

2.1.2 Microelectrode structures

The microelectrodes were fabricated on a glass substrate using standard photolithographic methods of pattern transfer and lift-off (either using a microscope slide or coverslip). In detail, after pattern transfer into a 1.5 μm S1818 photoresist on the glass slide, a 60 nm gold layer (on a 10 nm titanium adhesion layer) was deposited by evaporation. The remaining photoresist was lifted off by washing in acetone. In order to improve the bonding of the PDMS to gold surface, a thin layer of 25% hydrogen silsesquioxane solution in methyl isobutylketone was spun on the electrodes to avoid sample leakage at the PDMS–gold interface.

2.1.3 Integration and connection

Microfluidic inlets were punched into the PDMS, and the PDMS and glass slide were both exposed to oxygen plasma for 18 s at 100 W (in a Gala instrument barrel asher) to generate appropriate silanol groups on the surface. The PDMS gasket, moulded against the silicon master to produce microchannels, sieves or chambers, as described above, was then sealed against the gold-on-glass microstructured substrate. The inlets of the microsystem were then connected to a syringe pump (KD Scientific) via PTFE capillary tubing (0.305 mm ID).

2.2 Cell culture, transfection and handling

A431 squamous cell carcinoma cells stably transfected with pEGFP–β-actin were kindly provided by Dr Val Brunton (Beatson Institute, Glasgow, UK). Briefly, A431 cells were transfected with 5 μg pEGFP–β-actin using the Amaxa nucleofector transfection system with solution P and electroporation program P20 (Amaxa GmbH, Cologne, Germany) as detailed in the manufacturer's protocol. Transfected cells were allowed to recover for 24 hours and then cells positive for green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression were selected using a BD FACS Vantage (Becton Dickinson Biosciences, Oxford, UK). The selected pool of A431 pEGFP–β-actin-expressing cells were maintained in normal growth medium supplemented with 0.6 mg ml−1 G418.

For electroporation and dielectrophoretic experiments, the cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and were then suspended in 0.6 M d-sorbitol and injected into the microfluidic chip using a syringe and pressure-driven flow.

2.3 Bead modification

Streptavidin-coated latex microspheres of 10 μm diameter (Bangs labs, IN, USA) were used as a substrate for the capture of protein contents. An anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) was biotinylated following the manufacturer's protocol (Vector Labs, UK) and the excess biotin was removed in a microspin column (GE Healthcare, UK). The biotinylated antibody was then incubated with the streptavidin-coated microspheres at room temperature for 1 hour with continuous gentle tumbling. After incubation the beads were washed several times in PBS with 0.01% TWEEN, then loaded into the microchannel using pressure-driven flow and trapped by the sieve constructed of PDMS pillars (Monaghan et al. 2007).

2.4 DEP and electroporation

A 20 μm double pair of electrodes with a length of 5 mm was designed. The electrodes were positioned perpendicular to the channel, avoiding alignment steps and giving reliable bonding. The 10 μm gap between the electrodes resulted in the generation of an electric field above 1 kV cm−1 in the channel by applying low voltages of up to 20 V. A TTi TG120 function generator was used to apply the AC signal, plugged to the device with wires soldered to gold areas connected to the electrodes. An AC field with a sinusoidal waveform of between 100 kHz and 1 MHz was applied. Frequencies below 100 kHz were not used, to avoid electrohydrolysis and bubble formation. Optical and fluorescence imaging was performed in a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta Confocal Microscope, using either a Zeiss 63× oil emersion objective (1.4 NA) or a Zeiss 20× dry objective.

3. Results

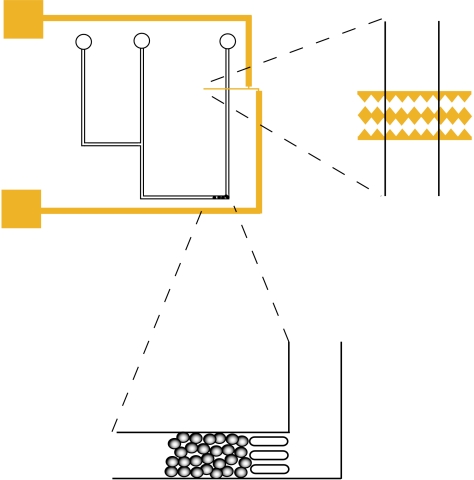

The cells were observed to flow through the microfluidic channel without disruption, under a pressure gradient, in the absence of an electric field. On applying a field at 1 MHz frequency and 20 Vpp, isolated cells could be trapped by a positive dielectrophoretic force, bringing them into close contact with the microelectrodes. The dielectrophoretic force was sufficiently strong, so that it was possible to hold the cell against a microfluidic flow of up to 30 μl min−1 without bursting or visible disruption of the cell membrane (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic showing the saw-tooth gold electrodes (on a glass slide) positioned within the PDMS microchannels, and the bead bed for protein capture created by trapping microspheres with three approximately 25 μm PDMS pillars. Simple microchannels of depth approximately 50 μm and width approximately 100 μm were used, with two inlets (one for the cell suspension and one for introducing the microspheres and/or a buffer for flushing through the system) and a single outlet.

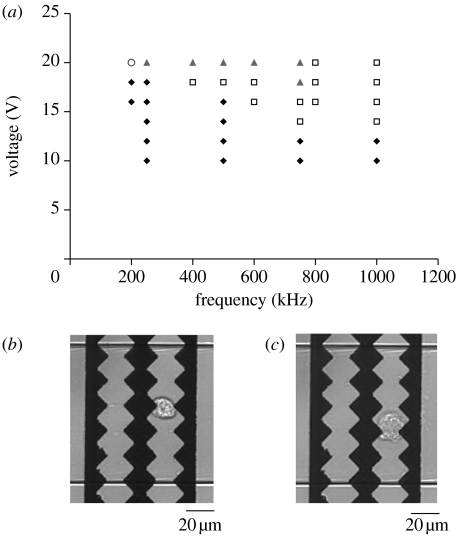

On reducing the frequency to 100 kHz, the trapped cells burst, releasing their cytoplasmic content into the microfluidic channel, as evidenced by the creation of a hemispherical diffusion front of GFP–actin. To determine the range of frequency and voltages at which these two different types of behaviour could be observed in our system, the cells were flowed continuously through the device. The field strength and frequency were varied while visually monitoring the cell behaviour by transmitted light microscopy. Time-lapse videos were recorded of the different types of behaviour observed. Figure 2a shows the regions in which the cells were trapped but not lysed, trapped and subsequently lysed after several seconds, and where cell lysis was immediate but no trapping was observed. Figure 2b,c shows transmitted light images of the trapping and lysis of a single cell.

Figure 2.

(a) Graph showing regions of dielectrophoretic trapping (squares), trapping and lysis (triangles), immediate lysis (circle) and unperturbed cell flow (diamonds) in the frequency–voltage plane. (b) A cell trapped between the electrodes by DEP at 1 MHz and 18 Vpp. (c) A cell burst after trapping at 1 MHz and 20 Vpp followed by electroporation and lysis at 500 kHz and 20 Vpp.

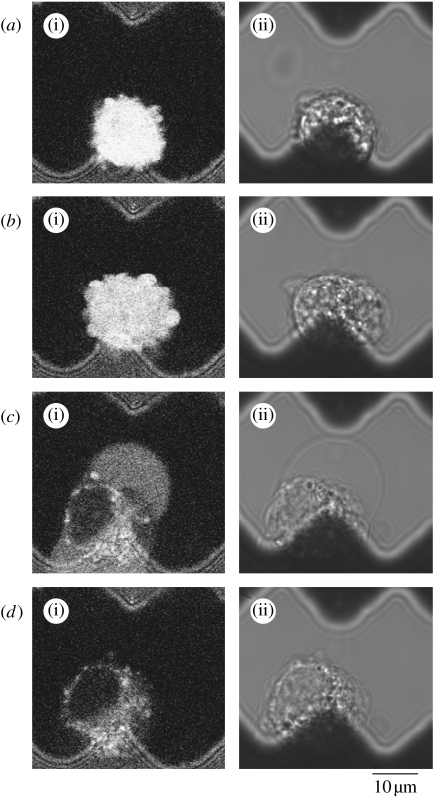

On closer observation of the process using fluorescence confocal microscopy (figure 3), electroporation was seen to first result in the cell becoming enlarged due to osmotic flow into the cytoplasm (figure 3b). After becoming enlarged the cell burst, releasing cellular content into the surrounding fluid (figure 3c). The fractured cell membrane and other cell debris were maintained between the electrodes (figure 3d), preventing blockage of the device and providing the potential for sensitive fluorescence detection of the single-cell content downstream (see video in electronic supplementary material).

Figure 3.

Confocal micrographs showing the process of single-cell electroporation on the application of a 500 kHz, 20 Vpp pulsed electric field. (a(i)–d(i)) Fluorescence images excited at 488 nm and emission collected above 505 nm and (a(ii)–d(ii)) transmitted light images collected simultaneously.

4. Conclusions and future directions

We have designed and fabricated a microfluidic device for the efficient trapping and lysis of single cells. For a range of voltages and frequencies, we have shown that single cells can be trapped between saw-tooth electrodes by DEP and held against the flow, and that by then decreasing the frequency the cells could be lysed by electroporation. We have visualized by confocal fluorescence microscopy the release of the cell contents into the microchannel by observing the fluorescent pEGFP–β-actin construct, and demonstrated that the remaining cell debris can be retained between the electrodes by DEP after the cell contents have been released.

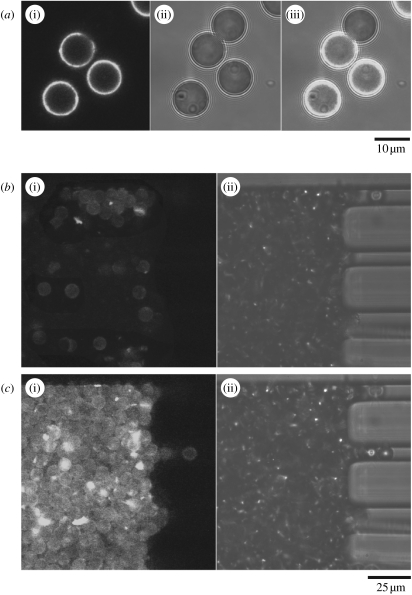

Such cell trapping and lysis devices can be combined with separation on a chip, where affinity capture seems an especially attractive proposition. Affinity capture by antibodies can isolate selected cellular components with high specificity and sensitivity making true single-cell analysis feasible. Antibodies can be used both for the capture of the released contents and for the detection of captured materials. For this the capturing antibodies need to be immobilized in a format compatible with microfluidic devices, such as microbeads. We are currently interfacing the microbead affinity columns with the electroporation device. In a pilot experiment, we have bound an anti-β-actin antibody to microbeads (10 μm diameter polymer microspheres), trapped the beads in the microchannel using a series of PDMS pillars and shown that the beads can be used to isolate GFP–β-actin from A431 cell lysates (figure 4). In this case detection was afforded by the intrinsic fluorescence of GFP. This proof of principle experiment demonstrates the potential of our method—the GFP could be substituted by a fluorescently labelled secondary antibody that reacts with an antigen of interest trapped on the microbeads.

Figure 4.

(a) Confocal images of the anti-β-actin modified beads, some of which have been incubated with cell lysate to demonstrate molecular capture of GFP–β-actin. (i)–(iii) The fluorescence image (excited at 488 nm and emission collected above 505 nm), transmitted light image and an overlay of the fluorescence and transmitted light images. The non-fluorescent beads have not been incubated with cell lysate, whereas the beads that were incubated with cell lysate show a clear fluorescence signal. (b) Anti-actin modified beads loaded into a microfluidic channel and trapped by rectangular approximately 25 μm PDMS pillars. (c) Fluorescence confocal image showing the capture of GFP–β-actin from a lysed cell population as it flowed over the bead bed.

This sandwich type of assay permits the analysis of only single proteins, but ways to multiplex can easily be envisaged. For instance, a broad specificity antibody (or mixture of antibodies) could be used for trapping. Ideal are antibodies that pull out subproteomes, e.g. antibodies against posttranslational modifications such as phosphotyrosine. After affinity adsorption the microbeads could be washed and randomly dispersed into individual chambers. Beads in each chamber then could be individually stained with secondary antibodies for the identification of the different tyrosine phosphorylated proteins retained on the microbeads. With this method one could survey, for example, proteins that become tyrosine phosphorylated in response to epidermal growth factor.

In addition to antibodies, there are various options to construct affinity surfaces on the microbeads. These include chromatographic surfaces that separate according to differential hydrophilic/hydrophobic properties, immobilized drugs (Bantscheff 2007), lectins that retain glycosylated proteins or aptamers (Hutanu & Remcho 2007). There is little limitation to creativity in this respect. The more difficult task is to design detection methods that can identify the proteins trapped on the microbeads. The challenge is to transcend the biased approaches, such as antibodies and aptamers, by unbiased identification methods. An obvious one is mass spectrometry (MS), although the small amounts make this difficult. With the current sensitivity of MS being in the low-femtomolar/high-attomolar range, it requires approximately 1 million copies of a medium-sized protein of 50 kDa to be detectable by MS. However, if high surface concentrations can be reached and sample ionization improved, the range of sensitivity should be extendable over one or two orders of magnitude.

The ability to biochemically analyse single cells will have applications in many areas across biology and biomedicine. An example of major interest is stem cells. These cells can divide asymmetrically, where one daughter remains a stem cell while the other differentiates (Knoblich 2008). The ability to investigate single cells will be necessary to understand the intricacies of this process. The potential reward is as big as the challenge, given that the massive worldwide efforts to use stem cells for therapeutic purposes will ultimately require a deeper understanding of the mechanisms that preserve their stem cells properties as well as the processes that trigger differentiation.

There are even further reaching ramifications pertaining to intrinsic cell-to-cell variability. This problem is ubiquitous in both basic and applied biomedical research and rapidly gaining attention. Even modern biochemistry routinely uses millions of cells for an experiment, recording, as a result, the average across this population. However, increasing evidence suggests that individual cells vary in their responses due to noise and by design. For example, protein levels fluctuate between different cells of the same population (Sigal 2006); or some signalling pathways are designed to respond switch-like rather than with classical Michaelis–Menten type kinetics (Ferrell & Xiong 2001). However, a switch-like response of individual cells will appear as a graded response across a population, if an increase in stimulation increases the number of responding cells, and hence at the population level becomes indistinguishable from a genuinely graded response of individual cells. These different types of responses usually use different control mechanisms but can also use transition between each other under certain conditions (Bhalla et al. 2002). It is of importance to deconvolute these response types as the effects of intervention, e.g. by drugs, which can be fundamentally different. In hypersensitive (switch-like) systems it is sufficient to suppress activity below a threshold value in order to achieve complete inhibition, while an analogous system with a graded response will show increasing inhibition proportional to the increase in drug dosage. Thus, it is of general importance to deconvolute population responses to single-cell responses. It is expected that, in the future, biology and biochemistry will increasingly turn to the microengineering world for new solutions to tackle this problem.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement is made to the BBSRC, MRC and EPSRC, which jointly supported this work through the funding of the IRC in Proteomic Technologies.

Footnotes

One contribution of 7 to a Theme Supplement ‘Single-cell analysis’.

Supplementary Material

A single A431 cell undergoing electroporation, lysis and protein release on the application of a 500 kHz, 20 Vpp pulsed electrical field

References

- Andersson H., van der Berg A. Microfluidic devices for cellomics: a review. Sens. Actuators B. 2003;92:315–325. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4005(03)00266-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson H., van der Berg A. Microtechnologies and nanotechnologies for single-cell analysis. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2004;15:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantscheff M., et al. Quantitative chemical proteomics reveals mechanisms of action of clinical ABL kinase inhibitors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:1035–1044. doi: 10.1038/nbt1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker F., Wang X., Huang Y., Pethig R., Vykoukal J., Gascoyne P. Separation of human breast cancer cells from blood by differential dielectric affinity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:860–864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe D.J., Mensing G.A., Walker G.M. Physics and applications of microfluidics in biology. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2002;4:261–286. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.4.112601.125916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgrader P., et al. A minisonicator to rapidly disrupt bacterial spores for DNA analysis. Anal. Chem. 1999;71:4232–4236. doi: 10.1021/ac990347o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla U.S., Ram P.T., Iyengar R. MAP kinase phosphatase as a locus of flexibility in a mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling network. Science. 2002;297:1018–1023. doi: 10.1126/science.1068873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blohm D.H., Guiseppi-Elie A. New developments in microarray technology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2001;12:41–47. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X., Klauke N., Glidle A., Cobbold P., Smith G., Cooper J.M. Ultra-low-volume, real-time measurements of lactate from the single heart cell using microsystems technology. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:908–914. doi: 10.1021/ac010941+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson R., Gabel C., Chan S., Austin R. Self-sorting of white blood cells in a lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997;79:2149–2152. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.79.2149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang D.C., Chassy B.M., Saunders J.A. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1992. Guide to electroporation and electrofusion. [Google Scholar]

- Davalos R., Huang Y., Rubinsky B. Electroporation: bioelectrochemical mass transfer at the nanoscale. Microscale Thermophys. Eng. 2000;4:147–159. doi: 10.1080/10893950050148115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dolník V., Liu S., Jovanovich S. Capillary electrophoresis on microchip. Electrophoresis. 1999;21:41–54. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(20000101)21:1%3C41::AID-ELPS41%3E3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edel J.B., Lahoud P., Cass A.E., deMello A.J. Discrimination between single Escherichia coli cells using time-resolved confocal spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:1129–1134. doi: 10.1021/jp066530k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell J.E., Xiong W. Bistability in cell signaling: how to make continuous processes discontinuous, and reversible processes irreversible. Chaos. 2001;11:227–236. doi: 10.1063/1.1349894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler S., Shirley S., Schnelle T., Fuhr G. Dielectrophoretic sorting of particles and cells in a microsystem. Anal. Chem. 1998;70:1909–1915. doi: 10.1021/ac971063b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figeys D. Adapting arrays and lab-on-a-chip technology for proteomics. Proteomics. 2002;2:373–382. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200204)2:4%3C373::AID-PROT373%3E3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox M.B., Esveld D.C., Valero A., Luttge R., Mastwijk H.C., Bartels P.V., van der Berg A., Boom R.M. Electroporation of cells in microfluidic devices: a review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006;385:474–485. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Yin X.F., Fang Z.L. Integration of single cell injection, cell lysis separation and detection of intracellular constituents on a microfluidic chip. Lab Chip. 2004;4:47–52. doi: 10.1039/b310552k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowrishankar T.R., Esser A.T., Vasilkoski Z., Smith K.C., Weaver J.C. Microdosimetry for conventional and supra-electroporation in cells with organelles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;341:1266–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas K., Sin W.C., Javaherian A., Li Z., Cline H.T. Single-cell electroporation for gene transfer in vivo. Neuron. 2001;29:583–591. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller M.J. DNA microarray technology: devices, systems, and applications. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2002;4:129–153. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.4.020702.153438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho S.Y., Mittal G.S., Cross J.D. Effects of high electric field pulses on the activity of selected enzymes. J. Food Eng. 1997;31:69–84. doi: 10.1016/S0260-8774(96)00052-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Rubinsky B. Micro-electroporation: improving the efficiency and understanding of electrical permeabilization of cells. Biomed. Microdev. 1999;2:145–150. doi: 10.1023/A:1009901821588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Rubinsky B. Microfabricated electroporation chip for single cell membrane permiabilization. Sens. Actuators A. 2001;89:242–249. doi: 10.1016/S0924-4247(00)00557-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Sekhon N.S., Borninski J., Chen N., Rubinsky B. Instantaneous, quantitative single-cell viability assessment by electrical evaluation of cell membrane integrity with microfabricated devices. Sens. Actuators A. 2003;105:31–39. doi: 10.1016/S0924-4247(03)00084-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner A., Srisa-Art M., Holt D., Abell C., Hollfelder F., deMello A.J., Edel J.B. Quantitative detection of protein expression in single cells using droplet microfluidics. Chem. Commun. 2007;28:1218–1220. doi: 10.1039/b618570c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutanu D., Remcho V.T. Aptamers as molecular recognition elements in chromatographic separations. Adv. Chromatogr. 2007;45:173–196. doi: 10.1201/9781420018066.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblich J.A. Mechanisms of asymmetric stem cell division. Cell. 2008;132:583–597. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.-W., Tai Y.-C. A micro cell lysis device. Sens. Actuators A. 1999;73:74–79. doi: 10.1016/S0924-4247(98)00257-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li P.C.H., Harrison D.J. Transport, manipulation and reaction of biological cells on-chip using electrokinetic effects. Anal. Chem. 1997;69:1564–1568. doi: 10.1021/ac9606564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H., Schmidt M.A., Jensen K.F. A microfluidic electroporation device for cell lysis. Lab Chip. 2005;5:23–29. doi: 10.1039/b406205a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist J.A., Sahlin F., Åberg M.A., Strömberg A., Eriksson P.S., Orwar O. Altering the biochemical state of individual cultured cells and organelles with ultramicroelectrodes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:10 356–10 360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manz A., Effenhauser C., Bruggraf N., Harrison J., Seiler K., Fluri K. Electroosmotic pumping and electrophoretic separations for miniaturized chemical analysis systems. J. Micromech. Microeng. 1994;4:257–265. doi: 10.1088/0960-1317/4/4/010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markx G., Huang Y., Zhou X., Pethig R. Dielectrophoretic characterization and separation of microorganisms. Microbiology. 1994;140:585–591. [Google Scholar]

- McClain M.A., Culbertson C.T., Jacobson S.C., Allbritton N.L., Sims C.E., Ramsey J.M. Microfluidic devices for the high-throughput chemical analysis of cells. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:5646–5655. doi: 10.1021/ac0346510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan P.B., McCarney K.M., Ricketts A., Littleford R.E., Docherty F., Smith W.E., Graham D., Cooper J.M. Bead-based diagnostic assay for chlamydia using nanoparticle-mediated surface-enhanced resonance raman scattering detection within a lab-on-a-chip format. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:2844–2849. doi: 10.1021/ac061769i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolkrantz K., Farre C., Brederlau A., Karlsson R.I., Brennan C., Eriksson P.S., Weber S.G., Sandberg M., Orwar O. Electroporation of single cells and tissues with an electrolyte-filled capillary. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:4469–4477. doi: 10.1021/ac010403x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolkrantz K., Farre C., Hurtig K.J., Rylander P., Orwar O. Functional screening of intracellular proteins in single cells and in patterned cell arrays using electroporation. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:4300–4305. doi: 10.1021/ac025584x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson J., Nolkrantz K., Ryttsen F., Lambie B.A., Weber S.G., Orwar O. Single-cell electroporation. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2003;14:29–34. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(02)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna G.L., Panda T. Electroporation: basic principles, practical considerations and applications in molecular biology. Bioprocess Eng. 1997;16:261–264. doi: 10.1007/s004490050319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rae J.L., Levis R.A. Single-cell electroporation. Pflugers Arch. 2002;443:664–670. doi: 10.1007/s00424-001-0753-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusu C., et al. Direct integration of micromachined pipettes in a flow channel for single DNA molecule study by optical tweezers. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2001;10:238–247. doi: 10.1109/84.925758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schasfoort R.B.M. Field-effect flow control for microfabricated fluidic networks. Science. 1999;286:942–945. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling E., Kamholz A., Yager P. Cell lysis and protein extraction in a microfluidic device with detection by a fluorogenic enzyme assay. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:1798–1804. doi: 10.1021/ac015640e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sia S.K., Whitesides G.M. Microfluidic devices fabricated in poly(dimethylsiloxane) for biological studies. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:3563–3576. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigal A., et al. Variability and memory of protein levels in human cells. Nature. 2006;444:643–646. doi: 10.1038/nature05316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims C.E., Allbritton N.L. Analysis of single mammalian cells on-chip. Lab Chip. 2007;7:423–440. doi: 10.1039/b615235j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga M., Goto A., Hatakeyama T. Control by osmolarity and electric field strength of electro-induced gene transfer and protein release in fission yeast cells. J. Electrostat. 2006;64:796–801. doi: 10.1016/j.elstat.2006.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M., Belgrader P., Furman B., Pourahmadi F., Kovacs G., Northrup A. Lysing bacterial spores by sonication through a flexible interface in a microfluidic system. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:492–496. doi: 10.1021/ac000779v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Templin M.F., Stoll D., Schrenk M., Traub P.C., Vöhringer C.F., Joos T.O. Protein microarray technology. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20:160–166. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(01)01910-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsong T.Y., Kinosita K. Use of voltage pulses for the pore opening and drug loading and the subsequent resealing of red blood cells. Bibl. Haematol. (Basel) 1985;51:108–114. doi: 10.1159/000410233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valero A., Merino F., Wolbers F., Luttge R., Vermes I., Andersson S.M.H., van den Berg A. Apoptotic cell death dynamics of HL60 cells studied using a microfluidic cell trap device. Lab Chip. 2005;5:49–55. doi: 10.1039/b415813j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Yang J., Huang Y., Vykoukal J., Becker F., Gascoyne P. Cell separation by dielectrophoretic field-flow-fractionation. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:832–839. doi: 10.1021/ac990922o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilding P., Kricka L.J., Cheng J., Hvichia G., Shoffner M.A., Fortina P. Integrated cell isolation and polymerase chain reaction analysis using silicon microfilter chambers. Anal. Biochem. 1998;257:95–100. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P.K., Wang T.H., Deval J.H., Ho C.M. Electrokinetics in micro devices for biotechnological applications. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2004;9:366–376. doi: 10.1109/TMECH.2004.828659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yi C., Li C.-W., Ji S., Yang M. Microfluidics technology for manipulation and analysis of biological cells. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2006;560:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A single A431 cell undergoing electroporation, lysis and protein release on the application of a 500 kHz, 20 Vpp pulsed electrical field