Abstract

Cancer mucosa antigens comprise an emerging category of self-antigens expressed normally in immunologically privileged mucosal compartments and universally by their derivative tumors (1, 2). These antigens leverage the established immunological partitioning of systemic and mucosal compartments (3, 4), limiting tolerance opposing systemic antitumor efficacy (5). An unresolved issue surrounding self-antigens as immunotherapeutic targets is autoimmunity following systemic immunization (6-8). In the context of cancer mucosa antigens, immune effectors to self-antigens risk amplifying mucosal inflammatory disease promoting carcinogenesis (9). Here, we examined the relationship between immunotherapy for systemic colon cancer metastases targeting the intestinal cancer mucosa antigen GCC and its impact on inflammatory bowel disease and carcinogenesis in mice. Immunization with GCC-expressing viral vectors opposed nascent tumor growth in mouse models of pulmonary metastasis reflecting systemic lineage-specific tolerance characterized by CD8+, but not CD4+, T cell or antibody responses. Responses protecting against systemic metastases spared intestinal epithelium from autoimmunity, and systemic GCC immunity did not amplify chemically-induced inflammatory bowel disease. Moreover, GCC immunization failed to promote intestinal carcinogenesis induced by germline mutations or chronic inflammation. The established role of CD8+ T cells in antitumor efficacy, but CD4+ T cells in autoimmunity, suggest lineage-specific responses to GCC are particularly advantageous to protect against systemic metastases without mucosal inflammation. These observations support the utility of GCC-targeted immunotherapy in patients at risk for systemic metastases, including those with inflammatory bowel disease, hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes, and sporadic colorectal cancer.

Keywords: Cancer, immunotherapy, cancer mucosa antigen, autoimmunity, guanylyl cyclase C

Introduction

A principle obstacle to cancer immunotherapy is the limited availability of antigens that are tumor-specific, immunogenic and universally expressed by patients (10). In the absence of such targets, anticancer immune responses are directed to tissue, rather than tumor, -specific antigens. Limitations to employing self-antigens include tolerance, which restricts antitumor immunity, and therapy-induced autoimmunity (11). These restrictions have been circumvented by employing self-proteins, including cancer testis antigens, expressed in immune-privileged compartments (12). Their expression in tumors outside those compartments offers opportunities for immunological responses essentially to tumor-specific antigens. However, this approach has been limited by the heterogeneous expression of these antigens by tumors.

This theme of immune segregation has been extended recently to the expression of mucosa-restricted antigens by tumors, exploiting the asymmetry in immunological cross-talk between mucosal and systemic compartments (2). This asymmetry offers unique benefits reflecting the nexus of immunological privilege, limiting systemic tolerance to mucosal antigens, which promotes antitumor responses, and immunological partitioning, which protects mucosae from systemic immune responses, limiting autoimmunity (3, 4). These observations suggest a previously unappreciated paradigm for tumors originating in mucosae, in which vaccination with cancer mucosa antigens produces effective therapeutic responses opposing systemic metastases without inducing mucosal inflammation and autoimmunity (1, 2, 5).

Guanylyl cyclase C (GCC) is a member of the guanylyl cyclase family of receptors, which convert GTP to the second messenger cyclic GMP (13). GCC is exclusively expressed by intestinal epithelial cells, and uniformly over-expressed by primary and metastatic colorectal tumors (14-16). GCC is the index example of cancer mucosa antigens, reflecting expression normally restricted to mucosae, but universally bridging the central immune compartment by tumor metastasis in all patients. Indeed, immunization with viral vectors containing GCC provides protection in prophylactic and therapeutic mouse models of parenchymal colon cancer metastases (1, 2, 5).

The mucosal immune system discriminates between normal antigens and autoantigens to which a response is inappropriate and invading microorganisms to which a response is protective. Occasionally, protective tolerance is lost producing inflammatory bowel disease, reflecting barrier disruption and exposure of mucosal antigens to dendritic cells in the context of costimulatory signals provided by bacterial pathogens, resulting in pathologic T cell responses (17-20). Of significance, patients with inflammatory bowel disease have a 10% - 50% risk of developing colorectal cancer (21) reflecting tumor promotion by chronic inflammation (22). Indeed, intestinal inflammation predisposes mice to tumor induction by carcinogens or germline mutations (23, 24).

These foregoing observations bring into specific relief issues of safety of immunotherapy targeting cancer mucosa antigens, and the risk of autoimmune disease and inflammation-associated cancer. These issues are underscored by the potential application of such vaccines to prophylaxis of metastases in patients at greatest risk for metastatic tumors, particularly patients with inflammatory bowel disease and hereditary colon cancer syndromes (25). In those clinical populations, the convergence of ongoing barrier disruption with induction of mucosally-targeted immune effector cells could exacerbate intestinal inflammation leading to carcinogenesis. These considerations highlight the potential risk for GCC-targeted immunity to amplify mucosal inflammation and intestinal tumorigenesis. Here, we explored the relationship between the therapeutic efficacy of GCC immunization to protect against metastatic colorectal cancer and its impact on autoimmunity and tumorigenesis in mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease and intestinal carcinogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were obtained from the NCI Animal Production Program (Frederick, MD). GCC-deficient (GCC-/-) and wild-type (GCC+/+) C57BL/6 littermates mice were described previously (5, 26). APCmin/+ mice were acquired from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). Animal protocols were approved by the Thomas Jefferson University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Recombinant viruses

GCC and control adenovirus (AV), rabies virus (RV) and vaccinia virus (VV) were described previously (5). NP/SIINFEKL-AV was also described previously (27). For immunizations, mice received 1×108 IFU of adenovirus, 1×107 FFU of rabies, or 1×107 PFU of vaccinia by IM injection of the anterior tibialis.

Cell lines

C57BL/6-derived MC38 colon cancer cells were provided by Jeffrey Schlom (National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). BALB/c-derived CT26 colorectal cancer cells were from ATCC (Manassas, Virginia). The GCC-expressing CT26 cell line was described previously (5).

ELISA

GCC and AV -specific ELISAs were described previously (5). Briefly, immunosorbent plates (Nunc, Rochester, New York) were coated with purified GCC-6×His at 10 μg/ml or with irrelevant adenoviral particles at 1×107 IFU/ml. Coated plates were incubated with serum collected from immunized mice and specific antibodies were detected with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Jackson Laboratories) and ABTS substrate (Pierce, Rockford, Illinois).

ELISpot

GCC, AV and β-galactosidase -specific ELISpots were described previously (5). Briefly, multiscreen filtration plates (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts) were coated with anti-mouse IFNγ-capture antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, California) and splenocytes were plated at 250,000 or 500,000 cells per well for CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses, respectively. For CD8+ T cell responses, MC38 cells expressing GCC or LacZ were treated with 1000 U/ml recombinant mouse IFNγ (EMD Biosciences, San Diego, California) for 48 hours to increase MHC expression and were used as stimulator cells. For SIINFEKL-specific responses, MC57G cells stably expressing a SIINFEKL minigene were used as stimulator cells. For CD4+ T cell responses, splenocytes were incubated on antibody-coated plates with GCC-6×His or irrelevant purified adenovirus particles. After ~24 hours of stimulation, spots were developed with biotinylated anti-IFNγ detection antibody (BD Pharmingen) and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (Pierce), followed by NBT/BCIP substrate (Pierce). Spot forming cells (SFCs) were enumerated using computer-assisted video imaging analysis (ImmunoSpot v3, Cellular Technology, Shaker Heights, Ohio).

Metastatic Tumors and PET/microCT

BALB/c mice were immunized 7 days prior to administration of 5×105 CT26-GCC cells via tail vein injection to establish lung metastases. Mice received 0.45 mCi 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose 14 days after tumor challenge, and PET images were collected 2 hours later on a Mosaic scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, Massachusetts). CT images were acquired on a microCAT II (Imtek, Inc, Knoxville, Tennessee). Mice were then euthanized and metastases enumerated (5).

DSS Colitis

Female 6 week old C57BL/6 mice were immunized with GCC-AV or Control-AV, RV and VV at 28 day intervals, a heterologous prime boost regimen (PBB) that maximizes GCC-specific antitumor responses (5). Mice were treated 4 days after the final immunization with 4% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri) ad libitum in the drinking water for 7 d, and body weights were monitored daily beginning at DSS administration (28, 29). Some mice were euthanized on day 9 following the first DSS administration and tissues collected for assessment of colitis.

Colitis Assessment

Intestinal contents were scored for stool consistency (normal = 0, slightly loose feces = 1, loose feces = 2, watery diarrhea = 3) and visible fecal blood (normal = 0, slightly bloody = 1, bloody = 2, blood in whole colon = 3) (29). Subsequently, intestines where formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, stained with hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) and scored by a blinded pathologist (RB). The histological score represents the arithmetic sum of the epithelial damage score (normal = 0, loss of goblet cells = 1, loss of goblet cells in large areas = 2, loss of crypts = 3, loss of crypts in large area = 4) and inflammation score (no infiltrate = 0, infiltrate around crypt base = 1, infiltrate reaching muscularis mucosae = 2, extensive infiltration reaching the muscularis mucosae, thickening of the mucosa with abundant edema = 3, infiltration of the submucosa = 4) (28).

Tumorigenesis

Male and female 4 week old APCmin/+ mice were immunized with AV, RV and VV as above and tumorigenesis quantified at 14 weeks of age. For inflammation-associated tumorigenesis, female 6 week old C57BL/6 mice were immunized as above with AV, RV and VV. A single dose of axozymethane (AOM; Sigma Aldrich) 15 mg/kg was administered intraperitoneally 3 days before the final immunization and 4% DSS administration began 7 days later. Following 7 days of DSS, water was returned to the mice for 14 days, followed by 2 more cycles of 3% DSS (24). Tumorigenesis was quantified 10 days after the final cycle of DSS. Tumors were enumerated and their size quantified under a dissecting microscope. Tumor burden in APCmin/+ mice was determined by calculating the sum of the (diameter)2 of individual tumors for the small and large intestines in each mouse (26). Intestinal tissues were processed for H&E staining and tumors from AOM-DSS treated mice were confirmed by histology and graded (AB).

Results

GCC induces lineage-specific immune effector cell responses

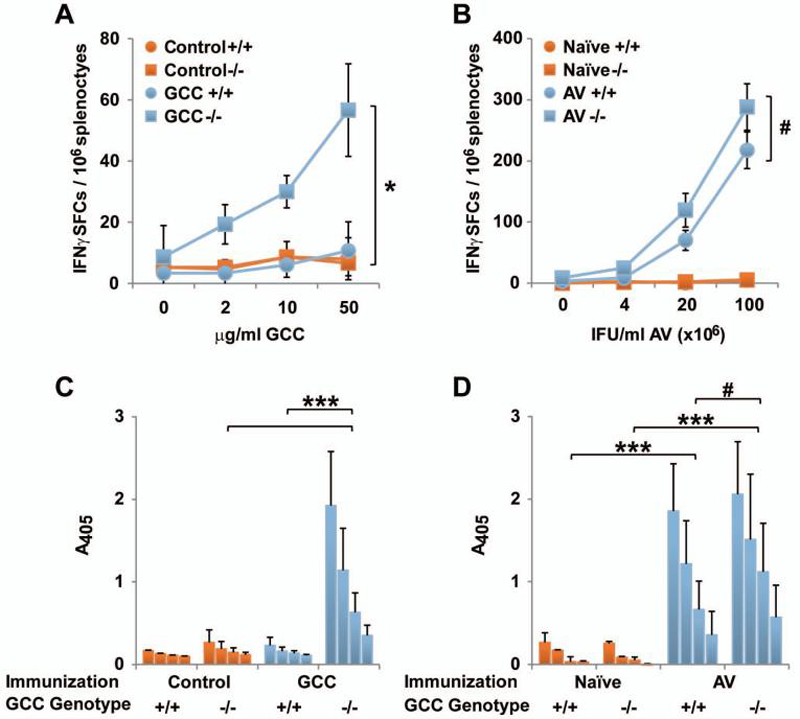

The extracellular domain of GCC is not homologous with other guanylyl cyclases, limiting the possibility and extent of central tolerance, and is a target for immunotherapy to prevent GCC-expressing metastatic colorectal cancer in mice (1, 2, 5). Here, GCC+/+ and GCC-/- C57BL/6 mice were immunized with adenovirus (AV) expressing the extracellular domain of GCC (GCC-AV) or Control-AV and immune responses quantified after 10 d. GCC-/- mice, in which tolerance to the target antigen is absent, were employed as a positive control (5). While GCC-specific CD4+ T cell (Fig. 1A) and antibody (Fig. 1C) responses were produced in GCC-/- mice upon a single immunization with GCC-AV, these responses were absent in GCC+/+ mice (Fig. 1A and C). Equivalent adenovirus-specific antibody (Fig. 1B) and CD4+ T cell (Fig. 1D) responses in GCC+/+ and GCC-/- mice confirm that eliminating GCC expression does not alter antigen-specific immune responses beyond those to GCC.

Figure 1. GCC-specific CD4+ T cell and antibody tolerance.

A, GCC-specific CD4+ T cell responses in Control-AV- or GCC-AV-immunized GCC+/+ (+/+) and GCC-/- (-/-) C57BL/6 mice, measured by IFNγ ELISpot following restimulation with recombinant GCC-6×His protein (* P <0.05, two-sided Student's t test on values at 50 μg/ml). B, AV-specific CD4+ T cell responses in GCC-AV-immunized GCC+/+ (+/+) and GCC-/- (-/-) C57BL/6 mice, measured by IFNγ ELISpot following restimulation with AV particles (# P >0.05, two-sided Student's t test on values at 1×108 IFU/ml). Data in A and B indicate pooled analysis of N=2-3 mice per group, and are representative of four independent experiments. C, ELISA analysis of GCC-specific IgG antibody responses in GCC+/+ (+/+) or GCC-/- (-/-) C57BL/6 mice 14 days after immunization with GCC-AV or Control-AV. Data indicate means of N=3 mice per group at reciprocal serum dilutions of 25, 50, 100 and 200 (*** P<0.001, two-way ANOVA). Data are representative of three independent experiments. D, ELISA analysis of AV-specific IgG antibody responses in naïve GCC+/+ (+/+) or GCC-/- (-/-) C57BL/6 mice or 10-14 days after immunization with AV. Data indicate means of N=4 AV-immunized mice per genotype or pooled samples of three control-immunized mice per genotype at reciprocal serum dilutions of 100, 200, 400 and 800 (*** P <0.001, # P >0.1, two-way ANOVA). Error bars in A-D indicate standard deviation.

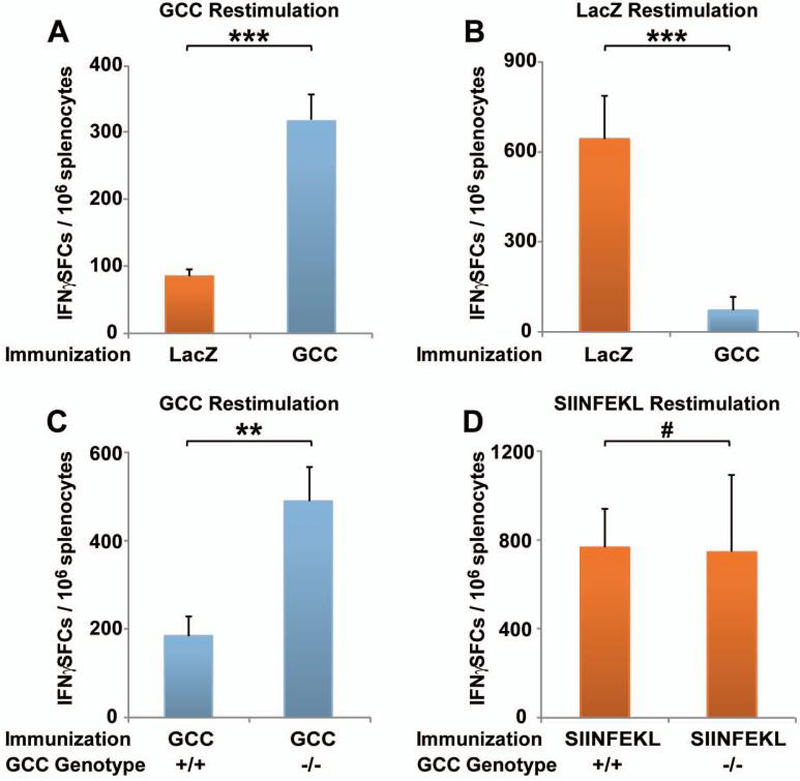

To measure CD8+ T cell responses, mice were immunized with GCC-AV or LacZ-AV and GCC or β-galactosidase -specific CD8+ T cell responses were measured 10 days later upon ex vivo recognition of GCC or β-galactosidase -expressing colon cancer cells. In contrast to CD4+ T cell and antibody responses in GCC+/+ mice, GCC-specific CD8+ T cell responses were generated in GCC+/+ mice, revealed by specific recognition of GCC, but not β-galactosidase, -expressing cells upon GCC-AV immunization (Fig. 2A) and specific recognition of β-galactosidase, but not GCC, -expressing cells upon LacZ-AV immunization (Fig. 2B). Responses to GCC-AV immunization were attenuated in GCC+/+, compared to GCC-/-, mice (Fig. 2C) reflecting partial CD8+ T cell tolerance in GCC+/+ mice. Tolerance was GCC-specific since CD8+ T cell responses to the ovalbumin257-264 epitope SIINFEKL were equivalent in GCC+/+ and GCC-/- mice (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. GCC-specific CD8+ T cell responses.

A, GCC-specific CD8+ T cell responses in GCC+/+ C57BL/6 mice following LacZ-AV (control) or GCC-AV immunization, measured by IFNγ ELISpot employing GCC-expressing colorectal cancer cells as stimulators. B, βgalactosidase-specific CD8+ T cell responses in GCC+/+ C57BL/6 mice following LacZ-AV or GCC-AV (control) immunization, measured by IFNγ ELISpot employing β-galactosidase-expressing colorectal cancer cells as stimulators. Data in A and B indicate pooled analysis of N=2 mice per group, and are representative of six independent experiments (*** P <0.001, two-sided Student's t test). C, GCC-specific CD8+ T cell responses in GCC+/+ (+/+) and GCC-/- (-/-) C57BL/6 mice following GCC-AV immunization, measured by IFNγ ELISpot as in A. Data indicate pooled analysis of N=2 mice per group, and are representative of two independent experiments (** P <0.01, two-sided Student's t test). D, SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cell responses in GCC+/+ (+/+) and GCC-/- (-/-) C57BL/6 mice following NP/SIINFEKL-AV immunization, measured by IFNγ ELISpot upon restimulation with SIINFEKL-expressing stimulator cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments examining SIINFEKL or βgalactosidase -specific responses (# P >0.9, two-sided Student's t test). Error bars in A-D indicate standard deviation.

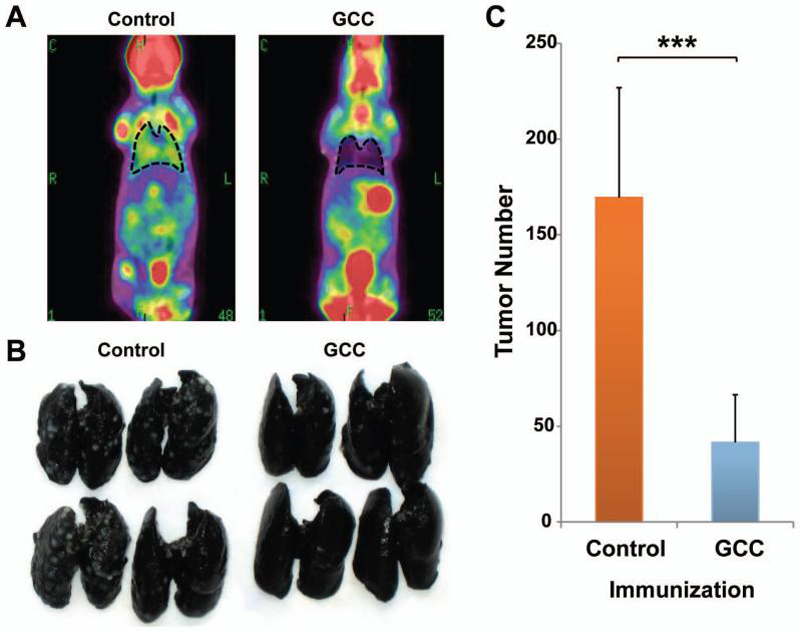

GCC immunization induces antitumor immunity opposing parenchymal metastases

Mice were immunized with GCC-AV or Control-AV, followed 7 days later by intravenous challenge with GCC-expressing CT26 colon cancer cells. Tumor burden revealed by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/microCT was nearly eliminated in GCC-immunized mice compared to control immunized mice (Fig. 3A). Indeed, the number of tumors was reduced ~75% in GCC, compared to control, -immunized mice (p<0.001; Fig. 3B and C). Induction of CD8+ T cell, but not CD4+ T cell or antibody responses to GCC (Fig. 1 and 2), underscores the importance of lineage-specific immune effector cell responses in mediating GCC-targeted antitumor immunity.

Figure 3. GCC-specific immunotherapy against colon cancer metastases in lung.

BALB/c mice were immunized with Control-AV or GCC-AV and then challenged with 5×105 CT26-GCC cells by tail vein injection 7 days later. A, on day 14 after challenge, metastases were visualized by PET/microCT. Images indicate merged PET and microCT images and lungs are outlined for clarity. Images are representative of N=5-7 mice per immunization. B, lungs were removed and stained with India ink to visualize lung nodules. C, lung nodules were enumerated upon visual inspection. Data indicate means of N=12 mice per immunization (*** P <.001, two-sided Student's t test). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

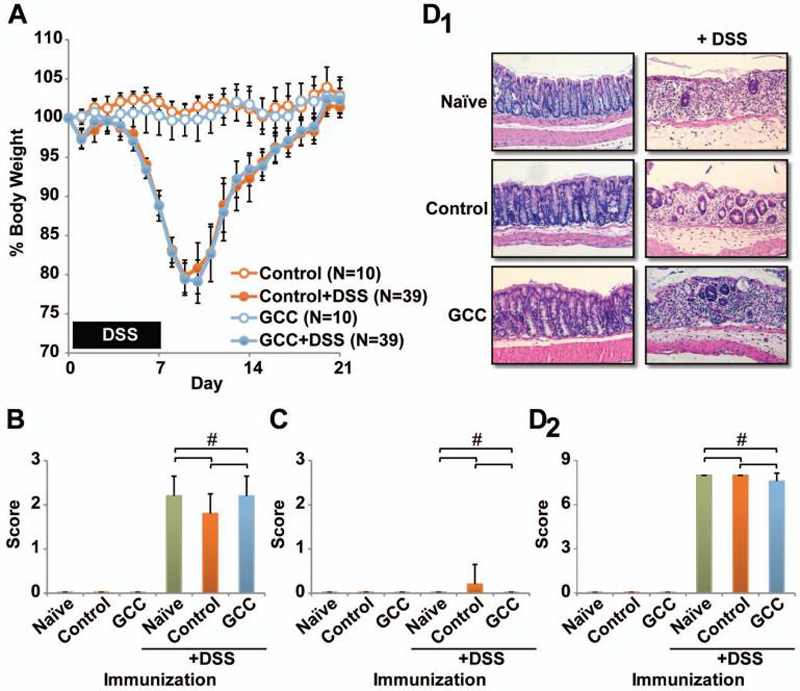

GCC immunization does not amplify inflammatory bowel disease

Despite the generation of CD8+ T cell responses to GCC and effective antitumor immunity, mice immunized with GCC-AV were without clinical signs of intestinal inflammation including diarrhea, rectal bleeding and weight loss. Moreover, they were free of autoimmune inflammation by histology. To determine the impact of GCC-targeted immunity on inflammatory bowel disease, mice were immunized with GCC-AV or Control-AV, followed by GCC-RV or Control-RV and GCC-VV or Control-VV at 28 day intervals. Indeed, while this heterologous prime-boost regimen induces maximum antitumor immunity (5), it was without effect on autoimmunity for up to 119 days beyond the initiation of immunization (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 1-3). Following the final immunization, mice were administered 4% DSS in drinking water ad libitum for 7 days and, subsequently, weights were monitored as a marker of inflammatory bowel disease (Fig. 4A). Preliminary experiments established dose-dependent disease upon DSS administration and defined 4% DSS as inducing moderate disease (data not shown). Control and GCC -immunized mice were without signs of inflammatory bowel disease, maintained weight (Fig. 4A) and remained free of gross or histological evidence of disease (Fig. 4B, C and D; Supplementary Fig. 3). In contrast, DSS treatment of control and GCC -immunized mice induced pronounced weight loss, achieving a nadir at about day 9 followed by complete recovery at ~14 days after discontinuing DSS (Fig. 4A). Importantly, weight loss and recovery were identical in control and GCC -immunized mice (Fig. 4A; P >0.05 Bonferroni's multiple comparison test on area the under the curve values). Moreover, weight changes in immunized groups were similar to those in naïve mice, confirming that viral immunization did not impact disease (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 4. GCC immunization does not intensify mucosal autoimmunity in experimental colitis.

A, female C57BL/6 mice were immunized with Control-AV or GCC-AV and boosted sequentially with RV and VV at 28 day intervals. Four days later, mice were treated with a 7 day course of 4% DSS ad libitum in the drinking water, followed by normal water. Mouse weights were monitored daily. Data indicate means and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals (P >0.05 Bonferroni's multiple comparison's test on area under the curve (AUC) values, Control vs. GCC -immunized DSS treatment groups, Supplementary Fig. 2). B-D, some mice were euthanized on day 9 for examination of disease markers including diarrhea (B), fecal blood (C) and histology (D). Images in D1 are representative sections from treated mice and D2 indicates histological scores from treated mice. Data in B-D indicate means of N=5 mice per group and error bars indicate standard deviation (# P >0.05 Bonferroni's multiple comparison test).

Colons were collected from mice 9 days after initiating DSS, examined and processed for histology (Fig. 4D; Supplementary Fig. 3). While naïve and immunized mice in the absence of DSS had normal stool, all groups receiving DSS experienced diarrhea (Fig. 4B). Consistent with previous observations in which intestinal bleeding declines by about day 9 (29), fecal blood was not detected in any group (Fig. 4C). Histology confirmed that inflammation and epithelial damage were virtually identical in naïve, control, and GCC -immunized groups (Fig. 4D; Supplementary Fig. 3). Moreover, immunization during, rather than prior to, DSS-induced colitis also had no affect on disease severity (Supplementary Figs. 1-3). Importantly, this first examination of systemic immunity to intestinal antigens in the context of fulminant inflammatory bowel disease suggests that autoimmunity and acute inflammation are not contraindications to immunotherapy directed to cancer mucosa antigens.

GCC immunization does not promote colon tumorigenesis

The APC gene is mutated early in >80% of sporadic human colorectal cancers and its germline mutation underlies the inherited intestinal neoplastic syndrome familial adenomatous polyposis, establishing APC mutation as an early event in human colorectal tumorigenesis (30). Moreover, mice heterozygous for mutant APC (APCmin/+) develop intestinal polyps and are the most frequently used model of colorectal tumorigenesis (31). Here, tumorigenesis in APCmin/+ mice was examined following control or GCC -based immunization. Again, the heterologous prime-boost regimen was employed to maximize GCC-specific immune responses. APCmin/+ mice were immunized with control or GCC-AV, RV and VV at 4, 8 and 12 weeks of age, respectively, and tumor burden quantified 2 weeks later. Unlike humans, APCmin/+ mice develop tumors in small and large intestine (31). Tumorigenesis in small (Fig. 5A, B) and large (Fig. 5C) intestine in control and GCC -immunized mice was comparable, reflected by histolopathology (Fig. 5A) and tumor burden (Fig. 5B, C). Histology confirmed that tumors were adenomatous polyps in both control and GCC -immunized APCmin/+ mice and did not progress to invasive carcinoma (Fig. 5A).

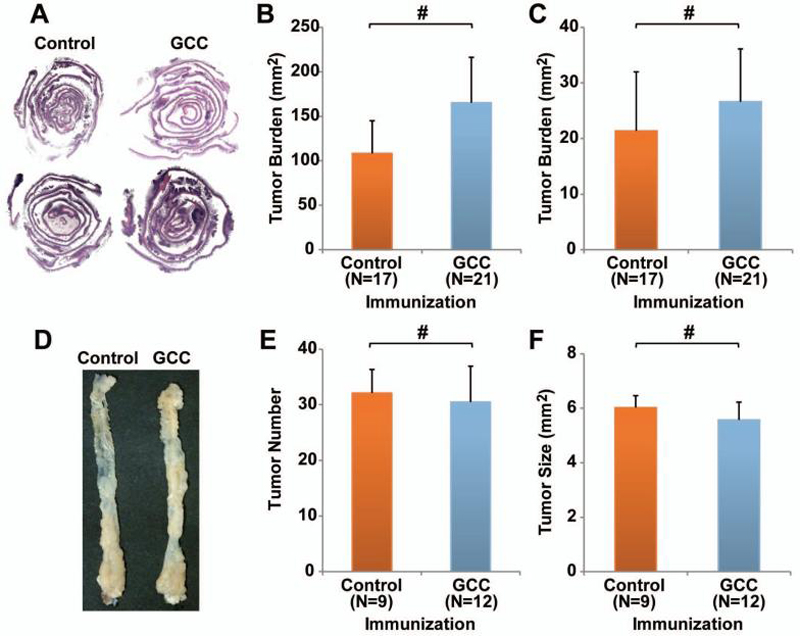

Figure 5. GCC-specific immunization does not amplify tumorigenesis in genetic and inflammatory models of colorectal cancer.

A-C, APCmin/+ C57BL/6 mice were immunized with Control-AV or GCC-AV and boosted sequentially with RV and VV at 28 day intervals beginning at 4 weeks of age. Two weeks after the final immunization intestines were collected, examined by histology (A) and tumor burden was quantified in small (B) and large intestine (C). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals (# P >0.05 two-sided Welch's t test). D-F, female C57BL/6 mice were immunized with Control-AV or GCC-AV and boosted sequentially with RV and VV at 28 day intervals beginning at 6 weeks of age. The procarcinogen AOM was administered 3 days before the final immunization. Seven days later, 3 cycles of DSS were initiated with 14 days of by histology for epithelial damage and inflammation. # P >0.05 Bonferroni's multiple comparison test.

These observations were extended to colon cancer associated with inflammatory bowel disease, employing the AOM-DSS model of colitis-associated colorectal cancer. AOM is a procarcinogen, which when metabolized forms O6-methylguanine and induces the formation of distal colon tumors in rodents (32). Moreover, repeated exposure of AOM-treated mice to DSS induces chronic inflammation, mimicking human inflammatory bowel disease, and dramatically enhances AOM-induced tumorigenesis (33). Here, mice were immunized with control or GCC-AV, RV and VV at 6, 10 and 14 weeks of age, respectively. A single dose of 15 mg/kg AOM was administered 3 days before the final immunization. The first cycle of 4% DSS initiated 7 days after AOM treatment and was followed by 2 more cycles of 3% DSS with 2 weeks between cycles (24). This regimen produced tumors in 100% of control and GCC -immunized mice (data not shown), specifically restricted to the distal colon (Fig. 5D). As observed in APCmin/+ mice, tumor number (Fig. 5E) and size (Fig. 5F) were identical in control and GCC -immunized mice. Histological analysis of tissue sections revealed similar incidence of carcinoma in situ in control (19.6%) and GCC (25%) -immunized mice (P = 0.5184, Fisher's exact test; Table 1).

Table 1.

Histology of colitis-associated colorectal tumors.

% of histologically confirmed tumors

P = 0.5184, Fisher's exact test

Discussion

Cancer mucosa antigens comprise an emerging category of self-antigens expressed normally in immunologically privileged mucosal compartments and by tumors originating therein (1, 2, 5). Universal expression of mucosa-restricted antigens by derivative tumors offers a unique solution to the application of self-antigens from immunologically privileged sites to tumor immunotherapy. This approach leverages the established immunological partitioning of systemic and mucosal compartments (3, 4). Expression confined to mucosae restricts antigen access to the systemic compartment, limiting tolerance opposing antitumor immunity. Conversely, asymmetry in signaling across compartments, wherein systemic immune responses rarely extend to mucosae, limits the risk of autoimmune disease following systemic immunization. In that context, immunization with the intestinal cancer mucosa antigen GCC produced lineage-specific immune cell responses in the systemic compartment, comprising CD8+ T, but not CD4+ T or B, cells. Lineage-specific tolerance reflects thymic and/or peripheral mechanisms, rather than antigenicity, since GCC-/- mice responded to GCC in all arms of the adaptive immune system, while in GCC+/+ mice, GCC elicited only CD8+ T cell responses. Incomplete systemic tolerance to GCC presumably reflects anatomical, functional and immunological compartmentalization wherein sequestration of mucosal antigens provides insufficient antigen for complete systemic tolerance (34, 35). Importantly, CD8+ T cell responses to GCC alone were sufficient for immunoprophylaxis, and a single immunization with GCC-AV dramatically reduced pulmonary colon cancer metastases.

There remains an unresolved issue regarding autoimmunity surrounding the use of self-antigens generally, and cancer mucosa antigens specifically, as immunotherapeutic targets (6-8). Immune effectors to self-antigens could amplify autoimmune disease and chronic inflammation which, in turn, promotes carcinogenesis (9). With respect to intestinal cancer mucosa antigens, immune effectors targeting mucosal antigens could potentiate inflammatory bowel disease and/or tumorigenesis, reflecting disruption of normal mucosal barriers creating novel effector access to compartmentalized antigens, amplifying chronic inflammation. Those considerations notwithstanding, immunization of mice with GCC activated systemic CD8+ T cell responses that, while mediating effective parenchymal anti-metastatic colon cancer immunity, spared GCC-expressing intestinal epithelium from autoimmune disease. Further, systemic GCC immunity induced by a heterologous prime-boost regimen producing maximum effector responses (5) did not influence fulminant intestinal inflammation associated with chemically-induced colitis. Moreover, GCC immunity failed to promote intestinal carcinogenesis reflecting germline mutations in a key tumor suppressor or chronic inflammation. These studies, which are the first to examine the impact of systemic immunity to an intestine-specific self-antigen on inflammatory bowel disease or inflammation-associated colon tumorigenesis, support the safety of GCC immunization in patients at risk for inflammatory bowel disease or hereditary colorectal cancer. Indeed, GCC immunization has substantial translational potential, reflecting the universal expression of GCC in metastatic human colorectal cancer (14-16). While GCC immunogenicity has not yet been explored in patients, studies here reveal uncoupling of systemic antitumor immunity and intestinal autoimmunity through immune compartmentalization and support examination of GCC immunotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer.

Preservation of immune compartmentalization and tissue integrity in the face of mucosa-targeted immune effector cells and fulminant barrier disruption likely reflects the convergence of parallel homeostatic mechanisms. Compartmentalization is supported by tissue-restricted lymphocyte recirculation mediated by chemokine and adhesion molecules, particularly the interactions of addressins, integrins and selectins, which define tissue-specific lymphocyte migration (1, 36-38). The local lymphoid microenvironment imprints new circulation patterns during activation, and effector T cells from mesenteric lymph nodes home to the gut wall, lamina propria, Peyer's patches, and mesenteric lymph nodes while those from peripheral lymph nodes migrate to the spleen and peripheral lymph nodes (38). Moreover, the lineage specificity of effector responses to GCC may be particularly advantageous since autoreactive CD4+ T cells are more efficient mediators of autoimmunity than CD8+ T cells. Thus, CD4+ T cells targeted to a gastric self antigen (39) or commensal bacterial antigen (40) induce autoimmunity in mice. Also, experimental autoimmune diseases such as autoimmune encephalomyelitis (41), thyroiditis (42), colitis (43) and oophritis (44) are CD4+ T cell-mediated. By contrast, CD8+ T cells are infrequent mediators of autoimmune disease, and CD8+ T cell-mediated colitis has been reported in only one model, requiring adoptive transfer of large numbers of transgenic CD8+ T cells (45). Further, in humans, MHC II genes provide significant disease susceptibility, and HLA-DQ2/DR3, HLA-DQ6/DR2, and HLA-DQ8/DR4 haplotypes are associated with 90% of autoimmune disease (46).

The present results have substantial implications for the control of metastatic colorectal cancer in patients. The majority of colorectal cancer cases are sporadic, reflecting environmental and genetic risk factors (25). However, of the ~1 million patients developing colorectal cancer worldwide, ~2% are associated with inflammatory bowel disease and ~5-10% reflect the inherited syndromes hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) (25). These diseases are associated with a cancer penetrance of ~20% in inflammatory bowel disease and 70-100% in hereditary cancer syndromes (25). Indeed, prophylactic colectomy is routinely employed in those patients at greatest risk for developing colorectal cancer. Therefore, prophylactic GCC-specific immunization may be a useful adjunct for cancer control in these populations. While immunization will not prevent the development of primary tumors (Fig. 5), GCC-based immunity could protect against systemic metastases. Importantly, GCC-targeted immunity provided effective anti-metastatic therapy without exacerbating intestinal inflammation or primary carcinogenesis, suggesting that cancer mucosa antigen immunotherapy is not contraindicated in patients with inflammatory bowel disease or inherited colorectal cancer syndromes.

Interestingly, results here contrast with prior studies examining immunotherapy targeting self-antigens in mouse models of intestinal carcinogenesis (47-49). While mechanisms underlying these differences remain to be defined, immune responses in earlier studies were characterized by antibody production, in addition to T cell induction. Antibodies have established efficacy in animal models and humans which may extend to primary colorectal tumorigenesis. Indeed, cetuximab (Eribitux, anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody), bevacizumab (Avastin, anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody), and trastuzumab (Herceptin, anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody) provide clinically-important antitumor efficacy against various tumors. Moreover, antitumor effects induced by immunization against 5T4, a human oncofetal antigen, appear to be mediated exclusively by antibodies (50). In that context, GCC-specific immunization does not induce IgG responses in GCC+/+ mice, the absence of which may restrict efficacy against primary tumors. Studies employing passive transfer of serum from immunized GCC-/- mice to APCmin/+ GCC+/+ mice may reveal primary antitumor efficacy that is absent in the current immunization paradigm which will inform the development of the next generation of immunization regimens that activate both CD8+ T cell and antibody responses.

GCC-targeted immunity which protects against parenchymal colon cancer metastases did not exacerbate inflammatory bowel disease or promote inflammation- or genetically-induced intestinal carcinogenesis. These observations support the utility of GCC-targeted immunotherapy for cancer prevention and control in patients at risk for developing systemic metastases, including those with inflammatory bowel disease, hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes, and sporadic colorectal cancer. Moreover, GCC-based vaccines could be applied to patients with esophageal and gastric cancer, reflecting the role of intestinal metaplasia and the associated novel ectopic expression of that antigen in those malignancies (15). Beyond the GI tract, the present observations suggest the utility and safety of exploiting immunological compartmentalization to achieve anti-metastatic therapy in tumors originating from other mucosae including oral, respiratory, mammary, and urogenital for the treatment of cancers of the head and neck, lung, breast, vagina and bladder, respectively. Indeed, the established principles of immune compartmentalization in the context of the present results with GCC underscore the importance of defining the generalizability of cancer mucosa antigens as targets for immunotherapy of mucosa-derived tumors (1, 2, 5).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: The National Institutes of Health (CA75123, CA95026) and Targeted Diagnostic and Therapeutics Inc. (to S.A.W.); Measey Foundation Fellowship (to A.E.S.); SAW is the Samuel M.V. Hamilton Endowed Professor.

References

- 1.Snook AE, Eisenlohr LC, Rothstein JL, Waldman SA. Cancer Mucosa Antigens as a Novel Immunotherapeutic Class of Tumor-associated Antigen. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;82:734–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snook AE, Stafford BJ, Eisenlohr LC, Rothstein JL, Waldman SA. Mucosally restricted antigens as novel immunological targets for antitumor therapy. Biomarkers in Medicine. 2007;1:187–202. doi: 10.2217/17520363.1.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belyakov IM, Ahlers JD, Brandwein BY, et al. The Importance of Local Mucosal HIV-Specific CD8+ Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes for Resistance to Mucosal Viral Transmission in Mice and Enhancement of Resistance by Local Administration of IL-12. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:2072–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI5102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevceva L, Abimiku AG, Franchini G. Targeting the mucosa: genetically engineered vaccines and mucosal immune responses. Genes Immun. 2000;1:308–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snook AE, Stafford BJ, Li P, et al. Guanylyl Cyclase C-Induced Immunotherapeutic Responses Opposing Tumor Metastases Without Autoimmunity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:950–61. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganss R, Limmer A, Sacher T, Arnold B, Hammerling GJ. Autoaggression and tumor rejection: it takes more than self-specific T-cell activation. Immunol Rev. 1999;169:263–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilboa E. The risk of autoimmunity associated with tumor immunotherapy. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:789–92. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pardoll DM. Inducing autoimmune disease to treat cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5340–2. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel CT, Schreiber K, Meredith SC, et al. Enhanced growth of primary tumors in cancer-prone mice after immunization against the mutant region of an inherited oncoprotein. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1945–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.11.1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalerba P, Maccalli C, Casati C, Castelli C, Parmiani G. Immunology and immunotherapy of colorectal cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;46:33–57. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(02)00159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blattman JN, Greenberg PD. Cancer immunotherapy: a treatment for the masses. Science. 2004;305:200–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1100369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scanlan MJ, Gure AO, Jungbluth AA, Old LJ, Chen YT. Cancer/testis antigens: an expanding family of targets for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 2002;188:22–32. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucas KA, Pitari GM, Kazerounian S, et al. Guanylyl cyclases and signaling by cyclic GMP. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:375–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrithers SL, Barber MT, Biswas S, et al. Guanylyl cyclase C is a selective marker for metastatic colorectal tumors in human extraintestinal tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14827–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birbe R, Palazzo JP, Walters R, Weinberg D, Schulz S, Waldman SA. Guanylyl cyclase C is a marker of intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:170–9. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulz S, Hyslop T, Haaf J, et al. A validated quantitative assay to detect occult micrometastases by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction of guanylyl cyclase C in patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4545–52. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soderholm JD, Peterson KH, Olaison G, et al. Epithelial permeability to proteins in the noninflamed ileum of Crohn's disease? Gastroenterology. 1999;117:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70551-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandwein SL, McCabe RP, Cong Y, et al. Spontaneously colitic C3H/HeJBir mice demonstrate selective antibody reactivity to antigens of the enteric bacterial flora. J Immunol. 1997;159:44–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada Y, Marshall S, Specian RD, Grisham MB. A comparative analysis of two models of colitis in rats. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1524–34. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91710-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stein J, Ries J, Barrett KE. Disruption of intestinal barrier function associated with experimental colitis: possible role of mast cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:G203–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.1.G203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zisman TL, Rubin DT. Colorectal cancer and dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2662–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itzkowitz SH, Harpaz N. Diagnosis and management of dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1634–48. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohonen-Corish MR, Daniel JJ, te Riele H, Buffinton GD, Dahlstrom JE. Susceptibility of Msh2-deficient mice to inflammation-associated colorectal tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2092–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, et al. IKKbeta links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell. 2004;118:285–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weitz J, Koch M, Debus J, Hohler T, Galle PR, Buchler MW. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:153–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17706-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li P, Schulz S, Bombonati A, et al. Guanylyl cyclase C suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis by restricting proliferation and maintaining genomic integrity. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:599–607. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plesa G, Snook AE, Waldman SA, Eisenlohr LC. Derivation and Fluidity of Acutely Induced Dysfunctional CD8+ T Cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:5300–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ito R, Shin-Ya M, Kishida T, et al. Interferon-gamma is causatively involved in experimental inflammatory bowel disease in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;146:330–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melgar S, Karlsson A, Michaelsson E. Acute colitis induced by dextran sulfate sodium progresses to chronicity in C57BL/6 but not in BALB/c mice: correlation between symptoms and inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G1328–38. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00467.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Segditsas S, Tomlinson I. Colorectal cancer and genetic alterations in the Wnt pathway. Oncogene. 2006;25:7531–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taketo MM. Mouse models of gastrointestinal tumors. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:355–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boivin GP, Washington K, Yang K, et al. Pathology of mouse models of intestinal cancer: consensus report and recommendations. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:762–77. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okayasu I, Ohkusa T, Kajiura K, Kanno J, Sakamoto S. Promotion of colorectal neoplasia in experimental murine ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1996;39:87–92. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurts C, Miller JF, Subramaniam RM, Carbone FR, Heath WR. Major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted cross-presentation is biased towards high dose antigens and those released during cellular destruction. J Exp Med. 1998;188:409–14. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ando K, Guidotti LG, Cerny A, Ishikawa T, Chisari FV. CTL access to tissue antigen is restricted in vivo. J Immunol. 1994;153:482–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berlin C, Berg EL, Briskin MJ, et al. Alpha 4 beta 7 integrin mediates lymphocyte binding to the mucosal vascular addressin MAdCAM-1. Cell. 1993;74:185–95. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90305-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johansson-Lindbom B, Svensson M, Wurbel MA, Malissen B, Marquez G, Agace W. Selective generation of gut tropic T cells in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT): requirement for GALT dendritic cells and adjuvant. J Exp Med. 2003;198:963–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kunkel EJ, Butcher EC. Chemokines and the tissue-specific migration of lymphocytes. Immunity. 2002;16:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laurie KL, Van Driel IR, Zwar TD, Barrett SP, Gleeson PA. Endogenous H/K ATPase beta-subunit promotes T cell tolerance to the immunodominant gastritogenic determinant. J Immunol. 2002;169:2361–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kullberg MC, Andersen JF, Gorelick PL, et al. Induction of colitis by a CD4+ T cell clone specific for a bacterial epitope. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15830–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2534546100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pettinelli CB, McFarlin DE. Adoptive transfer of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in SJL/J mice after in vitro activation of lymph node cells by myelin basic protein: requirement for Lyt 1+ 2- T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1981;127:1420–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braley-Mullen H, Sharp GC, Medling B, Tang H. Spontaneous autoimmune thyroiditis in NOD.H-2h4 mice. J Autoimmun. 1999;12:157–65. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1999.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leithauser F, Krajina T, Trobonjaca Z, Reimann J. Early events in the pathogenesis of a murine transfer colitis. Pathobiology. 2002;70:156–63. doi: 10.1159/000068148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lou YH, Borillo J. Migration of T cells from nearby inflammatory foci into antibody bound tissue: a relay of T cell and antibody actions in targeting native autoantigen. J Autoimmun. 2003;21:27–35. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(03)00081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Z, Lefrancois L. Intestinal epithelial antigen induces mucosal CD8 T cell tolerance, activation, and inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2004;173:4324–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friese MA, Jones EY, Fugger L. MHC II molecules in inflammatory diseases: interplay of qualities and quantities. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:559–61. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iinuma T, Homma S, Noda T, Kufe D, Ohno T, Toda G. Prevention of gastrointestinal tumors based on adenomatous polyposis coli gene mutation by dendritic cell vaccine. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1307–17. doi: 10.1172/JCI17323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greiner JW, Zeytin H, Anver MR, Schlom J. Vaccine-based therapy directed against carcinoembryonic antigen demonstrates antitumor activity on spontaneous intestinal tumors in the absence of autoimmunity. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6944–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeytin HE, Patel AC, Rogers CJ, et al. Combination of a poxvirus-based vaccine with a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor (celecoxib) elicits antitumor immunity and long-term survival in CEA.Tg/MIN mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3668–78. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harrop R, Connolly N, Redchenko I, et al. Vaccination of Colorectal Cancer Patients with Modified Vaccinia Ankara Delivering the Tumor Antigen 5T4 (TroVax) Induces Immune Responses which Correlate with Disease Control: A Phase I/II Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3416–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.