Abstract

Salmonella is a widespread zoonotic enteropathogen that causes gastroenteritis and fatal typhoidal disease in mammals. During systemic infection of mice, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium resides and replicates in macrophages within the “Salmonella-containing vacuole” (SCV). It is surprising that the substrates and metabolic pathways necessary for growth of S. Typhimurium within the SCV of macrophages have not been identified yet. To determine whether S. Typhimurium utilized sugars within the SCV, we constructed a series of S. Typhimurium mutants that lacked genes involved in sugar transport and catabolism and tested them for replication in mice and macrophages. These mutants included a mutant with a mutation in the pfkAB-encoded phosphofructokinase, which catalyzes a key committing step in glycolysis. We discovered that a pfkAB mutant is severely attenuated for replication and survival within RAW 264.7 macrophages. We also show that disruption of the phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase system by deletion of the ptsHI and crr genes reduces S. Typhimurium replication within RAW 264.7 macrophages. We discovered that mutants unable to catabolize glucose due to deletion of ptsHI, crr, and glk or deletion of ptsG, manXYZ, and glk showed reduced replication within RAW 264.7 macrophages. This study proves that S. Typhimurium requires glycolysis for infection of mice and macrophages and that transport of glucose is required for replication within macrophages.

Salmonella is a common zoonotic enteropathogen that causes gastroenteritis or fatal systemic disease in mammals, including humans, cattle, and pigs. Typhoidal Salmonella serovars, such as Salmonella enterica serovars Typhi and Paratyphi, cause an estimated 20 million cases of salmonellosis and 200,000 human deaths worldwide per year (9). Salmonella infections occur as a result of ingestion of contaminated food and water. S. enterica serovar Typhimurium causes a self-limited gastroenteritis in humans and results in a systemic typhoid-like disease in mice. Infected mice are frequently used as an experimental model for human typhoid diseases (56). During systemic infections, S. Typhimurium penetrates the small intestine barrier and gains access to the mesenteric lymph nodes, where the bacteria are engulfed by phagocytic cells, such as macrophages. Once inside a macrophage, S. Typhimurium is compartmentalized into an intracellular phagosome which is modified to become the “Salmonella-containing vacuole.” The Salmonella-containing vacuole acts as a shield that prevents both lysosomal fusion and exposure to host cell antimicrobial agents (1, 21). The Salmonella bacteria must acquire nutrients for replication within macrophages.

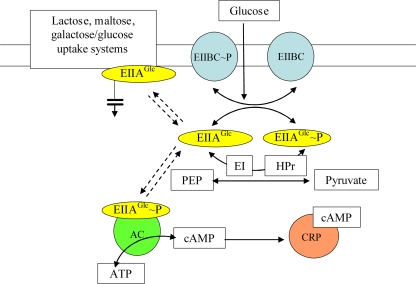

S. Typhimurium contains a variety of virulence genes, many of which are organized into clusters referred to as Salmonella pathogenicity islands. Much work has focused on characterization of Salmonella pathogenicity genes and the mechanisms by which they facilitate infection (54, 55). In contrast, there is a lack of information regarding the nutritional and metabolic requirements of Salmonella during infection. It has been shown that the complete tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle operates during infection of mice with S. Typhimurium strain SR11 (53). Surprisingly, fatty acid degradation and the glyoxylate shunt are not required to replenish the TCA cycle (53). The same study also showed that S. Typhimurium SR11 does not require gluconeogenesis to exhibit full virulence in BALB/c mice and suggested that SR11 utilizes as-yet-unidentified sugars for growth during infection of BALB/c mice (53). We have been investigating which substrates and metabolic pathways are required by Salmonella for infection of cultured murine macrophages and for systemic infection of mice. Our work has focused on the central catabolic pathway of glycolysis, which is the sequence of catabolic reactions that converts sugars into pyruvate with concomitant synthesis of ATP and NADH (18). Glycolysis is the foundation of both aerobic and anaerobic respiration and is found in nearly all organisms (18). Many of the carbohydrates catabolized by glycolysis are imported via the phosphotransferase (PTS) system (40). The PTS system transfers phosphate from the glycolytic intermediate phosphoenolpyruvate to a cascade of enzymes, ultimately resulting in rapid phosphorylation of the transported sugar (Fig. 1). Briefly, enzyme 1 (E1) transfers a phosphate group from phosphoenolpyruvate to enzyme 2 (EII) via HPr, and enzyme 2 transports and phosphorylates the incoming sugar (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Mechanism underlying inducer exclusion in enteric bacteria. (Modified from reference 15 with permission.) The transport of PTS carbohydrates, including glucose, results in net dephosphorylation of the PTS proteins and inducer exclusion. The dephosphorylated EIIAGlc permease encoded by crr blocks the import of lactose, maltose, and melibiose and the phosphorylation of glycerol by binding to the corresponding transporter or kinase. Phosphorylated EIIAGlc activates adenylate cyclase (AC), which binds to phosphorylated as well as unphosphorylated EIIAGlc. cAMP binds to CRP, which activates the transcription of many genes encoding catabolic enzymes and transport proteins, including ptsG. PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate.

Here we show that the glycolytic pathway is required for intracellular replication of S. Typhimurium in mice and macrophages and that glucose is the major sugar utilized by S. Typhimurium during infection of macrophages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and reagents.

The S. Typhimurium strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains were maintained in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on plates with appropriate antibiotics at the following concentrations; ampicillin (Sigma Aldrich), 50 μg ml−1, chloramphenicol (Cm) (Sigma Aldrich), 12.5 μg ml−1; and kanamycin (Km) (Sigma Aldrich), 50 μg ml−1. M9 minimal medium with 0.4% glucose was used where indicated below. Oligonucleotide primers were purchased from Sigma Genosys or Illumina (California).

TABLE 1.

Primers used to construct S. Typhimurium gene deletion mutants

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| pfkaredf | CAATAGATTTCATTTTGCATTCCAAAGTTCAGAGGTAGTCGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| pfkaredr | AGGCCTGATAAGCGTAGCGCCATCAGGCGCGCAAAAACAACATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

| pfkbredf | ATTAAGTGCCAGACTGAAATCAGCCTAACAGGAGGTAACGGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| pfkbredr | AACCGATTTTCCGTTATCCCCCTCGGCGAGGGGGAAACGACATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

| ptshredf | TTAGTTCCACAACACTAAACCTATAAGTTGGGGAAATACAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| crrredr | AAATGGCGCCCAAAGGCGCCATTCTTCACTGCGGCAAGAACATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

| glkredf | TGACAAAGACTTATTTTGACTTTAGCGGAGCAGTAGAAGAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| glkredr | CTTTTGTAGGCCGGATAAGGCGTTTATGCCACCATCTGGCCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

| ptsIRevInt1 | GCAGTTCCTGTTTGTAGATTTCAATCTCTTTGCGCAGCGCCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

| crrredf | TCCACGAGATGCGGCCCAATTTACTGCTTAGGAGAAGATCGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| ptsgredf | GAACGTAGAAAAGCACAAATACTCAGGAGCACTCTCAATTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| ptsgredr | GCCGAATGGCTGCCTTAATTCTCCCCAACATCATTACTGCCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

| manxredf | TGTCAAGTTGATGTGTTGACAATAATAAAGGAGGTAGCAAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| manzredr | AAAAAACGGGGCCGTTTGGCCCCGGTAGTGTACAACAGCCCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG |

Mutant construction.

S. Typhimurium mutants were constructed using previously published procedures (11). Briefly, 60-bp oligonucleotides were designed that contained 40 bp at their 5′ end that was homologous to the DNA flanking the target gene to be deleted from the chromosome (Table 2). The oligonucleotides were used to PCR amplify a cassette containing the Km resistance gene carried by plasmid pKD4 or the Cm resistance gene carried by plasmid pKD3 (Table 1) (11). Each resulting PCR product was then transformed by electroporation into S. Typhimurium 4/74 (59) carrying plasmid pKD46 (Table 1). Plasmid pKD46 encoded the λRed recombinase enzyme, which facilitated homologous recombination of the target gene with the PCR product, resulting in complete replacement of the target gene with the Km or Cm resistance gene (11). In order to avoid unwanted genetic recombination events that may have occurred during the original transformation, the Km or Cm resistance cassette from the deleted gene was routinely transferred by P22 transduction into S. Typhimurium wild-type strain 4/74 (24). The transductants were screened on green agar plates to obtain lysogen-free colonies (50). The complete absence of the structural gene(s) was confirmed by DNA sequencing of the deleted regions of the chromosome (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or phenotype | Method of constructiona | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. Typhimurium strains | |||

| 4/74 | Wild-type strain | NA | 59 |

| SL1344 | rpsL hisG | NA | 24 |

| JH3386 | 4/74 ΔpfkA::Km | λRed mutagenesis; pKD4 PCR product obtained using primers pfkaredf and pfkaredr | This study |

| JH3460 | 4/74 ΔpfkB::Cm | λRed mutagenesis; pKD3 PCR product obtained using primers pfkbredf and pfkbredr | This study |

| JH3486 | 4/74 ΔpfkA::Km ΔpfkB::Cm | P22 transduced ΔpfkB::Cm from JH3460 into JH3386 | This study |

| JH3494 | 4/74 Δglk::Km | λRed mutagenesis; pKD4 PCR product obtained using primers glkredf and glkredr | This study |

| JH3501 | 4/74 ΔmanXYZ::Cm | λRed mutagenesis; pKD3 PCR product obtained using primers manxredf and manzredr | This study |

| JH3502 | 4/74 Δcrr::Km | λRed mutagenesis; pKD4 PCR product obtained using primers crrredf and crrredr | This study |

| JH3504 | 4/74 ΔptsG::Cm | λRed mutagenesis; pKD3 PCR product obtained using primers ptsgredf and ptsgredr | This study |

| JH3536 | 4/74 ΔptsHI-crr::Cm | λRed mutagenesis; pKD3 PCR product obtained using primers ptshredf and crrredr | This study |

| JH3537 | 4/74 ΔptsHI::Cm | λRed mutagenesis; pKD3 PCR product obtained using primers ptshredf and ptsIRevInt1 | This study |

| JH3540 | 4/74 ΔptsHI-crr::Cm Δglk::Km | P22 transduced Δglk::Km from JH3494 into JH3536 | This study |

| JH3541 | 4/74 ΔmanXYZ | Transformed JH3501 with pCP20 to excise the Cmr cassette from the chromosome; plasmid was cured from the strain | This study |

| AT1011 | 4/74 ΔptsG::Cm ΔmanXYZ | P22 transduced ΔptsG::Cm from JH3504 into JH3541 | This study |

| AT1012 | 4/74 ΔptsG::Cm Δglk::Km | P22 transduced Δglk::Km from JH3494 into JH3504 | This study |

| AT1013 | 4/74 ΔmanXYZ Δglk::Km | P22 transduced Δglk::Km from JH3494 into JH3541 | This study |

| AT1014 | 4/74 ΔptsG::Cm ΔmanXYZ Δglk::Km | P22 transduced Δglk::Km from JH3494 into AT1013 | This study |

| Plasmids | |||

| pKD46 | λRed recombinase expression plasmid | NA | 11 |

| pKD3 | Cmr cassette-containing plasmid | NA | 11 |

| pKD4 | Kmr cassette-containing plasmid | NA | 11 |

| pCP20 | FLP recombinase expression plasmid | NA | 8 |

| pWSK30 | Apr low-copy-number vector, pSC101 origin of replication | NA | 57 |

| pWSK30::pfkA | Apr low-copy-number vector, pSC101 origin of replication, expresses pfkA | 1,579-bp pfkA1-pfkA2 PCR product cloned into pWSK30 BamHI-HindIII sites | This study |

λRed mutagenesis is described in Materials and Methods. NA, not applicable.

During construction of strain JH3541, the Cm resistance gene was removed via a further recombination event by transforming JH3501 with the FLP recombinase expression plasmid pCP20 (8). The FLP recombinase removed the Cm resistance gene, and the strain was cured of the pCP20 plasmid by growth at 37°C. In the resultant strain, JH3541 (Table 2), the manXYZ genes are completely deleted, and the strain does not contain the Cm resistance cassette (11).

Plasmid construction.

The pfkA gene plus 582 bp of upstream sequence was PCR amplified from S. Typhimurium 4/74 genomic DNA using primers pfkA1 (5′-TTTTAAGCTTGGGTTATCCTGGTACGGTTG) and pfkA2 (5′-TTTTGGATCCGATAAGCGTAGCGCCATCAG). The PCR product was digested with BamHI and HindIII, ligated into the low-copy-number vector pWSK30 (57), and transformed into Escherichia coli strain DH5α by electroporation (58). The resulting plasmid was designated pWSK30::pfkA and was confirmed by DNA sequencing across the multiple-cloning site using primers M13F (5′-CGCCAGGGTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC) and M13R (5′-TCACACAGGAAACAGCTATGAC) (John Innes Centre Genome Laboratory). Plasmids pWSK30 and pWSK30::pfkA were then transformed into 4/74 and JH3486 by electroporation. pWSK30::pfkA was shown to be functional because it restored growth of JH3486 on M9 minimal medium with 0.4% glucose (data not shown).

Macrophage infection assays.

Infection assays with murine macrophages were performed essentially as previously described (26). Briefly, murine macrophages (RAW 264.7; obtained from American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) were grown in minimal essential medium (product no. M2279; Sigma Aldrich) (19) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine (final concentration, 2 mM; Sigma Aldrich), and 1× nonessential amino acids (product no. M7145; Sigma Aldrich). For infection, 1 × 105 macrophage cells were seeded into each well of a 12-well cell culture plate (Corning) and infected with complement-opsonized S. Typhimurium 4/74 and mutant strains at a multiplicity of infection of 1:1 (ratio of bacteria to cells) (26). To minimize Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 expression, bacteria were grown overnight on LB medium plates at 37°C and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before opsonization.

To increase the uptake of Salmonella, plates were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min (Eppendorf 5810R), and this was defined as time zero. After 1 h of phagocytosis, extracellular bacteria were killed by addition of 100 μg ml−1 gentamicin (Sigma). After a further 1 h, the medium was replaced with supplemented minimal essential medium containing 10 μg ml−1 gentamicin. Incubation was continued for 2 h and 18 h after infection. To estimate the amount of intracellular bacteria at each time point, cells were lysed using 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma), and samples were removed to determine viable counts (16). Statistical significance was assessed by using Student's unpaired t test, and a P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Mouse infection assays.

Mouse infection experiments were performed as described previously (38), with some modifications. Liquid S. Typhimurium cultures were grown statically in 50 ml of LB medium (supplemented with an antibiotic if required to maintain the plasmid) at 37°C overnight in 50-ml Falcon tubes (Corning) (3). The following day bacteria were resuspended at a final density of 1 × 104 CFU ml−1 in sterile PBS. Five female BALB/c mice (Charles River U.K. Ltd.) per S. Typhimurium strain were infected with 200 μl of a bacterial suspension via the intraperitoneal (i.p.) route using a final dose of 2 × 103 Salmonella CFU (38). The infection was permitted to proceed for 72 h, and then the mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and the spleens and livers were surgically removed (38). Following homogenization of the organs in a stomacher (Seward Tekmar), serial dilutions of the suspensions in PBS were spread onto LB agar plates, and bacterial CFU were enumerated after overnight incubation at 37°C (3). All animal experiments were approved by the local ethics committee and conducted according to guidelines of the Animal Act 1986 (Scientific Procedures) of the United Kingdom.

RESULTS

Glycolysis is required for intracellular replication and survival of S. Typhimurium in macrophages.

The enzyme phosphofructokinase (Pfk) catalyzes a key committing step in glycolysis and irreversibly converts β-d-fructose-6-phosphate into β-d-fructose-1,6-bisphosphate. In contrast to most glycolytic enzymes, phosphofructokinase is not part of the gluconeogenic pathway and instead is specific for glycolysis (18). The loss of functional phosphofructokinase activity completely blocks glycolysis and prevents growth of S. Typhimurium on sugars as sole carbon sources (18).

In most bacteria phosphofructokinase is encoded by two genes, designated pfkA and pfkB. (44). In order to test whether the glycolytic pathway is required for infection by Salmonella, we first constructed S. Typhimurium strains with complete deletions of the pfkA and pfkB genes (designated JH3386 and JH3460, respectively) and a double mutant strain which lacked both the pfkA and pfkB genes (JH3486). The deletions were verified by DNA sequencing and by growing the strains on M9 minimal medium plates with glucose as the sole carbon source. Both the pfkA and pfkB single-mutant strains, but not the pfkAB strain, were able to grow on glucose as a sole carbon source (data not shown).

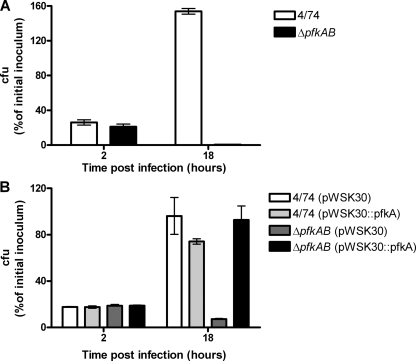

In RAW 264.7 macrophage replication assays neither the pfkA single mutant nor the pfkB single mutant was attenuated for intracellular replication compared to the wild-type strain (data not shown). In contrast, we observed a dramatic 322-fold decrease in the number of intracellular S. Typhimurium ΔpfkAB bacteria compared to the number of wild-type strain bacteria after 18 h of infection of RAW 264.7 macrophages (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the 34-fold decrease in the level of intracellular S. Typhimurium ΔpfkAB bacteria between 2 h and 18 h postinfection suggests that the S. Typhimurium ΔpfkAB strain was unable to survive within RAW 264.7 macrophages (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Glycolysis is required for infection of macrophages. (A) Intracellular replication assays with S. Typhimurium 4/74 wild-type and ΔpfkAB (JH3486) strains during infection of RAW 264.7 macrophages. (B) Complementation of the S. Typhimurium ΔpfkAB strain in RAW 264.7 macrophages. The data show the numbers of viable bacteria (expressed as percentages of the initial inoculum) inside the macrophages at 2 h and 18 h after infection. Each bar indicates the statistical mean for three biological replicates, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations.

We next confirmed that the survival and replication defects in macrophages infected with the S. Typhimurium ΔpfkAB strain were due to deletion of the pfkAB genes. We inserted the pfkA gene plus 582 bp of the upstream sequence into the low-copy-number vector pWSK30 (57), transformed the construct into the S. Typhimurium 4/74 and S. Typhimurium ΔpfkAB strains, and performed infection assays with macrophages. As shown in Fig. 2B, the cloned copy of the pfkA gene fully complemented the ΔpfkAB deletion in JH3486 during infection of macrophages and restored intracellular replication of the S. Typhimurium ΔpfkAB strain containing pWSK30::pfkA to wild-type levels. We observed that the 4/74(pWSK30::pfkA) strain was slightly attenuated for replication compared to 4/74 containing the empty vector (Fig. 2B), which may indicate that excessive Pfk activity is detrimental to S. Typhimurium replication within macrophages.

Glycolysis is required for successful infection of mice.

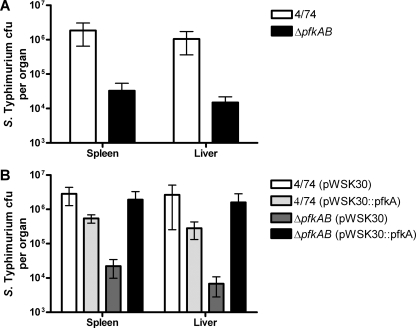

During murine infections, S. Typhimurium disseminates systemically from the Peyer's patches to the liver and spleen, where it continues to grow within macrophages (20, 43, 48). The inability of the S. Typhimurium ΔpfkAB strain to replicate within macrophages suggested that phosphofructokinase might play a role in the mouse typhoid infection model. We therefore infected BALB/c mice with the S. Typhimurium ΔpfkAB mutant (JH3486) and the wild-type strain via the i.p. route. Salmonella bacteria were recovered from the spleens and livers of mice and enumerated after 72 h of infection. The results demonstrated that the S. Typhimurium ΔpfkAB mutant is severely attenuated (approximately 100-fold) compared to the wild-type strain in the spleens and livers of infected mice (Fig. 3A). Mice infected with the S. Typhimurium ΔpfkAB strain exhibited slight ruffling of the fur after 72 h, suggesting that an immune response may have been elicited, but otherwise were asymptomatic, whereas mice infected with the S. Typhimurium wild-type strain showed severe symptoms of systemic typhoid disease after 72 h. These results indicate that glycolysis is an essential central metabolic pathway required for successful infection of mice by S. Typhimurium.

FIG. 3.

Glycolysis is required for infection of mice. (A) S. Typhimurium 4/74 and ΔpfkAB mutant (JH3486) CFU recovered from spleens and livers at 72 h after i.p. infection of BALB/c mice. (B) Complementation of the S. Typhimurium ΔpfkAB strain in BALB/c mice. Each bar indicates the statistical mean for five biological replicates, and the error bars indicate the standard errors of the means.

To verify that the virulence defect of the glycolysis mutant observed in mice was due to loss of the pfkAB genes and not to a secondary mutation, we complemented the mutation with the pWSK30::pfkA plasmid, which directs synthesis of Pfk-1. We infected female BALB/c mice with the wild type and JH3486, with each strain carrying pWSK30 or pWSK30::pfkA (Fig. 3B). The results showed that, as expected, JH3486 containing the pWSK30 vector was attenuated for infection of the liver and spleen compared to the wild-type strain containing the same plasmid. However, the JH3486 strain containing pWSK30::pfkA was not attenuated for infection of the livers and spleens of infected BALB/c mice compared to the wild-type strain carrying the empty vector. This result confirms that JH3486 is attenuated for infection of mice, most likely because the lack of a functional Pfk enzyme blocks glycolysis. We also observed that wild-type S. Typhimurium expressing pWSK30::pfkA was slightly attenuated for infection of the liver and spleen compared to the wild type expressing the empty vector (Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained with macrophages (Fig. 2B), and this suggests that excessive Pfk activity has a negative impact on S. Typhimurium infection of mice.

Carbohydrate transport is required for intracellular replication of S. Typhimurium in cultured macrophages.

Many different carbon sources (including carbohydrates) can be catabolized by glycolysis. Having confirmed that glycolysis is required for successful infection of mice and macrophages by S. Typhimurium, we investigated which sugars are available to Salmonella during infection by studying sugar transport mutants for defects in virulence. The PTS system of E. coli and S. Typhimurium simultaneously transports and phosphorylates a large number of carbohydrates and is a likely candidate for a system involved in importing the glycolytic substrates required for growth of S. Typhimurium within macrophages (40).

In order to determine the role of the PTS system in transportation of carbohydrates required for intracellular replication of S. Typhimurium in macrophages, we targeted genes encoding components of the PTS system for deletion. The ptsH and ptsI genes encode the HPr and EI proteins, respectively (Fig. 1). The sugar-specific EII domains can be encoded by more than one gene; for example, the glucose-specific EII, EIIABCGlc, is encoded by the crr gene that encodes the EIIA domain, and ptsG that encodes the EIIBC domains (40). The crr gene is cotranscribed with ptsI and ptsH but is expressed primarily from a second promoter located within ptsI that accounts for approximately 80% of crr transcription in the cell (14). EIIAGlc is a multifunctional protein that is an EIIA domain for the transport of glucose, maltose, trehalose, N-acetylmuramic acid, and arbutin/salicin (47). In its dephosphorylated state, EIIAGlc is able to repress other non-PTS transporters involved in lactose, maltose, and galactose/glucose transport via a process known as inducer exclusion (40, 46). In contrast, the phosphorylated EIIAGlc protein (EIIAGlc-P) is known to activate cyclic AMP (cAMP) production via adenylate cyclase (41). The resulting increased levels of cAMP lead to activation of cAMP receptor protein (CRP), which in turn causes increased expression of the catabolite repression regulon (including many metabolic genes involved in ribose, trehalose, galactose, and nucleoside transport) (27, 60).

To determine the importance of the PTS system for S. Typhimurium virulence, we constructed an S. Typhimurium mutant strain (JH3536) that lacks the ptsHI-crr operon. We deleted crr in addition to ptsHI because dephosphorylated EIIAGlc represses several non-PTS transporters via inducer exclusion (13, 33, 35-37, 40, 46, 51) (Fig. 1). The absence of EI and HPr prevents phosphorylation of EIIAGlc, which therefore remains in its unphosphorylated state and inhibits the function of lactose, melibiose, and galactose/glucose transporters (33, 35, 37). To determine whether inducer exclusion might also play a role in S. Typhimurium virulence, we constructed a mutant (JH3537) in which ptsH and the first 1,200 bp of ptsI were deleted but which was still able to transcribe crr from the promoter located in the 3′ end of ptsI. This means that enzymes that are subject to inducer exclusion are always inhibited in JH3537 because EIIAGlc is permanently in the dephosphorylated state.

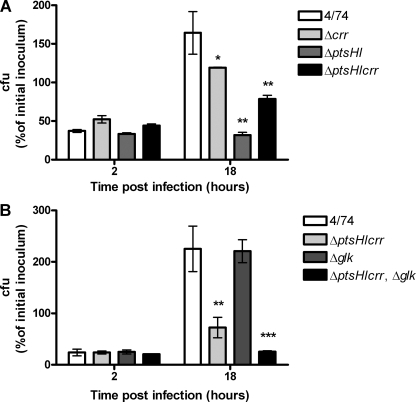

We tested the S. Typhimurium wild-type strain and ΔptsHI-crr (JH3536), ΔptsHI (JH3537), and Δcrr (JH3502) mutants for the ability to replicate within cultured macrophages. As shown in Fig. 4A, the number of recovered CFU of S. Typhimurium wild-type bacteria increased 4.4-fold between 2 and 18 h postinfection. However, the intracellular replication rates of the S. Typhimurium Δcrr, ΔptsHI, and ΔptsHI-crr strains were significantly reduced compared to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 4A). The S. Typhimurium Δcrr strain was partially attenuated for intracellular replication in macrophages (2.3-fold increase). This may indicate that PTS sugars that require the EIIAGlc protein for transport (i.e., glucose, maltose, trehalose, N-acetylmuramic acid, arbutin, and/or salicin) are utilized as carbon sources by S. Typhimurium during macrophage infection. Alternatively, the slight attenuation of the Δcrr mutant could show that EIIAGlc-P is required to promote cAMP production and that this signal molecule interacts with CRP to regulate genes that promote survival and/or replication in macrophages.

FIG. 4.

PTS system is required for S. Typhimurium replication within macrophages. (A) Intracellular replication assay with the S. Typhimurium 4/74, Δcrr (JH3502), ΔptsHI (JH3537), and ΔptsHI-crr (JH3536) strains during infection of RAW 264.7 macrophages. (B) Intracellular replication assay with the S. Typhimurium 4/74, ΔptsHI-crr (JH3536), Δglk (JH3494), and ΔptsHI-crr Δglk (JH3540) strains during infection of RAW 264.7 macrophages. The data show the numbers of viable bacteria (expressed as percentages of the initial inoculum) inside the macrophages at 2 h and 18 h after infection. Each bar indicates the statistical mean for three biological replicates, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations. Significant differences between parental strain 4/74 and the mutant strains are indicated by asterisks, as follows: no asterisk, P > 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001.

The S. Typhimurium ΔptsHI-crr strain was strongly attenuated for replication in macrophages, and the level of this strain increased only approximately 1.8-fold during the experiment. The absence of the HPr and EI subunits in the S. Typhimurium ΔptsHI-crr strain would have prevented all PTS carbohydrates from entering the cell, including those that require EIIAGlc (Fig. 1). Because the S. Typhimurium ΔptsHI-crr strain showed less replication than the S. Typhimurium Δcrr strain within macrophages (Fig. 4A), we deduced that PTS sugars transported independent of EIIAGlc are utilized by S. Typhimurium during infection of macrophages and are important for intracellular replication.

JH3537, the S. Typhimurium ΔptsHI strain that expresses functional EIIAGlc and is permanently subject to the inducer exclusion effect (see above), was more attenuated than the ΔptsHI-crr mutant for replication in macrophages (Fig. 4A). In fact, this mutant did not replicate between 2 h and 18 h postinfection, indicating that it was unable to multiply inside macrophages. Our data show that inducer exclusion regulates the activity of an S. Typhimurium transporter of a substrate available inside macrophages, which could include lactose, melibiose, and glucose/galactose (33, 35, 37). In the case of glucose and galactose, the inducer exclusion-dependent transporter is galactose permease (GalP) (2, 29, 30, 33). GalP also transports glucose (39), and its expression is induced by availability of galactose (7). The abundance of glucose in eukaryotic cells and our previous observation that glucose transport genes are overexpressed by S. Typhimurium in macrophages and HeLa cells (17, 22) led us to investigate glucose utilization by S. Typhimurium in more detail.

Glucose is the major carbohydrate required for intracellular replication of S. Typhimurium in macrophages.

The experiments described above suggested that a carbohydrate that requires the HPr, EI, and EIIAGlc components of the PTS permease system is required for intracellular replication of S. Typhimurium in macrophages. Glucose requires the HPr, EI, and EIIAGlc components for transport in S. Typhimurium but can also be transported into Salmonella via the GalP and MglABC transporter. Following internalization, intracellular glucose is subsequently phosphorylated by glucokinase (25, 32). Glucokinase is encoded by the glk gene, is highly specific for glucose, and does not efficiently phosphorylate related carbohydrates, such as galactose, mannose, or fructose (32). In order to determine whether glucose is required for intracellular growth of S. Typhimurium, we constructed a mutant strain with complete deletions of the ptsHI-crr and glk genes (JH3540). We confirmed that while the ΔptsHI-crr mutant (JH3536) grew on M9 minimal medium containing glucose as a sole carbon source, the S. Typhimurium ΔptsHI-crr Δglk strain (JH3540) was unable to grow under the same conditions (data not shown). In this mutant, glucose that is transported into the cell by GalP and MglABC cannot enter glycolysis because the absence of glucokinase prevents production of glucose-6-phosphate. We performed an infection assay with the S. Typhimurium wild-type, ΔptsHI-crr (JH3536), ΔptsHI-crr Δglk (JH3540), and Δglk (JH3494) strains to determine their abilities to replicate in macrophages (Fig. 4B). The data show that, as expected, the S. Typhimurium Δglk mutant, whose ability to grow on glucose is not affected, replicated as rapidly as the wild-type strain in infected macrophages. The ΔptsHI-crr mutant (JH3536), which cannot transport PTS sugars but can still grow on glucose, was attenuated for intracellular replication compared to the wild-type strain, as observed in the previous experiment (Fig. 4A). However, the S. Typhimurium ΔptsHI-crr Δglk strain (JH3540), which cannot grow on glucose at all, was unable to replicate within macrophages (Fig. 4B), reflecting the phenotype observed for the ΔptsHI mutant (Fig. 4A). As glucokinase is highly specific for glucose, this result strongly suggests that glucose is the most important nutrient required for intracellular replication of S. Typhimurium in macrophages. However, given the pleiotropic effects of the ptsHI and crr mutations on cAMP production and catabolite repression, it was possible that some unknown factor regulated by CRP-cAMP could be responsible for the attenuation seen in these mutants. We therefore decided to test mutants in which glucose utilization is specifically affected to determine the impact of their mutations on virulence.

In order to confirm that glucose was definitely utilized by S. Typhimurium during infection of macrophages, we disrupted glucose transport and catabolism. To our knowledge, there are four separate transporters for glucose in S. Typhimurium, the IIABCGlc and IIABCMan PTS systems (52), GalP (23, 39), and the methylgalactose ABC transporter (MglABC) (12, 23).

The IIABCGlc PTS system, encoded by ptsG and crr, is the primary PTS transporter for glucose, and its Km for glucose is 3 to 10 μM (34, 52). The IIABCDMan PTS system is encoded by manXYZ and is a PTS transporter that has broad specificity for many sugars, including mannose, glucose, 2-deoxyglucose, N-acetylglucosamine, N-acetylmannosamine, and galactosamine (6, 42, 52); it is thought to be a scavenger system for amino sugars generated during cell wall synthesis and degradation, and it is an important glucose uptake system in S. Typhimurium. Glucose can also be transported into the cell via GalP (23, 39). MglABC is an ABC transporter that is capable of transporting four carbohydrates, including glucose (5, 12, 45, 49). However, glucose entering the cell via MglABC or GalP must be phosphorylated by glucokinase, IIABCGlc, or IIABCDMan in order to enter glycolysis and to be utilized as a source of carbon and ATP (10).

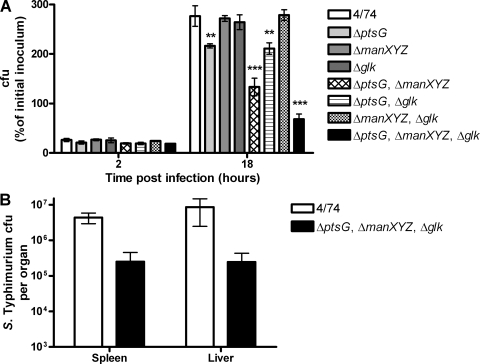

We also constructed S. Typhimurium mutants JH3504, JH3501, and JH3494, which have deletions in the ptsG, manXYZ, and glk genes, respectively. We were able to use P22 phage transduction and FLP recombinase methods to engineer mutants with every combination of double and triple mutations in these three genes and generated the following strains: ΔptsG ΔmanXYZ strain AT1011, ΔptsG Δglk strain AT1012, ΔmanXYZ Δglk strain AT1013, and ΔptsG ΔmanXYZ Δglk strain AT1014. We checked the growth of these strains on M9 minimal medium plates with glucose as the sole carbon source and observed that while the growth of the single and double mutants was slower than that of the 4/74 wild-type strain, only the triple mutant was unable to grow on this medium (data not shown). We tested these mutants to determine if the inability to utilize glucose as a carbon source led to decreased replication during infection of macrophages (Fig. 5A). The results for the single mutants showed that disruption of manXYZ or glk had no effect on S. Typhimurium replication within macrophages compared to that of the wild-type strain. However, the ptsG single mutant, JH3504, was slightly attenuated for replication compared to the wild type, as previously observed for the crr mutant (Fig. 4A). This result indicates that glucose is available to S. Typhimurium during infection of macrophages because of the specificity of the ptsG-encoded IIBCGlc PTS system for glucose (40). The low level of attenuation of the ptsG mutant probably reflects the fact that IIABCGlc is the primary route of glucose transport but its loss can be mostly compensated for by alternative glucose transporters, such as IIABCDMan. The fact that the manXYZ and glk single mutants were not attenuated for replication indicates that these genes play a smaller role than ptsG during growth of S. Typhimurium on glucose. The lack of attenuation of the manXYZ mutant shows that mannose is not an important carbon source for S. Typhimurium within macrophages, because IIABCDMan is the only efficient transport system for this sugar (40). The results for the double mutants showed that the loss of both manXYZ and glk had no effect on S. Typhimurium replication in macrophages. Therefore, IIABCDMan and glucokinase are redundant for utilization of glucose in the presence of a functional IIABCGlc PTS system.

FIG. 5.

Glucose transport is required for S. Typhimurium replication within macrophages. (A) Intracellular replication assay with the S. Typhimurium 4/74, ΔptsG (JH3504), Δglk (JH3494), ΔmanXYZ (JH3501), ΔptsG ΔmanXYZ (AT1011), ΔptsG Δglk (AT1012), ΔmanXYZ Δglk (AT1013), and ΔptsG ΔmanXYZ Δglk (AT1014) strains during infection of RAW 264.7 macrophages. The data show the numbers of viable bacteria (expressed as percentages of the initial inoculum) inside the macrophages at 2 h and 18 h after infection. Each bar indicates the statistical mean for three biological replicates, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations. Significant differences between parental strain 4/74 and the mutant strains are indicated by asterisks, as follows: no asterisk, P > 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001. (B) S. Typhimurium 4/74 and ΔptsG ΔmanXYZ Δglk mutant AT1014 recovered from spleens and livers at 72 h after i.p. infection of BALB/c mice. Each bar indicates the statistical mean for five biological replicates, and the error bars indicate the standard errors of the means.

Deletion of ptsG and manXYZ led to a replication defect greater than that of the ptsG single mutant (Fig. 5A). This revealed that IIABCDMan is required to partially compensate for the loss of ptsG and that loss of ptsG and manXYZ further attenuates the ability of S. Typhimurium to catabolize glucose and replicate within macrophages. In contrast, the ΔptsG Δglk double mutant was as attenuated as the ptsG single mutant, showing that glucokinase is not involved in the utilization of glucose in the presence of a functional IIABCDMan system. However, the ΔptsG ΔmanXYZ double mutant (AT1011) showed increased replication compared with the ΔptsG ΔmanXYZ Δglk triple mutant (AT1014) in macrophages, showing that glucokinase is necessary for the utilization of glucose in the absence of the IIBCGlc and IIABCDMan systems.

The most strongly attenuated mutant was the triple mutant (AT1014), which was unable to catabolize glucose (Fig. 5A). This mutant replicated only 3.6-fold, compared to the wild type, which replicated 10.5-fold, showing that the utilization of glucose is important for S. Typhimurium replication within macrophages but is not absolutely essential. The inability of the ΔptsHI-crr Δglk mutant (Fig. 4B) to replicate within macrophages suggests that at least one other PTS sugar besides glucose is available to S. Typhimurium within macrophages.

Although we had shown that glucose transport is important for S. Typhimurium replication within macrophages in a cell culture model, we had not determined if the attenuation reflected S. Typhimurium infection in vivo. We therefore tested the ΔptsG ΔmanXYZ Δglk triple mutant (AT1014) to determine its replication during i.p. infection of BALB/c mice. The results showed that AT1014, a glucose transport mutant, is attenuated at least 10-fold compared to the wild-type strain in the spleens and livers of infected mice (Fig. 5B). This result confirms that glucose is also an important carbon source for S. Typhimurium during systemic infection.

In summary, we determined the abilities of 15 metabolic mutants of S. Typhimurium to thrive inside macrophages. The results of these experiments revealed that glycolysis and the PTS system are required for replication within macrophages and mice. Glucose is the most important sugar for replication in the intracellular niche.

DISCUSSION

In this study we conducted a systematic mutational analysis which revealed that the central metabolic pathway of glycolysis is required for infection of macrophages (Fig. 2). We established that the key committing step for sugar catabolism, the irreversible glycolytic reaction catalyzed by phosphofructokinase, is necessary for intracellular replication of S. Typhimurium in macrophages.

Having established that glycolysis is required for intracellular replication in macrophages, we showed that S. Typhimurium uses glycolysis for successful infection of mice. The S. Typhimurium ΔpfkAB strain was significantly attenuated, and this phenotype was fully complemented by expression of pfkA in trans from a plasmid (Fig. 3), confirming that glycolysis is essential for systemic infection of mice by S. Typhimurium. Our findings are consistent with the findings of a previous study which suggested that sugars enter the glycolytic and gluconeogenic pathways at or above fructose-6-phosphate during infection of mice (53).

The glycolytic pathway converts hexose sugars into ATP and pyruvate, and we considered the PTS system a likely route of entry of hexoses into the bacterial cell. We constructed mutants in which ptsHI and/or crr was deleted to assess the importance of both the PTS system and inducer exclusion for S. Typhimurium replication within macrophages (Fig. 4A). We observed that loss of ptsHI, with or without crr, resulted in reduced intracellular replication rates, confirming that Salmonella requires sugar transport for growth within macrophages. As the ΔptsHI mutant was more attenuated than the ΔptsHI-crr mutant, we concluded that sugar transporters that benefit S. Typhimurium growth within macrophages are regulated by inducer exclusion. These inducer exclusion-dependent transporters that promote S. Typhimurium intracellular growth could include GalP, which is known to transport glucose (23, 39). In this context, we observed that a ΔptsHI-crr Δglk mutant did not replicate within macrophages as well as the ΔptsHI-crr strain (Fig. 4B), which suggested that glucose is a major nutrient required for growth of S. Typhimurium in macrophages.

It was still possible that the EI and HPr components of the PTS system transport other sugars that could be utilized, so we constructed S. Typhimurium strains with deletions of the ptsG, manXYZ, and glk genes. The ptsG gene encodes the IIB and IIC domains of the glucose-specific PTS permease. The manXYZ genes encode the mannose PTS permease, which also transports several other carbohydrates, including glucose. We carried out macrophage infection experiments with these strains and found that intracellular replication of S. Typhimurium was severely decreased when all three genes were absent compared to the replication of the wild type (Fig. 5A). This confirmed that glucose is utilized as a carbon source by S. Typhimurium during infection of macrophages. We then demonstrated that the ΔptsG ΔmanXYZ Δglk mutant was also attenuated during infection of mice (Fig. 5B). Our data show that the attenuation of metabolic mutants in macrophages that was observed was not simply an artifact of the growth conditions used to maintain the cells and did reflect the conditions encountered within the animal model. Glucose is therefore an important carbon source for S. Typhimurium during systemic infection of mice.

The reason why glucose utilization and glycolysis are so crucial for S. Typhimurium infection of mice and macrophages remains an intriguing question that will benefit from further research. It is clear from previous work that S. Typhimurium has access to several alternative carbon sources, apart from sugars, during systemic infection of mice (4, 28, 31, 53). For example, glutamine is available as a carbon source during Salmonella infection of mice and macrophages (28). It has been suggested that gluconeogenic substrates, such as amino acids or TCA cycle intermediates, also need to be available to S. Typhimurium during infection of mice (31, 53).

Our discovery that S. Typhimurium requires glycolysis and glucose for successful infection of macrophages and mice shows the key role that central metabolism plays in the infection of a host by a pathogen.

Acknowledgments

We thank Vittoria Danino and Isabelle Hautefort for critically reviewing the manuscript and other members of the Salmonella lab for helpful comments.

We are grateful to the BBSRC for funding this work (grant BB/D004810/1 to A.T. and a core strategic grant to J.C.D.H.).

Editor: S. R. Blanke

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 April 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrahams, G. L., and M. Hensel. 2006. Manipulating cellular transport and immune responses: dynamic interactions between intracellular Salmonella enterica and its host cells. Cell. Microbiol. 8728-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appleyard, A. N., R. B. Herbert, P. J. Henderson, A. Watts, and P. J. Spooner. 2000. Selective NMR observation of inhibitor and sugar binding to the galactose-H+ symport protein GalP. of Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 150955-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumler, A. J., R. M. Tsolis, P. J. Valentine, T. A. Ficht, and F. Heffron. 1997. Synergistic effect of mutations in invA and lpfC on the ability of Salmonella typhimurium to cause murine typhoid. Infect. Immun. 652254-2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker, D., M. Selbach, C. Rollenhagen, M. Ballmaier, T. F. Meyer, M. Mann, and D. Bumann. 2006. Robust Salmonella metabolism limits possibilities for new antimicrobials. Nature 440303-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boos, W. 1969. The galactose binding protein and its relationship to the beta-methylgalactoside permease from Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 1066-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinkkotter, A., H. Kloss, C. Alpert, and J. W. Lengeler. 2000. Pathways for the utilization of N-acetyl-galactosamine and galactosamine in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 37125-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, M. P., N. Shaikh, M. Brenowitz, and L. Brand. 1994. The allosteric interaction between d-galactose and the Escherichia coli galactose repressor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 26912600-12605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherepanov, P. P., and W. Wackernagel. 1995. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 1589-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crump, J. A., S. P. Luby, and E. D. Mintz. 2004. The global burden of typhoid fever. Bull. W. H. O. 82346-353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtis, S. J., and W. Epstein. 1975. Phosphorylation of d-glucose in Escherichia coli mutants defective in glucosephosphotransferase, mannosephosphotransferase, and glucokinase. J. Bacteriol. 1221189-1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 976640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Death, A., and T. Ferenci. 1993. The importance of the binding-protein-dependent Mgl system to the transport of glucose in Escherichia coli growing on low sugar concentrations. Res. Microbiol. 144529-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Boer, M., C. P. Broekhuizen, and P. W. Postma. 1986. Regulation of glycerol kinase by enzyme IIIGlc of the phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase system. J. Bacteriol. 167393-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Reuse, H., and A. Danchin. 1988. The ptsH, ptsI, and crr genes of the Escherichia coli phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system: a complex operon with several modes of transcription. J. Bacteriol. 1703827-3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deutscher, J., C. Francke, and P. W. Postma. 2006. How phosphotransferase system-related protein phosphorylation regulates carbohydrate metabolism in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70939-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eriksson, S., J. Bjorkman, S. Borg, A. Syk, S. Pettersson, D. I. Andersson, and M. Rhen. 2000. Salmonella typhimurium mutants that downregulate phagocyte nitric oxide production. Cell. Microbiol. 2239-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eriksson, S., S. Lucchini, A. Thompson, M. Rhen, and J. C. Hinton. 2003. Unravelling the biology of macrophage infection by gene expression profiling of intracellular Salmonella enterica. Mol. Microbiol. 47103-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraenkel, D. G. 1996. Glycolysis, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 19.Gallois, A., J. R. Klein, L. A. Allen, B. D. Jones, and W. M. Nauseef. 2001. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-encoded type III secretion system mediates exclusion of NADPH oxidase assembly from the phagosomal membrane. J. Immunol. 1665741-5748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grant, A. J., O. Restif, T. J. McKinley, M. Sheppard, D. J. Maskell, and P. Mastroeni. 2008. Modelling within-host spatiotemporal dynamics of invasive bacterial disease. PLoS Biol. 6e74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haraga, A., M. B. Ohlson, and S. I. Miller. 2008. Salmonellae interplay with host cells. Nat. Rev. 653-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hautefort, I., A. Thompson, S. Eriksson-Ygberg, M. L. Parker, S. Lucchini, V. Danino, R. J. Bongaerts, N. Ahmad, M. Rhen, and J. C. Hinton. 2008. During infection of epithelial cells Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium undergoes a time-dependent transcriptional adaptation that results in simultaneous expression of three type 3 secretion systems. Cell. Microbiol. 10958-984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson, P. J., R. A. Giddens, and M. C. Jones-Mortimer. 1977. Transport of galactose, glucose and their molecular analogues by Escherichia coli K12. Biochem. J. 162309-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoiseth, S. K., and B. A. Stocker. 1981. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature 291238-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosono, K., H. Kakuda, and S. Ichihara. 1995. Decreasing accumulation of acetate in a rich medium by Escherichia coli on introduction of genes on a multicopy plasmid. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 59256-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Humphreys, S., A. Stevenson, A. Bacon, A. B. Weinhardt, and M. Roberts. 1999. The alternative sigma factor, σE, is critically important for the virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 671560-1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kao, K. C., L. M. Tran, and J. C. Liao. 2005. A global regulatory role of gluconeogenic genes in Escherichia coli revealed by transcriptome network analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 28036079-36087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klose, K. E., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1997. Simultaneous prevention of glutamine synthesis and high-affinity transport attenuates Salmonella typhimurium virulence. Infect. Immun. 65587-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macpherson, A. J., M. C. Jones-Mortimer, P. Horne, and P. J. Henderson. 1983. Identification of the GalP galactose transport protein of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2584390-4396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marsh, D., and P. J. Henderson. 2001. Specific spin labelling of the sugar-H+ symporter, GalP, in cell membranes of Escherichia coli: site mobility and overall rotational diffusion of the protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1510464-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mercado-Lubo, R., E. J. Gauger, M. P. Leatham, T. Conway, and P. S. Cohen. 2008. A Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium succinate dehydrogenase/fumarate reductase double mutant is avirulent and immunogenic in BALB/c mice. Infect. Immun. 761128-1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyer, D., C. Schneider-Fresenius, R. Horlacher, R. Peist, and W. Boos. 1997. Molecular characterization of glucokinase from Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1791298-1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Misko, T. P., W. J. Mitchell, N. D. Meadow, and S. Roseman. 1987. Sugar transport by the bacterial phosphotransferase system. Reconstitution of inducer exclusion in Salmonella typhimurium membrane vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 26216261-16266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Misset, O., M. Blaauw, P. W. Postma, and G. T. Robillard. 1983. Bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system. Mechanism of the transmembrane sugar translocation and phosphorylation. Biochemistry 226163-6170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson, S. O., J. K. Wright, and P. W. Postma. 1983. The mechanism of inducer exclusion. Direct interaction between purified III of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system and the lactose carrier of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 2715-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Novotny, M. J., W. L. Frederickson, E. B. Waygood, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1985. Allosteric regulation of glycerol kinase by enzyme IIIglc of the phosphotransferase system in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 162:810-816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osumi, T., and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1982. Regulation of lactose permease activity by the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system: evidence for direct binding of the glucose-specific enzyme III to the lactose permease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79:1457-1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oswald, I. P., F. Lantier, R. Moutier, M. F. Bertrand, and E. Skamene. 1992. Intraperitoneal infection with Salmonella abortusovis is partially controlled by a gene closely linked with the Ity gene. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 87373-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Postma, P. W. 1977. Galactose transport in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 129630-639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Postma, P. W., J. W. Lengeler, and G. R. Jacobson. 1993. Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems of bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57543-594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reddy, P., and M. Kamireddi. 1998. Modulation of Escherichia coli adenylyl cyclase activity by catalytic-site mutants of protein IIAGlc of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. J. Bacteriol. 180732-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rephaeli, A. W., and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1980. Substrate specificity and kinetic characterization of sugar uptake and phosphorylation, catalyzed by the mannose enzyme II of the phosphotransferase system in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 255:8585-8591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richter-Dahlfors, A., A. M. Buchan, and B. B. Finlay. 1997. Murine salmonellosis studied by confocal microscopy: Salmonella typhimurium resides intracellularly inside macrophages and exerts a cytotoxic effect on phagocytes in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 186569-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riley, M. 1993. Functions of the gene products of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 57862-952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rotman, B., A. K. Ganesan, and R. Guzman. 1968. Transport systems for galactose and galactosides in Escherichia coli. II. Substrate and inducer specificities. J. Mol. Biol. 36247-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saier, M. H., Jr. 1989. Protein phosphorylation and allosteric control of inducer exclusion and catabolite repression by the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. Microbiol. Rev. 53109-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saier, M. H., Jr., and B. U. Feucht. 1975. Coordinate regulation of adenylate cyclase and carbohydrate permeases by the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 250:7078-7080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santos, R. L., S. Zhang, R. M. Tsolis, R. A. Kingsley, L. G. Adams, and A. J. Baumler. 2001. Animal models of Salmonella infections: enteritis versus typhoid fever. Microbes Infect. 31335-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silhavy, T. J., and W. Boos. 1973. A convenient synthesis of (2R)-glyceryl-beta-d-galactopyranoside. A substrate for beta-galactosidase, the lactose repressor, the galactose-binding protein, and the beta-methylgalactoside transport system. J. Biol. Chem. 2486571-6574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith, H. O., and M. Levine. 1967. A phage P22 gene controlling integration of prophage. Virology 31207-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sondej, M., A. B. Weinglass, A. Peterkofsky, and H. R. Kaback. 2002. Binding of enzyme IIAGlc, a component of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system, to the Escherichia coli lactose permease. Biochemistry 415556-5565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stock, J. B., E. B. Waygood, N. D. Meadow, P. W. Postma, and S. Roseman. 1982. Sugar transport by the bacterial phosphotransferase system. The glucose receptors of the Salmonella typhimurium phosphotransferase system. J. Biol. Chem. 25714543-14552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tchawa Yimga, M., M. P. Leatham, J. H. Allen, D. C. Laux, T. Conway, and P. S. Cohen. 2006. Role of gluconeogenesis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle in the virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in BALB/c mice. Infect. Immun. 741130-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thompson, A., M. D. Rolfe, S. Lucchini, P. Schwerk, J. C. Hinton, and K. Tedin. 2006. The bacterial signal molecule, ppGpp, mediates the environmental regulation of both the invasion and intracellular virulence gene programs of Salmonella. J. Biol. Chem. 28130112-30121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thompson, A., G. Rowley, M. Alston, V. Danino, and J. C. Hinton. 2006. Salmonella transcriptomics: relating regulons, stimulons and regulatory networks to the process of infection. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9109-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsolis, R. M., R. A. Kingsley, S. M. Townsend, T. A. Ficht, L. G. Adams, and A. J. Baumler. 1999. Of mice, calves, and men. Comparison of the mouse typhoid model with other Salmonella infections. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 473261-274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang, R. F., and S. R. Kushner. 1991. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene 100195-199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woodcock, D. M., P. J. Crowther, J. Doherty, S. Jefferson, E. DeCruz, M. Noyer-Weidner, S. S. Smith, M. Z. Michael, and M. W. Graham. 1989. Quantitative evaluation of Escherichia coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res. 173469-3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wray, C., and W. J. Sojka. 1978. Experimental Salmonella typhimurium infection in calves. Res. Vet. Sci. 25139-143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zheng, D., C. Constantinidou, J. L. Hobman, and S. D. Minchin. 2004. Identification of the CRP regulon using in vitro and in vivo transcriptional profiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 325874-5893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]