Abstract

The innate immune system of humans recognizes the human pathogenic fungus Candida albicans via sugar polymers present in the cell wall, such as mannan and β-glucan. Here, we examined whether nucleic acids from C. albicans activate dendritic cells. C. albicans DNA induced interleukin-12p40 (IL-12p40) production and CD40 expression by murine bone marrow-derived myeloid dendritic cells (BM-DCs) in a dose-dependent manner. BM-DCs that lacked Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), TLR2, and dectin-1, which are pattern recognition receptors for fungal cell wall components, produced IL-12p40 at levels comparable to the levels produced by BM-DCs from wild-type mice, and DNA from a C. albicans pmr1Δ null mutant, which has a gross defect in mannosylation, retained the ability to activate BM-DCs. This stimulatory effect disappeared completely after DNase treatment. In contrast, RNase treatment increased production of the cytokine. A similar reduction in cytokine production was observed when BM-DCs from TLR9−/− and MyD88−/− mice were used. In a luciferase reporter assay, NF-κB activation was detected in TLR9-expressing HEK293T cells stimulated with C. albicans DNA. Confocal microscopic analysis showed similar localization of C. albicans DNA and CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG-ODN) in BM-DCs. Treatment of C. albicans DNA with methylase did not affect its ability to induce IL-12p40 synthesis, whereas the same treatment completely eliminated the ability of CpG-ODN to induce IL-12p40 synthesis. Finally, impaired clearance of this fungal pathogen was not found in the kidneys of TLR9−/− mice. These results suggested that C. albicans DNA activated BM-DCs through a TLR9-mediated signaling pathway using a mechanism independent of the unmethylated CpG motif.

The fungus Candida albicans colonizes the mucosal tissue of the oral cavity, the gastrointestinal tract, and the vagina of healthy individuals, where it is part of the normal commensal microflora (13, 32, 40). However, under certain conditions that perturb or result in loss of local defense mechanisms, such as administration of immunosuppressants, chemotherapeutic agents, or broad-spectrum antibiotics, it can cause local and systemic candidiasis (9, 39, 52). Thus, host defense mechanisms at mucosal surfaces play a critical role in restricting fungal growth and preventing tissue invasion.

Innate immune cells, such as dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages, residing in the mucosal tissues encounter microbes and are the first line of host defense, which involves phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and cytokine secretion. These cells sense unique structures of pathogens, designated pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) (1). Interactions between these receptors and their ligands not only initiate innate immune responses but also determine the fate of subsequent acquired immune responses (33, 47). The sugar components of the C. albicans cell wall have been shown to be important PAMPs during recognition by the innate immune system (36). N-linked mannan and O-linked mannan, along with β-glucan (29), have been major targets of research, and several PRRs involved in the mechanism have been identified, such as Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), TLR2, mannose receptor, and dectin-1 (6, 11, 30, 45). TLR4 has been reported to interact with O-linked mannan of the C. albicans cell wall (30) and through both MyD88 and TRIF (Toll-interleukin-1 [IL-1] receptor domain-containing adapter inducing beta interferon) pathways activates downstream nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and p38/c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling molecules with secretion of IL-12 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (29). On the other hand, interaction between TLR2 on the DC surface and β-glucan induces the production of regulatory cytokines, such as transforming growth factor β and IL-10, and inhibition of p38/c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation during TLR4 signaling (31). In addition, recognition of β-glucan by dectin-1, a C-type lectin-like receptor, has been shown to have a synergistic effect on the TLR2 pathway, leading to TNF-α secretion by macrophages (12). Thus, cytokine production following sensing of C. albicans cell structures is determined by a recognition network downstream of several PRRs.

Recently, we reported that DNA from Cryptococcus neoformans activates bone marrow-derived DCs (BM-DCs) by triggering a TLR9/MyD88-mediated signaling pathway (28). A similar observation has been reported for Aspergillus fumigatus by Ramirez-Ortiz and coworkers (34). DNA from the clinically important fungal pathogen C. albicans has been reported to stimulate macrophage function (54). However, the precise mechanism of its effect is unclear. The present study was designed to determine whether C. albicans DNA activates BM-DCs through a TLR9/MyD88-dependent signaling mechanism. In addition, the role of TLR9 in disseminated C. albicans infection was investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

TLR2 gene-deficient (TLR2−/−), TLR4−/−, TLR9−/−, MyD88−/−, and dectin-1−/− mice were generated as described previously (15, 17, 38, 48, 53). Homozygous mice were backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice for more than eight generations. Male or female mice that were 6 to 10 weeks old were used for the experiments, and wild-type C57BL/6 mice were used as controls. All mice were kept under specific-pathogen-free conditions at University of the Ryukyus, Tohoku University, and Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo. The experiments were conducted according to institutional guidelines and were approved by the institutional ethics committees.

Microorganisms.

A clinical isolate of C. albicans, designated THK519, was obtained from a patient admitted to Tohoku University Hospital. ATCC 18804, another C. albicans strain, was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. Saccharomyces cerevisiae NBRC1136 was purchased from the National Institute of Technology and Evaluation. The yeast cells were cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates (Eiken, Tokyo, Japan) at 30°C for 2 to 3 days before use. Homozygous pmr1Δ null mutant strain NGY355, defective in both O-linked and N-linked mannosylation pathways, was constructed using C. albicans CAI4 as the genetic background by targeted gene disruption (2). The inhibition of glycosylation in this mutant is due to low levels of Mn2+ in the Golgi apparatus (2, 8). As the CIp10 plasmid is integrated into the RPS1 locus in this mutant, the parental C. albicans strain CAI4 was also transformed using empty CIp10 to obtain strains isogenic with respect to Ura status (5). The resulting strain is referred to below as the wild-type control strain. The C. albicans pmr1Δ null mutant and wild-type strains were grown overnight with continuous shaking at 200 rpm at 30°C in Sabouraud broth (1% [wt/vol] mycological peptone, 4% [wt/vol] glucose), transferred to fresh medium, and incubated for 4 h, and then cells were harvested by centrifugation. Cell pellets were washed twice in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and heat killed at 95°C for 15 min.

Cell culture medium and reagents.

RPMI 1640 medium was obtained from Nippro (Osaka, Japan), and fetal calf serum (FCS) was obtained from Cansera (Rexdale, Ontario, Canada). DNase, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and peptidoglycan (PG) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), and Sss CpG methylase was purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). RNase was purchased from Qiagen (Tokyo, Japan). NaClO-oxidized C. albicans (OX-CA), a particle form of β-1,6-branched β-1,3-glucan, was prepared as described previously (18). CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) CpG1826 (TCC ATG ACG TTC CTG ACG TT) was synthesized, phosphorothioated, and purified by high-performance liquid chromatography at Hokkaido System Science (Sapporo, Japan). Double-stranded (ds) CpG1826 was prepared by annealing with the complementary ODN.

Preparation of DNA.

For preparation of C. albicans and S. cerevisiae DNA, yeast cells were lysed with 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.3), 0.5% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 30 mM EDTA at 100°C for 15 min. The DNA was purified by extraction with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and isopropanol precipitation. The pellet was washed with 70% (vol/vol) ethanol, dried, and resolved with distilled water. The DNA obtained was kept at −20°C until it was used. The endotoxin content of the DNA preparations, as measured by the Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay, was less than 10 pg/ml. Also, the β1,3-d-glucan concentration was measured by the G test (27), and Candida mannan antigen was detected by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described (10). To eliminate RNA contamination, DNAs used in all experiments were treated with RNase before assays were performed.

Treatment of C. albicans DNA with DNase, RNase, and methylase.

For enzymatic treatment, C. albicans DNA was incubated with DNase and RNase at 37°C for 1 h. After incubation, the DNA was heated at 65°C for 15 min to inactivate the DNase and was purified by precipitation. Methylation of ds CpG1826 or C. albicans DNA was carried out by incubating each DNA with Sss CpG methylase (10 U/μg DNA) for 24 h at 37°C. Then the DNA was heated at 68°C for 20 min to inactivate the enzyme, centrifuged, and precipitated in isopropanol.

Preparation and culture of DCs.

DCs were prepared from BM-DCs as described previously (25), with some modifications. Briefly, bone marrow cells from TLR2−/−, TLR4−/−, TLR9−/−, MyD88−/−, dectin-1−/−, and control wild-type mice were cultured at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/ml in 10 ml RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 20 ng/ml murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Wako, Osaka, Japan). On day 3, the same medium (10 ml) was added, and on day 6 one-half of the medium was replaced with a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-containing culture medium. On day 8, nonadherent cells were collected and used. When cultures were incubated with various stimulants, the concentration of cells was adjusted to 1 × 105 cells/ml and cultures were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

ELISA.

The concentration of IL-12p40 in culture supernatants was measured by an ELISA using biotinylated developing antibodies (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). The detection limit of the assay is 15 pg/ml.

Flow cytometry analysis.

Cells were preincubated with anti-mouse FcγRII and FcγRIII monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) prepared using a protein G column kit (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD) from the culture supernatants of hybridoma cells (clone 2.4G2). Cells were placed on ice for 15 min in buffer (PBS containing 1% [vol/vol] FCS and 0.1% [wt/vol] sodium azide), stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD11c MAb (clone HL3; BD Bioscience) and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD40 MAb (clone 1C10; e-Bioscience, San Diego, CA) for 25 min, and then washed three times in buffer. Isotype-matched irrelevant antibodies were used as controls. The stained cells were analyzed using a Cytomics FC500 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA). Data were collected from 15,000 to 20,000 individual live cells using forward scatter and side scatter parameters and FL1 to set a gate on the CD11c+ lymphocyte population.

TLR9 cloning and NF-κB reporter assay.

Full-length TLR9 DNA was PCR amplified from cDNA of mouse macrophage cell line RAW 264.1 cells (RIKEN Cell Bank, Tsukuba, Japan). Specific primers for amplification of TLR9 DNA were designed based on the GenBank accession number AF314224 sequence (7). The sequences of the primers were 5′-CAC CAT GGT TCT CCG TCG AAG G-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTA TTC TGC TGT AGG TCC CCG GC-3′ (reverse). The amplified full-length cDNA was cloned into pcDNA6.2/TOPO (Invitrogen, Tokyo, Japan) and sequenced. Endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule 1 luciferase reporter plasmids were kindly provided by Masao Mitsuyama (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan). For the NF-κB luciferase reporter assay, HEK293T cells were transiently cotransfected with 100 ng of reporter plasmid and 100 ng of TLR9 expression plasmid or empty vector plasmid. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were stimulated with CpG-ODN or C. albicans DNA for 16 h. The luciferase activity in the total cell lysate was measured with the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Tokyo, Japan). The Renilla luciferase reporter gene was simultaneously transfected as an internal control. The relative luciferase activity was calculated as fold induction compared with the unstimulated empty vector plasmid or the TLR9 plasmid.

Fluorescent labeling and confocal imaging.

C. albicans DNA was labeled with Alexa Fluor 647 using a ULYSIS nucleic acid labeling kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. The relative efficiency of the labeling reaction was evaluated by calculating the approximate ratio of bases to dye molecules. Rhodamine-labeled CpG-ODN was synthesized by Hokkaido System Science. FITC-conjugated TLR9 MAb clone 26C593.2 was purchased from IMGENEX (San Diego, CA). Cells were incubated with DNA in microtubes, stained for TLR9 after cell permeabilization, cytospun onto glass slides, and observed microscopically using a ProLong antifade kit as a mounting medium (Molecular Probes). Confocal studies were performed with an oil immersion objective (60× Plan Apo; numerical aperture, 1.4) and a Nikon TIRF-C1 confocal microscope. Nikon EZ-C1 version 2.00 software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) was used to acquire and process the confocal images. Two-color images were acquired using a sequential acquisition mode to avoid cross-excitation.

C. albicans infection.

C. albicans ATCC 18804 was grown for 48 h at 30°C on PDA plates. Wild-type and TLR9−/− mice were intravenously infected with C. albicans (1 ×105 yeast cells per mouse in 0.1 ml PBS), and after 5 days mice were sacrificed and the fungal burdens in the kidney were determined by plating serial dilutions of homogenized organs onto PDA plates. The results were expressed as numbers of CFU per organ.

Statistical analyses.

Data are expressed below as means ± standard deviations (SD). The statistical significance of differences between groups was examined using one-way analysis of variance with a post hoc analysis (Fisher's protected least significant difference test). A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were conducted using StatView II software (Abacus Concept, Inc., Berkeley, CA).

RESULTS

Activation of BM-DCs by C. albicans DNA.

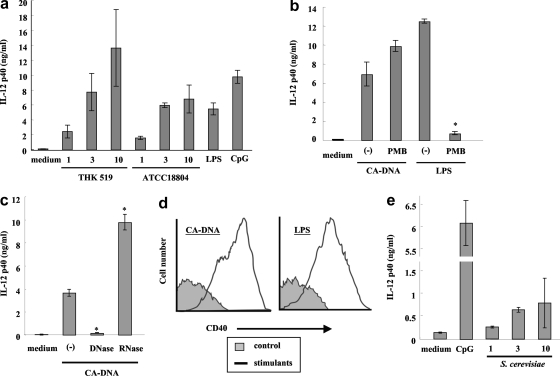

To investigate the ability of C. albicans DNA to stimulate innate immunocytes, BM-DCs were incubated with DNA from C. albicans clinical isolate THK519 for 24 h. The IL-12p40 levels in supernatants were then determined by an ELISA. As shown in Fig. 1a, DNA from THK519 induced IL-12p40 production in a dose-dependent manner, and the highest level was obtained with 10 μg/ml DNA; this level was comparable to and higher than the levels obtained after stimulation with 1 μg/ml CpG-ODN and LPS, respectively. To confirm that this activity was not specific for THK519, we also tested another C. albicans strain, ATCC 18804. DNA from ATCC 18804 also induced production of IL-12p40 (Fig. 1a). The responses were not affected by addition of polymyxin B, which completely abolished IL-12p40 production induced by LPS (Fig. 1b), indicating that the effect of C. albicans DNA was not mediated by LPS contamination. To further confirm the activation of BM-DCs by the fungal DNA, we examined the effect of DNase treatment. As shown in Fig. 1c, DNase treatment completely abrogated C. albicans DNA-induced IL-12p40 synthesis by BM-DCs. On the other hand, RNase treatment increased the stimulatory effect of C. albicans DNA. Finally, we examined whether C. albicans DNA induced the expression of CD40 on BM-DCs. As shown in Fig. 1d, incubation of BM-DCs with C. albicans DNA resulted in increased expression of this surface molecule. These results indicate that DNA of C. albicans triggers activation of DCs.

FIG. 1.

C. albicans DNA and S. cerevisiae DNA activate BM-DCs. BM-DCs were cultured under various conditions for 24 h. IL-12p40 levels in the culture supernatants were determined by ELISA (a, b, c, and e), and surface expression of CD40 on BM-DCs was determined by flow cytometry (d). The data are means ± SD of triplicate cultures. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. (−) indicates C. albicans DNA (CA-DNA) stimulation without polymyxin B (b) or DNase or RNase (c) treatment. *, P < 0.05 for a comparison of a preparation treated with polymyxin B, DNase, or RNase and a preparation that was not treated. The amount of DNA from C. albicans THK519 and S. cerevisiae DNA used was 10 μg/ml, unless indicated otherwise (a and e). The concentration of LPS used was 1 μg/ml, and the concentration of DNase used was 10 μg/ml. PMB, polymyxin B (10 μg/ml); CpG, CpG1826 (1 μg/ml).

Similarly, DNAs from other pathogenic fungi, such as C. neoformans (28), A. fumigatus (34), and Trichosporon, also induced cytokine production (data not shown). We also found that S. cerevisiae DNA stimulated BM-DCs in a dose-dependent manner, although the IL-12p40 levels produced were lower than the level elicited by C. albicans DNA (Fig. 1e). Therefore, DNA from both pathogenic and nonpathogenic fungi activates immune cells.

Role of C. albicans cell wall components in activation of BM-DCs.

The C. albicans cell wall is composed of an outer layer of glycoproteins containing N- or O-linked mannans and an inner skeletal layer consisting of β-glucans and chitin (29). Induction of cytokines by C. albicans is mediated through specific interactions between cell wall components and a receptor at the surface of immune cells. The N-linked mannan is recognized by the mannose receptor, the O-linked mannose unit is recognized by TLR4 (30), β-glucan is recognized by TLR2 and dectin-1 (12), and phospholipomannan (PLM) is recognized by TLR2 (20).

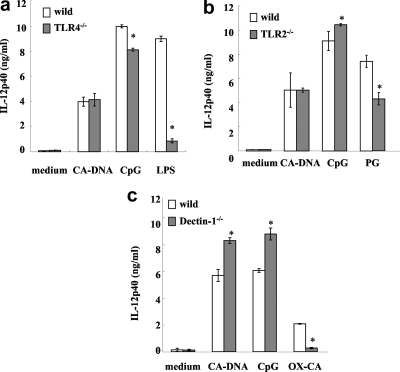

The activation of BM-DCs by C. albicans DNA mentioned above could have been due, at least in part, to the interaction between host cell receptors described above and contaminating C. albicans cell wall components. To test this possibility, we used BM-DCs derived from TLR4−/−, TLR2−/−, and dectin-1−/− mice. As shown in Fig. 2a and 2b, BM-DCs from TLR4−/− and TLR2−/− mice responded to C. albicans DNA at a level comparable to the level observed for cells from wild-type mice, whereas the LPS and PG responses were impaired in TLR4−/− and TLR2−/− mice, respectively. The IL-12p40 production in dectin-1−/− mice was greater than that in wild-type mice after stimulation with C. albicans DNA, in sharp contrast to the abrogation of the OX-CA response in dectin-1−/− mice (Fig. 2c). We also measured possible contaminating β1,3-d-glucan levels in C. albicans DNA preparations. These levels were less than 10 ng/ml. Data in Fig. 2c indicate that 3 μg/ml OX-CA elicited production of about 2 ng/ml IL-12p40, a concentration which was lower than the concentration elicited by C. albicans DNA; therefore, β-glucan contamination cannot explain the activation of BM-DCs by C. albicans DNA.

FIG. 2.

Role of C. albicans cell wall components in the activation of BM-DCs. BM-DCs from TLR4−/− and wild-type mice (a), TLR2−/− and wild-type mice (b), and dectin-1−/− and wild-type mice (c) were cultured with DNA from C. albicans THK519 (10 μg/ml), CpG1826 (1 μg/ml), LPS (1 μg/ml), OX-CA (3 μg/ml), or PG (1 μg/ml) for 24 h, and IL-12p40 levels in the culture supernatants were determined by ELISA. The data are means ± SD of triplicate cultures. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. CA-DNA, C. albicans DNA; CpG, CpG1826. *, P < 0.05 for a comparison of TLR4−/−, TLR2−/−, or dectin-1−/− mice and wild-type mice.

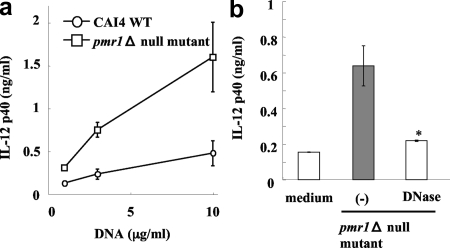

In further experiments, we examined the possible contribution of N- or O-linked mannosyl residues. For this purpose, we tested a glycosylation mutant, the C. albicans pmr1Δ null mutant, which has a gross defect in mannosylation, as shown by the absence of phosphomannan and reduced O- and N-linked glycans (2). As shown in Fig. 3a, DNA extracted that from the C. albicans pmr1Δ null mutant induced considerable IL-12p40 synthesis by BM-DCs, which was greater than the synthesis detected when BM-DCs were stimulated with DNA from wild-type cells expressing N- and O-linked mannosyl residues. DNA samples from the wild type and pmr1Δ null mutant contained mannan at concentrations of 720 and 250 ng/ml, respectively. We also determined the concentrations of mannan in DNA samples from strains THK519 and ATCC 18804, which contained less than 10 μg/ml. The contaminating mannans likely made a minor contribution to the stimulation of IL-12p40 production, because purified Candida mannan induced the production of only 1 ng/ml IL-12p40 at concentrations as high as 100 μg/ml (data not shown). In addition, treatment of C. albicans pmr1Δ null mutant DNA with DNase resulted in almost complete elimination of this response (Fig. 3b). These results indicate that C. albicans DNA does not activate BM-DCs through β-glucan, mannosyl residues, or PLM-dependent mechanisms.

FIG. 3.

Role of manosyl residues in the activation of BM-DCs. BM-DCs were cultured with C. albicans DNA extracted from wild-type strain CAI4 or the C. albicans pmr1Δ null mutant at concentrations of 1, 3, and 10 μg/ml for 24 h, and IL-12p40 levels in the culture supernatants were determined by ELISA (a). C. albicans DNA was pretreated with or without DNase (b). (−) indicates C. albicans DNA stimulation without DNase treatment. *, P < 0.05 for a comparison of a preparation treated with DNase and a preparation that was not treated. The data are means ± SD of triplicate cultures. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

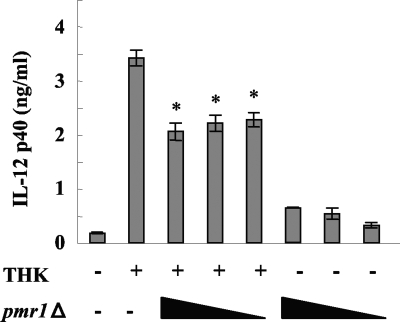

Inhibition of C. albicans DNA-mediated cytokine production by DNA from the pmr1Δ null mutant.

DNAs isolated from different C. albicans strains induced different levels of IL-12p40 production. As shown in Fig. 1a, 10 μg/ml DNA from THK519 and ATCC 18804 induced production of about 14 and 7 ng/ml IL-12p40, respectively, whereas the same concentration of DNA from CAI4 and the pmr1Δ null mutant induced production of almost 10-fold less cytokine (Fig. 3a). Because we treated DNA with RNase before all experiments, these results were not due to the inhibitory effects of contaminating RNA. Although CAI4 was generated as a homozygous URA3 null strain of clinical isolated SC5314 and the pmr1Δ null mutant was constructed by disrupting the PMR1 gene of CAI4 by the ura-blaster protocol (2, 8), such DNA modifications could hardly explain the differences in activation that were observed. Thus, we hypothesized that there may be some inhibitory mechanism in the pmr1Δ null mutant DNA. To test this hypothesis, we incubated BM-DCs with DNA from THK519 alone or with DNA from THK519 and the pmr1Δ mutant. As shown in Fig. 4, the IL-12p40 production stimulated by THK519 DNA was reduced by coincubation with pmr1Δ null mutant DNA. This suggests that the lower activity of the pmr1Δ null mutant DNA than of the THK519 DNA could be partially attributed to unknown inhibitory effects of the pmr1Δ null mutant DNA.

FIG. 4.

Inhibitory effect of C. albicans pmr1Δ DNA on THK DNA activity. BM-DCs were incubated with 3 μg/ml DNA from THK519 alone or with various concentrations of pmr1Δ null mutant DNA (50, 25, and 12.5 μg/ml) or with pmr1Δ DNA alone (50, 25, and 12.5 μg/ml) for 24 h. IL-12p40 levels in the culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. The data are means ± SD of triplicate cultures. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 for a comparison of a preparation incubated with THK519 alone and a preparation incubated with pmr1Δ null mutant DNA.

Activation of BM-DCs by C. albicans DNA is mediated by TLR9 signaling pathway.

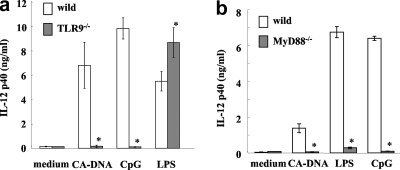

Several studies have reported that DNAs of viruses, bacteria, and even mammals are sensed by TLR-dependent and -independent signaling pathways (4, 16, 19, 41). TLR9 is a well-known PRR triggered by an unmethylated CpG motif from bacterial DNA and synthesized CpG-ODN (15). MyD88 is an adaptor molecule for TLR9 (15). In order to demonstrate that TLR9 is involved in the recognition of C. albicans DNA, we compared the stimulation of IL-12p40 production by C. albicans DNA in BM-DCs from wild-type mice and the stimulation of IL-12p40 production by C. albicans DNA in BM-DCs from TLR9−/− mice. As shown in Fig. 5a, BM-DCs from TLR9−/− mice produced little IL-12p40 upon stimulation with C. albicans DNA or CpG-ODN. Similarly, production of this cytokine was completely abrogated in BM-DCs from MyD88−/− mice (Fig. 5b).

FIG. 5.

Indispensable role of TLR9-MyD88 signaling pathway in BM-DC activation. BM-DCs from TLR9−/− and wild-type mice (a) and MyD88−/− and wild-type mice (b) were cultured with C. albicans ATCC 18804 DNA (10 μg/ml), CpG (1 μg/ml), or LPS (1 μg/ml) for 24 h, and IL-12p40 levels in the culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. The data are means ± SD of triplicate cultures. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. CA-DNA, C. albicans DNA; CpG, CpG1826. *, P < 0.05 for a comparison of TLR9−/− or MyD88−/− mice and wild-type mice.

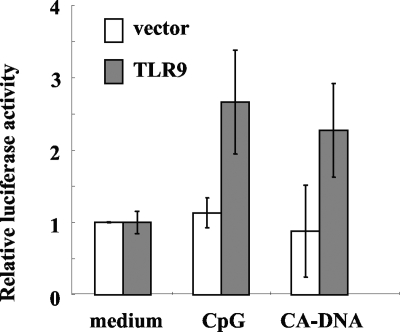

Downstream of TLR9 signaling, the transcription factor NF-κB promotes transcription of inflammatory cytokine genes, such as TNF-α and IL-12 genes (15, 22). To investigate whether C. albicans DNA activates NF-κB through a TLR9 signaling pathway, we performed a luciferase assay by transfecting HEK293T cells with the luciferase gene linked to a promoter sequence containing an NF-κB responsible element, along with positive (TLR9-expressing) and empty vector controls. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were incubated with CpG-ODN or C. albicans DNA, and the luciferase activity in the cell lysates was measured. As shown in Fig. 6, similar to CpG-ODN, C. albicans DNA activated NF-κB in the cells transfected with the TLR9-expressing vector but not in the cells transfected with the control empty vector. These results suggest that C. albicans DNA triggers NF-κB activation through direct interaction with TLR9.

FIG. 6.

NF-κB activation via TLR9 by C. albicans DNA. HEK293T cells transfected with a TLR9 gene or control vector were cultured with CpG1826 (300 nM) or DNA from C. albicans THK519 (100 μg/ml) for 6 h. The luciferase activity in each sample was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as relative values based on the value for an unstimulated sample in each group and are means ± SD of triplicate cultures. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. CA-DNA, C. albicans DNA; CpG, CpG1826.

Intracellular trafficking of C. albicans DNA.

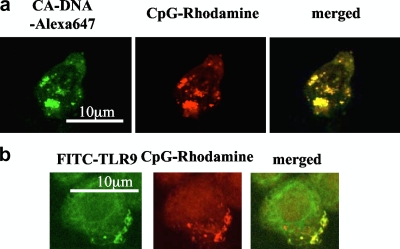

It has been reported that TLR9 is located in the endoplasmic reticulum (23). Upon stimulation with CpG motif-containing DNA, which is internalized via a clathrin-dependent pathway and rapidly moves into a lysosomal compartment, TLR9 is rapidly redistributed toward the site of CpG-DNA accumulation (23). Thus, we examined whether C. albicans DNA was internalized into BM-DCs to interact with TLR9 in the endosomal compartment. When BM-DCs were incubated with fluorescently labeled DNA extracted from C. albicans, the DNA was internalized into cells within 5 min (data not shown). After 30 min of incubation, C. albicans DNA and CpG-ODN colocalized (Fig. 7a). In addition, CpG-ODN colocalized with TLR9 in the same time interval (Fig. 7b). These results suggest that C. albicans DNA is translocated into BM-DCs in a manner similar to the manner of translocation of CpG-ODN upon engagement with TLR9.

FIG. 7.

Trafficking of C. albicans DNA in BM-DCs. BM-DCs were simultaneously incubated with 10 μg/ml Alexa 647-conjugated DNA from C. albicans THK519 (green) and 3 μM CpG-rhodamine (red) (a). BM-DCs were incubated with 3 μM CpG-rhodamine (red) for 30 min. After fixation, TLR9 was stained intracellularly by direct immunofluorescence with FITC-conjugated anti-TLR9 antibody (green) (b). Cells were analyzed using a confocal microscope. The data are representative of three or four independent experiments. CA-DNA, C. albicans DNA; CpG, CpG1826.

Effect of methylation of C. albicans DNA on BM-DC activation.

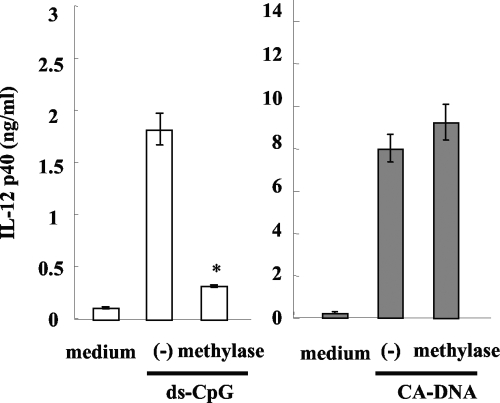

TLR9 was initially identified as a receptor for the unmethylated CpG motif, which is abundant in bacterial genomic DNA. It was found that this PRR plays an important role in the induction of proinflammatory cytokines by immunocytes stimulated with CpG-ODN (15). In contrast, mammalian DNAs, such as human and mouse DNAs, in which most of the CpG sequences are methylated, cannot stimulate these cells (data not shown). Certain fungi are known to have unmethylated CpG motifs in their genomes, and this is true for C. albicans (37). Thus, to investigate the involvement of unmethylated CpG motifs in the activity of C. albicans DNA, we stimulated BM-DCs with C. albicans DNA pretreated with DNA methylase and measured the IL-12p40 levels in the culture supernatants. As shown in Fig. 8, methylated ds CpG-ODN lost the ability to induce the synthesis of this cytokine by BM-DCs, whereas this effect was not found when C. albicans DNA was treated with the methylase. These results suggest that unmethylated CpG motifs do not mediate the activity of C. albicans DNA.

FIG. 8.

Effect of methylation of C. albicans DNA. BM-DCs were cultured with ds CpG1826 (4.5 μM) or DNA from C. albicans THK519 (10 μg/ml) pretreated or not pretreated with methylase. IL-12p40 levels in the cultures supernatants were measured by ELISA. The data are means ± SD of triplicate cultures. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. (−) indicates C. albicans DNA stimulation without methylase treatment. CA-DNA, C. albicans DNA; ds-CpG, ds CpG1826. *, P < 0.05 for a comparison of a preparation treated with methylase and a preparation that was not treated with methylase.

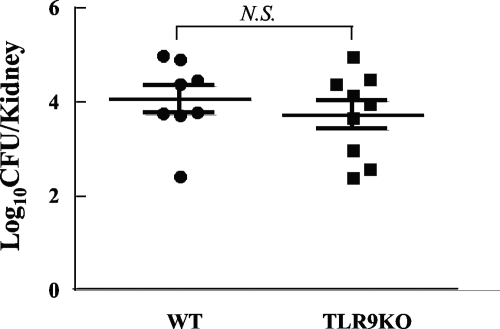

C. albicans infection in TLR9−/− mice.

To assess the role of TLR9 in the host defense against C. albicans infection, yeast cells were inoculated intravenously, and the fungal growth in kidneys of wild-type mice was compared to the fungal growth in kidneys of TLR9−/− mice. No significant difference in the fungal burdens in the kidneys between these two groups was detected (Fig. 9), although the reduction in the body weight was greater for the TLR9−/− mice than for the control mice. The mice in both groups did not die during the observation period (data not shown).

FIG. 9.

Fungal growth in TLR9−/− and wild-type mice with systemic C. albicans infections. Wild-type or TLR9−/− mice were inoculated intravenously with 105 C. albicans yeast cells in 0.1 ml. Fungal growth in the kidneys was assessed 5 days after infection. Fungal growth in the kidneys (means ± standard errors) is expressed as the number of CFU per organ. WT, wild-type mice; TLR9KO, TLR9−/− mice; N.S., difference not significant.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we hypothesized that DNA extracted from C. albicans activates innate immune cells. C. albicans DNA induced the production of IL-12p40 and expression of CD40 by BM-DCs, and this activity was completely abrogated by DNase treatment. Although it is possible that compounds contaminating DNA samples could activate BM-DCs, the DNA extraction and purification process minimizes protein contamination and RNase-treated controls showed that RNA was not responsible for the activation. Moreover, BM-DCs from TLR4−/−, TLR2−/−, and dectin-1−/− mice produced IL-12p40 at levels comparable to the level produced by wild-type mice upon stimulation with C. albicans DNA, suggesting that the cell wall polysaccharides and PLM contaminating the DNA preparations were not responsible for this effect. To further confirm this conclusion, we tested whether DNA from the mannan-deficient C. albicans pmr1Δ null mutant activated BM-DCs and observed greater induction of IL-12p40 secretion from this mutant than that from the C. albicans parent strain. Thus, mannan contamination in C. albicans DNA preparations did not contribute to the activation of BM-DCs.

Several PRRs are known to recognize nucleic acid components, such as RNA and DNA. TLR7/8 is a receptor for single-stranded RNA, and TLR9 is a well-known sensor for unmethylated CpG-ODN and bacterial and viral DNAs. These receptors are endosomal membrane-associated receptors and recognize nucleic acids. Recent studies have described a DNA-dependent activator of interferon regulatory factors (DAI), which is a novel receptor that senses the viral DNA in a cytoplasmic compartment (42, 46). As determined by a confocal microscopic analysis, fluorescently labeled C. albicans DNA was internalized in BM-DCs and localized within intracellular compartments along with CpG-ODN. Together with the finding that CpG-ODN colocalized with TRL9, these results suggested that BM-DC activation by C. albicans DNA is also mediated by a TLR9-dependent signaling pathway. In support of this conclusion, BM-DCs derived from TLR9−/− and MyD88−/− mice were not able to produce IL-12p40 in response to C. albicans DNA, and luciferase reporter assays clearly indicated that TLR9-mediated signaling is involved in the activation of NF-κB. This evidence suggests that C. albicans DNA activates BM-DCs by triggering the TLR9/MyD88-mediated signaling pathway localized in the endosomal and lysosomal compartments. RNase treatment increased the C. albicans DNA stimulatory activity (Fig. 1c), suggesting that RNA could interfere with TLR9 signaling. One possible explanation is that RNA binding competes with DNA binding to TLR9. Alternatively, RNA may bind to TLR7/8, and this signaling pathway could inhibit the signaling of TLR9 triggered by DNA. Further studies are required to understand the exact effect of RNA on C. albicans DNA.

TLR9 was initially reported to recognize the unmethylated CpG motif of bacterial DNA (15). It is known that eukaryotic cells, such as cells of certain fungi, contain unmethylated CpG in their genomes, which is a potential ligand of TLR9. In fact, DNAs from Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Schizosaccharomyces pombe have been reported to have immunostimulatory activities (41, 44), although the precise mechanism remains to be investigated. More recently, Ramirez-Ortiz et al. (34) reported that murine BM-DCs and human plasmacytoid DCs were activated by DNA from A. fumigatus. They also demonstrated that the unmethylated CpG motif of A. fumigatus genomic DNA was responsible for this immunostimulatory effect. In contrast, several reports have shown that DNAs without the CpG motif still function as immunostimulatory molecules via the TLR9-mediated signaling pathway, suggesting that TLR9 recognizes not only the CpG motif but also DNA itself with certain structures (21, 22, 35, 51). In this regard, we reported recently that genomic DNA extracted from C. neoformans activated BM-DCs via a TLR9/MyD88-mediated signaling mechanism (28). However, treatment of C. neoformans DNA with methylase resulted in a partial reduction in IL-12p40 production, suggesting that a structure other than unmethylated CpG motifs could be involved in the interaction with TLR9. In the present study, we also tested the effect of methylase treatment on C. albicans DNA and did not observe any reduction in cytokine synthesis by BM-DCs. These results raised the possibility that unmethylated CpG sequences are not essential to promote the TLR9-dependent activation of BM-DCs by C. albicans DNA. More recently, Haas et al. demonstrated that the natural base-free phosphodiester 2′ deoxyribose, the sugar backbone of DNA, binds to and activates TLR9 (14). Moreover, they found that phosphorothioate (PS)-modified 2′ deoxyribose homopolymers act as antagonists for TLR9 with high-affinity binding to this receptor. However, addition of nonrandom DNA bases, including CpG motifs, transformed the PS 2′ deoxyribose backbone into a strong agonist of TLR9, meaning that there was restricted CpG dependence of TLR9 activation. On the other hand, the phosphodiester 2′ deoxyribose backbone does not require the CpG motif for enhancement of its activity but does require a complex with a cationic lipid or 3′ extension with polyguanosine tails, which protects DNAs against DNase degradation and drives enhanced endosomal translocation (14). Taking into account the fact that even mammalian DNA can activate DCs through TLR9 with support of a carrier protein such as an anti-DNA antibody (24, 26), efficient uptake and retention in the lysosomal compartment are crucial for activity of natural DNAs. Compatible with this notion, C. albicans DNA was internalized and retained in BM-DCs similar to PS-modified CpG (Fig. 7a). Therefore, the CpG motif may not be essential for C. albicans DNA activity.

One unexpected phenomenon observed in this study was the very low levels of induction of IL-12p40 production by DNAs from CAI4 and the pmr1Δ null mutant compared to levels of induction by DNAs from other C. albicans strains. We hypothesized that some inhibitory effect could interfere with the DNA stimulation. Indeed, when we incubated BM-DCs with THK519 DNA together with the pmr1Δ null mutant DNA, the amount of IL-12p40 produced was less than that observed with the cells stimulated with THK519 DNA alone. This could have been due to inhibition of DNA uptake by some molecules. However, we observed that fluorescently labeled CAI4 and pmr1Δ null mutant DNAs trafficked into cells via similar mechanisms for both wild-type and mutant strains of C. albicans (data not shown). Therefore, inhibition of DNA uptake does not provide an explanation for the differences between the DNAs and the inhibition of the TLR9 signaling pathway. Another explanation could be the difference in the sequences of the DNAs except at the PMR1 locus. Previous studies identified DNA sequences that can bind TLR9 sufficiently and neutralize the CpG-ODN-induced activation of B cells (43). The inhibitory ODN also can inhibit the activity of C. neoformans DNA, as we reported previously (28). Thus, DNAs from CAI4 and the pmr1Δ null mutant could contain such a sequence in addition to a stimulatory sequence. Further investigations are necessary to examine this possibility.

Our study demonstrated that C. albicans DNA, like the DNAs of C. neoformans and A. fumigatus, had immunostimulatory effects on murine BM-DCs. We speculated that under physiological conditions TLR9 could recognize C. albicans DNA, which may be released from the dying fungus outside the immune cells or after live fungus cells are phagocytosed by the cells and released in phagolysome compartments of macrophages and neutrophils, resulting in stimulation of the pathway that could be involved in the host defense response against C. albicans. However, the fungal organ burdens in TLR9−/− mice after systemic infection with C. albicans were comparable to those of wild-type mice. Previously, van de Veerdonk et al. reported results similar to those reported here. In their study, despite the observation that stimulation of peritoneal macrophages from TLR9−/− mice resulted in a 20 to 30% reduction in the cytokine production induced by live C. albicans yeast, no significant differences in survival and fungal organ burden between TLR9−/− and wild-type mice were found (50). Moreover, Bellocchio et al. reported that the susceptibility of TLR9−/− mice to C. albicans yeast infection is comparable to that of wild-type mice, while the fungal burden in the kidneys was less than that of control mice (3). Based on these findings, TLR9 involvement during systemic infection by the yeast C. albicans seemed not to be crucial for the host defense mechanism. With the recent progress in understanding the mechanism of C. albicans recognition, it is suggested that multiple PAMP-PRR interactions, recognizing different components of the fungal cells, are integrated and enable the immune system to respond to this pathogen in a more sensitive and specific way (29). In addition, signals from PRRs function synergistically and antagonistically (49) under physiological conditions. Therefore, a deficiency of individual receptors may not necessarily markedly impact the host mechanism for defense against pathogens. Nevertheless, our findings revealed that C. albicans DNA could contribute to the regulation of the host immune response and provided insight into the overall mechanism of pathogen recognition by PRRs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Masao Mitsuyama for kind gifts of luciferase reporter plasmids.

This work was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid for Science Research (C) KAKENHI18590413 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Neil A. R. Gow acknowledges support from the Wellcome Trust (grant 080088).

Editor: A. Casadevall

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akira, S., S. Uematsu, and O. Takeuchi. 2006. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124783-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates, S., M. D. MacCallum, G. Bertram, C. A. Munro, H. B. Hughes, E. T. Buurman, A. J. P. Brown, F. C. Odds, and N. A. R. Gow. 2005. Candida albicans Pmr1p, a secretory pathway P-type Ca2+-ATPase, is required for glycosylation and virulence. J. Biol. Chem. 28023408-23415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellocchio, S., C. Montagnoli, S. Bozza, R. Gaziano, G. Rossi, S. S. Mambula, A. Vecchi, A. Mantovani, S. M. Levitz, and L. Romani. 2004. The contribution of the Toll-like/IL-1 receptor superfamily to innate and adaptive immunity to fungal pathogens in vivo. J. Immunol. 1723059-3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boule, M. W., C. Broughton, F. Mackay, S. Akira, A. Marshak-Rothstein, and I. R. Rifkin. 2004. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent and -independent dendritic cell activation by chromatin-immunoglobulin G complexes. J. Exp. Med. 1991631-1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brand, A., D. M. MacCallum, A. P. J. Brown, N. A. R. Gow, and F. C. Odds. 2004. Ectopic expression of URA3 can influence the virulence phenotypes and proteome of Candida albicans but can be overcome by targeted re-integration of URA3 at the RPS10 locus. Eukaryot. Cell 3900-909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, G. D., and S. Gordon. 2003. Fungal beta-glucans and mammalian immunity. Immunity 19311-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chuang, T. H., J. Lee, L. Kline, J. C. Mathison, and R. J. Ulevitch. 2002. Toll-like receptor 9 mediates CpG-DNA signaling. J. Leukoc. Biol. 71538-544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonzi, W. A., and M. Y. Irwin. 1993. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 134717-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser, V. J., M. Jones, J. Dunkel, S. Storfer, G. Medoff, and W. C. Dunagan. 1992. Candidemia in a tertiary care hospital: epidemiology, risk factors, and predictors of mortality. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15414-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujita, S., and T. Hashimoto. 1992. Detection of serum Candida antigens by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and latex agglutination test with anti-Candida albicans and anti-Candida krusei antibodies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 303132-3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gantner, B. N., R. M. Simmons, and D. M. Underhill. 2005. Dectin-1 mediates macrophage recognition of Candida albicans yeast but not filaments. EMBO J. 241277-1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gantner, B. N., R. M. Simmons, S. J. Canavera, S. Akira, and D. M. Underhill. 2003. Collaborative induction of inflammatory responses by dectin-1 and Toll-like receptor 2. J. Exp. Med. 1971107-1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorbach, S. L., L. Nahas, P. I. Lerner, and L. Weinstein. 1967. Studies of intestinal microflora. I. Effects of diet, age, and periodic sampling on numbers of fecal microorganisms in man. Gastroenterology 53845-855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haas, T., J. Metzger, F. Schmitz, A. Heit, T. Müller, E. Latz, and T. Wagner. 2008. The DNA sugar backbone 2′ deoxyribose determines Toll-like receptor 9 activation. Immunity 28315-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemmi, H., O. Takemuchi, T. Kawai, T. Kaisho, S. Sato, H. Sanjo, M. Matsumoto, K. Hoshino, H. Wagner, K. Takeda, and S. Akira. 2000. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature 408740-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hochrein, H., B. Schlatter, M. O'Keeffe, C. Wagner, F. Schmitz, M. Schiemann, S. Bauer, M. Suter, and H. Wagner. 2004. Herpes simplex virus type-1 induces IFN-α production via Toll-like receptor 9-dependent and -independent pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10111416-11421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoshino, K., T. Kaisho, T. Iwage, O. Takeuchi, and S. Akira. 1999. Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J. Immunol. 1623794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishibashi, K., N. Miura, Y. Adachi, N. Ogura, H. Tamura, S. Tanaka, and N. Ohno. 2004. DNA array analysis of altered gene expression in human leukocytes stimulated with soluble and particulate forms of Candida cell wall beta-glucan. Int. Immunopharmacol. 4387-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishii, K. J., C. Coban, H. Kato, K. Takahashi, Y. Torii, F. Takeshita, H. Ludwig, G. Sutter, K. Suzuki, H. Hemmi, S. Sato, M. Yamamoto, S. Uematsu, T. Kawai, O. Takeuchi, and S. Akira. 2006. A Toll-like receptor-independent antiviral response induced by double-stranded B-form DNA. Nat. Immunol. 740-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jouault, T., S. Ibata-Ombetta, O. Taguchi, P. Trinel, P. Sacchetti, P. Lefebvre, S. Akira, and D. Poulain. 2003. Candida albicans phospholipomannan is sensed through Toll-like receptors. J. Infect. Dis. 188165-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kandimalla, E. R., L. Bhagat, Y. Li, D. Yu, D. Wang, Y. P. Cong, S. S. Song, J. X. Tang, T. Sullivan, and S. Agrawal. 2005. Immunomodulatory oligonucleotides containing a cytosine-phophate-2′-deoxy-7-deazaguanosine motif as potent Toll-like receptor 9 agonists. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1026925-6930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumagai, Y., O. Takeuchi, and S. Akira. 2008. TLR9 as a key receptor for the recognition of DNA. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 60795-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latz, E., A. Schoenemeyer, A. Visintin, K. A. Fitzgerald, B. G. Monks, C. F. Knetter, E. Lien, N. J. Nilsen, T. Espevik, and D. T. Golenbock. 2004. TLR9 signals after translocating from the ER to CpG DNA in the lysosome. Nat. Immunol. 5190-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leadbetter, E. A., I. R. Rifkin, A. M. Hohlbaum, B. C. Beaudette, M. J. Shlomchik, and A. Marshak-Rothstein. 2002. Chromatin-IgG complexes activate B cells by dual engagement of IgM and Toll-like receptors. Nature 416603-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lutz, M. B., N. Kukutsh, A. L. Ogilvie, S. Rossner, F. Koch, N. Romani, and G. Schuler. 1999. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol. Methods. 22377-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Means, T. K., E. Latz, F. Hayashi, M. R. Murali, D. T. Golenbock, and A. D. Luster. 2005. Human lupus autoantibody-DNA complexes activate DCs through cooperation of CD32 and TLR9. J. Clin. Investig. 115407-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyazaki, T., S. Kohno, K. Mitsutake, S. Maesaki, K. Tanaka, N. Ishikawa, and K. Hara. 1995. Plasma (1→3)-β-d-Glucan and fungal antigenemia in patients with candidemia, aspergillosis, and cryptococcosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 333115-3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakamura, K., A. Miyazato, G. Xiao, M. Hatta, K. Inden, T. Aoyagi, K. Shiratori, K. Takeda, S. Akira, S. Saijo, Y. Iwakura, Y. Adachi, N. Ohno, K. Suzuki, J. Fujita, M. Kaku, and K. Kawakami. 2008. Deoxynucleic acids from Cryptococcus neoformans activate myeloid dendritic cells via a TLR9-dependent pathway. J. Immunol. 1804067-4074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Netea, M. G., G. D. Brown, B. J. Kullberg, and N. A. R. Gow. 2008. An integrated model of the recognition of Candida albicans by the innate immune system. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 667-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Netea, M. G., N. A. R. Gow, C. A. Munro, S. Bates, C. Collins, G. Ferwerda, R. P. Hobson, G. Bertram, H. B. Hughes, T. Jansen, L. Jacobs, E. T. Buurman, K. Gijzen, D. L. Williams, R. Torensma, A. McKinnon, D. M. MacCallum, F. C. Odds, J. W. M. Van der Meer, A. J. P. Brown, and B. J. Kullberg. 2006. Immune sensing of Candida albicans requires cooperative recognition of mannans and glucans by lectin and Toll-like receptors. J. Clin. Investig. 1161642-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Netea, M. G., R. Sutmuller, C. Hermann, C. A. A. Van der Graaf, J. W. M. Van der Meer, J. H. van Krieken, T. Hartung, G. Adema, and B. J. Kullberg. 2004. Toll-like receptor 2 suppresses immunity against Candida albicans through induction of IL-10 and regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 1723712-3718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Odds, F. C. 1987. Candida infections: an overview. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pasare, C., and R. Medzhitov. 2004. Toll-like receptors and acquired immunity. Semin. Immunol. 1623-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramirez-Ortiz, Z. G., C. A. Specht, J. P. Wang, C. K. Lee, D. C. Bartholomeu, R. T. Gazzinelli, and S. M. Levitz. 2008. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent immune activation by unmethylated CpG motifs in Aspergillus fumigatus DNA. Infect. Immun. 762123-2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts, T. L., M. J. Sweet, D. A. Hume, and K. J. Stacey. 2005. Cutting edge: species-specific TLR9-mediated recognition of CpG and non-CpG phosphorothioate-modified oligonucleotides. J. Immunol. 174605-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romani, L. 2004. Immunity to fungal infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 41-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russell, P. J., J. A. Welsch, E. M. Rachlin, and J. A. McCloskey. 1987. 1987. Different levels of DNA methylation in yeast and mycelial forms of Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 1694393-4395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saijo, S., N. Fujikado, T. Furuta, S. H. Chung, H. Kotani, K. Seki, K. Sudo, S. Akira, Y. Adachi, N. Ohno, T. Kinjo, K. Nakamura, K. Kawakami, and Y. Iwakura. 2007. Dectin-1 is required for host defense against Pneumocystis carinii but not against Candida albicans. Nat. Immunol. 839-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sobel, J. D. 1988. Candida infections in the intensive care unit. Crit. Care Clin. 4325-344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soll, D. R., R. Galask, J. Schmid, C. Hanna, K. Mac, and B. Morrow. 1991. Genetic dissimilarity of commensal strains of Candida spp. carried in different anatomical locations of the same healthy women. J. Clin. Microbiol. 291702-1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Souza, M. C., M. Correa, S. R. Almeida, J. D. Lopes, and Z. P. Camarg. 2001. Immunostimulatory DNA from Paracoccidioides brasiliensis acts as T-helper 1 promoter in susceptible mice. Scand. J. Immunol. 54348-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stetson, D. B., and R. Medzhitov. 2006. Recognition of cytosolic DNA activates an IRF3-dependent innate immune response. Immunity 2493-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stunz, L. L., P. Lenert, D. Peckham, A. K. Yi, S. Haxhinasto, M. Chang, A. M. Crieg, and R. F. Ashman. 2002. Inhibitory oligonucleotides specifically block effects of stimulatory CpG oligonucleotides in B cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 321212-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun, S., C. Beard, R. Jaenisch, P. Jones, and J. Sprent. 1997. Mitogenicity of DNA from different organisms for murine B cells. J. Immunol. 1593119-3125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tada, H., E. Nemoto, H. Shimuchi, T. Watanabe, T. Mikami, T. Matsumoto, N. Ohno, H. Tamura, K. Shibata, S. Akashi, S. Sugawara, and H. Takada. 2002. Saccharomyces cerevisiae- and Candida albicans-derived mannan induced production of tumor necrosis factor alpha by human monocytes in a CD14- and Toll-like receptor 4-dependent manner. Microbiol. Immunol. 46503-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takaoka, A., Z. Wang, M. K. Choi, H. Yanai, H. Negishi, T. Ban, Y. Lu, M. Miyagishi, T. Kodama, K. Honda, Y. Ohba, and T. Taniguchi. 2007. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature 448501-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takeda, K., T. Kaisho, and S. Akira. 2003. Toll-like receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21335-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takeuchi, O., K. Hoshino, T. Kawai, H. Sanjo, H. Takada, T. Ogawa, K. Takeda, and S. Akira. 1999. Differential roles of TLR2 and TLR4 in recognition of gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial cell wall components. Immunity 11443-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trinchieri, G., and A. Sher. 2007. Cooperation of Toll-like receptor signals in innate immune defence. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7179-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van de Veerdonk, F. L., M. G. Netea, T. J. Jansen, L. Jacobs, I. Verschueren, J. W. M. van der Meer, and B. J. Kullber. 2008. Redundant role of TLR9 for anti-Candida host defense. Immunobiology 213613-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vollmer, J., R. D. Weeratna, M. Jurk, U. Samulowitz, M. J. McCluskie, P. Payette, H. L. Davis, C. Schetter, and A. M. Krieg. 2004. Oligodeoxynucleotides lacking CpG dinucleotides mediate Toll-like receptor 9 dependent T helper type 2-biased immune stimulation. Immunology 113212-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wey, S. B., M. Mori, M. A. Pfaller, R. F. Woolson, and R. P. Wenzel. 1989. Risk factors for hospital-acquired candidaemia. A matched case—control study. Arch. Intern. Med. 1492349-2353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamamoto, M., S. Sato, H. Henmi, K. Hoshino, T. Kaisho, H. Sanjo, O. Takeuchi, M. Sugiyama, M. Okabe, K. Takeda, and S. Akira. 2003. Role of adaptor TRIF in the Myd88-independent Toll-like receptor. Science 301640-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yordanov, M., P. Dimitrova, S. Danova, and N. Ivanovska. 2005. Candida albicans double-stranded DNA can participate in the host defense against disseminated candidiasis. Microbes Infect. 7178-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]