Abstract

We have shown previously that the Ca2+-dependent inhibition of lens epithelial cell-to-cell communication is mediated in part by the direct association of calmodulin (CaM) with connexin43 (Cx43), the major connexin in these cells. We now show that elevation of [Ca2+]i in HeLa cells transfected with the lens fiber cell gap junction protein sheep Cx44 also results in the inhibition of cell-to-cell dye transfer. A peptide comprising the putative CaM binding domain (aa 129–150) of the intracellular loop region of this connexin exhibited a high affinity, stoichiometric interaction with Ca2+-CaM. NMR studies indicate that the binding of Cx44 peptide to CaM reflects a classical embracing mode of interaction. The interaction is an exothermic event that is both enthalpically and entropically driven in which electrostatic interactions play an important role. The binding of the Cx44 peptide to CaM increases the CaM intradomain cooperativity and enhances the Ca2+-binding affinities of the C-domain of CaM more than twofold by slowing the rate of Ca2+ release from the complex. Our data suggest a common mechanism by which the Ca2+-dependent inhibition of the α-class of gap junction proteins is mediated by the direct association of an intracellular loop region of these proteins with Ca2+-CaM.

Introduction

Gap junctions, formed by the docking of two hemichannels (termed connexons) in two apposing cells, mediate cell-to-cell communication of small molecules (<1 kDa) between neighboring mammalian cells (1). Each connexon is composed of six connexin (Cx) subunits of which there are at least 20 isoforms in the human genome (2). All the Cx proteins share a similar topology composed of four highly conserved transmembrane regions, a short N-terminal cytoplasmic region, one intracellular and two extracellular loops, with a C-terminal intracellular tail that has the least sequence homology among different Cx types. According to their sequence similarity, Cx can be further grouped into at least three classes, α, β, and γ (3). A variety of naturally occurring mutations in the α-class of Cx proteins, including the ubiquitous Cx43, and the lens connexins Cx46 (the rodent ortholog of sheep Cx44) and Cx50, are associated with specific defects in the lens (4). In addition, knockout of Cx46 or Cx50 in mice has been shown to result in lens cataract formation or smaller lenses respectively (5–8). Primary cell cultures of sheep lens epithelial cells have been used previously in this laboratory to show the Ca2+-dependent inhibition of lens connexins (9,10). Yang and Louis (11) showed that Cx44 is also expressed in these lens cell cultures; as such, Cx44 gap junctions would thus seem to be regulated by intracellular Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i.

It has long been known that gap junctions are inhibited by elevated intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) (12). Other studies have shown that calmodulin (CaM) seems to effect the Ca2+-dependent inhibition of the β-class gap junction protein Cx32 via its direct association with the N-terminus and C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of Cx32 (13–16). The role of the proposed Ca2+-CaM association with gap junctions in the lens has been much discussed, although the role of elevated intracellular Ca2+ is associated with cellular death (17), and it is possible that gap junction closure mediated by Ca2+-CaM may prevent the bystander effect. In the α-class of gap junction proteins, a single potential 1-5-10 subclass CaM binding site with high predicative score can be identified in the intracellular loop using the CaM binding database server (18). Our previous studies (19) showed that this Ca2+-mediated inhibition of the α-connexin Cx43 is effected by the direct association of Ca2+-CaM with this connexin. The single predicted CaM binding site in Cx43 was shown to bind CaM stoichiometrically with a dissociation constant of ∼0.7–1 μM (20). The predicted CaM binding sequence in Cx44 is preserved in both rodent and human Cx46, and alignment results of the amino acid sequences show a single conservative amino acid substitution in the rodent ortholog and three conservative amino acid substitutions in the human ortholog. Thus, studies with the sheep Cx44 peptide can be reasonably expected to mimic those using a peptide for this same domain of rodent or human Cx46. In this study, we have used biophysical approaches to characterize a high affinity, Ca2+-dependent, stoichiometric association between CaM and a peptide corresponding to residues 129–150 of Cx44, and by extension, the analogous sequences in Cx46 (residues 138–159 in rodent and residues 132–153 in human), providing evidence for a common molecular basis for the well-characterized Ca2+-dependent inhibition of α-Cx class of gap junction proteins.

Materials and Methods

Prediction of CaM-binding site in connexins and molecular modeling

The topology and orientation of the transmembrane regions of the sheep Cx44 were predicted by using four different programs, including SOSUI (21), TMHMM (22), MEMSAT (23), and HMMTOP (24). Multiple sequence alignments of the mammalian gap junction proteins Cx44 (accession ID: AAD56220; sheep), Cx46 (accession ID: NP_068773; human), Cx43 (accession ID: NP_000156; human), and Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinase I (CaMKI; accession ID: AAI06755; human) and II (CaMKII; accession ID: AAH40457; human) were carried out by using the CLUSTAL W algorithm (25). The potential CaM binding sites were predicted using the CaM target database developed on the basis of >100 CaM target sequences (18). The modeled structure of CaM in complex with the CaM binding region (aa 129–150) in Cx44 was built with MODELER (26) on the basis of the high resolution structure of CaM complexed with the 1-5-10 class of CaM binding domain from CaM-dependent kinase II (CaMKII, pdb entry: 1cdm) (27).

Proteins and peptides

Unlabeled or 15N-labeled CaM was expressed and purified as described previously (20). The concentration of CaM was determined by using the ɛ276 of 3,030 M−1cm−1 (28). Dansylation of CaM was carried out as described previously (29). The modification of CaM by dansyl chloride was confirmed by ESI-MS with an increase of +233 in the molecular mass. The bound dye concentration was determined by using the λ335 of 3980 M−1 cm−1 (29). An average of ∼0.8 mol of the dansyl chromophore was incorporated per mol of CaM.

The 22-mer Cx44 peptide (Ac-129VRDDRGKVRIAGALLRTYVFNI150-NH2, denoted as Cx44129–150) and the 23-mer Cx43136–158 peptide (Ac-136KYGIEEHGKVKMRGGLLRTYIIS158-NH2, denoted as Cx43136–158), as well as a randomized control peptide (Ac-VILLDGFGYDVRKRAVITNRAR -NH2) with the same composition of amino acids as the Cx44 peptide but arranged in a different order, were synthesized by Sigma-Genosys (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and purified by preparative reversed-phase HPLC with purity >95%. The molecular weight of the synthetic peptides was determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. The peptides were acetylated at their N-termini and blocked at their C-termini with amide groups to mimic their native protein environment.

Circular dichroism measurements

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were recorded in the far ultraviolet (UV) (190–260 nm) or near UV region (250–340 nm) on a Jasco-810 spectropolarimeter at ambient temperature. The measurements were made in 10 mM Tris, 100 mM KCl, at pH 7.5 with 5 mM EGTA or 5 mM CaCl2. The background signals from the corresponding buffers were subtracted from the sample signals. In the peptide titration experiment, 1–2 μL aliquots of the peptide stock solution (∼500 μM in 10 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 100 mM KCl, pH 7.5) was gradually added to a 2-mL solution containing 0.75 μM CaM in the same buffer. The signals from the peptide itself were subtracted. All the measurements were carried out in at least triplicates. The binding constants of the synthetic peptide to CaM were obtained with a 1:1 binding model, as described previously (20). All spectra were an average of at least 15 scans. The molar ellipticity ([θ], deg cm2 dmol−1) is converted to the molar absorption coefficient (ΔɛM, M−1 cm−1) as ΔɛM = [θ]/3300. The reported mean residue weighted molar absorption coefficient (ΔɛMRW) of a helical polypeptide at 222 nm (10 M−1 cm−1) (30,31) was used to estimate the α-helical content.

Stopped-flow measurements

Stopped-flow experiments were carried out in a Jasco-810 CD spectropolarimeter (Easton, MD) equipped with a BioLogic stopped-flow apparatus (Knoxville, TN) at 25°C. The instrument dead-time is ∼2.5 ms at a drive force of ∼0.4 MPa. The optical cuvette pathlength is 0.5 cm. All the experiments were carried out in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM KCl, pH 7.5 with at least 15 traces recorded. The changes of CD signal at 222 nm were monitored with 1 ms sampling interval at the time range of 0–2 s. EGTA-induced Ca2+ dissociation was studied by mixing 100 μL of 2 μM CaM-peptide mixture (with 0.1 mM Ca) in Syringe 1 with an equal volume of 10 mM EGTA in Syringe 2 within 15 ms. The acquired data were fitted by a single exponential model.

Fluorescence measurements

Steady-state fluorescence spectra were recorded using a QM1 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Photon Technology International, Birmingham, NJ) with a xenon short arc lamp at 25°C. For dansyl-CaM fluorescence measurement, 1 mL solution containing 0.5-1 μM dansyl-CaM in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0–800 mM KCl, pH 7.5 with 5 mM Ca2+ or 5 mM EGTA was titrated with 5–10 μL aliquots of the peptide stock solution (0.5–1 mM) in the same buffer. The fluorescence spectra were recorded between 400 and 600 nm with an excitation wavelength at 335 nm and the slit width set at 4–8 nm. In the study of pH profile, the pH range (4–11) was covered by using the following buffers: sodium acetate (pH 4.0–5.5), MES (pH 5.5–7.0), Tris (pH 7.0–9.0), and CAPS (pH 9.0–11.0). The binding constant of the synthetic peptide to dansyl-CaM was obtained with a 1:1 binding model by fitting to the following equation:

| (1) |

where f is the fractional change of integrated areas of fluorescence intensity (400 nm to 600 nm), Kd is the dissociation constant for the peptide, and [P]T and [CaM]T are the total concentrations of the synthetic peptide and dansyl-CaM, respectively.

For Ca2+ stoichiometric titration, the protein or peptide stock solutions (∼1 mM) were pretreated with 50 μM EGTA to remove residual Ca2+ ions and then extensively dialyzed against buffers pretreated with Chelex-100 resin (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Protein or peptides were then diluted to the desired concentration (5–8 μM) with Chelex-treated buffers consisting of 50 mM Tris, 100 mM KCl at pH 7.5 for Ca2+ titration (λex = 277 nm, λem = 307 nm). All the glassware and plasticware used in the preparation of samples were pretreated with 10% HNO3 (optima grade, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and then rinsed thoroughly with Chelex-treated distilled water to remove the background Ca2+.

The equilibrium Ca2+ binding constants to either the N- or C-domain of CaM were determined by monitoring domain-specific intrinsic phenylalanine (λex = 250 nm, λem = 280 nm) or tyrosine fluorescence (λex = 277 nm, λem = 320 nm) at 25°C as described by VanScyoc et al. (32). In brief, 5–10 μL aliquots of 15 or 50 mM Ca2+ stock solution was titrated into the CaM (5–10 μM) or 1:1 CaM-peptide mixture in 50 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM NTA, 0.05 mM EGTA, pH 7.5. The pH change (0.02–0.04) was negligible during the titration process. Ca2+ concentration at each point was determined with the Ca2+ dye Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-5N (0.2 μM; Kd = 21.7 ± 2.5 μM; see Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material) (λex = 495 nm and λem = 520 nm). The ionized Ca2+ concentration was calculated according to the equation

| (2) |

where F is the fluorescence intensity of the dye at each titration point, and Fmin and Fmax are the fluorescence intensities of the Ca2+-free and the Ca2+-saturated dye, respectively. The Ca2+ titration of CaM data were fit to the nonlinear Hill equation

| (3) |

where f is the relative fluorescence change observed during the experiment; [Ca2+] is the concentration of free ionized Ca2+; Kd standards for dissociation constants of Ca2+ and n is the Hill coefficient.

The Gibbs free energies of Ca2+ binding to each domain of CaM (sites I and II in the N-domain or sites III and IV in the C-domain) were obtained by fitting the titration data to the model-independent two-site Adair equation (32,33)

| (4) |

where the sum of the two intrinsic free energies of the N-domain (ΔGI + ΔGII) or the C-domain (ΔGIII + ΔGIV) is given by the macroscopic free energy ΔG1 and the total free energy of Ca2+ binding (ΔGI × ΔGII × ΔGI–II or ΔGIII × ΔGIV × ΔGIII–IV) to both sites in each domain is given by the term ΔG2. The terms ΔGI–II and ΔGIII–IV accounts for any positive or negative intradomain cooperativity within the N-domain and C-domain, respectively. It is not possible to obtain intradomain cooperative energy merely from the fluorescence titration data; however, the lower limit value of cooperative free energy (ΔGc) can be estimated by assuming that both sites in each domain have equal intrinsic binding constants (ΔGI = ΔGII or ΔGIII = ΔGIV), which is defined as (32,33)

| (5) |

Fluorescence anisotropy measurement

The fluorescence anisotropy were measured with a λex = 295 nm and a λem = 345 nm for Trp fluorescence, or a λex = 335 nm and λem = 500 nm for dansyl fluorescence. An integration time of at least 20 s was used to record the signals and all the measurements were repeated at least three times. Protein samples with a concentration of 2–5 μM were titrated with the Cx peptide stock solutions (0.8–1.5 mM) in a buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 100 mM KCl at pH 7.5. The fluorescence anisotropy (R) was calculated as described previously (34,35) using the following equation:

| (6) |

where G = IHV/IHH; IHV and IHH are fluorescence intensities for horizontally excited, vertically or horizontally emitted light, respectively; IVV and IVH are fluorescence intensities for vertically excited, vertically or horizontally emitted light, respectively.

Acrylamide quenching of fluorescence

Fluorescence quenching experiments were carried out at 25°C by adding aliquots of 4 M acrylamide to the sample solution containing 2 μM protein or peptide. For dansyl fluorescence, the excitation wavelength was set at 335 nm and the emission spectra were acquired from 300 to 400 nm. For Trp fluorescence, the excitation wavelength was set at 295 nm and the emission spectra were acquired from 310 to 420 nm. The fluorescence intensity at 510 nm (dansyl fluorescence) or 345 nm (Trp fluorescence) was used for data analysis by fitting to a revised Stern-Volmer equation

| (7) |

where KSV is the dynamic or collisional quenching constant, V is the static quenching constant, [Q] is the concentration of added acrylamide, and F0 and F are the integrated fluorescence intensity in the absence and presence of acrylamide, respectively.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments were carried out on a MicroCal VP-ITC microcalorimeter (Northampton, MA). Samples are prepared and extensively dialyzed in the same buffer consisting of 20 mM PIPES, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2 at pH 6.8. All the solutions were degassed for at least 15 min before experiments. A total of 4–6 μL aliquots of peptide (400–600 μM) were injected from the syringe into the reaction cell containing 25 μM CaM in the same buffer at 5-min intervals at 25°C. The heat of dilution and mixing was measured by injecting the same amount of peptide into the reaction cell that contains the reaction buffer and then subtracting this value from the experimental value. All data were analyzed using the Microcal Origin software with a single-site binding mode that directly provided the stoichiometric information (n), Ka and enthalpy change (ΔH). Specifically, the heat (Q) of reaction at each injection is related to the enthalpy of binding, ΔHcal as follows:

| (8) |

where

| (9) |

[CaM]T and [pep]T are the total concentrations of CaM and peptide in the ITC cell with the volume Vo, respectively. Because almost no linked protonation effects were reported for the binding of peptide to CaM with PIPES buffer (36), the measured enthalpy change was considered to be the enthalpy of binding. The Gibbs free energy (ΔG) and entropy change (ΔS) were further calculated from the following equation:

| (10) |

NMR spectroscopy

Two-dimensional NMR experiments were carried out using Varian Inova 600 MHz spectrometers (Palo Alto, CA). NMR spectra were acquired with a spectral width of ∼13 ppm in the 1H dimension and 36 ppm in the 15N dimension at 35°C. For the (1H, 15N)-HSQC experiment, 0.5 mM 15N uniformly labeled CaM were titrated with 10–20 μL aliquots of stock solutions (1.5–2.0 mM) of the peptides Cx44129–150 or Cx43136–158 in a buffer consisting of 10% D2O, 100 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, and 10 mM Ca2+. The pH values of both sample solutions were carefully adjusted to 7.5 with trace amount of 2 M KOH. NMR data were processed using the FELIX98 program (Accelrys, San Diego, CA).

Transient transfection and dye transfer assay

Dye transfer assay and the measurement of [Ca2+]i with Fura-2 AM was carried out in monolayers of HeLa cells transiently transfected with Cx44-EYFP as described previously for Cx43-EYP (20). A sustained elevation in [Ca2+]i in HeLa cells transiently transfected with Cx44-EYFP was effected by adding 1 μM ionomycin to the bathing buffer as described previously (9,10,19). Cells were injected within 2 min if the [Ca2+]i remained stable for 10–15 s.

Results

Physiological effects of elevated intracellular Ca2+ on Cx44

To date there have been no studies to determine whether elevation of [Ca2+]i to the micromolar range results in an inhibition of Cx44-mediated cell-to-cell communication similar to that previously shown for Cx43 (19). Thus, experiments were conducted to determine whether elevation of [Ca2+]i regulates the function of Cx44 gap junctions when expressed in a physiological setting. Cell-to-cell dye transfer under resting and elevated [Ca2+]i in communication-deficient HeLa cells transiently transfected with Cx44-EYFP does indeed inhibit Cx44-mediated cell-to-cell communication.

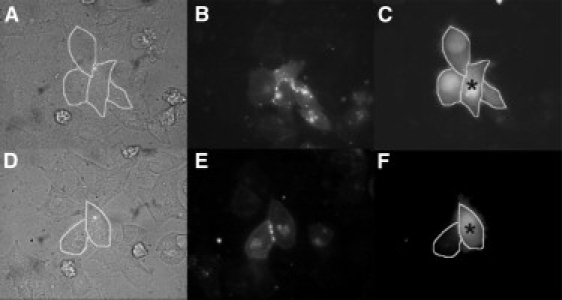

HeLa cells transiently transfected with Cx44-EYFP expressed punctate gap junction plaques at the cell-cell interface (Fig. 1, B and E) as shown by other groups in which connexin constructs with C-terminal linked EYFP is expressed in different mammalian cell lines (37). In addition, there was often additional punctuate and diffuse Cx44-EYFP fluorescence expression within the cell that was not localized to the plasma membrane. Under resting [Ca2+]i conditions (1.8 mM extracellular Ca2+ concentration), cell-to-cell communication (i.e., Lucifer Yellow cell-to-cell dye transfer) was observed between adjacent cells expressing Cx44-EYFP; every cell adjacent to the injected cell exhibiting punctate EYFP fluorescence at the plasma membrane exhibited cell-to-cell transfer of injected dye indicating that Cx44-EYFP formed functional gap junctions (Fig. 1 C). Addition of the membrane permeant polyether antibiotic ionomycin (1 μM) resulted in a significant (p < 0.001) increase of the [Ca2+]i to ∼μM concentrations known to inhibit Cx43-mediated cell-to-cell dye transfer in a CaM-dependent manner (10,19). As shown in Fig. 1 F, elevation of [Ca2+]i in Cx44-EYFP transiently transfected HeLa cells results in the inhibition of cell-to-cell dye transfer in all cells tested indicating the ability of elevated [Ca2+]i to inhibit Cx44 gap junctions (see Table 1 for summary data).

Figure 1.

A sustained elevation in [Ca2+]i inhibits Cx44-EYFP cell-to-cell dye transfer. Cx44-EYFP gap junction-mediated biochemical coupling was measured in 80%–90% confluent monolayers of transiently transfected HeLa cells by Lucifer Yellow dye transfer. Representative experimental results for both resting and elevated [Ca2+]i conditions, phase images (A and D) expressed Cx44-EYFP fluorescence (B and E), and LY dye injection results (C and F) are shown. (A–C) Resting [Ca2+]i (25 nM). (D–F) Elevated [Ca2+]i (1270 nM). The injected cell is denoted by an asterisk (∗).

Table 1.

Intracellular [Ca2+] of the dye-injected cell in Cx44-EYFP transiently transfected HeLa cells

| Treatment | [Ca2+]i∗ | Transfer rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No ionomycin | 25 ± 2 nM | 100 (n = 13) |

| Ionomycin (1 μM) | 1270 ± 140 nM | 0 (n = 6) |

The measurement of [Ca2+]i was carried out using Fura-2 AM as described previously (10).

A predicted CaM binding region in the intracellular loop of Cx44

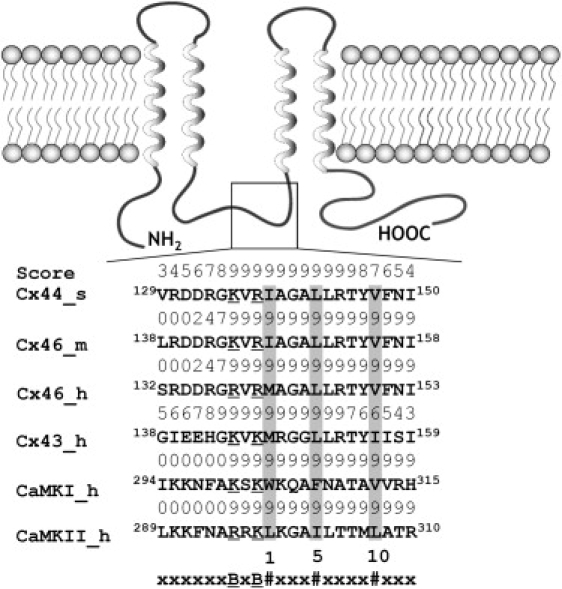

Because it has been shown previously that the elevation of [Ca2+]i in HeLa cells transiently transfected with the gap junction protein Cx43 results in the inhibition of cell-to-cell communication that requires its direct association with CaM (20), we then ask whether the Ca2+-dependent inhibition of cell-to-cell dye transfer in lens fiber cell gap junction expressing Cx44 is mediated by CaM. Although no strong sequence homology has been found among CaM targeting sequences, comparative analysis of the known CaM binding domain in CaM target proteins shows some common structural and physicochemical features, such as their distribution of hydrophobic and basic residues and their propensity to form helical structure. These properties have been used to develop a CaM target prediction tool by Yap et al. (18). Using this tool, a putative juxtamembranal CaM binding region with high predicative score was identified in the only intracellular loop of the α-class of gap junction proteins that include human Cx46 (and its sheep homolog Cx44) and Cx43 (Fig. 2). The putative CaM binding sequences in all these connexins exhibits a 1-5-10 pattern of hydrophobic residue arrangement as observed in other well-characterized CaM targeting proteins such as CaM Kinase I (38), CaM Kinase II (39), MARCKS (40), and synapsin (41). Common to other well-characterized CaM target proteins, the putative CaM binding sequences in Cx are also rich in positively charged residues that could facilitate their interaction with target proteins through electrostatic interactions.

Figure 2.

Membrane topology and the putative CaM-binding site in α-class connexins including Cx43 and Cx44 (or human Cx46). The integral membrane protein Cx is composed of four transmembrane (TM) segments (helices), two extracellular loops, one cytoplasmic loop, a short N-terminus, and a longer C-terminal tail. The predicted CaM binding sites are located in the second half of the intracellular loop between TM2 and TM3. The numeric score ranges from 1–9, representing the probability of an accurate prediction of a high affinity CaM binding site (18). Similar to the Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinase I (CaMKI) and II (CaMKII), the identified CaM-binding sequences in α-class connexins fits the 1-5-10 subclass, where each number represents the presence of a hydrophobic residue. #, Hydrophobic residues (highlighted in gray); B, basic residues (underscored); m, mouse; s, sheep; h, human.

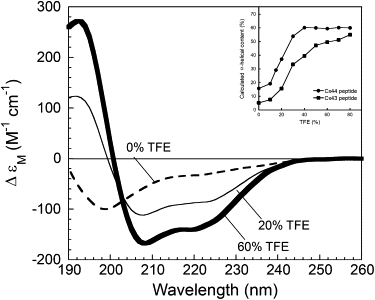

To examine its propensity to form an α-helical structure, we monitored the CD signal changes of the 22-mer Cx44 peptide Cx44129–150 derived from the intracellular loop region of Cx44 in the presence of varying amounts of trifluoroethanol (TFE), a reagent known to mimic the hydrophobic environment and induce the formation of intrinsic secondary structures in peptides (42–44). As shown in Fig. 3, the far UV CD spectrum of Cx44129–150 recorded in aqueous buffer exhibited a large negative peak at 198 nm and a less notable broad peak at ∼220–230 nm, indicating that the peptide is largely unstructured. In the presence of 20% TFE the peptide adopts some α-helical content, as shown by two negative peaks at 208 and 222 nm and a large positive peak ∼195 nm. With increasing amounts of TFE, the calculated α-helical content of Cx44129–150 increased from 17% to 60% and reached a plateau in the presence of >40% TFE (Fig. 3, inset). Such a TFE-dependent increase in α-helical content (from 5% to 55%) has also been reported by us previously for the CaM binding Cx43 peptide (20). Compared to this Cx43136–158 peptide, Cx44129–150 was relatively more structured in aqueous solution and formed 5% more helical structure in the presence of 80% TFE (Fig. 3, inset). Thus, the predicted CaM binding sequences in both Cx44 and Cx43 possess a strong propensity to form α-helical structure.

Figure 3.

Far UV CD spectra of the synthetic peptide Cx44129–150 with 0% (dashed line), 20% (thin solid line), and 60% (bold solid line) TFE (v/v). The inset shows calculated α-helical content as a function of TFE concentration for the peptides Cx44129–150 (●) and Cx43136–158 (■).

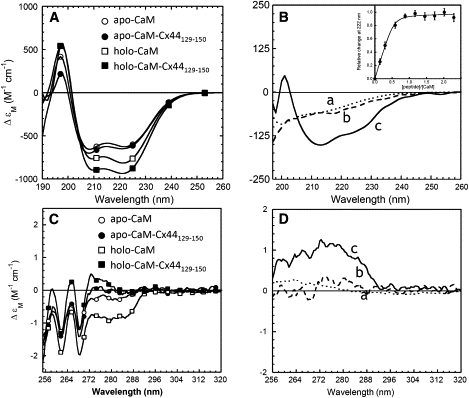

Structural changes during the formation of the CaM-peptide complex

To elucidate the structural and conformational changes during the formation of the CaM-peptide complex, we monitored the effects of CaM binding on the conformation of the peptide by CD spectroscopy, and meanwhile, investigated the effects of peptide binding on the structure of CaM by means of NMR spectroscopy. As seen in Fig. 4 A, the addition of the Cx44 peptide to Ca2+-saturated CaM (holo-CaM) at a 1:1 molar ratio resulted in a 10%–20% increase in the negative ellipticity ∼205–225 nm, with the ɛM value at 222 nm increasing by a factor of 1.15. Because the α-helicity of CaM remains almost unchanged when bound to a target peptide (45,46), the increase in the negative ellipticity could then be primarily attributed to the CaM-bound peptide itself. In contrast, such a major increase in CD signal intensity was not observed after the addition of the Cx44 peptide to Ca2+-depleted CaM (apo-CaM), implying that the change in ellipticity is indeed a Ca2+-dependent event. By comparing the difference CD spectrum (Fig. 4 B) of apo-CaM- (curve b) or holo-CaM-bound peptide (curve c) to the far UV CD spectrum of Cx44129–150 in aqueous solution (curve a), it is evident that more helical content was formed on the binding of holo-CaM, but not apo-CaM, to the peptide Cx44129–150. By using the reported ΔɛMRW value at 222 nm (10 M−1 cm−1) (31), we calculated that the α-helical content of the peptide increased from ∼17% to ∼55% when bound to holo-CaM, which was comparable to the α-helical content of the free Cx44129–150 peptide in the presence of >40% TFE (Fig. 3, inset). Such significant changes further enabled us to estimate the peptide binding affinity by monitoring the net CD signal change at 222 nm. As shown in the inset of Fig. 4 B, the net increase of CD signal reached saturation when the peptide to holo-CaM ratio reached ∼1:1. By fitting the titration data with a 1:1 binding model, a dissociation constant (Kd) of 15 ± 6 (n = 3) was obtained in 10 mM Tris, 100 mM KCl, pH 7.5.

Figure 4.

CD studies of the interaction between the Cx44 peptide and CaM. (A) Far UV circular dichroism spectra of CaM in the presence of 5 mM EGTA (○, apo-CaM) or CaCl2 (□, holo-CaM), and a 1:1 CaM-peptide mixture with 5 mM EGTA (●, apo-CaM-peptide) or CaCl2 (■, holo-CaM-peptide). (B) The far UV CD spectra of Cx44129–150 (dotted line, curve a) and the calculated difference spectrum with 5 mM EGTA (dashed line, curve b) or Ca2+ (solid line, curve c). The inset showed the relative change of CD signals at 222 nm as a function of the synthetic peptide in the presence 5 mM Ca2+. (C) Near UV CD spectra of CaM in the presence of 5 mM EGTA (○, apo-CaM) or CaCl2 (□, holo-CaM), and 1:1 CaM-peptide complex with 5 mM EGTA (●, apo-CaM-peptide) or 5 mM CaCl2 (■, holo-CaM-peptide). (D) The near UV circular dichroism spectra of Cx44129–150 (dotted line, curve a) and the calculated difference spectrum with 5 mM EGTA (dashed line, curve b) or Ca2+ (solid line, curve c). All the spectra were recorded at room temperature in 10 mM Tris, 100 mM KCl, at pH 7.5.

We further studied the interaction between CaM and Cx44129–150 with near UV spectroscopy, a technique that is sensitive to the local chemical environment around aromatic residues and is used widely in the study of protein tertiary packing and conformational changes (47). Fig. 4 C shows the near UV (255–320 nm) CD spectra of CaM in complex with Cx44129–150 in the absence or presence of Ca2+. The holo-CaM showed two prominent negative bands at 262 and 268 nm, which arise from the eight Phe residues in CaM, as well as a broad negative band at 270–290 nm that derives from the two Tyr residues in the C-domain of CaM (48). The addition of Cx44129–150 to the holo-CaM at a 1:1 molar ratio led to a striking decrease in the negative ellipticity below 290 nm. In contrast, no significant change was observed when Cx44129–150 was added to apo-CaM. By assuming that the CD spectrum of CaM itself remains unaltered, the difference spectra should represent the spectra of the bound peptide. As seen in Fig. 4 D, both the near UV CD spectrum of the free peptide (curve a) and the spectrum of apo-CaM-bound peptide (curve b) showed negligible CD signals, suggesting considerable conformational freedom of the aromatic residues (Tyr146 and Phe148, no Trp) in the free peptide and the apo-CaM-bound peptide. However, the spectrum of holo-CaM-bound peptide (curve c) exhibited strong positive CD signals below 290 nm. Because the conformation of the two Tyr residues in CaM has been reported to be minimally altered on binding peptide (45), the observed positive CD signal in the difference spectrum would arise mainly from the peptide Cx44129–150 because of the immobilization of its aromatic residues (Tyr146 and Phe148) on the formation of a more rigid structure in the complex. Thus, all these CD data suggest that the peptide Cx44129–150 undergoes considerable changes in both secondary and tertiary structure when bound to holo-CaM and further imply a Ca2+-dependent stoichiometric interaction between CaM and the Cx44129–150 peptide.

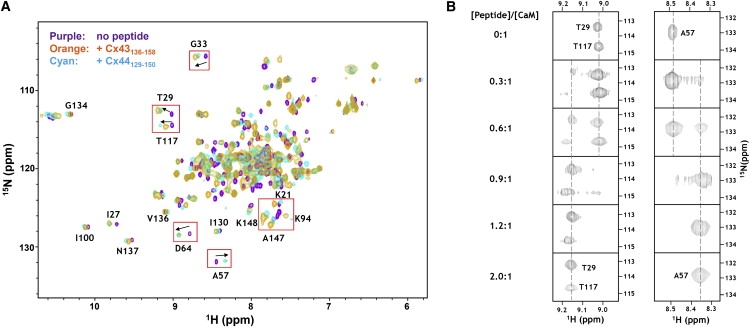

Next, we examined the peptide-induced structural changes in CaM by monitoring the chemical shifts changes of CaM backbone amides with (1H-15N)-HSQC spectroscopy. Titration was carried out by adding unlabeled peptide to 15N-labeled CaM. Because the chemical shifts of protein amide report even subtle conformational changes occurring at the interacting interface, chemical shift perturbations can be used to identify the interaction surface after complex formation. As shown in Fig. 5 A, the HSQC spectrum of holo-CaM is almost identical to previously described spectra (45,49,50), allowing us to unambiguously assign a number of dispersed peaks. In perfect agreement with our previous observation on addition of the Cx43 peptide (20), the addition of Cx44129–150 to holo-CaM led to global chemical shift perturbations that involved both the N-domain (e.g., T29, G33, N53, A57, and D64) and C-domain (e.g., K94, G113, T117, K148, and V136) of CaM, which implies that there are large conformational changes associated with this interaction. During the titration, a progressive disappearance of the amide signals of the unbound CaM was accompanied by the concomitant emergence of a new set of peaks arising from the peptide-bound CaM (Fig. 5 B). Intermediate peaks between the bound and unbound peaks were not observed, indicating a slow exchange process in which the exchange rate of the bound and unbound states is smaller than the amide frequency difference between the two states. Such slow-exchanging phenomena have been observed after high affinity protein-protein or protein-peptide association (i.e., interactions with submicromolar affinities) (51), and is consistent with the dissociation constants determined with other methods (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Monitoring the interaction between CaM and the Cx peptides by (1H, 15N)-HSQC spectroscopy. (A) An overlay of HSQC spectra of holo-CaM (purple) with the spectrum of the holo-CaM-Cx44129–150 complex (cyan) or the holo-CaM-Cx43136–158 complex (orange). Representative peaks that exhibited significant movement on peptide binding were framed by boxes. (B) Titration of holo-CaM with Cx44129–150. Note that the progressive disappearance of peaks was accompanied by the concomitant appearance of corresponding peaks at new positions.

Table 2.

Binding affinities of the Cx44 peptide to CaM

| KCl (mM) | Dissociation constants (Kd, nM) | |

|---|---|---|

| 5 mM Ca2+ | 0 | 31 ± 2∗ |

| 100 | 49 ± 3∗ | |

| 15 ± 6† | ||

| 159 ± 50‡ | ||

| 610 ± 83§ | ||

| 830 ± 140¶ | ||

| 200 | 128 ± 13∗ | |

| 5 mM EGTA | 0 | 414 ± 21∗ |

| 100 | >5000∗ | |

| 200 | nd |

All experiments were repeated for at least three trials.

nd, not detectable.

Dansyl-CaM fluorescence in 50 mM Tris, 0–200 mM KCl, pH 7.5.

Far UV CD measurement in 10 mM Tris, 100 mM KCl, pH 7.5.

Dansyl fluorescence anisotropy measurement in 50 mM Tris, 100 mM KCl, pH 7.5.

Dansyl-CaM fluorescence in 20 mM PEPES, 100 mM KCl, pH 6.5.

Isothermal titration calorimetry measurement in 20 mM PIPES, 100 mM KCl, pH 6.8.

Revealing CaM-peptide interaction with fluorescence spectroscopy

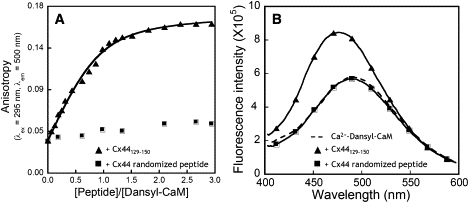

Dansyl-CaM has been used frequently as a reporter for CaM-peptide interaction because of its sensitivity to the changes in the surrounding chemical environment (20,29,52,53). With the emission maxima at 500–510 nm, the emission contribution to the dansyl fluorescence from any intrinsic aromatic residues is negligible during peptide titrations. We first examined the dansyl fluorescence anisotropy changes on titration with the peptide Cx44129–150 or the Cx44 randomized control peptide that has been predicted to abrogate the binding to CaM. Fluorescence anisotropy, which is dependent on the rotational correlation time of respective fluorophores in the sample, reflects the hydrodynamic properties of macromolecules and is widely used to show protein-ligand interaction (35,54). As shown in Fig. 6 A, the dansyl fluorophore conjugated with holo-CaM (16.7 kDa) had a relatively small anisotropy of 0.035. With the addition of the peptide Cx44129–150, the anisotropy was gradually increased to 0.161 because of the formation of a larger complex (19.3 kDa) and the resultant slower tumbling in solution. By assuming a single binding process, an apparent dissociation constant of 159 ± 50 nM was obtained. In contrast, the addition of the randomized peptide did not significantly change the anisotropy of the dansyl fluorophore. Therefore, it is the specific arrangement in the sequence but not the composition of the sequence that accounts for the interaction between holo-CaM and Cx44129–150.

Figure 6.

The dansyl fluorescence (A) anisotropy and (B) emission spectra of dansylated CaM at increasing concentration of Cx44129–150 (▴) or the Cx44 randomized control peptide (■). Dansyl-CaM with a concentration of 2 μM was titrated with the peptide solutions in a buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 100 mM KCl at pH 7.5. The fluorescence anisotropy were measured at λex = 335 nm and λem = 500 nm with an integration time of 20 s.

We further carried out peptide titration with dansyl-CaM by monitoring the fluorescence emission between 400 nm and 600 nm. In the presence of EGTA or Ca2+, dansylated CaM exhibits fluorescence maxima at 510 nm and 500 nm, respectively (Fig. 7, A and B insets). Under salt-free conditions, the addition of Cx44129–150 to Ca2+-loaded dansyl-CaM resulted in enhancement of dansyl fluorescence by a factor of 1.45 and a 17-nm blueshift of the emission peak (Fig. 7 A), indicating that the dansyl moieties entered a more hydrophobic environment on the complex formation. As a stringent control, the addition of the Cx44 randomized peptide did not induce significant changes in the spectrum of dansyl-CaM (Fig. 6 B). In the presence of EGTA and the absence of added salt, the dansyl fluorescence intensity also increased by ∼50%, but the fluorescence maxima did not change (Fig. 7 B, inset), strikingly different from the behavior when it bound to Ca2+-loaded dansyl-CaM. The derived dissociation constants in the absence of added salt were 31 ± 2 nM (in the presence of Ca2+) and 414 ± 21 nM (in the presence of EGTA), respectively. Although the dissociation constant of Cx44129–150 binding to Ca2+-saturated dansyl-CaM in the presence of physiological concentrations of added salt (100 mM KCl) (49 ± 3 nM) was similar to that in the absence of salt, the binding affinity of Cx44129–150 to dansyl-CaM in the presence of EGTA was at least 100-fold (Kd: >5 μM) weaker in the presence of physiological concentrations of salt (Table 2). Moreover, with increasing concentration of salt (>150 mM KCl), the enhancement of fluorescence intensity can hardly be detected in the presence of EGTA because of the weaker interaction. Given that the intracellular CaM concentration is ∼9 μM (55) and CaM interacts with over 300 target proteins in vivo (56), such weak or unspecific interactions between the peptide and Ca2+-depleted CaM would be of little physiological relevance.

Figure 7.

Interaction of Cx44129–150 with dansyl-CaM monitored by steady-state fluorescence. (A) The titration curve of dansyl-CaM (1.25 μM) with Cx44129–150 in the presence of 5 mM Ca2+ in a salt-free buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5. The inset showed the fluorescence spectrum of dansyl-CaM in the presence (solid line) or absence (dashed line) of equivalent amount of Cx44129–150. (B) The titration curve of dansyl-CaM with Cx44129–150 in the presence of 5 mM EGTA in a salt-free buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5. The inset showed the fluorescence spectrum of dansyl-CaM in the presence (solid line) or absence (dashed line) of equivalent amount of Cx44129–150. The emission maxima were indicated by arrows. (C) Plot of −logKd as a function of varying amount of KCl in 5 mM CaCl2, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5. (D) pH dependence of Cx44129–150 binding to CaM. The binding affinities were derived from the peptide titration curve of dansyl-CaM.

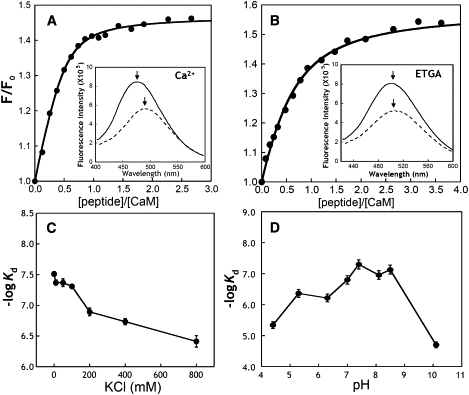

Thermodynamics of CaM-peptide interaction

ITC experiments were further carried out to obtain the stoichiometry, binding affinity, and thermodynamics of the interaction between CaM and Cx44129–150. Representative calorimetric traces of titrations are shown in Fig. 8. For Cx44129–150, the binding event was found to be exothermic (ΔH = −4.79 kJ mol−1) and entropically favorable (ΔS = 100.29 J mol−1 K−1) with an association constant of Ka = 1.2 ± 0.2 × 10−6 M−1 (or Kd = 830 ± 140 nM). Thus, the interaction seems to be both enthalpically and entropically driven with a ΔG of −34.68 kJ mol−1. Because the enthalpic terms represent the forces of hydrogen bonds, van der Waals and electrostatic interactions, whereas entropy mainly reflects the hydrophobic interaction, it is evident that all these forces are contributing in concert to promote the interaction between CaM and Cx44129–150. Consistent with our peptide titration data monitored by far UV CD spectroscopy (Fig. 4 B) and NMR spectroscopy (Fig. 5 B), the Cx44129–150 peptide specifically bound to Ca2+-saturated CaM at an ∼1:1 ratio (n = 1.3 ± 0.2). In addition, the binding affinity obtained from ITC at pH 6.8 was comparable to the binding affinity determined with dansyl-CaM (610 ± 83 nM, Table 2) at comparable pH values.

Figure 8.

(A) ITC microcalorimetric traces and the derived isotherms of 25 μM CaM titrated with ∼500 μM Cx44129–150 in 20 mM PIPES, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, pH 6.8 at 25°C. (B) Comparison of the enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (−TΔS) contributions to the Gibbs free energy (ΔG) on the formation of the holo-CaM-peptide complexes. ∗Data from Brokx et al. (36).

Salt and pH dependence of CaM-Cx44129–150 interaction

To gain further insight into the possible role of electrostatic interactions in mediating the CaM-peptide interaction, the effects of varying concentrations of salt and pH on the binding affinity of CaM for Cx44129–150 were also examined. During complex formation between two oppositely charged macromolecules, an increase in the ionic strength is expected to decrease the binding affinity mainly because of screening of electrostatic interactions. As shown in Fig. 7 C, the binding affinity (represented as −logKd) decreased by almost one magnitude of order (from ∼7.5 to ∼6.5) as the KCl concentration was increased from 0 to 800 mM, with a notable plateau between 10 to 100 mM. In addition, the binding affinity of the peptide to Ca2+-CaM exhibited a pH-dependent increase between pH 5.0 to 9.0 (Fig. 7 D). As expected, the binding affinity at pH values near the isoelectric points of CaM (4.2) or the peptide (10.8) was drastically weakened with the difference in the affinity being ∼2 orders of magnitude. Taken together, both the salt- and pH-dependence of the interaction between CaM and Cx44129–150 indicates that electrostatic interactions are one of the main forces driving complex formation.

Monitoring domain specific interaction using CaM Trp mutants

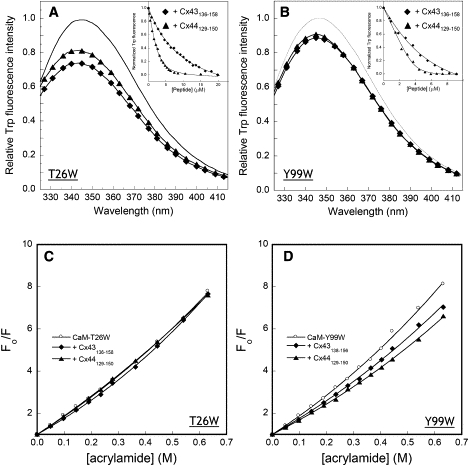

By substituting the EF-loop position 7 with tryptophan, the intrinsic Trp fluorescence of two CaM mutants, i.e., T26W (in EF-loop I) and Y99W (EF-loop III), has been shown to report the binding of metal ions to the N- and C-domain of CaM (57). We also tested whether the intrinsic fluorophore can be used to reflect the domain-specific interaction between CaM and the Cx peptides in the presence of Ca2+. Again, fluorescence anisotropy studies were first carried out to confirm the formation of CaM-peptide complexes. As expected, it was found that the addition of either of the two Cx peptides increased fluorescence anisotropy significantly (Table 3). Furthermore, the addition of both Cx43136–158 and Cx44129–150 to CaM mutant T26W led to a decrease of fluorescence intensity by 20%–25% and blueshift of the emission peak by 1–2 nm (Fig. 9 A). Similar changes were observed when adding to the other CaM mutant Y99W (Fig. 9 B). Peptide titration data showed that the Cx44 peptide bound to Y99W (C-domain) with affinities over eightfold stronger than its interaction with T26W (N-domain). For the Cx43 peptide, a similar trend was observed and the binding affinity to Y99W was 2.4-fold stronger than its affinity to T26W (Table 3). Fluorescence quenching studies using acrylamide indicated that the presence of Cx peptides decreased the dynamic quenching constants (KSV) by 15%–25% because of the shielding of Trp residues from solvents in either of the two CaM mutants (Table 3, Fig. 9, C and D) on complex formation. Such changes were consistent with the slight blueshift of the emission maxima. Thus, it seemed that the Cx peptides would interact with the C-domain of holo-CaM with higher affinity.

Table 3.

Trp fluorescence properties of CaM mutants on binding of Cx peptides

| Peptide | T26W∗ |

Y99W∗ |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λem (nm) | Anisotropy† | KSV (M−1)‡ | Kd (μM)§ | λem (nm) | Anisotropy† | KSV (M−1)‡ | Kd (μM)§ | |

| No peptide | 345 | 0.093 ± 0.010 | 7.7 ± 0.2 | na | 346 | 0.074 ± 0.007 | 7.9 ± 0.3 | na |

| Cx44129–150 | 344 | 0.118 ± 0.011 | 6.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 345 | 0.118 ± 0.007 | 6.1 ± 0.2 | < 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| Cx43136–158 | 343 | 0.112 ± 0.011 | 6.3 ± 0.3 | 6.6 ± 1.2 | 345 | 0.110 ± 0.008 | 6.8 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 1.1 |

All values were from at least three trials.

na,

The intrinsic Trp fluorescence from CaM variants T26W and Y99W was used to probe domain-specific interaction between CaM and Cx peptides.

Anisotropy of Trp fluorescence was calculated using Eq. 6.

The dynamic quenching constants (KSV) were obtained from acrylamide quenching experiments by fitting the data with Eq. 7.

The dissociation constants were obtained from peptide titration by monitoring domain-specific Trp fluorescence signal changes.

Figure 9.

Use of CaM mutants to monitor the interaction between CaM and Cx peptides. (A and B) Interaction of the Cx peptides with 5 μM CaM mutants T26W and Y99W. Fluorescence emission was acquired from 325 nm to 415 nm with excitation wavelength at 295 in the absence (solid line) or presence of Cx44129–150 (▴) and Cx43136–158 (♦). The inset showed the normalized signal changes (integrated area from 325 nm to 415 nm) as a function of added Cx peptides in 50 mM Tris, 5 mM Ca Cl2, 100 mM KCl at pH 7.5. (C and D) Acrylamide quenching of the tryptophan fluorescence in CaM mutants T26W and Y99W in the absence (○) or presence of Cx44129–150 (▴) or Cx43136–158 (♦).

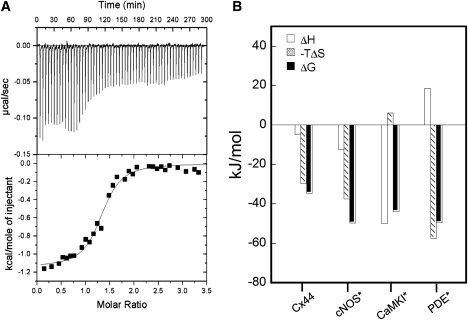

Effects of peptide binding on Ca2+-binding properties of CaM

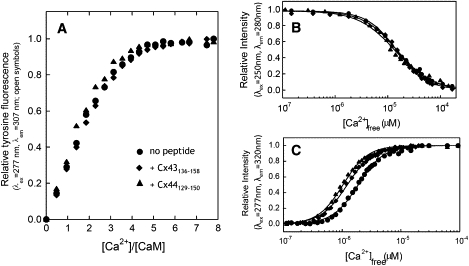

To elucidate the relationship between metal binding and target protein activation/inhibition, we carried out both stoichiometric and equilibrium titration of CaM with and without the bound Cx peptides. We first examined whether the target binding alters the stoichiometry of metal ion binding to CaM by monitoring tyrosine fluorescence after the addition of Ca2+ to apo-CaM or peptide + apo-CaM. As shown in Fig. 10 A, with the addition of CaCl2, the tyrosine fluorescence of the apo-CaM or the apo-CaM-Cx peptide complexes showed similar changes with an ∼2-fold enhancement in intensity that saturated at a Ca2+/protein ratio of 4.

Figure 10.

Ca2+ titration of CaM with and without the bound Cx peptides. (A) Stoichiometric Ca2+ titration of CaM (●), and CaM bound to the peptide Cx44129–150 (▴) or Cx43136–158 (♦) in 50 mM Tris, 100 mM KCl at pH 7.5. (B and C) Equilibrium Ca2+ titration of CaM (●) and CaM in complex with Cx44129–150 (▴) or Cx43136–158 (♦) in 100 mM KCl, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5. Domain-specific (B) intrinsic phenylalanine (λex = 250 nm, λem = 280 nm) or (C) tyrosine fluorescence (λex = 277 nm, λem = 320 nm) was monitored to report the equilibrium Ca2+-binding constants of N- or C-domain of CaM, respectively. The Ca2+ indicator dye Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-5N was used to measure the ionized Ca2+ concentration. All the experiments were repeated at least in triplicate.

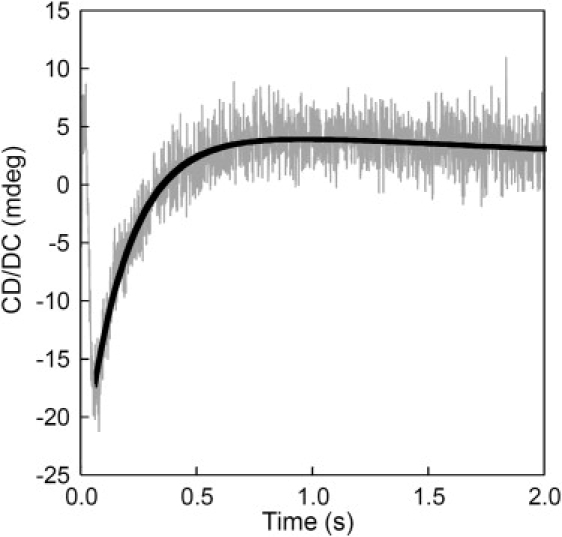

Equilibrium Ca2+ titrations were carried out to obtain macroscopic Ca2+-binding constants for both domains of CaM by monitoring domain-specific fluorescence changes as described by VanScyoc et al. (32) and Theoharis et al. (35). On Ca2+ binding to sites I and II within the CaM N-domain, a decrease in phenylalanine fluorescence was observed (Fig. 10 B) and an apparent dissociation constant of 14.59 ± 0.03 μM, as well as a Hill coefficient of 1.5 ± 0.1, was obtained by fitting the titration curve with a nonlinear Hill equation (Table 4). The addition of Cx44129–150 or CX43136–158 seemed to have little effect on the titration curve and the Hill coefficient, with Ca2+-binding affinities of 11.62 ± 0.05 μM and 14.48 ± 0.02 μM, respectively (Table 4). Next, Ca2+-binding to sites III and IV in the C-domain of CaM was explored by monitoring the increase in tyrosine fluorescence (Fig. 10 C). As mentioned earlier, the tyrosine fluorescence of the peptide remained unchanged during metal titration, so it was possible to assign the fluorescence change to CaM in the CaM-peptide complexes. In the absence of peptide, the C-domain of CaM has a dissociation constant of 1.95 ± 0.03 μM with a Hill coefficient of 2.1 ± 0.1 (Table 4). The Ca2+-binding affinities of the C-domain of Cx44129–150- and Cx43136–158-bound CaM decreased to 0.93 ± 0.02 μM and 1.16 ± 0.02 μM, respectively (Table 4). It is well recognized that the Ca2+ affinity of CaM is significantly enhanced on binding to its target receptor protein because of a slower dissociation rate of Ca2+ from the CaM-target complexes than from CaM alone (58–60). To further confirm this, we measured the rapid kinetics of EGTA-induced Ca2+ dissociation from the CaM-Cx44129–150 complex by monitoring the CD signal at 222 nm using a stopped-flow apparatus. Previous stopped-flow measurements reported two distinct processes for the dissociation of Ca2+ from CaM. Brown et al. (60) reported an observed rate constant of >800 s−1 and ∼10 s−1 for EGTA-induced Ca2+-dissociation from the N-and C-domain of CaM by monitoring fluorescence signal changes. By monitoring the CD signals, the observed rate constant for the EGTA-induced dissociation of Ca2+ from CaM could not be measured by this instrument because the global release of Ca2+ is too fast to be captured with an instrumental dead time of 2.5 ms (data not shown). It seems likely that the observed dissociation process using CD reflects the averaged dissociation rates from both the N- and C-domains. However, after CaM-Cx44129–150 complex formation, an observed dissociation rate (kobs) of 5.3 ± 0.2 s−1 was obtained by fitting the stopped-flow traces with a single-component exponential decay function (Fig. 11).

Table 4.

Effects of Cx peptides binding on the metal-binding properties of CaM

| Peptide | N-domain (sites I and II)∗ |

C-domain (sites III and IV)† |

EGTA-induced Ca2+ release‡ (kobs, s−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd (μM) | nHill | Kd (μM) | nHill | ||

| None | 14.59 ± 0.03 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.95 ± 0.03 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | > 400.0 |

| Cx44129–150 | 11.62 ± 0.05 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.93 ± 0.02 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 0.2 |

| Cx43136–158 | 14.48 ± 0.02 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.16 ± 0.02 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | > 400.0 |

All experiments were repeated for at least three trials. Kd and the Hill coefficient (nHill) were obtained by fitting the titration curve with Eq. 3.

Phenylalanine fluorescence (λex = 250 nm; λem = 280 nm) reports the Ca2+ binding to the N-domain of CaM.

Tyrosine fluorescence (λex = 277 nm; λem = 320 nm) reflects the Ca2+ binding to the C-domain of CaM.

The observed rates of EGTA-induced Ca2+ release from CaM or the CaM-peptide complexes were obtained by fitting the far UV CD signal at 222 nm as a function of time using a single exponential function.

Figure 11.

Stopped-flow trace for the EGTA-induced dissociation of Ca2+ from the CaM-Cx44129–150 complex. Syringe 1 contained 2 μM CaM-peptide (1:2) mixture with 0.1 mM Ca and syringe 2 consisted of equal volume of 10 mM EGTA.

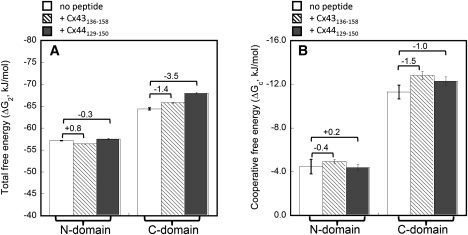

To analyze the effects of Cx peptides binding on the Ca2+-binding energies of CaM, the equilibrium titration curve was further fitted with a two-site Adair function that resolved total binding free energies (ΔG2) of −57.2 ± 0.1 KJ/mol and −64.4 ± 0.3 KJ/mol for the N- and C-domains of CaM, respectively (Table 5, Fig. 12). Given that the standard deviation in these experiments ranged from 0.1–0.8, only those changes larger than ±0.8 KJ/mol could be considered significant. For Ca2+-binding to the N-domain of CaM, the ΔG2 value changed by +0.8 KJ/mol to −56.4 ± 0.1 KJ/mol on the binding of Cx43136–158 and by −0.3 KJ/mol to −57.5 ± 0.1 KJ/mol on the binding of Cx44129–150. For Ca2+-binding to the C-domain of CaM, the change in ΔG2 was −1.4 KJ/mol for Cx43136–158 versus −3.5 KJ/mol for Cx44129–150 (Fig. 12 A). The Hill coefficient in Table 4 could give an estimation of intradomain cooperativity; however, this term only reflects the macroscopic properties of multiple Ca2+-binding processes and is not directly related to the intradomain cooperative energy changes (61). A more accurate and quantitative way to analyze the intradomain cooperativity could be achieved by comparing the lower limit of intradomain cooperative energy (ΔGC) (Fig. 12 B). The changes in ΔGC (or ΔΔGC) for the N-domain of CaM in the presence and absence of peptides were −0.4 KJ/mol for Ca2+-binding to the CaM-Cx43136–158 complex versus +0.2 KJ/mol for Ca2+-binding to the CaM-Cx44129–150 complex. The cooperative free energies of Ca2+-binding to the C-domain of CaM were changed by −1.5 KJ/mol by the Cx43136–158 peptide and −1.0 KJ/mol by the Cx44129–150 peptide, respectively.

Table 5.

Effects of Cx peptides binding on the free energies of Ca2+ binding to CaM

| Peptide | N-domain (sites I and II) |

C-domain (sites III and IV) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔG1∗ (kJ/mol) | ΔG2∗ (kJ/mol) | ΔGc† (kJ/mol) | ΔG1∗ (kJ/mol) | ΔG2∗ (kJ/mol) | ΔGc† (kJ/mol) | |

| None | −28.1 ± 0.4 | −57.2 ± 0.1 | −4.5 ± 0.7 | −28.3 ± 0.3 | −64.4 ± 0.3 | −11.3 ± 0.6 |

| Cx44129–150 | −28.3 ± 0.1 | −57.5 ± 0.1 | −4.3 ± 0.2 | −29.5 ± 0.2 | −67.9 ± 0.1 | −12.3 ± 0.4 |

| Cx43136–158 | −27.4 ± 0.2 | −56.4 ± 0.2 | −4.9 ± 0.3 | −28.3 ± 0.2 | −65.8 ± 0.2 | −12.8 ± 0.3 |

All the experiments were repeated for at least three trials in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 5 mM CaCl2, 100 mM KCl at pH 7.5.

ΔG1 and ΔG2 were obtained by fitting the fluorescence titration data at 25°C with Eq. 4. ΔG1 reflects the sum of the free energy of the first ligand binding to each domain. Each domain contains two Ca2+-binding sites. ΔG2 standards for the total free energy for the binding of two Ca2+ ions to either N- or C-domain of CaM and accounts for any cooperativity between the two sites in each domain.

By assuming that both sites in each domain have equal intrinsic Ca2+-binding affinities, the lower limit for changes in free energy due to cooperative Ca2+ binding (ΔGc) was calculated according to Eq. 5.

Figure 12.

Comparison of the total free energies ΔG2 (A) and the intradomain cooperative free energies ΔGc (B) of Ca2+ binding to each domain of CaM with and without the Cx peptides. The energies were obtained from the equilibrium titration curves shown in Fig. 10, B and C, according to Eqs. 4 and 5. ΔG2 standards for the total free energy for the binding of two Ca2+ ions to either N- or C-domain of CaM and accounts for any cooperativity between the two sites in each domain. By assuming that both sites in each domain have equal intrinsic Ca2+-binding affinities, the lower limit for changes in free energy due to cooperative Ca2+ binding (ΔGc) was calculated according to Eq. 5. The changes in free energies after and before Cx peptides binding were indicated. All the experiments were repeated for at least three trials.

Discussion

There is much evidence in the literature describing the Ca2+-sensitive uncoupling of lens gap junctions, with the [Ca2+]i varying widely from the nanomolar range (12,62–64) to low micromolar (65,66) to hundreds of micromolar (67–69). We have shown previously that Cx43-mediated cell-to cell communication is inhibited when [Ca2+]i is elevated above physiological resting concentrations (10). In this study, we show that HeLa cells transiently transfected with the lens fiber cell connexin protein Cx44 coupled to a C-terminal EYFP tag, is capable of forming dye-coupled gap junctions. Both LY and AlexaFluor594 (data not shown) are passed through Cx44-EYFP gap junctions, and this dye transfer is inhibited by micromolar [Ca2+]i, consistent with experimental [Ca2+]i values and the expression pattern of Cx44 in the lens. The biochemical data presented herein support these physiological results.

Our previous studies have shown a Ca2+-dependent stoichiometric interaction between the intracellular loop region of Cx43 and CaM. Such an interaction seems essential for the Ca2+-regulated inhibition of gap junctions channels (20). In addition, Ca2+-dependent association of CaM with rat Cx32 (13–16), fish Cx35, mouse Cx36 (70), and human Cx50 (71) have been reported. In this study, we further characterize the interaction between CaM and the intracellular loop region of another member of the α-class gap junctions, Cx44 (the sheep homolog of rodent Cx46) and compare the properties of CaM binding to Cx44129–150, a peptide derived from this region to the binding of CaM to the homologous Cx43-derived peptide Cx43136–158. Not surprisingly, the association of Cx44129–150 and CaM seems to be very similar to the association of CaM and Cx43136–158.

The data reported in this study show that the binding of CaM induced significant changes in the secondary and tertiary structure of both Cx43136–158 and Cx44129–150. Sequence alignment results indicate that the interaction between CaM and the α-Cx class falls into the 1-5-10 class (Fig. 2), which is similar to the well-characterized CaM-binding sites within CaMKI (38,72) and CaMKII (39). After the formation of the CaM-Cx complexes in the presence of Ca2+, the helical contents in Cx43136–158 and Cx44129–150 increased 48% and 38%, respectively. In addition, the appearance of prominent near UV CD bands at 270–280 nm indicates the formation of a more rigid structure for the peptides after their binding to Ca2+-CaM.

The binding of target peptides leads to extensive structural rearrangement in CaM and the embracing mode of interaction has been reported most commonly, as best exemplified by myosin light chain kinases (45,46) and CaM-dependent kinases (38,39). This binding involves the unwinding of the central linker in CaM, enabling the N- and C-domains of CaM to accommodate the target peptides in a “wrapping-around” fashion. Our NMR chemical shift perturbation data clearly demonstrate that both domains of CaM undergo structural changes on binding of either Cx43136–158 or Cx44129–150. During the titration of Cx43136–158 to holo-CaM, the chemical shift changes of holo-CaM are characteristic of fast exchange on the NMR timescale (20). In contrast, a slow exchange process is observed on titration of CaM with Cx44129–150. Such exchange difference on the NMR timescale implies that the binding affinity of Cx44129–150 to holo-CaM is stronger than that of Cx43136–158. The validity of this conclusion is confirmed by comparing the dissociation constants derived from the Cx43136–158 and Cx44129–150 titration curves by far UV CD spectroscopy. The dissociation constant for Cx43136–158 (750 ± 120 nM) (20) is 50-fold larger than that for Cx44129–150 (15 ± 6 nM; see Table 2). The striking difference in binding affinities could be due to the difference in the primary sequences or more likely because we are using peptides that do not comprise the total CaM binding domain of these two Cx proteins. It also may be relevant that the Cx43136–158 peptide, which contains only ∼7% helical content, is not as well structured as Cx44129–150 peptide (15% helical content) in aqueous solution.

In addition to our conformational and structural studies, we also carried out ITC analyses to characterize the thermodynamics underlying the CaM-Cx44129–150 interaction. Our ITC data suggest that the Ca2+-CaM- Cx44129–150 interaction is both enthalpically and entropically favorable. It seems that the binding of Cx44129–150 to Ca2+-CaM is driven primarily by a favorable entropy because the enthalpic change (ΔH) contributes <15% to the total free energy change (ΔG), which is similar to the association of CaM with the constitutive cerebellar nitric-oxide synthase (36). The favorable enthalpic change implies that forces such as hydrogen bonds, van der Waals and electrostatic interactions are contributing to the CaM-Cx44129–150 interaction. The contribution of electrostatic interactions has been evaluated by comparing the affinities of Cx44129–150 binding to CaM in the presence of different concentrations of salt and pH values. As expected, the binding affinities of Cx44129–150 to CaM are significantly lowered almost 10-fold when the concentrations of KCl increase from 0 to 800 mM. In contrast, the binding affinity of Cx44129–150 to CaM exhibits a strong pH-dependence between pH 5 and 9. Thus, the association of CaM with Cx44129–150 is strongly dependent on electrostatic interactions between CaM and this peptide. The entropy of binding is defined by entropic changes associated with the protein, the ligands, and the solvent (73). The formation of a more rigid complex structure is expected to have a negative contribution to ΔG because of the loss of rotational and translational degrees of freedom. Nevertheless, the burial of hydrophobic areas on complex formation leads to the release of water of hydration to the bulk solvent and has a large positive contribution to ΔG. In the case of the CaM-Cx44129–150 interaction, the positive entropy contribution due to dehydration apparently dwarfs the negative entropy contribution from immobilization of side chains due to complex formation. Indeed, the modeled structure of CaM in complexed with the CaM binding domain in Cx44 showed a number of possible electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions between these two macromolecules.

CaM (pI = 4.2) and the synthetic peptide Cx44129–150 (pI = 10.8) were oppositely charged with a net charge of approximately −15 for CaM (74) and +3 for Cx44129–150, at neutral pH. With opposite charges, it is reasonable to anticipate that electrostatic interactions could be an important determinant in the formation of the CaM-Cx44129–150 peptide complex. As shown in the modeled structure of the CaM-Cx44129–150 complex (Fig. 13, A and B), three positively charged residues (R135, R137, and R144) in Cx44-derived peptide could form salt bridges with negatively charged residues (E127, E14, and E114, respectively) from holo-CaM. Furthermore, the hydrophobic residues I138 and L142 from the peptide are in close proximity with hydrophobic patches of the C-domain of holo-CaM (A128, M144, M145, and L105, F141, respectively), whereas the hydrophobic residue V147 from the peptide is in close contact with the hydrophobic residues in N-domain of holo-CaM (F19, F68, and M71). Based on the calculation of energetics underlying various CaM-target peptide interactions, Brokx et al. (36) have shown that the CaM-target interactions could be driven by different thermodynamic components with large variations in signs and magnitude of ΔH and ΔS (Fig. 10 B). For example, the binding of constitutive nitric oxide synthase and phosphodiesterase to CaM is entropically driven in both cases (ΔS > 0), but they differ in the sign of ΔH, whereas the CaM-CaMKI interaction is mainly driven by favorable enthalpy with unfavorable entropic changes (ΔS < 0). Nevertheless, the free energy change (ΔG) on complex formation falls into a narrow range of −30 to −50 KJ mol−1, which agrees with the well-known enthalpy-entropy compensation phenomenon observed in protein-protein or protein-peptide interactions (73).

Figure 13.

Proposed model of Ca2+-mediated regulation of gap junction permeability. (A and B) Modeled structure of the CaM-Cx44129–150 complex. The model structure is built based on the 3D structure of holo-CaM in complex with the CaM binding region from CaMKII (pdb entry: 1cdm) using MODELER. Residues involved in potential (A) electrostatic interactions and (B) hydrophobic interactions were indicated. Specifically, residues R135, R137, and R144 from the peptide (cyan) are capable of forming salt bridges with residues E127, E14, and E114 (red) from holo-CaM, respectively. In addition, hydrophobic residues from the peptide (V147, V142, and I138, green) is in close proximity with F19/F68/M71, and L105/F141, and A128/M144/M145 from holo-CaM (Met, orange; Phe and Ala, yellow), respectively. (C) Proposed model of regulation of gap junction inhibition mediated by CaM. The subtle changes in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration (at submicromolar range) are initially sensed by the “high-affinity” C-domain of CaM, enabling it to preferably interact with the intracellular loop of Cx proteins. Such interaction enhances the efficiency and sensitivity of intracellular Ca2+ sensing because of increases in both Ca2+-binding affinity and intradomain cooperativity within the C-domain of CaM. The partially saturated, Cx-bound CaM might serve as an intermediate state to prevent the free diffusion of CaM in the cytoplasm. Once the intracellular Ca2+ is further elevated to micromolar range, the half-saturated CaM is then able to quickly respond to the Ca2+ signals and triggers the fully open conformation that is capable of leading to the inhibition of intercellular communication mediated by gap junction. The entity responsible for the Ca2+-mediated inhibition of gap junction still remains to be defined. It could arise from the physical obstruction of the pore by holo-CaM (state i), or be due to the holo-CaM triggered conformational changes in Cx protein itself (state ii). Whether or not all six subunits have to bind calmodulin to exhibit Ca2+-dependent gap junction inhibition remains to be defined.

To transduce changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration into diverse activities and functions, CaM exhibits different specificities and metal binding properties on binding to a wide range of targets. The association between CaM and its receptor targets has been shown to be either Ca2+-dependent or Ca2+-independent. For instance, CaM binding to target proteins such as myosin light chain kinases (75) and Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinases are Ca2+-dependent (76). In contrast, other target proteins such as the ryanodine receptor 1 (77), neuromodulin (or GAP-43) (78), and neurogranin (79) that contain the so-called “IQ” CaM binding motif bind CaM constitutively independent of Ca2+ concentration. In addition, there are several CaM targets (e.g., the small-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels and anthrax edema factor) that are capable of interacting with half-saturated CaM, i.e., when the two sites in the CaM C-domain are occupied by Ca2+ ions (80,81). Our peptide and metal titration data show that the interaction between CaM and the Cx peptides are dependent on ∼μM concentrations of Ca2+ and that the stoichiometry of metal/CaM (4:1) remains unaltered on binding with the Cx peptides. Nevertheless, the binding of the Cx peptides enhanced the Ca2+-binding affinities of the C-domain of CaM 1.7–2.1-fold, but had no significant effect on the Ca2+-binding affinities of the N-domain (Table 4). The total Ca2+ binding energies of the CaM C-domain are accordingly increased by 1.4–3.5 KJ/mol−1, and more importantly, the intradomain cooperative energies are increased by 1.0–1.5 KJ mol−1 (Table 5, Fig. 12). Our kinetic data further demonstrates that the dissociation of Ca2+ from CaM is possibly slowed when CaM is associated with the Cx44129–150 peptide. The dissociation of Ca2+ from CaM typically leads to the loss of CaM-modulated functions (82), and thus slowing this dissociation would ensure that the complex remains intact and that the CaM-gap junction complex maintains its functional form even during frequent oscillations in [Ca2+]i.

Overall, such changes in the Ca2+-binding kinetics, affinities and energies support the following working model of Ca2+-CaM-modulated gap junction inhibition (Fig. 13 C). First, the subtle changes in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration (at submicromolar range) are initially sensed by the “high-affinity” C-domain of CaM, enabling it to preferably interact with the intracellular loop of Cx proteins. Such interaction enhances the efficiency and sensitivity of intracellular Ca2+ sensing because of increases in both Ca2+-binding affinity and intradomain cooperativity within the C-domain of CaM. The partially saturated, Cx-bound CaM might serve as an intermediate state to prevent the free diffusion of CaM in the cytoplasm. Once the intracellular Ca2+ is further elevated to micromolar range, the half-saturated CaM is then able to quickly respond to the Ca2+ signals and triggers the fully open conformation that is capable of leading to the inhibition of intercellular communication mediated by gap junction. However, the “culprit” responsible for the physical obstruction of the gap junction in response to intracellular elevation of Ca2+ levels still remains controversial. A “ball-and-chain” or “particle-receptor” hypothesis involving the pH-dependent intramolecular interaction between the cytoplasmic domain and part of the intracellular loop of Cx43 has been proposed to explain the low pH-induced closure of gap junction (83,84). In this hypothesis, the intracellular loop of Cx43 (119-144) undergoes conformational changes at low pH with a higher degree of α-helicity and functions as the receptor site to accommodate the particle, i.e., the cytoplasmic domain, thereby facilitating the closure of channels. In contrast, an alternate “cork-type” gating model mediated by Ca2+-activated CaM has been proposed by Peracchia et al. (14,15,85). This gating mechanism is driven either by conformational changes in CaM or by structural changes in Cx itself. It could arise from the physical obstruction of the pore by holo-CaM, or is caused by the holo-CaM triggered conformational changes in Cx protein itself (Fig. 13 C). The CaM-driven gating mechanism argues that CO2-induced increase in both [H+] and [Ca2+]i (more closely correlated to the latter factor) would activate CaM and enable the association of CaM with Cx32 to physically obstruct the channel mouth (14,15). The size of each lobe of CaM (∼25Å in diameter) coincides with the channel pore size. Our studies have shown that Ca2+-activated CaM interacts with sequences derived from the cytoplasmic loop of Cx43 and Cx44 with affinities at nanomolar or submicromolar range over the pH range 5.5–8.5. Substantial structural changes were observed in both CaM and the cytoplasmic loop region of Cx43 and Cx44 on complex formation. Thus, although, our data better support the “cork-type” gating model for the inhibition of gap junctions by Ca2+-CaM, the definitive molecular entities responsible for the Ca2+-mediated inhibition of gap junction still remains to be defined and is the subject of our ongoing studies.

Acknowledgments

Yubin Zhou is a fellow of the Molecular Basis of Disease Area of Focus at Georgia State University.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants EY-05684 (C.F.L., J.Y.) and GM62999 (J.Y.).

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Mathias R.T., Rae J.L., Baldo G.J. Physiological properties of the normal lens. Physiol. Rev. 1997;77:21–50. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eiberger J., Degen J., Romualdi A., Deutsch U., Willecke K. Connexin genes in the mouse and human genome. Cell Commun. Adhes. 2001;8:163–165. doi: 10.3109/15419060109080717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eastman S.D., Chen T.H., Falk M.M., Mendelson T.C., Iovine M.K. Phylogenetic analysis of three complete gap junction gene families reveals lineage-specific duplications and highly supported gene classes. Genomics. 2006;87:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krutovskikh V., Yamasaki H. Connexin gene mutations in human genetic diseases. Mutat. Res. 2000;462:197–207. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao Y., Spray D.C. Structural changes in lenses of mice lacking the gap junction protein connexin43. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1998;39:1198–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gong X., Li E., Klier G., Huang Q., Wu Y. Disruption of alpha3 connexin gene leads to proteolysis and cataractogenesis in mice. Cell. 1997;91:833–843. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80471-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xia C.H., Cheng C., Huang Q., Cheung D., Li L. Absence of alpha3 (Cx46) and alpha8 (Cx50) connexins leads to cataracts by affecting lens inner fiber cells. Exp. Eye Res. 2006;83:688–696. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White T.W., Goodenough D.A., Paul D.L. Targeted ablation of connexin50 in mice results in microphthalmia and zonular pulverulent cataracts. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:815–825. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.3.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Churchill G.C., Lurtz M.M., Louis C.F. Ca(2+) regulation of gap junctional coupling in lens epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C972–C981. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.3.C972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lurtz M.M., Louis C.F. Calmodulin and protein kinase C regulate gap junctional coupling in lens epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C1475–C1482. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00361.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang D.I., Louis C.F. Molecular cloning of ovine connexin44 and temporal expression of gap junction proteins in a lens cell culture. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:2658–2664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noma A., Tsuboi N. Dependence of junctional conductance on proton, calcium and magnesium ions in cardiac paired cells of guinea-pig. J. Physiol. 1987;382:193–211. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sotkis A., Wang X.G., Yasumura T., Peracchia L.L., Persechini A. Calmodulin colocalizes with connexins and plays a direct role in gap junction channel gating. Cell Commun. Adhes. 2001;8:277–281. doi: 10.3109/15419060109080737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peracchia C., Sotkis A., Wang X.G., Peracchia L.L., Persechini A. Calmodulin directly gates gap junction channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:26220–26224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peracchia C., Wang X.G., Peracchia L.L. Slow gating of gap junction channels and calmodulin. J. Membr. Biol. 2000;178:55–70. doi: 10.1007/s002320010015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dodd R., Peracchia C., Stolady D., Torok K. Calmodulin association with connexin32-derived peptides suggests trans-domain interaction in chemical gating of gap junction channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:26911–26920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801434200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clapham D.E. Calcium signaling. Cell. 2007;131:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yap K.L., Kim J., Truong K., Sherman M., Yuan T. Calmodulin target database. J. Struct. Funct. Genomics. 2000;1:8–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1011320027914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lurtz M.M., Louis C.F. Intracellular calcium regulation of connexin43. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1806–C1813. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00630.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou Y., Yang W., Lurtz M.M., Ye Y., Huang Y. Identification of the calmodulin binding domain of connexin 43. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:35005–35017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitaku S., Hirokawa T., Tsuji T. Amphiphilicity index of polar amino acids as an aid in the characterization of amino acid preference at membrane-water interfaces. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:608–616. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.4.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krogh A., Larsson B., von Heijne G., Sonnhammer E.L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones D.T. Do transmembrane protein superfolds exist? FEBS Lett. 1998;423:281–285. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tusnady G.E., Simon I. The HMMTOP transmembrane topology prediction server. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:849–850. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marti-Renom M.A., Stuart A.C., Fiser A., Sanchez R., Melo F. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2000;29:291–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meador W.E., Means A.R., Quiocho F.A. Modulation of calmodulin plasticity in molecular recognition on the basis of x-ray structures. Science. 1993;262:1718–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.8259515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallace R.W., Tallant E.A., Cheung W.Y. Assay of calmodulin by Ca2+-dependent phosphodiesterase. Methods Enzymol. 1983;102:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(83)02006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson J.D., Wittenauer L.A. A fluorescent calmodulin that reports the binding of hydrophobic inhibitory ligands. Biochem. J. 1983;211:473–479. doi: 10.1042/bj2110473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scholtz J.M., Qian H., York E.J., Stewart J.M., Baldwin R.L. Parameters of helix-coil transition theory for alanine-based peptides of varying chain lengths in water. Biopolymers. 1991;31:1463–1470. doi: 10.1002/bip.360311304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong L., Johnson W.C., Jr. Environment affects amino acid preference for secondary structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:4462–4465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.VanScyoc W.S., Sorensen B.R., Rusinova E., Laws W.R., Ross J.B. Calcium binding to calmodulin mutants monitored by domain-specific intrinsic phenylalanine and tyrosine fluorescence. Biophys. J. 2002;83:2767–2780. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75286-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pedigo S., Shea M.A. Discontinuous equilibrium titrations of cooperative calcium binding to calmodulin monitored by 1-D 1H-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1995;34:10676–10689. doi: 10.1021/bi00033a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LaPorte D.C., Keller C.H., Olwin B.B., Storm D.R. Preparation of a fluorescent-labeled derivative of calmodulin which retains its affinity for calmodulin binding proteins. Biochemistry. 1981;20:3965–3972. doi: 10.1021/bi00517a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theoharis N.T., Sorensen B.R., Theisen-Toupal J., Shea M.A. The neuronal voltage-dependent sodium channel type II IQ motif lowers the calcium affinity of the C-domain of calmodulin. Biochemistry. 2008;47:112–123. doi: 10.1021/bi7013129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brokx R.D., Lopez M.M., Vogel H.J., Makhatadze G.I. Energetics of target peptide binding by calmodulin reveals different modes of binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:14083–14091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Falk M.M., Lauf U. High resolution, fluorescence deconvolution microscopy and tagging with the autofluorescent tracers CFP, GFP, and YFP to study the structural composition of gap junctions in living cells. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2001;52:251–262. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20010201)52:3<251::AID-JEMT1011>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clapperton J.A., Martin S.R., Smerdon S.J., Gamblin S.J., Bayley P.M. Structure of the complex of calmodulin with the target sequence of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I: studies of the kinase activation mechanism. Biochemistry. 2002;41:14669–14679. doi: 10.1021/bi026660t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenberg O.S., Deindl S., Sung R.J., Nairn A.C., Kuriyan J. Structure of the autoinhibited kinase domain of CaMKII and SAXS analysis of the holoenzyme. Cell. 2005;123:849–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamauchi E., Nakatsu T., Matsubara M., Kato H., Taniguchi H. Crystal structure of a MARCKS peptide containing the calmodulin-binding domain in complex with Ca2+-calmodulin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:226–231. doi: 10.1038/nsb900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]