Abstract

Deletion of integrin-β1 (Itgb1) in the kidney collecting system led to progressive renal dysfunction and polyuria. The defect in the concentrating ability of the kidney was concomitant with decreased medullary collecting duct expression of aquaporin-2 and arginine vasopressin receptor 2, while histological examination revealed hypoplastic renal medullary collecting ducts characterized by increased apoptosis, ectasia and cyst formation. In addition, a range of defects from small kidneys with cysts and dilated tubules to bilateral renal agenesis was observed. This was likely due to altered growth and branching morphogenesis of the ureteric bud (the progenitor tissue of the renal collecting system), despite the apparent ability of the ureteric bud-derived cells to induce differentiation of the metanephric mesenchyme. These data not only support a role for Itgb1 in the development of the renal collecting system but also raise the possibility that Itgb1 links morphogenesis to terminal differentiation and ultimately collecting duct function and/or maintenance.

Keywords: ureteric bud, metanephric mesenchyme, branching morphogenesis, cystic kidney disease, diabetes insipidus, renal failure, polyuria

of the 24 potential heterodimeric integrin receptors which can be assembled from the 18α- and 8β-subunit chains, the laminin-binding integrin receptors α3β1, α6β1, and α6β4 have been demonstrated to play a role in the development of the renal collecting system (38). Of these integrin subunit chains, only integrin-α3 (Itgα3) has been clearly shown to be crucial for in vivo kidney development, in that genetically mutant mice display fewer collecting ducts in the papilla (16). In contrast, genetic deletions of either Itga6 or Itgb4 integrin subunits do not affect kidney development, although double knockout of Itga3 and Itga6 results in a similar kidney phenotype to that seen in the Itga3-deficient animals (8). Together, these findings indicate that the Itgb1 integrin subunit likely plays a key role in the development of the renal collecting system and thus in kidney development. However, conventional knockouts of Itgb1 result in gastrulation defects leading to embryonic lethality at around day 5.5 of gestation, limiting the usefulness of this mutant in the assessment of the role of Itgb1 in collecting system and kidney development (10, 35).

Here, we have specifically deleted Itgb1 from the developing renal collecting system by crossing LoxP-flanked Itgb1 (Itgb1f/f) mice with a transgenic line expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the ureteric bud (UB)-specific HoxB7 promoter (HoxB7-Cre) (29, 37). HoxB7-Cre is expressed in cells of UB lineage from as early as embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5). Such tissue-specific conditional knockouts of Itgb1 utilizing expression of Cre recombinase to excise the gene have been performed in a variety of tissues, including skin, mammary gland, heart, cartilage, brain, intestine, and glomerulus (1, 5, 9, 12–14, 17, 25, 28, 34), and this technique remains the method of choice to perform homologous recombination in a cell type-restricted manner (20, 21). Adult mutants displayed severe polyuria with decreased expression of the vasopressin receptor and collecting duct degeneration. Biochemical and image analyses of renal function in these adults revealed significant renal dysfunction leading to premature death. Conditional deletion of Itgb1 was found to cause a retardation of kidney growth and resulted in a variety of kidney developmental defects ranging from medullary hypogenesis to bilateral agenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Conditional deletion of Itgb1 in the collecting duct.

Collecting duct-specific Itgb1 gene disruption was obtained by breeding a Itgb1f/f line (34) with a transgenic line expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the HoxB7 promoter [Tg(Hoxb7-cre)13Amc, The Jackson Laboratory] (37). The HoxB7Cre and the Cre recombinase expression pattern have been previously characterized in detail (4, 19, 29, 37). Heterozygous Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ littermates were used as controls for the Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ KO in physiological studies.

The care and use of animals described in this investigation conform to the procedures of the laboratory's animal protocol approved by the Animal Subjects Program and the IACUC of UCSD.

Urine and blood/serum measurements.

Twenty-four-hour urine samples were obtained by placing the mice in metabolic cages (Nalgene, Rochester, NY). For water-restriction experiments, 12-h urine samples were obtained. For urine chemistry, spot urine samples were collected. Plasma and urine salt, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and osmolality were determined via standard methods. Both urine and blood chemistry measurements were performed at the UCSD phenotyping core.

Immunohistochemistry.

The kidneys were immersion-fixed for 24 h or perfusion-fixed and postfixed for 1 h using 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4). Ten-micrometer sections were obtained by cryostat sectioning and processed for (immuno)histochemistry using previously characterized antibodies for Itgb1, aquaporin-1 (Aqp1), occludin, and type IV collagen. Antibodies against Ki67 were used for the terminal transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling assay, and FITC-conjugated Dolichos biflorus (DB) agglutinin was used for UB-specific staining.

Imaging.

Planar scintigraphic imaging was performed under ketamine (intraperitoneal) analgesia. Technetium-99m-diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (99mTc-DTPA; 1.1 mCi) was injected as a tracer through the tail vein. Control and knockouts were placed in pairs in a prone position on the surface of a BioSpace planar scintigraphic camera. Images were collected for 50 min following the injection of the tracer. Volumetric computed tomography (CT) scans were performed at 90-μm3 isometric voxel resolution using an eXplore Locus RS rodent MicroCT scanner (GE Healthcare). Images were reconstructed with the manufacturer's proprietary software. Both imaging experiments were conducted at the UCSD Imaging Core Facility.

Laser capture and qPCR.

Whole kidneys were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen 10-μm kidney sections were collected. The kidney medulla was isolated using laser-microdissection with a MMI SL μCut Laser Capture Microdissection microscope (Molecular Machines and Industries, Rockledge, FL). RNA was then extracted from either the medulla or the whole kidney using an Ambion RNA microkit (Austin, TX) and then amplified into cDNA using the Invitrogen SuperScript III system (Carlsbad, CA). Primers for selected genes were designed using Primer 3 and then generated. qPCR was performed using Invitrogen Syber Green/Rox (Carlsbad, CA) with the Applied Biosystems' Fast Real-Time PCR 7500 (Foster City, CA). Cycle thresholds (Ct) values of a gene of interest were normalized to those of Gapdh. Samples were analyzed as three technical replicates and four biological replicates; significant fold-changes were determined using Student's t-test.

RESULTS

Generation of collecting duct-specific Itgb1 deletion.

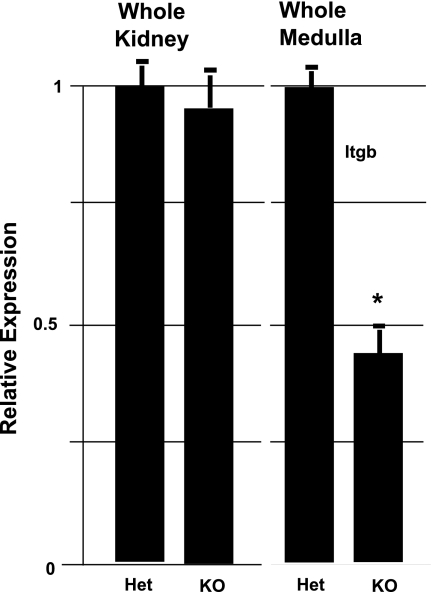

To determine the role of Itgb1 in the renal collecting system, LoxP-flanked Itgb1 mice were crossed with a transgenic line expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the UB-specific HoxB7 promoter (19, 29, 37). Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mutants were then generated through mating with heterozygous Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+. Expected Mendelian frequencies were obtained. Heterozygous Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ littermates were used as controls. qPCR analysis of Itgb1 expression was performed using whole adult kidneys, as well as on microdissected renal medulla. There was little, if any, significant difference in the level of Itgb1 expression in whole kidney preparations of Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice (compared with littermate Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+) (Fig. 1), presumably due to the large amount of surrounding non-UB/collecting duct-derived tissue. However, qPCR analysis of RNA isolated from laser capture, microdissected renal medullary tissue (which contains a greater proportion of tissue that is of collecting duct origin) revealed a substantial loss of Itgb1 expression in conditional knockout mice, compared with heterozygous control mice (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Itgb1 transcript is significantly reduced in the Itgb1-deficient (Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+) renal medulla. A comparison of Itgb1 expression in heterozygous (Het) and knockouts (KO) as determined by RT-quantitative (q) PCR of RNA isolated from whole kidneys and laser capture microdissected renal medulla is shown. *P < 0.05.

Controls had normal-appearing kidneys, while the Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ knockouts displayed a wide range of kidney abnormalities ranging from bilateral agenesis to apparently normal-sized kidneys. Of the 25 mutants examined, 11 displayed gross renal hypoplasia, 1 had unilateral renal agenesis, 2 had bilateral renal agenesis, and the remaining 11 mutants had grossly normal-sized kidneys (Table 1). An additional 20 mutants were allowed to go to term and then weaned; these survived into adulthood (8 wk of age). Thus, of the 45 mutants examined, only 2 displayed complete bilateral renal agenesis (∼5% of the mutants, which did not survive either birth or the initial week; Table 1), while all the others developed into adulthood (8th wk), indicating the presence of at least one functioning kidney (as described below, many of these were found to exhibit a renal phenotype).

Table 1.

Phenotype distribution in β1-integrin-deficient mice

|

E18-P1 |

Adult

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Total | Small kidney (<2/3 normal) | Total | Small (body weight) |

| Itgb1+/+HoxB7Cre+& | ||||

| Itgb1f/f,f/+, +/+ HoxB7Cre− | 101 | 0 | 72 | 1 |

| Itgb1f/+ HoxB7Cre+(Het) | 46 | 0 | 28 | 2 |

| Itgb1f/f HoxB7Cre+ (KO) | 25 | 14 (3agenesis) | 20 | 18 |

| Total | 172 | 14 | 125 | 21 |

E18, embryonic day 18; P1, postpartum day 1; Het, heterozygous; KO, knockout.

Adult Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ animals developed renal insufficiency.

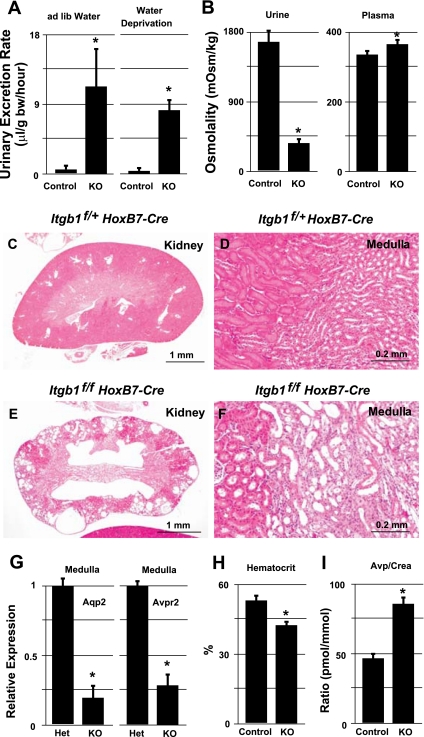

Adult Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ (along with Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+) animals maintained in metabolic cages at 8 wk of age were found to excrete more than 10 times the volume of urine than the Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ mice (when allowed to drink water ad lib) (Fig. 2A, left; P < 0.05). The urine of the knockouts remained relatively isosmotic with blood plasma (Fig. 2B). Water restriction for 12 h did not significantly reduce the urine output in Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+, while the Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ mice produced a smaller volume of urine with water restriction (Figs. 2A, right; P < 0.05). Histological examination of mutant kidneys with polyuria and renal failure revealed a dramatically perturbed architecture of the kidney (Fig. 2, C–F). The cortex was characterized by relatively normal patches of renal cortex, containing clustered glomeruli, separated by larger areas containing multiple cystic structures which are likely to be dilated cortical collecting ducts. Tubular ectasia was also seen in the renal medulla (compare Fig. 2, C and D, vs. E and F) with dilated collecting ducts that were almost three times as wide in the mutant medulla (compare Fig. 2, D vs. F). The cells of the medullary collecting duct express the water channels Aqp2, -3, and -4 and are the target for antidiuretic hormone vasopressin (AVP). The collecting ducts from the mutant medullary region were found to have significantly reduced expression of Aqp2 and vasopressin V2 receptor, Avpr2 (Fig. 2G). Given the physiological function, defects in the medullary collecting ducts could provide an explanation for the observed polyuria phenotype in Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice.

Fig. 2.

A and B: graphs showing effects of Itgb1 KO on renal function. A: effects on urine output in Het Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ (control) and KO Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice under conditions of ad libitum water and water restriction. B: effects on urine and plasma osmolality in Het Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ (control) and KO Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice. C–F: hematoxylin- and eosin-stained cross sections of the kidney (C and E) and cortex/medulla junction (D and F) of 8-wk-old adult kidneys from Het Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ (C and D) and KO Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice (E and F). G: RT-qPCR for the expression of aquaporin 2 (Aqp2) and arginine-vasopressin receptor 2 (Avpr2) in RNA isolated from the renal medullas of Het Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ (control) and KO Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice. H: graph of the hematocrit from adult Het and KO mice. I: graph of the ratio of measured Avp (urinary)/creatinine (plasma) from adult Het and KO mice. *P < 0.05.

To investigate this further, blood and urine chemistries for the mutants and controls was performed (Table 2). Adults were found to have relatively normal plasma level of Na+ and K+ compared with controls. Furthermore, while the pH of the urine in the knockouts was not significantly changed, the plasma urea level was elevated and there was a clear and significant decrease in the blood hematocrit (HCT; 42% in knockouts vs. 52% in control) (Fig. 2H). There was no significant change in the blood creatinine level between mutant and control adults (Table 2); the fact that the urinary AVP-to-creatinine ratio (as a surrogate for plasma AVP levels) was enhanced in the mutants (Fig. 2I) indicates that the primary cause of polyuria is likely due to an inability to respond to AVP within the kidney, a role performed by cells of the collecting duct, derived from the UB. Moreover, the concentrating defect seems to be comparable to that found in Aqp2 and Avpr2 mutants (18, 29, 30, 36). Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ were also noted to have an elevated plasma urea concentration. The fact that these knockouts have an abnormal medulla and exhibit polyuria supports the notion that the medullary defect itself precipitates the development of a urinary concentration defect in Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice. Taken together, the data are consistent with chronic renal disease in the knockout.

Table 2.

Blood and urine chemistry in β1-integrin-deficient mice

| Itgb1f/+ HoxB7Cre+ | Itgb1f/f HoxB7Cre+ | |

|---|---|---|

| Blood | ||

| Glucose (90–192 mg/dl) | 187.2 | 143.3 |

| BUN (18–29 mg/dl) | 26.1 | 47.3 |

| Creatinine (0.2–0.8 mg/dl) | 0.2 | 0.25 |

| Albumin (2.5–4.8 g/dl) | 3.36 | 2.98 |

| Globulin | 1.72 | 1.52 |

| Total protein (3.6–6.6 g/dl) | 5.1 | 4.47 |

| Bilirubin (0.1–0.9 mg/dl) | 0.17 | 0.15 |

| Sodium (126–182 meq/l) | 156 | 158 |

| Calcium (5.9–9.4 mg/dl) | 10.06 | 8.73 |

| Phosphorus (6.1–10.1 mg/dl) | 11.2 | 9.37 |

| SGPT (28–132 U/l) | 81.2 | 51.8 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (62-209 U/l) | 149.5 | 158.5 |

| Amylase (1,691–3,615 U/l) | 963 | 911 |

| Urine | ||

| Albumin, g/dl | 0 | 0 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/l | <5 | <5 |

| ALT, U/l | 83.8 | 78.1 |

| Amylase, U/l | 122.8 | 215.8 |

| Bilirubin, total, mg/dl | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Calcium, mg/dl | <4.0 | <4.0 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 12.13 | 4.78* (P < 0.05) |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 37.5 | 36.3 |

| Total protein, g/dl | <2.0 | <2.0 |

Testing blood (range in parentheses) and urine samples were taken from 6 littermate pairs of heterozygous and homozygous KO mice, at 7–10 wk of age. BUN, blood urea nitrogen; SGPT, serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

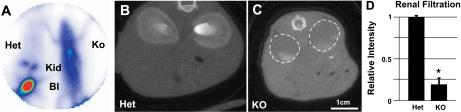

This notion is further supported by BioSpace planar scintigraphic analysis, which revealed a reduction in the ability of the knockouts to eliminate the contrast agent DPTA compared with control animals. Side-by-side comparison of the Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ knockouts and the Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ (heterozygotes) controls revealed clear accumulation and concentration of the contrast agent in the kidneys and bladder of the heterozygotes (Fig. 3A). In contrast, in the Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ (knockouts), DPTA appears to be randomly distributed throughout the body, indicating a reduced capacity of the kidneys in the knockout animals to clear this agent from the blood (Fig. 3A). In addition, companion micro-CT scans were performed between the Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ (knockouts) and Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ (heterozygotes) control with labeled PAH. This examination revealed little uptake of the labeled PAH into the knockout kidneys compared with the kidneys from the control animals (Fig. 3, B and C). Semiquantitative analysis of these micro-CT scan images revealed that renal uptake of the labeled PAH was reduced ∼85% compared with that of normal kidneys (Fig. 3D). Thus the function of the kidneys in these mutants is clearly and profoundly perturbed.

Fig. 3.

A: BioSpace planar scintigraphic image showing filtration of diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (DPTA) in Het Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ and KO Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice. Kid, kidney; bl, bladder. Eight-week-old Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ and Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice were placed on the surface of the camera side by side. Images were collected for 50 min following the injection of 1.1 mCi of technetium-99m (99mTc)-DTPA as a tracer through the tail vein. Images collected after 50 min are shown here. B and C: micro-CT scan images of Het Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ and KO Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice. Abdominal segments at 90-μm resolution were obtained using an eXplore Locus RS rodent MicroCT scanner. D: semiquantitative image analysis of renal filtration after digitizing of the micro-CT images (B and C) using ImageJ (NIH). *P < 0.05.

A number of tubular markers were examined by RT-PCR.

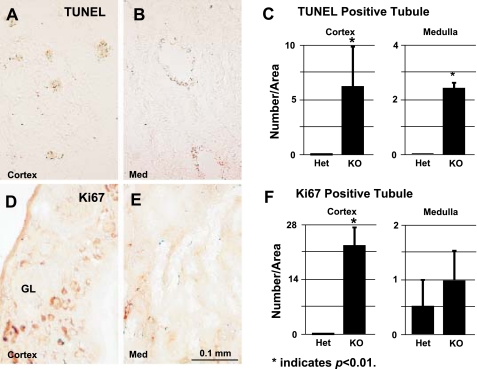

No significant changes were observed in the expression of the glomerular markers Nephrin and Podocin, or the proximal tubular marker Oat3, and thick ascending limb of Henle's loop marker Thp when their expression levels were normalized to that of Gapdh (data not shown). However, a significant increase in terminal transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling-positive cells was observed in the cortex (Fig. 4, A and C) and associated with the dilated tubules in the medulla of mutant kidneys (Fig. 4, B and C). In addition, there was a significant increase in cellular proliferation, as evidenced by cells positive for Ki67 (a cellular marker for proliferation) in the mutant kidney cortex, probably associated with proximal tubular structures (Fig. 4, D and F), but not in the medulla (Fig. 4, E and F).

Fig. 4.

A and B: terminal transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining of the renal cortex (A) and renal medulla (B) of cryostat sections of adult KO Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ kidney. C: quantification of TUNEL staining shown in A and B. D and E: cell proliferation as measured by Ki67 staining of renal cortex (D) and renal medulla (E) of cryostat sections derived from adult KO Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ kidney. F: quantification of Ki67 staining shown in D and E.

A medullary defect and severe polyuria become evident in the mature Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ kidney.

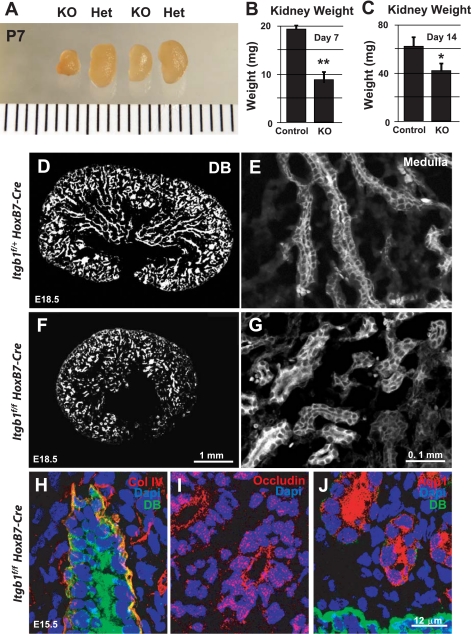

As indicated in Table 1, the majority of mutants were born with gross renal hypoplasia. The kidneys failed to attain the size of the wild-type or heterozygous kidneys during postnatal development and were still significantly smaller at both 1 and 2 wk of age (Fig. 5, A–C). On closer examination, late-stage developing Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ kidneys were small, primarily due to the reduced size of the inner medulla (Fig. 5, D and F), revealed by conjugated DB staining specific for collecting duct/UB-derived structures, (which is normally densely populated by cells of the collecting ducts) as well as the expression of some extracellular matrix- and tissue-specific markers. At a higher magnification, DB-positive cells were found lining the medullary tubular structures of the remaining collecting ducts (Fig. 5, E and G). In addition, the basement membrane of the UB-derived tubules in the Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ kidney were found to express an epithelial marker, collagen IV (Fig. 5H), a ligand of β1-integrin receptors, in a pattern similar to that seen in Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ control kidney (data not shown). Moreover, the localization of occludin along the apical aspect of the tubular cells in Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice indicates that these cells retain their epithelial nature and possess tight junctions (Fig. 5I). These findings suggested that the mutant UB-derived cells were competent to maintain polarity through the normal establishment of a basolateral matrix and an apical tight junction. Similarly, epithelial cells of the mesenchyme, which form the future nephron, did not express DB and were found to express a proximal tubular marker, Aqp1, at the apical surface (Fig. 5J); thus polarized proximal tubular cells were induced in the Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice.

Fig. 5.

Small Itgb1 deficient (Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+) kidney. A: photograph of isolated kidneys from Het Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ mice and KO Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice at day 7 postpartum; bar = 1 mm. B: graph of the measured kidney weights from Het and KO mice at day 7 postpartum. C: graph of the measured kidney weights from Het and KO mice at day 14 postpartum. D–G: fluorescent photomicrographs of cryostat sections of kidneys isolated at embryonic day 18.5 (E18.5) of gestation from Het Itgb1f/+HoxB7Cre+ (D and E) and KO Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice (F and G) stained with rhodamine-conjugated Dolichos biflorus lectin (DB). D and F: low-magnification examination of entire kidney. E and G: higher-magnification examination of the renal medulla. H–J: fluorescent photomicrographs of cryostat sections of e15.5 KO Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ kidneys stained for the presence of collagen IV (H; red), occludin (I; red) and aquaporin 1 (Aqp1; J; red). The sections were also counterstained with the nuclear stain, DAPI (blue), and the ureteric bud (UB)-specific stain fluorescein-conjugated DB (green). **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, KO vs. control.

DISCUSSION

We have conditionally deleted the integrin receptor β1 in epithelial cells comprising the UB and its derivatives, and thus specifically from the renal collecting system. The following were observed: 1) progressive renal impairment; 2) inability to concentrate urine; 3) decreased expression of Avpr2 and Aqp2; and 4) compromised formation and/or maintenance of the medullary collecting ducts. The results demonstrate the importance of Itgb1 in the growth and development of the renal collecting system, while supporting a role for it in the differentiation and/or maintenance of the medullary collecting ducts.

As previously described, defects in the medullary region of the kidney, particularly in the medullary collecting ducts, are observed in Itga3 knockouts. Since the only identified partner for Itga3 in the UB (the progenitor tissue of the renal collecting system) is the β1-integrin subunit, the fact that the Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice exhibit a phenotype somewhat similar to that seen in Itga3 knockouts supports a key role for integrin α3β1 in the development of the renal collecting system (a role which cannot be completely compensated for by other integrin receptors found in this tissue). In adult kidneys, tubular epithelial cells in the medulla exhibited a significant increase in apoptosis. Cells in the medulla, especially the deeper medulla, are exposed to more stressful physiologic conditions (i.e., higher osmolarity) than in other parts of the kidney (15). Therefore, it is possible that the lack of Itgb1 results in a lower tolerance to stress in cells in this region, manifesting as increased apoptosis. Moreover, there was decreased expression of Aqp2 and Avpr2 in the medullary region of the adult mutant kidney. Although increased apoptosis in this region could cause a reduction in the collecting duct cells expressing these markers in the medulla, an alternative explanation is that Itgb1-mediated signaling may be required for proper development/differentiation of the developing UB cells and medullary collecting duct cells, either during development or as the apoptotic cells are replaced in the adult kidney.

This notion is consistent with alterations in cell proliferation seen in other conditional deletions of Itgb1. For example, conditional deletion of Itgb1 in the epidermal layer of the skin led to an ∼70% decrease in keratinocyte proliferation (5, 27). Specific deletion of Itgb1 from chondrocytes or the mammary gland resulted in decreased proliferation both in vivo and in vitro (1, 17, 23). In these cases, cell cycle progression of Itgb1-deficient cells was slower than that observed in wild-type epithelial cells, suggesting that deletion of Itgb1 from the UB and UB-derived structures might have a similar effect in the kidney, both during development and in the adult. Thus the appearance of hypoplastic kidneys could be the result of slower growth and branching of the UB during kidney organogenesis. Cyst formation and tubular ectasia could be due to defective collecting duct morphogenesis or obstruction. It is noteworthy that UB, IMCD, and other renal epithelial cells, as well as the isolated UB itself, are very sensitive to extracellular matrix composition when (2, 6, 26, 31–33, 38) grown in three-dimensional cultures. In fact, many of the receptors for these matrix components include β1-integrin as a subunit.

Many mutants developed renal impairment by 8 wk of age with lower HCT. Although it remains to be definitively determined, the lower HCT in the mutant mice is likely due to reduced Epo production in the mutant kidneys. Recently, a collecting duct-specific deletion of Aqp2 was reported (29). This animal exhibits nephrogenic diabetes insipidus to a degree comparable to that reported here. In these Aqp2 mice, however, neither the renal impairment nor the medullary hypoplasia (fallout) that is seen in the Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice was observed. Thus it is unlikely that the observed nephrogenic diabetes insipidus phenotype can fully explain the cause of renal impairment in the Itgb1f/fHoxB7Cre+ mice. Mutants with significantly diminished nephron number are also not reported to develop this degree of progressive renal dysplasia or any defects in water handling (3, 7, 22, 24). It is possible that the increased apoptosis in the medullary collecting duct contributes to renal impairment, although this remains to be determined.

We also observed decreased expression of genes that play key roles in water handling, Aqp2 and Avpr2. During normal development, there are significant increases found in expression of both genes, Aqp2 and Avr2, around the time of birth, reaching adult levels of expression by the time of weaning. Thus it is also possible that Itgb1 plays a role in the differentiation of the collecting duct cells, and in its reduction/absence, medullary collecting duct cells have perturbed function. This result of epithelial cell differentiation occurring in the mutant mice is similar to that which occurs following conditional deletion of Itgb1 from intestinal epithelium, where a defect in epithelial differentiation was observed (13). Furthermore, conditional deletion in mammary epithelium also led to abnormal differentiation such that these mice do not produce milk in response to prolactin (23). Both of these cases, along with our own data, point toward an essential role of Itgb1 in establishing and/or maintaining differentiation of polarized epithelial cells, such as those comprising the renal collecting ducts. In collecting duct cells, Itgb1 signaling may play an important role in regulating water channel and vasopressin receptor expression. If vasopressin itself is necessary for collecting system morphogenesis or maintenance, this could lead to a vicious cycle, resulting in progressive renal dysfunction. This is consistent with the data that the severe water handling defect seems to precede renal impairment. The remaining function may be attributable to incomplete penetration of the mutation.

Finally, we found increased medullary apoptosis in mature knockout kidneys. This is consistent with the data that the severe water handling defect seems to precede renal impairment. This is not generally reported in Itgb1 conditional knockouts. In Itgb1 deletion in Schwann cells (11) or mammary epithelial cells, increased apoptosis is not observed although chondrocytes lacking Itgb1 expression show increased apoptosis. In our study, increased apoptosis was observed only in adult kidney. It may be that Itgb1 is not critical for survival of certain cells in ordinary circumstances but may be required for survival in stressful environments such as the cartilage (low blood flow) or kidney medulla (high osmolarity). Furthermore, as discussed, if vasopressin functions in collecting system morphogenesis and /or maintenance, the decrease in expression of its receptor in the knockout may further compromise cell survival, especially under stress.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants RO1-DK-065831 and RO1-DK-057286 (S. K. Nigam), NIH Grant HL-088390 and a Veterans Administration Merit Award (R. S. Ross); a Normon S. Coplon Extramural Grant from Satellite Healthcare, (K. T. Bush); a Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association (H. Sakurai); and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (TR 1535/3-1) and a National Kidney Foundation Fellowship (T. Rieg).

Acknowledgments

We thank Shamara Closson and Jacqueline A. Corbeil for excellent technical support, Dr. M. H. Ginsberg for scientific input, and Dr. M. M. Shah for reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aszodi A, Hunziker EB, Brakebusch C, Fassler R. Beta1 integrins regulate chondrocyte rotation, G1 progression, and cytokinesis. Genes Dev 17: 2465–2479, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barros EJ, Santos OF, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Nigam SK. Differential tubulogenic and branching morphogenetic activities of growth factors: implications for epithelial tissue development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 4412–4416, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates CM Role of fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling in kidney development. Pediatr Nephrol 22: 343–349, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batourina E, Tsai S, Lambert S, Sprenkle P, Viana R, Dutta S, Hensle T, Wang F, Niederreither K, McMahon AP, Carroll TJ, Mendelsohn CL. Apoptosis induced by vitamin A signaling is crucial for connecting the ureters to the bladder. Nat Genet 37: 1082–1089, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brakebusch C, Grose R, Quondamatteo F, Ramirez A, Jorcano JL, Pirro A, Svensson M, Herken R, Sasaki T, Timpl R, Werner S, Fassler R. Skin and hair follicle integrity is crucially dependent on beta 1 integrin expression on keratinocytes. EMBO J 19: 3990–4003, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cantley LG, Barros EJ, Gandhi M, Rauchman M, Nigam SK. Regulation of mitogenesis, motogenesis, and tubulogenesis by hepatocyte growth factor in renal collecting duct cells. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 267: F271–F280, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cullen-McEwen LA, Kett MM, Dowling J, Anderson WP, Bertram JF. Nephron number, renal function, and arterial pressure in aged GDNF heterozygous mice. Hypertension 41: 335–340, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Arcangelis A, Mark M, Kreidberg J, Sorokin L, Georges-Labouesse E. Synergistic activities of alpha3 and alpha6 integrins are required during apical ectodermal ridge formation and organogenesis in the mouse. Development 126: 3957–3968, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faraldo MM, Deugnier MA, Tlouzeau S, Thiery JP, Glukhova MA. Perturbation of beta1-integrin function in involuting mammary gland results in premature dedifferentiation of secretory epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell 13: 3521–3531, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fassler R, Meyer M. Consequences of lack of beta 1 integrin gene expression in mice. Genes Dev 9: 1896–1908, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feltri ML, Graus Porta D, Previtali SC, Nodari A, Migliavacca B, Cassetti A, Littlewood-Evans A, Reichardt LF, Messing A, Quattrini A, Mueller U, Wrabetz L. Conditional disruption of beta 1 integrin in Schwann cells impedes interactions with axons. J Cell Biol 156: 199–209, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Z, Shimazu K, Woo NH, Zang K, Muller U, Lu B, Reichardt LF. Distinct roles of the beta 1-class integrins at the developing and the mature hippocampal excitatory synapse. J Neurosci 26: 11208–11219, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones RG, Li X, Gray PD, Kuang J, Clayton F, Samowitz WS, Madison BB, Gumucio DL, Kuwada SK. Conditional deletion of beta1 integrins in the intestinal epithelium causes a loss of Hedgehog expression, intestinal hyperplasia, and early postnatal lethality. J Cell Biol 175: 505–514, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanasaki K, Kanda Y, Palmsten K, Tanjore H, Bong Lee S, Lebleu VS, Gattone VH Jr, Kalluri R. Integrin beta1-mediated matrix assembly and signaling are critical for the normal development and function of the kidney glomerulus. Dev Biol 313: 584–593, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knepper MA, Gamba G. Urine concentration and dilution. In: Brenner and Rector's The Kidney (7th ed.), edited by Brenner BM. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2004, p. 599–636.

- 16.Kreidberg JA, Donovan MJ, Goldstein SL, Rennke H, Shepherd K, Jones RC, Jaenisch R. Alpha 3 beta 1 integrin has a crucial role in kidney and lung organogenesis. Development 122: 3537–3547, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li N, Zhang Y, Naylor MJ, Schatzmann F, Maurer F, Wintermantel T, Schuetz G, Mueller U, Streuli CH, Hynes NE. Beta1 integrins regulate mammary gland proliferation and maintain the integrity of mammary alveoli. EMBO J 24: 1942–1953, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lloyd DJ, Hall FW, Tarantino LM, Gekakis N. Diabetes insipidus in mice with a mutation in aquaporin-2. PLoS Genet 1: e20, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marose TD, Merkel CE, McMahon AP, Carroll TJ. Beta-catenin is necessary to keep cells of ureteric bud/Wolffian duct epithelium in a precursor state. Dev Biol 314: 112–126, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morozov A, Kellendonk C, Simpson E, Tronche F. Using conditional mutagenesis to study the brain. Biol Psychiatry 54: 1125–1133, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagy A, Mar L. Creation and use of a Cre recombinase transgenic database. Methods Mol Biol 158: 95–106, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Narlis M, Grote D, Gaitan Y, Boualia SK, Bouchard M. Pax2 and Pax8 Regulate branching morphogenesis and nephron differentiation in the developing kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1121–1129, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naylor MJ, Li N, Cheung J, Lowe ET, Lambert E, Marlow R, Wang P, Schatzmann F, Wintermantel T, Schuetz G, Clarke AR, Mueller U, Hynes NE, Streuli CH. Ablation of beta1 integrin in mammary epithelium reveals a key role for integrin in glandular morphogenesis and differentiation. J Cell Biol 171: 717–728, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pentz ES, Moyano MA, Thornhill BA, Sequeira Lopez ML, Gomez RA. Ablation of renin-expressing juxtaglomerular cells results in a distinct kidney phenotype. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286: R474–R483, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pietri T, Eder O, Breau MA, Topilko P, Blanche M, Brakebusch C, Fassler R, Thiery JP, Dufour S. Conditional beta1-integrin gene deletion in neural crest cells causes severe developmental alterations of the peripheral nervous system. Development 131: 3871–3883, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiao J, Sakurai H, Nigam SK. Branching morphogenesis independent of mesenchymal-epithelial contact in the developing kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 7330–7335, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raghavan S, Bauer C, Mundschau G, Li Q, Fuchs E. Conditional ablation of beta1 integrin in skin. Severe defects in epidermal proliferation, basement membrane formation, and hair follicle invagination. J Cell Biol 150: 1149–1160, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohwedel J, Guan K, Zuschratter W, Jin S, Ahnert-Hilger G, Furst D, Fassler R, Wobus AM. Loss of beta1 integrin function results in a retardation of myogenic, but an acceleration of neuronal, differentiation of embryonic stem cells in vitro. Dev Biol 201: 167–184, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rojek A, Fuchtbauer EM, Kwon TH, Frokiaer J, Nielsen S. Severe urinary concentrating defect in renal collecting duct-selective AQP2 conditional-knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 6037–6042, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenthal W, Seibold A, Antaramian A, Lonergan M, Arthus MF, Hendy GN, Birnbaumer M, Bichet DG. Molecular identification of the gene responsible for congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Nature 359: 233–235, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosines E, Schmidt HJ, Nigam SK. The effect of hyaluronic acid size and concentration on branching morphogenesis and tubule differentiation in developing kidney culture systems: potential applications to engineering of renal tissues. Biomaterials 28: 4806–4817, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakurai H, Barros EJ, Tsukamoto T, Barasch J, Nigam SK. An in vitro tubulogenesis system using cell lines derived from the embryonic kidney shows dependence on multiple soluble growth factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 6279–6284, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santos OF, Nigam SK. HGF-induced tubulogenesis and branching of epithelial cells is modulated by extracellular matrix and TGF-beta. Dev Biol 160: 293–302, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shai SY, Harpf AE, Babbitt CJ, Jordan MC, Fishbein MC, Chen J, Omura M, Leil TA, Becker KD, Jiang M, Smith DJ, Cherry SR, Loftus JC, Ross RS. Cardiac myocyte-specific excision of the beta1 integrin gene results in myocardial fibrosis and cardiac failure. Circ Res 90: 458–464, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stephens LE, Sutherland AE, Klimanskaya IV, Andrieux A, Meneses J, Pedersen RA, Damsky CH. Deletion of beta 1 integrins in mice results in inner cell mass failure and peri-implantation lethality. Genes Dev 9: 1883–1895, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang B, Gillespie A, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Verkman AS. Neonatal mortality in an aquaporin-2 knock-in mouse model of recessive nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Biol Chem 276: 2775–2779, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu J, Carroll TJ, McMahon AP. Sonic hedgehog regulates proliferation and differentiation of mesenchymal cells in the mouse metanephric kidney. Development 129: 5301–5312, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zent R, Bush KT, Pohl ML, Quaranta V, Koshikawa N, Wang Z, Kreidberg JA, Sakurai H, Stuart RO, Nigam SK. Involvement of laminin binding integrins and laminin-5 in branching morphogenesis of the ureteric bud during kidney development. Dev Biol 238: 289–302, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]