Abstract

GABA release by dopaminergic amacrine (DA) cells of the mouse retina was detected by measuring Cl− currents generated by isolated perikarya in response to their own neurotransmitter. The possibility that the Cl− currents were caused by GABA release from synaptic endings that had survived the dissociation of the retina was ruled out by examining confocal Z series of the surface of dissociated tyrosine hydroxylase-positive perikarya after staining with antibodies to preand postsynaptic markers. GABA release was caused by exocytosis because 1) the current events were transient on the millisecond time scale and thus resembled miniature synaptic currents; 2) they were abolished by treatment with a blocker of the vesicular proton pump, bafilomycin A1; and 3) their frequency was controlled by the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Because DA cell perikarya do not contain presynaptic active zones, release was by necessity extrasynaptic. A range of depolarizing stimuli caused GABA exocytosis, showing that extrasynaptic release of GABA is controlled by DA cell electrical activity. With all modalities of stimulation, including long-lasting square pulses, segments of pacemaker activity delivered by the action-potential-clamp method and high-frequency trains of ramps, discharge of GABAergic currents exhibited considerable variability in latency and duration, suggesting that coupling between Ca2+ influx and transmitter exocytosis is extremely loose in comparison with the synapse. Paracrine signaling based on extrasynaptic release of GABA by DA cells and other GABAergic amacrines may participate in controlling the excitability of the neuronal processes that interact synaptically in the inner plexiform layer.

INTRODUCTION

In the retina, dopamine sets the gain of neural networks for cone-mediated vision. It is synthesized by type 1 catecholaminergic (dopaminergic, interplexiform) amacrine cells that, on illumination, release this transmitter over their entire surface. Dopamine diffuses throughout the retina and acts by volume transmission on most types of retinal neurons (reviewed by Witkovsky 2004). In addition to this paracrine function, dopaminergic amacrine (DA) cells establish a massive synaptic output onto the cell body of AII amacrine cells (Contini and Raviola 2003; Strettoi et al. 1992), a neuron that is inserted in series along the rod pathway and distributes rod signals to the cone pathway by contacting on- and off-cone bipolars (Supplemental Fig. S1). Immunocytochemical evidence suggests that these synapses are GABAergic: in fact, DA cells contain both GABA and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) (Kosaka et al. 1987; Wässle and Chun 1988; Wulle and Wagner 1990), the rate-limiting enzyme for GABA biosynthesis. Second, a cluster of ionotropic GABAA receptors is contained within the postsynaptic membrane (Contini and Raviola 2003). Third, dopamine receptors are absent on the cell body of AII amacrine cells (Derouiche and Asan 1999; Veruki and Wässle 1996). It seems therefore likely that DA cells release GABA in addition to dopamine.

In the CNS, co-transmission of glutamate and dopamine is a well-established fact in subpopulations of midbrain dopaminergic neurons that convey a fast excitatory signal to their postsynaptic targets (Chuhma et al. 2004; Dal Bo et al. 2004; Fremeau et al. 2002; Joyce and Rayport 2000; Lavin et al. 2005; Sulzer et al. 1998). There is also immunocytochemical evidence that GABA may be a co-transmitter of central dopaminergic neurons, because GABA or GAD is present in a subpopulation of cells of the substantia nigra (Campbell et al. 1991; González-Hernández et al. 2001), dopaminergic periglomerular cells of the olfactory bulb (Kosaka et al. 1987), and dopaminergic cells of the arcuate nucleus in the hypothalamus (Kosaka et al. 1987). Recently, in olfactory bulb slices, GABAergic currents were recorded from dopaminergic periglomerular cells when they were depolarized (Maher and Westbrook 2008).

We hereby show that DA cell perikarya, isolated by dissociation of the retina of mice whose catecholaminergic neurons are labeled by human placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) (Gustincich et al. 1997), release GABA by exocytosis in absence of presynaptic active zones.

METHODS

Dissociation of the retina and identification of solitary DA cells

The procedure for dissociation of the retina and short-term culture of the resulting cell suspension were described in detail previously (Feigenspan et al. 1998). Briefly, retinas obtained from 1- to 3-mo-old mice, homozygous for PLAP cDNA, were incubated with papain (5–10 U; Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) and subsequently triturated by squeezing them through the bore of fire-polished Pasteur pipettes. The diameter of the bore was progressively narrowed until the resulting cell suspension largely consisted of cell bodies devoid of processes. The cell suspension was centrifuged and resuspended in MEM containing 1:100 monoclonal antibody to PLAP (E6; de Waele et al. 1982) directly conjugated to the fluorescent dye Cy3 (E6-Cy3). GABA (20 μM) was usually added to the antibody-containing MEM to suppress the spontaneous firing of DA cells during sedimentation (Gustincich et al. 1997). This pretreatment significantly improved the rate of observation of GABA release induced by Ca2+ infusion from 44% (7 of 16 cells in untreated group) to 84% (43 of 51 cells in treated group; P < 0.005, Fisher exact test). Probably, the GABA pretreatment minimized either 1) the depletion of GABA-containing organelles or 2) the consumption of cytosolic high-energy phosphate compounds that are essential for organelle priming and exocytosis. It is unlikely that pretreatment with micromolar concentrations of GABA would load the secretory organelles with exogenous transmitter, because 1) the treatment did not increase the mean amplitude of the GABAergic events (data not shown) and 2) loading requires transmitter concentrations three order of magnitude larger than that used in our experiments (70 mM) (Kim et al. 2000). The suspension of retinal cells was pipetted onto concanavalin A–coated glass coverslips glued to the bottom of a petri dish and allowed to settle for 25 min in a CO2 incubator at 35∼36°C. This was followed by 45 min at room temperature (total 70 min). Subsequently, the supernatant was decanted, and the coverslips were washed three times with plain MEM and stored in this medium at room temperature for the remainder of the experiments (5–6 h). The petri dishes were mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon Diaphot 300, MVI, Avon, MA), and the DA cells, stained by E6-Cy3, were identified by scanning the coverslip in epifluorescence. Once the DA cells were identified, the remaining procedures were carried out in visible light with DIC optics.

Electrophysiology

Patch pipettes with tip resistance of 3–5 MΩ for whole cell recording were constructed from borosilicate glass. Electrodes were connected to an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) controlled by pCLAMP 8.0 analysis software (Axon Instruments), and current or voltage output was viewed directly on the screen of a computer attached to the amplifier via a DigiData 1200 Interface (Axon Instruments). The digitized data were stored on a PC and analyzed with Origin 6.1J (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Frequency of the low-pass Bessel filter in the amplifier was set at 2 or 5 kHz. Sampling frequency was 5 or 10 kHz. Bath temperature was routinely kept at 30–31°C with a heater controller (TC-344B, Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). An array of fine inlet tubes for perfusion was positioned at a distance of 400 μm from the recorded cell. Extracellular solutions were superfused at a rate of 0.3 ml/min. The inlet solution was changed by shifting the tube array mounted on a rapid solution changer (RSC-200, Bio-Logic SAS, Claix, France) that was not heated; therefore the actual temperature at the cell may have been a few degrees less than 30–31°C. In fact, temperature in the vicinity of the tip of the inlet tube, measured by a thermistor with 0.9 mm diam, was 28–29°C.

Membrane currents of DA cells were recorded by using either the cell-attached or the whole cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique as previously described (Feigenspan et al. 1998). The standard extracellular solution contained (in mM) 137 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4). The pipette solution used for Ca2+ infusion experiments contained (in mM) 100 CsCl, 10 TEA-Cl, 10 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 14 phosphocreatine, 2–3 ATP-Mg, 0.3 GTP-Na, and 1, 2, or 3 CaCl2 for free Ca2+ concentrations of 38, 100, and 358 nM, respectively (pH was adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH). Free Ca2+ concentration was computed using the MaxChelator program (Bers et al. 1994; http://www.stanford.edu/∼cpatton/maxc.html). The pipette solution used to record events triggered by a sustained depolarization contained (in mM) 111–115 cesium methanesulfonate (CsMeSO3), 0 or 10 NaCl, 10 TEA-Cl, 10 HEPES, 0.02 or 0.1 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, 14 phosphocreatine, 2–3.5 ATP-Mg, and 0.3 GTP-Na (pH 7.2). The pipette solution used to record the events that followed pulse depolarization contained (in mM) 105–115 CsCl, 0 or 10 NaCl, 10 TEA-Cl, 10 HEPES, 0.02–0.1 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, 14 phosphocreatine, 3 ATP-Mg, and 0.3 GTP-Na (pH 7.2). The pipette solution used to record AP waveforms in the current-clamp mode contained (in mM) 120 K-gluconate, 10 HEPES, 0.5 EGTA, 4 MgCl2, 14 phosphocreatine, 3 ATP-Mg, and 0.3 GTP-Na (pH 7.2). Solutions containing ATP and GTP were used within 2–7 days after addition of triphosphates. The liquid junction potential (Ljp) of low-Cl pipette solutions (approximately –10 mV, measured by using 3 M KCl agar bridge) was corrected.

Series resistance was maintained at <20 MΩ and usually compensated by 40∼70%. Membrane capacitive currents were minimized. In the recording of GABA release by Ca2+ infusion, the resistance was not compensated, and the capacitive current was not cancelled, to monitor actual values of series resistance.

A 500 μM stock solution of bafilomycin A1 was made in DMSO. After sedimentation in normal MEM, the dissociated cells were incubated in MEM containing 500 nM bafilomycin A1 for 2 h at room temperature. Then, MEM was replaced by standard extracellular solution. Recordings were carried out within 1 h after washout of bafilomycin A1. Experiments on control groups (incubated in 0.1% DMSO) and test groups were interleaved in the same day.

Most chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), except for SNX-482, ω-agatoxin, ω-conotoxin (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel), and bafilomycin A1 (Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO).

GABAergic currents induced by Ca2+ infusion, action potential waveform depolarization, and brief-ramp-pulse depolarization were detected by using the software MiniAnalysis Program (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA), in which the time window for peak detection was set at 10–20 ms. Overlapping events separated by intervals shorter than the time window could not be distinguished, but inspection by eye showed that their frequency was negligible. High-frequency GABAergic currents during depolarization (Figs. 6, A and D) were detected by eye. In both cases, the threshold was defined as twice the value of the SD of baseline noise.

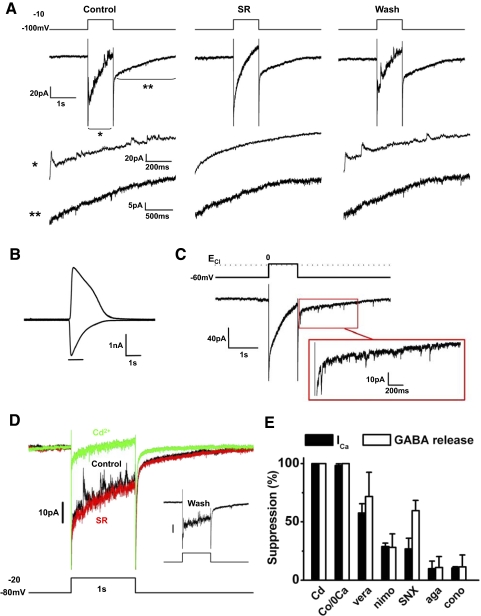

FIG. 6.

Sustained depolarization triggered GABA release by activating Ca2+ current. A: DA cell was depolarized from –100 to –10 mV for 1 s (CsMeSO3-based pipette solution containing 0.02 mM EGTA; ECl about −60 mV). Fast outward current events were riding on the slowly declining inward current. The fast events continued as inward currents after cessation of the depolarization, but they were very small because of the low Cl− concentration in the pipette. Segments of the traces are magnified below (asterisks). SR95531 (20 μM) reversibly blocked the transient currents. Incompletely cancelled capacitive current and Na+ current at the onset of depolarization are truncated. B: in the same cell as in A, application of 1 mM exogenous GABA for 1 s activated an inward current at –100 mV and an outward current at −10 mV. C: DA cell was depolarized from –60 to 0 mV for 1 s (CsCl-based pipette solution containing 0.02 mM EGTA; ECl ∼ 0 mV). With equal concentration of Cl− on either side of the membrane, the fast outward current events were absent during the depolarization, but the fast inward current events became much more prominent after the repolarization. A segment of the current trace after the depolarization is magnified in the box. Thus a sustained depolarization causes a long-lasting discharge of GABAergic currents. D: DA cell was depolarized from –80 to –20 mV for 1 s (CsMeSO3-based pipette solution containing 0.02 mM EGTA; ECl about –60 mV). Traces from a sequence of experiments carried out in the same cell are shown in different colors. Black: in control conditions, transient events were superimposed on the slow inward current. Red: SR95531 (20 μM) blocked the transient events. Green: after SR95531 washout, Cd2+ (100 μM) blocked both the transient events and the slow inward current. Inset: after Cd2+ washout, both transient events and slow inward current were recovered. The slow current that follows the depolarization was blocked by Cd2+ but not by SR. It was probably caused by Na+-Ca2+ exchanger (Gleason et al. 1995). Again, because of the low intracellular Cl−, the events after repolarization were very small. Incompletely cancelled capacitive current and Na+ current at the onset of the depolarization are truncated. E: effects of Ca2+ channel blockers on Ca2+ current (black) and events of GABA release (white) activated by depolarization to –20 mV (Cd, cadmium; Co, cobalt substitution for Ca2+; vera, verapamil; nimo, nimodipine; SNX, SNX-482; aga, ω-agatoxin; cono, ω-conotoxin). Multiple types of Ca2+ channels contributed to the activation of the Ca2+ current elicited by the depolarization. Both L- and R-type channels seem to participate in the release of GABA.

Statistical values are given as mean ± SD; confidence limits were determined by Student's t-test.

Immunocytochemistry

To identify GABAergic endings synapsing with the surface of DA cells in the intact retina, adult C57BL/6J mice were given a lethal dose of pentobarbital sodium and perfused through the heart with 2% formaldehyde in 0.15 M Sørenson phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Retinas were separated from the remaining ocular tunics, fixed for an additional hour, rinsed in PBS (pH 7.4), cryoprotected in 20% sucrose, and frozen in the liquid phase of partially solidified monochlorodifluoromethane. Radial sections 10 μm in thickness, obtained in a cryostat, were preincubated in 2% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich), 10% normal goat serum (Invitrogen Gibco, Carlsbad, CA), and 2% fish gelatin (Ted Pella, Redding, CA) in PBS and treated with mixtures of the following primary antibodies, diluted in 2% BSA in PBS: tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, 1:500, sheep polyclonal, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), synapsin 1 (1:500, mouse monoclonal, Synaptic Systems, Goettingen, Germany), synapsin 1,2 (1:500, rabbit polyclonal, Synaptic Systems), vesicular GABA transporter (1:1,000, rabbit polyclonal, a gift from R. H. Edwards, University of California, San Francisco), and gephyrin (1:500, mouse monoclonal, clone mAb7a, Synaptic Systems). Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-sheep, Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse, and Alexa Fluor 680 donkey anti-rabbit (1:500, Invitrogen Molecular Probes). To examine whether GABAergic endings synapsing with the surface of DA cells had survived the dissociation procedure, we fixed isolated DA cells after sedimentation on a coverslip with 0.5% formaldehyde in MEM for 15 min. Solutions and antibodies were the same as specified above for tissue sections, except for the addition of 0.01% Triton X100. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen Molecular Probes). To confirm the presence of GABAA receptors at the cell surface, coverslips with the sedimented, living cells were incubated in 1:100 rabbit polyclonal antibody to the γ2 subunit of the GABAA receptor (a gift from W. Sieghart, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria) in MEM at room temperature for 5 min, because the extracellular epitope of this antibody is denatured by fixation. Coverslips were subsequently processed as above. The primary antibody was a mouse monoclonal to TH (1:500, ImmunoStar, Hudson, WI), followed by a mixture of two secondary antibodies (1:500 Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse and 1:500 Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit, both from Invitrogen Molecular Probes). Fluorescence was detected in a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal imaging system (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY), equipped with three visible wavelength lasers, META spectral emission detectors, and a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope. For single images of retinal sections and Z series of isolated cells we used a ×60 EC Plan-Neofluar objective 1.4 NA. After adopting the minimal thickness of the optical section that was compatible with adequate emission, images were obtained sequentially from three channels by averaging eight scans (1,024 × 1,024 pixels) and stored as TIFF files. Contrast was processed by Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

Mathematical model of the GABAergic currents

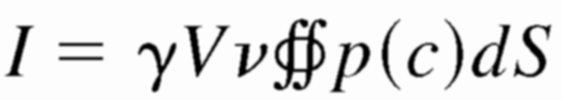

To determine the factors responsible for the rapid rise time and amplitude of the observed GABAergic events in absence of a synapse, we adapted a mathematical model that Braun et al. (2004) used to estimate the GABA vesicular contents in pancreatic β cells.

The elementary current ΔI through a membrane unit surface ΔS at an arbitrary time point after exocytosis depends on the local concentration of GABA, the density of the GABAA receptor Cl− channels, the single channel conductance, and the receptor binding affinity. Therefore it can be expressed mathematically in the following form

|

(1) |

where γ is the single channel conductance, V is the driving force of Cl−, ν is the surface density of the GABAA receptors, and p(c) is the dose–response function that represents the open probabilities of GABAA receptor channels at the GABA concentration c (EC50 = ∼7.5 μM, Hill coefficient = 1.6; Feigenspan et al. 2000). The concentration distribution of GABA c(r,t), as a function of the radial distance r from the point source at the time t in an infinite volume, is given by the following form (Crank 1975)

|

(2) |

where N is the total number of molecules at the releasing point, D is the diffusion coefficient, and r = (x2 + y2 + z2)1/2 is the three-dimensional radius distance from the origin. Because we considered three-dimensional diffusion over the plane of the membrane, the c(r, t) was doubled. We tested GABA diffusion coefficients of 0.2 and 0.6 μm2/ms, because the estimated diffusion coefficient at the synapse ranges from 0.03 to 0.37 μm2/ms (Overstreet et al. 2002; Pugh and Raman 2005), and 0.6 μm2/ms is the experimentally determined value for catecholamines freely diffusing in solution (Gerhardt and Adams 1982). The total current is obtained by integrating Eq. 1 over the area of the plasma membrane surrounding the release site (up to a 5-μm radius)

|

(3) |

Because GABA rapidly diffuses into the surrounding fluid after the opening of a fusion pore, I is also a function of time.

Graphs were constructed with Origin 6.1J (OriginLab).

RESULTS

Retinas of transgenic mice that express human PLAP under control of a promoter sequence of the gene for TH were dissociated by enzymatic digestion and mechanical trituration. Because PLAP resides on the outer surface of the cell membrane, DA cells were identified by staining with the monoclonal antibody to PLAP E6-Cy3. We exploited the presence of GABAA receptors over the surface of DA cell bodies to measure the Cl− current activated by the release of their own transmitter, a strategy used in the past for secretory cells overexpressing autoreceptors (Braun et al. 2004; Hollins and Ikeda 1997; Whim and Moss 2001).

Fine structure of solitary DA cells

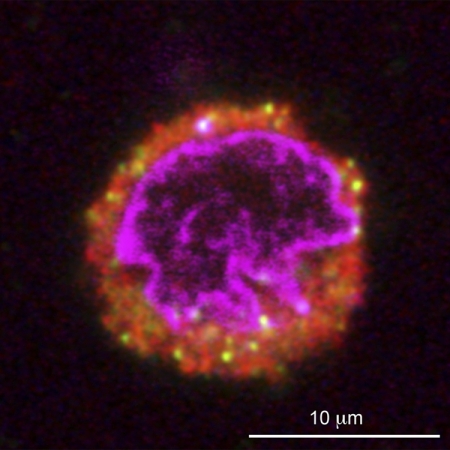

In the intact retina, some of the DA cell perikarya receive synapses from GABAergic endings, which are intensely stained by antibodies to the synaptic vesicle proteins synapsin and GABA vesicular transporter (VGAT). At the site of apposition, we invariably noted staining for gephyrin (Supplemental Fig. S2)1 , a component of the postsynaptic specialization of GABAergic (and glycinergic) synapses (see Fritschy et al. 2008). To rule out the possibility that some of these GABAergic endings were still attached to the surface of DA cells after enzymatic digestion and trituration of the retina, we triple-stained the dissociated cells with antibodies to TH, synapsin, and gephyrin and reconstructed the entire surface of several DA cells by confocal microscopy. No synaptic endings were observed at the surface of a number of DA cells (Fig. 1). As expected, some of the synaptosomes that were floating in the culture medium were occasionally adhering to the surface of the sedimented cells, including DA cells. However, we never observed the presence of gephyrin at the site of contact between synapsin-positive synaptosomes and DA cells (Supplemental Fig. S3). We could therefore exclude the presence of GABAergic synapses on isolated DA cells. Noteworthy was the presence of synapsin-positive organelles of varying diameter scattered throughout the cytoplasm of DA cells (Fig. 1). In retinal sections, a proportion of these organelles were also stained by the antibody to VGAT (Supplemental Fig. S4).

FIG. 1.

The perikarya of dopaminergic amacrine (DA) cells contain synapsin-positive organelles. The perikaryon of a DA cell after retinal dissociation is identified by the immunostaining of its cytoplasm with an antibody to TH (red). A small number of cytoplasmic organelles are immunoreactive for the synaptic vesicle proteins synapsin 1 and 2 (yellow). The nucleus (purple) is counterstained with DAPI. A confocal Z series showed that no synaptic endings were present at the surface of this cell.

Finally, we confirmed by immunocytochemistry that GABAA receptors were present on the surface of isolated DA cell bodies (Supplemental Fig. S5). A previous study on sections of the retina had in fact shown that GABAA receptors were expressed over the entire surface of DA cells and included the α4 subunit, which is exclusively extrasynaptic (Gustincich et al. 1999).

Events of GABA release from DA cell perikarya

We tested the effect of increasing concentrations of intracellular free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) on DA cell bodies patch clamped in the whole cell configuration. The concentration of Cl− was nearly equal on either side of the membrane (ECl ∼ 0 mV) and the holding potential was set at −60 mV. When the pipette contained 100 nM free Ca2+ in a CsCl-based solution, with a bath temperature of 30°C, we observed inward current transients (Fig. 2, A and B) that were reversibly suppressed by the GABAA receptor antagonists bicuculline (100 μM) and SR95531 (20 μM). In all these cells, application of exogenous 1 mM GABA elicited a 1- to 4-nA response (Fig. 2C), caused by a chloride current mediated by GABAA receptors, as previously described (Feigenspan et al. 2000). One possibility was that the current transients were caused by the release of GABA by a synaptosome accidentally stuck to the surface of the DA cell: conceivably, the DA cell released secretagogues, such as dopamine or ATP, which in turn activated the synaptosome. To rule this out, we applied to the DA cell 10 μM exogenous dopamine and 300 μM ATP (data not shown): both decreased the frequency of the GABAergic events induced by infusion of 100 nM Ca2+ (dopamine: 77.1 ± 9.2% of controls, n = 4, P < 0.05; ATP: 57.3 ± 16.9% of controls, n = 5, P < 0.01).

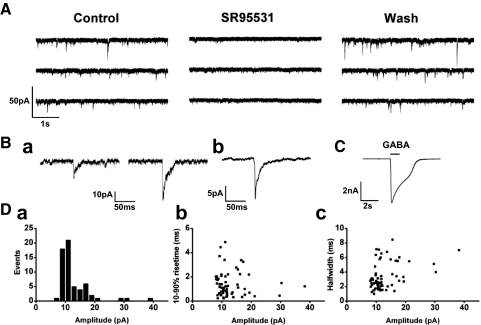

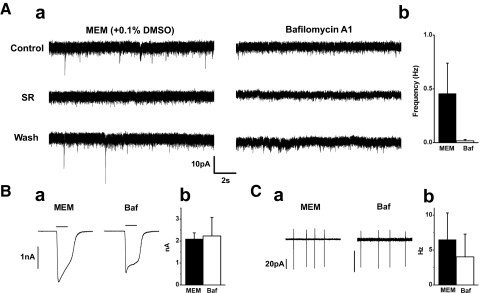

FIG. 2.

Transient events of GABA release from DA cells. A: current traces from an isolated DA cell body infused with 100 nM free Ca2+ in CsCl-based patch solution; holding potential was −60 mV. The cell exhibited inward current transients that were reversibly suppressed by bath application of SR95531 (20 μM), an antagonist at the GABAA receptor. Ba: examples of transient current events and (Bb) an averaged trace (n = 58). C: application of 1 mM GABA to the cell activated an inward current. Da: distribution of the amplitudes of the current events. The mean peak amplitude was 13.0 ± 5.5 pA (n = 61). Db: scattergram of the amplitude-rise time (10–90%) relationship. Dc: scattergram of amplitude half-width time relationship.

We defined as GABAergic events the current transients whose amplitude exceeded the background noise by twice the value of its SD. These events occurred at irregular intervals and exhibited variable amplitude, ranging between 8 and 38 pA, with a mean value of 13.0 ± 5.5 pA (n = 61; Fig. 2Da). Their 10–90% rise time was 1.4 ± 1.0 ms and their half-width 3.4 ± 1.9 ms (n = 61); neither rise nor half-width times showed clear-cut dependence on current amplitude (Fig. 2, Db and Dc). Their total duration was ≤50 ms, and their decay phase could not be described by a simple combination of exponential curves. Because the driving force for Cl−, ΔECl, was about −60 mV, the mean conductance change resulting from the GABAergic current events was calculated as nearly 220 pS.

In addition to the typical GABAergic currents described above, we observed polymorphic events, characterized by either 1) a rise time longer than 5 ms or 2) a flickering waveform that lasted for 10–20 ms. These unusual events were relatively infrequent (14.6 ± 8.3% in 1,498 events from 10 cells).

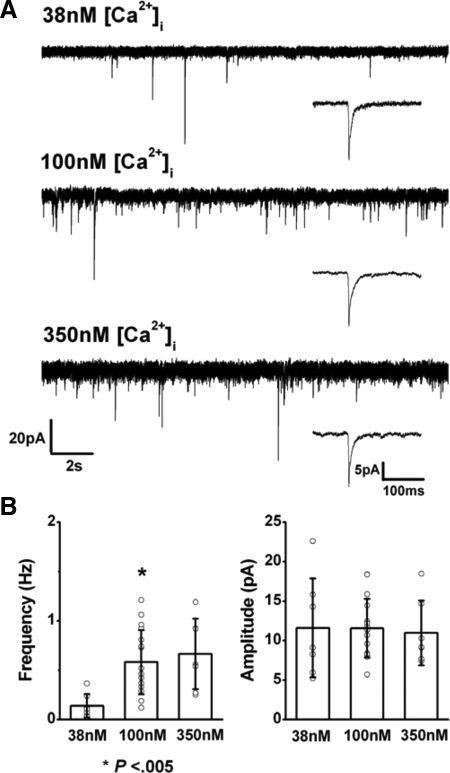

To measure the Ca2+ dependence of the GABAergic current, we examined whether rate and magnitude of the events varied with changes in intracellular free Ca2+. The mean frequency of the current events was lower when [Ca2+]i was set at 38 nM (0.14 ± 0.12 Hz, n = 7; Fig. 3 A, top) than with [Ca2+]i at 100 nM (0.58 ± 0.33Hz, n = 17; Fig. 3A, middle), and the difference was significant at P < 0.05. Increases of [Ca2+]i to 350 nM or to micromolar concentrations had no additional effect on event frequency (0.66 ± 0.35 Hz, n = 7, with 350 nM [Ca2+]i; Fig. 3A, bottom). Mean amplitude of the events did not change significantly with increments in [Ca2+]i (11.6 ± 6.3 pA at 38 nM, 11.5 ± 3.7 pA at 100 nM, and 11.0 ± 4.1 pA at 350 nM; Fig. 3B). These experiments suggested that the frequency of the GABAergic current events depended on the cytoplasmic free Ca2+ concentration and was therefore caused by exocytosis.

FIG. 3.

Events of GABA release depended on intracellular calcium. A: GABAergic current events were recorded from DA cells in which [Ca2+]i was 38 (top), 100 (middle), and 350 nM (bottom) in CsCl-based pipette solution. Holding potential was –60 mV. Insets: averaged current events with 38 (n = 19), 100 (n = 80), and 350 nM (n = 90) [Ca2+]i. B: comparison of frequency (left) and mean amplitude (right) of GABAergic currents. Frequency was significantly increased when [Ca2+]i was set at 100 nM (P < 0.005). The increment in [Ca2+]i had no significant effect on event amplitude.

Bafilomycin A1 abolished transient GABAergic currents

To confirm that DA cells released GABA by exocytosis, we examined the effect of blocking reacidification of the GABA-containing organelles after fusion with the plasma membrane and recycling by administering bafilomycin A1, a high-affinity inhibitor of vacuolar-type, proton-translocating ATPases (Cavelier and Attwell 2007; Drose and Altendorf 1997; Zhou et al. 2000). Because stimulation promotes depletion of the vesicular contents by bafilomycin A1 (Cavelier and Attwell 2007), we exploited the DA cell property of generating spontaneously action potentials in a rhythmic fashion to cause turnover of their secretory organelles. The isolated cells were therefore exposed to the blocker of the proton pump for 2 h before increasing intracellular calcium on patch clamping. The response to an intracellular CsCl-based patch solution containing 100 nM free Ca2+ was compared in bafilomycin-treated and control cells incubated in solvent alone (0.1% DMSO). In control cells, transient GABAergic currents had a frequency of 0.46 ± 0.28 Hz and an amplitude of 9.48 ± 0.90 pA (n = 7; Fig. 4 Aa, left). In the bafilomycin-treated cells, GABAergic currents were abolished (n = 12; Fig. 4Aa, right). Treatment with bafilomycin had no effect on the amplitude of the cell response to application of exogenous 1 mM GABA (2.1 ± 0.3 nA in control, n = 4; 2.2 ± 0.8 nA in test group, n = 9, P = 0.77; Fig. 4, Ba and Bb) and on the frequency of the action currents recorded in the test group (n = 12, P = 0.10; Fig. 4, Ca and Cb). We therefore confirmed that the release of GABA was mediated by a process of exocytosis.

FIG. 4.

Bafilomycin A1 abolished transient GABAergic currents. Aa: left: GABAergic current events in a DA cell pretreated with DMSO (0.1%). The events were blocked by 20 μM SR95531. Right: the GABAergic currents were abolished in a DA cell pretreated with 500 nM bafilomycin A1 in DMSO. Reduction of baseline noise by SR95531was noted in 6 of 7 cells. Both cells were infused with 100 nM [Ca2+]i in CsCl-based pipette solution. Holding potential was −60mV. Ab: pooled data of event frequency in control (n = 7; MEM) and bafilomycin A1-treated (n = 12; Baf) cells. Ba: same cells as in A. Application of a puff of 1 mM GABA activated an inward current in both the control (MEM) and bafilomycin A1-treated cell (Baf). The truncated shape of the GABA response in the treated cell is a perfusion artifact. Bb: comparison of the mean amplitude of the GABA current in control (n = 4; black bar) and test group (n = 9, P = 0.77; white bar). Ca: same cells as in A. In the cell-attached mode, pacemaker action currents were observed in both the control (MEM) and test cell (Baf). Cb: comparison of mean frequency of the action currents in control (n = 6; black bar) and test group (n = 12; white bar) shows that bafilomycin A1 treatment did not alter significantly the pacemaker activity (P = 0.10).

GABA release by DA cell perikarya was extrasynaptic

Because the perikarya of DA cells do not contain presynaptic active zones (Puopolo et al. 2001), the release of GABA caused by high intracellular free Ca2+ had to be, by necessity, extrasynaptic. To model the conditions in which a GABAergic response would mimic the rise time and amplitude of the observed current events in absence of a synapse, we first estimated the number of GABAA receptors and the single channel conductance in the isolated DA cell bodies by nonstationary noise analysis of the GABAA currents caused by application of 1 mM exogenous GABA. The number of receptors was ∼3,580 (mean from 5 cells) and, because the mean membrane capacitance was ∼6.9 fF, equivalent to an area of 690 μm2, the surface receptor density was ∼5 receptors/μm2. Single channel conductance was 14.5 pS, which was consistent with the main conductance of 29 pS and two subconductances of 20 and 9 pS measured in these cells by Feigenspan et al. (2000).

We calculated the concentration of GABA as a function of distance from the point source and time interval from exocytosis, the dose–response function of the receptor, and, finally, modeled the variation in space and time of the total current over the membrane area surrounding the release site (Supplemental Fig. S6). We found that our model reasonably predicted the rise time and amplitude of the observed current transients (Fig. 5) when the GABA point source was set from 27,000 (assuming a diffusion coefficient of 0.2 μm2/ms, the approximate value at the synapse, see methods) to 40,000 molecules (diffusion coefficient 0.6 μm2/ms, a value for free diffusion in solution).

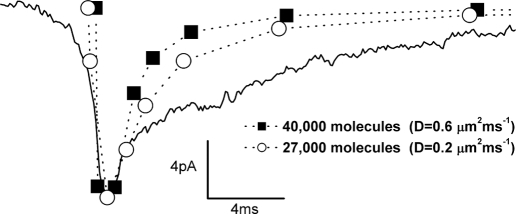

FIG. 5.

Amplitude and rise time of the GABAergic currents depend on transmitter contents. Mean GABAergic current shown in Fig. 2Bb (continuous line) and current responses obtained by mathematical modeling (dotted lines). The model reasonably predicted the amplitude and rise time of the observed current when the GABA point source was set at 27,000 with diffusion coefficient (D) of 0.2 μm2/ms (○) and 40,000 with diffusion coefficient of 0.6 μm2/ms (▪). Our model did not take into account the time course of deactivation and desensitization of the receptors; as a result, the predicted decay phases are different from the observed one.

The predicted amplitude of current events caused by exocytosis of 5,000 molecules, the conventional quantal content assigned to synaptic vesicles, was 30% of that observed experimentally. Thus exocytosis of conventional synaptic vesicles escaped detection in our experiments, probably because the transmitter concentration was close to the limits of the intrinsic sensitivity of the receptors situated in the vicinity of the release site. This explains why we failed in an attempt to raise the sensitivity of our assay by administering zolpidem, which increases GABAA receptor affinity for GABA (EC50 = 7.4 μM; Feigenspan et al. 2000). Zolpidem (2 μM) significantly increased event amplitude (133.3 ± 9.5% of control; P < 0.05; n = 6) and half decay time (173.3 ± 34.5% of control; P < 0.03; n = 6) in DA cells infused with 100 nM free Ca2+, but had no effect on event frequency (80.5 ± 15.3% of control; P = 0.28; n = 6).

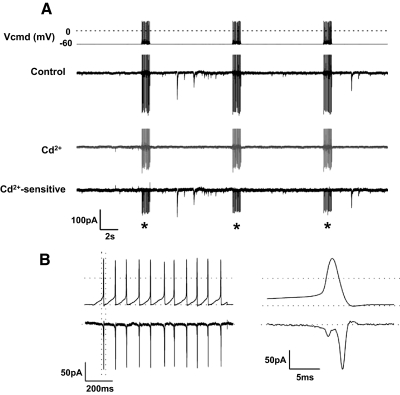

Sustained depolarization triggered GABA release by activating Ca2+ current

Evidence that GABA was released by regulated exocytosis was obtained by examining the effects on GABA release of sustained voltage-clamp depolarizations. In a total of 98 cells, different experimental protocols were applied to optimize the visibility of the current transients during and after a depolarizing pulse of 1-s duration, including changes in holding potential, extent of depolarization, and pipette Cl− and EGTA concentrations. Fifty-nine cells (60%) responded to the stimulus with a long-lasting discharge of current transients. When ECl was set near −60 mV, the holding potential was –100 or –80 mV, and intracellular EGTA was 0.02 to 0.1 mM, a pulse to –20 or –10 mV caused the appearance of outward current transients, riding on a slowly declining inward current (Fig. 6A). Latency ranged between 7 and 960 ms and the number of events varied between 1 and 9 (3.0 ± 1.6, n = 54). When, at the end of the pulse, cells were repolarized to –80 or –100 mV (ΔECl: approximately –20 or –40 mV), the current transients persisted as downward deflections for several seconds, albeit greatly decreased in amplitude. Because application of exogenous GABA evoked outward and inward Cl− currents at –100- and –10-mV holding potentials, respectively (Fig. 6B), we concluded that DA cells released GABA when depolarized. Of course, the delayed events became much more prominent (Fig. 6C) when the driving force for Cl− ions was increased by introducing high Cl− in the pipette solution (ECl: ∼0 mV, ΔECl: approximately –60 mV, 5 of 5 cells).

When the concentration of EGTA in the intracellular solution was increased to 9 mM, the events of GABA release disappeared (data not shown). This suggested that the release of GABA by sustained depolarization was caused by Ca2+ influx into the cell. In addition, the slow inward current elicited by the depolarization to –10 mV declined in the course of the 1-s stimulus, presumably because of inactivation of Ca2+ current and, possibly, activation of Ca2+-dependent current. Therefore the effects of the Ca2+ channel blocker Cd2+ were studied in DA cells moderately depolarized for 1 s to –20 mV to minimize the activation of Ca2+-related current. This stimulus evoked transient outward currents superimposed on the slow inward current (Fig. 6D, black trace). SR 95531 blocked the transients only (Fig. 6D, red trace), whereas addition of 100 μM Cd2+ to the bath solution blocked both the fast GABAergic events and the slow inward current (Fig. 6D, green trace). The effect of Cd2+ was reversible (Fig. 6D, inset). Replacement of external Ca2+ by equimolar Co2+ had the same effect as Cd2+ on the slow inward current induced by depolarization to –20 mV (n = 3; Fig. 6E), which indicates that the Cd2+-sensitive current accounted for the entire Ca2+ current.

To identify the types of Ca2+ channels responsible for the release of GABA, we examined the effects of organic blockers on both Ca2+ peak current and frequency of GABAergic events evoked by 1-s depolarizations (Fig. 6E). A saturating dose of the dihydropiridine nimodipine (2–20 μM) suppressed Ca2+ current by 29 ± 3% and GABA release by 28 ± 11% (n = 4). The phenalkylamine verapamil (100 μM), on the other hand, was more effective, because it suppressed the current by 57 ± 8% (P < 0.01) and release by 72 ± 21% (P < 0.03; n = 4). This pharmacological profile closely resembles that described for the L-type Ca2+ channels containing the α1F subunit of wide-field retinal amacrine cells (Vigh et al. 2003). The blocker of the R-type channels SNX482 (200 nM) had the same effect (P = 0.68) as nimodipine in suppressing Ca2+ current (27 ± 9%; n = 5) and nearly the same effect as verapamil (P = 0.27) in suppressing GABA release (59 ± 9%; n = 5). Blockers of P/Q type (200 nM ω-agatoxin) and N-type (1 μM ω-conotoxin) channels were much less effective than verapamil (P < 0.01) in suppressing both Ca2+ current (10 ± 6 and 10 ± 1%, respectively, n = 3 each) and GABA release (11 ± 9 and 11 ± 10%; n = 3 each). T-type Ca2+ channel current inactivating within 50 ms was not observed, in agreement with previous observations on this cell type (Feigenspan et al. 1998). These experiments show that both L-type and R-type channels play a role in activating Ca2+ current and mediating GABA release.

Depolarization with action potential waveforms triggered GABA release

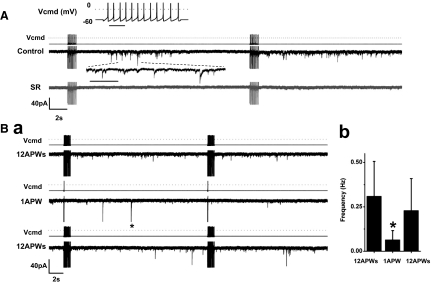

DA cells are spontaneously active both after isolation and in the intact retina (Feigenspan et al. 1998; Gustincich et al. 1997; Zhang et al. 2007, 2008), and action potentials are required for dopamine release (Piccolino et al. 1987; Puopolo et al. 2001); thus we studied whether action potentials were also effective in inducing GABA release. However, because of the protocol adopted to measure the Cl− current triggered by GABA release, we could not test directly the dependence of the release on the spontaneous activity of the cell. Thus we obtained this crucial piece of information by using the action-potential-clamp method. First, we recorded under current clamp a segment of spontaneous activity of 1-s duration from a DA cell that was firing at a frequency of 12 Hz at 30°C. This segment was used in voltage-clamp mode as a command waveform for other DA cells that were otherwise maintained at a holding potential of –60 mV and contained 115 mM CsCl to maximize the driving force for Cl−. Fourteen DA cells were repeatedly stimulated by applying trains of action potential (AP) waveforms at intervals of 20 s. Whereas in absence of stimulation the cells exhibited current transients at an exceedingly low frequency (0.08 ± 0.07 Hz, n = 4), the trains increased their frequency to 0.60 ± 0.39 Hz (P < 0.02). SR 95531 abolished the current transients (n = 6; Fig. 7A), thus proving that they were caused by events of GABA release. The duration of the discharge of GABAergic events was quite variable. In the case of Fig. 7 A, after the first train of AP waveforms, the discharge lasted ∼9 s and had a latency of 5 s, but with subsequent trains, the latency decreased and the length of the discharge increased to the point that discharges triggered by successive trains would merge into one other. To confirm that the current events were indeed caused by the trains of AP waveforms, we alternated single AP waveforms with AP trains (Fig. 7Ba). Event frequency decreased to 0.07 ± 0.05 Hz after single waveforms and returned to its initial value with train stimulation. This effect was significant in five cells (P < 0.03; Fig. 7Bb).

FIG. 7.

Depolarization with action potential waveforms triggered GABA release. A: black trace: a DA cell was stimulated with 1-s trains of 12-Hz action potential (AP) waveforms (APW) at intervals of 20 s (CsCl-based pipette solution containing 0.05 mM EGTA; 300 nM TTX added to the external solution; ECl ∼ 0 mV). Top inset: voltage command (Vcmd; bar, 200 ms). After the 1st train, the discharge lasted ∼9 s and had a latency of 5 s (the time scale of a segment is expanded at the dotted lines; bar, 200 ms), but with subsequent trains the latency decreased and the length of the discharge increased. Grey trace: SR 95531 blocked the current events. Currents during stimuli are truncated. Ba: top trace: a DA cell was stimulated with trains of 12 AP waveforms (12 Hz) at intervals of 20 s. The frequency of the GABAergic current events was 0.64 Hz. Middle trace: the same DA cell was subsequently stimulated with single AP waveforms at intervals of 20 s. The frequency of the current events decreased to 0.15 Hz. The asterisk marks a truncated event (134-pA peak amplitude). Bottom trace: when trains of AP waveforms were delivered again to the cell, the event frequency returned to 0.53 Hz. Currents during stimuli are truncated. Bb: relation between average frequency of the GABAergic events and numbers of AP waveforms delivered to the cell (n = 5; P < 0.03).

FIG. 8.

Stimulation with action potential waveforms activated Ca2+ current. A: a DA cell was stimulated with 11-Hz trains of AP waveforms at intervals of 10 s (CsCl-based pipette solution containing 0.05 mM EGTA; 300 nM TTX added to the external solution; ECl ∼ 0 mV). Top trace: the stimulus caused discharges of GABAergic events, with occasional failures. Outward currents during stimuli are truncated. Middle trace (grey): application of 100 μM Cd2+ blocked GABA release. Bottom trace: trace subtraction showed that the stimulus reproducibly activated Cd2+-sensitive inward currents (asterisks). B: left: Cd2+-sensitive currents marked by asterisks in A were averaged. Right: the time scale of the 1st current trace (rectangle) is expanded. The peak of the inward current coincided with the repolarizing phase of the AP waveform.

Next, we examined whether the depolarizations caused by trains of AP waveforms activated Ca2+ currents, which in turn elicited GABA release. On stimulation with 1-s trains of AP waveforms, recorded from a DA cell that fired action potentials at 11 Hz, and applied at intervals of 10 s (Fig. 8 A), 100 μM Cd2+ reduced the inward currents activated by the stimulus and blocked the GABAergic events. As expected (Llinás et al. 1981; see Sabatini and Regehr 1999), measurements of the Cd2+-sensitive current, obtained as the difference between the traces in absence and presence of the blocker, showed that each AP reproducibly activated a tail current that coincided with the repolarizing phase of the waveform (Fig. 8B). Application of niflumic acid (50 μM) had no effect on the amplitude of the tail current (data not shown), suggesting that this component was not the result of a Ca2+-activated Cl− current. The total charge transferred by a train of AP waveforms was 4.5 ± 0.9 pC and that transferred by a single AP was 415 ± 87 fC (n = 9). The results of these experiments strongly suggest that the pacemaking activity of DA cells triggers the release of GABA by activating Ca2+ tail currents.

Effects of high-frequency stimulation

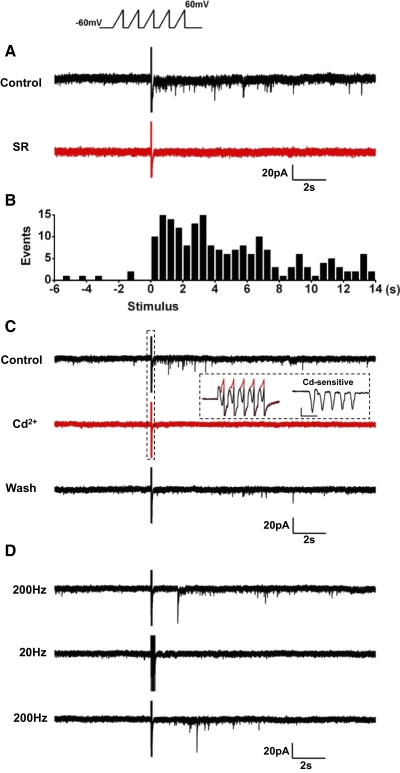

Although Ca2+ entry for each AP waveform was brief, repetitive depolarizations may have caused summation of residual intracellular Ca2+ to the level required to trigger GABA release. If this was the case, brief, repetitive, high-frequency depolarizations, much shorter than the trains of AP waveforms should be more effective in causing GABA release. We therefore delivered trains of five 6- to 10-ms ramps (from 9 to 20 mV/ms) at a frequency of 200 Hz, which depolarized DA cells from –60 mV to +60 mV. Single trains were used, so that latency and duration of the response could be measured. To maximize the driving force for Cl− ions, the pipette solution contained high Cl− (ECl: ∼0 mV). In 12 cells, the frequency of the current events in absence of stimulation was 0.03 ± 0.09 Hz. On stimulation, the frequency of the discharge doubled that recorded with AP waveforms (1.2 ± 0.6 Hz; Fig. 9 A), whereas the peak amplitude of the current events was the same as that reported for the experiments of Ca2+ infusion (13 ± 10 pA). The latency was 0.5 s to a few seconds, and the duration was 10–14 s, as shown in the histogram of Fig. 9B (data pooled from 12 cells, 198 events). The responses were blocked by both SR95531 (n = 4; Fig. 9A) and 100 μM Cd2+ (n = 6; Fig. 9C), and the Cd2+ block was accompanied by suppression of the Ca2+ current elicited by the ramps (Fig. 9C, inset). On average, the charge transferred by a train of ramps was 2.3 ± 0.4 pC and that transferred by a single ramp was 464 ± 85 fC (n = 5). Thus, although the total charge transferred by each train of ramps was about one half that transferred by each train of AP waveforms (4.5 pC), the duration of the delivery was two orders of magnitude shorter (6–10 ms vs. 1 s). This finding confirms that repetitive depolarizations may cause summation of residual intracellular Ca2+ to the level required to trigger GABA release. In fact, the ramp stimulation was ineffective when the frequency of the pulses in each train was reduced to 20 Hz (n = 5; Fig. 9D), which is close to the frequency of the trains of AP waveforms.

FIG. 9.

Effects of stimulation with high-frequency trains of ramps. A: DA cell was depolarized with trains of 5 ramps (20 mV/ms) from –60 to +60 mV, delivered at a frequency of 200 Hz (CsCl-based patch solution containing 0.02 mM EGTA; ECl ∼ 0 mV). The stimulus caused a discharge of current events (black trace) that were abolished by 20 μM SR95531 (red trace). Currents during stimulus are truncated. B: latency histogram (12 cells, 198 events). C: DA cell was depolarized with trains of 5 ramps (12 mV/ms) from –60 to +60 mV, delivered at a frequency of 200 Hz (CsCl-based patch solution containing 0.02 mM EGTA; 300 nM TTX added to the external solution; ECl ∼ 0 mV). GABAergic currents (top trace, black) are abolished by 100 μM Cd2+ (middle trace, red) and restored after washout (bottom trace, black). Inset, left: current traces of the ramp stimulus are seen on an expanded time scale before (black) and after Cd2+ treatment (red). Inset, right: the Cd2+-sensitive current was obtained by subtraction (scale, 20 ms and 50 pA). D: DA cell was depolarized with trains of 5 ramps (9 mV/ms) from –60 to +60 mV, delivered at 2 frequencies: 200 and 20 Hz (CsCl-based patch solution containing 0.02 mM EGTA; 300 nM TTX added to the external solution; ECl ∼ 0 mV). Top trace: GABAergic currents appeared after each train when ramp frequency was 200 Hz. Middle trace: GABAergic currents were absent when ramp frequency was 20 Hz. Bottom trace: the discharge reappeared when ramp frequency was set back to 200 Hz. Currents of stimulus are truncated.

GABA release was also observed when ECl was set at the more physiological level of −60 mV by introducing a CsMeSO3-based pipette solution and the holding potential was set at –100 mV (ΔECl: approximately –40 mV). The release events were present but fewer and lower in amplitude.

DISCUSSION

Isolated perikarya of retinal DA cells generated transient Cl− currents when intracellular free Ca2+ was raised to 100 nM. The currents were caused by events of GABA release because they were suppressed by antagonists at the GABAA receptors. Convincing evidence supported the conclusion that GABA was released by the very DA cells we were recording from and acted on the cells' native GABAA receptors that functioned as autoreceptors: 1) DA cell perikarya contain organelles stained by antibodies to GABA (Contini and Raviola 2003), GAD (Kosaka et al. 1987; Wässle and Chun 1988; Wulle and Wagner 1990), synapsin (Fig. 1), synaptobrevin 2 (VAMP2) (Witkovsky et al. 2008), and VGAT (Witkovsky et al. 2008 and unpublished observations); 2) GABAA receptors are present on the cell surface, including the alpha4 subunit, which is exclusively extrasynaptic (Gustincich et al. 1999) and the isolated perikarya respond to application of exogenous GABA with a chloride current mediated by GABAA receptors (Feigenspan et al. 2000); 3) examination of the surface of isolated DA cells by confocal microscopy, after staining with antibodies to both synapsin and gephyrin, ruled out the possibility that GABAergic endings presynaptic to DA cell bodies had survived the procedure of enzymatic digestion and trituration used for retinal dissociation; 4) we also ruled out the possibility that GABA was released by occasional synaptosomes adhering to the surface of the DA cell perikarya after dissociation, because the frequency of the GABAergic currents depended on the concentration of intracellular free Ca2+ in the patch pipette and increased on membrane depolarization; 5) furthermore, we excluded the possibility that these maneuvers caused the release by DA cells of secretagogues that could depolarize adjacent synaptosomes, because administration of exogenous dopamine or ATP decreased the frequency of the GABAergic events; and 6) Release of GABA did not decline with prolonged exposure to high [Ca2+]i (≤1 h), as expected of synaptic endings severed from the parent cell.

GABA release was extrasynaptic because presynaptic active zones are absent in the perikarya of DA cells (Puopolo et al. 2001). Furthermore, it was caused by exocytosis, rather than by a transporter-mediated process, because GABAergic currents were transient on the millisecond time scale and thus resembled the miniature synaptic currents recorded from hippocampal GABAergic synapses (Edwards et al. 1990). Second, GABA release was abolished by the treatment with bafilomycin A1, a blocker of the vesicular proton pump, and, third, was dependent on the intracellular Ca2+concentration. We therefore concluded that, on fusion of a membrane-bounded, GABA-containing organelle with the plasma membrane, the released transmitter diffused from the site of exocytosis into the surrounding solution and activated nearby GABAA receptor channels randomly distributed over the plasma membrane. To establish whether such a mechanism could account for the transient waveform of the observed GABAergic currents, we built a mathematical model of the total current over the area of the plasma membrane surrounding the release site as a function of time and distance. This model predicted the amplitude and rise time of the observed current transients when the size of the source of GABA was set at 27,000–40,000 molecules, a quantal content of the same order of magnitude as that measured by amperometry in the case of dopamine exocytosis (40,000 molecules; Puopolo et al. 2001). This suggests that the GABA-containing organelles responsible for the current events detected in our experiments were larger than conventional 40-nm synaptic vesicles and could correspond to the tubules, cisterns, dense core vesicles (80–125 nm diam) or granules (300 nm diam) that are commonly observed in electron micrographs of the cytoplasm of the perikarya of DA cells (data not shown). It is possible, of course, that small GABA-containing vesicles were also opening at the cell surface, but these events were buried in the background noise of the recordings.

Release of GABA was stimulated by depolarization of the cell membrane: among the stimuli applied, square pulses were the most effective in increasing the frequency of the discharge (1–9 Hz). Trains of action potentials were the least effective (0.6 Hz), but the frequency of the discharge doubled when the frequency of the spikes was increased by one order of magnitude (1.2 Hz). These results are explained by the different effectiveness of the various stimuli in causing a surge of intracellular Ca2+ to the level required to trigger GABA release. With depolarizing stimuli, the critical features that distinguished extrasynaptic from synaptic GABA release were 1) long latency, 2) low frequency, and 3) long duration of the discharge: these properties were the consequence of the absence of presynaptic active zones and reflected a slow recruitment of organelles that were few in number and situated at a considerable distance from one another and from the cell membrane, as seen in specimens stained with synapsin antibodies (Fig. 1). Only with sustained depolarizing pulses, the latency of the discharge was occasionally shorter than a millisecond and therefore in the range of that reported in chromaffin cells for both the rapidly and slowly releasable pools (time constants 20–40 and ∼200 ms, respectively; Rettig and Neher 2002; Sørensen 2004). This implies that some of the GABAergic organelles were situated very close to the cell membrane or underwent multiple cycles of exocytosis, endocytosis, and refilling.

With all modalities of stimulation, the events of GABA release exhibited considerable variability in their amplitude (from 8 to 38 pA). Because of the paucity of secretory organelles, it seems unlikely that this variability reflected summation of multiple events of exocytosis, simultaneously occurring at different sites over the surface of DA cells. In fact, when we raised [Ca2+]i, the increment in release rate was not accompanied by an increase in the mean amplitude of the GABAergic currents. Rather, the variation in amplitude could have been a function of the distance of the activated GABAA receptors from the site of exocytosis, heterogeneity in the diameter of the organelles, or variability in their transmitter contents. In this light, one can also explain the occurrence of polymorphic events, with prolonged rise or decay time, and flickering waveforms.

Finally, in extrasynaptic release, the coupling between Ca2+ influx and transmitter exocytosis had to be extremely loose compared with the synapse: 1) Ca2+ channel and release site were probably widely separated (Neher 1998); 2) the Ca2+-dependent priming of the secretory organelles occurred on the time scale of tens of seconds (Rettig and Neher 2002; Sørensen 2004); and 3) trains of brief depolarizations could have generated Ca2+ microdomains (Neher 1998) associated with Ca2+ influx or Ca2+ mobilization, which altered the uniformity of Ca2+ distribution in the cell and therefore influenced the time course of GABA release.

The frequency of the GABAergic currents appeared to plateau at 350 nM [Ca2+]i, which indicated that control of extrasynaptic GABA release was restricted to a dynamic range of calcium concentrations much narrower than that described at the synapse. The simplest explanation for this result is that the size of the releasable pool of large GABAergic organelles in a DA cell perikaryon is small compared with that of the synaptic vesicle population contained in a presynaptic ending. It must be noted that values of [Ca2+]i <350 nM would be effective in causing GABA release in response to the action potentials spontaneously generated by this active cell, because Choi et al. (2003) showed that cytoplasmic calcium is ∼100 nM in pacemaking dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra and decreases to tens of nanomoles when the spontaneous activity is blocked by TTX.

When we applied organic blockers of L-, R-, and P/Q types of Ca2+ channels, each of them incompletely suppressed the Ca2+ current in DA cells. Our data therefore corroborate the observations by Witkovsky et al. (2006) that α1F, α1E, and α1A subunits of the Ca2+ channels are present at the surface of DA cell bodies. GABA release, on the other hand, was caused by a nearly equal contribution of L-type channels, probably containing the α1F subunit, and R-type channels. This result seems at variance with the observation that dopamine exocytosis in DA cells is completely suppressed by nimodipine (Puopolo et al. 2001), but blockers for other types of channels were not tested in that study.

The release of dopamine by DA cells is a well-understood example of the function of paracrine secretion or volume transmission in the nervous system: this modulator acts on both near and distant targets, setting the neural networks of the retina for vision in bright light. In turn, the GABA released extrasynaptically by DA cells may exert a local feedback on the parent neuron to dampen the frequency of its spontaneous firing. In addition, DA cells are not the only neurons in the retina that release GABA extrasynaptically, because in the course of this study, we repeatedly measured spontaneous GABAergic currents from isolated cell bodies of nondopaminergic cells in our short-term cultures of dissociated retinas (data not shown). Considering that about one half of the 26 types of amacrine cells are GABAergic (in the rabbit; Strettoi and Masland 1996), paracrine secretion may sustain a non-negligible concentration of GABA in the intercellular spaces of the inner plexiform layer (IPL), despite the uptake of this transmitter by Müller glial cells (Biedermann et al. 2002). Thus the ubiquitous presence of extracellular GABA may control the excitability of the neural processes in the IPL by acting on metabotropic GABAB receptors that are widely expressed on amacrine and ganglion cells (reviewed by Yang 2004), as well as on ionotropic GABAA and GABAC receptors, both synaptic and extrasynaptic. In fact, tonic GABAergic currents have been reported in bipolar cell terminals (Hull et al. 2006; Palmer 2006) and starburst amacrine cells (Wang et al. 2007). The IPL is unique in the nervous system because in its five 10-μm-thick strata are segregated the synapsing processes of >50 different types of neurons, each encoding different parameters of the light stimuli: the glutamatergic synapses connecting off-cone bipolars to off-ganglion cells in stratum 2 are adjacent to the glutamatergic synapses between on-cone bipolars and on-ganglion cells in stratum 3 (Supplemental Fig. S1). It is known that block of GABAC receptors unmasks a sizeable off excitation in on-ganglion cells whose dendrites ramify close to the on-off border (Roska and Werblin 2001). Thus the presence of GABA in the intercellular spaces of the IPL may be essential in counteracting the spillover of signals from the off- and on-sublaminae and thus contribute to Roska and Werblin's “vertical inhibition” between strata.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Eye Institute Grant EY-01344. H. Hirasawa was supported in part by a Dana/Mahoney Neuroscience Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank B. P. Bean, W. Regehr, and E. A. Schwartz for discussions, W. Siegart for the antibody to the γ2 subunit of the GABAA receptor, R. H. Edwards for the antibody to VGAT, and H. Lu for technical assistance.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

REFERENCES

- Bers DM, Patton CW, Nuccitelli R. A practical guide to the preparation of Ca(2+) buffers. Methods Cell Biol 40: 3–29, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biedermann B, Bringmann A, Reichenbach A. High-affinity GABA uptake in retinal glial (Müller) cells of the guinea pig: electrophysiological characterization, immunohistochemical localization, and modeling of efficiency. Glia 39: 217–228, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M, Wendt A, Birnir B, Broman J, Eliasson L, Galvanovskis J, Gromada J, Mulder H, Rorsman P. Regulated exocytosis of GABA-containing synaptic-like microvesicles in pancreatic beta-cells. J Gen Physiol 123: 191–204, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KJ, Takada M, Hattori T. Co-localization of tyrosine hydroxylase and glutamate decarboxylase in a subpopulation of single nigrotectal projection neurons. Brain Res 558: 239–244, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavelier P, Attwell D. Neurotransmitter depletion by bafilomycin is promoted by vesicle turnover. Neurosci Lett 412: 95–100, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YM, Kim SH, Uhm DY, Park MK. Glutamate-mediated [Ca2+]c dynamics in spontaneously firing dopamine neurons of the rat substantia nigra pars compacta. J Cell Sci 116: 2665–2675, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuhma N, Zhang H, Masson J, Zhuang X, Sulzer D, Hen R, Rayport S. Dopamine neurons mediate a fast excitatory signal via their glutamatergic synapses. J Neurosci 24: 972–981, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contini M, Raviola E. GABAergic synapses made by a retinal dopaminergic neuron. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 1358–1363, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crank J The Mathematics of Diffusion (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford, 1975, p. 28–29.

- Dal Bo G, St-Gelais F, Danik M, Williams S, Cotton M, Trudeau LE. Dopamine neurons in culture express VGLUT2 explaining their capacity to release glutamate at synapses in addition to dopamine. J Neurochem 88: 1398–1405, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derouiche A, Asan E. The dopamine D2 receptor subfamily in rat retina: ultrastructural immunogold and in situ hybridization studies. Eur J Neurosci 11: 1391–1402, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waele P, De Groote G, Van De Voorde A, Fiers W, Franssen JD, Herion P, Urbain J. Isolation and identification of monoclonal antibodies directed against human placental alkaline phosphatase. Arch Int Physiol Biochim Biophys 90: B21, 1982.

- Drose S, Altendorf K. Bafilomycins and concanamycins as inhibitors of VATPases and PATPases. J Exp Biol 200: 1–8, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FA, Konnerth A, Sakmann B. Quantal analysis of inhibitory synaptic transmission in the dentate gyrus of rat hippocampal slices: a patch-clamp study. J Physiol 430: 213–249, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigenspan A, Gustincich S, Bean BP, Raviola E. Spontaneous activity of solitary dopaminergic cells of the retina. J Neurosci 18: 6776–6789, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigenspan A, Gustincich S, Raviola E. Pharmacology of GABA(A) receptors of retinal dopaminergic neurons. J Neurophysiol 84: 1697–1707, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremeau RT, Burman J, Qureshi T, Tran CH, Proctor J, Johnson J, Zhang H, Sulzer D, Copenhagen DR, Storm-Mathisen J, Reimer RJ, Chaudhry FA, Edwards RH. The identification of vesicular glutamate transporter 3 suggests novel modes of signaling by glutamate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 14488–14493, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Harvey RJ, Schwarz G. Gephyrin: where do we stand, where do we go? Trends Neurosci 31: 257–264, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt G, Adams RN. Determination of diffusion coefficients by flow injection analysis. Anal Chem 54: 2618–2620, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gleason E, Borges S, Wilson M. Electrogenic Na-Ca exchange clears Ca2+ loads from retinal amacrine cells in culture. J Neurosci 15: 3612–3621, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Hernández T, Barroso-Chinea P, Acevedo A, Salido E, Rodríguez M. Colocalization of tyrosine hydroxylase and GAD65 mRNA in mesostriatal neurons. Eur J Neurosci 13: 57–67, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustincich S, Feigenspan A, Sieghart W, Raviola E. Composition of the GABA(A) receptors of retinal dopaminergic neurons. J Neurosci 19: 7812–7822, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustincich S, Feigenspan A, Wu DK, Koopman LJ, Raviola E. Control of dopamine release in the retina: a transgenic approach to neural networks. Neuron 18: 723–736, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollins B, Ikeda SR. Heterologous expression of a P2x-purinoceptor in rat chromaffin cells detects vesicular ATP release. J Neurophysiol 78: 3069–3076, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull C, Li GL, von Gersdorff H. GABA transporters regulate a standing GABAC receptor-mediated current at a retinal presynaptic terminal. J Neurosci 26: 6979–6984, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce MP, Rayport S. Mesoaccumbens dopamine neuron synapses reconstructed in vitro are glutamatergic. Neuroscience 99: 445–456, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KT, Koh DS, Hille B. Loading of oxidizable transmitters into secretory vesicles permits carbon-fiber amperometry. J Neurosci 20: RC101, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kosaka T, Kosaka K, Hataguchi Y, Nagatsu I, Wu JY, Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J, Hama K. Catecholaminergic neurons containing GABA-like and/or glutamic acid decarboxylase-like immunoreactivities in various brain regions of the rat. Exp Brain Res 66: 191–210, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavin A, Nogueira L, Lapish CC, Wightman RM, Phillips PE, Seamans JK. Mesocortical dopamine neurons operate in distinct temporal domains using multimodal signaling. J Neurosci 25: 5013–5023, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás R, Steinberg IZ, Walton K. Presynaptic calcium currents in squid giant synapse. Biophys J 33: 289–321, 1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher BJ, Westbrook GL. Co-transmission of dopamine and GABA in periglomerular cells. J Neurophysiol 99: 1559–1564, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E Vesicle pools and Ca2+ microdomains: new tools for understanding their roles in neurotransmitter release. Neuron 20: 389–399, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet LS, Westbrook GL, Jones MV. Measuring and modeling the spatiotemporal profile of GABA at the synapse. In: Transmembrane Transporters, edited by Quick M. W. Wiley-Liss, Hoboken, NJ, 2002.

- Palmer MJ Functional segregation of synaptic GABAA and GABAC receptors in goldfish bipolar cell terminals. J Physiol 577: 45–53, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolino M, Witkovsky P, Trimarchi C. Dopaminergic mechanisms underlying the reduction of electrical coupling between horizontal cells of the turtle retina induced by d-amphetamine, bicuculline, and veratridine. J Neurosci 8: 2273–2284, 1987. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh JR, Raman IM. GABAA receptor kinetics in the cerebellar nuclei: evidence for detection of transmitter from distant release sites. Biophys J 88: 1740–1754, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puopolo M, Hochstetler SE, Gustincich S, Wightman RM, Raviola E. Extrasynaptic release of dopamine in a retinal neuron: activity dependence and transmitter modulation. Neuron 30: 211–225, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettig J, Neher E. Emerging roles of presynaptic proteins in Ca++-triggered exocytosis. Science 298: 781–785, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roska B, Werblin F. Vertical interactions across ten parallel, stacked representations in the mammalian retina. Nature 410: 583–587, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini BL, Regehr WG. Timing of synaptic transmission. Annu Rev Physiol 61: 521–542, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen JB Formation, stabilisation and fusion of the readily releasable pool of secretory vesicles. Pfluegers 448: 347–362, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strettoi E, Masland RH. The number of unidentified amacrine cells in the mammalian retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 14906–14911, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strettoi E, Raviola E, Dacheux RF. Synaptic connections of the narrow-field, bistratified rod amacrine cell (AII) in the rabbit retina. J Comp Neurol 325: 152–168, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Joyce MP, Lin L, Geldwert D, Haber SN, Hattori T, Rayport S. Dopamine neurons make glutamatergic synapses in vitro. J Neurosci 18: 4588–4602, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veruki ML, Wässle H. Immunohistochemical localization of dopamine D1 receptors in rat retina. Eur J Neurosci 8: 2286–2297, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigh J, Solessio E, Morgans CW, Lasater EM. Ionic mechanisms mediating oscillatory membrane potentials in wide-field retinal amacrine cells. J Neurophysiol 90: 431–443, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CT, Blankenship AG, Anishchenko A, Elstrott J, Fikhman M, Nakanishi S, Feller MB. GABAA receptor-mediated signaling alters the structure of spontaneous activity in the developing retina. J Neurosci 27: 9130–9140, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wässle H, Chun MH. Dopaminergic and indoleamine-accumulating amacrine cells express GABA-like immunoreactivity in the cat retina. J Neurosci 8: 3383–3394, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whim MD, Moss GW. A novel technique that measures peptide secretion on a millisecond timescale reveals rapid changes in release. Neuron 30: 37–50, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkovsky P Dopamine and retinal function. Doc Ophthalmol 108: 17–40, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkovsky P, Gábriel R, Krizaj D. Anatomical and neurochemical characterization of dopaminergic interplexiform processes in mouse and rat retinas. J Comp Neurol 510: 158–174, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkovsky P, Shen C, McRory J. Differential distribution of voltage-gated calcium channels in dopaminergic neurons of the rat retina. J Comp Neurol 497: 384–396, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulle I, Wagner HJ. GABA and tyrosine hydroxylase immunocytochemistry reveal different patterns of colocalization in retinal neurons of various vertebrates. J Comp Neurol 296: 173–178, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XL Characterization of receptors for glutamate and GABA in retinal neurons. Prog Neurobiol 73: 127–150, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D-Q, Wong KY, Sollars PJ, Berson DM, Pickard GE, McMahon DG. Intraretinal signaling by ganglion cell photoreceptors to dopaminergic amacrine neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 14181–14186, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D-Q, Zhou T-R, McMahon DG. Functional heterogeneity of retinal dopaminergic neurons underlying their multiple roles in vision. J Neurosci 27: 692–699, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Petersen CC, Nicoll RA. Effects of reduced vesicular filling on synaptic transmission in rat hippocampal neurones. J Physiol 525: 195–206, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.