Abstract

This communication describes the rational design and synthesis of a remarkably stable PdIV mono-aryl fluoride complex (t-Bu-bpy)PdIV(p-FC6H4)(F)2(FHF) (t-Bu-bpy = 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine). This and related complexes undergo Ar-F bond formation in the presence of “F+” sources. This work serves as a foundation for the development of a PdII/IV catalyzed coupling reactions to form aryl fluorides.

Aryl fluorides are important components of many biologically active molecules, including pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and PET imaging agents.1,2 While a variety of synthetic approaches are available for generating sp3 C–F bonds,2 there are relatively few general and practical methods for the formation of aryl fluorides.2–4 To date, the most common routes to these molecules involve fluorination of aryl diazonium salts (the Balz-Schiemann reaction)3a and other nucleophilic aromatic substitution reactions with F−.3b,4 However, these transformations have significant limitations (e.g., modest scope, the requirement for potentially explosive reagents, low yields, and long reaction times), and new synthetic methods are of great current interest.

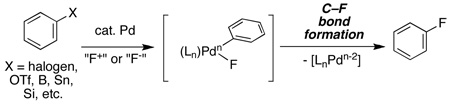

An attractive approach to address this challenge would be the development of a Pd-catalyzed coupling reaction to produce aryl fluorides. As shown in eq 1, Ar–F bond-formation from a Pd(Ar)(F) species would be a key step in these processes. Analogous Ar–X (X = Cl, Br, and I) bond-forming reactions at PdII(Ar)(X) complexes are well-precedented; 5,6 however, achieving Ar–F coupling from PdII(Ar)(F) adducts has proven extremely challenging. Instead, these PdII complexes are prone to a variety of side reactions,4,7 and aryl fluorides have only been obtained in low yields with a highly activated p-NO2-substituted aryl group.7

|

(1) |

In contrast, several recent reports have shown that aryl fluorides can be formed by reacting PdII–Ar complexes with electrophilic fluorinating reagents.8,9 For example, in 2006, our group demonstrated the PdII-catalyzed ligand-directed fluorination of Ar–H bonds with N-fluoropyridinium reagents.8 Subsequently, stoichiometric reactions of PdII σ-aryl species with N-fluoropyridinium salts were shown to afford modest yields of aryl fluorides,9a and a related stoichiometric reaction with Selectfluor was recently optimized.9b In all cases, mechanisms involving C–F bond formation from transient PdIV(Ar)(F) intermediates were suggested; however, until a recent report by Ritter,9c little evidence was available to support these proposals.10,11 We report herein on the design, synthesis, and reactivity of an isolable PdIV(Ar)(F) complex. This work provides a basis for the development of new PdII/IV-catalyzed Ar–F coupling reactions.

Our goal was to design an observable PdIV(Ar)(F) species in order to study its reactivity towards Ar–F bond-formation. Prior work suggested that such a PdIV complex should be stabilized by rigid bidentate sp2 N-donor ligands such as 2,2′-bipyridine (bpy).11,12 We also reasoned that multiple fluoride ligands would enhance the stability of the desired intermediate, as PdF4 was one of the first reported compounds with Pd in the +4 oxidation state.13 Based on these considerations, (t-Bu-bpy)PdIV(Ar)(F)3 (t-Bu-bpy = 4,4′-di-t-butyl- 2,2′-bipyridine) was identified as our synthetic target.

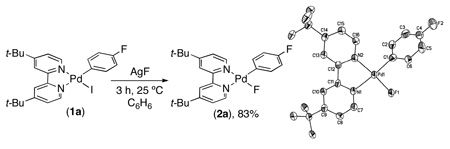

The PdII precursor (t-Bu-bpy)PdII(p-FC6H4)(F) (2a) was prepared by sonication of (t-Bu-bpy)PdII(p-FC6H4)(I) (1a) with AgF (eq 2).14a Analysis of 2a by 19F NMR spectroscopy showed a characteristic broad resonance at −340.7 ppm (PdF) as well as a peak at −122.9 ppm (ArF) in a 1 : 1 ratio. The 1H NMR spectrum of 2a contained signals indicative of an unsymmetrical square planar PdII complex, with the 6- and 6’-protons of the t-Bu-bpy ligand appearing at 8.08 ppm and 8.74 ppm, respectively. X-ray crystallographic analysis provided further confirmation of the structure of 2a (eq. 2).14b

|

(2) |

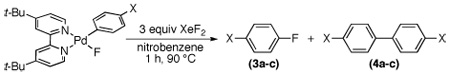

We next examined the reactivity of 2a with electrophillic fluorinating reagents. Gratifyingly, the combination of 2a with 3 equiv of XeF2 in nitrobenzene at 90 °C for 1 h afforded 1,4-difluorobenzene, 3a, in 57% yield (Table 1, entry 1). Notably, the biaryl species 4a was also generated as a minor side product (7% yield). This C–F bond-forming reaction also proceeded efficiently with electronically diverse Ar groups. For example, PdII(Ar)(F) complexes containing electron withdrawing (2b) and donating (2c) substituents on the Ar rings also reacted with XeF2 to afford aryl fluorides (3b and 3c) in comparable yields to 2a (Table 1).15,16

Table 1.

C–F Bond Formation with Electronically Diverse Ar Groups

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | X | complex | %3 | %4 |

| 1 | F | 2a | 57 | 7 |

| 2 | CF3 | 2b | 60 | 3 |

| 3 | OMe | 2c | 45 | 6 |

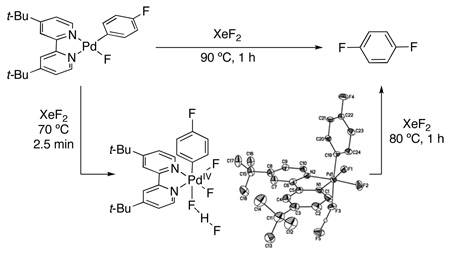

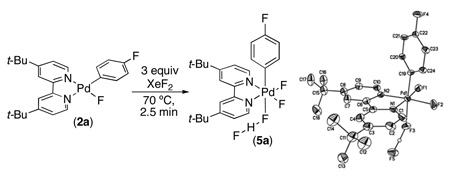

The fluorination of 2a was monitored at lower temperatures in an effort to observe a reactive intermediate. We were delighted to find that stirring 2a with XeF2 at 70 °C for 2.5 min afforded a new organometallic species (5a), which was isolated in 38% yield by recrystallization from THF/pentanes. The 19F NMR spectrum of 5a at 25 °C showed three broad resonances in a 1 : 1 : 2 ratio at −117.2 (ArF), −206.3 (PdF), and −257.4 (PdF) ppm, respectively. When this solution was cooled to −70 °C, a fourth resonance was observed as a doublet of doublets at −177.6 ppm; furthermore, the Pd–F peaks sharpened considerably and appeared as a multiplet (−204.4 ppm) and a doublet (−256.9 ppm). This spectroscopic data, along with a doublet of doublets at 12.7 ppm in the low temperature 1H NMR spectrum, is consistent with the formulation of 5a as (t-Bu-bpy)PdIV(Ar)(F)2(FHF).17 This structure was confirmed by X-ray crystallography (eq. 3). The HF in this system is likely due to the reaction of XeF2 with adventitious water.18 Notably, this is the first reported example of a PdIV bifluoride. In addition, 5a is, to our knowledge, the only isolable mono-aryl PdIV species where the σ-aryl ligand is not stabilized by a chelating ortho-substituent.19

|

(3) |

We next investigated the reactivity of 5a towards Ar–F bond-forming reductive elimination. Intriguingly, heating this complex at 80 °C for 1 h in nitrobenzene led to only traces of aryl fluoride 3a. Instead, significant quantities (35%) of biaryl 4a were observed (Table 2, entry 1).20 This is in surprising contrast to a related PdIV aryl fluoride, which underwent quantitative C–F bond-forming reductive elimination upon thermolysis.9c This result suggests that direct C–F coupling at 5a is slow relative to σ-aryl exchange between Pd centers (which is the likely pathway to Ar–Ar coupling).21 The aryl exchange process is likely facilitated in this system because the σ-aryl group is not stabilized by a chelating group.9c,21

Table 2.

C–F Bond-Forming Reactions of 5a.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | "F+" | 3a | 4a |

| 1 | none | trace | 35% |

| 2 | XeF2 | 92% | 4% |

| 3 | (PhSO2)2NF | 83% | <1% |

| 4 |  |

50% | 2% |

We noted that the stoichiometric reaction in Table 1 (as well as any catalytic C–F bond-forming reaction of this type) involves an excess of electrophilic fluorinating reagent relative to the PdIV(Ar)(F) intermediate. As such, we next investigated the thermolysis of 5a in the presence of XeF2, 1-fluoro-2,4,6-trimethylpyridinium tetrafluoroborate, and N-fluorosulfanamide. We were delighted to find that under these conditions, the C–F coupled product 3a was obtained in good to excellent yield, along with only traces (<5%) of 4a (Table 2). While the mechanism of these transformations remains under investigation,22 this result serves as a model for Ar–F formation from PdIV σ-aryl species in catalytic reactions.

The results presented herein are remarkable for several reasons. First, the facile formation of 5a suggests that the intermediacy of such PdIV bifluoride species should be considered in catalytic C–F coupling processes, particularly where water has not been rigorously excluded. Second, the fact that the σ-aryl ligand of 5a is not stabilized as part of a chelate makes this complex directly relevant to the development of Pd-catalyzed coupling reactions to form electronically diverse simple aryl fluorides. Third, the oxidant-promoted C–F coupling at 5a demonstrates the viability of this step in stoichiometric9 and catalytic8 oxidative fluorination reactions. The observed stability of 5a at room temperature also suggests that Ar–F formation may be turnover-limiting in PdII/IV-catalyzed fluorinations. Finally, the similar reactivity of electron rich and electron deficient Pd–Ar species provides further precedent for the generality of these transformations.9b

In conclusion, this communication describes the synthesis of a stable PdIV(Ar)(F)2(FHF) complex that undergoes Ar–F bond formation in the presence of “F+” sources. This work serves as a foundation for the development of PdII/IV-catalyzed couplings between electrophilic fluorinating reagents and aryl stannanes, boronic acids, and/or silanes. The development of such transformations is currently ongoing in our laboratory and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Experimental details and spectroscopic data for new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the NIH-NIGMS (RO1-GM073836 and 02S1) and Research Corporation for support. Unrestricted funding from Merck, Amgen, Eli Lilly, BMS, Abbott, GSK, Dupont, Roche, and AstraZeneca is also acknowledged. We also thank Eugenio Alvarado (NMR) and Jeff Kampf (X-ray crystallography). Finally, we thank a reviewer for the suggestion of the presence of an FHF ligand.

References

- 1.Thayer AM. Chem. Eng. News. 2006;84:15. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Kirk KL. Org. Proc. Res. Dev. 2008;12:305. and references therein. [Google Scholar]; (b) Banks RE, Tatlow JC, Smart BE. Organofluorine Chemistry: Principles and Commercial Applications. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 25–55. [Google Scholar]; (c) Gouverneur V, Greedy B. Chem. Eur. J. 2002;8:767. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20020215)8:4<766::aid-chem766>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Sun H, DiMagno SG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2050. doi: 10.1021/ja0440497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For examples, see: Balz G, Schiemann G. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1927;60:1186. Sun H, DiMagno SG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:2720. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504555..

- 4.Grushin VV. Chem. Eur. J. 2002;8:1006. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20020301)8:5<1006::aid-chem1006>3.0.co;2-m. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roy AH, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:1232. doi: 10.1021/ja0034592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Roy AH, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:13944. doi: 10.1021/ja037959h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vigalok A. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:5102. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Grushin VV, Marshall WJ. Organometallics. 2007;26:4997. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yandulov DV, Tran NT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:1342. doi: 10.1021/ja066930l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hull KL, Anani WQ, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:7134. doi: 10.1021/ja061943k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaspl AW, Yahav-Levi A, Goldberg I, Vigalok A. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:5. doi: 10.1021/ic701722f. Furuya T, Kaiser HM, Ritter T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:5993. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802164.. (c) A PdIV(Ar)(F) that undergoes C–F reductive elimination was reported while this manuscript was in preparation: Furuya T, Ritter T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10060. doi: 10.1021/ja803187x..

- 10.For an organometallic PdIV fluoride that does not undergo C–F bond-forming reductive elimination, see: Canty AJ, Traill PR, Skelton BW, White, Allan H. J. Organomet. Chem. 1992;433:213..

- 11.For related PdIV complexes that undergo C–OAc and C–Cl bond-forming reductive elimination, see: Dick AR, Kampf JW, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12790. doi: 10.1021/ja0541940. Whitfield SR, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15142. doi: 10.1021/ja077866q..

- 12.Canty AJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 1992;25:83. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao PR, Tressaud A, Bartlett N. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1976:23. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Pilon MC, Grushin VV. Organometallics. 1998;17:1774. [Google Scholar]; (b) Grushin VV, Marshall WJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:918. doi: 10.1021/ja808975a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The stoichiometric fluorination described in ref. 9b shows similar tolerance of electronically diverse σ-aryl groups and comparable/slightly higher yields.

- 16.Nearly identical yields of 3a and 4a were obtained when 1 equiv of H2O was added to the reaction of 2a with XeF2. However, the addition of 5 equiv of H2O led to an erosion of the yield of 3a (to 3%) and significant increase in the formation of 4a (75%).

- 17.Select examples of metal FHF complexes: Jasim NA, Perutz RN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:8685. Roe DC, Marshall WJ, Davidson F, Soper PD, Grushin VV. Organometallics. 2000;19:4575..

- 18.Appelman EH, Malm JG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964;86:2297. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lagunas M-C, Gossage RA, Spek AL, van Koten G. Organometallics. 2003;22:722. [Google Scholar]

- 20.The poor mass balance may be due to the formation of one or more inorganic by-products, and efforts are underway to separate/characterize these species.

- 21.For examples of related processes at PdII, see: Grushin VV, Marshall WJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:4632. doi: 10.1021/ja0602389. Cardenas DJ, Martin-Matute B, Echavarren AM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:5033. doi: 10.1021/ja056661j..

- 22.N-Bromosuccinimide also reacted with 5a to afford 3a in >95% yield, suggesting that the oxidant does not serve as the source of fluorine in the organic product. We speculate that electrophilic oxidants may react with the FHF ligand (for precedent, see ref. 17a), which in turn leads to C–F bond-forming reductive elimination from PdIV. Studies are ongoing to gain further mechanistic insights into this oxidant-promoted C–F coupling process.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental details and spectroscopic data for new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org