Abstract

Human infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis is endemic, with approximately 2 billion infected and is the most common cause of adult death due to an infectious agent. Because of the slow growth rate of M. tuberculosis and risk to researchers, other species of Mycobacterium have been employed as alternative model systems to study human tuberculosis (TB). Mycobacterium marinum may be a good surrogate pathogen, conferring TB-like chronic infections in some fish. Medaka (Oryzias latipes) has been established for over five decades as a laboratory fish model for: toxicology, genotoxicity, teratogenesis, carcinogenesis, classical genetics and embryology. We are investigating if medaka might also serve as a host for M. marinum in order to model human TB. We show that both acute and chronic infections are inducible in a dose dependent manner. Colonization of target organs and systemic granuloma formation has been demonstrated through the use of histology. M. marinum expressing green fluorescent protein (Gfp) was used to monitor bacterial colonization of these organs in fresh tissues as well as in intact animals. Moreover, we have employed the See-Through fish line, a variety of medaka devoid of major pigments, to monitor real-time disease progression, in living animals. We have also compared the susceptibility of another prominent fish model, zebrafish (Danio rerio), to our medaka-M. marinum model. We determined the course of infections in zebrafish is significantly more severe than in medaka. Together, these results indicate that the medaka-M. marinum model provides unique advantages for studying chronic mycobacteriosis.

Keywords: Danio rerio, granuloma, medaka, Mycobacterium marinum, Oryzias latipes, tuberculosis, zebrafish

1. Introduction

Worldwide, an estimated two billion humans are infected with tuberculosis (TB), which remains the most common cause of adult death due to an infectious agent (Dye et. al., 1999). The questionable efficacy of the current BCG vaccine (Ponnighaus et. al., 1992; Fine, 1995) and prevalence of latent/chronic TB makes better understanding of the host and pathogen interactions of TB of great medical importance. Difficulties in studying Mycobacterium tuberculosis include a slow growth rate (~24 hr generation time), the necessity of working in high containment biosafety level-3 (BSL-3) facilities, and expensive and non-ideal mammalian hosts (Frank and Orme, 2003). Investigators have sought surrogate mycobacterial models for M. tuberculosis pathogenesis. Major surrogate model pathogens for M. tuberculosis include Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mycobacterium marinum offering lower risk and greater ease of manipulation in the laboratory setting (Jacobs et. al., 1987; Lee et. al., 1991; Ramakrishnan and Falkow, 1994; Ramakrishnan et. al., 1997).

We would expect the ideal surrogate model pathogen to be closely related to M. tuberculosis, causing similar chronic diseases, and to be genetically tractable. M. marinum is the mycobacterial species most closely related to the M. tuberculosis complex and causes TB-like infections in many poikilothermic hosts, such as frogs and fish (Rogall et. al., 1990; Tønjum et. al., 1998). Diseases caused by M. marinum usually result in chronic infections and systemic formation of granulomas, the hallmark lesion of tuberculosis (Ramakrishnan et. al., 1997; Talaat et. al., 1998; Decostere et. al., 2004). The comparatively fast growth rate (~4 hr generation time), ability of investigators to work with lower risk (BSL-2), genetic relatedness, similar pathology to human TB, a genome sequence, and ability to genetically manipulate this mycobacterial species makes M. marinum a good model for studying mycobacterial pathogenesis (for review see Cosma et. al., 2003).

The ideal surrogate model host for human TB would be susceptible to infection by M. tuberculosis or a closely related bacterium producing a comparable chronic disease, and would also be genetically tractable. Previously described aquatic models for M. marinum infection include Goldfish (Carassius auratus), zebrafish (Danio rerio) and leopard frog (Rana pipiens) (Ramakrishnan et. al., 1997; Tallat et. al., 1998; Prouty et. al., 2003). Of these three hosts, zebrafish is not only an excellent laboratory animal but its genetics have become highly sophisticated. The zebrafish model offers numerous mutant lines (Amsterdam et. al., 1999), a completed genome sequence, the ability to make transgenic strains, and a large research community (Woods et. al., 2000). Goldfish and the leopard frog do not currently provide such resources.

Medaka (Oryzias latipes) also offers many resources, including classical genetics, an extensive database in toxicology, molecular genotoxicity and carcinogenesis, a genome project, and existing inbred and transgenic lines (Abner, 1994; Ishikawa, 2000; Winn et. al., 2000, 2001; Wittbrodt et. al., 2002; Naruse et. al., 2004; Medaka Home Page, http://biol1.bio.nagoya-u.ac.jp:8000/). In addition, medaka has technologies not yet available for zebrafish, which include the See-Through (ST) medaka, which are devoid of most major pigments, allowing organs to be observed in living individuals (Wakamatsu et. al., 2001). Furthermore, medaka has a genome of about half the size of zebrafish; with lower gene redundancies medaka may be especially suited for comparative genomics and targeted mutagenesis (Amores et. al., 1998; Ishikawa, 2000; Taylor et. al., 2003). Because medaka and zebrafish share similar resources while still having unique advantages, together they serve as useful companion models.

Prior to our experimental infections of medaka with M. marinum, the only “natural” reported mycobacterial infections were by Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium abscessus (Teska et. al., 1997; Sanders and Swaim, 2001) or unresolved species of Mycobacterium (Abner et. al., 1994). Histological studies of medaka from large colonies found high frequencies of granulomas, which have suggested endemic mycobacteriosis (Abner et. al., 1994). The only direct evidence we are aware of, for “natural” M. marinum infections in medaka were unpublished reports from facilities housing large medaka colonies (Camus, A., Mississippi State University, and Hawkins, W., University of Southern Mississippi; personal communication). Although these retrospective studies suggested Mycobacterium species can establish chronic infections in medaka, we wished to better evaluate the suitability of this host to study chronic mycobacteriosis with a known strain of M. marinum under defined conditions.

Here, we present a new experimental model for tuberculosis using medaka as the host for M. marinum. We have demonstrated the ability to produce both acute and chronic infections in a dose dependent manner. A reproducible maximum chronic dose, 50% lethal dose (LD50) and minimum acute dose has been established. Histology has revealed the formation of granulomas, a diagnostic lesion for human TB, in several visceral organs. To assist in tracking the progression of chronic infections, we have used a strain of M. marinum expressing green fluorescent protein (Gfp). Fluorescence has assisted us in not only monitoring the colonization of target organs, but also viewing formation of granuloma-like spherical aggregates of bacilli expressing Gfp within infected tissues. We have also begun to use Gfp- expressing bacteria to monitor infections, in situ, in live See Through (ST) medaka. Furthermore, a true chronic state of infection has been established in fish held out to 24 weeks post-infection. To compare our medaka-M. marinum model to the established zebrafish-M. marinum model, we have infected zebrafish under the same conditions as our medaka infections and have found the maximum chronic dose, LD50, and course of infection to differ considerably.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Bacterial Strains and Culture

M. marinum strain G13R (1218R/pG13), a strain derived from a fish outbreak isolate, was provided by Lucia Barker (University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth, Minnesota) and was used in all experiments (Barker et. al., 1999). The pG13 plasmid allows for high constitutive expression of Gfp. All cultures of M. marinum were grown in Bacto™ Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth, with the addition of Tween 80 (0.2%) and kanamycin (80 μg/mL), at 30°C shaking. Prior to inoculation of fish, 100 mL cultures were collected at an optical density 600 nm of ~1.2, washed twice in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4), and adjusted to the appropriate infective doses (colony forming units (cfu)/fish). Viable counts for each dose were determined by plating the appropriate serial dilutions onto BHI agar plates supplemented with kanamycin (80 μg/mL) and cycloheximide (100 μg/mL). Plates were incubated at 30°C for 7–12 days before counting colonies.

2.2 Medaka and Zebrafish aquaculture

Medaka (Oryzias latipes) (orange-red variety) were originally obtained from Richard Winn (University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA). Medaka (were then propagated in the laboratory and housed in self-contained 10-gallon aquaria at a maximum density of 50 adult fish per aquarium with recirculating filtration. A photoperiod of 16 h light and 8 h dark was kept in all animal facilities. Twenty percent water changes were done twice monthly. Fish were fed twice daily with bulk flake food (40% protein) and once daily with brine shrimp (Artemia sp.).

Upon transfer to the BSL-2 laboratory for inoculation with M. marinum, fish were placed in self-contained 40 L aquaria, at 12 fish per aquarium. Filtration was provided by corner filters using activated carbon and polyester filter media. Ten percent water changes were done twice weekly. AmmoLock® and Stress Zyme® (Aquarium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Chalfont, PA) were added to aquaria for the first three water changes, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This was done to counter any effect of ammonia or nitrite levels in the new aquaria while establishing a biological filter. The temperature was increased to 28°C at a rate of 2°C per day. Fish were allowed to acclimate to the new environment for two weeks prior to inoculation.

Zebrafish (strain AB) were obtained from Monte Westerfield (University of Oregon, Institute of Neuroscience, Eugene, OR, USA). Zebrafish were maintained under identical conditions as medaka. All infections and maintenance of infected animals were held in BSL-2 facilities; they were conducted as prescribed by NIH BMBL guidelines and approved by both the Institutional Biosafety Committee and by the IACUC.

2.3 Medaka inoculation with M. marinum

Prior to inoculation, fish were anesthetized with Tricaine Methanesulfonate (MS-222) (0.0175%). Medaka were injected with doses of 103 to 107 cfu M. marinum/fish. Doses were delivered by intraperitoneal injection with 20 μl of bacteria suspended in PBS, using a 26-gauge needle. Negative-control infections, or “sham-infections” were fish inoculated with sterile PBS concurrently with experimentally infected fish and kept under the same environmental conditions. Survival, gross behavior, and mortality were monitored until at least eight weeks post-infection. The dose-response experiment (shown in Fig. 1) was repeated three times and yielded reproducible results. The results were averaged and used to calculate the LD50 value, using the method of Reed and Muench (1938), and estimate the minimum acute dose and maximum chronic dose.

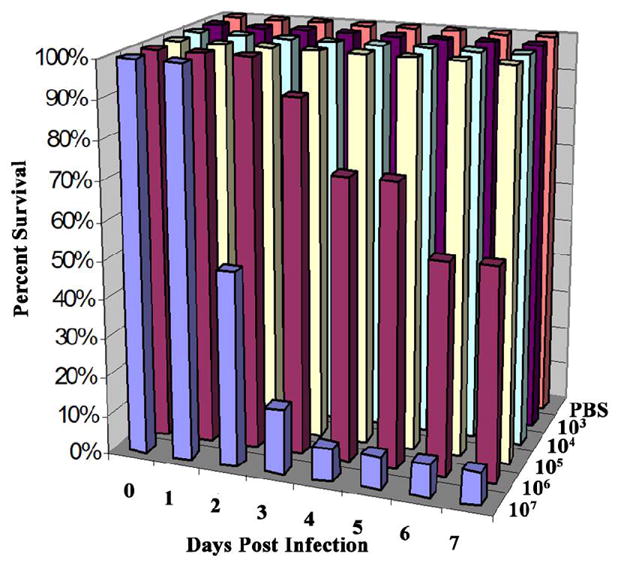

Fig 1.

Establishing chronic and acute doses of M. marinum in medaka. Survival of medaka infected with differing doses of M. marinum by intraperitoneal injection. Fish were injected with 103–107 cfu M. marinum/fish. Control fish were injected with PBS. Twelve fish were used per dose. The above graph represents one of three experiments performed, each of which yielded similar results. The LD50 was calculated to be 2.6 × 106 cfu/fish and the maximum chronic dose was approximately 105 cfu/fish.

2.4 Zebrafish inoculation with M. marinum

Zebrafish were infected with M. marinum doses ranging from 104 to 106 cfu/fish, as described above for medaka dose-response experiments. As with medaka, PBS was injected in the “sham” control. Survival, gross behavior, and mortality were observed until eight weeks post-infection. The experiment was conducted twice, with highly reproducible dose responses. The results were averaged and used to calculate the LD50 value, using the method of Reed and Muench (1938), and estimate the minimum acute dose and maximum chronic dose.

2.5 Plating for viable counts of Gfp-expressing M. marinum in infected organs

To determine viable counts of Gfp-expressing M. marinum in infected organs, livers and kidneys were removed from infected medaka at 2-week intervals from 2 to 8 weeks post-infection. Organs were weighed and then homogenized in 0.5 mL PBS. Appropriate serial dilutions were plated onto BHI agar plates supplemented with kanamycin (80 μg/mL) and cycloheximide (100 μg/mL). Plates were incubated at 30°C for 7–12 days before counting kanamycin resistant, Gfp-expressing colonies.

2.6 Histopathology

Medaka infected with 104 cfu M. marinum/fish were collected for histology at 2-week intervals from 2 to 14 weeks post-infection and also at 20 and 24 weeks post-infection. Fish were sacrificed following an overdose of MS-222 (0.1%). A single anterior to posterior incision along the abdomen of the fish was done to allow for penetration of the fixative. Fish were fixed in Bouin’s fixative for 2 days and then transferred to 10% neutral buffered formalin until further processing.

Medaka were processed for paraffin embedding and stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain or Ziehl-Neelsen’s acid-fast stain using standard techniques. Sections were evaluated for inflammation and granuloma formation, as well as the presence of acid-fast bacilli.

Zebrafish infected with 104 cfu M. marinum/fish were collected at 2 to 8 weeks post-infection and were fixed and prepared for histology as stated above for medaka. Hematoxylin and eosin stains were conducted, but Ziehl-Neelsen’s acid-fast staining was not carried out. Instead, infection was confirmed by observing Gfp expression within fresh organs.

2.7 Monitoring bacterial colonization by fluorescent microscopy

Microscopic inspection of whole fresh organs was performed using: (1) a NikonSMZ800 (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) Stereoscopic Microscope equipped with X-Cite™ 120 for fluorescence illumination and a filter for detection of Gfp, and (2) an epifluorescence compound microscope fitted with a K2 SBIO accessory unit (Technical Instrument Company, San Francisco, CA), allowing for confocal microscopy; and using 10X SPlan Apochromat Olympus (N.A. = 0.3) and 30X Achromat water immersion LOMO (N.A. = 0.9) objectives. Organs were evaluated for the presence of dispersed bacilli expressing Gfp and aggregates of fluorescing bacteria; infection was confirmed by plating for colony counts of Gfp-expressing M. marinum (see above).

Live ST medaka infected with M. marinum expressing Gfp were anesthetized with MS-222 (0.01%) prior to observation under the stereoscopic microscope. Fish infected with 104 cfu/fish were inspected at 2-week intervals from 2 to 6 weeks post-infection.

3. Results

3.1 M. marinum establishes an acute or chronic infection in medaka in a dose-dependent manner

We wished to evaluate the suitability of medaka to study chronic mycobacteriosis with a known strain of M. marinum under defined conditions. To initiate these studies, we first established controlled infection conditions based on the goldfish model (Talaat et. al., 1998) in which known doses of an established pathogenic strain of M. marinum were administered by intraperitoneal injection. Fish were infected by a range of doses (103–107 cfu/fish) and their survival was monitored over time. The maximum chronic dose was determined to be approximately 105 cfu/fish and the LD50 was about 106 cfu/fish, while 107 cfu/fish caused acute disease with >90% mortality at one week post-infection (Fig. 1). The LD50 value was in turn calculated to be 2.6 × 106 cfu/fish. During the course of chronic infection by ≤ 105 cfu/fish, the animals showed no gross signs of disease (Fig. 2). In contrast to the ulcerative skin lesions documented to occur in zebrafish and striped bass (Morone saxatilis) infected with Mycobacterium spp., neither inflammatory lesions nor any gross signs of inflammation were observed in medaka, at any time during infection (Fig. 2) (Rhodes et. al., 2001; Van der Sar et. al., 2004). The behavior of infected fish was judged to be normal; they remained active, continued to eat and lay eggs like the unexposed control group. At 8 weeks post-infection the average survival of two experiments for fish injected with 106, 105, 104, 103 cfu/fish and the PBS control, was 17%, 83%, 73%, 95%, and 87%, respectively. Further, 3 fish infected with 104 cfu/fish were spared and held out to 24 weeks post-infection; they appeared normal and expression of Gfp was observed in various organs of these fish. On various subsequent experiments, numerous fish infected with either 104 or 105 cfu/fish have been held out to 24 weeks post-infection or longer and were found infected but, again, appeared normal. M. marinum expressing Gfp was recovered from the livers and kidneys of all of the experimentally infected medaka sampled. Generally, fish infected with doses of 104 or 105 cfu/fish had recoveries of 103–105 cfu/mg kidney or liver tissue between 2 and 8 weeks post-infection (data not shown). We conclude that these experimental infections of medaka by M. marinum establish a true chronic state of infection.

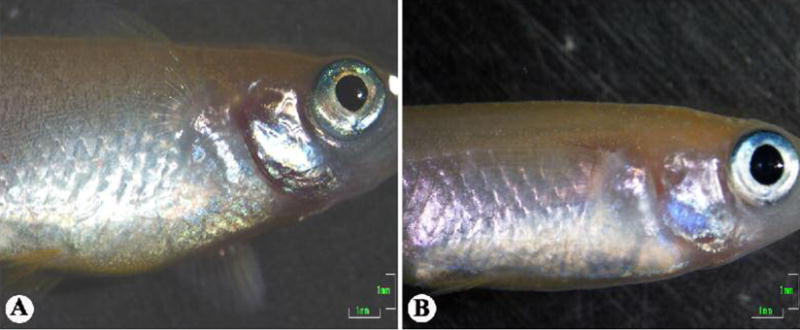

Fig 2.

Gross inspection of medaka post-infection. (A) Negative-control medaka at eight weeks post-injection with PBS showing no gross signs of disease. (B) Medaka injected with 104 cfu M. marinum/fish at eight weeks post-infection, also absent of gross signs of disease. Scale bars: 1 mm.

3.2 Histopathology of M. marinum infection in medaka

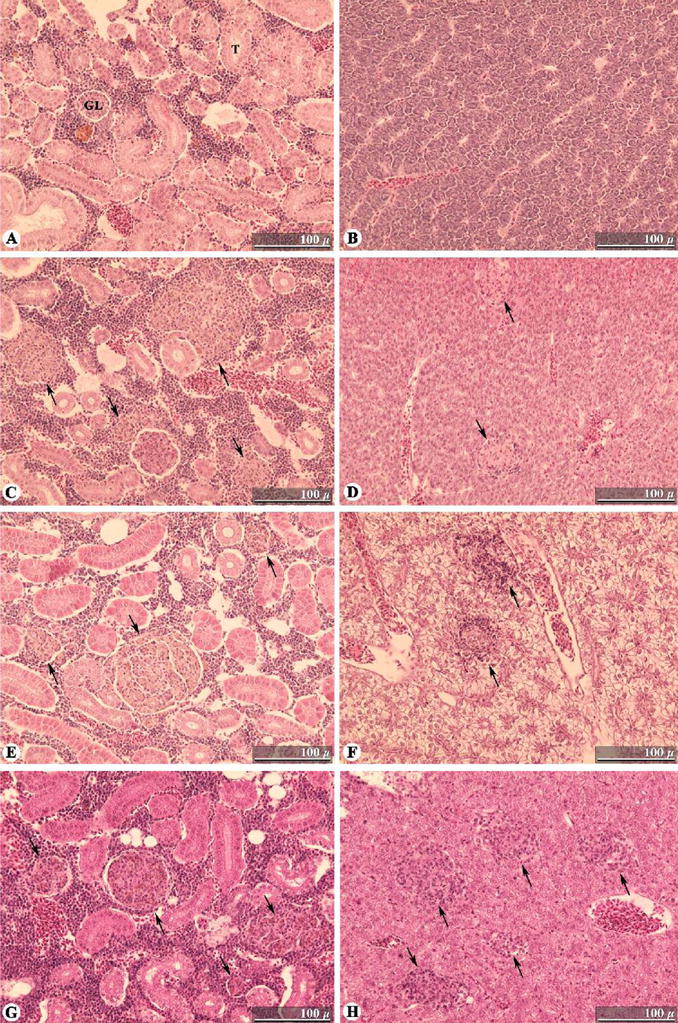

Control fish at all time points showed no signs of mycobacteriosis, lacking granulomatous lesions and acid-fast bacilli (Fig. 3A,B, and data not shown). Infected fish showed little sign of disease at two weeks post-infection, with only larger-than-normal melano-macrophage centers in the kidney. The first early granulomas were seen at 4 weeks post-infection within the anterior kidney, although the posterior kidney was not visible in the sections that were examined. At 6 weeks post-infection, a large increase in the number and organization of granulomas was apparent in the kidney, along with the first signs of early granuloma formation in the liver (Fig. 3C,D). When the spleen was present in a section, it was highly infiltrated by inflammatory cells. Granulomas were not observed in the ovaries or testes. As shown in Fig. 3E and F, the number and structural organization of granulomas in the kidney and liver seemed to progress further at 8 weeks post-infection. After this point, granuloma formation in the kidney and liver seems to progress slowly until 24 weeks post-infection, the last time point examined. At 24 weeks post-infection, many highly organized granulomas are found in the kidney and in the liver (Fig. 3G,H). Acid-fast bacilli were observed within granulomas and surrounding tissues at all time points, although they were few in number (data not shown). These observations are consistent with a state of chronic infection. Inoculation with M. marinum resulted in the slow, but steady, accumulation of highly organized granulomas in kidneys and livers without severe inflammation.

Fig. 3.

Time-course of M. marinum infections in medaka target organs. Histopathology was conducted on fixed sections of medaka that were experimentally infected with 104 cfu M. marinum/fish. (A) Control/uninfected kidney. (B) Control/uninfected liver. (C) Kidney at 6 weeks post-infection showing granuloma formation typical at this stage. (D) Liver at 6 weeks post-infection showing the early formation of two granulomas; the first time point at which granulomas are observed in the liver. (E) Highly structured granuloma and two small granulomas in the kidney at 8 weeks post-infection. (F) Infected liver at 8 weeks post-infection, showing progression of granuloma organization. (G) Kidney at 24 weeks post-infection showing typical well-organized granulomas. (H) Liver at 24 weeks post-infection with numerous organized granulomas. Hematoxylin and eosin stain used in all sections pictured. Scale bars: 100 μm. Granulomas are indicated by arrows. GL, glomerulus; T, renal tubule.

3.3 Detection of Gfp-expressing M. marinum within fresh medaka organs

Consistent with the histology, a steady progression of colonization in kidneys and livers by M. marinum was observed through fluorescent microscopy of fresh organs (Fig. 4). At 2 weeks post-infection, few small foci of fluorescing bacteria were observed with an epifluorescent dissection microscope in both organs (Fig. 4A). This is supported by observations under compound epifluorescent microscopy of only small numbers of Gfp-expressing bacilli throughout both organs. At 4 and 6 weeks post-infection, a substantial increase in the number of fluorescing aggregates of bacteria was observed for both the livers and kidneys (Fig. 4B,C). It is also at this time that spherical aggregates of Gfp-expressing bacilli can be observed in livers and kidneys under compound microscopy (Fig. 4D). The spherical shape of the aggregates was confirmed by confocal microscopy and the aggregates are estimated to range in size of about 40–80 μm. We noted that the diameter of the spheres not only matches that of granulomas observed in histological sections, but their appearance also corresponds with the time-course that granulomas appeared post-infection in histological sections. At 24 weeks post-infection, macroscopic inspection of livers and kidneys revealed gross signs of granulomas, which were found to fluoresce intensely under fluorescent microscopy (Fig. 4E,F). When comparing the number of Gfp-expressing bacilli and acid-fast bacilli, greater numbers of Gfp-expressing bacilli were apparent in tissues compared to acid-fast bacilli in histological sections of tissues at the same time point.

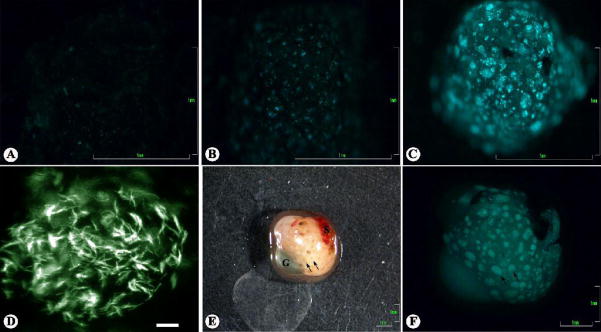

Fig. 4.

Monitoring time-course of M. marinum colonization of medaka by fluorescent microscopy. Fresh tissues from medaka infected with 104 cfu/fish M. marinum expressing Gfp were examined for fluorescence. (A–C) Progressive colonization of medaka kidney tissue by M. marinum shown by Gfp expression under low resolution epifluorescence at (A), 2 wks.; (B), 4 wks.; and (C), 6 wks. post-infection. (D) Spherical aggregate of Gfp expressing bacilli in a kidney at 6 weeks post-infection shown under epifluorescence; the spherical shape of aggregates such as this one was confirmed by confocal microscopy. (E) Liver (with attached spleen (S) and gallbladder (G)) from medaka at 24 weeks post-infection shown in brightfield; notice the gross signs of granulomatous sites of infection in the liver and spleen. (F) Same as (E) at a higher magnification under epifluorescence. Granulomatous lesions observed in (E) fluoresce brightly in the liver, but fluorescence in the spleen is not apparent; this is the typical observation. Scale bars: (A–C,E,F), 1 mm; (D), 10 μm. (D) was imaged with a black and white camera, then color was reapplied with Adobe® Photoshop® to match original fluorescence observed. Arrows indicate positions of representative granulomas. G, gallbladder; S, spleen.

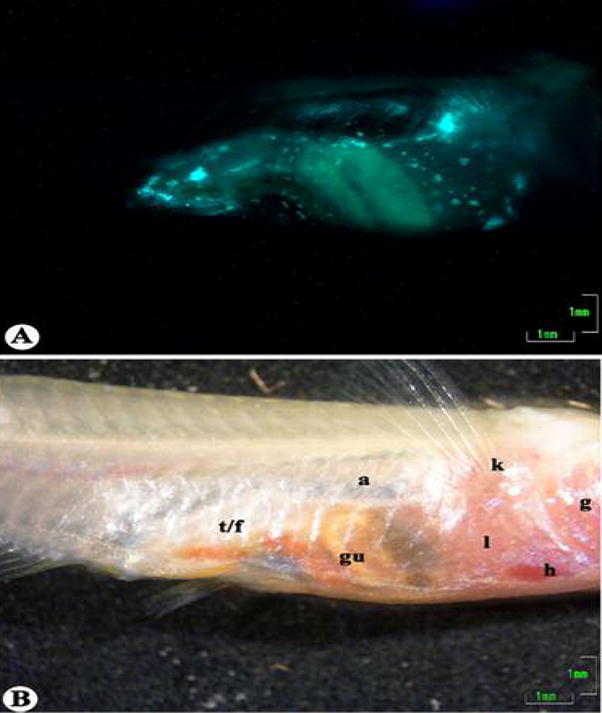

3.4 Colonization of See-Through medaka by M. marinum expressing Gfp

Early attempts to infect ST medaka with doses of 105 cfu M. marinum/fish resulted in acute infection. Because it seemed that ST medaka may be more susceptible, doses of 104 cfu/fish or lower were used in subsequent infections and resulted in a chronic state of disease. This permitted real-time monitoring of the disease progression in live animals. Infections were observed to spread from the point of injection to the kidneys at 2 to 4 weeks post-infection. Colonization of the liver and spleen was observed at 4 to 6 weeks post-infection (Fig. 5). The timing of colonization of the targeted organs is in agreement with that observed in both histological examination and observation of whole infected organs under fluorescent microscopy. Colonization of regions other than known target organs was apparent in ST medaka. Fluorescence was observed in regions believed to include the swim bladder and peritoneal lining. This was not observed in histological sections probably because tissues from these regions were not adequately represented in sections which were prepared.

Fig. 5.

See-Through medaka infected with 104 cfu/fish M. marinum expressing Gfp at 6 weeks post-infection. (A) Fluorescent image showing colonization of various organs with M. marinum expressing Gfp. (B) The same fish shown in brightfield. Locations of organs are indicated as follows: a, air bladder; g, gills; gu, gut; h, heart; k, kidney; l, liver; t/f, testis/fat. Scale bars: 1 mm.

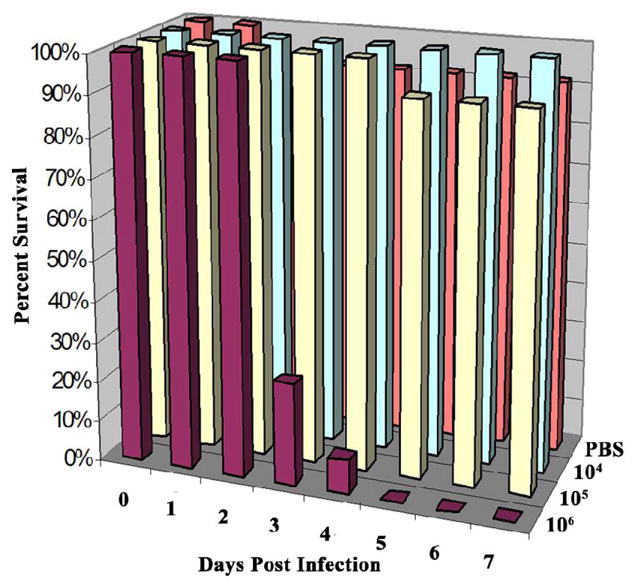

3.5 Zebrafish are more susceptible than medaka to M. marinum infection

In zebrafish experimentally infected with M. marinum under the same conditions as described for medaka, the maximum chronic dose was determined to be approximately 104 cfu/fish. The LD50 was 1.9 × 105 cfu/fish, with an acute response at 106 cfu/fish (Fig. 6). By each of these criteria, zebrafish are judged to be about 10-fold more susceptible to M. marinum infection than medaka under these experimental conditions.

Fig. 6.

Establishing chronic and acute doses of M. marinum in zebrafish. Survival of zebrafish infected with differing doses of M. marinum by intraperitoneal injection. Fish were injected with 104–106 cfu M. marinum/fish. Control fish were injected with PBS. Twelve fish were used per dose and colors for each dose correspond to Fig. 1. The above graph represents one of two experiments performed, both of which yielded similar results. The LD50 was calculated to be 1.9 × 105 cfu/fish and the maximum chronic dose was approximately 104cfu/fish.

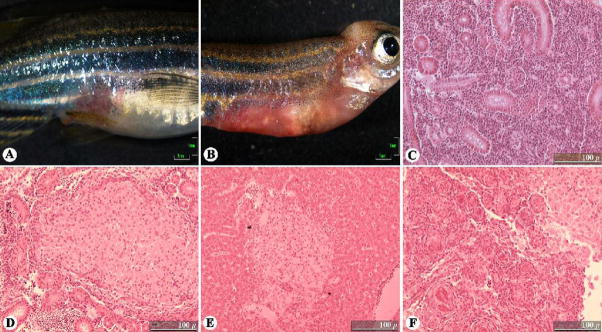

At a gross level of observation, behavior, such as swimming and eating, were not affected for zebrafish infected with a chronic dose (i.e., 104 cfu/fish). However, ulcerative lesions were observed on the abdominal region of all fish infected, even with a chronic dose. The observed lesions were at the site of injection, as well as other regions of the abdomen (Fig. 7A). These lesions progressed in number and severity out to 8 weeks post-infection. Individuals infected with an acute dose showed reddening of the abdomen by 24 hours post-injection and had inflammation in the cranial region prior to death (Fig. 7B). This contrasts with observations of medaka infected with M. marinum, which never showed any external signs of inflammatory lesions or inflammation of any type.

Fig. 7.

Zebrafish mycobacteriosis. (A) Typical ulcerative lesion observed on the surface of a zebrafish infected with 104 cfu M. marinum/fish at 2 weeks post-infection. (B) Zebrafish infected with 106 cfu M. marinum/fish at moribund, showing reddening of the abdomen and swelling of the cranium. (C) Control kidney showing normal tissue architecture. (D) Kidney at 8 weeks post-infection showing typical inflammation. (E) Liver at 8 weeks post-infection showing typical large area of inflammation with some organization suggestive of granuloma formation. (F) Liver showing numerous “onion peal” granulomas, which were only observed in one individual, and such granulomas were found throughout the viscera. Hematoxylin and eosin stain used for (C–F). Scale bars: (A,B), 1 mm; (C–F), 100 μm.

All infected zebrafish that were sampled showed Gfp expression in the visceral cavity and organs, while no Gfp expression was seen in negative-control fish (data not shown). Histological examination revealed that, as early as 4 weeks post-infection, large granulomas and progressive inflammation can be observed in the kidney, liver, and visceral cavity. This inflammation was observed to constitute up to one-half the area of livers and kidneys at this time point. Granulomas and inflammation were also observed in the testes and ovaries of zebrafish. The state of inflammation continued to progress from 6 weeks to 8 weeks post-infection, with formation of highly organized granulomas and diffuse inflammation taking place in various regions of the liver, kidney and the visceral cavity (Fig. 7C–F). In one individual sampled at 8 weeks post-infection, highly organized “onion ring” granulomas were observed throughout the viscera of the fish (Fig. 7F). This type of granuloma is histologically similar to some human tuberculosis cases (Nambuya et. al., 1988; Pozos and Ramakrishnan, 2004). In all other individuals sampled, only diffuse inflammatory lesions and large granulomas lacking the “onion ring” morphology were present.

4. Discussion

A major goal of this project was to evaluate the utility of M. marinum and medaka to model human tuberculosis. Although we have learned of possible infections of medaka colonies by M. marinum, no published accounts, that we are aware of, exist for M. marinum infection in medaka. However, mycobacteriosis in medaka and other laboratory fish has been documented in numerous publications (Abner et. al., 1994; Teska et. al., 1997; Sanders and Swaim, 2001; Kent et. al., 2004; Watral and Kent, 2006). Monitoring for the presence of mycobacteria in populations of fish has proven to be difficult, and the potential for low-level background infections is a common risk-factor, especially in large research facilities. Unforeseen mycobacterial infections of animals may complicate and confound research involving infected animals. For this reason, better characterization of mycobacteriosis in fish is of importance as small fish models are more widely used for research purposes.

Three replicates of the dose-response experiment were performed and yielded essentially the same results, indicating that this medaka-M. marinum infection model is highly reproducible. The true chronic nature of the infection was demonstrated by infected fish surviving and appearing healthy out to 24 weeks post-infection and by recovery of Gfp-expressing M. marinum from all fish sampled. An immunologic manifestation typical of mycobacteriosis was demonstrated through histopathological examination of the entire fish. Slow but progressive granuloma formation in the liver and kidney, as well as inflammation of the spleen, were observed.

The risks of background mycobacterial infections in the medaka population used is reduced due to the precautions taken in our animal husbandry practices. Further, our inspections of bacteria from control fish and routine inspection of our medaka colony during these experiments did not reveal any bacterial colonies matching the morphology of Mycobacterium species. Also, granuloma formation was not observed in sampled control fish.

Granulomas were shown to occur in kidney tissue at an earlier time point post-infection compared to liver. Earlier onset of granulomas in kidneys may be due to the role that the anterior kidney plays as the primary hematopoietic organ in teleosts. The anterior kidney of teleost fish is structurally analogous to mammalian bone marrow and contains monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils and lymphocytes (Zapata, 1979; Moore and Hawke, 2004). In medaka, the kidney contains many melano-macrophage centers, while in the liver such structures are unusual. The roles of melano-macrophage centers is thought to include humoral and inflammatory immune responses, storage and destruction of endogenous and exogenous agents, and iron recycling (Wolke, 1992). The fact that such aggregates of macrophage cells exist in kidneys and not in liver tissues prior to infection may account for the early colonization and immune response in kidneys compared to livers. We speculate that M. marinum may be trafficked by macrophages to the kidney prior to the liver.

Our ability to use Gfp as a reporter for observing M. marinum in fresh tissues proved to be a fast and convenient means to detect the spread to and colonization of host target organs. In situ monitoring of fluorescent bacteria in the See-Through (ST) medaka also permitted us to conveniently document over time, the infectious loads of target organs and where bacteria were sheltered at different stages of disease in the living animal. The colonization sequence and the temporal disease progression in the ST animals was very close to what we observed by other methods. The sensitivity and numbers of bacteria observed in tissues through the use of Gfp was far greater than by acid-fast staining. We presume that the difference in sensitivity likely reflects well documented underrepresentation of stained bacilli embedded in fixed tissues using common acid-fast staining techniques (Nyka, 1967, 1974).

We chose 28°C to conduct our infections because it is within the optimum temperature range for M. marinum (28–30°C), a temperature that is also ideal for medaka growth. In order to directly compare the infection process between both medaka and zebrafish, all conditions, including temperature, were the same. Zebrafish under these controlled conditions with known doses of M. marinum were significantly more susceptible than medaka. This was demonstrated by a ten-fold lower maximum chronic dose, LD50, and acute dose for zebrafish. Moreover, inflammation of the entire visceral cavity, including most organs, progressed more rapidly in zebrafish and appeared more severe than in medaka. Medaka infections resulted in a number of well organized granulomas, mainly in the liver and kidney. Discrete foci of infection were apparent, and did not result in progressive spread and inflammation of the entire organ. In contrast, zebrafish infections almost always resulted in progressive inflammation occupying almost the entire organ by 8 weeks post-infection. Zebrafish also demonstrated external signs of infection through the appearance of ulcerative lesions in the abdominal region of all infected fish. Acutely-infected zebrafish presented inflammation of the cranial region and reddening of the abdomen. Chronically-infected medaka were very different, never exhibiting abnormal behavior nor presenting any external signs of disease; indeed, they were indistinguishable from the uninfected medaka. Acutely infected medaka ate less than normal and stayed at the bottom of the aquaria, but showed no external lesions nor gross signs of inflammation before succumbing.

When comparing our results in zebrafish with previously reported studies (Prouty et. al., 2003), some differences were noted; in particular, previously reported infections appeared milder. From the published data, we estimate the LD50 at one week post-infection for zebrafish lies between 106 and 107 cfu/fish. This was at least ten-fold higher than the LD50 of 1.9 × 105 cfu/fish that we determined. Their maximum chronic dose of about 105 cfu/fish was also about ten-fold higher. The previously published infections were conducted at room temperature, which was estimated to be at or below 25°C (K. Klose, University of Texas at San Antonio; personal communication), and the lower temperatures may account for the reduced susceptibilities. This explanation seems plausible since 25°C is below the optimal growth temperature for the bacterium. These differences in susceptibilities of zebrafish in the previous study and in our work cannot be explained by differences in M. marinum strains, since, in both cases, the same strain was used. Alternatively, the strain of zebrafish used may have been different but was not identified in the previous study (Prouty et. al., 2003). Reduction in virulence by conducting experiments at temperatures below the pathogen’s optimum temperature is also consistent with our preliminary infection studies with medaka (data not shown). These observations, in turn, suggest that propagating fish at lower temperatures might be a simple means to reduce disease complications associated with chronic mycobacteriosis in fish colonies.

The research group headed by Ramakrishnan has used M. marinum expressing Gfpto pioneer the innate immune response of zebrafish embryos (Davis et. al., 2002; Volkman et. al., 2004). These elegant studies documented the trafficking of M. marinum within macrophages of infected embryos in real time (Davis et. al., 2002) and examined the effects of virulence factors on granuloma formation (Volkman et. al., 2004). Monitoring pathogenesis by following these fluorescing bacteria within zebrafish embryos has been facilitated by the embryo’s lack of pigment at early stages of development. One disadvantage of this zebrafish system is that during development the embryos and larva progressively develop pigment obscuring the fluorescent bacteria. We anticipate complementing this research on embryos by using See-Through medaka (Wakamatsu et. al., 2001) to monitor real time disease progression, in adult animals with mature immune responses. Our initial infections on ST adults have also demonstrated the feasibility of detecting where bacteria are sheltered at different stages of the disease including outside the targeted organs.

Trucksis and coworkers have used goldfish as a host to identify M. marinum virulence factors using signature-tagged mutagenesis (Ruley et. al., 2004). Because, the goldfish model, as well as the leopard frog model, are not highly tractable genetic models, those hosts will not likely be useful in elucidating host factors that play roles in infection. Medaka and zebrafish are not only more convenient to maintain and propagate, but the availability of their excellent classic genetics and molecular genetic technologies offers the promise of a detailed understanding of host-pathogen interactions. We expect that medaka and zebrafish models each offer important, but different advantages in studying mycobacterial infections. Specifically, the zebrafish model may offer better insights into acute mycobacteriosis, while the medaka model may be better suited for studying life-long chronic infections. We anticipate that these highly tractable fish hosts and pathogen models will offer important insights into human tuberculosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Lucia Barker, University of Minnesota Medical School, Dr. Lalita Ramakrishnan, University of Washington, and Dr. Graham Hatfull, University of Pittsburgh, for providing M. marinum strains and plasmid constructs; Dr. Richard Winn, University of Georgia, for providing the orange-red variety of medaka; Dr. Yuko Wakamatsu, Nagoya University, for providing the See-Through medaka, Dr. David Hinton, Duke University, for assistance in raising the See-Through fish; and Dr. Monte Westerfield, University of Oregon, for providing the zebrafish. We are grateful to Dr. William Hawkins and Rena Krol, Gulf Coast Research Laboratory, University of Southern Mississippi, for their assistance with histological preparation of medaka; Dr. Michael Kent, Oregon State University, for his assistance with histological preparation of zebrafish; Dr. Glen Watson, University of Louisiana, for the use of his microscopes and discussion of fluorescent microscopy; and Dr. Suzanne Fredericq for the use of her microscope. We would like to thank Dr. John Hawke, Louisiana State University, and Nadine Mutoji, University of Louisiana, for proofreading and discussion of the paper. We would also like to acknowledge the following undergraduates who assisted with various aspects of this project: Laura Durling, Loni Guidry, Analise Zaunbrecher, and Laura Zaunbrecher. This work was supported by Louisiana Board of Regents Research and Development Grant (RD01-A-38) and NIH grant (5R21AI055964-01) to DGE, Louisiana Graduate Fellowship award also travel and supply funds by the University of Louisiana Graduate Student Organization and NSF travel awards to the Wind River Conference on Prokaryotic Biology to GWB.

Footnotes

This paper is based on a presentation given at the conference: Aquatic Animal Models of Human Disease hosted by the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia, USA, October 30 – November 2, 2005.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abner SR, Frazier CL, Scheibe JS, Krol RA, Overstreet RM, Walker WW, Hawkins WE. Chronic inflammatory lesions in two small fish species, Medaka (Oryzias latipes) and Guppy (Poecilia reticulata), used in carcinogenesis bioassays. In: Stolen JS, Fletcher TC, editors. Modulators of Fish Immune Responses: Models for Environmental Toxicology, Biomarkers, and Immunostimulators. SOS Publications; Fair Haven, NJ, USA: 1994. pp. 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Amores A, Force A, Yan YL, Joly L, Amemiya C, Fritz A, Ho RK, Langeland J, Prince V, Wang YL, Westerfield M, Ekker M, Postlethwait JH. Zebrafish hox clusters and vertebrate genome evolution. Science. 1998;282:1711–1714. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsterdam A, Burgess S, Golling G, Chen W, Sun Z, Townsend K, Farrington S, Haldi M, Hopkins N. A large-scale insertional mutagenesis screen in zebrafish. Genes and Development. 1999;13:2713–2724. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker LP, Porcella SF, Wyatt RG, Small PLC. The Mycobacterium marinum G13 promoter is a strong sigma 70-like promoter that is expressed in Escherichia coli and mycobacteria species. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 1999;175:79–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosma CL, Sherman DR, Ramakrishnan L. The secret lives of the pathogenic mycobacteria. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2003;57:641–676. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.091033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JM, Clay H, Lewis JL, Ghori N, Herbomel P, Ramakrishnan L. Real-time visualization of Mycobacterium-macrophage interactions leading to initiation of granuloma formation in zebrafish embryos. Immunity. 2002;17:693–702. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decostere A, Hermans K, Haesebrouck F. Piscine mycobacteriosis: a literature review covering the agent and the disease it causes in fish and humans. Veterinary Microbiology. 2004;99:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, Pathania V, Raviglione MC. Consensus statement. Global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. WHO Global Surveillance and Monitoring Project. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:677–686. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine PEM. Variation in protection by BCG: implications of and for heterologous immunity. Lancet. 1995;346:1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank AA, Orme IM. Granuloma formation in mouse and guinea pig models of experimental tuberculosis. In: Boros DL, editor. Granulomatous infections and inflammations: cellular and molecular mechanisms. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2003. pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa Y. Medaka fish as a model system for vertebrate developmental genetics. BioEssays. 2000;22:487–495. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200005)22:5<487::AID-BIES11>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs WR, Tuckman M, Bloom BR. Introduction of foreign DNA into mycobacteria using a shuttle phasmid. Nature. 1987;327:532–535. doi: 10.1038/327532a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent ML, Whipps CM, Matthews JL, Florio D, Watral V, Bishop-Stewart JK, Poort M, Bermudez L. Mycobacteriosis in zebrafish (Danio rerio) research facilities. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology C. 2004;138:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Pascopella L, Jacobs WR, Hatfull GF. Site-specific integration of mycobacteriophage L5: integration-proficient vectors for Mycobacterium smegmatis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and bacille Calmette-Guérin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1991;88:3111–3115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MM, Hawke JP. Immunology. In: Tucker CS, Hargreaves JA, editors. Biology and Culture of Channel Catfish. Elsevier Science Publishers; Amsterdam: 2004. pp. 349–386. [Google Scholar]

- Nambuya A, Sewankambo N, Mugerwa J, Goodgame R, Lucas S. Tuberculous lymphadenitis associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in Uganda. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1988;41:93–96. doi: 10.1136/jcp.41.1.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naruse K, Tanaka M, Mita K, Shima A, Postlethwait J, Mitani H. A medaka gene map: the trace of ancestral vertebrate proto-chromosomes revealed by comparative gene mapping. Genome Research. 2004;14:820–828. doi: 10.1101/gr.2004004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyka W. Method for staining both acid-fast and chromophobic tubercule bacilli with carbolfuchsin. Journal of Bacteriology. 1967;93:1458–1460. doi: 10.1128/jb.93.4.1458-1460.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyka W. Studies on the effect of starvation on mycobacteria. Infection and Immunity. 1974;9:843–850. doi: 10.1128/iai.9.5.843-850.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnighaus JM, Fine PEM, Sterne JAC, Wilson RJ, Msosa E, Gruer PJK, Jenkins PA, Lucas SB, Liomba NG, Bliss L. Efficacy of BCG vaccine against leprosy and tuberculosis in northern Malawi. Lancet. 1992;339:636–639. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90794-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozos TC, Ramakrishnan L. New models for the study of Mycobacterium-host interactions. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2004;16:499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prouty MG, Correa NE, Barker LP, Jagadeeswaran P, Klose KE. Zebrafish-Mycobacterium marinum model for mycobacterial pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2003;225:177–182. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan L, Falkow S. Mycobacterium marinum persists in cultured mammalian cells in a temperature-restricted fashion. Infection and Immunity. 1994;62:3222–3229. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3222-3229.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan L, Valdivia RH, McKerrow J, Falkow S. Mycobacterium marinum causes both long-term subclinical infection and acute disease in the leopard frog (Rana pipiens) Infection and Immunity. 1997;65:767–773. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.767-773.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. American Journal of Hygiene. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes MW, Kator H, Kotob S, van Berkum P, Kaattari I, Vogelbein W, Floyd MM, Butler WR, Quinn FD, Ottinger C, Shotts E. A unique Mycobacterium species isolated from an epizootic of striped bass (Morone saxatilis) Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2001;7:896–899. doi: 10.3201/eid0705.017523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogall T, Wolters J, Flohr T, Bottger E. Towards a phylogeny and definition of species at the molecular level within the genus Mycobacterium. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 1990;40:323–330. doi: 10.1099/00207713-40-4-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruley KM, Ansede JH, Pritchette CL, Talaat AM, Reimschuessel R, Trucksis M. Identification of Mycobacterium marinum virulence genes using signature-tagged mutagenesis and the goldfish model of mycobacterial pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2004;232:75–81. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(04)00017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders GE, Swaim LW. Atypical piscine mycobacteriosis in Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) Comparative Medicine. 2001;51:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talaat AM, Reimschuessel R, Wasserman SS, Trucksis M. Goldfish, Carassius auratus, a novel animal model for the study of Mycobacterium marinum pathogenesis. Infection and Immunity. 1998;66:2938–2942. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2938-2942.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JS, Braasch I, Frickey T, Meyer A, Van de Peer Y. Genome duplication, a trait shared by 22,000 species of ray-finned fish. Genome Research. 2003;13:382–390. doi: 10.1101/gr.640303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teska JD, Twerdok LE, Beaman J, Curry M, Finch RA. Isolation of Mycobacterium abscessus from Japanese medaka. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health. 1997;9:234–238. [Google Scholar]

- Tønjum T, Welty DB, Jantzen E, Small PL. Differentiation of Mycobacterium ulcerans, M. marinum, and M. haemophilum: mapping of their relationships to M. tuberculosis by fatty acid profile analysis, DNA-DNA hybridization, and 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1998;36:918–925. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.918-925.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Sar AM, Appelmelk BJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CMJE, Bitter W. A star with stripes: zebrafish as an infection model. Trends in Microbiology. 2004;12:451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkman HE, Clay H, Beery D, Chang JCW, Sherman DR, Ramakrishnan L. Tuberculous granuloma formation is enhanced by a Mycobacterium virulence determinant. Plos Biology. 2004;2:1946–1956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamatsu Y, Pristyazhnyuk S, Kinoshita M, Tanaka M, Ozato K. The see-through medaka: a fish model that is transparent throughout life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98:10046–10050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181204298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watral V, Kent ML. Pathogenesis of Mycobacterium spp. in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) from Research Facilities. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology C. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2006.06.004. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn RN, Norris MB, Brayer KJ, Torres C, Muller SL. Detection of mutations in transgenic fish carrying a bacteriophage λcII transgene target. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2000;97:12655–12660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220428097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn RN, Norris M, Muller S, Torres C, Brayer K. Bacteriophage λ and plasmid pUR288 transgenic fish models for detecting in vivo mutations. Marine Biotechnology. 2001;3:S185–S195. doi: 10.1007/s10126-001-0041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittbrodt J, Shima A, Schartl M. Medaka-A model organism from the far east. Nature Reviews. 2002;3:53–64. doi: 10.1038/nrg704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolke RE. Piscine macrophage aggregates: a review. Annual Review of Fish Diseases. 1992;2:91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Woods IG, Kelly PD, Chu F, Ngo-Hazelett P, Yan Y, Huang H, Postlethwait JH, Talbot WS. A comparative map of the zebrafish genome. Genome Research. 2000;10:1903–1914. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.12.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapata A. Ultrastructural study of the teleost fish kidney. Developmental and Comparative Immunology. 1979;3:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(79)80006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]