Abstract

Loss of imprinting (LOI) is the gain of expression from the silent allele of an imprinted gene normally expressed from only one parental copy. LOI has been associated with neurodevelopmental disorders and reproductive abnormalities. The mechanisms of imprinting are varied, with DNA methylation representing only one. We have developed a functional transcriptional assay for LOI that is not limited to a single mechanism of imprinting. The method employs allele-specific PCR analysis of RT-PCR products containing common readout polymorphisms. With this method, we are able to measure LOI at the sensitivity of 1%. The method has been applied to measurement of LOI in human placentas. We found that RNA was stable in placentas stored for more than one hour at 4°C following delivery. We analyzed a test panel of 26 genes known to be imprinted in the human genome. We found that 18 genes were expressed in placenta. Fourteen of the 18 expressed genes contained common readout polymorphisms in the transcripts with a minor allele frequency >20%. We found that 5 of the 14 genes were not imprinted in placenta. Using the remaining nine genes, we examined 93 heterozygosities in 27 samples. The range of LOI was 0%–96%. Among the 93 heterozygosities, we found 23 examples (25%) had LOI >3% and eight examples (9%) had LOI 1–3%. Our results indicate that LOI is common in human placentas. Because LOI in placenta is common, it may be an important new biomarker for influences on prenatal epigenetics.

Keywords: loss of imprinting (LOI), readout polymorphism, quantitative allele-specific PCR (qASPCR), human placenta

Introduction

Genomic imprinting refers to silencing of one parental allele in the zygotes of gametes leading to monoallelic expression of these genes in the offspring. This process results in a reversible parent (or gamete)-of-origin specific marking of the genome.1,2 The prevailing hypothesis on the evolution of genomic imprinting is the “tug of war” theory.3 In this theory, expression of paternal alleles would promote placental growth to enhance the reproductive success of the paternal lineage while the maternally expressed alleles would counter-balance the paternal genes to avoid depletion of nutritional resources. To date, about 60 genes have been shown to be imprinted in humans, two thirds of which are paternally expressed (maternally imprinted) and one third maternally expressed (paternally imprinted).4 A recent report using an in silico approach identified an additional ~150 potentially imprinted genes in the human genome.5 Perturbations of monoallelic expression, i.e., loss of imprinting (LOI), result in gain of expression from the silenced allele. In this manuscript, we present LOI values based on complete silencing of the imprinted allele. For some genes, the silenced allele will exhibit “leaky expression”6 which may depend on gestational age.7 Pathological LOI levels have been linked to a wide range of human diseases including reproductive abnormalities,8–10 neurodevelopmental disorders, and cancer.11,12

The conventional quantitative method for measuring LOI targets loss of DNA methylation using bisulfite treatment followed by quantitative PCR to determine the relative abundance of methylated and unmethylated alleles.13,14 One limitation of this assay lies in the fact that other epigenetic mechanisms regulating imprinting, such as histone methylation or acetylation, are not accounted for. Another limitation is that this method measures LOI as deviation from 50:50 in the C:T content at the site of the imprinting methylation, limiting the sensitivity of the assay.

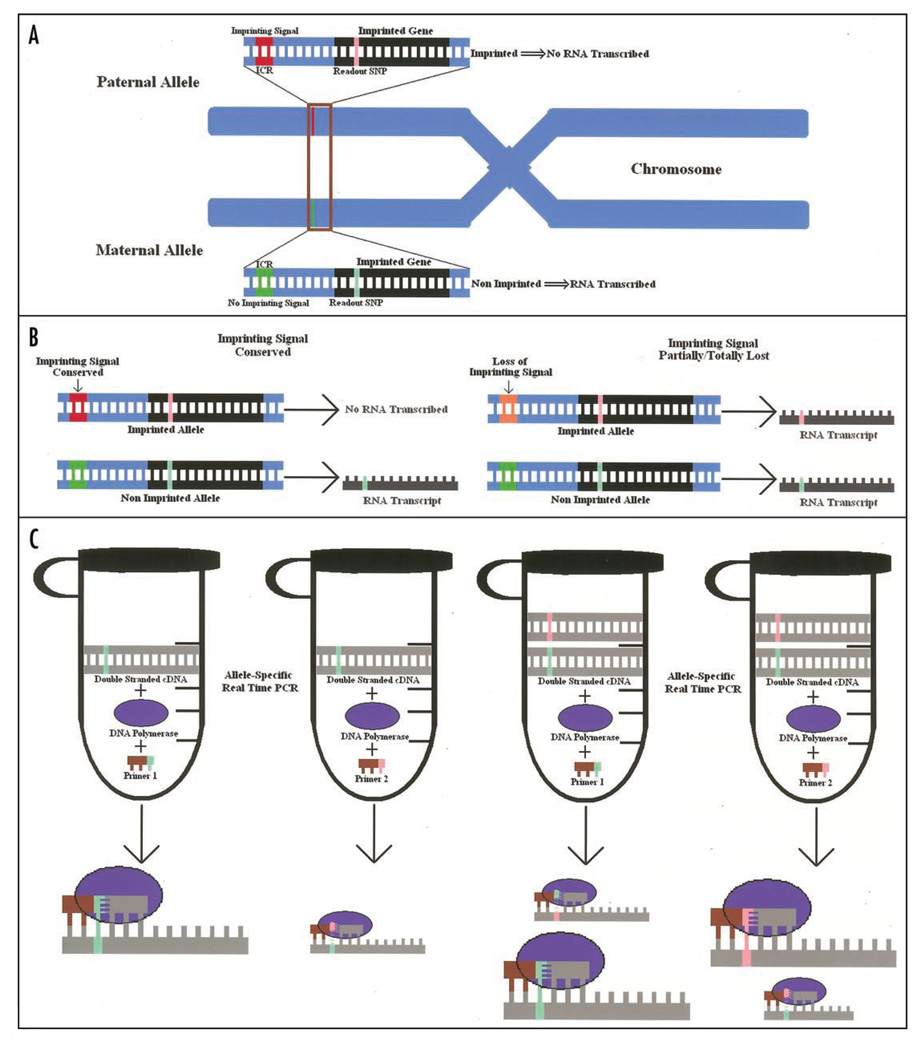

Herein, we describe a highly sensitive and functional assay for measuring LOI using quantitative allele-specific PCR (qASPCR) on reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) products containing a readout polymorphism (Fig. 1). This mRNA-based assay is independent of the mechanism of imprinting, making it more biologically relevant. The testing of the differential allelic mRNA expression requires a reporter marker such as a readout single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) that can return a measure of the level of activation of the silenced allele. In such a system, the relative expression can be evaluated only when the marker SNP is heterozygous, thus allowing the identification of the product of each allele. The success of the LOI assay depends on the ability to accurately measure allele frequency in a mixed population. In our previous work, we have demonstrated that allele-specific PCR was robust for determining allele frequencies in pooled DNA samples.15 With this method, we are able to measure LOI with the sensitivity of ~1%. As with other epigenetic processes, genomic imprinting is tissue specific16 and thus should be studied in the context of the target tissues. Because of our research interest in diseases of placentation (e.g., pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, intra-uterine growth restriction, gestational diabetes), we developed the LOI assay using the human placenta as a model system. The method described here could easily be adapted to other tissue types.

Figure 1.

LOI quantification approach. (A) Representation of a paternally imprinted/maternally expressed gene. The paternal allele is not expressed because of the imprinting control region (ICR)29 imprinting signal (red and green). The gene is heterozygous for a readout SNP located in the transcribed sequence (pink and lime). (B) When the imprinting signal is conserved (left) no mRNA expression is expected from the paternal allele. Therefore, only the mRNA copy carrying one of the two alleles is produced. When the imprinting signal is partially/totally lost (LOI) (right, orange), mRNA from the imprinted allele is produced leading to an mRNA pool containing both alleles. (C) Proportion of mRNA produced by the imprinted de-silenced allele can be quantified after converting the whole mRNA pool into more stable double stranded cDNA through reverse transcription and minimal amplification. Splitting the cDNA template into two equivalent batches and using two separate primer sets with the last base matching one of the two SNP alleles, allows the quantification of the relative amount of the two original mRNA forms. Mismatched primers at the 3' end allow template misextention with a considerably lower efficiency. Real time PCR leads to little amplification from the imprinted allele in the case of conservation of the imprinting signal (left). When the imprinting signal is lost (right), both primers are extended.

Results

There are two main databases listing 64 imprinted genes in humans.17,18 Placental expression was first evaluated by searching the Unigene/NCBI tissue-specific gene expression database19 and the available literature,20,21 and was then verified experimentally. Of the 26 genes we have examined, 18 were found to be expressed in human placenta (Suppl. Table 3). Fourteen of the 18 expressed genes contained common readout SNPs in the transcripts with a minor allele frequency >20%. We found that 5 of the 14 genes were not imprinted in placenta (GNAS1, ATP10A, OSBPL5, PPP1R9A, KCNQ1), although they may be imprinted in other issues.

RNA stability

Because our functional LOI measurements are carried out on mRNA transcripts, we first measured the stability of placental RNA to eliminate differential RNA degradation as a variable. The placental collection system that we elaborated is intended to reduce to the minimum the time between placental availability and tissue freezing in liquid nitrogen. We found that the time between the delivery of the placenta and storage at 4°C and freezing in liquid nitrogen normally averages ~30 minutes. We found no significant total or differential RNA degradation out to 45 minutes additional storage at 4°C in saline (Table 2A).

Table 2.

Placental RNA stability and purity

| (A) RNA stability statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | R2 | Statistics p-value |

β variation (95% CI) |

| ACTB | 0.492 | 0.299 | −2.070–1.058 |

| PEG1/MEST | 0.331 | 0.425 | −2.617–1.634 |

| PEG3/PW1 | 0.467 | 0.317 | −2.460–1.302 |

| GTL2/MEG3 | 0.705 | 0.160 | −2.063–0.672 |

| H19 | 0.481 | 0.307 | −2.620–1.361 |

| GNAS1 | 0.014 | 0.880 | −3.144–2.905 |

| (B) Maternal contamination test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Samplea | DNA level | RNA levelb | ||||

| Allele-specific primer | ΔCt | Allele-specific primer | ΔCt | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| OSBPL5 c | P3 | 29.98 | 24.79 | 5.19 | 30.37 | 20.09 | 10.28 |

| L111 | 29.15 | 23.98 | 5.17 | 29.43 | 19.22 | 10.21 | |

| GNAS1 c | OPN3 | >35.00 | 22.45 | >12.55 | >35.00 | 24.03 | >10.97 |

| L105 | >35.00 | 23.04 | >11.96 | 33.18 | 21.70 | 11.48 | |

| TXK c | OPI1 | -d | 23.04 | -e | -d | 23.57 | -e |

| L103 | -d | 21.28 | -e | -d | 24.52 | -e | |

The human placental RNA stability is described in Materials and Methods. After normalizing against 18S rRNA and calculating a weighted Ct average for three placenta samples, Ct values were plotted in a linear regression model against the natural logarithm of time. No significant decrease in cDNA concentration from the processing time was observed for any of the genes. Moreover, the β values indicating the 95% confidence interval for the slope of the regression curve were centered on "0".

P3, OPN3, OPI1 = placenta samples; L111, L105, L103 = samples from unrelated lymphocyte.

Ct values normalized against 18S rRNA.

OSBPL5:rs3741350—G/A Synonymous; GNAS1:rs7121—C/T 3' UTR; TXK:rs9996527—G/C Synonymous.

No Ct value observed for the mismatched primers.

No ΔCt calculation possible. Ct values from homozygous placenta are compared in an allele-specific test to matching genotypes from unrelated lymphocytes at the DNA and RNA levels.

Loss of imprinting

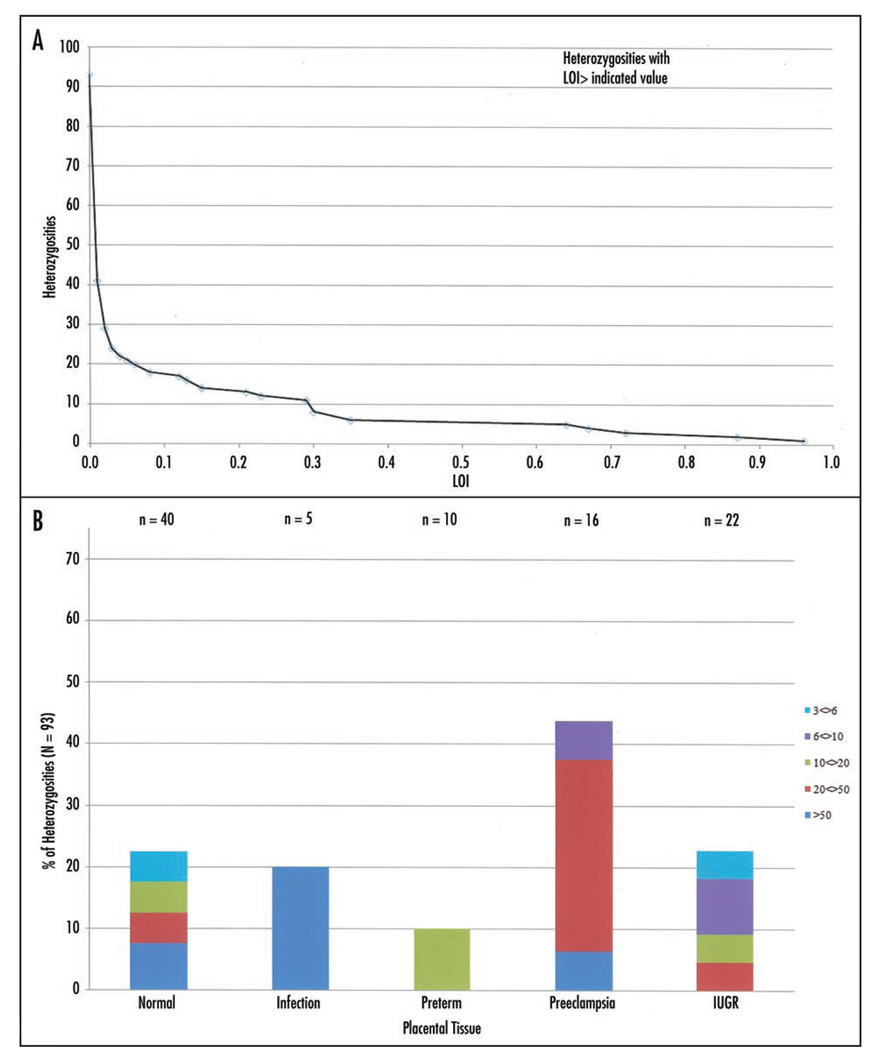

Using the nine imprinted genes with common readout SNPs (Table 1), we examined 93 heterozygosities in 27 placentas. Twelve of the placentas in the study population were from normal deliveries, and 15 were associated with placental abnormalities: two intrauterine infection (IUI), three preterm, three preeclampsia and seven intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). LOI was determined by qASPCR using SNP-containing RT-PCR amplicons as templates and calculated assuming complete silencing of the imprinted allele. A summary of the analyses is presented in Table 3. Sixty-two of 93 heterozygosities showed LOI <1%, demonstrating the power of the technique. All of the nine genes were represented in this fully imprinted class, showing that “leaky expression” did not affect the determination of LOI for the genes selected for this study. Surprisingly, 23 of 93 heterozygosities showed LOI greater than 3%, all of which are significantly different from the fully imprinted values, demonstrating that LOI is a common phenomenon in human placenta. Observed LOI values were independent of the level of expression (p < 0.001). Figure 3A, a plot of all the LOI values as the number of heterozygosities exceeding a particular LOI, shows no bias toward any particular LOI value. Panel B shows the 23 samples with LOI greater than 3% classified by placental pathology and level of LOI.

Table 1.

Imprinted gene set used for LOI analyses

| Gene | Location | Readout SNP | rs# | Allele frequency (%)a |

Homozygote frequency (%)b |

Gene product |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paternally expressed | ||||||

| IGF2 | 11p15.5 | A/G 5' UTR | rs10770125 | 51.7/48.3 | 55.2 | Insulin-like growth factor II |

| PEG1/MEST | 7q32 | G/C 3' UTR | rs1050582 | 40.0/60.0 | 35.5 | Putative hydrolase enzyme |

| PEG3/PW1 | 19q13.4 | A/G Synonymous | rs2286751 | 22.5/77.5 | 71.6 | Kruppel-like transcription factor |

| PEG10 | 7q21.3 | T/C 3' UTR | rs13073 | 28.3/71.7 | 60.0 | Paternally expressed gene 10 |

| ZAC/PLAGL1 | 6q24.2 | C/T 5' UTR | rs9373409 | 50.8/49.2 | 45.0 | Zinc-finger DNA binding protein |

| DLK1 | 14q32.2 | T/C Synonymous | rs1802710 | 44.9/55.1 | 50.0 | Δ-like protein precursor |

| Probability that all SNPs in all genes are homozygous | 1.9 | |||||

| Maternally expressed | ||||||

| GTL2/MEG3 | 14q32 | G/A 3' UTR | rs1054013 | 66.7/33.3 | 56.7 | Gene trap locus 2 |

| H19 | 11p15.5 | T/C 3' UTR | rs2839704 | 56.5/43.5 | 39.1 | Non-coding RNA |

| TP73(b) | 1p36.3 | C/T 3' UTR | rs1181869 | 31.0/69.0 | 57.2 | Tumor protein p73 |

| Probability that all SNPs in all genes are homozygous | 12.7 | |||||

Caucasian population frequencies.

No population-based genotype frequencies available, homozygous frequencies calculated using the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium formula and the allele frequency.

Table 3.

LOI in the imprinted gene set

| Sample | Heterozygous genes (Paternally/Maternally expressed) |

<1 | 1<>3 | 3<>6 | Loss of imprinting (%) 6<>10 |

10<>20 | 20<>50 | >50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal placenta tissue | ||||||||

| 1 | 4/2 | IGF2, PEG10, GTL2, TP73 | ZAC | PEG1 | ||||

| 2 | 1/0 | PEG10 | ||||||

| 3 | 0/2 | H19, TP73 | ||||||

| 4 | 5/0 | IGF2, PEG10, DLK1 | ZAC | PEG3 | ||||

| 5 | 2/1 | PEG1, H19 | IGF2 | |||||

| 6 | 2/0 | ZAC, DLK1 | ||||||

| 7 | 3/2 | IGF2, PEG1, DLK1, H19 | TP73 | |||||

| 8 | 1/1 | H19 | IGF2 | |||||

| 9 | 2/0 | IGF2 | ZAC | |||||

| 10 | 5/0 | IGF2, PEG10, ZAC, DLK1 | PEG3 | |||||

| 11 | 2/0 | PEG1 | PEG10 | |||||

| 12 | 3/2 | ZAC, DLK1, GTL2 | PEG3 | IGF2 | ||||

| Placental infection | ||||||||

| 13 | 2/0 | IGF2, DLK1 | PEG3 | |||||

| 14 | 1/1 | DLK1,TP73 | ||||||

| Preterm placenta | ||||||||

| 15 | 5/1 | PEG1, PEG10, ZAC, DLK1 | IGF2 | GTL2 | ||||

| 16 | 2/0 | IGF2 | ZAC | |||||

| 17 | 1/1 | PEG1, GTL2 | ||||||

| Preeclampsia placenta | ||||||||

| 18 | 3/1 | IGF2, DLK1, TP73 | PEG3 | |||||

| 19 | 6/3 | PEG10, GTL2, TP73 | PEG1 | IGF2, PEG3, DLK1, H19 | ZAC | |||

| 20 | 2/1 | PEG10, DLK1, TP73 | ||||||

| IUGR placenta | ||||||||

| 21 | 2/2 | ZAC, GTL2, TP73 | PEG1 | |||||

| 22 | 2/1 | ZAC, GTL2 | PEG1 | |||||

| 23 | 1/0 | IGF2 | ||||||

| 24 | 2/1 | PEG3,ZAC | GTL2 | |||||

| 25 | 2/1 | ZAC, DLK1, TP73 | ||||||

| 26 | 4/1 | PEG10, TP73 | PEG1 | PEG3 | DLK1 | |||

| 27 | 2/1 | IGF2, DLK1, GTL2 | ||||||

| TOTAL | 62 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 5 | |

Figure 3.

LOI in placental tissue. (A) Heterozygosities distribution; (B) LOI >3% in samples with different pathologies.

Maternal contamination

One possible confounder in LOI measurements is contamination of placental RNA with RNA from maternal lymphocytes, since the placenta is perfused by maternal blood. We determined the fraction of cells of maternal origin by examining genomic DNA in placentas homozygous for a gene with a readout polymorphism where the mother was heterozygous. Three examples are analyzed in Table 2B, each on different placentas. For GNAS1 and TXK, the level of maternal contamination was <0.1%. The allelic discrimination with Taq DNA polymerase was insufficient for OSBPL5, requiring the use of the more discriminating DNA polymerase ΔZO5, where we observed ΔCt = 6.99 for P3, or <1% maternal contamination. For OSBPL5 the level of maternal contamination was <1%. We also measured the fraction of RNA of maternal origin. For all three RNA measurements, the level of maternal contamination was <0.1%.

Discussion

Current methods for measuring LOI rely on determination of DNA methylation patterns of paternal and maternal alleles,22 carried out in the promoter region of imprinted genes. These assays measure LOI as a deviation from 50:50 in the C:T content at the site of the imprinting methylation, often limiting the sensitivity of the assay. Another limitation to methylation analysis is the fact that it does not directly measure gene expression. As DNA methylation represents only one of the processes involved in imprinting regulation, it is not necessarily correlating directly with the overall imprinting profile of a specific gene or the phenotypic expression of the gene. Accumulating evidence demonstrate the lack of correlation between DNA methylation and monoallelic silencing of the imprinted gene.23,24 In this work, we introduced a new comprehensive, highly sensitive and functional assay for measuring LOI using mRNA expression of each allele of an imprinted gene set in placental tissue.

All assays on placentas are subject to the complication of maternal contamination. Our examination of this limitation indicated that maternal contamination was not a problem within the quantitative limits of the assay (<1% LOI). The use of readout polymorphisms in heterozygotes places two unique limitations on our method. First, not all genes contain common readout polymorphisms. Secondly, we can determine LOI for a given imprinted gene at best 50% of the time for a given sample. We suggest that the advantage of using functional polymorphisms outweighs these disadvantages. First, inclusion of genes measurable by our functional assay, but not measurable by methylation analysis can balance out the genes lost to analysis by the absence of readout polymorphisms. Secondly, we can use the LOI data to identify functional genomic markers that correlate with LOI, such as known imprinting control regions associated with some imprinted genes, in those instances where genomic markers exist for a particular gene.

We found a wide range of LOI in human placenta (0–96%). We found that ~25% heterozygosities showed LOI >3%, with examples of all 9 genes tested both being completely imprinted and exhibiting significant LOI. We have demonstrated that we can detect LOI down to levels of less than 1%, a significant improvement on standard techniques. The observed lack of dependence of LOI on expression level precludes any contribution of allele dropout to the LOI measurements. These results indicate LOI is a common phenomenon in human placentas. We presented a preliminary analysis of LOI for different placental pathologies in Figure 3B. We chose to study LOI in placenta because most of the imprinted genes are involved in placental and fetal development.25 Because of the small numbers of genes and individuals comprising the 93 heterozygosities, these data are too preliminary to demonstrate clinical significance. Although the functional assay presented here is proof-of-principle by nature, it has the potential to assemble a large dataset of LOI as well as be implemented in larger epidemiologic studies. Future work will be directed toward improving our assay in two aspects. Firstly, we will enlarge the gene set to include all imprinted genes with common readout polymorphisms. Thus, we would be able to assay a significant number of genes from each placenta. Secondly, we will enlarge the population, with emphasis on placentas from normal deliveries, preeclampsia cases and IUGR cases.

Materials and Methods

Study population

Fresh discard placental tissues from normal deliveries were collected from the on-campus obstetrical practices of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Medicine—Mount Sinai Medical Center (New York, NY). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mount Sinai Medical Center. Maternal blood was collected for three samples by aspiration from the exterior of the outer placental layer. Deidentified placental tissues and processed samples from Yale Medical School (New Haven, CT) were retrieved from banked specimens collected as a part of an ongoing IRB-approved research protocol to study adverse outcomes of pregnancy. These adverse outcomes included IUGR (intrauterine growth restriction), preeclampsia (PE), and intrauterine infection (IUI).

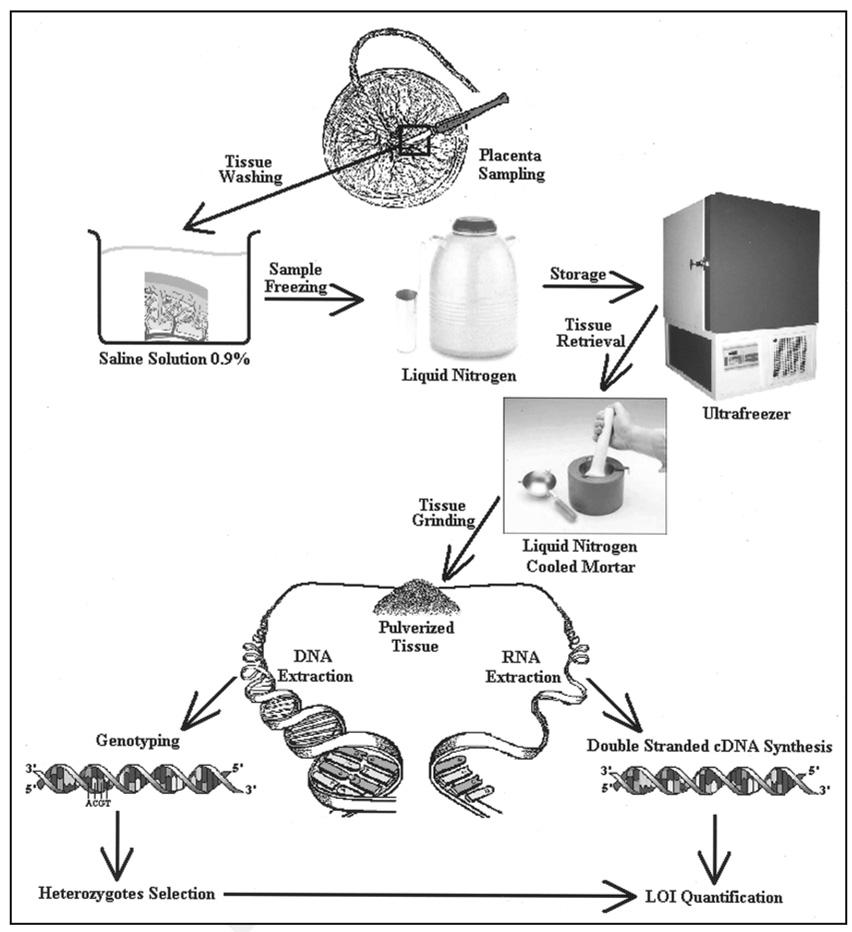

These pregnancies had been identified prospectively for inclusion in the study in the immediate intrapartum period. Control placentas were obtained from pregnancies with appropriate-for-gestational-age (AGA) fetuses delivered at ≥37 weeks and ultrasound estimated fetal weight (EFW) >10th percentile with no other evidence suggestive of IUGR, such as unexplained oligohydramnios or prematurely calcified placentas from pregnancies with no known medical conditions. IUGR placentas were obtained from pregnancies known to be severely growth-restricted. Severe IUGR was defined by ultrasound EFW that was less than 3rd percentile for estimated gestational age (EGA), with either absent end-diastolic flow (AEDF) or reversed end-diastolic flow (REDF) of the umbilical artery, and/or with or without oligohydramnios. PE was defined as a maternal blood pressure >140 mmHg systolic or >90 diastolic in women who were normotensive prior to 20 weeks of gestation associated with new-onset proteinuria (urinary protein >300 mg in 24 hours). These are well-established criteria for IUGR and PE.26,27 The placentas identified as having IUI were defined by having at least two or more of the following criteria in labor: (1) maternal temperature >100.4°F; (2) maternal tachycardia >100 beats per minute; (3) fetal tachycardia >160 beats per minute; or uterine tenderness. Placental pathology for the IUI cases was confirmed on clinical histological examination to be consistent with the diagnosis of acute chorioamnionitis. All pregnancies identified for inclusion in the original study were singleton and without major congenital fetal anomalies. Known multiple gestations and karyotypically abnormal fetuses were excluded. EGA at delivery were assigned by the patient’s last menstrual period and/or ultrasound confirmation prior to 20 weeks of gestation. Umbilical cord Doppler examinations were performed using pulsed Doppler at the placental insertion site, as previously described.28 Doppler wave forms on the suspected IUGR fetuses were classified as AEDF, REDF, and diastolic flow present. The placentas at both sites were collected sterilely following delivery of the neonate, and transferred to the laboratory for tissue collection. Biopsies free of maternal decidua and measuring >5 cm3 were removed from the placenta midway from the cord to the edge, washed extensively with sterile PBS to remove as much blood as possible, blotted with sterile gauze, and placed in sterile containers of liquid nitrogen until the tissue blanched and the liquid nitrogen evaporated. The placenta samples were aliquoted into 2 ml cryogenic storage tubes and stored at −80°C for future use. The experimental protocol for preparation of samples for analysis is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Placenta sampling and storage. A piece of placenta is excised from the whole tissue, soaked in sterile saline solution, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C. In order to extract DNA and RNA from the tissue, the sample is ground in a liquid nitrogen cooled mortar to prevent thawing. DNA is ultimately analyzed to identify heterozygous samples for the imprinting gene set while RNA is converted in double stranded cDNA.

Nucleic acid extraction

DNA from blood was extracted using the High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche Applied Science) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Frozen placenta tissues were pulverized to powder on dry ice. DNA from placentas was extracted using the QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen-Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was stored at −20°C.

RNA was extracted in three steps

Tissue powder was first thawed in lysis buffer, and homogenized using the QIAShredder Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Secondly, RNA was extracted using the RNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, to assure high purity, two on-column DNA digestions were performed with DNase I (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Isolated RNA was kept in RNase-free water at −70°C.

cDNA synthesis

Single stranded cDNA was replicated from total RNA using random primers in the AffinityScript™ Multiple Temperature cDNA Synthesis Kit (Stratagene-La Jolla, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, selecting 50°C for the second incubation step. The cDNA was cleaned with a PCR purification kit (Qiagen). For each reaction, 30 µl of cDNA at ~20 ng/µl was stored in DEPC water at −20°C.

Imprinted genes and readout SNPs

A total of six paternally- and three maternally-expressed genes were selected for assay development (Table 1). These genes were selected because (1) they are expressed in human placenta; (2) they are known to be imprinted in human placenta; and (3) there exists a suitable readout single nucleotide polymorphism in their transcripts. The criteria for selecting readout SNPs include: (1) being synonymous coding SNPs or residing in 3' or 5' untranslated regions of the mRNA; (2) minor allele frequency greater than 20%, which corresponds to a 32% heterozygosity based on Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium.

PCR amplicons containing readout polymorphisms

cDNAs were amplified with gene-specific primers bracketing the readout polymorphism. The primers are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Reaction mix was prepared as follows: Buffer (50 mM TrisOH + HCl, pH 7.5; 50 mM KOAc; 2% glycerol, 0.1 mg/ml BSA); 4 mM Mg(OAc)2; 0.2 mM each dNTPs (dUTP replacing dTTP); 0.2 mM primers; 0.25 x SYBR Green (Invitrogen); 5 U/µl AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems); 20 ng single stranded cDNA template; final volume 20 µl. Cycling conditions were: 95.0°C for 10 min, followed by 15 cycles of 95.0°C for 30 sec, 65.0°C for 30 sec and 72.0°C for 30 sec.

qASPCR

Allele-specific primers are listed in Supplementary Table 2. These primers were optimized for allelic discrimination using AmpliTaq Gold™ on DNA. PCR amplicons from heterozygous placental samples for the selected readout SNPs were diluted 103–107-fold based on the abundance of the mRNA and amplified on the LightCycler480™ (Roche) in the reaction containing: Buffer as above; 4 mM Mg(OAc)2; 0.2 mM each dNTPs (dUTP replacing dTTP); 0.2 mM primers; 0.25 x SYBR Green (Invitrogen); 5 U/µl AmpliTaq Gold; diluted double stranded DNA template (see text); final volume 20 µl. Cycling conditions were: 95.0°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95.0°C for 30 sec, 65.0°C for 30 sec and 72.0°C for 30 sec.

LOI quantification

We consider the following: (1) LOI is a measurement of expression of the silenced allele; and (2) this measurement is directly related to the allele frequency (f) for the silenced allele15 as:

The LOI can be calculated as:

where the |ΔCt| refers to the absolute difference between the allelespecific Ct values on cDNA level corrected for the specificity of the allele-specific PCR (see Suppl. Materials and reviewed in ref. 15). Allele specificity was determined using heterozygote DNA amplified with the same gene specific primers listed in Supplementary Table 1. Homozygote controls were included to test the level of ASPCR misextension. All measurements were carried out in triplicate; the standard deviation (σLOI) of LOI was calculated as:

Stability of RNA in placentas

A time course analysis was conducted on three placenta samples to test the stability of placental RNAs. Tissues, after excision from the whole placentas, were soaked in sterile saline at 4°C immediately after delivery. Small segments were excised and frozen in liquid nitrogen at 0, 5, 15 and 45 minutes. We assessed the expression levels of six genes (PEG1/MEST, PEG3/PW1, GTL2/MEG3, H19, GNAS1, ACTB) as described above under “PCR amplicons” and normalized against 18S rRNA. The calibration curve against 18S rRNA was used to control for variation in total RNA used in the mRNA stability analyses (see Suppl. Materials).

Maternal contamination

Three pairs of maternal blood and placenta were genotyped for six genes with readout polymorphisms to identify the mother-placenta genotype combinations showing the mother to be heterozygous and the placenta to be homozygous for the same SNP. qASPCR was carried out at the DNA and cDNA level to detect the presence of the maternally-unique allele in the placental sample. The controls were identical to those used for LOI measurements. The level of maternal allele in the DNA template corresponds to the number of maternal cells whereas the level in the cDNA corresponds to the relative number of transcripts. Reaction conditions were the same used with AmpliTaq Gold for allele-specific PCR on DNA and cDNA as previously reported. We confirmed these results using hot start ΔZO5 polymerase (Roche Molecular Systems) capable of a much higher allele specificity using the following conditions: ΔZO5 Buffer (100 mM Tricine buffer, pH 7.5, 100 mM KOAc, 16% glycerol, 2% Dimethyl Sulfoxide); 4 mM Mg(OAc)2; 0.2 mM each dNTP (dUTP replacing dTTP); 0.2 mM primers (each); 0.25X SYBR Green (Invitrogen); 0.4 U ΔZO5 Gold DNA Polymerase; 20 ng template; final volume 20 µl. Cycling conditions were: 95.0°C for 12 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95.0°C for 30 sec, 60.0°C for 30 sec and 72.0°C for 30 sec.

Supplementary Material

Note

Supplementary materials can be found at: www.landesbioscience.com/supplement/LambertiniEPI3-5-Sup.pdf

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants NO1 AI50028 and U19 AI06231 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and by the Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Disease Prevention Institute of the Department of Community and Preventive Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine. We thank Dr. Lauren Ferrara from the Mount Sinai OB/GYN Department for her help in collecting placentas from on-campus practices, Dr. Seth Guller from the Yale University School of Medicine for providing additional samples, Ms. Yula Ma for her technical assistance, and Dr. Tom Myers from Roche Molecular Systems (Alameda, CA) for generously providing our lab with ΔZO5 DNA polymerase.

Abbreviations

- LOI

loss of imprinting

- qASPCR

quantitative allele-specific PCR

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase-PCR

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- IUI

intrauterine infection

- IUGR

intrauterine growth restriction

- PE

preeclampsia

- AGA

appropriate-for-gestational-age

- EFW

estimated fetal weight

- EGA

estimated gestational age

- AEDF

absent end-diastolic flow

- REDF

reversed end-diastolic flow

- ICR

imprinting control region

References

- 1.Sasaky H, Ishino I, editors. Cytogenetic Genome Res—Complete Issue. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilghman SM. The sins of the fathers and mothers: genomic imprinting in mammalian development. Cell. 1999;96:185–193. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80559-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badcock C, Crespi B. Imbalanced genomic imprinting in brain development: an evolutionary basis for the aetiology of autism. J Evol Biol. 2006;19:1007–1032. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glaser RL, Ramsay JP, Morison IM. The imprinted gene and parent-of-origin effect database now includes parental origin of de novo mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:29–31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luedi PP, Dietrich FS, Weidman JR, Bosko JM, Jirtle RL, Hartemink AJ. Computational and experimental identification of novel human imprinted genes. Genome Res. 2007;17:1723–1730. doi: 10.1101/gr.6584707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ono R, Shiura H, Aburatani H, Kohda T, Kaneko-Ishino T, Ishino F. Identification of a large novel imprinted gene cluster on mouse proximal chromosome 6. Genome Res. 2003;13:1696–1705. doi: 10.1101/gr.906803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monk D, Wagschal A, Arnaud P, Muller PS, Parker-Katiraee L, Bourc’his D, et al. Comparative analysis of human chromosome 7q21 and mouse proximal chromosome 6 reveals a placental-specific imprinted gene, TFPI2/Tfpi2, which requires EHMT2 and EED for allelic-silencing. Genome Res. 2008;18:1270–1281. doi: 10.1101/gr.077115.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrne J, Cama A, Reilly M, Vigliarolo M, Levato L, Boni L, et al. Multigeneration maternal transmission in Italian families with neural tube defects. Am J Med Genet. 1996;66:303–310. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19961218)66:3<303::AID-AJMG13>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatkupt S, Skurnick JH, Jaggi M, Mitruka K, Koenigsberger MR, Johnson WG. Study of genetics, epidemiology, and vitamin usage in familial spina bifida in the United States in the 1990s. Neurology. 1994;44:65–70. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMinn J, Wei M, Schupf N, Cusmai J, Johnson EB, Smith AC, et al. Unbalanced placental expression of imprinted genes in human intrauterine growth restriction. Placenta. 2006;27:540–549. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jelinic P, Shaw P. Loss of imprinting and cancer. J Pathol. 2007;211:261–268. doi: 10.1002/path.2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jirtle RL, Skinner MK. Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:253–262. doi: 10.1038/nrg2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim KP, Thurston A, Mummery C, Ward-van Oostwaard D, Priddle H, Allegrucci C, et al. Gene-specific vulnerability to imprinting variability in human embryonic stem cell lines. Genome Res. 2007;17:1731–1742. doi: 10.1101/gr.6609207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi H, Suda C, Abe T, Kohara Y, Ikemura T, Sasaki H. Bisulfite sequencing and dinucleotide content analysis of 15 imprinted mouse differentially methylated regions (DMRs): paternally methylated DMRs contain less CpGs than maternally methylated DMRs. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;113:130–137. doi: 10.1159/000090824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J, Germer S, Higuchi R, Berkowitz G, Godbold J, Wetmur JG. Kinetic polymerase chain reaction on pooled DNA: a high-throughput, high-efficiency alternative in genetic epidemiological studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinstein LS. The role of tissue-specific imprinting as a source of phenotypic heterogeneity in human disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:927–931. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catalogue of Parent of Origin Effects—Otago University—Dunedin. New Zealand: Otago University—Dunedin, New Zealand—; Available at http://igc.otago.ac.nz/home.html. [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Genomic Imprinting Website—Duke University—Durham. North Carolina, USA: Duke University—Durham, North Carolina, USA—; Available at http://www.geneimprint.com/site/home. [Google Scholar]

- 19.UniGene—EST Profile Viewer—National Center For Biotechnology Information— National Library of Medicine—National Institute of Health—Bethesda. Maryland, USA: National Center For Biotechnology Information—National Library of Medicine—National Institute of Health—Bethesda, Maryland, USA—; Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=unigene. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reik W, Constancia M, Fowden A, Anderson N, Dean W, Ferguson-Smith A, et al. Regulation of supply and demand for maternal nutrients in mammals by imprinted genes. J Physiol. 2003;547:35–44. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.033274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sood R, Zehnder JL, Druzin ML, Brown PO. Gene expression patterns in human placenta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5478–5483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508035103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anway MD, Cupp AS, Uzumcu M, Skinner MK. Epigenetic transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors and male fertility. Science. 2005;308:1466–1469. doi: 10.1126/science.1108190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byun HM, Wong HL, Birnstein EA, Wolff EM, Liang G, Yang AS. Examination of IGF2 and H19 loss of imprinting in bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10753–10758. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monk D, Arnaud P, Apostolidou S, Hills FA, Kelsey G, Stanier P, et al. Limited evolutionary conservation of imprinting in the human placenta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6623–6628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511031103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charalambous M, da Rocha ST, Ferguson-Smith AC. Genomic imprinting, growth control and the allocation of nutritional resources: consequences for postnatal life. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2007;14:3–12. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e328013daa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee MJ, Conner EL, Charafeddine L, Woods JR, Jr, Priore GD. A critical birth weight and other determinants of survival for infants with severe intrauterine growth restriction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;943:326–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sibai B, Dekker G, Kupferminc M. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2005;365:785–799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17987-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams KP, Farquharson DF, Bebbington M, Dansereau J, Galerneau F, Wilson RD, et al. Screening for fetal well-being in a high-risk pregnant population comparing the nonstress test with umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1366–1371. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis A, Reik W. How imprinting centres work. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;113:81–89. doi: 10.1159/000090818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Note

Supplementary materials can be found at: www.landesbioscience.com/supplement/LambertiniEPI3-5-Sup.pdf