Abstract

The function, regulation, and molecular structure of the cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchangers (NCXs) vary significantly among vertebrates. We previously reported that β-adrenergic suppression of amphibian cardiac NCX1.1 is associated with specific molecular motifs. Here we investigated the bimodal, cAMP-dependent regulation of spiny dogfish shark (Squalus acanthias) cardiac NCX, exploring the effects of molecular structure, host cell environment, and ionic milieu. The shark cardiac NCX sequence (GenBank accession no. DQ 068478) revealed two novel proline/alanine-rich amino acid insertions. Wild-type and mutant shark NCXs were cloned and expressed in mammalian cells (HEK-293 and FlpIn-293), where their activities were measured as Ni2+-sensitive Ca2+ fluxes (fluo 4) and membrane (Na+/Ca2+ exchange) currents evoked by changes in extracellular Na+ concentration and/or membrane potential. Regardless of Ca2+ buffering, β-adrenergic stimulation of cloned wild-type shark NCX consistently produced bimodal regulation (defined as differential regulation of Ca2+-efflux and -influx pathways), with suppression of the Ca2+-influx mode and either no change or enhancement of the Ca2+-efflux mode, closely resembling results from parallel experiments with native shark cardiomyocytes. In contrast, mutant shark NCX, with deletion of the novel region 2 insertion, produced equal suppression of the inward and outward currents and Ca2+ fluxes, thereby abolishing the bimodal nature of the regulation. Control experiments with nontransfected and dog cardiac NCX-expressing cells showed no cAMP regulation. We conclude that bimodal β-adrenergic regulation is retained in cloned shark NCX and is dependent on the shark's unique molecular motifs.

Keywords: sodium/calcium exchanger, cAMP, bimodal regulation, cloning, cardiac electrophysiology

the sodium/calcium exchanger (NCX) proteins are widely distributed in the biosphere, where they are generally found to exchange 1 Ca2+ for 3 Na+ across the sarcolemmal membrane, thereby generating net electrical current in the opposite direction of the Ca2+ flux (2, 6, 37). NCX flux is modulated by the membrane potential (Vm) and the intra- and extracellular concentrations of the transported ions, which contribute to the driving force [Vm − ENaCa, where Na+/Ca2+ exchange equilibrium potential (ENaCa) = 3ENa − 2ECa for 3 Na+:1 Ca2+ exchange] of Na+/Ca2+ exchange current (INaCa) flux and allosteric regulation (19, 20). NCX activity varies during the cardiac cycle: first, it contributes some Ca2+ entry during depolarization, and then it is involved in efflux of Ca2+ during repolarization and diastole (3, 4, 6, 7). In concert with other Ca2+-transporting proteins and ion channels, the electrogenic activity and Ca2+ flux of NCX contribute to shape the action potential and control the strength of the heartbeat and its relaxation through tidal changes in cytosolic Ca2+ (24, 27, 28).

NCX activity in the mammalian heart has been reported to be either unaltered (10, 19–21, 25) or enhanced (16, 34) by β-adrenergic stimulation. In sharp contrast, NCX activity of ventricular myocytes of frog (26) and shark (29) hearts is downregulated by β-adrenergic/cAMP stimulation. Furthermore, although the β-adrenergic stimulation of frog NCX suppresses INaCa equally in both directions (14), suppression of NCX activity in the shark is confined to the Ca2+-influx mode with no change, or even enhancement, of the Ca2+-efflux mode of NCX (“bimodal regulation”) (43).

In an attempt to understand the molecular basis underlying the differential β-adrenergic regulation, we found that the cloned frog cardiac NCX had a unique insertion of 9 amino acids (27 bp, “exon X”) with a Walker A motif, or P loop (22), which conferred the unique cAMP suppressive effect to the clone (38). Interestingly, this regulation could be conferred onto a chimeric dog exchanger that incorporated the critical Walker A motif of the frog NCX (17), indicating that, despite the species-related differences in ionic milieu, heart rate, temperature, or the presence (dog) or absence (frog) (33) of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), the distinctive NCX regulatory characteristics depended on the presence of a unique amino acid sequence.

In this report, we have similarly explored the unique bimodal regulation of shark INaCa by cloning and expressing the shark NCX in mammalian expression systems (HEK-293 and FlpIn-293 cells). The cloned shark NCX revealed novel molecular motifs that may be responsible for its regulatory properties. To test this theory, we created a mutant shark whose unique region 2 insert was deleted. Using fluorescent Ca2+ imaging and electrophysiology, we characterized the expression and function of the shark and mutant shark clones and compared their regulatory characteristics with those of native shark cardiomyocytes. The shark and mutant shark NCX clones remained physiologically functional in eukaryotic cells; however, although the shark NCX clone retained the essentials of its bimodal β-adrenergic regulation, the mutant shark lost the bimodal nature of its regulation. The finding that the deleted shark-specific insert affected the modality of cAMP-dependent regulation suggests that, similar to the frog, the specific β-adrenergic regulation of the shark NCX is based on its molecular structure.

METHODS

Sequencing Shark Cardiac NCX

Total RNA was obtained from the heart of the dogfish shark with use of TRIzol (Invitrogen/GIBCO, Carlsbad, CA) and subjected to RT using oligo(dT) primers (Invitrogen). PCR was carried out with primers based on DNA sequences for NCX from squid and vertebrates (trout, frog, and mammals). Initially, PCR produced a 171-bp amplicon (41). Using a series of degenerate primers predicted from multiple sequence alignments of NCX from other organisms, this sequence was subsequently extended in both directions to obtain a stretch encoding 720 amino acids that, nevertheless, lacked unconserved extreme ends of the protein (13).

The missing 5′ end was provided from expressed sequence tags posted from Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory. One of the underlying clones (Sa_mx0_45h08/CX196474.1) was generously provided by Dr. Towle (42) and sequenced completely to provide the first 1,780 bp of NCX, including apparent 5′-untranslated sequences within 90 bp upstream from the putative start codon (see Supplemental Fig. 1 in the online version of this article). In a parallel approach to completing the sequence, a cDNA library was constructed, and several clones were identified by screening with unique sequences from the original shark NCX1. Although multiple clones with long region 2 inserts were obtained, they terminated within a very narrow area, falling ∼200 bp short of the 5′-terminal expressed sequence tag clone Sa_mx0_45h08. Four clones provided sequences with ∼600 bp past the stop codon (bp 3175–3177), including the poly(A) tail of the mRNA.

Reconstruction of the Full-Length cDNA

An expression construct for the native shark NCX containing the full-length NCX cDNA, including a complete 3′-untranslated region, was made in the vector pCMV-SPORT6.1 (Invitrogen). The NCX sequence nucleotides 1–1780 were derived from the cDNA clone Sa_mx0_45h08. Nucleotides 1992–3845 were derived from a cDNA clone obtained from shark heart cDNA library in lambda ZAP-XR. The sequence of the remaining gap was added from RT-PCR products generated directly from shark heart RNA as obtained in our initial direct PCR product-sequencing effort (see Supplemental Fig. 1).

Initial attempts to propagate the construct-containing bacterial strain for large-scale DNA isolation failed, inasmuch as it displayed rapid plasmid loss on growth at 37°C in liquid medium containing appropriate antibiotic. It was subsequently found that the construct in the bacterial strain STBL2 (Invitrogen) could be stably grown on rich solid medium at 30°C for 48 h. The medium was prepared from autoclaved 1.6% tryptone-1% yeast extract-1.2% agar, cooled to ∼50°C, and supplemented with 0.1 M Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 20 mM MgCl2, 50 mM glucose, and 200 μg/ml ampicillin. Bacterial outgrowth as “fat streak” from 10–20 plates provided sufficient cell yield for plasmid DNA purification with use of Qiagen columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Unusual strain behavior was probably due to ectopic expression of the shark insert, despite the presence of transcription terminator sequence in the vector (pCMV-SPORT6.1).

Mutant Shark Development

The role of the region 2 insert was tested by construction of a mutant shark (shark 2), where the second A/P-rich insert had been eliminated by deletion of bp 1624–1785 coding for amino acids 512–565. This was accomplished using PCR to insert an endonuclease Not I site at bp 1622–1629; a Not I site is naturally present at bp 1780–1787 downstream of the unique sequence, allowing convenient cloning of the resulting PCR fragment. PCR by the G-C-rich PCR system (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) was performed using reverse primer (5′-ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCGCTCAGGCCCACGCGCAGGTTGCT-3′) to insert the new Not I site. The forward primer for cloning (5′-GGTCAGCCGCATCTACTTCG-3′) was 5′ to an endonuclease BstB I restriction site, which occurs upstream of the second A/P-rich shark sequence at bp 1345. The resulting PCR product was then inserted into the rest of the shark sequence after digestion with BstB I/Not I. The final mutant shark expression construct was bidirectionally sequenced for verification.

Transient and Stable Expression of Shark Cardiac NCX in HEK-293 Cells

On the day before transient transfection, HEK-293 cells were split onto coverslips in antibiotic-free medium. The cells were transfected with shark, mutant shark, dog, or empty vector pCMV-SPORT6.1 using Fugene 6 (Roche Diagnostics) or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) protocols according to the manufacturers' instructions. The cells were cultured for 24–48 h before they were used in experiments.

Cell lines with stable expression of shark (S cells) and mutant shark (MS cells) NCX constructs were created using FlpIn-293 cells (Invitrogen), which are derived from HEK-293 cells. Lipofectamine cotransfection of FlpIn-293 cells with a Flp-In expression vector and the Flp recombinase vector pOG44 resulted in targeted integration of the expression vector to the same locus in every cell. To prepare the Flp-In expression vector, recombinant cDNAs for shark and mutant shark NCX were cut out of the vector pCMV-SPORT6.1 (Invitrogen) and inserted into the FlpIn pFRT expression vector in two pieces: 3′ Apa I to the middle Not I site and 5′ EcoR V to the middle Not I site. The resulting plasmids were sequenced for verification. Transfected cells were selected by culturing in the presence of hygromycin B (200 μg/ml) for 2 wk; then the colonies were separated, cultured, and subjected to selection on the basis of NCX expression. Stable cells expressing the dog NCX were generously provided by Dr. Donald Hilgemann. All stable cells were cultured at 37°C, and experiments were carried out at room temperature (22–24°C).

Confocal Ca2+ Imaging

Imaging of intracellular Ca2+ was performed with confocal fluorescence microscopy (Noran Odyssey acoustoptical laser scanner; Zeiss Axiovert 135; Olympus WPlanApox60UV, 1.20 NA, 4 frames/s) using transfected HEK-293 and FlpIn-293 cells that were incubated with fluo 4-AM (Invitrogen) or dialyzed with a solution containing 0.1 mM K5-fluo 4 salt (Invitrogen). Stacks of recorded frames were analyzed using custom-designed software (Con2) capable of compensation for bleaching and ratiometric normalization of stacks of fluorescence images relative to an averaged image representing the resting condition.

Cell Isolation

Animal procedures were carried out in accordance with institutional and national guidelines and were approved by the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee.

Single ventricular cells were isolated from hearts of dogfish sharks (Squalus acanthias) as previously described (43) and used within 2–8 h. Briefly, dogfish sharks (2–7 kg) were immobilized by complete spinal pithing. Hearts were removed and mounted on a Langendorff apparatus. The two major coronary vessels and aorta were cannulated and perfused with oxygenated Ca2+-free elasmobranch solution containing (in mM) 270 NaCl, 4 KCl, 3 MgCl2, 0.5 KH2PO4, 0.5 Na2SO4, 350 urea, 10 HEPES, and 5 glucose (pH 7.2) at 30°C for 10–15 min. The heart was then perfused for 15 min with Ca2+-free elasmobranch solution containing 1 mg/ml collagenase (type A, Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) and 0.2 mg/ml protease (type XIV, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and washed free of enzyme with 0.2 mM CaCl2-containing elasmobranch solution for 10 min. The ventricle was then cut free of the cannula and gently agitated in 0.2 mM Ca2+-containing solution to disperse the cells. Cell yields varied greatly, between 20% and 80%, depending on the efficacy of the coronary perfusion.

Voltage-Clamp Recording of INaCa in Freshly Dissociated Shark Ventricular Cardiomyocytes and HEK-293 and FlpIn-293 Cells Expressing Shark NCX

Whole cell currents were measured with a 3- to 5-MΩ pipette attached to the input of a patch-clamp amplifier (model 8900, Dagan Instruments, Minneapolis, MN). After the whole cell voltage-clamp configuration was established, a “ramp-clamp” protocol (see Fig. 7, A and B), initiated by short-step depolarization from −60 to +80 mV, a ramp down to −120 mV, and a recovery to −60 mV [to activate NCX1-generated current (INaCa)], was applied to measure the voltage dependence of INaCa. During voltage-clamp procedures, K+ currents were suppressed by omission of K+ from the external solution and inclusion of tetraethylammonium (TEA) in the internal solution. The Na+ current was suppressed by use of a relatively depolarized holding potential (−60 mV), and Ca2+ current (ICa) was generally suppressed by addition of 1–5 μM nifedipine. NiCl2 (5 mM) or CdCl2 (1 mM) was used in the external solution to block INaCa during brief intervals. Changes in the baseline current were often measured during the ramp-clamp protocol before, during, and after Ni2+ or Cd2+ exposure. In addition to activation of the NCX via manipulation of the voltage, NCX was also activated by alteration of extracellular Na+ and Ca2+ concentrations ([Na+]o and [Ca2+]o) of some test solutions (see Solutions and Chemicals). Collected current recordings were analyzed using ORIGIN software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Transfected HEK-293 and FlpIn-293 cells were cultured on 25-mm coverslips, which served as an exchangeable bottom in the perfusion chamber, which, in turn, was used for voltage-clamp and Ca2+-imaging procedures. Dissociated shark myocytes were placed in a chamber on the stage of an inverted microscope and superfused with 2 mM Ca2+-containing elasmobranch solution. Some experimental details varied depending on the cell type and the use of Ca2+ imaging.

Solutions and Chemicals

Stably transfected FlpIn-293 cells were dialyzed with a pipette solution containing (in mM) 40 KCl, 60 K-aspartate, 10 or 20 TEA-Cl, 10 or 20 mM NaCl, 0.1 Mg-ATP, 10 HEPES (titrated to pH 7.2 with KOH), and Ca2+ buffers yielding an estimated intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) of 100 nM. High-Ca2+ buffering was provided by 0.1 mM BAPTA, 5 mM EGTA, and 2.66 mM CaCl2. For low-Ca2+ buffering in experiments with concomitant Ca2+ imaging, we used 0.1 mM BAPTA, 0.1 mM K5-fluo 4, and 0.02 mM CaCl2.

The basic external Tyrode solution contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5.4 TEA-Cl, 5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose (titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH). For activation of the Ca2+-influx mode in the solution-exchange experiments, the Na+ concentration was lowered from 140 to 5 mM by KCl substitution for the high extracellular K+ concentration ([K+]o)-low [Na+]o experiments or by TEA-Cl substitution for the low [Na+]o experiments; [Na]o was maintained at 140 mM, while [K]o was increased from 5 to 40 mM by addition of KCl for the high [K]o-normal [Na]o depolarizing experiments. For activation of the Ca2+-efflux mode in the solution-exchange experiments, Na+ concentration was increased from 140 to 210 mM, while [Ca2+]o declined from 5 to 0.5 mM. cAMP (10 μM) or dibutyryl cAMP (DBcAMP, 10 or 100 μM; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) was used as β-adrenergic agonist. An electronically controlled multibarreled puffing system was used for rapid exchange of solution (9).

For the dissociated shark cardiomyocytes, the pipette solution contained (in mM) 200 KCl, 50 NaCl, 300 urea, 10 HEPES (titrated to pH 7.2 with KOH), 5 Na2ATP, 5 MgCl2, 10 TEA, 10 mM EGTA, and 6 CaCl2, yielding an estimated [Ca2+]i of ∼200 nM. Isoproterenol or epinephrine (5 μM) was used as β-adrenergic agonist. [Na+]o of some test solutions was increased from 250 to 450 mM by urea replacement or lowered to 10 mM by Cs+ substitution.

Statistical Analyses

Values are means ± SE (n = number of observations). Statistical analysis was carried out using paired and unpaired Student's t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Sequence of Shark Cardiac NCX

We deduced the cDNA sequence of shark cardiac NCX to determine its relationship to the known sequences of mammalian and frog NCX1.1 and to explore whether it contained any novel molecular motifs that might be relevant to the differential cAMP-dependent regulation observed in these species. A full-length clone was reconstructed from two cDNA clones and a PCR product (see methods). Sequencing was repeated on a number of partial clones from cardiac tissues derived from several individual animals and from different cardiac regions (see Supplemental Fig. 1A) to reduce the probability that we might have missed uncommon gene products. The completed sequence (GenBank accession no. DQ 068478) encodes a 1,034-amino acid polypeptide.

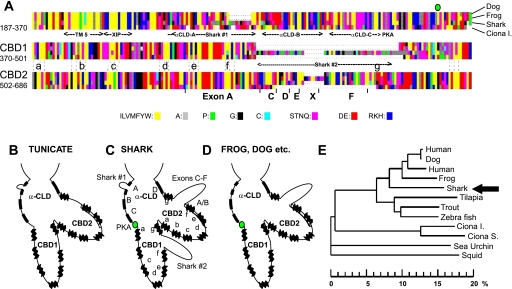

The deduced sequence of amino acids of shark cardiac NCX was aligned (Clustal W2) with representative sequences from other animals, with the dog cardiac NCX1 (30) used as reference for the numbering of amino acids; e.g., the cytoplasmic loop encompasses amino acids R219–A667 (see Supplemental Fig. 1). In Fig. 1A, shark NCX is compared with dog, frog, and tunicate Ciona intestinalis NCX sequences (see Supplemental Fig. 2). The genomic tunicate sequence was included as a benchmark for chordate evolution. The alignments (Fig. 1A; also see Supplemental Fig. 2) show that the shark sequence displays a distinct pattern of similarities to and differences from other chordate sequences. The putative transmembrane-spanning α-helices at the amino (TM1–TM5) and carboxy (TM6–TM9) terminals are highly conserved, and the same is true for the core regions of two Ca2+-binding domains (CBD1 and CBD2), each of which includes seven β-strands (Fig. 1A, a–f) in antiparallel pleated sheets (5, 18, 31). The shark sequence has “cardiac” characteristics, since it has sequence homology with coding that is provided by exons C–F in terrestrial vertebrates. We find no trace of these exons in tunicates or nonchordates. The cytoplasmic regulatory loop (Fig. 1A) coded by the shark cardiac mRNA shows features that may be relevant to cAMP-mediated regulation: 1) the P loop (GxxxxGKS) that is coded by exon X in frog (22) is absent; 2) a potential PKA site (RKAVS357) is present, as in dog and frog, but not in tunicate; and 3) unexpectedly, two conspicuous alanine/proline-rich block insertions of 10 (region 1: L273PAAEAGETAT) and 54 (region 2: A469GPGQAD SSAHAPATAPAHAPSPKVAVRGAGAAAAGCDANDA- ASVSSAPAPT) amino acids are found at locations where vertebrate NCX sequences are of somewhat variable composition and length. The longer insertion (region 2) is within CBD1 at the equivalent position where exons C–F provide a stretch of variable length within CBD2. To test whether this longer insert is essential to the bimodal adrenergic regulation of shark NCX, we constructed a mutant shark (shark 2) with deletion of bp 1624–1785 coding for amino acids 512–565.

Fig. 1.

Amino acid sequence of shark cardiac NCX. A: graphic representation of a partial alignment of long cytoplasmic regulatory loops of cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchangers (NCXs) from dog, frog, shark, and Ciona intestinalis (see Supplemental Fig. 2 for detailed alignment). B–D: major differences in alignment in tunicate, shark, and higher vertebrates. Labeled features include an α-catenin-like domain (α-CLD) with 4 putative α-helical segments (segments A–D) and Ca2+-binding domains, CBD1 and CBD2, each with 7 β-strands (a–g). Species-dependent linker sequences are shown in the A helix of α-CLD (shark region 1) and between β-strands f and g of Ca2+-binding domains: shark region 2 insert in CBD1 and the variably spliced exons C–F in CBD2. E: placement of shark NCX (arrow) in a phylogenetic tree (Clustal W2) of deuterostome NCXs rooted by NCX from the squid Loligo opalescens (GenBank accession no. U93214). Abscissa shows difference in amino acids (%) calculated for core regions of α-repeats and Ca2+-binding domains (see Supplemental Table 1). Vertebrate sequences are based on mRNA from cardiac tissue. GenBank accession nos. are as follows: NM021097 (human, Homo sapiens), M57523 (dog, Canis lupus familiaris), XM415002 (chicken, Gallus gallus), X90839/X90838 (frog, Xenopus laevis), DQ068478 (shark, Squalus acanthias), AAP37041 (tilapia, Oreochromis mossambicus), AAF06363 (trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss), and XP686228 (zebra fish, Danio rerio). Sea urchin is represented by a partial genomic construct (accession no. XM776256) that, similar to the modeled tunicate sequences [C. intestinalis (Ciona I) from AABS01000304 and C. savignyi (Ciona S) from AACT01059174/AACT01057381; see supplemental material in the online version of this article], showed homology with vertebrate NCXs.

Similarities between NCXs from different species are summarized in Fig. 1. The phylogram (Fig. 1E), which quantifies the relationships of the different species at the protein level, reproduces the accepted evolutionary pattern, except the shark sequence appears to diverge from the chordate lineage that leads to mammals after the divergence of the bony fishes, tilapia, trout, and zebra fish. We explored whether different molecular motifs might show different degrees of conservation, which might reveal conservation dictated by changing functional constraints. We found (see Supplemental Table 1) that the degree of conservation was somewhat different for different segments (mammals vs. shark: CBD1 > α1 ∼ α2 > CDB2), but not enough to alter the branching pattern of the phylogram. This attests to a gradual genetic drift in the structurally conserved regions of cardiac NCX.

Verification of Functional Activity of Shark and Mutant Shark Cardiac NCX in HEK-293 and FlpIn-293 Cells

A full-length cDNA of shark NCX and mutant shark NCX was constructed and expressed transiently or stably in HEK-293 and FlpIn-293 cells, respectively (see methods). Functional expression was first verified in experiments with nondialyzed cells (Figs. 2–4), where Ni2+-sensitive inward Ca2+ fluxes were activated by a change in the driving force for NCX (Vm − ENaCa), with use of KCl to depolarize the Vm and/or alterations in [Na+]o to shift the equilibrium potential (ENaCa = 3ENa − 2ECa for 3 Na+:1 Ca2+ exchange).

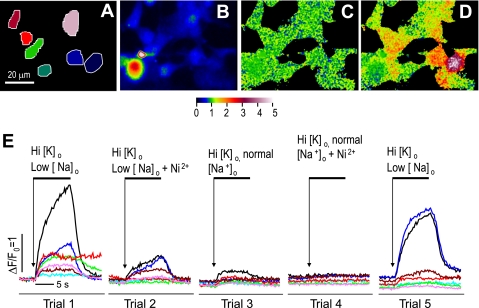

Fig. 2.

Verification of transient transfection of shark NCX into nondialyzed HEK-293 cells by Ca2+ imaging. A: selected color-coded cellular regions corresponding to traces in E. B: average fluorescence intensity before activation. Image was used as divisor to generate ratiometrically normalized fluorescence images in C and D. Threshold for division was adjusted to generate dark areas around cells. C: normalized fluorescence (F/F0) image before activation shows noise in a single frame as green/blue mottle (F/F0 ≅ 1, see color scale). D: normalized fluorescence image at peak of activation (trial 1) shows individual cells as relatively uniform areas of orange or red. E: changes in fluorescence in selected cells during 5 trials with exposure to high extracellular K+ concentration (Hi [K]o, from 5.4 to 40 or 140 mM), with and without reduction in extracellular Na+ concentration {low [Na+]o, from 140 to 5 mM with tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA-Cl) substitution} and addition of 5 mM Ni2+. (Shark NCX was transiently expressed in nondialyzed HEK-293 cells stained with fluo 4-AM.)

Fig. 4.

Ni2+-sensitive Ca2+ signals (C and D) are of comparable magnitude for different NCX constructs and expression systems, but Ni2+-insensitive Ca2+ signals are smaller in stable FlpIn-293 cells (B) than in transiently expressing HEK-293 nondialyzed cells (A). Data are from experiments similar to those described in Figs. 2 and 3 legends. A and B: responses in the absence (solid bars) and presence (hatched bars) of 5 mM Ni2+ in HEK-293 cells transiently transfected with dog NCX, the empty vector (Sham), shark NCX, or mutant shark NCX (A) and in FlpIn-293 cells untransfected (Control) or stably transfected with shark (S cells) or mutant shark (MS cells) NCX (B). Ca2+-dependent fluorescence was activated by high [K]o and low [Na]o (white bars), normal [K]o and low [Na]o (red bars), high [K]o and normal [Na]o (teal bars), and low [Na]o after incubation with 100 μM DBcAMP (blue bars). Difference signals in C and D quantify Ni2+-sensitive changes in Ca2+-dependent fluorescence in the transiently (C) and stably (D) transfected cells.

The level of transient expression was verified initially using Ca2+ imaging of multiple HEK-293 cells incubated with fluo 4-AM (Fig. 2). Imaging with ratiometric normalization (Fig. 2C vs. 2B and Fig. 3C vs. 3B) allowed identification of responsive cells with substantial Ca2+ transients (Figs. 2D and 3D). Figure 2 illustrates a representative experiment in which the Ni2+-sensitive Ca2+ influx in multiple cells transiently transfected with shark NCX could be activated to some degree by KCl depolarization (trial 3, high [K+]o-normal [Na+]o). Depolarization in the presence of low [Na+]o produced a stronger Ca2+ influx (trial 1, high [K+]-low [Na+]o), which was used to screen data [normalized fluorescence (ΔF/F0) >1] before statistical analysis. Routinely, experiments were bracketed with control runs to ensure the sustained viability of the cells (trial 5) and included testing for sensitivity to Ni2+ (trials 2 and 4). In transiently transfected cells, application of 5 mM Ni2+ blocked only about half of the Ca2+ influx activated by low [Na+]o alone (50%: ΔF/F = 1.09 ± 0.20 and 0.54 ± 0.12 for control and Ni2+, respectively, n = 12 each, P = 0.0006) or in combination with high [K+]o (45%: ΔF/F0 = 1.90 ± 0.13 and 1.05 ± 0.09 for control and Ni2+, respectively, n = 24 each, P < 0.0001; Fig. 4, A and C). As summarized in Fig. 4, the Ni2+-sensitive Ca2+ influx responses to low [Na+]o were comparable for the shark (0.56 ± 0.11, n = 12), dog (0.88 ± 0.20, n = 26), and mutant shark (0.38 ± 0.07, n = 6) NCX but were much larger than those of cells transfected with the empty vector (0.040 ± 0.04, n = 23; Fig. 4, A and C, red bars).

Fig. 3.

Verification of stable transfection of shark NCX in nondialyzed FlpIn-293 cells (S cells). A–D (from trial 1) correspond to A–D in Fig. 2. E and F: bracketed measurements of changes in fluorescence in selected color-coded cells during 6 trials with exposure to reduced [Na+]o (low [Na+]o, from 140 to 5 mM with TEA-Cl substitution), with (trials 2 and 5) and without (trials 1, 3, 4, and 6) addition of 5 mM Ni2+, before (trials 1–3) and after (trials 4–6) application of 10 μM dibutyryl cAMP (DBcAMP) for 300 s.

These measurements of Ni2+-sensitive Ca2+ fluxes verify functional transient expression of shark and mutant shark NCX in mammalian HEK-293 cells. They indicate, as expected, that Ca2+ influx via shark NCX is activated more effectively with Na+ withdrawal than with KCl depolarization. In addition, they show that shark NCX Ca2+ influx is comparable to that produced by the dog cardiac NCX under similar conditions.

To achieve more uniform expression and facilitate the study of NCX regulation, we created two lines of FlpIn-293 cells with stable expression of the cloned shark (S cells) or mutant shark (MS cells) NCX (see methods). As illustrated in Fig. 3, the level of expression was again evaluated by measurement of the Ca2+ influx in response to low [Na+]o. The color-coded traces in Fig. 3E show changes in the normalized Ca2+ signal (ΔF/F0) in the cells identified in Fig. 3, A–D. Using bracketed measurements, we recorded the Ca2+ influx under control conditions before (trial 1) and after (trial 3) testing the Ni2+ sensitivity (trial 2). Application of low [Na]o produced a higher percentage (78–79%) of Ni2+-sensitive Ca2+ influx, yielding ΔF/F0 = 1.12 ± 0.10 (n = 42) in the S cells, ΔF/Fo = 0.96 ± 0.13 (n = 31) in the MS cells, and no detectable Ni2+ sensitivity in the untransfected FlpIn-293 cells (Fig. 4, B and D, red bars).

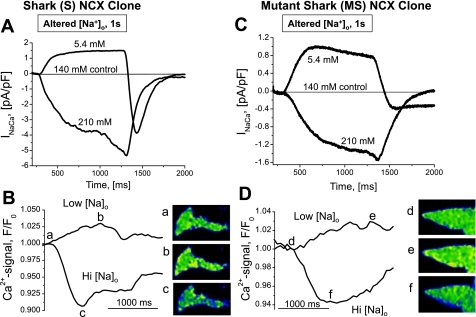

Although fluorescence imaging of Ca2+ signals in multiple nondialyzed fluo 4-AM-stained cells is useful for verifying and comparing levels of expression, detailed investigation of NCX regulation also calls for voltage-clamp experiments that allow measurements of INaCa and dialysis of an internal solution with known Ca2+ buffers. To be able to draw on both types of evidence, we investigated the relationship between Ca2+ signals and INaCa (Fig. 5). S cells (Fig. 5, A and B) or MS cells (Fig. 5, C and D) were voltage clamped at −60 mV and dialyzed with a solution containing 0.1 mM K5-fluo 4 and 0.02 mM Ca2+ to weakly buffer [Ca2+]i at 100 nM, with the intention of activating NCX without completely abolishing changes in Ca2+-dependent fluorescence. Rapid (1 s) application of solution with increased [Na+]o (210 mM) and reduced [Ca2+]o (0.5 mM) produced inward currents of −2.81 ± 0.72 pA/pF (n = 15) for the S cells (Fig. 5A) and −2.70 ± 0.64 pA/pF (n = 14) for the MS cells (Fig. 5C) that were accompanied by efflux of Ca2+, as judged from the accompanying gradual decline in Ca2+-dependent fluorescence (Fig. 5, B and D). Conversely, a reduction in [Na+]o to 5.4 mM produced an outward current of 1.90 ± 0.51 pA/pF (n = 15) for S cells (Fig. 5A) and 1.91 ± 0.46 pA/pF (n = 15) for MS cells (Fig. 5C) accompanied by a gradual increase in fluorescence indicative of Ca2+ influx (Fig. 5, B and D). The currents subsided or reversed direction after the cells were returned to standard solution, and the Ca2+-dependent fluorescence started to decline slowly to baseline levels. These results establish a link between the cumulative INaCa and the Ca2+ signals.

Fig. 5.

Activation of Ca2+ fluxes by changes in [Na]o produces matching changes in Na+/Ca2+ exchange current (INaCa; A and C) and Ca2+ signals (B and D) in weakly Ca2+-buffered voltage-clamped cells with stable expression of shark NCX (S cells; A and B) and mutant shark NCX (MS cells; C and D). Ca2+-influx and -efflux modes were activated, respectively, by reduction of [Na+]o (from 140 to 5.4 mM, by TEA-Cl substitution) or elevation of [Na+]o (from 140 to 210 mM, by Na+ addition) during reduction of [Ca2+] (from 5 to 0.5 mM) for 1-s intervals. Insets (a–f): fluorescence images at the indicated times and [Na+]o. {Voltage-clamped FlpIn-293 cells were held at −60 mV and dialyzed with internal solution, where intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) was buffered at 100 nM by 0.1 mM BAPTA and 0.1 mM K5-fluo 4 and 0.02 Ca2+; ratiometric normalization of images and color scale as in Fig. 2.}

We generally observed that the currents resulting from high and low [Na+]o crossed each other during reequilibration (Fig. 5, A and C). This is consistent with reversal of INaCa during the declining phase of the Ca2+ transients (Fig. 5, B and D). Similarly, a gradual decline in outward current was often observed during exposure to low [Na+]o (Fig. 5C). This finding is consistent with a slight reduction in the driving force of NCX caused by elevation of [Ca2+]i (Fig. 5D) (14). It appears less certain whether changes in driving force may explain the conspicuous, but quite variable, inward tail currents (−1.30 ± 0.92 pA/pF, n = 15) that were frequently observed when normal [Na+]o was reintroduced after exposure to low [Na+]o (Fig. 5A).

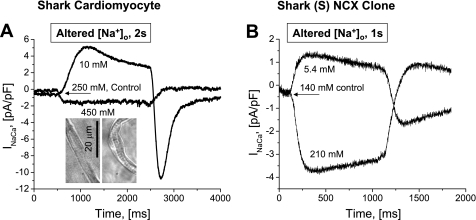

In the experiments illustrated in Fig. 6, we examined whether such tail currents might reflect [Ca2+]i-dependent activation of INaCa (19) or might be an artifact of the expression system. For this purpose, we compared voltage-clamp experiments where high concentrations of Ca2+ buffer were dialyzed into freshly dissociated shark cardiomyocytes (Fig. 6A) and S cells (Fig. 6B). The different ionic milieus of mammals and sharks called for the use of somewhat different Ca2+ buffers and methods of increasing or reducing [Na+]o (see methods; Fig. 6). An increase in [Na+]o generated similar inward INaCa in shark cardiomyocytes (−1.88 ± 0.24 pA/pF, n = 6) and S cells (−2.53 ± 0.92 pA/pF, n = 13). The outward current evoked by reduction of [Na+]o and the associated tail current were larger in shark cardiomyocytes [4.13 ± 0.89 pA/pF (n = 8) and −5.15 ± 1.68 pA/pF (n = 6)] than in S cells [1.74 ± 0.43 pA/pF and −0.62 ± 0.19 pA/pF (n = 13 each)]. Low- and high-Ca2+-buffering conditions produced similar, statistically insignificant, peak inward and outward current magnitudes after 1-s solution exchanges in S and MS cells. However, although the inward tail currents were present in Ca2+-buffered cells, the increased buffering, despite considerable scatter, appeared to have some suppressive effect (−1.30 ± 0.92 vs. −0.62 ± 0.19 pA/pF), suggesting a degree of Ca2+-dependent activation. This notion is supported by the findings that the inward tail currents were larger when 1) the Ca2+ signals were larger, 2) the outward INaCa decreased significantly in amplitude during the preceding exposure to low [Na+]o, and 3) the duration of this exposure was increased (1–5 s; data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Comparison of shark NCX in its native environment (A) and in mammalian expression system (B). In the different ionic milieus, high Ca2+-buffering and Na+-dependent activation of outward and inward INaCa were achieved by slightly different means: in freshly dissociated shark ventricular cardiomyocytes, [Ca2+]i ∼200 nM (10 mM EGTA + 6 mM Ca2+), [Na+]o was reduced from 250 to 10 mM (by Cs+ substitution), and [Na+]o was elevated from 250 to 450 mM (by urea replacement); in FlpIn-293 cells with stable expression of shark NCX, [Ca2+]i ∼100 nM (0.1 mM BAPTA + 5 mM EGTA + 2.66 mM Ca2+), [Na+]o was reduced from 140 to 5.4 mM (by TEA-Cl substitution), and [Na+]o was elevated from 140 to 210 mM (by Na+ addition coupled with reduction of [Ca2+]o from 5 to 0.5 mM). Insets in A: midsection of a spindle-shaped shark cardiomyocyte (∼100 μm long, 5–10 μm diameter, 75 ± 5 pF membrane capacitance, n = 8) that was held in position by the patch pipette but bent when a flow of standard shark Ringer solution was applied via a rapid perfusion system. [Voltage-clamped dialyzed cells were held at −60 mV; Ca2+ current (ICa) was blocked by 10 μM nifedipine.]

In summary, generation of NCX current by S and MS cells in a mammalian system is supported by Ni2+-sensitive Ca2+ fluxes and the simultaneously measured INaCa, which, in turn, has properties similar to those found in shark cardiomyocytes.

Regulation of Cloned Shark NCX by β-Adrenergic Stimulation

The bimodal characteristics of β-adrenergic regulation of shark NCX were identified initially (43) on the basis of voltage-clamp measurements of INaCa in freshly dissociated ventricular cells with minimal Ca2+ buffering. Here we tested whether the expressed shark NCX displays similar regulation independent of Ca2+ buffering or alterations in the reversal potential (ENaCa). Using nondialyzed S cells, we measured the Ni2+-sensitive Ca2+ influx before (Fig. 3E, trials 1–3) and after (Fig. 3F, trials 4–6) the cells had been exposed to 10 μM DBcAMP for 300 s. The stability of the cells was evaluated by monitoring the baseline fluorescence before each low-[Na+]o trial (Fig. 3E) and during the incubation with DBcAMP. As shown in Fig. 4, B and D, DBcAMP reduced the Ni2+-sensitive NCX Ca2+ influx by 75% in S cells (ΔF/F0 = 1.12 ± 0.10 and 0.28 ± 0.05 for control and DBcAMP, respectively, n = 20, P = 0.0025) and by 58% in MS cells (ΔF/Fo = 0.96 ± 0.06 and 0.40 ± 0.15 for control and DBcAMP, respectively, n = 3, P = 0.04). Control FlpIn-293 cells showed little Ni2+-sensitive Ca2+ influx or effect of DBcAMP (ΔF/Fo = 0.02 ± 0.04 and 0.01 ± 0.02 for control and DBcAMP, respectively, n = 9).

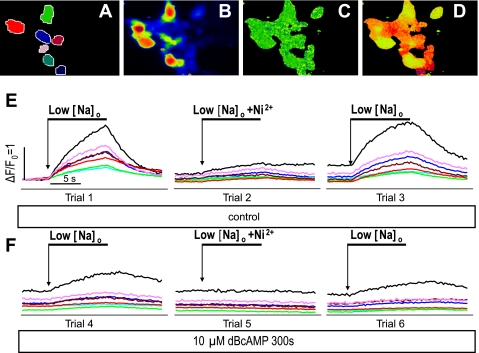

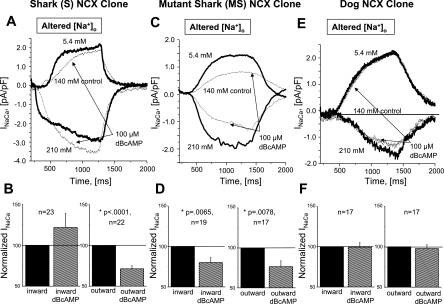

The effects of β-adrenergic modulation of S and MS cells were compared in parallel experiments, where changes in [Na+]o were used to activate INaCa in the outward or inward direction in voltage-clamped FlpIn-293 cells held at −60 mV (Fig. 7). As summarized in Fig. 7B, which shows data from high- and low-Ca2+-buffering experiments, DBcAMP reduced outward INaCa of S cells by 29 ± 4% (n = 21, P < 0.0001) but variably increased inward INaCa by 22 ± 18% (n = 23). In contrast, INaCa of MS cells was reduced in the outward (23 ± 8%, n = 17, P = 0.0078; Fig. 7D) and inward (20 ± 7%, n = 19, P = 0.0134) directions, whereas changes in INaCa of dog NCX were insignificant: inward current changed 1 ± 6%, and outward current changed 2 ± 5% (n = 17).

Fig. 7.

Different modalities of cAMP-dependent regulation of shark (S cells; A and B: bimodal), mutant shark (MS cells; C and D: unimodal), and dog (E and F: no regulation) cardiac NCX. A, C, and E: [Na+]o-dependent activation of outward and inward INaCa in voltage-clamped stably expressing cells dialyzed with high concentrations of Ca2+ buffers. Dotted traces were recorded after 180 s of incubation with 100 μM DBcAMP. B, D, and F: fractional changes in inward (left) and outward (right) INaCa determined from pooled experiments with cells where [Ca2+]i = 100 nM was established by dialysis of titrated Ca2+ buffers in high (0.1 mM BAPTA + 5 mM EGTA + 2.66 mM Ca2+) or low (0.1 mM BAPTA, 0.1 mM K5-fluo 4, and 0.02 mM Ca2+) concentrations. Each graph shows response in the presence of DBcAMP (hatched bars) relative to response before incubation (≡1; solid bars). Values are means ± SE for experiments with n cells. P values are based on paired t-tests. {For voltage-clamped (−60 mV) dialyzed stable FlpIn-293 (A–D) and HEK-293 (E and F) cells, [Na+]o was reduced from 140 to 5.4 mM (by TEA-Cl substitution) and [Na+]o was elevated from 140 to 210 mM (by Na+ addition coupled with reduction of [Ca2+]o from 5 to 0.5 mM).}

After separation of the data on the basis of Ca2+ buffering, we found that dialysis of extra Ca2+ buffers in S cells slightly altered the effects of DBcAMP, so that the suppression of outward INaCa was increased from 25 ± 8% (n = 8) to 31 ± 5% (n = 13), whereas the enhancement of inward INaCa was reduced from 42 ± 35% (n = 10) to 6 ± 18% (n = 13), for low- and high-Ca2+ buffering, respectively. Thus, although the enhancement of inward INaCa appears to be most pronounced in cells with low-Ca2+ buffering, bimodal regulation was invariably seen as predominant suppression of outward INaCa.

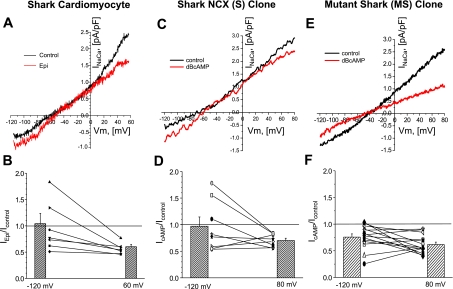

Effect of adrenergic stimulation on voltage dependence of INaCa.

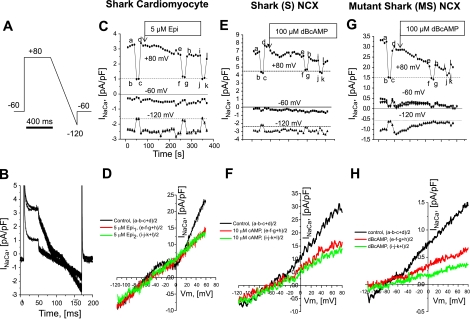

Using a ramp-clamp protocol (Fig. 8A) to measure the voltage dependence of INaCa (Fig. 8B), we compared the effects of β-adrenergic stimulation on S (Fig. 8, E and F) and MS (Fig. 8, G and H) cells with results from parallel experiments with freshly dissociated shark cardiomyocytes (Fig. 8, C and D). The ramp-clamp protocol was repeated at 10-s intervals, before and after β-adrenergic stimulation with 5 μM epinephrine (Fig. 8, C and D) or 100 μM DBcAMP (Fig. 8, E–H). Exposures to Ni2+ or Cd2+ were used to separate INaCa from residual current (Cl− and leak currents), which, in these matched experiments, remained stable during three consecutive tests (bc, fg, and jk and dashed lines in Fig. 8, C, E, and G). In addition, recordings were screened on the basis of the stability of currents measured at different potentials before adrenergic stimulation and at −60 mV (≅ENaCa) throughout the experiments.

Fig. 8.

cAMP-mediated regulation preferentially suppresses Ca2+-influx mode of NCX in shark ventricular myocytes (A–D) and S cells (E and F), whereas it suppresses influx and efflux modes of MS cells (G and H). A and B: ramp-clamp protocol used to measure membrane current before (a in B and C), during (b and c), and after (d) application of 5 mM Ni2+. C, E, and G: membrane current at +80, −60 (holding potential), and −120 mV recorded at 10-s intervals with 3 brief exposures to 5 mM Ni2+ and a long exposure to 5 μM epinephrine (Epi; C and D) or 100 μM DBcAMP (E–H). D, F, and H: current-voltage (I-V) relations for Ni2+-sensitive component of membrane current measured once before [control; (a − b − c + d)/2] and twice after {red; [(e − f − g + h)/2] and green [(i − j − k + l)/2] curves} β-adrenergic stimulation. Vm, membrane potential. [Voltage-clamped cells were dialyzed with high concentrations of Ca2+ buffers (see Fig. 6 legend).]

Detailed current-voltage (I-V) relations were constructed from four current traces (Fig. 8, B, C, E, and G) that were recorded immediately before (a), during (b and c), and after (d) rapid application of 5 mM Ni2+. From these traces, we obtained INaCa as the Ni2+-sensitive membrane current [(a − b − c + d)/2]. By relating the current measured at different times to simultaneous values of Vm during the ramp-clamp protocol, we constructed the I-V relation shown as “control” in Fig. 8, D (shark cardiomyocyte), F (S cell), and H (MS cell). The same procedure was used to measure I-V relations 2.5 min (e–h in Fig. 8, C, E, and G) and 4 min (i–l in Fig. 8, C, E, and G) after β-adrenergic stimulation. The I-V relations in Fig. 8D show that, in a native shark myocyte, epinephrine suppresses outward INaCa at +60 mV (Fig. 8F), leaving inward INaCa essentially unchanged from −120 mV to the only slightly altered ENaCa (−58 to −54 mV). The I-V relations in Fig. 8F for S cells show similar effects of DBcAMP: the outward INaCa was significantly reduced at positive potentials without significant changes of inward INaCa from −120 mV to the stable ENaCa (−60 mV). One noticeable difference is the dip in the control I-V relation of the shark cardiomyocyte at ∼0 mV (Fig. 8E), which is thought to represent residual ICa, since it disappeared in cardiomyocyte experiments, where 1–5 μM nifedipine was added to the perfusate and was never observed in the FlpIn-293 cell lines, probably reflective of the absence of significant ICa in HEK-293 cells. Interestingly, the same experiment in MS cells revealed a suppression of outward and inward INaCa. Although comparison of ENaCa of the shark (−62 ± 6 mV, n = 8) with ENaCa of the mutant shark (−46 ± 8 mV, n = 14) reveals a trend toward a slightly more positive reversal potential for the mutant shark, the difference between the two was not significant (P = 0.1517).

The ramp-clamp experiments uncovered a degree of variability similar to that of experiments with altered [Na+]o (cf. Figs. 8 and 9 with Fig. 7), where we found that the inward INaCa in some shark cardiomyocytes and S cells was actually enhanced by, rather than insensitive to, β-adrenergic stimulation (cf. Fig. 9, A and C and Fig. 8, D and F). The relative change of INaCa at different potentials was found to vary smoothly with the Vm and could be approximated by Boltzmann distribution [exp(−0.12 × FVm/RT)] (where F is Faraday's constant, R is gas constant, and T is absolute temperature Kelvin), except near ENaCa, where it was poorly defined. In contrast, the mutant shark NCX displayed the characteristic suppression pattern of outward and inward INaCa (Figs. 8H and 9F).

Fig. 9.

Bimodal β-adrenergic regulation of native (A and B) and cloned (C and D) shark NCX vs. unimodal suppression of mutant shark NCX (E and F). A and C: I-V relations of INaCa in high- and low-Ca2+-buffered cells, respectively, where epinephrine (A) or DBcAMP (C) decreased outward INaCa but increased inward INaCa. E: I-V relations of INaCa measured in a low-Ca2+-buffered mutant shark cell, where DBcAMP decreased outward and inward INaCa. B, D, and F: fractional changes in INaCa at Vm of −120 and +60 mV. Bars show average values of relative current [IEpi/IControl (B) and IDBcAMP/IControl (D and F)] based on individual experiments represented by symbols and connecting lines (n = 7 for shark ventricular myocytes, n = 8 for shark FlpIn-293 cells, and n = 14 for shark mutant FlpIn-293 cells). Closed symbols, strong Ca2+ buffering; open symbols, weak Ca2+ buffering.

Results from 7 native shark cardiomyocytes, 8 S cells, and 14 MS cells are quantified in Fig. 9, B, D, and F. The results from the shark cardiomyocytes showed that, on average, epinephrine did not change INaCa at −120 mV [ratio of epinephrine current (IEpi) to control current (IControl) = 1.04 ± 0.19, n = 7] but reduced the current at +60 mV by nearly one-half (IEpi/IControl = 0.60 ± 0.04, n = 7). ENaCa did not significantly change (from −52 ± 5 to −51 ± 4 mV, n = 9). An enhancement of INaCa at −120 mV was observed in two of seven cells.

Similarly, in the S cells, on average, DBcAMP did not change INaCa at −120 mV [ratio of cAMP current (IcAMP) to IControl = 0.97 ± 0.49 (SE), n = 8] but did significantly reduce INaCa at +80 mV (IcAMP/IControl = 0.7 ± 0.04, P = 0.0002, n = 8). ENaCa was not significantly altered (−62 vs. −63 mV, n = 8). Enhancement of INaCa at −120 mV was observed in three of eight cells.

In contrast, DBcAMP in the MS cells reduced INaCa at −120 mV (IEpi/IControl = 0.76 ± 0.06, n = 14) and reduced the current at +80 mV by nearly one-half (IEpi/IControl = 0.62 ± 0.05, n = 14). Again, ENaCa did not change significantly (−46 vs. −44 mV, n = 14, P = 0.1517).

The experiments with adrenergic agonists show that shark NCX displays a degree of bimodal regulation that 1) does not depend critically on Ca2+ buffering, 2) is reflected in Ca2+ signals and INaCa, 3) is present whether the Ca2+-influx and -efflux modes are activated by changing [Na+]o or Vm, and 4) have remarkably similar effects on the voltage dependence of INaCa in the mammalian expression system and native shark cardiomyocytes. Loss of bimodal regulation in the MS cells suggests that the mutant's deleted unique molecular motif plays a critical role in cAMP-mediated regulatory activity.

DISCUSSION

Here we cloned the shark cardiac NCX, expressed the shark clone in mammalian cell lines, and studied its regulation. The bimodal characteristics of the cloned shark's cAMP-mediated regulation resembled those of freshly dissociated shark ventricular cardiomyocytes, persisted with different degrees of intracellular Ca2+ buffering, and were changed to unimodal inhibition after deletion-mutation of a unique shark region 2 insert.

Cells from sharks and mammals differ greatly with respect to osmolarity (∼900 vs. 300 mosM) and [Na+]i (∼60 vs. ∼5–8 mM), and these values, as well as [Ca2+]i, are unlikely to change significantly during the relatively brief (3–5 min) applications of β-adrenergic agonists, especially in cells that are dialyzed with Ca2+-buffered internal solutions via low-resistance (2–5 MΩ) patch pipettes. These observations suggest that bimodal regulation of shark NCX is an inherent property of this protein and is unlikely to be mediated by the conventional types of [Ca2+]i-dependent activation (19) or [Na+]i-dependent inactivation (20). Our findings extend previous studies of mammalian and amphibian cardiac NCXs that have shown gain or loss of β-adrenergic regulatory properties after insertion and deletion of specific molecular motifs (25).

Characteristic Features of the Amino Acid Sequence of Shark Cardiac NCX

The present study was undertaken to explore whether the bimodal cAMP-dependent regulation of shark NCX (43) depends on specific molecular motifs, such as the 29-bp block insertion encoding a P loop in frog NCX (17), or unique cellular environmental factors, such as osmolarity, ionic concentration, and AKAPs. The determined sequence of shark NCX may be characterized as “cardiac type,” since it includes a close equivalent corresponding to the stretch of amino acids coded by exons A, C, D, E, and F of NCX1.1 of higher vertebrates. Redundant sequencing of shark cardiac mRNAs in cloned and PCR-derived fragments from several samples of shark heart (see Supplemental Fig. 1) produced no signs of a P loop (nucleotide-binding Walker A sequence, GxxxxxGKT) similar to that of frog cardiac NCX. In fact, the current genomic information suggests that the P loop of frog derives from extension of exon E, and although such an extension could also produce a P loop in some other species (Homo sapiens, Pan troglodytes, Macaca mulatta, Bos taurus, and Rattus norvegicus), this has not been observed and would generally corrupt the reading frame. Inasmuch as shark tissue collection is typically restricted to the summer season, a remote possibility remains that a shark NCX variant with a P loop may appear when the animals are not readily accessible. The P-loop mechanism has only been observed in frog (17, 38).

The most conspicuous features of shark cardiac NCX, which set it apart from cardiac-specific isoforms of other organisms, are the two A/P-rich block insertions in the long cytoplasmic loop. The longer insert (region 2) is added to CBD1 at a location corresponding to the location of the variable spliced exons (A–F) within CBD2 (Fig. 1). This provides some similarity between exon X and the shark region 2 insert, since both may extend a flexible linker sequence (11, 35) and provide or modulate specific binding sites. More extensive experiments are required to determine whether and to what extent the shark region 2 insert and the variably spliced region may share a common functionality.

The shorter shark insert (region 1) is found at a location where NCX of C. intestinalis also has some additional amino acids compared with higher vertebrates (Fig. 1; see Supplemental Fig. 2). The structure of this region of NCX is not known, but sequence similarity suggests that the shark region 1 insert extends an unstructured loop that originates from the first (segment A) α-helix of a catenin-like domain (44) and circumscribes its second (segment B) α-helix (Fig. 1, C and D).

In light of these observations, it is possible that the long cytoplasmic loop is organized as an assemblage of modular components with additional flexible linker sequences, which could provide a degree of flexibility that allows binding of regulatory moieties (e.g., A-kinase-anchoring proteins and PKA catalytic unit) or impedes the activity of phosphatases, thus explaining difficulties in crystallizing the entire NCX molecule (15).

Expression of Shark and Mutant Shark Cardiac NCX in Mammalian Cell Lines

The expression of full-length cDNAs of shark and mutant shark NCX in HEK-293 and FlpIn-293 cells was verified and compared with each other as well as appropriate controls. The two mammalian expression systems were shown to have only small endogenous Ca2+-influx pathways, consistent with their greatly reduced Ca2+ transients (Fig. 4). To quantify the NCX-generated currents and Ca2+ fluxes, millimolar concentrations of Ni2+ or Cd2+ were used to block NCX rapidly and reversibly (Figs. 2, 3, and 8, C, E, and G; see Supplemental Fig. 3). The Ni2+-insensitive residual Ca2+ fluxes were larger in HEK-293 (Figs. 2 and 4) than in FlpIn-293 (Figs. 3 and 4) cells, regardless of the type of NCX transfected, inasmuch as similar results were found in dog, shark, and mutant shark NCXs.

Normalization of INaCa relative to the membrane capacitance showed that the level of stable expression of shark and mutant shark NCX in FlpIn-293 cells was comparable to that found in freshly dissociated cardiomyocytes (2–3 pA/pF; Fig. 8, D, F, and H and Fig. 9, A, C, and E). Successful expression of shark NCX is also supported by the similarity of regulatory effects of adrenergic agonists in mammalian expression systems and native shark cardiomyocytes (Figs. 8 and 9), as well as by the large inward tail currents following brief intervals of partial Na+ withdrawal (Figs. 5A and 6B).

Inward Tail Currents

Our finding that readmission of normal extracellular Na+, after 1–2 s of partial Na+ deprivation, produced such large inward INaCa in cells with heterologous expression of NCX (Figs. 5A and 6B) or in native shark cardiomyocytes (Fig. 6A) is novel. These currents are larger than the inward currents that are typically measured at hyperpolarizing potentials and are of a magnitude that could provide sufficient Ca2+ efflux to cause rapid relaxation. We estimate that a charge transfer via INaCa of ∼200 pF in shark cells (∼10 μm diameter, ∼100 μm long) with a volume of ∼8 pl in 1 s would change the total intracellular Ca2+ content by ∼125 μM [(200 × 10−9 charge/s × 1 s)/(8 × 10−12 liters × 2 × 105 charge/M)], which is enough to saturate the myofilaments (40) or significantly alter ENaCa in shark cells with low concentrations of Ca2+ buffers (43). In FlpIn-293 cells, Ca2+ fluxes of that order of magnitude are consistent with the observed Ca2+ signals (Fig. 5) and the strong suppression of tail currents on addition of 5 mM EGTA to the internal solution (Fig. 5 vs. Fig. 6B). It is surprising, therefore, that the tail currents remained strong in shark cardiomyocytes with high concentrations of Ca2+ buffers (Fig. 6B vs. Ref. 43), where effective dialysis was supported by the stability of the measured ENaCa during β-adrenergic stimulation. This suggests that the tail currents may reflect changes in ENaCa and Ca2+-dependent activation of INaCa (19), as well as an enhancement of the Ca2+-efflux mode similar to that observed with β-adrenergic stimulation (Fig. 8).

Adrenergic Regulation of Shark and Mutant Shark NCX

cAMP-dependent regulation of shark NCX was evoked in shark cardiomyocytes by β-adrenergic agents (epinephrine or isoproterenol). However, in HEK-293 cells, which have been reported to lack β-receptors and to have stunted β-adrenergic responses, cAMP or its nonhydrolyzable analog (DBcAMP) was used to activate PKA directly. As mentioned above, sharks and mammals provide distinctly different ionic milieus and may have different baseline PKA and phosphatase activities. Also, it is possible that mammalian expression systems may not incorporate shark NCX into the cytoskeleton in the same way as in shark cardiomyocytes or express A-kinase-anchoring proteins, which are effective across the vertebrate species. Under these conditions, it is significant that the cAMP-dependent regulation of the expressed shark NCX was indistinguishable from that found in its native environment (Figs. 8 and 9).

In critical tests of β-adrenergic modulation (Figs. 7–9), we used internal dialysis to impose fixed [Na+]i and [Ca2+]i to abolish or minimize the allosteric intracellular effects of these ions (19, 20). In fact, significant Na+-lag effects are unlikely to occur during brief (10 s) activation of NCX constructs, even in nondialyzed mammalian cells (Figs. 1–4) or in the intact shark myocardium, where baseline [Na+]i is ∼50 mM. The possibility of significant changes in [Ca2+]i was excluded by use of high-Ca2+ buffers, brief voltage-clamp depolarization (Fig. 8A), and screening of the data based on the stability of ENaCa (Fig. 8, C, E, and G and Fig. 9, A, C, and E). It is unlikely, therefore, that the effects of cAMP-dependent regulation are mediated by changes in [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i.

The rundown of NCX during experiments is a concern, in part, because we rarely achieved complete washout of the cAMP-dependent effects. However, the absence of cAMP regulatory effects on dog NCX under the same experimental conditions (Fig. 7) suggests that the cAMP-dependent effects are specific to the shark NCX and are not a result of rundown or the experimental paradigm. In addition, any potential rundown does not detract from the observation that the efflux mode of shark NCX is suppressed significantly more than the less sensitive, or even enhanced, influx mode. This finding is consistently supported by experiments with intact (Figs. 3 and 4) or dialyzed cells (Fig. 7, A and B, Fig. 8, E and F, and Fig. 9C), regardless of Ca2+ buffering (Figs. 5–9) and/or INaCa activation mechanism (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 vs. Fig. 8, E and F and Fig. 9, C and D). In fact, voltage-clamp experiments with shark cardiomyocytes with minimal-Ca2+ buffering (43) and high-Ca2+ buffering (Fig. 8, C and D and Fig. 9, A and B) closely reflect the shark clone experimental findings and support the concept of bimodal regulation.

The unique bimodal regulation characteristics of shark cardiac NCX were abolished on deletion of the shark region 2 insert. Although deletion of the insert did not change the ability of the mutated NCX to produce INaCa (Figs. 4, 5, 7, 8, and 9), it did affect the cAMP regulatory characteristics (Figs. 7–9), producing a unimodal suppression of the influx and efflux of INaCa very similar to that in the frog (17). This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that the presence and modality of adrenergic regulation of NCX depend on molecular motifs that are variably expressed in different vertebrate species.

Physiological Implications of Bimodal Regulation of NCX

The cardiac NCX in shark and frog operates at low temperature and heart rate in cells where ICa is also under β-adrenergic control but the SR is nonfunctional (26, 29, 33). Thus excitation-contraction coupling is controlled predominantly by sarcolemmal Ca2+ fluxes, of which the influx is mediated by the Ca2+ channel and NCX, but the efflux is controlled by the NCX alone to generate relaxation. In contrast, tidal Ca2+ fluxes in the more rapidly beating adult mammalian myocardium are generated primarily by the SR, where the ICa-triggered release via ryanodine receptors and the Ca2+ sequestration by sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase are subject to β-adrenergic modulation. In contemplating these differences, it may be relevant that the inward INaCa generated by NCX during relaxation may cause depolarization and arrhythmias (39); this liability may be expected to increase when NCX is required to operate very fast or to remove a large fraction of the activator Ca2+ from the cytosol. These facts may explain the adaptive value of the large SR-recirculation fraction (>90%) (1) in the very rapidly beating hearts of rodents and the prevalence of arrhythmias in cardiac diseases where SR function is compromised and the expression of NCX is increased (32, 36).

Conversely, cAMP-dependent enhancement of inward INaCa in shark may be essential to achieve rapid Ca2+ efflux and diastolic relaxation of the shark ventricle when the heart rate is increased by adrenergic stimulation of ICa. A simultaneous adrenergic-induced suppression of Ca2+-influx mode of NCX may serve to limit NCX-mediated Ca2+ influx during depolarization, so that force development is controlled primarily by the phosphorylated L-type Ca2+ channel during the initial part of the plateau of the cardiac action potential. Together, these two Ca2+-transporting proteins may provide a regulation that is similar to that which, in mammals, is achieved with smaller transsarcolemmal Ca2+ fluxes and Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from the SR.

We found that the degree of bimodal regulation of shark cardiac NCX was quite variable, and the underlying causes remain to be determined. However, it is possible that although the Ca2+-influx and -efflux modes of shark cardiac NCX are governed by a single reversal potential, they may be regulated independently. Under stressful conditions, this might provide the means by which the cell prevents Ca2+ overload and triggering of aberrant excitation by inward INaCa. Intriguingly, similar flexible control mechanisms may be latent or inducible in mammalian hearts.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants RO1 HL-16152 (M. Morad) and RO1 HL-73929 (R. Day).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Katrine Kiilerich-Hansen, Young H. Lee, and Autumn Griffin for technical support.

The opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of Defense, or the US Federal Government (R. Day).

Preliminary reports of this work have been published in abstract form (8, 12, 13, 23, 41).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi-Akahane S, Cleemann L, Morad M. Cross-signaling between L-type Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors in rat ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol 108: 435–454, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker PF, Blaustein MP, Hodgkin AL, Steinhardt RA. The influence of calcium on sodium efflux in squid axons. J Physiol 200: 431–458, 1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry WH, Bridge JH. Intracellular calcium homeostasis in cardiac myocytes. Circulation 87: 1806–1815, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bers DM, Bridge JH. Relaxation of rabbit ventricular muscle by Na-Ca exchange and sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium pump. Ryanodine and voltage sensitivity. Circ Res 65: 334–342, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besserer GM, Ottolia M, Nicoll DA, Chaptal V, Cascio D, Philipson KD, Abramson J. The second Ca2+-binding domain of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger is essential for regulation: crystal structures and mutational analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 18467–18472, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaustein MP, Lederer WJ. Sodium/calcium exchange: its physiological implications. Physiol Rev 79: 763–854, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bridge JH, Smolley JR, Spitzer KW. The relationship between charge movements associated with ICa and INa-Ca in cardiac myocytes. Science 248: 376–378, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleemann L, Belmonte S, Solvadottir AE, Andreasen G, Pihl MJ, Morad M. Bimodal adrenergic regulation of Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in Ca2+-buffered native ventricular myocytes from the spiny dogfish shark (Squalus acanthias). Bull Mount Desert Island Biol Lab Salsbury Cove ME 45: 27–30, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleemann L, Morad M. Role of Ca2+ channel in cardiac excitation-contraction coupling in the rat: evidence from Ca2+ transients and contraction. J Physiol 432: 283–312, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Condrescu M, Gardner JP, Chernaya G, Aceto JF, Kroupis C, Reeves JP. ATP-dependent regulation of sodium-calcium exchange in Chinese hamster ovary cells transfected with the bovine cardiac sodium-calcium exchanger. J Biol Chem 270: 9137–9146, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cronan JE Jr. Interchangeable enzyme modules. Functional replacement of the essential linker of the biotinylated subunit of acetyl-CoA carboxylase with a linker from the lipoylated subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem 277: 22520–22527, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Day RM, Janowski E, Movafagh S, Heyrana K, Lee YH, Nagase H, Kraev A, Roder JD, Laney SJ, Kiilerich-Hansen K, Cleemann L, Morad M. Cloning and functional expression of the cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger of the spiny dogfish shark (Squalus acanthias). Bull Mount Desert Island Biol Lab Salsbury Cove ME 45: 29–32, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Day RM, Nagase H, Lee YH, Kraev A, Cleemann L, Morad M. Sequencing the cardiac Na-Ca exchanger of the spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias). Bull Mount Desert Island Biol Lab Salsbury Cove ME 53: 80–83, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan J, Shuba YM, Morad M. Regulation of cardiac sodium-calcium exchanger by β-adrenergic agonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 5527–5532, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hale CC, Bossuyt J, Hill CK, Price EM, Schulze DH, Lederer JW, Poljak R, Braden BC. Sodium-calcium exchange crystallization. Ann NY Acad Sci 976: 100–102, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han X, Ferrier GR. Contribution of Na+-Ca2+ exchange to stimulation of transient inward current by isoproterenol in rabbit cardiac Purkinje fibers. Circ Res 76: 664–674, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He LP, Cleemann L, Soldatov NM, Morad M. Molecular determinants of cAMP-mediated regulation of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger expressed in human cell lines. J Physiol 548: 677–689, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hilge M, Aelen J, Vuister GW. Ca2+ regulation in the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger involves two markedly different Ca2+ sensors. Mol Cell 22: 15–25, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hilgemann DW, Collins A, Matsuoka S. Steady-state and dynamic properties of cardiac sodium-calcium exchange. Secondary modulation by cytoplasmic calcium and ATP. J Gen Physiol 100: 933–961, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilgemann DW, Matsuoka S, Nagel GA, Collins A. Steady-state and dynamic properties of cardiac sodium-calcium exchange. Sodium-dependent inactivation. J Gen Physiol 100: 905–932, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilgemann DW, Nicoll DA, Philipson KD. Charge movement during Na+ translocation by native and cloned cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Nature 352: 715–718, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwata T, Kraev A, Guerini D, Carafoli E. A new splicing variant in the frog heart sarcolemmal Na-Ca exchanger creates a putative ATP-binding site. Ann NY Acad Sci 779: 37–45, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janowski E, Day RM, Kraev A, Cleemann L, Morad M. Structure and function of the cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger of the spiny dogfish shark (Squalus acanthias). Bull Mount Desert Island Biol Lab Salsbury Cove ME 46: 29–32, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lederer WJ, Berlin JR, Cohen NM, Hadley RW, Bers DM, Cannell MB. Excitation-contraction coupling in heart cells. Roles of the sodium-calcium exchange, the calcium current, and the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Ann NY Acad Sci 588: 190–206, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuoka S, Nicoll DA, Hryshko LV, Levitsky DO, Weiss JN, Philipson KD. Regulation of the cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger by Ca2+. Mutational analysis of the Ca2+-binding domain. J Gen Physiol 105: 403–420, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morad M, Orkand RK. Excitation-concentration coupling in frog ventricle: evidence from voltage-clamp studies. J Physiol 219: 167–189, 1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morad M, Suzuki YJ. Ca2+-signaling in cardiac myocytes: evidence from evolutionary and transgenic models. Adv Exp Med Biol 430: 3–12, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morad M, Tung L. Ionic events responsible for the cardiac resting and action potential. Am J Cardiol 49: 584–594, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nabauer M, Morad M. Modulation of contraction by intracellular Na+ via Na+-Ca2+ exchange in single shark (Squalus acanthias) ventricular myocytes. J Physiol 457: 627–637, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicoll DA, Longoni S, Philipson KD. Molecular cloning and functional expression of the cardiac sarcolemmal Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. Science 250: 562–565, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicoll DA, Sawaya MR, Kwon S, Cascio D, Philipson KD, Abramson J. The crystal structure of the primary Ca2+ sensor of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger reveals a novel Ca2+ binding motif. J Biol Chem 281: 21577–21581, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Rourke B, Kass DA, Tomaselli GF, Kaab S, Tunin R, Marban E. Mechanisms of altered excitation-contraction coupling in canine tachycardia-induced heart failure. I. Experimental studies. Circ Res 84: 562–570, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Page SG, Niedergerke R. Structures of physiological interest in the frog heart ventricle. J Cell Sci 11: 179–203, 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perchenet L, Hinde AK, Patel KC, Hancox JC, Levi AJ. Stimulation of Na/Ca exchange by the β-adrenergic/protein kinase A pathway in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes at 37°C. Pflügers Arch 439: 822–828, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perham RN Swinging arms and swinging domains in multifunctional enzymes: catalytic machines for multistep reactions. Annu Rev Biochem 69: 961–1004, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pogwizd SM, Bers DM. Na/Ca exchange in heart failure: contractile dysfunction and arrhythmogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci 976: 454–465, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reuter H, Seitz N. The dependence of calcium efflux from cardiac muscle on temperature and external ion composition. J Physiol 195: 451–470, 1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shuba YM, Iwata T, Naidenov VG, Oz M, Sandberg K, Kraev A, Carafoli E, Morad M. A novel molecular determinant for cAMP-dependent regulation of the frog heart Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. J Biol Chem 273: 18819–18825, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sipido KR, Bito V, Antoons G, Volders PG, Vos MA. Na/Ca exchange and cardiac ventricular arrhythmias. Ann NY Acad Sci 1099: 339–348, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solaro RJ, Wise RM, Shiner JS, Briggs FN. Calcium requirements for cardiac myofibrillar activation. Circ Res 34: 525–530, 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tong X, Cleemann L, Morad M. Partial sequencing of the cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger of the spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias). Bull Mount Desert Island Biol Lab Salsbury Cove ME 42: 115–116, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Towle DW, Smith CM. Expressed Sequence Tags in a Normalized cDNA Library Prepared From Multiple Tissues of Adult Shark, Squalus acanthias. Salsbury Cove, ME: Marine DNA Sequencing and Analysis Center, 2004.

- 43.Woo SH, Morad M. Bimodal regulation of Na+-Ca2+ exchanger by β-adrenergic signaling pathway in shark ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 2023–2028, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang J, Dokurno P, Tonks NK, Barford D. Crystal structure of the M-fragment of α-catenin: implications for modulation of cell adhesion. EMBO J 20: 3645–3656, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.