Abstract

Motivation: Some present day species have incurred a whole genome doubling event in their evolutionary history, and this is reflected today in patterns of duplicated segments scattered throughout their chromosomes. These duplications may be used as data to ‘halve’ the genome, i.e. to reconstruct the ancestral genome at the moment of doubling, but the solution is often highly nonunique. To resolve this problem, we take account of outgroups, external reference genomes, to guide and narrow down the search.

Results: We improve on a previous, computationally costly, ‘brute force’ method by adapting the genome halving algorithm of El-Mabrouk and Sankoff so that it rapidly and accurately constructs an ancestor close the outgroups, prior to a local optimization heuristic. We apply this to reconstruct the predoubling ancestor of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida glabrata, guided by the genomes of three other yeasts that diverged before the genome doubling event. We analyze the results in terms (1) of the minimum evolution criterion, (2) how close the genome halving result is to the final (local) minimum and (3) how close the final result is to an ancestor manually constructed by an expert with access to additional information. We also visualize the set of reconstructed ancestors using classic multidimensional scaling to see what aspects of the two doubled and three unduplicated genomes influence the differences among the reconstructions.

Availability: The experimental software is available on request.

Contact: sankoff@uottawa.ca

1 INTRODUCTION

Whole genome doubling (WGD) is a rare but important type of evolutionary event, often giving rise to major new lineages. In its various forms it has occurred across the eukaryotic spectrum, from the pathogenic protist Giardia to the ancestor of brewer's yeast, to most of the plant lineages, to several insect species, to the salmonid fishes, to amphibians and even to mammalian species.

WGD is followed, over evolutionary time, by genome rearrangement through intra- and interchromosomal movement of genetic material. The phylogenetic study of synteny, gene order and chromosomal evolution becomes blocked because of the extraordinarily high rates of paralogy in the species descended from the WGD compared to sister species that diverged before the WGD. If we could infer the ancestral genome that underwent the WGD, this difficulty would be resolved. Thus the genome halving problem is to reconstruct the ancestral genome on the basis of a decomposition of the present day genome into a set of apparently duplicated blocks of genes or DNA sequence dispersed among the chromosomes.1 A linear-time algorithm to find the ancestral genome that minimizes the genomic distance to the present day genome has been available for some time (El-Mabrouk and Sankoff, 2003; El-Mabrouk et al., 1999). Unfortunately, the solution to the combinatorial optimization problem is not always directly interpretable as a solution to the evolutionary biology problem. First, the algorithmic result suffers from severe non-uniqueness. Second, in common with most methods of inferring history, we have no direct way to verify if the answer is correct. Our goal is to counteract these problems, first by guiding the reconstruction by one or more reference, or outgroup, genomes and second, by checking our results for a particular dataset against an ancestor genome manually reconstructed by an expert.

If our guided reconstruction method were to be feasible and accurate it could have wide application. One or more descendants of a WGD event co-occur with unduplicated sister species in many phylogenies. This is most prevalent among plants where, for example, the poplars and willows descend from a common WGD, while the closely related eurosid angiosperms like papaya diverged before this event, but it also occurs in yeast, where brewer's yeast and several sister species share an origin in an ancestral WGD, while other closely related species have earlier divergence dates, in fish, where the salmonid species like trout and salmon originate in a WGD event after diverging from the related osmerid fish, in mammals, where some genera of viscacha rodents share a WGD history while their relationship with very similar octodontids predates this. In protists, the important pathogen genus Giardia has undergone a form of WGD, while the related enteromonad parasites have not, though this may be due to a post-WGD loss rather than an early divergence. This very partial list of examples emphasizes species whose genomes have been sequenced or for which serious sequencing projects are underway or are being actively promoted.

We first explored the idea of guided reconstruction for the ancestral doubled genome of the maize (Zea mays) genome, with the rice (Oryza sativa) and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) genomes2 as outgroups (Zheng et al., 2006). Our strategy was to generate all the 1.5×106 solutions to the genome halving problem for the maize genome, and to identify the subset, containing 10–20 solutions that have a minimum rearrangement distance with the rice (or sorghum) genome. We followed this with a local improvement heuristic searching outside the immediate set of optimal halving solutions to find the genome A that minimizes the sum of the distance between the doubled form A⊕A and present day maize plus the distance between rice (or sorghum) and the predoubling form A.

While this approach was feasible with the 34 doubled blocks in maize, present in one copy in each outgroup, the heuristic search step was time consuming, given that the starting points were relatively far from optimal. Then we attempted to reconstruct the ancient doubled yeast genome from which Saccharomyces cerevisiae is descended, guided simultaneously by both of the undoubled outgroup genomes Ashbya gossypii and Kluyveromyces waltii (Sankoff et al., 2007). In these data the number of doubled genes we used was an order of magnitude greater than the number of blocks in the cereals data, and the number of solutions to the halving problem astronomical. It is not feasible to exhaustively search the halving solutions to find those that are closest to the outgroups, to say nothing of the heuristic search step. Instead we tried working with a sample of halving solutions, hoping to generate at least one initialization leading to a good solution. It was not clear, however, how large the sample should be, or how to validate the results, since the local optima found in that study remained fairly far apart, as measured by genomic distance.

The facts that halving guided by a single outgroup involves only two genomes, and that both of its component parts, halving and distance calculation, are basically linear time, suggests that this problem might be susceptible to a polynomial-time analysis, in contrast to problems such as the ‘median problem’ for three or more genomes, which are NP-hard (Bryant, 1998; Caprara, 2003; Pe'er and Shamir, 1998). We dispose of this hope at the outset, by showing that the simplest problem of halving guided by one outgroup is NP-hard.

Nevertheless, in the ensuing sections, we seek to replace the ‘brute force’ approach of generating unconstrained halving solutions first, i.e. before taking into consideration the outgroup genome(s). Instead, we inject all pertinent information derivable from the outgroup(s) into the halving algorithm, influencing hitherto arbitrary choices in that algorithm so that the halving solution is guided towards the outgroup(s).

We analyze data on two yeasts descended from the same doubling event, S.cerevisiae and Candida glabrata, to try to reconstruct the original doubled genome. Three related outgroup species are currently available in the Yeast Gene Order Browser (YGOB, Byrne and Wolfe, 2005): A.gossypii, K.waltii and Kluyveromyces lactis. YGOB also furnishes an estimate of the ancestral doubled genome painstakingly reconstructed by Jonathan Gordon on the basis of multiple sources of information.

Our new algorithm greatly improves the accuracy of our results, while drastically reducing the computational effort, both in generating halving solutions and in the local optimization search. We compare this new approach to the sampling approach, with and without the local optimization step, from the viewpoints of the objective function value obtained and computing time. We apply our method to all combinations of the two descendants of the doubled ancestor and four single genomes, the three species already mentioned plus Gordon's manually reconstructed ancestor.

We also use data-analytic methods to compare our inferred predoubling genomes to each other and to the Gordon construct.

2 PROBLEM STATEMENT

Although the idea of guided genome halving is not difficult, the prerequisite for understanding the analysis is to have some knowledge of standard genome rearrangement problems, namely genomic distance, genome halving and genome median. We can only sketch these in Sections 2.2, 2.3 and 2.4 before enunciating the guided genome halving (GGH) problems in Section 2.5. In Section 3, we discuss the algorithms for these problems.

2.1 Genomes and rearrangement operations

A genome G is represented by a set of strings (called {g{11,..,g1n1,..,gχ1,..,gχnχ, where n=n1+···+nχ and {|g..|}={1, …,n}; i.e. each integer i∈{1, …,n}, representing a gene or other marker, appears exactly once in the genome and may have either positive or negative polarity. The biologically motivated operations generally include3 inversions (implying as well change of sign, i.e. change of strand) of chromosomal segments, e.g. h1 ···hu ···hv ···hm→h1 ···−hv ···−hu ···hm, and reciprocal translocations, e.g. h1 ···hu ···hl, k1 ···kv ···km→h1 ···kv ···km, k1 ···hu ···hl.

2.2 Genomic distance

The genome rearrangement distance d(G, H) is defined to be the minimum number of operations necessary to convert one genome G into another H.

The breakpoint distance—We say there is a ‘shared adjacency’ if the signed integer gi, j+1 immediately follows gi, j on a chromosome in H as well as on the i-th chromosome in G, or if −gij follows −gi, j+1 in H. There are also shared adjacencies if gi1 or −gini are first terms on chromosomes in H or if gini or −gi1 are last terms on chromosomes in H. Then if G and H have the same number of chromosomes χ, the breakpoint distance dB(G,H) is defined to be n+χ—the number of shared adjacencies.

2.3 Genome halving

Let T be a genome consisting of ψ chromosomes and 2n genes  , dispersed in any order on the chromosomes. For each i, we call

, dispersed in any order on the chromosomes. For each i, we call  and

and  ‘duplicates’, but there is no particular property distinguishing all elements of the set of

‘duplicates’, but there is no particular property distinguishing all elements of the set of  in common from all those in the set of

in common from all those in the set of  A potential ‘doubled ancestor’ of T is written A′⊕A′′, and consists of 2χ chromosomes, where some half (χ) of the chromosomes, symbolized by the A′, contains exactly one of

A potential ‘doubled ancestor’ of T is written A′⊕A′′, and consists of 2χ chromosomes, where some half (χ) of the chromosomes, symbolized by the A′, contains exactly one of  or

or  for each i=1, …,n. The remaining χ chromosomes, symbolized by the A′′, are each identical to one in the first half, in that where

for each i=1, …,n. The remaining χ chromosomes, symbolized by the A′′, are each identical to one in the first half, in that where  appears on a chromosome in the A′,

appears on a chromosome in the A′,  appears on the corresponding chromosome in A′′, and where

appears on the corresponding chromosome in A′′, and where  appears in A′,

appears in A′,  appears in A′′. We define A to be either of the two halves of A′⊕A′′, where the superscript (1) or (2) is suppressed from each

appears in A′′. We define A to be either of the two halves of A′⊕A′′, where the superscript (1) or (2) is suppressed from each  or

or  . These χ chromosomes, and the n genes they contain, a1,…,an constitute a potential ‘doubled ancestor’ of T.

. These χ chromosomes, and the n genes they contain, a1,…,an constitute a potential ‘doubled ancestor’ of T.

The genome halving problem for T is to find an A for which some d(A′⊕A′′, T) is minimal.

2.4 The median problem

Let P,Q and R be three genomes on the same set of n genes. The rearrangement median problem is to find a genome M such that d(P,M)+d(Q,M)+d(R,M) is minimal. The breakpoint median problem is to find a genome M such that dB(P,M)+dB(Q,M)+dB(R,M) is minimal.

2.5 Guided genome halving

As in Section 2.3, let T be genome consisting of ψ chromosomes and 2n genes  , dispersed in any order on the chromosomes, where for each i, genes

, dispersed in any order on the chromosomes, where for each i, genes  and

and  are duplicates. Any genome R is a reference or outgroup genome for T if it contains the n genes a1,…,an.

are duplicates. Any genome R is a reference or outgroup genome for T if it contains the n genes a1,…,an.

There are a number of different formulations possible for GGH, depending on the genomic distance used, and the number of outgroups doing the guiding. Here we will study the cases of one outgroup (Zheng et al., 2006) and two outgroups (Sankoff et al., 2007), using the genomic distance d defined in Section 2.2, and we will also analyze the complexity of the one outgroup problem in the context of the breakpoint distance dB.

Let R be a reference genome for T. The GGH problem with one outgroup is to find (an estimated ancestral) genome A such that some d(R,A)+d(A′⊕A′′,T) is minimal. Let R1 and R2 be two reference genomes for T. The GGH problem with two outgroups is to find A and a median genome M such that some d(R1,M)+d(R2,M)+d(A,M)+d(A′⊕A′′,T) is minimal.

3 ALGORITHMS FOR GENOME DISTANCE, GENOME HALVING AND THE GENOME MEDIAN

3.1 Distance

Rearrangement algorithms (Tesler, 2002) can be formulated in terms of the bi-colored ‘breakpoint graph’, where each end (either 5′ or 3′) of a gene in genome G is represented by a vertex joined by a black edge to the vertex for adjoining end of the adjacent gene, and these same ends, represented by the same 2n vertices in the graph, are joined by gray edges determined by the adjacencies in genome H. In addition, if G has χ chromosomes, assuming without loss of generality that this is at least as many as H, each vertex representing a first or last term of some chromosome in G only is connected by a black edge to an individual ‘cap’, or dummy, vertex so that there are 2n+2χ vertices in all. The breakpoint graphs necessarily consist of disjoint alternating color cycles and/or paths, and it can be shown that, with some rare, easily identifiable exceptions, d(G,H)=n+χ−c−Π, where c is the number of cycles and Π the number of paths terminating in at least one cap. Calculating the distance can be done in time linear in n.

The actual operations, d(G,H) in number, may be reconstructed by successively choosing certain large cycles and paths in the breakpoint graph to split into two, corresponding to a reversal or translocation, until there are n−χ cycles each made up of two vertices, a black edge and a gray edge, and 2χ paths each containing one cap and one chromosome-terminating gene vertex connected by a black edge. This requires somewhat more than linear time.

The breakpoint distance dB is easily calculated by storing all adjacencies of G as it is input, and verifying for each gij as it is encountered when H is input, whether its successor is gi, j+1.

3.2 Halving

In the rearrangement distance algorithm, construction of the breakpoint graph is an easy step. The genome halving algorithms (El-Mabrouk and Sankoff, 2003) also make use of the breakpoint graph, but the problem here is the more difficult one of building the breakpoint graph where one of the genomes (the doubled ancestor A′⊕A′′) is unknown. This is done by segregating the vertices of the graph in a natural way into subsets, such that the vertices of all cycles must fall within a single subset, and then constructing these cycles in an optimal way within each subset so that the black edges correspond to the structure of the known genome T and the gray edges define the adjacencies of A′⊕A′′.

As a first step each gene a in a doubled descendant is replaced by a pair of vertices (at,ah) or (ah,at) depending if the DNA is read from left to right or right to left. The duplicate of gene a=(at,ah) is written ā=(āt,āh).

Following this, for each pair of neighbouring genes, say (at,ah) and (bh,bt), the two adjacent vertices ah and bh are linked by a black edge, denoted {ah,bh} in the notation of Bergeron et al. (2006). For a vertex at the end of a chromosome, say bt, it generates a virtual edge of form {bt,end}. Note that the use of ‘end’ instead of ‘cap’ reflects a somewhat different book keeping for the beginnings and ends of chromosome in the halving algorithm compared to the distance algorithm in Section 3.1.

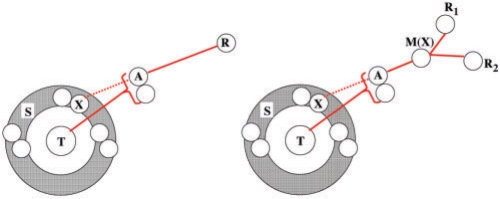

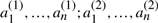

The edges thus constructed are then partitioned into natural graphs according to the following principle: If an edge {x,y} belongs to a natural graph, then so does some edge of form  and some edge of form

and some edge of form  . If a natural graph has an even number of edges, as on the left of Figure 1, it can be shown that in all optimal ancestral doubled genomes, if a gray edge, representing two adjacent vertices in the ancestor, has a vertex in this natural graph, then it necessarily connects to another vertex in the same natural graph. For natural graphs with an odd number of edges, which cannot be completed by adding pairs of edges, there are one or more ways of grouping them pairwise into supernatural graphs, as on the right of Figure 1. An optimal doubled ancestor exists such that if a gray edge has a vertex in this supernatural graph, then it connects to another vertex within the same supernatural graph. Thus the supernatural graphs may be completed one at a time.

. If a natural graph has an even number of edges, as on the left of Figure 1, it can be shown that in all optimal ancestral doubled genomes, if a gray edge, representing two adjacent vertices in the ancestor, has a vertex in this natural graph, then it necessarily connects to another vertex in the same natural graph. For natural graphs with an odd number of edges, which cannot be completed by adding pairs of edges, there are one or more ways of grouping them pairwise into supernatural graphs, as on the right of Figure 1. An optimal doubled ancestor exists such that if a gray edge has a vertex in this supernatural graph, then it connects to another vertex within the same supernatural graph. Thus the supernatural graphs may be completed one at a time.

Fig. 1.

(left) Even-size natural graph completed by adding two pairs of gray edges. (right) Two odd-size natural graphs, containing x,y,z vertices and a,b,c vertices, respectively, combined into one supernatural graph so that three pairs of gray edges may be added.

An important detail in this construction is that before a gray edge is added during the completion of a supernatural graph, it must be checked to see that it would not inadvertently result in a circular chromosome. This involves inspection within this supernatural graph only. Key to the linear worst-case complexity of the halving algorithm is that this check may be made in constant time.

Along with the multiplicity of solutions caused by different possible constructions of supernatural graphs, within such graphs and within the natural graphs, there may be many ways of drawing the gray edges. Without repeating here the lengthy details of the halving algorithm, it suffices to note that these alternate ways can be generated by choosing one of the vertices within each supernatural graph as a starting point.

3.3 Median

Unlike the genomic distances and genome halving, which can all be calculated in linear time, the genome median problem, based either on d or dB, is NP-hard (Bryant, 1998; Caprara, 2003; Pe'er and Shamir, 1998). The heuristics (Bourque and Pevzner, 2002; http://www.cs.unm.edu/ moret/GRAPPA/) commonly used to analyze the problem search for reversals that will move a genome towards the other two. This is iterated as often as possible; otherwise one of the genomes is moved towards only one of the others without prejudicing its distance to the third, and the algorithm stops when all three genomes become identical. These algorithms become prohibitively costly with moderate n.

4 PREVIOUS WORK ON GGH

4.1 Guided genome halving with one outgroup

Consider T and a related unduplicated genome R with genes orthologous to a1,…,an. Our problem is to find an unduplicated genome A that minimizes, for some A′⊕A′′,

| (1) |

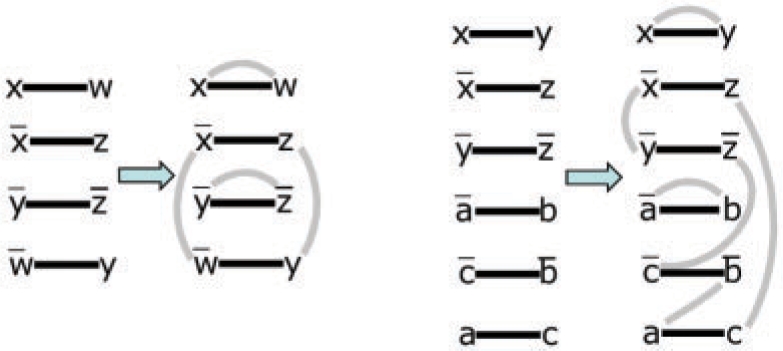

Our solution in (Zheng et al. 2006), as on the left of Figure 2, is to generate the set S of genome halving solutions, then to focus on the subset X ∈S′⊂S where d(R,X) is minimized.

Fig. 2.

Halving a doubling descendent T, with one (R) or two (R1, R2) unduplicated outgroups. The double circles represent two copies of potential ancestral genomes, including solutions to the genome halving in S, and those on best trajectories between S and outgroups.

We then minimize D(T,R) by seeking heuristically for A along any trajectory between an element X ∈S′ and the outgroups. First, each possible genome on one or more trajectories between X and R is examined in turn to see if it that decreases D(T,R). If so, it is taken as the current best value of X. When no better X is found for any starting point in S′ the current value is taken to be A.

In our experience, any more comprehensive search becomes computationally very costly, and very rarely finds a better solution.

When S′ is so large that an exhaustive search for a local minimum becomes computationally too costly, or when it is too costly to generate all of S in order to find S′, we may resort to sampling S. In defining the gray edges in the supernatural graphs of Section 3.2, we generally have several choices at some of the steps. By randomizing this choice, we are effectively choosing a random sample of X ∈S.

4.2 Guided genome halving with two outgroups

With reference to the right of Figure 2, consider T and two unduplicated genomes R1 and R2 with genes orthologous to a1,…,an. Our problem here is to find a genome A and a median genome M for A,R1 and R2 that minimize

| (2) |

for some A′⊕A′′. Our solution in Sankoff et al. (2007), as on the right of Figure 2, was to generate the set S of solutions of the genome halving problem, then to focus on the subset X ∈S′⊂S where d(R1,M)+d(R2,M)+d(X,M) is minimized, using our own implementation of the median heuristics mentioned in Section 3.3. Then we sought the A minimizing D(T,R1,R2), heuristically, along all trajectories between all elements X ∈S′ and M(X).

5 COMPLEXITY

We prove that GGH for one outgroup under the breakpoint distance dB is NP-hard, using a reduction from the Breakpoint Median Problem. The latter is NP-hard, both for unichromosomal (Bryant, 1998) and multichromosomal genomes (E.Tannier, personal communication).

We convert the breakpoint median problem on P, Q and R, three diploid genomes with the same genes, into an instance of GGH:

Construct genome P1 by appending superscript ‘1’ to the symbol for each gene in genome P.

Construct genome Q2 by appending superscript ‘2’ to the symbol for each gene in genome Q.

Let T=P1⊕Q2. We will treat T as a doubling descendant. Superscripts ‘1’ and ‘2’ distinguish the two copies of a gene.

Define an instance of GGH based on the doubling descendant T and the diploid outgroup R.

We prove that the solution of GGH for genomes T and R is also the solution of Breakpoint Median Problem on genomes P, Q and R:

Given any assignment of ‘1’ and ‘2’ superscripts to the pairs of genes in T, a solution for GGH minimizes

| (3) |

where A′ is a genome with one copy of each gene, labeled ‘1’ or ‘2’, and A′′ is the same as A′ with all the ‘1’ and ‘2’ superscripts interchanged. A is the same genome without superscripts.

LEMMA 1. —

If we construct genome A1 by appending superscript ‘1’ to each gene in genome A, and A2 by appending superscript ‘2’ to each gene in genome A, then

(4)

PROOF. —

Genomes A′ and A′′ form a solution to GGH. The sum dB(A′⊕A′′,T)+dB(A,R) is minimized. Therefore

(5) Due to the construction of the genome T, each pair of adjacent elements in T must have the same superscript. This implies that for every adjacency that A′⊕A′′ has in common with genome T, the two adjacent terms must have same superscript too. Genome A1⊕A2 contains all these common adjacencies, which implies

(6) Thus dB(A1⊕A2,T)=dB(A′⊕A′′,T). If A′ and A′′ form a solution of GGH, then A1 and A2 also constitute a solution with the same breakpoint distance. ▪

LEMMA 2. —

The breakpoint distance dB(A1⊕A2,T)=dB(A,P)+dB(A,Q).

PROOF. —

We constructed T=P1⊕Q2. The adjacencies in common between A1⊕A2 and T can be divided into two kinds:

the common adjacencies between A1 and P1 and

the common adjacencies between A2 and Q2.

Therefore dB(A1⊕A2,T)=dB(A1,P1)+dB(A2,Q2). Trivially, i.e. by simply ignoring superscripts, dB(A1,P1)=dB(A,P) and dB(A2,Q2)=dB(A,Q) ▪

THEOREM 1. —

Genome A, the solution of GGH for T and C, is also the solution of the Breakpoint Median Problem on genomes P, Q and R.

PROOF. —

From Lemma 2, dB(A1⊕A2,T)=dB(A,P)+dB(A,Q). Thus

(7) There cannot be any other genome A* such that dB(A*,P)+dB(A*,Q)+dB(A*,R)<dB(A,P)+dB(A,Q)+dB(A,R), because this A* would then have the property that

(8) a contradiction. Therefore genome G is the solution of the Breakpoint Median Problem on P, Q and R. ▪

Assuming the Breakpoint Median Problem for four genomes L,P,Q and R were also NP-hard, although we are not aware of any explicit proof, we could use the same method employed above to show that GGH with two outgroups is hard under the dB distance.

We do not yet have corresponding proofs that GGH is NP-hard under the rearrangement distance d, but this is almost certainly the case since the breakpoint distance easier to compute than rearrangement distance, even though they are both O(n). Note that the Reversals Median Problem for three or more (unichromosomal) genomes is NP-hard (Caprara, 2003).

6 THE NEW ALGORITHMS

The key idea in our improvement on the brute force algorithms is to combine information from both T and the outgroups in constructing the ancestor. It is important to take advantage of the common structure in T and the outgroups as early as possible, before it can be destroyed in the course of construction. To this end, we drop the practice of completing all the gray edges in one supernatural graph before starting another. We simply look for elements of common structure and add gray edges accordingly, making sure at each step that no circular chromosomes are inadvertently created. It is still necessary to construct the supernatural graphs at the outset, both for the check against circular chromosomes and for technical reasons we omit here, having to do with chromosome ends.

Our approach requires only slight modifications from the context of a single outgroup to that of two outgroups. For that reason, we present a single algorithm for both, with the modifications for two outgroups in square brackets. Indeed, this presentation is suggestive of a generalization to three or more outgroups.

6.1 Paths

By ‘path’ we mean any connected succession of black and gray edges in a breakpoint graph, starting and terminating with a black edge. We represent each path by an unordered pair (u,v)=(v,u) consisting of its current endpoints, though we keep track of all its vertices and edges. Initially, each black edge in T is a path, as is each black edge in R [or in each of R1 and R2].

6.2 Pathgroups

A pathgroup Γ is an ordered triple [quadruple] of paths, two in T and one in R [one each in outgroups R1 and R2], where one endpoint of one of the paths in T is the duplicate of one endpoint of the other path in T and both are orthologous to one of the endpoints of the path in R [R1 and R2]. The other endpoints may be duplicates or orthologs to each other, or not. For the special case where the duplicates are end vertices, and the supernatural graph containing it has four end nodes, then the members of a pair of duplicate dummies must originate in different (odd length) natural graphs.

6.3 The algorithms

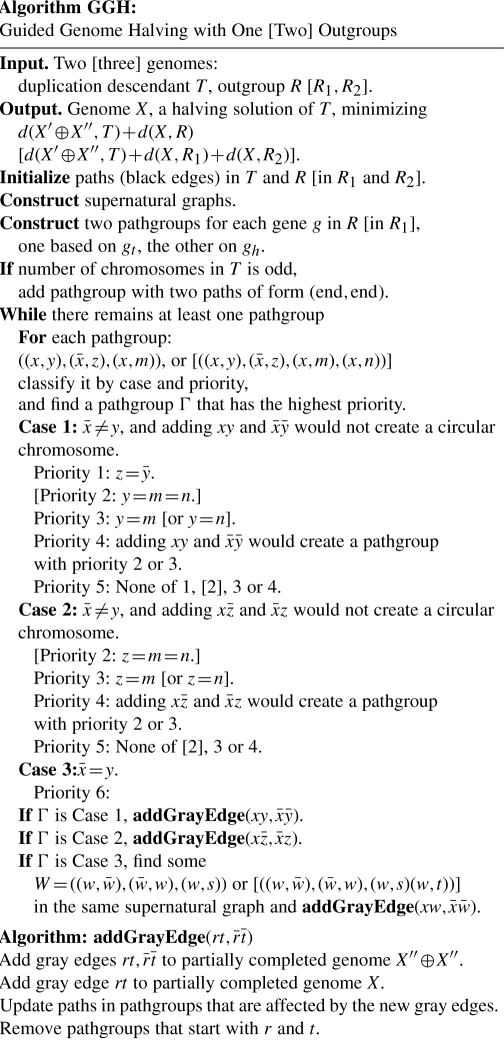

In adding pairs of gray edges to connect duplicate pairs of terms in the breakpoint graph of T versus X′⊕X′′ (which is being constructed) our approach is basically greedy, but with an important look-ahead. We can distinguish six priority levels among potential gray edges, i.e. potential adjacencies in the ancestor. Recall that in constructing the ancestor X to be close to the outgroups, such that X′⊕X′′ is simultaneously close to T, we must create as many cycles as possible in the breakpoint graphs between X and the outgroups and in the breakpoint graph of X′⊕X′′ versus T.

Adding two gray edges would create two cycles in the breakpoint graph defined by T and X′⊕X′′, by closing two paths, as on the top of Figure 3. When this possibility exists, it must be realized, since it is an obligatory choice in any genome halving algorithm. It may or may not create cycles in the breakpoint graph comparison of X with the outgroups.

Adding two gray edges would create three cycles, one for T and one for each of two outgroups.

Adding two gray edges would create two cycles, one for T and one for one outgroup, as in the middle of Figure 3.

Adding two gray edges would create one cycle for T but none for the outgroups. It would, however, create a higher priority pathgroup, e.g., Figure 3, bottom.

Adding two gray edges would create a cycle in the T versus X′⊕X′′ comparison, but none for the outgroups, nor would it create any higher priority pathgroup.

Each remaining path terminates in duplicate terms, which cannot be connected to form a cycle, since in X′⊕X′′ these must be on different (and identical) chromosomes. In supernatural graphs containing such paths, there is always another path and adding two gray edges between the endpoints of the two paths can create a cycle.

In not completing each supernatural graph before moving on to another, we lose the advantage in (El-Mabrouk and Sankoff, 2003) of a constant time check against creating circular chromosomes. The worst case becomes a linear time check. In practice, this is a small liability, because the worst case scenario is seldom realized.

|

Fig. 3.

Priority levels of some pathgroups for GGH with one outgroup.

Once the GGH algorithm is terminated, we undertake the local search described in Sections 4.1 and 4.2 to see if we can improve X by allowing it to move out of S on a trajectory towards R.

7 GENOME DOUBLING IN YEAST

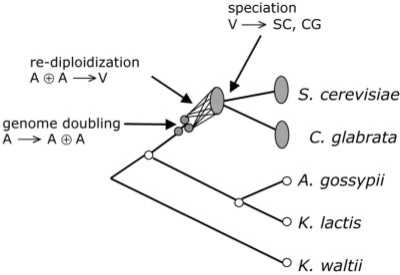

Wolfe and Shields (1997) discovered an ancient genome doubling in the ancestry of S.cerevisiae in 1997 after this organism became the first eukaryote to have its genome sequenced (Goffeau et al., 1996). According to Kurtzman and Robnett (2003), the recently sequenced C.glabrata (Dujon et al., 2004) shares this doubled ancestor. We extracted data from YGOB (Yeast Genome Browser) (Byrne and Wolfe, 2005), on the orders and orientation of the 600 genes (300 pairs) identified as duplicates in both genomes.

The YGOB (Byrne and Wolfe, 2005) contains complete gene orders and orthology identification among the five yeast species depicted in Figure 4: the two descendents of the above-mentioned ancient genome duplication event, S.cerevisiae and C.glabrata, and three species that diverged before this event, A.gossypii, K.waltii and K.lactis. For the ancient tetraploids, YGOB includes a reconstruction of the ancestral genome. We abbreviate these six genomes as SC, CG, AG, KW, KL and A*, respectively. In addition, we construct an ancestral doubled descendant V lying on a shortest rearrangement trajectory from SC to CG, satisfying the criterion that its halving distance is minimal (Zheng et al., 2007b). We take the ancestor A* as ‘ground truth’ and see how close we can approach it using the sampling method and the guided halving method, with various combinations of doubling descendants and unduplicated genomes.

Fig. 4.

Phylogeny of yeasts in YGOB. Whole genome doubling event giving rise to ancestor of S.cerevisiae and C.glabrata indicated, followed by rediploidization and speciation and the divergence of these two species.

8 RESULTS

Table 1 compares the results, before and after local optimization, of the guided halving algorithm and the sampling approach on 12 pairs of genomes, the three doubling descendants SC, CG and V, each versus the four unduplicated genomes AG, KL, KW and A*. Recall that V and A* are themselves analytical constructs, the former representing the most recent common ancestor of SC and CG, and the latter the ancestral genome at the moment of doubling.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of sampling method and guided halving algorithm in the case of one outgroup

| Halving analysis |

Sampling method |

Guided halving |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R−T | 2n | dt,x⊕x | dx,r | dmin | da,r | ΔA | da,a* | Time | dx,r | da,r | ΔA |  |

Time |

| AG-CG | 538 | 186 | 204 | 196 | 180 | −16 | 156 | 37 | 153 | 153 | 0 | 120 | 2.3 |

| AG-SC | 1012 | 119 | 237 | 229 | 208 | −21 | 53 | 158 | 184 | 183 | −1 | 32 | 5.3 |

| KL-CG | 546 | 186 | 210 | 203 | 184 | −19 | 154 | 50 | 160 | 160 | 0 | 120 | 3.5 |

| KL-SC | 1026 | 122 | 241 | 232 | 216 | −16 | 51 | 140 | 197 | 197 | 0 | 39 | 6.1 |

| KW-CG | 542 | 188 | 247 | 238 | 230 | −8 | 167 | 26 | 216 | 215 | −1 | 142 | 3.3 |

| KW-SC | 994 | 121 | 364 | 355 | 350 | −5 | 70 | 72 | 325 | 323 | −2 | 41 | 5.1 |

| A*-CG | 600 | 199 | 183 | 169 | 129 | −40 | 129 | 81 | 84 | 84 | 0 | 84 | 1.5 |

| A*-SC | 1062 | 124 | 79 | 70 | 37 | −33 | 37 | 114 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0.3 |

| AG-V | 576 | 61 | 157 | 151 | 149 | −2 | 54 | 12 | 148 | 148 | 0 | 51 | 0.9 |

| KL-V | 584 | 62 | 167 | 160 | 158 | −2 | 53 | 12 | 157 | 157 | 0 | 51 | 0.9 |

| KW-V | 582 | 62 | 224 | 218 | 215 | −3 | 52 | 13 | 212 | 212 | 0 | 51 | 1.0 |

| A*-V | 600 | 62 | 57 | 49 | 39 | −10 | 39 | 14 | 29 | 29 | 0 | 29 | 0.2 |

Sample size 2000 for the sampling method. R−T represents the outgroup and doubling descendant. n is the number of genes available in that pair of genomes, with two copies in T. dt,x⊕x=d(T,X′⊕X′′) is the doubling distance, constant over all analyses.  represents the average, over all samples, of the distance estimate between the ancestor, just before doubling, and the outgroup, and the adjacent entry dmin=minsampled(X,R) is the minimum found. ΔA is the improvement over d(T,X′⊕X′′)+d(X,R) due to local searching, allowing A to be found outside the set of halving solutions. da,a*=d(A, A*) is the distance between the inferred ancestor and the ‘ground truth’. Time is measured in minutes, for 2000 samples of unrestricted halving or for one GGH run.

represents the average, over all samples, of the distance estimate between the ancestor, just before doubling, and the outgroup, and the adjacent entry dmin=minsampled(X,R) is the minimum found. ΔA is the improvement over d(T,X′⊕X′′)+d(X,R) due to local searching, allowing A to be found outside the set of halving solutions. da,a*=d(A, A*) is the distance between the inferred ancestor and the ‘ground truth’. Time is measured in minutes, for 2000 samples of unrestricted halving or for one GGH run.

The first observations are methodological. In all 12 cases guided halving results in an X closer to R than in any of 2000 samples of unrestricted halving. If computing time were no obstacle, the sampling method would be exhaustive and exact, and hence always at least as good as guided halving. The fact that none of the 12 analyses produced a ‘lucky’ sample as good as or better than GGH, suggests that we would need a sample size of 25 000 at the very least, and perhaps one or more orders of magnitude larger, to bring the accuracy of sampling method to the level of guided halving, but this would require thousands of hours or more for our entire dataset versus less than 30 min with guided halving.

The fact that the results of the sampling method are improved by local searching, usually substantially, in all 12 cases, whereas guided halving produces genomes already at or very close to a minimum (albeit possibly local) of the objective function, is another measure of the superior performance of the latter.

Note that aside from the three cases where the ground truth ancestor A* plays the role of outgroup, this genome is not directly involved in the analysis. It is of great interest, then, from the biological viewpoint, that in all cases, guided halving produces an ancestor A closer to A* than the sampling method. Moreover, when using A* as an outgroup for the halving of SC, the analysis reconstructs something very close to A*, i.e. where d(A,A*) is only 5. This attests to the internal coherence of the method: the SC evidence was predominant in the original construction of A* (Byrne and Wolfe, 2005).

Turning to the case of two outgroups, we first point out that the sampling approach becomes infeasible when even a moderate number of analyses are undertaken. This is due to the relatively lengthy time (sometimes more than 2 h) required to compute the median cost, i.e., the sum of the three distances, from R1,R2 and the inferred ancestor X, to the median. (The halving algorithm alone, and even guided halving, never takes more than 2 or 3 min.) This is not an obstacle to the guided halving method because the median need to be calculated just once, instead of the thousands of times for the sampling approach. Table 2 shows the result of halving guided by two outgroups, using all combinations of two of AG, KL and KW versus each of SC, CG and V.

Table 2.

Results of guided halving algorithm in the case of two outgroups

| R1−R2−T | n | d(T,X′⊕X′′) | Median cost | d(T,A′⊕A′′) | Median cost | ΔA | d(A, A*) | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AG-KL-SC | 497 | 117 | 364 | 117 | 361 | −3 | 40 | 131 |

| AG-KW-SC | 478 | 116 | 502 | 116 | 498 | −4 | 41 | 204 |

| KL-KW-SC | 471 | 121 | 518 | 121 | 516 | −2 | 48 | 217 |

| AG-KL-CG | 265 | 183 | 300 | 183 | 297 | −3 | 124 | 48 |

| AG-KW-CG | 261 | 184 | 362 | 184 | 361 | −1 | 138 | 55 |

| KL-KW-CG | 259 | 184 | 368 | 184 | 366 | −2 | 136 | 62 |

| AG-KL-V | 283 | 61 | 278 | 61 | 275 | −3 | 47 | 38 |

| AG-KW-V | 280 | 61 | 340 | 62 | 339 | 0 | 51 | 41 |

| KL-KW-V | 277 | 62 | 354 | 62 | 352 | −2 | 54 | 54 |

Median cost refers to the sum of the three distances, from R1,R2 and the inferred ancestor X or A, to the median. The objective is d(T,X′⊕X″)+median cost. ΔA is the improvement of d(T,A⊕A)+median cost over d(T,X′⊕X′′)+median cost due to local searching, allowing A to move outside the set of halving solutions. Time in minutes.

In general, we note no advantage of using two outgroups over one, in that d(A,A*) with two outgroups is not as good as d(A,A*) for the better of the two used alone. The exception is the comparison of KL and AG with V. Thus it seems, at least with these data, that the more remote outgroup contributes little more than noise to the reconstruction guided by the closer outgroup. This result may be due to the great discrepancy in the phylogenetic divergence between the doubled genomes and KW compared to the divergence between the former and AG or KL, and may not carry over to other datasets.

Two observations: first, the improvement due to local search is relatively small, though larger than guided halving with one outgroup. Second, though our analyses did find some A outside of S that minimized D(T,R1,R2), in each such case there was also a solution (the one entered in Table 2) with A ∈S.

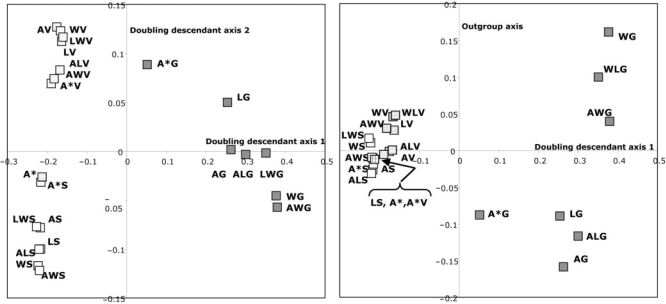

To investigate to what extent differences between the doubling descendants and among the outgroups are reflected in the reconstructed ancestor genome A, we undertook Gower's principal coordinates analysis (Gower, 1966) of the 21 versions of A described in Tables 1 and 2, as well as A* itself. We used the implementation of this analysis available as cmdscale in the R environment (R Development Core Team, 2007), applied to the 22 × 22 genomic distance matrix.

Figure 5 depicts the results of a 3D principal coordinates analysis. We note first that the first two dimensions basically distinguish among the doubling descendants, first classifying SC and V together versus CG, and then distinguishing between SC and V. The third dimension distinguishes between the genomes in which KW was the outgroup and those in which only AG and/or KL were outgroups. As we would expect, all the genomes with A* as the outgroup or as one of two outgroups, are closer to the ‘true’ ancestor A* than when some other outgroup is used instead. Nevertheless, other outgroups, such as AG, also help guide the reconstruction to fairly close approximations of A*. On the other hand, constructions guided by CG are all very far from A*, and those involving KW tend to be somewhat farther than those guided by AG and KL. The latter observation is consistent with the known highly rearranged nature of CG, and with the relatively distant evolutionary relationship between KW and A*, as can be seen in Figure 4.

Fig. 5.

First three dimensions of principal coordinate analysis of distances among 22 inferences of ancestral genome, based on different configurations of outgroups. Left: dimensions 1 and 2. Right dimensions 1 and 3. Dimension labels assigned subjectively after the analysis. Genomes SC, CG, AG, KL and KW further abbreviated in displays to S, G, A (not to be confused with A for ancestor elsewhere in the text, nor with A*), L and W, respectively.

9 DISCUSSION

We have focused on the two main concerns of genome halving, the multiplicity and the diversity of solutions, and the difficulty of assessing the accuracy of the results with real data. GGH was previously shown to drastically reduce the non-uniqueness inherent in unrestricted halving. This is carried further by GGH, which achieves much greater accuracy with much less computational effort.

An important indication of the precision of the reconstruction is its ability with some of the data to come very close to the manually reconstructed ancestor A.

Nevertheless, these results remind us of the uncertainties inherent in historical reconstruction. Some of this is possibly due to the ‘noise’ of mistaken paralogy identification, especially in highly rearranged genomes such as C.glabrata. Future work will attempt to attenuate this noise using the techniques of Zheng et al. (2007a) and Choi et al. (2007).

The significance of halving results depends on what proportion of the doubling descendant T is and can be identified as duplicated genes. Our analysis does not attempt to situate the ancestors of genes present in only one copy in T, and these will often form the majority. Ongoing work exploits the syntenic relationships between these genes, the duplicated ones, and their orthologs in the outgroups.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ken Wolfe, Kevin Byrne and Jonathan Gordon for encouragement and for valuable information. We also thank Howard Bussey, Eric Tannier and Robert Warren for helpful discussions. D.S. holds the Canada Research Chair in Mathematical Genomics.

Funding: Research supported in part by a grant to D.S. from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Footnotes

1Sequence analysis tools for dating duplication events are not pertinent to this problem since all pairs of duplicates in the doubled genome were generated at the same historical moment.

2All cereals underwent earlier WGD event(s), but the effects of these can be filtered out on the basis of greater sequence divergence.

See Yancopoulos et al. (2005) for a more general inventory.

REFERENCES

- Bergeron A, et al. A unifying view of genome rearrangements. In. In: Bücher P, Moret BME, editors. Algorithms in Bioinformatics. Proceedings of WABI 2006. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 4175. Springer, Berlin: 2006. pp. 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- Bourque G, Pevzner P. Genome-scale evolution: reconstructing gene orders in the ancestral species. Genome Res. 2002;12:26–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant D. Technical Report CRM–2579. Montreal, Canada: Centre de recherches mathématiques, Université de Montréal; 1998. The complexity of the breakpoint median problem. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne KP, Wolfe KH. The Yeast Gene Order Browser: combining curated homology and syntenic context reveals gene fate in polyploid species. Genome Res. 2005;15:1456–61. doi: 10.1101/gr.3672305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprara A. The reversals median problem. INFORMS J. Comput. 2003;15:93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Choi V, et al. Algorithms for the extraction of synteny blocks from comparative maps. In. In: Giancarlo R, Hannenhalli S, editors. Proceedings of the WABI 2007 Workshop on Algorithms in Bioinformatics. Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics 4645. Heidelberg: Springer; 2007. pp. 277–288. [Google Scholar]

- Dujon B, et al. Genome evolution in yeasts. Nature. 2004;430:35–44. doi: 10.1038/nature02579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Mabrouk N, Sankoff D. The reconstruction of doubled genomes. SIAM J. Comput. 2003;32:754–92. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mabrouk N, et al. Reconstructing the pre-doubling genome. In. In: Istrail S, Pevzner P, Waterman M, editors. Proceedings of the Third Annual International Conference on Computational Molecular Biology (RECOMB 99) New York: ACM Press; 1999. pp. 154–163. [Google Scholar]

- Goffeau A, et al. Life with 6000 genes. Science. 1996;275:1051–1052. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gower JC. Some distance properties of latent root and vector methods used in multivariate analysis. Biometrika. 1966;53:325–328. [Google Scholar]

- GRAPPA (Genome Rearrangements Analysis under Parsimony and Other Phylogenetic Algorithms.) [(Date last accessed May 2008)]; Available at http://www.cs.unm.edu/~moret/GRAPPA/

- Kurtzman CP, Robnett CJ. Phylogenetic relationships among yeasts of the ‘Saccharomyces complex’ determined from multigene sequence analyses. FEMS Yeast Res. 2003;3:417–32. doi: 10.1016/S1567-1356(03)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pe'er I, Shamir R. The median problems for breakpoints are NP- complete. [Date last accessed May 2008];Electronic Colloquium on Computational Complexity Technical Report 98-071. 1998 Available at http://www.eccc.uni-trier.de/eccc.

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Date last accessed May 2008];R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2007 Available at http://www.R-project.org.

- Sankoff D, et al. Polyploids, genome halving and phylogeny. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:i433–i439. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesler G. Efficient algorithms for multichromosomal genome rearrangements. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 2002;65:587–609. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe KH, Shields DC. Molecular evidence for an ancient duplication of the entire yeast genome. Nature. 1997;387:708–713. [Google Scholar]

- Yancopoulos S, et al. Efficient sorting of genomic permutations by translocation, inversion, and block interchange. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3340–3346. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C, et al. Genome halving with an outgroup. Evol. Bioinform. 2006;2:319–326. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C, et al. Removing noise and ambiguities from comparative maps in rearrangement analysis. Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2007a;4:515–522. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2007.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C, et al. Parts of the problem of polyploids in rearrangement phylogeny. In. In: Tesler G, Durand D, editors. Proceedings of the RECOMB 2007 Workshop on Comparative Genomics. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 4751. New York: Springer; 2007b. pp. 162–176. [Google Scholar]