Abstract

Background

Delimiting distinct chromatin domains is essential for temporal and spatial regulation of gene expression. Within the X-inactivation centre region (Xic), the Xist locus, which triggers X-inactivation, is juxtaposed to a large domain of H3K27 trimethylation (H3K27me3).

Results

We describe here that developmentally regulated transcription of Tsix, a crucial non-coding antisense to Xist, is required to block the spreading of the H3K27me3 domain to the adjacent H3K4me2-rich Xist region. Analyses of a series of distinct Tsix mutations suggest that the underlying mechanism involves the RNA Polymerase II accumulating at the Tsix 3'-end. Furthermore, we report additional unexpected long-range effects of Tsix on the distal sub-region of the Xic, involved in Xic-Xic trans-interactions.

Conclusion

These data point toward a role for transcription of non-coding RNAs as a developmental strategy for the establishment of functionally distinct domains within the mammalian genome.

Background

The packaging of DNA into a chromatin structure consisting of repeating nucleosomes formed by 146 base pairs of DNA wrapped around an octamer of the four core histones (H2A, H2B, H3 and H4) has been revealed as an incredible source of complexity, allowing the precise control of all biological processes centred on DNA such as transcription, replication, repair and recombination. The amino-terminal domain of the histones is the target of several post-translational modifications underlying the complex relationships between chromatin structure and function [1]. Among them, methylation of lysines 4 and 27 of histone H3 (H3K4 and H3K27, respectively) have been extensively studied at the level of specific loci, as well as chromosome- and genome-wide [2], revealing an accurate correlation between H3K4 methylation and activation or potentiality for transcription on the one hand, and H3K27 methylation and transcriptional repression on the other. These apparently opposite histone modifications can be found either as sharply localized peaks (for example, around promoters) or as more extended domains structuring the genome into 'open' regions of activation or competence (euchromatin), and 'close' regions of long-term repression (heterochromatin). In addition, in pluripotent cells such as embryonic stem (ES) cells, highly conserved non-coding elements and developmentally regulated genes have been shown to be characterized by a combination of methylation at both H3K4 and H3K27, referred to as 'bivalent' domains [3], which allows the establishment of active transcription or long-term silencing upon differentiation. Several large descriptive analyses have been performed to establish correlations between specific histone marks and activation or repression of gene expression. A recent study has reported a striking negative correlation between transcription and H3K27me3, where large domains of H3K27me3 were found to be flanked by expressed genes [4]. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying such a partitioning (and more generally the actual relationship between transcription and chromatin states) remain elusive, especially in mammals.

In this study, we have used the mouse X-inactivation centre (Xic), a complex locus responsible for initiation of X-inactivation in mammalian female cells [5], to examine the complex relationships between transcription and H3K4 and H3K27 methylation in ES cells, a model system that recapitulates X-inactivation upon differentiation.

Defined on the basis of chromosomal rearrangements and transgenic studies, the Xic contains numerous protein-coding genes such as Xpct, Cnbp2, Tsx, Cdx4 and Chic1, in addition to the non-coding genes Ftx, Jpx, Xist and Tsix. So far, only two of these genes, Xist and its antisense partner Tsix, have been directly implicated in the regulation of X-inactivation [6]. The Xist gene produces a long non-coding RNA that coats the X chromosome in cis and is responsible for X-linked gene silencing and X-chromosome-wide acquisition of facultative heterochromatic properties [7]. Controlling the production of increased quantities of Xist RNA molecules is, therefore, an essential event in the complex regulation that leads to the inactivation of a single X chromosome in females and the absence of X-inactivation in males. It has been proposed that Xist expression shifts from low to high levels at the onset of X-inactivation through the active recruitment of the transcriptional machinery to the Xist promoter [8,9].

Tsix, which blocks Xist RNA accumulation in cis, is highly expressed prior to the onset of random X-inactivation, as in undifferentiated ES cells [10]. Using Tsix mutations generated in ES cells, it has been demonstrated that Tsix expression is required to maintain Xist silencing in differentiating male ES cells [11,12], and to ensure a random choice of the X chromosome that will upregulate Xist transcription and be inactivated in females [13,14]. The molecular mechanism of the Tsix-dependent regulation of Xist expression in ES cells has been linked to complex chromatin remodelling activities [8,9,15-17]. In particular, Tsix transcription is responsible for the deposition of H3K4me2 along Xist [9], except at the Xist promoter region, whose euchromatinization is blocked by Tsix-induced methylation of both CpG dinucleotides and H3K9 [8].

Intriguingly, the Tsix locus is juxtaposed in its 3'-end to a large domain spanning over 340 kb that displays, prior to inactivation, some heterochromatic features of the inactive X. Initially described as a region characterized by H3K4 hypomethylation and H3K9 di-methylation [18], it was then demonstrated that H3K27me3 was also present at the hotspot region [19]. Importantly, both repressive histone marks were shown to be differentially regulated as only H3K9me2 was affected upon loss of the G9a histone methyltransferase [19]. Given the capacity of heterochromatic histone marks to spread across adjacent regions, and the role of histone modifications in the establishment of the appropriate transcriptional activity of Xist, an important question that arises concerns the mechanisms that protect the Xist locus from heterochromatin spreading from the so-called hotspot region. Here, we demonstrate that Tsix transcription is required in cis to block H3K27me3 at Xist. Based on a series of Tsix mutations, we further hypothesize that Tsix transcription blocks H3K27me3 spreading from the hotspot, and that the chromatin boundary activity of Tsix likely involves the RNA Polymerase II (RNAPII) accumulating at the Tsix 3'-end. In addition, we show that Tsix impacts levels of both H3K27 methylation and gene expression within the hotspot itself, including the Xpct gene, which maps to a crucial region that mediates X-chromosome pairing in female ES cells. Our study thus sheds light on the regulation of Xic chromatin by Tsix, and on the mechanisms delimiting chromatin domains through non-coding transcription in mammalian cells.

Results

Distribution of H3K27me3 within the Xic in undifferentiated embryonic stem cells is controlled by Tsix

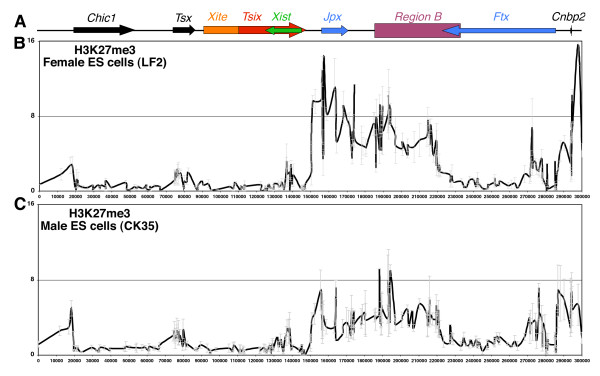

We have previously identified a large hotspot of H3K27me3 lying 5' to Xist in undifferentiated ES cells [18,19]. In order to precisely map the extent and boundaries of the hotspot, we used 383 primer pairs designed across a 300 kb region spanning Xist/Tsix (Figure 1A) in chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays. We found that the H3K27me3 domain is identically structured in several sub-regions in female (Figure 1B) and male (Figure 1C) ES cells, although levels of enrichment were, on average, two- to three-fold higher in females. Whether this difference is sex-linked or based on sex-independent variations between ES cell lines remains to be investigated. Strikingly, a large and predominant region of H3K27me3 is located between the 3'-ends of Tsix and Ftx, suggesting that H3K27me3 in that region is constrained by the transcription of these two non-coding genes. This is reminiscent to the large BLOCs of H3K27me3 described across the mouse chromosome 17, which are flanked by active genes [4]. Accumulation of H3K27me3 resumes in the 5' region of Ftx (with the exception of the Ftx promoter; Figure 1) and, as previously shown [19], extends toward Cnbp2 and Xpct (Supplementary Figure 1), a region required for X-chromosome pairing in female cells [20]. The distribution of H3K27me3 within the Xic in undifferentiated ES cells, in particular the inverse correlation observed between H3K27 methylation levels and Tsix transcription, suggests that Tsix may be involved in constraining H3K27me3 to its 3'-end. This is in agreement with previous data showing increased accumulation of H3K27me3 within Xist in the absence of Tsix [8,16,17]. To probe this hypothesis, we turned our attention to the analysis of two male ES cell lines in which Tsix transcription has been eliminated before reaching Xist or drastically reduced: Ma2L, generated through the insertion of a loxP-flanked transcriptional STOP signal within Tsix [14], and ΔPas34, in which a potent enhancer of Tsix, DXPas34, has been deleted [12].

Figure 1.

Distribution of H3K27 tri-methylation within a 300-kb region of the Xic in undifferentiated male and female embryonic stem (ES) cells. (A) Schematic diagram of the 300-kb region analyzed in our ChIP experiments showing the location of the different transcription units of the Xic. Arrows indicate the direction of each transcription unit. Coding genes are indicated in black, non-coding genes with coloured arrows. The orange box represents the Xite locus, an enhancer region that displays transcriptional activity on the major Tsix promoter. The purple box represents the so-called region B, a complex transcriptional unit that produces both sense and antisense transcripts [40]. We used in each ChIP experiment a set of 383 primer pairs that were designed automatically to cover the 300-kb region (except repeat regions: see Materials and methods). (B) ChIP analysis of H3K27 trimethylation in undifferentiated female (LF2) ES cells and (C) in male (CK35 cell line) ES cells. Both graphs show the percentage of immunoprecipitation (%IP) obtained after normalization to the input. All values are mean ± standard deviation. The average percentage of immunoprecipitation calculated for each position was plotted against the genomic location (bp). The +1 coordinate corresponds to position 1,005,322,247 in NCBI build 37.

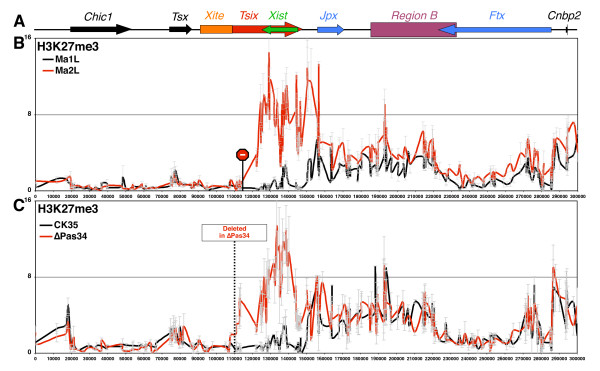

In the two mutants tested, high levels of H3K27me3 were observed within Xist in perfect continuity from the hotspot region (Figure 2). In Tsix-truncated cells, the H3K27me3 domain extends up to the inserted transcriptional STOP signal (Figure 2B), and in ΔPas34 cells up to the Tsix promoter itself (Figure 2C). Thus, the enrichment for H3K27me3 following Tsix invalidation progresses from the Tsix 3'-end towards the Tsix 5'-end, and extends beyond Xist, indicating a lack of sequence specificity. This apparent sequence-independent, progressive and directional enrichment along the Xist/Tsix region indicates that, in the absence of Tsix transcription, the hotspot of H3K27me3 spreads into the Xist/Tsix locus and, therefore, suggests that Tsix acts as a boundary element partitioning two distinct chromatin domains. More strikingly, when the loxP-flanked transcriptional STOP signal was removed from Ma2L, and Tsix transcription restored (Ma1L) [9,14], the boundary of the hotspot domain was re-established at its wild-type location (Figure 2B), which corresponds to the endogenous 3'-end of Tsix.

Figure 2.

H3K27 tri-methylation spreads from the hotspot into Xist in the absence of Tsix transcription. (A) Map of Xic (see Figure 1A). (B) ChIP analysis of H3K27 trimethylation in male Tsix-truncated embryonic stem (ES) cells (Ma2L cell line, red line) and in the corresponding revertant (Ma1L, black line). In the Ma2L cell line, Tsix transcription has been truncated through the insertion of a loxP-flanked transcriptional STOP signal downstream of the Tsix promoter (represented in the graph by the STOP symbol). The Ma1L revertant was obtained from Ma2L after deletion of the STOP signal. (C) Similar analysis in male wild-type (CK35 cell line, black line) and mutated (ΔPas34, red line) ES cells in which Tsix transcription is drastically reduced. The ΔPas34 cell line was generated by deleting DXPas34, an enhancer of Tsix located near the Tsix major promoter. Dotted lines in the graph indicate the location of the 1.2-kb deletion carried by ΔPas34 ES cells.

Xic-wide loss of H3K27me3 during differentiation

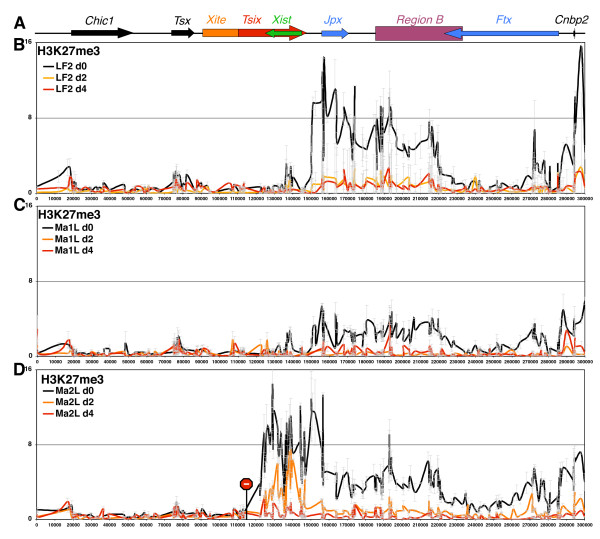

We then established the profile of H3K27me3 at the Xic in differentiating ES cells, when Tsix silencing occurs spontaneously [10]. Since Tsix blocks H3K27me3 encroachment at Xist before differentiation, we expected to find higher levels of methylation at Xist following differentiation. However, no significant H3K27me3 enrichment was observed within Xist after 2 and 4 days of retinoic acid-mediated differentiation, whether in female (Figure 3B) or male cells (Figure 3C). Instead, a dramatic loss of H3K27me3 within the hotspot region occurs during the first 2 days of differentiation (Figure 3B, C). The entire Xic region, including Xist, is therefore devoid of H3K27me3 during the time window corresponding to the initiation of X-inactivation in female wild-type ES cells. This result rules out a determinant role for H3K27me3 at either the future active X or the inactive X in the establishment of the appropriate Xist expression patterns leading to random X-inactivation. In differentiating Tsix-truncated cells, however, significant levels of H3K27me3 can still be detected at Xist at day 2 of differentiation, although it becomes undetectable within the hotspot itself (Figure 3D). While this could be attributable to the Xist region being more resistant to the loss of ectopically acquired H3K27me3, it reveals that Xist is not particularly refractory to H3K27 methylation on differentiation. Thus, the absence of H3K27me3 enrichment at the Xist/Tsix region in differentiating wild-type cells is not related to specific regulations of that region that impede H3K27 methylation.

Figure 3.

Loss of H3K27 tri-methylation at the Xic during embryonic stem (ES) cell differentiation. (A) Map of Xic (see Figure 1A). (B-D) Extensive ChIP analysis of H3K27 trimethylation in (B) wild-type female ES cells (LF2), (C) wild-type male revertant cells (Ma1L), or (D) Tsix-truncated ES cells (Ma2L). ChIP experiments were performed on undifferentiated ES cells (black line) and after 2 and 4 days (orange and red lines, respectively) of differentiation with retinoic acid.

In summary, if Tsix were acting by repressing freely diffusing methylation activities acting on Xist independently from the hotspot chromatin, the differentiation process and the consequent silencing of Tsix should be accompanied by H3K27me3 encroachment at Xist. Thus, and given that H3K27me3 at the hotspot region is specific to undifferentiated ES cells, and that the absence of Tsix induces H3K27me3 at Xist only in undifferentiated ES cells, we propose that the enrichment for H3K27me3 at Xist observed in Tsix-mutant undifferentiated cells depends on the presence of H3K27me3 at the region upstream of Xist, and is related to a deregulation of the hotspot chromatin boundary resulting from the lack of Tsix transcription.

Tsix-mediated H3K4 methylation is not involved in blocking H3K27me3 spreading

One hypothesis of how Tsix might block the spreading of H3K27me3 is related to the chromatin remodelling activities that Tsix displays at the Xist locus. We have indeed previously reported that Tsix transcription triggers the deposition of H3K4me2 across its own transcription unit [9]. In addition, Tsix is responsible for establishing a repressive chromatin structure over the Xist promoter, characterized by elevated levels of H3K9 and DNA methylation and by low levels of H3K4 methylation and H3K9 acetylation [8].

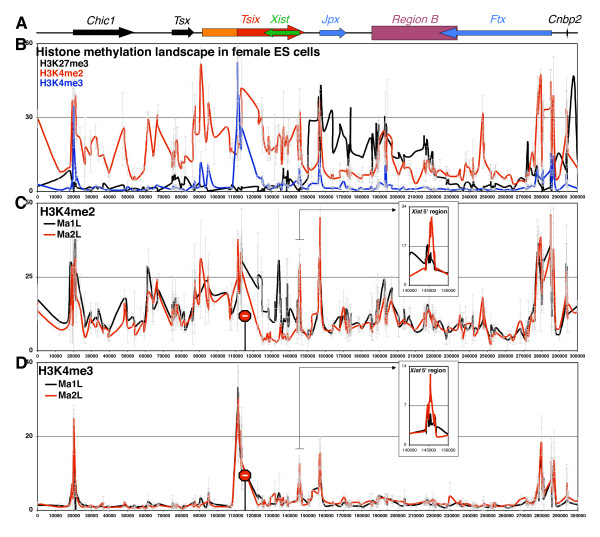

To probe the relationship between Tsix transcription, H3K27me3 and H3K4 methylation, we extended the analysis of H3K4 di- and tri-methylation profiles to the entire Xic region. We observed that the Xic is structured in two distinct domains: a large domain enriched for H3K4me2 extending from Chic1 to the Tsix 3'-end, juxtaposed to the hotspot of H3K27me3 from the Tsix 3'-end onwards (Figure 4B). Some interspersed regions of H3K4me2 were found downstream of Tsix, such as at the promoters of Jpx, Ftx and Cnbp2. As previously demonstrated [8,9], the lack of Tsix transcription was associated with the loss of H3K4me2 across Tsix with the exception of the Xist promoter itself, where higher levels were found in Ma2L (Figure 4C). It is important to note that the level of background detected with the H3K4me2 antiserum used in this study is relatively high. The residual H3K4me2 signal observed in the H3K27me3 hotspot region and within Xist in the Tsix mutant cell line indeed corresponds to background, as previously shown using a no-longer available antiserum ([9] and data not shown).

Figure 4.

H3K4 methylation is not involved in the H3K27me3 boundary formation at the Xic. (A) Map of Xic (see Figure 1A). (B) ChIP analysis showing the distribution of histone H3 modifications at the Xic in female embryonic stem (ES) cells (LF2) using antibodies against H3K27 trimethylation (H3K27me3, black line), H3K4 dimethylation (H3K4me2, red line) and H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3, blue line). (C) Extensive analysis of H3K4me2 and (D) H3K4me3 in wild-type (Ma1L, black line) and Tsix-truncated (Ma2L, red line) male ES cells. Insets focus on the percentage of immunoprecipitation observed at the Xist 5' region.

In agreement with genome-wide analyses [2], the profile of H3K4me3 was highly restricted to active promoter regions, such as those of Chic1, Tsix, Jpx and Ftx, in both female and male ES cells (Figure 4B, D). Promoters of genes displaying low levels of expression, such as Cnbp2 and Xist, were not consistently marked with H3K4me3. In addition, some regions such as the promoter of Jpx were found enriched in both H3K4me3 and H3K27me3, thus defining a bivalent domain. Truncation of Tsix did not affect the levels and distribution of H3K4me3 across the region, with the exception of the Xist promoter, which displayed elevated levels in the absence of Tsix, as previously reported [8].

The global mirror image between H3K4me2 and H3K27me3 at the Xic, together with the opposite influence of Tsix on both marks across Xist/Tsix, could suggest that Tsix blocks H3K27me3 spreading through the deposition of H3K4me2. Two observations, however, indicate that this is likely not the case. First, in the absence of Tsix, the Xist promoter becomes methylated on both K4 and K27 residues of H3 (Figures 3D and 4C). Second, regions enriched for both marks have been reported from both genome-wide analysis [3] and our analysis of the Xic (Figure 4). This strongly argues against the idea that the H3K4me2 domain triggered by Tsix is a barrier for H3K27 tri-methylation.

Mechanistic insights into the boundary function of Tsix

The profile of H3K27me3 accumulation in wild-type cells reveals that the boundary of the H3K27me3 hotspot maps to position 150,000, which approximately corresponds to the region of Tsix transcription termination as previously described [21]. In order to investigate the molecular basis for the barrier activity of Tsix, we analyzed the distribution of RNAPII molecules across the Xist/Tsix region.

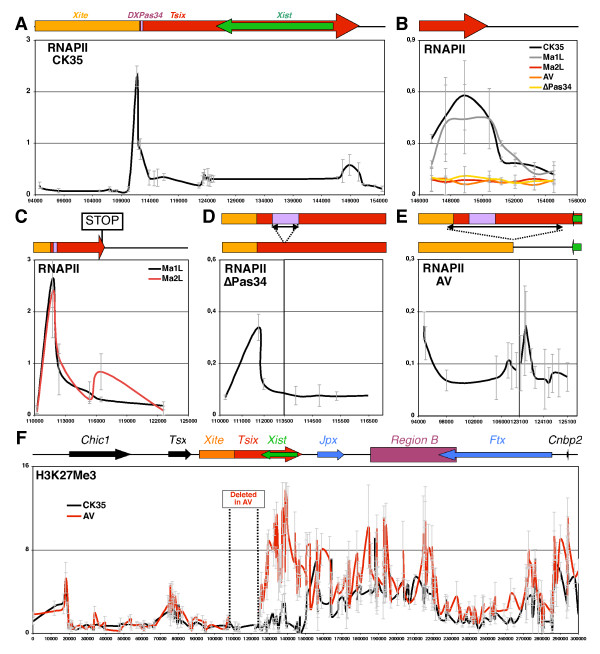

In wild-type cells, RNAPII was shown to markedly accumulate at the Tsix 5' region (Figure 5A). Levels of RNAPII then remain low along the Xist locus and appear enriched between positions 147,000 and 151,000 (Figure 5A, B), as expected for a region where transcription termination and RNA cleavage of Tsix should occur, causing pausing and accumulation of RNAPII molecules. Strikingly, this peak of RNAPII corresponds precisely to the boundary of H3K27me3, as mapped above (around position 150,000). This observation suggests that the accumulation of RNAPII molecules itself at the Tsix 3'-end could be involved in blocking the spreading of H3K27me3 from the hotspot to within Xist/Tsix. To probe this hypothesis, we measured RNAPII accumulation across this region in two Tsix mutant cell lines (Ma2L and ΔPas34) in which the boundary of the hotspot has been displaced. The enrichment for H3K27me3 over this region in the mutants correlates with a complete loss of RNAPII accumulation (Figure 5B). Strikingly, RNAPII was rather found to accumulate at the ectopic boundary of the H3K27me3 domain. This corresponds precisely to the site of ectopic termination of Tsix in Ma2L (Figure 5C), and to the Tsix promoter in ΔPas34 (Figure 5D), which, although strongly repressed, still recruits significant levels of RNAPII [12]. These observations, made both in wild-type cells and in two independent Tsix-mutant ES cell lines, strongly support the hypothesis that RNAPII accumulation is involved in establishing the H3K27me3 boundary. Importantly, when Tsix transcription across Xist is restored through the deletion of the transcriptional STOP signal of Ma2L to generate Ma1L, the resulting accumulation of RNAPII at the Tsix 3'-end (Figure 5B) is accompanied by the restoration of the boundary of H3K27me3 at its natural location (Figure 2B).

Figure 5.

Systematic accumulation of Tsix-associated RNA Polymerase II (RNAPII) at the limit of the H3K27 tri-methylation domain of the Xic in undifferentiated embryonic stem (ES) cells. (A) Profile of RNAPII distribution in wild-type male ES cells (CK35 cell line). A schematic representation of the Xist/Tsix locus is shown (top). Red and green arrows indicate the orientation of Tsix and Xist transcription units, respectively. The orange box represents the Xite locus. The purple box corresponds to the DXPas34 enhancer. (B) Distribution of RNAPII at the Tsix 3' region in wild-type (CK35, in black) and three different Tsix-mutant male ES cell lines (Ma2L in red, ΔPas34 in yellow and AV in orange). The RNAPII profile is also shown for the corresponding Ma2L control, Ma1L (in grey). The AV cell line, derived from CK35 wild-type cells, carries a 15-kb-long deletion encompassing the major Tsix promoter. (C-E) RNAPII accumulation in three independent Tsix mutant male ES cells: Ma2L (C), ΔPas34 (D) and AV (E). A schematic representation of the region analyzed in each ChIP assay is shown (top). The colour code of the genetic elements is the same as in (A). In (C), the position of the transcriptional STOP signal introduced in the Ma2L cell line is indicated. In (D, E), arrows indicate position of the deletions introduced to generate ΔPas34 and AV, respectively. (F) ChIP analysis of H3K27 tri-methylation in wild-type (CK35, in black) and AV male ES cells (in red). Dotted lines indicate the position of the 15-kb region deleted in the AV cell line.

According to such an hypothesis, mutations deleting the promoter region of Tsix should induce the spreading of H3K27me3 up to the next accumulation of RNAPII molecules. To address this, we exploited the male AV cell line, in which 15 kb encompassing the Tsix promoter have been deleted, resulting, similarly to ΔPas34 and Ma2L, in a strong reduction of Tsix transcription across Xist [12], and in the absence of RNAPII accumulation at the endogenous Tsix 3'-end (Figure 5B). The extent of the deletion carried by AV results in the Xite locus, a complex enhancer region with intrinsic non-coding transcriptional activity, acting on the major Tsix promoter [22-24], and the minor distal promoter of Tsix [21] being brought in the vicinity of the Xist 3'-end (Figure 5E). Interestingly, we could detect a low but significant accumulation of RNAPII at the junction of the deletion, some 3 kb downstream of the Xist 3'-end (Figure 5E), which likely results from non-coding transcription events initiating either at Xite or at the minor Tsix promoter and terminating before reaching Xist.

Similarly to Ma2L and ΔPas34, the lack of accumulating RNAPII at the Tsix 3'-end in AV (Figure 5B) correlates with an extension of the hotspot domain of H3K27me3 to within Xist (Figure 5F). Interestingly, upstream of the deletion junction (positions 0 to 107,000), levels of this repressive mark remain similar to that of wild-type cells. Thus, in AV, the novel boundary of the H3K27me3 domain also corresponds to the ectopic accumulation of RNAPII at the shortened region located in between Xite and Xist. In summary, our results show in five different genetic contexts (wild type, Ma1L, Ma2L, ΔPas34, and AV cells) a perfect correlation between the limit of the H3K27me3 domain and the accumulation of Tsix-associated RNAPII. These data strongly suggest that, in wild-type cells, the accumulation of RNAPII at the Tsix 3'-end forms the molecular basis of the boundary activity of Tsix.

Distal effects of Tsix on Xic chromatin and Cnbp2 and Xpct gene expression

In addition to its effect on the hotspot boundary, changing the extent and/or levels of Tsix transcription was found to affect H3K27me3 levels within the hotspot itself (Figures 2 and 5F), with increased levels observed in particular in Ma2L and AV and, to a lesser extent, in ΔPas34. This is in agreement with the hypomorphic nature of the ΔPas34 mutation (in which some 10% of Tsix RNA remains expressed) [12], and indicates that 90% reduction of Tsix activity is sufficient to deregulate the natural hotspot boundary but not to allow increased enrichment of H3K27me3 at the hotspot itself. The perfect superposition of H3K27me3 levels in the proximal part of the Xic (across Chic1 and Tsx) between control and mutant cells, as well as the absence of changes of H4K4me2 and me3 levels (Figure 4), reinforces the significance of this slight increase in H3K27me3 observed within the hotspot region. Importantly, this increase is also observed at Xpct, as confirmed by the analysis of 43 independent primer pairs and the use of an independent anti-H3K27me3 antibody (Additional file 2).

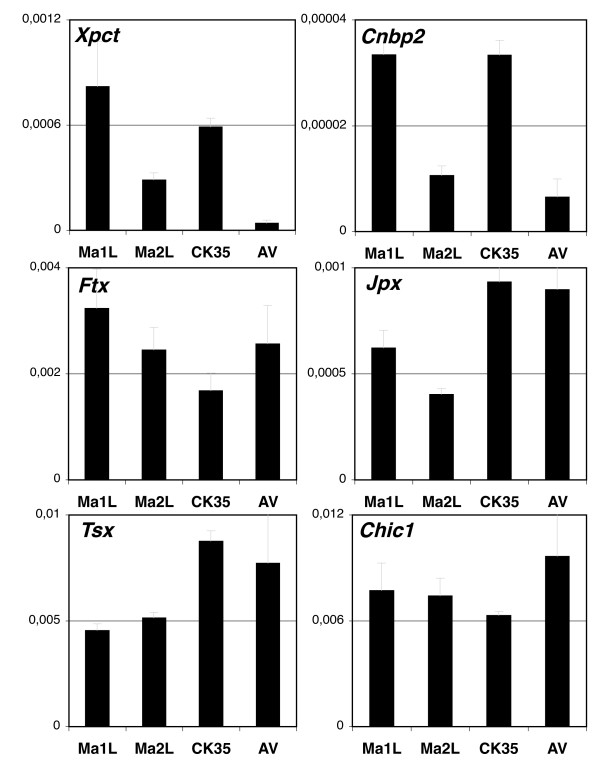

This unexpected long-distance effect of Tsix on Xic chromatin prompted us to determine the impact of Tsix on the expression of genes lying within the Xic. The expression of Xpct, Cnbp2, Ftx, Jpx, Tsx and Chic1 was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR in control and two independent Tsix-mutant male ES cells (Figure 6). In agreement with the low and Tsix-independent levels of H3K27me3 in the proximal part of the Xic, expression levels of Tsx and Chic1 were found to be unaffected by the loss of Tsix. In contrast, we detected a marked down-regulation of Xpct and Cnbp2 transcript levels in both the Ma2L and AV mutants (Figure 6) compared to their respective controls. We conclude that Tsix controls tri-methylation of H3K27 across a large region extending over more than 300 kb, from Xpct to Tsix, and impacts on expression levels of some of the genes located within this region.

Figure 6.

Tsix transcription affects the expression of genes located in the distal part of the Xic. RT-PCR analysis of several genes lying within the Xic: Xpct, Cnbp2, Ftx, Jpx, Tsx and Chic1 in different embryonic stem cells, after normalization to Arpo PO transcript levels.

Discussion

In this study, we have used the X-inactivation centre as a model to understand the impact of non-coding transcription in structuring and partitioning chromatin domains within a developmentally regulated region. Focusing in particular on a large heterochromatic-like domain that flanks the Xist master locus, this study has revealed new functions for the Tsix antisense transcript in controlling levels and distribution of H3K27me3 together with gene expression over an extended sub-region of the Xic.

Long-range control of H3K27me3 levels by non-coding transcripts

The existence of antisense non-coding RNAs responsible for monoallelic gene expression establishment and/or maintenance at both the Xic (such as Tsix) and autosomal imprinted domains is one of the most striking molecular parallels between X-inactivation regulation and genomic imprinting [25]. Surprisingly, however, although antisense transcripts controlling autosomal imprinting, such as Air and Kcnq1ot1, have been shown to repress both overlapping and distal genes through methylation of both H3K27 and H3K9 [26-28], existing data concerning Tsix favoured a role as a specific regulator of Xist. We have now challenged this conclusion by showing that Tsix fine-tunes H3K27me3 at the hotspot itself, and is required for appropriate expression of Cnbp2 and Xpct genes. Interestingly, the modification of H3K27me3 levels did not affect the methylation of H3K4 and H3K9 (Additional file 3). It appears, therefore, that regulation of H3K27me3 is independent of that of H3K9me2 (as shown in G9a-null ES cells [19]), and vice versa.

The increase in H3K27me3 levels at the hotspot observed in ES lines harbouring a mutated Tsix allele could be explained by the increase of Xist RNA that characterizes Tsix-null ES cells [11,12], which could lead to Xist RNA spreading and silencing in cis. Interestingly, the recent demonstration that, in undifferentiated ES cells, both Xist and Tsix RNAs interact with the polycomb machinery required to tri-methylate H3K27 (PRC2) [29] provides a potential molecular scenario accounting for our results. In this model, both Xist and Tsix RNAs compete for PRC2, with Xist RNA-PRC2 acting as a trigger of methylation at the hotspot region, and Tsix RNA acting as a competitor that inhibits the formation or activity of the methylating Xist RNA-PRC2 complex. This implies that, when Xist RNA-PRC2 interactions overcome that of Tsix RNA-PRC2, such as in Tsix-mutant cells, the level of methylation within the hotspot increases.

Complex control of Xist chromatin by Tsix

The molecular mechanism of the Tsix-dependent regulation of Xist transcription has been linked to complex chromatin modifications of the Xist locus. The Xist promoter region was shown to be abnormally enriched for euchromatin-associated histone marks and depleted for heterochromatin-associated modifications in Tsix-truncated male ES cells [8], a result that we have confirmed in the present study using 383 primer pairs. Similar to what was observed in terminally differentiated cells derived from male embryos carrying a Tsix-truncated allele [15], we show in this report that such an accumulation of active chromatin marks is maintained, or even increased, during differentiation of Tsix-truncated cells (Additional file 4), correlating with Xist transcription upregulation [8,12]. We conclude that Tsix controls Xist transcription through repression in cis of the Xist promoter chromatin.

In addition to inducing a repressive chromatin structure at the Xist promoter, Tsix generates an 'open' chromatin state along Xist by triggering H3K4me2 on the one hand [9] and blocking H3K27me3 enrichment on the other [8,16,17]. Tsix therefore appears to have dual effects on Xist chromatin, 'opening' the chromatin structure along Xist but repressing it at the Xist promoter itself. What might be the function of the H3K27me3-protective activity of Tsix? Since Tsix-mutant ES cells devoid of H3K27me3 at Xist hyperactivate Xist transcription on differentiation [16], it appears that encroachment of this repressive mark renders Xist activation less efficient, probably by inhibition of transcription elongation. Interestingly, no sign of H3K27me3 could be detected along Xist in early differentiating female or male wild-type ES cells, despite the analysis of 58 positions along Xist, including the Xist promoter region. Thus, H3K27me3 at Xist does not appear to play any role in the normal regulation of Xist expression, neither from the active nor the inactive X chromosome. We propose that upon loss of Tsix expression during differentiation, the Xist promoter chromatin shifts into euchromatin under a global context devoid of H3K27me3. This should favour both the recruitment of the transcriptional machinery at the Xist promoter and efficient Xist transcription elongation.

Moreover, given that the Xist/Tsix region is involved in X-chromosome pairing [30,31], and that Tsix-mutant cells do not perform this pairing event appropriately [30], we propose that the inhibition of H3K27me3 at Xist by Tsix is required for the establishment of Xic-Xic interactions involving the Xist/Tsix region. This would ensure accurate pairing of the X chromosomes and efficient Xist upregulation.

Tsix transcription as a chromatin barrier element

Our extensive analysis of H3K27me3 within the Xic has revealed that a large part of the H3K27me3 hotspot is located between the 3'-ends of two expressed non-coding genes, Tsix and Ftx, suggesting that transcription of both genes is constraining the H3K27 methylation to the region in between. This is reminiscent of the situation recently described for mouse chromosome 17, where large domains or BLOCs of H3K27me3 are flanked by active genes [4]. Importantly, our ChIP-PCR analysis of the Xic is highly similar to that obtained from ChIP-Seq experiments performed by others [32] (Additional file 5).

Based on the localization and characterization of the boundary of the H3K27me3-rich domain in both wild-type and four independent Tsix-mutant ES cells, our results strongly indicate that H3K27me3 at Xist results from a spreading process initiated at the hotspot. Under this scenario, it is noteworthy that the absence of methylation at Xist observed in differentiating cells, when Tsix is silenced, correlates with a global reduction of H3K27 tri-methylation within the hotspot. Therefore, we conclude that two mechanisms have evolved in order to prevent Xist heterochromatinisation: in undifferentiated ES cells, active Tsix transcription constrains the hotspot domain to its 3'-end, whilst in differentiating cells Tsix silencing coincides with the loss of H3K27me3 in the hotspot, thus preventing the spreading of such a modification into Xist.

It is interesting to note that the boundary of the H3K27me3 domain located at the Tsix 3'-end appears devoid of H3K4me3 (Figure 4) and H3K9 acetylation (Additional file 6), two marks frequently associated with chromatin boundary elements [33]. In addition, although we have previously shown that the insulator protein CTCF is bound at the Tsix 3'-end [8], this binding is maintained upon Tsix truncation [8], clearly demonstrating that CTCF is not a formal obstacle to the spreading of H3K27 tri-methylation within the Xic. Other activities, likely related to transcription, should therefore be important for such barrier activity. In this regard, the systematic accumulation of RNAPII, either ectopic or at the natural end of Tsix, strongly suggests that the RNAPII accumulating at the 3'-extremity of Tsix provides the molecular basis for the boundary function of Tsix transcription. These data are reminiscent of those from other systems where RNA Polymerase III transcription machinery has been shown to delimit chromatin domains. Examples include a tRNA transcription unit that acts as a barrier to the spread of repressive chromatin [34], and inverted repeat boundary elements flanking the fission yeast mating-type heterochromatin domain that have been shown to recruit TFIIIC to block heterochromatin spreading [35]. The high density of RNAPII accumulating within the 4-kb region at the 3'-end of Tsix might induce a local gap in the nucleosome array [36] that would block the spread of H3K27me3 into Xist. Preliminary studies do not, however, favour this hypothesis, as the distribution of histone H3 is similar across the boundary region and in flanking domains (data not shown). Hence, we speculate here that yet unknown activities associated with the RNAPII complex transcribing Tsix are directly responsible for blocking the spread of H3K27me3. One candidate is the UTX H3K27 demethylase, which was shown in Drosophila to interact with the elongating form of RNAPII [37]. Altogether, these observations led us to propose that the accumulation of unproductive RNAPII at the 3'-end of Tsix functions as a genomic landmark protecting Xist from H3K27 tri-methylation. This illustrates the recent idea that barriers to heterochromatin spreading might operate by exploiting the function of other gene-regulatory mechanisms, without involving specialized apparatus dedicated to such function [33]. In agreement with this, developmentally regulated activation of a SINE element in mammals was recently shown to function as a domain boundary [38].

Conclusion

Given the large extent of developmentally regulated non-coding transcription of unknown function recently discovered in mammalian genomes [39], and the Xic-wide chromatin-organizing function of Tsix that we report here, it is tempting to speculate that non-coding transcription might generally function as organizer of distinct chromatin domains required to establish appropriate expression patterns of adjacent classical protein-coding genes. Whether coding transcription can play a similar role under specific circumstances, as recently suggested [4], remains to be investigated.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

ES cell lines were grown in DMEM, 15% foetal calf serum, and 1,000 U/ml LIF (Chemicon/Millipore, Billerica MA, USA). Female LF2 ES cells were cultured on gelatin-coated plates in the absence of feeder cells. Male Ma1L, Ma2L (a kind gift of R. Jaenisch), CK35, ΔPas34 and AV ES cells were cultured on Mitomycin C-treated male embryonic fibroblast feeder cells, which were removed by adsorption before chromatin and RNA extractions. To induce ES cell differentiation, cell lines were plated on gelatin-coated flasks and cultured in DMEM, 10% foetal calf serum, supplemented with retinoic acid at a final concentration of 10-7 M. The medium was changed daily throughout differentiation. Retinoic acid-treated ES cell lines exhibited morphological features of differentiated cells. Differentiation was also evaluated by Oct3/4 and Nanog expression analysis by real-time PCR (data not shown).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

ChIP assays were performed as previously described [8]. The antibodies RNAPII (Euromedex, Souffelweyersheim, France), H3K4me2, H3K9me3, H3K9Ac, and H3K27me3 (Upstate Biotechnology/Millipore, Billerica MA, USA) and H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) were used at 1:500, 1:100, 1:100, 1:100, 1:500, 1:250 and 1:100 dilutions, respectively, to immunoprecipitate an equivalent 20 μg of DNA in ChIP assays. Each assay was performed two to six times on independent chromatin preparations to control for sample variation. To standardize between experiments, we calculated the percentage of immunoprecipitation by dividing the value of the IP by the value of the corresponding input, both values first being normalized for dilution factors.

Real-time PCR analysis of ChIP assays

To analyze ChIP experiments, real-time PCR assays were performed in 384-well plates. The primers (Additional file 7) used for the ChIP assays were designed automatically to produce 90- to 140-base-pair amplicons that cover the Xic region spanning from position 100,532,247 to 100,832,343 on NCBI build 37. A program was written with the aim of producing high quality primers and maximizing coverage in this region (available upon request). The program accesses our local mouse genome database in order to extract the sequence designated as a template, and to mask all sequence variations and repeats based on the NCBI mouse genome build release 37. This template is passed to Primer 3 with the following minimum, optimum, and maximum values applied: GC contents of 30%, 50% and 80%; and Tm of 58°C, 60°C, and 61°C. The resulting primers are further analyzed by sequence homology using BLAST and the mouse genome as the query sequence to eliminate those that can produce more than one PCR product, and to filter out those where the log base 10 of significant hits per pair exceeds 2. Besides the GC content and Tm values already mentioned, our program also screens for long runs of identical nucleotides, and G/C stretches at the 3'-ends. For all primer pairs, PCR efficiencies were verified to be similar.

In addition to the automatic primer selection strategy, liquid handling of the 384-well plate was performed with a Baseplate robotic workstation (The Automation Partnership, Hertfordshire, UK). The composition of the quantitative PCR assay included 2.5 μl DNA (the immunoprecipitated DNA or the corresponding input DNA), 0.5 μM forward and reverse primers, and 1X Power SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA, USA). The amplifications were performed as follows: 2 minutes at 95°C, 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 60 s in the ABI/Prism 7900HT real-time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems). The real-time fluorescent data from quantitative PCR were analyzed with the Sequence Detection System 2.3 (Applied Biosystems).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Random-primed RT was performed at 42°C with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with 4 μg of total RNA isolated from cell cultures with RNable (Eurobio, Les Ulis, France). Control reactions lacking enzyme were verified negative. Quantitative real-time PCR measurements using SYBR Green Universal Mix were performed in duplicates, and Arpo P0 transcript levels were used to normalize between samples.

Abbreviations

ChIP: chromatin immunoprecipitation; ES: embryonic stem; RNAPII: RNA Polymerase II; Xic: X-inactivation centre.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

PN conceived of the study, designed, carried out and analyzed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. SC carried out and analyzed the experiments, and co-wrote the manuscript. MF carried out the bioinformatic studies for designing the ChIP primer pairs, CC and SV helped to carry out the experiments, PC participated in drafting the manuscript, and PA and CR conceived of the study and co-wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Enrichment for H3K27 tri-methylation extends towards Cnbp2 and Xpct genes. The diagram at the top represents the 500-kb region analyzed in our ChIP experiments with the primer pairs used (P1 to p43). For legends, see Figure 1A. The open blue box indicates the location of the Tsix 3' region (covered by primers p20 to p31). Note that we used for this figure different sets of primer pairs and a different anti-H3K27me3 antibody (Upstate/Millipore, Billerica MA, USA) than those used for Figures 1 to 5 (Abcam).

Figure S2. Increased accumulation of H3K27 tri-methylation in the Cnbp2-Xpct region is observed in different Tsix mutant ES cells. (A) The diagram at the top is the same as in Additional file 1. (B-D) The graphs show the percentage of immunoprecipitation obtained with H3K27me3 antibodies (Upstate) at 43 different positions across the Xic in different mutants (in red) and their corresponding control cell lines (in black): (B) Ma1L/Ma2L, (C) CK35/ΔPas34, and (D) CK35/AV.

Figure S3. Tsix does not affect H3K9 di-methylation within the Xic. ChIP analysis of H3K9 di-methylation in Tsix-truncated (Ma2L, in red) and corresponding control (Ma1L, in black) embryonic stem cell lines. Locations of the primer pairs are depicted in Additional file 1.

Figure S4. The Xist promoter region is abnormally enriched in euchromatic marks in Tsix-truncated undifferentiated and differentiating embryonic stem cells. ChIP analysis of H3 modifications around the Xist 5' region in Tsix-truncated cells (Ma2L) and its corresponding control (Ma1L) male ES cells. (A) H3K4 dimethylation (H3K4me2), (B) H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3), (C) H3K9 acetylation (H3K9Ac) and (D) H3K9 trimethylation (H3K9me3). ChIP experiments were performed on undifferentiated embryonic stem cells (d0; black and orange lines for Ma1L and Ma2L, respectively) and after 4 days of differentiation with retinoic acid (d4; blue and red lines for Ma1L and Ma2L, respectively).

Figure S5. Comparison of ChIP-PCR and available ChIP-Seq data. A schematic representation of the 300-kb region analyzed in our ChIP experiments is shown at the top. Bottom: results obtained for H3K4me2, H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 from our ChIP-PCR (graphs in black) experiments and from [32] (in colour).

Figure S6. H3K9 acetylation does not mark the boundary of the H3K27 tri-methylated domain located at the Tsix 3' end. A schematic representation of the 300-kb region analyzed in our ChIP experiments is shown at the top. For legends, see Figure 1A. ChIP analysis of H3K27me3 (in black) and H3K9 acetylation (H3K9Ac, in red) in wild-type male embryonic stem cells (Ma1L). ChIP assays were performed using the set of 383 primers pairs.

Figure S7. Primers used in the 384-well PCR plate-based analysis.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Sandra Luikenhuis and Rudolf Jaenisch for the kind gift of Ma1L and Ma2L cell lines, as well as to Andrew Oldfield and Mikael Attia for scientific discussions. This work was supported by the Agence National pour la Recherche (ANR, contracts 05-JCJC-0166-01 and 07-BLAN-0047-01), the Epigenome Network of Excellence (NoE) and the French Ministry of Research under the Action Concertée Incitative, contract number 032526.

Contributor Information

Pablo Navarro, Email: pnavarro@pasteur.fr.

Sophie Chantalat, Email: chantalat@cng.fr.

Mario Foglio, Email: foglio@cng.fr.

Corinne Chureau, Email: cchureau@pasteur.fr.

Sébastien Vigneau, Email: sebastien.vigneau@gmail.com.

Philippe Clerc, Email: pclerc@pasteur.fr.

Philip Avner, Email: pavner@pasteur.fr.

Claire Rougeulle, Email: claire.rougeulle@univ-paris-diderot.fr.

References

- Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Kamal M, Lindblad-Toh K, Bekiranov S, Bailey DK, Huebert DJ, McMahon S, Karlsson EK, Kulbokas EJ, 3rd, Gingeras TR, Schreiber SL, Lander ES. Genomic maps and comparative analysis of histone modifications in human and mouse. Cell. 2005;120:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, Jaenisch R, Wagschal A, Feil R, Schreiber SL, Lander ES. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauler FM, Sloane MA, Huang R, Regha K, Koerner MV, Tamir I, Sommer A, Aszodi A, Jenuwein T, Barlow DP. H3K27me3 forms BLOCs over silent genes and intergenic regions and specifies a histone banding pattern on a mouse autosomal chromosome. Genome Res. 2009;19:221–233. doi: 10.1101/gr.080861.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc P, Avner P. Multiple elements within the Xic regulate random X inactivation in mice. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2003;14:85–92. doi: 10.1016/S1084-9521(02)00140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payer B, Lee JT. X chromosome dosage compensation: how mammals keep the balance. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:733–772. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng K, Pullirsch D, Leeb M, Wutz A. Xist and the order of silencing. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:34–39. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro P, Page DR, Avner P, Rougeulle C. Tsix-mediated epigenetic switch of a CTCF-flanked region of the Xist promoter determines the Xist transcription program. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2787–2792. doi: 10.1101/gad.389006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro P, Pichard S, Ciaudo C, Avner P, Rougeulle C. Tsix transcription across the Xist gene alters chromatin conformation without affecting Xist transcription: implications for X-chromosome inactivation. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1474–1484. doi: 10.1101/gad.341105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JT, Davidow LS, Warshawsky D. Tsix, a gene antisense to Xist at the X-inactivation centre. Nat Genet. 1999;21:400–404. doi: 10.1038/7734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey C, Navarro P, Debrand E, Avner P, Rougeulle C, Clerc P. The region 3' to Xist mediates X chromosome counting and H3 Lys-4 dimethylation within the Xist gene. Embo J. 2004;23:594–604. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigneau S, Augui S, Navarro P, Avner P, Clerc P. An essential role for the DXPas34 tandem repeat and Tsix transcription in the counting process of X chromosome inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7390–7395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602381103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JT, Lu N. Targeted mutagenesis of Tsix leads to nonrandom X inactivation. Cell. 1999;99:47–57. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luikenhuis S, Wutz A, Jaenisch R. Antisense transcription through the Xist locus mediates Tsix function in embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:8512–8520. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.24.8512-8520.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sado T, Hoki Y, Sasaki H. Tsix silences Xist through modification of chromatin structure. Dev Cell. 2005;9:159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata S, Yokota T, Wutz A. Synergy of Eed and Tsix in the repression of Xist gene and X-chromosome inactivation. Embo J. 2008;27:1816–1826. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun BK, Deaton AM, Lee JT. A transient heterochromatic state in Xist preempts X inactivation choice without RNA stabilization. Mol Cell. 2006;21:617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard E, Rougeulle C, Arnaud D, Avner P, Allis CD, Spector DL. Methylation of histone H3 at Lys-9 is an early mark on the X chromosome during X inactivation. Cell. 2001;107:727–738. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00598-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougeulle C, Chaumeil J, Sarma K, Allis CD, Reinberg D, Avner P, Heard E. Differential histone H3 Lys-9 and Lys-27 methylation profiles on the X chromosome. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5475–5484. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5475-5484.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augui S, Filion GJ, Huart S, Nora E, Guggiari M, Maresca M, Stewart AF, Heard E. Sensing X chromosome pairs before X inactivation via a novel X-pairing region of the Xic. Science. 2007;318:1632–1636. doi: 10.1126/science.1149420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sado T, Wang Z, Sasaki H, Li E. Regulation of imprinted X-chromosome inactivation in mice by Tsix. Development. 2001;128:1275–1286. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boumil RM, Ogawa Y, Sun BK, Huynh KD, Lee JT. Differential methylation of Xite and CTCF sites in Tsix mirrors the pattern of X-inactivation choice in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2109–2117. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2109-2117.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa Y, Lee JT. Xite, X-inactivation intergenic transcription elements that regulate the probability of choice. Mol Cell. 2003;11:731–743. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavropoulos N, Rowntree RK, Lee JT. Identification of developmentally specific enhancers for Tsix in the regulation of X chromosome inactivation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2757–2769. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2757-2769.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reik W, Lewis A. Co-evolution of X-chromosome inactivation and imprinting in mammals. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:403–410. doi: 10.1038/nrg1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ideraabdullah FY, Vigneau S, Bartolomei MS. Genomic imprinting mechanisms in mammals. Mutat Res. 2008;647:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey RR, Mondal T, Mohammad F, Enroth S, Redrup L, Komorowski J, Nagano T, Mancini-Dinardo D, Kanduri C. Kcnq1ot1 antisense noncoding RNA mediates lineage-specific transcriptional silencing through chromatin-level regulation. Mol Cell. 2008;32:232–246. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terranova R, Yokobayashi S, Stadler MB, Otte AP, van Lohuizen M, Orkin SH, Peters AH. Polycomb group proteins Ezh2 and Rnf2 direct genomic contraction and imprinted repression in early mouse embryos. Dev Cell. 2008;15:668–679. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Sun BK, Erwin JA, Song JJ, Lee JT. Polycomb proteins targeted by a short repeat RNA to the mouse X chromosome. Science. 2008;322:750–756. doi: 10.1126/science.1163045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacher CP, Guggiari M, Brors B, Augui S, Clerc P, Avner P, Eils R, Heard E. Transient colocalization of X-inactivation centres accompanies the initiation of X inactivation. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:293–299. doi: 10.1038/ncb1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu N, Tsai CL, Lee JT. Transient homologous chromosome pairing marks the onset of X inactivation. Science. 2006;311:1149–1152. doi: 10.1126/science.1122984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen TS, Ku M, Jaffe DB, Issac B, Lieberman E, Giannoukos G, Alvarez P, Brockman W, Kim TK, Koche RP, Lee W, Mendenhall E, O'Donovan A, Presser A, Russ C, Xie X, Meissner A, Wernig M, Jaenisch R, Nusbaum C, Lander ES, Bernstein BE. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature. 2007;448:553–560. doi: 10.1038/nature06008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaszner M, Felsenfeld G. Insulators: exploiting transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:703–713. doi: 10.1038/nrg1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms TA, Miller EC, Buisson NP, Jambunathan N, Donze D. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae TRT2 tRNAThr gene upstream of STE6 is a barrier to repression in MATalpha cells and exerts a potential tRNA position effect in MATa cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5206–5213. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noma K, Cam HP, Maraia RJ, Grewal SI. A role for TFIIIC transcription factor complex in genome organization. Cell. 2006;125:859–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor J. Dynamic nucleosomes and gene transcription. Trends Genet. 2006;22:320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ER, Lee MG, Winter B, Droz NM, Eissenberg JC, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A. Drosophila UTX is a histone H3 Lys27 demethylase that colocalizes with the elongating form of RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1041–1046. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01504-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunyak VV, Prefontaine GG, Nunez E, Cramer T, Ju BG, Ohgi KA, Hutt K, Roy R, Garcia-Diaz A, Zhu X, Yung Y, Montoliu L, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Developmentally regulated activation of a SINE B2 repeat as a domain boundary in organogenesis. Science. 2007;317:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1140871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:155–159. doi: 10.1038/nrg2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chureau C, Prissette M, Bourdet A, Barbe V, Cattolico L, Jones L, Eggen A, Avner P, Duret L. Comparative sequence analysis of the X-inactivation center region in mouse, human, and bovine. Genome Res. 2002;12:894–908. doi: 10.1101/gr.152902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Enrichment for H3K27 tri-methylation extends towards Cnbp2 and Xpct genes. The diagram at the top represents the 500-kb region analyzed in our ChIP experiments with the primer pairs used (P1 to p43). For legends, see Figure 1A. The open blue box indicates the location of the Tsix 3' region (covered by primers p20 to p31). Note that we used for this figure different sets of primer pairs and a different anti-H3K27me3 antibody (Upstate/Millipore, Billerica MA, USA) than those used for Figures 1 to 5 (Abcam).

Figure S2. Increased accumulation of H3K27 tri-methylation in the Cnbp2-Xpct region is observed in different Tsix mutant ES cells. (A) The diagram at the top is the same as in Additional file 1. (B-D) The graphs show the percentage of immunoprecipitation obtained with H3K27me3 antibodies (Upstate) at 43 different positions across the Xic in different mutants (in red) and their corresponding control cell lines (in black): (B) Ma1L/Ma2L, (C) CK35/ΔPas34, and (D) CK35/AV.

Figure S3. Tsix does not affect H3K9 di-methylation within the Xic. ChIP analysis of H3K9 di-methylation in Tsix-truncated (Ma2L, in red) and corresponding control (Ma1L, in black) embryonic stem cell lines. Locations of the primer pairs are depicted in Additional file 1.

Figure S4. The Xist promoter region is abnormally enriched in euchromatic marks in Tsix-truncated undifferentiated and differentiating embryonic stem cells. ChIP analysis of H3 modifications around the Xist 5' region in Tsix-truncated cells (Ma2L) and its corresponding control (Ma1L) male ES cells. (A) H3K4 dimethylation (H3K4me2), (B) H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3), (C) H3K9 acetylation (H3K9Ac) and (D) H3K9 trimethylation (H3K9me3). ChIP experiments were performed on undifferentiated embryonic stem cells (d0; black and orange lines for Ma1L and Ma2L, respectively) and after 4 days of differentiation with retinoic acid (d4; blue and red lines for Ma1L and Ma2L, respectively).

Figure S5. Comparison of ChIP-PCR and available ChIP-Seq data. A schematic representation of the 300-kb region analyzed in our ChIP experiments is shown at the top. Bottom: results obtained for H3K4me2, H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 from our ChIP-PCR (graphs in black) experiments and from [32] (in colour).

Figure S6. H3K9 acetylation does not mark the boundary of the H3K27 tri-methylated domain located at the Tsix 3' end. A schematic representation of the 300-kb region analyzed in our ChIP experiments is shown at the top. For legends, see Figure 1A. ChIP analysis of H3K27me3 (in black) and H3K9 acetylation (H3K9Ac, in red) in wild-type male embryonic stem cells (Ma1L). ChIP assays were performed using the set of 383 primers pairs.

Figure S7. Primers used in the 384-well PCR plate-based analysis.