Abstract

Background

Late-onset sepsis in the premature infant is frequently revealed by severe, unusual and recurrent bradycardias. In view of the high morbidity and mortality associated with infection, reliable markers are needed.

Objectives

It was the aim of this study to determine if heart rate (HR) behavior may help the diagnosis of infection in premature infants with such cardiac decelerations.

Methods

Electrocardiogram recordings were collected in 51 premature infants with a postmenstrual age < 33 weeks with frequent bradycardias. Newborns in the sepsis group (C-reactive protein increase and positive blood culture) were compared with a no-sepsis group (C-reactive protein < 5 mg/l before and 24 h after recording and negative blood cultures) for their HR characteristics, i.e. RR series distribution (mean, median, skewness, kurtosis, sample asymmetry), magnitude of variability in time and frequency domain, fractal exponents (α1, α2) and complexity measurements (approximate and sample entropy). Results are presented as the median (25%, 75%).

Results

Gestational, chronological and postmenstrual age and gender were similar in the sepsis (n = 10) and nosepsis group (n = 38). Three infants had an increase in C-reactive protein but negative cultures. Low entropy measurements [approximate entropy 0.4 (0.3, 0.5) vs. 0.8 (0.6, 1); p < 0.001] and long-range fractal exponent [α2 0.78 (0.71, 0.83) vs. 0.92 (0.8, 1.1); p < 0.05] were significantly associated with sepsis. No other HR characteristic was associated with sepsis. The decrease in 0.1 units of approximate entropy was associated with an over 2-fold increase in the odds of sepsis.

Conclusion

Late-onset sepsis is associated with uncorrelated randomness of the HR. This abnormal HR behavior may help to monitor premature infants presenting with frequent and severe bradycardias.

Keywords: Bacterial infection, Computer-assisted diagnosis, Heart rate variability, Sepsis

Introduction

Late-onset sepsis, defined as a systemic infection in neonates older than 3 days, occurs in approximately 7–10% of all neonates [1] and in more than 25% of very low birth weight infants who are hospitalized in neonatal intensive care units [2]. In view of the high morbidity and mortality associated with infection, reliable markers are needed. Recurrent and severe spontaneous apneas and bradycardias frequently reveal systemic infection in the premature infant [3]. It requires prompt laboratory investigation so that treatment can start without delay. The haematological and biochemical markers that have been used in this indication require invasive procedures that cannot be frequently repeated and have a low predictive value in the early phase of sepsis [4]. Abnormal heart rate (HR) variability measurements such as a decreased approximate entropy (ApEn) [5], decreased sample entropy (SampEn) [3, 6], reduced variability and transient decelerations [7, 8], as well as increased nonstationarity [3] have been significantly associated with sepsis or sepsis-like illness in premature infants. These diagnostic tools are noninvasive, easily and rapidly available, requiring 30 min of electrocardiogram (ECG) recording. Since decelerations and nonstationarity alter the behaviour of linear and nonlinear characteristics of the HR [6], we aimed to test the accuracy as well as these parameters in discriminating between infected and noninfected infants, in a selected population of sick premature infants with frequent and severe bradycardias.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Data were obtained from a cohort of premature infants (postmenstrual age < 33 weeks and chronological age 1 72 h), hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit at the University Hospital of Rennes over 2 periods, from June 2003 to June 2004 and from January to July 2007, who presented more than 1 bradycardia per hour and/or the need for bag-and-mask resuscitation. Exclusion criteria were: ongoing inflammatory response, medication known to influence the autonomic nervous system except caffeine, intratracheal respiratory support, intracerebral lesion or malformation.

This study was approved by the local ethics committee (03/05-445). Parents were informed and consent was obtained.

Data Collection

‘Sepsis’ was defined as the combination of an inflammatory response, i.e. C-reactive protein (CRP) 15 mg/l 24 h after the recording and positive blood cultures. ‘No sepsis’ was defined as the association of an absence of inflammatory response, i.e. a CRP < 5 mg/l 24 h after the recording and negative blood cultures. ‘Isolated inflammation’ was defined as the combination of an inflammatory response and negative blood cultures.

All recordings (Powerlab system; ADInstruments, Oxfordshire, UK) were performed in the neonatal intensive care unit and consisted of a 1-hour recording at a 400-Hz sampling rate of 2 electrocardiograms. The infants were placed in bassinets, positioned on their side, wrapped in a single blanket roll, and loosely covered by another. The events were noted on the computer and they included arousal, agitation and apnea.

Extraction and Analysis of HR Variability Parameters

Data analysis was conducted on home-made signal processing tools designed with the software Matlab version 6.0.0.42a, release 12 (The Mathworks, Inc., Meudon, France). One sequence of 4,096 successive cardiac cycle lengths (RR), i.e. about half an hour, was extracted from the ECG recordings.

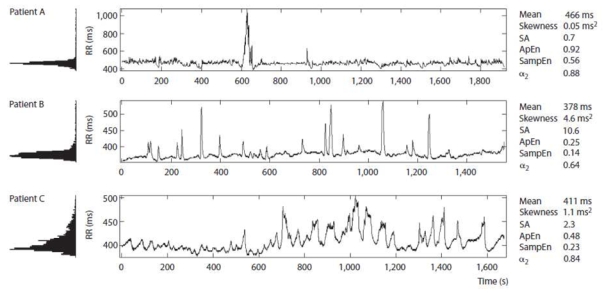

Discrete RR series of 4,096 successive beats were used for distribution, time domain, complexity and scale invariance analysis (fig. 1). The parameters were calculated on windows encompassing 1,024 beats, sliding with a 50% overlap. The median value of 4,096 beats of these calculated parameters was then used for further analysis: (1) distribution was described using moments (mean, variance, skewness and kurtosis adjusted for the bias), median and sample asymmetry [3]; (2) time domain analysis consisted of the extraction of the standard deviation (SD) and square root of the mean of squared successive differences; (3) complexity and regularity of RR series were estimated using entropy measurements (ApEn and SampEn). A high value of entropy reflects a strong irregularity and unpredictable sequence, and a low value reflects an abnormal oversimplification of these influences [9]. SampEn was used together with ApEn because this measure is known to be less sensitive to short cardiac decelerations [6] and to be more accurate in a broad range of conditions [10]. These complementary measures were calculated with fixed input variables: m = 2 and r = 0.2 of the SD for ApEn [5, 10, 11], and m = 3 and r = 0.2 for SampEn [6]. (4) The scale invariance was tested through the detrended fluctuation analysis technique [12]. The fluctuations were characterized by a self-similarity parameter (α) representing the long-range fractal correlation properties of the signal. The exponent α is 0.5 for white noise with uncorrelated randomness, 1 for 1/f noise and long-range fractal correlations, and 1.5 for Brown motion [12, 13]. We evaluated the fractal scaling exponent α1 from 4 to 40 beats, and α2 from 40 to 1,000 beats [14].

Fig. 1.

Examples of RR series of 4,096 successive beats, illustrating different aspects of HR variability. Note the asymmetry of the distribution, the low entropy and long-range autocorrelation in patient B, as well as the low entropy in patient C. Patient A (32 weeks postmenstrual age) weighed 1,165 g and had no sepsis. Patient B (30 weeks postmenstrual age) weighed 850 g and had an isolated inflammatory response. Patient C (31 weeks postmenstrual age) weighed 1,345 g and had sepsis. SA = Sample asymmetry; α2 = long-range fractal correlations.

Frequency domain analysis was performed on the 4-Hz sampled function of cubic-interpolated RR series of 4,096 successive beats. The power spectral density was estimated using Welch’s method on sliding windows of 256 s with a 50% overlap. The power spectral densities in the low frequency (LF, 0.02–0.2 Hz) and high frequency ranges (HF, 0.2–2 Hz), as well as a mean total power (0.02–2 Hz) were calculated [15, 16].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical tests were implemented using Statistica 6.1 (StatSoft France, 2004; www.statsoft.com). Data are presented as median (25%, 75%) values. The univariate comparisons between the sepsis and no-sepsis group were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test and α2 or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. The sensitivity and specificity for all possible threshold values were calculated for measurements to construct the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. This allowed evaluating the accuracy of the measured parameter to test for the diagnosis of sepsis. A multivariate modeling was then implemented. A logistic regression (generalized linear model with a logit link function) was used to predict the sepsis/no-sepsis outcome. The HR parameters were considered as the continuous predictive variables. Before modeling, the HR parameters were rescaled (multiplied by 10) in order to obtain clinically meaningful odds ratios. A 2-step selection of the available HR parameters was performed: first, only the HR variability parameters that revealed a significant level of 0.15 in the univariate analysis (Mann-Whitney tests) were selected for possible inclusion in the multivariate logistic model. The 0.15 p value threshold is commonly used in the variable selection procedures as it is recommended not to be too selective at this step [17]: the risk of a too restrictive selection would be to reject variables that are close to significance in the HR univariate analysis and may become significant in the multivariate analysis (after adjusting for the other covariates). Then, a stepwise Akaike information criterion-based selection of the best subset of covariates among the preselected set was used. In the final model, only covariates with p values < 0.05 were interpreted as statistically significant.

Results

Fifty-one ECG recordings were collected. Thirty-eight patients had no inflammatory response and negative cultures (no-sepsis group). Ten patients (sepsis group) had an inflammatory response with positive blood cultures [Staphylococcus coagulase negative (n = 6), Candida parapsilosis (n = 1), Escherichia coli (n = 1), Serratia marcescens (n = 1) and Bacillus cereus (n = 1)]. Three subjects had an increase in CRP with negative blood cultures. There were no significant differences in gender, gestational age, chronological age, postmenstrual age, hematocrit, caffeine treatment or nasal continuous positive airway pressure support between the sepsis and no-sepsis group (p 1 0.50), whereas infants with proven sepsis tended to exhibit a lower weight (p < 0.10; table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population

| No sepsis (n = 38) | Sepsis (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|

| GA at birth, weeks | 28.7 (26.5, 30) | 29.2 (26.5, 29.8) |

| Gender, M/F | 24/14 | 7/3 |

| Postmenstrual age, weeks | 30.3 (29.3, 31.9) | 30 (29.6, 30.8) |

| Chronological age, days | 13 (7, 17.5) | 9.95 (5, 22) |

| Weight, g | 1,210 (1,070, 1,410) | 1,064 (850, 1,280) |

| Caffeine, n | 14/24 | 4/6 |

| nCPAP, n | 21/17 | 8/2 |

| Hematocrit, % | 38.7 (35, 44.6) | 38 (33.9, 43.6) |

Results are presented as the median (25%, 75%). GA = Gestational age; nCPAP = nasal continuous positive airway pressure. The Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher’s exact test were used where appropriate.

RR Series Distribution and Variability

A low value of entropy was strongly associated with the risk of sepsis (p < 0.001). The ROC curve analysis confirmed good accuracy of SampEn for the diagnosis of sepsis in the studied population: the area under the ROC curve was 0.88 (95% CI 0.80–0.94). The best cut point was SampEn < 0.32, with a sensitivity of 90% (95% CI 63.3–98.5) and a specificity of 84.2% (95% CI 74–97.6). For ApEn, results were similar with an area under the ROC curve of 0.86 (95% CI 0.78–0.92). The best cut point was ApEn < 0.52, with a sensitivity of 85% (95% CI 62.1–96.6) and a specificity of 85.5% (95% CI 75.6–92.5).

Over long time scales, RR series from noninfected premature infants showed long-range correlations with α2 close to 1, whereas infants with proven sepsis exhibited significantly different patterns with α2 at about 0.8, i.e. lower and closer to white noise (p < 0.01). The area under the ROC curve was 0.70 (95% CI 0.60–0.78) for the diagnosis of sepsis (p < 0.05 vs. SampEn and ApEn ROC curves). The best cut point was α2 < 0.85, with a sensitivity of 70% (95% CI 45.7–88) and a specificity of 63.1% (95% CI 51.3–73.9).

There were no significant differences in distribution patterns (mean, median, skewness, kurtosis or sample asymmetry) and quantitative linear estimates of the RR variability (square root of the mean of squared successive differences, SD, PLF, PHF, total power, LF:HF ratio) between the sepsis and no-sepsis group (table 2).

Table 2.

Estimates of HR distribution and variability extracted from 4,096 successive beats

| No sepsis (n = 38) | Sepsis (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean, ms | 422 (397, 438) | 410.4 (393.5, 438.2) |

| Median, ms | 417.8 (400, 432.5) | 410 (385, 437.5) |

| Skewness | 0.36 (−0.09, 1.8) | 1.36 (1.18, 1.98) |

| Kurtosis | 5.27 (3.55, 10.9) | 6.86 (4.59, 7.79) |

| SA | 1.5 (0.72, 4.22) | 3.92 (2.46, 9.81) |

| SD, ms | 16.9 (11.1, 25.6) | 15.2 (11.0, 19.2) |

| rMSSD, ms | 6.13 (3.44, 10.8) | 3.81 (2.74, 8.35) |

| PLF, ms2 × 103 | 27.7 (7.5, 48.9) | 50.2 (14.5, 129.5) |

| PHF, ms2 × 103 | 4.08 (1.53, 7.37) | 8.46 (1.98, 15.7) |

| PLF: PHF ratio | 4.9 (3.99, 6.69) | 6.79 (5.12, 9.9) |

| PTP, ms2 × 103 | 33.2 (9.35, 53.5) | 58.7 (16.6, 163.1) |

| α1 | 1.44 (1.39, 1.51) | 1.47 (1.41, 1.53) |

| α2 | 0.92 (0.8, 1.07) | 0.78 (0.71, 0.83)** |

| ApEn | 0.82 (0.61, 1) | 0.43 (0.29, 0.48)* |

| SampEn | 0.54 (0.39, 0.84) | 0.22 (0.19, 0.29)* |

Results are presented as the median (25%, 75%). SA = Sample asymmetry; rMSSD = square root of the mean of squared successive differences; PTP = mean total power (0.02–2 Hz).

p < 0.001,

p < 0.05 versus the no-sepsis group. The Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher’s exact test were used where appropriate.

None of the HR distribution and variability characteristics was associated with caffeine treatment, in the whole population and in either the sepsis or no-sepsis group.

Inflammatory Response but Negative Blood Cultures

Three infants had an increase in CRP but negative blood cultures. The first case was attributed to a Haemophilus parainfluenzae isolated in tracheal aspirates after he was intubated, the second case to the onset of an enterocolitis. They had a short mean RR and low entropy estimates (lower than the 20th centile of the no-sepsis group). The first case also had a low long-range fractal exponent (2nd centile of the no-sepsis group). The third case remained unexplained and had entropy estimates and low long-range fractal exponents higher than the 20th centiles of the no-sepsis group.

Modelization of the Relationships between Sepsis and HR Characteristics

Five variables were initially included in the analysis as additional explanatory variables: weight, skewness, log10 (PLF), ApEn, SampEn and α2. The best subset logistic model included weight, ApEn, α2. Logistic regression showed the significant association between low values of entropy and the odds of having a sepsis. The decrease in 0.1 units of ApEn was associated with an over 2-fold increase in the odds of sepsis after adjustment for weight and α2 (table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios for the best subset of effects on the risk of sepsis

| Variable | Odds ratio | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Weight | 0.55 (0.25–1.22) | 0.14 |

| ApEn | 0.38 (0.18–0.8) | 0.012 |

| α2 | 0.54 (0.24–1.24) | 0.15 |

Figures in parentheses are 95% CIs. Before modeling, the HR parameters were re-scaled (multiplied by 10) in order to clinically interpret the estimated odds ratios of the model (for instance, regarding weight, a decrease or increase of 100 g is clinically more meaningful than a variation of 1 kg). Therefore, odds ratios in the final model represent a change in the estimated odds of sepsis when the weight increases by 100 g, ApEn increases by 0.1 units and α2 increases by 0.1 units. Only covariates with p values <0.05 were interpreted as statistically significant.

Discussion

Principal Findings

In a selected population of sick premature infants with frequent and severe transient decelerations of HR, the diagnosis of systemic infection was associated with abnormal HR behavior, showing lower entropy and lower long-range fractal correlation.

Meaning of the Study

Approximate or sample entropy are measures quantifying the regularity and complexity of time series [10, 11]. While a high value of entropy reflects a strong irregularity and unpredictable sequence, in relation to the multiple influences normally affecting RR, a low value reflects increased regularity, the presence of spikes (i.e. short cardiac decelerations), or both [5, 6, 9, 18]. Low HR entropy has been observed in adult endotoxemia [19] and by 1 group in neonatal systemic infection [3, 6]. The physiological mechanisms underlying this fall in entropy are not known. Even if the low entropy values that we observed are, to some extent, due to the decelerations per se [6], entropy appears relatively accurate in discriminating between infected and non-infected infants when presenting with frequent and severe transient decelerations of HR. Another nonlinear measurement of the irregularity of RR series is the quantification of their fractal scaling properties through the detrended fluctuation analysis technique. It has been suggested that scale invariance may be a central organizing principle of physiological structure and function. As in the findings of Nakamura et al. [14] in healthy premature infants and of Pikkujamsa et al. [20] in children, we found that these premature infants with frequent and severe bradycardias showed a ‘mature’ pattern of RR interval dynamics similar to healthy young adults, with complex, fractal dynamics. This finding is consistent with the findings of Nelson et al. [21] and suggests a highly adaptive cardiovascular regulatory system. Correspondingly, we observed a breakdown of this scale-invariant fractal organization in infected infants. This has been speculated to be associated with the loss of integrated physiologic responsiveness, i.e. a less adaptable system with either a totally uncorrelated randomness or a highly predictable behavior [21]. Such degradation of long-range correlation properties has been found to be associated with various pathologic states from elderly to fetus [13, 21]. HR characteristics such as SD, centiles and skewness [7] and sample asymmetry [3, 22] have been associated with sepsis or isolated inflammatory response. We were unable to find a correlation between these parameters and sepsis.

Limitations

As we observed that entropy was also decreased in 1 case of ‘isolated inflammation’ and borderline in another, we cannot formally exclude an independent effect of inflammatory response on entropy [22]. However, note that sepsis was very plausible in these 2 cases, suggesting that these patients could have been classified in the sepsis group re-enforcing the relation between sepsis and decreased entropy. Diagnostic tests with a high sensitivity and a negative predictive value are most desirable because all septic infants have to be identified [23]. In the present study, the small number of premature infants with proven sepsis and the inclusion criteria do not permit extrapolation of sensitivity, specificity and predictive values for a nonselected population of premature infants.

Implications

The diagnosis of neonatal sepsis is difficult because the clinical signs are subtle and nonspecific and none of the laboratory tests, including the CRP and blood culture, have high predictive accuracy [4]. The lack of reliable laboratory tests often results in anticipatory antimicrobial treatment.

Entropy and long-range fractal correlation are decreased in premature infants with proven sepsis and presenting with frequent and severe bradycardias. Consequently, ApEn, SampEn and α2 can be considered candidate measures, either alone or as part of a multivariable scheme, for monitoring sick infants. The uncorrelated randomness of HR behavior associated with sepsis could be of practical diagnostic use.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the COREC, Rennes, France. We thank Nathalie Costet for the statistical reviewing and Stéphanie Sergant for her valuable technical support.

References

- 1.Raymond J, Aujard Y European Study Group. Nosocomial infections in pediatric patients: A european, multicenter prospective study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21:260–263. doi: 10.1086/501755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck-Sague CM, Azimi P, Fonseca SN, Baltimore RS, Powell DA, Bland LA, Arduino MJ, McAllister SK, Huberman RS, Sinkowitz RL, et al. Bloodstream infections in neonatal intensive care unit patients: Results of a multicenter study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:1110–1116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao H, Lake DE, Griffin MP, Moorman JR. Increased nonstationarity of neonatal heart rate before the clinical diagnosis of sepsis. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:233–244. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000012743.81754.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malik A, Hui CP, Pennie RA, Kirpalani H. Beyond the complete blood cell count and c-reactive protein: A systematic review of modern diagnostic tests for neonatal sepsis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:511–516. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.6.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pincus SM, Gladstone IM, Ehrenkranz RA. A regularity statistic for medical data analysis. J Clin Monit. 1991;7:335–345. doi: 10.1007/BF01619355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lake DE, Richman JS, Griffin MP, Moorman JR. Sample entropy analysis of neonatal heart rate variability. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R789–797. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00069.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffin MP, Moorman JR. Toward the early diagnosis of neonatal sepsis and sepsis-like illness using novel heart rate analysis. Pediatrics. 2001;107:97–104. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffin MP, Lake DE, Moorman JR. Heart rate characteristics and laboratory tests in neonatal sepsis. Pediatrics. 2005;115:937–941. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pincus SM, Goldberger AL. Physiological time-series analysis: What does regularity quantify? Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H1643–1656. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.4.H1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richman JS, Moorman JR. Physiological time-series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H2039–2049. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.6.H2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pincus SM. Approximate entropy as a measure of system complexity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:2297–2301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng CK, Havlin S, Stanley HE, Goldberger AL. Quantification of scaling exponents and crossover phenomena in nonstationary heartbeat time series. Chaos. 1995;5:82–87. doi: 10.1063/1.166141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yum MK, Park EY, Kim CR, Hwang JH. Alterations in irregular and fractal heart rate behavior in growth restricted fetuses. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;94:51–58. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(00)00314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura T, Horio H, Miyashita S, Chiba Y, Sato S, Yum MK, Park EY, Kim CR, Hwang JH. Identification of development and autonomic nerve activity from heart rate variability in preterm infants alterations in irregular and fractal heart rate behavior in growth restricted fetuses. Biosystems. 2005;79:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chatow U, Davidson S, Reichman BL, Akselrod S. Development and maturation of the autonomic nervous system in premature and full-term infants using spectral analysis of heart rate fluctuations. Pediatr Res. 1995;37:294–302. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199503000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenstock EG, Cassuto Y, Zmora E. Heart rate variability in the neonate and infant: Analytical methods, physiological and clinical observations. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:477–482. doi: 10.1080/08035259950169422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pincus SM. Greater signal regularity may indicate increased system isolation. Math Biosci. 1994;122:161–181. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(94)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godin PJ, Fleisher LA, Eidsath A, Vandivier RW, Preas HL, Banks SM, Buchman TG, Suffredini AF. Experimental human endotoxemia increases cardiac regularity: Results from a prospective, randomized, crossover trial. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1117–1124. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199607000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pikkujamsa SM, Makikallio TH, Sourander LB, Raiha IJ, Puukka P, Skytta J, Peng CK, Goldberger AL, Huikuri HV. Cardiac interbeat interval dynamics from childhood to senescence: Comparison of conventional and new measures based on fractals and chaos theory. Circulation. 1999;100:393–399. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.4.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson JC, Rizwan U, Griffin MP, Moorman JR. Probing the order within neonatal heart rate variability. Pediatr Res. 1998;43:823–831. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199806000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kovatchev BP, Farhy LS, Cao H, Griffin MP, Lake DE, Moorman JR. Sample asymmetry analysis of heart rate characteristics with application to neonatal sepsis and systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2003;54:892–898. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000088074.97781.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng PC, Li K, Wong RP, Chui KM, Wong E, Fok TF. Neutrophil cd64 expression: A sensitive diagnostic marker for late-onset nosocomial infection in very low birthweight infants. Pediatr Res. 2002;51:296–303. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]