Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the population-based prevalence of keratoconus in U.S. individuals aged 65 years and older.

Design

Multi-year retrospective cross sectional claims analysis.

Methods

Fee-for-service claims from a 5% national sample of Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older were reviewed. Claims records were queried on an annual basis for the years 1999 through 2003 for ICD-9 codes specific to keratoconus. The number of beneficiaries with keratoconus related claims was counted for each calendar year.

Results

The number of beneficiaries receiving care for keratoconus rose steadily from 15.7/100,000 beneficiaries in 1999 to 18.5/100,000 in 2003, averaging 17.5/100,000 across the five years of the study. Keratoconus declined with declining age, but did not differ by gender. Keratoconus care was more prevalent in whites than in other races.

Conclusions

Keratoconus is an uncommon disease in the Medicare population. Longitudinal analysis of Medicare claims data may provide a useful tool for monitoring uncommon diseases, such as keratoconus, in the elderly.

Introduction

Little is known about the prevalence of keratoconus in the U.S. elderly population. Only one U.S. population-based analysis of keratoconus has been previously published, providing minimal information on aged individuals (1). Previous studies have used Medicare claims data to estimate the incidence and prevalence of ophthalmic disease in the elderly (2–4). In this study, we examined Medicare claims records to estimate the prevalence of keratoconus in the U.S. elderly population.

Methods

A multi-year cross sectional study design was employed. The study population was based on a national 5% sample of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries 65 years or older from 1999 to 2003, as found in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) 5% Part B Physician/Supplier Files. These annual files contain all claims submitted nationally by physicians and limited-license practitioners for inpatient and outpatient services, as well as claims from free-standing ambulatory surgical centers. . The 5% sample was obtained from CMS, which makes this information available for research purposes.

Beneficiaries included in the study were those having Medicare fee-for-service (Part B) coverage for at least part of a given calendar year. Beneficiaries who were enrolled in Medicare health maintenance organizations (HMOs) or other Medicare managed care plans for the entire calendar year were excluded from that year’s calculations, as service usage data for these individuals are not reported to CMS. Medicare railroad beneficiaries were also excluded (5).

Claims files were queried for ICD-9 codes specific to keratoconus (371.6, 371.60, 371.61 and 371.62) on a calendar year basis. A keratoconus case was defined as a beneficiary having one or more claims with keratoconus within the calendar year. Numerators were the total number of beneficiaries receiving keratoconus care within the particular year. Denominators were beneficiary person-years with Medicare coverage – representing adjustments to the actual number of beneficiaries to reflect duration of active fee-for-service Part B enrollment. Rates were calculated on a calendar year basis. Stratification of rates by demographics was performed.

Results

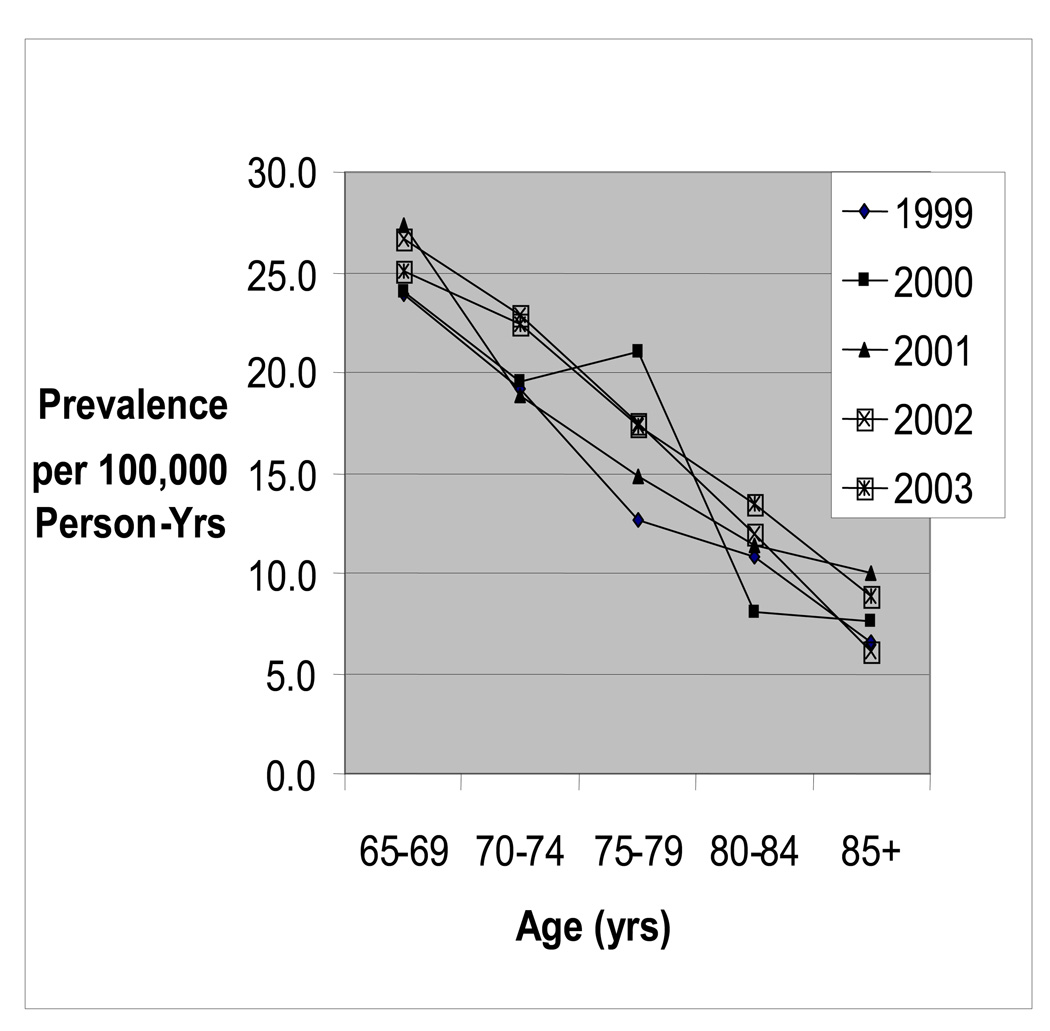

The number of individuals receiving keratoconus care rose steadily from 15.7/100,000 Medicare Part B beneficiary person-years in 1999 to 18.5/100,000 in 2003. The average across the five years of the study was 17.5/100,000 (Table 1). The rate declined with increasing age in all years of the study, averaging 25.4/100,000 in beneficiaries aged 65–69 years old, and dropping to 7.8/100,000 in beneficiaries aged 85 years and older (Figure). Keratoconus cases but did not differ by gender, but with a higher rate for whites versus blacks and other races in all years of the study (Table 2).

Table 1.

Annual Prevalence of Keratoconus per 100,000 Person-Years among Medicare Beneficiaries

| Rate | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Cases | (/100,000) |

| 1999 | 200 | 1.57 |

| 2000 | 223 | 1.73 |

| 2001 | 232 | 1.75 |

| 2002 | 252 | 1.85 |

| 2003 | 258 | 1.85 |

Figure. Prevalence of Keratoconus per 100,000 Medicare Beneficiary Person-Years by Age.

Table 2.

Annual Prevalence of Keratoconus per 100,000 Medicare Beneficiary Person-Years by Race

| Rate/100,000 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | White | Black | Other |

| 1999 | 16.8 | 6.2 | 11 |

| 2000 | 18.4 | 9.1 | 12 |

| 2001 | 18.5 | 11.6 | 10 |

| 2002 | 19.4 | 11.2 | 13 |

| 2003 | 18.7 | 18.3 | 17 |

Conclusions

Keratoconus has typically been considered a disease of youth, with an onset typically in the second or third decade of life and progression through though middle age. The disease is uncommonly seen in elderly subjects (6). The sole United States population based estimate of keratoconus to date supports its rarity in the elderly. The report, by Kennedy et al conducted in Olmsted County, Minnesota, estimated a yearly prevalence of 55/100,000 for all ages.(1) Only one individual of the 64 cases of keratoconus studied, however, was aged 65 years or older. As such, little is known about the prevalence of this disease in the elderly.

Though the differences in denominators and study design of the current study vs. that of Kennedy et al does not allow for direct comparison of the respective data, this analysis, which is the first population-based estimate of keratoconus prevalence in the U.S. elderly population, suggests that keratoconus is indeed rare among the aged, affecting approximately 18/100,000 such persons in a given year. These data also suggest that even amongst aged individuals, prevalence declines steadily with age.

Keratoconus is reported to affect all racial groups(7,8,9). Though an increased incidence in persons of Pakistani ethnicity versus whites has been reported from a single center in the United Kingdom,(10) we are unaware of any other analysis suggesting a racial predominance of this disease. As such, our finding of increased prevalence of keratoconus claims care in elderly white Medicare beneficiaries versus blacks or other races is notable.

This analysis has several limitations. Primarily, Medicare claims data are designed for billing purposes, not research. Also, for several reasons, this analysis likely represents an underestimate of the true prevalence of keratoconus in the U.S. elderly population. Individuals with keratoconus but without a claim in a particular year would not be included in the rate for that year in this analysis. This may have occurred in several ways. First, cases of keratoconus diagnosed outside of the Medicare system would not be captured by an analysis using Medicare data alone. Also, it is possible that significant number of elderly individuals with keratoconus in the Medicare population during the time of the analysis had developed stable disease managed with glasses or contact lenses. As these therapies are not routinely covered by the Medicare program, provider visits and claims for these services would also not be captured. Further, patients who had previously undergone corneal transplantation for their keratoconus may no longer have been coded by eye providers as having keratoconus, also leading to an underestimation of prevalence using claims records. Lastly, as other eye problems are accumulated with age, the diagnosis of keratoconus, especially if a stable condition for the patient, may not be coded by the provider on each visit as more acute eye problems, such as diabetic retinopathy or glaucoma, are addressed and coded. This coding preference by providers for more acute eye problems may also help explain our findings of increased prevalence in whites versus blacks and other races. As blacks and other races, such as Hispanics, may have a higher prevalence of chronic eye diseases such as glaucoma and diabetes versus whites(11)(12) and may have their visits preferentially coded for these more acute conditions rather than stable, underlying keratoconus. Lastly, it is possible that the rate increase over the five year period we observed was due to increasingly more frequent eye care visits within the existing keratoconus population.

In summary, in this analysis, we provide the first population-based estimate of keratoconus prevalence in the U.S. Medicare population. These data support the belief that this disease is uncommon in the elderly. Analysis of Medicare claims data, though limited in some respects, may provide a useful tool for monitoring uncommon diseases, such as keratoconus, in the elderly population.

Acknowledgements

Funding/support: National Eye Institute under DHHS Program Support Center contract 223-02-0090; Lew Wasserman Merit Award from Research to Prevent Blindness (Dr. Lee); Unrestricted Grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, NY.

Financial disclosures: SR – has received speaking honoraria and or consulting reimbursement from the Allergan; LE – none, TK has received speaking honoraria, grant support and or consulting reimbursement from the Alcon, Allergan, ISTA, BD Ophthalmic and Hyperbranch Medical corporations. RC – none. PL has received speaking honoraria, grant support and or consulting reimbursement from the Alcon, Allergan, Pfizer and Merck corporations. The authors do not have any proprietary or commercial interests related to the reported research.

References

- 1.Kennedy RH, Bourne WM, Dyer JA. A 48-year clinical and epidemiologic study of keratoconus. Am J Opththalmol. 1986;101:267–273. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(86)90817-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee PP, Felman ZW, Osterman J, Brown DS, Sloan FA. Longitudinal prelavence of major eye diseases. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:1303–1310. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.9.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sloan FA, Brown DS, Carlisle MA, Ostermann J, Lee PP. Estimates of incidence rates with longitudinal claims data. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:1462–1468. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.10.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reeves SW, Sloan FA, Lee PP, Jaffe GJ. Uveitis in the Elderly: Epidemiological data from the National Long Term Care Medicare Cohort. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellwein LB, Urato CJ. Use of eye care and associated charges among the Medicare Population 1991 – 1998. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:804–811. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pobelle-Frasson C, Velou S, Huslin V, Massicault B, Colin J. Keratoconus: what happens with older patients? J Fr Ophtalmol. 2004;27(7):779–782. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(04)96213-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krachmer JH, Feder RS, Belin MW. Keratoconus and related noninflammatory corneal thinning disorders. Surv Ophthalmol. 1984;28:293–332. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(84)90094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabinowitz YS. Keratoconus. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42:297–319. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(97)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zadnik K, Barr JT, Edrington TB, Everett DF, Jameson M, McMahon TT, Shin JA, Sterling JL, Wagner H, Gordon MO. Baseline findings in the Collaborative Longitudinal Evaluation of Keratoconus (CLEK) Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998 Dec;39(13):2537–2546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georgiou T, Funnell CL, Cassels-Brown A, O’Conor R. Influence of ethnic origion on the incidence of keratoconus and associated atopic disease in Asians and white patients. Eye. 2004;18:379–383. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudnicka AR, Mt-Isa S, Owen CG, Cook DG, Ashby D. Variations in primary open-angle glaucoma prevalence by age, gender, and race: a Bayesian meta-analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(10):4254–4261. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong TY, Klein R, Islam FM, Cotch MF, Folsom AR, Klein BE, Sharrett AR, Shea S. Diabetic retinopathy in a multi-ethnic cohort in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006 Mar;141(3):446–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]