Abstract

Background

For three decades the Mutator system was thought to be exclusive of plants, until the first homolog representatives were characterized in fungi and in early-diverging amoebas earlier in this decade.

Results

Here, we describe and characterize four families of Mutator-like elements in a new eukaryotic group, the Parabasalids. These Trichomonas vaginalis Mutator- like elements, or TvMULEs, are active in T. vaginalis and patchily distributed among 12 trichomonad species and isolates. Despite their relatively distinctive amino acid composition, the inclusion of the repeats TvMULE1, TvMULE2, TvMULE3 and TvMULE4 into the Mutator superfamily is justified by sequence, structural and phylogenetic analyses. In addition, we identified three new TvMULE-related sequences in the genome sequence of Candida albicans. While TvMULE1 is a member of the MuDR clade, predominantly from plants, the other three TvMULEs, together with the C. albicans elements, represent a new and quite distinct Mutator lineage, which we named TvCaMULEs. The finding of TvMULE1 sequence inserted into other putative repeat suggests the occurrence a novel TE family not yet described.

Conclusion

These findings expand the taxonomic distribution and the range of functional motif of MULEs among eukaryotes. The characterization of the dynamics of TvMULEs and other transposons in this organism is of particular interest because it is atypical for an asexual species to have such an extreme level of TE activity; this genetic landscape makes an interesting case study for causes and consequences of such activity. Finally, the extreme repetitiveness of the T. vaginalis genome and the remarkable degree of sequence identity within its repeat families highlights this species as an ideal system to characterize new transposable elements.

Background

Transposable elements (TEs) are ubiquitous components of prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes and, as a consequence of their prevalence, mobility and concomitant mutagenicity [e.g., [1,2]], they can induce profound changes in genome organization and have an important evolutionary impact on expression and function of host genes [3-6]. TEs can lead to genome expansion and contraction [7-9], transduction and amplification of host gene fragments [10,11] and increase the variability of protein repertories [12-20]. Given this enormous potential as a source of genetic novelty, considerable effort has been devoted by the scientific community to the characterization of new TEs in the plethora of new genomes and transcriptomes available in public databases, particularly in organisms for which the knowledge about TEs is scarce. While some families of TEs are found across most taxa surveyed, others appear to have a restricted host distribution; the Mutator system in plants was an example of the latter. This notion was recently dispelled by the identification and extensive characterization of Mutator homologs in the first non-plant species [21-24]. Moreover, consensus sequences of new representatives of this TE family obtained from a broad range of species have been reported in Repbase Reports within the past few years: CEMUDR1-2 from Caenoharbidtis elegans [25,26]; MuDR1-2_TP in the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana [27,28]; MuDr1-2_NV in the starlet sea anemone Nematostella vectensis [29,30]; MuDR1x-2x_SM in the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea [31,32] and MuDr1x-2x_AP in the insect Acyrthosiphon pisum [33,34].

The Mutator (Mu) system was originally identified by Robertson [35] in maize as a highly mutagenic transposon system. This system is composed of diverse families that share ~220 bp terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) and create a 9 bp host sequence duplication at the insertion site [reviewed by [36]]. These elements can be either autonomous (MuDR) or nonautonomous (Mu). Transposition of Mu elements is dependent of the autonomous MuDR elements. The MuDR element in maize is 4.9 kb long and contains two open reading frames (ORFs): mudrA and mudrB. The mudrA gene product, the MURA protein of 823 amino acids, probably a transposase, contains a catalytic domain with a D34E motif (aspartic and glutamic acids separated by 34 residues) and its expression is sufficient for the somatic excision of the TE [37,38]. The transposase encoded by mudrA shares weak but significant similarity to those encoded by the IS256 group of prokaryotic insertion sequences [21]. Deletions on mudrA disable the Mutator transpositional activity [37]. The MURB protein is encoded by mudrB; while this protein's function remains undetermined, it seems to be necessary for the activity of the Mu system in maize [37,38]. Mutator-like elements (MULEs) have been identified in a wide range of plant species, such as Arabidopsis [39-41], Oryza [e.g., [42,43]], Saccharum [44,45] and different grasses [46]. Interestingly, MULEs lack the mudrB gene [36]. In maize, thale cress and rice MULEs are heterogeneous in sequence, size and structure. In particular, some elements either carry small imperfect TIRs or completely lack them [39,40].

Recently, non-plant species have been reported to harbor MULEs. Chalvet et al. [22] provided the first evidence for the presence of an active MULE in the fungus Fusarium oxysporum, the transposon Hop. It is 3,299 bp long, has TIRs of 99 bp and 9 bp target site duplication (TSD), encodes a putative transposase of 836 amino acids and has no apparent sequence specificity at the insertion site. The presence of related elements in other filamentous fungi like Magnaporthe grisae, Neurospora crassa and Aspergillus fumigatus has also been reported [22]. Neuvéglise et al. [23] identified a new type of DNA transposons, Mutyl, in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica with 7,413 bp, imperfect TIRs of 22 bp, 9 to 10 bp TSD, and two ORFs which potentially encode proteins of 459 and 1,178 amino acids. Whereas the first ORF shows no significant homology to described proteins, the second one shows similarity to a wide variety of MULE-encoded transposases. More recently, Pritham et al. [24] characterized a canonical copy of the Mutator-like element in a protist genome, Entamoeba invadens. This element, named EMULE-Ei1, is 2,882 bp long and displays structural features typical of plant MULEs, such as TIRs of 187 bp and a 9 bp flanking TSD. Moreover, it contains a single ORF that putatively encodes a 456-aa protein that shows significant similarity to the Hop transposase from F. oxysporum. In that study, homologous elements were observed in three additional Entamoeba genomes, namely E. dispar, E. hystolitica and E. moshkovskii [24].

Trichomonas vaginalis, an asexual flagellated protist [47], is an extracellular obligate human parasite of the urogenital tract [48] and a member of a deep-branching eukaryotic lineage, the Parabasalids [49]. Its genome sequence and annotation, published in 2007 by Carlton and collaborators, revealed a putative set of ~60,000, mostly intronless, protein-coding genes, endowing T. vaginalis with one of the largest gene sets among eukaryotes [9]. Interestingly, this genome was shown to be highly repetitive, with repeats and TEs comprising about two-thirds of its ~160 Mb-long sequence. Until now, only DNA transposons have been completely characterized in this species, including Mariner [50], Polintons [51], and Mavericks [52]. Among the original repeats identified in the genome of T. vaginalis were included four repeat consensus sequences with a Mutator-like profile: R210 with 2,127 bp, R130a with 1,129 bp, R119 with 2,954 bp, R165 with 2,410 bp [9]. In this report, we characterize these four T. vaginalis Mutator-like elements (TvMULEs), which we renamed as TvMULE1 (based on the R210 sequence), TvMULE2 (based on the R130a sequence, here revised regarding to sequence and structure), TvMULE3 (based on R119) and TvMULE4 (based on R165). We confirm the inclusion of the four repeats into the Mutator superfamily based on sequence, structural and phylogenetic analyses. While TvMULE1 is a member of the MuDR clade predominantly from plants, the other three TvMULEs represent a new and quite distinct Mutator lineage, expanding the taxonomic distribution and the range of functional motif of MULEs among eukaryotes.

Results

Characterization of TvMULEs: new T. vaginalis transposons

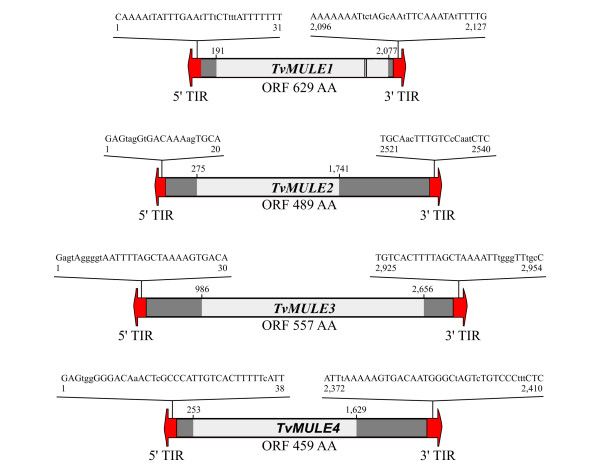

The sequence and structure of four Mutator-like consensus sequences [9] were analyzed in detail in the present study. The manual inspection of a combination of sequence similarity searches and consensus sequence building techniques (described in Methods) and the presence of putative, imperfect, terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) resulted in the definition four new Mutator-like transposable element families represented by the consensus sequence of which we termed TvMULE1, TvMULE3 and TvMULE4 (Figure 1) and TvMULE2 represented by the canonical copy contained in the contig 95978 (position 24930–27469).

Figure 1.

Structure of the T. vaginalis MULEs. Putative terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) are denoted by black arrowheads at each end of the elements. Bases that are variable between TIRs are in lowercase type. Dark gray boxes represent internal non-coding sequences. The internal region of each element (clear gray box) corresponds to an ORF that encodes putative MULEs-related transposase domains. Location of a transposase zinc finger (double black lines) is also shown.

All insertions of the four families were identified in the 17,290 contigs that make up the current genome assembly of T. vaginalis by BLASTN. A total of 61, 514, 666 and 1,204 matches revealed strong similarity to TvMULE1, TvMULE2, TvMULE3 and TvMULE4, respectively (identity >80% and E ≤ e-20). All matches were extracted by BLAST coordinates and all ORFs starting at the Met residue were predicted, excepting TvMULE2, in which the predicted ORF was only derived of the canonical copy. The four TvMULEs contain a single intronless gene. The more frequent ORF of TvMULE1, which putatively encodes a 629-aa protein (Figure 1), displayed highest similarity (43%) to a Mutator transposase (Tpase) from A. thaliana (Table 1). On the other hand, the other three TvMULEs showed similarity to three potential Mutator Tpases from the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans: the first of these (GenBank gi # 68466572) is 568-aa residues long and is very similar to the second C. albicans protein (GenBank gi # 68466277), which is 832-aa long; the third C. albicans protein (GenBank gi # 68474652), is 668-aa long. TvMULE2 matched the first C. albicans protein, and TvMULE3 and TvMULE4 showed significant similarity to the third protein with 40 and 43% similarity, respectively (Table 1). While TvMULE1 have relatively small non-coding regions, these extend to several hundred base pairs in TvMULE2, TvMULE3 and TvMULE4.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 4 Mutator-like families in the T. vaginalis genome

| Family |

Lenghta (bp) |

TIRsb (bp) |

ORFc (aa) |

First TE hit in BlastP searches against Genbank | ||||

| Descriptiond |

e value |

% IDe |

% Similarityf |

Lengthg (aa) |

||||

| TvMULE1 | 2,127 | 31 | 629 | 11994228 Arabidopsis thaliana Mutator | 1e-09 | 27 | 43 | 283 |

| TvMULE2 | 2,540 | 20 | 489 | 68466572 Candida albicans Mutator | 3e-03 | 24 | 44 | 166 |

| TvMULE3 | 2,954 | 30 | 557 | 68474652 Candida albicans Mutator | 3e-09 | 23 | 40 | 309 |

| TvMULE4 | 2,410 | 38 | 459 | 68474652 Candida albicans Mutator | 9e-12 | 25 | 43 | 235 |

a Length of consensus sequence, excepting TvMULE2 in which a canonical copy was characterized;

b Putative imperfect terminal inverted repeats;

c Length of the protein encoded by T. vaginalis TE, in amino acids (aa);

d GenBank accession number, species, TE name;

e Percent identity between T. vaginalis TE-encoded protein and hit in BlastP alignment;

f Percent similarity between T. vaginalis TE-encoded protein and hit in BlastP alignment;

g Length of query in the alignment produced by BlastP, in amino acids.

Within each of the four TvMULE families all copies were found to be nearly identical in sequence (identity >99%). This result confirms the low polymorphism obtained from average pairwise differences between copies (π) observed by Carlton et al. [9]. There, the π value was estimated as 0.9% for TvMULE1, 0.7% for TvMULE2, 1.1% for both TvMULE3 and TvMULE4. Within each family, the sequences of the 5' and 3' TIRs are nearly identical. In addition, an alignment of these putative TIRs across TvMULE families shows three positions in the 5' end and six in the 3' end are nearly perfectly conserved (not shown). The presence of polymorphism in the terminal ends within each repeat family could indicate that they do not act as the transposase recognition site, given that the internal regions of different copies are more highly conserved. Alternatively, it is possible that the binding is not specific across the entire TIR, or that some of the mutations that have accumulated since transposition actually inactivates the respective copies.

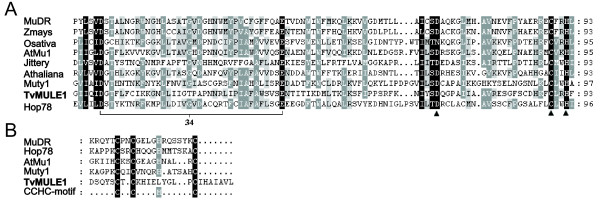

TvMULE1 shares recognized MULE structural motifs. Firstly, it has a well-conserved D34E integrase signature in the putative active site, and three residues of the transposase core conserved across a wide range of MULEs [36] are also present (Figure 2A). This conserved region corresponds to the ~130-aa domain identified by Eisen et al. [21] containing a 25-aa signature sequence [D-x(3)-G-(LIVMF)-x-(6)-(STAV)-(LIVMFFYW)-(PT)-x-(STAV)-x-(2)-(QR)-x-C-x(2)-H]. Secondly, a transposase zinc finger domain at the C-terminal region was identified, which has a nearly perfect CX2CX4HX4/6C-motif (Figure 1 and Figure 2B). This motif is found in the nucleocapsid protein of retroviruses, in several known nucleic acid binding proteins, in the copia-like retrotransposons from tobacco [53], and in Ty elements in yeast [54]. It has been proposed that this motif plays a role in a transposase-transposon interaction that takes place during transposition and/or regulation [40].

Figure 2.

Conserved domains in the Mutator protein MURA and its homologs are present in TvMULE1. A – Multiple sequence alignment of the conserved transposase domain. This alignment includes the MURA transposase from the Zea mays MuDR element (accession no. 540581), putative MURA-related transposases from the plants Zea mays (Zm-40034: accession no. 23928448, Jittery: accession no.7673677), Arabidopsis thaliana (AtMu1: accession no. AC002983.1 and At-96881: accession no. 34914922), Oryza sativa (Os-918808: accession no. 8777291), from the fungi Fusarium oxysporum (Hop-78: accession no. 30421204) and Yarrowia lipolytica (Mutyl: accession no. 50556866), and from the unicellular protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis (TvMULE1: deposited in Repbase). B – Multiple sequence alignment of the zinc finger domain. Identical amino acids are shaded in black, and similar amino acids are shaded in gray. The well-conserved D34E integrase signature in the active site of Mutator is noted. The symbol (dark filled triangles) below of the alignment corresponds to other residues also well conserved across a wide range of Mutator-like elements, previously described by Lisch [36].

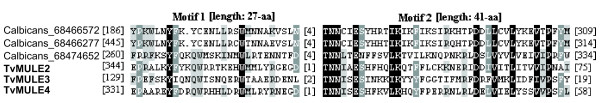

The other three TvMULEs (TvMULE2, TvMULE3 and TvMULE4) show amino acid residue contents that differ markedly from that of TvMULE1 and from those of known plant MULEs. However, these elements exhibit significant similarity to three C. albicans elements (Table 1). This observation is readily apparent from the quite new and distinct content of residues contained in two conserved motifs shared by these six elements (Figure 3). The inclusion of this extended group in the Mutator superfamily is supported by a variety of structural analyses. First, the three C. albicans proteins show significant similarity to MULEs such as Hop from F. oxysporum (GenBank gi # 30421204) and a Cucumis melo MULE (GenBank gi # 46398239); in addition, one of them (GenBank gi # 68466572) contains a conserved Mutator-like transposase domain corresponding to pfam00872 (COG3328 and CDD85084), a hallmark of Tpases of the Mutator family. Secondly, BLASTP generated significant pairwise alignments for all comparisons between these TvMULEs (2e-37<E-value<2e-13), as well as between them and the C. albicans sequences (Table 1). Thirdly, a careful characterization of motifs across 41 Mutator elements, as well as in these T. vaginalis and C. albicans repeats, revealed that the latter encode an extended motif of 36 residues (motif 1) identical to the 25-aa signature sequence of the MULE transposase core previously mentioned [see Additional file 1]. The high degree of sequence conservation of this motif [see Additional file 1] in quite distinct branches of the Mutator lineage suggests that it plays a role that is essential to the fitness of the elements.

Figure 3.

Clustal alignment of two conserved motifs found in TvMULEs and in C. albicans homologous sequences. The number of amino acid residues omitted, which flank and separate the motifs, is indicated in brackets. Residues with related physical or chemical properties are shaded in black when present in all sequences and in gray if present in four out of six sequences.

Finally, none of the four TvMULEs encodes a mudrB product, similarly to what is observed in the A. thaliana and O. sativa [40,41,43]. Even in plants, while mudrA sequences are widespread in grasses, mudrB sequences seem to be restricted to Zea [46].

Preferential insertion sites of TvMULEs

Among all matches with similarity to TvMULE1 (61) and TvMULE2 (514), only 8% (five sequences) and 0.5% (three sequences), respectively, correspond to complete copies. Probably due to their longer size, which can not be spanned by two PCR reads, matches to TvMULE3 (666) and to TvMULE4 (1,204) represent only internal or end regions of the elements; these observations reflect the fragmentary nature of the current assembly, which in turn is caused by the highly repetitive character of the T. vaginalis genome. Thus, the analyses of putative insertion site preferences were performed with all insertions that contain at least one end region.

The sequences flanking TvMULE1 insertions exhibit a high degree of nucleotide conservation in the first 25 positions (data not shown). Genomic fragments of 2,000 or 5,000-nt adjacent to the element were extracted to evaluate the extent of such similarity in the regions flanking of different copies. The extent of the similarity between regions flanking TvMULE1 insertions depends on the copies of this family being compared. Interestingly, one pair of TvMULE1 copies (contig 85938:11024–17138 and contig 91860:9141–15539) appears to be nested within another repeat. In fact, the similarity upstream and downstream of these copies extends to 1,246-bp and to 3,075-bp, respectively, including putative 36-bp TIRs (5'-GgGtcaTTATtGATTTTGTAATTTAATCGTcgTCGT-3', and 5'-ACGAtaATGATTAAATTACAAAATCgATAAcctCtC-3'), suggesting an unknown repeat of approximately 4,300 bp in length. This unknown repeat is itself flanked by two different TSDs (Table 2). Despite the fact that this full-length nested configuration is observed only in the two genomic regions mentioned above, multiple partial copies of TvMULE1 that contain one end region are flanked by fragments of this unknown repeat. Sequence similarity searches of this novel repeat against consensus sequences of Trichomonas and Entamoeba genera stored in Repbase database, ~55 repeat families identified in the T. vaginalis genome [9] and Genbank showed no significant matches. Therefore this element remains unidentified. We hypothesize that a copy of this repeat containing an insertion of TvMULE1 has transposed in a recent past producing multiple nested copies. However, detailed empirical studies of excision/transposition/insertion by transfection in new lineages are required to corroborate this hypothesis.

Table 2.

Putative TSDs flanking TvMULEs and the unknown repeat

| Family | TSD | |

| Length (bp) | Sequence | |

| TvMULE2 | 10 | ATATATCGGC |

| TTTATCGCTGa | ||

| 11 | AATTGATGAAA | |

| CCTTAATTCAA | ||

| CCATTTTGATA | ||

| TAATTCTCCAT | ||

| TTTCCCTGAAA | ||

| TGGTTTTATGA | ||

| GAAACAATTAA | ||

| 12 | TTAAATTACTTC | |

| 14 | AATTAAAAAAATAT | |

| TvMULE3 | 11 | CTATTTAAAAG |

| TTTTTTGATAA | ||

| TTTAAGGTGTT | ||

| TvMULE4 | 12 | AAAAAATTTTGA |

| AATTTTTTCGAA | ||

| ATATATCTTTAA | ||

| ATTTTTGAAAAA | ||

| TATACATATATA | ||

| TTATTATTTTAA | ||

| TTTCTTTTTTAT | ||

| 13 | AAAAATTTTGAAA | |

| ATTTTTTCTGGAT | ||

| AGATTTTTGAAAA | ||

| CTTATTTTTTGAA | ||

| TTTCAAAATTTTT | ||

| Unknown | 8 | TAGATTTTb |

| 9 | ATCAAAAAGc | |

aDuplication upon the chosen canonical copy;

Duplication upon the insertion contained in the: bcontig 85938 and ccontig91860.

TvMULE2, TvMULE3 and TvMULE4 are flanked by completely variable regions upstream and downstream of all insertions (data not shown). Curiously, multiple TSDs with distinct lengths are observed, a characteristic not found in MULEs previously characterized (Table 2). Taken at face value this would suggest an extreme flexibility in their insertion sites.

Finally, as the genomic distribution of these repeats is putatively the product of only self-mobilization, we assessed the preferential insertion of these TvMULEs relative to local GC content calculated in the first 100, 2,000 and 5,000-nt. The average GC content within the nearest 100-nt is 26.9% (se = 0.0) for TvMULE2, 27.7% (se = 0.4) for TvMULE3 and 25.0% (se = 0.3) for TvMULE4. The average GC content in the 2,000-nt and 5,000-nt flanking regions is slightly higher, ranging between 31.3% and 31.8% ± 0.0 for TvMULE2, 30.9% and 31.6% ± 0.2% for TvMULE3, 30.0% and 30.7% ± 0.2% for TvMULE4, respectively. This nucleotide composition is similar to that of intergenic regions in the current assembly (28.8%) and considerably lower than the GC content of T. vaginalis genes (53.5%), suggesting either that these two TvMULE families insert preferentially in non-active regions or that insertions into genes have been eliminated by selection. This is not unexpected since almost all T. vaginalis genes are intronless and TE insertions within coding regions are frequently associated to deleterious effects [e.g., [55]].

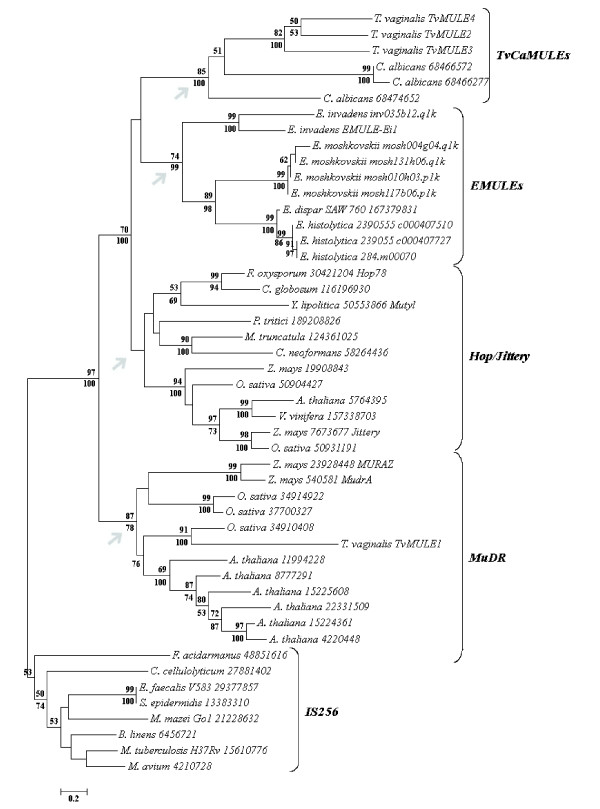

Phylogenetic relationship of TvMULEs

Three major clades of eukaryotic elements have been identified to date in the Mutator superfamily: (1) the MuDR group, characteristic of plant genomes, contains the original Mutator elements identified in maize, and its relatives from Arabidopsis and rice, (2) the Hop/Jittery group contains elements from a variety of host taxa including plants and fungi, and (3) the EMULE clade, which contains all elements identified in the genome of Entamoeba species. Members of these three clades were used to determine the phylogenetic placement of the T. vaginalis MULEs in the Mutator superfamily, and the tree was rooted with elements belonging to the IS256 clade of bacterial transposons. Bayesian analyses showed strong support for the monophyly of the eukaryotic Mutator sequences relative to the bacterial IS256 elements (Figure 4). The eukaryotic clade is present in 100% of the trees in the posterior sample, a result that is confirmed by neighbor-joining (NJ) analysis (97% bootstrap support). There is also strong support (87% in NJ bootstrap and 78% in bayesian analysis) for a clade containing the MuDR elements. The NJ analysis suggests the monophyly of the Hop/Jittery clade but the support from Bayesian and NJ bootstrap analyses is <50%. Finally, the EMULE sequences form a strongly supported monophyletic clade (74% in NJ bootstrap and 99% in bayesian analysis). The elements from T. vaginalis are nested within the broad clade of eukaryotic Mutator elements. TvMULE1 clusters with an element from O. sativa in the MuDR clade. On the other hand, TvMULE2, TvMULE3 and TvMULE4, together with the C. albicans sequences, form a monophyletic clade present in 100% of the trees in the posterior sample of the bayesian analysis and in 85% neighbor-joining bootstrap trees. All these findings lead us to conclude that the TvMULEs/C. albicans clade represents a new and quite distinct branch in the Mutator superfamily, which we name TvCaMULEs.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of Mutator superfamily proteins. The cladogram was generated by neighbor-joining, from an alignment of three conserved amino acid motifs present in all sequences (length = 123 residues), and which corresponds to pfam00872 (COG3328 and CDD85084). The sequences are identified by the host names, GenInfo Identifier (gi) and TE names, when previously characterized. Node support obtained from 1,000 bootstrap replicates using NJ and from their representation in the posterior sample of the bayesian analysis is shown above and below the branches, respectively. Gray arrows indicate the four main clades in the Mutator phylogeny.

The genetic distances within and between clades were calculated in order to determine the heterogeneity of the MULEs. First, the TvCaMULE members are more divergent regarding on the number of amino acid substitution per site (aa/site) among each other (aa/site= 1.84 ± 0.17) than the members of other clades (Hop/Jittery: aa/site= 1.53 ± 0.06; MuDR: aa/site= 1.45 ± 0.07; IS256: aa/site= 1.27 ± 0.08; and EMULEs: aa/site= 1.04 ± 0.09). However, this higher divergence is due to difference between the members of the two species (aa/site= 2.19 ± 0.07) than between C. albicans (aa/site= 1.43 ± 0.7) and the TvMULEs (aa/site= 1.2 ± 0.1) sequences. Second, a pairwise comparison between clades shows that TvCaMULEs are the most distinct from any other clade (aa/site= 2.96 ± 0.15) than all other comparison pairs (aa/site= 2.5 ± 0.06). These data lead us to conclude that TvCaMULEs form a heterogeneous group and that they are distantly related to the other MULEs analyzed.

Multiple conserved motifs in Mutator and IS256 superfamilies

Forty eight Mutator and IS256 transposon sequences were used to search for sequence motifs common within this superfamily. Twelve conserved motifs were identified, with motifs 1, 4 and 8 present in all sequences [see Additional file 2 and Table 3]. Interestingly, only the elements of the MuDR and Hop/Jittery clades present the D34E active site integrase signature between motifs 4 and 8, while the bacterial transposons show a range in the number of intervening residues in this region (D38-40E) [Table 3]. Some motifs are clade-specific, such as motifs 5 and 9 in the IS256 clade, which are similar to the Mutator-like transposase domain, while others are more widespread, such as motifs 7 and 10 harbored by plants and fungi in the MuDR and Hop/Jittery clades.

Table 3.

Characterization of 48 MULEs analyzed in this study

| Clades | Analyzed sequences | Conserved motifs | ||

| All clades | Dispersed | Clade-specific | ||

| IS256 | 8 | 1a, 4 and 8c | - | 5d and 9d |

| MuDR | 12 | 1a, 4 and 8b | 7e and 10f | - |

| Hop/Jittery | 12 | 1a, 4 and 8b | 7e and 10f | 11f |

| EMULEs | 10 | 1a, 4 and 8 | - | 2f, 3f and 6f |

| TvCaMULEs | 6 | 1a, 4 and 8 | 10f | 12f |

| TOTAL | 48 | 12 | ||

a 25-aa signature sequence described by Eisen et al. [19];

Active site residues found into motifs 4 and 8: bD34E and cD38-40E;

Motif similar to Mutator-like transposase domain corresponding to: d pfam00872 and e pfam03108;

f No match between motif and putative conserved domains have been detected.

Distribution and transcriptional activity of TvMULEs in Trichomonads

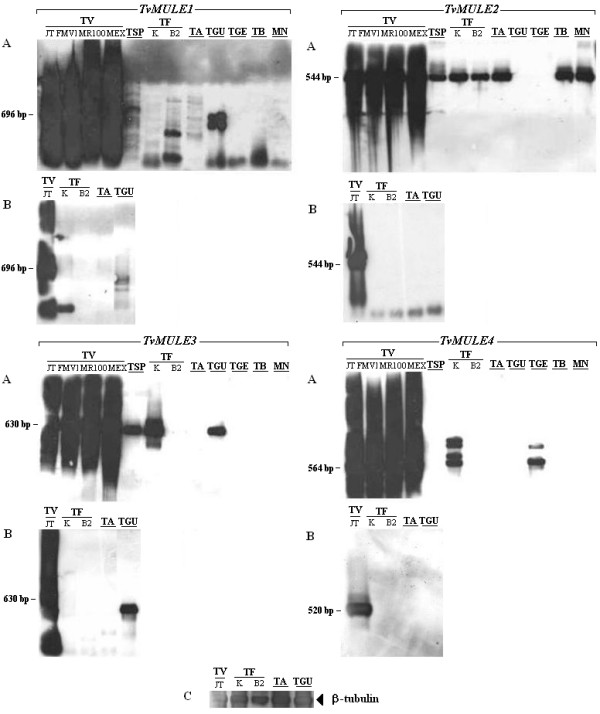

The low degree of sequence polymorphism within TvMULE families suggests a very recent expansion of Mutator-like transposons in the T. vaginalis genome, either due to TE-induced proliferation or to small-scale duplications of the host genome. To evaluate whether this expansion occurred before or after the global expansion of T. vaginalis, four T. vaginalis isolates obtained from different geographical regions were analyzed for the presence of TvMULE homologs (Table 4). PCR products from each sample were obtained using primer pairs from each canonical MULE family of T. vaginalis (Table 5). The specificity of these amplifications was confirmed by stringent DNA hybridizations using as probe an internal fragment of Tpase isolated of the T. vaginalis JT strain. The strong hybridization signal in all lanes suggests the presence of all TvMULEs in the four T. vaginalis strains tested (Figure 5A). Interestingly, homologs to the TvMULEs occur in other Trichomonad species, even though their distribution appears to be patchy. All non-T. vaginalis isolates showed extremely weak or nearly imperceptible PCR amplification (data not shown), possibly due to low copy number and/or high sequence divergence in the primer region. However, positive hybridization signals were still detected against these amplicons in some of these species (Figure 5A). In particular, Tetratrichomonas sp and T. gallinae, the two closest species to T. vaginalis examined, show evidence of TvMULE1, TvMULE2 and TvMULE3, and of TvMULE4, respectively. On the contrary, the species more distantly related to T. vaginalis [47] show a heterogeneous pattern. T. foetus, a parasite of the urogenital tract in cattle, shows hybridization to each of the four repeats in at least one of the strains sampled, and T. augusta, T. batrachorum, and Monocercomonas sp show evidence of only TvMULE2. The patchy distribution among species and strains suggest extensive divergence and/or loss of elements homologous to TvMULEs among Trichomonads.

Table 4.

Trichomonad species and strains used in this study

| Species | Isolates | Origin | Host | Hybridization | |

| DNA | cDNA | ||||

| Trichomonas vaginalis | JT | Rio de Janeiro/Brazil | Human | ✔ | ✔ |

| FMV1 | Minas Gerais/Brazil | Human | ✔ | ||

| MR100 | Czec Republic1 | Human | ✔ | ||

| Mex | Mexico | Human | ✔ | ||

| Tetratrichomonas sp | SP1 | Argentina | Pigeon | ✔ | |

| Tritrichomonas foetus | K | Rio de Janeiro/Brazil2 | Bovine | ✔ | ✔ |

| B2 | Argentina | Bovine | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Tritrichomonas augusta | 30082 | Czec Republic1 | Frog | ✔ | ✔ |

| Tetratrichomonas gallinarum | MR5 | Czec Republic1 | Chicken | ✔ | ✔ |

| Trichomonas gallinae | TG09 | Porto Alegre/Brazil | Pigeon | ✔ | |

| Trichomitus bathracorum | G43 | New York City/USA | Snake | ✔ | |

| Monocercomonas sp | - | Cuba | Snake | ✔ | |

✔ Samples used in each hybridization experiments;

Isolated by: 1 J. Kulda (Charles University in Prague); 2 H. Guida (Embrapa).

Table 5.

List of oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence | Positions (bp) |

Expected length (bp) |

| TvMULE1_F | 5'-AAGCGAGCATGAACTGCATCA | 229–249 | 696 |

| TvMULE1_R | 5'-TTCCGATCAAGGTCCGGCAATTA | 902–924 | |

| TvMULE2_F | 5'-GCTGACTGTGCGCTAAACATTGCT | 1055–1078 | 544 |

| TvMULE2_R | 5'-GCTCAACAATCTGATTACCTGCCC | 1575–1598 | |

| TvMULE3_F | 5'-GGGTATCAAAGAACAAGAGTCACC | 1,286–1,309 | 630 |

| TvMULE3_R | 5'-TCTCTTTCAGCGGCTGTCCATCTT | 1,892–1,915 | |

| TvMULE4_F | 5'-GGACAAACTCGCCCATTGTCACTT | 8–31 | 584 |

| TvMULE4_R | 5'-TCTTGACAGGTGGATGCTTCGCTA | 568–591 | |

| TvMULE4_2F | 5'-TTCGCCTTTCTGGGAAGTACTGGT | 485–508 | 520 |

| TvMULE4_2R | 3'-GTCACTGGCAAATTCGCGGAATCA | 981–1,004 | |

| β tubulin_F | 5'-ACACTCCTTCTCAACAAGCTCCGT | 692–715 | 673 |

| β tubulin_R | 5'-AGGCTGTTGTGTTGCCGATGAATG | 1341–1364 |

Figure 5.

Detection of TvMULEs in trichomonad species by DNA and cDNA hybridizations. A – Host distribution; B – Transcriptional activity; and C – Hybridization of beta-tubulin controls from each sample to control for RNA loading. TV: Trichomonas vaginalis (strains – JT, FMV1, MR100 and Mex); TSP: Tetratrichomonas sp; TF: Tritrichomonas foetus (strains – K and B2); TA: Tritrichomonas augusta; TGU: Tetratrichomonas gallinarum; TGE: Trichomonas gallinae; TB: Trichomitus batrachorum; MN: Monocercomonas sp. Numbers represent expected size of the amplified fragments.

To verify if the TvMULEs are transcriptionally active, polyA+ RNA was extracted and cDNAs synthesized from one strain from T. vaginalis (JT) and six non-T. vaginalis species and isolates (Table 4). Again, RT-PCR products were obtained for each sample using the primer pairs of each element and their homology to TvMULEs validated by hybridization using the sequence from the JT strain of T. vaginalis as probe. The presence of abundant mRNA for the four TvMULEs was observed in the JT strain (Figure 5B), confirming that the four Mutator elements are active transcriptionally in T. vaginalis. In contrast, the other species show no evidence of transcripts of the expected size (Figure 5B).

Discussion

Transposable elements are major players in the evolution of eukaryote genomes. T. vaginalis, whose two-thirds of the genome consists of repetitive sequences, is a fascinating species to study in this context, since several topics can be explored: the discovery of new TEs, their structure and origin, the dynamic of TEs among related species and geographical populations, and their comparison to those characterized in other fully sequenced genomes. Mutator elements are one of the most thoroughly studied plant TEs [21,37,38,40-42,44,46,56-62]. For nearly three decades after their initial discovery by Robertson [35] they were thought to be present exclusively in plants. The first homologous representatives were completely characterized in the early 2000's in fungi [22,23] and in the amoebozoa [24]. We have conducted a comprehensive study of four new members of the Mutator superfamily in a new taxonomic group, the Parabasalids, and in particular the class Trichomonada, and conclude that three of the elements found are representatives of a new branch in the evolutionary history of the Mutator superfamily.

This study shows that only TvMULE1 is a typical member of the Mutator superfamily, since it shows significant similarity to Mutator proteins with known transposase motifs and harbors some of the hallmarks of MULEs. Interestingly, TvMULE2, TvMULE3 and TvMULE4, in addition to the presence of a conserved Mutator-like transposase domain and a motif identical to the 25-aa signature sequence of the MULE transposase core, also display new and distinct conserved motifs. The presence of Mutator-like elements in Trichomonads is not unrealistic, as the evolutionary relatedness between the maize Mutator autonomous elements and the bacterial IS256 [21] shows this superfamily's ability to invade hosts across large evolutionary distances or to survive, by vertical transmission, across the spectrum of life. New MULE families have already been characterized in other early divergent eukaryotes, such as in the first genomes analyzed from the genus Entamoeba [24]. What is perhaps surprising is that it took over two decades for elements of the Mutator superfamily to be identified in eukaryotic taxa other than plants. Our Southern blot experiments using TvMULE probes strongly suggest their presence in other trichomonad species and our in silico analyses allowed their identification in the C. albicans genome.

Elements similar to our repeats TvMULE2, TvMULE3 and TvMULE4 have been submitted to Repbase Reports, namely MuDR-4_TV [63], MuDR-3_TV [64], MuDR-5_TV [65], respectively. These repeats and their structures differ somewhat from those found here described in one or more of the following characteristics: (1) length of the elements and the peptides they encode; (2) length of TSDs; and (3) copy number estimates. The differences could be due to the methods employed to determine the canonical consensus sequences.

The four TvMULEs each carry a putative transposase ORF, which are smaller than those of known MULE Tpases but seem, nevertheless, to be functional since independent lines of evidence support their transpositional activity. The level of sequence divergence between copies and their respective consensus sequences (identity >99%) and the presence of complete copies inserted in different scaffold locations suggest that these families have undergone a recent process of activation and amplification. In addition, the set of expressed mRNAs includes transcripts with high sequence similarity to these repeats. Interestingly, typical MULE TIRs, characteristically over 100 bp long and the perfect inverted complement of each other, and which are supposedly necessary for mobilization, were not identified in TvMULES. We hypothesize that these repeats represent of a novel type of non-TIR-MULEs, similar to those identified in A. thaliana, which are able to transpose in the absence of long TIRs [40].

The large number and mobility of TvMULEs, much like those observed for other TEs already characterized in T. vaginalis [9,50-52], raise puzzling questions. What are the biological and epidemiological features that explain such high level of recent transposon activity in T. vaginalis, while these elements present a heterogeneous distribution among other Trichomonads examined? Could these elements have been recently introduced into T. vaginalis and, if so, where from? How do these TEs contribute to the architecture and dynamics of this highly repetitive genome? What in the T. vaginalis genetic background makes this genome permissive to the high activity of these DNA transposons, to the extent that they have accumulated to hundreds and even thousands of copies per family [9]?

A fascinating hypothesis to explain the extraordinary expansion of TEs in the genome of T. vaginalis was proposed by Carlton and collaborators [9]. T. vaginalis, unlike most other Trichomonads which are enteric, is a parasite of the human urogenital tract. A large cell size is likely advantageous in this species, since it increases its phagocytosis ability, decreases the probability of it being ingested by other organisms and host macrophages, and facilitates adhesion to vaginal epithelial cells. There is a strong, and possibly causal, correlation between genome size and cell size [66-68]. Therefore, an initial stochastic expansion of TE families could have given rise to the variation upon which natural selection could act, favoring the largest cells and, concomitantly, those with the largest TE complement [9]. It is interesting to note that Tritrichomonas foetus, the only other vaginal trichomonad surveyed, was the only other species in which all four TvMULEs were detected.

The large copy number and extremely low polymorphism of TvMULEs and other T. vaginalis repeats, as well as their absence in T. tenax, a parasite of the bucal cavity and the sister taxon to T. vaginalis, suggest a fast repeat expansion that has taken place in a recent evolutionary past [9]. The lack of homologs of the T. vaginalis repeats in T. tenax [9] also raises the possibility that these elements have been recently acquired through horizontal transfer, a phenomenon that is relatively more common than was once believed, and which is possibly an essential step in the life-cycle of successful class II transposable elements [69,70]. Here we found evidence for the presence of some TvMULE homologs in some of the species surveyed. In particular, only TvMULE4 shows a strong hybridization signal in T. gallinae, the closest species to T. vaginalis examined in this study, while homologs to the other three TvMULE families are present in more distantly related species. The possibility remains that these repeats could have been lost from some species, or that the PCR primers used did not amplify existing divergent homologous repeats, an issue that can only be solved with an extensive genomic survey of the family Trichomonadidae.

Transposable elements have undeniably played a major role in the expansion of eukaryotic genomes, a phenomenon well documented in plants [71], arthropods [72] and vertebrates [73-76]. Rapid genome expansions due to bursts of TE amplification, similar to what is observed in T. vaginalis, have also been postulated for a variety of organisms [77-81]. What sets T. vaginalis apart is the fact that it is an asexual species, which, like all other trichomonads, reproduces by longitudinal binary fission. It has been argued that transposons are unable to persist in the long term in clonal lineages because the mechanisms that keep TE copy number in check in sexual species, and that thereby prevent excessive mutational loads, are absent in asexual lineages [82]. In addition, once lost, they cannot be reintroduced by sexually-mediated genetic transfer [83]. Given the recency of the TE expansion in T. vaginalis, their long-term effect on the survival of the species is as yet unclear. It is possible that, with each TE family expansion, this species is steadily proceeding to extinction.

Conclusion

The remarkably recent common ancestry of each TE family in the T. vaginalis genome is attested to by the high copy number and nearly complete within-family sequence similarity of these TvMULEs, features that are shared with the other ~55 repeat families identified in the T. vaginalis genome. The structure of each repeat, inferred from the consensus of all copies within a family, is therefore likely to reflect with high accuracy the ancestral sequence of each original active element. This makes the genome sequence of T. vaginalis is an ideal mining ground for new transposable elements, which sequence and structure have not yet been adulterated by the accumulation of inactivating mutations.

Methods

The consensus sequences of the newly characterized Mutator-like elements from Trichomonas vaginalis described here have been submitted to Repbase Reports http://www.girinst.org.

In silico analyses

The draft genome sequence of the G3 strain of T. vaginalis was obtained from the website of The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) http://www.tigr.org/tdb/e2k1/tvg/. This draft, based on ~7.2-fold coverage of the genome, consists of 17,290 scaffolds, representing ~160 Mbp [9]. Sequence similarity searches using the four consensus sequences of TvMULEs as query against the T. vaginalis genome were performed using BLASTN [84], with parameters E = e-20, V = 10,000 and B = 10,000. Significant matches were required to be >200 bp long and display ≥ 80% identity. We will refer to the repeat copies found in the genomes according to the contig scaffold name and the start and end position of the copy. The coordinates of each BLASTN match were extracted using our customized Perl scripts, which utilized some modules of the BioPerl toolkit [85], and aligned with ClustalW [86] with default parameters. When available, the regions flanking each insertion were extracted for additional analyses: i) logo sequences were built from the first 25 nt upstream and downstream of each insertion using WebLogo [87], ii) the extent of the similarity between insertions, in regions upstream of the 5' end and downstream of the 3' end, was evaluated by BLASTN, and iii) the "guanine and cytosine" content (percent GC) was calculated from the first 100, 2,000 and 5,000 flanking nucleotides using the program "geecee" of the EMBOSS package http://emboss.sourceforge.net.

As T. vaginalis genes are mostly intronless all open reading frames (ORFs) corresponding to protein coding genes start with a methionine (Met) residue. The location of all ORFs starting with a Met residue that were at least 100 amino acids in length was determined for all contigs that contained the four TvMULEs, using the program "getorf" of the EMBOSS package. Homologs to the most frequent ORFs associated with each TE were detected by BLASTP against the non-redundant protein database in GenBank. Conserved domains were predicted with the « Conserved domain search » toolbox from NCBI [88] or the MEME package [89]. The putative occurrence of conserved terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) was analyzed by BLAST 2 sequences [90] and manual inspection.

Phylogenetic Analyses

Additional sequences of Mutator elements and related TE families from a variety of taxa, including plants, fungi, protists and bacteria, were obtained from GenBank, Repbase Report, TIGR http://www.tigr.org/tdb/e2k1/eha1/ and the BLAST Server of the Sanger Institute http://www.sanger.ac.uk/cgi-bin/blast/submitblast/comp_Entamoeba. Highly conserved regions in 56 protein sequences of Mutator and IS256 were detected using MEME, with the following parameters: number of different motifs = 15; minimum and maximum motif width = 5 and 300 amino acids, respectively. Twelve motifs were identified, of which motif 1 is conserved in all sequences, motif 8 occurs with the second highest frequency followed by motif 4 [see Additional file 2]. These three motifs are contiguous in the following orientation: motif 4 → motif 8 → motif 1. The sequences with motifs 4 and 8 were used as reference for discovering homologous regions by manual inspection in proteins where they were not identified by MEME due to their higher sequence divergence. The three motifs were found in 48 of the initial 56 sequences. This region containing motifs 4, 8 and 1 was extracted and aligned by CLUSTALW [86] with default parameters; the alignment was refined manually [see Additional file 3]. Two methods were used to reconstruct the evolutionary relationships among the sequences: i) neighbor-joining (NJ) with the JTT substitution model, pairwise deletion condition and the bootstrap analysis consisted of 1,000 replicates as implemented in MEGA4 [91], and (ii) a bayesian analysis, implemented in MrBayes v3.1.2 [92]. Model settings for MrBayes were as follows: amino acid transition matrix was set to a mixture of models with fixed rate matrices (Poisson, Jones, Dayhoff, Mtrev, Mtmam, Wag, Rtrev, Cprev, Vt, and Blosum) of equal prior probabilities, site rate variation described by a gamma distribution (α uniformly distributed between 0–200, with 4 rate categories), and a proportion of invariant sites uniformly distributed between 0.0–1.0. Branch lengths were unconstrained and described by an exponential distribution (10.0). Two simultaneous runs of MrBayes, with 4 chains each, ran for 1,500,000 generations. Results were evaluated after a burn-in period of 10% (150,000 generations) and convergence was achieved (PSRF= 1.00) for all model parameters estimated, including tree length (mean = 18.8), α = 2.28 and the proportion of invariant sites (4%), the amino acid model (Blosum), and the tree topology (see results).

Trichomonad species and Culture medium

The trichomonad species used in this study are listed in Table 4. Cultures were maintained in TYM Diamond's medium [93] as suggested by the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and grown at 36.5°C until reaching 5 × 106cells. The samples were collected by low speed centrifugation and washed two times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2).

DNA amplification and sequencing

Amplification of each of the four TvMULEs was performed with primer sets designed to amplify an internal region of the transposase domain (Table 5). PCR was done in a volume of 25 μl with 0.5U of Taq DNA polymerase in 1× polymerase buffer, 10 μM of each primer, a 200 μM concentration of each dNTP and 1.5 mM MgCl2. The solutions were heated to 94°C for 2 min, and followed by 35 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 1 min), annealing (60°C for 2 min), and extension (72°C for 1 min), followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products with the expected size were excised from 1% agarose gels, purified using GFX™ PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK), and cloned using TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). To confirm the identity of the PCR products from the T. vaginalis JT isolate, both strands of two clones for each transposon, chosen at random, were sequenced using the BigDye Terminator mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and run on an ABI 377 sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The clones were used as probes to confirm DNA and cDNA PCR amplification of each TvMULE.

DNA and cDNA hybridization analyses

Genomic DNA was extracted from the eight trichomonad species listed in Table 4 using DNAzol® reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and PCRs run on each sample with TvMULE-specific primers. The occurrence of TvMULEs in different species was confirmed by Southern blot of PCR products using the detection system Gene Images CDP-Star detection module (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, UK), due to non-availability of total DNA content sufficient for direct DNA gel blot. Cloned TvMULE transposase fragments were labeled with the chemioluminescent hybridization system Gene Images random-prime labeling module (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, UK). PCR products were separated in 1% agarose gels and transferred to Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, UK). Blots were prehybridized 1 h at 60°C in 5× SSC, 5% dextran sulfate and 20-fold dilution of liquid block and hybridized overnight with the probes of each TvMULEs. Blots were washed twice with 0.2× SSC, 0.5% SDS and exposed to autoradiographic film for 20 minutes at room temperature.

In order to identify transcriptional activity, PolyA+ RNA was isolated from total RNA of each species listed in Table 4 using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). 5 μg polyA+ RNA was used for cDNA synthesis using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with random primers and Oligo d(T)12 (Gene Link™, Hawthorne, NY) at low stringency (37°C). RT-PCR products of each cDNA sample were electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels, and the fragments were transferred onto Hybond N+ membranes. Prehybridization, hybridization, washing and detection were performed as for DNA hybridization.

Abbreviations

TEs: Transposable elements; TIRs: Terminal inverted repeats; MULEs: Mutator-like elements; TSDs: Terminal site duplications; TvMULEs: Trichomonas vaginalis Mutator-like elements; Tpase: Transposase; NJ: neighbor-joining; ORFs: open reading frames.

Authors' contributions

FRL conceived the project and wrote the manuscript and was responsible for data collection, analyses and interpretation. JCS performed the bayesian analysis, participated in data interpretation and writing. MB provided DNA samples of trichomonad species and strains as well as laboratory facilities for the organism culture and mRNA extraction. GGLC and GAGP provided the PERL scripts and final style of the figures 1, 2, 3, and performed BLAST runs. CMAC coordinated the project, participated in data interpretation and the manuscript elaboration. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Conserved motif in the transposases of elements from the Mutator-IS256 superfamily. A – Multiple alignment of motif 1 with 36-aa. B – Sequence logo. The vertical axis has a maximum value of 4 and is proportional to the level of sequence conservation at each position. Identical residues or those sharing similar physical or chemical properties are shown in black if present in all sequences, and in gray if present in the majority of the sequences. Each sequence name contains the species or TE (if previously assigned) name, the gi accession number and the coordinates of residues included in the alignment.

Summary of 12 motifs identified by MEME in 56 proteins of Transposase from Mutator and IS256 superfamily. The protein length is shown in the bar scale, except those for which the length is annotated on the right.

Clustal alignment of the domain found in the transposases from the Mutator – IS256 superfamily. Five main clades and the region of the three conserved motifs are shown.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank F. Reinol (USU, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) for technical support and two anonymous reviewers for many helpful comments. Funding for this project was provided by the Brazilian agency CNPq (to C.M.A.C, M.B and G.A.G.P).

Contributor Information

Fabrício R Lopes, Email: fabricio@ibilce.unesp.br.

Joana C Silva, Email: jcsilva@som.umaryland.edu.

Marlene Benchimol, Email: marlenebenchimol@gmail.com.

Gustavo GL Costa, Email: glacerda@lge.ibi.unicamp.br.

Gonçalo AG Pereira, Email: goncalo@unicamp.br.

Claudia MA Carareto, Email: carareto@ibilce.unesp.br.

References

- Kidwell MG. Transposable elements and the evolution of genome size in eukaryotes. Genetica. 2002;115:49–63. doi: 10.1023/A:1016072014259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro JA, von Sternberg R. Why repetitive DNA is essential to genome function. Biol Rev. 2005;80:227–250. doi: 10.1017/S1464793104006657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell MG, Lish D. Transposable elements as sources of variation in animals and plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7704–7711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan IK, Rogozin IB, Glazko GV, Koonin EV. Origin of a substantial fraction of human regulatory sequences from transposable elements. Trends Genet. 2003;19:68–72. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagemaat LN van de, Landry JR, Mager DL, Medstrand P. Transposable elements in mammals promote regulatory variation and diversification of genes with specialized functions. Trends Genet. 2003;19:530–536. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornburg BG, Gotea V, Makalowski W. Transposable elements as source of transcription regulation signals. Gene. 2006;365:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedoroff N. Transposon and genome evolution in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7002–7007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen JL. Mechanisms and rates of genome expansion and contraction in flowering plants. Genetica. 2002;115:29–36. doi: 10.1023/A:1016015913350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton JM, Hirt RP, Silva JC, Delcher AL, Schatz M, Zhao Q, Wortman JR, Bidwell SL, Alsmark UCM, Besteiro S, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Noel CJ, Dacks JB, Foster PG, Simillion C, van de Peer Y, Miranda-Saavedra D, Barton GJ, Westrop GD, Müller S, Dessi D, Fiori PL, Ren Q, Paulsen I, Zhang H, Bastida-Corcuera FD, Simoes-Barbosa A, Brown MT, Hayes RD, Mukherjee M, Okumura CY, Schneider R, Smith AJ, Vanacova S, Villalvazo M, Haas BJ, Pertea M, Feldblyum TV, Utterback TR, Shu CL, Osoegawa K, Jong PJ, Hrdy I, Horvathova L, Zubacova Z, Dolezal P, Malik SB, Logsdon JM, Jr, Henze K, Gupta A, Wang CC, Dunne RL, Upcroft JA, Upcroft P, White O, Salzberg SL, Tang P, Chiu CH, Lee YS, Embley TM, Coombs GH, Mottram JC, Tachezy J, Fraser-Liggett CM, Johnson PJ. Draft genome sequence of the sexually transmitted pathogen Trichomonas vaginalis. Science. 2007;315:207–212. doi: 10.1126/science.1132894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N, Bao Z, Zhang X, Eddy SR, Wessler SR. Pack-MULE transposable elements mediate gene evolution in plants. Nature. 2004;431:569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature02953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov VV, Jurka J. Helitrons on a roll: eukaryotic rolling-circle transposons. Trends Genet. 2007;23:521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosius J, Gould SJ. On 'genomenclature': a comprehensive (and respectful) taxonomy for pseudogenes and other 'junk DNA'. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10706–10710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber A, O'Connell MA, Keller W. Two forms of human double-stranded RNA-specific editase 1 (hRED1) generated by the insertion of an Alu cassette. RNA. 1997;3:453–463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WJ, McDonald JF, Nouaud D, Anxolabéhère D. Molecular domestication – more than a sporadic episode in evolution. Genetica. 1999;107:197–207. doi: 10.1023/A:1004070603792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekrutenko A, Li WH. Transposable elements are found in a large number of human protein-coding genes. Trends Genet. 2001;17:619–621. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(01)02445-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgard P, Huang TM, Wolkoff AW, Stockert RJ. Translated Alu sequence determines nuclear localization of a novel catalytic subunit of casein kinase 2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283:C472–C483. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00070.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoenicka J, Arrasate M, de Yebenes JG, Avila J. A two-hybrid screening of human Tau protein: interactions with Alu-derived domain. Neuroreport. 2002;13:343–349. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200203040-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volff JN. Turning junk into gold: domestication of transposable elements and the creation of new genes in eukaryotes. BioEssays. 2006;28:913–922. doi: 10.1002/bies.20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotea V, Makalowski W. Do transposable elements really contribute to proteomes? Trends Genet. 2006;22:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes FR, Carazzolle MF, Pereira GAG, Colombo CA, Carareto CMA. Transposable elements in Coffea (Gentianales: Rubiacea) transcripts and their role in the origin of protein diversity in flowering plants. Mol Genet Genomics. 2008;279:385–401. doi: 10.1007/s00438-008-0319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen JA, Benito MI, Walbot V. Sequence of putative transposases links the maize Mutator autonomous elements and a group of bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2634–2636. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.13.2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalvet F, Grimaldi C, Kaper F, Langin T, Daboussi MJ. Hop, an active Mutator-like element in the genome of the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:1362–1375. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuvéglise C, Chalvet F, Wincker P, Gaillardin C, Casaregola S. Mutator-like element in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica displays multiple alternative splicing. Eukar Cell. 2005;4:615–624. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.3.615-624.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritham EJ, Feschotte C, Wessler SR. Unexpected diversity and differential success of DNA transposon in four species of Entamoeba protozoans. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1751–1763. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov VV, Jurka J. CEMUDR1 is an autonomous DNA transposon – a consensus. Repbase Update. 2000.

- Kapitonov VV, Jurka J. CEMUDR2 is an autonomous DNA transposon – a consensus. Repbase Update. 2000.

- Kapitonov VV, Jurka J. MuDR1_TP, a family of MuDR DNA transposons from diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana. Repbase Reports. 2003;3:156. [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov VV, Jurka J. MuDR2_TP, a family of MuDR DNA transposons from diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana. Repbase Reports. 2003;3:157. [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov VV, Jurka J. MuDR-1_NV – a family of autonomous DNA transposons from the starlet sea anemone genome. Repbase Reports. 2007;7:622. [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov VV, Jurka J. MuDR-2_NV – a family of autonomous DNA transposons from the starlet sea anemone genome. Repbase Reports. 2007;7:623. [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J. MuDR-type element from Schmidtea mediterranea. Repbase Reports. 2007;7:1091. [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J. MuDR-type element from Schmidtea mediterranea. Repbase Reports. 2007;7:1090. [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J, Bao W. Highly diverged MuDR-type families. Repbase Reports. 2008;8:237. [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J, Bao W. Highly diverged MuDR-type families. Repbase Reports. 2008;8:415. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson DS. Characterization of a Mutator system in maize. Mutat Res. 1978;51:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lisch D. Mutator transposons. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:498–504. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisch D, Girard M, Donlin L, Freeling M. Functional analysis of deletion derivates of the maize transposon MuDR delineates roles for the MURA and MURB protein. Genetics. 1999;151:331–341. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.1.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizada MN, Walbot V. The late developmental pattern of Mu transposon excision is conferred by a cauliflower mosaic virus 35S-driven MURA cDNA in transgenic maize. Plant Cell. 2000;12:5–21. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le QH, Wright S, Yu Z, Bureau T. Transposon diversity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7376–7381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z, Wright SI, Bureau TE. Mutator-like elements in Arabidopsis thaliana: structure, diversity and evolution. Genetics. 2000;156:2019–2031. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.4.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer T, Yordan C, Martienssen RA. Robertson's Mutator transposon in A. thaliana are regulated by the chromatin-remodeling gene Decrease in DNA Methylation (DDM1) Genes Dev. 2001;15:591–602. doi: 10.1101/gad.193701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L, Wood TC, Yu Y, Budiman MA, Tomkins J, Woo S, Sasinonowski M, Presting G, Frish D, Goff S, Dean RA, Wing RA. Rice transposable elements: a survey of 73,000 sequence-tagged-connectors. Genome Res. 2000;10:982–990. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte K, Srinivasan S, Bureau T. Survey of transposable elements from rice genomic sequences. Plant J. 2001;25:169–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M, Araujo PG, de Jesus EM, Varani AM, Van Sluys MA. Comparative analyses of Mutator-like transposases in sugarcane. Mol Genet Genomics. 2004;272:194–203. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-1036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccaro NL, Van Sluys MA, Varani AM, Rossi M. MudrA-like sequences from rice and sugarcane cluster as two bona fide transposon clades and two domesticated transposases. Gene. 2007;392:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisch D, Freeling M, Langham RJ, Choy MY. Mutator transposases is widespread in the grasses. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:1293–1303. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.3.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleina P, Bettim-Bandinelli J, Bonatto SL, Benchimol M, Bogo MR. Molecular phylogeny of Trichomonadidae family inferred from ITS-1, 5.8S rRNA and ITS-2 sequences. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:963–970. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanacova S, Liston DR, Tachezy J, Johnson PJ. Molecular biology of the amitochondriates parasites, Giardia intestinalis, Entamoeba hystolitica and Trichomonas vaginalis. Int J Parasitol. 2003;33:235–255. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling PJ, Palmer JD. Parabasalian flagellates are ancient eukaryotes. Nature. 2000;405:635–637. doi: 10.1038/35015167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva JC, Batisda F, Bidwell SL, Johnson PJ, Carlton JM. A potentially functional Mariner transposable element in the protist Trichomonas vaginalis. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:126–134. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov VV, Jurka J. Self-synthesizing DNA transposons in eukaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4540–4545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600833103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritham EJ, Putliwala T, Feschotte C. Mavericks, a novel class of giant transposable elements widespread in eukaryotes and related to DNA viruses. Gene. 2007;390:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandbastien MA, Spielmann A, Caboche M. Tnt1, a mobile retroviral-like transposable element of tobacco isolated by plant cell genetics. Nature. 1989;337:376–380. doi: 10.1038/337376a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan IK, McDonald JF. Tempo and mode of Ty element evolution in Sacharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1999;151:1341–1351. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deininger PL, Batzer MA. Alu repeats and disease human. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;67:183–193. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomet P, Lisch D, Hardeman KJ, Chandler VL, Freeling M. Identification of a regulatory transposon that controls the Mutator transposable element system in maize. Genetics. 1991;129:261–270. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.1.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger RJ, Warren CA, Walbot V. Mutator activity in maize correlates with the presence and expression of the Mu transposable element Mu9. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10198–10202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger RJ, Benito MI, Hardeman KJ, Warren C, Chandler VL, Walbot V. Characterization of the major transcripts encoded by the regulatory MuDR transposable element of maize. Genetics. 1995;140:1087–1098. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.3.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisch D, Chomet P, Freeling M. Genetic characterization of the Mutator system in maize: behavior and regulation of Mu transposons in a minimal line. Genetics. 1995;139:1777–1796. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.4.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donlin MJ, Lisch D, Freeling M. Tissue-specific accumulation of MURB, a protein encoded by MuDR, the autonomous regulator of the Mutator transposable element family. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1989–2000. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.12.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito MI, Walbot V. Characterization of the maize Mutator transposable element MURA transposase as a DNA-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5165–5175. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizada MN, Benito MI, Walbot V. The MuDR transposon terminal inverted repeat contains a complex plant promoter directing distinct somatic and germinal programs. Plant J. 2001;25:79–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov VV, Jurka J. MuDR DNA transposons from protozoans. Repbase Reports. 2008;8:1814. [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov VV, Jurka J. MuDR DNA transposons from protozoans. Repbase Reports. 2008;8:1813. [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov VV, Jurka J. MuDR DNA transposons from protozoans. Repbase Reports. 2008;8:1815. [Google Scholar]

- Commoner B. Roles of deoxyribonucleic acid in inheritance. Nature. 1964;202:960–968. doi: 10.1038/202960a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MD. The duration of meiosis. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1971;178:277–299. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1971.0066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory TR. Coincidence, coevolution, or causation? DNA content, cell size, ADN the C-value enigma. Biol Rev. 2001;76:65–101. doi: 10.1017/S1464793100005595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva JC, Loreto EL, Clark JB. Factors that affect horizontal transfer of transposable elements. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2004;6:57–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreto EL, Carareto CM, Capy P. Revisiting horizontal transfer of transposable elements in Drosophila. Heredity. 2008;100:545–554. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6801094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel P, Gaut BS, Tikhonov A, Nakajima Y, Bennetzen JL. The paleontology of intergene retrotransposons of maize. Nature Genet. 1998;20:43–45. doi: 10.1038/1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira C, Nardon C, Arpin C, Lepetit D, Biémont C. Evolution of genome size in Drosophila. Is the invader's genome being invaded by transposable elements? Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:1154–1161. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerardinis RJ, Goodier JL, Ostertag EM, Kazazian HH. Rapid amplification of a retrotransposon subfamily is evolving the mouse genome. Nature Genet. 1998;20:288–290. doi: 10.1038/3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheen F, Sherry ST, Risch GM, Robichaux M, Nasidze I, Stoneking M, Batzer MA, Swergold GD. Reading between the LINEs: Human genomic variation induced by LINE-1 retrotransposition. Genome Res. 2000;10:1496–1508. doi: 10.1101/gr.149400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer KA, Chen X, Hinds DA, Krishna Pant PV, Patil N, Cox DR. Genomic DNA insertions and deletions occur frequently between humans and nonhuman primates. Genome Res. 2003;13:341–346. doi: 10.1101/gr.554603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke DP, Segraves R, Carbone L, Archidiacono N, Albertson DG, Pinkel D, Eichler EE. Large-scale variation among human and great ape genomes determined by array comparative genomic hybridization. Genome Res. 2003;13:347–357. doi: 10.1101/gr.1003303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira C, Lepetit D, Dumont S, Biémont C. Wake up of transposable elements following Drosophila simulans worldwide colonization. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:1251–1255. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biémont C, Vieira C, Borie N, Lepetit D. Transposable elements and genome evolution: the case of D. simulans. Genetica. 2000;107:113–120. doi: 10.1023/A:1003937603230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biémont C, Nardon C, Deceliere G, Lepetit D, Vieira C. Invasion of natural populations by transposable elements in Drosophila simulans. Evolution. 2003;57:159–167. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costas J. Molecular characterization of the recent intragenomic spread of the murine endogenous retrovirus MuERV-L. J Mol Evol. 2003;56:181–186. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2392-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer J, Meese E. Human endogenous retroviruses in the primate lineage and their influence on host genome. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110:448–456. doi: 10.1159/000084977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuzhdin SV, Petrov DA. Transposable elements in clonal lineages: lethal hangover from sex. Biol J Linn Soc. 2003;79:33–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1095-8312.2003.00188.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capy P, Bazin C, Higuet D, Langin T. Dynamics and Evolution of Transposable elements. France: Landes Biosciences; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stajich JE, Block D, Boulez K, Brenner SE, Chervitz SA, Dagdigian C, Fuellen G, Gilbert JG, Korf I, Lapp H, Lehvslaiho H, Matsalla C, Mungall CJ, Osborne BI, Pocock MR, Schattner P, Senger M, Stein LD, Stupka E, Wilkinson MD, Birney E. The Bioperl toolkit: Perl modules for the life sciences. Genome Res. 2002;12:1611–1618. doi: 10.1101/gr.361602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTALW: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hao L, He S, Hurwitz DI, Jackson JD, Ke Z, Krylov D, Lanczycki C, Liebert CA, Liu C, Lu F, Marchler GH, Mullokandov M, Song JS, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, Yin JJ, Zhang D, Bryant SH. CDD: a conserved domain database for interactive domain family analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D237–D240. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, Williams N, Misleh C, Li WW. MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:369–373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusova TA, Madden TL. Blast 2 sequences – a new tool for comparing protein and nucleotide sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:247–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LS. The establishment of various Trichomonads of animals and man in axenic cultures. J Parasitol. 1957;43:488–490. doi: 10.2307/3274682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Conserved motif in the transposases of elements from the Mutator-IS256 superfamily. A – Multiple alignment of motif 1 with 36-aa. B – Sequence logo. The vertical axis has a maximum value of 4 and is proportional to the level of sequence conservation at each position. Identical residues or those sharing similar physical or chemical properties are shown in black if present in all sequences, and in gray if present in the majority of the sequences. Each sequence name contains the species or TE (if previously assigned) name, the gi accession number and the coordinates of residues included in the alignment.

Summary of 12 motifs identified by MEME in 56 proteins of Transposase from Mutator and IS256 superfamily. The protein length is shown in the bar scale, except those for which the length is annotated on the right.

Clustal alignment of the domain found in the transposases from the Mutator – IS256 superfamily. Five main clades and the region of the three conserved motifs are shown.