Abstract

The gammaproteobacterium Xenorhabdus nematophila engages in a mutualistic association with an entomopathogenic nematode and also functions as a pathogen toward different insect hosts. We studied the role of the growth-phase-regulated outer membrane protein OpnS in host interactions. OpnS was shown to be a 16-stranded β-barrel porin. opnS was expressed during growth in insect hemolymph and expression was elevated as the cell density increased. When wild-type and opnS deletion strains were coinjected into insects, the wild-type strain was predominantly recovered from the insect cadaver. Similarly, an opnS-complemented strain outcompeted the ΔopnS strain. Coinjection of the wild-type and ΔopnS strains together with uncolonized nematodes into insects resulted in nematode progeny that were almost exclusively colonized with the wild-type strain. Likewise, nematode progeny recovered after coinjection of a mixture of nematodes carrying either the wild-type or ΔopnS strain were colonized by the wild-type strain. In addition, the ΔopnS strain displayed a competitive growth defect when grown together with the wild-type strain in insect hemolymph but not in defined culture medium. The ΔopnS strain displayed increased sensitivity to antimicrobial compounds, suggesting that deletion of OpnS affected the integrity of the outer membrane. These findings show that the OpnS porin confers a competitive advantage for the growth and/or the survival of X. nematophila in the insect host and provides a new model for studying the biological relevance of differential regulation of porins in a natural host environment.

The bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophila forms a mutualistic association with the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema carpocapsae (2). The nonfeeding infective juvenile form of the nematode (IJ) exists in the soil and carries the bacteria in a specialized receptacle region in the anterior intestine (4, 39). The IJ invades susceptible insect species and enters the hemocoel, where exposure to insect hemolymph stimulates the movement of bacteria down the intestine and out of the anus (36, 39). Together, the nematode and bacteria kill the insect host. X. nematophila not only helps to kill the insect but also promotes bioconversion of host macromolecules and tissues to provide nutrients for nematode reproduction and secretes diverse antimicrobial products to suppress competition for the nutrient resources of the insect cadaver (11, 13, 18, 19, 38). In turn, the nematode vectors X. nematophila to new insect hosts and protects it from the competitive environment of the soil. Colonization of the nematode receptacle is predominantly a monoculture process that is initiated by a single cell followed by bacterial proliferation (24, 39). The level of colonization varies from a few cells to several hundreds per nematode and is higher in nematodes reproducing in insects than on bacterial lawns, suggesting that the insect environment provides additional nutrients for bacterial growth (16, 39).

Hydrophilic nutrients and antibiotics passively diffuse across the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria through general porins and substrate-specific channels (17, 29). The most extensively studied general porins, OmpF and OmpC of Escherichia coli (30), are 16-stranded β-barrel proteins that are reciprocally regulated by changes in external osmolarity (12, 21, 41). Although the flow rate through OmpF is greater than OmpC (28), comparison of the resolved crystal structures does not reveal significant physiochemical differences between the two porins (3). The biological significance of the differential regulation of porins with distinct functional properties remains unclear. The major outer membrane protein of X. nematophila, OpnP, was shown to be produced at high levels in exponentially growing cells and is a homologue of OmpF and OmpC (14). OpnP production was not affected by changes in medium osmolarity, and the flow rate measured for the OpnP porin was more similar to the restrictive porin OmpC than to the more permissive OmpF porin (3). As cells transitioned to stationary phase, de novo synthesis of OpnP decreased, while the synthesis of the outer membrane protein, designated OpnS, increased (15, 22).

Porin function and regulation have been studied in both pathogenic and symbiotic bacteria. In Vibrio cholerae two well-studied porins, OmpU and OmpT, that possess distinct functional properties have been shown to be differentially regulated (37). OmpU confers resistance to sodium deoxycholate (DC), a major component of bile, as well as polymixin B, detergents, and antimicrobial peptides, while the expression of OmpT alone sensitizes the cell to DC (26, 33). OmpU was thought to be expressed when V. cholerae colonizes the intestine, suggesting that it was required for host colonization (33); however, subsequent findings indicated that neither OmpU nor OmpT were essential for intestinal colonization (34). Recent findings indicated that OmpU may sense membrane perturbations and activate DegS which in turn modulates σE activity (25, 26). In the symbiotic bacterium Vibrio fischeri the deletion of ompU was shown to reduce the efficiency of colonization of the light organ of the Euprymna scolopes squid and increase sensitivity to bile, antimicrobial peptides, and detergent (1). Interestingly, the ompU strain did not display a competitive defect for colonization in the presence of the wild-type strain.

In the present study the growth-phase-regulated outer membrane protein OpnS of X. nematophila was identified as a general porin that conferred a competitive advantage for growth in the insect host. OpnP and OpnS were the only general porins identified in the genome of X. nematophila. The reciprocal expression of OpnP and OpnS suggest that they serve distinct biological roles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Strains and plasmids used in the present study are listed in Table 1. X. nematophila strains were derived from ATCC 19061. Strains were grown at 30°C in either Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (10 g of Bacto tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 5 g of NaCl, and 1.2 ml of 0.81 M MgSO4 per liter) and Grace's cell culture medium (Gibco). E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in LB broth. Media were solidified by using 1.5% agar. Antibiotics were added to the media when appropriate in the following concentrations: ampicillin at 25 μg/ml for X. nematophila and at 50 μg/ml for E. coli, chloramphenicol at 12.5 μg/ml for X. nematophila and at 25 μg/ml for E. coli, and gentamicin at 10 μg/ml for both X. nematophila and E. coli.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| 19061 ATCC | Wild type, phase I variant Ampr | Laboratory stock |

| ΔopnS | ΔopnS::Cmr | This study |

| opnS+ | ΔopnS::Tn7/opnS::Gmr | This study |

| 19061/Tn7 | Wild type::Tn7/Gmr | This study |

| ΔopnS/TTn7 | ΔopnS::Tn7/Gmr | This study |

| S17-λpir | recA thi pro hsdR−M+; RP4-2Tc::Mu Km::Tn7 in the chromosome | Laboratory stock |

| β2155 | λpir host used for mating with X. nematophila; thrB1004 pro thi strA hsdS lacZΔM15 (F9 lacZΔM15 lacIqtraD36 proA1 proB1) ΔdapA::erm (Ermr) pir::RP4 [::kan (Kmr) from SM10] | 9 |

| S17-λpir/pER2 | Host strain carrying suicide vector pER2 | D. Saffarini |

| S17-λpir/pER2-ΔopnS::Cmr | Host strain carrying suicide vector pER2-ΔopnS::Cmr | This study |

| β2155/pUC18mini-Tn7T | Tn7 transposon vector | This study |

| HB101 | E. coli strain carrying helper plasmid pRK2013 | M. McBride |

| DH5a-λpir/pTNS2 | E. coli strain carrying helper plasmid pTNS2 | |

| β2155-Tn7T | β2155 carrying pUC18 miniTn7T transposon vector | This study |

| β2155-Tn7T opnS | β2155 carrying pUC18 miniTn7T opnS plasmid for complementation of ΔopnS | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSTblue-1 | Cloning vector; Ampr Kmr | Novagen |

| pER2 | Suicide vector; Gmr, R6K ori | D. Saffarini |

| pSTblue-1ΔopnS::Cmr | Cloning vector containing opnS::Cmr fragment | This study |

| pER2ΔopnS::Cmr | Plasmid pER carrying opnS::Cmr fragment for construction of ΔopnS strain in X. nematophila | This study |

| pUC18mini-Tn7T | Tn7 vector | 6 |

| puC18mini-Tn7T-opnS | Tn7 vector carrying the opnS gene | This study |

| pTNS2 | Helper plasmid for integration into the att site | 6 |

| pRK2013 | Helper plasmid for mating | M. McBride |

Abbreviations; Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance.

Identification of outer membrane proteins OpnC, OpnT, and OpnS.

Outer membrane proteins extracts were obtained from X. nematophila cells grown to stationary phase in LB medium by using 0.5% Sarkosyl as previously described (22). Extracts were resuspended in Laemmli buffer and resolved on an 8 M urea sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel. Resolved proteins were electrotransferred onto Immobilon-P (Millipore, Bedford, MA) by using a Bio-Rad TransBlot cell for 9 h at 90 mA at 4°C. Bands were visualized by using Coomassie blue stain. N-terminal amino acid sequencing was performed at the protein/nucleic acid shared facility at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Complete gene sequences were obtained by BLASTP analysis using XenorhabdusScope (http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/agc/mage/).

Extraction of outer membrane proteins from X. nematophila grown in hemolymph.

Wild-type strain was grown in LB medium with selection at 30°C for 18 h. The strains were pelleted, washed, and resuspended in Grace's medium. Then, 50 μl of cells was pelleted and resuspended in 500 μl of hemolymph treated with 40 μl of 5 mg of glutathione/ml. Cells were grown at 30°C with shaking for 24 h. Outer membrane proteins were extracted as previously described.

RT-PCR analysis.

Wild-type strain was grown in LB with selection at 30°C for 18 h. The strains were pelleted, washed, and resuspended in Grace's medium. Then, 50 μl of cells was pelleted and resuspended in 250 μl of hemolymph treated with 20 μl of 5 mg of glutathione/ml. Cells were grown at 30°C with shaking, and cell pellets were obtained at 7 and 22 h. As a control, the wild-type strain was grown in LB medium at 30°C, and cell pellets were obtained at 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 h. RNA was extracted by using TRIzol reagent as described by the manufacturer (Invitrogen) and quantified by measuring the optical density at 260 nm (OD260), and 300 ng of RNA was used for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis (AccessQuick RT-PCR; Promega). cDNA synthesis was conducted at 52°C for 45 min. The PCR was carried out for 20 cycles using the conditions 30 s at 94°C for denaturation, 30 s at 53°C for annealing, and 1 min at 72°C for extension. recA and 16S rRNA was used as internal controls. The primers used in the present study are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Rec-C F | GGGGGCATGCCCGAGATCAACGCCTATACG | Mutant construction |

| Rec-C R | GGGGCTCGAGGCAAGTGTGATTTCGTTGAACTG | Mutant construction |

| TetR F | GGGGCTCGAGATTGCTATCGCGTTGTGTTTTATC | Mutant construction |

| TetR R | GGGGGAGCTCCAATCCCATGTTCCAGCAATTTG | Mutant construction |

| Cmr F | GGGGCTCGAGCGTGTCCGAATAAATACCTGTG | Mutant construction |

| Cmr R | GGGGCTCGAGCGCGTGTCCGAATTTCTG | Mutant construction |

| S comp F | GGGGCTGCAGACTTGTTAATATTTGTACCGCATTGG | Complementation |

| S comp R | GGGGAAGCTTGATAATCACTGACGAACTGCCTAC | Complementation |

| opnS F | ATGGCAAGGCAGATGTTCAG | RT-PCR analysis |

| opnS R | ACAGACATCAGCCATGCTTC | RT-PCR analysis |

| recA F | GCGCTGAAATTCTATGCGTCTGTC | RT-PCR analysis |

| recA R | GCAGTTTCTGGATGCTCTTTCAGG | RT-PCR analysis |

Restriction sites are denoted by the underlined sequences.

Construction of the ΔopnS strain.

Primers engineered with restriction sites were used to PCR amplify (Phusion; NEB) chromosomal fragments upstream and downstream of the opnS gene. Similarly, a PCR fragment containing chloramphenicol-resistant cassette was amplified by using compatible restriction sites. All three fragments were digested and ligated into the SphI and SacI sites of vector pSTblue-1. The ΔopnS::Cmr fragment was screened by PCR and using SacI and SphI sites cloned into the suicide vector pER2. The construct was conjugated from E. coli S17 (λpir) into X. nematophila ATCC 19061. The first step of allelic exchange was selection of plasmid integration into the recipient chromosome by plating cells on gentamicin-ampicillin-LB plates. The resulting colonies were patched onto LB plates containing 5% sucrose without NaCl. The plates were incubated at 30°C overnight. Sucrose-resistant colonies were patched onto chloramphenicol LB plates. The resulting chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were subsequently patched onto gentamicin-containing LB plates, followed by incubation at 30°C overnight. The second recombination event was identified by colonies exhibiting chloramphenicol resistance and sensitivity toward gentamicin. Allelic replacement was confirmed by PCR amplification.

Construction of Tn7 complementation strain.

The opnS gene and 545-bp upstream fragment was PCR amplified (Phusion; NEB) using primers engineered with restriction sites and cloned into the PstI and HindIII sites of pUC18miniT-Tn7T-Gm (6). This construct was transferred into the ΔopnS strain by four parental mating, involving E. coli β2155/pUC18miniT-Tn7T-Gm-opnS, β2155/pTNS2, and HB101/pRK2013 (9). Insertion of the Tn7 construct into the att:Tn7 site of the X. nematophila chromosome was confirmed by PCR using specific primers.

Phenotypic characterization of strains.

Phenotypic plate analyses were performed for lipase activity (Tween 20, 40, and 60), protease activity, hemolytic activity (sheep red blood cells; Remel Co.), binding of bromothymol blue, swarming activity, and antibiotic activity against Micrococcus luteus as previously described (32). Briefly, strains were grown for 18 h, normalized by determining the OD600, and 6-μl aliquots were spotted onto the respective plates. The plates were incubated overnight at 30°C and assayed for activity. To assess the antibiotic activity, spotted plates were exposed to chloroform for 15 min and air dried for 15 min, followed by the overlay of 10 ml of soft agar (0.7% agar) inoculated with 200 μl of M. luteus. The diameters of the zones of clearing were compared and recorded. Nematode reproduction and recovery were performed as previously described (40) using Manduca sexta larvae (tobacco horn worm) raised from eggs (North Carolina State University, Entomology Insectary) on an artificial diet. A total of 24 insects for each strain were used in this experiment. Insect virulence was assayed as previously described (12). Approximately 40 bacteria for each strain were injected into 12 fourth-instar larvae just below the horn by using a 26-gauge syringe, and the time when 50% of the population had died (LT50) for each strain was determined (15). To determine the LT50 for natural infection, 100 nematodes harboring either the wild-type or the ΔopnS strain were used to infect fourth-instar insect larva of M. sexta. The time of death was monitored over 48 h, and the LT50 was determined for each strain.

In vitro and in vivo colonization assays.

For in vitro colonization assays nematodes were reared on lawns of bacteria on nutrient oily agar plates (8 g of nutrient broth powder, 5 g of yeast extract, 15 g of agar, 4 ml of sterilized corn oil, 96 ml of 7.3% corn syrup, and 10 ml of 0.98 M MgSO4 per liter) as previously described (16). Briefly, strains were grown in LB medium to mid-log phase, plated on nutrient oily agar, and incubated at 30°C for 24 h. A total of 1,000 axenic IJs were surface sterilized with 1% bleach for 1 min, rinsed six times with sterile distilled water, and added to each plate. The plates were incubated in the dark for 2 weeks. Progeny IJs harvested in modified White traps (42) were surface sterilized as described above, and 200 IJs were resuspended in 250 μl of LB medium. Populations were ground for 2 min as previously described (16), diluted 20-fold, and plated on LB agar containing either 25 μg of ampicillin/ml or 12.5 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. To determine the level of in vitro colonization in competition, a 1:1 mixture of wild-type and mutant strains was plated on nutrient oily agar plates, followed by incubation for 24 h at 30°C. Axenic IJs were added to the bacterial lawns and incubated in the dark for 2 weeks. Emerging IJs were trapped in modified White traps, and the number of CFU per 200 IJs was determined as described above.

To determine the level of colonization in vivo, axenic nematodes, together with a 1:1 mixture of wild-type and mutant strains, were injected into fourth-instar larvae. Insect cadavers were trapped in modified White traps, and the number of CFU per 200 nematodes was determined. To determine the level of colonization in vivo by natural infection, M. sexta larvae were exposed to IJs carrying either the wild-type or the mutant strain; insects that died within 36 h were trapped, and the number of CFU per IJ was determined. To analyze the level of colonization under competitive conditions, a 1:1 mixture of nematodes colonized with either the wild-type or the mutant strain was injected into M. sexta. Insect cadavers were trapped in modified White traps, and the number of CFU per 200 nematodes was determined (16). The same competition experiment was carried out with the opnS-complemented and ΔopnS strains.

Growth of individual strains in hemolymph and Grace's medium.

Strains were grown in LB broth with selection at 30°C for 18 h. The strains were pelleted, washed, and resuspended in Grace's medium. Then, 3 μl of normalized culture was added to 100 μl of glutathione-treated hemolymph, followed by incubation at 30°C at 150 rpm. The OD600 was measured at 1-h intervals on a microtiter plate reader. The experiment was repeated three times. As a control, strains were inoculated into 100 μl of Grace's medium, and the OD600 was determined at similar time intervals. To asses growth under diluted hemolymph conditions, 1-ml portions of overnight cultures of the wild-type and ΔopnS strains grown in Grace's medium were centrifuged, and bacterial pellets were resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline containing 5% sucrose to a normalized OD600 of 2.2. The bacterial suspensions (5 μl) were used to inoculate hemolymph (250 μl) serially diluted with sterile phosphate-buffered saline containing 5% sucrose from 1:5- to 1:160-fold. The cultures were incubated for 18 h at 30°C, at which time the absorbance at OD600 was determined.

In vivo and in vitro competitive growth and survival assays.

For the in vivo assay, strains grown in Grace's medium at 30°C to early log phase were diluted (10−5), and a 1:1 mixture of the wild-type strain and the ΔopnS strain or a 1:1 mixture of the opnS-complement strain and ΔopnS strain was injected into fourth-instar larvae of M. sexta. The number of CFU in each mixture was determined by plating on agar plates containing antibiotic selection. After insect death, 100 μl of Grace's medium was injected by using a 26-gauge syringe just below the horn and ∼100 μl of hemolymph was extracted by making an incision at the last proleg using aseptic techniques. Hemolymph was withdrawn from insects at 24- and 48-h time points after injection. The ratios of wild-type strain to ΔopnS strain and of opnS-complemented to ΔopnS strain from extracted hemolymph were determined by dilution and plating samples on agar containing antibiotic selection.

To analyze the competitive growth in an vitro assay, overnight cultures of strains grown in Grace's medium at 30°C were subcultured to fresh Grace's medium and grown to early log phase. Then, 50 μl of a 1:1 mixture of wild-type and ΔopnS strains was inoculated into 500 μl of hemolymph, to which 40 μl of 5 mg of glutathione/ml was added. Aliquots of hemolymph were withdrawn at 4, 8, and 24 h; diluted; and plated on LB agar containing selection to determine the ratio of the wild type to the mutant strain. A similar experiment was performed for growth in Grace's medium by inoculating 50 μl of the 1:1 mixture of wild-type and ΔopnS strains into 5 ml of fresh Grace's medium. The experiments were repeated three times.

Analysis of growth inhibitory effects of mitomycin C and antibiotics.

We diluted 18-h cultures of wild-type and ΔopnS strains 100-fold in LB broth and then added 100 μl of diluted culture to 50 μl of serially diluted mitomycin C. The cultures were incubated at 30°C with shaking, and the OD600 was measured at 22 h. The absorbance of the cultures to which cell-free supernatants was added was compared to that of the untreated cultures. The antibiotic sensitivity was assayed using concentrations of 300 to 12.5 μg of streptomycin sulfate and kanamycin sulfate/ml prepared in Grace's medium. Overnight cultures of either wild-type or ΔopnS strains grown in Grace's medium were freshly inoculated into Grace's medium and grown to late log phase. Cultures were normalized based on the OD60, and 5 μl of culture inoculated into 100 μl of medium containing the respective antibiotics. The cultures were grown at 30°C with shaking at 150 rpm for 24 h. The final OD600 was recorded to determine growth of the cultures.

Statistical analysis.

A Student t test was performed by using GraphPad Prism, version 3.02 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for opnC, opnS, and opnT are FJ469622, FJ469623, and FJ469624, respectively.

RESULTS

Identification of OpnS as a growth-phase-regulated general porin.

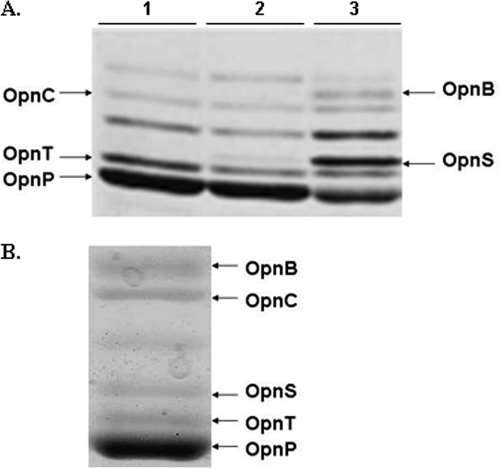

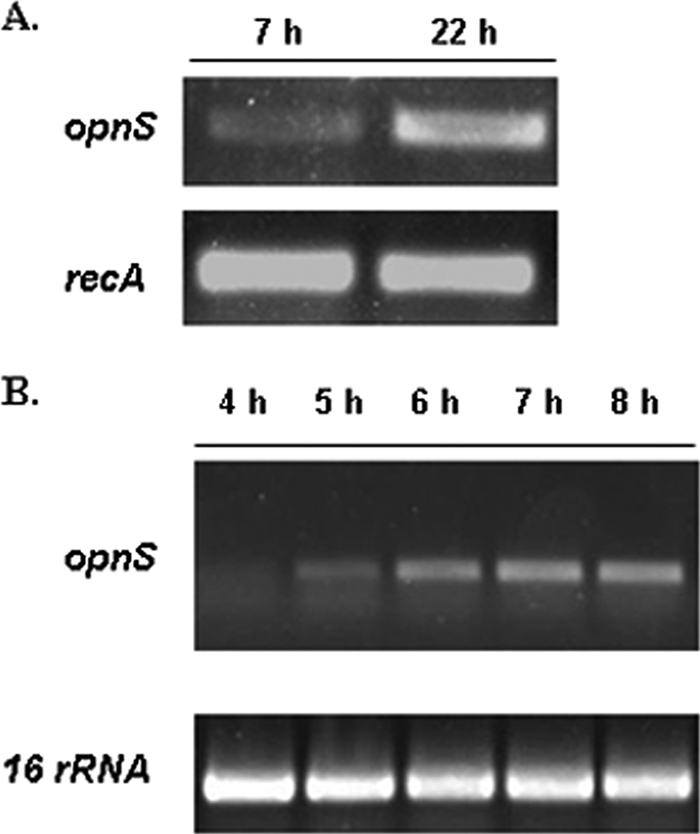

We previously observed that, as X. nematophila transitioned to stationary phase, de novo synthesis of the OpnP porin (11, 18) was diminished and the outer membrane protein, OpnS, was induced (Fig. 1A) (15, 22). In the present study we investigated the role of the growth-phase-regulated OpnS protein in the life cycle of X. nematophila. To determine whether OpnS was produced under biologically relevant conditions, outer membrane production was analyzed in X. nematophila grown in hemolymph obtained from M. sexta. Figure 1B shows that OpnS was produced in cells grown for 24 h in insect hemolymph.

FIG. 1.

Opn profile of X. nematophila. (A) Pulse-chase labeling depicting the de novo synthesis of outer membrane proteins in X. nematophila at the following phases of growth: lane 1, mid-log phase; lane 2, late log phase; and lane 3, transition phase. (B) Expression of porin OpnS in X. nematophila grown in hemolymph for 24 h.

N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis of outer membrane proteins derived from cells grown to stationary phase allowed us to identify the opnS gene in the completed genome sequence of X. nematophila (see Materials and Methods). BLASTP analysis revealed that OpnS was homologous to OmpF (52% identity) and OmpC (52% identity), and shared 59 and 58% amino acid sequence identity with OmpN of P. luminescence and OpnP of X. nematophila, respectively. Analysis of the completed genome revealed that opnP and opnS were the only general porin genes in X. nematophila.

The OpnS protein is composed of 382 amino acid residues including a leader peptide of 22 residues (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Secondary structure prediction showed that OpnS contained 16 antiparallel β-strands characteristic of the porin superfamily. Modeling of OpnS on the known crystal structures of OmpF, OmpC, and PhoE generated a three-dimensional view of the OpnS porin. This analysis revealed that OpnS is a 16-β-stranded structure (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material) containing a characteristic loop 3 that bends into the lumen forming the eyelet of the channel (Fig. S1C). Transmembrane β-sheet domains were more highly conserved, while the extracellular loop structures were more divergent (data not shown). Loop 3 in most porins in the Enterobacteriaceae contains the signature motif PEFGG. In contrast, the conserved glutamic acid residue is replaced with valine (PVFGG) in OpnS. Unlike the majority of general porins in Enterobacteriaceae that contain a highly conserved C-terminal YQF sequence, OpnS contains a YRF sequence at its C terminus. Finally, N-terminal sequence analysis also allowed us to identify OpnC as a fatty acid transporter (FadL), and OpnT as an OmpA-like protein. Analysis of the OpnB band gave several amino acid residues at each cycle, suggesting comigration of different proteins at this position in the gel.

The availability of the nucleotide sequence of opnS allowed us to analyze its expression in cells growing in insect hemolymph and in LB medium. RNA was extracted from cells grown in hemolymph for 7 and 22 h, and the level of opnS mRNA was monitored by RT-PCR (Fig. 2A). opnS expression was detected in cells grown for 7 h (lane 1), and the level of expression increased in cells grown for 22 h (lane 2). Similarly, opnS expression increased as the cells transitioned into stationary phase in LB broth (Fig. 2B). These findings indicate that opnS was growth phase regulated under laboratory conditions and the biologically relevant condition, insect hemolymph.

FIG. 2.

opnS expression in X. nematophila is growth phase dependent in hemolymph and LB. (A) opnS expression from cells grown in hemolymph at the 7- and 22-h time points. recA transcript level was used as an internal control. (B) RT-PCR analysis of opnS levels of cells grown in LB at the 4-, 5-, 6-, 7-, and 8-h time points. 16S rRNA was used as an internal control.

Construction and phenotypic characterization of a ΔopnS strain.

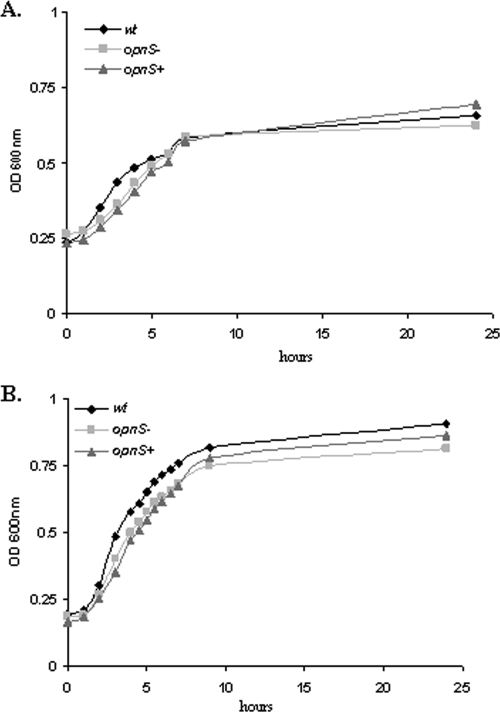

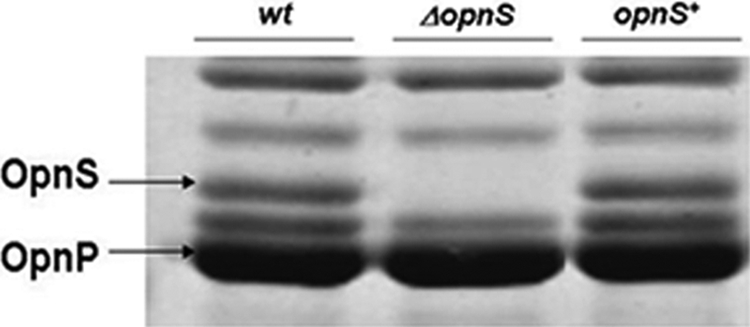

To examine the function of OpnS, a deletion strain was constructed by allelic exchange in which opnS was replaced with a chloramphenicol resistance cassette (Cmr). Deletion of the opnS gene was confirmed by PCR and RT-PCR. Analysis of the outer membrane proteins showed that the ΔopnS strain lacked OpnS (Fig. 3, lane 2). A complemented strain was created by inserting an opnS-containing Tn7 construct into the chromosome of the ΔopnS strain restoring synthesis of OpnS (Fig. 3, lane 3). Deletion of opnS did not alter growth rate in LB medium or swarming motility and did not affect hemolytic, lipolytic, and proteolytic activity. In addition, the ΔopnS strain produced the same level of antibiotic activity and bound bromothymol blue dye to the same extent as the wild-type strain (40).

FIG. 3.

Outer membrane protein profile for X. nematophila strains. Cells were grown to stationary phase in LB broth, and outer membrane proteins were extracted as previously described. Lane 1, wild-type strain; lane 2, ΔopnS strain; lane 3, complemented opnS+ strain.

In vivo characterization of the ΔopnS strain.

X. nematophila supports the reproduction of S. carpocapsae in the insect host. To determine whether deletion of opnS altered nematode reproduction, M. sexta larvae were exposed to IJs carrying either the wild-type or ΔopnS strain, and the resulting progeny were collected in White traps and counted. The insects died 30 to 36 h after exposure to the nematodes, and IJ progeny began to emerge from dead insects 8 days from the time of death. The total number of IJs emerging from the cadaver was monitored over a 22 day period (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). There was no significant difference in the number of IJs emerging from insects infected with IJs carrying either the wild-type or ΔopnS strain, indicating that cells lacking OpnS supported nematode reproduction as well as the wild-type strain.

Porins have been shown to be involved in virulence in other pathogenic bacteria (27, 35). To assess whether the ΔopnS mutant was defective in virulence, M. sexta larvae were injected with either the wild-type or the ΔopnS strain, and the time it took to kill 50% of the population (LT50) was determined. The LT50s were 29.5 ± 1 h and 28.9 ± 1 h for the wild-type and the ΔopnS strains, respectively. In addition, both strains produced 100% mortality by 36 h. Virulence was also assessed by exposing M. sexta larvae to IJs carrying either the wild-type or the ΔopnS strain. The LT50 was 31.5 ± 1 h and 30.0 ± 1 h for the wild-type and ΔopnS strain, respectively. Taken together, these findings indicate that deletion of opnS did not affect the virulence properties of X. nematophila.

Outer membrane porins may participate in the colonization of host organisms (1). To determine whether OpnS was required for X. nematophila to colonize the nematode host axenic IJs were grown on bacterial lawns of either the wild-type or the ΔopnS strain. The level of colonization was determined by maceration of the resulting IJ progeny and measuring the CFU per nematode. The level of colonization was not significantly different between the wild-type strain (59 ± 11 CFU/IJ) and the ΔopnS strain (57 ± 2 CFU/IJ). The level of colonization was also measured in an in vivo assay by exposing M. sexta larvae to IJs carrying either the wild-type or the ΔopnS strain, allowing nematodes to complete their life cycle in the insect cadaver and harvesting the resulting IJ progeny. The average CFU/IJ for nematodes colonized with the ΔopnS strain (81 ± 11) was slightly lower but not significantly different than for the wild-type strain (94 ± 4). Thus, OpnS does not appear to be required for colonization of the nematode. Interestingly, as demonstrated previously (16, 39), the level of colonization was significantly higher when nematodes were reproducing in the insect compared to on bacterial lawns.

The ΔopnS strain displayed a competitive defect for growth in insect hemolymph.

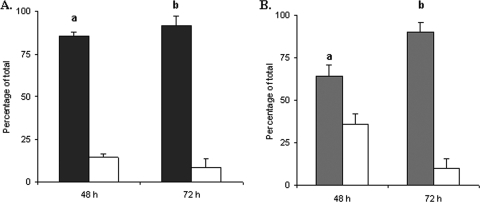

Competition conditions can reveal defects in a mutant strain that are not observed when the mutant strain is analyzed alone. To assess whether the ΔopnS strain was at a competitive disadvantage for growth in the insect host, M. sexta larvae were injected with a 1:1 mixture of wild-type and mutant strains. After death of the insect hemolymph was recovered and dilutionally plated on selective medium to distinguish the wild type from the ΔopnS strain. At 48 h postinjection the wild-type strain represented 80% of the recovered bacteria, and by 72 h the wild-type strain represented 90% of the recovered bacteria (Fig. 4A). The same experiment was performed with coinjection of a 1:1 mixture of the opnS-complemented strain (ompS+) and the ΔopnS strain. By 72 h the complemented strain represented ca. 90% of the recovered bacteria (Fig. 4B). Together, these findings indicated that the ΔopnS strain was defective for competitive growth or survival in the insect host.

FIG. 4.

The ΔopnS strain displays a competitive disadvantage for growth in the insect host. (A) Insects were injected with a 45:55 mixture of wild-type (▪) and ΔopnS (□) strains. At 48 and 72 h, hemolymph was withdrawn and plated on LB agar containing either ampicillin (total bacteria) or chloramphenicol (ΔopnS strain). The data represent the means and standard deviations of two independent experiments using five insects for each time point. a, P < 0.01; b, P < 0.0001. (B) Insects were injected with a 45:55 mixture of opnS+ (░⃞) and ΔopnS (□) strains. At 48 and 72 h, hemolymph was withdrawn and plated on LB agar containing either chloramphenicol (total bacteria) or gentamicin (opnS+). The data represent the means and standard deviations of three independent experiments using five insects for each time point. a, P < 0.05; b, P < 0.001.

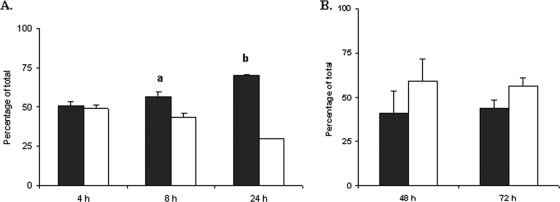

To address the question of whether the ΔopnS strain displayed a competitive defective for growth in hemolymph, a 1:1 mixture of wild-type and mutant strains was inoculated into fresh hemolymph obtained from M. sexta. Aliquots were withdrawn at 4, 8, and 24 h and dilutionally plated on selective medium. The ΔopnS strain did not display a defect at the 4-h time point but was recovered at lower levels by 8 h. At 24 h it represented less than 30% of the total bacterial population (Fig. 5A). These findings suggested that the ΔopnS strain displayed a competitive defect for postexponential growth or survival in insect hemolymph. To determine whether the competitive defect of the ΔopnS strain was specific for growth in hemolymph, a 1:1 mixture of wild-type and ΔopnS strains was inoculated into Grace's insect cell culture medium. Under these conditions the mutant strain actually displayed a slight growth advantage compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 5B). Thus, OpnS was required for competitive growth in insect hemolymph but not in defined laboratory growth medium.

FIG. 5.

OpnS is necessary for growth in hemolymph under competitive conditions. (A) Hemolymph was inoculated with a 1:1 mixture of wild-type (▪) and ΔopnS (□) strains. At 4, 8, and 24 h, hemolymph was withdrawn and plated on LB agar containing either ampicillin (total bacteria) or chloramphenicol (ΔopnS strain). The data represent the means and standard deviations of three independent experiments. a, P < 0.05; b, P < 0.001. (B) Grace's medium was inoculated with a 1:1 mixture of wild-type (▪) and ΔopnS (□) strains. At 48 and 72 h, the medium was withdrawn and plated on LB agar containing either ampicillin (total bacteria) or chloramphenicol (ΔopnS strain). The data represent the means and standard deviations of three independent experiments.

We next compared the growth rate of the wild-type, ΔopnS, and complemented strains inoculated individually into hemolymph (Fig. 6A). The growth rate was the same for the wild type, ΔopnS, and complemented strains, indicating that the growth defect for the ΔopnS strain was revealed under competition conditions but not when the bacteria were grown alone in hemolymph. We also examined the viability of the wild-type and ΔopnS grown in hemolymph for 24 h by dilutional plating on selective medium. The viability of the strains was indistinguishable (data not shown). The question of whether OpnS was required for growth under nutrient limitation conditions was addressed by growing both strains in serially diluted hemolymph. The final cell density of both the wild-type and the ΔopnS strain was comparable for all diluted hemolymph conditions examined. The cell growth of the wild-type and ΔopnS strain was the same even when the hemolymph was diluted 160-fold, and the final cell density was reduced 12-fold relative to growth in undiluted hemolymph. These findings argue against the idea that OpnS provides a growth advantage under nutrient limiting conditions. Finally, the growth rate of the wild type, ΔopnS, and complemented strains were analyzed in Grace's insect cell culture medium and, as expected, all three grew at the same rate (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Disruption of opnS gene has no effect on the rate of growth. (A) Wild-type or ΔopnS strains were inoculated into 100 μl of hemolymph, and the OD600 was recorded over a period of 24 h. (B) Wild-type or ΔopnS strains were inoculated into 100 μl of Grace's medium, and the OD600 was recorded over a period of 24 h. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

The ΔopnS strain is competitively defective for in vivo colonization.

Since the ΔopnS strain displayed a competitive growth defect in the insect, we reasoned that nematodes developing in hosts coinfected by both the wild-type and ΔopnS strain would be predominantly colonized by the wild-type strain. To test this prediction, M. sexta larvae were coinjected with a 1:1 mixture of wild-type and ΔopnS strain together with 40 axenic IJs. After insect death, the cadavers were placed in White traps. IJ progeny were collected after 20 days, surface sterilized, and macerated, and the homogenate was dilutionally plated on selective medium to determine the number of wild-type and ΔopnS cells carried by the nematodes. Table 3 shows that the IJs were almost exclusively colonized with the wild-type strain. To further assess the apparent competitive defect for in vivo colonization, a mixture containing 20 IJs colonized with the wild-type strain and 20 IJs colonized with the ΔopnS strain was injected into M. sexta. IJ progeny collected from insect cadavers over a 20-day period were found to be predominantly colonized by wild-type strain (Table 3). In a parallel experiment a mixture containing 20 IJs colonized with the opnS-complemented strain and 20 IJs colonized with the ΔopnS strain was injected into larvae of M. sexta. IJs obtained from insects cadavers were almost exclusively colonized by the complemented strain (Table 3). These findings are consistent with the idea that the ΔopnS strain displays a competitive growth or survival defect in the insect so that nematodes developing in a host coinfected with both the wild-type and the ΔopnS strains are predominantly colonized by the wild-type strain.

TABLE 3.

Competitive colonization with wild-type, ΔopnS, and complemented strains

| Strain mixture | Bacterial recovery (103 CFU/200 IJs)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type

|

Complemented strain

|

|||

| Wild type | ΔopnS strain | opnS+ strain | ΔopnS strain | |

| 1:1 mixture injected into insects | ||||

| Wild-type and ΔopnS strains plus axenic IJs | 21.0 (2.8) | 1.3 (1.0) | ||

| IJs carrying wild-type strain and IJs carrying ΔopnS strain | 14.8 (2.3) | 0.1 (0.0) | ||

| IJs carrying complemented strain and IJs carrying mutant strain | 13.2 (2.0) | 1.1 (0.9) | ||

| 1:1 mixture, lawn on oily agar | ||||

| Wild-type and ΔopnS strains plus axenic IJs | 6.9 (2.6) | 10.5 (3.8) | ||

The values represent the means of experiments performed three times, with standard deviations in parentheses.

The ΔopnS strain is not competitively defective for in vitro colonization.

The finding that the ΔopnS strain did not display a competitive growth defect in laboratory medium (see Fig. 5B) predicted that IJs growing on bacterial lawns consisting of a mixture of wild-type and ΔopnS strain would not be preferentially colonized with the wild-type strain. To test this prediction, a 1:1 mixture of wild-type and ΔopnS strain was plated on oily agar and incubated for 24 h. Axenic IJs were added to the bacterial lawns and allowed to reproduce over a period of 2 weeks. The IJ progeny were recovered, surface sterilized, and macerated, and the homogenates were dilutionally plated on selective medium. Table 3 shows that the IJs were colonized by both the wild-type and mutant strains. In fact, under these conditions the ΔopnS strain appeared to colonize slightly better than the wild-type strain. These findings argue that the competitive defect for colonization in the insect was due to a competitive growth or survival defect rather than a defect in the colonization process.

Analysis of the outer membrane permeability and/or stability of the ΔopnS strain.

The results presented above raised the possibility that the absence of OpnS may enhance outer membrane permeability and/or decrease membrane stability. The sensitivity to mitomycin C, which inhibits growth and induces cell lysis in X. nematophila (5), was analyzed to assess alterations in outer membrane permeability. Wild-type cells were unable to grow in the presence of 1.0 μg of mitomycin C/ml but grew in the presence of 0.5 μg of mitomycin C/ml. The ΔopnS strain was fourfold more sensitive to mitomycin C. It did not grow in the presence of 0.25 μg of mitomycin C/ml but grew in the presence of 0.13 μg of mitomycin C/ml. The opnS strain was also more sensitive to the antibiotics streptomycin and kanamycin. The MIC for the wild-type strain for both antibiotics was 200 μg/ml. In contrast, the MICs for the ΔopnS strain for streptomycin and kanamycin were 50 and 100 μg/ml, respectively. These findings suggest that deletion of OpnS affected the integrity of the outer membrane and sensitized the cell to perturbations by inhibitory compounds.

DISCUSSION

It was observed previously that de novo synthesis of OpnS increased as X. nematophila transitioned to the stationary phase (15, 22). In the present study, OpnS was found to be a 16-β-stranded porin belonging to the OmpF-OmpC superfamily. OpnS was the only general porin identified in the genome of X. nematophila besides OpnP. An opnS deletion strain was constructed to study the role of OpnS in the life cycle of X. nematophila.

To ascertain whether deletion of opnS affected growth, the ΔopnS strain was incubated in laboratory medium and insect hemolymph. In both Grace's insect cell culture medium and M. sexta hemolymph the ΔopnS strain grew at the same rate and to the same final cell density as the wild-type strain. In addition, the ΔopnS strain did not display a competitive disadvantage for growth in Grace's medium. It was recently shown that the constitutively expressed M35 porin of Moraxella catarrhalis was required for growth under nutrient-limiting conditions (10). In contrast, OpnS was not required for growth under nutrient-limiting conditions since growth of the ΔopnS strain in serially diluted hemolymph was comparable to that of the wild-type strain.

Inactivation of porin genes has been shown to have variable effects on virulence (7, 31, 33, 34). We show that the ΔopnS strain was not attenuated for virulence against M. sexta since it killed the insect host as well as the wild-type strain by both direct injection and by natural infection with nematodes. The role of porins in mutualistic host interactions has been less well studied. In V. fisheri an ompU strain was shown to colonize the squid host less efficiently than the wild-type strain (1). We found that the ΔopnS strain colonized nematodes to the same extent as the wild-type strain, as measured both in vitro (growth on bacterial lawns) and by natural infection (exposure of IJs to the insect host). In addition, the ΔopnS strain did not display a competitive defect for colonization in vitro. Together, these findings indicate that OpnS was not required for efficient colonization of the nematode and suggest that OpnP is the primary porin used during the colonization process.

Deletion of general porins in proteobacteria has been found to enhance sensitivity to antibiotics, antimicrobial peptides, and detergents (26, 33). We show that the absence of OpnS in X. nematophila enhanced sensitivity to the antibiotics streptomycin and kanamycin. In addition, the ΔopnS strain was more sensitive to mitomycin C. Recent findings with porin-deficient strains indicate that several distinct mechanisms may be involved in the maintenance of envelope integrity and adaptive response to membrane perturbations. In V. cholerae OmpU confers resistance to the antimicrobial peptides polymixin B and the bioactive peptide P2 (25, 26). The presence of OmpU was shown to be necessary for the activation DegS, which modulates the activity of σE via the anti-σE protein RseA. The membrane-perturbing properties of P2 were proposed to stimulate interaction between the C-terminal YDF sequence of OmpU and DegS to stimulate the protease activity of DegS and cleavage of RseA, resulting in the activation of σE. Cells lacking OmpU were defective in the activation of σE. Whether the C-terminal YRF sequence of OpnS is involved in sensing membrane perturbations in X. nematophila remains to be determined. In Haemophilus ducreyi deletion of the porins OmpP2A and OmpP2B enhanced sensitivity to erythromycin, antimicrobial compounds, and several detergents (8). Proteomic comparison between membrane proteins of the parent and the ompP2AB porin-deficient strain revealed that the absence of porins stimulated a global response in which numerous proteins of diverse function were differentially expressed in the mutant strain. Several proteins were associated with stress responses and membrane stability. For example, production of GroEL was increased and production of the Imp protein involved in lipopolysaccharide/lipooligosaccharide export was reduced in the ompP2AB strain. Reduced lipopolysaccharide content could account for increased permeability of the outer membrane.

In addition to enhanced sensitivity to inhibitory compounds we show that deletion of opnS resulted in a competitive growth defect in the insect. Thus, the ΔopnS strain was outcompeted by both wild-type and complemented strain when coinjected directly into M. sexta. This competitive defect was also observed when ΔopnS-colonized IJs were coinjected with IJs carrying either the wild-type or opnS-complemented strains. Similarly, when M. sexta was coinjected with a mixture of wild-type and ΔopnS strains together with axenic IJs, the emerging IJ progeny were predominantly colonized with the wild-type strain. Furthermore, the competitive growth defect was observed in insect hemolymph but not in defined laboratory medium. The growth defect in hemolymph was not observed early in growth (4 h), was detectable by 8 h, and was most dramatic under 24-h stationary-phase conditions. These findings raise the question of why the growth defect of ΔopnS strain was observed in hemolymph and not in laboratory medium. One possibility for the competitive defect is that inhibitory compounds such as antibiotics (11, 19, 20) and colicinlike proteins (38) are produced and accumulate at concentrations high enough in growth in hemolymph to inhibit the ΔopnS strain that is apparently more sensitive than the wild-type strain. In this case growth of the ΔopnS strain alone presumably does not result in a high enough concentration of inhibitory compounds to affect the growth of the mutant strain. An alternative possibility is that as the wild-type strain grows, the hemolymph components are progressively metabolized and modified, creating inhibitory conditions for the ΔopnS strain. In either of these scenarios elucidation of the mechanism of the competitive growth defect of the ΔopnS strain will require a detailed comparative analysis of changes in the composition of the hemolymph during growth of the wild-type strain versus the ΔopnS strain.

OpnS was shown to be growth phase regulated both in laboratory medium and insect hemolymph. Growth phase regulation of porins has not been well studied. Using steady-state continuous cultures to separate the growth phase from cell density effects (23), OmpF was found to be strongly repressed and OmpC levels increased in E. coli grown at high cell densities. The expression of OpnS and OpnP is reciprocally regulated in a similar fashion in X. nematophila. These observations, together with the finding that in hemolymph the presence of OpnS conferred a competitive growth advantage under stationary-phase conditions, suggests that in the insect hemocoel OpnS functions later in the growth phase, possibly by maintaining the integrity of the cell envelope. This hypothesis is currently under investigation in our laboratory. Although general porins in numerous bacteria have been shown to be reciprocally regulated under in vitro conditions, the significance of this regulation in natural biological settings remains poorly understood. The X. nematophila-nematode-insect system provides a model for studying the biological relevance of differential function and regulation of porins in a natural host environment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Daad Saffarini, Mark McBride, and Herbert Schweizer for providing plasmids and strains for this study. We also thank Jane Witten for providing M. sexta eggs and larvae. We thank Douglas Pietz and Trayton Spencer for assisting in the competition experiments, as well as for rearing M. sexta.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 May 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aeckersberg, F., C. Lupp, B. Feliciano, and E. G. Ruby. 2001. Vibrio fischeri outer membrane protein OmpU plays a role in normal symbiotic colonization. J. Bacteriol. 1836590-6597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhurst, R. J. 1983. Neoaplectana species: specificity of association with bacteria of the genus Xenorhabdus. Exp. Parasitol. 55258-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basle, A., G. Rummel, P. Storici, J. P. Rosenbusch, and T. Schirmer. 2006. Crystal structure of osmoporin OmpC from Escherichia coli at 2.0 Å. J. Mol. Biol. 362933-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bird, A. F., and R. J. Akhurst. 1983. The nature of the intestinal vesicle in nematodes of the family Steinernematidae. Int. J. Parasitol. 13599-606. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boemare, N. E., M. H. Boyer-Giglio, J. O. Thaler, R. J. Akhurst, and M. Brehelin. 1992. Lysogeny and bacteriocinogeny in Xenorhabdus nematophilus and other Xenorhabdus spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 583032-3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi, K. H., J. B. Gaynor, K. G. White, C. Lopez, C. M. Bosio, R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, and H. P. Schweizer. 2005. A Tn7-based broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nat. Methods 2443-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cope, L. D., S. E. Pelzel, J. L. Latimer, and E. J. Hansen. 1990. Characterization of a mutant of Haemophilus influenzae type b lacking the P2 major outer membrane protein. Infect. Immun. 583312-3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davie, J. J., and A. A. Campagnari. 2009. Comparative proteomic analysis of the Haemophilus ducreyi porin-deficient mutant 35000HP::P2AB. J. Bacteriol. 1912144-2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dehio, C., and M. Meyer. 1997. Maintenance of broad-host-range incompatibility group P and group Q plasmids and transposition of Tn5 in Bartonella henselae following conjugal plasmid transfer from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179538-540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Easton, D. M., E. Maier, R. Benz, A. R. Foxwell, A. W. Cripps, and J. M. Kyd. 2008. Moraxella catarrhalis M35 is a general porin that is important for growth under nutrient-limiting conditions and in the nasopharynges of mice. J. Bacteriol. 1907994-8002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forst, S., B. Dowds, N. Boemare, and E. Stackebrandt. 1997. Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus spp.: bugs that kill bugs. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 5147-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forst, S., and M. Inouye. 1988. Environmentally regulated gene expression for membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 421-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forst, S., and K. Nealson. 1996. Molecular biology of the symbiotic-pathogenic bacteria Xenorhabdus spp. and Photorhabdus spp. Microbiol. Rev. 6021-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forst, S., J. Waukau, G. Leisman, M. Exner, and R. Hancock. 1995. Functional and regulatory analysis of the OmpF-like porin, OpnP, of the symbiotic bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophilus. Mol. Microbiol. 18779-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forst, S. A., and N. Tabatabai. 1997. Role of the histidine kinase, EnvZ, in the production of outer membrane proteins in the symbiotic-pathogenic bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63962-968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goetsch, M., H. Owen, B. Goldman, and S. Forst. 2006. Analysis of the PixA Inclusion Body Protein of Xenorhabdus nematophila. J. Bacteriol. 1882706-2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hancock, R. E. W. 1991. Bacterial outer membranes: evolving concepts. ASM News 57175-182. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herbert, E. E., and H. Goodrich-Blair. 2007. Friend and foe: the two faces of Xenorhabdus nematophila. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5634-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isaacson, P. J., and J. M. Webster. 2002. Antimicrobial activity of Xenorhabdus sp. RIO (Enterobacteriaceae), symbiont of the entomopathogenic nematode, Steinernema riobrave (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 79146-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarosz, J. 1996. Ecology of anti-microbials produced by bacterial associates of Steinernema carpocapsae and Heterorhabditis bacteriophora. Parasitology 112(Pt. 6)545-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawaji, H., T. Mizuno, and S. Mizushima. 1979. Influence of molecular size and osmolarity of sugars and dextrans on the synthesis of outer membrane proteins O-8 and O-9 of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 140843-847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leisman, G. B., J. Waukau, and S. A. Forst. 1995. Characterization and environmental regulation of outer membrane proteins in Xenorhabdus nematophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61200-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, X., C. Ng, and T. Ferenci. 2000. Global adaptations resulting from high population densities in Escherichia coli cultures. J. Bacteriol. 1824158-4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martens, E. C., K. Heungens, and H. Goodrich-Blair. 2003. Early colonization events in the mutualistic association between Steinernema carpocapsae nematodes and Xenorhabdus nematophila bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1853147-3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathur, J., B. M. Davis, and M. K. Waldor. 2007. Antimicrobial peptides activate the Vibrio cholerae sigmaE regulon through an OmpU-dependent signalling pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 63848-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathur, J., and M. K. Waldor. 2004. The Vibrio cholerae ToxR-regulated porin OmpU confers resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Infect. Immun. 723577-3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mills, S. D., S. R. Ruschkowski, M. A. Stein, and B. B. Finlay. 1998. Trafficking of porin-deficient Salmonella typhimurium mutants inside HeLa cells: ompR and envZ mutants are defective for the formation of Salmonella-induced filaments. Infect. Immun. 661806-1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikaido, H. 2003. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67593-656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikaido, H. 1993. Transport across the bacterial outer membrane. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 25581-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikaido, H., and M. Vaara. 1985. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol. Rev. 491-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osorio, C. G., H. Martinez-Wilson, and A. Camilli. 2004. The ompU paralogue vca1008 is required for virulence of Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 1865167-5171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park, D., and S. Forst. 2006. Co-regulation of motility, exoenzyme and antibiotic production by the EnvZ-OmpR-FlhDC-FliA pathway in Xenorhabdus nematophila. Mol. Microbiol. 611397-1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Provenzano, D., and K. E. Klose. 2000. Altered expression of the ToxR-regulated porins OmpU and OmpT diminishes Vibrio cholerae bile resistance, virulence factor expression, and intestinal colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9710220-10224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Provenzano, D., C. M. Lauriano, and K. E. Klose. 2001. Characterization of the role of the ToxR-modulated outer membrane porins OmpU and OmpT in Vibrio cholerae virulence. J. Bacteriol. 1833652-3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Morales, O., M. Fernandez-Mora, I. Hernandez-Lucas, A. Vazquez, J. L. Puente, and E. Calva. 2006. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ompS1 and ompS2 mutants are attenuated for virulence in mice. Infect. Immun. 741398-1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sicard, M., K. Brugirard-Ricaud, S. Pages, A. Lanois, N. E. Boemare, M. Brehelin, and A. Givaudan. 2004. Stages of infection during the tripartite interaction between Xenorhabdus nematophila, its nematode vector, and insect hosts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 706473-6480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simonet, V. C., A. Basle, K. E. Klose, and A. H. Delcour. 2003. The Vibrio cholerae porins OmpU and OmpT have distinct channel properties. J. Biol. Chem. 27817539-17545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh, J., and N. Banerjee. 2008. Transcriptional analysis and functional characterization of a gene pair encoding iron-regulated xenocin and immunity proteins of Xenorhabdus nematophila. J. Bacteriol. 1903877-3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snyder, H., S. P. Stock, S. K. Kim, Y. Flores-Lara, and S. Forst. 2007. New insights into the colonization and release processes of Xenorhabdus nematophila and the morphology and ultrastructure of the bacterial receptacle of its nematode host, Steinernema carpocapsae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 735338-5346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Hoeven, R. 2008. The function and the expression of the growth phase regulated porin OpnS in the mutualistic bacterium, Xenorhabdus nematophila. Ph.D. thesis. University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

- 41.Verhoef, C., B. Lugtenberg, R. van Boxtel, P. de Graaff, and H. Verheij. 1979. Genetics and biochemistry of the peptidoglycan-associated proteins b and c of Escherichia coli K12. Mol. Gen. Genet. 169137-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.White, G. F. 1927. A method for obtaining infective nematode larvae from cultures. Science 66302-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.