Abstract

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae kinase Bur1 is involved in coupling transcription elongation to chromatin modification, but not all important Bur1 targets in the elongation complex are known. Using a chemical genetics strategy wherein Bur1 kinase was engineered to be regulated by a specific inhibitor, we found that Bur1 phosphorylates the Spt5 C-terminal repeat domain (CTD) both in vivo and in isolated elongation complexes in vitro. Deletion of the Spt5 CTD or mutation of the Spt5 serines targeted by Bur1 reduces recruitment of the PAF complex, which functions to recruit factors involved in chromatin modification and mRNA maturation to elongating polymerase II (Pol II). Deletion of the Spt5 CTD showed the same defect in PAF recruitment as rapid inhibition of Bur1 kinase activity, and this Spt5 mutation led to a decrease in histone H3K4 trimethylation. Brief inhibition of Bur1 kinase activity in vivo also led to a significant decrease in phosphorylation of the Pol II CTD at Ser-2, showing that Bur1 also contributes to Pol II Ser-2 phosphorylation. Genetic results suggest that Bur1 is essential for growth because it targets multiple factors that play distinct roles in transcription.

Transcription elongation is tightly regulated and is a key step in gene regulation. RNA polymerase II (Pol II) entry into the elongation phase initiates a cascade of events promoting recruitment of factors that are involved in mRNA maturation, chromatin modification and remodeling, and mRNA export (30, 53, 57). Phosphorylation of the Pol II C-terminal domain (CTD) on Ser-5 during transcription initiation leads to recruitment of the mRNA capping complex (52, 62). The elongation factor Spt4/5 is next recruited to the elongating polymerase, promoting subsequent recruitment of the PAF complex (50). The PAF-containing elongation complex forms a platform for recruitment of the H2B ubiquitylation enzymes Rad6/Bre1 and the Set1/COMPASS complex that methylates histone H3K4 (32, 43, 53). Concurrent phosphorylation of the Pol II CTD at Ser-2 allows recruitment of the Set2 methyltransferase (53, 57), catalyzing methylation of H3K36. This methylation mark leads to recruitment of the Rpd3s histone deacetylase complex, a key step in preventing cryptic transcription initiation within open reading frames (7, 21, 24). While much progress has been made in defining this pathway, the mechanism and regulation of several key steps remain to be determined.

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, four cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) play important roles in transcription initiation and elongation (48). Kin28 (CDK7), a subunit of the general transcription factor TFIIH, phosphorylates the Pol II CTD at Ser-5 during transcription initiation, stimulating promoter clearance but not generally affecting polymerase elongation (22, 35). Srb10 (CDK8), a subunit of the Mediator complex, phosphorylates at least four site-specific DNA-binding proteins (Gal4, Ste12, Gcn4, and Msn2), altering their activity by different mechanisms (11, 18, 40). Srb10 has also been proposed to inhibit initiation under certain conditions (17) and has been shown to function positively in initiation in the absence of Kin28 kinase activity (35). Ctk1, a subunit of the CTDK complex, is the principal kinase responsible for phosphorylation of the Pol II CTD at Ser-2. (12, 20). In addition to Set2 recruitment, Ser-2 phosphorylation is also important for association of polyadenylation and termination factors (1) and for confining methylation of H3K4 to the 5′ end of gene coding sequences (66). However, deletion of CTK1 does not alter the distribution of Pol II along coding sequences, indicating that it is not directly involved in transcription elongation (1). In contrast, the essential kinase Bur1 and its associated cyclin Bur2 were reported to regulate transcription elongation, because lower levels of Pol II cross-linked to the middle and 3′ end of the PMA1 gene were observed in a bur1 temperature-sensitive (ts) mutant after heat shock (25). Yeast Bur1 and Ctk1 are both similar in sequence to the higher eukaryotic kinase CDK9 (p-TEFb), which has been shown to regulate elongation in Drosophila melanogaster and mammalian cells (53).

Genetic and molecular studies have shown that at least one important Bur1 function lies downstream of Spt4/5 recruitment but upstream of Paf1 (31, 50, 64). bur1 ts and bur2Δ mutations do not affect recruitment of Spt4/5 to coding sequences but result in reduced levels of Paf1 cross-linked to coding sequences and lower levels of H3K4 trimethylation. The slow growth phenotype of the bur2Δ deletion can be suppressed by inactivation of certain Paf1 subunits, Set2, or subunits of the Rpd3s complex and by overexpression of two histone demethylases (13, 24, 27). Based on these results, it has been suggested that Bur1 and Rpd3s have opposing functions to stimulate or inhibit elongation. Recently it was shown that Bur1 binds the Ser-5-phosphorylated Pol II CTD and that Bur1 contributes to CTD Ser-2 phosphorylation at the 5′ end of coding sequences (49). It was proposed that this Bur1-dependent CTD phosphorylation enhances activity of Ctk1 and results in hyperphosphorylation of the Pol II CTD at Ser-2. Finally, it was shown that Bur1 can phosphorylate Ser-120 of Rad6, the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme involved in H2B ubiquitylation (64). However, neither phosphorylation of the Pol II CTD nor that of Rad6 alone can explain the essential function of Bur1; since H2B ubiquitylation is not essential for viability and inactivation of Ctk1, the major Pol II Ser-2 CTD kinase is not lethal. These observations suggest that Bur1 has other important substrates within the elongation complex.

The elongation factor Spt4/5 was originally defined biochemically as the mammalian factor DRB sensitivity inducing factor (DSIF), which confers sensitivity to the kinase inhibitor DRB (61). Upon inhibition of CDK9 kinase activity, mammalian Spt4/5 acts to inhibit elongation, although it positively stimulates elongation under normal conditions. Yeast Spt4/5 was identified by SPT5 mutations that alter the transcription start site (58), while mutations in yeast SPT4 were shown to affect Pol II processivity (38). Spt4 and Spt5 interact both genetically and physically with a number of factors involved in elongation, suggesting a key role in elongation (16, 33, 34, 45, 47). CDK9 phosphorylates mammalian Spt5, and it has been suggested that this phosphorylation blocks the negative function of Spt4/5 (6, 19, 26, 45, 46). In contrast, no negative role in elongation has been described for yeast Spt4/5. Although the Bur1, Kin28, Srb10, and Ctk1 kinases were all found to phosphorylate purified Spt5 in vitro (25), a functional role for Spt5 phosphorylation by any yeast kinase has not yet been demonstrated.

In this work, we used an analog-specific BUR1 allele (BUR1-as) to identify Bur1 kinase substrates in a transcription elongation complex (EC). We find that Bur1 phosphorylates both the C-terminal repeat domain of Spt5 and the Pol II CTD at Ser-2. Drug inactivation of Bur1-as kinase activity rapidly decreases both Spt5 phosphorylation and in vivo recruitment of the PAF to the EC. Our results suggest that an important function of Bur1 is phosphorylation of Spt5, stimulating PAF recruitment to the elongation complex. Our results also show that rapid inactivation of Bur1 kinase activity does not lead to a general defect in Pol II elongation under normal growth conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmids.

Yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. C-terminal tagging of Bur1, Bur1-as (Bur1 L149G), and Rad6 with 3 copies of Flag and C-terminal tagging of Paf1 and Spt5 with 13 copies of the Myc epitope were performed by using a PCR-based method (37). Gene disruptions were carried out by using a PCR-based method (60). YL44 and YL45 were constructed by the plasmid shuffle method using YL21 as the shuffle strain and YL57 and YL58 using YL56 as the shuffle strain. Plasmid pRS313-SPT5 or pRS316-SPT5 was constructed by cloning SPT5 into pRS313 or pRS316 vectors. N-terminal Flag tagging of the SPT5 product was performed by inserting a 66-bp DNA fragment encoding three copies of Flag into these plasmids using QuikChange mutagenesis to create the plasmid PO1, which was used to make all other SPT5 mutations.

Purification of R3 lac repressor.

The R3 open reading frame was cloned into pRSETb (Invitrogen) and expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) (Novagen) without a six-His tag. The repressor protein was then purified as described previously (9, 10). In brief, after cell lysis and removal of debris by centrifugation, the R3 lac repressor was precipitated by adding ammonium sulfate to 37% saturation. After centrifugation, the precipitate was resuspended in 80 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 0.3 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 5% (wt/vol) glucose and dialyzed overnight against the same buffer. After removal of insoluble material, the sample was applied to a phosphocellulose column (Whatman P11) equilibrated in 120 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.5), 0.3 mM DTT, and 5% (wt/vol) glucose. After loading, the column was washed with 120 mM phosphate buffer. The R3 lac repressor protein was eluted during the wash in a second peak following and well separated from the flowthrough in 120 mM phosphate buffer.

Isolation of the transcription EC.

Immobilized DNA template was prepared as described previously (51) except that a Lac repressor binding site, AATTGTGAGCGCTCACAATT, was inserted 123 bp downstream of the transcription start site by in vitro mutagenesis. Preinitiation complex (PIC) formation experiments were performed as described previously (51). EC formation was performed similarly to PIC assays with the following modifications. A 2-μg/ml amount of Lac repressor R3 and nuclear extract was coincubated with the DNA template with bound Gal4 activator for 10 min. Transcription was initiated by adding 400 μM nucleoside triphosphate (NTP), and the reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 40 min. After gentle washing (2 × 100 μl), the EC complex was released from magnetic beads using 60 U BamHI and analyzed by Western blotting.

EC-kinase assay.

N6-phenethyl-ADP and other ADP analogs were produced as described previously (35), and the analogs were converted to [γ-32P]ATP derivatives using enzymatic synthesis as described previously (5). The EC was formed on the immobilized template, washed once, and resuspended in 50 μl transcription buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.6], 100 mM potassium acetate, 0.05 mM EDTA, 3.5% glycerol, 2.5 mM DTT). Purified Bur1-as (6 ng) and 600 μM ATP/N6-phenethyl-[γ-32P]ATP was added to the EC and incubated for 10 min. The complex was washed once and isolated by digestion with 60 U BamHI.

To immunoprecipitate analog-labeled factors, the washed complex derived from the kinase reaction was resuspended in 100 μl disruption buffer (transcription buffer with 1 M potassium acetate and 0.05% NP-40) and incubated at room temperature (RT) for 20 min with gentle mixing. The supernatant was saved for immunoprecipitation. Anti-Myc antibody (9E10) was cross-linked to Dynabeads protein G according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Four microliters of anti-Myc-conjugated beads were incubated with the 100 μl saved supernatant and incubated for 2 h at 4°C. After washing with disruption buffer, the collected beads were boiled in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer and the supernatant was loaded to a 3 to 8% Tris-acetate gel.

Immobilized-template transcription.

Nuclear extract was incubated with the immobilized DNA template with bound Gal4 activator in the presence or absence of Lac R3 for 10 min. To initiate transcription, 400 μM NTP was added, and after a 40-min incubation, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 360 μl of stop mix. RNA transcripts were analyzed by primer extension as described previously (51).

Recombinant Spt5.

SPT5 was cloned into pET21a (Novagen) with an N-terminal six-His tag and expressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3) RIL (Stratagene). His6-rSpt5 was purified using Ni Sepharose high-performance medium according to the manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare).

Purified complexes.

Wild-type Bur1 (Bur1-WT), Bur1-as, Flag-Spt5, Flag-Spt5ΔCTD-15, or Rad6-Flag complex was purified from yeast nuclear extract made from the corresponding Flag-tagged strains. Typically, 4 mg nuclear extract was incubated with 30 μl anti-Flag M2 beads (Sigma) in binding buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 0.1% NP-40) at 4°C for 2 h. After extensive washing with wash buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 350 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 0.15% NP-40), the Flag-tagged complex was eluted with 0.25 mg/ml triple Flag peptide (Sigma).

In vitro kinase assay.

For Fig. 4A, rSpt5 (50 or 200 ng) and purified Bur1 kinase complex (4 or 2 ng of Bur1) were incubated in a 30-μl reaction mixture containing 0.5 mM ATP/[γ-32P]ATP at RT for 40 min. Half of the reactions were resolved by a 3 to 8% Tris-acetate gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Phosphorimaging and Western blotting were performed on the same membrane. For Fig. 3C, Flag-Spt5, Flag-Spt5ΔCTD-15, or Rad6-Flag complex (about 10 ng Flag tagged factors) was incubated with Bur1-WT or Bur1-as kinase complex (2 ng of Bur1) in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 0.5 mM ATP/N6-phenethyl-[γ-32P]ATP at RT for 40 min.

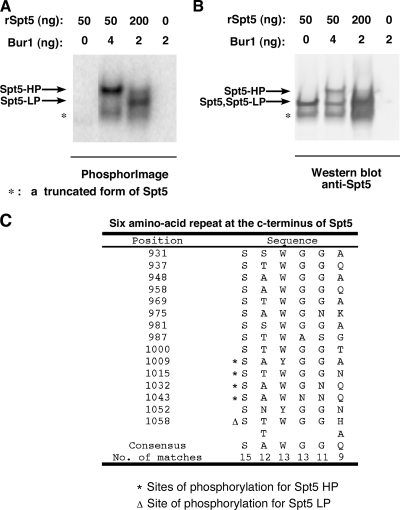

FIG. 4.

Serines in the six-amino-acid repeats at the Spt5 C terminus are identified as the phosphorylation sites by MS analysis. (A and B) Recombinant His6-Spt5 purified from E. coli was phosphorylated by Bur1 kinase under different kinase/substrate ratios in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The reactions were resolved on a 3 to 8% Tris-acetate gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Phosphorimaging and Western blotting were performed on the same membrane. The positions of Spt5-HP, Spt5-LP, Spt5, and a truncated form of Spt5 (*) are indicated. (C) Spt5-HP and Spt5-LP were prepared on a large scale, and corresponding bands were excised and subjected to MS analysis. The deduced sites of phosphorylation, the Spt5 repeats (58), and consensus sequence are indicated.

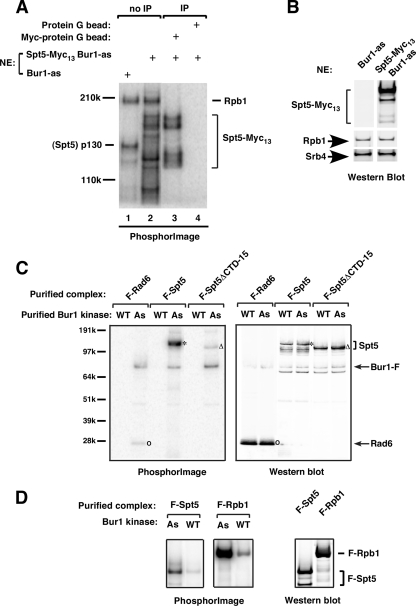

FIG. 3.

The 130-kDa Bur1 substrate is Spt5. (A) Lanes 1 and 2, EC-kinase assays were performed as described in the legend for Fig. 2 using Bur1-as or 13-Myc-Spt5 Bur1-as nuclear extracts; lanes 3 and 4, a reaction identical to that in lane 2 was immune precipitated (IP) with anti-Myc-conjugated protein G beads or protein G beads. All reactions were analyzed using a 3 to 8% Tris-acetate gel and autoradiography. The positions of Spt5, Spt5-Myc13 and degradation products (bracket), and Rpb1 are indicated. (B) Nuclear extracts (NE) made from Bur1-as or Spt5-13-Myc. Bur1-as strains were separated by a 3 to 8% Tris-acetate gel and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-Myc, 8WG16 (anti-Rpb1), and anti-Srb4 antibodies. (C) Flag-tagged Spt5, Spt5ΔCTD-15, and Rad6 complexes were purified from yeast extracts using anti-Flag M2 agarose. These complexes were used as substrates in the kinase assay using Bur1-WT (WT) or Bur1-as (As) kinase and N6-phenethyl-[γ-32P]ATP. The reactions were analyzed using a 4 to 12% NuPAGE gel. The positions of Flag-Rad6, full-length Flag-Spt5, and Flag-Spt5ΔCTD-15 are indicated with the ο, *, and Δ symbols, respectively. A Western blot of these samples probed with anti-Flag antibody is shown in the right panel. (D) Phosphorylation reactions using Bur1-as kinase as is in panel C to compare phosphorylation of Flag-Spt5 and Flag-Rpb1 purified from yeast. A Western blot of these samples is shown in the right panel.

Mass spectrometry analysis of phosphorylated Spt5.

In vitro kinase reactions producing Spt5-HP and Spt5-LP were performed on a large scale using 3 μg rSpt5. The reaction mixtures were trichloroacetic acid precipitated and resolved by a 3 to 8% Tris-acetate gel. After the gel was stained using Simplyblue Safestain (Invitrogen), the bands corresponding to Spt5-HP or Spt5-LP were cut out from the gel. The gel slices were destained and subjected to in-gel trypsin digestion (63). Extracted peptides were analyzed by microcapillary reversed-phase liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) using an LCQ DECA XP ion trap mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan). The peptides were identified by searching MS/MS spectra against a yeast protein database using the SEQUEST software program (15). To identify phosphorylated peptides, a differential modification of 80 Da on serine, threonine, and tyrosine was included in the database search. Data were analyzed using the PeptideProphet (23) and ProteinProphet (41) software programs to estimate the likelihood that each peptide and protein was correctly identified. The identification of each phosphorylated peptide was confirmed by manual inspection of the MS/MS spectra.

ChIP and real-time PCR (qPCR).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as described previously (39) with modifications. Wild-type (YL57) or spt5ΔCTD-15 (YL58) strains for H3 and H3K4-Me3 ChIPs were grown at 20°C in glucose complete medium lacking Val and Ile to an optical density (OD) of ∼0.8 and then were induced with 0.5 μg/ml sulfometuron methyl (SM) for 12 min at 20°C. Strains for Paf1-Myc and Rpb3 ChIPs were grown at 30°C and then were induced with 0.5 μg/ml SM for 30 min at 30°C. Cultures were then cross-linked for 30 min at 23°C. Cells were lysed in breaking buffer (100 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 20% glycerol) for histone and Rpb3 ChIPs and in FA buffer plus 0.1% SDS (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.6], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate) for Paf1-Myc ChIPs. Chromatin was solubilized by sonication in a Bioruptor sonicator (Diagenode) for 30 min total (30 s on/30 s off) with samples cooled on ice after 15 min. For H3 and H3K4-Me3 ChIPs, chromatin containing approximately 0.5 mg of protein was incubated overnight (O/N) at 4°C with 6 μg of the following antibodies: normal rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) for a negative control (sc-2027; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-H3 (ab1791; Abcam), or anti-H3K4-Me3 (ab8580; Abcam). For Paf1-Myc and Rpb3 ChIPs, chromatin containing approximately 1 mg of protein was incubated O/N at 4°C with 7 μg mouse anti-Myc 9E10 (Covance) or 2 μg mouse anti-Rpb3 1Y26 IgG1 (Neoclone). Twenty microliters of Dynabeads protein G (Dynal) were washed with FA buffer plus 5 mg/ml IgG-free bovine serum albumin and then added to each O/N reaction mixture and allowed to bind for 90 min at 4°C. Beads were washed as described previously (39) and eluted with 50 μl 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, and 1% SDS at 65°C for 15 min. Elutions were repeated and combined. One hundred microliters Tris-EDTA was added, cross-linking was reversed as described previously (39), and then DNA was purified using a PCR purification kit (Invitrogen) into a 50-μl final volume. One percent of the chromatin input was processed to reverse cross-links along with immunoprecipitation (IP) samples. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed as described for mRNA analysis except that 5-μl reaction volumes were used with 0.6 μl of DNA. Samples were run in triplicate, and relative amounts of DNA were calculated using a standard curve generated from serial dilutions of yeast genomic DNA using POL1 primers. Experiments were performed in at least biological duplicates. Primers were as follows: ARG1-5′ORF forward, TGGGTACCTCTTTGGCAAGACCT' ARG1-5′ORF reverse, ACAACCATGAGAGACCGCGAAACA; ARG1-3′ORF forward, CCAAGCCTTTGGATGTTTTCTT; ARG1-3′ORF reverse, ACGATCTTCTACAATATCGATTCTACCA; PYK1-5′ORF forward, TTCTTACGAATACCACAAGTCTGTCA; PYK1-5′ORF reverse, GCAATGGCCAATGGTCTACCT; PYK1-3′ORF forward, AACCTCCACCACCGAAACC; PYK1-3′ORF reverse, CCTTGGCCTTTTGTTCGAAA; PMA1-mid ORF forward, GGTGTCCCAGTCGGTTTGC; PMA1-mid ORF reverse, GGCTTGTTTCTTAGCCAAGTAAGC; POL1 forward, TTTCTGCTGAGGTGTCTTATAGAATTCA; POL1 reverse, CGTTTGGGCCCATGCAT; TELIV forward, GCGTAACAAAGCCATAATGCCTCC; and TELIV reverse, AGTAGTCCAGCCGCTTGTTAACTC.

mRNA isolation and reverse transcription-PCR.

Duplicate BUR1-as strains (YL22) were grown at 30°C in glucose complete medium lacking Val and Ile to an OD of ∼0.8. Noninduced samples were taken, and then the remaining cultures were induced with 0.5 μg/ml SM for 30 min. Cultures were then split and incubated for an additional 15 or 60 min with 6 μM MB-PP1 or the same volume of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). mRNA was isolated from 10 ml cells using a hot acidic phenol isolation procedure (3). One microgram RNA was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis to ensure equivalent quantities. RNA was DNase I treated and cDNA synthesized as described previously (4). qPCR was carried out in 15-μl reaction volumes using Power SYBR PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems), 300 nM (each) forward and reverse primers, and 1.5 μl of 1:100-diluted cDNA. The PCR program was as follows: 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C, and 40 × (15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C). Primers were as follows: ACT1 forward, TGGATTCCGGTGATGGTGTT; ACT1 reverse, TCAAAATGGCGTGAGGTAGAGA; ARG1 forward, CCAAGCCTTTGGATGTTTTCTT; ARG1 reverse, ACGATCTTCTACAATATCGATTCTACCA; PYK1 forward, AACCTCCACCACCGAAACC; PYK1 reverse, CCTTGGCCTTTTGTTCGAAA; PMA1 forward, TGATGTTGCTACTTTGGCTATTGC; PMA1 reverse, CCCATAATCTTGGTAGGTTCCATT.

Extracts and antibodies.

Yeast nuclear extracts were prepared as described previously (51). Phospho-specific antibody anti-Spt5-P was generated against phosphopeptide Ac-A(pS)(A/T)WGGA(Ahx)C-amide in rabbits by New England Peptide LLC (Gardner, MA). The monoclonal Rpb1 antibodies 8WG16, H14, and H5 were purchased from Covance Co. Anti-Spt5 antibody was a gift from Grant Hartzog. Other antibodies used in this study have been described previously (8, 35, 36).

To monitor phosphorylation states of Rpb1, yeast cells were grown in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose to an OD at 600 nm of 0.9 to 1.0 and then split into three 25-ml cultures and incubated for an additional 20 min after addition of 60 μl DMSO, 60 μl 10 mM MB-PP1 (final concentration, 24 μM), or no addition. Cells were harvested and washed with 5 ml EB (100 mM Tris [pH 7.9], 250 mM ammonium sulfate, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM DTT) plus protease and phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 μM pepstatin A, 0.6 μM leupeptin, 2 μM chymostatin, 2 mM benzamidine, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.1 mM Na3VO4), resuspended in 1 ml EB plus protease and phosphatase inhibitors, lysed in a 2-ml tube with 0.75 ml 0.5 mM zirconia/silica beads in a mini-bead beater (BioSpec Products, Inc.) for 3 min, and then chilled in ice-water for 1 min for a total of five times. Five μg of extract was loaded onto a 3 to 8% Tris-acetate gel and analyzed by Western blotting.

Rapid disruption and analysis of yeast cells.

To monitor phosphorylation states of Spt5, yeast cells were analyzed essentially as described previously (56). In brief, 10 ml cells grown in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose to an OD at 600 nm of 0.8 were collected and immediately resuspended in 550 μl SDS sample buffer (60 mM Tris [pH 6.8], 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% bromophenol blue) without any intermediate washes. The cells were vortexed for 2 s and boiled for 3 min. A ∼150-μl amount of 425- to 600-mm glass beads was added, and the mixture was vortexed for 2 min. The sample was boiled again for 2 min, spun for 5 min, loaded onto a 3 to 8% Tris-acetate gel, and analyzed by Western blotting.

RESULTS

Isolation of a transcription elongation complex.

To identify Bur1 kinase substrates in a functionally relevant complex, we first isolated the Pol II transcription elongation complex (EC). Previous studies demonstrated that elongation by mammalian RNA polymerases can be reversibly arrested by E. coli Lac repressor protein bound to a lac operator (14, 29). To arrest yeast Pol II ECs, a yeast HIS4 promoter template containing a modified lac operator site 123 bp downstream of the most 5′ transcription start site was immobilized to magnetic beads (Fig. 1A). The Lac repressor mutant R3, containing the Gcn4 dimerization domain substituted for the lac repressor tetramerization domain (9), was used to block elongation. Transcription assays were performed by adding yeast nuclear extract, the transcription activator Gal4-AH, and NTPs to the transcription template with prebound Lac R3.

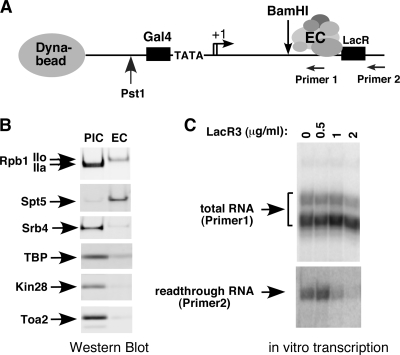

FIG. 1.

Isolation of a transcription EC on an immobilized template. (A) Diagram depicting an EC stalled by the Lac repressor on an immobilized DNA template. Sites used for restriction digestion and primers used for RNA analysis are shown. The PIC and stalled EC were formed on the immobilized DNA template and released from magnetic beads by restriction digestion. To isolate the PIC, DNA was cleaved by PstI. For isolation of the EC, transcription was initiated by NTP addition, and EC stalled by LacR was cleaved by BamHI. (B) Components of the PIC and EC were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-N-Rpb1 antibody against the N terminus of Rpb1 and antibodies against other indicated transcription factors. (C) RNA synthesis is blocked by the Lac R3 repressor. Primer extension assays were performed using nuclear extract and the immobilized template in the presence of the indicated concentrations of Lac R3. Primer 1 was used to detect total RNA and primer 2 to detect RNA that escaped the Lac R3 block.

ECs blocked the by Lac R3 protein were isolated by digestion of the DNA by BamHI, cutting within the transcribed HIS4 DNA (Fig. 1A). Alternatively, PICs were isolated by omitting NTPs from the transcription reaction and digesting the HIS4 promoter with PstI (51). To compare the composition of the EC and the PIC, both complexes were analyzed by Western blotting. Probing for Rpb1, the largest Pol II subunit, showed that the Pol II CTD is phosphorylated in the EC (IIo form) but is not phosphorylated in the PIC (IIa form) (Fig. 1B). As expected, the elongation factor Spt5 is present in the EC but is not detected in the PIC. This result is similar to the behavior of mammalian Spt5, which also binds only to elongating Pol II (6). In contrast, transcription initiation factors such as TATA-binding protein, Kin28 (TFIIH), Toa2 (TFIIA), and Srb4/Med17 (Mediator) are present in the PIC but are only weakly detected or nondetectable in the EC.

To show RNA synthesis was blocked by Lac R3, two primers were used in primer extension assays to measure RNA products (Fig. 1A and C). Primer 1 detects RNA synthesized 5′ of the lac operator, while primer 2 detects RNA synthesized by Pol II that has escaped the Lac R3 block. At 2 μg/ml repressor, synthesis of >80% of RNA is blocked by Lac R3, showing that the repressor effectively arrests the EC. Addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside and NTPs to the blocked elongation complexes revealed that about 40% of these washed complexes were competent for further mRNA synthesis (not shown).

Identification of Spt5 as Bur1 kinase substrate in the EC.

To identify Bur1 substrates in the EC, we employed a chemical genetics approach to engineer Bur1 so that it could be specifically inhibited by a small molecule and also utilize a bulky ATP analog as a substrate in vitro. This method involves mutation of a conserved bulky residue in the ATP binding pocket of the target kinase to glycine. The resulting analog-specific (as) kinase can utilize bulky ATP analogs much more efficiently than other wild-type kinases, allowing direct identification of substrates for the engineered kinase (54, 55, 59). The Bur1-as kinase was constructed by mutation of Bur1 leucine 149 to glycine. This strain had no growth phenotype, and the growth rate was also not sensitive to the two standard as-kinase inhibitors 1-NA-PP1 and 1-NM-PP1. A series of newly synthesized PP1 analogs (C. Zhang and K. M. Shokat, unpublished data) was then screened against the Bur1 L149G strain for growth inhibition using a halo assay (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), and the compound 3-MB-PP1 was found to specifically inhibit the growth of the Bur1 L149G strain (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). In vitro assays showed that 6 to 24 μM 3-MB-PP1 effectively inhibited in vitro kinase activity of the Bur1-as mutant toward a glutathione S-transferase-CTD substrate (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material) and was therefore acting directly on Bur1-as to inhibit its activity. Consistent with our results, it was recently found that 1-NM-PP1 did not inhibit growth of a BUR1-as strain unless CTK1 was also disrupted (49). This suggests that 1-NM-PP1 only partially inhibits the Bur1-as kinase in vivo.

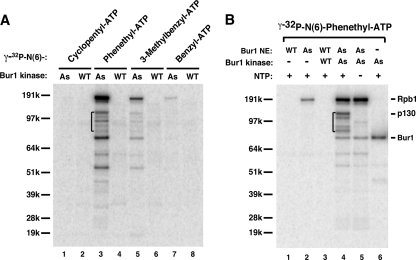

Nuclear extracts made from the BUR1-as or wild-type strain were used to form ECs on the immobilized template. Next, purified Bur1-as kinase and radiolabeled ATP analogs were incubated with the EC, and the resulting EC was isolated by BamHI digestion. The use of bulky [γ-32P]ATP analogs as kinase substrates allows identification of the as-kinase target even in the presence of other kinases, since the endogenous kinases use these analogs much less efficiently than the as kinase. Among four ATP analogs tested, N6-phenethyl-[γ-32P]ATP (2) was found to be the best substrate for Bur1-as (Fig. 2A). Several factors were specifically phosphorylated by Bur1-as but not by the Bur1-WT kinase (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

P130 and Rpb1 are specific Bur1 substrates in the EC. (A) ECs were formed on the immobilized template from wild-type nuclear extract. Kinase assays were performed by adding purified Bur1-as or Bur1-WT kinase and four different γ-32P-labeled ATP analogs. After BamHI cleavage, the released elongation complexes were loaded to a 4 to 12% NuPAGE gel and visualized by autoradiography. (B) ECs formed from Bur1-WT or Bur1-as extracts were phosphorylated by adding N6-phenethyl-[γ-32P]ATP analog with or without purified Bur1-WT or Bur1-as kinase as indicated (lanes 1 to 4). PICs formed in the absence of NTPs and Bur1 kinase alone were also used in the phosphorylation reactions as controls (lanes 5 and 6).

Western analysis revealed that Bur1 is only weakly retained in the washed EC (data not shown), indicating that the reported binding of Bur1 to the Ser-5-phosphorylated form of the Pol II CTD (49) is of modest or weak affinity. Consistent with this observation, only one low-level-phosphorylated polypeptide was observed when purified Bur1 kinase was omitted (Fig. 2B, lane 2). To increase the sensitivity of this assay, purified Bur1-as or Bur1-WT kinase was added along with N6-phenethyl-[γ-32P]ATP to the isolated EC. We observed several factors specifically phosphorylated by Bur1-as but not by Bur1-WT (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 4). Comparison of phosphorylation patterns with or without added nucleotides showed that four polypeptides in the range of 130 to 85 kDa were specifically phosphorylated in the EC (Fig. 2B, compare lanes 4 and 5, bracketed polypeptides). The slowest-migrating phosphorylated polypeptide at ∼190 kDa was identified by Western analysis as Rpb1 (data not shown) and was phosphorylated in both the PIC and the EC. Both Rpb1 and the 130-kDa factor were reproducibly and strongly phosphorylated by Bur1-as, while the three weaker polypeptides (85 to 120 kDa) have variable signals in different experiments (compare Fig. 2A, lane 3, with Fig. 2B, lane 4).

Since the elongation factor Spt5 is about 130 kDa, its recruitment to the EC is NTP dependent, and mammalian Spt5 is phosphorylated in the EC (6), we directly tested if the 130-kDa phosphorylated protein was Spt5. Nuclear extract was made from a strain containing a C-terminally 13-Myc-tagged Spt5 and used in the EC-kinase assay. The 130-kDa phosphorylated polypeptide was not observed using the Spt5-Myc13 extract (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 1 and 2) but was replaced by a series of phosphorylated products with the slowest-migrating band showing the same mobility as Spt5-Myc13 (Fig. 3B). To confirm that these products contained Myc-tagged Spt5, an identical reaction was immune precipitated with anti-Myc-conjugated protein G beads. As shown in Fig. 3A, lane 3, four phosphorylated polypeptides, but not Rpb1, were specifically precipitated with the anti-Myc beads. Consistent with these results, four polypeptides were recognized by anti-Myc antibody when the Spt5-Myc13 nuclear extract was analyzed by Western analysis (Fig. 3B). Thus, we conclude that the 130-kDa Bur1 substrate is Spt5 and the three to four faster-migrating phosphorylated polypeptides (85 to 120 kDa) are likely to be Spt5 degradation products.

We also showed that Spt5 can be efficiently phosphorylated by Bur1 in vitro when part of the Spt4/5 complex. This complex was purified from yeast extract using an N-terminal Flag tag on Spt5 and used as a substrate in a kinase assay with Bur1-as and N6-phenethyl-[γ-32P]ATP (Fig. 3C). A 130-kDa polypeptide with mobility identical to that of Spt5 was strongly phosphorylated by Bur1-as. Although Rad6 was previously reported to be a Bur1 substrate (64), Rad6 was only weakly phosphorylated by Bur1 in our kinase assay (Fig. 3C). Comparison of the phosphorylation signals and the amounts of Rad6 and Spt5 in the assay showed that Rad6 is phosphorylated about 200-fold less efficiently than Spt5 under our assay conditions (Fig. 3C, compare left and right panels). Figure 3D shows a comparison of Bur1 kinase activity at Spt5 and the Pol II CTD. Normalization of the amount of phosphorylation to the total amount of protein used in the assays (compare left and right panels) shows that the Pol II CTD is about a fourfold better substrate than Spt5.

Bur1 phosphorylates Spt5 in the C-terminal repeat domain.

To identify the sites of Spt5 phosphorylation by Bur1, we purified Spt5 from E. coli (rSpt5), carried out phosphorylation reactions, and subjected the phosphorylated Spt5 to mass spectrometry analysis. Phosphorylation of Spt5 by Bur1 gave rise to two phosphorylated forms (Fig. 4A): Spt5-HP (highly phosphorylated) or Spt5-LP (less phosphorylated), depending on the kinase/substrate ratio used in the reaction. Western analysis showed that Spt5-HP migrates more slowly than unphosphorylated Spt5, while Spt5-LP migrates similarly to unphosphorylated Spt5 (Fig. 4B). Mass spectrometry analysis identified four serines phosphorylated in Spt5-HP and one serine phosphorylated in Spt5-LP. All phosphorylated serines are located in the Spt5 C-terminal repeat domain, containing 15 copies of a six-amino-acid repeat (Fig. 4C). Due to the low number of trypsin cleavage sites in the N-terminal half of the Spt5 repeat domain, peptides corresponding to this region of the repeat were likely too large to be efficiently detected in the mass spectrometry analysis.

To verify that the Spt5 C-terminal repeat domain is the principal target of Bur1 phosphorylation, a yeast strain was constructed with the entire Spt5 C-terminal repeat domain deleted (spt5ΔCTD-15). This deletion resulted in a cold-sensitive growth defect on rich medium (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The Spt4/5 complex was purified from this strain using a Flag tag on the N terminus of Spt5 and tested as a substrate in the Bur1 kinase assay. Compared to the full-length Spt4/5 complex, phosphorylation of the Spt4/5ΔCTD-15 complex was strongly reduced, indicating that Bur1 primarily phosphorylates Spt5 at the C-terminal repeat (Fig. 3C).

Spt5 is a Bur1 kinase substrate in vivo.

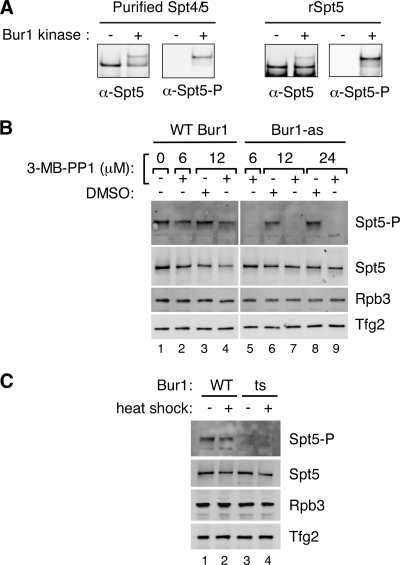

Based on the consensus sequence of the 15 six-amino-acid Spt5 repeats, a degenerate phosphopeptide was designed [A(pS)(A/T)WGGA], and this peptide was used to generate antisera specific for the phosphorylated form of the Spt5 repeats. To test the specificity of this antibody (anti-Spt5-P), in vitro-phosphorylated Spt4/5 complex or rSpt5 was analyzed by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 5A, anti-Spt5-P specifically recognizes the phosphorylated form of Spt5.

FIG. 5.

Bur1 kinase is required for phosphorylation of Spt5 in vivo. (A) Anti-Spt5-P (α-Spt5-P) antibody specifically recognizes phosphorylated Spt5. Spt5 complex purified from yeast or rSpt5 from E. coli was phosphorylated by Bur1 kinase in vitro. The reaction mixtures were loaded to a 3 to 8% Tris-acetate gel and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-Spt5 (α-Spt5) and anti-Spt5-P antibodies. (B) Bur1 phosphorylates Spt5 in vivo. Phosphorylation state of Spt5 in the BUR1-as strain treated with 3-MB-PP1 inhibitor. Exponentially growing BUR1-as cells were treated with 6, 12, or 24 μM 3-MB-PP1 or DMSO solvent (used to dissolve 3-MB-PP1) for 20 min. Cells were rapidly disrupted by boiling and vortexing with glass beads in SDS buffer (see Methods). Spt5 was detected with anti-Spt5 and anti-Spt5-P antibodies. (C) A bur1 ts mutant is defective for Spt5 phosphorylation. The wild type (WT) or a bur1 ts strain (ts; AY447) was grown at 30°C and heat shocked for 20 min. Rapid denaturing extracts were made as for panel B and proteins analyzed by Western blotting.

Using this antibody, we analyzed in vivo Spt5 phosphorylation by Western blotting. Phosphorylated Spt5 was readily observed in yeast extracts made under denaturing conditions (Fig. 5B, top panel) and migrated with the mobility of hyperphosphorylated Spt5. Spt5-P was very labile and was not observed in extracts made under native conditions even in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors (not shown). Spt5-P represented only a small fraction of total Spt5 in these denatured extracts, since Western analysis of yeast extracts using anti-Spt5 showed the bulk of Spt5 migrating at a faster mobility than Spt5-P (Fig. 5B, second panel). Addition of 3-MB-PP1 or DMSO solvent to exponentially growing wild-type strains for 20 min had little or no effect on the level of Spt5 phosphorylation. In contrast, addition of 3-MB-PP1 for 20 min to the BUR1-as strain decreased Spt5-P to undetectable levels (Fig. 5B, right panel). The levels of total Spt5 and two unrelated transcription factors were unaffected by this treatment. This rapid elimination of Spt5 phosphorylation upon Bur1 inhibition combined with the in vitro phosphorylation of Spt5 by Bur1 shows that Spt5 is a direct target of Bur1 kinase in vivo. Consistent with this conclusion, Spt5-P was not observed in extracts made from a bur1 ts strain (Fig. 5C). The fact that levels of Spt5-P are undetectable in cells grown at 30°C indicates that this bur1 ts allele is partially defective for kinase activity at the permissive temperature.

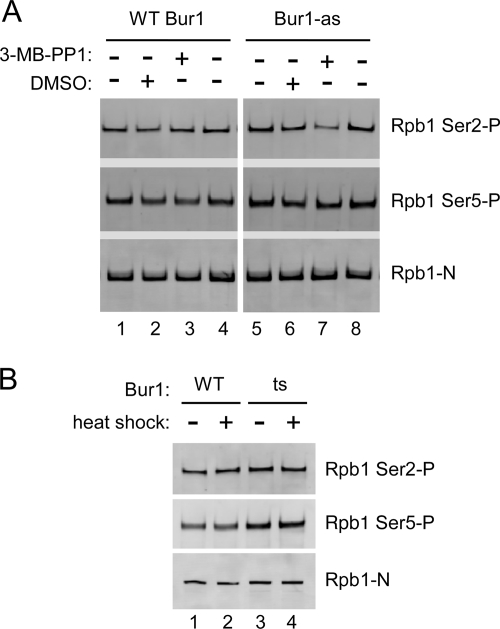

Bur1 contributes to Pol II CTD Ser-2 phosphorylation.

We found that addition of 3-MB-PP1 to the BUR1-as strain for 20 min resulted in about a 2.5-fold inhibition of Pol II CTD Ser-2 phosphorylation (Fig. 6A) and that inhibition was specific for Ser-2 phosphorylation since Ser-5 P levels were unaffected. This result is consistent with the recent results of Qiu and colleagues (49). Since rapid inactivation of Bur1 kinase activity showed a clear difference in CTD Ser-2 phosphorylation, we were surprised to find no difference in Pol II CTD Ser-2P levels in extracts made from the bur1 ts strain either before or after heat shock (Fig. 6B). Since these same cells lacked detectable Spt5-P (Fig. 5C), these findings suggest that sustained Spt5 phosphorylation requires a high level of Bur1 kinase activity, consistent with the observation that the phosphorylated form of Spt5 is very labile, whereas the Bur1-dependent phosphorylation of the Pol II CTD requires less Bur1 kinase activity.

FIG. 6.

Bur1 contributes to phosphorylation of the Pol II CTD at serine 2. (A) Twenty-four micromolar 3-MB-PP1 or DMSO solvent was added to the wild type or the BUR1-as strain for 20 min. Whole-cell extracts were made under native conditions, and phosphorylation of the Pol II CTD was analyzed by Western blotting using H5 (anti-CTD-Ser-2P), H14 (anti-CTD-Ser-5P), and anti-N-Rpb1 antibodies. (B) The Bur1 ts strain (ts; AY447) does not show a defect in Pol II CTD phosphorylation. Cells were grown as for Fig. 5C and analyzed by Western blotting. WT, wild type.

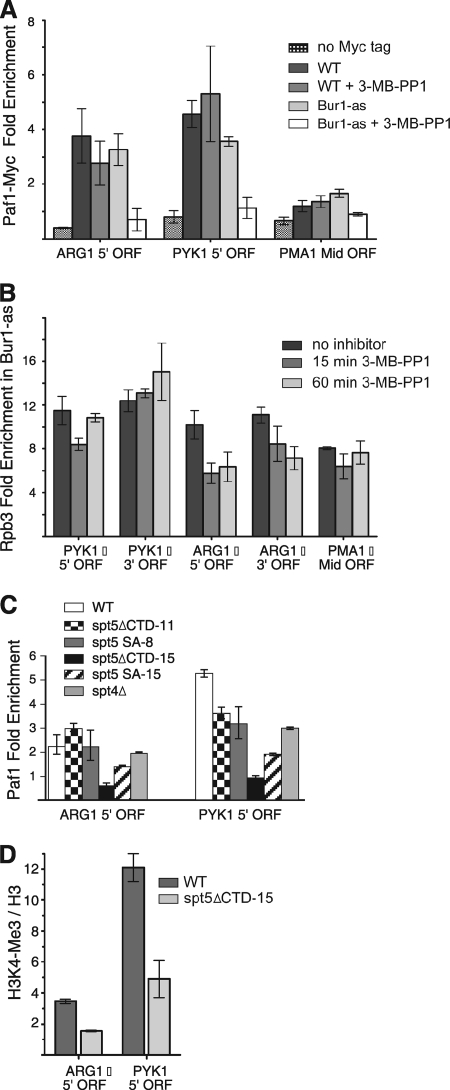

PAF recruitment requires Bur1 kinase and the Spt5 CTD.

Previous genetic results demonstrated that the Bur1 cyclin, Bur2, stimulates recruitment of the PAF complex at a step following Spt5 recruitment (31, 50). Based on these results, we asked whether PAF recruitment is stimulated by phosphorylation of the Spt5 CTD. As an initial test of this model, we determined whether rapid inhibition of Bur1 kinase activity reduced PAF cross-linking to the transcribed regions of three independently regulated genes. A wild-type strain and the BUR1-as strain were treated for 30 min with sulfometuron methyl (SM) to induce Gcn4-dependent genes, followed by a 20-min treatment with 3-MB-PP1. Cross-linking of the PAF subunit Paf1 to ARG1, PYK1, and PMA1 was assayed by ChIP (Fig. 7A). We found that inhibition of Bur1 for 20 min reduced cross-linking of Paf1 to all three transcribed regions by 1.9- to 4.7-fold, consistent with previous findings that Bur2 stimulates PAF recruitment (50).

FIG. 7.

In vivo defects upon inhibition of Bur1 kinase or mutation of the Spt5 repeat. (A) BUR1-as strains grown in synthetic complete medium lacking Ile and Val were incubated for 30 min with SM to induce Gcn4-dependent genes, followed by the addition of 6 μM 3-MB-PP1 for 20 min or the solvent DMSO. Cells were cross-linked with formaldehyde and cross-linking analyzed by ChIP. All ChIP assays were done in biological duplicate with quantitation in triplicate by qPCR. Shown is the enrichment of Paf1-Myc cross-linking relative to the chromosome IV telomere probe (TELIV). The error bars represent the standard errors of the means. WT, wild type. (B) ChIP assay for Rpb3 upon Bur1 inhibition. The BUR1-as strain was grown as described above and 3-MB-PP1 added for 15 or 60 min as indicated. Shown is the enrichment of RPB3 relative to TELIV. (C) Mutation of the Spt5 CTD reduces Paf1 cross-linking. Strains with the indicated Spt5 mutations were grown as described for panel A and assayed for Paf1 cross-linking relative to the POL1 ORF probe. (D) Mutation of the Spt5 CTD results in a methylation defect at an inducible and constitutive gene. Cells were grown as described for panel A except that cells were induced with SM for 12 min and analyzed by ChIP. Shown are the results for H3K4Me3 ChIPs normalized to total H3, displayed as the ratios of percent immunoprecipitation of H3K4Me3 to percent immunoprecipitation of total H3.

Since Bur1 was previously reported to be required for normal Pol II distribution over transcribed regions, one possibility is that the lower levels of PAF recruitment upon Bur1 inhibition were due to a general defect in transcription and/or elongation. To examine this, Pol II cross-linking to three transcribed regions was examined (Fig. 7B). While inhibition of Bur1 for 15 or 60 min resulted in a 1.7-fold reduction in Pol II cross-linking to ARG1, little or no inhibition of Pol II cross-linking was observed at either PYK1 or PMA1. One hallmark of a transcription elongation defect is lower levels of Pol II cross-linked at the 3′ end of the transcribed region compared to those the 5′ end (25, 38). Although cross-linking of Pol II was inhibited at ARG1, the levels of Pol II cross-linked at the 3′ end of the open reading frame (ORF) were equal to or greater than those observed at the 5′ end, a result inconsistent with an elongation defect. The above Pol II ChIP results were mirrored by mRNA measurements at these three genes, where only ARG1 showed a significant defect in transcript levels (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). From these results, we conclude that under standard growth conditions, inhibition of Bur1 kinase does not result in a general defect in transcription elongation and that a role for Bur1 in Pol II elongation, if it exists, must be gene specific or occur under other growth conditions.

We next tested whether the Spt5 CTD was involved in PAF recruitment. Strains were constructed bearing deletions of either 11 or all 15 Spt5 CTD repeats or containing Spt5 derivatives with 8 or 15 of the phosphorylated CTD serines changed to alanine. ChIP was used to quantitate the extent of Paf1 cross-linking to ARG1 and PYK1 in the Spt5 CTD mutant strains (Fig. 7C). We found that elimination of all 15 CTD repeats resulted in a 3.7- to 5.5-fold reduction in Paf1 cross-linking to ARG1 and PYK1, consistent with the model that the Spt5 CTD plays an important role in PAF recruitment. Interestingly, deletion of 11/15 Spt5 repeats resulted in a smaller, 1.5-fold defect in Paf1 cross-linking to PYK1 and no defect at ARG1, showing that only a small number of Spt5 repeats are required for near-normal PAF recruitment. Consistent with a role for Spt5 CTD phosphorylation in PAF recruitment, we found that mutation of all 15 serines in the repeats targeted for phosphorylation by Bur1 reduced Paf1 cross-linking 1.6- to 2.7-fold. However, mutation of 8/15 CTD serines had no Paf1 cross-linking defect at ARG1 and a 1.7-fold defect at PYK1, similar to the effects seen upon deletion of 11/15 repeats. At both ARG1 and PYK1, deletion or mutation of the entire Spt5 CTD showed a greater defect in Paf1 cross-linking compared to results with a strain containing spt4Δ, which was previously shown to have a partial defect in PAF recruitment (50). Thus, Spt4 plays a lesser role in regulation of Paf1 recruitment than the Spt5 CTD. Taken together, our results suggest that phosphorylation of the Spt5 repeats by Bur1 stimulates PAF recruitment and that only a fraction of Spt5 repeats are required for this activity.

Defect in H3K4 trimethylation upon deletion of the Spt5 repeat.

Since the Paf complex is required for downstream events in the elongation pathway, such as H3K4 methylation, we tested whether the defect in Paf1 recruitment observed in the spt5ΔCTD-15 strain would cause a defect in H3K4 trimethylation (Fig. 7D). Wild-type and Spt5ΔCTD-15 cells were induced for 12 min with SM, cross-linked with formaldehyde, and analyzed by ChIP for levels of cross-linked trimethylated H3K4 relative to total H3. At the ARG1 gene, we observed a 2.2-fold decrease in the ratio of H3K4 trimethyl/total H3 in the mutant cells compared to that in wild-type cells. Comparison of the H3K4 trimethylation ratio at PYK1 in wild-type and spt5ΔCTD-15 cells showed a 2.5-fold decrease in the mutant cells. Complete deletion of the PAF1 gene has been shown to reduce H3K4 trimethylation to nearly undetectable levels (28, 42, 65). However, since the spt5ΔCTD-15 mutation results in a four- to fivefold decrease in Paf1 recruitment, it is expected that some level of H3K4 trimethylation should still be observed since this is a relatively stable mark that can be generated though multiple rounds of transcription. Our observation of a 2- to 2.5-fold decrease in methylation observed in the spt5ΔCTD-15 strain is completely consistent with a partial defect in PAF recruitment.

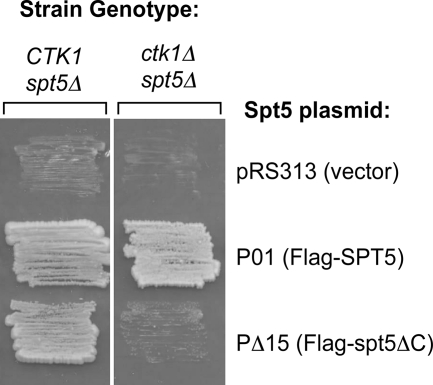

An essential function of Bur1 kinase.

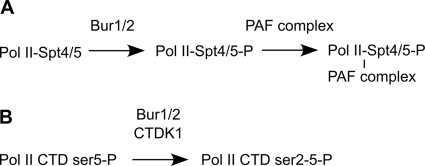

An important question is why Bur1 is essential while the related kinase Ctk1 is not. Our work above has shown that Bur1 has at least two specific targets, the C-terminal repeats of Spt5 and the Rpb1 CTD, and it was previously reported that Bur1 phosphorylated Rad6 (64). However, we showed above that deletion of the Spt5 repeat is not lethal but results in a cold-sensitive phenotype, while a comparable decrease in Ser-2P levels by deletion of CTK1 is also not lethal (12). A possible explanation for the essential role of Bur1 is that the kinase has multiple targets, none of which is essential by itself. For example, the lack of Spt5 phosphorylation and reduced Pol II Ser-2P levels could combine to give a lethal phenotype, similar to what is observed in the phenomenon of synthetic lethality caused by mutations in two genes functioning in two interacting pathways. To test this hypothesis, a strain was created which lacked Spt5 phosphorylation due to deletion of the Spt5 repeat and had reduced levels of Pol II CTD phosphorylation caused by the deletion of the CTK1 kinase gene. As predicted by our model, this genetic combination is lethal (Fig. 8), further supporting the hypothesis that Bur1 is essential because it has multiple phosphorylation targets that play important but distinct roles in transcription elongation (Fig. 9) .

FIG. 8.

Mutation of the Spt5 CTD is synthetically lethal with deletion of CTK1. Strain YL21 (spt5Δ) or LHY327 (spt5Δ Δctk1), each containing a URA3 marked SPT5 plasmid, was transformed with the indicated HIS3-marked SPT5 plasmid or empty vector. The wild-type SPT5-containing URA3 plasmid was selected against by plasmid shuffle assay on 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) plates, and the HIS3-marked SPT5 mutant or wild-type plasmid was tested for the ability to support viability of cells on 5-FOA.

FIG. 9.

Bur1 kinase functions in two parallel pathways. (A) Bur phosphorylation of the Spt5 CTD stimulates recruitment of the PAF complex to elongating Pol II, which leads to increased H3K4 methylation. (B) Bur1 and CTK1 kinases both contribute to phosphorylation of the Pol II CTD.

DISCUSSION

The S. cerevisiae CDK9-related kinase Bur1 is essential for survival and is involved in coupling of transcription elongation to chromatin modification; however, the mechanism by which this coupling is modulated has been unclear. Genetic analysis suggested that Bur1 acts to recruit the PAF complex after recruitment of Spt4/5. Bur1 was shown to phosphorylate Rad6 (64), an enzyme involved in H2B ubiquitylation; however, this factor enters the elongation complex after the PAF complex. To identify a Bur1 kinase target that could explain its more upstream role, we isolated transcription elongation complexes and used these as a substrate for Bur1. We found that both Spt5 and the CTD of Rpb1, the largest Pol II subunit, were specific and efficient in vitro Bur1 substrates.

In previous work using purified proteins, Spt5 was shown to be an in vitro substrate for the four cyclin-dependent kinases involved in transcription (Kin28, Srb10, Ctk1, and Bur1), with all kinases showing about equal phosphorylation of Spt5 (25). However, during the transcription cycle, Spt5 is not colocalized with Kin28 and Srb10, since these kinases are found only in the PIC, where Bur1 is not present. In additional experiments similar to those reported here, we found that Ctk1 did not phosphorylate Spt5 in the isolated EC (Y. Liu and S. Hahn, data not shown). Therefore, under in vitro transcription conditions, Spt5 appears to be specifically phosphorylated by Bur1.

Mass spectrometry analysis of Bur1-phosphorylated Spt5 identified the sites of Spt5 phosphorylation to multiple positions within the Spt5 C-terminal repeat domain. Using an antiserum specific for the phosphorylated consensus Spt5 repeat, we showed that the Spt5 repeat is phosphorylated by Bur1 in vivo. First, a chemical genetics strategy was used in which Bur1 was engineered to be inhibited by the drug 3-MB-PP1. We found that brief drug treatment of strains containing this altered Bur1 allele eliminated detectable Spt5 phosphorylation. In a complementary approach, we found that a strain containing a temperature-sensitive mutation in Bur1 had undetectable levels of Spt5 phosphorylation even at the permissive temperature.

In the human transcription system, where the function of Spt4/5 may not be exactly conserved with budding yeast, Spt5 has long been known to be a substrate for the CDK9-cyclin T (p-TEFb) (19, 26, 44, 46). Spt5 from humans and that from budding yeast both have a C-terminal repeat domain, sharing no sequence similarity. Human p-TEFb targets the repeat domain in human Spt5, and it has been shown that this phosphorylation is involved in switching the Spt4/5 complex (also termed DSIF) from a factor that inhibits elongation to a factor that promotes elongation, although the mechanism of how phosphorylated Spt5 promotes elongation is not known (67). This negative role of Spt4/5 has not been observed in yeast, where Spt4/5 seems to have only a positive function.

To determine the positive role for yeast Spt5 phosphorylation, we examined recruitment of the PAF complex before and after drug inhibition of the analog-sensitive Bur1 kinase. We found that recruitment of Paf1 was rapidly reduced by two- to fivefold upon inhibition of Bur1 kinase activity. This result is in agreement with previous genetic analysis which demonstrated that deletion of Bur2 (the cyclin partner of Bur1) reduced cross-linking of Paf1 to ORFs but had no effect on the recruitment of Spt4/5. Consistent with phosphorylation of Spt5 being important for PAF recruitment, deletion of the entire Spt5 C-terminal repeat or mutation of the serines phosphorylated in the Spt5 CTD reduced Paf1 cross-linking in transcribed regions of ARG1 and PYK1. Complete deletion of the Spt5 CTD showed a stronger defect in PAF recruitment than mutation of all 15 phosphorylated serines. This suggests that phosphorylation enhances the function of the Spt5 CTD repeat in PAF recruitment but is not absolutely required for function.

The defect in PAF recruitment in the spt5ΔCTD-15 strain led to a 2.2- to 2.5-fold decrease in the ratio of H3K4 trimethyl/total H3 at both a constitutive and an inducible gene. Although it is known that complete elimination of Paf1 activity results in very low levels of H3K4 trimethylation, the two- to fivefold defect in Paf1 recruitment observed upon mutation of the Spt5 CTD leads to a partial methylation defect. Therefore, the Spt5 CTD and Spt5 phosphorylation stimulates but is not essential for methylation. We did not examine methylation defects at short times after Bur1-as inhibition, since H3K4 methylation is a relatively stable mark. These results are in agreement with a recent report by Zhou and coworkers, who also found Bur1-dependent Spt5 phosphorylation and Paf complex recruitment (68).

Although it is clear from our results that Bur1 phosphorylation of Spt5 enhances recruitment of the PAF complex, the mechanism for PAF recruitment is not yet known. One simple model is that the phosphorylated Spt5 C-terminal repeat domain interacts directly with the PAF complex. However, we have found that in vitro interaction between Spt4/5 and PAF is not enhanced by Spt4/5 phosphorylation (data not shown). Another possibility is that phosphorylated Spt4/5 acts indirectly through Pol II to promote binding of PAF to the elongating Pol II. Pol II and PAF are known to interact in vitro, and the affinity of this interaction may be influenced by phosphorylated Spt5.

Surprisingly, we also found that Bur1 contributes to phosphorylation of the Pol II CTD during elongation. First, we found that the CTD is an efficient substrate for Bur1 in the isolated elongation complex. Using purified proteins, Pol II is phosphorylated by Bur1 about fourfold more than an equivalent amount of Spt5. However, the Pol II CTD contains about twice as many repeats as Spt5, so assuming all repeats are phosphorylated equivalently, the Pol II repeats are about twice as good a substrate as the Spt5 repeats under our in vitro conditions. Second, 3-MB-PP1 treatment of cells containing the analog-sensitive Bur1 allele was associated with a rapid and specific decrease in the level of Ser-2-phosphorylated CTD. This result agrees with the recent findings of Qiu and colleagues that Bur1 phosphorylates the Pol II CTD at Ser-2 primarily at the 5′ ends of coding sequences (49).

Another surprising finding was that inhibition of Bur1 kinase activity did not lead to a general defect in transcription elongation. It was previously reported that heat shock of a bur1 ts strain led to a lower level of Pol II cross-linked at the 3′ end of PMA1 than to the 5′ end, leading to the conclusion that Bur1 plays a role in Pol II elongation (25). This experiment was complicated by the fact that heat shock of this strain led to a decrease in the total amount of Pol II cross-linked to PMA1. In our new experiments, rapid shutoff of Bur1 kinase using 3-MB-PP1 showed no significant change in Pol II cross-linking at PYK1 or PMA1 and a twofold decrease in cross-linking at ARG1. These cross-linking studies were corroborated by mRNA analysis. Despite the decrease in ARG1 transcription, Pol II cross-linking was similar or higher at the 3′ end of the ARG1 ORF, a result not consistent with a defect in elongation. Thus, we conclude that under standard growth conditions, Bur1 does not play a general role in Pol II elongation, while it does have a key role in elongation-coupled chromatin modification. Zhou et al. (68) recently reported that deletion of the Spt5 CTD resulted in a ∼3-fold decrease in Pol II cross-linking across the entire PMA1 gene when cells were treated with 6-azauracil; however, these conditions did not cause a buildup of Pol II at the 5′ end of the coding sequence, so it is not clear why transcription was generally more sensitive to 6-azauracil in the Spt5 mutant.

Our results combined with previous genetic data suggest that Spt4/5 has another essential role in addition to recruitment of the PAF complex. It has been found that lethality of a Bur1 mutation can be suppressed by mutations in downstream elongation factors involved in chromatin modification and recruitment of the Rpd3s deacetylase complex (13, 24, 27). However, it was also found that mutation of Spt5 could not suppress the effect of a Bur1 deletion, suggesting that Spt5 plays an important role in addition to its function in Paf1 recruitment. One possibility for this essential role is the function of Spt4/5 in Pol II processivity. It was found that deletion of Spt4 was one of the few mutations in “elongation factors” that reduced the processivity of Pol II (38). Thus, Spt4/5 likely has a direct role in Pol II elongation in addition to its role in recruitment of factors involved in chromatin modification and mRNA maturation. Using the tools developed here, it should be possible to genetically separate these two functions to clarify the additional role(s) of Spt4/5.

Finally, our genetic results suggest a model for the requirement of Bur1 for yeast viability (Fig. 8). Neither deletion of the Spt5 C-terminal repeats or reduction in Pol II CTD Ser-2P is lethal. In contrast, we found that combining these two mutations was lethal. This result suggests that Bur1 is essential because it targets multiple factors for phosphorylation that play important but distinct roles in transcription. Our results, however, do not rule out the existence of other important targets of Bur1. A synthetic lethal screen using the spt5ΔCTD allele may reveal the identities of other important Bur1 targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Scott Lewis (New England Peptide) for design of the degenerate Spt5 phosphopeptide, Bruce Knutson for assistance with qPCR, ChIP assays, and primer design, Charles Kung for the original Bur1-as strain, Greg Prelich for the Bur1 ts strain, and Grant Hartzog for Spt5 antisera. We also thank members of the Hahn laboratory and Ted Young for comments and suggestions throughout the course of this work.

This work was supported by grant no. 5RO1GM53451 to S.H., grant NIH T32 CA09657 to Y.L., NIGMS grant PM50 GMO76547/Center for Systems Biology to J.R., and grant no. 2R01EB001987 to K.M.S.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 July 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, S. H., M. Kim, and S. Buratowski. 2004. Phosphorylation of serine 2 within the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain couples transcription and 3′ end processing. Mol. Cell 1367-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen, J. J., M. Li, C. S. Brinkworth, J. L. Paulson, D. Wang, A. Hubner, W. H. Chou, R. J. Davis, A. L. Burlingame, R. O. Messing, C. D. Katayama, S. M. Hedrick, and K. M. Shokat. 2007. A semisynthetic epitope for kinase substrates. Nat. Methods 4511-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel, F., R. Brent, R. Kingston, D. Moore, J. Seidman, J. R. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1998. Current protocols in molecular biology, vol. 13, p. 13.12.11-13/12/12. Greene/Wiley Interscience, Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biddick, R. K., G. L. Law, and E. T. Young. 2008. Adr1 and Cat8 mediate coactivator recruitment and chromatin remodeling at glucose-regulated genes. PLoS ONE 3e1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blethrow, J., C. Zhang, K. M. Shokat, and E. L. Weiss. 2004. Design and use of analog-sensitive protein kinases. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. Chapter 18Unit 18.11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Bourgeois, C. F., Y. K. Kim, M. J. Churcher, M. J. West, and J. Karn. 2002. Spt5 cooperates with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat by preventing premature RNA release at terminator sequences. Mol. Cell. Biol. 221079-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrozza, M. J., B. Li, L. Florens, T. Suganuma, S. K. Swanson, K. K. Lee, W. J. Shia, S. Anderson, J. Yates, M. P. Washburn, and J. L. Workman. 2005. Histone H3 methylation by Set2 directs deacetylation of coding regions by Rpd3S to suppress spurious intragenic transcription. Cell 123581-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, H.-T., and S. Hahn. 2004. Mapping the location of TFIIB within the RNA polymerase II transcription preinitiation complex: a model for the structure of the PIC. Cell 119169-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, J., S. Alberti, and K. S. Matthews. 1994. Wild-type operator binding and altered cooperativity for inducer binding of lac repressor dimer mutant R3. J. Biol. Chem. 26912482-12487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, J., and K. S. Matthews. 1992. Deletion of lactose repressor carboxyl-terminal domain affects tetramer formation. J. Biol. Chem. 26713843-13850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chi, Y., M. J. Huddleston, X. Zhang, R. A. Young, R. S. Annan, S. A. Carr, and R. J. Deshaies. 2001. Negative regulation of Gcn4 and Msn2 transcription factors by Srb10 cyclin-dependent kinase. Genes Dev. 151078-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho, E. J., M. S. Kobor, M. Kim, J. Greenblatt, and S. Buratowski. 2001. Opposing effects of Ctk1 kinase and Fcp1 phosphatase at Ser 2 of the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain. Genes Dev. 153319-3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu, Y., A. Sutton, R. Sternglanz, and G. Prelich. 2006. The BUR1 cyclin-dependent protein kinase is required for the normal pattern of histone methylation by SET2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 263029-3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deuschle, U., R. A. Hipskind, and H. Bujard. 1990. RNA polymerase II transcription blocked by Escherichia coli lac repressor. Science 248480-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eng, J. K., A. L. McCormack, and J. R. R. Yates. 1994. An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 5976-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartzog, G. A., T. Wada, H. Handa, and F. Winston. 1998. Evidence that Spt4, 5, and 6 control transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II in S. cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 12357-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hengartner, C. J., V. E. Myer, S. M. Liao, C. J. Wilson, S. S. Koh, and R. A. Young. 1998. Temporal regulation of RNA polymerase II by Srb10 and Kin28 cyclin-dependent kinases. Mol. Cell 243-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirst, M., M. S. Kobor, N. Kuriakose, J. Greenblatt, and I. Sadowski. 1999. GAL4 is regulated by the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme-associated cyclin-dependent protein kinase SRB10/CDK8. Mol. Cell 3673-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ivanov, D., Y. T. Kwak, J. Guo, and R. B. Gaynor. 2000. Domains in the SPT5 protein that modulate its transcriptional regulatory properties. Mol. Cell. Biol. 202970-2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones, J. C., H. P. Phatnani, T. A. Haystead, J. A. MacDonald, S. M. Alam, and A. L. Greenleaf. 2004. C-terminal repeat domain kinase I phosphorylates Ser2 and Ser5 of RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 27924957-24964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joshi, A. A., and K. Struhl. 2005. Eaf3 chromodomain interaction with methylated H3-K36 links histone deacetylation to Pol II elongation. Mol. Cell 20971-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanin, E. I., R. T. Kipp, C. Kung, M. Slattery, A. Viale, S. Hahn, K. M. Shokat, and A. Z. Ansari. 2007. Chemical inhibition of the TFIIH-associated kinase Cdk7/Kin28 does not impair global mRNA synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1045812-5817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keller, A., A. I. Nesvizhskii, E. Kolker, and R. Aebersold. 2002. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal. Chem. 745383-5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keogh, M. C., S. K. Kurdistani, S. A. Morris, S. H. Ahn, V. Podolny, S. R. Collins, M. Schuldiner, K. Chin, T. Punna, N. J. Thompson, C. Boone, A. Emili, J. S. Weissman, T. R. Hughes, B. D. Strahl, M. Grunstein, J. F. Greenblatt, S. Buratowski, and N. J. Krogan. 2005. Cotranscriptional set2 methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 recruits a repressive Rpd3 complex. Cell 123593-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keogh, M. C., V. Podolny, and S. Buratowski. 2003. Bur1 kinase is required for efficient transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 237005-7018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim, J. B., and P. A. Sharp. 2001. Positive transcription elongation factor B phosphorylates hSPT5 and RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal domain independently of cyclin-dependent kinase-activating kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 27612317-12323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim, T., and S. Buratowski. 2007. Two Saccharomyces cerevisiae JmjC domain proteins demethylate histone H3 Lys36 in transcribed regions to promote elongation. J. Biol. Chem. 28220827-20835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krogan, N. J., J. Dover, A. Wood, J. Schneider, J. Heidt, M. A. Boateng, K. Dean, O. W. Ryan, A. Golshani, M. Johnston, J. F. Greenblatt, and A. Shilatifard. 2003. The Paf1 complex is required for histone H3 methylation by COMPASS and Dot1p: linking transcriptional elongation to histone methylation. Mol. Cell 11721-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuhn, A., I. Bartsch, and I. Grummt. 1990. Specific interaction of the murine transcription termination factor TTF I with class-I RNA polymerases. Nature 344559-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laribee, R. N., S. M. Fuchs, and B. D. Strahl. 2007. H2B ubiquitylation in transcriptional control: a FACT-finding mission. Genes Dev. 21737-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laribee, R. N., N. J. Krogan, T. Xiao, Y. Shibata, T. R. Hughes, J. F. Greenblatt, and B. D. Strahl. 2005. BUR kinase selectively regulates H3 K4 trimethylation and H2B ubiquitylation through recruitment of the PAF elongation complex. Curr. Biol. 151487-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, B., M. Carey, and J. L. Workman. 2007. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell 128707-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindstrom, D. L., and G. A. Hartzog. 2001. Genetic interactions of Spt4-Spt5 and TFIIS with the RNA polymerase II CTD and CTD modifying enzymes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 159487-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindstrom, D. L., S. L. Squazzo, N. Muster, T. A. Burckin, K. C. Wachter, C. A. Emigh, J. A. McCleery, J. R. Yates III, and G. A. Hartzog. 2003. Dual roles for Spt5 in pre-mRNA processing and transcription elongation revealed by identification of Spt5-associated proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 231368-1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu, Y., C. Kung, J. Fishburn, A. Z. Ansari, K. M. Shokat, and S. Hahn. 2004. Two cyclin-dependent kinases promote RNA polymerase II transcription and formation of the Scaffold Complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 241721-1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, Y., J. A. Ranish, R. Aebersold, and S. Hahn. 2001. Yeast nuclear extract contains two major forms of RNA polymerase II mediator complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2767169-7175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mason, P. B., and K. Struhl. 2005. Distinction and relationship between elongation rate and processivity of RNA polymerase II in vivo. Mol. Cell 17831-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McConnell, A. D., M. E. Gelbart, and T. Tsukiyama. 2004. Histone fold protein Dls1p is required for Isw2-dependent chromatin remodeling in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 242605-2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nelson, C., S. Goto, K. Lund, W. Hung, and I. Sadowski. 2003. Srb10/Cdk8 regulates yeast filamentous growth by phosphorylating the transcription factor Ste12. Nature 421187-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nesvizhskii, A. I., A. Keller, E. Kolker, and R. Aebersold. 2003. A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 754646-4658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ng, H. H., F. Robert, R. A. Young, and K. Struhl. 2003. Targeted recruitment of Set1 histone methylase by elongating Pol II provides a localized mark and memory of recent transcriptional activity. Mol. Cell 11709-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pavri, R., B. Zhu, G. Li, P. Trojer, S. Mandal, A. Shilatifard, and D. Reinberg. 2006. Histone H2B monoubiquitination functions cooperatively with FACT to regulate elongation by RNA polymerase II. Cell 125703-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pei, Y., and S. Shuman. 2003. Characterization of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe Cdk9/Pch1 protein kinase: Spt5 phosphorylation, autophosphorylation, and mutational analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 27843346-43356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pei, Y., and S. Shuman. 2002. Interactions between fission yeast mRNA capping enzymes and elongation factor Spt5. J. Biol. Chem. 27719639-19648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ping, Y. H., and T. M. Rana. 2001. DSIF and NELF interact with RNA polymerase II elongation complex and HIV-1 Tat stimulates P-TEFb-mediated phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II and DSIF during transcription elongation. J. Biol. Chem. 27612951-12958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prather, D. M., E. Larschan, and F. Winston. 2005. Evidence that the elongation factor TFIIS plays a role in transcription initiation at GAL1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 252650-2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prelich, G. 2002. RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain kinases: emerging clues to their function. Eukaryot. Cell 1153-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qiu, H., C. Hu, and A. G. Hinnebusch. 2009. Phosphorylation of the Pol II CTD by KIN28 enhances BUR1/BUR2 recruitment and Ser2 CTD phosphorylation near promoters. Mol. Cell 33752-762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qiu, H., C. Hu, C. M. Wong, and A. G. Hinnebusch. 2006. The Spt4p subunit of yeast DSIF stimulates association of the Paf1 complex with elongating RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 263135-3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ranish, J. A., N. Yudkovsky, and S. Hahn. 1999. Intermediates in formation and activity of the RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex: holoenzyme recruitment and a postrecruitment role for the TATA box and TFIIB. Genes Dev. 1349-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodriguez, C. R., E. J. Cho, M. C. Keogh, C. L. Moore, A. L. Greenleaf, and S. Buratowski. 2000. Kin28, the TFIIH-associated carboxy-terminal domain kinase, facilitates the recruitment of mRNA processing machinery to RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20104-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saunders, A., L. J. Core, and J. T. Lis. 2006. Breaking barriers to transcription elongation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7557-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shah, K., Y. Liu, C. Deirmengian, and K. M. Shokat. 1997. Engineering unnatural nucleotide specificity for Rous sarcoma virus tyrosine kinase to uniquely label its direct substrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 943565-3570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shah, K., and K. M. Shokat. 2002. A chemical genetic screen for direct v-Src substrates reveals ordered assembly of a retrograde signaling pathway. Chem. Biol. 935-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shou, W., J. H. Seol, A. Shevchenko, C. Baskerville, D. Moazed, Z. W. Chen, J. Jang, H. Charbonneau, and R. J. Deshaies. 1999. Exit from mitosis is triggered by Tem1-dependent release of the protein phosphatase Cdc14 from nucleolar RENT complex. Cell 97233-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sims, R. J., III, R. Belotserkovskaya, and D. Reinberg. 2004. Elongation by RNA polymerase II: the short and long of it. Genes Dev. 182437-2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swanson, M. S., E. A. Malone, and F. Winston. 1991. SPT5, an essential gene important for normal transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, encodes an acidic nuclear protein with a carboxy-terminal repeat. Mol. Cell. Biol. 113009-3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ubersax, J. A., E. L. Woodbury, P. N. Quang, M. Paraz, J. D. Blethrow, K. Shah, K. M. Shokat, and D. O. Morgan. 2003. Targets of the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk1. Nature 425859-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wach, A., A. Brachat, R. Pohlmann, and P. Philippsen. 1994. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 101793-1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wada, T., T. Takagi, Y. Yamaguchi, A. Ferdous, T. Imai, S. Hirose, S. Sugimoto, K. Yano, G. A. Hartzog, F. Winston, S. Buratowski, and H. Handa. 1998. DSIF, a novel transcription elongation factor that regulates RNA polymerase II processivity is composed of human Spt4 and Spt5 homologs. Genes Dev. 12343-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wen, Y., and A. J. Shatkin. 1999. Transcription elongation factor hSPT5 stimulates mRNA capping. Genes Dev. 131774-1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilm, M., A. Shevchenko, T. Houthaeve, S. Breit, L. Schweigerer, T. Fotsis, and M. Mann. 1996. Femtomole sequencing of proteins from polyacrylamide gels by nano-electrospray mass spectrometry. Nature 379466-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wood, A., J. Schneider, J. Dover, M. Johnston, and A. Shilatifard. 2005. The Bur1/Bur2 complex is required for histone H2B monoubiquitination by Rad6/Bre1 and histone methylation by COMPASS. Mol. Cell 20589-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wood, A., J. Schneider, J. Dover, M. Johnston, and A. Shilatifard. 2003. The Paf1 complex is essential for histone monoubiquitination by the Rad6-Bre1 complex, which signals for histone methylation by COMPASS and Dot1p. J. Biol. Chem. 27834739-34742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xiao, T., Y. Shibata, B. Rao, R. N. Laribee, R. O'Rourke, M. J. Buck, J. F. Greenblatt, N. J. Krogan, J. D. Lieb, and B. D. Strahl. 2007. The RNA polymerase II kinase Ctk1 regulates positioning of a 5′ histone methylation boundary along genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27721-731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamada, T., Y. Yamaguchi, N. Inukai, S. Okamoto, T. Mura, and H. Handa. 2006. P-TEFb-mediated phosphorylation of hSpt5 C-terminal repeats is critical for processive transcription elongation. Mol. Cell 21227-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou, K., W. H. Kuo, J. Fillingham, and J. F. Greenblatt. 2009. Control of transcriptional elongation and cotranscriptional histone modification by the yeast BUR kinase substrate Spt5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1066956-6961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.