Abstract

This computational study analyzes how to design a drainage system for porous scaffolds so that the scaffolds can be vascularized and perfused without collapse of the vessel lumens. We postulate that vascular transmural pressure—the difference between lumenal and interstitial pressures—must exceed a threshold value to avoid collapse. Model geometries consisted of hexagonal arrays of open channels in an isotropic scaffold, in which a small subset of channels was selected for drainage. Fluid flow through the vessels and drainage channel, across the vascular wall, and through the scaffold were governed by Navier-Stokes equations, Starling’s Law of Filtration, and Darcy’s Law, respectively. We found that each drainage channel could maintain a threshold transmural pressure only in nearby vessels, with a radius-of-action dependent on vascular geometry and the hydraulic properties of the vascular wall and scaffold. We illustrate how these results can be applied to microvascular tissue engineering, and suggest that scaffolds be designed with both perfusion and drainage in mind.

Keywords: microvascular tissue engineering, drainage, collapse, scaffold, perfusion, computational model

1. Introduction

Numerous materials have been developed to promote the formation of vascularized tissues in vitro and in vivo [1–3]. In many studies, these materials consisted of uniformly porous scaffolds (e.g., hydrogels, degradable polymer meshes) that contained vascular growth factors and/or cells [4–8]. More recently, scaffolds with pre-formed channels made by microlithography or other patterning techniques have been created, in the hope that pre-vascularizing these channels would accelerate perfusion upon transplantation in vivo [9–12]. The ability of scaffolds to yield a sufficiently large density of perfused vessels is often the primary concern, and many computational studies have attempted to design scaffolds with appropriate densities of channels to sustain a desired tissue metabolic rate [12–14]. In this work, we analyze the complementary issue of tissue drainage, specifically for scaffolds with pre-vascularized channels.

Why is drainage relevant? In vertebrates, nearly all organs contain specialized vessels—the lymphatics—to remove excess fluid, solutes, and cells that are transported across permeable blood vessel walls [15]. If fluid filters across blood vessels at a higher rate than the rate of drainage into lymphatics, then interstitial fluid accumulates and interstitial pressures rise [16, 17]. Increased interstitial fluid pressure, if not mirrored by increases in blood pressure, will lead to decreased transmural pressure (lumenal pressure minus interstitial pressure) across vascular walls, thereby lowering vascular diameter and hindering perfusion [18]. In particular, transmural pressure must remain above a certain threshold (the so-called “closing pressure”) to avoid vascular collapse [19–21]. Published values of closing pressures range from −5 to 25 cm H2O [20–23]; in general, the greater the vascular tone, the greater the threshold value [22, 23]. Vascular constriction or collapse is thought to play a crucial role in pathological conditions where external compression of tissue greatly reduces blood flow, such as compartment syndrome [24–26].

We expect engineered tissues to be subject to the same constraints and possibly to be even more vulnerable to insufficient drainage. The highly cross-linked nature of many scaffolds implies that it is difficult for scaffolds to swell sufficiently to accommodate excess fluids. Moreover, engineered vessels can be more immature and permeable compared to native blood vessels [10]. As a first step towards understanding how to design drainage systems for engineered tissues, we used computational modeling to determine how the physical properties of a scaffold, and the organization of vessels contained within, influence the ability of the scaffold to be drained. We analyzed how drainage capacity affects pressure balance within a scaffold, and show that low densities of drainage channels can potentially lead to collapse of surrounding vessels.

In this study, we postulate that a minimum transmural pressure (analogous to the closing pressure in vivo) is required to maintain vascular patency. We show that—in the absence of drainage—all vascular networks will contain at least some vessel segments under negative transmural pressure at steady state. Under these conditions, it is likely that transmural pressures will fall below the minimum level required to avoid collapse and loss of perfusion. Thus, whether an engineered scaffold can be functionally perfused may depend not only on the total vascular density, but also on whether the scaffold has enough drainage channels to maintain vascular patency via a low interstitial pressure.

This study evaluates several candidate drainage systems, and determines which combination of scaffold properties and vascular geometries can maintain a given transmural pressure in all vessels. It extends the existing body of work in numerical and/or analytical investigations of microvascular fluid mechanics, which have predicted fluid flow and pressure within and immediately around capillaries, but which have not typically emphasized the role of drainage in determining flow and pressure [27–31]. Our study hypothesizes that the geometric relationship between the areas for filtration and drainage, and the hydraulic properties of the scaffold and endothelial walls, play complementary roles in regulating vascular transmural pressure.

The models considered here consist of arrays of parallel vessels, similar to those proposed by August Krogh in his model of oxygen transport [32]. In contrast to the standard Krogh model (in which all vessels are designated for perfusion), here we selected a subset for drainage. Given the potential similarity of our models to the Krogh model of capillary perfusion, we examined whether the concept of a radius-of-action or “Krogh radius”, which has greatly simplified the design of microvascular systems for perfusion [33, 34], could also be applied to the design of drainage systems.

2. Theory and Numerical Methods

2.1. Terminology

We modeled pressures and flows in a slab of tissue comprised of a regular hexagonal array of perfusion vessels and drainage channels in a porous scaffold (Fig. 1). Here, “vessel” refers to a structure that contains an endothelial layer. “Channels” are barren and lack an endothelium. We do not refer to drainage channels as “lymphatics” to avoid confusion over the mechanism of drainage: In contrast to actual lymphatics in vivo [35], here the drainage channels are not endothelialized and are passively drained.

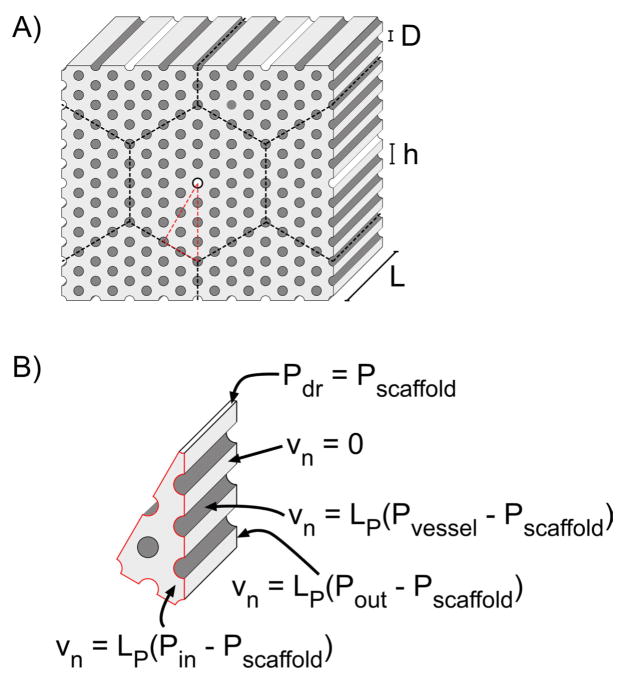

Figure 1.

Representative geometries of the tissue slab and computational domain, for the case of N = 4. A) Front and back faces of the tissue slab are separated by a distance L. Vessels of diameter D form a hexagonal lattice of spacing h. Cylinders with white and dark grey walls represent drainage channels and vessels, respectively. Dashed black lines denote planes of symmetry. Dashed red lines outline the actual computational domain. B) Boundary conditions on the scaffold and their regions of applicability.

2.2. Geometry of numerical model

The geometries of our models followed those described by Vunjak-Novakovic and co-workers [14]. Vessels and drainage channels were cylinders of length L and diameter D, extended from one face of the slab to the other in a direction normal to the scaffold faces, and were separated by a center-to-center lattice spacing h (Fig. 1A). They were distributed within the hexagonal array such that drainage channels were separated by a distance 2Nh, where N is a positive integer.

The symmetry of this arrangement permitted reduction of the model tissue to an equivalent triangular wedge radiating from a single drainage channel (Fig. 1B; see below for appropriate boundary conditions). The simplified tissue contained N concentric layers of vessels.

2.3. Governing equations

Fluid flow through the scaffold obeyed Darcy’s law [36]:

| (1) |

Here, vscaffold is the interstitial fluid velocity, K is the hydraulic conductivity of the scaffold, and Pscaffold is the interstitial fluid pressure. The hydraulic conductivity was assumed to be independent of Pscaffold [36–38], and we confirmed this assumption experimentally for type I collagen and alginate gels (see below).

Fluid flow through the vessels and drainage channels obeyed steady-state Navier-Stokes equations:

| (2) |

| (3) |

where vvessel and vdrain are the vascular and drainage fluid velocities, Pvessel and Pdrain are the pressures within vessels and the drainage channel, ρ is the perfusate density, and η is the perfusate viscosity. Vascular pressures decreased from an inlet pressure Pin to an outlet pressure Pout. The open ends of drainage channels were held at drainage pressure Pdr.

To describe the perfusion of a scaffold with a defined medium, we imposed Starling s Law for filtration of protein-free perfusate at the vessel walls and on the front and back faces of the slab [39]:

| (4) |

where vn is the fluid filtration velocity normal to the wall, and LP is the hydraulic conductivity of the vessel wall. Equation (4) describes a scaffold that is vascularized both within and on its surface, which we expect to be the end result when porous scaffolds are seeded with a suspension of vascular cells. Continuity of fluid velocity and pressure was imposed at the drainage channel wall, since these walls were taken to be endothelium-free. We imposed the no-flux boundary condition vn = 0 at planes of symmetry.

To test how the boundary conditions at the scaffold walls affected fluid pressures and flow, we modified our standard models in two ways: In one set of models, we imposed equation (4) at the drainage wall; these models effectively replace the drainage channel with a vessel, and are equivalent to models without drainage. In another set, we replaced equation (4) with fixed-pressure boundary conditions of Pscaffold = Pin at the front face and Pscaffold = Pout at the back face of the scaffold; these models imply that the faces of the scaffold offer no hydraulic resistance.

2.4. Parameter values

Each design was completely defined by four geometric values (N, D, h, L), two hydraulic conductivities (K, LP), three pressures (Pdr, Pin, Pout), and two materials properties (ρ, η). Table 1 shows ranges of values used in this work. Because we were interested in pressure differences across the vessel walls, we could eliminate one pressure by specifying only the perfusion pressure difference Pin − Pout and the drainage pressure difference Pout − Pdr. Vascular diameters D ranged from 30 to 200 μm, which approximates the diameters of cylindrical tubes currently achievable using micromolded or laser-etched scaffolds [10, 14, 40]. Values for L and h were chosen to yield physiologically relevant microvascular aspect ratios [41]. Values for Pin − Pout approximated pressure drops across microvessels in vivo [42, 43]. Values for K ranged from ~10−12 cm4/dyn·s for dense scaffolds like poly(ethylene glycol)-based gels to ~10−8 cm4/dyn·s for type I collagen gels [36, 38]. Values for LP ranged from ~10−11 to ~10−9 cm3/dyn·s for endothelium with or without a muscular wall in vitro [44–46]. The density and viscosity of perfusate were taken to be those of dilute aqueous solutions (1 g/cm3 and 0.7 cP, respectively).

Table 1.

Design parameters and their values.

| Parameter | Definition | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Geometric parameters | ||

| N | Layers of vessels per drainage channel | 1–12 |

| D | Diameter of vessels | 30–200 μm |

| h | Distance between adjacent vessels | 250–1000 μm |

| L | Thickness of scaffold | 0.5–2.0 cm |

| Hydraulic parameters | ||

| K | Scaffold hydraulic conductivity | 10−12–10−8 cm4/dyn·s |

| LP | Vascular hydraulic conductivity | 10−11–10−9 cm3/dyn·s |

| Pressures | ||

| Pin − Pout | Perfusion pressure difference | 2–40 cm H2O |

| Pout − Pdr | Drainage pressure difference | 0–30 cm H2O |

| Materials properties | ||

| ρ | Density of perfusate | 1 g/cm3 |

| η | Viscosity of perfusate | 0.7 cP |

2.5. Numerical methods

For each model, we solved equations (1)–(4) using the finite element method (COMSOL Multiphysics ver. 3.4; Comsol, Inc.) with quadratic Lagrangian elements and the PARDISO solver algorithm. Each model yielded the transmural pressure Pt ≡ Pvessel − Pscaffold along all vessel walls, and we recorded the minimum value Pt,min in the model. For each model, we demonstrated mesh independence by increasing the fineness of the mesh until a two-fold increase in numerical degrees of freedom led to a <0.05 cm H2O difference in Pt,min. Models with >106 degrees of freedom were solved on parallel-processing Linux-based workstations (Whitaker Computational Facility; Dept. of Biomedical Eng., Boston Univ.) and typically required 1–10 CPU-hrs to converge. Although equations (1)–(4) are non-linear, we did not note sensitivity of the final solutions to initial solver conditions.

3. Materials and Experimental Methods

To test whether hydraulic conductivity K was independent of Pscaffold, we measured K for collagen and alginate gels at a variety of interstitial pressures. Collagen gels were made by gelling neutralized type I collagen (10 mg/mL from rat tail; BD Biosciences) inside an open-ended silicone channel (cross-sectional area = 0.75 mm2, length = 3 mm) at 37°C. MCDB131 media was flowed through gels by applying a hydrostatic pressure difference ΔP of 2, 5, 8, or 12.5 cm H2O across their ends, while varying the average pressure in the gel between −5, 0, 5, 10, or 15 cm H2O. Media was collected from the outlet end to determine the flow rate Q through the gel, and K was calculated from the relation K = Q(3 mm)/(0.75 mm2)ΔP.

Since alginate gels are much more resistive than collagen gels are, we formed alginate gels in larger blocks (cross-sectional area = 4 cm2, thickness = 1 mm). Alginate (4%; Sigma) was gelled with 60 mM CaCl2 at room temperature for 2 hours. The alginate slab was then carefully sandwiched between two plastic rings and sealed with silicone. The hydrostatic pressure differences applied across the gels were 3, 6, 10, or 13.5 cm H2O; the average pressures in the gels were −5, 0, 5, 10, or 15 cm H2O. Hydraulic conductivity was calculated with a formula analogous to the one described above.

4. Results

Our objective was to analyze how the minimum transmural pressure Pt,min varies with the geometry of the scaffold (as described by N, D, h, and L), the hydraulic properties of the scaffold and vessel wall (K and LP), and the driving pressures for perfusion and drainage (Pin − Pout and Pout − Pdr). We first determined the basic features required to obtain positive transmural pressures, since we expected positive Pt to favor vascular patency. We then systematically examined which of the eight above variables had the greatest influence on Pt,min, and attempted to reduce the number of relevant variables where possible and justified by physical reasoning.

In all models, we assumed that K was independent of Pscaffold. To test this assumption, we measured K for type I collagen and alginate gels, two materials commonly used in tissue engineering applications [47–49]. Unlike highly heterogeneous tissues in vivo [37], these homogeneous scaffolds exhibited at best a weak dependence of K on Pscaffold, with a 1% increase per cm H2O for collagen gels (K ~ 3×10−8 cm4/dyn·s) and a 3% increase per cm H2O for alginate gels (K ~ 2×10−11 cm4/dyn·s).

4.1. Requirement for drainage and insulation of scaffold walls

Figure 2A presents cross-sectional views of interstitial and lumenal pressures in a representative tissue construct with four layers of vessels per drainage channel (i.e., N = 4). Interstitial pressure Pscaffold increased with distance from the drainage channel (i.e., downwards in Fig. 2A), but decreased with distance along the vascular axis (i.e., left to right in Fig. 2A). The axial decrease in vessel lumenal pressure Pvessel was greater than that in Pscaffold. Thus, transmural pressure Pt fell with distance from the drainage channel and with distance along the vascular axis. The combination of these two trends caused the outlet of the vessel furthest from the drainage channel to display the minimum Pt in the model. That is, the outlet of the outermost vessel is most vulnerable to collapse.

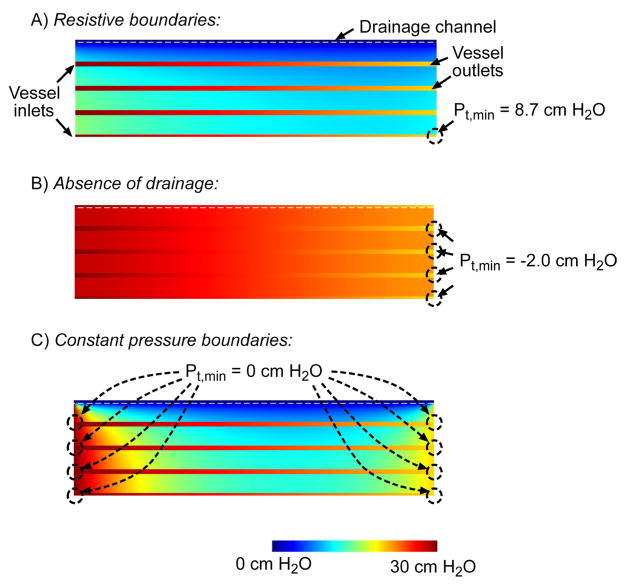

Figure 2.

(A) Interstitial and vascular pressures for a representative model (N = 4, D = 100 μm, h = 500 μm, L = 1 cm, LP = 10−10 cm3/dyn·s, K = 10−10 cm4/dyn·s, Pin − Pout = 10 cm H2O, Pout − Pdr = 20 cm H2O) with hydraulically resistive scaffold walls. The image maps the interstitial pressures (with respect to Pdr) along a cross-section of the scaffold, with the drainage channel at the top of the plot, vascular inlets on the left end, and vascular outlets on the right. The location of the minimum transmural pressure in the model, Pt,min, is indicated by a dotted circle. (B) Same as (A), but for a model with drainage channel replaced by a vessel. (C) Same as (B), but for a model with fixed-pressure boundary conditions on the scaffold walls (Pscaffold = Pin on the left wall, and Pscaffold = Pout on the right wall).

In the absence of a drainage channel, negative transmural pressures emerged in some portions of the construct, while large segments of vascular walls effectively existed at Pt = 0 cm H2O (Fig. 2B). As expected, the interstitial pressure became bracketed by the two perfusion pressures Pin and Pout. Thus, drainage channels are necessary to maintain non-negative transmural pressures.

To obtain transmural pressures that were positive everywhere, it was necessary to have drainage channels and to have scaffolds whose walls exhibited hydraulic resistance (Fig. 2C). In the absence of this resistance (i.e., with constant-pressure boundary conditions), the interstitial fluid was not insulated from perfusion pressures, and all vascular inlets and outlets had Pt = 0 cm H2O.

4.2. Effect of drainage pressures and hydraulic properties on minimum transmural pressures

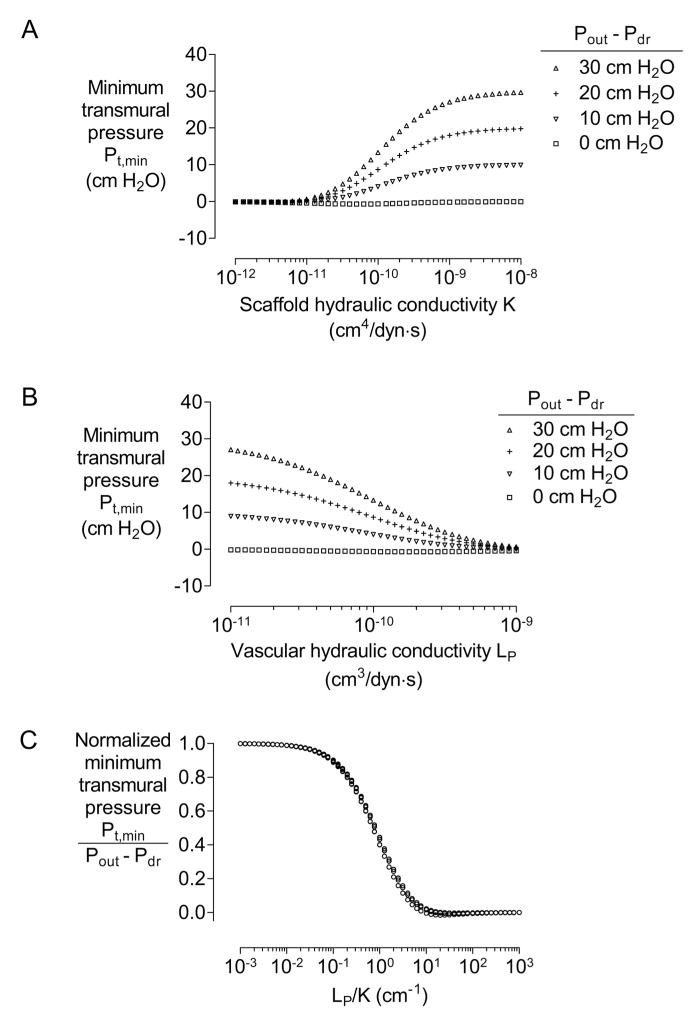

For a given model geometry and perfusion pressures, lowering the pressure Pdr at the ends of the drainage channel (or, equivalently, increasing Pout − Pdr) led to higher transmural pressures in all vessels (Fig. 3). This result held for a wide range of scaffold hydraulic conductivities K and vascular hydraulic conductivities LP (Fig. 3A and 3B). We reasoned that the transmural pressure was determined largely by the relative hydraulic resistances of the vessel wall and scaffold and by the magnitude of the driving pressure for drainage Pout − Pdr. To test this possibility, we normalized the minimum transmural pressures with Pout − Pdr, and plotted them versus the ratio of hydraulic properties LP/K (Fig. 3C). We found a remarkable overlap in curves over the entire ranges of LP, K, and Pout − Pdr. This result greatly simplifies the functional dependence of minimum transmural pressure Pt,min, and implies that Pt,min is largely proportional to Pout − Pdr and a function of LP/K.

Figure 3.

(A) Plot of minimum transmural pressure Pt,min versus scaffold hydraulic conductivity K (with K = 10−10 cm4/dyn·s). (B) Plot of Pt,min versus vascular hydraulic conductivity LP (with LP = 10−10 cm3/dyn·s). (C) Plot of normalized minimum transmural pressure Pt,min/(Pout − Pdr) versus ratio of hydraulic conductivities LP/K. All models had N = 4, D = 100 μm, h = 500 μm, L = 1 cm, and Pin − Pout = 10 cm H2O.

We note that for values of LP/K greater than ~10 cm−1, the transmural pressures are close to 0 cm H2O. In this regime, the scaffold is so resistive that little fluid filters out of the vessel walls. As a result, vascular and scaffold pressures are nearly identical, and there is little transmural pressure to stabilize against vascular collapse. Such values of LP/K are possible in dense scaffolds such as highly cross-linked alginate or poly(ethylene glycol) gels, which have small conductivities on the order of 10−11 to 10−12 cm4/dyn·s [50, 51]. Our models indicate that these materials may not possess hydraulic properties that are well-suited for drainage.

Similarly, for values of LP/K less than ~0.1 cm−1, the transmural pressures approach Pout − Pdr. Here, the scaffold is so conductive that the interstitial pressure Pscaffold is nearly constant and equal to Pdr. These values of LP/K are obtained for highly porous materials such as collagen gels, for which K is on the order of 10−8 cm4/dyn·s. Small values of LP/K can also be obtained when the vascular walls are resistive (e.g., in arterioles) [44]. In either case, the tissue is easily stabilized against collapse by setting the drainage channel at a lower pressure than vascular perfusion pressures.

4.3. Effect of scaffold geometry on minimum transmural pressures

The scaffold geometry is given by the number N of vascular “shells” that surround each drainage channel and the diameter D, spacing h, and length L of each vessel. We varied the four parameters across ranges that we considered to be experimentally realizable for engineered scaffolds (Table 1). Based on the results of the previous section, we kept Pout − Pdr equal to the intermediate value of 20 cm H2O and chose LP/K to span a range of values (0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, or 100 cm−1).

4.3.1. Number of vascular layers per drainage channel

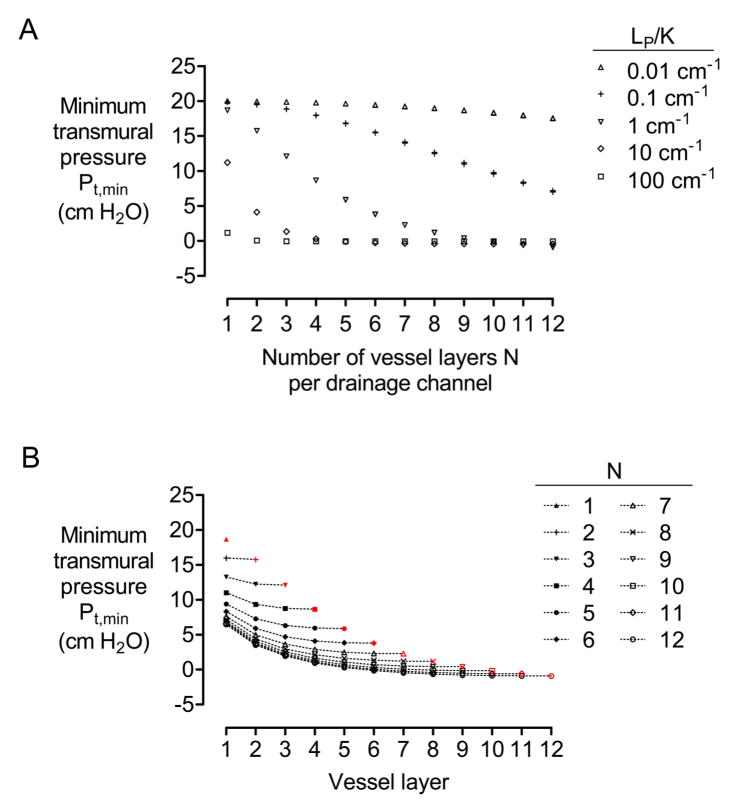

Of the four geometric parameters, the number of vascular layers N had by far the strongest influence on transmural pressure (Fig. 4A). For instance, for a hydraulic conductivity ratio of LP/K = 1 cm−1, doubling the number of vascular layers from four to eight reduced the minimum transmural pressure by over 85%. A further increase to twelve vascular layers led to negative Pt,min, as the central drainage channel became more distant from the outermost shell of vessels. This result indicates that, as more vascular layers are added to a model, eventually the drainage capacity of the central channel is overwhelmed and the influence of the drainage channel is not felt by vessels furthest from the channel. As the vessel wall becomes leakier, the effective range of a drainage channel decreases: For LP/K = 1 cm−1, the transition to negative Pt,min takes place around N of 9–10 shells; for LP/K = 10 cm−1, around N of 3–4 shells. As expected, dense scaffolds with LP/K = 100 cm−1 are so poorly drained that even models with just one shell of vessels per drainage channel have small transmural pressures, whereas highly porous scaffolds with LP/K = 0.01 cm−1 are so easily drained that models with twelve vascular layers per drainage channel still have large positive transmural pressures at the outermost shell.

Figure 4.

(A) Plot of minimum transmural pressure Pt,min versus number of vessel layers N per drainage channel. (B) Plot of minimum transmural pressure found in a given vessel layer (i.e, from the 1st to Nth layer) for models of N = 1–12. All models had D = 100 μm, h = 500 μm, L = 1 cm, Pin − Pout = 10 cm H2O, and Pout − Pdr = 20 cm H2O. In (A), K = 10−12, 10−11, 10−10, 10−9, or 10−8 cm4/dyn·s, and LP = 10−11, 10−10, or 10−9 cm3/dyn·s. In (B), LP/K = 1 cm−1, and the red symbols reproduce data from (A).

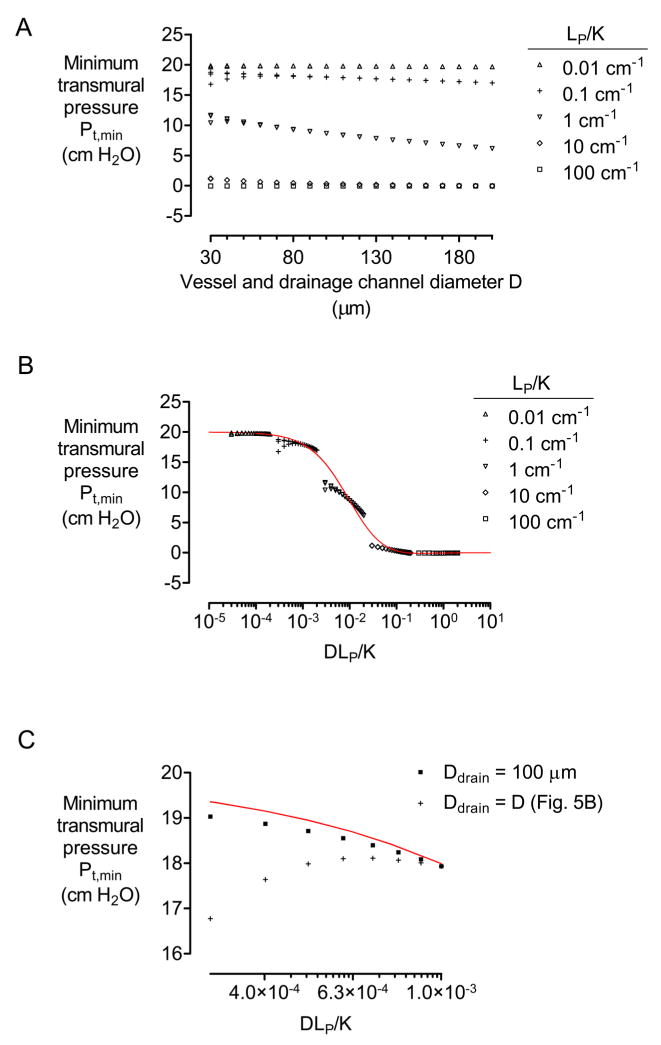

4.3.2. Diameter of vessels and drainage channel

Varying the vessel diameter D demonstrated that transmural pressure exhibits a biphasic dependence on D (Fig. 5A). With diameters in the range of 50 to 200 μm, narrower vessels and drainage channels had a larger transmural pressure, all other parameters held constant. Since narrower vessels present a smaller surface area for filtration and hence a smaller overall hydraulic pathway, we plotted minimum transmural pressure versus a normalized, dimensionless hydraulic conductivity DLP/K (Fig. 5B). These plots show that the variation of Pt,min with D mostly results from the effect of D on overall hydraulic conductance of the vessel wall (i.e., on surface area times LP).

Figure 5.

(A) Plot of minimum transmural pressure Pt,min versus diameter D of vessels and drainage channel. (B) Plot of Pt,min versus a normalized ratio of hydraulic conductivities DLP/K. (C) Plot of Pt,min versus DLP/K for models in which the diameter of the drainage channel remained 100 μm. All models had N = 4, h = 500 μm, L = 1 cm, Pin − Pout = 10 cm H2O, and Pout − Pdr = 20 cm H2O. In (A) and (B), K = 10−12, 10−11, 10−10, 10−9, or 10−8 cm4/dyn·s, and LP = 10−11, 10−10, or 10−9 cm3/dyn·s. In (C), LP = 10−9 cm3/dyn·s and K = 10−8 cm4/dyn·s. Red plots indicate data from Fig. 3C.

In some cases (e.g., for K = 10−8 cm4/dyn·s and LP = 10−9 cm3/dyn·s), however, the transmural pressures abruptly decreased as diameters decreased below 50 μm. The reason for this behavior is that the resistance of the drainage channel to axial flow increases dramatically as its diameter decreases. Thus, the drainage channel cannot accommodate the filtered fluid, and pressure gradients emerge within the drainage channel. To determine if this effect can be avoided, we solved a family of models in which the drainage channel was selectively maintained at a large diameter (100 μm), while the vessels decreased in size (Fig. 5C). This change eliminated the anomalous decreases in Pt,min. Taken together, our results imply that decreasing vessel and drainage channel diameters leads to two competing effects: 1) an increase in transmural pressure, due to lower vascular hydraulic conductance, and 2) a decrease in transmural pressure, due to higher resistance within the drainage channel. The effects counterbalance each other around diameters of ~50 μm.

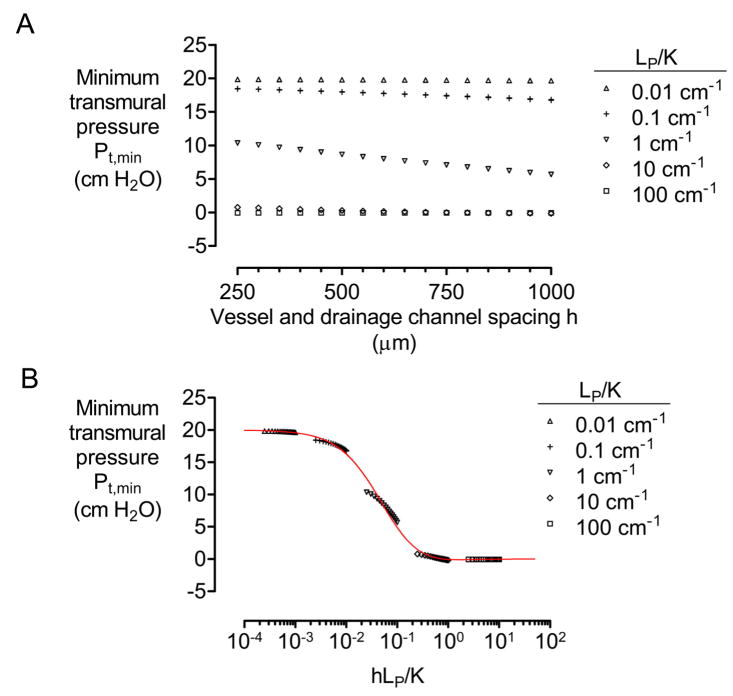

4.3.3. Spacing of vessels and drainage channel

The effect of increasing vascular spacing h is to decrease the hydraulic conductance of the scaffold between the drainage channel and outermost vessel. Thus, we expected minimum transmural pressure to decrease as vessels and drainage were spaced further apart. Although Pt,min decreased with increases in h, transmural pressure was sensitive to h only for hydraulic conductivity ratios of LP/K ~ 1 cm−1 (Fig. 6A). Plotting the transmural pressures against the dimensionless ratio hLP/K revealed that the effect of changing vascular and drainage spacing was largely due to changes in hydraulic conductance of the scaffold (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

(A) Plot of minimum transmural pressure Pt,min versus spacing h of vessels and drainage channel. (B) Plot of Pt,min versus a normalized ratio of hydraulic conductivities hLP/K. All models had N = 4, D = 100 μm, L = 1 cm, Pin − Pout = 10 cm H2O, and Pout − Pdr = 20 cm H2O. In (A) and (B), K = 10−12, 10−11, 10−10, 10−9, or 10−8 cm4/dyn·s, and LP = 10−11, 10−10, or 10−9 cm3/dyn·s. Red plot indicates data from Fig. 3C.

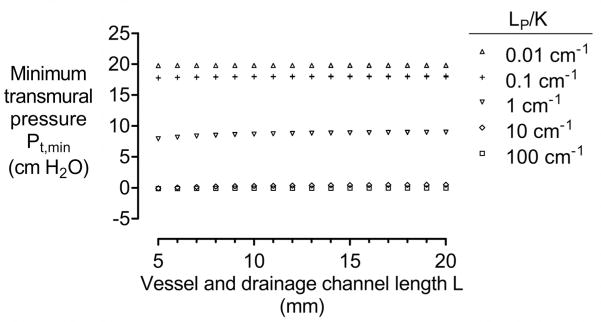

4.3.4. Length of vessels and drainage channel

Changing the length L of vessels and the drainage channel proportionally alters the hydraulic conductance of the vascular wall and scaffold. Since the ratio of conductances does not change, we expected changes in L to have little effect on transmural pressures. Indeed, even for the most sensitive case of LP/K ~ 1 cm−1, changing L from 5 mm to 20 mm only led to a ~10% increase in Pt,min (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Plot of minimum transmural pressure Pt,min versus length L of vessels and drainage channel. All models had N = 4, D = 100 μm, h = 500 μm, Pin − Pout = 10 cm H2O, and Pout − Pdr = 20 cm H2O. Here, K = 10−12, 10−11, 10−10, 10−9, or 10−8 cm4/dyn·s, and LP = 10−11, 10−10, or 10−9 cm3/dyn·s.

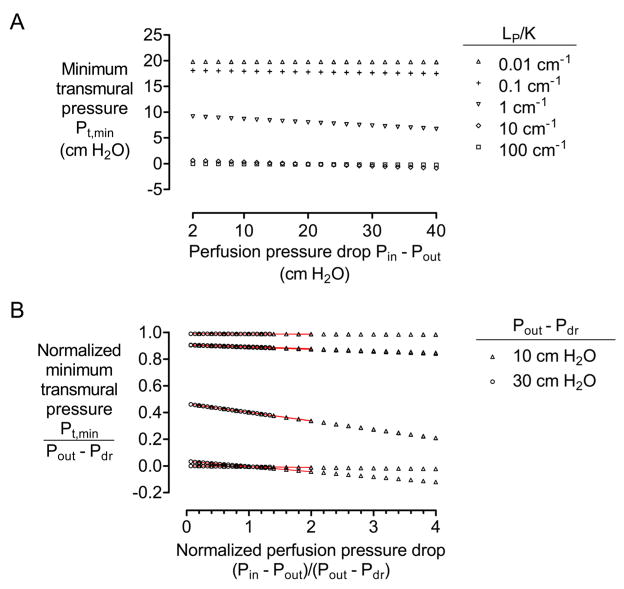

4.4. Effect of perfusion pressures on minimum transmural pressures

To determine whether the driving pressure for perfusion Pin − Pout affected transmural pressures, we solved models in which Pin − Pout varied but in which Pout − Pdr was held constant. These results indicated that the driving perfusion pressure had moderate effects on transmural pressure (Fig. 8A). For the case of LP/K ~ 1 cm−1, a four-fold increase in Pin − Pout from 10 cm H2O to 40 cm H2O led to a ~20% decrease in Pt,min. Surprisingly, increasing Pin − Pout led to decreases in transmural pressure. Plotting normalized transmural pressure Pt,min/(Pout − Pdr) versus normalized perfusion pressure (Pin − Pout)/(Pout − Pdr) demonstrated that minimum transmural pressure is proportional to Pout − Pdr and a function of the ratio of driving pressures for perfusion and drainage (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

(A) Plot of minimum transmural pressure Pt,min versus driving pressure for perfusion Pin − Pout (with Pout − Pdr = 20 cm H2O). (B) Plot of normalized minimum transmural pressure Pt,min/(Pout − Pdr) versus normalized perfusion pressure (Pin − Pout)/(Pout − Pdr). All models had N = 4, D = 100 μm, and L = 1 cm. In (A), K = 10−12, 10−11, 10−10, 10−9, or 10−8 cm4/dyn·s, and LP = 10−11, 10 −10, or 10−9 cm3/dyn·s. Red plots indicate data from (A).

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of results

Our results indicate the following methods for increasing transmural pressure in a vascularized scaffold: 1) insulate the interior of the scaffold from perfusion pressures, 2) decrease the pressure at the ends of drainage channels, 3) decrease the pressure at vascular inlets, 4) reduce the hydraulic conductivity of vascular walls, 5) increase the hydraulic conductivity of the scaffold, 6) reduce the number of vessels per drainage channel, 7) decrease the diameter of vessels without changing the size of drainage channels, 8) decrease the spacing between vessels and drainage channel, and 9) increase the lengths of vessels and drainage channel (i.e., increase the thickness of the scaffold).

Transmural pressure is not equally sensitive to these changes, however. Whereas a two-fold increase in Pout − Pdr leads to a roughly two-fold increase in minimum transmural pressure Pt,min, a two-fold increase in vascular length L only yields to a <5% increase in Pt,min. The most important parameter controlling transmural pressure was the ratio of hydraulic conductivities LP/K. Models with LP/K greater than 10 cm−1 (i.e., with leaky vessel walls or with dense scaffolds) had near-zero transmural pressures, regardless of scaffold geometry or pressures. Conversely, models with LP/K less than 0.1 cm−1 (i.e., with tight vessel walls or with highly porous scaffolds) had transmural pressures nearly equal to Pout − Pdr. Among the remaining parameters, the driving pressure for drainage Pout − Pdr and the number of vascular layers N per drainage channel had the largest effects on Pt,min. We found that the effects of changing geometric factors could be rationalized by considering changes in hydraulic conductances; the data suggest that transmural pressure has a sigmoid relationship with the ratio of geometric and materials properties DhLP/K.

5.2. Implications for microvascular tissue engineering

To show how our results can be applied in microvascular tissue engineering, we consider the geometry proposed by Vunjak-Novakovic and co-workers for perfusing engineered cardiac tissue in vitro [14]. Here, D is 330 μm, h is 700 μm, and L is 2 mm. These dimensions were selected to create a scaffold that could effectively deliver oxygen to embedded cells. Flow velocities of 0.05–0.1 cm/s, which correspond to driving perfusion pressures of <0.1 cm were considered. We assume that the channels are vascularized, that all transmural H2O, pressures must be positive to avoid collapse (e.g., by delamination of the vascular wall from the scaffold), and that ideally one wishes to obtain transmural pressures of at least 5 cm as a H2Osafety margin.

How might such a vascularized scaffold be drained? As in all cases, the scaffold will need to be shielded from the perfusion pressures, either by directly cannulating each vessel or by modifying the scaffold so that it is covered by a layer of hydraulically resistive material (e.g., a monolayer of endothelial cells). Next, a subset of cylinders will need to be cannulated to form drainage channels. We have found that LP/K should be less than 10 cm−1 to allow effective drainage (Fig. 3C). Since endothelial monolayers in vitro typically have large hydraulic conductivities around 10−9 cm3/dyn·s [45], the scaffold hydraulic conductivity should be larger than 10−10 cm4/dyn·s. Pin − Pout is very small in this example (<0.1 cm H2O); using Figure 8B, we extrapolate that the minimum transmural pressure for an N = 4 geometry (i.e, where one out of every ~50 cylinders is a drainage channel) will be ~46% and ~90% of the driving drainage pressure Pout − Pdr for scaffold conductivities of 10−9 and 10−8 cm4/dyn·s, respectively. The diameter considered in [14] is larger than those modeled in this study, while the vessel length is less than that of our usual cases; using Figures 5A and 7, we extrapolate that these conditions decrease the transmural pressure collectively by ~60% and ~10% for K of 10−9 and 10−8 cm4/dyn·s, respectively, from the case of D = 100 μm, L = 1 cm. Thus, our results suggest that one can obtain the desired drainage (Pt,min of 5 cm H2O) by using a scaffold of hydraulic conductivity 10−9 cm4/dyn·s, cannulating one of every 50 channels at atmospheric pressure, and vascularizing and perfusing the remaining channels at inlet and outlet pressures of ~27 cm H2O. For a scaffold of hydraulic conductivity 10−8 cm4/dyn·s, perfusion pressures of ~6 cm H2O are predicted.

To determine the accuracy of these predictions, we compared the extrapolated values with those obtained by direct numerical solution. We note that the vascular arrangement in [14] is essentially identical to that diagrammed in Figure 1, so direct solution is possible here. Numerical solution showed that, for a Pt,min of 5 cm H2O and LP = 10−9 cm3/dyn·s, the required outlet perfusion pressures were 25.8 and 6.6 cm H2O for K = 10−9 and 10−8 cm4/dyn·s, respectively, in good agreement with extrapolated values. In this case (and probably in many others involving parallel arrays of vessels), extrapolation from data plotted in Figures 3 through 8 gives comparable results to full numerical solution.

5.3. Towards a Krogh model of drainage

The geometry in the previous example was simple enough that it could be directly solved, but more complex geometries of interest in microvascular tissue engineering (e.g., bifurcating or three-dimensional networks with various diameters) rapidly lead to computationally intractable models. To aid in analyzing complex geometries, it may be useful to borrow the concept of a radius-of-action or “Krogh radius” [32]. In the Krogh model of oxygenation, a capillary can supply oxygen to a cylindrical shell of tissue, whose thickness is a function of oxygen consumption rate per volume, the capillary wall oxygen tension, and the diffusion constant of oxygen. The ability to describe oxygenation by a single number (the Krogh radius) provides an intuitively simple design constraint on microvascular networks for perfusion [12].

To what extent does the same concept apply to drainage systems? Here, vessels “produce” interstitial pressure, and the drainage channel “removes” this pressure; the diffusion constant of interstitial pressure is proportional to the scaffold hydraulic conductivity K [52]. We expect that models in which interstitial pressure is “produced” at the same rate per volume will have the same interstitial pressure profile. For instance, an N = 6, D = 44 μm, h = 333 μm model with 100-μm-diameter drainage channel has the same dimensions and vascular surface area per volume as an N = 4, D = 100 μm, h = 500 μm model. We expect the two models to have nearly identical Pt,min, as is observed computationally: 8.74 cm H2O for the first case, 8.66 cm H2O for the second one.

For a vascular network of arbitrary geometry, we thus suggest the following procedure for designing a drainage network: First, one calculates the vascular surface area per volume for the given geometry. Second, one designs models with the same surface area per volume, but which consist of parallel arrays of vessels; these models should span a range of sizes. Computational solution of these models, or extrapolation from data in Figures 1–8, should yield the minimum transmural pressure as a function of distance between a drainage channel and the outermost vessel. From these numbers and a desired Pt,min, one obtains a “Krogh radius” of drainage, i.e., the maximum distance allowed between a drainage channel and vessel before drainage becomes insufficient.

We point out that mathematical correspondence with the standard Krogh model is not exact: In contrast with the oxygenation model, in which oxygen concentration profiles within the Krogh radius do not change when excess tissue is added outside the Krogh radius [32], here the interstitial pressure profiles always change when vessels are added (Fig. 4B). Nevertheless, the ability to convert a complex vascular network into a roughly equivalent parallel vascular array simplifies the design of drainage systems, especially for vascular geometries that are impractical to model computationally.

5.4. Comparison with previous studies, and potential improvements

Our results are consistent with previous computational studies of drainage [16, 53]. These studies (in the area of tumor physiology) assumed that intra-tissue lymphatics were not functional, and that drainage occurred solely at the outer surface of the tissue volume. They determined that smaller tumors had lower interstitial pressures, which is consistent with our finding that a drainage channel can effectively drain only vessels in its vicinity.

Comparison with these studies also points the way to future enhancements of our model. First, we have discounted elastic coupling between vessel walls and the scaffold [18]. As a result, our model does not allow for a gradual degradation in perfusion rate as interstitial pressure rises and vessel diameter decreases. Second, we have assumed that the perfusate exerts no oncotic pressure, and that solute gradients do not exist in the scaffold. Both of these assumptions can be relaxed computationally (in the former, by using deformable meshes; in the latter, by modifying Starling’s Law and adding Fick’s Laws to the set of equations to be solved), but at considerable computational cost. We are currently exploring methods to realize these enhancements.

6. Conclusions

This work postulates that transmural pressure across a vessel must exceed a certain value to prevent vascular collapse. We used computational models to examine the implications of this postulate on the pressures and flows within a vascularized scaffold. We determined that the vascular geometry and the hydraulic properties of the vessel wall and the scaffold play complementary roles in determining transmural pressure.

An important principle demonstrated by our models is that, to maintain positive transmural pressure, the interstitial fluid must be permitted to flow into drainage channels and must be insulated from the pressures that drive vascular flow. We also found that the ratio of vascular to interstitial conductances will largely determine whether a scaffold can be effectively drained. In particular, if the hydraulic conductance of the scaffold is very low (as can occur in dense or large gels), then large portions of the capillary network will exist at approximately zero transmural pressure, a situation that does not favor vascular patency.

We found that a drainage channel—no matter what pressure it is set at—can only maintain a limited number of neighboring vessels above a threshold transmural pressure. A drainage channel thus has a limited range, which defines a tissue region for drainage similar in concept to the Krogh cylinder of oxygenation. The existence of this radius-of-action can potentially simplify the design of drainage systems for complex vascular networks. As our computational resources become more powerful, we intend to test whether vascular surface area per volume can accurately predict the spacing of channels needed to drain complex networks.

We note that the parallel geometry studied here can be realized experimentally by a variety of techniques [9, 10, 54–56]. Experimental tests of our computational predictions are thus possible, and will require the determination of closing pressures for engineered vessels.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dan Kamalic for assistance with the Whitaker Computational Facility in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Boston University, and Paul Barbone, Keith Wong, and Celeste Nelson for helpful suggestions. This work is supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIH award R01 EB005792).

Glossary of Terms

- N

Number of layers of vessels per drainage channel

- D

Diameter of vessels

- h

Inter-axial distance between vessels

- L

Length of vessels, thickness of scaffold

- K

Interstitial hydraulic conductivity

- LP

Hydraulic conductivity of vessel wall

- Pin, Pout, Pdr

(Constant) hydrostatic pressures in vascular inlets, vascular outlets, and ends of drainage channel

- Pvessel, Pdrain

Hydrostatic pressures in vessels and drainage channel

- Pscaffold

Interstitial pressure

- Pt

Transmural pressure (= Pvessel − Pscaffold)

- vvessel, vdrain

Fluid velocities in vessels and drainage channel

- vscaffold

Velocity of interstitial fluid

- vn

Velocity of interstitial fluid normal to vessel wall (i.e., filtration velocity)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Laschke MW, Harder Y, Amon M, Martin I, Farhadi J, Ring A, et al. Angiogenesis in tissue engineering: breathing life into constructed tissue substitutes. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2093–2104. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rouwkema J, Rivron NC, van Blitterswijk CA. Vascularization in tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26:434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lokmic Z, Mitchell GM. Engineering the microcirculation. Tissue Eng B. 2008;14:87–103. doi: 10.1089/teb.2007.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schechner JS, Nath AK, Zheng L, Kluger MS, Hughes CC, Sierra-Honigmann MR, et al. In vivo formation of complex microvessels lined by human endothelial cells in an immunodeficient mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA. 2000;97:9191–9196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150242297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain RK, Au P, Tam J, Duda DG, Fukumura D. Engineering vascularized tissue. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:821–823. doi: 10.1038/nbt0705-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson TP, Peters MC, Ennett AB, Mooney DJ. Polymeric system for dual growth factor delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1029–1034. doi: 10.1038/nbt1101-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black AF, Berthod F, Heureux LN, Germain L, Auger FA. In vitro reconstruction of a human capillary-like network in a tissue-engineered skin equivalent. FASEB J. 1998;12:1331–1340. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.13.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levenberg S, Rouwkema J, Macdonald M, Garfein ES, Kohane DS, Darland DC, et al. Engineering vascularized skeletal muscle tissue. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:879–884. doi: 10.1038/nbt1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabodi M, Choi NW, Gleghorn JP, Lee CS, Bonassar LJ, Stroock AD. A microfluidic biomaterial. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13788–13789. doi: 10.1021/ja054820t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chrobak KM, Potter DR, Tien J. Formation of perfused, functional microvascular tubes in vitro. Microvasc Res. 2006;71:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golden AP, Tien J. Fabrication of microfluidic hydrogels using molded gelatin as a sacrificial element. Lab Chip. 2007;7:720–725. doi: 10.1039/b618409j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi NW, Cabodi M, Held B, Gleghorn JP, Bonassar LJ, Stroock AD. Microfluidic scaffolds for tissue engineering. Nat Mater. 2007;6:908–915. doi: 10.1038/nmat2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janakiraman V, Mathur K, Baskaran H. Optimal planar flow network designs for tissue engineered constructs with built-in vasculature. Ann Biomed Eng. 2007;35:337–347. doi: 10.1007/s10439-006-9235-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radisic M, Deen W, Langer R, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Mathematical model of oxygen distribution in engineered cardiac tissue with parallel channel array perfused with culture medium containing oxygen carriers. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1278–H1289. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00787.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryan TJ. Structure and function of lymphatics. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93:18S–24S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12580899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christenson JT, Shawa NJ, Hamad MM, Al-Hassan HK. The relationship between subcutaneous tissue pressures and intramuscular pressures in normal and edematous legs. Microcirc Endothelium Lymphatics. 1985;2:367–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noddeland H, Riisnes SM, Fadnes HO. Interstitial fluid colloid osmotic and hydrostatic pressures in subcutaneous tissue of patients with nephrotic syndrome. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1982;42:139–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid-Schönbein GW. Biomechanics of microcirculatory blood perfusion. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 1999;1:73–102. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.1.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mellander S, Albert U. Effects of increased and decreased tissue pressure on haemodynamic and capillary events in cat skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1994;481:163–175. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaskell P, Krisman AM. Critical closing pressure of vessels supplying the capillary loops of the nailfold. Circ Res. 1958;6:461–467. doi: 10.1161/01.res.6.4.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacPhee PJ, Michel CC. Subatmospheric closing pressures in individual microvessels of rats and frogs. J Physiol. 1995;484:183–187. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girling F. Critical closing pressure and venous pressure. Am J Physiol. 1952;171:204–207. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1952.171.1.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nichol J, Girling F, Jerrard W, Claxton EB, Burton AC. Fundamental instability of the small blood vessels and critical closing pressures in vascular beds. Am J Physiol. 1951;164:330–344. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1951.164.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clayton JM, Hayes AC, Barnes RW. Tissue pressure and perfusion in the compartment syndrome. J Surg Res. 1977;22:333–339. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(77)90152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shrier I, Magder S. Pressure-flow relationships in in vitro model of compartment syndrome. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:214–221. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.1.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panerai RB. The critical closing pressure of the cerebral circulation. Med Eng Phys. 2003;25:621–632. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4533(03)00027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blake TR, Gross JF. Analysis of coupled intra- and extraluminal flows for single and multiple capillaries. Math Biosci. 1982;59:173–206. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleischman GJ, Secomb TW, Gross JF. Effect of extravascular pressure gradients on capillary fluid exchange. Math Biosci. 1986;81:145–164. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salathe EP, An K-N. A mathematical analysis of fluid movement across capillary walls. Microvasc Res. 1976;11:1–23. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(76)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleischman GJ, Secomb TW, Gross JF. The interaction of extravascular pressure fields and fluid exchange in capillary networks. Math Biosci. 1986;82:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Apelblat A, Katzir-Katchalsky A, Silberberg A. A mathematical analysis of capillary-tissue fluid exchange. Biorheology. 1974;11:1–49. doi: 10.3233/bir-1974-11101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krogh A. The number and distribution of capillaries in muscles with calculations of the oxygen pressure head necessary for supplying the tissue. J Physiol. 1919;52:409–415. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1919.sp001839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grinberg O, Novozhilov B, Grinberg S, Friedman B, Swartz HM. Axial oxygen diffusion in the Krogh model: modifications to account for myocardial oxygen tension in isolated perfused rat hearts measured by EPR oximetry. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2005;566:127–134. doi: 10.1007/0-387-26206-7_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Popel AS. Theory of oxygen transport to tissue. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 1989;17:257–321. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmid-Schönbein GW. Microlymphatics and lymph flow. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:987–1028. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levick JR. Flow through interstitium and other fibrous matrices. Q J Exp Physiol. 1987;72:409–437. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1987.sp003085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guyton AC, Scheel K, Murphree D. Interstitial fluid pressure: III. Its effect on resistance to tissue fluid mobility. Circ Res. 1966;19:412–419. doi: 10.1161/01.res.19.2.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swartz MA, Fleury ME. Interstitial flow and its effects in soft tissues. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2007;9:229–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.151850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michel CC. Starling: the formulation of his hypothesis of microvascular fluid exchange and its significance after 100 years. Exp Physiol. 1997;82:1–30. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1997.sp004000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price GM, Chrobak KM, Tien J. Effect of cyclic AMP on barrier function of human lymphatic microvascular tubes. Microvasc Res. 2008;76:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiedeman MP. Architecture. In: Renkin EM, Michel CC, editors. Handbook of Physiology; Section 2: The Cardiovascular System. Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society; 1984. pp. 11–40. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levick JR. Capillary filtration-absorption balance reconsidered in light of dynamic extravascular factors. Exp Physiol. 1991;76:825–857. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1991.sp003549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michel CC. Fluid movements through capillary walls. In: Renkin EM, Michel CC, editors. Handbook of Physiology; Section 2: The Cardiovascular System. Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society; 1984. pp. 375–409. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim M-H, Harris NR, Tarbell JM. Regulation of hydraulic conductivity in response to sustained changes in pressure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2551–H2558. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00602.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suttorp N, Hessz T, Seeger W, Wilke A, Koob R, Lutz F, et al. Bacterial exotoxins and endothelial permeability for water and albumin in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:C368–C376. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.255.3.C368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeMaio L, Tarbell JM, Scaduto RC, Jr, Gardner TW, Antonetti DA. A transmural pressure gradient induces mechanical and biological adaptive responses in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H731–H741. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00427.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weinberg CB, Bell E. A blood vessel model constructed from collagen and cultured vascular cells. Science. 1986;231:397–400. doi: 10.1126/science.2934816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bell E, Ehrlich HP, Buttle DJ, Nakatsuji T. Living tissue formed in vitro and accepted as skin-equivalent tissue of full thickness. Science. 1981;211:1052–1054. doi: 10.1126/science.7008197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gutowska A, Jeong B, Jasionowski M. Injectable gels for tissue engineering. Anat Rec. 2001;263:342–349. doi: 10.1002/ar.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Comper WD, Zamparo O. Hydraulic conductivity of polymer matrices. Biophys Chem. 1989;34:127–135. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(89)80050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zimmermann H, Wählisch F, Baier C, Westhoff M, Reuss R, Zimmermann D, et al. Physical and biological properties of barium cross-linked alginate membranes. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1327–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Detournay E, Cheng AHD. Fundamentals of poroelasticity. In: Fairhurst C, editor. Comprehensive Rock Engineering: Principles, Practice and Projects; Vol II: Analysis and Design Method. New York, NY: Pergamon Press; 1993. pp. 113–171. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baish JW, Netti PA, Jain RK. Transmural coupling of fluid flow in microcirculatory network and interstitium in tumors. Microvasc Res. 1997;53:128–141. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1996.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Therriault D, White SR, Lewis JA. Chaotic mixing in three-dimensional microvascular networks fabricated by direct-write assembly. Nat Mater. 2003;2:265–271. doi: 10.1038/nmat863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nguyen KT, West JL. Photopolymerizable hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials. 2002;23:4307–4314. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Price GM, Chu KK, Truslow JG, Tang-Schomer MD, Golden AP, Mertz J, et al. Bonding of macromolecular hydrogels using perturbants. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6664–6665. doi: 10.1021/ja711340d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]