Abstract

Until recently, only nematodes among animals had a well-defined endogenous small interfering RNA (endo-siRNA) pathway. This has changed dramatically with the recent discovery of diverse intramolecular and intermolecular substrates that generate endo-siRNAs in Drosophilamelanogaster and mice. These findings suggest broad and possibly conserved roles for endogenous RNA interference in regulating host-gene expression and transposable element transcripts. They also raise many questions regarding the biogenesis and function of small regulatory RNAs in animals.

RNA interference (RNAi), the process by which double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is processed into small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that silence homologous transcripts, is both a fascinating cellular machinery and a powerful experimental technique. Despite an avalanche of RNAi research over the past decade, however, a nagging question remained mostly unanswered: what good is RNAi to the organism itself?

Substantial roles for RNAi in regulating endogenous gene expression have been difficult to ascertain because Drosophila melanogaster1,2 and Caenorhabditis elegans3,4 mutants that selectively inactivate RNAi seem to be normal and fertile. These mutants are hypersensitive to viruses, which suggests that RNAi defends against selfish and invasive nucleic acids5. But if RNAi had an ancestral role in virus restriction it seems to have been subsumed in vertebrates by the interferon pathway. In fact, the nonspecific capacity of dsRNA to activate the interferon response, thereby leading to the general inhibition of cellular translation, was widely perceived to preclude substantial roles for endogenous RNAi in vertebrates.

Eight concurrent papers from the Zamore, Sasaki, Siomi, Lai and Hannon laboratories recently described a rich diversity of endogenous siRNAs (endo-siRNAs) in mice6,7 and D. melanogaster8–13. These studies introduce unanticipated complexity in small-RNA sorting pathways and in the biological roles of siRNAs. We highlight these new classes of endo-siRNAs and the pressing questions that are raised by their discovery.

Argonaute-bound small RNAs

Argonaute proteins lie at the heart of related small-RNA pathways that operate in organisms as diverse as Archaea, plants and animals14. They bind various small RNAs that are < 32 nucleotides (nt) in length which guide the Argonaute complexes to their regulatory targets (FIG. 1).

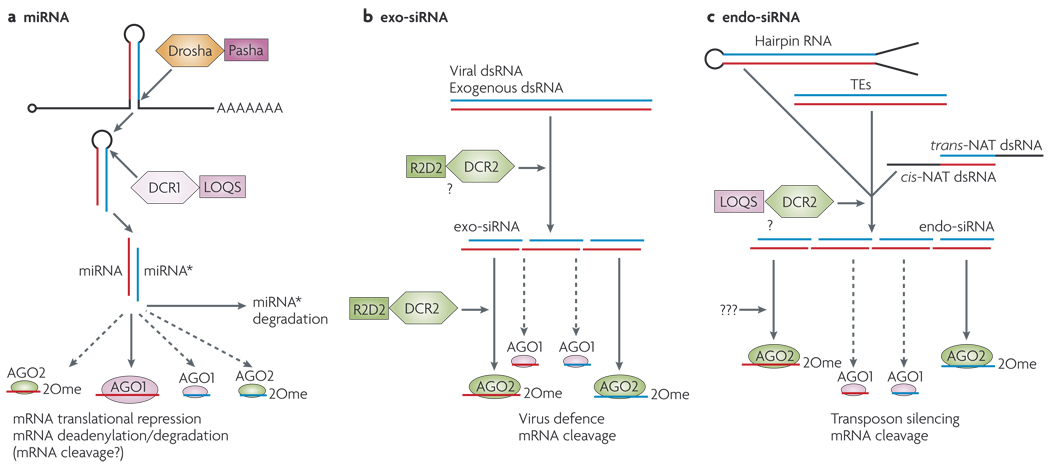

Figure 1. Small RNA pathways in Drosophila melanogaster.

In Drosophila melanogaster, micro (mi)RNAs are ~22 nucleotides (nt) long, have free hydroxy groups at their 3′ ends, and associate primarily with the Argonaute protein AGO1. Small interfering (si)RNAs are ~21 nt, are methylated at their 3′ ends, and associate primarily with AGO2. Three main protein families are denoted with RNase III enzymes (Drosha, Dicer-1 (DCR1) and DCR2; shown as hexagons), their dsRNA-binding domain (dsRBD) partners (Pasha, Loquacious (LOQS) and R2D2; shown as squares) and Argonaute proteins (AGO1 and AGO2; shown as ovals), a | miRNA pathway Endogenous transcripts that contain short inverted repeats are processed into ~21–22 nt RNAs that mostly function to repress endogenous targets by translational repression and deadenylation by AGO1. miRNA* is the species on the other side of the hairpin to the miRNA. b | In D. melanogaster, viral dsRNA or artificial dsRNA produce exogenous siRNAs (exo-siRNAs) that are mostly sorted to AGO2 and restrict viral replication or cleave designed targets, c | D. melanogaster cells and mammalian oocytes produce several sources of endogenous dsRNA — transposable elements (TEs), cis-natural antisense transcripts (cis-NATs), trans-NATsand hairpin RNA transcripts—that are processed into endo-siRNAs that load mostly AGO2. These repress transposon transcripts or endogenous mRNAs. Note that a minority of miRNAs programme AGO2 and a small fraction of exo- and endo-siRNAs associate with AGO1, but the functional significance of this is currently unknown. 2Ome, 2′-O-methyl group.

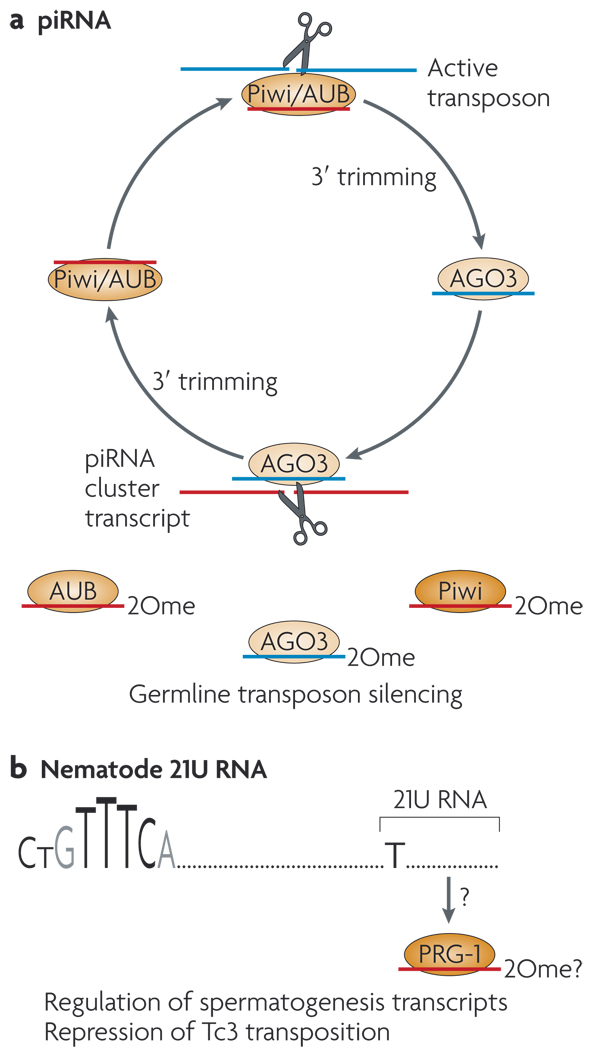

Among animals, the AGO and Piwi subclasses constitute two main classes of conserved Argonaute proteins. AGO proteins bind to microRNAs (miRNAs)14,15 — RNAs of ~ 22 nt that derive from host transcripts with short (usually < 100 nt) inverted repeats. These repeats are processed by the RNase III enzymes Drosha (in the nucleus) and Dicer (in the cytoplasm) (FIG. la). Specialized AGO proteins with efficient ‘slicing’ activity are the carriers of 21 nt siRNAs2,16,17. Exogenous dsRNAs are processed into siRNAs in the cytoplasm by Dicer, and therefore they do not require Drosha (FIG. 1 b). Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are slightly longer RNAs (~24–32 nt) that are bound by Piwi-family proteins, which also have slicer activity18–20. Although their biogenesis is not completely understood, a major pathway for piRNA production involves reciprocal cleavages of sense and antisense substrates by antisense and sense piRNAs, respectively19,21 (FIG. 2a).

Figure 2. Specialized small-RNA regulatory pathways in the animal germ line.

These are mediated by Piwi-class Argonaute proteins (ovals), a | The Piwi-interacting (pi)RNA pathway operates in the Drosophila melanogaster and vertebrate germ line. A ‘ping-pong’ strategy amplifies piRNAs from complementary transcripts, in which the slicer activity of Piwi proteins (Piwi, Aubergine (AUB) and AGO3 in D. melanogaster) reciprocally define piRNA 5′ ends. The mechanism that defines the 3′ ends of piRNAs is not known. A conserved role of the piRNA pathway is to restrict transposon activity in the germ line; however, there might be other roles for abundant non-transposon-derived piRNAs that are found in mammals, b | Nematode 21U RNAs might be a functional analogue of piRNAs. These 21-nucleotide RNAs begin with U and are produced from genomic loci with a characteristic upstream motif (CTGTTTCA), and they are bound by the Piwi protein PRG-1. The details of 21U biogenesis and function are unclear, but 21Us are linked to spermatogenesis and control of Tc3 transposition. 2Ome, 2′-O-methyl group.

Primary and secondary nematode siRNAs

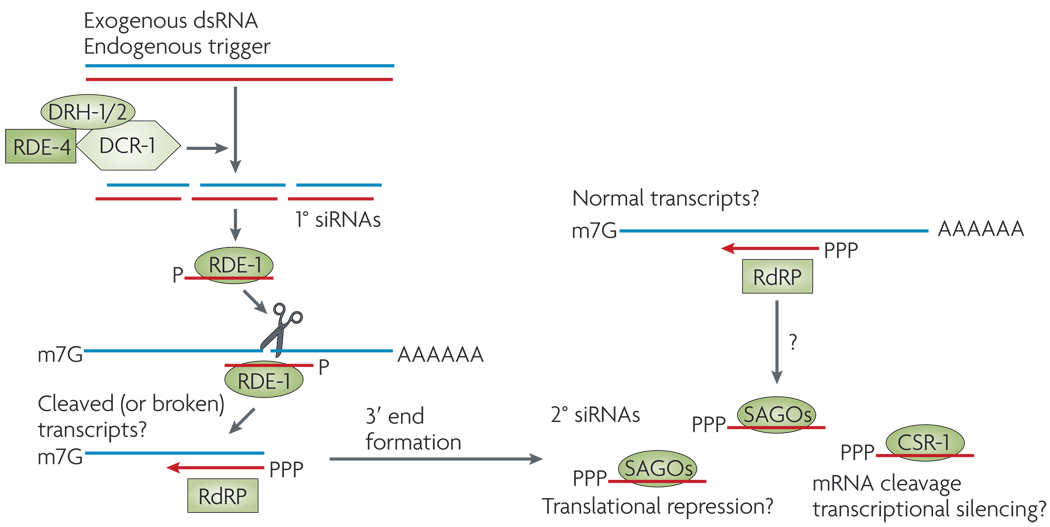

Until recently, C. elegans was the only animal for which endo-siRNAs had been well characterized. Primary siRNAs that are processed by dicing dsRNA are exceedingly rare in this organism22–24. Instead, the 3′ ends of targets that have been cleaved by primary siRNAs are recognized by an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP), which generates abundant, untemplated, secondary siRNAs with distinctive 5′ triphosphates (FIG. 3). Secondary siRNAs are then loaded into specialized secondary Argonautes (SAGOs)25. Because other animals do not seem to encode RdRP or SAGOs, it is not evident that the mechanism for worm siRNA biogenesis is broadly conserved. Nematodes also lack conventional piRNAs, as the Piwi homologue PRG-1 contains ‘21U’ RNAs. The biogenesis of these 21 nt RNAs does not seem to be related to that of fly or vertebrate piRNAs22,26–28 (FIG. 2b). Therefore, fundamental aspects of conserved animal small-RNA pathways have clearly been altered in C. elegans.

Figure 3. Nematode small interfering RNA pathways.

Processing of double-stranded (ds) substrates by a complex that includes an RNAse III enzyme (Dicer-1 (DCR-1), a dsRNA-binding partner (dsRBD; RDE-4) and Dicer-related helicases (DRH-1/2) generates primary (1°) small interfering (si)RNAs with 5′ monophosphates (P). These load into the RDE-1 Argonaute protein and can slice complementary transcripts. Cleaved transcripts, and possibly uncleaved transcripts, are substrates for an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) complex that generates secondary (2°) siRNAs that have 5′ triphosphates (PPP). These are loaded into various secondary Argonautes (SAGOs) that lack slicer activity, or into the Argonaute slicer CSR-1.

Endo-siRNAs in flies and mice

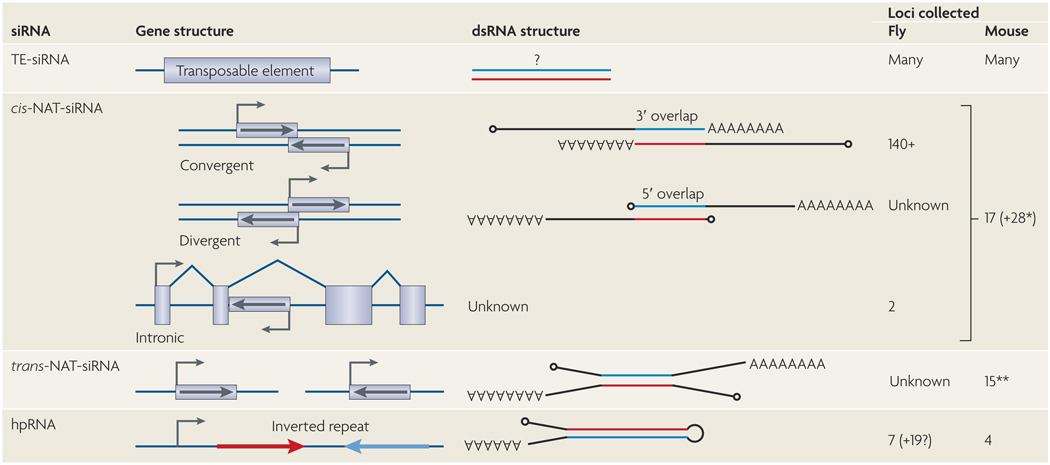

Recent work now reveals diverse sources of endo-siRNAs in D. melanogaster and in mouse. Most of these endo-siRNA classes seem to be analogous between species, and include those derived from transposable elements, from complementary annealed transcripts, and from long ‘fold-back’ transcripts called hairpin RNAs (hpRNAs).

siRNAs from transposable elements

Because of the mutagenic consequences of transposable elements (TEs), powerful mechanisms are needed to restrict their activity. Such protection is indispensable in the germ line to maintain faithful transmission of the genome. In this context, piRNAs mediate a major defence against TEs29. However, scattered reports in the literature indicated that canonical RNAi also influences TEs. This was most clear in C. elegans, because many RNAi-defective mutants also deregulate transposons3,30. It was proposed that transcriptional read-through across Tcl transposable elements might produce intramolecular dsRNA between the terminal inverted repeats, the processing of which by RNAi could generate siRNAs that silence Tcl elements in trans31.

A conundrum for mammalian piRNA studies was that although multiple mouse Piwi-gene mutants exhibit testicular defects, transposon activation and sterility, corresponding mutant ovaries were normal and functional32–34. Instead, Dicer-mutant ovaries and oocytes exhibit higher levels of certain retrotransposon transcripts35,36. This is consistent with either an miRNA-based system for TE control or perhaps the usage of endo-siRNAs. In fact, earlier small-scale sequencing from mouse oocytes and testes revealed that some siRNAs derived from retrotransposons37, which could silence long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) in trans38. Newer large-scale cloning provided clearer evidence for TE-siRNAs in mouse oocytes6,7. Many of these mapped to the same genomic locations as piRNA clusters, which raised the possibility that these specialized ‘master loci’ are involved in both piRNA-mediated and siRNA-mediated TE control. However, some transposon classes were apparently targeted by only one of these RNA classes, which suggested that piRNAs or siRNAs preferentially control certain TEs. For example, several long-terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons were nearly exclusively targeted by siRNAs6,7.

In D. melanogaster, deep sequencing of the small RNAs that directly associate with AGO2 (the Argonaute that mediates RNAi) revealed that TEs are a substantial source of RNAs of precisely 21 nt11,12. Similar conclusions were reached by sequencing RNAs that were β-eliminated — this prevents RNAs from being ligated on their 3′ ends, unless they bear a 3′ modification, and thus enriches AGO2-loaded RNAs8 — or by analysing total head or cultured-cell RNAs13. Their accumulation is dependent on DCR2 (one of the two Dicers in D. melanogaster, and the one that generates exogenous siRNAs14; FIG. 1c), and the depletion or mutation of either DCR2 or AGO2 elevates TE transcript levels8,11–13. The TE-siRNA response is extremely active in various lines of cultured cells and correlates with the strong genomic amplification of specific LTR retrotransposons in these cells. Therefore, both TE-siRNAs and TE-piRNAs repress transposon transcripts in flies and mammals (FIG. 4).

Figure 4. Substrates for endo-siRNA production in flies and mouse.

The precise structure of the double-stranded (ds)RNA substrates of small interfering (si)RNAs derived from transposable elements (TEs) is unknown, but hundreds or thousands of TEs are inferred to directly generate siRNAs. siRNAs derived from cis-natural antisense transcripts (cis-NATs) involve bidirectional transcription across the same genomic DNA, and can be convergent, divergent or involve annotated introns and/or internal exons. Drosophila melanogaster cis-NAT-siRNAs derive almost exclusively from 3′-overlapping mRNAs, but two highly-expressed siRNA loci include annotated introns. Watanabe and colleagues describe 17 cis NAT siRNA loci7, but their precise categorization is ambiguous as many of them lack an annotated overlapping transcript. Tarn and colleagues describe another 28 mRNAs (*) with siRNAs whose complementary transcript was not specifically described6. These might be cis-NATs, but some might represent trans natural antisense transcript (trans NAT) pairs. Trans NAT dsRNAs form between transcripts that are produced from distinct genomic locations, and usually comprise an mRNA and an antisense-transcribed pseudogene. Based on the cumulative data of Tarn et al.6 and Watanabe et al.7,15 trans-NAT gene-pseudogene pairs generate siRNAs (**; some of the 28 mRNAs listed in the cis-NAT-siRNA category might have antisense pseudogenes that were not reported). siRNAs that are derived from hairpin RNA (hpRNAs) are long, inverted repeat transcripts whose double-stranded segment is typically much longer than that of miRNA precursors. In D. melanogaster, one of the 7 identified hpRNA loci encodes 20 hairpin direct repeats, which can function autonomously or as components of higher-order hairpins. The figure shows the numbers of loci that were collected from the recently published studies, but these numbers will probably increase with future studies.

siRNAs from cis-natural antisense transcripts

Cis-natural antisense transcript (cis-NAT) arrangements are genomic regions that encode exons on both DNA strands, and can involve 5′, 3′ or internal exons (FIG. 4). Careful analysis of small-RNA sequences in mouse oocytes7 and D. melanogaster tissues and cultured cells8,9,11,12 revealed that cis-NAT overlaps are favourable for siRNA production. The extent of 21 nt RNA production was limited to annotated exons that are transcribed bidirectionally, excluding adjacent introns. D. melanogaster cis-NAT-siRNAs are dependent on DCR2, and mouse cis-NAT-siRNAs are similarly Dicer-dependent. However, although virtually all cis-NAT-siRNAs in flies derived from 3′ untranslated region (UTR) overlaps, one of the abundant mouse cis-NAT-siRNA loci involved Pdzd 11/Kif4, whose transcripts overlap on their 5′ UTRs (FIG. 4).

The levels of the 3′-overlapping transcripts Pdzd 11 and Kif4 increased modestly in mouse Dicer mutants7, consistent with an autoregulatory activity of the siRNAs generated by this cis-NAT. D. melanogaster cis-NAT-siRNAs specifically load AGO2, but evidence for changes in their progenitor transcripts on loss of DCR2 or AGO2 was equivocal. However, D. melanogaster cis-NAT-siRNA genes (but not cis-NAT genes in general) exhibited striking enrichment for several nucleic-acid-based functions, including transcription cofactors, deoxyribo-nucleases and ribonucleases9. In addition, most co-expressed cis-NATs in D. melanogaster S2 cells did not generate siRNAs. These data indicate that only a subset of co-expressed cis-NAT pairs are selected for siRNA production, presumably reflecting an endogenous functional use. Intriguingly, one of the most highly expressed cis-NAT-siRNA loci in the entire genome involves the CG7739/Ago2 gene pair8,9,12 — thus AGO2 carries its own siRNAs.

A special class of cis-NAT-siRNAs come from the D. melanogaster klarsicht (klar) gene, which is involved in lipid-droplet transport and nuclear migration, and from the thickveins (tkv) gene, which is involved in transforming growth factor-β signalling9,12. Although these loci produce 3′ modified, 21 nt, AGO2-bound RNAs from both DNA strands, they seem to involve a specialized mechanism for extremely efficient cis-NAT-siRNA production over extended genomic intervals that are 5–10 kb in length9,12. In addition, klar and tkv are not 3′ cis-NATs, but instead involve overlaps with 5′ exons, internal transcript exons and/or annotated intronic regions. Therefore, the strategy for klar and tkv siRNA production seems to differ from that of conventional cis-NAT-siRNAs.

siRNAs from mammalian pseudogene-gene pairs

Mammalian genomes encode large numbers of pseudogenes, which are presumed to be non-functional entities that will eventually be lost. Small-RNA cloning from mouse oocytes revealed an unexpected class of ‘functional’ pseudogenes. Multiple genes with antisense-transcribed pseudogenes were inferred to anneal with their complementary progenitors (as trans-NATs) and be diced into siRNAs6,7. The existence of siRNAs that bridge exon-exon junctions suggested that mature mRNAs constitute the dsRNA substrate, as suggested for cis-NAT-siRNA pairs. Microarray profiling and quantitative PCR analysis of Dicer-mutant oocytes revealed substantial upregulation of multiple genes with complementary siRNAs (FIG. 4), indicating that this system regulates endogenous gene expression6,7. It is unclear whether the dicing of targets during trans-NAT-siRNA biogenesis accounts for target regulation, or whether pseudogene-derived antisense siRNAs actively slice sense-strand mRNAs (FIG. 1c). In at least one case — histone deacetylase-1 (Hdac1) — siRNAs derived exclusively from sense-antisense pseudogene duplexes, which were inferred to repress functional Hdac1 trancripts6.

Earlier functional tests showed that long dsRNA does not activate protein kinase R or the interferon response in oocytes, as it does in most other mammalian cells39,40. Therefore, oocytes might provide a favourable setting for the exploitation of endogenous RNAi to regulate host transcripts. Genes with complementary pseudogene siRNAs are heavily enriched for microtubule-related functions6. This suggests a regulatory focus to the trans-NAT-siRNA pathway.

siRNAs from hpRNA transcripts

Although animal miRNA hairpins are usually < 100 nt, plant miRNA hairpins can be significantly longer41. Because of this property, the hairpin precursors of some plant miRNAs were not initially recognized. Likewise, some ‘long’ miRNA hairpins that are double the length of typical miRNAs were only recently identified in D. melanogaster42. Therefore, animal RNAs that map to inverted repeats might have escaped conventional miRNA annotation.

Bioinformatics studies in D. melanogaster revealed a number of candidate loci that produce small RNAs from extended inverted repeats that are termed hairpin RNAs (hpRNAs), the stems of which were up to 400 base pairs in length10. At least seven distinct loci generate siRNAs, and the hp-CG4068 locus alone encodes 20 tandem hairpins10–12. Despite their structural similarity to miRNAs, hpRNAs are processed by DCR2 instead of DCR1, and generate 3′ blocked siRNAs that load AGO2 (REFS 10–12) (FIG. 1). As with siRNAs from artificial long-inverted repeats, the siRNA duplexes derived from hpRNAs are phased and direct AGO2 to cleave targets.

One of the hp-CG4068 siRNAs is highly complementary to the coding region of mutagen-sensitive-308 (mus308), a DNA polymerase that is involved in the DNA-damage response, and can cleave this target site10,12. In this case, mus308 is the only obvious target of the many siRNAs that are generated by hp-CG4068. However, hp-CG18854 is a pseudogene with substantial homology to CG8289, which encodes a chromodomain protein, and elevated hp-CG 18854 could repress CG8289 in trans10. Curiously, several candidate hpRNA loci were identified in mouse, including a long-inverted repeat pseudogene of the Ran GTPase-activating protein-1 (Rangap1) gene6,7. It is unclear whether these hpRNA pathways are conserved or convergent, but they at least suggest that analogous systems operate in D. melanogaster and mammals. However, it is clear that entry into an endo-siRNA pathway can endow pseudogenes in both species with regulatory activity.

Fly endo-siRNAs require Loquacious

There are two Dicers in D. melanogaster — DCR1 cleaves pre-miRNA hairpins into miRNA duplexes, whereas DCR2 cleaves long dsRNA into siRNA duplexes14 (FIG. 1). Each Dicer directly binds to a dsRNA-binding domain (dsRBD) partner that aids its function. DCR2 interacts with R2D2 (whose name derives from the fact that it contains two dsRNA-binding domains (R2) and is associated with DCR2 (D2)), which is essential for the loading of siRNA into AGO2 (REFS 43,44). DCR1 interacts with Loquacious (LOQS), which promotes its ability to cleave pre-miRNA hairpins, the products of which are preferentially loaded into AGO1 (REFS 45–47).

Although the attractive symmetry of RNase III, dsRBD and AGO partnerships in the RNAi and miRNA pathways lent support to the proposed division of these pathways, genetic observations suggested that there are much more complex interactions among these factors. For example, unlike Dcr2 mutants, r2d2 mutants reveal its requirement for early development and female fertility. Moreover, r2d2 (but not Dcr2) phenotypes are strongly enhanced on reduction of Dcr1 (REF 48). Reciprocally, Dcr1 proved to be an RNAi-defective mutant1. There is substantial functional overlap between AGO1 and AGO2, as detected by double-mutant analysis49, and some miRNAs sort to both AGO1 and AGO2 (REFS 11,12,50–52). Finally, loqs functions in inverted-repeat RNA-mediated silencing46. These findings indicate that there is substantial crosstalk between the RNAi and miRNA pathways.

Despite its original classification as a core component of the miRNA pathway, loqs-null mutants have only modest defects in the maturation of many miRNAs53. It seems that DCR1 can cleave pre-miRNAs without LOQS, albeit with lowered efficiency that varies between miRNAs53. Surprisingly, LOQS is essential for the accumulation of many endo-siRNAs9,10,12,13 (FIG. 1c). At least some of the members of all of the siRNA classes — TE-siRNAs, cis-NAT-siRNAs and hpRNA-siRNAs — are dependent on LOQS. Although previous tests did not reveal a physical interaction between LOQS and DCR2, proteomic analysis of DCR2 complexes revealed that there is comparable coverage of LOQS and R2D2 peptides12. Therefore, LOQS is a component of both miRNA and RNAi pathways.

Endo-siRNA biogenesis: open questions

The recent papers on endo-siRNAs raise fundamental questions regarding the biogenesis of small RNAs. Some of the most important questions concern mechanistic aspects of small-RNA sorting pathways. For example, how does LOQS work with DCR2? And given that R2D2 is needed to load exosiRNAs into AGO2 (REFS 43,44), to what extent do endo-siRNAs require R2D2 for loading? How are miRNA and hpRNA precursors distinguished? Some ‘long’ miRNAs and ‘short’ hpRNAs in D. melanogaster are indistinguishable in size and structure10,42. They are effectively sorted, however, as long miRNAs make only a single small-RNA duplex (as is typical for DCR1 substrates), whereas short hpRNAs produce multiple duplexes (as is typical for DCR2 substrates). How can the cell distinguish these hairpins?

The regulation of dsRNA formation is another mystery. For example, the cis-NAT-siRNA pathway accepts many substrates — at least 17 in mouse oocytes6,7 and at least 140 in D. melanogaster8,9,12. However, cis-NAT-siRNA loci constitute only 25% of co-expressed cis-NATs in D. melanogaster9. Is there active selection for entry into the RNAi pathway, which could be mediated at the step of dsRNA formation? Conversely, how do co-expressed mammalian cis-NATs, and co-expressed pseudogene-gene complementary pairs, avoid triggering an interferon response outside of oocytes? Finally, although it seems evident that cis-NAT and trans-NAT siRNAs are generated from processed transcripts, it is not known whether the dsRNA substrate forms in the nucleus or cytoplasm, nor is it clear where the dsRNA encounters Dicer.

Valuable lessons were taught by the length and structure of primary hpRNA transcripts. Their dsRNA character was recognized only after genomic fragments of sufficient length were examined, and consequently their siRNAs were prone to being misannotated as having derived from shorter, unstructured precursors8. The stems of some plant miRNA hairpins are separated by long, unstructured terminal loops and even introns54, and we now recognize the same to be true for several hpRNAs10,12. It is therefore conceivable that the stems of some hpRNA precursors might be separated by kilobases or tens of kilobases. Do the structured precursors of any anonymous cloned small RNAs that are currently deposited in public databases await discovery?

Endogenous sources of mammalian dsRNA remain to be recognized outside of oocytes. As is the case with oocytes, introduction of long dsRNA into embryonic stem cells (ESCs) does not activate an interferon response55,56. Might ESCs also harbour endo-siRNAs, the action of which is relevant for maintaining pluripotency? Although endo-siRNAs were not previously found in ESCs57 this possibility might deserve further study.

Finally, although small-RNA sorting pathways have received little attention in mammalian systems, there is growing recognition of their importance to siRNA and miRNA function in plants58,59, worms60,61 and flies51,62. As only one of the four mammalian AGO proteins (AGO2) has slicer activity16,17, the directed sorting of mammalian siRNAs is presumably important for their ability to slice complementary targets63. Consequently, the elucidation of mammalian siRNA sorting rules might have important implications for attempts to improve siRNA efficacy for experimental and therapeutic purposes.

The biology of endo-siRNAs

To return to the question posed at the beginning of this Perspective, what good is endogenous RNAi to an organism? The necessity to preserve RNAi in mammals has been somewhat of an enigma as they seem to have mostly dispensed with siRNAs for antiviral defence, and some aspects of mammalian biology can be rescued by slicer-defective AGO2 (REF. 64). However, in addition to a few endogenous cleavage targets of miRNAs65, and a role for AGO2 in the biogenesis of select miRNAs66, the new studies suggest widespread usage of endo-siRNAs as endogenous regulators of gene expression.

However, it is safe to say that we do not understand the specific biological functions of endo-siRNAs well. Indeed, the question of endo-siRNA function remains mostly unanswered in worms22,67,68, and the discovery of abundant endo-siRNAs in flies and mammals only makes the understanding of this topic more pressing. The recent papers do show deregulation of retrotransposon transcripts, pseudogene-complementary transcripts and some cis-NAT pairs in Dicer and/or Ago mutants, and thus their regulation by endo-siRNAs is plausible, although this remains to be shown directly Evidence for direct siRNA-mediated target regulation was only explicitly shown for some hpRNAs in D. melanogaster10,12, and such evidence would be desirable for other classes of endo-siRNAs.

The established targets of D. melanogaster hpRNAs encode DNA-binding proteins10,12. This seems reminiscent of the fact that D. melanogaster cis-NAT-siRNA loci are significantly enriched for DNA and RNA-binding proteins9, raising this as a substantial molecular axis for endo-siRNA regulation. It is relevant to note, therefore, that D. melanogaster Dcr2 mutants exhibit abnormal nucleolar morphology69, whereas Ago2 mutants were reported to have chromosome segregation defects70. These phenotypes are plausibly connected to the types of gene functions that are highly enriched in cis-NAT-siRNAs. The mouse oocyte pseudogene-gene siRNA system seems to preferentially target genes that are involved in microtubule dynamics6, and this is plausibly connected to the observation that Dicer loss in growing oocytes disrupts spindle formation and chromosome segregation35,71. Nevertheless, the endogenous requirement of these systems remains to be demonstrated by specific knockouts of hpRNAs or siRNA-generating pseudogenes.

Overall, the fact that core RNAi pathway mutants in worms and flies are mostly normal and fertile, whereas core miRNA pathway mutants are lethal, suggests that the role of endogenous RNAi is fundamentally different than that of miRNA regulation. This is further suggested by the fact that many miRNAs are deeply conserved but most D. melanogaster hpRNA loci10,12 and most mouse pseudogenes that generate siRNAs6,7 are poorly conserved. We must therefore think more openly about their usage. Is the usage of these RNAs a matter of fine-tuning gene expression, or perhaps a matter of maintaining fitness in an ever-changing environment? Is endogenous RNAi used for robustness in gene regulation, perhaps to canalize traits? Or is it a regulatory mechanism that generates species-specific characters during evolution? These are questions that remain for the future, but given the pace with which the field of endo-siRNAs has recently advanced, we might expect some answers to soon be forthcoming.

DATABASES

Entrez Gene: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=gene

Hdacl | klar | mus308 | Rangap1 | tkv

UniProtKB: http://www.uniprot.org

AGO1 | AGQ2 | DCR1 | DCR2 | LOQS | PRG-1 | R2D2

FURTHER INFORMATION

Eric C. Lai’s homepage:

http://www.mskcc.org/mskcc/html/52949.cfm

ALL LINKS ARE ACTIVE IN THE ONLINE PDF

Acknowledgements

K.O. was supported by the Charles Revson Foundation. E.C.L. was supported by the V Foundation for Cancer Research, the Sidney Kimmel Foundation for Cancer Research, the Alfred Bressler Scholars Fund and the National Institutes of Health (GM083300).

References

- 1.Lee YS, et al. Distinct roles for Drosophila Dicer-1 and Dicer-2 in the siRNA/miRNA silencing pathways. Cell. 2004;117:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okamura K, Ishizuka A, Siomi H, Siomi MC. Distinct roles for Argonaute proteins in small RNA-directed RNA cleavage pathways. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1655–1666. doi: 10.1101/gad.1210204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tabara H, et al. The rde-1 gene, RNA interference, and transposon silencing in C. elegans. Cell. 1999;99:123–132. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81644-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabara H, Yigit E, Siomi H, Mello CC. The dsRNA binding protein RDE-4 interacts with RDE-1, DCR-1, and a DExH-box helicase to direct RNAi in C. elegans. Cell. 2002;109:861–871. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00793-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding SW, Voinnet O. Antiviral immunity directed by small RNAs. Cell. 2007;130:413–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tam OH, et al. Pseudogene-derived small interfering RNAs regulate gene expression in mouse oocytes. Nature. 2008;453:534–538. doi: 10.1038/nature06904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe T, et al. Endogenous siRNAs from naturally formed dsRNAs regulate transcripts in mouse oocytes. Nature. 2008;453:539–543. doi: 10.1038/nature06908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghildiyal M, et al. Endogenous siRNAs derived from transposons and mRNAs in Drosophila somatic cells. Science. 2008;320:1077–1081. doi: 10.1126/science.1157396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okamura K, Balla S, Martin R, Liu N, Lai EC. Two distinct mechanisms generate endogenous siRNAs from bidirectional transcription in Drosophila. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:581–590. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okamura K, et al. The Drosophila hairpin RNA pathway generates endogenous short interfering RNAs. Nature. 2008;453:803–806. doi: 10.1038/nature07015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawamura Y, et al. Drosophila endogenous small RNAs bind to Argonaute2 in somatic cells. Nature. 2008;453:793–797. doi: 10.1038/nature06938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czech B, et al. An endogenous siRNA pathway in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;453:798–802. doi: 10.1038/nature07007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung WJ, Okamura K, Martin R, Lai EC. Endogenous RNA interference provides a somatic defense against Drosophila transposons. Current Biology. 2008;18:795–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farazi TA, Juranek SA, Tuschl T. The growing catalog of small RNAs and their association with distinct Argonaute/Piwi family members. Development. 2008;135:1201–1214. doi: 10.1242/dev.005629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mourelatos Z, et al. miRNPs: a novel class of ribonucleoproteins containing numerous microRNAs. Genes Dev. 2002;16:720–728. doi: 10.1101/gad.974702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu J, et al. Argonaute2 is the catalytic engine of mammalian RNAi. Science. 2004;305:1437–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.1102513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meister G, et al. Human Argonaute2 mediates RNA cleavage targeted by mi RNAs and siRNAs. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saito K, et al. Specific association of Piwi with rasiRNAs derived from retrotransposon and heterochromatic regions in the Drosophila genome. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2214–2222. doi: 10.1101/gad.1454806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunawardane LS, et al. A slicer-mediated mechanism for repeat-associated siRNA 5′ end formation in Drosophila. Science. 2007;315:1587–1590. doi: 10.1126/science.1140494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau NC, et al. Characterization of the piRNA complex from rat testes. Science. 2006;313:363–367. doi: 10.1126/science.1130164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brennecke J, et al. Discrete small RNA-generating loci as master regulators of transposon activity in Drosophila. Cell. 2007;128:1089–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruby JG, et al. Large-scale sequencing reveals 21 U-RNAs and additional microRNAs and endogenous siRNAs in C. elegans. Cell. 2006;127:1193–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pak J, Fire A. Distinct populations of primary and secondary effectors during RNAi in C. elegans. Science. 2007;315:241–244. doi: 10.1126/science.1132839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sijen T, Steiner FA, Thijssen KL, Plasterk RH. Secondary siRNAs result from unprimed RNA synthesis and form a distinct class. Science. 2007;315:244–247. doi: 10.1126/science.1136699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yigit E, et al. Analysis of the C. elegans Argonaute family reveals that distinct Argonautes act sequentially during RNAi. Cell. 2006;127:747–757. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang G, Reinke VA. C. elegans Piwi, PRG-1, regulates 21 U-RNAs during spermatogenesis. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:861–867. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Batista PJ, et al. PRG-1 and 21 U-RNAs interact to form the piRNA complex required for fertility in C. elegans. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das PP, et al. Piwi and piRNAs act upstream of an endogenous siRNA pathway to suppress Tc3 transposon mobility in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aravin AA, Hannon GJ, Brennecke J. The Piwi-piRNA pathway provides an adaptive defense in the transposon arms race. Science. 2007;318:761–764. doi: 10.1126/science.1146484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ketting RF, Haverkamp TH, van Luenen HG, Plasterk RH. Mut-7 of C. elegans, required for transposon silencing and RNA interference, is a homolog of Werner syndrome helicase and RNaseD. Cell. 1999;99:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81645-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sijen T, Plasterk RH. Transposon silencing in the Caenorhabditis elegans germ line by natural RNAi. Nature. 2003;426:310–314. doi: 10.1038/nature02107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, et al. Mili, a mammalian member of piwi family gene, is essential for spermatogenesis. Development. 2004;131:839–849. doi: 10.1242/dev.00973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carmell MA, et al. MIWI2 is essential for spermatogenesis and repression of transposons in the mouse male germline. Dev. Cell. 2007;12:503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng W, Lin H. miwi, a murine homolog of piwi, encodes a cytoplasmic protein essential for spermatogenesis. Dev. Cell. 2002;2:819–830. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murchison EP, et al. Critical roles for Dicer in the female germline. Genes Dev. 2007;21:682–693. doi: 10.1101/gad.1521307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Svoboda P, et al. RNAi and expression of retrotransposons MuERV-L and IAP in preimplantation mouse embryos. Dev. Biol. 2004;269:276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe T, et al. Identification and characterization of two novel classes of small RNAs in the mouse germline: retrotransposon-derived siRNAs in oocytes and germline small RNAs in testes. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1732–1743. doi: 10.1101/gad.1425706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang N, Kazazian HH., Jr L1 retrotransposition is suppressed by endogenously encoded small interfering RNAs in human cultured cells. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:763–771. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Svoboda P, Stein P, Hayashi H, Schultz RM. Selective reduction of dormant maternal mRNAs in mouse oocytes by RNA interference. Development. 2000;127:4147–4156. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stein P, Zeng F, Pan H, Schultz RM. Absence of non-specific effects of RNA interference triggered by long double-stranded RNA in mouse oocytes. Dev. Biol. 2005;286:464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reinhart BJ, Weinstein EG, Rhoades MW, Bartel B, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs in plants. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1616–1626. doi: 10.1101/gad.1004402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruby JG, et al. Evolution, biogenesis, expression, and target predictions of a substantially expanded set of Drosophila microRNAs. Genome Res. 2007;17:1850–1864. doi: 10.1101/gr.6597907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Q, et al. R2D2, a bridge between the initiation and effector steps of the Drosophila RNAi pathway. Science. 2003;301:1921–1925. doi: 10.1126/science.1088710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomari Y, Matranga C, Haley B, Martinez N, Zamore PD. A protein sensor for siRNA asymmetry. Science. 2004;306:1377–1380. doi: 10.1126/science.1102755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang F, et al. Dicer-1 and R3D1 -L catalyze microRNA maturation in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1674–1679. doi: 10.1101/gad.1334005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Forstemann K, et al. Normal microRNA maturation and germ-line stem cell maintenance requires Loquacious, a double-stranded RNA-binding domain protein. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saito K, Ishizuka A, Siomi H, Siomi MC. Processing of pre-microRNAs by the Dicer-1 -Loquacious complex in Drosophila cells. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kalidas S, et al. Drosophila R2D2 mediates follicle formation in somatic tissues through interactions with Dicer-1. Mech. Dev. 2008;125:475–485. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meyer WJ, et al. Overlapping functions of argonaute proteins in patterning and morphogenesis of Drosophila embryos. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:el34. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seitz H, Ghildiyal M, Zamore PD. Argonaute loading improves the 5′ precision of both microRNAs and their miRNA strands in flies. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Forstemann K, Horwich MD, Wee L, Tomari Y, Zamore PD. Drosophila microRNAs are sorted into functionally distinct argonaute complexes after production by dicer-1. Cell. 2007;130:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horwich MD, et al. The Drosophila RNA methyltransferase, DmHen 1, modifies germline piRNAs and single-stranded siRNAs in RISC. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:1265–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu X, et al. Dicer-1, but not Loquacious, is critical for assembly of miRNA-induced silencing complexes. RNA. 2007;13:2324–2329. doi: 10.1261/rna.723707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sunkar R, Girke T, Jain PK, Zhu JK. Cloning and characterization of microRNAs from rice. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1397–1411. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paddison PJ, Caudy AA, Hannon GJ. Stable suppression of gene expression by RNAi in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1443–1448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032652399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang S, Tutton S, Pierce E, Yoon K. Specific double-stranded RNA interference in undifferentiated mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:7807–7816. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.22.7807-7816.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Calabrese JM, Seila AC, Yeo GW, Sharp PA. RNA sequence analysis defines Dicer’s role in mouse embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:18097–18102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709193104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mi S, et al. Sorting of small RNAs into Arabidopsis argonaute complexes is directed by the 5′ terminal nucleotide. Cell. 2008;133:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Montgomery TA, et al. Specificity of ARGONAUTE7-miR390 interaction and dual functionality in TAS3 trans-acting siRNA formation. Cell. 2008;133:128–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jannot G, Boisvert ME, Banville IH, Simard MJ. Two molecular features contribute to the Argonaute specificity for the microRNA and RNAi pathways in C. elegans. RNA. 2008;14:829–835. doi: 10.1261/rna.901908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steiner FA, et al. Structural features of small RNA precursors determine Argonaute loading in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:927–933. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tomari Y, Du T, Zamore PD. Sorting of Drosophila small silencing RNAs. Cell. 2007;130:299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Azuma-Mukai A, et al. Characterization of endogenous human Argonautes and their miRNA partners in RNA silencing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:7964–7969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800334105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.O’Carroll D, et al. A slicer-independent role for Argonaute 2 in hematopoiesis and the microRNA pathway. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1999–2004. doi: 10.1101/gad.1565607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yekta S, Shih IH, Bartel DP. MicroRNA-directed cleavage of HOXB8 mRNA. Science. 2004;304:594–596. doi: 10.1126/science.1097434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Diederichs S, Haber DA. Dual role for argonautes in microRNA processing and posttranscriptional regulation of microRNA expression. Cell. 2007;131:1097–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spike CA, Bader J, Reinke V, Strome S. DEPS-1 promotes P-granule assembly and RNA interference in C. elegans germ cells. Development. 2008;135:983–993. doi: 10.1242/dev.015552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grishok A, Sharp PA. Negative regulation of nuclear divisions in Caenorhabditis elegans by retinoblastoma and RNA interference-related genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17360–17365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508989102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peng JC, Karpen GH. H3K9 methylation and RNA interference regulate nucleolar organization and repeated DNA stability. Nature Cell Biol. 2007;9:25–35. doi: 10.1038/ncb1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Deshpande G, Calhoun G, Schedl P. Drosophila argonaute-2 is required early in embryogenesis for the assembly of centric/centromeric heterochromatin, nuclear division, nuclear migration, and germ-cell formation. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1680–1685. doi: 10.1101/gad.1316805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tang F, et al. Maternal microRNAs are essential for mouse zygotic development. Genes Dev. 2007;21:644–648. doi: 10.1101/gad.418707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]