Abstract

We evaluated two putative moderators of treatment outcome as well as the role of Headache Management Self-Efficacy (HMSE) in mediating treatment outcomes in the drug and non-drug treatment of chronic tension-type headache (CTTH). Subjects were 169 participants (M = 38 yrs.; 77% female; M headache days/mo. = 22) who received one of four treatments in the treatment of CTTH trial (JAMA, 2001; 285: 2208-15): tricyclic antidepressant medication, placebo, (cognitive-behavioral) stress-management therapy plus placebo, and stress-management therapy plus antidepressant medication. Severity of CTTH disorder and the presence of a psychiatric (mood or anxiety) disorder were found to moderate outcomes obtained with the three active treatments and with placebo, as well as to moderate the role of HMSE in mediating improvements. Both moderator effects appeared to reflect the differing influence of the moderator variable on each of the three active treatments, as well as the fact that the moderator variables exerted the opposite effect on placebo than on the active treatments. HMSE mediated treatment outcomes in the two stress management conditions, but the pattern of HMSE mediation was complex, varying with the treatment condition, the outcome measure, and the moderator variable. Irrespective of the severity of the CTTH disorder HMSE fully mediated observed improvements in headache activity in the two stress management conditions. However, for patients with a mood or anxiety disorder HMSE only partially mediated improvements in headache disability, suggesting an additional therapeutic mechanism is required to explain observed improvements in headache disability in the two stress management conditions.

Keywords: clinical trial, chronic tension-type headache, moderator, mediator, stress-management therapy, antidepressant medication

Tricyclic antidepressants are the primary drug therapy for chronic tension-type headache, with amitriptyline hydrochloride the first-line treatment [2, 5, 15, 50, 61, 71, 74]. Cognitive-behavioral stress-management therapy is also effective in managing tension-type headache, and when compared to relaxation and biofeedback therapies appears more effective [9, 11, 27, 79]. The Treatment of Chronic Tension-type Headache (TCTH) trial reported that, relative to placebo, brief cognitive-behavioral stress-management therapy, tricyclic antidepressant medication, and their combination proved equally effective in improving chronic tension-type headaches and reducing headache-related disability, with improvements occurring most rapidly in the two groups that received antidepressant medication [37]. However, at month eight the primary endpoint, the proportion of participants clinically improved (≥ 50% reduction in headache activity) was greater with the combined treatment (64%) than with either antidepressant medication alone (35%) or stress-management therapy alone (38%).

Clinical trials can provide information about moderator effects, or relationships between patient characteristics and treatment response, in addition to information about overall treatment effects [49]. This information can guide efforts to match patients with the most effective treatment and efforts to develop more effective treatments for unresponsive subpopulations of patients [49]. In the clinical literature, two patient characteristics that may influence outcomes in the treatment of chronic tension-type headache have been identified: (1) severity of chronic tension-type headache disorder, loosely defined by a greater number of days with headaches, as well as by greater headache severity or impairment in function, and (2) the presence of a co-morbid mood or anxiety disorder [3, 7, 12, 25, 28, 32, 34, 51, 55, 62, 65]. To our knowledge, neither variable has been formally examined as a moderator for the tricyclic antidepressant medication and cognitive-behavioral stress-management therapies that appear to be the primary drug and psychological treatments for chronic tension-type headache.

Clinical trials also can provide information about mediator effects, or therapeutic mechanisms that lead to improvement. This information can guide efforts to develop more powerful and efficient treatments, or efforts to identify likely treatment failures early in treatment before failure actually occurs. Research conducted with EMG biofeedback therapy and with relaxation therapy suggests confidence (perceived self-efficacy) in one's ability to use headache management skills may mediate the improvements in headache activity that are observed with behavioral treatments [10, 12, 29, 35, 38, 64, 70]. However, in the presence of moderator effects mediation may vary with the level of the moderator variable. For example, when a mood or anxiety disorder is present, not only headache management self-efficacy, but also reductions in affective distress or other therapeutic mechanisms may play a role in mediating improvements obtained with behavioral treatments [33, 36].

The present report examines demographic variables, psychiatric diagnosis and severity of CTTH disorder as moderators of response to the three active treatments and to placebo in the TCTH trial. In addition, change in self-efficacy induced by treatment is examined as a mediator, or therapeutic mechanism, in cognitive-behavioral stress-management therapy.

Method

TCTH Trial Design

This trial compared four treatments for chronic tension-type headaches in a randomized (N = 203) parallel group design: tricyclic antidepressant medication (AM), placebo (PL), cognitive-behavioral stress-management therapy plus placebo (SMT + PL), and stress-management therapy plus antidepressant medication (SMT + AM). It can be seen in Figure 1 that the TCTH trial included a baseline assessment phase of at least one-month duration, a two-month treatment/dose adjustment phase, in which stress-management therapy was administered and the antidepressant medication dose was adjusted (M1-2), and a 6-month evaluation period (M3-8). The 3 clinic visits and 2 scheduled telephone contacts during the treatment/dose adjustment phase (M1-2) were used for both AM/PL dose adjustment and administration of SMT. The evaluation phase (M3-8), required 3 clinic visits at M3, M5 and M8. Evaluations at the M3 and M8 clinic visits included 1 month of daily headache diaries, neurological evaluation and completion of psychological tests. The M5 clinic visit was primarily a medication check.

Figure 1.

Three trial phases: baseline, treatment (administration of stress-management therapy and antidepressant medication/placebo dose adjustment), and evaluation.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were age between 18 and 65 years and International Classification of Headache Disorders-2 [ICHD-2; 24] diagnosis of chronic tension-type headache at separate evaluations by a neurologist and by a second evaluator. Tension-type headaches often occur every day or nearly every day in individuals who seek treatment [33, 45, 46, 71], but headaches must occur 15 or more days per month for at least 6 months to meet International Headache Society diagnostic criteria for chronic rather than episodic, tension-type headache [24]. Exclusion criteria included: ICHD diagnosis of medication overuse headache [24], current use of prophylactic medication for tension-type headache; migraine headache more than 1 day per month; pain problem (e.g., arthritis) other than headache as primary presenting problem (see Holroyd et al., 2001 for complete details [37]).

A total of 203 participants (48 PL, 53 AM, 49 SMT + PL, and 53 SMT + AM) were initially enrolled, and 169 participants (38 PL, 48 AM, 38 SMT + PL, and 45 SMT + AM) completed the treatment/dose adjustment phase. Because we were interested in moderators and mediators of treatment effects, the 169 participants who received treatment, that is, completed the treatment/dose adjustment phase were used in all analyses. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. The CONSORT participant flow diagram can be found in the original trial report [37].

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics

| Placebo n = 38 |

AM n = 48 |

SMT + Placebo n = 38 |

SMT + AM n = 45 |

p* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age | 38.6 | 13.5 | 36.3 | 11.2 | 39.6 | 12.0 | 37.5 | 12.6 | 0.65 |

| Headache Activity | 2.4 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 3.0 | 1.4 | 0.26 |

| Headache Days/30 days | 21.8 | 6.5 | 23.5 | 6.5 | 22.2 | 6.6 | 22.4 | 6.9 | 0.66 |

| Moderate Severity Days/30 days | 12.5 | 7.0 | 14.4 | 8.3 | 12.0 | 7.5 | 13.4 | 8.6 | 0.52 |

| Headache Disability (HDI) | 34.1 | 13.9 | 40.0 | 19.3 | 39.3 | 22.2 | 40.3 | 18.7 | 0.54 |

| Severity of CTTH Disorder | 2.6 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 0.54 |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Female | 29 | 76 | 31 | 65 | 29 | 76 | 36 | 80 | 0.35 |

| Income Level US$* | |||||||||

| 0 – 30 000 | 6 | 9.2 | 14 | 21.6 | 3 | 4.6 | 7 | 10.8 |  |

| 30 001 – 45 000 | 12 | 18.5 | 11 | 16.9 | 13 | 20.0 | 17 | 26.9 | |

| 45 001 – 60 000 | 4 | 6.2 | 7 | 61.6 | 7 | 10.8 | 7 | 10.8 | |

| >60 000 | 10 | 15.4 | 16 | 24.6 | 12 | 18.5 | 8 | 12.3 | |

| Only Mood Disorder | 10 | 26 | 17 | 35 | 11 | 29 | 10 | 22 | 0.92 |

| Only Anxiety Disorder | 10 | 26 | 17 | 35 | 11 | 29 | 18 | 40 | 0.54 |

| Both Mood and Anxiety Disorder | 7 | 18 | 10 | 21 | 5 | 13 | 6 | 13 | 0.79 |

Note: AM = antidepressant medication, SMT = stress management, HDI = Headache Disability Inventory. Headache activity (M0) = headache index calculated for second half of pretreatment recording period. Severity of CTTH disorder (moderator) = headache index calculated for first half of pretreatment recording period. Psychiatric Diagnosis obtained from PRIME-MD Diagnostic Interview. ANOVA test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for dichotomous variables.

154 participants provided income information.

The 34 participants who did not receive treatment and the 169 participants who did receive treatment did not differ on the primary headache variables (baseline headache activity, headache days, or headache days with a pain rating ≥ 5, or the moderator variable, severity of CTTH disorder), on headache disability, or on the presence of a mood or anxiety disorder. Considering demographic variables, participants who received treatment were older (37.9 ±0.94 yrs.) than participants who did not receive treatment (32.2±1.70 yrs.), t(202)=2.6, p=.011, but the two groups did not differ in the proportion of females, or in income.

A total of 126 participants completed the M8 evaluation (26 PL, 44 AM, 34 SMT + PL, and 40 SMT+ AM). The 25 dropouts during the 6 month evaluation phase did not differ from the 144 participants who completed the M8 evaluation on any variable in Table 1. However, 12 (32%) of 38 participants receiving PL but only 13 (11%) of 118 participants receiving active treatment discontinued their treatment prior to the M8 evaluation, χ2(1)=11.0, p<.001. This difference reflected the higher level of treatment discontinuation because of a lack of treatment response in the PL group: 8 (21%) of 38 participants in the PL group, but only 3 (3%) of 131 participants than in the active treatment groups discontinued treatment due to a lack of treatment response, χ2(1)= 17.0, p < .001. As was noted in the original trial report [37] “…it is probably not surprising that participants seeking relief from daily headaches requested alternate treatment before they went 8 months without relief” (p. 2214).

Treatments

Antidepressant medication/placebo

Treatment was administered by board certified neurologists with special interest in headache. The three dose adjustment visits and two scheduled phone calls were used both for AM dose-adjustment, and to identify and correct adherence problems that might undermine the effectiveness of AM therapy [37, 66, 68]. This adherence intervention was modeled after Peveler [66]. Written handouts provided information about the medication schedule, and common ways to facilitate adherence (e.g., establishing reminder cues). During the week 3 and 7 phone contacts, adherence was assessed and an effort was made to address the source of any adherence problems that were identified. For example, a bothersome side effect might be addressed with information (e.g., side-effect is harmless, likely to diminish with time), with ameliorating interventions such as chewing sugarless gum to minimize dry mouth, and with a dose-adjustment when necessary.

The double-blind AM protocol attempted to maximize the efficacy and tolerability of AM by beginning medication one (amitriptyline hydrochloride, or matched placebo) at a low dose (12.5 mg amitriptyline), providing a second medication option (nortriptyline hydrochloride, or matched nortriptyline placebo) for participants who failed to tolerate medication one, dosing to the recommended dose levels for the treatment of chronic tension-type headache (75-100 mg amitriptyline, or equivalent matched placebo, or 50-75 mg nortriptyline, or equivalent matched nortriptyline placebo) or to tolerance, and incorporating an adherence intervention [2, 5, 15, 37, 50, 61, 71, 75]. Details of the protocol including the dosing schedule, final dose levels and adherence information can be found in Holroyd et al. [37].

Stress-management

A psychologist or masters level counselor administered SMT in three 1-hour sessions at the same 3 clinic visits used for medication dose adjustments. This primarily home-based treatment teaches both relaxation and cognitive coping skills for preventing and managing stress and headaches [32, 54]. For participants receiving SMT the week 3 and 7 phone contacts were used to identify and correct problems encountered in the application of behavioral headache management skills [54], as well as for the medication adherence intervention.

In the first clinic session, the SMT manuals (9 chapters; 64 pages) and 8 accompanying audiotapes [30] that guide the acquisition and application of stress and headache management skills at home were reviewed. Muscle stretching exercises (head, neck & shoulders) were demonstrated, and progressive muscle relaxation training initiated, using 16 muscle groups [6]. SMT manuals and audiotapes for the next 4 weeks guided the progression from using 16 muscle groups to brief muscle relaxation (e.g., 4 muscle groups), to rapid (e.g., cue-controlled) relaxation techniques [6], and, finally, to application of these “quick relaxation” skills during daily activities. Barriers to learning relaxation skills and using of relaxation skills were addressed both in home study materials, and in the week 3 phone call [54]. At the second treatment session, active cognitive coping [54] and/or problem solving [16, 17] techniques for preventing and managing headache-related stresses were introduced. Daily diaries were reviewed to identify stressful situations, emphasizing stressors associated with the onset of headaches or stressors that appeared to aggravate, or maintain headaches. A hierarchy of stressors was created and a stressful situation that could reasonably be addressed in brief treatment was identified. A cognitive target was then identified, that is, stress-generating thoughts, and underlying stress generating beliefs that distilled meaning from many stress-generating thoughts. Multiple techniques were then be used to cope with the identified stress-generating thoughts and beliefs, including behavioral experiments, role play, rehearsal in imagination, and verbal cognitive therapy techniques.[4, 54]. SMT manuals and audiotapes for the second 4 weeks guided the development of cognitive stress management skills and the application of these skills, to progressively more difficult stressors, as appropriate. The week 7 phone contact attempted to resolve any problems that had arisen in the application of stress-management skills. At the third treatment session, the application of relaxation and cognitive coping skills that had already been introduced to pain management was reviewed. The participant's experience with headache management skills in the previous 2 months was reviewed and an appropriate headache management plan formulated. It was emphasized in the SMT manual and in clinic contacts that headache management skills would likely need to be applied for a number of months before improvement in daily, or near daily headaches would be observed. Details of this treatment can be found in Lipchik et al. [54].

Measures

Daily headache diary recordings (headache index) and the Headache Disability Inventory scores provided measures of the primary headache activity and quality-of-life outcomes.

Headache Diary

Participants recorded headaches and the use of analgesic and trial medication in a daily diary [37]. Headache activity was recorded four times a day using an 11-point scale with 5 anchors that ranged from 0, which indicated no pain, to 10, which indicated extremely painful or “I can't do anything when I have a headache” The headache index, the mean of all diary ratings (including 0s) provides a measure of overall headache activity or burden, taking into account both pain severity and duration. As the preferred measure of chronic tension type headache activity the headache index was the primary outcome measure for the trial [37]. Headache diary recordings were obtained during a 1-month pretreatment phase, during the 2-month treatment/dose adjustment phase (M1-2) and in the first and last month of the 6-month evaluation period (M3 and M8). Baseline (M0) headache index was calculated from the second half of the one month pretreatment recording period; this allowed the moderator variable (severity of CTTH disorder) to be calculated from the first half of the pretreatment headache recording period (see below). Secondary headache measures, used for descriptive purposes and for sensitivity analysis, were the number of headache days per month and the number of headache days per month where pain was of sufficient severity to impair functioning (pain rating ≥ 5).

Headache Disability Inventory

The Headache Disability Inventory [HDI; 40] was designed to assess “the burden of chronic headaches” using 25 items that inquire about the perceived impact of headaches on emotional functioning (e.g., “I feel desperate because of my headaches”) and daily activities (e.g., “Because of my headaches I am less likely to socialize”). Items were designed specifically to assess the concerns of individuals with recurrent headache disorders. The HDI appears to exhibit reasonable short-term (one week, .93-.95) and longer-term (two month, r = .76-.83) stability, and patient reports on the HDI appear to be reasonably congruent with spouse reports [42, 43]. The HDI has the advantage of assessing the impact of headaches on both affect and functioning [43]. Scores range from 0 to 100. The HDI was assessed at baseline (M0) and in the first and last month of the 6-month evaluation period (M3, M8).

Psychiatric Diagnosis

The Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders [PRIME-MD; 76, 77] is designed to facilitate the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders commonly seen in medical settings. It includes a patient-completed questionnaire of key symptoms and a clinician-administered structured interview (Clinician Evaluation Guide) that yields a subset of diagnoses in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM-IV; 76]. Psychologists administered the structured diagnostic interview to all participants and queried participants as necessary to diagnose the most commonly encountered mood (Major Depressive Disorder, Dysthymia and Minor Depressive Disorder) and anxiety disorders (Panic Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Anxiety Disorder Not Otherwise Specified), using the PRIME-MD Mood and Anxiety Disorder Modules. The PRIME-MD was chosen because it was designed for use by physicians in primary care where most headache problems are treated. This increases the likelihood any findings obtained with the PRIME-MD could be applied in the primary care setting.

Self-Efficacy

The Headache Management Self-Efficacy Scale [HMSES; 21] consists of 25 items that inquire about individual's confidence in their abilities to prevent headache episodes (e.g., “I can prevent headaches by changing how I respond to stress”) and to manage headaches (“I can do things that will control how long a headache lasts”). The HMSES has good internal consistency and construct validity. For example, self-efficacy is positively correlated with the use of active coping strategies for both preventing and managing headaches and explains variance in headache-related disability beyond that explained by headache severity or other related cognitive constructs such as headache locus of control [21]. HMSES assessed at baseline (M0) and at the final treatment/dose adjustment visit (M2) was used in for the mediator analysis.

Statistics

First we determined if demographic and headache characteristics were equivalent across the four treatment groups. ANOVA tests were used for the examination of continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher's exact tests were used for the examination of categorical variables.

Moderator analysis

Patient characteristics may predict treatment response, that is, identify individuals who are less responsive or more responsive to any intervention, or moderate treatment response, that is, identify individuals for whom one intervention, for example, combined drug and psychological therapy, is more effective than other interventions (13). Severity of chronic tension-type headache disorder and the presence of psychiatric co-morbidity (PRIME-MD mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis) were examined as possible moderators of improvements observed with the four treatments over the eight-month treatment period. Possibly the best measure of the overall severity of a chronic tension-type headache disorder (the moderator variable) is provided by the headache index calculated from daily diary recordings. We noted above that the headache index is also the preferred measure of headache activity for assessing improvements in chronic tension tension-type headaches. Headache index was thus used to assess both severity of CTTH disorder (a moderator variable) and headache activity, the primary outcome. Severity of CTTH disorder (the moderator) was assessed by the headache index calculated over the first half of the one month pretreatment recording period. Baseline (M0) headache activity (baseline for the primary outcome measure) was assessed by the headache index calculated over the second half of the one month pretreatment recording period. Periods as short as one week provide a reliable baseline measure of chronic tension-type headache activity [1, 8] allowing the one month pretreatment assessment period to be divided in this manner. It is important to keep in mind that a moderator does not simply “predict” treatment outcome (as is commonly the case when a baseline value is used as a covariate in examining treatment effects), but it is the moderator × treatment × time interaction that is being tested—the moderator predicts differences in the relative effectiveness of the 4 treatments (i.e. slopes); the relative magnitude of slopes vary depending on the level of the moderator variable.

While the above measure is the preferred measure of CTTH disorder severity, for sensitivity analysis we also calculated an alternative measure of this moderator variable (CTTH disorder severity2) from the two other available headache measures as follows: [(Headache days - Headache days pain rating ≥ 5) × 2.5 + (Headache days pain rating ≥ 5 × 7.5)]. CTTH disorder severity2 is inferior to CTTH disorder severity because: (1) only one broad pain rating category is available for each headache day (compared to 3 participant pain rating for the headache index), and (2) pain ratings are set at the same arbitrarily midpoint for every participant (i.e. 2.5 for headache days with pain rating < 5 and 7.5 for headache days with pain rating ≥ 5), while CTTH disorder severity uses each participants' actual pain ratings. However, this second measure undoubtedly better captures CTTH disorder severity than either of its components alone, and allowed us to determine if any observed moderator effect is robust across different measures of CTTH disorder severity.

Mixed-effects analyses implemented with the Proc Mixed procedure in SAS (v. 9.1) were used to examine moderator effects [22, 59, 63]. In each instance a first-order autoregressive model with a random effect for subject [AR(1)+RE] yielded the best fit among the commonly used covariance structures as indicated by Akaike's Information Criteria (AIC). Moderator effects were examined on the two primary trial outcomes: headache activity (headache index) and headache disability (Headache Disability Inventory scores) using a general linear mixed model (GLMM). Because the time variable (month) was quantitative and trial outcomes improved in a curvilinear fashion over time, we modeled headache activity and headache disability as polynomial functions of time. Specifically, for each candidate moderator variable a mixed-effects analysis employing sequential sums of squares was applied to test a completely saturated model that included the main effects of the candidate moderator variable and treatment followed by the main effect (linear and quadratic components) of the moderator on treatment over time. A significant interaction involving the moderator variable indicates that the trajectory of treatment response differs across treatment conditions and depends on the level of the moderator variable. For each test of moderation the alpha was adjusted for the two outcome variables (p < .025).

Moderator effects were examined graphically by displaying parameter estimates and 95% normal confidence intervals for High (+ 1 SD above the Mean), Moderate (Mean) and Low (- 1 SD below the Mean) values for severity of CTTH disorder, a continuous variable, and for both levels of psychiatric diagnosis, a dichotomous variable. We also examined treatment effect sizes (Cohen's d) [14] to elucidate the nature of any moderator effects. By convention d = .20, d = .50, and d = .80 are interpreted as small, moderate and large magnitude effects, respectively [14]. These latter descriptive analyses were viewed as hypothesis generating, rather than hypothesis testing. As Kramer and colleagues[49] note, Type II error is a significant problem in moderation analysis, with even a moderate size clinical trial (< 400 participants) so that “ p values are not and should not be used” (p. 881) to elucidate moderator effects.

Mediation analyses

Mediators are intervening variables that occur or change after treatment but before outcome assessment and explain the mechanisms by which treatment affects outcome [48, 49]. However, in the presence of a moderator effect, mediation may depend upon the value of the moderator. Therefore, where a significant moderator effect was observed, mediation was assessed in the context of moderation by applying moderated mediation analyses [57, 58, 73, 78]. A prospective model specified that the active treatment versus placebo contrast on the outcome (either headache activity or headache disability) at the primary endpoint (M8) was mediated by Headache Management Self-efficacy (HMSE) at the final treatment/dose adjustment visit (M2). The potential effects of relevant baseline values and of the moderator effect were controlled (see Figure 3). AMOS 6.0 was used to conduct full information likelihood estimation [81] with 95% confidence intervals for path regression estimates calculated based the normal distribution. For the indirect effect (HMSE mediation) the standard error was calculated based upon on the first and second derivative of the Taylor series approximation [56]. For this indirect effect a confidence interval that includes zero suggests no mediation effect is present.

Figure 3.

Mood or Anxiety Disorder as Moderator Variable. Predicted treatment outcomes (and 95% confidence intervals) for headache disability when: (A) no mood or anxiety disorder is present, and (B) when a mood anxiety disorder is present.

Results

In Table 1 it can be seen that demographics and clinical characteristics were similar across the four treatment groups at baseline. We next examined whether the demographic characteristics of age or gender moderated treatment effects. Neither variable was found to moderate treatment outcomes (p > .05).

Moderator Effects

Headache activity at M8 as outcome

Only CTTH disorder severity moderated treatment outcome. Headache activity treatment outcomes did not vary with the presence or absence of a mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis (p > .05). However, the linear CTTH Headache Disorder Severity × Treatment × Month, F (3, 222) = 6.2, p < .001, and quadratic CTTH Headache Disorder Severity × Treatment × Month × Month, F(3,552) = 4.8, p =.003, interactions were statistically significant. Sensitivity analysis that substituted our alternative measure of CTTH disorder severity, confirmed this moderator effect, severity of CTTH disorder2 × Treatment × Month, F (3,795) = 4.4, p < .005.

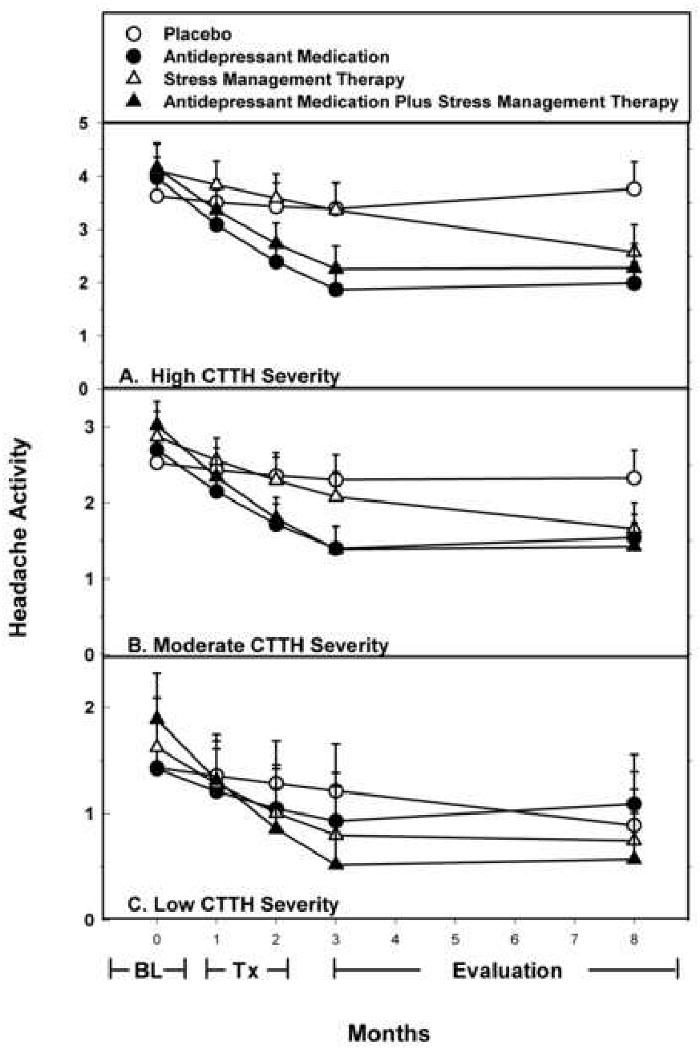

This moderator effect is displayed in Figures 2 A-C, where predicted treatment outcomes and 95% confidence intervals are shown for high, moderate, and low severity CTTH disorders. It can be seen in Figure 2A and 2B that for high and moderate severity CTTH disorders, the three active treatments yielded large treatment effects at M8, though improvements occurred more rapidly in the two AM conditions, than with SMT alone. Treatment effect sizes (Cohen's d) [14] at the primary endpoint (M8) confirmed large treatment effects for both high (AM = -1.7; SMT = - 1.2; AM + SMT = -1.4) and moderate (AM = -1.1, SMT = -.91, AM + SMT = - 1.3) severity CTTH Disorders. In contrast, in Figure 2C it can be seen that for a low severity CTTH disorder treatment effects appeared nonexistent, except possibly for SMT + AM.

Figure 2.

Headache Severity as a Moderator Variable. Predicted treatment outcomes (and 95% confidence intervals) when: (A) severity of CTTH disorder is high (M + 1 SD), (B) severity of CTTH disorder is moderate (M), and (C) severity of CTTH disorder is low (M - 1 SD).

Examination of within group improvements (Cohen's d) suggested this moderator effect resulted from the differing influence of the moderator variable on each of the three active treatments, as well as the fact that the moderator variables had the opposite effect on placebo than on the active treatments. There was no sign of a placebo response when the severity of CTTH disorder was high (d = + .09) or moderate (d = - .18), but a more notable placebo response was observed when the severity of the CTTH disorder was low (d = -.36). In contrast, reductions in headache activity with all three active treatments were large (d > -.80) for high and moderate severity CTTH disorders, but of a similar magnitude (i.e. d > -.80) only for SMT + AM when severity of the CTTH disorder was low. For AM alone and SMT alone the smaller reductions in headache activity observed with low severity CTTH disorders were then similar in magnitude to the larger PL response observed with low severity CTTH disorders.

Headache disability at M8 as outcome

Only a mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis moderated treatment outcome when headache disability was the outcome. The PRIME-MD Diagnosis × Treatment × Month × Month interaction, F (3, 168) = 3.23. p = .02, was statistically significant. Severity of CTTH disorder failed to moderate treatment outcome (p > .05).

It can be seen in Figure 3-B that when a mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis was present, clear treatment effects were observed with all three active treatments at the primary endpoint. Corresponding treatment effect sizes (d) on headache disability were moderate-to-large in magnitude (AM =.-71; SMT = - .1.01; SMT + AM = -.83). In contrast, in Figure 3A it can be seen that, in the absence of a mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis, treatment effects appeared nonexistent, except possibly for SMT + AM.

Examination of within group effect sizes revealed this moderator effect again resulting from the differing influence of the moderator variable on each of the three active treatments, as well as the fact that the moderator variable had the opposite effect on placebo than on the active treatments as a group. No sign of a placebo response was evident when a mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis was present (d = - .01), but a more notable placebo response (d = -.38) was observed in the absence of a mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis. In contrast, with all three active treatments, reductions in headache disability were large (d > -.80) in the presence of a mood or anxiety disorder, but in the absence of a mood or anxiety disorder similarly large reductions in headache disability (i.e. d > - .80) were observed only for SMT + AM. For AM alone and SMT alone the smaller reductions in headache disability observed in the absence of a mood or anxiety disorder were then similar in magnitude to the larger PL response observed in the absence of a mood or anxiety disorder.

Moderated Mediation

Although self-efficacy has been postulated as a therapeutic mechanism exclusively for psychological treatments, the role of self- efficacy as a therapeutic mechanism in combined psychological and drug therapy is of interest, and information about the action self-efficacy as a mediator of treatment outcomes in drug therapy may provide useful comparison data. Therefore, the identical model was evaluated for each of the three active treatments.

Headache activity at M8 as outcome

Figure 4 and Table 2 present the mediator analyses for the primary outcome of headache activity in the context of severity of CTTH disorder, the identified moderator variable. Only coefficients for the paths that are critical for evaluating the hypothesis of HMSE mediation are presented in Table 2; a complete table of all path coefficients is available from the authors. It can be seen in Table 2 that the role of Headache Management Self-Efficacy (HMSE) at M2 in mediating improvements in headache activity at M8 varied with the type of treatment and with the moderator variable, severity of CTTH disorder.

Figure 4.

Moderated mediator analysis evaluating Headache Management Self-efficacy (HMSE) at Month 2 as mediator of treatment outcomes at Month 8. Moderator is severity of CTTH disorder when headache activity is the outcome and psychiatric comorbidity when headache disability is the outcome. a = effect of treatment on HMSE at Month 2; b = effect of HMSE at Month 2 on treatment outcome at Month 8; c = direct effect of treatment (i.e. unmediated by HSME at Month 2) on outcome at Month 8; ab = indirect effect of treatment (i.e. mediated by HMSE at Month 2) on outcome at Month 8. Because of the high correlation (r = .84) between baseline headache activity (outcome M0) and severity of CTTH disorder (the moderator) paths were not adjusted for both these variables when headache activity was the outcome, but only for baseline HMSE (- - - path d) and the identified moderator effects (--- paths f through i) When headache disability was the outcome path estimates adjusted for baseline values (- - - paths d & e) and identified moderator effects (--- d through i).

Table 2.

Does Headache Management Self-Efficacy (HMSE) at Month 2 Mediate Improvement in Headache Index (HI) at Month 8: Path Regression Weights and 95% Confidence Intervals?

| Treatment Contrast | Severity of CTTH Disorder | a | b | c | ab1 | Mediation Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM vs. PL | Low | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mod |

3.81** (0.88, 6.74) |

-0.02*** (-0.03, -0.01) |

-0.33* (-0.61, -0.05) |

-0.08 (-0.15, -0.00) |

Absent | |

| High |

5.32*** (2.40, 8.25) |

-0.02** (-.03, 0.01) |

-0.78*** (-1.06, -0.49) |

-0.11 (-0.21, -0.01) |

Partial 12% | |

| SMT vs. PL | Low | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mod |

14.07*** (10.42, 17.72) |

-0.03*** (-0.04, -0.02) |

0.10 (-0.22, 0.41) |

-0.38 (-0.57, -0.19) |

Full | |

| High |

15.34*** (11.69, 18.99) |

-0.03*** (-0.04, -0.02) |

-0.13 (- 0.45, 0.20) |

-0.41 (-0.62, -0.21) |

Full | |

| AM + SMT vs. PL | Low |

10.50*** (6.74, 14.25) |

-0.03*** (-0.05, -0.02) |

0.14 (-0.20, 0.47) |

-0.34 (-0.52, -0.16) |

Full |

| Mod |

15.58*** (11.82, 19.33) |

-0.03*** (-0.05, -0.02) |

0.10 (-0.28, 0.47) |

-0.50 (-0.74, -0.25) |

Full | |

| High |

20.66*** (16.91, 24.42) |

-0.03*** (-0.05, -0,02) |

0.05 (-0.37, 0.48) |

-0.66 (-0.95, -0.37) |

Full | |

PL = Placebo; = Antidepressant Medication; SMT = Stress-Management Therapy; N/A = No treatment effect to mediate. All path coefficients are unstandardized. a = effect of treatment on HMSE at Month 2; b = effect of HMSE at Month 2 on headache activity at Month 8; c = direct effect of treatment (i.e., unmediated by HMSE at Month 2) on headache activity at Month 8; ab = indirect effect of treatment (i.e., mediated by HMSE at Month 2) on headache activity at Month 8. All path estimates adjusted for baseline HMSE (--- path d) and identified moderator effect (… paths f - i) in Figure 3.

Confidence interval that includes zero suggests the absence of a mediation effect.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

High CTTH disorder severity did not limit the ability of either SMT or SMT + AM to modify HMSE at M2; to the contrary, it can be seen (Table 2) that coefficients for path (a) tended to increase in magnitude with increasing severity of CTTH disorder. At all levels of severity of CTTH disorder, if treatment effects were observed, results for SMT and for SMT + AM were consistent with full mediation [i.e. the path coefficient for the alternate direct path (c) did not differ from 0] of treatment effects observed at M8 by HMSE change at M2 (indirect path ab).

In contrast, HMSE at M2 appeared to play little or no role in improvements observed with AM at M8. The upper bound of the confidence intervals for HMSE mediation (path ab) included zero when severity of CTTH disorder was moderate and approached zero when severity of CTTH disorder was high. Even in the latter case HMSE mediation accounted for only a small proportion (12%) of the total AM treatment effect. These results suggest other therapeutic mechanisms (e.g., path c) than self-efficacy mediation are of primary importance in the AM treatment effect.

Headache disability at M8 as outcome

Figure 4 and Table 3 presents the results of mediator analyses for headache-related disability (Headache Disability Inventory) outcomes in the context of the identified moderator variable: Psychiatric (Mood or Anxiety Disorder) Diagnosis. It can be seen that support for self-efficacy mediation varied with the presence of a mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis as well as with type of treatment.

Table 3.

Does Headache Management Self-Efficacy (HMSE) at Month 2 Mediate Improvement in Headache Disability Inventory (HDI) Scores at Month 8: Path Regression Weights and 95% Confidence Intervals

| Treatment | Anxiety or Mood Disorder | a | b | c | ab1 | Type of Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM vs. PL | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Yes |

7.75** (4.87, 10.63) |

-0.16 (-0.321, 0.00) |

-5.39*** (-8.76, -2.11) |

-1.24 (-2.45, 0.06) |

Absent | |

| SMT vs. PL | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Yes |

21.84*** (18.48, 25.19) |

-0.16* (-0.31, -0.01) |

-6.78** (-11.35, -2.21) |

3.51 (-6.93, -0.21) |

Partial 34% | |

| AM + SMT vs. PL | No |

14.92*** (10.98, 18.86) |

-0.15* (-0.29, -0.01) |

-2.90 (-6.44, 0.63) |

-2.22 (-4.35, -0.09) |

Full |

| Yes |

16.89*** (12.95, 20.83) |

-0.15* (-0.29, -0.01) |

-6.05** (-9.74, -0.01) |

-2.52 (-4.91, -0.13) |

Partial 29% | |

PL = Placebo; AM = Antidepressant Medication; SMT = Stress-Management Therapy. N/A = not applicable; No treatment effect to mediate. All path coefficients are unstandardized. a = effect of treatment on HMSE at Month 2; b = effect of HMSE at Month 2 on Headache Disability (HDI) at Month 8; c = direct effect of treatment (i.e., unmediated by HMSE at Month 2) on Headache Disability (HDI) at Month 8; ab = indirect effect of treatment (i.e., mediated by HMSE at Month 2) on Headache Disability (HDI) at Month 8. All path estimates adjusted for baseline values (--- paths d and e) and identified moderator effect (… paths f - i) in Figure 3.

Confidence interval that includes zero suggests the absence of a mediation effect.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.0001.

Again the presence of a mood or anxiety disorder did not limit the ability of SMT or SMT + AM to modify HMSE at M2; to the contrary, it can be seen in Table 3 that coefficients for path (a) tended, if anything, to be slightly larger when a mood or anxiety disorder was present than absent. However, the presence of a mood or anxiety disorder appeared to reduce the HMSE mediation of improvements in headache disability, at least for SMT + AM. In the absence of a mood or anxiety disorder results for SMT + AM were consistent with full mediation of improvements in headache disability at M8 by HMSE at M2; however, for both SMT and for SMT + AM results suggested only partial mediation when a mood or anxiety disorder was present. HMSE change at M2 accounted for a third or less of the SMT and the SMT + AM treatment effects at M8 when a mood or anxiety disorder was present. This suggests additional therapeutic mechanisms than HMSE change are required to account for improvements in headache disability in the presence of mood or anxiety disorder.

Results for AM alone present a different picture. In the absence of a mood or anxiety disorder there was no antidepressant effect (AM < PL) on headache disability. In the presence of a mood or anxiety disorder there was an AM treatment effect, but the upper bound of the confidence intervals for HMSE mediation (path ab) included zero; in fact, HMSE at M2 appeared to be unrelated to improvements headache disability with AM at M8 (path b) . These results suggest other therapeutic mechanisms (e.g., path c) than self-efficacy mediation are of primary importance in the AM treatment effect.

Discussion

Moderator Effects

Contrary to conventional wisdom the advantage of combined SMT + AM relative to AM alone or to SMT alone did not become apparent as severity of the CTTH disorder increased, or when CTTHs were complicated by a co-morbid mood or anxiety disorder [3, 7, 12, 25, 32, 34, 55, 65]. To the contrary, any advantage for combined SMT + AM was observed with lower severity CTTH disorders, and in the absence of a mood or anxiety disorder.

Improvements in headache activity with the three active treatments were not influenced by the presence or absence of a mood or anxiety disorder. This finding supports the argument that the AM analgesic effect is independent of the presence of depression or anxiety, and extends this observation of independence to SMT and SMT + AM treatment effects. The competing “dependence of effects” argument asserts that the efficacy of AM is dependent on the presence of depression or anxiety because improvements in chronic tension-type headaches with AM are secondary to improvements in negative affect [18, 69]. The limited empirical data tend to support the independent effects argument [5, 13, 52], as do our headache findings. However, this argument has focused exclusively on headache activity as the outcome measure and not on headache-related disability [69]. Improvements in headache disability with both AM and with SMT were, in fact, dependent on the presence of a mood or anxiety disorder. Our findings thus appear consistent with the “independence of effects” when headache activity is the outcome and with the “dependence of effects” when headache disability is the outcome measure. Clinical observations of these divergent phenomena may help explain why this debate among clinicians remains unresolved.

To the best of our knowledge, our finding that the placebo response varied with the severity of the headache disorder and with the presence of a psychiatric disorder is the first examination of the determinants of the placebo response in chronic tension headache trials. The absence of a placebo response on headache activity for high severity CTTH disorders and the absence of a placebo response on headache disability when a mood or anxiety disorder was present over the eight month trial are particularly noteworthy. If the placebo response in clinical trials is, in fact, a function of disorder severity and the presence of psychiatric comorbidity this could have important theoretical implications for our understanding of the placebo response as well as practical implications for the design of clinical trials in chronic tension-type headache [40, 41, 80]. However, person characteristics that reliably predict placebo responding have been notoriously difficult to identify [19, 47, 72]. Thus, these exploratory findings require confirmation.

Floor effects did not explain the absence of treatment effects for AM alone and for SMT alone on headache activity for low severity CTTH disorders or the absence of treatment effects for AM alone or for SMT alone on headache disability when a mood and anxiety disorders were absent. All participants experienced at least 15 headache days per month allowing considerable room for improvement in headache activity, and participants were sufficiently impaired by their headaches to allow for improvements in headache disability. Moreover, improvements with combined SMT + AM were reasonably large on both outcome measures irrespective of severity of CTTH disorder or presence or absence of a mood or anxiety disorder, indicating no floor effect was evident for SMT + AM. Instead, the absence of treatment effects for AM alone and for SMT alone appeared to reflect the smaller improvements that were observed with these two treatments, combined with the larger PL response, both of which reduced the differences between active treatment and PL. Of course this larger “placebo” response may reflect not only the placebo effect, but also regression to the mean or the natural course of the disorder over time, sources of improvement that cannot be distinguished in our trial design [39].

Moderated Mediation

Concerns that perceived self-efficacy for managing headaches would prove refractory to change when a chronic tension-type headache disorder was severe, or that the addition of drug therapy to psychological therapy might undermine self-efficacy proved unfounded [20, 26, 67]. Thus, we found robust path coefficients linking both SMT and combined SMT + AM to HMSE change at Month 2 irrespective of headache severity. Path coefficients also tended to be at least as large for SMT + AM as for SMT, suggesting the addition of AM to SMT did not undermine confidence in the use of the headache management skills that are the focus of SMT. However, we lacked a treatment group that received SMT but neither AM nor PL, which would possibly provide a better comparison to address this latter question [20].

For SMT and for SMT + AM improvements in headache activity at Month 8 were explained by self-efficacy change at Month 2. Path coefficients for the alternate direct path (path c in Figure 4) were not statistically significant, and, thus, the observed treatment effects can be said to be fully mediated by HMSE change at Month 2. Our findings suggest the absence of HMSE change at Month 2 is a harbinger of a negative outcome at Month 8 with SMT, and, it appears, with SMT + AM. If the absence of HMSE change is a red flag signaling an impending negative outcome, this red flag can also alert the therapist to identify and address the reasons for patient's low confidence in their use of SMT skills, thereby possibly altering the patient's trajectory toward a negative outcome. A review of the individual's responses to items on the HMSE scale and the individual's experience using headache management skills is likely to reveal the circumstances where individual lacks confidence in using headache management skills.

The mediation of SMT and SMT + AM treatment effects presented a different picture when headache disability was the outcome. In the presence of a mood or anxiety disorder, improvements in headache disability at Month 8 were only partially mediated by HMSE change at Month 2. Although SMT and SMT + AM each effectively improved headache disability when a mood or anxiety disorder was present, changes in HMSE at Month 2 accounted for at most a third of this improvement in headache disability, suggesting therapeutic mechanisms other than HMSE change at Month 2 played an important role in improvements in headache disability when a mood or anxiety disorder was present. We propose that when a mood or anxiety disorder is present, improvements in headache disability are jointly mediated by reductions in affective distress and realistic increases in HMSE [33].

As might be expected, for AM drug therapy alone HMSE change at Month 2 appeared to play little of no role in improvements in either headache activity or headache disability at Month 8. This finding provides additional assurance that the appearance of self-efficacy mediation is not simply an artifact of improvements in headache activity or headache disability.

Study Limitations

We chose to limit our focus to the two potential moderator variables that have received the greatest attention in the clinical literature: severity of CTTH headache disorder and psychiatric comorbidity. This does not exclude the possible importance of other moderator variables [53, 60]. We defined psychiatric comorbidity as any mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis because the TCTH trial was too small to separately isolate specific mood or anxiety disorders as moderator variables. Exploratory analyses that examined the nature of the observed moderator effects were hypothesis generating rather than hypothesis testing, and thus should be viewed as providing hypotheses for confirmatory testing in future trials. We made no attempt to incorporate all plausible therapeutic mechanisms into our mediation analysis. To the contrary, we chose to restrict our focus to HMSE in order to determine if there was any support for HMSE mediation and, if there was support, the limits of HMSE as an explanatory variable. Other mediators might account equally well or better for the observed SMT or SMT + AM treatment effects we examined [23, 31, 44]. In fact, our results indicated that, when a mood or anxiety disorder is present, variables in addition to HMSE likely mediate improvement in headache disability. Unfortunately, neither the size nor the composition of the TCTH trial sample allowed us to determine if the moderator variables and mediation effects observed here were invariant across ethnic groups. The replication of these findings and their extension to other population are thus important lines of future research.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by a grant from The National Institutes of Health (NINDS # NS32374). No author has any financial or other conflict of interest, or a relationship that might reasonably be perceived as a conflict of interest. Appreciation is expressed to Gary Cordingley, Constance Cottrell, Douglas French, Gay Lipchik, Angela Nicolosi, Carol Nogrady, Francis O'Donnell, Peter Malinoski, Cornelia Pinnell, Michael Stensland, France Talbot, Robert Trombley for assistance with the TCTH trial.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Andrasik F, Lipchick G, McCrory D, Wittrock D. Outcome measurement in behavioral headache research: headache parameters and psychosocial outcomes. Headache. 2005;45:429–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashina A, Ashina M. Current and potential future drug therapies for tension-type headache. Curr Pain Head Rep. 2003;7:466–74. doi: 10.1007/s11916-003-0063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baskin S, Lipchik G, Smitherman T. Mood and anxiety disorders in chronic headache. Headache. 2006;46:S76–S87. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck AT. Cognitive approaches to stress. In: Lehrer PM, Woolfolk RL, editors. Principles and practice of stress management. New York: The Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 333–71. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bendtsen L, Mathew N. Prophylactic pharmacotherapy of tension-type headache. In: Olesen J, Goadsby P, Ramadan N, Tfelt-Hansen P, Welch K, editors. The headaches. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. pp. 735–41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernstein D, Borkovec T, Hazlett-Stevens H. New Directions in Progressive Relaxation Training: A Guidebook for Helping Professions. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanchard E, Andrasik F. Management of chronic headaches: a psychological approach. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanchard E, Hillhouse J, Appelbaum K, Jaccard J. What is an adequate length of baseline in research and clinical practice with chronic headache. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 1987;12:323–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00998723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanchard EB. Psychological treatment of benign headache disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:537–51. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanchard EB, Kim M, Hermann CU, Steffek BD. Preliminary results of the effects on headache relief of perception of success among tension headache patients receiving relaxation. Headache Q. 1993;4:249–53. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanchard EB, Applebaum KA, Radnitz CL, Michultka D, Morrill B, Kirsch C, Hillhouse J, Evans DD, Guarnieri P, Attanasio V, Andrasik F, Jaccard J, Dentinger MP. Placebo-controlled evaluation of abbreviated progressive muscle relaxation and of relaxation combined with cognitive therapy in the treatment of tension headache. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58:210–5. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borkum J. Chronic headaches: biology, psychology and behavioral treatment Hillsdale. New Jersey: Laurence Erlbaum; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cerbo R, Barbanti P, Fabbrini G. Amitriptyline in tension-type headache prophylaxis. Headache. 1998;38:453–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1998.3806453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Couch J. Medical management of recurrent tension-type headache. In: Tollison C, Kunkel R, editors. Headache diagnosis and treatment. Baltimore: Wiliams & Wilkins; 1993. pp. 151–62. [Google Scholar]

- 16.D'Zurilla TJ. Problem-solving training for effective stress management and prevention. J Cogn Psychother. 1990;4:327–54. [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM. Problem-solving therapy: a positive approach to clinical intervention. 3ed. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diamond S, Baltes BJ. Chronic tension headache treated with amitriptyline--a double blind study. Headache. 1971;11:110–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1971.hed1103110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ernst E. Towards a scientific understanding of placebo effects. In: Peters D, editor. Understanding the placebo effect in complementary medicine. London (UK): Harcourt; 2001. pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank E, Kupfer DJ. Does a placebo tablet affect psychotherapeutic outcome? Results from the Pittsburgh study of maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Psychother Res. 1992;2:102–11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.French DJ, Holroyd KA, Pinnell C, Malinoski PT, ODonnell FJ, Hill KR. Perceived self-efficacy and headache-related disability. Headache. 2000;40:647–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.040008647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gadbury G, Coffey C, Allison D. Modern statistical methods for handling missing data. Obes Rev. 2003;4:175–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2003.00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hatcher R, Gillaspy J. Development and validation of a revised short version of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychother Res. 2006;16:12–25. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:9–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heckman B, Holroyd K. Tension-type headache and psychiatric comorbidity. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2006;10:439–47. doi: 10.1007/s11916-006-0075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hollon SD, DeRubeis J. Placebo-psychotherapy combinations: inappropriate representations of psychotherapy in drug-psychotherapy comparative trials. Psychol Bull. 1981;90:467–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holroyd K. Behavioral and psychologic aspects of the pathophysiology and management of tension-type headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2002;6:401–7. doi: 10.1007/s11916-002-0083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holroyd K, Lipchik G, Penzien D. Psychological management of recurrent headache disorders: empirical basis for clinical practice. In: Dobson K, Craig K, editors. Best practice: developing and promoting empirically supported interventions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holroyd K, Martin P, Nash J. Psychological treatments of tension-type headaches. In: Olesen J, Goadsby P, Ramadan N, Tfelt-Hansen P, Welch K, editors. The headaches. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. pp. 711–20. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holroyd K, French D, Nash J, Tobin D, Echelberger-McCune R. Stress management for tension headaches: a treatment program for controlling headaches. Athens, OH: Ohio University Headache Project; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holroyd K, Drew J, Cottrell C, Romanek K, Heh V. Impaired functioning and quality of life in severe migraine: the role of catastrophizing and associated symptoms. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:1156–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holroyd K, Penzien D, Rains J, Lipchik G, Buse D. Behavioral management of headaches. In: Silberstein S, Lipton R, Dodick D, editors. Wolff's headache and other head pain. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 721–46. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holroyd K, Stensland M, Lipchik G, Hill K, O'Donnell F, Cordingley G. Psychosocial correlates and impact of chronic tension-type headaches. Headache. 2000;40:3–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holroyd KA. Assessment and psychological treatment of recurrent headache disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:656–77. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.3.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holroyd KA, Penzien D. EMG biofeedback and tension headache: therapeutic mechanisms. In: Holroyd K, Schlote B, Zenz F, editors. Perspectives in research on headache. Toronto: Hogrefe; 1983. pp. 147–62. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holroyd KA, Malinoski P, Davis MK, Lipchik GL. The three dimensions of headache impact: pain, disability and affective distress. Pain. 1999;83:571–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00165-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holroyd KA, O'Donnell FJ, Stensland M, Lipchik GL, Cordingley GE, Carlson B. Management of chronic tension-type headache with tricyclic antidepressant medication, stress-management therapy, and their combination: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:2208–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.17.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holroyd KA, Penzien DB, Hursey K, Tobin D, Rogers L, Holm J, Marcille PJ, Hall C, Chila AG. Change mechanisms in EMG biofeedback training: cognitive changes underlying improvements in tension headache. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52:1039–53. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.6.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hro'bjartsson A. What are the main methodological problems in the estimation of placebo effects. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55 doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hro'bjartsson A, Gotzsche P. Is the placebo powerless? An analysis of clinical trials comparing placebo with no treatment. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1594–601. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hro'bjartsson A, Gotzsche P. Is the placebo powerless? Update of a systematic review with 52 new randomized trials comparing placebo with no treatment. J Int Med. 2004;256:91–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobson GP, Ramadan NM, Aggarwal SK, Newman CW. The Henry Ford Hospital Headache Disability Inventory (HDI) Neurology. 1994;44:837–42. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.5.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobson GP, Ramadan NM, Norris L, Newman CW. Headache Disability Inventory (HDI): short-term test-retest reliability and spouse perceptions. Headache. 1995;35:534–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1995.hed3509534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM. Changes in beliefs, catastrophizing and coping are associated with improvement in multidisciplinary pain treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:655–62. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.4.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jensen R, Sandrini G. Symptomatology of chronic tension-type headache. In: Olesen J, Tfelt-Hansen P, Welch K, editors. The headaches. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 627–34. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jensen R, Symon D. Epidemiology of tension-type headaches. In: Olesen J, Goadsby P, Ramadan N, Tfelt-Hansen P, Welch K, editors. The headaches. Philadelphia: Lippincott WIlliams & Wilkins; 2006. pp. 621–4. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaptchuk T, Kelley J, Deykin A, Wayne P, Lasagna L, Epstein I, Kirsch I, Wechsler M. Do “placebo responders” exist? Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29:587–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kenny D, Calsyn R, Morse G, Klinkenberg W, Winter J, Trusty M. Evaluation of treatment programs for persons with severe mental illness: moderator and mediator effects. Eval Rev. 2004;28:294–324. doi: 10.1177/0193841X04264701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kraemer H, Wilson G, Fairburn C, Agras W. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–83. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kunkel RS. Diagnosis and treatment of muscle contraction (tension-type) headaches. Med Clin North Am. 1991;75:595–603. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30435-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lake A, Rains J, Penzien D, Lipchik G. Headache and psychiatric comorbidity: historical context, clinical implications, and research relevance. Headache. 2005;45:493–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lenaerts M, Newman L. Wolff's headache and other head pain. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. Tension-type headache; pp. 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Linde K, Witt C, Streng A, Weidenhammer W, Wagenpfeil S, Brinkhaus B, Willich S, Dieter M. The impact of patient expectations on outcomes in four randomized controlled trials of acupuncture in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2007;128:264–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lipchik G, Holroyd K, Nash J. Cognitive-behavioral management of recurrent headache disorders: a minimal-therapist contact approach. In: Turk DC, Gatchel RS, editors. Psychological approaches to pain management. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 356–89. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lipchik GL, Smitherman TA, Penzien DB, Holroyd KA. Basic principles and techniques of cognitive-behavioral therapies for comorbid psychiatric symptoms among headache patients. Headache. 2006;46:S119–S32. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.MacKinnon D, Lockwood C, Hoffman J. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.MacKinnon D, Fairchild A, Fritz M. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.MacKinnon D, Fairchild A, Fritz M. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mallinckrodt C, Watkin J, Molenberghs G, Carroll R. Choice of the primary analysis in longitudinal clinical trials. Pharm Statist. 2004;3:161–9. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martin NJ, Holroyd KA, Penzien DB. The headache-specific locus of control scale: adaptation to recurrent headaches. Headache. 1990;30:729–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1990.hed3011729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mathew N, Bendtsen L. Prophylactic pharmacotherapy of tension-type headache. In: Olesen J, Tfelt-Hansen P, Welch K, editors. The headaches. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 667–74. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mitsikostas D, Thomas A. Comorbidity of headache and depressive disorders. Cephalalgia. 1999;19:211–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1999.019004211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Molenberghs G, Thijs H, Jansen I, Beunckens C. Analyzing incomplete longitudinal clinical trial data. Biostatistics. 2004;5:445–64. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/5.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nicholson RA, Hursey RG, Nash JM. Moderators and mediators of behavioral treatment for headache. Headache. 2005;45:513–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Penzien D, Rains J, Andrasik F. Behavioral management of recurrent headache: three decades of experience and empiricism. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2002;27:163–81. doi: 10.1023/a:1016247811416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peveler R, George C, Kinmonth A, Cambell M, Thompson C. Effect of antidepressant drug counselling and information leaflets on adherence to drug treatment in primary care: randomised controlled trial. Brit Med J. 1999;319:612–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7210.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Powers M, Smits J, Whitley D, Bystritsky A, Telch M. The effect of attributional processes concerning medication taking on return of fear. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:478–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rains J, Penzien D, Lipchik G. Behavioral facilitation of medical treatment of headache: implications of non-compliance and strategies for improving adherence. Headache. 2006;46:S142–S3. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rifkin W, Ward L. Letter: Antidepressant medication for chronic tension type headache. JAMA. 2001;286:1969. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.16.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rokicki LA, Holroyd KA, France CR, Lipchik GL, France JL, Kvaal SA. Change mechanisms associated with combined relaxation/EMG biofeedback training for chronic tension headache. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 1997;22:21–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1026285608842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schoenen J, Wang W. Tension-type headache. In: Goadsby P, Silberstein S, editors. Headache. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1997. pp. 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shapiro A, Shapiro E. The powerful placebo effect. Baltimore, MA: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shrout P, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:422–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Silberstein S, Rosenberg J. Multispecialty consensus on diagnosis and treatment of headache. Neurology. 2000;54:1553–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.8.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Silberstein S, Lipton R, Goadsby P. Headache in clinical practice. London, England: Martin Dunitz; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Spitzer AL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-111-R. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Spitzer R, Williams J, Kroenke K, Linzer M, deGruy F, Hahn S, Brody D, Johnson J. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tein J, Sandler I, MacKinnon D, Wolchik S. How did it work? Who did it work for? Mediation in the context of a moderated prevention effect for children of divorce. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:617–24. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tobin DL, Holroyd KA, Baker A, Reynolds RVC, Holm JE. Development and clinical trial of a minimal contact, cognitive-behavioral treatment for tension headache. Cogn Ther Res. 1988;12:325–39. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Turner J, Deyo R, Loeser D, Von Korff M, Fordyce W. The importance of placebo effect in pain treatment and research. JAMA. 1994;271:1609–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wothke W, Arbuckle J. Full-information missing data analysis with Amos (SPSS White Paper) 1996. [Google Scholar]