Abstract

Ligand activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)γ and retinoid X receptor (RXR) induces antitumor effects in cancer. We evaluated the ability of combined treatment with nanomolar levels of the PPARγ ligand rosiglitazone (BRL) and the RXR ligand 9-cis-retinoic acid (9RA) to promote antiproliferative effects in breast cancer cells. BRL and 9RA in combination strongly inhibit of cell viability in MCF-7, MCF-7TR1, SKBR-3, and T-47D breast cancer cells, whereas MCF-10 normal breast epithelial cells are unaffected. In MCF-7 cells, combined treatment with BRL and 9RA up-regulated mRNA and protein levels of both the tumor suppressor p53 and its effector p21WAF1/Cip1. Functional experiments indicate that the nuclear factor-κB site in the p53 promoter is required for the transcriptional response to BRL plus 9RA. We observed that the intrinsic apoptotic pathway in MCF-7 cells displays an ordinated sequence of events, including disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential, release of cytochrome c, strong caspase 9 activation, and, finally, DNA fragmentation. An expression vector for p53 antisense abrogated the biological effect of both ligands, which implicates involvement of p53 in PPARγ/RXR-dependent activity in all of the human breast malignant cell lines tested. Taken together, our results suggest that multidrug regimens including a combination of PPARγ and RXR ligands may provide a therapeutic advantage in breast cancer treatment.

Breast cancer is the leading cause of death among women in the world. The principal effective endocrine therapy for advanced treatment on this type of cancer is anti-estrogens, but therapeutic choices are limited for estrogen receptor (ER)α-negative tumors, which are often aggressive. The development of cancer cells that are resistant to chemotherapeutic agents is a major clinical obstacle to the successful treatment of breast cancer, providing a strong stimulus for exploring new approaches in vitro. Using ligands of nuclear hormone receptors to inhibit tumor growth and progression is a novel strategy for cancer therapy. An example of this is the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia using all-trans retinoic acid, the specific ligand for retinoic acid receptors.1,2,3 A further paradigm for the use of retinoids in cancer therapy is for early lesions of head and neck cancer4 and squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix.5

The retinoic acid receptor, retinoid X receptor (RXR), and peroxisome proliferator receptor (PPAR)γ, ligand-activated transcription factors belonging to the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily, are able to modulate gene networks involved in controlling growth and cellular differentiation.6 Particularly, heterodimerization of PPARγ with RXR by their own ligands greatly enhances DNA binding to the direct-repeated consensus sequence AGGTCA, which leads to transcriptional activation.7 Previous data show that PPARγ, poorly expressed in normal breast epithelial cells,8 is present at higher levels in breast cancer cells,9 and its synthetic ligands, such as thiazolidinediones, induce growth arrest and differentiation in breast carcinoma cells in vitro and in animal models.10,11 Recently, studies in human cultured breast cancer cells show the thiazolidinedione rosiglitazone (BRL), promotes antiproliferative effects and activates different molecular pathways leading to distinct apoptotic processes.12,13,14

Apoptosis, genetically controlled and programmed death leading to cellular self-elimination, can be initiated by two major routes: the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. The intrinsic pathway is triggered in response to a variety of apoptotic stimuli that produce damage within the cell, including anticancer agents, oxidative damage, and UV irradiation, and is mediated through the mitochondria. The extrinsic pathway is activated by extracellular ligands able to induce oligomerization of death receptors, such as Fas, followed by the formation of the death-inducing signaling complex, after which the caspases cascade can be activated.

Previous data show that the combination of PPARγ ligand with either all-trans retinoic acid or 9-cis-retinoic acid (9RA) can induce apoptosis in some breast cancer cells.15 Furthermore, Elstner et al demonstrated that the combination of these drugs at micromolar concentrations reduced tumor mass without any toxic effects in mice.8 However, in humans PPARγ agonists at high doses exert many side effects including weight gain due to increased adiposity, edema, hemodilution, and plasma-volume expansion, which preclude their clinical application in patients with heart failure.16,17,18 The undesirable effects of RXR-specific ligands on hypertriglyceridemia and suppression of the thyroid hormone axis have been also reported.19 Thus, in the present study we have elucidated the molecular mechanism by which combined treatment with BRL and 9RA at nanomolar doses triggers apoptotic events in breast cancer cells, suggesting potential therapeutic uses for these compounds.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

BRL49653 (BRL) was from Alexis (San Diego, CA), the irreversible PPARγ-antagonist GW9662 (GW), and 9RA were purchased from Sigma (Milan, Italy).

Plasmids

The p53 promoter-luciferase plasmids, kindly provided by Dr. Stephen H. Safe (Texas A&M University, College Station, TX), were generated from the human p53 gene promoter as follows: p53-1 (containing the −1800 to + 12 region), p53-6 (containing the −106 to + 12 region), p53-13 (containing the −106 to −40 region), and p53-14 (containing the −106 to −49 region).20 As an internal transfection control, we cotransfected the plasmid pRL-CMV (Promega Corp., Milan, Italy) that expresses Renilla luciferase enzymatically distinguishable from firefly luciferase by the strong cytomegalovirus enhancer promoter. The pGL3 vector containing three copies of a peroxisome proliferator response element sequence upstream of the minimal thymidine kinase promoter ligated to a luciferase reporter gene (3XPPRE-TK-pGL3) was a gift from Dr. R. Evans (The Salk Institute, San Diego, CA). The p53 antisense plasmid (AS/p53) was kindly provided from Dr. Moshe Oren (Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel).

Cell Cultures

Wild-type human breast cancer MCF-7 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium-F12 plus glutamax containing 5% newborn calf serum (Invitrogen, Milan, Italy) and 1 mg/ml penicillin-streptomycin. MCF-7 tamoxifen resistant (MCF-7TR1) breast cancer cells were generated in Dr. Fuqua’s laboratory similar to that described by Herman21 maintaining cells in modified Eagle’s medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 6 ng/ml insulin, penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and adding 4-hydroxytamoxifen in tenfold increasing concentrations every weeks (from 10−9 to 10−6 final). Cells were thereafter routinely maintained with 1 μmol/L 4-hydroxytamoxifen. SKBR-3 breast cancer cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium without red phenol, plus glutamax containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1 mg/ml penicillin-streptomycin. T-47D breast cancer cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium with glutamax containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 2.5g/L glucose, 0.2 U/ml insulin, and 1 mg/ml penicillin-streptomycin. MCF-10 normal breast epithelial cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium-F12 plus glutamax containing 5% horse serum (Sigma), 1 mg/ml penicillin-streptomycin, 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone, and 10 μg/ml insulin.

Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability was determined with the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium (MTT) assay.22 Cells (2 × 105 cells/ml) were grown in 6 well plates and exposed to 100 nmol/L BRL, 50 nmol/L 9RA alone or in combination in serum free medium (SFM) and in 5% charcoal treated (CT)-fetal bovine serum; 100 μl of MTT (5 mg/ml) were added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 4 hours at 37°C. Then, 1 ml 0.04 N HCl in isopropanol was added to solubilize the cells. The absorbance was measured with the Ultrospec 2100 Pro-spectrophotometer (Amersham-Biosciences, Milan, Italy) at a test wavelength of 570 nm.

Immunoblotting

Cells were grown in 10-cm dishes to 70% to 80% confluence and exposed to treatments in SFM as indicated. Cells were then harvested in cold PBS and resuspended in lysis buffer containing 20 mmol/L HEPES (pH 8), 0.1 mmol/L EGTA, 5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.5 M/L NaCl, 20% glycerol, 1% Triton, and inhibitors (0.1 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate, 1% phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, and 20 mg/ml aprotinin). Protein concentration was determined by Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). A 40 μg portion of protein lysates was used for Western blotting, resolved on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with an antibody directed against the p53, p21WAF1/Cip1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA). As internal control, all membranes were subsequently stripped (0.2 M/L glycine, pH 2.6, for 30 minutes at room temperature) of the first antibody and reprobed with anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The antigen–antibody complex was detected by incubation of the membranes for 1 hour at room temperature with peroxidase-coupled goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG and revealed using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Pharmacia, Buckinghamshire UK). Blots were then exposed to film (Kodak film, Sigma). The intensity of bands representing relevant proteins was measured by Scion Image laser densitometry scanning program.

Reverse Transcription-PCR Assay

MCF-7 cells were grown in 10 cm dishes to 70% to 80% confluence and exposed to treatments in SFM as indicated. Total cellular RNA was extracted using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen) as suggested by the manufacturer. The purity and integrity were checked spectroscopically and by gel electrophoresis before carrying out the analytical procedures. Two micrograms of total RNA were reverse transcribed in a final volume of 20 μl using a RETROscript kit as suggested by the manufacturer (Promega). The cDNAs obtained were amplified by PCR using the following primers: 5′-GTGGAAGGAAATTTGCGTGT-3′ (p53 forward) and 5′-CCAGTGTGATGATGGTGAGG-3′ (p53 reverse), 5′-GCTTCATGCCAGCTACTTCC-3′ (p21 forward) and 5′-CTGTGCTCACTTCAGGGTCA-3′ (p21 reverse), 5′-CTCAACATCTCCCCCTTCTC-3′ (36B4 forward) and 5′-CAAATCCCATATCCTCGTCC-3′ (36B4 reverse) to yield, respectively, products of 190 bp with 18 cycles, 270 bp with 18 cycles, and 408 bp with 12 cycles. To check for the presence of DNA contamination, reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed on 2 μg of total RNA without Monoley murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (the negative control). The results obtained as optical density arbitrary values were transformed to percentage of the control taking the samples from untreated cells as 100%.

Transfection Assay

MCF-7 cells were transferred into 24-well plates with 500 μl of regular growth medium/well the day before transfection. The medium was replaced with SFM on the day of transfection, which was performed using Fugene 6 reagent as recommended by the manufacturer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) with a mixture containing 0.5 μg of promoter-luc or reporter-luc plasmid and 5 ng of pRL-CMV. After transfection for 24 hours, treatments were added in SFM as indicated, and cells were incubated for an additional 24 hours. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured using the Dual Luciferase Kit (Promega). The firefly luciferase values of each sample were normalized by Renilla luciferase activity, and data were reported as relative light units.

MCF-7 cells plated into 10 cm dishes were transfected with 5 μg of AS/p53 using Fugene 6 reagent as recommended by the manufacturer (Roche Diagnostics). The activity of AS/p53 was verified using Western blot to detect changes in p53 protein levels. Empty vector was used to ensure that DNA concentrations were constant in each transfection.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

Nuclear extracts from MCF-7 cells were prepared as previously described.23 Briefly, MCF-7 cells plated into 10-cm dishes were grown to 70% to 80% confluence, shifted to SFM for 24 hours, and then treated with 100 nmol/L BRL, 50 nmol/L 9RA alone and in combination for 6 hours. Thereafter, cells were scraped into 1.5 ml of cold PBS, pelleted for 10 seconds, and resuspended in 400 μl cold buffer A (10 mmol/L HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9] at 4°C, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mmol/L KCl, 0.5 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 0.2 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1 mmol/L leupeptin) by flicking the tube. Cells were allowed to swell on ice for 10 minutes and were then vortexed for 10 seconds. Samples were then centrifuged for 10 seconds and the supernatant fraction was discarded. The pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of cold Buffer B (20 mmol/L HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 25% glycerol, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 420 mmol/L NaCl, 0.2 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 0.2 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1 mmol/L leupeptin) and incubated in ice for 20 minutes for high-salt extraction. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation for 2 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant fraction (containing DNA-binding proteins) was stored at −70°C. The probe was generated by annealing single-stranded oligonucleotides and labeled with [32P]ATP (Amersham Pharmacia) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega) and then purified using Sephadex G50 spin columns (Amersham Pharmacia). The DNA sequence of the nuclear factor (NF)κB located within p53 promoter as probe is 5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′ (Sigma Genosys, Cambridge, UK). The protein-binding reactions were performed in 20 μl of buffer [20 mmol/L HEPES (pH 8), 1 mmol/L EDTA, 50 mmol/L KCl, 10 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 50 μg/ml polydeoxyinosinic deoxycytidylic acid] with 50,000 cpm of labeled probe, 20 μg of MCF7 nuclear protein, and 5 μg of polydeoxyinosinic deoxycytidylic acid. The mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes in the presence or absence of unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides. For the experiments involving anti-PPARγ and anti-RXRα antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), the reaction mixture was incubated with these antibodies at 4°C for 30 minutes before addition of labeled probe. The entire reaction mixture was electrophoresed through a 6% polyacrylamide gel in 0.25× Tris borate-EDTA for 3 hours at 150 V. Gel was dried and subjected to autoradiography at −70°C.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

MCF-7 cells were grown in 10 cm dishes to 50% to 60% confluence, shifted to SFM for 24 hours, and then treated for 1 hour as indicated. Thereafter, cells were washed twice with PBS and cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde at 37°C for 10 minutes. Next, cells were washed twice with PBS at 4°C, collected and resuspended in 200 μl of lysis buffer (1% SDS, 10 mmol/L EDTA, 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.1), and left on ice for 10 minutes. Then, cells were sonicated four times for 10 seconds at 30% of maximal power (Vibra Cell 500 W; Sonics and Materials, Inc., Newtown, CT) and collected by centrifugation at 4°C for 10 minutes at 14,000 rpm. The supernatants were diluted in 1.3 ml of immunoprecipitation buffer (0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton X-100, 1.2 mmol/L EDTA, 16.7 mmol/L Tris-HCl [pH 8.1], 16.7 mmol/L NaCl) followed by immunoclearing with 60 μl of sonicated salmon sperm DNA/protein A agarose (DBA Srl, Milan, Italy) for 1 hour at 4°C. The precleared chromatin was immunoprecipitated with anti-PPARγ, anti-RXRα, or anti-RNA Pol II antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). At this point, 60 μl salmon sperm DNA/protein A agarose was added, and precipitation was further continued for 2 hours at 4°C. After pelleting, precipitates were washed sequentially for 5 minutes with the following buffers: Wash A [0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), 150 mmol/L NaCl]; Wash B [0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), 500 mmol/L NaCl]; and Wash C [0.25 M/L LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.1)], and then twice with 10 mmol/L Tris, 1 mmol/L EDTA. The immunocomplexes were eluted with elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M/L NaHCO3). The eluates were reverse cross-linked by heating at 65°C and digested with proteinase K (0.5 mg/ml) at 45°C for 1 hour. DNA was obtained by phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction. Two microliters of 10 mg/ml yeast tRNA (Sigma) were added to each sample, and DNA was precipitated with 95% ethanol for 24 hours at −20°C and then washed with 70% ethanol and resuspended in 20 μl of 10 mmol/L Tris, 1 mmol/L EDTA buffer. A 5 μl volume of each sample was used for PCR with primers flanking a sequence present in the p53 promoter: 5′-CTGAGAGCAAACGCAAAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGCCCGAACGCAAAGTGTC- 3′ (reverse) containing the κB site from −254 to −42 region. The PCR conditions for the p53 promoter fragments were 45 seconds at 94°C, 40 seconds at 57°C, and 90 seconds at 72°C. The amplification products obtained in 30 cycles were analyzed in a 2% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The negative control was provided by PCR amplification without a DNA sample. The specificity of reactions was ensured using normal mouse and rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

JC-1 Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Detection Assay

The loss of mitochondrial membrane potential was monitored with the dye 5,5′,6,6′tetra-chloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolyl-carbocyanine iodide (JC-1) (Biotium, Hayward). In healthy cells, the dye stains the mitochondria bright red. The negative charge established by the intact mitochondrial membrane potential allows the lipophilic dye, bearing a delocalized positive charge, to enter the mitochondrial matrix where it aggregates and gives red fluorescence. In apoptotic cells, the mitochondrial membrane potential collapses, and the JC-1 cannot accumulate within the mitochondria, it remains in the cytoplasm in a green fluorescent monomeric form.24 MCF-7 cells were grown in 10 cm dishes and treated with 100 nmol/L BRL and/or 50 nmol/L 9RA for 48 hours, then cells were washed in ice-cold PBS, and incubated with 10 mmol/L JC-1 at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 20 minutes in darkness. Subsequently, cells were washed twice with PBS and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. The red form has absorption/emission maxima of 585/590 nm. The green monomeric form has absorption/emission maxima of 510/527 nm. Both healthy and apoptotic cells can be visualized by fluorescence microscopy using a wide band-pass filter suitable for detection of fluorescein and rhodamine emission spectra.

Cytochrome C Detection

Cytochrome C was detected by western blotting in mitochondrial and cytoplasmatic fractions. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 2500 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. The pellets were suspended in 36 μl RIPA buffer plus 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 50 mmol/L PMSF and 50 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate and then 4 μl of 0.1% digitonine were added. Cells were incubated for 15 minutes at 4°C and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C. The resulting mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in 3% Triton X-100, 20 mmol/L Na2SO4, 10 mmol/L PIPES, and 1 mmol/L EDTA (pH 7.2) and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. Proteins of the mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were determined by Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Equal amounts of protein (40 μg) were resolved by 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with an antibody directed against the cytochrome C (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Then, membranes were subjected to the same procedures described for immunoblotting.

Flow Cytometry Assay

MCF-7 cells (1 × 106 cells/well) were grown in 6 well plates and shifted to SFM for 24 hours before adding treatments for 48 hours. Thereafter, cells were trypsinized, centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 3 minutes, washed with PBS. Addition of 0.5 μl of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibodies, anti-caspase 9 and anti-caspase 8 (Calbiochem, Milan, Italy), in all samples was performed and then incubated for 45 minutes in at 37°C. Cells were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 minutes, the pellets were washed with 300 μl of wash buffer and centrifuged. The last passage was repeated twice, the supernatant removed, and cells dissolved in 300 μl of wash buffer. Finally, cells were analyzed with the FACScan (Becton Dickinson and Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ).

DNA Fragmentation

DNA fragmentation was determined by gel electrophoresis. MCF-7 cells were grown in 10 cm dishes to 70% confluence and exposed to treatments. After 56 hours cells were collected and washed with PBS and pelleted at 1800 rpm for 5 minutes. The samples were resuspended in 0.5 ml of extraction buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8; 10 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5% SDS) for 20 minutes in rotation at 4°C. DNA was extracted three times with phenol-chloroform and one time with chloroform. The aqueous phase was used to precipitate nucleic acids with 0.1 volumes of 3M sodium acetate and 2.5 volumes cold ethanol overnight at −20°C. The DNA pellet was resuspended in 15 μl of H2O treated with RNase A for 30 minutes at 37°C. The absorbance of the DNA solution at 260 and 280 nm was determined by spectrophotometry. The extracted DNA (40 μg/lane) was subjected to electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide and then photographed.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance followed by Newman-Keuls testing to determine differences in means. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

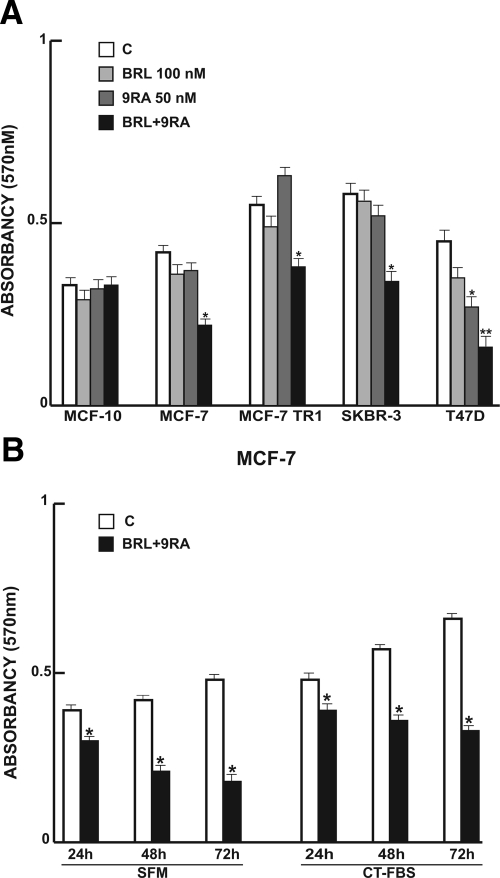

Nanomolar Concentrations of the Combined BRL and 9RA Treatment Affect Cell Viability in Breast Cancer Cells

Previous studies demonstrated that micromolar doses of PPARγ ligand BRL and RXR ligand 9RA exert antiproliferative effects on breast cancer cells.13,15,25,26 First, we tested the effects of increasing concentrations of both ligands on breast cancer cell proliferation at different times in the presence or absence of serum media (see Supplemental Figure 1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Thus, to investigate whether low doses of combined agents are able to inhibit cell growth, we assessed the capability of 100 nmol/L BRL and 50 nmol/L 9RA to affect normal and malignant breast cell lines. We observed that treatment with BRL alone does not elicit any significant effect on cell viability in all breast cell lines tested, while 9RA alone reduces cell vitality only in T47-D cells (Figure 1A). In the presence of both ligands, cell viability is strongly reduced in all breast cancer cells: MCF-7, its variant MCF-7TR1, SKBR-3, and T-47D; while MCF-10 normal breast epithelial cells are completely unaffected (Figure 1A). In MCF-7 cells the effectiveness of both ligands in reducing tumor cell viability still persists in SFM, as well as in 5% CT-FBS (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Cell vitality in breast cell lines. A: Breast cells were treated for 48 hours in SFM in the presence of 100 nmol/L BRL or/and 50 nmol/L. 9RA Cell vitality was measured by MTT assay. Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments done in triplicate. B: MCF-7 cells were treated for 24, 48, and 72 hours with 100 nmol/L BRL and 50 nmol/L 9RA in the presence of SFM and 5% CT-FBS. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 treated versus untreated cells.

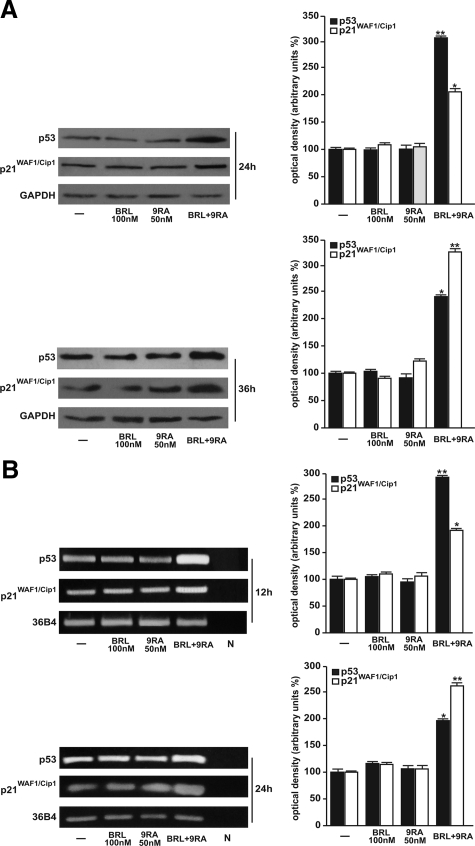

BRL and 9RA Up-Regulate p53 and p21WAF1/Cip1 Expression in MCF-7 Cells

Our recent work demonstrated that micromolar doses of BRL activate PPARγ, which in turn triggers apoptotic events through an up-regulation of p53 expression.12 On the basis of these results, we evaluated the ability of nanomolar doses of BRL and 9RA alone or in combination to modulate p53 expression along with its natural target gene p21WAF1/Cip1 in MCF-7 cells. A significant increase in p53 and p21WAF1/Cip1 content was observed by Western blot only on combined treatment after 24 and 36 hours (Figure 2A). Furthermore, we showed an up-regulation of p53 and p21WAF1/Cip1 mRNA levels induced by BRL plus 9RA after 12 and 24 hours (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Upregulation of p53 and p21WAF1/Cip1 expression induced by BRL plus 9RA in MCF-7 cells. A: Immunoblots of p53 and p21WAF1/Cip1 from extracts of MCF-7 cell treated with 100 nmol/L BRL and 50 nmol/L 9RA alone or in combination for 24 and 36 hours. GAPDH was used as loading control. The side panels show the quantitative representation of data (mean ± SD) of three independent experiments after densitometry. B: p53 and p21WAF1/Cip1 mRNA expression in MCF-7 cells treated as in A for 12 and 24 hours. The side panels show the quantitative representation of data (mean ± SD) of three independent experiments after densitometry and correction for 36B4 expression. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 combined-treated versus untreated cells. N: RNA sample without the addition of reverse transcriptase (negative control).

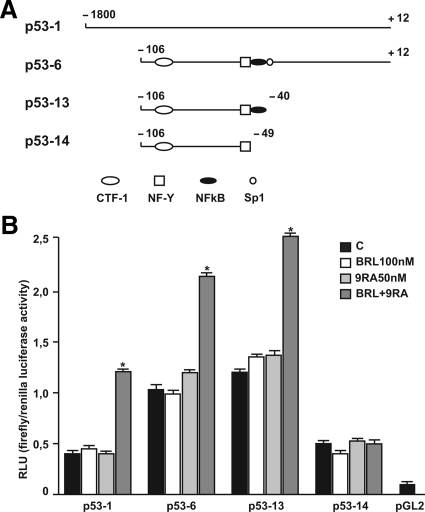

Low Doses of PPARγ and RXR Ligands Transactivate p53 Gene Promoter

To investigate whether low doses of BRL and 9RA are able to transactivate the p53 promoter gene, we transiently transfected MCF-7 cells with a luciferase reporter construct (named p53-1) containing the upstream region of the p53 gene spanning from −1800 to + 12 (Figure 3A). Treatment for 24 hours with 100 nmol/L BRL or 50 nmol/L 9RA did not induce luciferase expression, whereas the presence of both ligands increased in the transactivation of p53-1 promoter (Figure 3B). To identify the region within the p53 promoter responsible for its transactivation, we used constructs with deletions to different binding sites such as CTF-1, nuclear factor-Y, NFκB, and GC sites (Figure 3A). In transfection experiments performed using the mutants p53-6 and p53-13 encoding the regions from −106 to + 12 and from −106 to −40, respectively, the responsiveness to BRL plus 9RA was still observed (Figure 3B). In contrast, a construct with a deletion in the NFκB domain (p53-14) encoding the sequence from −106 to −49, the transactivation of p53 by both ligands was absent (Figure 3B), suggesting that NFκB site is required for p53 transcriptional activity.

Figure 3.

BRL and 9RA transactivate p53 promoter gene in MCF-7 cells. A: Schematic map of the p53 promoter fragments used in this study. B: MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected with p53 gene promoter-luc reporter constructs (p53-1, p53-6, p53-13, p53-14) and treated for 24 hours with 100 nmol/L BRL and 50 nmol/L 9RA alone or in combination. The luciferase activities were normalized to the Renilla luciferase as internal transfection control and data were reported as RLU values. Columns are mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *P < 0.05 combined-treated versus untreated cells. pGL2: basal activity measured in cells transfected with pGL2 basal vector; RLU, relative light units; CTF-1, CCAAT-binding transcription factor-1; NF-Y, nuclear factor-Y; NFκB, nuclear factor κB.

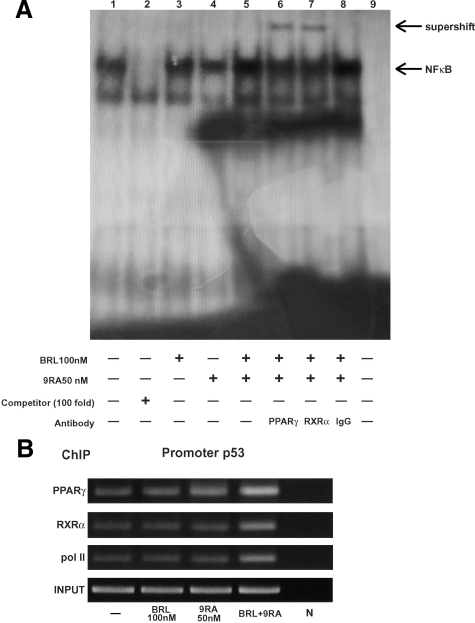

Heterodimer PPARγ/RXRα binds to NFκB Sequence in Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay and in Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

To gain further insight into the involvement of NFκB site in the p53 transcriptional response to BRL plus 9RA, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assay experiments using synthetic oligodeoxyribonucleotides corresponding to the NFκB sequence within p53 promoter. We observed the formation of a specific DNA binding complex in nuclear extracts from MCF-7 cells (Figure 4A, lane 1), where specificity is supported by the abrogation of the complex by 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled probe (Figure 4A, lane 2). BRL treatment induced a slight increase in the specific band (Figure 4A, lane 3), while no changes were observed on 9RA exposure (Figure 4A, lane 4). The combined treatment increased the DNA binding complex (Figure 4A, lane 5), which was immunodepleted and supershifted using anti-PPARγ (Figure 4A, lane 6) or anti-RXRα (Figure 4A, lane 7) antibodies. These data indicate that heterodimer PPARγ/RXRα binds to NFκB site located in the promoter of p53 in vitro.

Figure 4.

PPARγ/RXRα binds to NFκB sequence in electrophoretic mobility shift assay and in chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. A: Nuclear extracts from MCF-7 cells (lane 1) were incubated with a double-stranded NFκB consensus sequence probe labeled with [32P] and subjected to electrophoresis in a 6% polyacrylamide gel. Competition experiments were done, adding as competitor a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled probe (lane 2). Nuclear extracts from MCF-7 were treated with 100 nmol/L BRL (lane 3), 50 nmol/L 9RA (lane 4), and in combination (lane5). Anti-PPARγ (lane 6), anti-RXRα (lane 7), and IgG (lane 8) antibodies were incubated. Lane 9 contains probe alone. B: MCF-7 cells were treated for 1 hour with 100 nmol/L BRL and/or 50 nmol/L 9RA as indicated, and then cross-linked with formaldehyde and lysed. The soluble chromatin was immunoprecipitated with anti-PPARγ, anti-RXRα, and anti-RNA Pol II antibodies. The immunocomplexes were reverse cross-linked, and DNA was recovered by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The p53 promoter sequence containing NFκB was detected by PCR with specific primers. To control input DNA, p53 promoter was amplified from 30 μl of initial preparations of soluble chromatin (before immunoprecipitation). N: negative control provided by PCR amplification without DNA sample.

The interaction of both nuclear receptors with the p53 promoter was further elucidated by chromatin immunoprecipitation assays. Using anti-PPARγ and anti-RXRα antibodies, protein-chromatin complexes were immunoprecipitated from MCF-7 cells treated with 100 nmol/L BRL and 50 nmol/L 9RA. PCR was used to determine the recruitment of PPARγ and RXRα to the p53 region containing the NFκB site. The results indicated that either PPARγ or RXRα was constitutively bound to the p53 promoter in untreated cells and this recruitment was increased on BRL plus 9RA exposure (Figure 4B). Similarly, an augmented RNA-Pol II recruitment was obtained by immunoprecipitating cells with an anti-RNA-Pol II antibody, indicating that a positive regulation of p53 transcription activity was induced by combined treatment (Figure 4B).

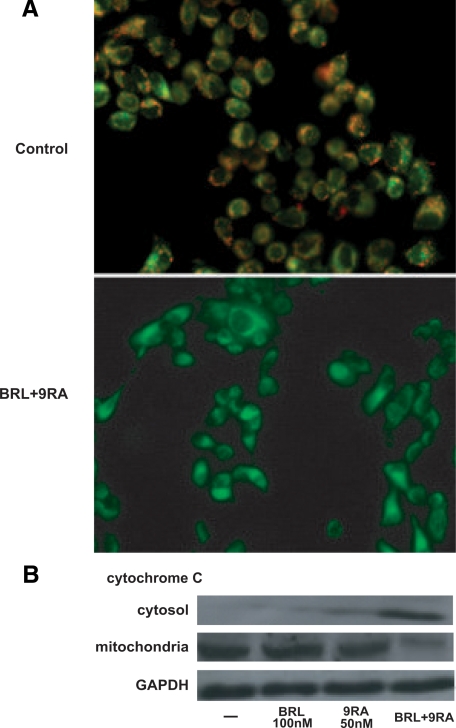

BRL and 9RA Induce Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Disruption and Release of Cytochrome C from Mitochondria into the Cytosol in MCF-7 Cells

The role of p53 signaling in the intrinsic apoptotic cascades involves a mitochondria-dependent process, which results in cytochrome C release and activation of caspase-9. Because disruption of mitochondrial integrity is one of the early events leading to apoptosis, we assessed whether BRL plus 9RA could affect the function of mitochondria by analyzing membrane potential with a mitochondria fluorescent dye JC-1.24,27 In non-apoptotic cells (control) the intact mitochondrial membrane potential allows the accumulation of lipophilic dye in aggregated form in mitochondria, which display red fluorescence (Figure 5A). MCF-7 cells treated with 100 nmol/L BRL or 50 nmol/L 9RA exhibit red fluorescence indicating intact mitochondrial membrane potential (data not shown). Cells treated with both ligands exhibit green fluorescence, indicating disrupted mitochondrial membrane potential, where JC-1 cannot accumulate within the mitochondria, but instead remains as a monomer in the cytoplasm (Figure 5A). Concomitantly, cytochrome C release from mitochondria into the cytosol, a critical step in the apoptotic cascade, was demonstrated after combined treatment (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Mitochondrial membrane potential disruption and release of cytochrome C induced by BRL and 9RA in MCF-7 cells. A: MCF-7 cells were treated with 100 nmol/L BRL plus 50 nmol/L 9RA for 48 hours and then used fluorescent microscopy to analyze the results of JC-1 (5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′- tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide) kit. In control nonapoptotic cells, the dye stains the mitochondria red. In treated apoptotic cells, JC-1 remains in the cytoplasm in a green fluorescent form. B: MCF-7 cells were treated for 48 hours with 100 nmol/L BRL and/or 50 nmol/L 9RA. GAPDH was used as loading control.

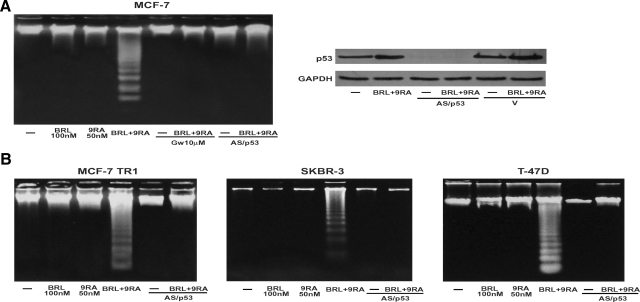

Caspase-9 Cleavage and DNA Fragmentation Induced by BRL Plus 9RA in MCF-7 Cells

BRL and 9RA at nanomolar concentration did not induce any effects on caspase-9 separately, but activation was observed in the presence of both compounds (Table 1). No effects were elicited by either the combined or the separate treatment on caspase-8 activation, a marker of extrinsic apoptotic pathway (Table 1). Since internucleosomal DNA degradation is considered a diagnostic hallmark of cells undergoing apoptosis, we studied DNA fragmentation under BRL plus 9RA treatment in MCF-7 cells, observing that the induced apoptosis was prevented by either the PPARγ-specific antagonist GW or by AS/p53, which is able to abolish p53 expression (Figure 6A).

Table 1.

Activation of caspases in MCF-7 cells

| % of Activation | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Caspase 9 | ||

| Control | 14.16 | ± 2.565 |

| BRL 100 nmol/L | 17.23 | ± 1.678 |

| 9RA 50 nmol/L | 18.14 | ± 0.986 |

| BRL + 9RA | 33.88* | ± 5.216 |

| Caspase 8 | ||

| Control | 9.20 | ± 1.430 |

| BRL 100 nmol/L | 8.12 | ± 1.583 |

| 9RA 50 nmol/L | 7.90 | ± 0.886 |

| BRL + 9RA | 10.56 | ± 2.160 |

Cells were stimulated for 48 hours in presence of 100 nmol/L BRL and 50 nmol/L 9RA, alone or in combination. The activation of caspase 9 and caspase 8 was analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are presented as mean ± SD of triplicate experiments.

P < 0.05 combined-treated versus untreated cells.

Figure 6.

Combined treatment of BRL and 9RA trigger apoptosis in breast cancer cells. A: DNA laddering was performed in MCF-7 cells transfected and treated as indicated for 56 hours. One of three similar experiments is presented. The side panel shows the immunoblot of p53 from MCF-7 cells transfected with an expression plasmid encoding for p53 antisense (AS/p53) or empty vector (v) and treated with 100 nmol/L BRL plus 50 nmol/L 9RA for 56 hours. GAPDH was used as loading control. B: DNA laddering was performed in MCF-7 TR1, SKBR-3, and T47-D cells transfected with AS/p53 or empty vector (v) and treated as indicated. One of three similar experiments is presented.

To test the ability of low doses of both BRL and 9RA to induce transcriptional activity of PPARγ, we transiently transfected a peroxisome proliferator response element reporter gene in MCF-7 cells and observed an enhanced luciferase activity, which was reversed by GW treatment (see Supplemental Figure 2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). These data are in agreement with previous observations demonstrating that PPARγ/RXR heterodimerization enhances DNA binding and transcriptional activation.28,29

Finally, we examined in three additional human breast malignant cell lines: MCF-7 TR1, SKBR-3, and T-47D the capability of low doses of a PPARγ and an RXR ligand to trigger apoptosis. DNA fragmentation assay showed that only in the presence of combined treatment did cells undergo apoptosis in a p53-mediated manner (Figure 6B), implicating a general mechanism in breast carcinoma.

Discussion

The key finding of this study is that the combined treatment with low doses of a PPARγ and an RXR ligand can selectively affect breast cancer cells through cell growth inhibition and apoptosis.

The ability of PPARγ ligands to induce differentiation and apoptosis in a variety of cancer cell types, such as human lung,30 colon,31 and breast,10 has been exploited in experimental cancer therapies.32 PPARγ agonist administration in liposarcoma patients resulted in histological and biochemical differentiation markers in vivo.33 However, a pilot study of short-term therapy with the PPARγ ligand rosiglitazone in early-stage breast cancer patients did not elicit significant effects on tumor cell proliferation, although the changes observed in PPARγ expression may be relevant to breast cancer progression.34 On the other hand, the natural ligand for RXR, 9RA,35 has been effective in vitro against many types of cancer, including breast tumor.36,37,38,39,40 Recently, RXR-selective ligands were discovered to inhibit proliferation of all-trans retinoic acid–resistant breast cancer cells in vitro and caused regression of the disease in animal models.41 The additive antitumoral effects of PPARγ and RXR agonists, both at elevated doses, have been shown in human breast cancer cells (15,42 and references therein). However, high doses of both ligands have remarkable side effects in humans, such as weight gain and plasma volume expansion for PPARγ ligands,16,17,18 and hypertriglyceridemia and suppression of the thyroid hormone axis for RXR ligands.19

In the present study, we demonstrated that nanomolar concentrations of BRL and 9RA in combination exert significant antiproliferative effects on breast cancer cells, whereas they do not induce noticeable influences on normal breast epithelial MCF10 cells. However, the induced overexpression of PPARγ in MCF10 cells makes these cells responsive to the low combined concentration of BRL and 9RA (data not shown). Although PPARγ is known to mediate differentiation in most tissues, its role in either tumor progression or suppression is not yet clearly elucidated. It has been demonstrated in animals studies that an overexpression of PPARγ increases the risk of breast cancer already in mice susceptible to the disease.43 However, it remains still questionable if the enhanced PPARγ expression does correspond to an enhanced content of functional protein, which according to previous suggestion should be carefully controlled in a dose-response study.44 For instance, the expression of PPARγ is under complex regulatory mechanisms, sustained by cell-specific distinct promoters mediating the changes in expression of PPARγ.45

Here we demonstrated for the first time the molecular mechanism underlying antitumoral effects induced by combined low doses of both ligands in MCF-7 cells, where an up-regulation of tumor suppressor gene p53 was concomitantly observed. Functional assays with deletion constructs of the p53 promoter showed that the NFκB site is required for the transcriptional response to BRL plus 9RA treatment. NFκB was shown to physically interact with PPARγ,46 which in some circumstances binds to DNA cooperatively with NFκB.47,48,49 It has been previously reported that micromolar doses of both PPARγ and RXR agonists synergize to generate an increased level of NFκB-DNA binding able to trigger apoptosis in Pre-B cells.50 Our electrophoretic mobility shift assay and chromatin immunoprecipitation assay demonstrated that PPARγ/RXRα complex is present on p53 promoter in the absence of exogenous ligand. Only BRL and 9RA in combination increased the binding and the recruitment of either PPARγ or RXRα on the NFκB site located in the p53 promoter sequence. BRL plus 9RA at the doses tested also increased the recruitment of RNA-Pol II to p53 promoter gene illustrating a positive transcriptional regulation able to produce a consecutive series of events in the apoptotic pathway.

Changes in mitochondrial membrane permeability, an important step in the induction of cellular apoptosis, is concomitant with collapse of the electrochemical gradient across the mitochondrial membrane, through the formation of pores in the mitochondria leading to the release of cytochrome C into the cytoplasm, and subsequently with cleavage of procaspase-9. This cascade of events, featuring the mitochondria-mediated death pathway, was detected in BRL plus 9RA-treated MCF-7 cells. The activation of caspase 9, in the presence of no changes in the biological activity of caspase 8, support that in our experimental model only the intrinsic apoptotic pathway is the effector of the combined treatment with the two ligands.

The crucial role of p53 gene in mediating apoptosis is raised by the evidence that the effects on the apoptotic cascade were abrogated in the presence of AS/p53 in all breast cancer cell lines tested, including tamoxifen resistant breast cancer cells. In tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells, other authors have observed that epidermal growth factor receptor, insulin-like growth factor-1R, and c-Src signaling are constitutively activated and responsible for a more aggressive phenotype consistent with an increased motility and invasiveness.51,52,53 Although more relevance of our findings should derive from in vivo studies, these results give emphasis to the potential use of the combined therapy with low doses of both BRL and 9RA as novel therapeutic tool particularly for breast cancer patients who develop resistance to anti-estrogen therapy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Prof. Sebastiano Andò, Faculty of Pharmacy Nutritional and Health Sciences, University of Calabria, 87036 Arcavacata - Rende (Cosenza), Italy. E-mail: sebastiano.ando@unical.it.

Supported by AIRC, MURST, and Ex 60%.

Portions of this work were presented as an Abstract at Società Italiana di Patologia XXIX National Congress in Rende, Italy, on September 10–13, 2008.

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- Ryningen A, Stapnes C, Paulsen K, Lassalle P, Gjertsen BT, Bruserud O. In vivo biological effects of ATRA in the treatment of AML. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:1623–1633. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.11.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravandi F, Estey E, Jones D, Faderl S, O'Brien S, Fiorentino J, Pierce S, Blamble D, Estrov Z, Wierda W, Ferrajoli A, Verstovsek S, Garcia-Manero G, Cortes J, Kantarjian H. Effective treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-trans-retinoic acid, arsenic trioxide, and gemtuzumab ozogamicin. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:504–510. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montesinos P, Bergua JM, Vellenga E, Rayón C, Parody R, de la Serna J, León A, Esteve J, Milone G, Debén G, Rivas C, González M, Tormo M, Díaz-Mediavilla J, González JD, Negri S, Amutio E, Brunet S, Lowenberg B, Sanz MA. Differentiation syndrome in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid and anthracycline chemotherapy: characteristics, outcome, and prognostic factors. Blood. 2009;113:775–783. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SY, Yue P, Mao L, Dawson MI, Shroot B, Lamph WW, Heyman RA, Chandraratna RA, Shudo K, Hong WK, Lotan R. Identification of receptor-selective retinoids that are potent inhibitors of the growth of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1563–1573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu J, Batuwangala M, Herbert K, Symonds P. Retinoic acid and retinoid receptors: potential chemopreventive and therapeutic role in cervical cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:712–720. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70319-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schütz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, Evans RM. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RA, Mangelsdorf DJ, Dyck JA, Stein RB, Eichele G, Evans RM, Thaller C. 9-cis retinoic acid is a high affinity ligand for the retinoid X receptor. Cell. 1992;68:397–406. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90479-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elstner E, Müller C, Koshizuka K, Williamson EA, Park D, Asou H, Shintaku P, Said JW, Heber D, Koeffler HP. Ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and retinoic acid receptor inhibit growth and induce apoptosis of human breast cancer cells in vitro and in BNX mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8806–8811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPAR gamma 2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell. 1994;79:1147–1156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller E, Sarraf P, Tontonoz P, Evans RM, Martin KJ, Zhang M, Fletcher C, Singer S, Spiegelman BM. Terminal differentiation of human breast cancer through PPARγ. Mol Cell. 1998;1:465–470. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh N, Wang Y, Williams CR, Risingsong R, Gilmer T, Willson TM, Sporn MB. A new ligand for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-gamma). GW7845, inhibits rat mammary carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5671–5673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonofiglio D, Aquila S, Catalano S, Gabriele S, Belmonte M, Middea E, Qi H, Morelli C, Gentile M, Maggiolini M, Andò S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activates p53 gene promoter binding to the nuclear factor-kappaB sequence in human MCF7 breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:3083–3092. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonofiglio D, Gabriele S, Aquila S, Catalano S, Gentile M, Middea E, Giordano F, Andò S. Estrogen receptor alpha binds to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) response element and negatively interferes with PPAR gamma signalling in breast cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6139–6147. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonofiglio D, Gabriele S, Aquila S, Qi H, Belmonte M, Catalano S, Andò S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activates fas ligand gene promoter inducing apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113:423–434. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9944-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elstner E, Williamson EA, Zang C, Fritz J, Heber D, Fenner M, Possinger K, Koeffler HP. Novel therapeutic approach: ligands for PPARγ and retinoid receptors induce apoptosis in bcl-2-positive human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;74:155–165. doi: 10.1023/a:1016114026769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa K, Ishihara T, Aoto M, Inamasu M, Kitamura K, Saito A. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione induces eccentric cardiac hypertrophy by cardiac volume overload in rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;31:8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2004.03954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangwala SM, Lazar MA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in diabetes and metabolism. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staels B. Fluid retention mediated by renal PPARgamma. Cell Metab. 2005;2:77–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinaire JA, Reifel-Miller A. Therapeutic potential of retinoid x receptor modulators for the treatment of the metabolic syndrome. PPAR Res. 2007;2007:94156. doi: 10.1155/2007/94156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C, Nguyen T, Stewart J, Samudio I, Burghardt R, Safe S. Estrogen up-regulation of p53 gene expression in MCF-7 breast cancer cells is mediated by calmodulin kinase IV-dependent activation of a nuclear factor κB/CCAAT-binding transcription factor-1 complex. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:1793–1809. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman ME, Katzenellenbogen BS. Response-specific antiestrogen resistance in a newly characterized MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line resulting from long-term exposure to trans-hydroxytamoxifen. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;59:121–134. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(96)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews NC, Faller DV. A rapid micropreparation technique for extraction of DNA-binding proteins from limiting numbers of mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:2499. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.9.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossarizza A, Baccarani-Contri M, Kalashnikova G, Franceschi C. A new method for the cytofluorimetric analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential using the J-aggregate forming lipophilic cation 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′ tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbo-cyanine iodide (JC-1). Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;197:40–45. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta RG, Williamson E, Patel MK, Koeffler HP. A ligand of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, retinoids, and prevention of preneoplastic mammary lesions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:418–423. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.5.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe DL, Chandraratna RA. A retinoid X receptor (RXR)-selective retinoid reveals that RXR-alpha is potentially a therapeutic target in breast cancer cell lines, and that it potentiates antiproliferative and apoptotic responses to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R546–R555. doi: 10.1186/bcr913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiley ST, Reers M, Mottola-Hartshorn C, Lin M, Chen A, Smith TW, Steele GD, Chen LB. Intracellular heterogeneity in mitochondrial membrane potentials revealed by a J-aggregate forming lipophilic cation JC-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3671–3675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer SA, Umesono K, Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM. Retinoid X receptor interacts with nuclear receptors in retinoic acid, thyroid hormone, and vitamin D3 signaling. Nature. 1992;355:446–449. doi: 10.1038/355446a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XK, Hoffmann B, Tran PBV, Graupner G, Pfahl M. Retinoid X receptor is an auxiliary protein for thyroid hormone and retinoic acid receptors. Nature. 1992;355:441–445. doi: 10.1038/355441a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubouchi Y, Sano H, Kawahito Y, Mukai S, Yamada R, Kohno M, Inoue K, Hla T, Kondo M. Inhibition of human lung cancer cell growth by the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ agonists through induction of apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:400–405. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura S, Miyazaki Y, Shinomura Y, Kondo S, Kanayama S, Matsuzawa Y. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ induces growth arrest and differentiation markers of human colon cancer cells. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1999;90:75–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1999.tb00668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts-Thomson SJ. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptors in tumorigenesis: targets of tumor promotion and treatment. Immunol Cell Biol. 2000;78:436–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetri GD, Fletcher CDM, Mueller E, Sarraf P, Naujoks R, Campbell N, Spiegelman BM, Singer S. Induction of solid tumor differentiation by the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ ligand troglitazone in patients with liposarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3951–3956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee LD, Williams N, Wen P, Young DC, Lester J, Johnson MV, Farrar WB, Walker MJ, Povoski SP, Suster S, Eng C. Pilot study of rosiglitazone therapy in women with breast cancer: effects of short-term therapy on tumor tissue and serum markers. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:246–252. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc BP, Stunnenberg HG. 9-cis retinoic acid signaling: changing partners causes some excitement. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1811–1816. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.15.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee MF, Tsuchida R, Eichler-Jonsson C, Das B, Baruchel S, Malkin D. Vascular endothelial growth factor acts in an autocrine manner in rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines and can be inhibited with all-trans-retinoic acid. Oncogene. 2005;24:8025–8037. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi Y, Wada A, Nakagawa K, Ito M, Okano T. Antitumoral activity of 13-demethyl or 13-substituted analogues of all-trans retinoic acid and 9-cis retinoic acid in the human myeloid leukemia cell line HL-60. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:1803–1809. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H, Hong WK, Lotan R. Increased retinoic acid responsiveness in lung carcinoma cells that are nonresponsive despite the presence of endogenous retinoic acid receptor (RAR) beta by expression of exogenous retinoid receptors retinoid X receptor alpha, RAR alpha, and RAR gamma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:556–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K, DuPré E, Kim H, Tin-U CK, Bissonnette RP, Lamph WW, Brown PH. Receptor-selective retinoids inhibit the growth of normal and malignant breast cells by inducing G1 cell cycle blockade. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;96:147–157. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone AM, Tari AM. How retinoids regulate breast cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:1475–1484. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4002-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff ED, Gottardis MM, Moon TE, Heyman RA, Lamph WW. Beyond tamoxifen: the retinoid X receptor selective ligand LGD1069 (TARGRETIN) causes complete regression of mammary carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1998;58:479–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grommes C, Landreth GE, Heneka MT. Antineoplastic effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:419–429. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01509-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez E, Rosenfeld J, Livolsi A, Olson P, Lombardo E, Nelson M, Banayo E, Cardiff RD, Izpisua-Belmonte JC, Evans RM. PPARgamma signaling exacerbates mammary gland tumor development. Genes Dev. 2004;18:528–40. doi: 10.1101/gad.1167804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn MB, Suh N, Mangelsdorf DJ. Prospects for prevention and treatment of cancer with selective PPARgamma modulators (SPARMs). Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:395–400. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Southard RC, Kilgore MW. The increased expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma1 in human breast cancer is mediated by selective promoter usage. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5592–5596. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SW, Kang BY, Kim SH, Pak YK, Cho D, Trinchieri G, Kim TS. Oxidized low density lipoprotein inhibits interleukin-12 production in lipopolysaccharide-activated mouse macrophages via direct interactions between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ and nuclear factor κB. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32681–32687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier C, Brouillet A, Couriaud C, Koumanov K, Bereziat G, Andreani M. Interleukin 1beta induces type II-secreted phospholipase A2 gene in vascular smooth muscle cells by a nuclear factor κB and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-mediated process. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23085–23093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun YX, Wright HT, Janciasukiene S. Alpha1-antichymotrypsin/Alzheimer’s peptide Abeta (1–42) complex perturbs lipid metabolism and activates transcription factors PPARγ and NFκB in human neuroblastoma (Kelly) cells. J Neurosci Res. 2002;67:511–522. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikawa H, Kameda H, Kamitani H, Baek SJ, Nixon JB, His LC, Eling TE. Effect of PPAR activators on cytokine stimulated cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human colorectal carcinoma cells. Exp Cell Res. 2001;267:73–80. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlezinger JJ, Jensen BA, Mann KK, Ryu HY, Sherr DH. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-mediated NFkB activation and apoptosis in pre-B cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:6831–6841. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlden JM, Hutcheson IR, Jones HE, Madden T, Gee JMW, Harper ME, Barrow D, Wakeling AE, Nicholson RI. Elevated levels of EGFR/c-erbB2 heterodimers mediate an autocrine growth regulatory pathway in tamoxifen-resistant MCF-7 cells. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1032–1044. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HE, Goddard L, Gee JMW, Hiscox S, Rubini M, Barrow D, Knowlden JM, Williams S, Wakeling AE, Nicholson RI. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling and acquired resistance to gefitinib (ZD1839, Iressa) in human breast and prostate cancer cells. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11:793–814. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscox S, Morgan L, Green TP, Barrow D, Gee J, Nicholson RI. Elevated Src activity promotes cellular invasion and motility in tamoxifen resistant breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;7:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.