Abstract

AIM: To investigate the prevalence and demography of microscopic colitis in patients with diarrhea of unknown etiology and normal colonoscopy in Turkey.

METHODS: Between March, 1998 to July, 2005, 129 patients with chronic non-bloody diarrhea of unexplained etiology who had undergone full colonoscopy with no obvious abnormalities were included in the study. Two biopsies were obtained from all colonic segments and terminal ileum for diagnosis of microscopic colitis. On histopathologic examination, criteria for lymphocytic colitis (intraepithelial lymphocyte ≥ 20 per 100 intercryptal epithelial cells, change in surface epithelium, mononuclear infiltration of the lamina propria) and collagenous colitis (subepithelial collagen band thickness ≥ 10 μm) were explored.

RESULTS: Lymphocytic colitis was diagnosed in 12 (9%) patients (Female/Male: 7/5, mean age: 45 year, range: 27-63) and collagenous colitis was diagnosed in only 3 (2.5%) patients (all female, mean age: 60 years, range: 54-65).

CONCLUSION: Biopsy of Turkish patients with the diagnosis of chronic non-bloody diarrhea of unexplained etiology and normal colonoscopic findings will reveal microscopic colitis in approximately 10% of the patients. Lymphocytic colitis is 4 times more frequent than collagenous colitis in these patients.

Keywords: Diarrhea of unknown etiology, Microscopic colitis, Lymphocytic colitis, Collagenous colitis

INTRODUCTION

Chronic diarrhea with no obvious reason is one of the challenges of gastroenterology. In 1980, Read et al[1] introduced microscopic colitis characterized by chronic diarrhea with normal endoscopic and radiologic findings, but with increased colonic mucosal inflammatory cells and epithelial lymphocytic infiltration on histologic examination. Later, Levison et al[2] emphasized that microscopic colitis covered all cases of colitis with normal colonoscopy, but abnormal histopathologic features and described lymphocytic colitis separately. Collagenous colitis, which is a closely related condition, was first described in 1976 as a separate subtype with additional histological finding of increased subepithelial collagen band thickness[3]. Thus, microscopic colitis is a condition with two subtypes having similar clinical, but different histological characteristics. In collagenous colitis subepithelial collagenous band thickness is important.

The prevalence of microscopic colitis has been difficult to estimate. The symptoms of microscopic colitis have been frequently attributed to diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome, often for many years before diagnosis. Diagnostic awareness of these conditions by physicians in the geographic area of interest significantly effects the likelihood of diagnosis and, therefore, the prevalence.

Clinical and histological characteristics of micro-scopic colitis have been well established[4–8]. However, limited data is available regarding the prevalence, pathogenesis and progress of the disease and its treatment. The diagnosis is made only by histologic examination and most of these patients are treated and followed up erroneously as irritable bowel syndrome. Recently, several studies from Sweden and Iceland reported high prevalence of microscopic colitis[9–11]. In this prospective study we aimed to determine the prevalence of lymphocytic and collagenous colitis in Turkey in a subset of patients with chronic non-bloody diarrhea of unknown origin in which colonoscopy was not conclusive.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Between March, 1998 and July, 2005, in three centers around Istanbul (two gastroenterology clinics and one private endoscopy laboratory), 129 consecutive patients with unexplained chronic (at least 3 mo duration), non-bloody diarrhea have undergone colonoscopy with visualization of terminal ileum and normal mucosal appearance noted. These patients were included in the study. Inclusion criteria are shown in Table 1. All patients underwent abdominal ultrasonography and/or computer tomography (CT). Patients who received radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or who had undergone operation related to bowel, stomach or gallbladder or patients with inflammatory bowel disease, chronic liver disease, renal disease or pancreatitis, and patients with the history of long term laxative and antibiotic use were excluded from the study. Stool consistency (liquid, semiliquid, soft), number of daily defecation, duration of diarrhea, and other gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, weight loss, etc) and previous medication were recorded.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria for study

| Inclusion criteria |

| Diarrhea without blood (> 3 mo) |

| Normal stool microscopy |

| No growth in stool culture |

| Normal D-Xylose absorption test |

| Normal biochemical profile |

| Normal thyroid tests, normal serum gastrin |

| Negative antigliadin antibodies (IgA, IgG) |

| Negative Clostridium difficile toxins (A, B) |

| Negative HIV test |

| Normal urine 5-HIAA |

| Normal upper GI endoscopy |

| Normal abdominal US |

| Normal small bowel radiology |

| Normal duodenal biopsy |

| Normal colonoscopy including terminal ileum |

Colonoscopy and histology

Patients were prepared for colonoscopy with 90 mL oral monobasic sodium phosphate and dibasic sodium phosphate. During colonoscopy two biopsies were taken from terminal ileum and all segments of the colon. Specimens were stained with HE and Masson’s Trichrome or Van Gieson dyes.

Diagnostic criteria

Increased chronic inflammatory infiltration in the lamina propria, increased intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs), degeneration of surface epithelium and increased mitosis in crypts were sought for the diagnosis of microscopic colitis. Over 20 IEL per 100 intercryptal epithelial cells (normal < 1-5/100) were deemed necessary for the diagnosis of lymphocytic colitis[7,8,12] (Table 2). For collagenous colitis subepithelial collagen band thickness was measured by ocular micrometer in Masson’s Trichrome stained specimens. Thickness over 10 μm was required for the diagnosis[7,8,12] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Histopathologic criteria for diagnosis of lymphocytic colitis and collagenous colitis

| Histopathologic criteria | |

| Lymphocytic colitis | Chronic inflammatory infiltration in lamina propria |

| Increased IELs | |

| Superficial epithelial degeneration and increased mitosis in crypts | |

| IELs/100 intercryptal epithelial cell > 20/100 | |

| Collagenous colitis | A diffusely distributed and thickened sube-pithelial collagen band > 10 μm |

| Chronic inflammatory infiltration in lamina propria |

RESULTS

During the mentioned period, colonoscopy was performed in a total of 9862 patients due to various reasons. One hundred and twenty-nine of those patients had chronic non-bloody diarrhea with no apparent cause even after laboratory and radiologic examination and full colonoscopy with terminal ileal visualization. These patients were included in the study. After colonoscopic biopsy of colonic segments in 114 patients, histopathologic examinations of colonic biopsies were normal. In all patients, biopsies from terminal ileum revealed normal epithelial features.

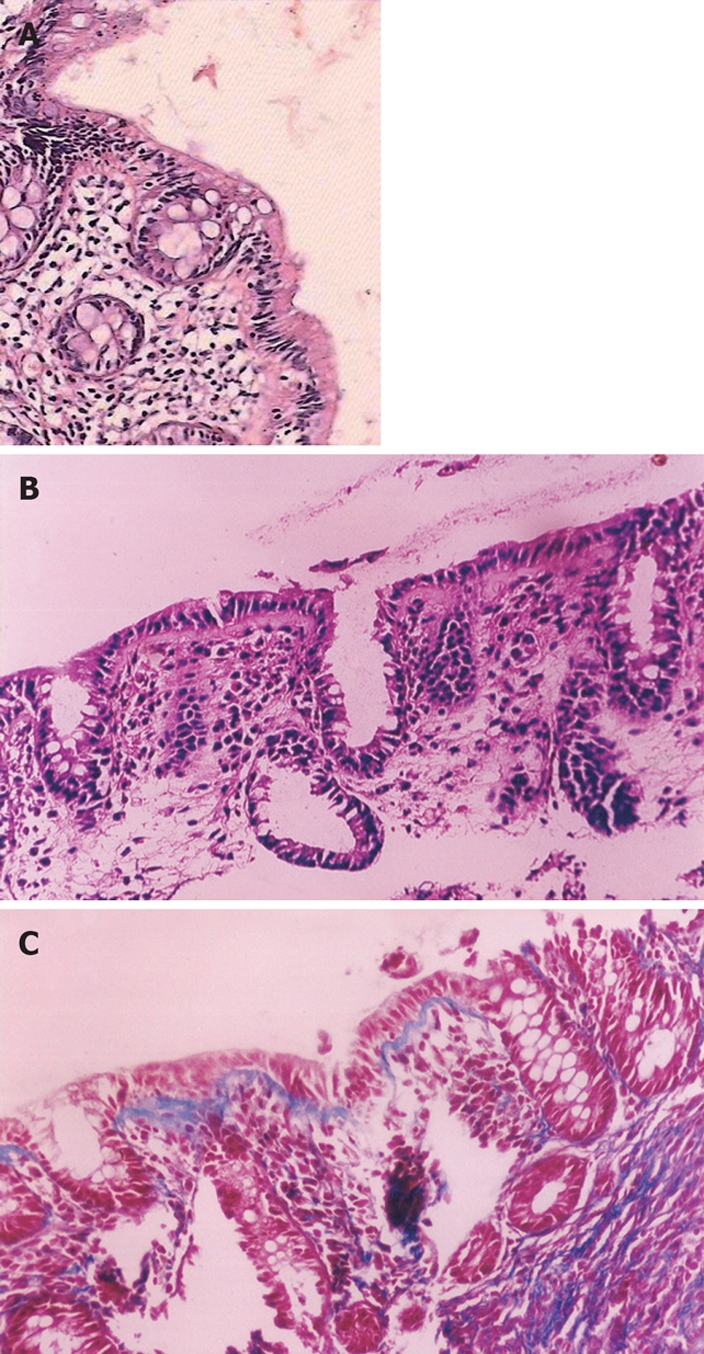

Fifteen patients (11.5%) had microscopic colitis (12 lymphocytic colitis and 3 collagenous colitis; 9%, 2.5%, respectively) (Figure 1A and B). Seven of the lymphocytic colitis patients were female, mean age was 45 ± 11.6 (27-63), mean duration of diarrhea was 22 mo (4-96) and mean number of daily defecation was 5 (3-9). Criteria of lymphocytic colitis were present in specimens obtained from all segments of the colon of these patients. Mean number of IEL per 100 intercryptal epithelial cells was 28.2 ± 6.8 (range 20-60) (Figure 1A). All patients with collagenous colitis were female (ages 65, 54 and 61 years) and their subepithelial collagenous band thickness was 31, 21 and 17.5 μm (Figure 1B and C). Mean durations of diarrhea were 34, 11 and 68 mo and mean daily stool frequencies were 5, 8 and 4 times, respectively.

Figure 1.

Pathologic view (× 200). A: Lymphocytic colitis. Note the increased number of chronic inflammatory cells in the lamina propria and within the surface epithelium (HE); B: Collagenous colitis. Note the subepithelial thick collagenous band (HE); C: Collagenous band thickness on Mason trichrome dye.

DISCUSSION

Microscopic colitis, which is characterized by chronic watery diarrhea with normal radiological and endoscopic appearances, is diagnosed only by histopatologic examination. This condition which consists of two main subtypes (lymphocytic and collagenous colitis) is a relatively common cause of chronic watery diarrhea, often accompanied by abdominal pain and weight loss.

Studies from different countries reported microscopic colitis rates between 4%-13% in the cohort of population with non-bloody diarrhea of unknown origin[10–15]. In the current study, we found this rate to be 11.5% in Turkey.

Diagnosis of this condition is possible only with the awareness of health workers and careful assessment of the criteria. Therefore, the reported prevalence seems to change within years. In Sweden, microscopic colitis was reported in 4% of patients with non-bloody chronic diarrhea in 1993, but this rate was reported as 10% in 1998[9,10,13]. The prevalence of collagenous colitis in Sweden between 1984-1988 was 0.8/105 inhabitants, but increased to 6.1/105 inhabitants between 1996-1998[9,10,13,15]. Recently, higher prevalence values have been reported from Iceland where the mean annual prevalence of collagenous colitis was 5.2/105 inhabitants and the mean annual incidence of lymphocytic colitis was 4.0/105 inhabitants in the period 1995-1999[11]. According to various studies prevalence of collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis is 10-15.7/100 000 and 14.4/100 000, respectively[12–14,16].

In a study performed in Spain, lymphocytic colitis was found in 9.5% of patients who had undergone colonoscopy because of chronic diarrhea during a period of 5 years[14]. In this study, the prevalence of lymphocytic colitis was three times that of the prevalence of collagenous colitis, female/male ratio in lymphocytic and collagenous colitis was found 2.7/1 and 4.7/1, respectively. Female/male ratio were reported as 5/1 from Iceland and 2.1 from Sweden[10–15]. In reported series this ratio for collagenous colitis was found as 4/1-20/1[13–17]. In our study, female/male ratio for lymphocytic colitis was 1.4/1 and lymphocytic colitis was 4 times more than that of collagenous colitis.

Marshall et al[18] encountered 13 lymphocytic colitis and 1 collagenous colitis in their 111 chronic-diarrhea patients with unexplained etiology. In another study of 132 consecutive patients who had undergone colonoscopy for chronic diarrhea and abdominal pain, lymphocytic and collagenous colitis found in 21 (16%) and 7 (5%) of patients, respectively[19].

Mean ages of the patients with lymphocytic and collagenous colitis in other studies were between 51-59 years, and 64-68 years, respectively[13–17]. In our study, the mean age of the patients with lymphocytic colitis was 45 years (range 27-63). The mean age of our three collagenous colitis patients was 60 years.

In the studies of Lazenby et al and Baert et al, the mean IEL per 100 intercryptal epithelial cells was 34.7 and 29.4, respectively[5,8]. In the current study, the mean IEL per 100 intercryptal epithelial cells was 28.2. Normal subjects may have up to 1 to 5 IEL per 100 intercryptal epithelial cells. Some studies have reported that biopsy specimens from all segments of the colon revealed similar number of IEL and, therefore, biopsy obtained only from sigmoid colon would was enough for diagnosis[7,8,12]. In our study, the number of IEL was increased in all bowel segments.

Since subepithelial band thickness was less than 8 μm in all our cases of lymphocytic colitis, the diagnosis of collagenous colitis and overlapping form was excluded. In normal subjects subepithelial collagen band thickness of 5-7 μm is considered as normal and band thickness of 7-80 μm is found in collagenous colitis[7,8,12]. In our 3 collagenous colitis patients the mean band thickness was 23 μm.

As yet, the etiology of lymphocytic colitis has not been well understood. Gastrointestinal infections, autoimmune diseases and various drugs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ranitidine, carbamazepine, simvastatin, ticlopidine, flutamide etc) were reported to be causative factors[12,16,17,20]. Some gastrointestinal rheumatologic disorders (celiac sprue, rheumatoid arthritis, uveitis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, autoimmune thyroiditis etc) and positivity of some autoantibodies, particularly antinuclear antibody (ANA) may be associated with both lymphocytic and collagenous colitis[14,21–24]. Giardiello et al found 4 ANA positive patients in their 12 lymphocytic colitis patients[24]. We found only one case of ANA positivity in our patients, but none of them were associated with any of the disorders or conditions mentioned above.

Patients with lymphocytic colitis were reported to be effectively treated with medications used in inflammatory bowel disease such as sulfasalazine and 5-ASA. If this regiment fails, bismuth subsalicylate, corticosteroids, azathioprine and cyclosporine may be given[12,15–17,25,26]. In the present study sulfasalazine or 5-ASA was used as first line treatment agents. Preliminary results show positive response in terms of symptom relief. Evaluation of long term outcome should wait completion of the study.

In conclusion, considering 11.5% of the patients with chronic diarrhea of unknown etiology and normal colonoscopy would have microscopic colitis, biopsy should be taken during colonoscopy in this subset of patients. Although the number of our cases was not enough to answer the question of how many biopsies should be taken and from which part of the colon, the fact that histopathological criteria were determined on all colonic regions in patients with lymphocytic colitis on whom biopsy was performed is promising in terms of diagnostic convenience. Lymphocytic colitis in Turkish patients was found to be 4 times more frequent than collagenous colitis.

COMMENTS

Background

Microscopic colitis is a chronic diarrheal disease with normal colonoscopic, but with abnormal histopathologic features. It is a disease with two subtypes of similar clinical but different histological features; lymphocytic colitis, which is characterized by pronounced colonic mucosal lymphocyte infiltration and collagenous colitis, which is characterized by increased subepithelial collagenous band thickness. In limited number of studies from various countries the rates of microscopic colitis in patients with chronic diarrhea have been reported between 4%-13%.

Research frontiers

Although the number of the cases was not enough to answer the question of how many biopsies should be taken and from which part of the colon, the fact that histopathological criteria were determined on all colonic regions in patients with lymphocytic colitis on whom biopsy was performed is promising in terms of diagnostic convenience.

Applications

Considering 11.5% of the patients with chronic diarrhea of unknown etiology and normal colonoscopy would have microscopic colitis, biopsy should be taken during colonoscopy in this subset of patients.

Terminology

Microscopic colitis is characterized by chronic watery diarrhea with normal radiological and endoscopic appearances. Lymphocytic colitis has similar characteristics with over 20 intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) per 100 intercryptal epithelial cells. Collagenous colitis has same characteristics with additional histological finding of increased subepithelial collagen band thickness.

Peer review

This is an epidemiologic study confirming findings reported from other countries about the frequency of lymphocytic and collagenous colitis and the importance of biopsies for the diagnosis. It’s a nice paper, well written and well designed.

Peer reviewers: Karel Geboes, Professor, Laboratory of Histo- and Cytochemistry, University Hospital K.U. Leuven, Capucienenvoer 33, Leuven 3000, Belgium; Christina Surawicz, MD, Christina Surawicz, Harborview Medical Center, 325 9th Ave, #359773, Seattle WA 98104, United States

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Rippe RA E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Read NW, Krejs GJ, Read MG, Santa Ana CA, Morawski SG, Fordtran JS. Chronic diarrhea of unknown origin. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:264–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levison DA, Lazenby AJ, Yardley JH. Microscopic colitis cases revisited. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1594–1596. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90194-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindstrom CG. 'Collagenous colitis' with watery diarrhoea-a new entity? Pathol Eur. 1976;11:87–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kingham JG, Levison DA, Ball JA, Dawson AM. Microscopic colitis-a cause of chronic watery diarrhoea. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;285:1601–1604. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6355.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazenby AJ, Yardley JH, Giardiello FM, Jessurun J, Bayless TM. Lymphocytic ("microscopic") colitis: a comparative histopathologic study with particular reference to collagenous colitis. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:18–28. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veress B, Lofberg R, Bergman L. Microscopic colitis syndrome. Gut. 1995;36:880–886. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.6.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullhaupt B, Guller U, Anabitarte M, Guller R, Fried M. Lymphocytic colitis: clinical presentation and long term cou-rse. Gut. 1998;43:629–633. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.5.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baert F, Wouters K, D'Haens G, Hoang P, Naegels S, D'Heygere F, Holvoet J, Louis E, Devos M, Geboes K. Lymphocytic colitis: a distinct clinical entity? A clinicopathological confrontation of lymphocytic and collagenous colitis. Gut. 1999;45:375–381. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.3.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olesen M, Eriksson S, Bohr J, Jarnerot G, Tysk C. Microscopic colitis: a common diarrhoeal disease. An epidemiological study in Orebro, Sweden, 1993-1998. Gut. 2004;53:346–350. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.014431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olesen M, Eriksson S, Bohr J, Jarnerot G, Tysk C. Lymphocytic colitis: a retrospective clinical study of 199 Swedish patients. Gut. 2004;53:536–541. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.023440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agnarsdottir M, Gunnlaugsson O, Orvar KB, Cariglia N, Birgisson S, Bjornsson S, Thorgeirsson T, Jonasson JG. Collagenous and lymphocytic colitis in Iceland. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1122–1128. doi: 10.1023/a:1015058611858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pardi DS, Smyrk TC, Tremaine WJ, Sandborn WJ. Microscopic colitis: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:794–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bohr J, Tysk C, Eriksson S, Jarnerot G. Collagenous colitis in Orebro, Sweden, an epidemiological study 1984-1993. Gut. 1995;37:394–397. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.3.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez-Banares F, Salas A, Forne M, Esteve M, Espinos J, Viver JM. Incidence of collagenous and lymphocytic colitis: a 5-year population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:418–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bohr J, Tysk C, Eriksson S, Abrahamsson H, Jarnerot G. Collagenous colitis: a retrospective study of clinical presentation and treatment in 163 patients. Gut. 1996;39:846–851. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.6.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loftus EV. Microscopic colitis: epidemiology and treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:S31–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.amjgastroenterol.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zins BJ, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ. Collagenous and lymphocytic colitis: subject review and therapeutic alternatives. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1394–1400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall JB, Singh R, Diaz-Arias AA. Chronic, unexplained diarrhea: are biopsies necessary if colonoscopy is normal? Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:372–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gineston JL, Sevestre H, Descombes P, Viot J, Sevenet F, Davion T, Dupas JL, Capron JP. [Biopsies of the endoscopically normal rectum and colon: a necessity. Incidence of collagen colitis and microscopic colitis] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1989;13:360–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomson RD, Lestina LS, Bensen SP, Toor A, Maheshwari Y, Ratcliffe NR. Lansoprazole-associated microscopic colitis: a case series. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2908–2913. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sylwestrowicz T, Kelly JK, Hwang WS, Shaffer EA. Collagenous colitis and microscopic colitis: the watery diarrhea-colitis syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:763–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DuBois RN, Lazenby AJ, Yardley JH, Hendrix TR, Bayless TM, Giardiello FM. Lymphocytic enterocolitis in patients with 'refractory sprue'. JAMA. 1989;262:935–937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Netzer P, Levkovits H, Zimmermann A, Halter F. [Collagen colitis and lymphocytic (microscopic) colitis: different or common origin?] Z Gastroenterol. 1997;35:681–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giardiello FM, Lazenby AJ, Bayless TM, Levine EJ, Bias WB, Ladenson PW, Hutcheon DF, Derevjanik NL, Yardley JH. Lymphocytic (microscopic) colitis. Clinicopathologic study of 18 patients and comparison to collagenous colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1730–1738. doi: 10.1007/BF01540051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pardi DS, Ramnath VR, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, Sandborn WJ. Lymphocytic colitis: clinical features, treatment, and outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2829–2833. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdo AA, Beck P. Diagnosis and management of microscopic colitis. Can Fam Physician. 2003;49:1473–1478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]