Abstract

The preparation of a gapped pUC18 derivative, containing the lacZα reporter gene in the single-stranded region, is described. Gapping is achieved by flanking the lacZα gene with sites for two related nicking endonucleases, enabling the excision of either the coding or non-coding strand. However, the excised strand remains annealed to the plasmid through non-covalent Watson–Crick base-pairing; its removal, therefore, requires a heat–cool cycle in the presence of an exactly complementary competitor DNA. The gapped plasmids can be used to assess DNA polymerase fidelity using in vitro replication, followed by transformation into Escherichia coli and scoring the blue/white colony ratio. Results found with plasmids are similar to the well established method based on gapped M13, in terms of background (∼0.08% in both cases) and the mutation frequencies observed with a number of DNA polymerases, providing validation for this straightforward and technically uncomplicated approach. Several error prone variants of the archaeal family-B DNA polymerase from Pyrococcus furiosus have been investigated, illuminating the potential of the method.

INTRODUCTION

DNA polymerases play a central role in cellular DNA replication and repair and are used for a number of biotechnology purposes such as DNA sequencing and the polymerase chain reaction (1–6). The accuracy of DNA polymerases is critical both for in vivo functions and in vitro applications, necessitating simple methods for measuring fidelity. Many polymerases, particularly those involved in replication of the genome, are very accurate often making only a single mistake per 105/106 bases incorporated (7,8). Therefore, fidelity assays must be capable of measuring the occasional rare mistake, occurring in a background of faithful replication. A popular method uses the lacZ α-complementation gene (lacZα), which encodes the α-peptide, an inactive segment of β-galactosidase. The presence of the lacZα gene in complementing Escherichia coli strains (which contain a chromosomal copy of the remaining β-galactosidase gene fragment) results in the reconstitution of a functional β-galactosidase, giving blue colonies on media supplemented with X-gal. A general approach involves the use of a gapped M13 DNA, containing the lacZα gene in the single-stranded region (9,10). A polymerase is used to fill in the gap and the product introduced into E. coli cells, which are plated on media containing X-gal. Gap filling without mistakes results in a fully functional α-peptide, and the formation of blue plaques. Errors give rise to changes in the lacZα coding sequence, which can result in a defective α-peptide and the appearance of white plaques. The ratio of white/blue plaques is a reflection of fidelity, the higher the proportion of white plaques the less accurate the polymerase. Further information can be obtained by sequencing white plaques, which reveals the exact nature of the base-pair change. An alternative, applicable to thermostable DNA polymerases, involves PCR amplification of a fragment encoding lacIOZα and subsequent insertion of the amplicons into λgt10 phage vector (7,11). Here, errors during the copying of lacI, the gene encoding the lac repressor, are scored. Mistakes by the polymerase lead to a defective lac repressor, allowing transcription of the lacZα gene and, therefore, the appearance of blue plaques. A high blue/white plaque ratio indicates a polymerase of poor fidelity. A plasmid-based assay using the Cro gene has also been described (12). However, the preparation of the required gapped plasmid was somewhat unwieldy, requiring nicking with a restriction endonuclease in the presence of ethidium bromide, followed by digestion with exonuclease III. The protocol results in only half the molecules containing the Cro gene in the single-stranded region, necessitating corrections to the observed mutation frequency. Mistakes in filling the gap give a Cro− phenotype, scored as red colonies, and the method has been used to investigate the error prone DNA polymerase V. A plasmid system based on the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene is known, although its use to assay polymerase fidelity in vitro is somewhat convoluted, involving multiple steps (13). Finally, a fully double-stranded plasmid containing oriC and a streptomycin-selectable marker (the rpsL gene, encoding the small ribosomal S12 protein) has been described (14). However, experiments can only be performed with fully reconstituted replisomes, capable of DNA synthesis from OriC, and not with isolated polymerases. In this publication an alternative fidelity assay, based on gapped plasmids containing the lacZα gene, is described. The substrate plasmids are easy to prepare and the fidelity measurement rapid and straightforward. The method is applicable to the in vitro study of all polymerases and potentially useful for studying DNA replication and repair in vivo in a number of cell types.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) were supplied by Roche (Penzberg, Germany) and were the best quality available (PCR grade). Phusion DNA polymerase (derived from a Pyroccccus species DNA polymerase), T4 DNA polymerase (T4-Pol) and lambda (λ) exonuclease were purchased from New England Biolabs (Hitchin, UK). NtBpu10I and NbBpu10I nicking enzymes, the restriction endonucleases PstI and DpnI and Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase (Taq-Pol) were supplied by Fermentas (York, UK). pUC18 was from Stratagene (Agilent, Stockport, UK). The purification of Pfu-Pol (the following variants were used in this publication: wild type, the 3′-5′ proof-reading exonuclease minus (exo−) mutant D215A, the low-fidelity double mutants Q472G/D215A and D473G/D215A) has been described (15,16). The following E. coli strains were used: Top10 (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and XL-10 Gold (Stratagene).

Site-directed mutagenesis of pUC18 to produce pSJ1

To flank the lacZα gene, present in pUC18, with two sites for each of the related nicking enzymes NtBpu10I (frames the coding strand) and NbBpu10I (frames the non-coding strand), two rounds back-to-back PCR site directed mutagenesis (17) were carried out. The primers GTCATAGCTGAGGCCTGTGTGAAATTGTTATCCGCTCACAATTC and CAATTTCACACAGGCCTCAGCTATGACCATGATTACG were used in the first PCR to generate nicking sites upstream of lacZα. In a second PCR the primers CGGGTGTCGGCTCAGGCTTAACTATGCGGCATCAGAG and CATAGTTAAGCCTGAGCCGACACCCGCCAACACCCGCTGAC were used to produce the downstream nicking sites. The PCR reaction mixture comprised 50 μl of 1× HF buffer supplied with Phusion DNA polymerase, 200 µM of the four dNTPs, 1 µM of forward and reverse primer, ∼300 ng of pUC18 template and 40 U/ml of Phusion DNA polymerase. Nineteen PCR cycles (35 s at 95°C, 40 s at 55°C and 4 min at 70°C) were used. Amplified DNA was purified with PCR clean-up kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK) and subsequently treated with DpnI for 5 h to destroy parental plasmid template. XL-10 Gold (Stratagene) ultra competent cells were transformed with the DNA sample according to the supplier's protocol. Transformants were grown over night at 37°C on LB plates supplemented with ampicillin and used next day to seed 5-ml liquid culture in LB media containing 100 ug/ml of ampicillin. Usually three of the clones were subjected to mini preparative scale DNA extraction (Qiagen) and the presence of the nicking sites and the integrity of the lacZα gene were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Nicking pSJ1 with NtBpu10I and NbBpu10I

Twenty micrograms of pSJ1 was nicked with either NtBpu10I (cuts twice on the coding strand of lacZα) or NbBpu10I (cuts twice on the non-coding strand of lacZα). Reactions were performed for 3 h at 37°C in 1 ml with 100 U of the enzymes and using the buffer recommended by the supplier. The nicked plasmid was purified with a PCR clean up kit (Qiagen).

Preparation of lacZα single-stranded competitor DNA

The lacZα gene, in pUC18, was amplified by PCR using two sets of primers: either pTCAGCTATGACCATGATTACG and GGCTTAACTATGCGGCATCAGAG or TCAGCTATGACCATGATTACG and pGGCTTAACTATGCGGCATCAGAG (where p represents a 5′-phosphate group). The PCR reaction mixture used identical to that described above and 30 cycles (35 s at 95°C, 35 s at 55°C and 30 s at 70°C) were used. The amplified lacZα DNA was purified with a PCR clean-up kit (Qiagen) and subsequently subjected to specific degradation of the 5′ phosphorylated strand using lambda exonuclease (18). The reaction was performed with 2 μg of the PCR product in 50 μl of supplier's buffer using 5 U of lambda exonuclease for 30 min at 37°C. The resulting single-stranded DNA was purified using a nucleotide removal kit (Qiagen).

Preparation of gapped DNA

Nicked pSJ1 was converted to gapped pSJ1(+) and pSJ1(–) using an excess of single-stranded competitor DNA substrates. Ten micrograms of the nicked plasmid was mixed with 10-fold molar excess of the appropriate lacZα single-stranded competitor in 500 μl of 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin and subjected to three cycles of denaturation/re-annealing that consisted of 1 min, 90°C; 10 min, 60°C 20 min, 37°C. The mixture was then treated with 100 U of PstI restriction endonuclease for 3 h at 37°C. Finally, the gapped pSJ1(+) and pSJ1(–) were purified using gel electrophoresis on 1% agarose, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV light. The bands corresponding to the gapped plasmids were extracted with a gel extraction kit (Qiagen) and stored frozen in –20°C until further use. Approximately 3 μg of the gapped plasmid was obtained from each 10 μg of nicked pSJ1.

Background mutation rate determination

To measure background rate of mutations associated with pSJ1, about 40 fmol of nicked pSJ1 (cut singly at either the upstream and downstream nicking sites or double cut at both nicking sites) or gapped pSJ1(+) and pSJ1(–) were added to the DNA polymerase extension buffer (described below). One microlitre of these mixtures were used to transform 30 μl of E. coli Top10 (in a few cases XL-10 Gold) ultra competent cells, which were held on ice for 30 min. The cells were heat shocked by treatment at 42°C for 35 s, held on ice for a further 2 min and then supplemented with 970 μl of NZY medium (lacking ampicillin). Following incubation at 37°C for 1 h, the cells were diluted 20-fold with fresh NZY (plus ampicillin) medium and 100 μl was then plated on LB media supplemented with 20 μg/ml X-Gal, 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 100 μM IPTG. After incubation of the plates at 37°C for 16 h, the plates were scored for blue and colourless colonies.

DNA polymerase fidelity assayed with pSJ1(+) and pSJ1(–)

Three polymerases (Phusion (a Pyrococcus furiosus polymerase derivative), Thermus aquaticus and T4) were used to gap fill pSJ1(+) and pSJ1(–). Reactions (25 μl) contained 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.7), 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 100 μM of each dNTP, 0.8 nM pSJ1(+) or pSJ1(–) and 20 U/ml (units defined by the supplier) of the DNA polymerase. Polymerization reactions were performed at 30°C for 30 min. The completeness of polymerase-catalysed gap-filling was determined using agarose (1%) gel electrophoresis, with ethidium bromide staining and UV visualization. The polymerase reactions products were then used to transform E. coli Top10 for blue/white colony scoring as described above.

DNA sequencing

Single colonies on LB plates were picked and grown overnight at 37°C in LB media containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and plasmids isolated by alkaline mini preparative scale purification using a Qiagen kit. Plasmids were sequenced (GATC-Biotech, Cambridge, UK) using CGTATGTTGTGTGGAATTG as primer. The sequences determined were aligned with the coding strand of the parental lacZα reporter gene present in pSJ1 using Clone Manager Professional Suite 8.0 (Sci-Ed Software, Cary NC, USA).

Fidelity of error prone Pfu-Pol mutants

Four Pfu-Pol variants (wild type, the 3′-5′ exonuclease (exo−) minus variant D215A and two exo– double mutants Q472G/D215A and D473G/D215A) were used to fill pSJ(+). Reactions (20 μl) contained 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgSO4, 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 100 μM of each dNTP, 0.8 nM pSJ1(+) and 50 nM of each polymerase. Polymerization reactions were conducted at 50°C for 35 min and the completeness gap-filling was determined using agarose (1%) gel electrophoresis, with ethidium bromide staining and UV visualization. The polymerase reactions products were then used to transform E. coli Top10 for blue/white colony scoring as described above.

RESULTS

Plasmid preparation

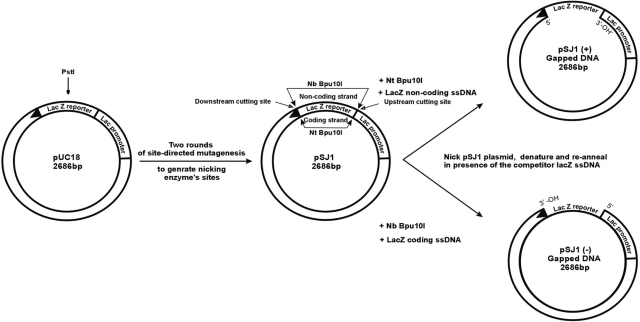

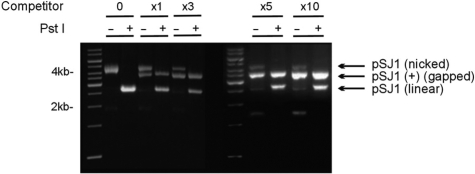

The construction of plasmids suitable for measuring DNA polymerase fidelity begins from pUC18, which contains the lacZα gene (Figure 1). A unique PstI restriction site, in the middle of lacZα is important for subsequent manipulation. Two rounds of site-directed mutagenesis are used to generate pSJ1, in which lacZα is flanked by restriction sites for two, related, nicking endonucleases, Nt.Bpu10I and Nb.Bpu10I. There are no other sites for these enzymes in pSJ1 and, as shown in Figure 1, Nt.Bpu10I and Nb.Bpu10I are able to introduce two nicks at the extremities of the coding and non-coding strands of lacZα, respectively. Following treatment with Nt.Bpu10I or Nb.Bpu10I, we were unable to effectively remove the nicked single-strands, to produce the required gapped plasmids, simply by heating, rapid cooling and separation by gel electrophoresis. As shown in the Figure 2 (lanes labelled ‘0 competitor’) this simple procedure resulted in only nicked pSJ1, with the excised lacZα sequences retained by non-covalent Watson–Crick hydrogen bonding. A subsequent treatment with the PstI restriction endonuclease resulted in a linear plasmid (Figure 2). PstI requires duplex DNA, confirming that the double-nicked single strand remains associated with the gapped plasmid. Inclusion of a single-stranded competitor DNA, exactly complementary to the excised strand, facilitated the production of gapped plasmid. Addition of the competitor, after reaction with Nt.Bpu10I or Nb.Bpu10I and prior to commencing the heat–cool cycle, resulted in two species, the nicked plasmids and, running slightly faster, the desired gapped plasmids, pSJ1(+) and pSJ1(–) (Figure 2). As the amount of competitor increased, more of the required gapped plasmid was produced; a 5-fold excess appearing optimal. Digestion with PstI converted any remaining nicked plasmid to the linear form, but, as expected, the gapped plasmid proved refractory to such treatment. Moreover, the desired gapped plasmid and any linear contaminant produced after PstI digestion are well separated by gel electrophoresis, facilitating purification. It proved straightforward to produce the required single stranded competitor by carrying out PCR of lacZα with one of the primers bearing a 5′-phosphate group. A subsequent treatment with λ exonuclease specially degrades the duplex strand that contains the 5′-phosphate, yielding the competitor (18).

Figure 1.

Gapped plasmids for measuring DNA polymerase fidelity. Site-directed mutagenesis is used to flank the lacZα gene in pUC18 with sites for two related nicking endonucleases, Nt and Nb Bpu10I. Cutting the resulting pSJ1 with these nucleases liberates either the coding or non-coding strand to give pSJ1(+) and pSJ1(–). To completely remove the excised strand from the gapped plasmid it is necessary to add competitor DNA, complementary to the excised region. The unique PstI restriction site is important for analysis and purification.

Figure 2.

Preparation and purification of pSJ1(+). Gel electrophoretic analysis of pSJ1 following treatment with Nt Bpu10I. In the absence of competitor DNA (lanes marked 0) a nicked plasmid, where the excised strand remains associated with the plasmid by Watson–Crick interactions, is produced. Cutting with PstI gives a linear plasmid as the PstI site remains in a double-stranded region. Adding increasing amounts of competitor (excess over plasmid denoted by x1, x3, x5 and x10) progressively gives more of the desired gapped pSJ1(+) at the expense of the nicked intermediate. Treatment with PstI destroys any remained nicked plasmid but not the gapped pSJ1(+) as, in this case, the PstI site is in a single-stranded DNA region.

Background mutation rate

Prior to using pSJ1(+/–) to assess polymerase fidelity, control transformations were carried out to determine background mutation rate. The parent plasmid, pSJ1, and various elaborations which included nicked derivatives (cut at a single site upstream or downstream of lacZα or double-cut at both sites) and the gapped pSJ1(+)/pSJ1(–) were used to transform E. coli Top10. As shown in Table 1, a background mutation rate of about 0.08% (i.e. ∼1 in every 1250 colonies was white) was observed in every case. No significant differences were seen between intact pSJ1 and the nicked and gapped derivatives. The background of ∼0.08%, found with the plasmid-based lacZα system, is similar to the control rates of 0.06–0.07% observed with gapped M13 derivatives (9,10). However, certain E. coli strains, e.g. XL-10, showed a noticeably higher mutation rate of around 0.5% (data not shown), for reasons that are as yet unclear.

Table 1.

Number of colonies observed and mutation rates found in control experiments using pSJ1, pSJ1(+) and pSJ1(–)

| Plasmid | Total coloniesa | Mutant (white) coloniesa | Mutation rate (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| pSJ1 | 4028 | 3 | 0.07 ± 0.007 |

| pSJ1(+) gapped DNA | 7262 | 5 | 0.07 ± 0.005 |

| pSJ1(+) nicked (both sides) DNA | 4946 | 4 | 0.08 ± 0.05 |

| pSJ1(+) nicked (upstream) DNA | 3911 | 3 | 0.08 ± 0.003 |

| pSJ1(+) nicked (downstream) DNA | 4039 | 3 | 0.07 ± 0.004 |

| pSJ1(–) gapped DNA | 4141 | 4 | 0.09 ± 0.02 |

| pSJ1(–) nicked (both sides) DNA | 4212 | 3 | 0.07 ± 0.07 |

| pSJ1(–) nicked (upstream) DNA | 4306 | 4 | 0.09 ± 0.03 |

| pSJ1(–) nicked (downstream) DNA | 4566 | 4 | 0.08 ± 0.03 |

| Combined datac | 41 411 | 33 | 0.08 ± 0.02 |

aThe numbers of total and white colonies are summed from three independent observations in each case.

bMutation rate is defined as (white colonies)/(total colonies) × 100. The figures given are the averages for the three observations ± SD.

cThe combined data represents the sum of all the individual experiments (n = 27).

DNA polymerase fidelity assay

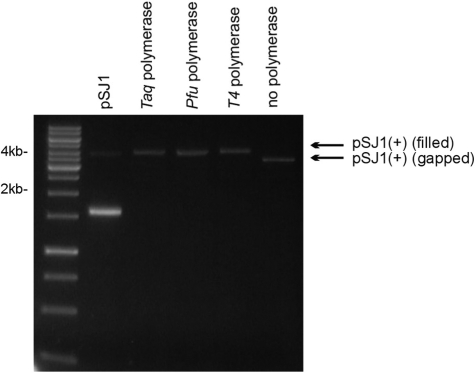

Subsequently three DNA polymerases, the family A polymerase from Thermus aquaticus (Taq-Pol), phage T4 polymerase (T4-Pol) and Phusion, a derivative of the family-B DNA polymerase from Pyrococcus furisosus, (Pfu-Pol) were successfully used to fill in the gapped substrates, pSJ1(+) and pSJ1(–). In each case, as assessed by gel electrophoresis (Figure 3), all three polymerases filled the 337-nt gap without obvious strand displacement. Following polymerase-catalysed gap filling, plasmids were mixed with E. coli Top10 and transformed cells screened for blue and white colonies. The results are summarized in Table 2 which shows that no differences in fidelity were seen when an individual polymerase was assayed using either the (+) or the (–) variants of pSJ1. The accuracy of the polymerases follows the ranking order, Pfu-Pol > T4-Pol > Taq-Pol. The highest mutation rate was seen with Taq-Pol and the corrected value of 0.9% is in excellent agreement with values of between 0.75 and 1.2% found for different batches of this enzyme using the M13 lacZα method (10). The family-A Taq-Pol lacks 3′-5′ proof-reading exonuclease activity, accounting for its relatively low fidelity (10). Lower mutation rates were observed with T4-Pol (0.3%) and Pfu-Pol (0.1%), two family-B DNA polymerases both of which possess 3′-5′ exonuclease activity (11,19). Polymerases with proof-reading activity copy DNA with higher fidelity than enzymes that lack this function (20). Many studies have compared the accuracy of Taq-Pol and Pfu-Pol as both are extensively used in the polymerase chain reaction, an application for which fidelity is an important consideration. The general consensus is that Pfu-Pol has a 10-fold higher fidelity than Taq-Pol (7), agreeing with the results in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Copying pSJ1(+) with DNA polymerases. A standard is provided by pSJ1, which mainly runs as the supercoiled form (prominent fast migrating band) but with traces of the open-circle form due to the presence on nicks. The starting gapped pSJ1(+) (no polymerase) is also show. Treatment with Taq, Pfu and T4 polymerase results in copying of the single stranded region of pSJ1(+) to give a filled derivative, running, as expected, with mobility identical to the open circle form of pSJ1.

Table 2.

Fidelities observed for DNA polymerases using pSJ1(+/–)

| Polymerase/plasmid combination | Total coloniesa | Mutant (white) coloniesa | Observed mutation rate (%)b | Corrected mutation rate (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq-Pol/pSJ1(+) | 4418 | 43 | 1.0 ± 0.14 | 0.9 |

| T4-Pol/pSJ1(+) | 3855 | 16 | 0.4 ± 0.14 | 0.3 |

| Pfu-Pold/pSJ1(+) | 4824 | 10 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 0.1 |

| Taq-Pol/pSJ1(–) | 4173 | 43 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.9 |

| T4-Pol/pSJ1(–) | 4567 | 18 | 0.4 ± 0.14 | 0.3 |

| Pfu-Pold/pSJ1(–) | 4549 | 10 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 0.1 |

| Pfu-Pol (exo–)/pSJ1(+) | 3836 | 52 | 1.3 ± 0.09 | 1.2 |

| Pfu-Pol (exo–, Q472G)/pSJ1(+) | 3485 | 58 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.6 |

| Pfu-Pol (exo–, D473G)/PSJ1(+) | 3527 | 109 | 3.1 ± 0.15 | 3.0 |

aThe numbers of total and white colonies are summed from three independent observations in each case.

bObserved mutation rate is defined as (white colonies)/(total colonies) × 100. The figures given are the averages for the three observations ± SD.

cThe corrected mutation rate has had 0.08% (the average background mutation rate, Table 1) subtracted from the observed value.

dThe Pfu-Pol used in these experiments was Phusion, a derivative of the polymerase fused with a DNA-binding domain and obtained from New England Biolabs.

Mutation spectra by DNA sequencing

The lacZα genes of a number of mutant (white) colonies have been sequenced, to determine the nature of the introduced mutation. The results are given in Table 3 and show that, in all the 10 cases examined, mutations in the controls are characterized by a C→T change in the template strand. It is most likely that these changes are due to the presence of uracil in the single-stranded template regions of the gapped plasmids pSJ1(+) and pSJ1(–). In DNA the deamination of cytosine results in uracil, a thymine mimic which codes for the incorporation of dAMP in progeny strands, ultimately resulting in a C→T transition mutation (21). Such ‘cryptic’ damage is also observed using the M13 lacZα system (22,23) and has been ascribed to template damage during the preparation of the gapped substrates. The gapped plasmids pSJ1(+/–), used for assessing polymerase fidelity, are derived from the parental pSJ1 using a number of in vitro manipulations (Figure 1). Both pSJ1 and pSJ1(+/–) show the same background mutation frequency (Table 1), making it unlikely that significant additional deamination takes place during the conversion of pSJ1 to pSJ1(+/–), e.g. during the treatment with the nicking enzymes Nb.Bpu10I or Nt.Bpu10I. Rather, uracil appears to be present in pSJ1 itself, arising either during its purification or from plasmids that either escaped or were awaiting uracil–DNA–glycosylase (UDG) initiated base excision DNA repair in E.coli (24).The presence of uracil in pSJ1 limits the sensitivity of the assay to a mutation rate of around 0.08%.

Table 3.

Mutation spectra observed using pSJ1(+/–)

| Polymerase/plasmid combination | Template mutation (number)a | Mismatch formed (template:dNMP) |

|---|---|---|

| pSJ1(+) gapped control | C→T (5) | C:A |

| Taq-Pol/pSJ1(+) | ΔG (2) | – |

| G→A (2) | G:T | |

| C→T (2) | C:A | |

| T4-Pol/pSJ1(+) | A→T (5) | A:A |

| Pfu-Pol/pSJ1(+) | A→T (2) | A:A |

| C→T (1) | C:A | |

| G→A (1) | G:T | |

| C→G (1) | C:C | |

| pSJ1(–) gapped control | C→T (5) | C:A |

| Taq-Pol/pSJ1(–) | C→T (5) | C:A |

| T4-Pol/pSJ1(–) | C→T (6) | C:A |

| Pfu-Pol/pSJ1(–) | C→T (2) | C:A |

| G→T (1) | G:A | |

| G→A (3) | G:T |

aFor each polymerase/plasmid combination, five separate mutant (white) clones had their entire lacZα gene (coding strand) sequenced. The changes observed together with their frequencies (number in brackets) are given. In most cases only one mistake was observed per lacZα gene. In two cases [T4-Pol/pSJ1(–) and Pfu-Pol/pSJ1(–)] one of the mutant genes contained two errors, accounting for the total of six mistakes.

The changes in the template strand observed when the gapped pSJ1(+) and pSJ1(–) were filled using three different polymerases are also summarized in Table 3. Including controls, 38 of the 40 mutant plasmids sequenced contained only a single alteration, two having two changes. Similarly, 40 out of 42 mutations resulted from a base substitution, with just two deletions being seen. With pSJ1(+), Taq-Pol and Pfu-Pol gave a variety of mutations, although with T4-Pol it is noticeable that all five changes seen give rise to template strand A→T transitions. Different results were seen with pSJ1(–); with Taq-Pol and T4-Pol all the changes are characterized by C→T transitions, identical to the alterations seen in controls. In the case of Pfu-Pol a wider range of mutations was observed, which may result from the inability of archaeal polymerases to replicate beyond template-strand uracil (25,26), suppressing many of the C→T changes. Determination, by DNA sequencing, of the error spectrum arising with a particular DNA polymerase gives valuable mechanistic information, as extensively demonstrated with the M13-phage lacZα system (10,22,27). However, to obtain robust data, particularly with accurate polymerases which give few errors above background, many sequences need to be determined. In this publication sequencing was primarily used to confirm that white colonies actually arise from changes in DNA sequence and so provide assay validation, rather than to investigate the polymerases per se. Therefore, only a relatively small number of white colonies have had their sequences determined and comments on the polymerase mutation spectra, e.g. whether the C→T changes seen with Taq-Pol/T4-Pol/pSJ1(–) are merely fortuitous sampling of background mutations, are unwarranted at present. All DNA sequences are given in full in the appendix.

Application of pSJ1

Previously our group showed that mutations to three amino acids that comprise a loop in the fingers sub-domain of Pfu-Pol gave low-fidelity variants, useful in error prone PCR (15). Accuracy was assessed using PCR amplification of lacIOZα, where errors introduced by the polymerase during the copying of lacI give rise to a defective lac repressor, allowing transcription of the lacZα gene and the appearance of blue plaques (7,11). Unfortunately, concomitant mistakes in lacZα itself, resulting in an inactive β-galactosidase, interfere with the assay, although these may be controlled for, providing the number of mistakes is not excessive. Although the fidelity of Pfu-Pol could be determined using lacIOZα, the higher error rates of the Pfu-Pol loop mutants made this assay inapplicable and their accuracy was assessed directly by sequencing of PCR amplicons. Comparing Pfu-Pol D215A (exo−) (lacIOZα assay) with one of the loop mutants, Pfu-Pol D473G/D215A exo− (amplicon sequencing), suggested D473G about 14-fold more error prone (15). The use of different assays is unsatisfactory and, therefore, the pSJ1-based method has been used to more rigorously compare the fidelity of two loop mutants, Q472G (exo−) and D473G (exo−), with the exo− parent. Table 2 shows that Pfu-Pol exo− has a mutation rate some 10-fold higher than exo+, in agreement with previous observations (7,15). Changing glutamine 472 or glutamic acid 473 to glycine further increases the mutation rate, by a factor of 1.3 for Q472G and 2.5 for D473G. The pSJ1(+)-based assay shows the difference in fidelity between Pfu-Pol exo– and Pfu-Pol D473G exo− (the mutation rate of Pfu-Pol Q472G exo− was not measured in our earlier publication) to be smaller than previously determined. However, our experience is that D473G exo− is useful in error prone PCR, despite being more accurate than previously suspected.

DISCUSSION

A plasmid-based lacZα system for measuring DNA polymerase fidelity is described. The key steps, used to prepare the desired gapped duplex, are the use of a nicking endonuclease to specifically excise one strand and its complete removal using a complementary oligodeoxynucleotide. Although a plasmid system based on the Cro gene has previously been reported (12), the methods described here to prepare gapped duplex represent a clear advance, with 100% of the product having a single-stranded gapped region. The approach using pSJ1 is conceptually similar to the well established method based on gapped M13 (9), both giving identical background mutation rates of ∼0.08%. The fidelities of three DNA polymerases (Taq, T4 and Pfu) measured using gapped plasmids were very similar to those found with M13, validating the plasmid-based approach. The use of plasmids may represent a simpler system in terms of maintenance and production of reporter DNA, ease of gapped substrate preparation, transformation of cells, analysis of cells (relying on colonies rather than plaques) and recovery of mutated plasmids for DNA sequencing. Further, as plasmids are compatible with virtually all bacteria and many eukaryotes such as yeast, gapped derivatives may be useful for in vivo study of DNA replication and repair, for example using microbes mutated in repair pathways. Obviously the plasmid system is not yet as advanced as the long-established approach based on M13. Thus, although the mutation rates of different polymerases can be ranked, based on the ratio of blue/white colonies, it is not yet possible to determine error frequency, i.e. the mistakes made per nucleotide incorporated by the polymerase. The error frequency can be determined using the following equation (9,10):

Where mf = mutant fraction determined by DNA sequencing, Mr0 and Mrb are the mutation rates observed after polymerase-catalysed replication and background, respectively, fo = frequency of expression of newly synthesized strand, Nd = number of nucleotides within the gapped region known to yield a mutant phenotype. The latter two terms have yet to be evaluated for the plasmid-based system described here. Nevertheless the usefulness and applicability of the pSJ1 system has been established by the experiments with error prone Pfu-Pol loop mutants. Perhaps the most pressing problem, common to both plasmids and M13, is the spontaneous mutation rate of around 0.08%. This is higher than the error rate of many polymerases and makes several important applications, e.g. comparing the fidelities of thermostable polymerases used in the PCR, difficult. With the plasmid system most, if not all, of the background seems to arise from cytosine deamination to uracil, and is already fully present in the parent pSJ1. Lower backgrounds may be achieved using E. coli strains that overexpress UDG (reducing in vivo levels of uracil) or treating pSJ1 with UDG in vitro, to degrade damaged plasmids. Treatment with repair enzymes has been reported to be beneficial with the Cro plasmid system (12).

FUNDING

The UK BBSRC (Project grant BB/F00687X/1); and the European Union (Marie Curie Research Training Network QLK3-CT-2001-00448). Funding for open access charge: UK BBSRC (Project grant BB/F00687X/1).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Pauline Heslop for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Garcia-Diaz M, Bebenek K. Multiple functions of DNA polymerases. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2007;26:105–122. doi: 10.1080/07352680701252817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hübscher U, Nasheuer H.-P, Syväoja JE. Eukaryotic DNA polymerases, a growing family. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:143–147. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01523-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garg P, Burgers P.MJ. DNA polymerases that propagate the eukaryotic DNA replication fork. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005;40:115–128. doi: 10.1080/10409230590935433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prakash S, Johnson RE, Prakash L. Eukaryotic translesion synthesis DNA polymerases: specificity of structure and function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:317–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilton SC, Farchaus JW, Davis MC. DNA polymerases as engines for biotechnology. Biotechniques. 2001;31:370–376. doi: 10.2144/01312rv01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pavlov AR, Pavlova NV, Kozyavkin SA, Slesarev AI. Recent developments in the optimization of thermostable DNA polymerases for efficient applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cline J, Braman JC, Hogrefe HH. PCR fidelity of Pfu DNA polymerase and other thermostable DNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3546–3551. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.18.3546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCulloch SD, Kunkel TA. The fidelity of DNA synthesis by eukaryotic replicative and translesion synthesis polymerases. Cell Res. 2008;18:148–161. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bebenek K, Kunkel TA. Analyzing fidelity of DNA polymerases. Methods Enzymol. 1995;262:217–232. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)62020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tindall KR, Kunkel TA. Fidelity of DNA synthesis by the Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase. Biochemistry. 1998;27:6008–6013. doi: 10.1021/bi00416a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundberg KS, Shoemaker DD, Adams M.WW, Short M, Sorge JA, Mathur EJ. High-fidelity amplification using a thermostable DNA polymerase isolated form Pyrococcus furiosus. Gene. 1991;108:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90480-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maor-Shoshani A, Reuven NB, Tomer G, Livneh Z. Highly mutagenic replication by DNA polymerase V (UmuC) provides a mechanistic basis for SOS untargeted mutagenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:565–570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eckert KA, Mowery A, Hills SE. Misalignment-mediated DNA polymerase β mutations: comparison of microsatellite and frame-shift error rates using a forward mutation assay. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10490–10498. doi: 10.1021/bi025918c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujii S, Akiyama M, Aoki K, Sugaya Y, Higuchi K, Hiraoka M, Miki Y, Saitoh N, Yoshiyama K, Ihara K, et al. DNA replication errors produced by the replicative apparatus of Eschericia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;289:835–850. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biles BD, Connolly BA. Low fidelity Pyrococcus furious DNA polymerase mutants useful in error-prone PCR. Nuleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e176. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans SJ, Fogg MJ, Mamone A, Davis M, Pearl LH, Connolly BA. Improving dideoxynucleotide-triphosphate incorporation by the hyper-thermophilic DNA polymerase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1059–1066. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.5.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng L, Baumann U, Reymond JL. An efficient one-step site directed and site-saturation mutagenesis protocol. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas E, Pingoud A, Friedhoff P. An efficient method for the preparation of long heteroduplex DNA as substrate for mismatch repair by the Escherichia coli MutHLS system. Biol. Chem. 2002;383:1459–1462. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karam JD, Konigsberg WH. DNA polymerase of the T4-related bacteriophages. Prog Nucleic Acids Res. Mol. Biol. 2000;64:65–96. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(00)64002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunkel TA. DNA replication fidelity. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:18251–18254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindahl T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature. 1993;362:709–715. doi: 10.1038/362709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunkel TA, Alexander PS. The base substitution fidelity of eukaryotic DNA polymerases. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:160–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shcherbakova PV, Pavlov YI, Chilkova O, Rogozin IB, Johansson E, Kunkel TA. Unique error signature of the four-subunit yeast DNA polymerase epsilon. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:43770–43780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306893200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krokan HE, Standhal R, Slipphaug G. DNA glycosylases in the base excision repair of DNA. Biochem. J. 1997;325:1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3250001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greagg MA, Fogg MJ, Panayotou G, Evans SJ, Connolly BA, Pearl LH. A read-ahead function in archaeal family B DNA polymerases detects pro-mutagenic template-strand uracil. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:9045–9050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Firbank SJ, Wardle J, Heslop P, Lewis RJ, Connolly BA. Uracil recognition in archaeal DNA polymerases captured by X-ray crystallography. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;381:529–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fortune JM, Pavlov YI, Welch CM, Johansson E, Burgers PM, Kunkel TA. Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase delta:high fidelity for base substitutions but lower fidelity for single and multi-base deletions. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:29980–29987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]