Abstract

Lymphoid specific helicase (Lsh) belongs to the family of SNF2/helicases. Disruption of Lsh leads to developmental growth retardation and premature aging in mice. However, the specific effect of Lsh on human cellular senescence remains unknown. Herein, we report that Lsh overexpression delays cell senescence by silencing p16INK4a in human fibroblasts. The patterns of p16INK4a and Lsh expression during cell senescence present the inverse correlation. We also find that Lsh requires histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity to repress p16INK4a and treatment with trichostatin A (TSA) is sufficient to block the repressor effect of Lsh. Moreover, overexpression of Lsh is correlated with deacetylation of histone H3 at the p16 promoter, and TSA treatment in Lsh-expressing cells reverses the acetylation status of histones. Additionally, we demonstrate an interaction between Lsh, histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and HDAC2 in vivo. Furthermore, we demonstrate that Lsh interacts in vivo with the p16 promoter and recruits HDAC1. Our data suggest that Lsh represses endogenous p16INK4a expression by recruiting HDAC to establish a repressive chromatin structure at the p16INK4a promoter, which in turn delays cell senescence.

INTRODUCTION

Senescence is a state during which cells lose the ability to proliferate that is accompanied by specific changes in cellular morphology and gene expression. During the process of cell senescence, senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) is activated, the cell cycle is irreversibly arrested at the G1 phase, senescence-associated hetero-chromatic foci form and expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKI) increases (1,2).

Lymphoid specific helicase (Lsh), also termed as proliferation associated SNF-2-like gene (PASG), was originally found to be expressed only in lymphoid tissue in adult mice (3). This may have been indicative of the proliferating nature of lymphoid cells rather than tissue specificity, as expression is nearly ubiquitous in the developing mouse embryo (4,5). Lsh has been shown to be linked to cell proliferation and premature aging (5,6). Imperfect maintenance of genome integrity has been postulated to be an important cause of senescence and premature aging (7). DNA methylation governs several distinct processes, including genomic stability and gene promoter regulation. Errors in replication of DNA-methylation patterns as observed in mutant Lsh mice (6,8) may destabilize the genome and activate cellular self defense mechanisms that prevent cells from entering S-phase. Altered gene expression, reduced cell proliferation and abnormal embryonic development are also consequences. However, other mechanisms may also contribute to the observed senescence phenotypes in Lsh mutant mice. For example, bmi-1, a transcriptional regulator, may provide an alternative mechanism to DNA methylation in regulating the expression of p16INK4a which plays essential role in establishing a replicative senescence phenotype (9). Therefore, it can be concluded that Lsh may play a critical role in aging through multiple regulatory mechanisms. Herein, we report that Lsh delays cellular senescence by repressing the senescence-associated tumor suppression gene, p16INK4a.

Chromatin remodeling and histone modifications have emerged as primary regulatory mechanisms controlling gene expression. Hyperacetylation of histones H3 or H4 is generally associated with transcriptionally active chromatin (10), while the chromatin of inactive regions is enriched in deacetylated histones H3 and H4. The acetylation status of histones at specific DNA-regulatory sequences depends on the recruitment of histone acetyltransferases or histone deacetylase (HDAC) activities.

Lsh is a member of the SNF2 family of helicases that is involved in chromatin remodeling (3,11). As described previously, histone acetylation is a marker for transcriptional activation. Huang et al. (12) reported that Lsh regulates histone acetylation at repetitive elements. Furthermore, it has been reported that histone H3 acetylation was enhanced in Lsh−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) at the promoters of genes whose expression levels were affected by the absence of Lsh, including HoxA6 and HoxA7 (13). Here, we found that Lsh-mediated p16INK4a repression was not due to CpG methylation at promoter, which is in agreement with a previous report (6), but, is involved in HDAC-mediated histone deacetylation. We report that the endogenous p16 promoter of Lsh-expressing cells is enriched in deacetylated histone H3, and that Lsh-mediated repression is abolished by treatment with trichostatin A (TSA). Lsh interacts directly with the endogenous p16 promoter, as demonstrated by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays, and recruits HDAC1. Moreover, in vivo interactions between Lsh, HDAC1 and HDAC2 have also been reported, suggesting that Lsh may mediate p16 repression by recruiting a corepressor complex containing HDAC1 and HDAC2 to the p16 promoter.

In this study, we examined the role of Lsh in normal cellular senescence by assessing the phenotypes associated with Lsh overexpression and small hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated Lsh silencing. We further identified the underlying mechanisms associated with Lsh-mediated repression of p16.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell line, cell culture and treatments

Human embryonic lung diploid fibroblast 2BS cells (obtained from the National Institute of Biological Products, Beijing, China) were previously isolated from female fetal lung fibroblast tissue and have been fully characterized (14). 2BS cells are considered to be young at PD 30 or below and to be fully senescent at PD 55 or above. Human embryonic lung diploid fibroblast WI-38 cells (ATCC number: CCL75) were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). WI-38 cells are considered to be young at PD 25 or below and to be fully senescent at PD 50 or above. All cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, GIBCO BRL, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2. Eighty percent confluent cultures were detached by PBS solution containing 0.25% trypsin and then split at a ratio of 1:2. TSA (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis MO, USA) was dissolved in ethanol and added to the culture medium at 10 ng/ml for 24 h. 5-aza-CdR (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in acetic acid/water (1:1) and added to the culture medium at 1 µM for 72 h. Fresh medium containing 5-aza-CdR was added every 24 h. A corresponding volume of ethanol or acetic acid/water was added to untreated control cells.

Generation of plasmids, expression vectors and stable cell lines

The pcDNA3.1 vector containing Lsh-HA (pcDNA3.1-Lsh-HA) was a kind gift from Dr David W. Lee (John Hopkins University).

The short hairpin RNA (shRNA) was designed according to the pSuper retro instruction manual (Ambion, USA). The sequence of the sense strand of Lsh-shRNA constructed into pSuper GFP neo was 5′-GTC CTA CTG GTC GAC CAA A-3′; p16-shRNA constructed into pSuper puro was 5′-AGA ACC AGA GAG GCT CTG A-3′ (15); the template oligonucleotides were inserted into the BglII and HindIII sites of the pSuper retro vector.

The expression vector pcDNA3.1-Lsh-HA and its empty vector control were used to transfect young 2BS cells (20 PD) or WI-38 cells (20 PD) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The shRNA specific for Lsh and its negative control were used to infect young 2BS cells using a retroviral system. Pools of stable transformants were obtained by sustained selection with G418 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). PDs were calculated using the formula PD = log(n2/n1)/log2, where n1 is the number of cells seeded and n2 is the number of cells recovered (16).

In experiments presented in Figure 5, young 2BS cells were co-infected by viruses of pSuper-shRNA-Lsh (neomycin) and pSuper-shRNA-p16 (puromycin). Then cells were selected with Puromycin (0.7 μg/ml) and G418 (200 μg/ml), starting 1 day after infection.

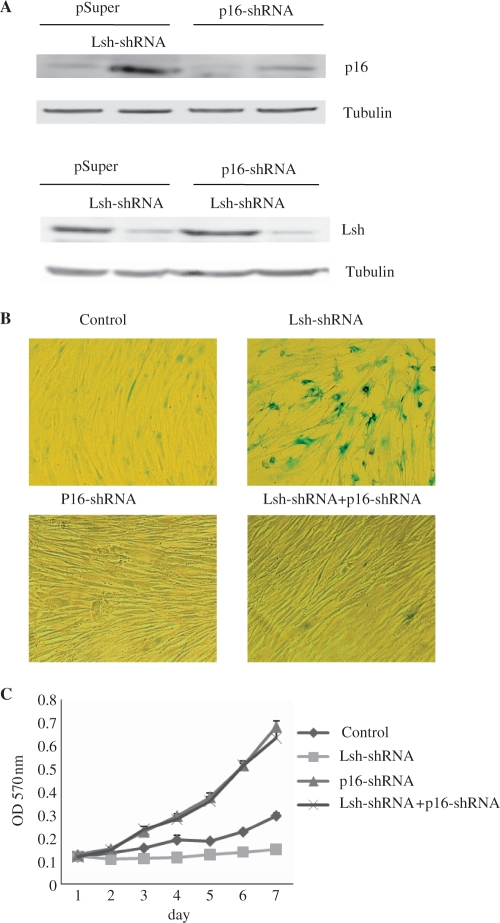

Figure 5.

The silencing of p16INK4a rescues Lsh-shRNA-mediated premature senescence in 2BS cells. (A) Immunoblot analysis of the p16 or Lsh protein levels in 2BS cells exposed to the indicated perturbations. The Tubulin lane serves as a loading control. (B) Senescent β-gal staining in 2BS cells exposed to the indicated perturbations. (C) Cell growth assay performed in 2BS cells by MTT method.

SA-β-gal and SAHF analysis

For SA-β-gal staining, cells were washed twice in PBS, fixed for 3–5 min at room temperature in 3% formaldehyde and washed again with PBS. Then cells were incubated overnight at 37°C without CO2 in a freshly prepared SA-β-gal-staining solution as described (17).

To determine SAHF formation, cells were cultured directly on glass cover slips and were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde. After washing with PBS, cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. DNA was visualized by DAPI (1 μg/ml) staining for 1 min, followed by two PBS washes. Cover slips were mounted in a 90% glycerol PBS solution. Cover slips were examined using a Leica confocal TCS SP2 microscope.

Cell-cycle analysis

When cells reached 70–80% confluence, they were washed with PBS, detached with 0.25% trypsin and fixed with 75% ethanol overnight. After treatment with 1 mg/ml RNase A (Sigma) at 37°C for 30 min, cells were resuspended in 0.5 ml of PBS and stained with propidium iodide in the dark for 30 min; DNA contents were measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorting on a FACScan flow cytometry system (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed using CellFiT software. Each experiment was performed at least three times, and representative data were shown.

Growth curves

Cell proliferation was assayed using the MTT method (18). Cells were plated at a density 2 × 103 cells per well into 96-well plate and cultured for periods ranging from 1 to 7 days. The medium was replaced at 24-h intervals. At the indicated times, cells were stained with 20 μl MTT (10 mg/ml in PBS; Sigma) for 4 h and then dissolved with DMSO. The optical density at 570 nm was determined. Each curve was performed twice. Each point value was the mean ± SD of triplicate points from a representative experiment (n = 3).

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were lysed in modified Radioimmune Precipitation Assay (RIPA) Buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25% Na–deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 0.2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM NaF) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) as described before. The protein concentration of each sample was determined using a BCA Protein Assay Reagent (Pierce); 100–150 μg of total protein was subjected to 9–15% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore). Immunodetection was performed by incubating with primary antibodies [anti-Lsh (sc-28202) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), p16INK4a (Lab Vision & NeoMarkers, CA, USA), phospho-Rb (Ser795) (Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Danvers, MA, USA) and overnight at 4°C, followed by rinses and addition of HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Zhongshan, China). Incubation with anti-β-actin (sc-1616) (Santa Cruz) or anti-tubulin (ab7291) (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) served as a loading control. Proteins were visualized using SuperSignal WestPico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce) according to manufacturer's instructions.

ChIP

Assays were performed using a ChIP assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) according to the manufacturer's instructions with minor modifications. In brief, normal or stably transfected 2BS cells at a density of 80–90% confluency were used in ChIP assays with anti-Lsh, anti-HDAC1 (sc-8410x) (Santa Cruz), anti-HDAC2 (sc-6296x) (Santa Cruz) and anti-acetylated Histone H3(Upstate) antibodies. DNA isolated from the immunoprecipitates were quantified by traditional PCR or real-time PCR using a primer pair complementary to the p16 promoter, including a forward primer (F: 5′-GAA AGA TAC CGC GGT CCC TC-3′) and a reverse primer (R: 5′-ACC GTA ACT ATT CGG TGC GTT GG-3′), which amplify the region between nucleotides −177 and +135 within the p16 promoter region (19) that correlates with loss of gene expression. As an internal control, a region upstream of the p16 promoter was amplified using a forward primer (control-F: 5′-CCC TTC CCC CCT TAT AAT TAC G-3′) and a reverse primer (control-R: 5′-GGA CGG ACT CCA TTC TCA AAG-3′) (20). Input DNA as well as DNA immunoprecipitated by anti-actin or IgG served as positive or negative control, respectively. Re-ChIP was performed as described previously (21).

Real-time PCR and data analysis

Two-step real-time PCR was performed with 5 μl of DNA and 400 nM primers diluted to a final volume of 50 μl in SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Accumulation of fluorescent products was monitored by real-time PCR using an Applied Biosystem 7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). A melting curve was generated to ensure that a single peak of the predicted Tm was produced and no primer-dimer complexes were present. Single amplicon generation was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. No PCR products were observed in the absence of template. Sequence Detector software (version 1.3.1) was used for data analysis and relative fold induction was determined by the comparative threshold cycle (CT). Fold enrichments were determined by the method described in the Applied Biosystems User Bulletin and data analysis followed the methodology described in a recent report (22). Fold differences were calculated by correcting for each signal concentration with the concentration of input signal for each sample [(signal concentration)/(input concentration)]. Real-time PCR data figures were generated using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, USA).

For real-time RT–PCR in Figures 3D and Figure 6B, the primers specific for p16 gene were used as described previously (Primer R, 23). The relative abundance of p16 mRNA levels was calculated after normalization using GAPDH mRNA levels as the internal control.

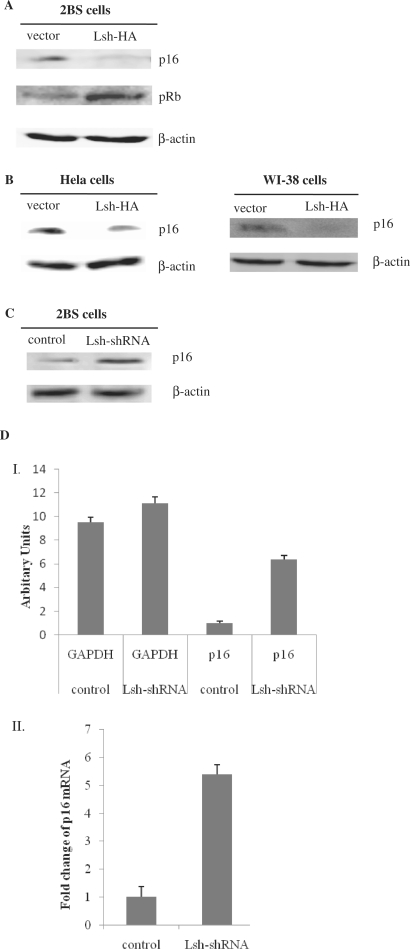

Figure 3.

Lsh represses endogenous p16 levels. (A) Immunoblot analysis of expression levels of p16 and phosphorylation levels of Rb in 2BS cells exposed to empty vector or Lsh-HA. (B) Immunoblot analysis of p16 expression levels in Hela cells or WI-38 cells, exposed to empty vector or Lsh-HA. (C) Immunoblot analysis of p16 levels in 2BS cells exposed to control-shRNA or Lsh-shRNA. (D) Quantitative RT–PCR measuring p16 mRNA levels in 2BS exposed to control-shRNA or Lsh-shRNA. Non-normalized GAPDH and p16 mRNA levels are presented in graph I. (Graph II) After normalization against GAPDH mRNA, the relative p16 mRNA abundance was calculated. The data presented are average values obtained from triplicate points from a representative experiment (n = 3), which was repeated three times with similar results.

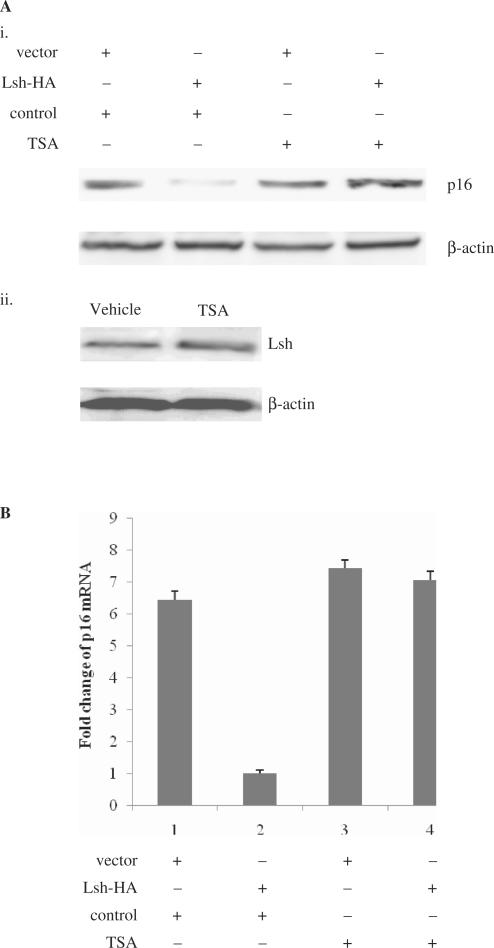

Figure 6.

Lsh-mediated p16 repression requires HDAC activity. (A) (i) Immunoblot analysis of the p16 protein levels in vector- and Lsh-HA-transfected 2BS cells with or without TSA treatment. (ii) Immunoblot analysis of the Lsh protein levels in normal 2BS cells opposed to TSA. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR measuring p16 mRNA levels in vector- and Lsh-HA-transfected 2BS cells with or without TSA treatment. (C) ChIP analysis of histone H3 acetylation status at the endogenous p16 promoter in vector- and Lsh-HA-transfected 2BS cells with or without TSA treatment. ChIP assays were quantified by real-time PCR (D). (E) ChIP analysis of the histone H3 acetylation status at the endogenous p16 promoter in control shRNA- and Lsh-shRNA-infected 2BS cells. ChIP assays were quantified by real-time PCR (F).

Coimmunoprecipitation assays

For coimmunoprecipitation experiments, normal 2BS cells or Lsh-HA-overexpressing 2BS cells were collected from a 10-cm-diameter plate using RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Lysates were precleared by incubation with 100 μl of protein G-Sepharose (50% slurry) for 1 h. The cleared lysate was then subjected to immunoprecipitation with the indicated antibodies overnight at 4°C. Protein G-Sepharose beads (Sigma) were added and the incubation was continued for 2 h at 4°C. Precipitates were washed four times with RIPA buffer (1 ml), followed by resuspension in 2 × SDS loading buffer. Proteins were separated using gradient SDS–PAGE gels (7.5–10%), followed by electrophoretic transfer to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore). Endogenous Lsh protein was immunoprecipitated or immunoblotted using rabbit anti-Lsh antibodies. Blots were also probed with anti-HA, anti-HDAC1 and anti-HDAC2 antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. All coimmunoprecipitation experiments included normal immunoglobulin (Ig) as a negative control.

GST pull-down assays

For pull-down experiments, Escherichia coli strain DH5α was used to produce GST or GST fusion protein. In vitro transcripted/translated HDAC1 using TNT® T7 Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation System was used as a source of purified HDAC1 protein. GST pull-downs were performed as described previously (24). In brief, ∼5 μg of GST or GST-Lsh bacterial recombinant protein immobilized on glutathione–Sepharose 4B resin was pre-blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin and then incubated with the purified HDAC1 protein for 4 h on a rotator at 4°C. After an extensive wash with lysis buffer, the bound proteins were fractionated by SDS–PAGE and subjected to western blot analysis with anti-HDAC1 antibody.

Methylation-specific PCR (MSP)

DNA was extracted and treated with bisulfite, as described previously with minor modifications (25). Briefly, genomic DNA (1 μg) in a volume of 50 μl was denatured by NaOH (final concentration, 0.275 M) for 10 min at 42°C. The denatured DNA was then treated with 10 μl of 10 mM hydroquinone and 520 μl of 3 M sodium bisulfite at 50°C overnight, followed by purification using a QiaQuick DNA purification kit (QIAGEN). Primer sequences and PCR conditions were described previously for the p16 gene [Primer L&N, (23)]. Primers were localized to regions in and around the transcription start site of the p16 gene, a region that correlates with loss of gene expression. The genomic DNA treated with in vitro methylation was used as positive control. The in vitro methylation was carried out as previously described (26). SssI methylase and S-adenosylmethionine were purchased from New England Biolabs.

RESULTS

Lsh overexpression delays cell senescence, whereas shRNA-mediated Lsh silencing leads to a cell-cycle arrest, SAHF and premature senescence in human fibroblasts

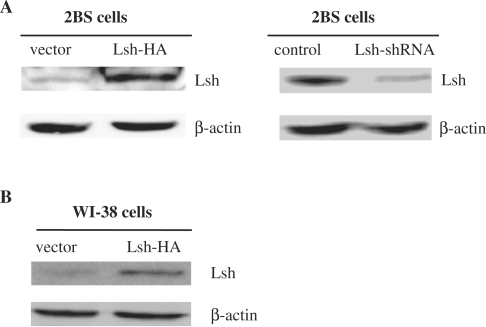

The senescent state of normal human diploid fibroblast cells is characterized by irreversible growth arrest and morphologically enlarged, flattened cells with prominent lipofuscin granules and irreversible growth arrest (27). To determine the effects of Lsh expression levels on cellular senescence, we overexpressed Lsh by Lsh–HA or silenced Lsh by Lsh-shRNA in young 2BS cells. To determine whether the effect of Lsh-shRNA on senescence truly depend on the depletion of Lsh, we performed rescue experiment by introducing exogenous Lsh in Lsh–shRNA-expressing 2BS cells (Supplementary Figure 3S). After sustained selection with G418, the transformants were obtained. The transfection efficiencies of Lsh-HA or Lsh–shRNA were confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Figure 1). The senescence markers for Lsh-shRNA-expressing cells or Lsh-HA-overexpressing cells were monitored at the same time points as their corresponding negative control cells (Figure 2). To determine whether the effects associated with altered Lsh expression levels are a general accompaniment to senescence, we extended our study to investigate additional normal human diploid fibroblast WI-38 cells.

Figure 1.

Immunoblot analyses of Lsh expression levels in Lsh-HA-transfected or Lsh-shRNA-infected cells. (A) Immunoblot analysis of Lsh protein levels in 2BS cells exposed to Lsh-HA or Lsh-shRNA as well as the corresponding control. The vector- or Lsh-HA-transfected cells were analyzed at 55 PD using 100 μg of total protein. The control- or Lsh-shRNA-infected cells were analyzed at 42 PD using 120 μg of total protein. (B) Immunoblot analysis of Lsh protein levels in WI-38 cells exposed to vector or Lsh-HA. The vector- or Lsh-HA-transfected cells were analyzed at 37 PD using 100 μg of total protein.

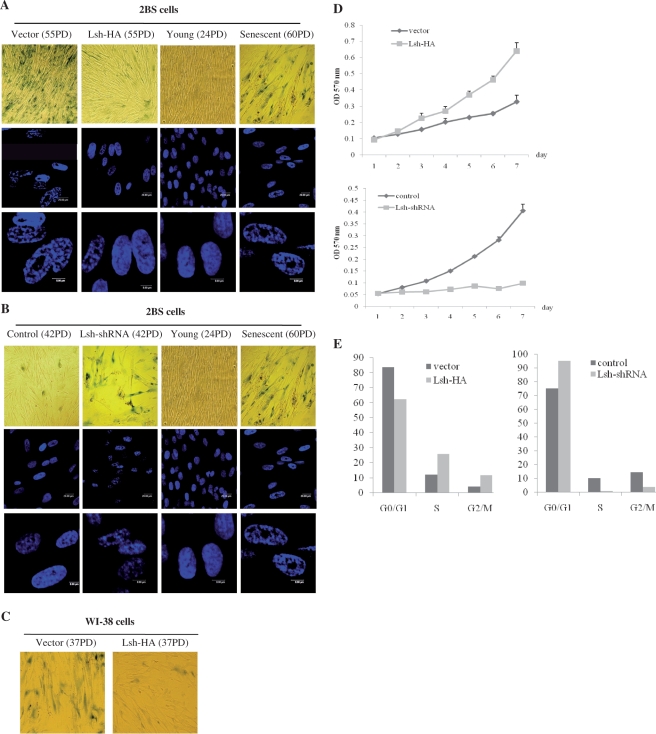

Figure 2.

Lsh overexpression suppresses senescence-associated features in 2BS and WI-38 cells. The stable transformants were passaged until one of them underwent senescence and analyzed for the relative senescence markers (vector- or Lsh-HA-transfected 2BS cells at PD 55, vector- or Lsh-HA-transfected WI-38 cells at PD 37, control-shRNA- or Lsh-shRNA-infected 2BS cells at PD 42). (A) Vector-transfected and Lsh-HA-transfected 2BS cells were stained for SA-β-gal activity (upper panel) or SAHF formation (middle and lower panels, 20 μm or 8 μm bars respectively). (B) Control-shRNA-infected and Lsh-shRNA-infected 2BS cells were stained for SA-β-gal activity (upper panel) or SAHF formation (middle and lower panels, 20 μm or 8 μm bars respectively). Young (24 PD) and senescent (60 PD) 2BS cells were stained as normal controls. (C) Vector-transfected and Lsh-HA-transfected WI-38 cells were stained for SA-β-gal activity. (D) Cell growth assay performed in 2BS cells by MTT method. (E) Cell-cycle profile analysis by flow cytometry.

Lsh delays a senescence-like cell morphology and inhibits SA-β-Gal activity

We monitored cell morphological changes in cells with altered Lsh expression. The Lsh-shRNA-infected 2BS cells (PD 42) showed increasing gross enlargement, flattening and the accumulation of granular cytoplasmic inclusions. However, no significant morphological changes were observed in Lsh-HA-transfected cells (PD 55), which retained a refractive cytoplasm with thin, long projections similar to young control cells (Figure 2A and B).

The specific senescence-associated marker, pH 6.0 optimum β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal), was assayed by X-gal staining. Whereas nearly all of the Lsh–shRNA-infected cells (PD 42) showed strong levels of blue SA-β-gal staining similar to senescent cells, the control cells showed a lower frequency of SA-β-gal staining (Figure 2B). However, only sporadic SA-β-gal-positive cells were seen in Lsh-HA-transfected cells (PD 55), although the corresponding vector control cells (PD 55) showed strong SA-β-gal staining (Figure 2A). We obtained similar results using WI-38 cells (Figure 2C).

Lsh blocks the formation of senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF)

The accumulation of senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF) is another specific biomarker of senescent cells (28). As shown in Figure 2A and B, senescence induced by extensive passage culture typically displayed punctuated DNA foci which were visualized by DAPI staining. In contrast, exponentially growing human fibroblasts usually displayed several small nucleoli and a more uniform DAPI-staining pattern. We observed that 2BS cells expressing Lsh–HA (PD 55) did not develop pronounced nucleoli or DNA foci when vector-transfected cells (PD 55) appeared prominent DNA foci (Figure 2A). When Lsh-shRNA-infected cells (PD 42) appeared prominent DNA foci which are nearly indistinguishable from those in senescent 2BS cells, the control-shRNA cells (PD 42) displayed a more uniform DAPI-staining pattern (Figure 2B). Taken together, these results were consistent with our previous studies showing senescent SA-β-gal staining.

Lsh overexpression promotes cell growth, whereas shRNA-mediated silencing of Lsh expression leads to growth inhibition

The proliferative capacity of cells declines significantly as they enter senescence. To determine the effect of Lsh expression levels on proliferative changes, the growth rates of various transformants were measured using MTT assays. The results revealed that growth of Lsh-HA-transfected cells advanced quickly, suggesting a strong proliferative potential relative to the control cells (Figure 2D). However, when Lsh expression was inhibited by shRNA targeting, 2BS cells showed severe growth retardation (Figure 2D).

Lsh overexpression alleviates G1 cell-cycle arrest

To define further the mechanisms underlying growth rate promotion by Lsh, the cell-cycle profiles of various transformants were analyzed by flow cytometry. Whereas vector-transfected cells entered the irreversible G1 arrest, Lsh-HA-transfected cells exhibited a significantly postponed irreversible growth arrest (Figure 2E). In contrast to the severe G1 cell-cycle arrest imposed by Lsh-shRNA, the control-shRNA cells showed a decrease in the proportion of 2BS cells in the G0/G1 phases (Figure 2E). Therefore, Lsh may promote cell proliferation by stimulating cell-cycle progression.

Lsh overexpression results in a finite extension of fibroblast replicative lifespan

The replicative senescence of normal human diploid fibroblasts is directly correlated to their PD number, rather than to their growth and metabolic time (1,29). After completing a finite number of divisions, cells enter a permanent growth arrest. To determine the effect of Lsh expression levels on the lifespan of 2BS cells, the number of PDs for Lsh-HA-transfected cells, Lsh-shRNA-infected cells and the corresponding control cells from the same set of early passage cells were counted. The lifespan of Lsh-HA cells (PD 65–70) was about 10–12 PDs greater than the vector control 2BS cells (PD 55–58) (Table 1). In contrast, Lsh-shRNA cells (PD 42–45) ceased cell division at 13 PDs earlier than the control-shRNA cells (PD 55–58), remaining in the sub-confluent stage even after two months under normal culture conditions (Table 2).

Table 1.

Cumulative population doublings of vector- or Lsh-HA-transfected 2BS cells

| Cells | No. of examples | Cumulative population doublings |

|---|---|---|

| Vector | 6 | 55–58 |

| Lsh-HA | 8 | 65–70 |

| Untransfected cells | 5 | 55–60 |

Table 2.

Cumulative population doublings of control-shRNA- or Lsh-shRNA-infected 2BS cells

| Cells | No. of examples | Cumulative population doublings |

|---|---|---|

| Control-shRNA | 6 | 55–58 |

| Lsh-shRNA | 6 | 42–45 |

| Untransfected cells | 5 | 55–60 |

Lsh represses endogenous p16INK4a expression

Senescence is the final phenotypic state in response to various physiologic types of stress resulting in decreased cell proliferation and often mediated by increased expression and activation of tumor suppressor genes such as p16INK4a, p53 and p21 (30,31). Prominent among these is p16INK4a (30). Previous reported that PASG mutant mice demonstrate a markedly increased expression of p16INK4a. Therefore, we hypothesized that p16 is a Lsh target gene. First, we determined whether Lsh overexpression could downregulate p16 protein expression. As shown in Figure 3A, the expression of p16INK4a was significantly repressed in Lsh-HA-transfected 2BS cells comparing to vector-transfected cells. As a direct target of p16, Rb phosphorylation increased. Furthermore, we also observed Lsh-mediated repression of p16 in HeLa cells and in WI-38 cells (Figure 3B).

To further explore the role of Lsh-mediated p16 repression, we silenced the Lsh gene using shRNA and examined p16 expression levels in 2BS cells. Immunoblot analysis revealed a marked increase in p16INK4a protein levels in Lsh-shRNA cells comparing to control-shRNA cells (Figure 3C). Moreover, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Lsh-shRNA-infected cells showed a significant increase in p16 mRNA levels in 2BS cells (Figure 3D), suggesting that Lsh may normally regulate p16 transcription. Collectively, these results suggest that p16INK4a may play a key-regulatory role in Lsh-mediated cell senescence.

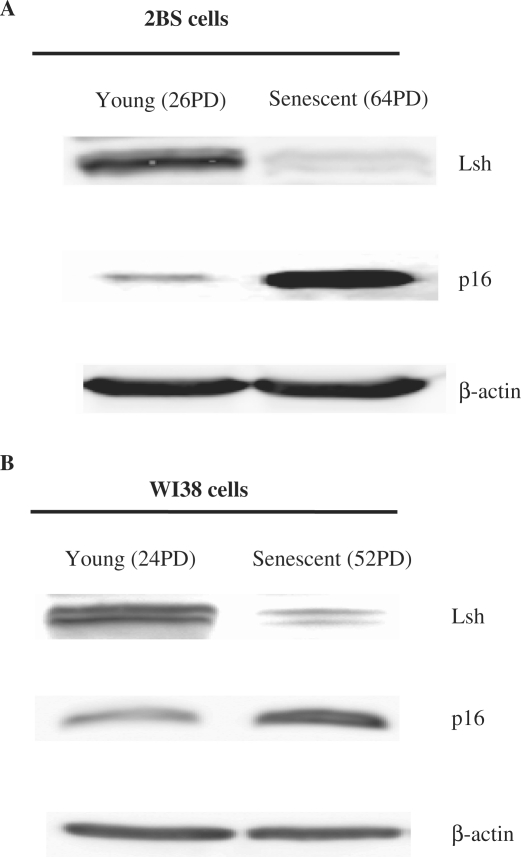

Lsh expression inversely correlates with p16INK4a expression in young and senescent cells

Due to the effect of Lsh on cell senescence and the role of Lsh in the modulation of p16INK4a expression, we further evaluated the expression patterns of Lsh and p16INK4a in young and senescent 2BS or WI-38 cells. Immunoblot analyses revealed that the levels of Lsh were significantly decreased in senescent cells compared to young cells (Figure 4A and B, upper panels). As expected, young cells possessed low p16INK4a levels. However, there was an increase in the p16INK4a level in senescent cells (Figure 4A and B, middle panels). These data indicated that young cells expressed high level of Lsh, however, Lsh expression declined accompanied by improving level of p16INK4a and the onset of cellular senescence. In these cells, Lsh expression reduced when cells entered senescence and inversely correlated with p16INK4a, which gave the opportunity for Lsh to adjust p16INK4a expression through the change of itself.

Figure 4.

The expression patterns of Lsh and p16INK4a in young and senescent cells. Immunoblot analysis of Lsh and p16INK4a expression in young and senescent 2BS cells (A) or WI-38 cells (B). Total proteins were extracted, and immunoblotting was performed using specific antibodies against Lsh and p16INK4a as indicated. The β-actin lane serves as a loading control.

Silencing of p16 rescues Lsh shRNA-induced premature senescence in 2BS cells

In order to further verify that Lsh could regulate senescence via p16INK4a, we evaluated the role of p16 in mediating the senescence effects of Lsh-shRNA in 2BS cells. Young 2BS cells infected with both Lsh-shRNA and p16-shRNA or with Lsh-shRNA or p16-shRNA alone were monitored. The results showed that cells treated with Lsh-shRNA alone revealed strong SA-β-gal staining, severe growth retardation and significant p16 increasing, whereas cells doubly treated with Lsh-shRNA and p16-shRNA completely reversed the senescence phenotypes. As expected, p16-shRNA-infected cells displayed young phenotypes (Figure 5). Importantly, the p16 shRNA reagent did not overtly compromise the ability of Lsh-shRNA to suppress Lsh expression in the cells doubly infected with viruses encoding shRNAs for p16 and Lsh (Figure 5A, lower panel).

Lsh-mediated p16 repression requires HDAC activity, but does not DNMT activity

It has been suggested that histone deacetylation and DNA methylation could participate in gene repression mediated by some members of SNF family (32–34). Thus, we decided to investigate whether Lsh-mediated p16 repression requires HDAC or DNMT activity.

First, we tested the ability of TSA, a specific inhibitor of HDAC activity, to overcome the Lsh-mediated repression of p16. Immunoblot analysis of p16 protein levels indicated that the repression of p16 expression by Lsh was reversed to near completion by the addition of low levels (10 ng/ml) TSA in 2BS cells (Figure 6Ai). However, TSA did not alter the endogenous Lsh expression levels (Figure 6Aii). We further quantified the p16 mRNA levels using quantitative RT–PCR, and verified the ability of TSA to overcome the Lsh-mediated p16 repression (Figure 6B). These results suggest that repression of p16 Lsh-mediated may depend on HDAC activity.

To verify this notion, we further determined whether Lsh expression correlated with histone deacetylation at the p16 promoter. To address this point, we first analyzed the acetylation status of histone H3 at the p16 promoter in Lsh-HA-transfected cells or in vector-transfected cells. ChIP analysis revealed that Lsh overexpression was associated with a significant decrease in the levels of acetylated histone H3 at the p16 promoter (Figure 6C). If TSA treatment directly affects p16 gene expression levels, one would expect to observe the effect of TSA on the histone acetylation status at the p16 promoter. The results showed that TSA treatment led to a strong increase in histone acetylation levels at the p16 promoter whether in Lsh-HA-transfected cells or in vector-transfected cells, which could completely reverse the p16 promoter deacetylation induced by Lsh-HA overexpressing (Figure 6C). Quantitative real-time PCR analyses were performed to verify the ChIP measurements (Figure 6D).

To further confirm that Lsh expression correlates with the deacetylation status of the p16 promoter, we performed ChIP assays in Lsh-shRNA- or control-shRNA-infected 2BS cells. Consistent with our previous point, the results showed that knockdown of Lsh resulted in a strong increase in the levels of histone H3 acetylation at the p16 promoter (Figure 6E). Quantitative real-time PCR analyses further verified the increasing (Figure 6F).

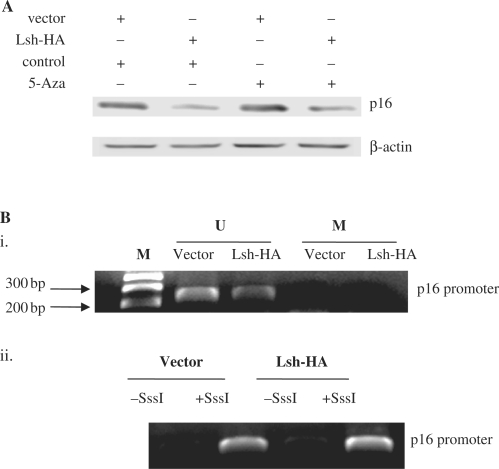

Next, we analyzed the effect of 5′-aza-CdR, which specifically inhibits DNMTs, in the Lsh-mediated repression of p16. Immunoblot analyses showed that the addition of 5′-aza-CdR didn’t alter the repression status of p16 by Lsh (Figure 7A); suggesting that Lsh-mediated repression of p16 doesn’t depend on DNMT activity.

Figure 7.

Lsh-mediated p16 repression doesn’t require DNMT activity. (A) Immunoblot analysis of the p16 protein levels in vector- and Lsh-HA-transfected 2BS cells following 5′-aza-CdR treatment. (B) (i) MSP analysis of the CpG methylation status at the p16 promoter in vector-transfected and Lsh-HA-transfected 2BS cells. (ii) The genomic DNA extracted from vector- or Lsh-HA-transfected cells was treated with SssI methylase and used as positive control. M, marker; U, non-methylated-specific PCR products; M, methylation-specific PCR products.

To further confirm this notion, we examined whether Lsh expression correlates with CpG methylation at the p16 promoter. We then monitored the CpG-methylation status of the p16 promoter in Lsh-HA-transfected cells or in vector-transfected cells using methylation-specific PCR method. The results showed no detectable p16 methylation whether in Lsh-HA-transfected cells or in vector-transfected cells (Figure 7B), which further verify that Lsh-mediated repression of p16 doesn’t depend on DNMT activity.

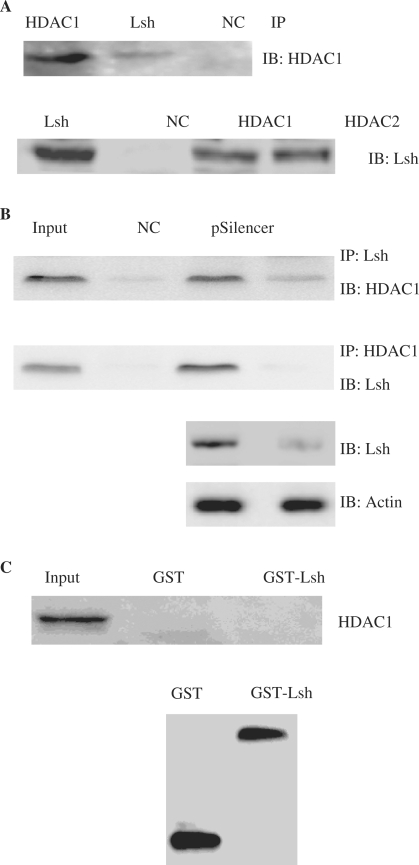

Lsh associates with HDAC1 and HDAC2 in vivo

To gain further insights into the mode of Lsh-mediated repression, we analyzed the association between specific HDACs and Lsh. In the present study, we determined the interaction between endogenous Lsh and the class I family of HDACs, HDAC1 and HDAC2 in normal 2BS cells. As shown in Figure 8A upper panel, the immunoprecipitate of Lsh associates with endogenous HDAC1, as detected by immunoblot. The reverse coimmunoprecipitation experiments were also preformed to confirm this association. We immunoprecipitated HDAC1 and HDAC2 from cell extracts, and used an anti-Lsh antibody to detect bound Lsh, thereby providing evidence for an in vivo association between Lsh and HDAC1/HDAC2 (Figure 8A, lower panel).

Figure 8.

Lsh associates with HDAC1 and HDAC2. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation of Lsh with HDAC1 and HDAC2 in 2BS cells. Cell lysates from normal 2BS cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-Lsh, anti-HDAC1 or anti-HDAC2 antibodies. The immunoprecipitated complexes were separated by SDS–PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis using the indicated antibodies. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation analysis of Lsh with HDAC1 in Lsh-deficient Hela cells. Hela cells were transiently transfected with pSilencer vector or with pSilencer-siLsh. Cells were harvested at 48 h post-transfection. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Lsh or anti-HDAC1 antibodies as indicate, and analyzed by western blotting with anti-HDAC1 or anti-Lsh antibodies. (C) In vitro GST-binding assay for interaction between GST-Lsh and HDAC1. GST alone or GST-fusion protein GST-Lsh immobilized on glutathione–Sepharose 4B resin were incubated with purified HDAC1 protein generated by in vitro transcription/translation system. The bound fractions from the glutathione–Sepharose beads and the input cell extract were analyzed by western blotting with anti-HDAC1 antibodies (upper panel). Analysis of the GST alone or GST fusion proteins used is shown in the lower panel.

To further confirm this interaction in vivo, we then monitored the association of Lsh and HDAC1 in siLsh-transfected Hela cells relative to mock-transfected cells. The results showed that Lsh immunoprecipitates from Lsh-deficient cells contained significantly decreased HDAC1 levels relative the mock-transfected cells; the reverse immunoprecipitation displayed the similar result (Figure 8B).

In addition, GST pull-down experiments with bacteria-expressed GST-Lsh and in vitro transcripted/translated HDAC1 were then performed to examine the nature of the interaction between Lsh and HDAC1. These experiments revealed that Lsh could interact with HDAC1 indirectly (Figure 8C).

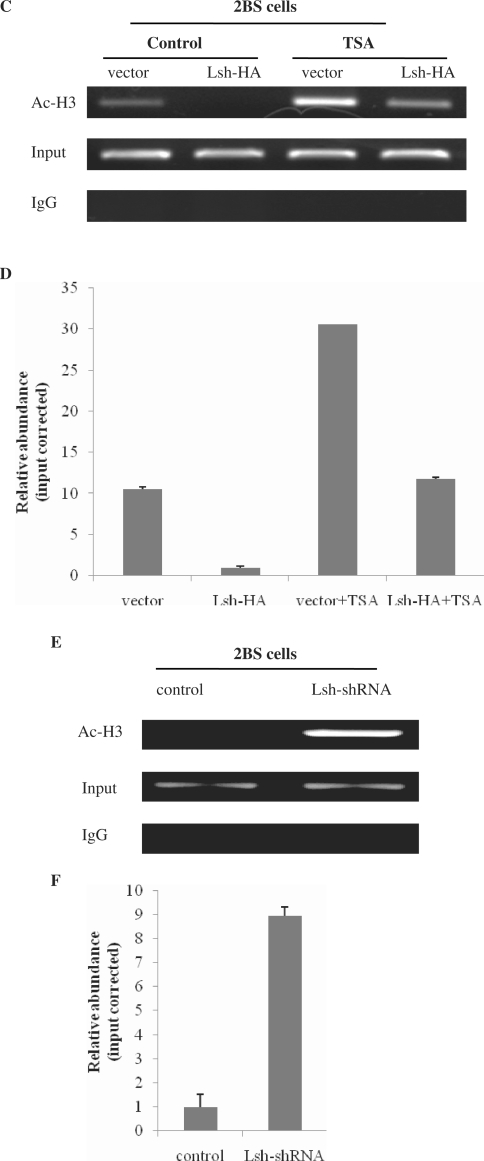

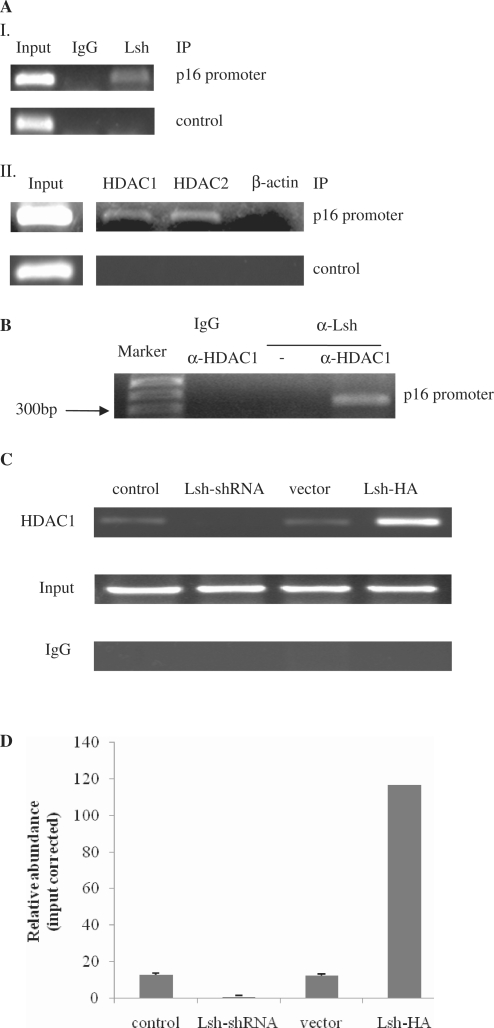

Lsh, HDAC1 and HDAC2 interact with the p16 promoter

To determine whether Lsh and its associated proteins exert functions by direct recruitment to p16 promoter, we performed a series of ChIP assays in 2BS cells. The results showed that anti-Lsh, anti-HDAC1 and anti-HDAC2 antibodies all immunoprecipitated the p16 promoter region (Figure 9A). Very little amplification was observed when control primers were used to amplify the immunoprecipitated DNA (Figure 9A, bottom panels).

Figure 9.

Lsh interacts with the endogenous p16 promoter and recruits HDAC1 in 2BS cells. (A) ChIP analysis of the p16 promoter using the indicated antibodies. (B) Re-ChIP analysis showing the colocalization of Lsh with HDAC1 at the p16 promoter. (C) HDAC1 recruitment analysis at the endogenous p16 promoter in Lsh-expressing cells or Lsh-deficient 2BS cells. Quantitative real-time PCR verified the recruitment (D).

To further ensure the colocalization of Lsh with HDAC1, Re-ChIP was performed using an anti-Lsh antibody, followed by reimmunoprecipitation using an anti-HDAC1 antibody, and the detection of PCR-amplified signal in the p16 promoter region. The results showed that both Lsh and HDAC1 associate with the regulatory region of the p16 promoter (Figure 9B).

We next investigated whether Lsh mediates the recruitment of HDAC1 to the p16 promoter. ChIP analyses revealed that anti-HDAC1 antibodies immunoprecipitated higher amounts of the p16 promoter region in Lsh-HA-overexpressing cells relative to the vector control cells. Conversely, when Lsh expression was inhibited using shRNA, the recruitment of HDAC1 to the p16 promoter was significantly impaired (Figure 9C). Quantitative real-time PCR verified the recruitment (Figure 9D).

DISCUSSION

Aging can be defined as progressive functional decline and increasing mortality over time. Previous studies have demonstrated that targeted deletion of Lsh in mice leads to developmental growth retardation and premature aging phenotypes (6). Moreover, PASG mutant mice display a significant increase in the expression of senescence-related genes, including p16INK4a, p19ARF, p53 and p21 (6). However, the function of Lsh in human cellular senescence has never been described. In the present study, we showed that Lsh delayed cellular senescence in human fibroblasts (Figure 2), an effect attributed to the repression of p16INK4a (Figure 3), which is an important cell-cycle inhibitor, and its accumulation triggers the onset of cellular senescence (35). However, a recent publication draws some different conclusions (36). We think the different findings were due to the different cell lines. TIG-7 cell is a human fetal diploid cell strain; while 2BS cell is a human embryo diploid cell strain, which stay at earlier developmental stage. It may be the key cause of the different findings between two cell lines upon to PASG knockdown. Secondly the original gender is different. The former comes from male and the latter comes from female.

2BS cells were previously isolated from human fetal lung fibroblast tissue and have been fully characterized (14). The maximum population doubling of human diploid fibroblasts is limited in culture, so they are widely used as a model of cellular senescence. Previous reports have suggested that fibroblast cellular senescence occurs as a consequence of a ‘genetic program’ (37). This program has been partially characterized by gene expression patterns during the progression of successive passages, such as, the upregulation of senescence-associated tumor suppressor, p16INK4a. Here, we found that overexpression of Lsh markedly inhibited p16INK4a expression (Figure 3A and B). Moreover, the shRNA-mediated silencing of Lsh led to an upregulation of p16INK4a levels (Figure 3C and 3D). Therefore, we concluded that Lsh could repress the endogenous p16INK4a. In addition, we detected the endogenous expression patterns of Lsh and p16INK4a in young and senescent 2BS cells or WI-38 cells (Figure 4A and B), establishing a relationship between p16INK4a and Lsh expression and a correlation between Lsh expression and the age of cells. Lsh expression levels significantly declined in senescent fibroblasts, which inversely correlated with p16INK4a expression, thereby allowing changes in Lsh expression to regulate p16INK4a expression.

Since Lsh repressed endogenous p16 expression and delayed cellular senescence in 2BS cells, we next asked whether p16 is required for Lsh-regulated senescence. Experiments in Figure 5 showed that p16 deletion could completely rescue the senescent effect and the upregulation of p16 by Lsh-shRNA, suggesting that the p16/Rb pathway is required for Lsh-shRNA-induced premature senescence.

Lsh, a member of the SNF2 family of chromatin remodeling proteins, is an epigenetic regulator in mice (3,11,12,38). SNF2-like proteins are classified into three subfamilies according to the similarity of their ATPase catalytic domain to either yeast SWI2/SNF2, mammalian Mi-2/CHD or Drosophila ISWI (39). Chromatin remodeling can be targeted to promoters or other specific regions of the genome (40,41). More recent genome-wide studies have revealed that several SNF2 family members can function both as positive and negative regulators of gene expression, possibly by altering chromatin modification (41,42). For example, Fan et al. (2005) found that Lsh specifically controls silencing of the imprinted Cdkn1c gene by a direct association with the 5′ DMR and alteration of the CpG methylation at the Cdkn1c promoter (34). However, the induction of p16INK4a by Lsh mutant was not related to promoter demethylation (6). Consistent with this finding, we found that Lsh overexpression did not alter the CpG methylation of the p16 promoter (Figure 7B) and Lsh-mediated repression of p16 was independent of DNMT activity (Figure 7A).

Covalent modification of the N-terminal tails of chromatin core histone proteins, including acetylation, phosphorylation and methylation, often correlates with transcriptional events, which is to be essential for proper gene expression. Acetylation of histones H3 and H4 relieves structural chromatin compaction, possibly through disruption of interactions between adjacent nucleosomes or by loosening contacts between histones and DNA. It has been reported respectively that INI1/hSNF5, another SWI/SNF family member, represses cyclin D1 and c-fos transcription by inducing Histone H4 deacetylation of the promoter (32,33). Moreover, several previous studies have reported that HDAC inhibitor can induce p16 expression (43–45). In the search for the molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of p16 by Lsh, overexpression of Lsh was found to induce the deacetylation of histone H3 on the p16 promoter in vivo, which can be reversed by treatment with the specific HDACs inhibitor, TSA (Figure 6C and D). Consistent with the findings, both immunoblot and quantitative RT-PCR analysis revealed that Lsh-mediated repression of endogenous p16INK4a could be reversed by low concentrations of TSA (Figure 6A and B). Therefore, for the first time, we reported that histone deacetylation by HDACs may participate in the regulation of p16 by Lsh.

HDACs are frequently recruited to specific DNA sites through association with corepressor molecules. Moreover, the silencing of tumor suppressor genes through the aberrant targeting of HDACs to their gene promoters may be more common than previously realized. Therefore, we hypothesized that Lsh could recruit HDACs to the p16 promoter, resulting in the propagation of a repressive chromatin state. Coimmunoprecipitation assays verified the association of Lsh with HDAC1 and HDAC2 in vivo (Figure 8A and B). However, GST-Pull down assays demonstrated that the interaction between Lsh and HDAC1 could be indirect (Figure 8C).

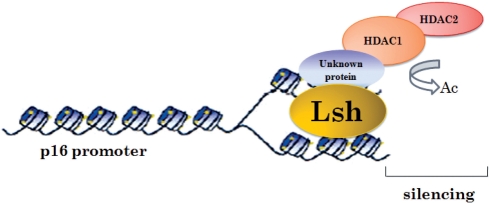

How does Lsh as well as the associated proteins exert the ability to silence p16INK4a? We first hypothesized that Lsh could be targeted to the p16 promoter. ChIP assays indicated that Lsh, HDAC1 and HDAC2 bound the proximal region of the p16 promoter in vivo (Figure 9A). We further performed Re-ChIP assays to verify the colocalization of Lsh with HDAC1 at the p16 promoter (Figure 9B). Quantitative analysis of HDAC1 binding to the p16 promoter showed that Lsh overexpression increased the amounts of HDAC1 binding at the p16 promoter, whereas Lsh knockdown blocked this binding (Figure 9C and D), suggesting that Lsh may recruit HDAC1 to the p16 promoter. In conclusion, Lsh may induce the deacetylation of histone H3 by recruiting HDAC1 to the p16 promoter. These findings elicit speculation about mechanisms that Lsh may regulate p16 silencing (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

A model showing how Lsh may regulate p16 silencing.

It is well known that p16INK4a is an important cell-cycle inhibitor which can induce senescence and repress tumor cell growth (46). Its loss or inactivation is correlated with cell immortality (47). Although p16INK4α plays an important role in cellular senescence and tumorigenesis, its transcriptional control is poorly understood. Here, we report, for the first time to our knowledge, the molecular mechanism by which Lsh regulates the expression of p16INK4α in 2BS cells. However, recent studies have proposed p16-regulatory pathways that are distinct from those described here. Jacobs et al. reported that the oncogene and polycomb-group gene bmi-1 regulates cell proliferation and senescence through the ink4a locus (48). Ohtani et al. proposed a model in which the upregulation of p16INK4α depended on the accumulation of Ets1 and the absence of interference by Id1 during senescence (49). Zheng et al. found that Id1 regulated p16INK4α levels through interactions with E47 (50). Wang et al. reported that a 24-kDa protein might inhibit the expression of p16INK4α by interacting with the INK4α transcription silence element (ITSE) (51). Recently, Gan et al. reported that PPAR-gamma promotes cellular senescence by inducing p16INK4a expression (52); subsequently, Huang et al. found that SIRT1 antagonizes cellular senescence by reducing the expression of p16INK4a and promoting phosphorylation of Rb (53). These findings do not contradict the present conclusions. It is clear that the p16 promoter is subject to multiple levels of control (48,54); therefore, p16 regulation cannot be explained by a single isolated pathway.

In summary, Lsh is one of the critical factors involved in the regulation of cell senescence. We conclude that the high Lsh expression in young cells represses p16INK4a expression, thereby maintaining the proliferative state of 2BS cells. Loss of Lsh expression may lead to increased p16INK4a expression in senescent 2BS cells, which in turn contributes to the onset of cellular senescence. Furthermore, we investigated the molecular mechanism involved Lsh-mediated p16 repression, and established a relationship between chromatin remodeling, gene repression and cell senescence. Future studies will be required to determine the role played by the sequence-specific binding factors to mediate the repression of p16 by Lsh.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Basic Research Programs of China [No. 2007CB507400]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [No.30671064]. Funding for open access charge: National Basic Research Programs of China [No. 2007CB507400].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Drs David W. Lee and Robert J. Arceci for providing constructs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hayflick L. The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res. 1965;37:614–636. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong H, Riabowol K. Differential CDK-inhibitor gene expression in aging human diploid fibroblasts. Exp. Gerontol. 1996;31:311–325. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(95)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarvis CD, Geiman T, Vila-Storm MP, Osipovich O, Akella U, Candeias S, Nathan I, Durum SK, Muegge K. A novel putative helicase produced in early murine lymphocytes. Gene. 1996;169:203–207. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00843-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geiman TM, Tessarollo L, Anver MR, Kopp JB, Ward JM, Muegge K. Lsh, a SNF2 family member, is required for normal murine development. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1526:211–220. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(01)00129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raabe EH, Abdurrahman L, Behbehani G, Arceci RJ. An SNF2 factor involved in mammalian development and cellular proliferation. Dev. Dyn. 2001;221:92–105. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun LQ, Lee DW, Zhang Q, Xiao W, Raabe EH, Meeker A, Miao D, Huso DL, Arceci RJ. Growth retardation and premature aging phenotypes in mice with disruption of the SNF2-like gene, PASG. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1035–1046. doi: 10.1101/gad.1176104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasty P, Campisi J, Hoeijmakers J, van SH, Vijg J. Aging and genome maintenance: Lessons from the mouse? Science. 2003;299:1355–1359. doi: 10.1126/science.1079161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennis K, Fan T, Geiman T, Yan Q, Muegge K. Lsh, a member of the SNF2 family, is required for genome-wide methylation. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2940–2944. doi: 10.1101/gad.929101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park IK, Morrison SJ, Clarke ME. Bmi1, stem cells, and senescence regulation. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:175–179. doi: 10.1172/JCI20800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strahl BD, Allis CD. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 2000;403:41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geiman TM, Durum SK, Muegge K. Characterization of gene expression, genomic structure, and chromosomal localization of hells (Lsh) Genomics. 1998;54:477–483. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang J, Fan T, Yan Q, Zhu H, Fox S, Issaq HJ, Best L, Gangi L, Munroe D, Muegge K. Lsh, an epigenetic guardian of repetitive elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5019–5028. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xi S, Zhu H, Xu H, Schmidtmann A, Geiman TM, Muegge K. Lsh controls Hox gene silencing during development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14366–14371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703669104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang Z, Zhang Z, Zheng Y, Corbley MJ, Tong T. Cell aging of human diploid fibroblasts is associated with changes in responsiveness to epidermal growth factor and changes in HER-2 expression. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1994;73:57–67. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou HW, Lou SQ, Zhang K. Recovery of function in osteoarthritic chondrocytes induced by p16INK4a-specific siRNA in vitro. Rheumatology. 2004;43:555–568. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shay JW, Wright WE. Quantitation of the frequency of immortalization of normal human diploid fibroblasts by SV40 large T-antigen. Exp. Cell Res. 1989;184:109–118. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(89)90369-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, Medrano EE, Linskens M, Rubelj I, Pereira-Smith O. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dole MG, Jasty R, Cooper MJ, Thompson CB, Nunez G, Castle VP. Bcl-xL is expressed in neuroblastoma cells and modulates chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2576–2582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen CT, Gonzales FA, Jones PA. Altered chromatin structure associated with methylation-induced gene silencing in cancer cells: correlation of accessibility, methylation, MeCP2 binding and acetylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4598–4606. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kondo Y, Shen LL, Issa JP. Critical role of histone methylation in tumor suppressor gene silencing in colorectal cancer. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:206–215. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.206-215.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H, Yi X, Sun X, Yin N, Shi B, Wu H, Wang D, Wu G, Shang Y. Differential gene regulation by the SRC family of coactivators. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1753–1765. doi: 10.1101/gad.1194704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frank SR, Schroeder M, Fernandez P, Taubert S, Amati B. Binding of c-Myc to chromatin mediates mitogen-induced acetylation of histone H4 and gene activation. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2069–2082. doi: 10.1101/gad.906601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baur AS, Shaw P, Burri N, Delacretaz F, Bosman FT, Chaubert P. Frequent methylation silencing of p15INK4b (MTS2) and p16INK4a (MTS1) in B-cell and T-cell lymphomas. Blood. 1999;94:1773–1781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGlade CJ, Ellis C, Reedijk M, Anderson D, Mbamalu G, Reith AD, Panayotou G, End P, Bernstein A, Kazlauskas A. SH2 domains of the p85a subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulate binding to growth factor receptors. Mol. Cell Biol. 1992;12:991–997. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herman JG, Graff JR, Myohanen S, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB. Methylation-specific PCR: A novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:9821–9826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng QH, Ma LW, Zhu WG, Zhang ZY, Tong TJ. p21Waf1/Cip1 plays a critical role in modulating senescence through changes of DNA methylation. J. Cell Biochem. 2006;98:1230–1248. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayflick L, Moorhead PS. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res. 1961;25:585–621. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narita M, Nunez S, Heard E, Narita M, Lin AW, Hearn SA, Spector DL, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW. Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell. 2003;113:703–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai CY, Enders GH. P16INK4a can initiate an autonomous senescence program. Oncogene. 2000;19:1613–1622. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lundberg AS, Hahn WC, Gupta P, Weinberg RA. Genes involved in senescence and immortalization. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2000;12:705–709. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campisi J. Cellular senescence as a tumor-suppressor mechanism. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:S27–S31. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan X, Zhai L, Sun R, Li X, Zeng X. INI1/hSNF5/BAF47 represses c-fos transcription via a histone deacetylase-dependent manner. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;337:1052–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang ZK, Davies KP, Allen J, Zhu L, Pestell RG, Zagzag D, Kalpana GV. Cell Cycle Arrest and Repression of Cyclin D1 Transcription by INI1/hSNF5. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:5975–5988. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5975-5988.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan T, Hagan JP, Kozlov SV, Stewart CL, Muegge K. Lsh controls silencing of the imprinted Cdkn1c gene. Development. 2005;132:635–644. doi: 10.1242/dev.01612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duan J, Zhang Z, Tong T. Senescence delay of human diploid fibroblast induced by anti-sense p16INK4a expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:48325–48331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104814200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki T, Farrar JE, Yegnasubramanian S, Zahed M, Suzuki N, Arceci RJ. Stable knockdown of PASG enhances DNA demethylation but does not accelerate cellular senescence in TIG-7 human fibroblasts. Epigenetics. 2008;3:281–291. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.5.6914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldstein S. Replicative senescence: the human fibroblast comes of age. Science. 1990;249:1129–1133. doi: 10.1126/science.2204114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yan Q, Cho E, Lockett S, Muegge K. Association of Lsh, a regulator of DNA methylation, with pericentromeric heterochromatin is dependent on intact heterochromatin. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:8416–8428. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8416-8428.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Narlikar GJ, Fan HY, Kingston RE. Cooperation between complexes that regulate chromatin structure and transcription. Cell. 2002;108:475–487. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00654-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kingston RE, Narlikar GJ. ATP-dependent remodeling and actetylation as regulators of chromatin fluidity. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2339–2352. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Varga-Weisz P. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling factors: Nucleosome shufflers with many missions. Oncogene. 2001;20:3076–3085. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flaus A, Owen-Hughes T. Mechanisms for ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2001;11:148–154. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Munro J, Barr NI, Ireland H, Morrison V, Parkinson EK. Histone deacetylase inhibitors induce a senescence-like state in human cells by a p16-dependent mechanism that is independent of a mitotic clock. Exp. Cell Res. 2004;295:525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White VL, Zhang SH, Lucas D, Chen CS, Farag SS. OSU-HDAC42, a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor, induces apoptosis in a caspase-dependent manner and induces p21WAF1/CIP1 and p16 expression in multiple myeloma cell lines. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2006;108 Abstract 5078. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu LP, Wang X, Li L, Zhao Y, Lu SL, Yu Y, Zhou W, Liu XY, Yang J, Zheng ZX, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitor Depsipeptide activates silenced genes through decreasing both CpG and H3K9 methylation on the promoter. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;28:3219–3235. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01516-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collins CJ, Sedivy JM. Involvement of the INK4a/Arf gene locus in senescence. Aging Cell. 2003;2:145–150. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruas M, Peters G. The p16INK4a/CDKN2A tumor suppressor and its relatives. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1378:F115–F177. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(98)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacobs JJ, Kieboom K, Marino S, DePinho RA, van Lohuizen M. The oncogene and Polycomb-group gene bmi-1 regulates cell proliferation and senescence through the ink4a locus. Nature. 1999;397:164–168. doi: 10.1038/16476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohtani N, Zebedee Z, Huot T.JG, Stinson JA, Sugimoto M, Ohashi Y, Sharrocks AD, Peters G. Opposing effects of Ets and Id proteins on p16INK4a expression during cellular senescence. Nature. 2001;409:1067–1070. doi: 10.1038/35059131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng W, Wang H, Xue L, Zhang Z, Tong T. Regulation of cellular senescence and p16(INK4a) expression by Id1 and E47 proteins in human diploid fibroblast. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:31524–31532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang W, Wu J, Zhang Z, Tong T. Characterization of regulatory elements on the promoter region of p16(INK4a) that contribute to overexpression of p16 in senescent fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:48655–48661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108278200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gan QN, Huang J, Zhou R, Zhu XJ, Wang J, Sun Y, Zhang ZY, Tong TJ. PPARγ accelerates cellular senescence by inducing p16INK4a expression in human diploid fibroblasts. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:2235–2245. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang J, Gan QN, Han LM, Li J, Zhang H, Sun Y, Zhang ZY, Tong TJ. SIRT1 overexpression antagonizes cellular senescence with activated ERK/S6k1 signaling in human diploid fibroblasts. PLos One. 2008;3:e1710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hara E, Smith R, Parry D, Tahara H, Stone S, Peters G. Regulation of p16CDKN2 expression and its implications for cell immortalization and senescence. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996;16:859–867. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.