Abstract

Objective

Smoking cessation and relapse prevention during and after pregnancy reduces the risk of adverse maternal and infant health outcomes, but the economic evaluations of such programs have not been systematically reviewed. This study aims to critically assess economic evaluations of smoking cessation and relapse prevention programs for pregnant women.

Methods

All relevant English-language articles were identified using PubMed (January 1966–2003), the British National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database, and reference lists of key articles. Economic evaluations of smoking cessation and relapse prevention among pregnant women were reviewed. Fifty-one articles were retrieved, and eight articles were included and evaluated. A single reviewer extracted methodological details, study designs, and outcomes into summary tables. All studies were reviewed, and study quality was judged using the criteria recommended by the Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine and the British Medical Journal (BMJ) checklist for economic evaluations.

Results

The search retrieved 51 studies. No incremental cost-effectiveness studies or cost-utility studies were found. A narrative synthesis was conducted on the eight studies that met the inclusion criteria. Roughly one-third employed cost–benefit analyses (CBA). Those conducting CBA have found favorable benefit–cost ratios of up to 3:1; for every dollar invested $3 are saved in downstream health-related costs.

Conclusions

CBA suggests favorable cost–benefit ratios for smoking cessation among pregnant women, although currently available economic evaluations of smoking cessation and relapse prevention programs for pregnant women provide limited evidence on cost-effectiveness to determine optimal resource allocation strategies. Although none of these studies had been performed in accordance with Panel recommendations or BMJ guidelines, they are, however, embryonic elements of a more systematic framework. Existing analyses suggest that the return on investment will far outweigh the costs for this critical population. There is significant potential to improve the quality of economic evaluations of such programs; therefore, additional analyses are needed. The article concludes with ideas on how to design and conduct an economic evaluation of such programs in accordance with accepted quality standards.

Keywords: economic evaluations, pregnant women, relapse prevention, smoking cessation, systematic review

Introduction

Smoking during pregnancy is an important public health and economic issue. It increases the risk of preterm membrane rupture, placental abruption, placenta previa, stillbirth, low birth weight, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) [1], cleft palates and lips, and childhood cancers [2]. A majority of women who smoke (60–67%) do not stop smoking when they learn they are pregnant [3]. While evidence from several studies suggests that smoking cessation programs targeted at pregnant women—especially augmented psychosocial interventions [2] can reduce smoking during and after pregnancy and should be offered [2], it is important to know whether such programs are cost-effective. The tobacco control research community is increasingly interested in the economic, as well as the clinical, implications of interventions designed to reduce tobacco use, especially among critical populations such as pregnant women.

Although they have the potential to be cost-effective if they reduce smoking and thus the incidence of low-birth-weight (LBW) babies, perinatal deaths, and physical, cognitive, and behavioral problems during infancy and childhood, economic evaluations of such programs have not yet been subjected to systematic review.

Policymakers want to know which smoking cessation and relapse prevention programs for pregnant women are both effective and cost-effective—and whether such a program is worth implementing or covering as compared to other interventions or programs in, for example, an insurance package or as a guaranteed benefit as part of a national health service when resources are scarce. Therefore, high-quality evidence for clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness would facilitate resource allocation. This article systematically reviews and critically assesses economic evaluations of smoking cessation and relapse prevention programs among pregnant women. It also highlights the opportunity for research findings on economic evaluations to provide the inputs for developing policies to support programs that help pregnant women quit and remain abstinent. In general, there are four different types of economic evaluations: cost-minimization analysis (CMA), cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), cost–benefit analysis (CBA), and cost-utility analysis (CUA) (see Table 1). In comparing two interventions designed to address the same health problem, CMA searches for the least costly alternative that produces the same health benefit. CEA by contrast compares the per unit effect with the per unit cost on an incremental basis of two different health interventions and CBA measures both the costs and consequences of two or more alternative interventions in terms of the potential dollars gained or saved compared to the dollars invested in the intervention. Lastly, CUA is a type of CEA that employs utilities (e.g., quality-adjusted life-years or QALYs) as the outcome measure to compare and evaluate two or more interventions incrementally. CUA attempts to translate the health outcomes of all interventions into a single outcome measure (e.g., QALYs) in efforts to compare the added value of one program versus another on the same outcome scale.

Table 1.

Types of economic evaluation*

|

Adapted from Drummond et al. [4].

Although a review of the effectiveness of pregnancy-related smoking cessation and relapse prevention programs was performed during the creation of Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence, a US Department of Health and Human Services Clinical Practice Guideline [2], to our knowledge this is the first systematic review of the economic evidence on such programs.

Methods

Search Strategy

Strategies for identifying and selecting economic evaluations for systematic review are described elsewhere [5–13], and our search was consistent with those approaches. We searched PubMed (inception, January 1966–July 2003) and the British National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) (http://www.york.ac.uk/Institute/crd/nhsdhp.htm) for English-language articles. We combined the search terms smoking cessation or relapse prevention with pregnant women and with cost or cost analysis or cost effectiveness or cost benefit or cost utility or economic evaluation or economic or QALY or quality-adjusted or cost per life year, trying different combinations of these key words for both databases. We also manually searched the reference lists of retrieved articles and Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence [2] and selected relevant articles for inclusion. This search resulted in 51 articles related to the search terms. Due to the dearth of literature in this area and because one of our key aims was to assess quality, we originally included all 51 relevant studies identified by our literature search. This sample included a number of different types of economic evaluations (Table 1) and not just cost-utility analyses, as recommended by the Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine [5]. Excluding studies that were not CEA or CUA would have left us with few studies to assess.

After retrieving the original set of 51 articles, we screened for studies that met the following criteria: 1) addressed the identified question; 2) involved original economic analysis (not just CEA, see Table 1); and 3) reported an appropriate outcome metric (an appropriate health outcome such as life expectancy or quit rates even if it was not QALYs) [2]. We coupled these criteria with the standard inclusion criteria for economic evaluation studies presented in the Guide to Community Preventive Studies [9], which require studies to use one of the four analytical methods recommended by Drummond et al. (Table 1) [7]. Employing these criteria allowed us to select studies that: provided sufficient detail on methods and results; were primary studies rather than guidelines or reviews; were published within an appropriate time frame; were written in English; and were conducted in one or more Established Market Economies [9]. The eight studies that met these inclusion criteria were abstracted by a single reviewer; consensus regarding inclusion or exclusion was not relevant to our purposes.

Data Extraction

The data extracted from each full article is delineated in Table 2. One trained person with graduate education in decision analysis and cost, cost–benefit, cost-effectiveness, and cost-utility analyses read every article and extracted and analyzed the data. Data extraction was based on the checklist for reporting reference-case cost-utility analyses recommended by the Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine [5] and on guidelines developed for economic submissions to the British Medical Journal (BMJ). It was also consistent with the data auditing form developed by researchers at the Harvard Center for Risk Analysis (available at: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/cearegistry) (See Table 3). The Panel’s checklist and BMJ guidelines were also used as criteria for evaluating the quality of the economic studies.

Table 2.

Data extracted from included articles

|

Table 3.

Criteria for assessing quality of economic evaluations*

Framing

|

Costs

|

Effects

|

Results

|

Discussion

|

From the checklist for reporting reference-case cost-utility analyses recommended by the Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine and guidelines for economic submissions to the BMJ; also consistent with the data auditing form developed by researchers at the Harvard Center for Risk Analysis.

Data Synthesis

Because of the heterogeneity of study types and our goal of assessing the quality of economic evaluations, we used narrative synthesis [14] rather than formal meta-analysis. In contrast to meta-analysis, narrative synthesis does not include quantitative synthesis. This review summarizes the type, statistical significance, and distribution of a program’s effectiveness and costs. Methodological and intervention differences among studies prevented us from adjusting the original study results to identify the conclusions that would have been obtained, and had the study followed the standards recommended [9], for example, by the Panel (e.g., inclusion of the reference case) [5]. Types of smoking cessation and relapse prevention programs ranged from “usual care” (an intervention lasting less than 5 minutes and consisting of a recommendation to stop smoking with provisional self-help materials and sometimes a referral to a stop-smoking program) to extended psychosocial programs (more intensive counseling) [2]. Meta-analysis of program’s effectiveness has found the latter to be more effective [2].

Results

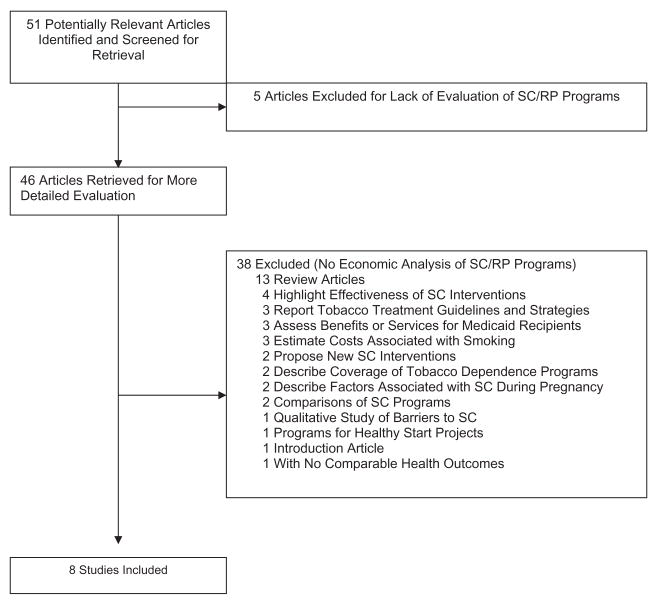

Literature Search: Identification of Economic Analyses

Our search identified 51 potentially relevant studies. Figure 1 delineates a flow chart of the study selection process. A study investigator reviewed the titles and abstracts to determine whether an article contained an economic analysis. This initial review excluded articles that were clearly not economic evaluations or were clearly not related to our subject of interest, as noted by the criteria described above. For example, a search that included the terms costs, smoking cessation, and pregnant women identified a number of studies on the relationship between the costs of neonatal health care and maternal smoking during pregnancy. Although such cost estimates would normally be one component of an analysis of the societal benefits of smoking cessation programs among pregnant women, the studies we identified did not systematically compare costs and benefits or employ one of the four standard types of economic evaluation (Table 1). Of the articles retrieved and reviewed, eight met the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study selection process. RP, relapse prevention; SC, smoking cessation.

Study Descriptions

Table 4 summarizes the key characteristics of the economic analyses we selected, especially their underlying assumptions, methodologies, and conclusions. Although none of these eight studies was an incremental CEA or CUA, or expressed benefits in QALYs gained or saved, a few studies did express benefits in terms of days of life or life-years gained. Moreover, the studies differed significantly in terms of economic study type and main assumptions. The narrative below identifies some ways in which the main assumptions differed and how the investigators arrived at both different and overlapping conclusions about the economic impact of smoking cessation programs among pregnant women. The variation in methods and reporting offer a wide array of research findings for interpretation. Future reviews would benefit from greater consistency in methods and reporting across studies.

Table 4.

Summary of eight economic analyses of smoking cessation programs for pregnant women

| Study, Year (Reference) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Ershoff et al. (1983) [15] | Windsor et al. (1988) [16] | Ershoff et al. (1990) [17] | Marks et al. (1990) [18] |

| Methods | ||||

| Analysis type | CBA | CEA | CBA alongside RCT | Cost savings; CBA |

| Model type | Nonrandomized comparison | RCT/pretest–post-test design | RCT | Unknown, used estimates from Literature |

| Framing | ||||

| Setting and population | 159 pregnant smokers from a network model HMO (California) | 309 pregnant smokers from three public health maternity clinics | 227 pregnant smokers from a large multispecialty group affiliated with a large HMO (California) | Hypothetical “model” program for physician offices |

| Intervention (comparators) |

|

|

|

|

| Perspective | HMO | Agency | HMO | Societal |

| Time horizon | Infant’s first year of life | End of pregnancy | Infant’s first year of life | 35 years |

| Effects | ||||

| Main outcome & benefits measure |

|

|

|

|

| Costs | ||||

| Cost analysis (cost components) |

|

|

|

|

| Base year (costs) | 1980–81 | Unknown | 1985–87 | 1986 |

| Source (costs) | Program and hospital records | Program records | Program and hospital records | Rough estimates, OTA |

| Results | ||||

| Discount rate | N/A | Not reported | N/A | 4% |

| Main sensitivity analysis | None |

|

None |

|

| Summary results |

|

|

|

|

| Shipp et al. (1992) [19] | Windsor et al. (1993) [20] | Hueston et al. (1994) [21] | Pollack (2001) [22] | |

| Methods | ||||

| Analysis type | Break-even point; CEA | CBA alongside randomized pretest–post-test control group design | Break-even point; CEA | Cost per SIDS death averted; CEA |

| Model type | Decision tree | RCT | Decision tree | Conditional logistic regression analysis to estimate SIDS risk |

| Framing | ||||

| Setting and population | Health-care organization (US) | 814 pregnant smokers from four public health maternity clinics in Birmingham, Alabama | American women in first trimester of pregnancy who participated in 1988 National Health Interview Survey. Primary care setting | All recorded US singleton SIDS deaths from 1995 birth cohort with birth weight >500 g from 1995 to 1996 Perinatal Mortality Files |

| Intervention (comparators) |

|

|

|

|

| Perspective | Program | Agency | Not specified | Societal |

| Time horizon | Post-delivery | Lifetime | End of pregnancy | Lifetime |

| Effects | ||||

| Main outcome & benefits measure |

|

|

|

|

| Costs | ||||

| Cost analysis (cost components) | Hospital charges | Personnel time (salary plus fringe) and materials measured alongside clinical trial. Patient time and facilities costs excluded. Net incremental costs of LBW based on OTA estimates. | Costs of prenatal care and delivery from hospital charges in San Francisco | Assumed cost of hypothetical “typical” SC program of $45 (mid-1998 dollars) cost per participant based on Marks et al. (1990) [18] study ($30 in 1986 dollars), with cost inflator to mid-1998 dollars |

| Base year (costs) | 1989 | 1990 | 1989 | mid-1998 |

| Source (costs) | Not specified | RCT & OTA | Decision tree used to model and estimate costs | Adjusted costs assumed in Marks et al. (1990) [18] study |

| Results | ||||

| Discount rate | Not reported | Not reported | N/A | 5% |

| Main sensitivity analysis |

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Summary results |

|

|

|

|

ALA, American Lung Association; BC, benefit–cost ratio; CBA, cost–benefit analysis; CEA, cost-effectiveness analysis; HMO, health maintenance organization; LBW, low birth weight; NBW, normal birth weight; NHIS, National Health Interview Survey; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; OTA, Office of Technology Assessment; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SC, smoking cessation; SIDS, sudden infant death syndrome.

Assessing Economic Evaluation Quality

Methods

Analysis and model type

All eight studies involved some sort of economic analysis although the study type varied considerably. Half of the studies [15,17,18,20] employed a CBA, measuring both the costs and consequences of alternatives in dollars, though the CBA types performed were closer to cost-saving analyses than traditional CBA methods (e.g., valuing a life-year saved in monetary terms) in that they estimate savings in health-care expenditures resulting from not smoking. Two studies employed CEA to estimate the “break-even” cost for a given quit rate [19,21], and one employed CEA to estimate the cost per percentage that quit [16]. One study used CEA to estimate the cost per SIDS death averted [22]. In terms of study design and modeling, three studies [16,17,20] were randomized controlled trials, one was a nonrandomized comparison [15], two employed decision trees to model costs and consequences [19,21], and a third used conditional logistic regression analysis to estimate the consequences of smoking cessation (in terms of SIDS risk) [22]. One study did not specify the model type, but did use estimates from the literature [18].

Framing

Study perspective and time horizon

Two of the studies reviewed reported results from the societal perspective [18,22]. Other points of view included agency [16,20], health maintenance organization (HMO) [15,17], and program [19], while one study [21] did not specify a perspective in their analysis. Although, according to the Panel, employing any perspective other than societal limits the generalizability of the results and weakens the strength of the study findings, alternative perspectives from these studies compliment the societal point of view in providing useful information to program, insurance, and agency representatives. In terms of the time horizon, three studies ended at the end of pregnancy [16,21] or postdelivery [19], while two studies extended through the infant’s first year of life [15,17] and the remaining three studies extended 35 years [18] or a lifetime [20,22] intervention (comparator).

Intervention types varied across studies, with several including advice/counseling supplemented with written materials [16–18,20]. These studies included programs with a 15-minute session with a health counselor, social support, and written materials [20]; a hypothetical model program consisting of a 15-minute counseling session, two follow-up phone calls, and instructional materials [18]; brief counseling and eight booklets mailed weekly [17]; and quit advice supplemented with either an American Lung Association manual or a pregnancy-specific manual [16]. Three studies looked at hypothetical prenatal smoking cessation programs, but did not specify the components of these programs [19,21,22]. One study involved an 8-week home-correspondence program [15]. Half of the studies reviewed analyzed an alternative [15–17,20], comparing interventions to a control group that received usual or standard care, typically less than 5 minutes of counseling plus materials. The other studies did not identify a comparator [18,19,21,22].

Discounting

Two studies indicated a discount rate, ranging from 4% in one study [18] to 5% in another [22]. In all other studies, discounting was either not applicable [15,17,21] or not reported [16,19,20].

Costs

Reporting of direct and indirect costs

The cost components of the cost analysis varied widely across studies. Two studies used hospital charges as proxies for costs [19,21]. For both studies [19,21], direct medical charges related to hospitalization at delivery were compared; one of these studies [21] used a charge cost deflator [5]. One study estimated costs of $45 for a hypothetical “typical” smoking cessation program based on data from other analyses in the field [22]. Windsor et al. [16] included direct programs costs, such as personnel and educational materials, and excluded costs related to facilities, other supplies, and patient time because of similarities in these costs across groups. Marks et al. [18] incorporated direct program costs (for counseling, follow-up calls, and materials), but also included training and overhead costs. Indirect costs were not included, nor were potential maternal health benefits and associated costs. Costs per LBW infant for neonatal intensive care were derived from the Office of Technology Assessment and adjusted to 1986 dollars, as was the lifetime cost of special services from 1 to 35 years because of low birth weight in this study. For the remaining two studies [15,17], one included staff time, overheads, materials costs, and cost savings attributable to the reduced number of LBW babies from an HMO perspective [17], and the other included staff salaries, development and overhead costs, materials costs, and the reduction in hospital costs associated with normal infant birth weight [15].

Costing source and reporting

Reporting costs in a single year from a specified source is crucial for comparison across studies and generalizability of study results. Nearly all studies specified costing source [15–18,20–23], with only one study not reporting the source of costs [19]. The costing sources reported included program records [16], program and hospital records [15,17], randomized controlled trial [20], Office of Technology Assessment [18,20], rough estimates [18], rough estimates combined with the use of a decision tree to model and estimate costs [21], and assumed costs from prior studies [22]. Slightly more than half of the studies reviewed reported base costs in a single year [18–22], while one study reported costs over a 2-year span [15], one reported costs over a 3-year span [17], and one study did not report a base year for costs [16].

Effects

Health outcomes

The health outcomes and benefits measured varied across studies. Most studies included a measure of either smoking status [15], quit rates from primary studies [16,17,20], or quit rates obtained from the literature [18,19,21]. Several studies also employed infant outcomes, including LBW birth prevented [15,17–21], number of preterm births reported [15,19], perinatal death prevented [18], neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) costs prevented [18], life-year gained [18] or saved [22], SIDS death averted [22], and long-term disability prevented [18]. One study assessed maternal health outcomes related to pregnancy, abruptio, hemorrhage, previa, and pre-eclampsia [19]. No studies reported outcome in terms of QALYs [5].

Results

The results from all studies indicated favorable outcomes for intervention methods aimed at reducing smoking during pregnancy and, subsequently, improving maternal and infant health outcomes. The literature reviewed herein suggests significant net positive economic benefits of prenatal smoking cessation interventions. Half of the studies reported results as cost–benefit ratios [15,17,18,20]. Two studies reported overall benefit–cost ratios of 2:1 (for the program) [15] and 3:1 (to the HMO) [17]. These results suggest that from a program perspective $1 invested yields cost savings of nearly $2. Similarly, the results of the HMO study suggest that the returns on investment are even greater from a provider’s perspective, $3 saved for every dollar spent. One study noted a benefit–cost ratio of 3.3:1 for preventing NICU costs and 6.6:1 for preventing long-term disability [18], suggesting smoking cessation before the end of pregnancy produces significant cost savings from the prevention of neonatal complications and long-term disability. Another study reported a range of benefit–cost ratios from 1.8:1 (low estimate) to 4.6:1 (high estimate) and a cost-saving range of $365,728 to $968,320 [20]. One study found estimates of cost per percent that quit ranging from $51 to $118 [16], while another study (from a national perspective) estimated the costs of preventing a LBW birth ($4000) and a perinatal death ($62,542) [18]. The total cost per life-year gained from this study was $2934 [18]. Two studies estimated the “break-even” costs per pregnant woman [19,21] for different quit rates, resulting in a range of $10 to $237 per pregnant woman in one study [19] and of $14 to $135 in another study [21]. A final study reported a cost per SIDS death averted of $210,500 and a cost per life-year saved of $11,000 [22].

Sensitivity analyses

Several studies [16,18–21] conducted sensitivity analyses. Two studies did not employ sensitivity analyses [15,17], one did not specify if sensitivity analyses were conducted [22]. Most studies conducted sensitivity analyses on quit rates [16,18–21], and some analyzed intervention costs [16,20] and hospital charges [19]. Parameters related to infant health such as risk [18,20] or probability of low birth weight, proportion of LBW infants requiring NICU care and relative risk of perinatal death, were also examined [18]. One study analyzed the ranges of the percentage of women smoking at baseline and of the probability of maternal complications [19].

Discussion

This review of the literature on economic evaluations of smoking cessation and relapse prevention programs among pregnant women reveals a dearth of studies on the subject and provides justification for further research support in this critical public health area. Although none of the studies were performed entirely in accordance with Panel recommendations or BMJ guidelines (e.g., none employed incremental CEA or CUA), numerous studies included certain aspects of these guidelines and provided useful research findings on the value of prenatal smoking cessation to women, infants, providers, and society at large. Thus, portions of each study may be used as an example for future analyses. It is also worth noting that, since most of the studies we reviewed were published before the development of the guidelines for conducting and reporting economic evaluations, one would expect some divergence between recommended guidelines and study results, further bolstering efforts of the mid-1990s to standardize economic evaluations to reduce uncertainty among researchers, reviewers, and journal editors about methods and reporting practices. Standards established by the Panel, the Cochrane Group, the BMJ, and others are likely to improve the quality and consistency of future economic evaluations in health and medicine.

Thus, while differences in the design, reporting, and description of economic evaluation and in model assumptions, data definition and estimation, discount rates and perspectives, to a certain extent limit our ability methodologically to draw head-to-head conclusions about the most effective and cost-effective strategies, together these studies offer distinct insights into the value of reducing smoking among pregnant women.

For example, despite the fact that reporting practices of economic analyses varied widely, most studies in this field have employed CBA and have found favorable cost–benefit ratios, even when maternal benefits are excluded. Moreover, estimates of program costs appear to be based on similar assumptions and to be similar. It is unclear why CBA has been the method of choice [24], and it is worth noting that the types of CBA performed in the studies reviewed here are not traditional (e.g., valuing a life-year saved in monetary terms) but are more akin to cost-saving analysis in that they estimate savings in health-care expenditures resulting from not smoking. It appears that the literature has focused on these types of studies because of the interest and ease of estimating hospital costs (primarily costs of neonatal intensive care) associated with not quitting smoking during pregnancy.

The studies that aimed to estimate the break-even cost of smoking cessation programs demonstrated that such programs pay for themselves because, by and large, they save more than they cost. Many studies did not, however, adopt the societal perspective, nor did they include all relevant costs (e.g., training costs), suggesting these research findings are conservative estimates of potential savings. Although it is difficult to say whether such programs produce incremental health gains (at the margin) and to assess the marginal cost of those gains (because few studies used comparable outcome measures [health gains measured in life-years saved or QALYs saved]), resource savings as an outcome is relevant for analyzing the financial investment of prevention programs.

In summary, prenatal smoking cessation offers both health and economic benefits for women, infants, providers, and society. When women quit smoking by the first trimester of their pregnancy, for example, their infants are likely to have the same body weight as infants of nonsmokers and they significantly reduce the risk of intrauterine growth retardation. Prenatal smoking cessation programs are also relatively inexpensive on average, with costs in some cases as low as $25 per person for brief counseling. Combining costs and benefits reveals highly favorable benefit–cost ratios (of up to $6 saved for every dollar invested), significant cost savings (of up to $1,000,000), and modest costs for health gain, ranging from $100 per percent that quit to $4000 per LBW birth prevented to $63,000 per perinatal death prevented to $11,000 per life-year saved and $210,000 per SIDS death averted. By any measure, such programs compare favorably to more than 80% of clinical preventive services that are not cost-saving; in some cases, the cost per life-year saved of these services can range from $165,000 to $450,000. These findings could be considered by state public health departments, Medicaid agencies, employers, and health insurance plans (including managed care) to provide smoking cessation benefits and work with providers on screening, counseling, and behavioral interventions for tobacco use.

A final note on methodology, while such limitations hinder comparisons among programs, they also represent an opportunity for future analyses to better adhere to sound and consistent methodologies as recommended by the Panel and the BMJ. A lack of economic studies is common in health and medicine, however, especially in the area of community prevention services [25]. Thus, even the limited number of economic studies on smoking cessation among pregnant women, although not surprising, signal the value of such studies.

In some respects, however, these results are somewhat surprising, given the general trend toward more systematic reporting in the evaluation of tobacco-related interventions [26]. There has also been a longstanding emphasis in health economics toward standard reporting of study assumptions and basic cost and health outcomes [4].

Our analysis has several limitations. First, it is restricted to a specific intervention type (smoking cessation and relapse prevention) and therefore does not include the economic evaluation of other types of programs that aim to reduce the health risks to mothers and infants during and after pregnancy. Second, as with any review that uses key words in a literature search, it may have missed some relevant studies. Third, an in-depth assessment of the merits of all clinical and economic assumptions and research methods was not made. As noted above, the considerable heterogeneity among study types, methods, main assumptions, interventions, and outcomes precluded a formal meta-analysis and the use of strict quality criteria relating solely to cost-utility analyses. Therefore, we included all studies that met our basic inclusion criteria and derived no weights to assess the significance or quality of any individual study. The lack of comparability across studies limits our ability to determine specific public policy implications.

Despite these challenges, efforts to sort out some of the finer methodological challenges in both the cost and effectiveness elements of CEA will eventually lead to more uniformity in reporting. For example, efforts to enumerate cost categories and determine and measure health benefits (in terms of life-years gained) will eventually improve the generalizability and comparability of the results of CEA. In combination with established standards, such efforts will help in the development of an analytic framework for making future studies more comparable.

In conclusion, ideal studies of economic evaluations of smoking cessation and relapse prevention programs for pregnant women would prospectively apply standardized methods noted herein. Characteristics one would be looking for in such a study would include an economic evaluation planned prospectively alongside a randomized clinical trial in which all inputs consumed in the interventions would be measured and valued alongside the clinical trial to enhance the reliability and validity of intervention costs. Costs collected would include those necessary to reproduce the intervention in a nonresearch setting and such inputs would likely include time spent with clients for intervention delivery and follow-up and materials. The cost analysis would be extended to the societal perspective by including cost savings for neonatal intensive care, chronic medical conditions, and acute conditions during the first year of life and cost savings for maternal health care (cardiovascular and lung diseases). The primary outcome measures would be quit and relapse rates measured during the trial and extended to the societal perspective by converting such rates into life-years saved and QALYs saved. Future benefits would be discounted at a 3% annual rate as recommended by the Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. CEAs employing these data would then be performed from the societal perspective to estimate incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, expressed as net resource cost per life-year gained or QALY gained. Sensitivity analysis performed by varying important parameters singly, and in combination, through clinically meaningful ranges would examine the robustness of the ratio estimates. We are publishing one such study that meets these criteria [27]. The studies reviewed in this article might therefore be seen as useful embryonic elements of a more systematic framework for conducting meaningful and useable analyses of smoking cessation and relapse prevention programs for pregnant women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Neumann, David Paltiel, and Milt Weinstein for helpful comments, and Susan Gatchel, Kimberly Hannon, and Linda Sage for administrative, research, and editing assistance.

Source of financial support: This work was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (grant 5R01CA073242-04). Dr. Ruger is supported by a Career Development Award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant 1K01DA0635810). Conflict of interest statement: To our knowledge neither author has a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material for this article can be found at: http://www.ispor.org/publications/value/ViHsupplementary.asp

References

- 1.West R. Smoking cessation and pregnancy. Fetal Matern Med Rev. 2002;13:181–94. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zapka JG, Pbert L, Stoddard AM, et al. Smoking cessation counseling with pregnant and postpartum women: a survey of community health center providers. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:78–84. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drummond MF, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gold M, Siegel J, Russell L, Weinstein MC. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Lancet. 1999;354:1896–900. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drummond MF, Jefferson TO. Guidelines for authors and peer reviews of economic submissions to the BMJ. BMJ. 1996;313:275–83. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7052.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neumann PJ, Stone PW, Chapman RH, et al. The quality of reporting in published cost-utility analyses, 1976–1997. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:964–72. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-12-200006200-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carande-Kulis VG, Maciosek MV, Briss PA, et al. Methods for systematic reviews of economic evaluations for the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:75–91. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone PW, Teutsch SM, Chapman RH, et al. Cost-utility analyses of clinical preventive services: published ratios, 1976–1997. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:15–23. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saha S, Hoerger TJ, Pignone MP, et al. The art and science of incorporating cost effectiveness into evidence-based recommendations for clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:36–43. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jefferson T, Demicheli V, Vale L. Quality of systematic reviews of economic evaluations in health care. JAMA. 2002;287:2809–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.21.2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pignone M, Somnath S, Hoerger T, et al. Cost-effectiveness analyses of colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review for the U.S. preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:96–106. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-2-200207160-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United Kingdom National Health Service Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Undertaking Systematic Reviews of Research on Effectiveness: CRD Report 4. 2. York: University of York; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ershoff DH, Aaronson NK, Danaher BG, et al. Behavioral, health and cost outcomes of an HMO-based prenatal health education program. Public Health Rep. 1983;98:536–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Windsor RA, Warner KE, Cutter GR. A cost-effectiveness analysis of self-help smoking cessation methods for pregnant women. Public Health Rep. 1988;103:83–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ershoff DH, Quinn VP, Mullen PD, et al. Pregnancy and medical cost outcomes of a self-help prenatal smoking cessation program in a HMO. Public Health Rep. 1990;105:340–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marks JS, Koplan JP, Hogue CJ, et al. A cost–benefit/cost-effectiveness analysis of smoking cessation for pregnant women. Am J Prev Med. 1990;6:282–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shipp M, Croughan-Minihane MS, Petitti DB, et al. Estimation of the break-even point for smoking cessation programs in pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:383–90. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.3.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Windsor RA, Lowe JB, Perkins LL, et al. Health education for pregnant smokers: its behavioral impact and cost benefit. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:201–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hueston WJ, Mainous AG, Farrell JB. A cost–benefit analysis of smoking cessation programs during the first trimester of pregnancy for the prevention of low birth weight. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:353–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pollack HA. Sudden infant death syndrome, maternal smoking during pregnancy, and the cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation intervention. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:432–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McParlane EC, Mullen PD, DeNino LA. The cost effectiveness of an education outreach representative to OB practitioners to promote smoking cessation counseling. Patient Educ Couns. 1987;9:263–74. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(87)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Udvarhelyi IS, Colditz GA, Rai A, et al. Cost-effectiveness and cost–benefit analyses in the medical literature. Are the methods being used correctly? Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:238–44. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-3-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramsey SD. Methods for reviewing economic evaluations of community preventive services: a cart without a horse? Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:15–17. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West R, McNeill A, Raw M. Smoking cessation guidelines for health professionals: an update. Thorax. 2000;55:987–99. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.12.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruger JP, Weinstein MC, Hammond SK, Kearney MH, Emmons KM. Cost-effectiveness of motivational interviewing for smoking cessation and relapse prevention among low-income pregnant women: a randomized control trial. Value Health. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00240.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.