Abstract

Chromosome 14 allelic loss is common in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) and may reflect essential tumor suppressor gene loss in tumorigenesis. An intact chromosome 14 was transferred to an NPC cell line using a microcell-mediated chromosome transfer approach. Microcell hybrids (MCHs) containing intact exogenously transferred chromosome 14 were tumor suppressive in athymic mice, demonstrating that intact chromosome 14 NPC MCHs are able to suppress tumor growth in mice. Comparative analysis of these MCHs and their derived tumor segregants identified 4 commonly eliminated tumor-suppressive CRs. Here we provide functional evidence that a gene, Mirror-Image POLydactyly 1 (MIPOL1), which maps within a single 14q13.1–13.3 CR and that hitherto has been reported to be associated only with a developmental disorder, specifically suppresses in vivo tumor formation. MIPOL1 gene expression is down-regulated in all NPC cell lines and in ≈63% of NPC tumors via promoter hypermethylation and allelic loss. SLC25A21 and FOXA1, 2 neighboring genes mapping to this region, did not show this frequent down-regulated gene expression or promoter hypermethylation, precluding possible global methylation effects and providing further evidence that MIPOL1 plays a unique role in NPC. The protein localizes mainly to the nucleus. Re-expression of MIPOL1 in the stable transfectants induces cell cycle arrest. MIPOL1 tumor suppression is related to up-regulation of the p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p27(KIP1) protein pathways. This study provides compelling evidence that chromosome 14 harbors tumor suppressor genes associated with NPC and that a candidate gene, MIPOL1, is associated with tumor development.

Keywords: microcell-mediated chromosome transfer, MIPOL1, cell cycle arrest, promoter hypermethylation

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a unique malignancy that is particularly prevalent among the southern Chinese but is rare elsewhere. Numerous molecular alterations have been detected in this cancer (1). Allelic loss of chromosome 14 and alterations in chromosome copy numbers are found commonly in NPC (1–3) as well as in a wide variety of other cancers (4–7). Alterations in chromosome 14 also have been reported in both early-onset colon cancers (8) and meningioma progression (9). Hypermethylation and down-regulation of chromosome 14 genes are observed in glioblastomas (10) and oligodendroglial tumors (11). These findings suggest that potential tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) mapping to chromosome 14 have a role in tumorigenesis. Deletion mapping of gastrointestinal (12), bladder (13), and ovarian (14) tumors identified chromosome 14 loci associated with tumor suppression at 14q11.1-q12, 14q12–13, 14q23–24.3, and 14q32.1-q32.2. In our previous NPC study, 2 critical regions (CRs) at 14q11.2–13.1 and 14q32.1 also were identified as being associated with growth suppression. Although CRs presumably harboring candidate TSGs have been identified, no candidate TSGs mapping to chromosome 14 have been identified as yet in NPC. Thus, further investigation of the role of chromosome 14 in NPC tumorigenesis is warranted. It is also of particular interest to us that chromosome 14 loss is associated with cancer metastasis in breast tumors (15) and with poor clinical prognosis for other head and neck cancers (16). Thus, it is possible that a chromosome 14 TSG may be a useful prognostic marker in NPC.

In this study, we obtained functional evidence showing definitively that chromosome 14 is tumor suppressive in NPC. We used a microcell-medicated chromosome transfer (MMCT) approach to investigate whether intact chromosome 14 can functionally complement existing defects in an NPC cell line. CRs and candidate genes were identified. A presumptive TSG is up-regulated in microcell hybrids (MCHs) and down-regulated in tumor revertants arising after a long period of selection in vivo (17). A candidate TSG, Mirror-Image POLydactyly 1 (MIPOL1), was identified in this study. MIPOL1 was first mapped in a patient with a genetic disease resulting in mirror-image polydactyly of hands and feet (18) and mild craniofacial and acallosal central nervous system midline defects (19). Of perhaps only incidental interest is a recent transcriptome screening study identifying the insertion of the DGKB and neighboring ETV1 genes into the MIPOL1 gene, resulting in up-regulation of the ETV1 oncogene in prostate cancer (20). To date, however, the function of MIPOL1 is still unknown. This study links this gene, associated with a developmental disorder, to cancer. We investigated its clinical relevance, cytolocalization, possible mechanisms of inactivation, and its ability to suppress tumor formation in vivo.

Results

Transfer of Intact Chromosome 14 Suppresses HONE1 Tumor Formation.

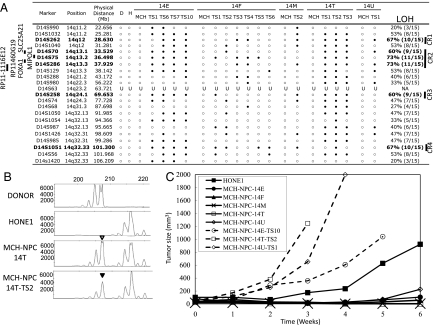

The MMCT approach was used to transfer an intact human chromosome 14 into the tumorigenic NPC cell line, HONE1, using donor MCH-D14-C2. Microsatellite typing and whole-chromosome FISH were used to confirm the successful transfer of chromosome 14 into all 5 MCH cell lines (Fig. 1A and supporting information (SI) Fig. S1). Fig. 1B shows representative results from the microsatellite analysis.

Fig. 1.

Chromosome 14 microsatellite typing and tumorigenicity studies. (A) Microsatellite typing analysis of 5 MCH cell lines (14-E, -F, -M, -T, and -U) and their corresponding TSs. A total of 22 microsatellite markers were used. The donor MCH-D14-C2 (D), recipient cell line HONE1 (H), presence (open circles), absence (filled circles), and uninformative (U) status of markers and CRs are as indicated. The locations of the MIPOL1, SLC25A21, and FOXA1 genes and the RP11–460G19 and RP11–1116E12 BAC clones are shown on the left, and CRs 1–4 are shown on the right. (B) Representative microsatellite analysis of marker D14S75 for donor, HONE1, MCH-NPC-14T, and MCH-NPC-14T-TS2. An inverted open triangle designates the exogenous donor allele transfer, and an inverted filled triangle indicates the loss of an allele in MCH-NPC-14T-TS2, respectively. (C) In vivo tumorigenicity assay of the recipient NPC cell line, HONE1, 5 chromosome 14 MCHs (MCH-NPC-14-E, -F, -M, -T, and -U) and MCH-NPC-14E-TS10, -14T-TS2, and -14U-TS1. The curves represent an average tumor volume of all sites inoculated for each cell population. Statistically significant differences in tumor growth were observed for HONE1 compared with 5 MCHs and their TSs.

The recipient HONE1 cell line is highly tumorigenic in nude mice, with palpable tumors consistently formed within 21 days and reaching a size greater than 900 mm3 by 6 weeks after injection (Fig. 1C and Table S1). The 5 MCHs suppress tumor growth in vivo, and only small tumors were observed 6 weeks after injection.

Tumor Segregant Analysis Delineates Commonly Eliminated Regions and Demonstrates MIPOL1 Association with Tumor Suppression.

Small tumors (less than 250 mm3) form 6 weeks after the injection of chromosome 14 MCHs. All tumor revertants were excised and established as tumor segregant (TS) cell lines for subsequent analysis. The long period required for the emergence of these tumors is consistent with occurrence of in vivo selection from a majority population of non-tumorigenic cells. Using a panel of 22 microsatellite markers spanning the entire chromosome 14q arm, we performed PCR-based microsatellite typing to compare the genotyping of the MCHs and their matched TSs.

We defined 4 commonly eliminated CRs associated with tumor suppression at 14q12 (D14S262; 6 Mb), 14q13.2–13.3 (D14S70, D14S75, and D14S286; 4.63 Mb), 14q24.1 (D14S258; 14 Mb), and 14q32.33 (D14S1051; 2.68 Mb) (Fig. 1A). We re-injected 3 TSs, MCH-NPC-14E-TS10, -14T-TS2, and -14U-TS1, in mice to investigate their tumorigenicity; they were 100% tumorigenic and displayed higher tumor growth kinetics than their matched MCHs (Fig. 1C), perhaps reflecting their in vivo selection in mice.

Based on the microsatellite typing and BAC FISH results, the MIPOL1 gene (36.737–37.090 Mb) located in CR2 between markers D14S75 and D14S286 that showed the highest loss (up to 73%) in the TSs (Fig. 1A and Fig. S2) was chosen for further study. BAC FISH with probes RP11–460G19 (36.831–37.010 Mb), which overlaps with MIPOL1, and with RP11–1116E12 (38.087–38.242 Mb), which is adjacent to the MIPOL1 region, showed 6 copies of the region where MIPOL1 maps in MCH-NPC-14T. Selective loss of 1 copy was observed with FISH analysis for both BACs in its TS, namely MCH-NPC-14T-TS2 (Fig. S2). These findings are consistent with the loss of MIPOL1 and the nearby CR in the TS being associated with a subsequent increased tumorigenicity but do not exclude the possibility that other regional genes may be involved.

MIPOL1 Gene and Protein Expression Levels in MCHs, TSs, and NPC Cell Lines and Patient Tumors.

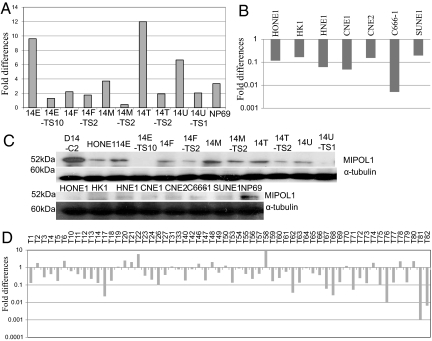

Up-regulation of MIPOL1 at both protein and mRNA levels was observed in the MCHs when compared with HONE1 cells, and extensive down-regulation of MIPOL1 was observed in the corresponding TSs (Fig. 2 A and C). MIPOL1 also was down-regulated in all 7 NPC cell lines when compared with a nontumorigenic immortalized normal nasopharyngeal epithelial cell line, NP69 (Fig. 2 B and C). The possible clinical relevance of MIPOL1 was investigated in 60 patient tumors: 38 (63%) showed down-regulation of MIPOL1 mRNA levels when compared with the corresponding nontumor tissues (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Expression levels of MIPOL1 in MCHs, TSs, NPC cell lines, and NPC tissues. (A) Q-PCR analysis of MIPOL1 expression in MCHs and their corresponding TS cell lines. The immortalized NP cell line, NP69, was used as a control for normal MIPOL1 expression. Fold changes of MIPOL1 expression were compared with HONE1 for 5 MCH cell lines and their corresponding TS cell lines. (B) Q-PCR analysis of MIPOL1 expression in 7 NPC cell lines. The fold changes of NPC cell lines were compared with the immortalized NP cell line, NP69. (C) MIPOL1 protein expression levels in the donor cell line (MCH-D14-C2), recipient cell line (HONE1), MCHs, TSs, and NPC cell lines. α-Tubulin was used for normalization in the Western blots. (D) Q-PCR analysis of 60 pairs of NPC biopsy specimens. Fold changes of MIPOL1 expression in each tumor tissue were compared with the matched nontumor tissue.

Nuclear Localization of MIPOL1 Protein.

By immunofluorescence staining, MIPOL1 protein was observed predominantly in the nucleus, and only a small fraction was observed in the cytoplasm of the NP69 cells (Fig. S3). The MIPOL1 transfectant, MIPOL1-C16, was established using a previously described tetracycline-regulated vector, pETE-Bsd, and the genetically engineered HONE1–2 cell line (21). When the MIPOL1 gene was switched on in the absence of doxycycline (dox), MIPOL1 protein localized mainly to the nucleus, as observed by immunofluorescence staining (Fig. S3). This nuclear localization also was seen in tissue sections of nonkeratinizing undifferentiated carcinoma (NPC) and normal epithelium using antibody specific for MIPOL1 (Fig. S4). No significant cytoplasmic staining was seen, and the adjacent stroma was negative.

Silencing MIPOL1 Gene Expression by Promoter Hypermethylation and Loss of Heterozygosity.

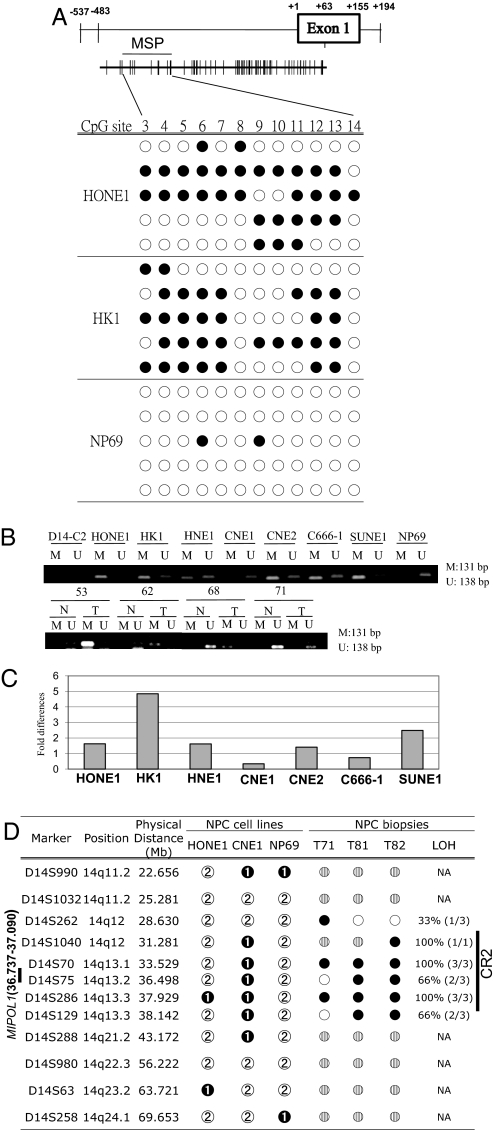

Bisulfite genomic sequencing (BGS) showed a high frequency of methylation of 12 CpG sites in the MIPOL1 promoter in NPC cell lines HONE1 and HK1 but not in the immortalized normal nasopharyngeal epilithelial cell line NP69 (Fig. 3A). Using methylation-specific PCR (MSP) primers located within those 12 CpG sites, we also observed methylated alleles in 6 NPC cell lines. In contrast, NP69 and CNE1 had only the unmethylated allele (Fig. 3B). The chromosome 14 microcell donor, MCH-D14-C2, which shows only the unmethylated allele, was used as a control. Promoter hypermethylation was observed in 3 MIPOL1 down-regulated NPC tissues, T53, T62, and T68, when compared with their corresponding normal tissues, whereas T71 showed only the unmethylated allele (Fig. 3B). This finding suggests promoter hypermethylation is an important mechanism for silencing MIPOL1 expression. With the use of the demethylation reagent, 5-aza-2′deoxycytidine, restoration of MIPOL1 expression was observed in all NPC cell lines by quantitative RT-PCR (Q-PCR), with the exception of the CNE1 cell line, in which only the unmethylated allele was observed. These results further confirm the role of promoter hypermethylation in NPC (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Mechanisms inducing MIPOL1 down-regulation. (A) Location of MIPOL1 promoter region (positions −537 to +194), BGS primers amplicon (positions −483 to +63), and MSP primers amplicon (positions −456 to −324) are shown. BGS analysis of the MIPOL1 promoter region in the MIPOL1 down-regulated cell lines HONE1 and HK1 and in the MIPOL1-expressing cell line, NP69. Unmethylation (open circles) and methylation (filled circles) status of CpG sites are as indicated. The location of the MSP amplicon is indicated. (B) MSP analysis of the MIPOL1 promoter region. We analyzed 7 NPC cell lines and 4 pairs of NPC patient biopsies that show MIPOL1 down-regulation. The MCH-D14-C2 and NP69 MIPOL1-expressing cell lines were used as unmethylated controls. Sizes of the PCR amplicons are shown on the right. Methylation (M) and unmethylation (U) of allele are as indicated. (C) Re-expression of MIPOL1 in all NPC cell lines after 5 μM 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine treatment. The expression levels of MIPOL1 were determined by Q-PCR. The fold changes were compared with the untreated cell lines. (D) We used 12 microsatellite markers for LOH study of 3 cell lines (HONE1, CNE1, and NP69) and 3 NPC patient biopsies (T71, 81, and 82). The MIPOL1 promoter is unmethylated in the CNE1 cell line. We investigated 3 NPC tissues showing down-regulation of MIPOL1. NP69 was used as control. The presence (white circles), absence (black circles), not determined (gray circles), homozygous pattern (black circles with “1” in the center), and heterozygous pattern (gray circles with “2” in the center) status of markers are as indicated.

In CNE1, microsatellite typing detected a continuous region of homozygosity for 6 markers spanning a 11.9-Mb region from D14S1040 to D14S288 (Fig. 3D). NP69 and HONE1, in contrast, showed heterozygous patterns for 10 of 12 markers. These results are consistent with the loss of 1 copy of that particular region in CNE1. Three available pairs of MIPOL1 down-regulated NPC patient biopsies (T71, T81, and T82) (Fig. 2D) and showed high loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in CR2 in tumor tissues. Thus, both promoter hypermethylation and LOH are likely to be important mechanisms for silencing MIPOL1 expression in both cell lines as well as in primary tumors.

To rule out the possibility of global methylation changes in the 14q region where MIPOL1 maps and to verify that the frequent down-regulation and promoter hypermethylation of MIPOL1 is unique in CR2, the gene expression and the methylation status of 2 neighboring genes, SLC25A21 (36.219–36.711 Mb) and FOXA1 (37.128–37.134 Mb), were studied. No consistent change in SLC25A21 and FOXA1 expression was observed in the 5 MCH and TS pairs (Fig. S5A). In addition, gene expression analysis shows that SLC25A21 was down-regulated in only 2 of 7 NPC cell lines (CNE1 and C666–1), in contrast to MIPOL1, which was down-regulated in all these cell lines. HK1 was the only cell line showing down-regulated FOXA1 expression (Fig. S5B). SLC25A21 and FOXA1 showed methylation in the SLC25A21 promoter only in C666–1 cells, which displayed decreased SLC25A21 expression (Fig. S5C). Taken together, the 2 genes mapping near MIPOL1 did not show frequent down-regulated gene expression or promoter hypermethylation in NPC cell lines, in contrast to MIPOL1. This finding provides further evidence of the importance of the MIPOL1 gene, mapping to CR2, in NPC tumorigenesis.

MIPOL1 Suppresses Tumor Growth in Vivo.

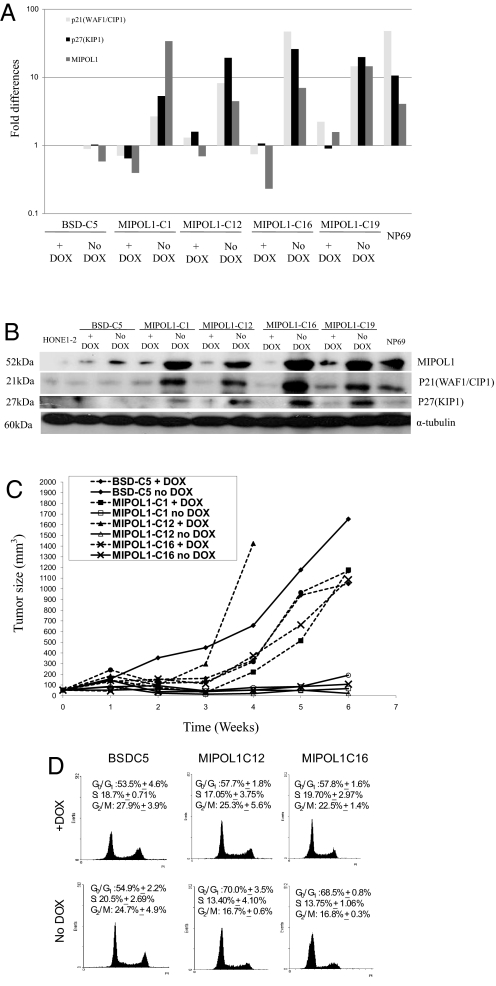

The previously described tetracycline-regulated gene expression system (21) was used to establish stable MIPOL1-expressing clones. MIPOL1-C1, MIPOL1-C12, MIPOL1-C16, and MIPOL1-C19 which show MIPOL1 over-expression, were selected for further studies after Q-PCR and Western blot screening (Fig. 4 A and B). In the absence of dox, the gene expression in this inducible system is switched on; all 4 MIPOL1 transfectant clones show up-regulation of MIPOL1 when compared with the blasticidin (BSD)-C5 control. Their gene and protein expression levels are similar to or higher than those in the NP69 control. In the presence of dox, the gene expression levels of MIPOL1 are reduced significantly.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of MIPOL1 stable transfectants. (A) Q-PCR analysis of MIPOL1, p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p27(KIP1) in MIPOL1 stable transfectants (MIPOL1-C1, -C12, -C16 and -C19) and vector-alone control (BSD-C5) (±dox). Fold changes of MIPOL1 expression in each cell line were compared with the BSD-C5 (+dox) control. NP69 was used as a control for normal MIPOL1 expression. (B) Western blot analysis of MIPOL1, p21(WAF1/CIP1), and p27(KIP1) proteins in the MIPOL1 stable transfectants and vector-alone controls (±dox). α-Tubulin was used for normalization in the Western blots. (C) In vivo tumorigenicity assay of MIPOL1 stable transfectants and vector-alone controls (±dox). The curves represent an average tumor volume of all sites inoculated for each cell population. Differences observed between the MIPOL1-expressing clones, vector alone, and their corresponding +dox controls are statistically significant. (D) Representative FACSorting analysis of propidium iodide-stained BSD-C5 and MIPOL1-C12 and -C16 clones. The average percentage of cells in G0-G1, S, and G2-M phases is shown.

In the in vivo tumorigenicity assay, large tumors formed in all 6 sites injected with the vector-alone control, BSD-C5 (±dox) within 14 to 21 days (Fig. 4C and Table S2). All 4 independent MIPOL1-expressing clones (−dox) suppress tumor formation when MIPOL1 is expressed. When MIPOL1 expression is switched off with dox, the tumorigenicity is similar to that of BSD-C5 control. The differences in tumor growth kinetics between MIPOL1-expressing clones, vector-alone control, and their corresponding +dox controls are statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Table S2).

MIPOL1-Associated p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p27(KIP1) Expression and G0/G1 Cell Cycle Arrest.

In microarray analysis of chromosome 14 MCHs versus their matched TSs, consistent up-regulation of p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p27(KIP1) in the MCHs and down-regulation in the corresponding TSs was observed (Table S3). This observation was validated by microarray analysis of the current MIPOL1 stable transfectants versus the vector alone in the presence or absence of dox to regulate MIPOL1 gene expression in those stable clones (Table S3). There is up-regulation of p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p27(KIP1) genes when MIPOL1 expression is induced. Because these 2 genes were among the top candidates differentially expressed in the microarray analysis, their relationships with MIPOL1 were investigated further by studying their gene and protein expression levels in the MIPOL1-stable clones. Over-expression of MIPOL1 is associated with increased expression of both p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p27(KIP1), when compared with the vector-alone control. p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p27(KIP1) expression levels return to those of vector-alone control when the gene is shut off (Fig. 4 A and B). These results are consistent with MIPOL1 expression correlating with p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p27(KIP1) expression.

To study further the tumor-suppressive mechanism of MIPOL1, the cell cycle status of MIPOL1-C12 and -C16 and BSD-C5 was studied. When MIPOL1 is expressed in MIPOL1-C12 and -C16 (−dox), there are significant increases in the relative numbers of cells in G0/G1 phase, from 54.9% to 70.0% and 68.5% (P < 0.05), respectively. In the presence of dox, there is no significant change in the number of cells in G0/G1 phase among BSD-C5, MIPOL1-C12, and MIPOL1-C16 cell lines (53.5%, 57.7%, and 57.8%, respectively). These results suggest expression of MIPOL1 can induce G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in the stable transfectants (Fig. 4D).

Discussion

In this study, we provide functional evidence in NPC that transfer of an intact exogenous chromosome 14 suppresses tumor growth in vivo and that TSs exhibit tumorigenicity only after nonrandom elimination of CRs. Re-injection of the TSs into nude mice further confirms that the elimination of those CRs is critically related to the emergence of tumors. Interestingly, the TSs show higher tumor growth rates than the original HONE1 cell line. This phenomenon also was observed in 1 chromosome 14 TS derived from a tumor-suppressive esophageal carcinoma MCH (22) and presumably results from the selection in mice for aggressively growing cells capable of tumor formation in the mouse. Our previous MMCT studies showed that the transfer of chromosomes 9 and 17 into the same HONE1 cell line does not result in tumor suppression (23), suggesting that the tumor-suppressive effects of chromosome 14 in NPC are chromosome specific.

The MIPOL1 gene located within CR2 was identified as a candidate TSG in NPC. Down-regulation of MIPOL1 mRNA in NPC cell lines and patient biopsies further confirms the importance of MIPOL1 in NPC development. Nuclear localization of MIPOL1 was demonstrated by both immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical staining. Immunohistochemical staining did not reveal a significant down-regulation of MIPOL1 protein in the tumor versus normal epithelial cells. However, this method is not particularly quantitative. By contrast, Q-PCR is more sensitive for examining differences in expression between tumor and nontumor tissues.

Both promoter hypermethylation and allelic loss play a role in silencing MIPOL1 expression in NPC cell lines and tumor tissues. Low frequencies of down-regulation and promoter hypermethylation in 2 nearby genes, SLC25A21 and FOXA1, suggest the inactivation of MIPOL1 is unique and that there are no global methylation changes to the 2 neighboring genes mapping to this region in NPC.

A tetracycline-regulated inducible system was used to eliminate the effects of clonal variation. The same clones (±dox) are used together for analysis, and only the transgene expression levels vary. We selected 4 independent MIPOL1-expressing clones showing over-expression of MIPOL1 for functional assays. Both the protein and RNA expression levels of MIPOL1 in the MIPOL1-C12 are similar to those in the immortalized normal cell line NP69. MIPOL1 shows tumor-suppressive activity in the HONE1 cells. The nuclear localization of the MIPOL1 protein in the stable transfectant, NP69, and nontumor epithelium suggests that the function of MIPOL1 protein expression in the stable clones is similar to that in the NP69 condition. All 4 independent clones induce tumor suppression in the in vivo assay only when the gene is expressed, not when the gene expression is shut down. Our results provide strong evidence that MIPOL1 is tumor suppressive in NPC.

The low protein expression levels of MIPOL1 observed in HONE1 cells suggest that MIPOL1 may belong to the class of genes that predispose to cancer through haploinsufficiency in the hemizygous state and therefore may not need a second mutation in the remaining wild-type allele in tumors (24, 25). The expression level of MIPOL1 gene in the stable transfectant MIPOL1-C19 (+dox) further confirms this hypothesis. Its leaky expression results in MIPOL1 levels that are higher than in the vector alone but lower than in NP69. Expression higher than the level observed in the leaky clone is tumor suppressing.

Over-expression of MIPOL1 protein induces G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and up-regulation of 2 negative regulators of G1 progression, the well-studied TSGs, p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p27(KIP1). These results are consistent with the tumor-suppressive effect of MIPOL1 being involved in these 2 common TSG pathways. Down-regulation of p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p27(KIP1) correlates with more aggressive prostate cancer (26). Loss of expression of p27(KIP1) was correlated with local recurrence in NPC (27, 28). Our results add support to the notion that the functional role of MIPOL1 in NPC suppression is associated with the induction of expression of p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p27(KIP1), proteins that are associated with suppression of tumor growth in vivo. Further studies are required to investigate the actual functional role of MIPOL1 in the p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p27(KIP1) TSG pathways.

In conclusion, these studies provide clear evidence that the intact chromosome 14 suppresses tumor growth in NPC. A candidate TSG, MIPOL1, was identified and appears to play an essential role in NPC development. Our evidence suggests MIPOL1 is a candidate TSG. This interesting but little-studied gene of unknown function is well conserved in evolution and is associated with a developmental disorder resulting in polydactyly. Importantly, our studies now provide evidence that MIPOL1 expression also is associated with cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

The donor cell line MCH-D14-C2, which contains an intact human chromosome 14 tagged with a neomycin resistance gene, MCH, TS, 7 NPC cell lines (HONE1, HK1, HNE1, CNE1, CNE2, C666–1, and SUNE1), a tetracycline transactivator-producing cell line (HONE1–2), and an immortalized nasopharyngeal epithelial cell line (NP69) were cultured as previously described (21, 29–32). In the current study, each of the MCHs injected into nude mice exhibited a delayed latency period before tumor formation; these tumors subsequently were excised and reconstituted into tissue culture to establish the TS cell lines used in the subsequent assays. Three TSs, MCH-NPC-14E-TS10, -14T-TS2, and -14U-TS1, were cultured for 4 to 8 weeks before being re-injected into nude mice.

NPC Tissue Specimens.

Matched normal nasopharyngeal and NPC biopsies from 60 NPC patients were collected from Queen Mary Hospital from 2006 to 2008, as previously described (33). Approval for this study was obtained from the Hospital Institutional Review Board at the University of Hong Kong. Fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy was used to obtain the paired normal and tumor biopsy materials. Tumor tissues were obtained directly from the site of tumor growth. If tumors were localized to 1 side, the normal tissue samples were taken from the contralateral side having a normal mucosal appearance and no evidence of contact bleeding. For patients who had bilateral tumor involvement, normal tissues were taken from the nasal cavity.

Microcell-Mediated Chromosome Transfer.

The microcell donor, MCH-D14-C2, was used to transfer intact chromosome 14 into HONE1 cell lines as described (30, 34). MCHs were obtained after 3 to 4 weeks' selection.

Whole-Chromosome and BAC FISH Analysis.

The whole chromosome 14 probe, WCP 14 SpectrumGreenTM (Vysis) and BAC clones RP11–460G19 and RP11–116E12 (Invitrogen) were used for FISH analysis, as previously described (35, 36).

PCR-Based Microsatellite Typing Analysis.

A total of 22 microsatellite markers spanning the whole chromosome 14q arm was used. Sequence information was from the NCBI database. The ABI PRISM™ 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used to analyze the PCR amplicon using GeneScan and Genotyper software as previously described (35).

In Vivo Tumor Growth and Tumor Segregant Analysis.

A total of 107 cells from each cell line analyzed was injected s.c. in 6 sites in three 4- to 8-week-old female athymic BALB/c nu/nu mice, as described (29). The mice were supplied by the Animal Care Facility (ACF), Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. All animal procedures followed protocols approved by the Department of Health (HKSAR). Tumors that formed 12 weeks after injection were excised and established as cell lines designated as TSs (37).

Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR Analysis.

Q-PCR was performed as previously described (36) in a Step-One Plus machine (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan PCR core reagent kits, MIPOL1- and GAPDH-specific primers and probes, and SYBR-green PCR core reagent kits (Applied Biosystems. Primer sequences for p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p27(KIP1) are listed in Table S4.

Western Blot Analysis.

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (31). Primary antibodies of MIPOL1 (1:1000; HPA002893; Sigma-Aldrich), p21(WAF1/CIP1) (1:500; sc-6246; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p27(KIP1) (1:1000; sc-1641; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and α-tubulin (1:10,000; Calbiochem) were used.

Immunofluorescence Staining.

The MIPOL1-expressing cell line NP69 was used for immunofluorescence microscopy, as previously described (38). The immunofluorescence images were obtained using an Eclipse 90i confocal microscope (Nikon).

Immunohistochemical Staining.

Immunohistochemistry for MIPOL1 antibody was performed with anti-MIPOL1 antibody (1:300; HPA002893; Sigma) as described (39). A case of nonkeratinizing undifferentiated NPC (according to World Health Organization criteria) was retrieved from the files of the Department of Pathology, Queen Mary Hospital.

Bisulfite Genomic Sequencing and Methylation-Specific PCR Analysis.

The bisulfite treatment of sample DNAs was carried out as previously described (36). A 731-bp fragment at chromosome 14 from 36736370–36737100 bp (Gene2Promoter, Genomatix) (positions −537 to +194) was identified as a MIPOL1 putative promoter region by Gene2Promoter (Genomatix). BGS analysis of immortalized and NPC cell lines was performed as previously described (22).

MSP primers for determining MIPOL1 promoter hypermethylation status (positions −456 to −324), which are located within the hypermethylation region confirmed by BGS (Fig. 3A), were used. Primers were designed according to the MethPrimer guide (21), and MSP was performed as described (36). All BGS and MSP primer sequences are listed in Table S4.

5-Aza-2′-Deoxycytidine Treatment.

All NPC cell lines were treated with 5 μM 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Sigma) for 5 days before analysis, as described (40).

Gene Transfection.

The wild-type MIPOL1 full-length ORF (≈1.3 kb) was cloned from a nontumorigenic immortalized nasopharyngeal epithelial cell line, NP69. Its sequences were confirmed to be identical to that in the NCBI database. The MIPOL1 gene was cloned into the pETE-BSD vector (21). Transfection into HONE1–2 cell line was performed with Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen as previously described (36).

Cell Cycle Analysis.

The cell cycle distribution of each cell line was analyzed by FACScan (Becton Dickinson) flow cytometry as described (36).

Statistical Analysis.

All in vitro assay results represent the arithmetic mean ± SE of triplicate determinations of at least 2 independent experiments. Student's t test was used to determine the confidence levels in group comparisons. The χ2 and Fisher's Exact tests were used to analyze significant differences of MIPOL1 gene expression observed by Q-PCR. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

Financial support was provided by the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, People's Republic of China, Grant 661507 to M.L.L. and by the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, Swedish Institute, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, and Karolinska Institute to E.R.Z.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0900198106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lo KW, et al. High resolution allelotype of microdissected primary nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2000;60(13):3348–3353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shao J, et al. High frequency loss of heterozygosity on the long arms of chromosomes 13 and 14 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Southern China. Chinese Medical Journal. 2002;115(4):571–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mutirangura A, Pornthanakasem W, Sriuranpong V, Supiyaphun P, Voravud N. Loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 14 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1998;78(2):153–156. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19981005)78:2<153::aid-ijc5>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshimoto T, et al. High-resolution analysis of DNA copy number alterations and gene expression in renal clear cell carcinoma. J Pathol. 2007;213(4):392–401. doi: 10.1002/path.2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu J, et al. High-resolution genome-wide allelotype analysis identifies loss of chromosome 14q as a recurrent genetic alteration in astrocytic tumours. Br J Cancer. 2002;87(2):218–224. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoshi M, et al. Detailed deletion mapping of chromosome band 14q32 in human neuroblastoma defines a 1.1-Mb region of common allelic loss. Br J Cancer. 2000;82(11):1801–1807. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ihara Y, et al. Allelic imbalance of 14q32 in esophageal carcinoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2002;135(2):177–181. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(01)00654-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mourra N, et al. High frequency of chromosome 14 deletion in early-onset colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(11):1881–1886. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon M, et al. Allelic losses on chromosomes 14, 10, and 1 in atypical and malignant meningiomas: A genetic model of meningioma progression. Cancer Res. 1995;55(20):4696–4701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tepel M, et al. Frequent promoter hypermethylation and transcriptional downregulation of the NDRG2 gene at 14q11.2 in primary glioblastoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(9):2080–2086. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felsberg J, et al. DNA methylation and allelic losses on chromosome arm 14q in oligodendroglial tumours. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2006;32(5):517–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2006.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Rifai W, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Andersson LC, Miettinen M, Knuutila S. High-resolution deletion mapping of chromosome 14 in stromal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract suggests two distinct tumor suppressor loci. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;27(4):387–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang WY, Cairns P, Schoenberg MP, Polascik TJ, Sidransky D. Novel suppressor loci on chromosome 14q in primary bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55(15):3246–3249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bandera CA, et al. Deletion mapping of two potential chromosome 14 tumor suppressor gene loci in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57(3):513–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Connell P, et al. Loss of heterozygosity at D14S62 and metastatic potential of breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1999;91(16):1391–1397. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.16.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pehlivan D, et al. Loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 14q is associated with poor prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134(12):1267–1276. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robertson GP, Hufford A, Lugo TG. A panel of transferable fragments of human chromosome 11q. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1997;79(1–2):53–59. doi: 10.1159/000134682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondoh S, et al. A novel gene is disrupted at a 14q13 breakpoint of t(2;14) in a patient with mirror-image polydactyly of hands and feet. Journal of Human Genetics. 2002;47(3):136–139. doi: 10.1007/s100380200015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamnasaran D, et al. Rearrangement in the PITX2 and MIPOL1 genes in a patient with a t(4;14) chromosome. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2003;11(4):315–324. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maher CA, et al. Transcriptome sequencing to detect gene fusions in cancer. Nature. 2009;458(7234):97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature07638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Protopopov AI, et al. Human cell lines engineered for tetracycline-regulated expression of tumor suppressor candidate genes from a frequently affected chromosomal region, 3p21. The Journal of Gene Medicine. 2002;4(4):397–406. doi: 10.1002/jgm.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ko JM, et al. Monochromosome transfer and microarray analysis identify a critical tumor-suppressive region mapping to chromosome 13q14 and THSD1 in esophageal carcinoma. Molecular Cancer Research. 2008;6(4):592–603. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng Y, et al. A functional investigation of tumor suppressor gene activities in a nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line HONE1 using a monochromosome transfer approach. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;28(1):82–91. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(200005)28:1<82::aid-gcc10>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fero ML, Randel E, Gurley KE, Roberts JM, Kemp CJ. The murine gene p27Kip1 is haplo-insufficient for tumour suppression. Nature. 1998;396(6707):177–180. doi: 10.1038/24179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang B, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 is a new form of tumor suppressor with true haploid insufficiency. Nat Med. 1998;4(7):802–807. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roy S, et al. Downregulation of both p21/Cip1 and p27/Kip1 produces a more aggressive prostate cancer phenotype. Cell Cycle (Georgetown, Texas) 2008;7(12):1828–1835. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.12.6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hwang CF, et al. Low expression levels of p27 correlate with loco-regional recurrence in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Lett (Shannon, Irel.) 2003;189(2):231–236. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baba Y, et al. Reduced expression of p16 and p27 proteins in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 2001;25(5):414–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng Y, et al. Functional evidence for a nasopharyngeal carcinoma tumor suppressor gene that maps at chromosome 3p21.3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(6):3042–3047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng Y, et al. Monochromosome transfer provides functional evidence for growth-suppressive genes on chromosome 14 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;37(4):359–368. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lung HL, et al. TSLC1 is a tumor suppressor gene associated with metastasis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66(19):9385–9392. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang H, et al. Sequential cytogenetic and molecular cytogenetic characterization of an SV40T-immortalized nasopharyngeal cell line transformed by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 gene. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;150(2):144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lung HL, et al. Characterization of a novel epigenetically-silenced, growth-suppressive gene, ADAMTS9, and its association with lymph node metastases in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(2):401–408. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lung HL, et al. Identification of tumor suppressive activity by irradiation microcell-mediated chromosome transfer and involvement of alpha B-crystallin in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(6):1288–1296. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ko JM, et al. Functional evidence of decreased tumorigenicity associated with monochromosome transfer of chromosome 14 in esophageal cancer and the mapping of tumor-suppressive regions to 14q32. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;43(3):284–293. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheung AK, et al. Functional analysis of a cell cycle-associated, tumor-suppressive gene, protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type G, in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68(19):8137–8145. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng Y, et al. Mapping of nasopharyngeal carcinoma tumor-suppressive activity to a 1.8-megabase region of chromosome band 11q13. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;34(1):97–103. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leung AC, et al. Frequent decreased expression of candidate tumor suppressor gene, DEC1, and its anchorage-independent growth properties and impact on global gene expression in esophageal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(3):587–594. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicholls JM, et al. Time course and cellular localization of SARS-CoV nucleoprotein and RNA in lungs from fatal cases of SARS. PLoS Med. 2006;3(2):e27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lung HL, et al. Fine mapping of the 11q22–23 tumor-suppressive region and involvement of TSLC1 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;112(4):628–635. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.