Abstract

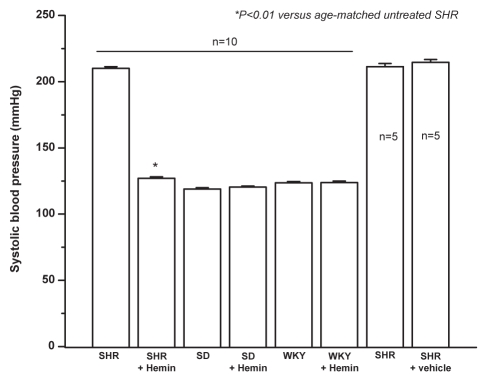

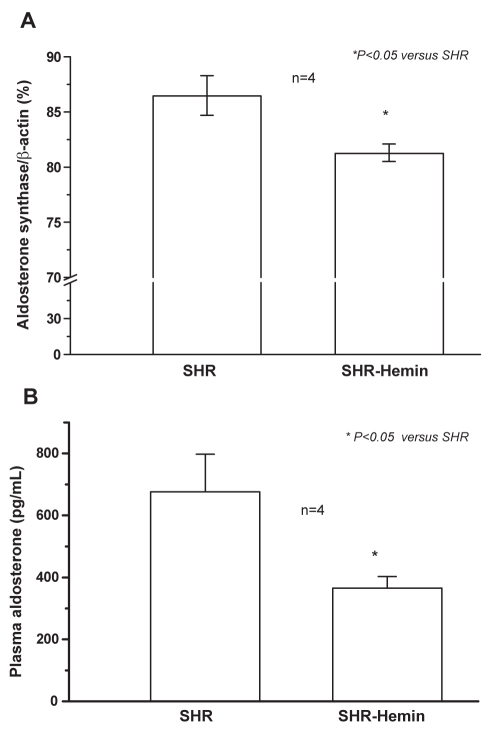

The chronic intraperitoneal administration of the heme oxygenase inducer, hemin (15 mg/kg daily), for three weeks reduced blood pressure in adult spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) from 210.1±1.03 mmHg to 127±0.9 mmHg (n=10, P<0.01) but had no effect on age-matched normotensive Wistar-Kyoto or Sprague-Dawley strains. The antihypertensive effect of hemin was accompanied by reduced expression of aldosterone synthase messenger RNA and depleted levels of plasma aldosterone (675.7±121.6 pg/mL versus 365.7±37 pg/mL; n=4, P<0.05).

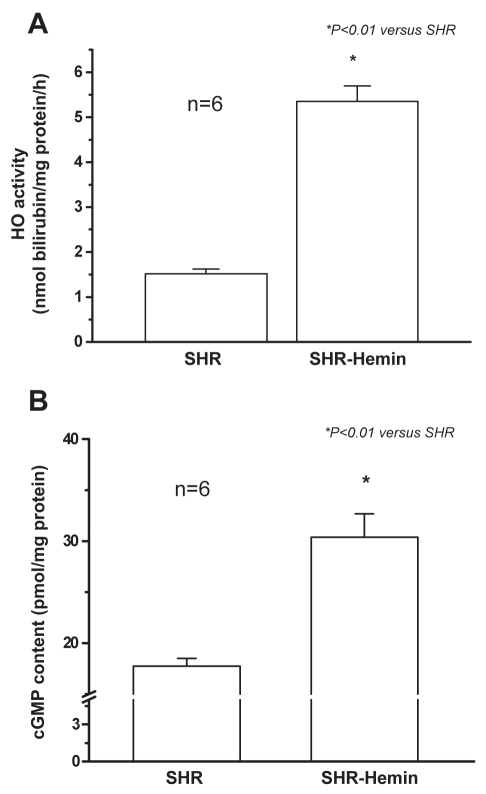

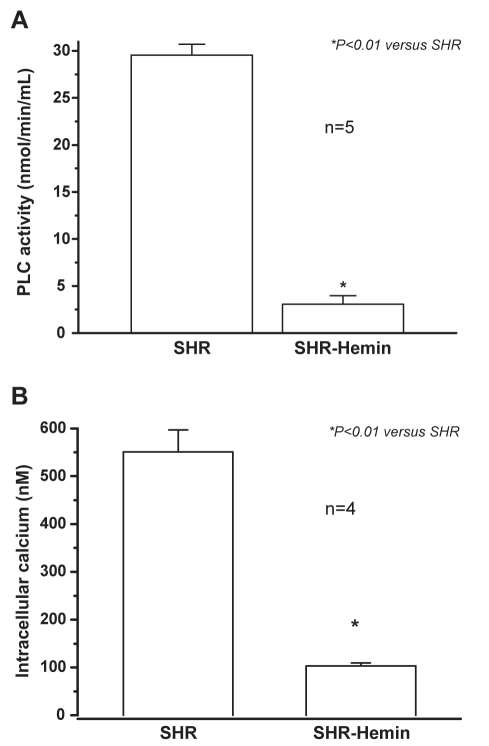

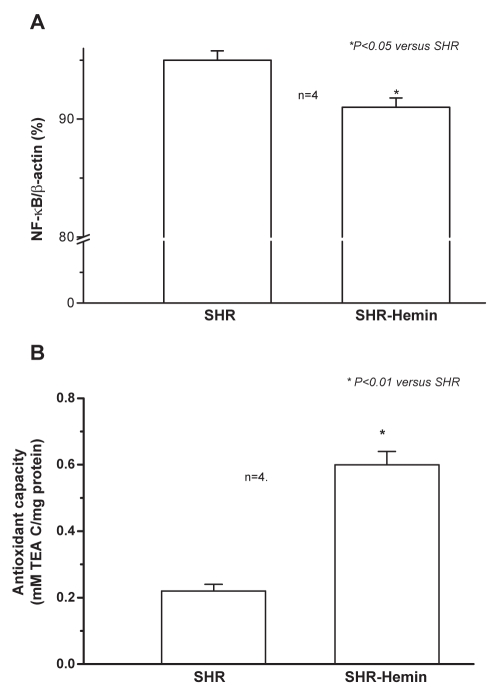

Because aldosterone is known to stimulate phospholipase C (PLC), the effect of hemin on PLC was examined. Hemin abated PLC activity (29.6±1.5 nmol/min/mL versus 3.1±0.9 nmol/min/mL; n=5, P<0.01) and this was accompanied by depleted levels of intracellular calcium (551±46 nM versus 103.2±6.3 nM; n=4, P<0.01) in the aorta of SHR. In contrast, enhanced heme oxygenase activity and elevated cyclic GMP levels (17.74±0.08 pmol/mg versus 30.4±2.3 pmol/mg protein; n=6, P<0.01) were detected in hemin-treated SHR. Additionally, hemin therapy also suppressed inflammatory and oxidative insults by significantly reducing nuclear factor kappa B messenger RNA expression while enhancing the total antioxidant capacity (0.22±0.02 Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEA C)/mg protein versus 0.60±0.04 TEA C/mg protein; n=4, P<0.01).

The concomitant depletion of aldosterone, PLC activity, intracellular calcium and the corresponding decline of inflammatory and oxidative insults may account for the antihypertensive effects of hemin.

Keywords: Aldosterone, Heme oxygenase, Hemin, Hypertension, Oxidative stress

The modulation of endogenously produced vasoactive signalling molecules, such as nitric oxide and carbon monoxide, to correct vascular dysfunction and lower blood pressure has been well acknowledged (1–7). In humans, carbon monoxide is formed at a rate of 16.4 μmol/h; up to 500 μmol can be produced daily (2). Despite the negative connotations associated with carbon monoxide, strong evidence suggests that carbon monoxide, at physiological concentrations (10 pM to 5 μM) (3–5), relaxes vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) through various mechanisms, including the activation of the soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) pathway, inhibition of cytochrome P450 and the opening of big calcium-activated K+ channels (8).

Given the availability of this array of carbon monoxide targets, it is envisaged that agents like heme oxygenase (HO) inducers – that increase endogenous carbon monoxide production – may potentiate vascular relaxation. Accordingly, the HO inducer hemin increases endogenous carbon monoxide production and reduces blood pressure (9). The HO-catalyzed breakdown of the heme moiety is a cytoprotective process that, besides generating cytoprotective products, reduces oxidative stress by depleting circulating levels of heme, a pro-oxidant (10). Among the cytoprotective products are carbon monoxide, bilirubin and biliverdin, all of which are known to scavenge reactive oxygen species, inhibit lipid peroxidation and suppress tissue inflammation (11–13). The iron that forms enhances the synthesis of ferritin, an antioxidant compound (14,15). Thus, with pharmacological modulation of carbon monoxide and other products within the HO pathway, the antihypertensive, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects would be increased. Carbon monoxide, bilirubin, biliverdin and ferritin constitute a protective tetrad against hypertension and secondarily induced damage resulting from elevated oxidative stress and inflammation.

The HO system may act in conjunction with other signalling pathways to lower blood pressure. These include the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Because spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) are an angiotensin-II-dependent model (16), and the HO isoform HO-1 abates angiotensin-II-induced hypertrophy (17) and hypertension (18), as well as aldosterone-elicited arterial injury (19), an intricate inter-relation between the HO and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone systems is envisaged. Besides its traditional role of promoting sodium retention (20), aldosterone causes oxidative stress by increasing 8-isoprostane levels (21), and similar to angiotensin-II, stimulates inflammation and fibrosis (22,23). On the other hand, aldosterone stimulates phospholipase C (PLC) to enhance diacylglycerol production in vascular SMCs (24,25). PLC catalyzes phosphoinositides to inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3), which mobilizes intracellular calcium stores, and diacylglycerol, which activates protein kinase C (26).

Thus, aldosterone triggers hypertension through various pathways. However, it is unknown whether upregulation of the HO system would abate plasma and tissue aldosterone levels in SHR. Similarly, the effect of the HO system on the PLC-IP3 pathway in SHR has not been reported. The multi-faceted interaction among the HO system, PLC-IP3 pathway and aldosterone may constitute an important mechanism for lowering blood pressure. Thus, the objective of the present study was to investigate novel mechanisms through which the HO system may be interacting with the aldosterone-signalling pathway to lower blood pressure in SHR.

METHODS

Animal preparation

The animal protocol was approved by the University of Saskatchewan Standing Committee on Animal Care and Supply. Male SHR, Wistar-Kyoto rats and Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Charles River Laboratories Inc, USA. They were housed at 21°C with 12 h light/dark cycles, fed with standard laboratory chow and given access to drinking water ad libitum. At the time of the experiments, all the animals were adults of 20 weeks of age. Hemin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA, and was dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH, titrated to pH 7.4 with 0.1 M HCl and diluted at a ratio of one part to 10 with phosphate buffer, as previously reported (27,28). Hemin was injected intraperitoneally daily at a dose of 15 mg/kg body weight (29) for three weeks. Systolic blood pressure was determined in conscious rats using a standard tail-cuff noninvasive blood pressure measurement system (Model 29-SSP, Harvard Apparatus, Canada). Blood pressure was measured daily for the entire three-week period. At the end of the injection scheme, the animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg body weight, intraperitoneally), sacrificed, and the aorta isolated, cleaned in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The phosphate-buffered saline contained 140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4 and 2 mM KH2PO4.

Determination of aldosterone

Aldosterone was quantified using an Enzyme Immunoassay Kit (Cayman Chemical, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (30). In brief, blood samples were collected in the presence of EDTA. Aldosterone was extracted from the plasma with methylene chloride and quantified by reading the absorbance at 412 nm.

Total RNA isolation and quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Liver tissues were homogenized in 0.5 mL TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen Corporation, USA) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Reverse transcription was carried out using a First Strand Complementary DNA Synthesis Kit (Novagen, USA) with 0.5 μg Oligo (dT)6 primer, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3 at 25°C), 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 50 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM each free deoxynucleotide triphosphate and 100 U of Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Reverse Transcriptase according to manufacturer specifications. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using a 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA) and iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA) containing 50 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 0.2 mM each free deoxynucleotide triphosphate, hot start enzyme iQ Taq DNA polymerase (25 units/mL) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA), 3 mM MgCl2, 1 nM SYBR Green and 10 nM fluorescein as a passive reference (31). Samples of complementary DNA of 1 μl each (run in triplicate) were used as a template with 3.2 pmol of primers for aldosterone synthase (5′ AGACTCTACCCTGTTGGTGGCTTT-3′ and 5′ TGAGGCATATAGCGCTCAGGTCTT-3′ ), nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) (5′ CATGCGTTTCCGTTACAAGTGCGA-3′ and 5′ TGGGTGCGTCTTAGTGGTATCTGT-3′ ) and β-actin (5′ TCATCACTATCGGCAATGAGCGGT-3′ and 5′ ACAGCACTGTGTTGGCATAGAGGT) in a final volume of 25 μL.

The thermal cycling program began with 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 56°C and 15 s at 72°C. PCR product melting points were determined by incubation at 65°C for 1 min, followed by a 1°C per min temperature increase over 30 min. The sequence of all primers used was confirmed by the National Research Council of Canada (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan).

HO activity assay

The HO activity was measured in aortic tissues as bilirubin production, using an established method (28). The amount of bilirubin in each sample was determined by a spectrophotometric assay at an absorbance of 560 nm, and expressed as nmol/mg protein/h.

PLC activity assay

The activity of PLC was estimated by means of a PLC assay kit (Cayman Chemical, USA). In this assay, the substrate arachidonyl thio-PC generates 5,5-dithiobis-2-dinitrobenzoic acid (DTNB), which is detected and quantified (32). Briefly, the aorta was homogenized in a solution composed of 50 mM HEPES and 1 mM EDTA at pH 7.4, and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant produced was treated in succession with thioetaramide-PC and bromoenol lactone to block secretory phospholipase A and calcium-independent phospholipase A (33,34), leaving only PLC in the samples.

The reaction was initiated by incubating samples with arachidonyl thio-PC at room temperature for 60 min. Subsequently, DTNB and EDTA were added to each sample and PLC activity was read at an absorbance of 414 nm. From the absorbance, PLC activity was calculated and expressed as nmol/min/mL. PLC positive control was supplied by the manufacturer to ascertain accuracy.

Measurement of cyclic GMP content

The concentration of cyclic (c)GMP was evaluated by an established method, as previously described (28). Briefly, the aorta was homogenized in 6% trichloroacetic acid at 4°C in the presence of 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine to inhibit phosphodiesterase activity and centrifuged at 2000 g for 15 min. The supernatant was recovered and washed three times with water-saturated diethyl ether. The upper ether layer was aspired and discarded while the aqueous layer containing cGMP was recovered and lyophilized. The dry extract was dissolved in 1 mL of cGMP assay buffer. The cGMP content was measured using the manufacturer’s protocol and expressed as pmol of cGMP per mg of protein.

Determination of intracellular calcium

The concentration of intracellular calcium was measured by an established method (35). Vascular SMCs from the aorta were isolated (36) and incubated with 4 μM fluo-3 acetoxymethyl ester and 0.08% Pluronic F-127 (BASF Corporation, USA) at 37°C for 30 min in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells were centrifuged, suspended in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium, and later in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution supplemented with 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin. Approximately 5×104 cells were transferred into each well of a 24-well plate. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 5 min, and the fluorescence of fluo-3 was measured for 10 min with filters for excitation at 485 nm and for emission at 527 nm, using a microplate fluorometer and Ascent software (Thermo Scientific, USA) (37,38). The intracellular calcium concentration was calculated with the following equation: [Ca2+]i=Kd([F−Fmin]/[Fmax−F]), where Kd for fluo-3 is 390 mM and F is the observed fluorescence intensity; Fmax the maximum fluorescence obtained after adding 0.5% Igepal CA-630 to permeabilize the cells and Fmin the minimum fluorescence obtained after adding 0.50 M ethylene glycol tetra-acetic acid to chelate free calcium.

Total antioxidant capacity assay

The total antioxidant capacity of control and hemin-treated SHR was evaluated using an Enzyme Immunoassay Kit (Cayman Chemical, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (39). This assay relies on the ability of the antioxidants in samples to inhibit the oxidation of 2,2′-azino-di-3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulphonate (ABTS) to ABTS plus metmyoglobin. In brief, liver samples were homogenized in the presence of protease inhibitors and treated with 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox), met-myoglobin and chromogen. The reaction is initiated by adding hydrogen peroxide and incubating the sample for 5 min. The absorbance is read at 750 nm, and expressed as Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity per mg protein.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM and analyzed using the Student’s t test or ANOVA in conjunction with Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. Group differences at the level of P<0.05 are statistically significant.

RESULTS

Hemin-reduced blood pressure in SHR but not in age-matched normotensive strains

The administration of hemin to adult SHR significantly lowered blood pressure from 210.1±1.3 mmHg to 127±1.3 mmHg; n=10, P<0.001 (Figure 1). Hemin therapy did not affect blood pressure of age-matched normotesive control Wistar-Kyoto rats (119±0.9 mmHg versus 120±0.2 mmHg, n=10) and Sprague-Dawley rats (123.6±1 mmHg versus 123.6±1.2 mmHg, n=10) (Figure 1). Similarly, the vehicle used to dissolve hemin had no effect on blood pressure (211.4±2.4 mmHg versus 214.6±2.1 mmHg, n=10) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of hemin therapy on blood pressure of adult spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR). The mean systolic blood pressure was calculated from six different measurements taken from each animal. Hemin therapy lowered blood pressure in adult SHR. Hemin therapy had no effect on age-matched normotensive Sprague-Dawley (SD) and Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) strains. The vehicle dissolving hemin had no effect on blood pressure. *P<0.01 versus untreated age-matched SHR; n=10

Hemin regimen upregulates HO activity and cGMP content

To elucidate the mechanisms of the antihypertensive effect of hemin, HO activity was assayed. HO activity encompasses the contribution from the three HO isoforms (HO-1, HO-2 and HO-3). HO activity in the aorta was significantly increased by hemin therapy (Figure 2A). Similarly, the cGMP content in the aorta was significantly upregulated (Figure 2B). Both HO activity and cGMP content were increased by 3.5- and 1.7-fold, respectively, by hemin (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hemin therapy and heme oxygenase (HO) activity, and cyclic (c) GMP content in the aorta of adult spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR). (A) Hemin therapy greatly enhanced HO activity in SHR. *P<0.01 versus untreated SHR; n=6. (B) Hemin robustly increased cGMP content in rat aortic tissues. *P<0.01 versus untreated SHR; n=6

PLC activity and intracellular calcium in vascular tissues with hemin

Hemin significantly reduced PLC activity in the aorta of adult SHR (Figure 3A). Importantly, a 10-fold depletion of PLC activity was registered in the aorta of SHR after hemin therapy. Correspondingly, the reduction in PLC activity was accompanied by a significant fall in intracellular calcium levels (Figure 3B). A fivefold reduction of intracellular calcium was observed in the aorta of hemin-treated SHR.

Figure 3.

The effect of hemin treatment on phospholipase C (PLC) activity and intracellular calcium levels in the aorta. (A) Hemin treatment greatly abolished the expression of PLC in the aorta of adult spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR). *P<0.01 versus untreated SHR; n=5. (B) The hemin regimen abolished intracellular calcium levels in the aorta of adult SHR. *P<0.01 versus untreated SHR; n=4

Hemin therapy suppresses aldosterone production

Hemin therapy suppressed aldosterone synthase messenger (m) RNA expression (Figure 4A). Correspondingly, the reduced aldosterone mRNA was accompanied by decreased levels of plasma aldosterone (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Hemin therapy, aldosterone messenger RNA and plasma aldosterone level. (A) Quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction shows that hemin therapy significantly decreased the messenger RNA expression of aldosterone synthase in the liver of adult spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR). *P<0.05 versus untreated SHR; n=4. (B) Hemin abated plasma aldosterone level in adult SHR. *P<0.05 versus untreated SHR; n=4

Hemin therapy abates inflammation and potentiates antioxidant capacity in SHR

Hemin therapy reduced the mRNA expression of the inflammatory transcription factor, NF-κB (Figure 5A). Similarly, hemin abated oxidative stress by enhancing the antioxidant capacity in SHR (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Hemin therapy, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) messenger (m) RNA and antioxidant capacity in adult spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR). (A) Quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction shows that hemin therapy significantly decreased the mRNA expression of NF-κB in the liver of adult SHR. *P<0.05 versus untreated SHR; n=4. (B) Hemin therapy greatly enhanced the antioxidant capacity in adult SHR. *P<0.01 versus untreated SHR; n=4. TEA C Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity

DISCUSSION

The administration of hemin to adult SHR with established hypertension resulted in normalization of blood pressure to the physiological level. The antihypertensive effect of hemin therapy stems from the potentiation of the HO system and its related signal transduction pathways. These include upregulation of HO activity and cGMP content (28). Both HO activity and cGMP content were enhanced by several folds after hemin therapy. Given that carbon monoxide is among the products of the HO-catalyzed degradation heme, and the activation of the sGC/cGMP pathway is an important mechanism by which carbon monoxide relaxes vascular tissues, the reduction of blood pressure in SHR may be due to increased carbon monoxide production after hemin therapy (2–5,8). However, it has to be clarified whether hemin directly affects the sGC/cGMP pathway.

Besides carbon monoxide, the HO system also generates bilirubin and biliverdin, which scavenge reactive oxygen species, inhibit lipid peroxidation and suppress tissue inflammation (11–13). The iron that forms enhances the synthesis of ferritin to confer an additional antioxidant effect (14,15). Thus, by breaking down the pro-oxidant, heme, the HO system suppresses oxidative injury (10). Accordingly, hemin therapy enhances the HO system and potentiates the protective tetrad of carbon monoxide, bilirubin, biliverdin and ferritin against secondarily induced damages such as oxidative stress and elevated inflammation due to hypertension. In this regard, aldosterone-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and fibrosis (21,22) will be abated by hemin therapy. Interestingly, our results indicate that hemin therapy greatly enhanced the total antioxidant capacity in SHR but abrogated NF-κB, an important pro-inflammatory and inflammatory transcription factor (40). Thus, the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effect of hemin therapy will combine with cytoprotective effects of the tetrad of carbon monoxide, bilirubin, biliverdin and ferritin to produce a potent antihypertensive axis.

Our results also indicate that hemin therapy significantly abolished aldosterone production. Thus, aldosterone-induced prohypertensive effects, such as sodium and water retention (20) and aldosterone-dependent activation of PLC activity (24,25), would be robustly reduced. Our findings are in agreement with recent reports in which upregulation of the HO system by another HO inducer, cobalt protoporphyrin, reduced aldosterone levels in the Goldblatt 2K1C hypertensive model (41). Several mechanisms may be implicated in the reduction of aldosterone by the HO system (42–45). The cGMP pathway has been suggested to inhibit aldosterone levels (42). Consistent with this notion are reports indicating that the disruption of the guanylyl cyclase-cGMP pathway in mice increased the production of aldosterone (43). Alternatively, carbon monoxide from the HO system may inhibit the heme prosthetic group, reducing the availability of cytochrome P450, an important enzyme for the synthesis of aldosterone (44,45). Therefore, these mechanisms, alongside the suppression of aldosterone synthase observed in the present study, would account for the reduction of aldosterone production.

Interestingly, hemin therapy also abated PLC activity and reduced intracellular calcium in the aorta. Both elevated PLC activity and intracellular calcium levels are important mechanisms that increase vascular contractility and thus increase blood pressure (26). Based on these results, the concomitant reduction of PLC activity, intracellular calcium and aldosterone would account for the decrease in blood pressure by hemin.

Although some studies report that heme is a pro-oxidant and high concentration of free heme is cytotoxic (10), upregulation of HO activity by hemin would accelerate the breakdown of circulating heme and limit cytotoxicity.

The present study indicates for the first time the direct effect of hemin on circulating aldosterone levels in SHR and provides novel links between the HO system and PLC activity that could be explored for novel therapeutic strategies for the management of hypertension.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Heart & Stroke Foundation of Saskatchewan, Canada. The authors are grateful for the technical assistance of Mr James Talbot.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dellabianca A, Sacchi M, Anselmi L, et al. Role of carbon monoxide in electrically induced no58*drenergic, non-cholinergic relaxations in the guinea-pig isolated whole trachea. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:220–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piantadosi CA. Biological chemistry of carbon monoxide. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4:259–70. doi: 10.1089/152308602753666316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook MN, Nakatsu K, Marks GS, et al. Heme oxygenase activity in the adult rat aorta and liver as measured by carbon monoxide formation. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1995;73:515–8. doi: 10.1139/y95-065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLaughlin BE, Chretien ML, Choi C, Brien JF, Nakatsu K, Marks GS. Potentiation of carbon monoxide-induced relaxation of rat aorta by YC-1 (3-[5′-hydroxymethyl-2′-furyl]-1-benzylindazole) Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2000;78:343–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leffler CW, Nasjletti A, Yu C, Johnson RA, Fedinec AL, Walker N. Carbon monoxide and cerebral microvascular tone in newborn pigs. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1641–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Vliet BN, Chafe LL. Maternal endothelial nitric oxide synthase genotype influences offspring blood pressure and activity in mice. Hypertension. 2007;49:556–62. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000257876.87284.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gamboa A, Shibao C, Diedrich A, et al. Contribution of endothelial nitric oxide to blood pressure in humans. Hypertension. 2007;49:170–7. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252425.06216.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang R, Wu L, Wang Z. The direct effect of carbon monoxide on KCa channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. Pflugers Arch. 1997;434:285–91. doi: 10.1007/s004240050398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horvath I, Donnelly LE, Kiss A, Paredi P, Kharitonov SA, Barnes PJ. Raised levels of exhaled carbon monoxide are associated with an increased expression of heme oxygenase-1 in airway macrophages in asthma: A new marker of oxidative stress. Thorax. 1998;53:668–72. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.8.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeney V, Balla J, Yachie A, et al. Pro-oxidant and cytotoxic effects of circulating heme. Blood. 2002;100:879–87. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baranano DE, Rao M, Ferris CD, Snyder SH. Biliverdin reductase: A major physiologic cytoprotectant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16093–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252626999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stocker R, Glazer AN, Ames BN. Antioxidant activity of albumin-bound bilirubin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5918–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stocker R, Yamamoto Y, McDonagh AF, Glazer AN, Ames BN. Bilirubin is an antioxidant of possible physiological importance. Science. 1987;235:1043–6. doi: 10.1126/science.3029864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balla G, Jacob HS, Balla J, et al. Ferritin: A cytoprotective antioxidant strategem of endothelium. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18148–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hintze KJ, Theil EC. DNA and mRNA elements with complementary responses to hemin, antioxidant inducers, and iron control ferritin-L expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15048–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505148102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lodwick D, Kaiser MA, Harris J, Cumin F, Vincent M, Samani NJ. Analysis of the role of angiotensinogen in spontaneous hypertension. Hypertension. 1995;25:1245–51. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.6.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu CM, Chen YH, Chiang MT, Chau LY. Heme oxygenase-1 inhibits angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy in vitro and in vivo. Circulation. 2004;110:309–16. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000135475.35758.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aizawa T, Ishizaka N, Taguchi J, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 is upregulated in the kidney of angiotensin II-induced hypertensive rats: Possible role in renoprotection. Hypertension. 2000;35:800–6. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.3.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ooi H, Ito M, Pimental D. Heme oxygenase protects against β-adrenergic receptor-stimulated apoptosis in cardiac cells. American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2004; New Orleans. November 7 to 10, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamamoto N, Yasue H, Mizuno Y, et al. Aldosterone is produced from ventricles in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;39:958–62. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000015905.27598.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iglarz M, Touyz RM, Viel EC, et al. Involvement of oxidative stress in the profibrotic action of aldosterone. Interaction wtih the renin-angiotension system. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:597–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun Y, Zhang J, Lu L, Chen SS, Quinn MT, Weber KT. Aldosterone-induced inflammation in the rat heart: Role of oxidative stress. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1773–81. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64454-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kai H, Mori T, Tokuda K, et al. Pressure overload-induced transient oxidative stress mediates perivascular inflammation and cardiac fibrosis through angiotensin II. Hypertens Res. 2006;29:711–8. doi: 10.1291/hypres.29.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christ M, Meyer C, Sippel K, Wehling M. Rapid aldosterone signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells: Involvement of phospholipase C, diacylglycerol and protein kinase C alpha. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;213:123–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andreis PG, Tortorella C, Malendowicz LK, Nussdorfer GG. Endothelins stimulate aldosterone secretion from dispersed rat adrenal zona glomerulosa cells, acting through ETB receptors coupled with the phospholipase C-dependent signaling pathway. Peptides. 2002;22:117–22. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan JC, Wu ZG, Kong XT, Zong RQ, Zhan LZ. Effect of CD40–CD40 ligand interaction on diacylglycerol-protein kinase C and inositol trisphosphate-Ca2+ signal transduction pathway in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Clin Chim Acta. 2003;337:133–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ndisang JF, Wu L, Wang X, Wang R. A nine-month antihypertensive effect of hemin opens a new horizon in the fight against hypertension. Experimental Biology Meeting 2005; San Diego. April 4 to 6, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ndisang JF, Wu L, Zhao W, Wang R. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 and stimulation of cGMP production by hemin in aortic tissues from hypertensive rats. Blood. 2003;101:3893–900. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ndisang JF, Zhao W, Wang R. Selective regulation of blood pressure by heme oxygenase-1 in hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;40:315–21. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000028488.71068.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rogerson FM, Fuller PJ. Mineralocorticoid action. Steroids. 2000;65:61–73. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(99)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katavetin P, Miyata T, Inagi R, et al. High glucose blunts vascular endothelial growth factor response to hypoxia via the oxidative stress-regulated hypoxia-inducible factor/hypoxia-responsible element pathway. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1405–13. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005090918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynolds LJ, Hughes LL, Yu L, Dennis EA. 1-Hexadecyl-2-arachidonoylthio-2-deoxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine as a substrate for the microtiterplate assay of human cytosolic phospholipase A 2. Anal Biochem. 1994;217:25–32. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plesniak LA, Boegeman SC, Segelke BW, Dennis EA. Interaction of phospholipase A2 with thioether amide containing phospholipid analogues. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5009–16. doi: 10.1021/bi00070a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balsinde J, Bianco ID, Ackermann EJ, Conde-Frieboes K, Dennis EA. Inhibition of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 prevents arachidonic acid incorporation and phospholipid remodeling in P388D1 macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8527–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ndisang JF, Gai P, Berni L. Modulation of the immunological response of guinea pig mast cells by carbon monoxide. Immunopharmacology. 1999;43:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao W, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang R. The vasorelaxant effect of H(2)S as a novel endogenous gaseous K(ATP)channel opener. EMBO J. 2001;20:6008–16. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki Y, Yoshimaru T, Matsui T, et al. Fc epsilon RI signaling of mast cells activates intracellular production of hydrogen peroxide: Role in the regulation of calcium signals. J Immunol. 2003;171:6119–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yue H, Uzui H, Shimizu H. Different effects of calcium channel blockers on matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression in cultured rat cardiac fibroblasts. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44:223–30. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200408000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koracevic D, Koracevic G, Djordjevic V, Andrejevic S, Cosic V. Method for the measurement of antioxidant activity in human fluids. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:356–61. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.5.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sasaki T, Takahashi T, Maeshima K, et al. Heme arginate pretreatment attenuates pulmonary NF-kappaB and AP-1 activation induced by hemorrhagic shock via heme oxygenase-1 induction. Med Chem. 2006;2:271–4. doi: 10.2174/157340606776930781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Botros FT, Schwartzman ML, Stier CT, Jr, Goodman AI, Abraham NG. Increase in heme oxygenase-1 levels ameliorates renovascular hypertension. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2745–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oda S, Sano T, Morishita Y, Matsuda Y. Pharmacological profile of HS-142–1, a novel nonpeptide atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) antagonist of microbial origin. II. Restoration by HS-142–1 of ANP-induced inhibition of aldosterone production in adrenal glomerulosa cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;263:241–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao D, Vellaichamy E, Somanna NK, Pandey KN. Guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor-A gene disruption causes increased adrenal angiotensin II and aldosterone levels. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F121–7. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00478.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abraham NG, Drummond GS, Lutton JD, Kappas A. The biological significance and physiological role of heme oxygenase. Cell Physiol Biochem. 1996;6:129–168. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pascoe L, Curnow KM, Slutsker L, et al. Glucocorticoid-suppressible hyperaldosteronism results from hybrid genes created by unequal crossovers between CYP11B1 and CYP11B2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8327–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]