Abstract

Zwitterionic polysaccharide antigens (ZPSs) were recently shown to activate T cells in a class II major histocompatibility complex (MHCII)-dependent fashion requiring antigen presenting cell (APC)-mediated oxidative processing although little is known about the mechanism or affinity of carbohydrate presentation (Cobb BA, Wang Q, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. 2004. Polysaccharide processing and presentation by the MHCII pathway. Cell. 117:677–687). A recent study showed that the helical conformation of ZPSs (Wang Y, Kalka-Moll WM, Roehrl MH, Kasper DL. 2000. Structural basis of the abscess-modulating polysaccharide A2 from Bacteroides fragilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 97:13478–13483; Choi YH, Roehrl MH, Kasper DL, Wang JY. 2002. A unique structural pattern shared by T-cell-activating and abscess-regulating zwitterionic polysaccharides. Biochemistry. 41:15144–15151) is closely linked with immunogenic activity (Tzianabos AO, Onderdonk AB, Rosner B, Cisneros RL, Kasper DL. 1993. Structural features of polysaccharides that induce intra-abdominal abscesses. Science. 262:416–419) and is stabilized by a zwitterionic charge motif (Kreisman LS, Friedman JH, Neaga A, Cobb BA. 2007. Structure and function relations with a T-cell-activating polysaccharide antigen using circular dichroism. Glycobiology. 17:46–55), suggesting a strong carbohydrate structure–function relationship. In this study, we show that PSA, the ZPS from Bacteroides fragilis, associates with MHCII at high affinity and 1:1 stoichiometry through a mechanism mirroring peptide presentation. Interestingly, PSA binding was mutually exclusive with common MHCII antigens and showed significant allelic differences in binding affinity. The antigen exchange factor HLA-DM that catalyzes peptide antigen association with MHCII also increased the rate of ZPS association and was required for APC presentation and ZPS-mediated T cell activation. Finally, the zwitterionic nature of these antigens was required only for MHCII binding, and not endocytosis, processing, or vesicular trafficking to MHCII-containing vesicles. This report is the first quantitative analysis of the binding mechanism of carbohydrate antigens with MHCII and leads to a novel model for nontraditional MHCII antigen presentation during bacterial infections.

Keywords: antigen binding, antigen processing, carbohydrate, MHCII presentation

Introduction

The cornerstone of adaptive immunity is the specific molecular recognition of foreign molecules by immune system receptors. For conventional exogenous protein antigens, this is achieved through proteolytic processing to short peptides, class II major histocompatibility complex (MHCII) binding (Jardetzky et al. 1990; Smith et al. 1998), and cell surface presentation (Abbas et al. 2000). These peptides associate with MHCII in a groove that accommodates a single antigen and is formed by two parallel α-helices sitting on top of a β-sheet. Peptides are linear in structure while bound and are characterized by relatively low affinities, usually approximately 1 μM (Abbas et al. 2000) with very slow kon and koff rates, facilitating the long complex half life required for MHCII-peptide complexes presented at the cell surface. For in vitro binding studies, affinity can be measured with extended incubation times (>24 h) to overcome the slow rates; however, the intracellular loading of MHCII is dependent upon HLA-DM (DM) which increases the rate of association through promoting the exit of self-peptides that associate with MHCII during synthesis in the ER (Denzin and Cresswell 1995). DM functions at a pH optimum between 4.5 and 6.0, correlating well with the acidic environment of the MHCII compartment where peptide loading occurs. Furthermore, hydrogen bonds between the peptide backbone and hydrophobic interactions with peptide side chains dominate peptide–MHCII interactions. In contrast, superantigens are MHCII-dependent molecules that are presented without processing as an intact protein bound outside of the normal peptide binding domain, usually to MHCII molecules already loaded with a peptide (Jardetzky et al. 1994; Hogan et al. 2001). While both of these mechanisms are well understood from biochemical and structural interrogation, essentially nothing is known about the binding mechanism for carbohydrate antigens known to activate immune responses via MHCII-dependent presentation (Cobb et al. 2004).

Until recently, MHCII was only known to present peptide or superantigens; thus, the discovery that the MHCII pathway is also responsible for carbohydrate antigen presentation and ultimately T cell recognition alters the fundamental model of MHCII-antigen binding. Zwitterionic polysaccharide antigen (ZPS) molecules require processing to a low molecular weight form, much like conventional peptide antigens, only the mechanism for cleavage is nitric oxide dependent (Cobb et al. 2004). The presented form ranges from 3 to 15 kDa (Cobb et al. 2004), which is larger than most peptides that are usually between 13 and 18 amino acids in length (i.e., <2 kDa). In T cell assays, antibodies against the MHCII allele family HLA-DR blocked ZPS-mediated T cell activation while neither HLA-DP nor HLA-DQ antibodies had an effect (Kalka-Moll et al. 2002). These data, although limited by the number of specific alleles tested, suggest that ZPS binding and presentation is restricted to the HLA-DR family. In vitro binding assays and co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments have confirmed a direct MHCII–ZPS interaction that seems to be affected by the presence of DM (Cobb et al. 2004) although these assays were limited to the affirmation of binding rather than elucidating the biochemical binding mechanism or the functional role of DM.

All known ZPS molecules have in common a zwitterionic charge motif within the repeating unit. These include the capsular polysaccharides Sp1 from type I Streptococcus pneumoniae (Tzianabos et al. 1993; Stingele et al. 2004), CP from types 5 and 8 Staphylococcus aureus (Tzianabos et al. 2001), and PSA from Bacteroides fragilis (Tzianabos et al. 1993; Brubaker et al. 1999). The primary structure of PSA consists of a tetrasaccharide repeating unit (Figure 1) containing 4,6-pyruvate attached to a d-galactopyranose, 2,4-dideoxy-4-amino-d-FucNAc, d-N-acetylgalactosamine, and d-galactofuranose (Baumann et al. 1992). Within this repeating unit, one positively charge free amine and one negatively charged carboxylate are present. Interestingly, NMR solution structures of PSA and Sp1 show a stable, extended right-handed helix with three repeating units per helical turn and a pitch of 20 Å (Wang et al. 2000; Choi et al. 2002). The large negatively charged grooves within the helix are 10 Å wide, 10 Å long, and 5 Å deep, with the outer surfaces strongly positive. In silico modeling further suggests that these large negatively charged carbohydrate grooves could envelop a protein α-helix in a manner analogous to α-helix binding to the major groove of DNA, providing one plausible structure-based model for carbohydrate–protein interactions.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of PSA from B. fragilis. (A) Labeling reactions with hydrazide-linked biotin and AlexaFluor594 were targeted to the periodate-activated side chain galactofuranose. Radiolabeling was accomplished by tritiated borohydride reduction of periodate-created aldehydes. (B) Positive free amines were neutralized through acetylation by acetic anhydride. (C) Negative carboxylates were neutralized by carbodiimide and borohydride reduction.

More recently, circular dichroism has been used to monitor the helical content of PSA to better understand the role of conformation in antigenicity (Kreisman et al. 2007). The PSA helix is remarkably stable to temperature and yet is sensitive to nonpolar solvents and polymer length. It was shown that the inclusion of 20% acetonitrile increases the molar ellipticity to the same extent seen in the α-helix-rich protein myoglobin. Since three repeating units (∼3 kDa) are required to make a full helical turn, it is also not surprising that PSA molecules below 3 kDa are in a random coil conformation that lacks the ability to associate with HLA-DR1. Interestingly, PSA fragments between 3 and 10 kDa that maintain a helical conformation seem to bind better than larger ones (Kreisman et al. 2007) although the affinity has not yet been determined, and this agrees with an earlier study that demonstrated ZPSs smaller than 5 kDa fail to activate T cells. Collectively, these data indicate that carbohydrate processing is required to generate fragments between 3 and 10 kDa that maintain helical conformation to facilitate MHCII binding and presentation.

Finally, the zwitterionic motif is also known to be critical for antigenic function of ZPSs. It was demonstrated nearly 15 years ago that the removal of either a positive or negative group results in an immunologically inert carbohydrate (Tzianabos et al. 1993). In fact, the introduction of a zwitterionic motif into a normally nonzwitterionic polysaccharide converts it to a T cell-activating antigen. To extend those findings, CD has been used to show that this charge motif is required for the stability of the helical conformation of PSA and leads to less binding to MHCII (Kreisman et al. 2007), pointing to key electrostatic contributions to the structure and function of ZPS antigens. Together, these observations point to a relationship between ZPS helical content, activity, electrostatic interactions and MHCII-mediated presentation.

Although direct interactions between HLA-DR2 (DR2) (Cobb et al. 2004), HLA-DR1 (DR1) (Kreisman et al. 2007), and PSA have been demonstrated, the binding affinity, stoichiometry, types of bonds that dominate the interaction, and allelic specificity remain completely undetermined. DM has been shown to influence the binding of PSA to DR2 (Cobb et al. 2004), but we have no knowledge of the carbohydrate-specific mechanism of DM action, if it influences MHCII presentation in live cells, or if DM is required for T cell activation. Finally, no information is available on how ZPS binding to MHCII relates to peptide and superantigen association. In this report, we demonstrate high affinity interactions between the DR family and preprocessed PSA. Our results indicate that the interaction is one to one and shows allelic selectivity between DR1, DR2, and DR4 as measured by dissociation constants (Kd). Binding is sensitive to ionic strength and pH, indicating that both electrostatic bonds and ionizable groups play a central role in PSA presentation. We also show competitive binding between PSA, peptides, and superantigens, suggesting that the binding domains for these antigens overlap. DM is shown to be critically important for cellular surface presentation of PSA and in vivo T cell activation due to its ability to increase the rate of binding. Finally, we show that the loss of the alternating charge motif results in the ablation of in vitro and in vivo MHCII binding, whereas this motif does not significantly affect uptake, vesicular trafficking, or processing. These results are the first biochemical characterization of carbohydrate antigen presentation by MHCII proteins and demonstrate the requirement for acidic pH, self-peptide release, and catalysis by DM to achieve surface presentation and T cell recognition.

Results

MHCII–PSA binding affinity and stoichiometry

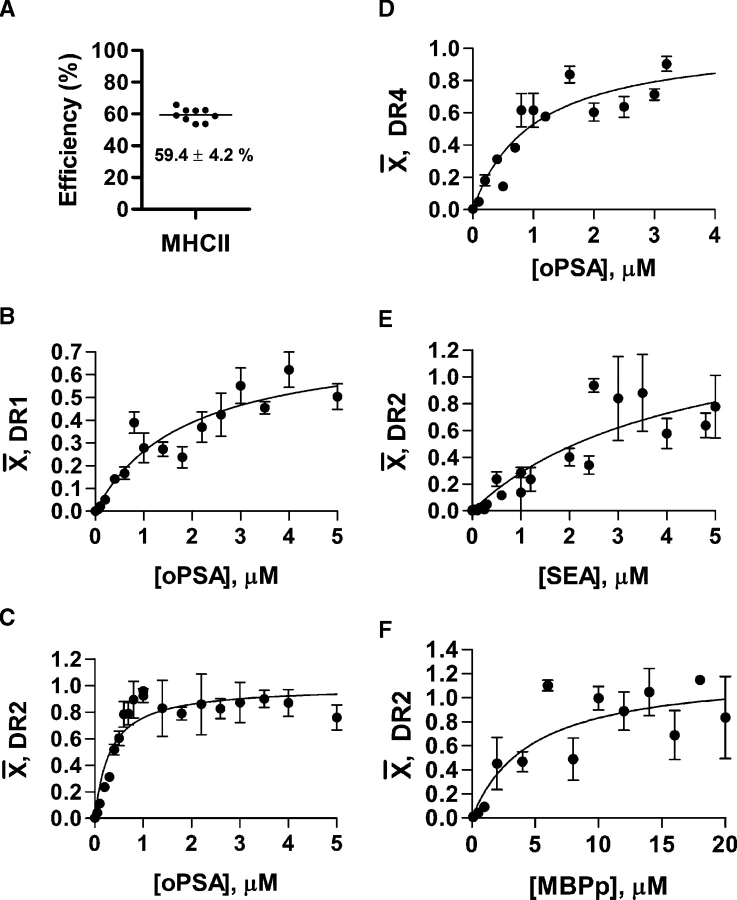

The MHCII affinity, stoichiometry, and specificity for the model zwitterionic polysaccharide antigen PSA was carried out using in vitro preprocessed (average MW = 15 kDa) and biotinylated (Figure 1A) PSA in equilibrium binding experiments with previously described recombinant MHCII alleles (Table I) (Gauthier et al. 1998; Stratikos et al. 2002; Day et al. 2003). The DP and DQ proteins were previously shown not to mediate T cell activation with ZPSs (Kalka-Moll et al. 2002); thus, we focused this study on the DR family. First, the amount of DR protein immobilized on the plates following conjugation was determined spectroscopically to facilitate the calculation of the degree of binding ( ); the moles of bound carbohydrate per mole of immobilized MHCII at each data point. We found that 59.4 ± 4.2% of the input protein conjugated to the well (Figure 2A).

); the moles of bound carbohydrate per mole of immobilized MHCII at each data point. We found that 59.4 ± 4.2% of the input protein conjugated to the well (Figure 2A).

Table I.

| HLA-DR constructs | ||

|---|---|---|

| Construct | Allele haplotype | Encoded |

| name (reference) | peptide | |

| HLA-DR1 (20) | DRA*0101, DRB1*0101 | None |

| HLA-DR2 (19) | DRA*0101, DRB1*1501 | MBPp |

| (residues 85–99) | ||

| HLA-DR4 (22) | DRA*0101, DRB1*0401 | CLIP |

Fig. 2.

Analysis of MHCII antigen binding. (A) The plate capture efficiency for immobilization of DR protein was measured spectroscopically (n = 9) to facilitate the calculation of binding stoichiometries. 59.4% of the DR incubated in the Immulon 2 HB wells became immobilized, with 40.6% of the protein remaining in the supernatant as measured by absorbance at 280 nm. In subsequent binding assays, 0.1 μg DR construct was coated into wells (0.0594 μg actually immobilized) at 37°C and pH 5.0, except SEA (at pH 7.3). The degree of binding ( ) is the moles ligand bound per mole of MHCII; thus, the Bmax represents the stoichiometry. All data points represent the average of at least four replicates. PSA saturably binds to DR1 (panel B; Kd = 1.9 ± 0.4 μM; Bmax = 0.8 ± 0.08), DR2 (panel C; Kd = 0.31 ± 0.05 μM; Bmax = 1.0 ± 0.04), and DR4 (panel D; Kd = 1.0 ± 0.3 μM; Bmax = 1.0 ± 0.1). Control binding with SEA (E) and MBPp (F) with DR2 show Kd values of 4.7 ± 2.0 μM and 4.3 ± 2.6 μM with Bmax values of 1.5 ± 0.5 and 1.2 ± 0.2, respectively.

) is the moles ligand bound per mole of MHCII; thus, the Bmax represents the stoichiometry. All data points represent the average of at least four replicates. PSA saturably binds to DR1 (panel B; Kd = 1.9 ± 0.4 μM; Bmax = 0.8 ± 0.08), DR2 (panel C; Kd = 0.31 ± 0.05 μM; Bmax = 1.0 ± 0.04), and DR4 (panel D; Kd = 1.0 ± 0.3 μM; Bmax = 1.0 ± 0.1). Control binding with SEA (E) and MBPp (F) with DR2 show Kd values of 4.7 ± 2.0 μM and 4.3 ± 2.6 μM with Bmax values of 1.5 ± 0.5 and 1.2 ± 0.2, respectively.

For the three HLA-DR alleles,  was measured with varying amounts of ligand, and then plotted as a function of ligand concentration to calculate the maximal degree of binding (i.e., stoichiometry; Bmax) and affinity (Kd) of interaction. We found that PSA has a Kd of 1.9 ± 0.4 μM and a Bmax of 0.8 ± 0.08 with DR1 (Figure 2B). With DR2 (Kd = 0.31 ± 0.05 μM; Figure 2C), the affinity is 6-fold tighter than DR1 and 3-fold tighter than DR4 (Kd = 1.0 ± 0.3 μM, Figure 2D), demonstrating allelic selectivity. Like DR1, both DR2 and DR4 binding show 1:1 stoichiometry (Bmax = 1.0 ± 0.04 and 1.0 ± 0.1, respectively). As controls, the superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin A (SEA; Figure 2E) and myelin basic protein peptide (MBPp; residues 85–99; Figure 2F) were used in DR2 binding curves, both showing μM affinity (Kd = 4.7 ± 2.0 μM and 4.3 ± 2.6 μM, respectively). MBPp bound with the expected 1:1 stoichiometry (Bmax = 1.2 ± 0.2) while SEA shows a stoichiometry between 1 and 2 to 1 (Bmax = 1.5 ± 0.5), likely reflecting the ability of SEA to simultaneously bind at two sites on DR. Since it is well known that MBPp binds at 1:1 mole ratio with all MHCII proteins, the unity stoichiometry measured here for MBPp binding confirms the immobilization efficiency of DR and demonstrates that essentially all DR molecules are accessible to antigen binding in these assays (Nag et al. 1994; Kalandadze et al. 1996; Ryan et al. 2004).

was measured with varying amounts of ligand, and then plotted as a function of ligand concentration to calculate the maximal degree of binding (i.e., stoichiometry; Bmax) and affinity (Kd) of interaction. We found that PSA has a Kd of 1.9 ± 0.4 μM and a Bmax of 0.8 ± 0.08 with DR1 (Figure 2B). With DR2 (Kd = 0.31 ± 0.05 μM; Figure 2C), the affinity is 6-fold tighter than DR1 and 3-fold tighter than DR4 (Kd = 1.0 ± 0.3 μM, Figure 2D), demonstrating allelic selectivity. Like DR1, both DR2 and DR4 binding show 1:1 stoichiometry (Bmax = 1.0 ± 0.04 and 1.0 ± 0.1, respectively). As controls, the superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin A (SEA; Figure 2E) and myelin basic protein peptide (MBPp; residues 85–99; Figure 2F) were used in DR2 binding curves, both showing μM affinity (Kd = 4.7 ± 2.0 μM and 4.3 ± 2.6 μM, respectively). MBPp bound with the expected 1:1 stoichiometry (Bmax = 1.2 ± 0.2) while SEA shows a stoichiometry between 1 and 2 to 1 (Bmax = 1.5 ± 0.5), likely reflecting the ability of SEA to simultaneously bind at two sites on DR. Since it is well known that MBPp binds at 1:1 mole ratio with all MHCII proteins, the unity stoichiometry measured here for MBPp binding confirms the immobilization efficiency of DR and demonstrates that essentially all DR molecules are accessible to antigen binding in these assays (Nag et al. 1994; Kalandadze et al. 1996; Ryan et al. 2004).

Salt and pH effects on binding

One of the hallmarks of carbohydrates that activate T cells is the highly charged zwitterionic motif. It is therefore reasonable to hypothesize that electrostatic interactions may play an important role in MHCII presentation. Using varying concentrations of salt to inhibit these potential electrostatic interactions between MHCII and antigens, we found that neither MBP peptide nor superantigen binding was significantly affected by the addition of NaCl (Figure 3A). In contrast, the addition of various NaCl concentrations to block electrostatic bonds inhibited PSA binding by approximately 60% (Figure 3B), showing that critical electrostatic bonds are formed between MHCII and PSA during binding and presentation. To confirm that high salt conditions do not lead to alterations in PSA itself, sizing analysis on a Superose 12 column was performed. No changes in size or aggregation state of PSA were seen as a result of low or high ionic strength conditions (Figure 3C).

Fig. 3.

Salt effects on in vitro MHCII binding. 0.1 μg of DR was used in all of the assays. (A) 4 μM MBPp and 4 μM SEA binding to DR2 with zero (open) or 1 M NaCl (shaded) added to the reaction buffer, normalized to the no salt added data with each data point representing the average of three replicates. Only very small effects are observed. (B) 1 μM PSA binding to DR2 with 0, 0.5, or 1.0 M NaCl added with each data point representing the average of eight replicates, showing significant loss of binding as a result of high ionic strength conditions. (C) Size exclusion elution profiles of PSA ligand used in these assays in high and low ionic strength buffer using a Superose 12 column, confirming that changes in binding are not due to changes in size or aggregation state under the specified ionic conditions.

Within antigen presenting cells (APCs), the acidification of endo/lysosomes is a characteristic of the MHCII endocytic pathway. In fact, carbohydrate-mediated T cell activation can be inhibited by the addition of an acidification blocker, such as bafilomycin A1 (Stephen et al. 2005), and sensitivity to pH in binding has already been observed previously (Cobb et al. 2004). In this study, we performed DR2 binding assays at pH 7.3 and 5.0 specifically to compare the pH dependency of peptide, superantigen, and carbohydrate presentation by MHCII. We found that PSA (Figure 4B) shows a strong preference for binding in acidic conditions (5-fold change) with far greater sensitivity to pH than either MBPp (2-fold; Figure 4A) or SEA (less than 2-fold; Figure 4A). These results for MBPp are similar to those previously reported (Mukku et al. 1995), showing a 2-fold preference for binding at neutral pH. Finally, to confirm that near neutral and acidic pH conditions do not lead to alterations in PSA independently from MHCII binding, sizing analysis on a Superose 12 column was performed. No significant difference in size or aggregation state of PSA was seen at pH 7.2 and pH 5.0 (Figure 4C). These data point to a novel mode of MHCII-dependent antigen presentation in which cellular entry into acidic endosomal compartments and the presence of electrostatic interactions play dominant roles.

Fig. 4.

pH effects on in vitro MHCII binding. (A) Peptide and superantigen binding to DR2 at pH 5.0 (open) compared to pH 7.3 (shaded), normalized to pH 7.3 data, demonstrating modest alterations in binding (2-fold with peptide). (B) PSA binding to DR2 at pH 5.0 and 7.3, showing a profound increase in binding at acidic pH (5-fold), showing that binding of PSA to MHCII is strongly dependent upon an acid environment. (C) Size exclusion elution profiles of PSA ligand used in these assays at neutral and acidic pH using a Superose 12 column, confirming that changes in binding are not due to changes in size or aggregation state at the specified pH value.

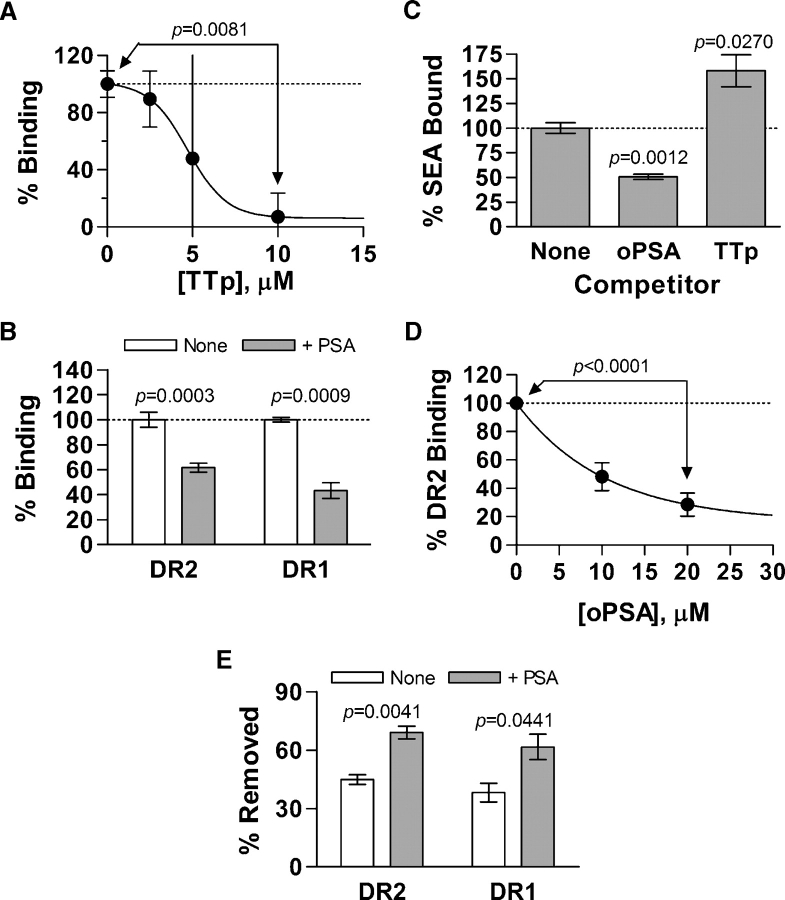

Binding competition

MHCII proteins are associated with the self-peptide CLIP within the vesicular compartments of APCs. For antigenic peptides to achieve presentation, DM catalyzes the competitive binding and exchange of self and foreign peptides into the canonical peptide-binding groove of MHCII. As such, only a single peptide may be bound to MHCII at any one time. In contrast, superantigens tend to bind to peptide-loaded MHCII proteins at the cell surface, forming critical contacts outside of the normal peptide-binding groove (Hogan et al. 2001). In order to demonstrate both the exclusivity of PSA binding and to provide a framework of potential contacts made within and outside the peptide groove of MHCII, we performed competitive binding experiments. First, titrations of nonlabeled tetanus toxin peptide (TTp; Figure 5A) (Boitel et al. 1992) and 10 kDa dextran (not shown) competitors were collected with a static concentration of preprocessed biotin-PSA (1 μM) and DR2 (0.1 μg) at pH 5.0. We found that nonzwitterionic carbohydrates like dextran failed to inhibit PSA interactions, yet TTp efficiently and completely competed for MHCII binding (Figure 5A). Similar results were obtained with a TTp competition of PSA for DR1 binding (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

MHCII competitive binding assays (all normalized to no competitor), with each data point representing at least three replicates. (A) Titration of 1 μM PSA binding competition with a TTp competitor in DR2 binding at pH 5.0, showing complete inhibition of PSA binding at high peptide concentrations. (B) 4 μM MBPp binding (open) is competed with 20 μM PSA (shaded) using DR2 and DR1 at pH 7.3. (C) 4 μM SEA binding to DR1 competes with 20 μM PSA but is enhanced by 20 μM peptide at pH 7.3. (D) 4 μM SEA binding to DR2 with varying concentrations of PSA competitor, showing dose-dependence. (E) MBPp from 0.2 μg of MBPp-saturated DR2 and DR1 was displaced with the addition of a buffer alone (open) but more efficiently with 50 μM PSA (shaded).

In other experiments, biotinylated MBPp and SEA superantigen were monitored for binding to DR2 at pH 7.3 using nonlabeled preprocessed PSA as a competitive inhibitor. At 10-fold molar excess over MBPp, PSA competed with peptide binding to a similar extent as previous peptide-to-peptide competition studies (Nag et al. 1996) although to a lesser degree as seen in Figure 5A. This is likely due to the suboptimal binding of PSA to DR molecules at pH 7.3 (see Figure 4B). Interestingly, PSA also inhibited SEA binding to DR1 by 2-fold at 10-fold molar excess, while TTp enhanced SEA binding (Figure 5C). This agrees with previous reports showing enhanced superantigen binding with varying peptides bound to MHCII grooves. In order to extend these findings, two concentrations of PSA were used in competitive binding assays with DR2 and SEA. We found that at least 80% of SEA binding to MHCII can be blocked by PSA at high concentrations (Figure 5D). Finally, peptide displacement assays were performed by incubating biotinylated MBPp-saturated DR molecules with and without nonlabeled PSA (Figure 5E). We found that with buffer alone, approximately 50% of the bound peptide is lost from the protein after 24 h incubation through the re-establishment of equilibrium; however, the addition of PSA increases the amount of peptide lost from the MHCII protein to approximately 75%. These observations are likely the result of PSA forming contacts inside and outside the peptide-binding groove, rendering PSA binding mutually exclusive (i.e., PSA cannot bind while MHCII is bound to either superantigen or peptide) with all other antigens through the steric hindrance of the necessary contacts.

The role of HLA-DM

We showed previously that the exchange factor DM, which facilitates competitive peptide binding on MHCII, plays an uncharacterized role in PSA presentation (Cobb et al. 2004). Since PSA competitively binds to MHCII, we analyzed the mechanistic role for DM in carbohydrate presentation. PSA time course binding experiments were conducted in the presence and absence of equimolar quantities of DM to DR2 (Figure 6A). Without DM, the time to reach half completion (T½) is 107.6 ± 16.4 min, whereas the T½ is 33.3 ± 5.0 min with DM, demonstrating a 3-fold increase in the binding exchange rate in the presence of DM, which is consistent with previous findings using peptides (Busch et al. 2002). This observation was extended using wild-type (wt) and DM-ablated mice (DM−/−). In ex vivo presentation assays, MHCII complexes were immunoprecipitated from wt or DM−/− primary splenocytes incubated with radiolabeled PSA. We found that the amount of radioactive carbohydrate coprecipitating with MHCII was reduced significantly in the DM−/− animals (Figure 6B). In addition, in vivo T cell activation studies in these animals, as measured by abscess induction, were impaired by approximately 50% in DM−/− animals compared to wt (Figure 6C). These data collectively demonstrate that DM functions to catalyze PSA binding and that this is required for the efficient cellular presentation of PSA to T cells.

Fig. 6.

DM effects on binding. (A) 1.0 μM PSA binding time course with 0.1 μg DR2 in the presence (filled) or absence (open) of equimolar DM. Time to reach half completion (dotted line, T½) in the absence of DM is 107.6 ± 16.4 min, but the rate of binding is increased 3-fold to T½ = 33.3 ± 5.0 min with DM. Each data point represents the average of three replicates. (B) PSA co-IP with an anti-MHCII antibody from wild-type and DM−/− splenocytes. DM−/− cells fail to present significant quantities of PSA in MHCII. Each data point represents the average of two independent experiments with 12 mice in each group per experiment. (C) PSA-induced abscess formation (a measure of in vivo T cell activation by PSA) in either wild type or DM−/− animals, showing a 2-fold decrease in abscess formation in the animals lacking DM. The numbers above each bar represent the number of mice with abscesses compared to total.

The role of charges in PSA presentation

In previous studies, it was demonstrated that the loss of the zwitterionic charge motif on these antigens by deamination, N-acetylation, or carbodiimide reduction results in the ablation of T cell stimulatory activity (Tzianabos et al. 1993); however, it was unclear whether these charged groups were necessary because of a failure in endocytosis, processing, or MHCII binding. To understand the mechanistic role of the zwitterionic motif on the ability of PSA to be presented by MHCII, charge-modified preprocessed PSA molecules (mod-PSA; Figure 1B and C) were created by N-acetylation to remove the positive charges (NAc-PSA), carbodiimide reduction to remove the negative charges (Carbo-PSA) or both to generate a neutral antigen (NAc-Carbo-PSA).

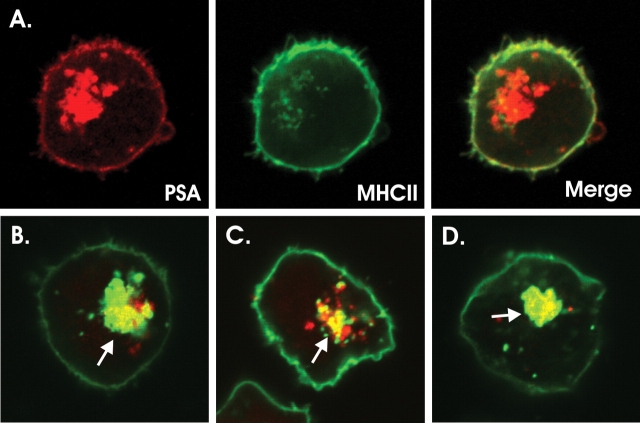

First, confocal microscopy studies were performed with fluorescently conjugated native and mod-PSA antigens in APCs to determine if PSA endocytosis and vesicular localization rely upon charge-dependent interactions with host molecules. Native PSA colocalized with MHCII inside and on the surface of human Raji B cells (Figure 7A), whereas all of the mod-PSA antigens colocalized with MHCII only within internal vesicles (Figure 7B–D). These data show that APC internalization and trafficking of PSA are independent of the charge motif, yet the charges are critically important for surface localization, potentially due to a failure to be processed, to bind to MHCII, or both.

Fig. 7.

Charge effects on cellular localization of PSA antigens (red) and MHCII (green) in murine MΦs and Raji cells by confocal microscopy. Surface colocalized PSA and MHCII (yellow) are indicated by arrow heads and internal colocalization (yellow) by arrows. (A) The native PSA images, shown as separate channels to illustrate the weakly stained MHCII positive vesicles obscured in the overlay (right) by the strong red signal of the polysaccharide. (B) NAc-PSA. (C) Carbo-PSA. (D) NAc-Carbo-PSA. In agreement with the in vitro binding experiments, none of the mod-PSA samples are presented by APCs at the cell surface, though all can enter vesicular compartments that contain MHCII protein (arrows).

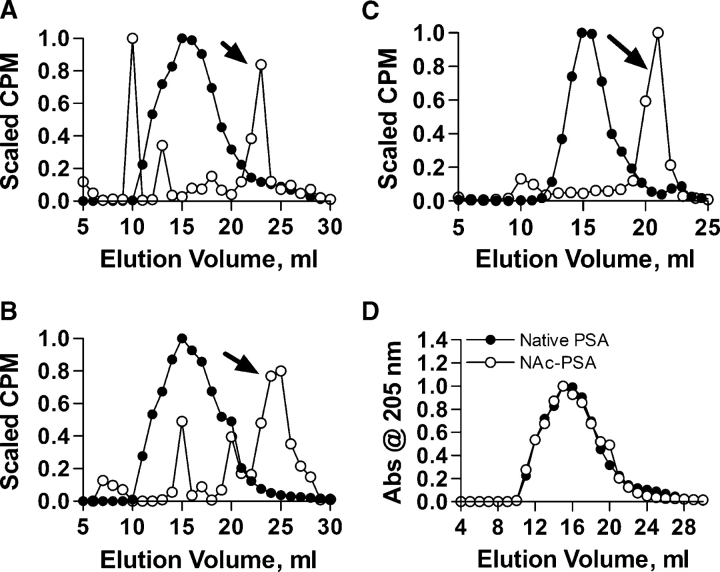

In order to determine if mod-PSA antigens are efficiently processed once inside the APCs, radiolabeled native and mod-PSA antigens were incubated with Raji B cells overnight and the endosomal fraction of the cells was isolated and analyzed by chromatography as previously described (Cobb et al. 2004). Native PSA, NAc-PSA, and an anionic polysaccharide control (type III group B streptococcal capsule) were present inside the endosomal fraction in a reduced molecular weight form (open circles; Figure 8A–C, arrows) compared to the input polysaccharide (filled circles). An overlay of the elution profiles shown in panels A and B for the input PSA with and without charge modification is shown in Figure 8D to illustrate that charge modification does not alter the size or state of aggregation of the polysaccharide. These data show that the zwitterionic charge motif neither facilitates nor interferes with antigen processing within the endo/lysosomal pathway.

Fig. 8.

Charge effects on carbohydrate processing. Superose 12 analysis of (A) native PSA, (B) NAc-PSA, and (C) group B streptococcal (GBS) polysaccharide from APC endosomal compartments (open) compared to untreated controls (filled). PSA is reduced to a low molecular weight product (arrow) that is known to be presented by MHCII. Likewise mod-PSA and nonzwitterionic GBS polysaccharide also enter APCs and are processed (arrow). (D) Overlay plot of the control PSA elution profiles from panels A and B, showing no measurable difference in size or aggregation state of the native polysaccharide (filled) compared to charge-modified PSA (open) prior to endocytosis and processing.

Since uptake, processing, and vesicular localization were normal for mod-PSA antigens, we then used these antigens in binding assays to determine if the lack of presentation and T cell activation seen with these modifications were the result of a reduction in ZPS affinity for MHCII. We found that both singly charged and neutral mod-PSA completely fail to bind the MHCII protein (Figure 9A). For cellular confirmation, radiolabeled mod-PSA antigens were used in co-IP experiments with anti-MHCII antibodies as described for the DM−/− cells above (Figure 6B). In support of the in vitro binding data, mod-PSA molecules were not presented in the context of MHCII on the cell surface (Figure 9B). Based on these findings, the zwitterionic motif promotes the specific interaction of PSA and MHCII, which also explains why nonzwitterionic carbohydrates are not able to bind MHCII or specifically activate T cells.

Fig. 9.

Charge effects on carbohydrate binding. (A) Native PSA (filled circles), NAc-PSA (open circles), Carbo-PSA (filled squares), and NAc-Carbo-PSA (open squares) binding to DR2 at 37°C and pH 5.0. All mod-PSA antigens failed to bind MHCII. (B) Native and NAc-PSA co-IP with anti-MHCII antibody from wt splenocytes, showing that mod-PSA antigens fail to be presented by APCs over an isotype background control.

Discussion

The recent demonstration of carbohydrate antigen processing and presentation by a MHCII-dependent mechanism in professional APCs (Cobb et al. 2004) shifted the long-standing paradigm limiting MHC presentation to protein antigens (Watts 1997; Watts and Powis 1999). These carbohydrate molecules enter APCs through endocytosis, where they are processed in a NO-dependent fashion to low molecular weight antigens that are loaded onto MHCII proteins for surface presentation and recognition by αβ T cell receptors (Cobb et al. 2004). In the present report, the carbohydrate PSA from the capsule of B. fragilis has been used in a series of studies aimed at understanding the biochemical mechanism of MHCII-dependent carbohydrate presentation. Our data show for the first time that PSA binds to the HLA-DR family at a 1:1 stoichiometry with high affinity and allelic selectivity, suggesting that specificity and restriction could play an important role in carbohydrate-driven T cell responses. Moreover, PSA binding to MHCII is mutually exclusive with peptide and superantigens, leading to a binding model where PSA could either share or mask contacts both inside and outside of the canonical peptide-binding groove, or induces a conformational shift in MHCII that precludes peptide and superantigen interactions. We previously reported that DM increases the amount of PSA bound to DR2 in vitro (Cobb et al. 2004), but here we demonstrate for the first time that DM increases the binding rate of antigens other than peptides and is required for cellular presentation by MHCII and in vivo T cell activation. Finally, we found that the zwitterionic motif is not required for APC entry, processing, or vesicular colocalization with MHCII, but is critical for MHCII loading and presentation. Indeed, all carbohydrates tested were processed to low molecular weight fragments, regardless of their charge nature and lack of ability to bind MHCII proteins. These data differentiate key attributes between T cell-dependent and -independent carbohydrate antigens while providing a step-by-step picture of the presentation mechanism within host immune cells (Figure 10).

Fig. 10.

Schematic of ZPS Antigen Presentation by MHCII. In step 1, carbohydrate antigens enter the vesicular traffic of APCs and are quickly processed to low molecular weight forms. These same molecules cannot bind to surface localized MHCII molecules due to the requirement of low pH and HLA-DM, nor can the processed carbohydrates bind to vesicular Ii-bound MHCII since peptides must first be removed from the binding groove in order for binding to occur. In step 2, the pH drops and cathepsin S cleaves Ii from CLIP. In step 3, carbohydrate antigens cannot bind MHC-CLIP efficiently enough within the cell because HLA-DM is not present. By step 4, the pH has reached 4.5, enabling HLA-DM to catalyze the exchange of CLIP for ZPS molecules—but not singly charged or neutral carbohydrates. In step 5, high affinity electrostatic interactions are formed between PSA and MHCII in an allelic selective manner. In step 6, HLA-DM dissociates from the complex, enabling step 7, where the MHCII-ZPS complex is shuttled to the cell surface for T cell recognition.

In vitro equilibrium binding assays using three DR alleles show a direct and saturable interaction between preprocessed PSA and MHCII. Interestingly, our data using DR1, DR2, and DR4 suggest that specificity and perhaps even restriction may play an important role in T cell responses against ZPS antigens. Peptides generally average 1 μM affinity with MHCII proteins, which is significantly weaker than many antibody–antigen interactions, such as HyHEL-5 binding to lysozyme at a Kd of 400 pM (Davies and Cohen 1996). It is therefore interesting to note that at 315 nM, the binding affinity of PSA to DR2 is relatively high in comparison to superantigens (Lee and Watts 1990) and peptide antigens (Babbitt et al. 1985).

Many superantigens bind to MHCII molecules in a promiscuous fashion, often with both a high and low affinity site (Papageorgiou and Acharya 1997), as reflected in the 1.5:1 average apparent stoichiometry of SEA binding to DR2 in our studies. The common lack of a one-to-one interaction in such circumstances correlates with the overall lack of specificity. In contrast, peptide antigens are strictly one to one in their association with MHCII molecules and this correlates with a high level of specificity both in presentation as well as recognition (Abbas et al. 2000). Given the relatively high affinity and the observation that all ZPS binding data show Bmax values at or near unity, our data lend strong support to the conclusion that ZPS antigens are presented by specific MHCII proteins as a one-to-one binary complex at the cell surface.

Furthermore, most peptides and superantigens associate with MHCII proteins primarily through hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding (Stern et al. 1994; Petersson et al. 2002). The in vitro binding experiments at high ionic strength suggest that while hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions likely contribute to PSA binding, electrostatic interactions play a central role in anchoring the ZPS antigen to MHCII. This observation is extended by the results using charge-modified PSA antigens where the alternating charge motif on PSA was found to be specifically required for binding and presentation by MHCII. Although we cannot completely rule out the possibility that the introduction of space-filling acetyl groups is responsible for the reduced activity rather than the simple loss of the positive charge in the NAc-PSA sample, it has been previously demonstrated that a lack of T cell stimulatory activity is also seen in PSA that has been simply deaminated (Tzianabos et al. 1993) and that loss of the zwitterionic motif results in significant conformational changes in PSA (Kreisman et al. 2007). As a result, it is unlikely that the additional acetyl group is playing a role beyond the elimination of the positive charge and change in the structure.

Our data also directly demonstrate that cellular entry and processing are not dependent upon the zwitterionic motif, implying that neither of these mechanisms are mediated by zwitterion-specific receptors or enzymes. Indeed, our observations confirm that mod-PSA antigens arrive in the correct vesicle for MHCII loading and presentation following processing but fail to be presented on the cell surface. Together with the binding data at various ionic strengths, we report that the alternating charge distribution on PSA is the key factor for MHCII presentation due in part to a requirement of electrostatic interactions during presentation.

Previous findings demonstrated a requirement of cellular entry for ZPS presentation to occur (Cobb et al. 2004). In comparing in vitro MHCII binding experiments, we found that PSA binding was remarkably more sensitive to pH (i.e., preferring acidic pH) than other antigen types despite the fact that no significant change in net carbohydrate charge would be expected within that range. Previously published observations even show a lack of T cell activation in bafilomycin A1-treated APCs (Stephen et al. 2005). These data show that unlike many peptides that bind quite well at pH 7.3 and are thus able to bind MHCII proteins on the surface of fixed APCs (Mukku et al. 1995), cell entry is necessary for ZPS molecules to achieve presentation because the association requires an acidic environment.

Published results have also implicated the exchange factor DM in the mechanism of ZPS presentation in that greater in vitro binding was seen with DM present (Cobb et al. 2004). In the present study, we show for the first time that DM catalyzes the rate of PSA binding to MHCII and is required for surface presentation on live APCs. In vivo abscess induction studies in DM−/− mice confirm the importance of DM in the efficiency of PSA-mediated T cell responses, strongly suggesting that peptides and PSA compete for MHCII-mediated presentation that is facilitated by DM. In agreement with this interpretation, time course experiments show an increase in the rate of PSA binding that correlates well with rate enhancements in other recombinant systems. In one landmark report, it was shown that the koff for peptides was enhanced as a linear function of DM concentration (Weber et al. 1996). In the same article, it was shown that without DM, the half-time (t1/2) of CLIP dissociation from DR1 was 5.7 h, whereas the presence of DM at 1.5 nM decreased the t1/2 to 2.4 h. Increasing the DM concentration to 3.4 nM further decreased t1/2 to 1.2 h. This correlates to enhancements of 2.4- and 4.8-fold over assays without DM, which is very similar to the observed 3-fold rate increase for PSA. In addition, we used a 1:1 molar ratio of DR and DM, which is much less than was used in another report that demonstrated an 82-fold increase in kon with DR1 and MBPp (Sloan et al. 1995). In that study, a 200-fold molar excess of DM was used over DR1. Given the linear relationship with DM concentration and activity (Weber et al. 1996), our 3-fold increase extrapolates to an estimated 600-fold increase at 1:200. Finally, with the involvement of DM in exchanging antigens on MHCII molecules, it is not surprising that our competitive binding experiments demonstrate that peptides and superantigens effectively compete for PSA binding.

Given the importance of pH on the binding of ZPS antigens to MHCII, the exclusivity of the interaction, and the requirement for acidic vesicular compartments for APC presentation (Cobb et al. 2004) and T cell activation (Kalka-Moll et al. 2002), a number of general MHCII pathway characteristics become important considerations in understanding the ZPS mechanism of presentation. For example, the pH optimum for DM activity is acidic (Denzin and Cresswell 1995) and the invariant chain (Ii) is cleaved away from MHCII through the action of the acid-activated protease cathepsin S, leaving behind CLIP (Riese et al. 1998). Ii cleavage makes the peptide-binding groove of MHCII available for antigenic peptides to exchange with CLIP because two peptides cannot bind to a single MHCII protein (Abbas et al. 2000). In addition, most superantigens bind to MHCII molecules with or without peptides because these two antigen types form nonexclusive and distinct molecular contacts on MHCII (Hogan et al. 2001).

Integrating these known MHCII pathway characteristics with the observations in this report, a number of important conclusions can be reached. First, the pH must be reduced to allow cathepsin S activation and Ii cleavage to allow for peptide removal prior to PSA binding because PSA and peptide cannot be bound at the same time. Second, a low pH is required to facilitate PSA binding and enable DM activity, which is critical for enabling cellular presentation and in vivo T cell activation through increasing the rate of exchange between peptide and PSA. Third, the competitive nature of the binding suggests that ZPS molecules either share and/or block some portion of the peptide and superantigen binding surfaces, or that binding results in a conformational change in MHCII that significantly reduces the recognition of peptides and superantigens. Finally, our data suggest that any successful ZPS-based vaccine would require entry into the acidic vesicular traffic of APCs to achieve MHCII presentation. Indeed, our observations generate a binding model in which a mutually exclusive and specific interaction of processed PSA and MHCII occurs through the formation of an unusual and uncharacterized antigen/MHCII complex that is recognized by T cells.

This report represents the first mechanistic characterization of carbohydrate antigen binding by MHCII. Interestingly, these data explain why many polysaccharides fail to activate T cells. In fact, nonzwitterionic carbohydrates enter the MHCII pathway and are even processed, but they cannot bind to MHCII even with the assistance from DM. This also provides a rationale for the efficacy of glycoconjugate vaccines in that the carrier protein is clearly not required for APC entry and trafficking, but for polysaccharide presentation by MHCII proteins—likely in the form of glycopeptides. Since the absence of a zwitterionic motif relegates carbohydrates to T cell independence, it is intriguing to point out that the modification of carbohydrates to create a zwitterionic motif introduces the ability to activate T cells (Tzianabos et al. 1993). As a result, this binding study represents the foundation of a potential new vaccine paradigm that allows for the development of carbohydrate-based vaccines against the surface glycans on bacterial pathogens through the introduction of a zwitterionic motif to enable carbohydrates to induce T cell-dependent immune responses via MHCII presentation.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Raji human lymphoma B cells (ATCC, Cat. CCL-86) were cultured in RPMI 1640 media with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Murine raw MΦs (ATCC, Cat. TIB-71) were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Media also with 10% FBS.

Mice

Mouse strains were wt, C57BL/6J, stock 000664, and DM−/−, B6.129S4-H2-DMatm1Dim/J, stock 004513 (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME) (Miyazaki et al. 1996).

Carbohydrate purification and labeling

Culturing, purification, and analysis by NMR spectroscopy, SDS–PAGE, and wavelength scans were performed as previously described (Tzianabos et al. 1992). PSA was judged to be >99% pure. Radioisotope, AlexaFluor® 594 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and biotin conjugation were performed as previously described (Cobb et al. 2004) and illustrated in Figure 1.

Peptides, protein expression, and purification

MBPp (residues 85–99) and TTp (residues 830–844) were obtained from New England Peptide (Gardner, MA). DR2 with MBPp (Gauthier et al. 1998) was purified from CHO cells as previously described using an antibody affinity column (Cobb et al. 2004). Pure DR1 (Stratikos et al. 2002) and DM (Mosyak et al. 1998) were gifts from Dr. Stephen DeWall, Harvard Medical School. Pure DR4 (Day et al. 2003) was a gift from Dr. Kai Wucherpfennig, Dana Farber Cancer Center.

In vitro binding assays and analysis

For all binding reactions, PSA was preprocessed with ozone for 1 h (MW 15 kDa) and then biotinylated as previously described (Cobb et al. 2004) and illustrated in Figure 1. ELISA wells (Immulon 2 HB, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) were coated with 0.1 μg DR or blocking agent. Unless noted, all PSA binding assays were performed in an acetate/phosphate saline buffer (A/PBS) at 37°C and pH 5.0 for 24 h with mixing. All peptide and superantigen binding assays were similarly performed with the same A/PBS buffer at 37°C for 24 h, only at pH 7.3, unless noted, which is similar to published peptide-binding conditions (Kalandadze et al. 1996; Day et al. 2003). Time course experiments ± 0.1 μg DM (1:1 mole ratio with DR) were performed as described for equilibrium binding assays with variable times. Bound antigens were detected using europium-conjugated streptavidin (Eu-SA) and time-resolved fluorometry (TRF) as previously established (Cobb et al. 2004).

The specific activity of the biotinylated PSA ligand (fluorescence units/mole) was determined using TRF prior to the completion of the binding studies. Briefly, PSA-specific rabbit sera was coated into the wells of Immulon 2 HB plates. 2 μM of radiolabeled PSA with a known cpm/mole specific activity was incubated in the wells for 1 h at room temperature. The unbound PSA was removed and the wells washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, pooled with the original supernatant, and quantified by scintillation counting. The capture efficiency of the sera was calculated using the unbound and total PSA [efficiency = 1 – (unbound cpm/total cpm)]. Using this value, the experiment was repeated with biotinylated PSA. The amount of biotinylated PSA bound to the plate was calculated using the measured capture efficiency above and divided by the TRF signal upon detection with Eu-SA to yield the specific activity in fluorescence units/mole for conversion of fluorescence units into moles ligand bound in all binding assays reported.

Plating efficiency of the MHCII molecules was determined by coating a known quantity of purified DR into Immulon 2 HB wells overnight at 4°C. The supernatant from those wells was then analyzed for absorbance at 280 nm and compared to control samples that contained equal amounts of DR used for coating. The percentage of protein concentration loss as a result of coating was then used as the immobilization efficiency (Figure 2A).

For analysis of binding data, the degree of binding (moles ligand bound/mole MHCII) was plotted against the ligand concentration and fit by nonlinear curve regression using Prism v. 3.03 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Affinity (Kd) and maximal binding (Bmax) were derived from a single-site, single-ligand binding model. For salt and pH effects, the normal saline buffer and pH 7.3 were used as the references (Figures 3 and 4). In general, normalization was performed by dividing the reference value into the corresponding experimental sample values and expressed as a percentage of the reference, which was set to 100%.

Competition

The competition assays were performed as described above only with nonbiotinylated competing antigens added concurrently with the ligand. All assays used 1 μM biotinylated ligand and varying amounts of competitor, as indicated in Results. In assays where PSA binding was monitored in the presence of competitors, the pH was 5.0. In assays where biotinylated peptide or SEA binding was monitored in the presence of competitor, the pH was 7.3. For all assays, the reference data were set to the no-competitor control for normalization.

Immunoprecipitations

Primary splenocytes were isolated from 12 wt or DM−/− mice using a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient and cultured in RPMI 1640 media with 10% FBS as previously described (Tzianabos et al. 2000). Cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C with 1 mg of radiolabeled PSA antigens. Surface MHCII was solublized and immunoprecipitated as previously described (Cobb et al. 2004). Radioactive immunoprecipitates were quantified by scintillation counting. For the knock-out study, normalization was performed with the wt cells as the reference and then calculating the percentage of those counts found in the DM−/− cell precipitates. For mod-PSA co-IP experiments, native PSA was used as the reference.

Abscess induction

Induction of abscesses in mice was performed as previously reported with 50 μg of PSA in sterilized cecal contents (Tzianabos et al. 1999). Animals were examined for the presence of at least one abscess 6 days after challenge.

Psa charge modifications

Positive free amine groups and negative carboxylate groups were eliminated from the PSA repeating unit as previously described (Tzianabos et al. 1993). Briefly, amines were acetylated using acetic anhydride in dH2O, whereas carboxylates were neutralized using carbodiimide and borohydride reduction.

Processing assays/chromatography

Raji antigen processing assays were performed as previously described (Cobb et al. 2004). Vesicular lysates were analyzed Superose 12 chromatography on a FPLC system (BioLogic HR, BioRad). Fractions were assayed for radioactivity to determine the elution profile.

The effects of 1 M NaCl, acidic pH (pH 5.0), and charge modifications (N-acetylation, analyzed in PBS) on the aggregation state of PSA samples were also analyzed by a Superose 12 elution profile on a FPLC system. In all cases, the PSA samples were allowed to incubate for 30 min in the respective conditions at room temperature prior to loading onto the column that was also equilibrated in the same treatment conditions (saline, saline + 1 M NaCl, pH 5.0, or pH 7.2). Elution profiles were collected with absorbance at 205 nm.

Confocal microscopy

Human Raji B cells (∼106) were incubated with 50 μg of AlexaFluor®594-conjugated native or mod-PSA for 3 h at 37°C. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with AlexaFluor® 488-conjugated anti-DR (Raji, clone L243) antibodies for viewing with a Zeiss Pascal confocal microscope (63× objective lens; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kai Wucherpfennig for many helpful suggestions in addition to providing the cell line producing HLA-DR2 and for providing the purified HLA-DR4 protein. Also, we thank Dr. Stephen DeWall for helpful advice and providing purified HLA-DR1 and HLA-DM. Finally, we thank Dr. Qun Wang for 1H-NMR analysis of the mod-PSA samples.

Funding

National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (AI039576 to D.L.K., AI062707 to B.A.C.); the Ford Foundation and the National Academy of Sciences (to B.A.C.).

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Abbreviations

- A/PBS

acetate-phosphate saline buffer

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- carbo-PSA

carbodiimide reduced PSA

- co-IP

co-immunoprecipitation

- DM

HLA-DM

- DR1

HLA-DR1

- DR2

HLA-DR2

- Eu-SA

europium-conjugated streptavidin

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- MBPp

myelin basic protein peptide

- MHCII

class II MHC

- mod-PSA

charge-modified PSA

- NAc-Carbo-PSA

neutral PSA

- NAc-PSA

N-acetylated PSA

- PSA

polysaccharide A

- SEA

staphylococcal enterotoxin A

- TRF

time-resolved fluorescence

- TTp

tetanus toxin peptide

- ZPS

zwitterionic polysaccharide

References

- Abbas AK, Lichtman AH, Pober JS. Cellular and Molecular Immunology. 4th ed. New York: W.B. Saunders; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Babbitt BP, Allen PM, Matsueda G, Haber E, Unanue ER. Binding of immunogenic peptides to Ia histocompatibility molecules. Nature. 1985;317:359–361. doi: 10.1038/317359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann H, Tzianabos AO, Brisson JR, Kasper DL, Jennings HJ. Structural elucidation of two capsular polysaccharides from one strain of Bacteroides fragilis using high-resolution NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4081–4089. doi: 10.1021/bi00131a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boitel B, Ermonval M, Panina-Bordignon P, Mariuzza RA, Lanzavecchia A, Acuto O. Preferential V beta gene usage and lack of junctional sequence conservation among human T cell receptors specific for a tetanus toxin-derived peptide: Evidence for a dominant role of a germline-encoded V region in antigen/major histocompatibility complex recognition. J Exp Med. 1992;175:765–777. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.3.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker JO, Li Q, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL, Finberg RW. Mitogenic activity of purified capsular polysaccharide A from Bacteroides fragilis: Differential stimulatory effect on mouse and rat lymphocytes in vitro. J Immunol. 1999;162:2235–2242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch R, Pashine A, Garcia KC, Mellins ED. Stabilization of soluble, low-affinity HLA-DM/HLA-DR1 complexes by leucine zippers. J Immunol Methods. 2002;263:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YH, Roehrl MH, Kasper DL, Wang JY. A unique structural pattern shared by T-cell-activating and abscess-regulating zwitterionic polysaccharides. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15144–15151. doi: 10.1021/bi020491v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb BA, Wang Q, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. Polysaccharide processing and presentation by the MHCII pathway. Cell. 2004;117:677–687. doi: 10.016/j.cell.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies DR, Cohen GH. Interactions of protein antigens with antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day CL, Seth NP, Lucas M, Appel H, Gauthier L, Lauer GM, Robbins GK, Szczepiorkowski ZM, Casson DR, Chung RT, et al. Ex vivo analysis of human memory CD4 T cells specific for hepatitis C virus using MHC class II tetramers. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:831–842. doi: 10.1172/JCI18509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin LK, Cresswell P. HLA-DM induces CLIP dissociation from MHC class II alpha beta dimers and facilitates peptide loading. Cell. 1995;82:155–165. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier L, Smith KJ, Pyrdol J, Kalandadze A, Strominger JL, Wiley DC, Wucherpfennig KW. Expression and crystallization of the complex of HLA-DR2 (DRA, DRB1*1501) and an immunodominant peptide of human myelin basic protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11828–11833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan RJ, VanBeek J, Broussard DR, Surman SL, Woodland DL. Identification of MHC class II-associated peptides that promote the presentation of toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 to T cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:6514–6522. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardetzky TS, Brown JH, Gorga JC, Stern LJ, Urban RG, Chi YI, Stauffacher C, Strominger JL, Wiley DC. Three-dimensional structure of a human class II histocompatibility molecule complexed with superantigen. Nature. 1994;368:711–718. doi: 10.1038/368711a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardetzky TS, Gorga JC, Busch R, Rothbard J, Strominger JL, Wiley DC. Peptide binding to HLA-DR1: A peptide with most residues substituted to alanine retains MHC binding. EMBO J. 1990;9:1797–1803. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalandadze A, Galleno M, Foncerrada L, Strominger JL, Wucherpfennig KW. Expression of recombinant HLA-DR2 molecules. Replacement of the hydrophobic transmembrane region by a leucine zipper dimerization motif allows the assembly and secretion of soluble DR alpha beta heterodimers. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20156–20162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalka-Moll WM, Tzianabos AO, Bryant PW, Niemeyer M, Ploegh HL, Kasper DL. Zwitterionic polysaccharides stimulate T cells by MHC class II-dependent interactions. J Immunol. 2002;169:6149–6153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreisman LS, Friedman JH, Neaga A, Cobb BA. Structure and function relations with a T-cell-activating polysaccharide antigen using circular dichroism. Glycobiology. 2007;17:46–55. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwl056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JM, Watts TH. Binding of staphylococcal enterotoxin A to purified murine MHC class II molecules in supported lipid bilayers. J Immunol. 1990;145:3360–3366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki T, Wolf P, Tourne S, Waltzinger C, Dierich A, Barois N, Ploegh H, Benoist C, Mathis D. Mice lacking H2-M complexes, enigmatic elements of the MHC class II peptide-loading pathway. Cell. 1996;84:531–541. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosyak L, Zaller DM, Wiley DC. The structure of HLA-DM, the peptide exchange catalyst that loads antigen onto class II MHC molecules during antigen presentation. Immunity. 1998;9:377–383. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80620-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukku PV, Passmore D, Phan D, Nag B. pH dependent binding of high and low affinity myelin basic protein peptides to purified HLA-DR2. Mol Immunol. 1995;32:555–564. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(95)00030-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag B, Arimilli S, Mukku PV, Astafieva I. Functionally active recombinant alpha and beta chain-peptide complexes of human major histocompatibility class II molecules. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10413–10418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag B, Mukku PV, Arimilli S, Phan D, Deshpande SV, Winkelhake JL. Antigenic peptide binding to MHC class II molecules at increased peptide concentrations. Mol Immunol. 1994;31:1161–1168. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou AC, Acharya KR. Superantigens as immunomodulators: Recent structural insights. Structure. 1997;5:991–996. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersson K, Thunnissen M, Forsberg G, Walse B. Crystal structure of a SEA variant in complex with MHC class II reveals the ability of SEA to crosslink MHC molecules. Structure (Camb) 2002;10:1619–1626. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00895-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riese RJ, Mitchell RN, Villadangos JA, Shi GP, Palmer JT, Karp ER, De Sanctis GT, Ploegh HL, Chapman HA. Cathepsin S activity regulates antigen presentation and immunity. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2351–2363. doi: 10.1172/JCI1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan KR, McNeil LK, Dao C, Jensen PE, Evavold BD. Modification of peptide interaction with MHC creates TCR partial agonists. Cell Immunol. 2004;227:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan VS, Cameron P, Porter G, Gammon M, Amaya M, Mellins E, Zaller DM. Mediation by HLA-DM of dissociation of peptides from HLA-DR. Nature. 1995;375:802–806. doi: 10.1038/375802a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KJ, Pyrdol J, Gauthier L, Wiley DC, Wucherpfennig KW. Crystal structure of HLA-DR2 (DRA*0101, DRB1*1501) complexed with a peptide from human myelin basic protein. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1511–1520. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen TL, Niemeyer M, Tzianabos AO, Kroenke M, Kasper DL, Kalka-Moll WM. Effect of B7-2 and CD40 signals from activated antigen-presenting cells on the ability of zwitterionic polysaccharides to induce T-cell stimulation. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2184–2189. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2184-2189.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern LJ, Brown JH, Jardetzky TS, Gorga JC, Urban RG, Strominger JL, Wiley DC. Crystal structure of the human class II MHC protein HLA-DR1 complexed with an influenza virus peptide. Nature. 1994;368:215–221. doi: 10.1038/368215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stingele F, Corthesy B, Kusy N, Porcelli SA, Kasper DL, Tzianabos AO. Zwitterionic polysaccharides stimulate T cells with no preferential Vbeta usage and promote anergy, resulting in protection against experimental abscess formation. J Immunol. 2004;172:1483–1490. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratikos E, Mosyak L, Zaller DM, Wiley DC. Identification of the lateral interaction surfaces of human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DM with HLA-DR1 by formation of tethered complexes that present enhanced HLA-DM catalysis. J Exp Med. 2002;196:173–183. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzianabos AO, Finberg RW, Wang Y, Chan M, Onderdonk AB, Jennings HJ, Kasper DL. T cells activated by zwitterionic molecules prevent abscesses induced by pathogenic bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6733–6740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.6733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzianabos AO, Onderdonk AB, Rosner B, Cisneros RL, Kasper DL. Structural features of polysaccharides that induce intra-abdominal abscesses. Science. 1993;262:416–419. doi: 10.1126/science.8211161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzianabos AO, Pantosti A, Baumann H, Brisson JR, Jennings HJ, Kasper DL. The capsular polysaccharide of Bacteroides fragilis comprises two ionically linked polysaccharides. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18230–18235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzianabos AO, Russell PR, Onderdonk AB, Gibson FC, III, Cywes C, Chan M, Finberg RW, Kasper DL. IL-2 mediates protection against abscess formation in an experimental model of sepsis. J Immunol. 1999;163:893–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzianabos AO, Wang JY, Lee JC. Structural rationale for the modulation of abscess formation by Staphylococcus aureus capsular polysaccharides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9365–9370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161175598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kalka-Moll WM, Roehrl MH, Kasper DL. Structural basis of the abscess-modulating polysaccharide A2 from Bacteroides fragilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13478–13483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.25.13478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts C. Capture and processing of exogenous antigens for presentation on MHC molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:821–850. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts C, Powis S. Pathways of antigen processing and presentation. Rev Immunogenet. 1999;1:60–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber DA, Evavold BD, Jensen PE. Enhanced dissociation of HLA-DR-bound peptides in the presence of HLA-DM. Science. 1996;274:618–620. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.