Abstract

Evidence that prevention, diagnosis and treatment of toxoplasmosis is beneficial developed as follows: antiparasitic agents abrogate Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoite growth, preventing destruction of infected, cultured, mammalian cells and cure active infections in experimental animals, including primates. They treat active infections in persons who are immune-compromised, limit destruction of retina by replicating parasites and thereby treat ocular toxoplasmosis and treat active infection in the fetus and infant. Outcomes of untreated congenital toxoplasmosis include adverse ocular and neurologic sequelae described in different countries and decades. Better outcomes are associated with treatment of infected infants throughout their first year of life. Shorter intervals between diagnosis and treatment in utero improve outcomes. A French approach for diagnosis and treatment of congenital toxoplasmosis in the fetus and infant can prevent toxoplasmosis and limit adverse sequelae. In addition, new data demonstrate that this French approach results in favorable outcomes with some early gestation infections. A standardized approach to diagnosis and treatment during gestation has not yet been applied generally in the USA. Nonetheless, a small, similar experience confirms that this French approach is feasible, safe, and results in favorable outcomes in the National Collaborative Chicago-based Congenital Toxoplasmosis Study cohort. Prompt diagnosis, prevention and treatment reduce adverse sequelae of congenital toxoplasmosis.

Keywords: congenital toxoplasmosis, prevention, treatment

Morbidity and mortality associated with toxoplasmosis has been well documented (Petrof & McLeod 2002, Remington et al. 2006, Boyer et al. 2008, Roberts et al. 2008). There have been recent discussions questioning the benefit of prevention, diagnosis and treatment of this infection because there are no studies including placebo controls and randomization (Gras et al. 2001, 2005, Gilbert et al. 2003, 2008, Salt et al. 2005, Gilbert & Dezateux 2006, Stanford et al. 2006, Thiébaut et al. 2006, Freeman et al. 2008). Also, current standards of evidence based medicine were applied to earlier studies and current studies in which data from a number of centers in Europe (each using different measures and regimens for diagnosis and/or treatment) were grouped or studies used questionnaires to assess development of young children (Gras et al. 2001, Thulliez 2001, Freeman et al. 2008). These latter studies did not provide clear evidence of benefit, which may be due to their design. Therefore, data which demonstrate that treatment and prevention of active Toxoplasma gondii infections are feasible, safe and of benefit are reviewed and considered in the context of other recent publications.

The evidence demonstrating that active infection can be treated and outcome improved developed as follows: antimicrobial treatment of T. gondii in tissue culture animal models eliminates actively replicating parasites and leads to prevention or resolution of signs of disease in these models (Eyles & Coleman 1953a, b, 1955a, Frenkel & Hitchings 1957, Garin et al. 1968, 1985, Brus et al. 1971, Beverley et al. 1973, Feldman 1973, Sheffield & Melton 1975, Grossman & Remington 1979, Garin Paillard 1984, Mack & McLeod 1984, Picketty et al.1990 McLeod et al. 1992, Hohlfels et al. 1994, Schoondermark-van de Ven et al. 1995, Derouin 2001, Meneceur et al. 2008, Mui et al. 2008); treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis, toxoplasmosis in immune-compromised persons of congenital toxoplasmosis in humans abrogates symptoms and signs of active infection and improves outcomes (Perkins et al. 1956, Kräubig 1963, Thalhammer 1969, Couvreur et al. 1984a, 1993, Desmonts & Couvreur 1984, Daffos et al. 1988, Hohlfeld et al. 1989, 1994a, b, Dannemann et al. 1992, McLeod et al. 1992, 2006a, McAuley et al. 1994, Patel et al. 1996, Torre et al. 1998, Boyer 2000, 2005, 2008, Thulliez 2001, Brézin et al. 2003, Kim 2006, Berrebi et al. 2007, Petrof & McLeod 2002, SYROCOT et al. 2007, Kieffer et al. 2008), the more rapidly human congenital toxoplasmosis is diagnosed and treated, the shorter the time available for tissue destruction by the parasite and thus the better the outcomes (Remington et al. 2006, SYROCOT et al. 2007, Kieffer et al. 2008); and detection of the infection acquired during the gestation the fetus and rapid initiation of treatment, is often associated with favorable outcomes (Daffos et al. 1988, Hohlfeld et al. 1989, Foulon et al. 1999, Binquet et al. 2003, Brèzin et al. 2003, Kodjikian et al. 2006, Remington et al. 2006, Kieffer et al. 2008).

Herein, in addition to consideration of earlier published data, we present additional, unpublished data which indicate that treatment during gestation and infancy reduces parasite burden and can thereby result in favorable outcomes and prevent adverse sequelae from congenital toxoplasmosis. In North America, where there is only occasional prenatal screening facilitating treatment in utero, congenital toxoplasmosis usually still presents with substantial signs and symptoms, causing considerable suffering and deaths (Eichenwald 1960, Couveur & Desmonts 1962, McLeod et al. 1979, 2006a, Wilson et al. 1980, McAuley et al. 1994, Roizen et al. 1995, 2006, Mets et al. 1996, Patel et al. 1996, Swisher et al. 2006, Benevento et al. 2008, Jamieson et al. 2008, Phan et al. 2008a, b). Formerly, this type of severe illness due to congenital toxoplasmosis was also common in France, but such severe disease is only rarely seen in France now that there is systematic prenatal screening, diagnosis and treatment for this infection (Desmonts 1982, Couvreur et al. 1984b, Desmonts 1985, Aspöck et al. 1986, Daffos et al. 1988, Hohlfeld et al. 1989, Couvreur 1991, Foulon et al. 1994, 1999, Wallon et al. 1994, 2004, Peyron et al. 1996, Thulliez 2001, Binquet et al. 2003, Brézin et al. 2003, Kodjikian et al. 2006, Remington et al. 2006, SYROCOT et al. 2007, Kieffer et al. 2008).

Evidence that medicines can treat infections with T. gondii and toxoplasmosis

Anti-parasite agents are effective in tissue culture and in animal models

T. gondii is an apicomplexan parasite that replicates in cells and tissues, especially in the brain and eye (Weis & Kim 2004, Roberts et al. 2008). Anti-parasitic agents that restrict the growth of actively proliferating parasites, which destroy cells and tissues, thereby prevent damage to the brain and eye (Eyles & Coleman 1953a, b, 1955a, b, Frenkel & Hitchings 1957, Brus et al. 1971, Beverley et al. 1973, Feldman 1973, Sheffield & Melton 1975, Grossman & Remington 1979, Garin & Paillard 1984, Mack & McLeod 1984, Garin et al. 1985, Araujo et al. 1992, McLeod et al. 1992, Derouin 2001, Remington et al. 2006, Meneceur et al. 2008). Rigorous observations, which support this conclusion, and approaches to treatment based on these observations developed as follows:

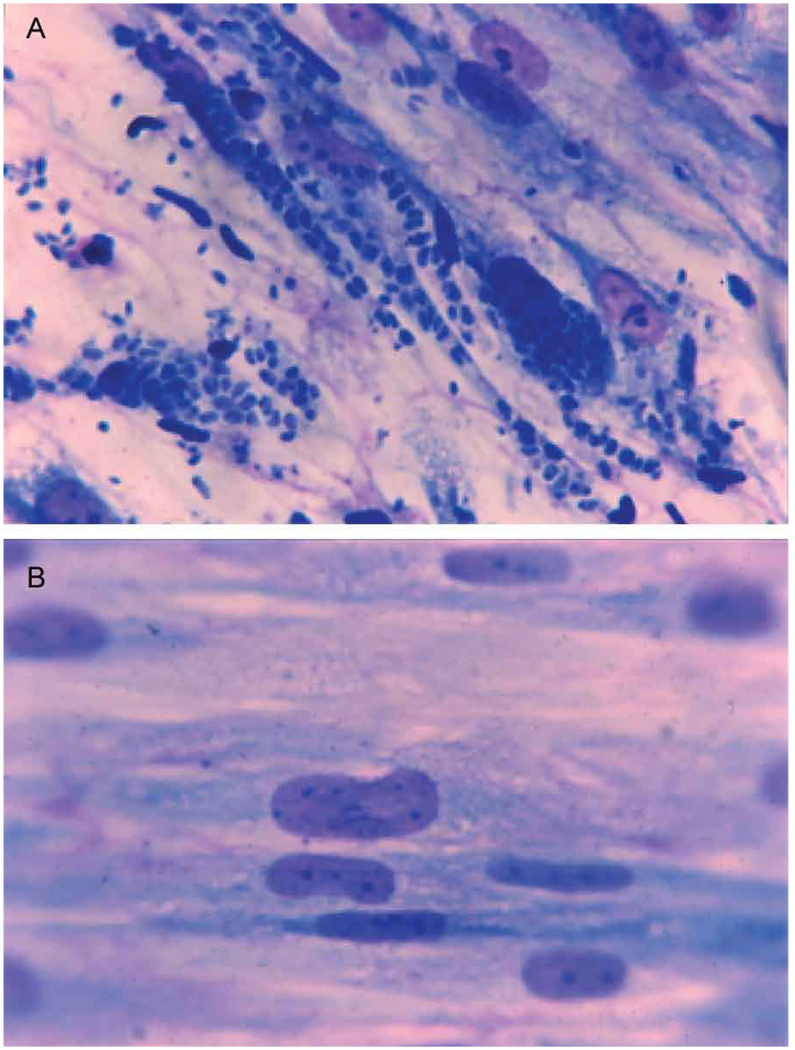

Studies of parasites in tissue culture with and without antimicrobial agents such as pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine demonstrate that antimicrobial agents reduce growth of the rapidly proliferating tachyzoites and destruction of a variety of mammalian host cells (Fig. 1) (Zuther et al. 1999, Mack & McLeod 1984, Mcleod et al. 1992). The combination of pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine is 8-fold more active than either pyrimethamine or sulfadiazine alone and has been the “gold standard” to which other antimicrobial agents alone, and in combination, have been compared (Remington et al. 2006, Mui et al. 2008).

Fig. 1.

A: Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites in tissue culture with medium alone; B: with antimicrobial agent. Note growth of parasite and destruction of host cells (adapted from Zuther et al. 1999, with permission).

T. gondii infections in experimental animals are effectively treated by antimicrobial agents that reduce parasite and disease burden, permitting survival (Eyles & Coleman 1953a, b, 1955a, b, Frenkel & Hitchings 1957, Garin & Paillard 1984, Garin et al. 1985, Brus et al. 1971, Beverley et al. 1973, Feldman 1973, Grossman & Remington 1979). An early example of the efficacy of pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine and other medicines alone or in combination with pyrimethamine in primates is in Table I (Harper et al. 1985). In separate studies, trimethoprim:sulfamethoxazole was found to be less active in vitro and in a murine model than pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine (Grossman & Remington 1979). Other antimicrobial agents also have been found to be effective against T. gondii tachyzoites in animal models (Petrof & McLeod 2002, Remington et al. 2006).

TABLE I.

Effect of treatment on survival of squirrel monkeys following Toxoplasma gondii infection

| Treatment of squirrel monkeys | Survival by 9 days after infectiona (%) |

|---|---|

| Untreated controls | 0/6 (0) |

| Pyrimethamine/sulfadiazine | 5/5 (100) |

| Clindamycin/sulfadiazine | 4/4 (100) |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 4/4 (100) |

| Sulfamethoxazole | 3/3 (100) |

Infection was with Beverly strain of Toxoplasma administered orally. Systemic disease that is almost always fatal in squirrel monkeys within 7–9 days was produced by oral inoculation of a brain suspension made from mice chronically infected with the Beverly strain of T. gondii. Dose regimens used in this study did not allow determination whether addition of PYR or TMP changed protection of sulfonamide alone and did not address comparative efficacy of sulfadiazine, clindamycin or pyrimethamine alone (Harper et al. 1985). Other studies have demonstrated less efficacy of TMP/SMZ than pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine (Grossman & Remington 1979).

Antimicrobial treatment of immune-compromised persons improves outcomes

Anti-parasitic treatment of immune-compromised persons who have active central nervous system disease and other manifestations of active toxoplasmosis results in the resolution of signs of disease caused by this parasite (Fig. 2) (Ryning et al. 1979, Dannemann et al. 1992, Torre et al. 1998, Petrof & McLeod 2002). Pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine are the medicines used as the first line of treatment. Trimetho-prim-sulfamethoxazole has also been used. Other medicines or medicine combinations that have been used include pyrimethamine in high dosage regimens alone or in combination with clindamycin, clarithromycin, azithromycin or atovaquone when there is hypersensitivity to sulfonamides (Dannemann et al. 1992, Torre et al. 1998, Petrof & McLeod 2002, Boyer et al. 2005, McLeod et al. 2006b).

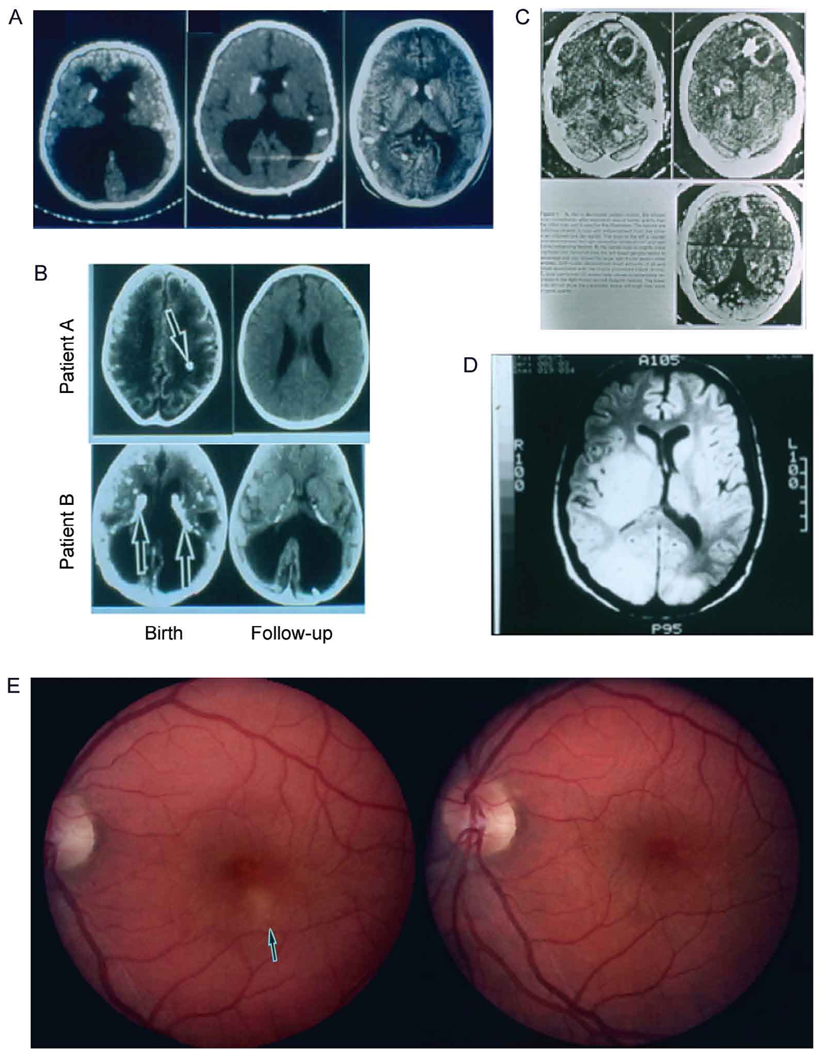

Fig. 2.

A: resolution of hydrocephalus and brain growth following treatment and shunt in child with congenital toxoplasmosis (Swisher et al. 1994, with permission); B: resolution or diminution of size of intracerebral calcifications during treatment for congenital toxoplasmosis in the first year of life. Cranial CT scans were obtained in the neonatal period and at one year of age. Each cranial CT scan was reviewed by the same study neuroradiologist. Calcification size and number were computed (Patel et al. 1996, with permission). Thirty two (82%) of 39 children had calcifications that diminished or resolved and seven (18%) had calcifications that remained the same size (C) and appearance of brain abscesses in a patient with a cardiac transplant (Ryning et al. 1979, with permission) (D) and a patient with toxoplasmic encephalitis who had AIDS in the pre-HAART era (Levin et al. 1983, with permission). Lesions resolved and clinical status improved for both the patients shown in C and D when they were treated with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine; E: active retinal lesion before (left) and within a month of initiating treatment (right).

Treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis results in resolution of lesions and improved vision

In persons with active toxoplasmic chorioretinal lesions, treatment with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine has resulted in the prompt resolution of activity of these lesions (Fig. 2) (Perkins et al. 1956, Perkins 1973, Mets et al. 1996, Roberts & McLeod 1999, Roberts et al. 2001, 2008). Administration of intravitreal antibody to the angiogenic growth factor VegF resulted in resolution of choroidal neovascular membranes caused by ocular toxoplasmosis (Benevento et al. 2008). Suppression of the parasite by treatment of persons in Brazil with ocular toxoplasmosis that had frequently recurred with trimethoprin and sulfamethoxazole resulted in fewer recurrences of eye disease but hypersensitivity to sulfonamides also was noted (Roussel et al. 1987).

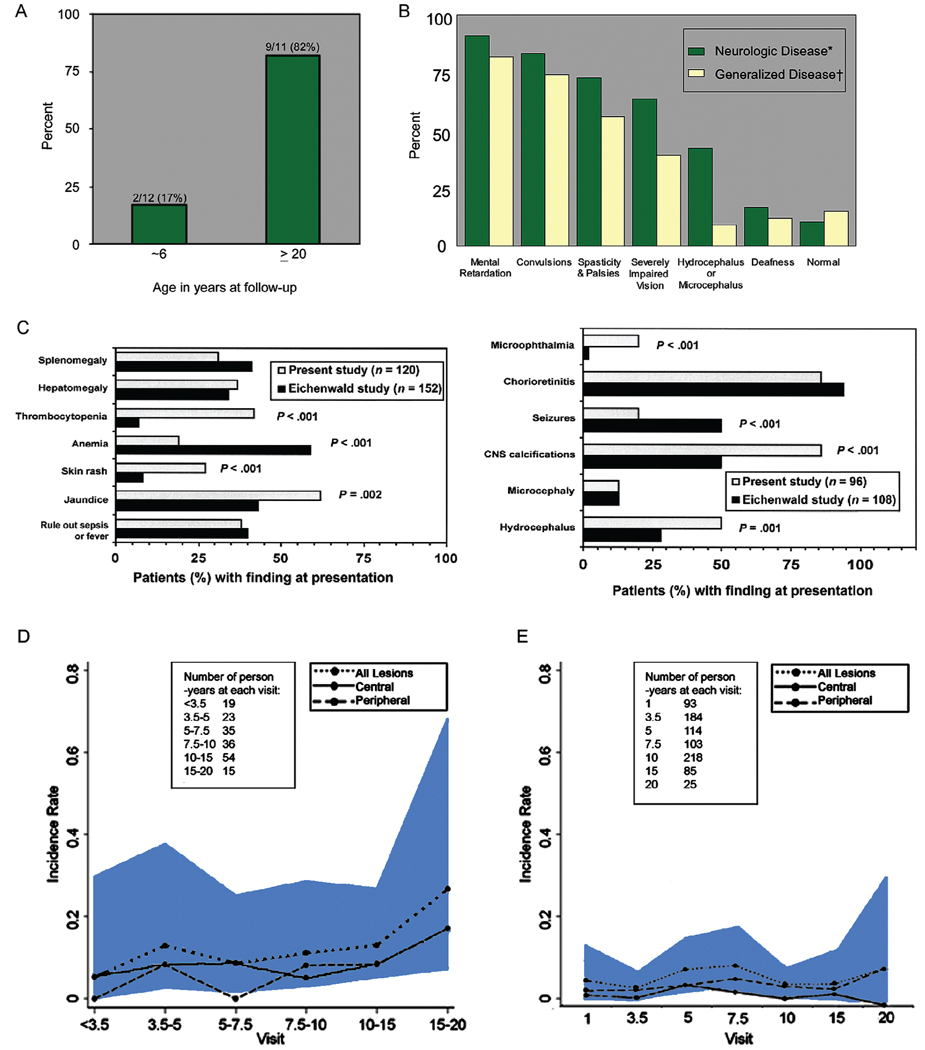

Outcomes of untreated congenital toxoplasmosis

Outcomes of untreated congenital infections have been well-characterized (Fig. 3, Fig. 4) (Eichenwald 1960, Saxon et al. 1973, McLeod et al. 2006a); Table II (Wilson et al. 1980), Table III (Eichenwald 1960), Table IV (Desmonts & Courveur 1974b),Table V (Saxon et al. 1973) and Table VI (Eichenwald 1960, Hohlfeld 1989, Remington et al. 2006) (Wolf & Cowen 1937–1939, 1939a, b, 1959, Dyke et al. 1942, Paige et al. 1942, Freudenberg 1947, Sabin & Feldman 1949, Verlinde & Makstenieks 1950, Frenkel & Friedlander 1952, Hall et al. 1953, Kozar et al. 1954, Bain et al. 1956, Hogan et al. 1957, Schubert 1957, Bruhl et al. 1958, Aagaard & Melchior 1959, Eichenwald 1960, Hedenstrom et al. 1961, Kvirikadze & Yourkova 1961, Couvreur & Desmonts 1962, 1964, Feldman 1963, Tós-Luty et al. 1964, Siliaeva 1965, Kräubig 1966, Ristow 1966, Alford et al. 1967, 1969, 1974, 1975, Justus 1968, Mussbichler 1968, Stern et al. 1969, Couvreur 1971, Mackie et al. 1971, Puissan et al. 1971, Parissi 1973, Saxon et al. 1973, Thalhammer 1973, Desmonts & Couvreur 1974a, b, 1984, O’Connor 1974, Puri et al. 1974, Wright 1974, Cunningham et al. 1976, Griscom et al. 1977, Stagno et al. 1977, Khodr & Matossian 1978, Hervei & Simon 1979, Collins & Cromwell 1980, Wilson et al. 1980, Flamm & Aspöck 1981, Desmonts 1982, 1985, 1987, Koppe et al. 1986, Koppe & Kloosterman 1982, Margit & Istvan 1983, Couvreur et al. 1984a, b, 1985, 1993, Dunn & Weisberg 1984, Labadie & Hazeman 1984, Coffey 1985, Desmonts et al. 1985, Diebler et al. 1985, Blaakaer 1986, Roper 1986, Coppola et al. 1987, Roussel et al. 1987, McCabe & Remington 1988, Vanhaesebrouck et al. 1988, Massa et al. 1989, Titelbaum et al. 1989, Roberts & Frenkel 1990, Couvreur 1991, Aspöck & Pollak 1992, McGee et al. 1992, McLeod et al. 1992, 2006a, Caiaffa et al. 1993, Rothova 1993, Woods & Englund 1993, Berrebi et al. 1994, Hohlfeld et al. 1994b, McAuley et al. 1994, Swisher et al. 1994, Meenken et al. 1995, Potasman et al. 1995, Aspöck 1996, Mets et al. 1996, Patel et al. 1996, Yamakawa et al. 1996, Virkola et al. 1997, Oygür et al. 1998, Friedman et al. 1999, McLeod & Remington 2006, Remington et al. 2006, Boyer et al. 2008). Initial manifestations at birth are strongly influenced by the time during gestation that infection is acquired (Table IV), but also involve host genetics (Fig. 5) (Mack et al. 1999, Jamiesen et al. 2008). Manifestations may also be influenced by parasite genetics (Glasner et al. 1992, Dardé et al. 1998, Camargo-Neto et al. 2000, Boothroyd & Grigg 2002, Silveira et al. 2002, Vallochi et al. 2002, Andrade et al. 2008), although Type 2, non 2, and atypical parasites can all cause both mild and severe congenital disease (Mack et al. 1999, Peyron et al. 2006, Remington et al. 2006, Jamiesen et al. 2008, R McLeod et al., unpublished observations). These adverse outcomes of infections that are untreated or treated for only one month postnatally, both at birth and later, have been confirmed in a number of studies, case series and reports (Table II, Table III, Table V, Table VI, Fig. 4D). For example, Saxon et al. (1973) performed a single blind study in which eight children with subclinical infection and eight matched control subjects were evaluated. A subclinical infection was characterized by changes in the protein levels and cell counts in cerebrospinal fluid and substantiated if T. gondii specific antibody levels remained the same or increased from birth through the first year of life. The pairs of children were matched on the basis of chronologic age, sex, race, birth weight, age of mother, gestational age, socioeconomic level and, for five of eight pairs, marital status of the mother at the time of the child’s birth. In this study, Saxon et al. (1973) found that the mean intelligence quotient (IQ) for untreated infected children was significantly lower (p = 0.016) than the mean IQ of the matched, uninfected control subjects (Table V). From this study, while the children involved were not severely cognitively impaired, the investigators concluded that a subclinical infection with congenital toxoplasmosis does cause some “intellectual impairment”. In every series, even those of children who have subclinical involvement who are untreated or treated for one month, > 82% have retinal disease by the time they are adolescents (Fig. 4A) (Eichenwald 1960, Wilson et al. 1980, Koppe & Kloosterman 1982, Koppe et al. 1986). Children who have generalized or neurologic signs at birth, if untreated or treated for only one month, by four years of age have a > 85% chance of having mental retardation, 81% have seizures, 70% have motor difficulties, 60% have severe vision loss, 33% have hydro or microcephalus, 14% have hearing loss and only 11% were normal (Table III, Fig. 4B, C) (Eichenwald 1960). The majority of children diagnosed in infancy in North America have generalized or severe manifestations at birth which lead to their diagnosis (R McLeod, unpublished observations). Recurrent retinal disease appears to occur commonly (Fig. 4C, D).

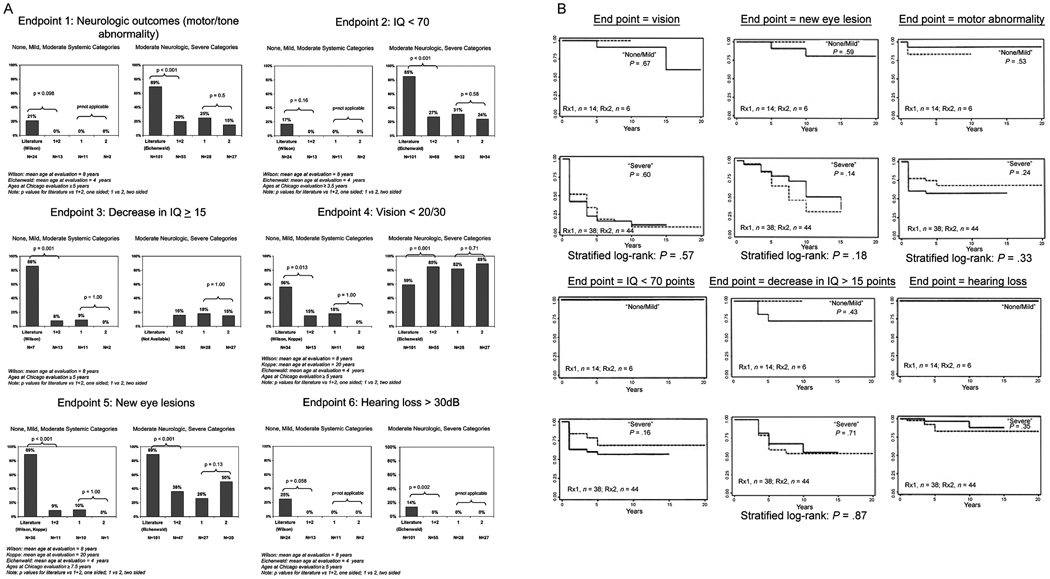

Fig. 3.

A: improved outcomes in treated children contrasted with earlier cohorts and comparing a higher and lower dose regimen in a randomized controlled trial. Frequency of outcomes for each endpoint for patients in our study, compared with the frequency in the literature (Eichenwald 1960, Saxon et al. 1973, Wilson et al. 1980, Koppe et al. 1982, 1986, McLeod et al. 2006a). There is no visible trend for superiority or statistically significant superiority for treatment arm 1 or treatment arm 2 at this time. Results may differ in the future, because the majority of the children enrolled are entering adolescence and early adulthood, a critical time when outcomes may vary. It is also important that outcomes of offspring of the treated children be established in the following years of this study. 1: treatment arm 1 [daily doses of pyrimethamine (1 mg/kg) for two months]; 2: treatment arm 2 [daily doses of pyrimethamine (1 mg/kg) for six months. Following daily dosing with pyrimethamine, this dose was administered on each Monday, Wednesday and Friday. 50 mg/kg sulfadiazine was administered throughout as was calcium leukovorin]; B: Kaplan-Meier Curves showing the outcomes for each endpoint for patients in the pooled feasibility/observational phase and the randomized phase who received treatment 1 (solid line) or treatment 2 (dotted line). There is no visible trend for superiority or statistically significant superiority at this time. Results may differ in the future, because the majority of the children enrolled are entering adolescence and early adulthood, a critical time when outcomes may vary. It is also important that outcomes of offspring of the treated children be established in the following years of this study. IQ: intelligence quotient; Rx1: treatment arm 1; Rx2: treatment arm 2 (adapted from McLeod et al. 2006a, with permission.)

Fig. 4.

A: Koppe study visual outcome for 12 children who were asymptomatic at birth, untreated or treated less than once a month and evaluated when they were six and 20 years old. Percentage of children with retinal disease. Adverse outcomes in untreated congenital toxoplasmosis or when congenital toxoplasmosis was treated for only one month; B: Eichenwald study outcome for 101 patients at ≥ 4 years old. Asterisk: patients with neurologic disease had otherwise undiagnosed central nervous system disease in the first year of life (n = 70); †: patients with generalized disease had otherwise undiagnosed non-neurologic disease in the first two months of life (n = 31); C: children in the NCCCTS in the moderate/severe categories had as severe disease as did children in the Eichenwald series (data are from Eichenwald 1960, Koppe et al. 1982, 1986, Labadie & Hazeman 1984, McLeod et al. 2006a, with permission); D: new eye lesions in children who missed treatment in the first year of life; E: new eye lesions in children treated in the first year of life. In D and E, incidence rate: # of patients with new lesions per person-year. Blue shaded area in D and E is confidence interval.

TABLE II.

Adverse sequelae with subclinical infection at birth

| Sequelae | % |

|---|---|

| Chorioretinal lesions | 86 |

| Unilateral blindness | 81 |

| Bilateral blindness | 70 |

| Recurrent chorioretinitis | 60 |

| Severe, permanent neurologic sequelae | 33 |

| Mentally retarded | 14 |

| Sequentially lower IQ scores | 86 |

Only 11% of children were without any of these findings. IQ: intelligence quotient (data are from Wilson et al. 1980, with permission).

TABLE III.

A: Signs, symptoms and sequelae in congenital toxoplasmosis patients

| Frequency of occurence in infants with (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Signs and symptoms |

Neurologic diseasea n = 108 |

Generalized diseaseb n = 44 |

|

| Chorioretinitis | 94 | 66 | |

| Abnormal spinal fluid | 55 | 84 | |

| Anemia | 51 | 77 | |

| Convulsions | 50 | 18 | |

| Intracranial calcification | 50 | 4 | |

| Jaundice | 29 | 80 | |

| Hydrocephalus | 28 | 0 | |

| Fever | 25 | 77 | |

| Splenomegaly | 21 | 90 | |

| Lymphadenopathy | 17 | 68 | |

| Hepatomegaly | 17 | 77 | |

| Vomiting | 16 | 48 | |

| Microcephaly | 13 | 0 | |

| Diarrhea | 6 | 25 | |

| Cataracts | 5 | 0 | |

| Eosinophilia | 4 | 18 | |

| Abnormal bleeding | 3 | 18 | |

| Hypthermia | 2 | 20 | |

| Glaucoma | 2 | 0 | |

| Optic atrophy | 2 | 0 | |

| Microphthalmia | 2 | 0 | |

| Rash | 1 | 25 | |

| Pneumonitis | 0 | 41 | |

| B: Sequelae of congenital toxoplasmosis among 105 persons followed four years or more | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Neurologic n = 70 n(%) |

Generalized n = 31 n(%) |

Subclinical n = 4 n(%) |

| Mental retardation | 69 (98) | 25 (81) | 2 (50) |

| Convulsions | 58 (83) | 24 (77) | 2 (50) |

| Spasticity and palsies | 53 (76) | 18 (58) | 0 |

| Severely impaired vision | 48 (69) | 13 (42) | 0 |

| Hydrocephalus or | 31 (44) | 2 (6) | 0 |

| microcephaly | |||

| Deafness | 12 (17) | 3 (10) | 0 |

| Normal | 6 (9) | 5 (16) | 2 (50) |

Presenting manifestations (a) and sequelae of congenital toxoplasmosis at ≥ 4 years of age (b) when generalized or neurologic manifestations were present at birth and the child was not treated (data from Eichenwald 1960).

data are from Eichenwald 1960, with permission.

TABLE IV.

Incidence of transmission and severity of disease in each trimester

| Trimester of maternal acquisition |

Incidence of transmission (%) |

Relative severity of disease |

|---|---|---|

| I | 17 | severe |

| II | 25 | intermediate severity |

| III | 65 | milder or |

| asymptomatic |

data are from Desmonts & Couveur 1974b.

TABLE V.

Psychological data of matched pairs a by treatment [one month (mo)] status of infected infant

| Pair | Social age (mo) |

Mental age (mo) |

Social quotient |

IQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | ||||

| Meanb | 42.6 | 39.7 | 100.8 | 93.2 |

| (p < 0.02) | ||||

| Controls | 48.2 | 47.6 | 112.2 | 109.8 |

| Treated | ||||

| Mean | 39.6 | 40.1 | 120.0 | 121.0 |

| Controls | 38.4 | 38.6 | 115.3 | 116.0 |

statistical analysis of data of untreated infected infants and matched control subjects revealed significant differences only in intelligence quontient (IQ)

infected (data are from Saxon et al. 1973).

TABLE VI.

A: Prospective study of infants born to women who acquired Toxoplasma infection during pregnancy

| Finding | Examined n |

Positive n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Prematurity | 210 | |

| birth weight < 2500 g | 8 (3.8) | |

| birth weight 2500–3000 g | 5 (7.1) | |

| Dysmaturity (intrauterine growth retardation) | 13 (6.2) | |

| Postmaturity | 108 | 9 (8.3) |

| Icterus | 201 | 20 (10) |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | 210 | 9 (4.2) |

| Thrombocytopenic purpura | 210 | 3 (1.4) |

| Abnormal blood count (anemia, eosinophilia) | 102 | 9 (4.4) |

| Microcephaly | 210 | 11 (5.2) |

| Hydrocephalus | 210 | 8 (3.8) |

| Hypotonia | 210 | 2 (5.7) |

| Convulsions | 210 | 8 (3.8) |

| Psychomotor retardation | 210 | 11 (5.2) |

| Intracranial calcifications on radiography | 210 | 24 (11.4) |

| Abnormal ultrasound examination | 49 | 5 (10) |

| Abnormal computed tomography scan of brain | 13 | 11 (84) |

| Abnormal electroencephalographic result | 191 | 16 (8.3) |

| Abnormal cerebrospinal fluid | 163 | 56 (34.2) |

| Microphthalmia | 210 | 6 (2.8) |

| Strabismus | 210 | 11 (5.2) |

| Chorioretinitis | 210 | |

| unilateral | 34 (16.1) | |

| bilateral | 12 (5.7) |

| B: Findings at birth in 55 live infants born of 52 pregnancies with prenatal diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis | ||

|---|---|---|

| na | % | |

| Subclinical infection | 44/54 | 81 |

| Multiple intracranial calcifications | 5/54 | 9 |

| Single intracranial calcification | 2/54 | 4 |

| Chorioretinitis scar | 3/54 | 6 |

| Abnormal lumbar puncture | 1/54 | 2 |

| Evidence of infection on inoculation of placenta | 23/46 | 50 |

| Positive cord blood IgM antibody | 8/53 | 15 |

signs and symptoms in 210 infants with proven congenital infection (1949–1960). N: 300 (chorioretinitis: 76%; neurological disturbances: 51%; abnormal cranial volume: 21%; calcification: 32%) (data are adapted from Couvreur et al. 1984a, with permission).

numerator: number of abnormalities present at birth; denominator: total number of infants examined for abnormalities (data are from Hohlfeld et al. 1989, with permission).

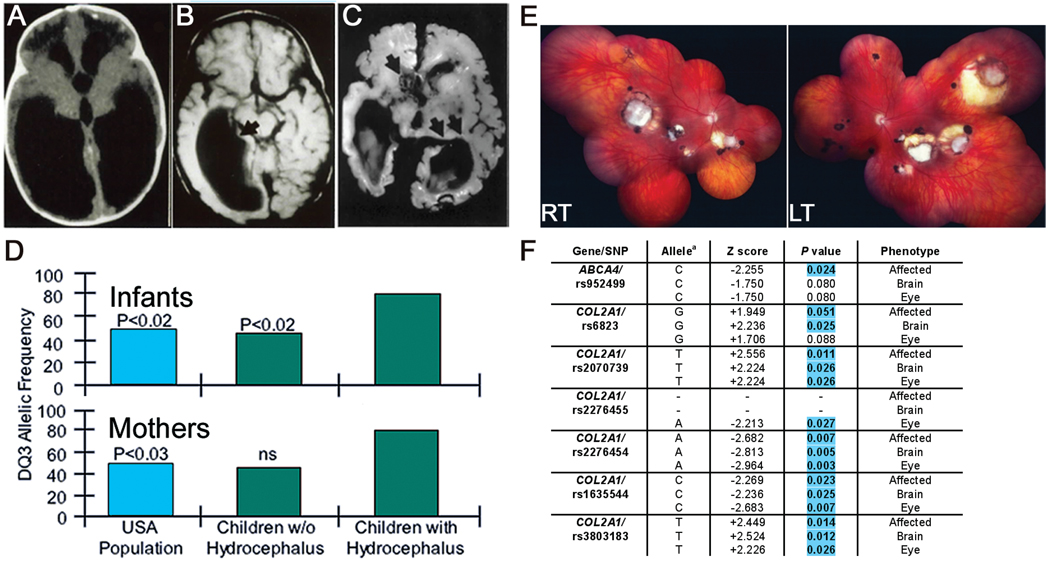

Fig. 5.

A–F: association of presence of hydrocephalous “shown in brain computed tomography and magnetic resonance image of brains of congenitally infected children” (A, B) and brain at pathologic examination showing characteristic periacqueductal inflammation and necrosis (C) with (D) presence of the HLA DQ3 gene in congenitally infected infants and mothers of the children (from Mack et al. 1999, with permission); E: retinal scars; F: association of alleles of Col2A and ABC4r with hydrocephalus and chorioretinal disease in toxoplasmosis and diagnosis; LT: left eye disease; RT: right eye, representative of eye disease (data adapted from Jamiesen et al. 2008, with permission).

Postnatal treatment of infants (in conjunction with treatment of 18 pregnant women and thus their fetuses) with congenital toxoplasmosis in the USA

There is a study of treatment of infants, including a phase 1 clinical trial and randomized controlled trial of a higher or lower dose of pyrimethamine with sulfadiazine for infants treated throughout the first year of life (Fig. 3) (McLeod et al. 1992, 2006b, McAuley et al. 1994, Boyer et al. 2005, 2008, Remington et al. 2006). This study indicates that outcomes are improved relative to those described for untreated persons and active disease becomes quiescent with treatment. There are not significant differences to date between the higher and lower dose regimens in either toxicity or early outcomes determined as pre-established endpoints (Fig. 3) (McLeod et al. 2006a). Severity of disease at birth of those in this study is comparable or more severe for those in the generalized/severe categories than manifestations in those described by Eichenwald (1960) (Fig. 4C).

Prenatal and postnatal treatment of congenital toxoplasmosis in France

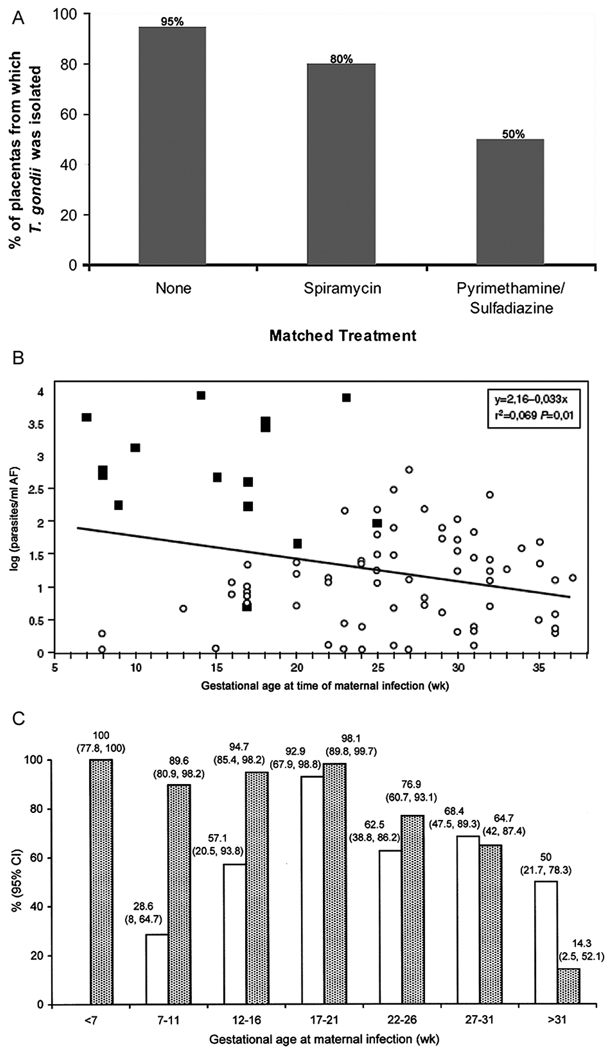

Carefully performed and rigorous studies conducted in France have demonstrated that treatment of the placenta and the fetus in utero by administering medicines to the mother (Fig. 6) reduces infection of the placenta (Fig. 7) and reduces manifestations of infection of the newborn infant and consequent brain and central retinal disease (Table VI–Table VIII) (Couvreur & Desmonts 1962, Couvreur et al. 1984b, 1985, Desmonts 1985, Daffos et al. 1988, Hohlfeld et al. 1989, Couvreur 1991, Couvreur et al. 1993, Foulon et al. 1994, 1999, Wallon et al. 1994, 2004, Peyron et al. 1996, Thulliez 2001, Binquet et al. 2003, Brézin et al. 2003, Berrebi et al. 2007, Kieffer et al. 2008). This approach developed as follows: Desmonts and Couvreur (1974a) demonstrated that without treatment, children who had been infected early in gestation had poor outcomes and that outcomes were of moderate severity in mid-gestational infections (Desmonts 1982, Couvreur et al. 1984b, 1985, Desmonts et al. 1985). A substantial proportion of infants (~ 50%) born to mothers who were infected late in gestation and who were examined carefully at birth had eye disease and/or intracerebral calcifications and meningitis (Couvreur & Desmonts 1962, Desmonts 1982, Couvreur et al. 1984b, Desmonts et al. 1985). In a subsequent decade, spiramycin treatment resulted in reduced rates of infection of the placenta (Fig. 7) (Couvreur et al. 1993). Without treatment it was possible to isolate the parasite from placentas for 95% of those who were infected. With spiramycin treatment, the ability to isolate the parasite from placenta was reduced to 80% (Fig. 7A). Coincident with the introduction of this treatment, the incidence of infected infants was noted to be 50% less in each trimester in the decade during which spiramycin treatment was used compared to the preceding decades when there was no treatment (Couvreur et al. 1984b, Daffos et al. 1988,Hohlfeld et al. 1989, Foulon et al. 1999, Thulliez 2001, Kodjikian 2006, Remington et al. 2006, Kieffer et al. 2008). The severity of disease at birth was also lower for infection acquired in each trimester, when determined in the decade when spiramycin was used compared with previous decades when there was no treatment. This is presumed to be due to delaying transmission from mother to fetus across the placenta, so that with delayed transmission infection becomes less severe, and not to treatment of the fetus (Table VII) (Desmonts 1982).

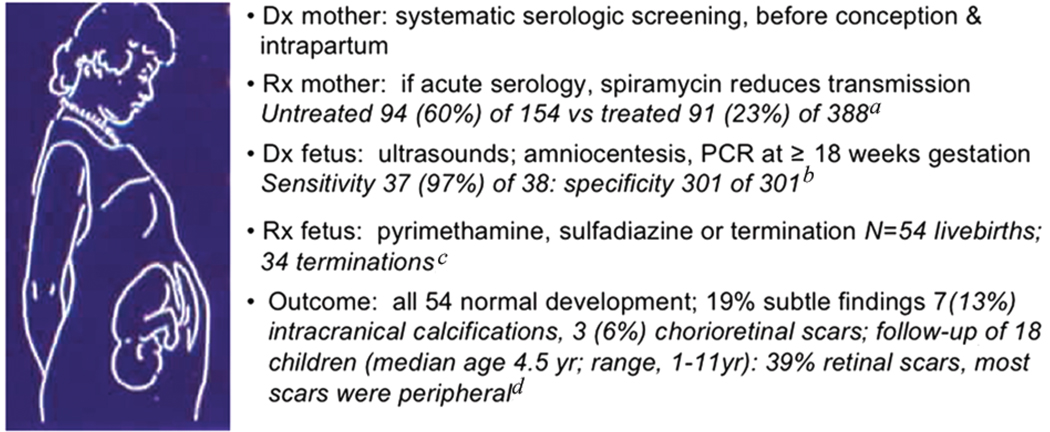

Fig. 6.

French approach to diagnosis and treatment of congenital toxoplasmosisin earlier decades and outcomes using this approach (from Boyer et al. 2008). a: from Desmonts & Courveur 1974a; b: from Hohlfeld et al. 1994a; c: from Daffos et al. 1988; d: from Hohlfeld et al. 1989, Brézin et al. 1993.

Fig. 7.

parasite isolation, treatment and outcome in congenital toxoplasmosis. A: reduction in isolation from placenta of infected infants following treatment with spiramycin, pyrimethamine/sulfadiazine versus (B) no treatment. Amniotic fluid (AF) parasite burden predicts severity of disease in congenital toxoplasmosis. Correlation between Toxoplasma concentrations in AF samples and gestational age at maternal infection for the 86 cases. Severity of the infection is represented in each case by ■ if severe signs of infection were recorded or by ○ if no or mild signs were observed. In general, the earlier the mother is infected, the higher the parasite numbers in AF. Some babies who had relatively low numbers of parasites were severely infected and many babies who had relatively high numbers of parasites were not severely infected (data from Romand et al. 2004, with permission); C: prenatal diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on AF according to gestational age at maternal infection. CI: confidence interval; shaded bars: negative predictive value of PCR on AF; unshaded bars: sensitivity of PCR on AF (Romand et al. 2001).

TABLE VIII.

A: Adjusted effect of the timing of prenatal treatment on the risk of mother-to-child transmission in European prenatal screening centers in subsample of treated mothers

| OR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Time of prenatal treatment initiation | 0.05 | |

| < 3 weeks after seroconversion (n = 312) | 0.48 (0.28–0.80) | |

| > 3 weeks and < 5 weeks after seroconversion (n = 442) | 0.64 (0.40–1.02) | |

| > 5 weeks and < 8 weeks after seroconversion (n = 360) | 0.60 (0.36–1.01) | |

| ≥ 8 weeks after seroconversion (n = 324) | Ref |

| B: Cumulative incidence rate at two years of age of first retinochoroiditis by category of risk factor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | Infants with rettinochoroiditis n/ total |

Cumulative incidence rate % |

p |

| Center | Lyon | 14/139 | 10.1 | 0.58 |

| Paris | 14/98 | 14.3 | ||

| Marseille | 8/63 | 12.7 | ||

| Sex | Male | 12/149 | 8.1 | 0.04 |

| Female | 25/151 | 15.6 | ||

| Calcifications | Present | 7/22 | 31.8 | 0.001 |

| Absent | 29/275 | 10.5 | ||

| Delay between maternal infection | < 4 wk | 19/162 | 11.7 | 0.053 |

| and first treatment | 4–8 wk | 9/105 | 8.6 | |

| > 8 wk | 8/33 | 24.2 | ||

| 11.6 | ||||

| C: Predictive factors for retinochoroiditis lesions during the two first years of life | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete m odel | Final model | ||||

| Variable | Hazard ratio |

p | Hazard ratio |

95% Confidence interval |

p |

| Gestational age at maternal seroconversion | 0.999 | 0.98 | |||

| Female gender | 2.01 | 0.054 | 2.02 | 1.01–4.1 | 0.049 |

| Cerebral calcifications | 4.2 | 0.003 | 4.3 | 11.9–10 | 0.0006 |

| Antenatal diagnosis versus diagnosis between birth and 3 mo | 1.18 | 0.36 | |||

| Diagnosis after age 3 mo versus diagnosis between birth and 3 mo | 0.44 | 0.18 | |||

| Delay between maternal seroconverstion and first treatment > 8 wk | 2.57 | 0.04 | 2.54 | 1.14–5.65 | 0.02 |

| D: Hazard ratios for age at first detection of retinochoroiditis and probability of retinochoroiditis by four years old according to pregnancy and infant characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Retinochoroiditis n |

Congenital toxoplasmosis n |

Hazard Ratio % (95% CI)a |

Probability of retinochoroiditis by 4 yr % (95% CI) |

| Region of study | ||||

| France (reference) | 26 | 171 | 1.0 | 16.2 (10.1–22.3) |

| Italy/Austria | 8 | 39 | 1.11 (0.45–2.74) | 18.9 (6.2–31.4) |

| Scandinavia/Poland | 16 | 71 | 0.76 (0.29–1.98) | 16.0 (7.3–24.8) |

| Prenatal treatment | ||||

| Treatment delay (treated women only) | ||||

| per wk of delay | 30 | 169 | 0.99 (0.87–1.12) | — |

| Treatment delay (versus no treatment) | ||||

| no treatment (reference) | 20 | 103 | 1.0 | 15.5 (8.2–22.7) |

| < 4 wk | 18 | 114 | 0.82 (0.38–1.79) | 15.6 (8.4–22.7) |

| ≥ 4 wk | 12 | 64 | 0.84 (0.32–2.20) | 15.6 (8.4–22.7) |

the primary analysis was based on 1,438 infected mothers who were treated during pregnancy (from 18 prenatal screening cohorts); 398 of their children were infected. The sooner prenatal treatment was started after seroconversion, the lower the adjusted odds of mother-to-child transmission [odds ration (OR) 0.94 per week, 95% CI 0.90–0.98]. Compared with mothers treated after 8 weeks of seroconversion (upper quartile of delay from seroconversion), mothers treated earlier tended to have a lower odds of mother-to-child transmission, particularly if prenatal treatment was initiated within 3 weeks after seroconversion (from SYROCOT et al. 2007, with permission).

results of univariate analysis (Log-Rank Test); mo: months; wk; weeks (from Kieffer et al. 2008, with permission).

results of multivariate analysis (Cox Model); mo: months; wk; weeks (data are from Kieffer et al. 2008, with permission).

data were adjusted for gestational age at maternal seroconversion

Hazard ratios show an effect that is statistically significant at the 59% level. Conclusion: “Prenatal treatment did not reduce risk of retinochoroiditis in European cohort. Low risk may not justify postnatal treatment.” (from Freeman et al, 2008, with permission).

TABLE VII.

A: Outcome of in utero treatment of congenitally infected fetuses with spiramycin or spiramycin followed by pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine

|

In Utero treatment |

Patients n |

Dates of study |

Dates of maternal infectiona |

Duration of follow-up |

Isolates from placenta n (%) |

Immune load of IgG |

IgM prevalence n (%) |

Subclinical infections n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| at birth | at 6 mo | ||||||||

| Spiramycin | 51 | 1972–1982 | 1972–1982 | 46.7 mo | 23/30 | 139 | 137 | 18/26 | 17/51 |

| (2mo-11yr) | (77) | (69) | (33) | ||||||

| Spiramycin + | 52 | 1983–1989 | 1983–1989 | 76wk | 16/38b | 86 | 70 | 8/46 | 30/52 |

| Pyrimethamine + | (11–46wk) | (42) | (17)c | (57) | |||||

| Sulfadiazine | |||||||||

| B: Transmission of Toxoplasma gondii infection to fetus, appearance of sequelae and severity of sequelae according to whether prenatal antibiotic therapy was given | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers n |

Time of infection (wk) | Transmission | Global sequelaea | Severe sequelaea | |||||

| Mean | Range | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Prenatal treatment | 119a | 18.7 | 3–34 | 46 | 38.7 | 12 | 10 | 4 | 3.5 |

| No prenatal treatment | 25 | 29 | 6–38 | 18 | 72b | 7 | 28c | 5 | 20d |

| Total | 144 | 20.5 | 3–38 | 64 | 44 | 19 | 13 | 9 | 6 |

weeks of gestation

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

mo: months; wk: weeks; yr: years (adapted from Couvreur et al. 1993).

four aborted fetuses are not included in the assessment of sequelae in the treated group

p > 0.05, by multivariate analysis and controlled for gestational age

p = 0.026, by multivariate analysis and controlled for gestational age

p = 0.007, by multivariate analysis and controlled for gestational age

wk: weeks (adapted rom Foulon et al. 1999).

Hohlfeld et al. (1989, 1994a) and Foulon (1994, 1999) performed elegant, careful and groundbreaking studies. They found that infection could be diagnosed by fetal blood sampling (which is more difficult and not used as the procedure of choice any longer) or amniocentesis and PCR to detect the presence of T. gondii genes in amniotic fluid. Subsequent studies have shown more severe disease with higher parasite burden in amniotic fluid (Fig. 7B) (Romand et al. 2004). Additionally, they found that when a pregnant woman was treated with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine, presumably treating infection in the placenta and the fetus in utero, it was possible to isolate parasites from the placenta of 50% of those so treated and definitely infected, contrasted with 95% of those who had not received any treatment in prior decades (Fig. 7A). Infants who were definitely infected, but whose mothers had received pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine, had markedly reduced severity of disease and manifestations of infections such as meningitis and serum IgM antibody to T. gondii in the newborn infant were present only very rarely (Table VII A, B, Fig. 6) (Daffos et al. 1988, Hohlfeld et al. 1989, Thulliez 2001, Brézin et al. 2003, Boyer et al. 2008).

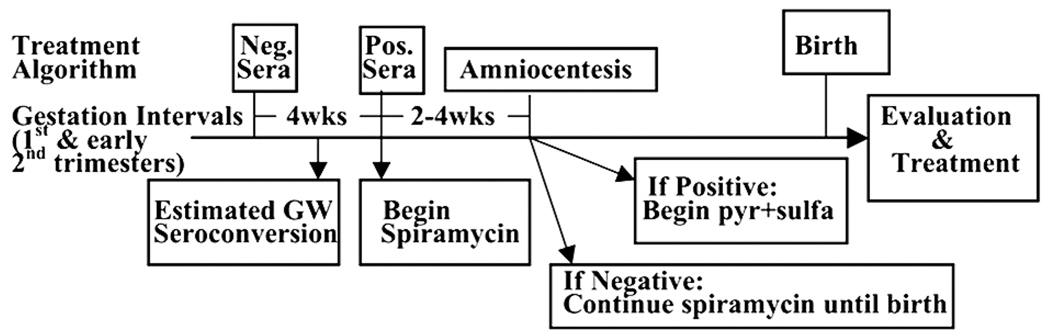

This algorithm (Fig. 6, Fig. 8) for treatment of infection initially included termination of pregnancies in which infection was acquired early in the first trimester and the fetus was severely involved. These measures were taken at the time since the potential teratrogenic effects of administration of pyrimethamine in the first trimester precluded its use during the first 12 weeks of gestation and gestational age precluded attempts to sustain extra-uterine life at those early gestational ages. Termination of pregnancies in which there were early gestation infections likely also contributed slightly to there being fewer severely involved infants, but would not have accounted for the markedly improved outcome of the substantial numbers of fetuses infected in mid-gestation who were normal or near normal at birth (Table VI, Table VIII, Table X). Specifically in France, there are between five and 13 terminations of pregnancies due to congenital toxoplasmosis each year (http://www.agence-biomedecine.fr/annexes/bilan2007/diag/1_diag_prenat/1_1/1_synthese.htm) (Table X). There are approximately 300–400 cases of congential toxoplasmosis per year with approximately 40–50 of those each year that are first trimester infections. Thus there might be a maximum of ~ 2.8% (~ 10/~ 350) improvement in outcomes secondary to termination of pregnancies which might influence results very slightly. This small percentage does not account for the marked improvement in outcomes.

Fig. 8.

Parisian algorithm for diagnosis and treatment of congenital toxoplasmosis for those children for whom there are data in Fig. 9. wk: weeks.

TABLE X.

Comparison with historical controls (1972–1981) of outcome of live-born infants diagnosed with congential Toxoplasma infection in a study of prenatal diagnosis (1982–1988) in which the mothers were treated with a regimen of pyrimethamine-sulfadiazine alternated with spiramycin

| Affected infants | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First trimester | Second trimester | Third trimester | ||||||||||

| 1972–1981 | 1982–1988 | 1972–1981 | 1982–1988 | 1972–1981 | 1982–1988 | |||||||

| Outcome | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| Subclinical | 1 | 10 | 6 | 67 | 23 | 37 | 33 | 77 | 74 | 68 | 2 | |

| Benign | 5 | 50 | 2 | 22 | 28 | 45 | 10 | 23 | 31 | 29 | 0 | |

| Severe | 4 | 40 | 1 | 11 | 11 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| Total | 10 | 9 | 62 | 43 | 108 | 2 | ||||||

adapted from Hohlfeld et al. 1989, with permission.

Foulon et al. (1994, 1999) work merits further detailed discussion. In this study, 149 consecutive pregnant women with T. gondii antibody seroconversion from five European university medical centers, i.e. medical centers in Oslo (Norway), Helsinki (Finland), Brussels (Belgium), Reims (France) and Lille (France) were studied. One hundred forty-four of these evaluations were completed through one year after the infected infants’ birth and included in the data analysis. In this study there was a significant reduction of sequelae due to this prenatal therapy in congenitally infected infants (p = 0.026) and prenatal therapy significantly prevented development of severe sequelae in these infants (p = 0.007) (Table VII B). Additionally, when treatment was initiated earlier, decreasing the amount of elapsed time between infection and the administration of anti-parasitic medicines, sequelae were found in the infected child less often (p = 0.021).

Contrast of approaches to diagnosis, treatment and outcomes of congenital toxoplasmosis in France and the USA

In France, where this algorithm (Fig. 6, Fig. 8) for diagnosis and treatment is used, it is extremely rare to see children with clinically significant, adverse consequences due to this congenital infection any longer (Fig. 6, Fig. 9, Fig. 10, Table VII–Table X). This is not true in the USA, however, where obstetrical screening for this acute acquired infection is not performed routinely, or is performed in a less standardized manner, and where children whose mothers have not been treated during gestation present with severe infection at birth (McAuley et al. 1994, McLeod et al. 2006a). The actual incidence of congenital T. gondii infection in the USA is not known since this is not a reportable disease in the USA. Serologic screening of pregnant women for acquisition of T. gondii for the first time during gestation, which is when congenital infection occurs, in the USA is at present dependent on patient and obstetrician preference. Recently, practice guidelines for obstetric screening and treatment of congenital toxoplasmosis have been published (Montoya & Remington 2008) and these practice guidelines may influence clinical practice patterns in North America in the future. In Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Vermont, where a test which detects about 50% of infected infants is used, an incidence of ~ 1/5,000 births is estimated and approximately 40% of those infants already have significant brain or eye involvement at birth (Guerina et al. 1994, Lynfield et al. 1999).

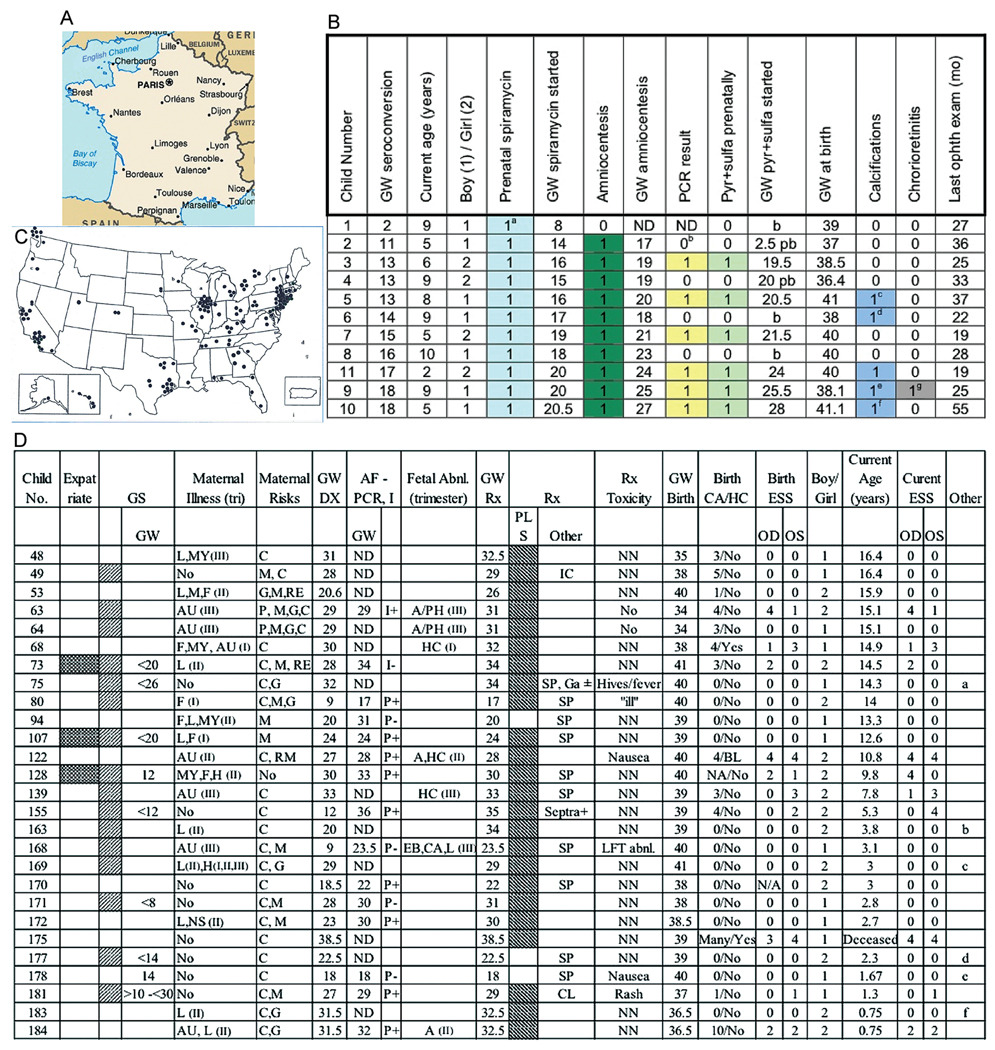

Fig. 9.

A–D: Outcomes of Parisian and U.S. children. (A) Map of France: Serologic screening of French mothers and children was in Paris; (B) Outcomes for Parisian children born to mothers who acquired their infection in the first or early second trimesters and who were treated in utero. a: Spiramycin prenatally for only one month; b: For the children with negative amniocentesis, three had specific IgM at birth. The remaining two had rising specific IgG titers. c: Two very small (1–2mm) calcifications on brain ultrasound; d: Left parietal macrocalcifcations with a porencephalic cavity (brain ultrasound only); e: One small right parietal calcification on brain ultrasound; f: Three large left parietal and 1 left frontal calcifications (antenatal MRI, neonatal ultrasound, and brain computed tomography); severe speech delay. This child experienced the longest time between diagnosis of maternal infection and treatment (10 weeks compared to 6–7 weeks). The dark box indicates that this child had more severe symptoms; g: Two peripheral retinal scars 2 disc diameters, 1 disc diameter; visual acuity normal; GW = gestational week; b = birth; pb = weeks post birth; ND = not done Note that none of the children had hydrocephalus in utero (data of Philippe Thulliez, Ph.D., and François Kieffer, M.D., Institute de Puericulture, Paris, France, September, 2007); (C) Birthplaces of all children in NCCCTS. Each circle is birthplace of a child; (D) Findings for USA patients diagnosed or suspected to have congenital toxoplasmosis while in utero and treated. Abbreviations and definitions: Checker board shading= Yes, a French Expatriate; Diagonal Lines pointing left= Routine Screen; Screen refers to any systematic serologic testing. GW = Gestational week. For French expatriates this is monthly, often beginning pre-conception. In the US this varies with obstetrician preference. Most often it is once at the first pre-natal visit and once late in gestation, unless symptoms intervene. Time of latest negative serum (LNS) is indicated when these data are available. Maternal Illness: F = Fever; L = Lymphadenopathy; MY = Myalgia; A = Asthenia; AU= Abnormal Fetal Ultrasound; H=Headache; NS=Night Sweats; TRI=trimester; Risk Factors: M = Raw/Undercooked Meat; C = Significant Cat Exposure; RM = Raw Milk; G = Gardening; P = Pica; RE=Raw Eggs; GW=Weeks of gestation; Dx=diagnosis; AF=Amniotic Fluid; I= Isolation; ND=Not Done; Clinical Findings in Fetus or Infant: A=ascites; PH = Polyhydramnios; HC=Hydrocephalus; CA=Calcification; BL=Brain Lesion; EB=Hyperechogenic bowel; GS= Gestational Serology Rx: Treatment; Medication: PLS = Pyrimethamine, Leukovorin, Sulfadiazine, shaded box indicates patient received this treatment; SP = Spiramycin; CL = Clindamycin; Ga = Gantrisin (in error); ± Ga initially given in error, eventually switched to P; Septra+ taken from 12–16 GW; Rx Toxicity: NN= not noted; LFT= Liver Function Test; Findings in Infant or Child: NA=Not available; OD= Right Eye; OS=Left Eye; ESS=Eye Severity Score: 0=normal vision; 1=normal vision, nonmacular lesions; 2=normal vision, macular lesions; 3=impaired vision, nonmacular lesions; 4=impaired vision, macular lesions; No. 128 CT was poor quality; No 170 mother was non-compliant with meds. It is estimated that 170 mothers received a total of about 2 weeks of treatment; there were no new central lesions found in any of the patients who were treated in utero. However, a peripheral lesion was noted for the first time in No 63 at age 3.5 years. No. 49 and 122 have not returned for follow-up visits. There was clinical evidence (serologic LFT abnormality or other) for infection in all these children with the exception of 4 children from whom additional information is pending. Boy/Girl: 1=Boy; 2=Girl; Other: Diagnosis for these infants was suspected and they were treated. In these children, diagnosis was likely but not established unequivocally. Reasons for diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis are as follows: a= Mother had acutely acquired toxoplasmosis with a rising IgG titer in the 3rd trimester (IgG 4096, IgM 4.9, IgA 5.4, ACHS > 1600/3200). Infant had hepatomegaly (liver edge 3 cm below right costal margin [RCM]), mild IUGR, CBC had 7% atypical lymphocytes, and there was a slight increase in SGOT(66). Additionally, the infant’s serum had T. gondii specific IgA(IgM ELISA was 2.4).; b= Infant’s mother was seronegative at week 13, but developed adenopathy several weeks later. At the 20th week of gestation, the mother had serologies consistent with acute acquired toxoplasmosis and was treated with Pyrimethamine, Leukovorin, and Sulfadiazine until term. The infant was normal at birth, therefore, her infection status is unknown.; c= Mother was seronegative at 12 weeks of gestation, however, at 17 weeks of gestation, she developed lymphadenopathy and headaches. At approximately 28 weeks of gestation she had serologies consistent with acute, acquired toxoplasmosis, and was treated with Pyrimethamine, Leukovorin, and Sulfadiazine. The infant’s liver was down 2 fingerbreadths below the right costal margin, CSF WBC 53/mm3 (u/n 22), RBC 30/mm3, protein 192 mg/dl. In addition, the infant’s AST(42) and ALT(36) were slightly elevated with 0–31 being the normal range for both. Also, her serum IgA specific for T. gondii was 1.1 and a faint hyperpigmented area was noted in right macula~7 weeks after birth.; d= Mother, who is a veterinarian, was found to be acutely infected at 14.3 weeks of gestation. Infant’s CBC had 6 atypical lymphocytes, 7 eosinophils, SGPT of 73 was elevated (normal range of 21–58), and SGOT of 73 was also elevated (14–36). Infant Toxoplasma serologies were negative, however, and no placental subinoculation was preformed; e= After 14 weeks of gestation, mother was acutely infected (IgG 2048, IgM 3.5, AC/HS 800/800, Amniotic fluid PCR was −.). The infant had retinal hemorrhages without any known birth trauma. His CSF had 650 WBC/mm3 (mostly lymphocytes), RBC 1950/mm3, protein 164mg/dl, and glucose of 34 mg/dl.; f= Ultrasound at 28 weeks revealed that the infant’s twin had ascites. At 32 weeks of gestation, the mother’s serology was consistent with acute, acquired T. gondii infection. Twin’s infection is confirmed. No placental subinoculations were performed. While her serologies were negative, her AST was elevated at 76.

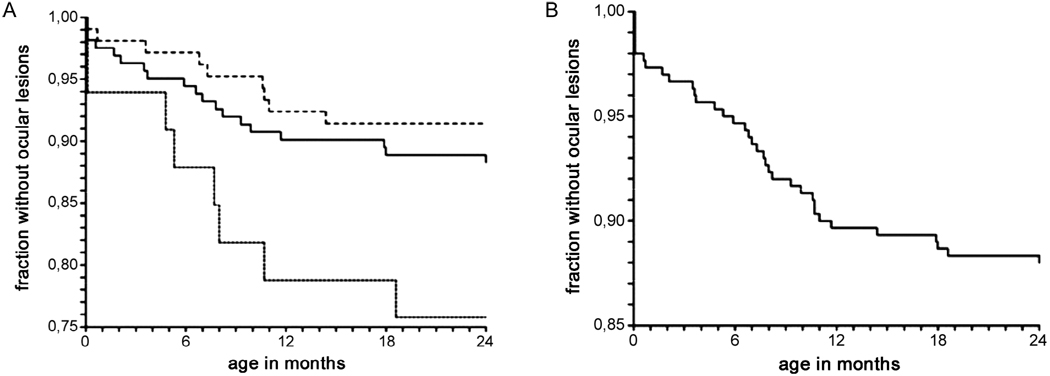

Fig. 10.

A. new eye lesions in children who had < 8 or ≥ 8 weeks delay from diagnosis in utero to treatment. Kaplan-Meier plots showing the age at diagnosis of a first retinochoroiditis according to the delay between maternal infection and first treatment; < 4 weeks (solid line), 4–8 weeks (dashed line) and > 8 weeks (dotted line) (from Kieffer et al. 2008, with permission); B: Kaplan-Meier estimate of the age at diagnosis of a first retino-choroiditis during the first two years of life among 300 infants (Kieffer et al. 2008, with permission).

Binquet et al. (2003), Kodjikian (2006), Mcleod et al. (2006a) and Phan et al. (2008a, b) have described favorable outcomes with relatively low incidence of recurrent or new eye disease in their early years for infants treated during the first year of life. In the latter study, mean age was 10.4 years old for children treated in utero and/or throughout their first year of life (McAuley et al. 1994, McLeod et al. 2006a). These latter results were found in a treatment trial that included a phase 1 study demonstrating feasibility of treatment, efficacy and early lack of toxicity, followed by a randomized controlled trial that included treatment with a lower and higher dose of pyrimethamine (Fig. 3). The data from this longitudinal follow-up study of new ocular lesions in congenitally infected persons treated in infancy and a cohort of children who had not been treated in infancy are in Fig. 4D, E. There is a sharp contrast in new eye lesions between the treated and untreated children, but this could be due to differences in the patient populations. Although the children who were not treated had milder involvement at birth, genetics of the parasites in each cohort could differ and genetics of host and parasite infecting those in the cohort currently are being studied (R McLeod, unpublished observations).

Brézin et al. (2003) described ophthalmologic outcomes when there was maternal and post-natal anti-Toxoplasma treatment in cases in which a prenatal diagnosis of toxoplasmosis was made. Data were collected in a collaborative study in Chicago where the same examiners first evaluated USA children together and then evaluated a cohort in Paris (Brézin et al. 2003). Following a visit of the Parisian ophthalmologist to Chicago and examining National Collaborative Chicago-based Congenital Toxoplasmosis Study (NCCCTS) children (Brézin et al. 2003) together, 18 Parisian children with congenital toxoplasmosis were examined. Only cases with acquisition of maternal infection during the first half of pregnancy were included. Disease was first suspected when seroconversion of the mother occurred as routinely monitored pre-conception and each month during gestation in France. Toxoplasma infection of the fetus was confirmed by fetal blood or amniotic fluid analysis. Mothers were treated by an alternating regimen of pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine and spiramycin until delivery. Anti-toxoplasmic treatment in children was initiated at birth and continued for duration of 12 months in most cases. Median age of children at follow-up was 4.5 years (range 1–11). No lesions were found in either eye in 11 (61%) of 18 of children. Unilateral and bilateral chorioretinal scars were observed in three (17%) of 18 and in four (22%) of 18 cases respectively, or seven (39%) of 18 cases total; two children had ocular lesions at birth. Only one case of bilateral macular lesions with severe visual impairment was seen. Localization of scars was peripheral only, five eyes, posterior pole nonfoveal, three eyes, foveal or juxtafoveal, three eyes. In utero diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis allowed early therapy. Results suggest that prenatal treatment decreases frequency and severity of chorioretinal lesions compared to treatment administered only after birth.

Recently, there was a report of favorable outcomes, even for those infected early in gestation who did not have hydrocephalous, when the pregnant woman was treated with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine. In this report, Wallon et al. 1994 documented that in the absence of hydrocephalous and with treatment with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine, even fetuses infected early in gestation have been normal or near normal at birth (Berrebi et al. 1994, 2007).

There have been a variety of multi-center studies grouping and comparing different patients and approaches to try to establish whether there is any benefit of treatment (Dunn et al. 1999, Gilbert et al. 2001, Gras et al. 2001). A recent study suggested that shorter time between diagnosis and initiation of anti-Toxoplasma medicines led to better outcomes (Table VIII) (Wallon et al. 1994). Meta-analyses have not so far provided other definitive proof of efficacy, but have led some of those describing such studies to call for double blind, placebo controlled, randomized trials (RCTs) (Gilbert et al. 2001, Gras et al. 2001, Freeman et al. 2008). There is an interesting contrast in two recent reports: the same cohorts that were part of those diagnosed, treated, and the data analyzed in larger multi-group study were analyzed and described separately as results from three single centers where the methods of diagnosis and approaches to treatment were more uniform. The results from the larger grouped cohort and the results in three of the centers considered separately differed and led to different conclusions (Table VIII B, C) (Freeman et al. 2008, Kieffer et al. 2008). This experience illustrates that variations in approaches to diagnosis and treatment in large, grouped, multi-center studies in which outcomes for centers are combined and meta-analyses performed (Gilbert et al. 2003, Gras et al. 2005, Freeman et al. 2008) may obscure significant findings identified from rigorous, separate studies that are part of these larger combined analyses. Freeman et al. (2008), in their analysis of the larger European cohort, which included the three centers also analyzed separately, concluded that prenatal treatment was not effective in decreasing the incidence of retinochoroiditis. However, when data from 129 of 281 of the patients that were included in the Freeman analysis, were analyzed separately from the three French centers that provided care, it was found that, “a delay of > 8 weeks between maternal seroconversion and the beginning of treatment is a risk factor for retinochoroiditis detected during the first two years of life in infants treated for congenital toxoplasmosis” (Fig. 10A, B, Table VIII B, C) (Freeman et al. 2008, Kieffer et al. 2008). Although both published their studies in 2008, the times the cohorts were studied differed. The Freeman et al. (2008) study data, although this was not specified in the manuscript, are derived from evaluations of infants born between 1996–2000 (Kieffer, personal communication) and the Kieffer et al. (2008) data are derived from evaluations of infants born between 1996–2002, thus including additional children and is based on data from fewer centers. Thus the comparison herein which results in different conclusions is between two published sets of data that are not identical with respect to the children included which could also contribute to the different conclusions. In Table I within the Freeman et al. (2008) study it also is important to note that the column “Age at last ophthalmologic examination” lists a minimum age of 0. Some children, the number is not specified, had only one ophthalmologic examination at birth. Depending on the number of such children, it could impact substantially the results reported. This contrasts with the study of Kieffer et al. (2008) in which repeated examinations were the rule.

Randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter studies also can be confounded by differences in methods of diagnosis, treatment, evaluation and analysis at different sites. Similarly, mail questionnaires or phone interviews for parents concerning behavior, cognition and other neurologic findings, especially of young children (Freeman et al. 2005, Salt et al. 2005) might be subject to reporting biases of parents.

An analysis by Gras et al. (2001), using coalesced cohorts did not reveal a statistically significant improvement in outcomes for those whose mothers received treatment while they were in utero. The authors also discussed meta-analysis of all the studies of efficacy of prenatal treatment for congenital toxoplasmosis and concluded that they were insufficient to prove that treatment benefits outcomes of congenital toxoplasmosis. They felt that the current data necessitated additional placebo controlled studies. Thulliez (2001) provided a commentary about the reports (Gilbert et al. 2001, Gras et al. 2001) of lack of efficacy of treatment when evaluating these coalesced cohorts and noted certain issues in the design of the work. Thulliez (2001) pointed out, however, that the study design (Gras et al. 2001) was suboptimal. In contrast, he and others (Thulliez 2001, Remington et al. 2006) have concluded that there have been a sufficient number of rigorous and carefully performed studies supporting efficacy and, thus, randomized, double blind, placebo control studies to further prove this would potentially be detrimental to the health of affected individuals. These latter authors (Thulliez 2001, Remington et al. 2006) note that within the aforementioned coalesced study, the untreated, non-randomized, control group was small relative to the treatment groups [22 (12%) of 181] (Gilbert et al. 2001). Further, it was noted (Thulliez 2001) that in this study (Gilbert et al. 2001) a disproportionate number of the untreated women acquired toxoplasmosis during their third trimester of pregnancy whereas the majority of women who received treatment were infected during their first trimester when clinical signs in the newborn will be more severe. Additionally, since this investigation (Gilbert et al. 2001) was conducted when mouse-inoculation was the standard for diagnosing congenital infection, treatment was delayed. On average, the time interval between seroconversion and when treatment was started in the Gilbert et al. (2001) work spanned seven weeks for treatment with pyrimethamine-sulfadiazine and four weeks when spiramycin was administered alone since test results took three-six weeks to receive and were confirmed before any therapeutic regimen was implemented. Currently, PCR of amniotic fluid is the standard diagnostic test that can determine acquisition of T. gondii within one day to allow early initiation of treatment (Romand et al. 2004). Moreover, the investigators (Gilbert et al. 2001) use of pyrimethamine-sulfadiazine in conjunction with spiramycin when a positive fetal test was present is no longer the standard of care since spiramycin is unable to cross the placenta and can only prevent vertical transmission of T. gondii and not treat the infection (Leport et al. 1986, Remington et al. 2006).

New data concerning approaches to and outcomes associated with diagnosis and treatment in early gestation in France and diagnosis and treatment during gestation in the USA

New data are presented to demonstrate representative outcomes with an approach to diagnosis and treatment developed and utilized during the past two decades in Paris (Table VIII, Table X, Fig. 6, Fig. 8, Fig. 9) in which a subset of children born to mothers who were treated during early gestation have done well. In addition, the first patients whose mothers were treated while they were in utero as well as in the first year of life who have been evaluated by the NCCCTS are now 14 years old. Approaches in the USA are less well standardized, but these USA children present an example of how the French algorithm has been applied in North America during the past one and a half decades and outcomes with variations of this approach (Fig. 9).

Paris

A recent experience in Paris is informative and confirms the earlier results of Berrebi et al. (1994, 2007). Compared to outcomes when there was no treatment of early gestation infections, these infants have few or no apparent sequelae of infection. In their data from Paris (Fig. 9), it is remarkable that all but one of 11 children whose mothers were infected early in the first or second trimester and did not have hydrocephalous have no chorioretinal scars and in the one child with such scars, the scars are peripheral rather than central.

This contrasts markedly with ~ 75% symptomatic children who were not diagnosed in utero in the NCCCTS cohort. They were diagnosed at birth when they presented with clinically significant retinal scars (Mets et al. 1996). The absence of symptoms in these Parisian children (Table VI B) also presents a striking contrast to the much higher frequency of symptomatic newborns described by the Parisian group when there was no treatment given during gestation in earlier decades, 76% of whom had chorioretinal disease (Table VI–Table X) (Couvreur et al. 1984b).

The absence of symptoms in those infants in the Parisian cohort who had positive amniotic fluid PCR and who were treated with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine, in contrast to those whose amniotic fluid PCR did not have T. gondii DNA and who were treated with spiramycin alone is remarkable. This suggests that fetuses with T. gondii detected in their amniotic fluid by PCR were largely, successfully treated and that the fetuses who did not have T. gondii detected in their amniotic fluid either had delayed transmission secondary to spiramycin treatment of the pregnant woman and/or were born to genetically resistant mothers or were themselves genetically resistant.

USA

In the USA, maternal and neonatal screening are only rarely approached in a standardized manner. Most physicians do not screen to detect acquisition of T. gondii during gestation, or to detect congenital T. gondii infection in the newborn. Massachusetts and New Hampshire are the only states that screen all newborns in their newborn screening programs (Guerina et al. 1994, Lynfield et al. 1999) and no state currently mandates serologic screening for pregnant women during gestation as occurs in France.

Practice guidelines, outlining an approach (Montoya & Remington 2008), and the published outcomes associated with gestational and neonatal screening (Hohlfeld 1989, Hohlfeld et al. 1994b, Kieffer et al. 2008) and the analyses reported herein may modify approaches to diagnosis and treatment of congenital toxoplasmosis in the USA in the future.

Most children who have been diagnosed with congenital toxoplasmosis in the newborn period and treated in conjunction with a collaborative study (NCCCTS) in the USA were not diagnosed in utero and have presented with significant disease at birth. Seventy-five percent Mets et al. 1996) of these children who were not treated in utero have had substantial eye disease at birth indicating that considerable damage had already occurred prior to presentation in the newborn period. This current USA standard of care contrasts markedly with that in France as described above, where severe disease, which is not uncommonly seen in the USA, is now only very rarely encountered (Couvreur, Kieffer, Thulliez and Wallon, personal communications). This change in outcomes in France occurred when the new algorithm for screening and treatment was initiated (Desmonts and Couvreur, personal communications).

More recently in the USA, diagnosis of acute acquired infection in the mother with transmission to the fetus and treatment appear to be carried out more frequently than in earlier years, but this practice is still uncommon. In a USA cohort of ~ 150 treated children diagnosed before or in the first months of life (McLeod et al. 2006a), there are 12 children under 3.8 years old and 15 children (3 diagnosed while living in France) who now are between 5.3–14 years old whose mothers received treatment while they were in utero. There were no children whose mothers were treated while they were in utero prior to 1993 (McAuley et al. 1994) with only a small increase in such fetuses and children within recent years (Fig. 9). The variability in approach in the USA is shown in Fig. 9C, D, where diagnosis has followed reported illness in the mother, report of risk factors for acquisition of T. gondii, abnormality in a fetal ultrasound consistent with congenital toxoplasmosis and/or in a subset due to systematic prenatal screening, sometimes secondary to residence in France and sometimes due to obstetrician practice or patient preferences. For completeness, Fig. 9 includes five children who were first treated when they were fetuses although the diagnosis was not firmly established. They were treated because there was sufficient probability of congenital infection due to the time in gestation that the mother was diagnosed and due to the sensitivity and specificity of available tests (Table IV, Fig. 7C), that parents and physicians felt there was less risk in prompt treatment than in deferring initiation of treatment to the time the infant was born and diagnosis might be definitively established. Treatment while in utero can reduce the manifestations at birth, therefore complicating diagnosis (Fig. 6, Table VI B) (Hohlfeld et al. 1989).

The outcomes for those in the NCCCTS diagnosed and treated in utero also are shown in Fig. 9D. Although approaches to diagnosis and treatment of pregnant women are not well standardized within the USA, as they are in Paris, and three of these children are French expatriates treated according to the French algorithms, the clinical findings in these USA children whose mothers were treated while they were in utero contrast with and are better than the results for the whole cohort of USA children diagnosed at or shortly after birth. These latter infants were often symptomatic and not infrequently had substantial generalized and/or neurologic involvement at birth (McAuley et al. 1994, McLeod et al. 2006a).

Despite the lack of standardization in approaches, the experience in the USA NCCCTS to date (Fig. 9C, D) suggests that in a small cohort that this approach of treatment with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine during gestation was feasible and safe. Further, it appears that this approach can result in quite favorable outcomes for those children whose mothers are treated while they are in utero.

Outcomes for these children who were treated in utero contrasts favorably with the findings of the group of USA children as a whole who were diagnosed after birth, in the first 2.5 months of life. Nonetheless, outcomes of the children diagnosed postnatally are more favorable than those for children with comparable initial illness, who were untreated or treated for only one month in infancy in earlier decades (Fig. 3) (McAuley et al. 1994, McLeod et al. 2006a). Overall outcomes appear to be considerably better than anticipated based on historical data (Eichenwald 1960, Saxon et al. 1973, Wilson et al. 1980, Koppe et al. 1986). There are better outcomes than in earlier literature for cognitive and motor function for more than two-thirds of the children. Nonetheless, without treatment during gestation there is more and worse eye disease at birth than in children whose mothers were treated during gestation in France (Brézin et al. 2003). Longitudinal follow up will allow assessment of whether the largely favorable outcomes are sustained into adolescence and adulthood without toxicity of such treatment. Data concerning incidence rates of follow-up of ophthalmologic findings in both an untreated and treated USA cohorts are shown in Fig. 4D (untreated) and in Fig. 4E (treated). It is likely that more prompt diagnosis and treatment (Table VII, Fig. 10A, B) in the context of systematic screening (Fig. 6, Fig. 8) will result in even better outcomes.

DISCUSSION

Congenital toxoplasmosis is an infection that destroys the brain and eye (Eichenwald 1960, Wilson et al. 1979, Foulon et al. 1999, Couvreur et al. 1984a, McAuley et al. 1994, McLeod et al. 2006a). French centers have provided state of the art care and an algorithm that optimizes outcomes for those suffering from this infection. In the USA, although not all children did well following treatment postnatally or prenatally and postnatally, the favorable outcomes we noted indicate the importance of diagnosis and treatment of infants with congenital toxoplasmosis. Nonetheless, approach to care of primary, acute acquired infection with this parasite during gestation in the USA remains largely unstandardized despite compelling data from centers in France which demonstrate the benefits of an approach aimed at early diagnosis and treatment. There are, however, children in the USA who have had favorable outcomes in the setting of the application of this, or a similar approach, to treatment of T. gondii infection in gestation.

The authors of this paper and the ethics boards of their institutions in both the USA and France have grappled with considerations of equipoise (i.e. consideration of the potential benefits and harm that could result from implementing different placebo and therapeutic regimens), especially with the recent attention drawn to the noteworthy absence of double blind, placebo controlled, RCTs for this disease (Gilbert et al. 2001, 2008, Gras et al. 2001, Freeman et al. 2008). All the authors of this present paper and institutional ethics boards appreciate the importance of perfect randomized, double blinded, placebo controlled trials. The approaches to prenatal and neonatal diagnosis and treatment of congenital toxoplasmosis outlined herein were developed before placebo controlled RCTs were standard for providing evidence based medicine approaches for treatment of many diseases. This was a time when the uniform and often devastating consequences of untreated congenital Toxoplasma infections were already well established. In the NCCCTS experience, the feasibility trial had dramatically different and improved results from those reported in every previous study of untreated children or those treated for one month. Thus, after review of all available data and deliberations including discussions between RMcLeod, P Meier, JS Remington, G. Desmonts, J Couvreur, ethics boards in Chicago, and review groups at the National Institutes of Health, it was concluded that ethical considerations and equipoise (Michels & Rothman 2003) prevented inclusion of a placebo group in the subsequent RCT. Thus in this RCT, there was randomization to a higher and lower pyrimethamine dose [i.e., change from daily to 3 times a week treatment with pyrimethamine at 2 (lower dose) or 6 (higher dose) months after initiation of treatment]. This design was to determine whether there might be a dose response in either efficacy or toxicity and if there were no major differences and outcomes were nonetheless improved from the poor outcomes in the literature, benefit would still be proven. Outcomes with earlier treatment of the mother during gestation with medicines that cross the placenta and that were continued through the first year of life appear to be even better than when treatment is initiated at birth (Couvreur & Desmonts 1964, Couvreur 1971, 1991, Desmonts 1982, 1985, 1987, Couvreur et al. 1984b, 1985, 1993, Desmonts & Couvreur 1984, Desmonts et al. 1985, Daffos et al. 1988, Hohlfeld et al. 1989, 1994b, Guerina et al. 1994, McAuley et al. 1994, Patel et al. 1996, Binquet et al. 2003, Brézin et al. 2003, Kodjikian et al. 2006, McLeod et al. 2006a, Remington et al. 2006, Berrebi et al. 2007, Kieffer et al. 2008, Garza et al. 2008, Montoya & Remington 2008).

At present, our review of available data and experience presented herein suggests that the logic and weight of the evidence indicating benefit and safety of currently available approaches still mitigates against placebo controlled trials and compels diagnosis and treatment of this disease with medicines known to be effective against the parasite. This is because without treatment there is destruction of the eye and brain with lifelong consequences and there also are substantial useful data concerning outcomes for untreated and treated persons. Some argue that even with favorable results in the past, a placebo-controlled study is still needed since earlier experience may be different from the current experience secondary to many variables. For example, the present may differ from the past due to variation in patient genetics (Mack et al. 1999, Jamiesen et al. 2008), populations, types of parasites (Gras et al. 2001, Lehman et al. 2006, Peyron et al. 2006) and different methods of diagnosis or treatment and evaluation and analyses. This logic, i.e., that the future may not resemble the past and thus a study is only valuable for the time in which it takes place, however then must apply even to the results of perfectly double-blinded, placebo controlled RCTs performed today and their relevance to subsequent treatments. This would be true even if all the parasite and host genetic factors, population and different diagnostic and therapeutic approaches that might differ had been defined and standardized. The argument that the present and future will not necessarily resemble the past, which of course is true, would apply even if there was a perfectly effective, completely non-toxic, medicine that eradicated all bradyzoites and tachyzoites, and there were resources to evaluate large groups of affected persons and their parents throughout their lifetimes.

It has also been argued that this parasite is a relatively infrequent cause of death and disability in newborn infants, children, otherwise immune-compromised persons and in persons with toxoplasmic uveitis and therefore is not a high public health priority in the developed world. The incidence of this infection varies by country and with time (Gomez-Marin et al. 1997, Grigg et al. 2001, Ajzenberg et al. 2002, Dubey et al. 2002, 2003, Portela et al. 2004, Lehman et al. 2006, Remington et al. 2006, Demar et al. 2007, Berger et al. 2008). In addition, since genetic variants of this organism have now been noted to cause severe multi-visceral disease and death in immune competent persons (Demar et al. 2007), since there is frequent diminished sight in individuals congenitally infected (Mets et al. 1996) and since a high prevalence and severe forms of this disease are being recognized in South America at the same time as globalization is increasing the risk of worldwide distribution of emerging diseases, perhaps T. gondii infection will become a higher public health priority. An emphasis on curing and preventing Toxoplasma infection would also occur if future research demonstrates that latent, chronic brain infection (which affects as many as one third to one half of all older children and adults worldwide from the time of acquisition throughout the rest of life) has undesirable consequences. Increasing the public health priority of treating and preventing Toxoplasma infection could provide an impetus to development of better medicines (i.e., those with effect on latent parasites and with less toxicity, less need for monitoring and less hypersensitivity) and vaccines to prevent this disease. Improved medicines and a vaccine would also benefit all those with primary infection during gestation and congenital toxoplasmosis throughout the world.

Currently available medicines are limited by hypersensitivity and toxicity (Zitelli et al. 1987, Trenque et al. 1998, McLeod et al. 2006b) are not manufactured as pediatric formulations and do not treat the latent bradyzoite form of the organism. Development of a safe, non-toxic, medicine effective against tachyzoites and bradyzoites that cures the infection with brief treatment in a phase I clinical trial would provide a compelling reason for a new comparative RCT of the current approach and this potentially optimal new medicine. Unfortunately, such a medicine has not yet been discovered/developed. Ideally, there would be medicines available that can cure this infection definitively with less toxicity and short treatment courses. Vaccine development to prevent this disease is also needed.