Abstract

Prenatal viral infection has been associated with development of schizophrenia and autism. Our laboratory has previously shown that viral infection causes deleterious effects on brain structure and function in mouse offspring following late first trimester (E9) and late second trimester (E18) administration of influenza virus. We hypothesized that middle second trimester infection (E16) in mice may lead to a different pattern of brain gene expression and structural defects in the developing offspring. C57BL6J mice were infected on E16 with a sublethal dose of human influenza virus or sham-infected using vehicle solution. Male offspring of the infected mice were collected at P0, P14, P35 and P56, their brains removed and cerebella dissected and flash frozen. Microarray, DTI and MRI scanning, as well as qRT-PCR and western blotting analyses were performed to detect differences in gene expression and brain atrophy. Expression of several genes associated with myelination including Mbp, Mag, and Plp1 were found to be altered, as were protein levels of Mbp, Mag, and DM20. Brain imaging revealed significant atrophy in cerebellum at P14, white matter thinning of the right internal capsule at P0, and white matter thickening in corpus callosum at P14 and right middle cerebellar peduncle at P56. We propose that maternal infection in mouse impacts myelination genes.

Keywords: schizophrenia, myelination, viral model, mouse, autism, brain

1. Introduction

There is robust epidemiologic evidence indicating that environmental contributions, including prenatal infections, may lead to genesis of schizophrenia (Suvasari et al., 1999; Limonson et al., 2003; Fatemi, 2005, 2008; Brown et al., 2006) and autism (Spear 2000, 2004; Arndt et al., 2006; Libbey et al., 2005). Several groups, including our laboratory, have shown evidence for viral infections and/or immune challenges being responsible for production of abnormal brain structure and function in rodents where mothers were exposed to viral insults throughout pregnancy (Fatemi et al., 1999, 2002a, 2005, 2008a,b,c; Meyer et al., 2006, 2007).

Previous reports have implicated various gene families in the etiopathology of schizophrenia including genes involved in myelination (Hakak et al., 2001; Tkachev et al., 2003; LeNiculescu et al., 2007). Hakak et al. (2001) using mostly elderly schizophrenic and matched control dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) homogenates, showed downregulation of 5 genes [myelin associated glycoprotein (MAG), myosin and lymphocyte protein (MAL), transferrin, neuregulin receptor ERBB3, and gelsolin] whose expression is enriched in myelin-forming oligodendrocytes, which have been implicated in the formation and maintenance of myelin sheaths. Later, Tkachev et al. (2003) using Broadmann Area 9 (BA9) homogenates from Stanley Brain collection showed significant downregulation in several myelin and oligodendrocyte related genes, such as proteolipid protein 1 (PLP1; Pongrac et al., 2002), MAG, oligodendrocyte specific protein CLDN11, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), and myelin basic protein (MBP) (Tkachev et al., 2003). Applying a functional genomics approach integrating data from postmortem studies, human genetic linkage studies, and an animal model, LeNiculescu et al. (2007) identified six genes (MAL, MBP, phospholipid protein 1 (PLP1), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), myelin-associated oligodendrocyte basic protein, and cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase) as schizophrenia candidate genes.

Hypermyelination has previously been observed in autism (Ben Bashat et al., 2007), Sturge-Weber syndrome (Moritani et al., 2008), and a case report of merosin deficiency in which the subject displayed mental retardation and epilepsy (Deodato et al., 2002). More than 70% of children with autism experience accelerated brain growth during the first two years of life (Courchesne and Pierce, 2005, Redcay and Courchesne, 2005). Significantly, Ben Bashat et al. (2007) observed accelerated maturation of white matter in a sample of children with autism between the ages of 1.8–3.3 years, the critical ages for accelerated brain growth.

Our group has demonstrated that influenza infection at E9 and E18 of pregnancy in mice leads to abnormal corticogenesis, brain atrophy, pyramidal cell atrophy, alterations in levels of several neuroregulatory proteins, such as Reelin, and Gfap, in the exposed mouse progeny (Fatemi et al., 1999, 2002a, 2002b, 2008a; Shi et al., 2003). We have demonstrated altered expression of myelination genes using this model (Fatemi et al., 2005, 2008a). Balb/c mice infected with influenza at E9 displayed reduced expression of Mbp and Plp1 mRNA in mice at birth (postnatal day 0 (P0)) (Fatemi et al., 2005). Following infection at E18, myelin transcription factor 1-like (Mytl1) was upregulated in cerebellum at P0 and hippocampus at P0 (Fatemi et al., 2008).

We hypothesized that middle second trimester infection (E16) in mice may lead to a different pattern of brain gene expression and structural defects in the developing offspring. Here, we present genetic, imaging, and protein data showing that a similar sublethal dose of human influenza virus (H1N1) in C57BL6J mice at E16, also leads to altered expression of many brain genes, including myelination genes, which may underlie brain atrophy and white matter changes in the exposed mouse offspring.

2. Experimental/Materials and Methods

2.1. Viral infection

C57BLJ mice were infected on E16 with a sublethal dose of influenza A/NWS/33 (H1N1) virus or sham-infected using vehicle solution. After being infected, drinking water contained 0.006% oxytetracycline (Pfizer, New York, NY) to control possible bacterial infections. Pregnant mice were allowed to deliver pups and the day of delivery was considered postnatal day 0 (P0). Groups of infected and sham-infected neonates were deeply anesthetized using ketamine (200 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)) and Nembutal (60 mg/kg, i.p.) and sacrificed on P0, P14, P35 and P56. Offspring were weaned from mothers at P21, and males and females were caged separately in groups of 2–4 littermates as previously described (Fatemi et al., 1999, 2002a,b, 2008a,b; Shi et al., 2003; Winter et al., 2008).

2.2. Brain collection and dissection

Male offspring of the infected and sham-infected mice were collected at P0, 14, 35, and 56. Cerebella were dissected and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for future assays as previously described (Fatemi et al., 2008a,b; Winter et al., 2008). Alternatively, mice were perfused transcardially and brains were removed from skull cavities for imaging studies as described previously (Fatemi et al., 2008a).

2.3. Microarray

Microarray was performed on cerebella from infected and sham-infected offspring (N=3 control and N=3 infected) at each of three time points [P0 (birth), P14 (childhood), P56 (adulthood)] as previously described (Fatemi et al., 2005, 2008a,b).

2.4. qRT-PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR for selected genes from our microarray data set that had an association with autism or schizophrenia was performed as previously described (Fatemi et al., 2008a) using the TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and a GAPDH endogenous control assay. Primary analysis of the acquired signal data was performed in SDS 2.3 and RQ Manager 1.2 (Applied Biosystems). Outlier reactions were removed after Grubb’s test identification and differential expression was calculated using the ΔΔCT method.

2.5. DTI and MR scanning

Brains from C57BL/6 male neonates born to infected and sham infected E16 mothers at P0, P14, P35, and P56 (N=4 infected, N=3 control, 1 male/litter per group) were perfusion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) and subjected to DTI and MR scanning in PBS at room temperature as previously described (Fatemi et al., 2008a; Mori et al., 2001).

2.6. SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

Brain tissue was prepared as previously described (Fatemi et al., 2006, 2008a). Samples were loaded onto the gel and electrophoresed and blotted as previously described (Fatemi et al., 2006, 2008a). The blots were then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C (mouse anti-MAG Chemicon mab1567, 1:500; mouse anti-PLP1, Abcam ab9311-50, 1:1000) or for 1 hour at RT (mouse anti-MBP Chemicon mab386, 1:500; mouse anti-β-actin, Sigma A5441, 1:5000) followed by secondary antibody incubation for 1 hour at RT (goat anti-mouse HRP conjugated, 1:80 000, Sigma). Between each step, the immunoblots were rinsed with PBS-T. The immune complexes were visualized using the ECL Plus detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and exposed to CL-Xposure film (Pierce). Sample densities were analyzed blind to nature of diagnosis using a BioRad densitometer and the BioRad Multi Analyst software. The molecular weights of approximately 69 kDa (Mag), 21.5, 18.5, 17.2, and 14 kDa (Mbp; the 18.5 and 17.2 kDa bands were measured together), 26 kDa (PLP1), and 20 kDa (DM20, a PLP1 splice variant) immunoreactive bands were quantified with background subtraction. Results obtained are based on at least two independent experiments with N=4 infected and N=4 control mice per gel. For each experiment, control and infected samples were run on the same gel and processed simultaneously to avoid variability due to intragel differences.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS. Differences of the normalized mRNA expression levels of selected genes between infected and control mice were assayed using two-tailed student’s t-test. Significant differences are defined as those with at least a 1.5 fold change and a p value < 0.05.

For western blots, differences of the protein levels of MAG, MBP, PLP1, and DM20 between the progeny of infected and sham-infected mice were normalized against β-actin and assayed using a two-tailed student’s t-test. Significant differences are defined as those with a p value < 0.05.

3. Results

Gene expression data showed a significant (p<0.05) at least 1.5 fold up- or downregulation of genes in cerebellum (27 upregulated and 73 downregulated at P0; 205 upregulated and 16 downregulated at P14; and 450 upregulated and 205 downregulated at P56) of mouse offspring (Supporting Table 1, online). Several genes, which have been previously implicated in etiopathology of autism and schizophrenia, were shown to be affected significantly (p<0.05) by DNA microarray including: autism susceptibility 2 (Auts2), myelin associated glycoprotein (Mag), myelin and lymphocyte-associated protein (Mal), myelin basic protein (Mbp), myelin-associated oligodendrocytic basic protein (Mobp), myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (Mog), cell adhesion molecule, neuronal 1 (Ncam1), proteolipid protein 1 (Plp1), and regulator of G protein signaling 4 (RGS4) (Table 1). Interestingly, myelination genes Mbp, Mobp, and Mog were altered significantly at multiple time points (Table 1). The direction and magnitude of change for Auts2, Mbp, Mobp, Mog, Plp1, and Rgs4 at P56 were verified by qRT-PCR (Table 1). Moreover, qRT-PCR analysis revealed downregulation of mRNA for Auts2, Mag, and Mog at additional time points (Table 2) and downregulation of mRNA for additional schizophrenia and autism susceptibility genes gamma-amino butyric acid receptor gamma 1 (Gabrg1), protein phosphatase 1, regulatory subunit 1b (Ppp1r1b), and neuronal cell adhesion molecule (Nrcam) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Microarray and qRT-PCR Results for Selected Affected Genes in E16 Infected Mice.

| Gene | Symbol | Disorder | Day | Microarray fold change | Microarray p-value | Gene relative to normalizer (qRT-PCR) | QPCR p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autism susceptibility candidate 2 | Auts2 | Auta | 56 | 2.85 | 0.018 | 1.48 | 0.023 |

| Myelin-associated glycoprotein | Mag | Sczb, c | 14 | 1.98 | 0.023 | * | * |

| Myelin and lymphocyte-associated protein | Mal | Sczc,d | 14 | 2.04 | 0.036 | * | * |

| Myelin basic protein | Mbp | Scze,f | 14 | 1.71 | 0.036 | * | * |

| 56 | −2.27 | 0.038 | −2.84 | 0.023 | |||

| Myelin-associated oligodendrocytic basic protein | Mobp | Sczg,h | 14 | 2.11 | 0.043 | * | * |

| 56 | −2.83 | 0.022 | −2.05 | 0.00011 | |||

| Myelin oligodendrocyte protein | Mog | Scze | 14 | 1.65 | 0.032 | * | * |

| 56 | −1.99 | 0.049 | −2.36 | 0.0036 | |||

| Cell adhesion molecule, neural, 1 | Ncam1 | Sczi | 56 | −1.99 | 0.010 | * | * |

| Proteolipid protein (myelin) 1 | Plp1 | Sczd | 56 | −2.06 | 0.047 | −1.97 | 0.00008 |

| Regulator of G-protein signaling 4 | Rgs4 | Sczj | 56 | −3.58 | 0.005 | −3.40 | 0.000007 |

Not altered in qRT-PCR analysis. Aut, autism; Scz, schizophrenia;

Table 2.

qRT-PCR Results for Selected Affected Genes in E16 Infected Mice.

| Gene | Symbol | Disorder | Day | Gene relative to normalizer (qRT-PCR) | QPCR p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autism susceptibility candidate 2 | Auts2 | Auta | 14 | −1.94 | 0.0090 |

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor gamma 1 | Gabrg1 | Autb | 56 | −2.33 | 0.00008 |

| Myelin-associated glycoprotein | Mag | Sczc, d | 0 | −3.03 | 0.016 |

| 56 | −2.31 | 0.008 | |||

| Myelin oligodendrocyte protein | Mog | Scze | 0 | −6.67 | 0.00085 |

| Neuronal cell adhesion molecule | Nrcam | Autf | 14 | −1.80 | 0.012 |

| Protein phosphatase 1, regulatory subunit 1b | Ppp1r1b | Sczg | 0 | −2.56 | 0.0024 |

Aut, autism; Scz, schizophrenia;

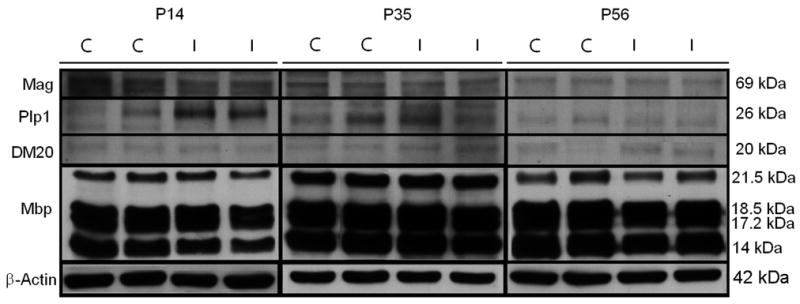

We further investigated protein expression for three of myelination related genes: Mag, Mbp, Plp1. Western blotting experiments revealed that Mbp 14 kDa protein was downregulated significantly in P14 (p<0.022) and Mbp 18.5 and 17.2 kDa proteins (measured together) were downregulated significantly in P56 cerebellum (p<0.026) of exposed mouse progeny (Figure 1, Table 3). DM20, a splice variant of Plp1, was shown to be significantly upregulated at P35 (p<0.0034) and P56 (p<0.016) in cerebella of exposed mice (Figure 1, Table 3). Mag was significantly downregulated at P14 (p<0.044) and at P35 (p<0.0025) in cerebella of exposed mice (Figure 1, Table 3). PLP1 protein was not significantly changed following prenatal viral infection (Figure 1, Table 3).

Figure 1.

Representative western blotting results for Mag (69 kDa), Plp1 (26 kDa), DM20 (20 kDa), Mbp (21.5 kDa, 18.5 kDa, 17.2 kDa, 14 kDa), and β-actin (42 kDa), for control (C) and infected (I) mouse cerebella at P14, P35, and P56.

Table 3.

Effect of Prenatal Viral Infection on Myelin Basic Protein, Proteolipid Protein, DM20, and Myelin Associated Glycoprotein Levels in Mouse Cerebellum

| P0 | Infected | Control | % Change | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mag/β-Actin | 0.071 ± 0.009 | 0.068 ± 0.007 | 4%↑ | 0.84 |

| Plp1/β-Actin | 0.052 ± 0.024 | 0.032 ± 0.004 | 62%↑ | 0.24 |

| DM20/β-Actin | 0.165 ± 0.048 | 0.132 ± 0.064 | 34%↑ | 0.52 |

| P14 | Infected | Control | % Change | P-valuea |

| Mbp 21.5/β-Actin | 0.29 ± 0.11 | 0.31 ± 0.14 | 6%↓ | 0.85 |

| Mbp 18.5 & 17.2/β-Actin | 1.50 ± 0.23 | 1.85 ± 0.36 | 19%↓ | 0.093 |

| Mbp 14/β-Actin | 0.79 ± 0.10 | 1.18 ± 0.16 | 33%↓ | 0.022 |

| Mag/β-Actin | 0.085 ± 0.008 | 0.125 ± 0.022 | 32%↓ | 0.044 |

| Plp1/β-Actin | 0.046 ± 0.02 | 0.018 ± 0.009 | 156%↑ | 0.14 |

| DM20/β-Actin | 0.065 ± 0.031 | 0.065 ± 0.012 | 0% | 1.0 |

| P35 | Infected | Control | % Change | P-valuea |

| Mbp 21.5/β-Actin | 1.10 ± 0.09 | 0.91 ± 0.11 | 11%↑ | 0.084 |

| Mbp 18.5 & 17.2/β-Actin | 3.44 ± 0.38 | 3.24 ± 0.57 | 7%↑ | 0.63 |

| Mbp 14/β-Actin | 2.52 ± 0.30 | 2.72 ± 0.44 | 7%↓ | 0.19 |

| Mag/β-Actin | 0.187 ± 0.039 | 0.254 ± 0.022 | 26%↓ | 0.025 |

| Plp1/β-Actin | 0.088 ± 0.019 | 0.084 ± 0.026 | 5%↑ | 0.83 |

| DM20/β-Actin | 0.088 ± 0.015 | 0.050 ± 0.0005 | 76%↑ | 0.0034 |

| P56 | Infected | Control | % Change | P-valuea |

| Mbp 21.5/β-Actin | 0.25 ± 0.07 | 0.23 ± 0.08 | 9%↑ | 0.79 |

| Mbp 18.5 & 17.2/β-Actin | 2.26 ± 0.18 | 2.56 ± 0.09 | 12%↓ | 0.026 |

| Mbp 14/β-Actin | 1.54 ± 0.14 | 1.83 ± 0.32 | 16%↓ | 0.14 |

| Mag/β-Actin | 0.082 ± 0.029 | 0.054 ± 0.004 | 52%↑ | 0.17 |

| Plp1/β-Actin | 0.024 ± 0.002 | 0.03 ± 0.004 | 20%↓ | 0.067 |

| DM20/β-Actin | 0.020 ± 0.003 | 0.014 ± 0.003 | 43%↑ | 0.016 |

Two-tailed unpaired t-test; Mag, Myelin associated glycoprotein; Mbp, myelin basic protein; Plp1, proteolipid protein 1; ↑ Increases; ↓ Decreases.

Morphometric analysis of brain following infection of C57BL/6 mice at E16 revealed numerous defects. The area for cerebellum at P14 was reduced (p<0.029; Table 4) and ventricular volume was reduced at P0 (p<0.025; Table 4). Moreover, fractional anisotropy (FA) revealed the following changes: decrease in FA in the right internal capsule (IC-r) at P0 (p<0.033); and increases in FA in the corpus callosum at P14 (p<0.024) and the right middle cerebellar peduncle (MCP-r) at P56 (p<0.006) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Changes in brain and ventricular areas following infection at E16

| PD | Brain Area | Control | Infected | % Change | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P0 | Cerebellum | 3.47 ± 0.50 | 3.06 ± 0.44 | – | 0.267 |

| Ventricle | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.010 ± 0.006 | ↓66% | 0.0253 | |

| P14 | Cerebellum | 46.06 ± 2.06 | 41.18 ± 2.23 | ↓11% | 0.0298 |

| Ventricle | 0.077 ± 0.067 | 0.030 ± 0.014 | – | 0.293 | |

| P35 | Cerebellum | 56.09 ± 2.43 | 56.39 ± 2.31 | – | 0.862 |

| Ventricle | 0.34 ± 0.19 | 0.17 ± 0.13 | – | 0.2 | |

| P56 | Cerebellum | 56.26 ± 2.24 | 54.51 ± 3.20 | – | 0.403 |

| Ventricle | 0.17 ± 0.11 | 0.95 ± 1.63 | – | 0.379 | |

Two-tailed unpaired t-test; PD, postnatal date

Table 5.

Fractional Anisotropy following prenatal viral infection at E16

| PD | Brain Area | Infected | Control | % Change | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P0 | CC | 0.72 ± 0.081 | 0.63 ± 0.042 | 14%↑ | 0.10 |

| IC-l | 0.45 ± 0.092 | 0.46 ± 0.035 | 2%↓ | 0.88 | |

| IC-r | 0.44 ± 0.044 | 0.51 ± 0.022 | 14%↓ | 0.034 | |

| P14 | CC | 0.68 ± 0.017 | 0.61 ± 0.036 | 11%↑ | 0.025 |

| MCP-l | 0.64 ± 0.137 | 0.61 ± 0.069 | 5%↑ | 0.70 | |

| MCP-r | 0.64 ± 0.092 | 0.57 ± 0.050 | 12%↑ | 0.23 | |

| IC-l | 0.70 ± 0.061 | 0.58 ± 0.098 | 21%↑ | 0.16 | |

| IC-r | 0.70 ± 0.015 | 0.64 ± 0.081 | 9%↑ | 0.26 | |

| P35 | CC | 0.69 ± 0.061 | 0.65 ± 0.045 | 6%↑ | 0.30 |

| MCP-l | 0.64 ± 0.038 | 0.69 ± 0.072 | 7%↓ | 0.27 | |

| MCP-r | 0.61 ± 0.059 | 0.63 ± 0.040 | 3%↓ | 0.64 | |

| IC-l | 0.68 ± 0.019 | 0.61 ± 0.129 | 11%↑ | 0.32 | |

| IC-r | 0.69 ± 0.034 | 0.68 ± 0.109 | 1%↑ | 0.93 | |

| P56 | CC | 0.72 ± 0.049 | 0.66 ± 0.060 | 9%↑ | 0.19 |

| MCP-l | 0.70 ± 0.098 | 0.74 ± 0.060 | 5%↓ | 0.57 | |

| MCP-r | 0.78 ± 0.016 | 0.71 ± 0.031 | 10%↑ | 0.0061 | |

| IC-l | 0.71 ± 0.083 | 0.76 ± 0.017 | 7%↓ | 0.35 | |

| IC-r | 0.72 ± 0.080 | 0.71 ± 0.101 | 1%↑ | 0.85 | |

Two-tailed unpaired t-test; CC, corpus callosum; IC-l, internal capsule (left); IC-r, internal capsule (right); MCP-l, middle cerebellar peduncle (left); MCP-r, middle cerebellar peduncle (right); PD, postnatal day.

4. Discussion

Prenatal viral infection lead to altered gene expression of genes in cerebellum at P0, P14, and P56 including numerous schizophrenia candidate genes such as Rgs4, Auts2, Mbp, Mag, Mog, Mobp, Plp1, and Ncam1. qRT-PCR verified the direction and magnitude of change for Auts2, Mbp, Mobp, Mog, Plp1, and Rgs4 at P56. Further investigation of myelination genes via western blotting revealed significant reductions in Mbp isoform expression at P14 and P56, significant reductions in Mag at P14 and P35, and significant upregulation of DM20 at P35 and P56. No Mbp bands were detected for both control and infected P0 mice. This result is consistent with what has been previously determined by other research groups (Mathisen et al., 1993; Freude et al., 2008). Morphometric analysis revealed reduced cerebellar and brain volumes at P14, reduced hippocampal volume at P35, reduced white matter thickness of the IC-r at P0, and increased white matter thickness in the CC at P14 and the MCP-r at P56. Table 6 summarizes the changes observed for myelination genes and brain structure at the four postnatal time points.

Table 6.

Comparison of myelin gene mRNA and protein changes with brain volume and fractional anisotropic changes

| PD | Microarray | qRT-PCR | Protein | Volume | FA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P0 | ↓Mag, ↓Mobp, | ↓Ventricle | ↓IC-r | ||

| P14 | ↑Mag, ↑Mal, ↑Mbp, ↑Mobp, ↑Mog | N/C | ↓Mag, ↓Mbp | ↓Cer | ↑CC |

| P35 | N/A | N/A | ↓Mag, ↑DM20 | N/C | N/C |

| P56 | ↓Mbp, ↓Mobp, ↓Mog, ↓Plp1 | ↓Mag, ↓Mbp, ↓Mobp, ↓Mog, ↓Plp1 | ↓Mbp, ↑DM20 | N/C | ↑MCP-r |

CC, corpus callosum; Cer, Cerebellum; FA, fractional anisotropy; Hipp, hippocampus; IC-r, Internal capsule (right); MCP-r, middle cerebellar peduncle (right); N/A, not applicable; N/C, no change; PD, postnatal day.

While the cerebellum has been underutilized in the study of psychiatric disorders, we chose to investigate the effects of prenatal viral infection in this region because a number of studies have demonstrated changes in cerebellar structure and function in subjects with schizophrenia. Both increased (DeLisi et al., 1997; Nopoulos et al., 1999; Uematsu and Kaiya, 1989) and decreased (Goldman et al., 2008) cerebellar volumes have been previously observed in subjects with schizophrenia as measured by MRI. Additionally, disruption of the cortico-thalamic-cerebellar-cortical circuit (CTCCC) has been identified in subjects with schizophrenia (Andreasen et al., 1996). Functional MRI scans have revealed reduced activation of the cerebellum during cognitive tests (Meyer-Lindberg et al., 2001; Kumari et al., 2002) and PET scans have revealed reduced blood flow during tests to evaluate “Theory of Mind” (Andreasen et al., 2008). Taken together, these deficits point to impaired cerebellar function, which may contribute to cognitive and behavioral disturbances in subjects with schizophrenia.

Several reports using MRI and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) techniques have shown reduced white matter diffusion anisotropy (diffusion changes in water in white matter) in subjects with schizophrenia (Lim and Helpern, 2002; Ardekani et al., 2003; Kubcki et al., 2003; Carpenter et al., 2008). Reductions in white matter anisotropy reflect disrupted white matter connections (Ardekani et al., 2003), which supports the disconnection model of schizophrenia (Bullmore et al., 1997). Marked declines in FA have been observed over the duration of illness (Carpenter et al., 2008; Friedman et al., 2008). Other research groups have identified little or no changes in fractional anisotropy during first episode schizophrenia (Peters et al., 2008) and there are also negative findings showing no white matter abnormalities in schizophrenia (Steel et al., 2001; Foong et al., 2002; Peters et al., 2008). It is conceivable that downregulation of genes affecting production of myelin-related proteins, as well as other components of axons, may lay the foundation for white matter abnormalities which develop later in life in subjects who become schizophrenic (Hakak et al., 2001; Tkachev et al., 2003). Consistent with this hypothesis, we observed reduction in gene expression of Mbp, Mobp, Mog, and Plp1via microarray and qRT-PCR at P56, which corresponds to adulthood in mice. Moreover, we also observed decreased Mbp 18.5 kDa and 17.2 kDa protein at this time point.

Developmentally, reduced FA suggests delayed maturation as FA has been shown to increase with brain maturation from juvenile to adult as myelination decreases the space between neurons resulting in increased anisotropy (Neil et al., 1998; Nomura et al., 1994). Reduced FA in the right internal capsule observed at P0 may suggest delayed maturation while the increased FA in the corpus callosum at P14 and the right middle cerebellar peduncle at P56 might suggest accelerated maturation. The increased FA of the corpus callosum at P14 may be due to the upregulation of myelination genes: Mal, Mbp, Mog, Mag, and Mobp at the same time point (Table 1). However, qRT-PCR did not validate these findings and protein data revealed decreases in Mbp and Mag at P14 (Tables 1, 2, and 6). The increased FA of the CC at P14 and the MCP at P56 may be due to other factors. As mentioned in the introduction, hypermyelination and accelerated brain growth are common during the first two years of life for children with autism (Ben Bashat et al., 2007; Courchesne and Pierce, 2005, Redcay and Courchesne, 2005). It is conceivable that our animal model may mimic some of the structural/genetic markers of autism (Fatemi et al., 2002a; Patterson, 2007). Further studies are also needed to clarify the role, if any, that myelination genes play in changes in fractional anisotropy observed in subjects with schizophrenia or in animal models of schizophrenia.

Mbp comprises about 30% of the myelin membrane and is believed to be involved in myelin compaction (Chambers and Perrone-Bizzozero, 2004). Chambers and Perrone-Bizzozero (2004) found reduced Mbp immunoreactivity in hippocampus of female subjects with schizophrenia. Animal models for schizophrenia have also shown alterations in Mbp expression following prenatal viral infection at E9 (Fatemi et al., 2005) and injection of PolyI:C on E9.5 (Makinodan et al., 2008). Moreover, transgenic mice that lack Mbp (known as shiverer) show delayed action potentials (Lehman and Harrison, 2002). The observed significant reductions of Mbp protein isoforms at P14 and P56 are consistent with these findings.

Plp1 is a major component of mammalian CNS myelin with possible functions in myelin stability and maintenance (Hudson, 2004). PLP1 has shown to be downregulated in the temporal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia (Aston et al., 2004). Genetic association studies have been inconsistent with a weak association between a single nucleotide polymorphism of PLP1 and susceptibility to schizophrenia in Han Chinese males (Qin et al., 2005), while a recent Japanese population-based association study showed no association with schizophrenia (Aleksic et al., 2008). While our microarray and qRT-PCR results showed a significant downregulation of Plp1 mRNA at P56, we did not observe any significant changes in Plp1 protein expression although the DM20 splice variant was increased at P35 and P56.

Mag is involved with mediating glial-axon interactions during myelination (Marcus et al., 2002). Microarray analysis has revealed reduced MAG expression in the temporal cortex (Aston et al., 2004), anterior cingulate cortex (Dracheva et al., 2006; McCullersmith et al., 2007), hippocampus (Dracheva et al., 2006), and prefrontal cortex (Hakak et al., 2001; Tkachev et al., 2003) of subjects with schizophrenia. In contrast Mitkus et al., (2008) found no significant difference in MAG mRNA expression in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex between subjects with schizophrenia and controls (Mitkus et al., 2008). Two association studies have shown an association between MAG and schizophrenia in Han Chinese (Wan et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2005). A recent study by Voineskos et al., (2008) shows no association between MAG variants and schizophrenia based on single marker and haplotype analysis. While we observed an increase in MAG mRNA in P14 cerebella, qRT-PCR did not validate this finding. However, qRT-PCR did reveal significant reductions in Mag mRNA at P0 and P56 (Table 2). We did observe significant reductions in Mag protein levels between the offspring of control and infected dams (Figure 1, Table 3).

Three other myelination genes that were altered in cerebellum were: 1) Mog, which is specific to the CNS and is located on the surface of oligodendrocytes and myelin sheaths (Brunner et al., 1989). MOG mRNA has been shown to be decreased in prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia (Tkachev et al., 2003). We also observed a reduction in Mog mRNA at P56 as measured by microarray and qRT-PCR (Table 1); 2) Mobp, which is believed to have a role in myelin compaction or stabilization (Montague et al., 2006). MOBP has been identified as a candidate gene for schizophrenia (Lewis et al., 2003). We observed reduced Mobp via microarray at P56, which was verified by qRT-PCR; and 3) Mal is thought to be involved in the organization, transport, and maintenance of glycosphingolipid-enriched membranes (Kamsteeg et al., 2007). MAL has been identified it as a candidate gene for schizophrenia (DeLisi et al., 2002; Straub et al., 2002; Lewis et al., 2003). We observed increased Mal mRNA in cerebella of infected offspring (Table 1).

Middle second trimester is a period when prenatal infection has been linked to the development of schizophrenia later in life (Suvasari et al., 1999; Limonson et al., 2003; Brown et al., 2006). Compared with other time points (E9, E18), infection at E16 (middle second trimester in mice) resulted in changes in expression for a greater number of genes including those related to myelination (Table 7). Moreover, there were more changes in FA than at E18 (Table 7). Unfortunately, we do not have data on white matter changes following infection at E9 for a comparison although we have previously shown reduced neocortical 1-VI layers, and intermediate zone, and hippocampus at P0 (Fatemi et al., 1999). Why infection at mid-pregnancy leads to greater changes in myelination gene expression and white matter abnormalities remains to be determined by future experiments.

Table 7.

Summary changes following prenatal viral infection in Cerebellum

| Infection Date | Postnatal Date | Cerebellum (Total Genes) | Myelination Genes | White Matter Changes | Brain Volume Changes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E9b | P0 | N/A | N/A | ↓Mbp, ↓Plp1 (WB) | ||

| P35 | ↑103 | ↓102 | ||||

| P56 | ↑27 | ↓23 | ||||

| E16a | P0 | ↑26 | ↓72 | ↓IC-r | ↓V | |

| P14 | ↑204 | ↓15 | ↑Mag, ↑Mal, ↑Mbp, ↑Mobp, ↑Mog (Cer) | ↑CC | ↓Cer | |

| P35 | N/A | N/A | ||||

| P56 | ↑449 | ↓204 | ↓ Mbp, ↓Mobp, ↓Mog, ↓Plp1 (Cer) | ↑MCP-r | ||

| E18a | P0 | ↑120 | ↓37 | ↑Myt1l (Cer, Hipp) | ||

| P14 | ↑11 | ↓5 | ||||

| P35 | N/A | N/A | ↓CC | ↓Cer, Hipp, WB | ||

| P56 | ↑74 | ↓22 | ||||

Cer, cerebellum; Hipp, hippocampus; V, ventricle; WB, whole brain; ↑, increase; ↓, decrease;

C57BL6J mice;

Balb/c mice; Data from Fatemi et al, 2005a, 2008a,b, unpublished. Modified version reprinted from Schizophrenia Research, Vol 99 (1–3), Fatemi et al., Maternal infection leads to abnormal gene regulation and brain atrophy in mouse offspring: Implications for genesis of neurodevelopmental disorders, 56–70, Copyright (2008), with permission from Elsevier.

Some limitations of our study include: 1) there was a small sample size with n=3 or N=4 per group; 2) we were unable to measure additional candidate genes at each time point due to the extensive list of genes involved in the infection process; and 3) lack of behavioral, motor and cognitive data following infection at E16. Future studies will focus on obtaining behavioral data at adulthood to investigate the functional consequences of infection at E16.

Our results demonstrate that infection at E16 results in the following: 1) altered expression of a number of schizophrenia and autism candidate genes; 2) altered expression of genes related to myelination, 5 of which are verified by qRT-PCR at P56; 3) altered protein expression for Mag, Mbp, and DM20 suggesting changes in myelin composition; 4) atrophy in cerebellar volume at P14; 5) changes in fractional anisotropy in multiple regions suggesting changes in white matter maturation; and 6) more changes in altered expression of total genes and genes related to myelination and white matter than infection at E9 or E18. These results suggest that infection at mid-second trimester, a time point during which infection has been linked to development of schizophrenia in humans, causes more severe effects on brain development that either mid-first (E9) or late second (E18) trimesters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (#5R01-HD046589-04) to SHF is gratefully acknowledged. Assistance with microarray data interpretation by Dr. Chuanning Tang and Dr. Tongbin Li of the University of Minnesota Department of Neuroscience is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

S. Hossein Fatemi, Email: fatem002@umn.edu.

Timothy D. Folsom, Email: folso013@umn.edu.

Teri J. Reutiman, Email: reuti003@umn.edu.

Desiree Abu-Odeh, Email: abuod001@umn.edu.

Susumu Mori, Email: susumu@mri.jhu.edu.

Hao Huang, Email: Hao.Huang@utsouthwestern.edu.

Kenichi Oishi, Email: koishi@mri.jhu.edu.

References

- Aleksic B, Ikeda M, Ishihara R, Saito S, Inada T, Iwata N, Ozaki N. No association between the oligodendrocyte-related gene PLP1 and schizophrenia in the Japanese population. J Hum Genet. 2008;53(9):863–836. doi: 10.1007/s10038-008-0318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, O’Leary DS, Cizadlo T, Arndt S, Rezai K, Ponto LL, Watkins GL, Hichwa RD. Schizophrenia and cognitive dysmetria: a positron-emission tomography study of dysfunctional prefrontal-thalamic-cerebellar circuitry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(18):9985–9990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Calage CA, O’Leary DS. Theory of mind and schizophrenia: a positron emission tomography study of medication-free patients. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(4):708–719. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardekani BA, Nierenberg J, Hoptman MJ, Javitt DC, Lim KO. MRI study of white matter diffusion anisotropy in schizophrenia. NeuroReport. 2003;14(16):2025–2029. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200311140-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt TL, Stodgell CJ, Rodier PM. The teratology of autism. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23(2–3):189–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asherson P, Mane R, McGiffin P. Genetics and schizophrenia. In: Mirsch SR, Weinberger DR, editors. Schizophrenia. Blackwell Scientific; Boston: 1994. pp. 253–274. [Google Scholar]

- Aston C, Jiang L, Sokolov BP. Microarray analysis of postmortem temporal cortex from patients with schizophrenia. J Neurosci Res. 2004;77(6):858–866. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atz ME, Rollins B, Vawter MP. NCAM1 association study of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: polymorphisms and alternatively spliced isoforms lead to similarities and differences. Psychiatr Genet. 2007;17(2):55–67. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e328012d850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Bashat D, Kronfeld-Duenias V, Zachor DA, Ekstein PM, Hendler T, Tarrasch R, Even A, Levy Y, Ben Sira L. Accelerated maturation of white matter in young children with autism: a high b value DWI study. Neuroimage. 2007;37(1):40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS. Prenatal infection as a risk factor for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:200–202. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner C, Lassmann H, Waehneldt TV, Matthieu JM, Linington C. Differential ultrastructural localization of myelin basic protein, myelin oligodendroglial glycoprotein, and 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase in the CNS of adult rats. J Neurochem. 1989;52:296–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb10930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullmore ET, Frangou S, Murray RM. The dysplastic net hypothesis: an integration of developmental and dysconnectivity theories of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1997;28:143–156. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(97)00114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter DM, Tang CY, Friedman JI, Hof PR, Stewart DG, Buchsbaum MS, Harvey PD, Gorman JG, Davis KL. Temporal characteristics of tract-specific anisotropy abnormalities in schizophrenia. Neuroreport. 2008;19(14):1369–1372. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32830abc35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers JS, Perrone-Bizzozero NI. Altered myelination of the hippocampal formation in subjects with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neurochem Res. 2004;29(12):2293–2302. doi: 10.1007/s11064-004-7039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne E, Pierce K. Brain overgrowth in autism during a critical time in development: implications for frontal pyramidal neuron and interneuron development and connectivity. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23(2–3):153–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisi LE, Sakuma M, Tew W, Kushner M, Hoff AL, Grimson R. Schizophrenia as a chronic active brain process: a study of progressive brain structural change subsequent to the onset of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1997;74(3):129–140. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(97)00012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisi LE, Shaw SH, Crow TJ, Shields G, Smith AB, Larach VW, Wellman N, Loftus J, Nanthakumar B, Razi K, Stewart J, Comazzi M, Vita A, Heffner T, Sherrington R. A genome-wide scan for linkage to chromosomal regions in 382 sibling pairs with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:803–812. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deodato F, Sabatelli M, Ricci E, Mercuri E, Muntoni F, Sewry C, Naom I, Tonali P, Guzzetta F. Hypermyelinating neuropathy, mental retardation and epilepsy in a case of merosin deficiency. Neuromuscul Disord. 2002;12:392–398. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(01)00312-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dracheva S, Davis KL, Chin B, Woo DA, Schmeidler J, Haroutunian V. Myelin-associated mRNA and protein expression deficits in the anterior cingulate cortex and hippocampus in elderly schizophrenia patients. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;21(3):531–540. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Emamian ES, Kist D, Sidwell RW, Nakajima K, Akhter P, Shier A, Sheikh S, Bailey K. Defective corticogenesis and reduction in Reelin immunoreactivity in cortex and hippocampus of prenatally infected neonatal mice. Mol Psychiatry. 1999;4(2):145–154. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Emamian ES, Sidwell RW, Kist DA, Stary JM, Earle JA, Thuras P. Human influenza viral infection in utero alters glial fibrillary acidic protein immunoreactivity in the developing brains of neonatal mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2002a;7(6):633–640. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Earle J, Kanodia R, Kist D, Patterson P, Shi L, Sidwell RW. Prenatal viral infection causes macrocephaly and pyramidal cell atrophy in the developing mice. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2002b;22(1):25–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1015337611258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, editor. Neuropsychiatric Disorders and Infection. Taylor & Francis; London: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Pearce DA, Brooks AI, Sidwell RW. Prenatal viral infection in mouse causes differential expression of genes in brains of mouse progeny: A potential animal model for schizophrenia and autism. Synapse. 2005;57(2):91–99. doi: 10.1002/syn.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD, Bell C, Nos L, Fried P, Pearce DA, Singh S, Siderovski DP, Willard FS, Fukuda M. Chronic olanzapine treatment causes differential expression of genes in frontal cortex of rats as revealed by DNA microarray technique. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1888–1899. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH. Schizophrenia. In: Fatemi SH, Clayton P, editors. The Medical Basis of Psychiatry. 3. Humana Press; New York: 2008. pp. 85–108. [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD, Huang H, Oishi K, Mori S, Smee DF, Pearce DA, Winter C, Sohr R, Juckel G. Maternal infection leads to abnormal gene regulation and brain atrophy in mouse offspring: implications for genesis of neurodevelopmental disorders. Schizophr Res. 2008a;99(1–3):56–70. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD, Sidwell RW. The role of cerebellar genes in pathology of autism and schizophrenia. Cerebellum. 2008b;7(3):279–294. doi: 10.1007/s12311-008-0017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Folsom TD, Reutiman TJ, Sidwell RW. Viral regulation of aquaporin 4, connexin 43, microcephalin and nucleolin. Schizophr Res. 2008c;98(1–3):163–177. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldcamp LA, Souza RP, Romano-Silva M, Kennedy JL, Wong AH. Reduced prefrontal cortex DARPP-32 mRNA in completed suicide victims with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;103(1–3):192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foong J, Maier M, Clark CA, Barker GJ, Miller DH, Ron MA. Neuropathological abnormalities of the corpus callosum in schizophrenia: a diffusion tensor imaging study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:242–244. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.2.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foong J, Symms MR, Barker GJ, Maier M, Miller DH, Ron MA. Investigating regional white matter in schizophrenia using diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroreport. 2002;13:333–336. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200203040-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freude S, Leeser U, Müller M, Hettich MM, Udelhoven M, Schilbach K, Tobe K, Kadowaki T, Köhler C, Schröder H, Krone W, Brüning JC, Schubert M. IRS-2 branch of IGF-1 receptor signaling is essential for appropriate timing of myelination. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05631.x. Postprint. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JI, Tang C, Carpenter D, Buchsbaum M, Schmeidler J, Flanagan L, Golembo S, Kanellopoulou I, Ng J, Hof PR, Harvey PD, Tsopelas ND, Stewart D, Davis KL. Diffusion tensor imaging findings in first-episode and chronic schizophrenia patients. Am J Psychiatry 2008. 2008;165(8):1024–1032. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07101640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman AL, Pezawas L, Mattay VS, Fischl B, Verchinski BA, Zoltick B, Weinberger DR, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Heritability of brain morphology related to schizophrenia: a large-scale automated magnetic resonance imaging segmentation study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(5):475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakak Y, Walker JR, Li C, Wong WH, Davis KL, Buxbaum JD, Haroutunian V, Fienberg AA. Genome-wide expression analysis reveals dysregulation of myelination-related genes in chronic schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4746–4751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081071198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson LD. Proteolipid protein gene. In: Lazzarini RA, editor. Myelin Biology and Disorders. Elsevier AP; London: 2004. pp. 401–420. [Google Scholar]

- Kakinuma H, Ozaki M, Sato H, Takahashi H. Variation in GABA-A subunit gene copy number in an autistic patient with mosaic 4p duplication (p12p16) Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B(6):973–975. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamsteeg EJ, Duffield AS, Konings IB, Spencer J, Pagel P, Deen PM, Caplan MJ. MAL decreases the internalization of the aquaporin-2 water channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(42):16696–16701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708023104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicki M, Park H, Westin CF, Nestor PG, Mulkern RV, Maier SE, Niznikiewicz M, Connor EE, Levitt JJ, Frumin M, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, McCarley RW, Shenton ME. DTI and MTR abnormalities in schizophrenia: analysis of white matter integrity. Neuroimage. 2005;26(4):1109–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V, Gray JA, Goney GD, Soni W, Bullmore ET, Williams SC, Ng VW, Vythelingum GN, Simmons A, Suckling J, Corr PJ, Sharma T. Procedural learning in schizophrenia: a functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation. Schizophr Res. 2002;57(1):97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00270-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman DM, Harrison JM. Flash visual evoked potentials in the hypomyelinated mutant mouse shiverer. Doc Ophthalmol. 2002;104(1):83–95. doi: 10.1023/a:1014415313818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le-Niculescu H, Balaraman Y, Patel S, Tan J, Sidhu K, Jerome RE, Edenberg HJ, Kuczenski R, Geyer MA, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Faraone SV, Tsuang MT, Niculescu AB. Towards understanding the schizophrenia code: an expanded convergent functional genomics approach. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B(2):129–158. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CM, Levinson DF, Wise LH, DeLisi LE, Straub RE, Hovatta I, et al. Genome scan meta-analysis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, part II: Schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:34–48. doi: 10.1086/376549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libbey JE, Sweeten TL, McMahon WM, Fujinami RS. Autistic disorder and viral infections. J Neurovirol. 2005;11(1):1–10. doi: 10.1080/13550280590900553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim KO, Hedehus M, Moseley M, de Crespigny A, Sullivan EV, Pfefferbaum A. Compromised white matter tract integrity in schizophrenia inferred from diffusion tensor imaging. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:367–374. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim KO, Helpern JA. Neuropsychiatric applications of DTI - a review. NMR Biomed. 2002;15:587–593. doi: 10.1002/nbm.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limosin F, Rouillon F, Payan C, Cohen JM, Strub N. Prenatal exposure to influenza as a risk factor for adult schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:331–335. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makinodan M, Tatsumi K, Manabe T, Yamauchi T, Makinodan E, Matsuyoshi H, Shimoda S, Noriyama Y, Kishimoto T, Wanaka A. Maternal immune activation in mice delays myelination and axonal development in the hippocampus of the offspring. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86(10):2190–2200. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus J, Dupree JL, Popko B. Myelin-associated glycoprotein and myelin galactolipids stabilize developing axo-glial interactions. J Cell Biol. 2002;156(3):567–577. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marui T, Funatogawa I, Koishi S, Yamamoto K, Matsumoto H, Hashimoto O, Nanba E, Nishida H, Sugiyama T, Kasai K, Watanabe K, Kano Y, Kato N. Association of the neuronal cell adhesion molecule (NRCAM) gene variants with autism. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12(1):1–10. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathisen PM, Pease S, Garvey J, Hood L, Readhead C. Identification of an embryonic isoform of myelin basic protein that is expressed widely in the mouse embryo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90(21):10125–10129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullumsmith RE, Gupta D, Beneyto M, Kreger E, Haroutunian V, Davis KL, Meador-Woodruff JH. Expression of transcripts for myelination-related genes in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;90(1–3):15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer U, Nyffeler M, Engler A, Urwyler A, Schedlowski M, Knuesel I, Yee BK, Feldon J. The time of prenatal immune challenge determines the specificity of inflammation-mediated brain and behavioral pathology. J Neurosci. 2006;26(18):4752–4762. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0099-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer U, Yee BK, Feldon J. The neurodevelopmental impact of prenatal infections at different times of pregnancy: the earlier the worse? Neuroscientist. 2007;13(3):241–256. doi: 10.1177/1073858406296401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A, Poline JB, Kohn PD, Holt JL, Egan MF, Weinberger DR, Berman KF. Evidence for abnormal cortical functional connectivity during working memory in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(11):1809–1817. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitkus SN, Hyde TM, Vakkalanka R, Kolachana B, Weinberger DR, Kleinman JE, Lipska BK. Expression of oligodendrocyte-associated genes in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;98(1–3):129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague P, McCallion AS, Davies RW, Griffiths IR. Myelin-associated oligodendrocytic basic protein: a family of abundant CNS myelin proteins in search of a function. Dev Neurosci. 2006;28(6):479–487. doi: 10.1159/000095110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Ito R, Zhang J, Kaufmann WE, van Zijl PC, Solaiyappan M, Yarowski P. Diffusion tensor imaging of the developing mouse brain. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46(1):18–23. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritani T, Kim J, Sato Y, Bonthius D, Smoker WR. Abnormal hypermyelination in a neonate with Sturge-Weber syndrome demonstrated on diffusion-tensor imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27:617–620. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neil JJ, Shiran SI, McKinstry RC, Schefft GL, Snyder AZ, Almli CR, Akbudak E, Aronovitz JA, Miller JP, Lee BC, Conturo TE. Normal brain in human newborns: apparent diffusion coefficient and diffusion anisotropy measured by using diffusion tensor MR imaging. Radiology. 1998;209(1):57–66. doi: 10.1148/radiology.209.1.9769812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Yamaguchi T, Tokunaga A, Hara A, Hamaguchi T, Kato K, Iwamatsu M, Peters BD, de Haan L, Dekker N, Blaas J, Becker HE, Dingemans PM, Akkerman EM, Majoie CB, van Amelsvoort T, den Heeten GJ, Linszen DH. White Matter Fibertracking in First-Episode Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective Patients and Subjects at Ultra-High Risk of Psychosis. Neuropsychobiology. 2008;58(1):19–28. doi: 10.1159/000154476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura Y, Sakuma H, Takeda K, Tagami T, Okuda Y, Nakagawa T. Diffusional anisotropy of the human brain assessed with diffusion-weighted MR: relation with normal brain development and aging. Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15(2):231–238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nopoulos PC, Ceilley JW, Gailis EA, Andreasen NC. An MRI study of cerebellar vermis morphology in patients with schizophrenia: evidence in support of the cognitive dysmetria concept. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(5):703–711. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson PH. Neuroscience. Maternal effects on schizophrenia risk. Science. 2007;318:576–577. doi: 10.1126/science.1150196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongrac J, Middleton FA, Lewis DA, Levitt P, Mirnics K. Gene expression profiling with DNA microarrays: advancing our understanding of psychiatric disorders. Neurochem Res. 2002;27:1049–1063. doi: 10.1023/a:1020904821237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin W, Gao J, Xing Q, Yang J, Qian X, Li X, Guo Z, Chen H, Wang L, Huang X, Gu N, Feng G, He L. A family-based association study of PLP1 and schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett. 2005;375(3):207–210. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redcay E, Courchesne E. When is the brain enlarged in autism? A meta-analysis of all brain size reports. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Fatemi SH, Sidwell RW, Patterson PH. A mouse model of mental illness: maternal influenza infection causes behavioral and pharmacological abnormalities in the offspring. J Neurosci. 2003;23(1):297–302. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00297.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So HC, Chen RY, Chen EY, Cheung EF, Li T, Sham PC. An association study of RGS4 polymorphisms with clinical phenotypes of schizophrenia in a Chinese population. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B(1):77–85. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Behav Rev. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. Adolescent brain development and animal models. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1021:23–26. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel C, Haworth EJ, Peters E, Hemsley DR, Sharma T, Gray JA, Pickering A, Gregory L, Simmons A, Bullmore ET, Williams SC. Neuroimaging correlates of negative priming. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3619–3624. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200111160-00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub RE, MacLean CJ, Ma Y, Webb BT, Myakishev MV, Harris-Kerr C, Wormley B, Sadek H, Kadambi B, O’Neill FA, Walsh D, Kendler KS. Genome-wide scans of three independent sets of 90 Irish multiplex schizophrenia families and follow-up of selected regions in all families provides evidence for multiple susceptibility genes. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:542–559. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultana R, Yu CE, Yu J, Munson J, Chen D, Hua W, Estes A, Cortes F, de la Barra F, Yu D, Haider ST, Trask BJ, Green ED, Raskind WH, Disteche CM, Wijsman E, Dawson G, Storm DR, Schellenberg GD, Villacres EC. Identification of a novel gene on chromosome 7q11.2 interrupted by a translocation breakpoint in a pair of autistic twins. Genomics. 2002;80(2):129–134. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvisaari J, Haukka J, Tanskanen A, Hovi T, Lonnqvist J. Association between prenatal exposure to poliovirus infection and adult schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(7):1100–1102. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.7.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkachev D, Mimmack ML, Ryan MM, Wayland M, Freeman T, Jones PB, Starkey M, Webster MJ, Yolken RH, Bahn S. Oligodendrocyte dysfunction in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2003;362:798–805. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uematsu M, Kaiya H. Midsagittal cortical pathomorphology of schizophrenia: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Psychiatry Res. 1989;30(1):11–20. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voineskos AN, de Luca V, Bulgin NL, van Adrichem Q, Shaikh S, Lang DJ, Honer WG, Kennedy JL. A family-based association study of the myelin-associated glycoprotein and 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase genes with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Genet. 2008;18(3):143–146. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e3282fa1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan C, Yang Y, Feng G, Gu N, Liu H, Zhu S, He L, Wang L. Polymorphisms of myelin-associated glycoprotein gene are associated with schizophrenia in the Chinese Han population. Neurosci Lett. 2005;388(3):126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter C, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD, Sohr R, Wolf RJ, Juckel G, Fatemi SH. Dopamine and serotonin levels following prenatal viral infection in mouse--implications for psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and autism. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18(10):712–716. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YF, Qin W, Shugart YY, He G, Liu XM, Zhou J, Zhao XZ, Chen Q, La YJ, Xu YF, Li XW, Gu NF, Feng GY, Song H, Wang P, He L. Possible association of the MAG locus with schizophrenia in a Chinese Han cohort of family trios. Schizophr Res. 2005;75(1):11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.