Abstract

The lithium diisopropylamide (LDA)-mediated condensation of 2-fluoro-3-picoline and benzonitrile to form 2-phenyl-7-azaindole via a Chichibabin cyclization is described. Facile dimerization of the picoline via a 1,4-addition of the incipient benzyllithium to the picoline starting material and fast 1,2-addition of LDA to benzonitrile cause the reaction to be complex. Both adducts are shown to reenter the reaction coordinate to produce the desired 7-azaindole. The solution structures of the key intermediates and the underlying reaction mechanisms are studied by a combination of IR and NMR spectroscopies.

Introduction

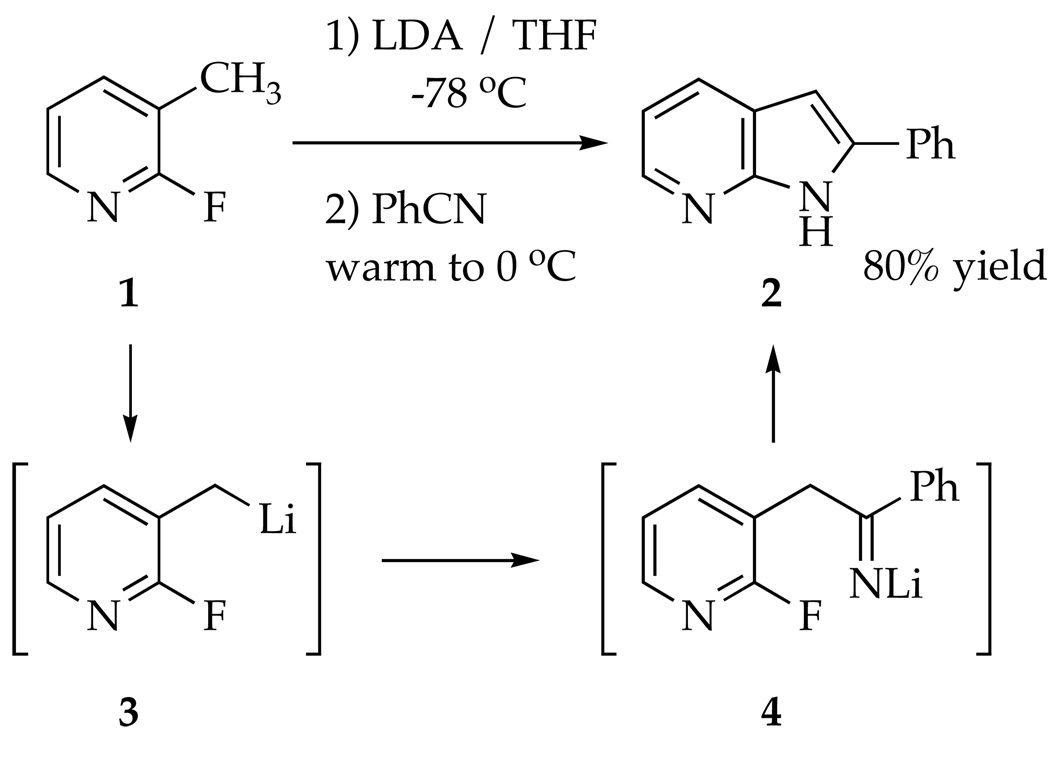

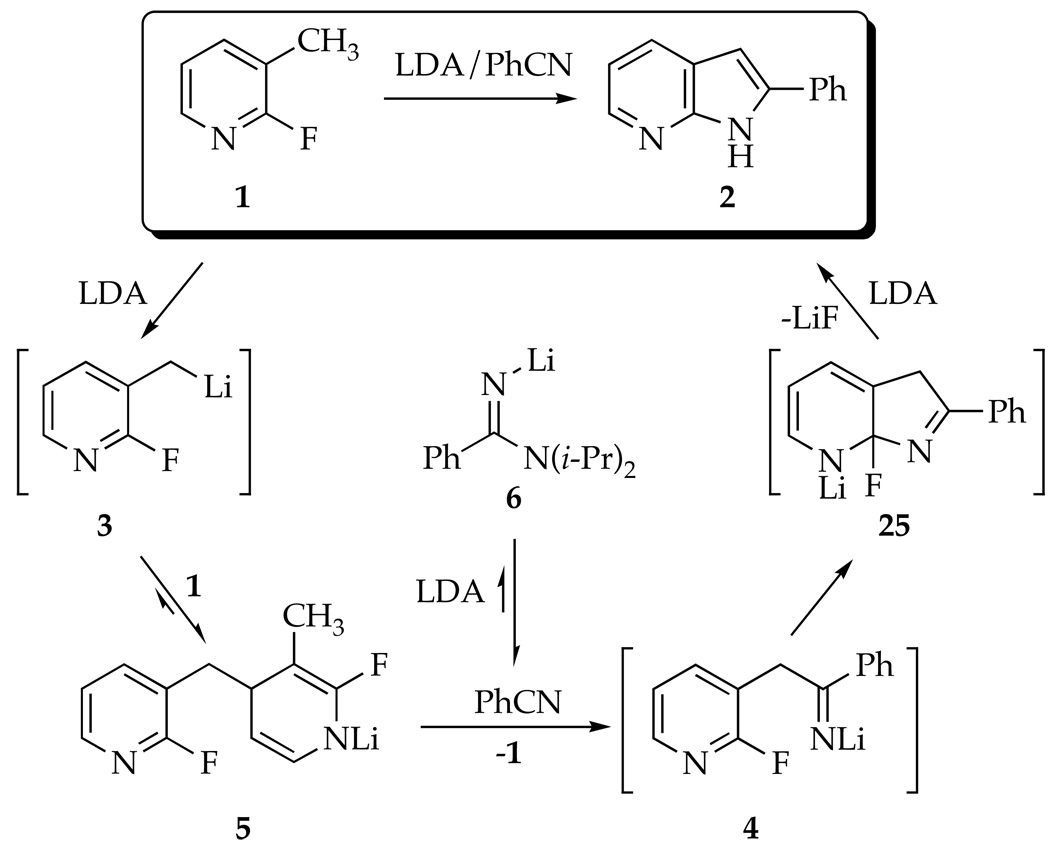

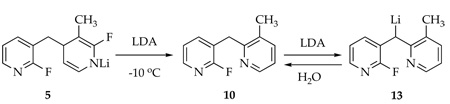

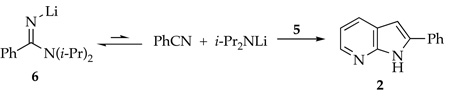

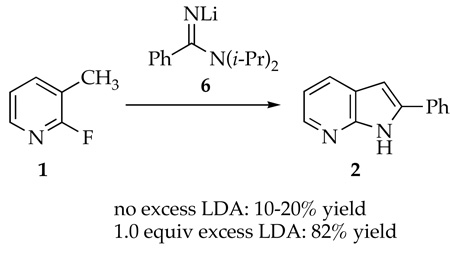

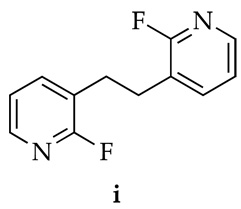

7-Azaindoles have been found to be therapeutically active for an array of maladies.1 The primary synthetic challenge presented by azaindoles reduces to one of heteroannulation--appending a pyrrole to a pyridine or vice versa.1,2 In connection with a program at sanofi-aventis to synthesize polycyclic pyrrole derivatives to be tested for the treatment of asthma,2c the conversion of 2-fluoro-3-picoline (1) to 7-azaindole 2 was examined (Scheme 1). The procedure was modeled after that of Wakefield and coworkers in which metalation of 3-picoline and subsequent addition of benzonitrile (PhCN) affords 7-azaindole 2 in one pot.3 The key cyclization of putative intermediate 4 to 2 corresponds to a Chichibabin reaction--the nucleophilic addition of an alkali metal amide to a pyridine.4,5 Substitution of the fluoro moiety precludes an air oxidation required by standard Chichibabin protocols. The fluorine does not improve the yield, but 19F NMR spectroscopy proves to be particularly useful to study the reaction.6

Scheme 1.

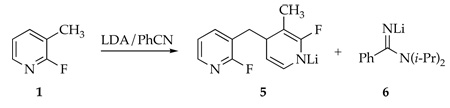

The Cornell group was charged with studying the underlying structural and mechanistic organolithium chemistry. The results are particularly odd owing to non-fatal condensations of benzyllithium 3 with picoline 1 and of LDA with PhCN (eq 1), which leave none of the original reagents intact. We examined how adducts 5 and 6 form and reenter the reaction coordinate to provide azaindole 2 in high yield. The results are summarized at the beginning of the discussion section for the benefit of the non-specialist. The importance of dimerizations during lithiations of heterocycles is discussed in a broader context.

|

(1) |

Results

Azaindole Synthesis

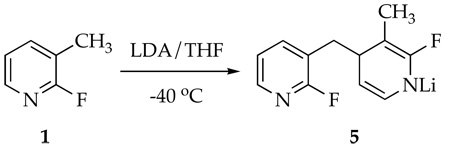

The conversion of fluoropicoline 1 to azaindole 2 proceeds smoothly by sequential addition of picoline 1 to 2.1 equiv of LDA in THF at −40 °C. After 60 min, addition of 1.2 equiv of PhCN to the blood-red reaction with stirring for an additional 2.0 h at −40 °C affords 2 in 80% yield. Alternatively, reversing the order of addition--adding 1.05 equiv PhCN to 2.1 equiv LDA at −40 °C followed by 1.0 equiv fluoropicoline 1--affords azaindole 2 in 82% yield. An inferior (15–20%) yield of 2 is obtained if only 1.05 equiv of LDA is used. The second equivalent may be required for a tautomerization following the cyclization of 4. No ketone derived from hydrolysis of putative intermediate 4 could be observed despite prompt aqueous quenches at low temperature.

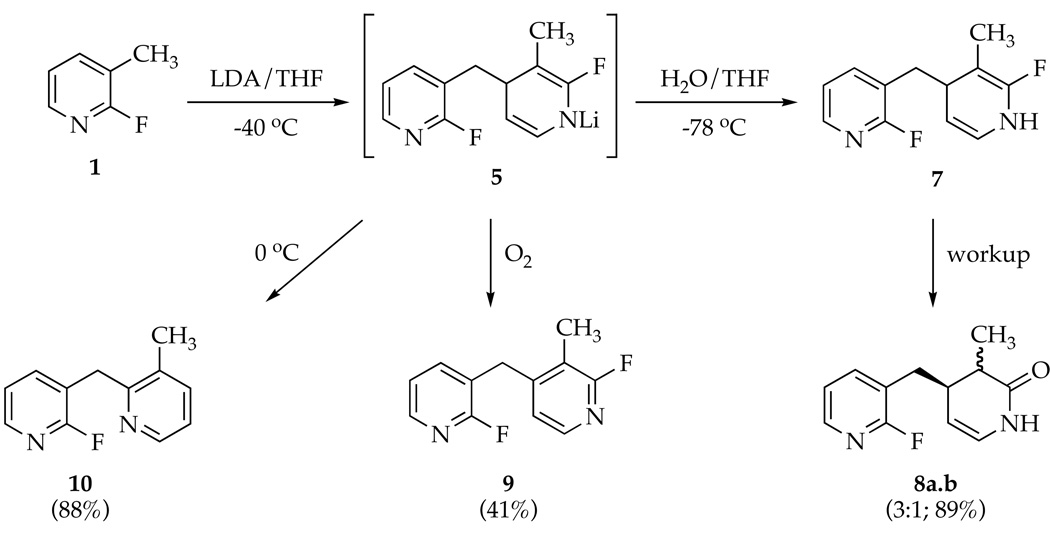

Byproducts Derived from Picoline Dimerization

A number of byproducts emerged during the optimizations that attest to picoline dimerizations.7 The byproducts, prepared in optimized yields as illustrated in Scheme 2, foreshadow an underlying mechanistic complexity. They were characterized by a combination of 1H, 13C, 19F, [1H,13C]HMBC, [1H,13C]HSQC, [1H,1H]COSY, and [1H,19F]J-resolved spectroscopies, IR spectroscopy, and mass spectrometry (supporting information).

Scheme 2.

Lithiating 1 at −40 °C followed by quenching with wet THF at −78 °C affords 7, the product of 1,4-addition of benzyllithium 3 to picoline 1, as a transiently stable intermediate.8 Dihydropyridine 7 displays vinyl 1H resonances at δ 5.87 and 4.06 ppm characteristic of the enamino moiety as well as a 1:1 pair of 19F resonances at δ −70.1 and −114.8 ppm. Whereas the 19F resonance at δ −70.1 ppm is consistent with a fluoropyridine moiety,9 the resonance at δ −114.8 ppm is decidedly upfield. Aqueous workup of 7 affords a 3:1 mixture of lactams 8a and 8b isolated in 89% combined yield along with traces of 9 (11%). Lactams 8a and 8b were separated, but their stereochemistries were not assigned. Presumably 8a and 8b result from hydrolysis of fluorodihydropyridine 7 whereas 9 derives from its air oxidation. The yield of 9 increases to 41% by adding O2 at −40 °C prior to the aqueous quench.10 If solutions of 1 and LDA are warmed to 0 °C prior to an aqueous quench, product 10 resulting from dimerization by a 1,2-addition is isolated in 88% yield.11–13

Origins of 1,4-Adducts

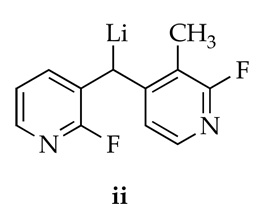

Metalation of 1 by 1.0 equiv of [6Li,15N]LDA affords lithiated dihydropyridine 5 (eq 2) of unknown aggregation number. 6Li NMR spectroscopy reveals the resonance corresponding to unreacted LDA dimer 1114,15 along with a single resonance displaying no 6Li-15N coupling, initially presumed to derive from lithiated picoline 3. The 19F NMR spectra, however, display two resonances in a 1:1 proportion at markedly different chemical shifts (δ −93.5 and −70.5 ppm).16 A combination of 19F and 1H NMR spectroscopies showed coupling patterns fully consistent with 5 (eq 2); vinyl resonances at 5.83 and 3.80 ppm are especially characteristic of the lithioimine moiety. At no point did we observe resonances corresponding to 9 (or a lithiated counterpart17), confirming that 9 forms during workup.

|

(2) |

The underlying mechanism of the dimerization is shown to involve rate-limiting picoline metalation with a subsequent rapid dimerization; details of the rate studies are described in the experimental section.18 The idealized19 rate law (eq 3), in conjunction with the assignment of LDA/THF as a disolvated dimer 11,14,15 is consistent with lithiation via a tetrasolvated monomer-based transition structure, which we offer 12. The third-order dependence on the THF concentration (measured 2.9 ± 0.2) was surprising. Precedent suggests that the THF order could include secondary-shell solvation effects.20 Nonetheless, using 2,2,5,5-Me4THF as a polar, but chemically inert cosolvent afforded no reduction in the THF order.20 Evidence of high coordinate lithium support such a highly solvated transition structure as possible.21 The depicted Li-F interaction is supported by evidence that such Li-F interactions are highly stabilizing.22 With that said, the solvation number and existence of an Li-F interaction in 12 should be viewed with a healthy skepticism.

| (3) |

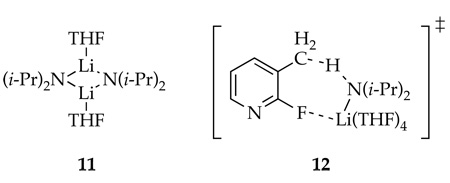

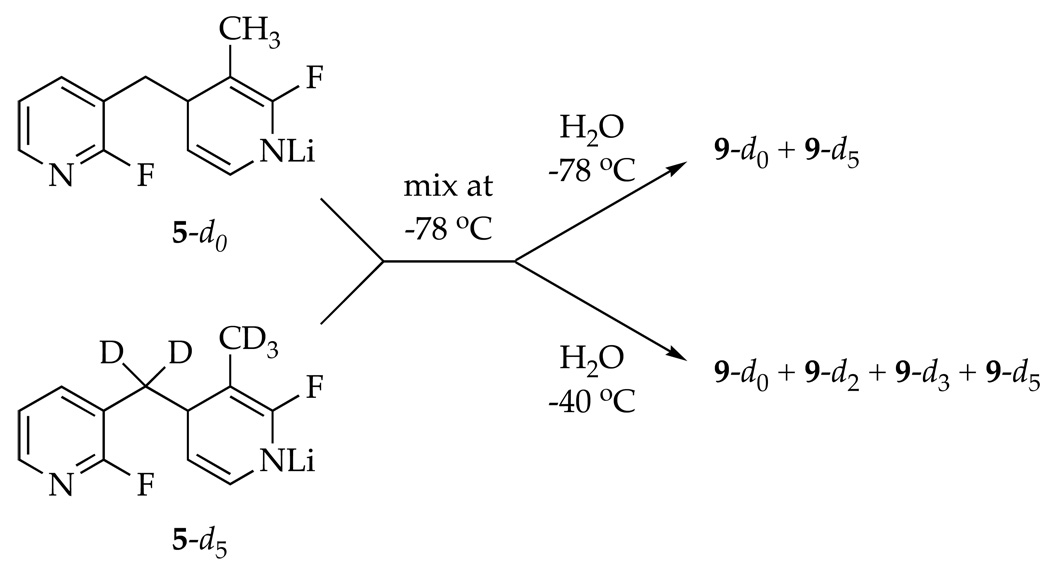

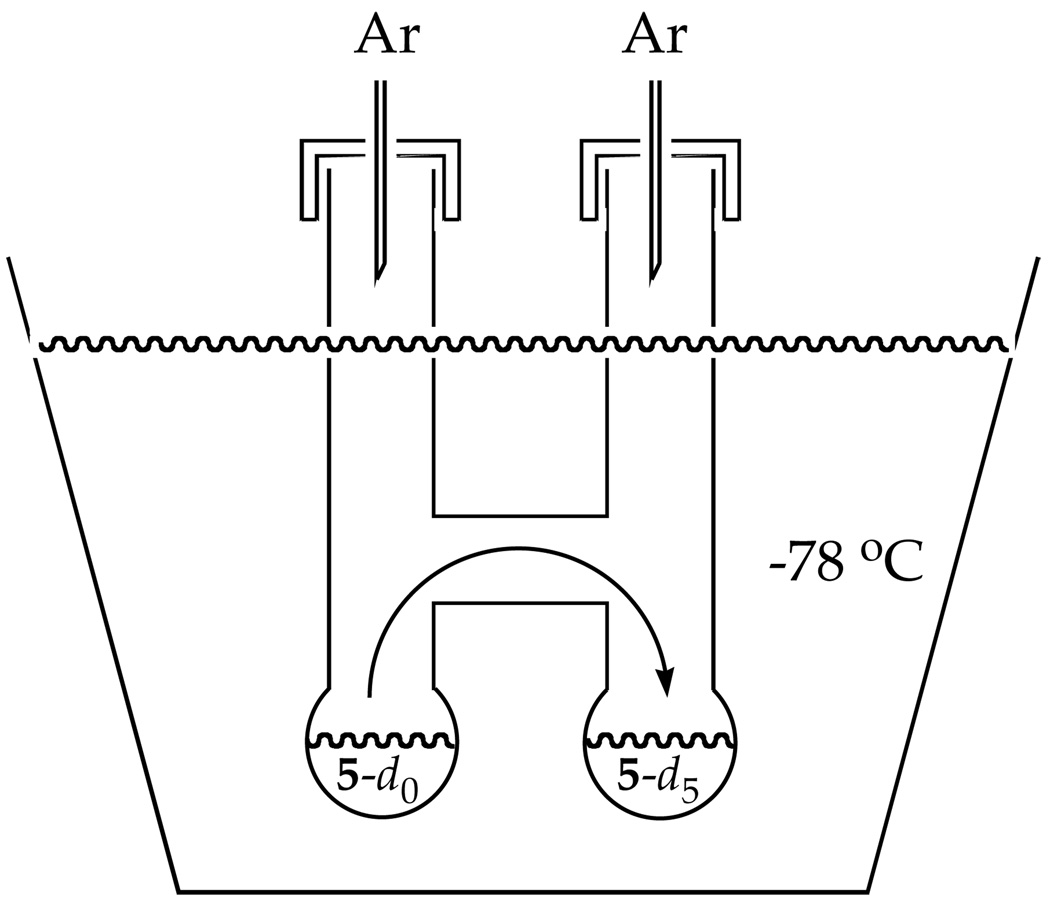

Reversible formation of 5 was demonstrated by a double-crossover study summarized in Scheme 3.23 Mixing independently prepared samples of 5-d0 and 5-d5 at −78 °C and quenching after 10 min afforded a mixture of 9-d0 and 9-d5 contaminated with only traces (<5%) of crossover products 9-d2 and 9-d3 as shown by GC-MS analysis. (The low levels of crossover are probably elicited by inadvertent warming.) Warming to −40 °C affords an approximate statistical distribution.24 Therefore, the 1,4-addition to form 5 is reversible under the conditions of the metalation of picoline 1 (−40 °C) and the rearrangement to form 10 (0 °C), but not at low temperatures. This temperature dependence proves to be important (vide infra).25

Scheme 3.

Origins of 1,2-Adduct 10

Warming solutions of lithiated dihydropyridine 5 to 0 °C--conditions affording 1,2-adduct 10 in high yield (eq 4)--causes the 19F resonances of 5 to disappear via a first-order decay.26,27 A single 19F resonance at δ −77.9 ppm corresponding to a lithiated form of 10 (presumably 13) appears concomitantly. Quenching affords 10 (δ −70.9 ppm). Treating a purified sample of 10 with LDA causes the resonance of 13 at δ −77.9 ppm to reappear. The approximate first-order decay of 5 and the crossover experiments are congruent with formation of 10 via benzyllithium 3.28

|

(4) |

Condensation of Lithiated Dihydropyridine 5 with PhCN

Monitoring the solutions containing PhCN, 5 and residual LDA (0.5 equiv relative to starting picoline 1) using 19F NMR spectroscopy shows the disappearance of picoline 1 at −40 °C. Adduct 2 (or its lithium salt) is not detectable by 19F NMR spectroscopy. An absence of fluorine-containing intermediates suggests that cyclization of imidolithium 4 to afford azaindole 2 is very fast.29

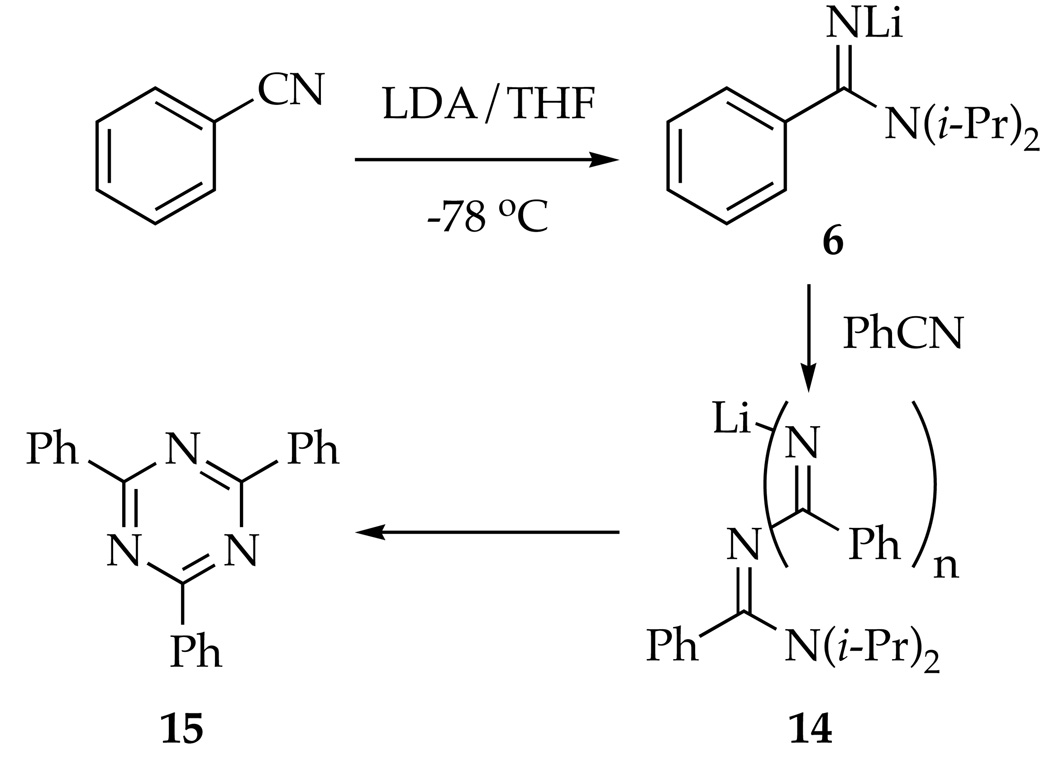

Condensation of LDA with PhCN

Monitoring the reaction described above using in situ IR spectroscopy30 shows that PhCN disappears with a 3 min half life at −78 °C (<<1 min at −40 °C.) This is substantially faster than the loss of 5. This loss of PhCN was traced to the condensation of the remaining LDA (0.5–1.5 equiv; not shown) to form amidinolithium 6 as the first step of a cascade of reactions leading to PhCN trimer 15 (Scheme 4).31–33 Indeed, warming a mixture of 6 and PhCN to 0 °C affords an intensely purple solution (appearing black), which affords PhCN-derived trimer 15 in 83% yield. Base-mediated trimerizations of arylnitriles have been reported previously.31,32

Scheme 4.

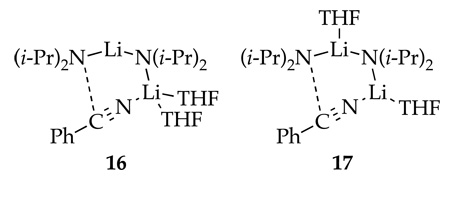

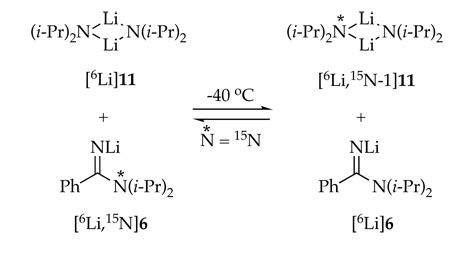

The condensation of LDA and PhCN is important because it affords 6 substantially faster than the metalation of 1 by LDA. We examined the kinetics by monitoring the loss of PhCN (2230 cm−1) and the formation of amidinolithium 6 (1627 cm−1) as described in the experimental section. The first term in the resulting rate law in eq 5 is consistent with open dimer-based transition structures 16 or 17.18,34 (The reaction rate at low THF concentrations was too high to measure the LDA order in the second term of eq 5.)

| (5) |

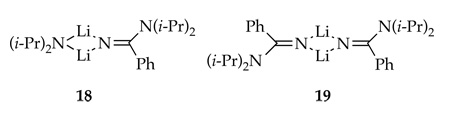

Monitoring equimolar mixtures of PhCN and [6Li,15N]LDA35 by 6Li and 15N NMR spectroscopy reveals the conversion of LDA dimer 11 sequentially to heterodimer 18 and homodimer 19. Heterodimer 18 displays a characteristic 6Li doublet arising from coupling to one labeled LDA fragment.15,36 The 15N spectrum of 18 shows the LDA fragment as a broad mound and the C(=NLi)15N(i-Pr)2 moiety as a sharp singlet. Homodimer 19 displays 6Li and 15N singlets. (The resonances corresponding to the C(=NLi)15N(i-Pr)2 moieties of 18 and 19 appear to superimpose.) In a complementary experiment, equimolar mixtures of [15N]PhCN and [6Li]LDA affords 18 displaying a 6Li doublet and 15N mound and 19 as a 6Li triplet and 15N mound. Crystal structures of related unsolvated amidinolithium derivatives37 are prismatic higher oligomers. (The broad 15N resonances associated with 18 and 19 may derive from further oligomerization of the amidinolithium 6 described below.)

Addition of LDA to PhCN appears to be reversible albeit slowly. Thus, [6Li]LDA (as disolvated dimer 11)14 was added to a solution containing [6Li,15N]6 (labeled on the N(i-Pr)2 of the amidino moiety) kept below −90 °C. On warming the probe crossover begins to occur at −40 °C as exemplified by the appearance of 15N coupling in LDA dimer 11 (and heterodimer 18). Crossover requires approximately 50 min to proceed to completion (coinciding with the appearance of oligomer 14 described above.) The similar conditions affording crossover and conversion of mixtures of 5 and 6 to azaindole 2 is probably not a coincidence.

|

(6) |

Chichibabin Cyclization using Amidinolithium 6

Solutions containing amidinolithium 6 at −40 °C--conditions affording Chichibabin cyclization--also cause further oligomerization of 6 (actually homodimer 19) to a new species with a slightly downfield-shifted 6Li resonance that we attribute to oligomer(s) 14. (Possible intermediates in PhCN trimerizations have been discussed by Wheatley and coworkers.32) Monitoring Chichibabin cyclizations by 6Li NMR spectroscopy reveal that 6 and 14 form but then reenter the reaction coordinate (although more reluctantly for 14).

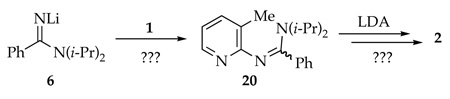

The most logical explanation for the success of the protocol in eq 1 is that that 6 and 14 form reversibly (eq 7). We did, however, consider alternative models. In principle, 6 could condense with 1 via 1,2-addition to form 20 with subsequent LDA-mediated cyclization (eq 8). Nonetheless, addition of picoline 1 to a nearly LDA-free solution of 6 (prepared in situ) shows very little loss of starting material and <20% yield of azaindole 2 (eq 9). Amidinolithium 6 does not react with the relatively unhindered 2-fluoropyridine at −40 °C. Therefore, adduct 20 is not likely to be an intermediate en route to 2. Alternatively, the cyclization shown in eq 1038 and nucleophilic additions of alkyllithiums to imidolithiums of general structure ArN=C(OLi)R39 suggest that 6 could, in theory, be the key electrophile. Nonetheless, 6 certainly does not have the trappings of a good electrophile.

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

|

(9) |

|

(10) |

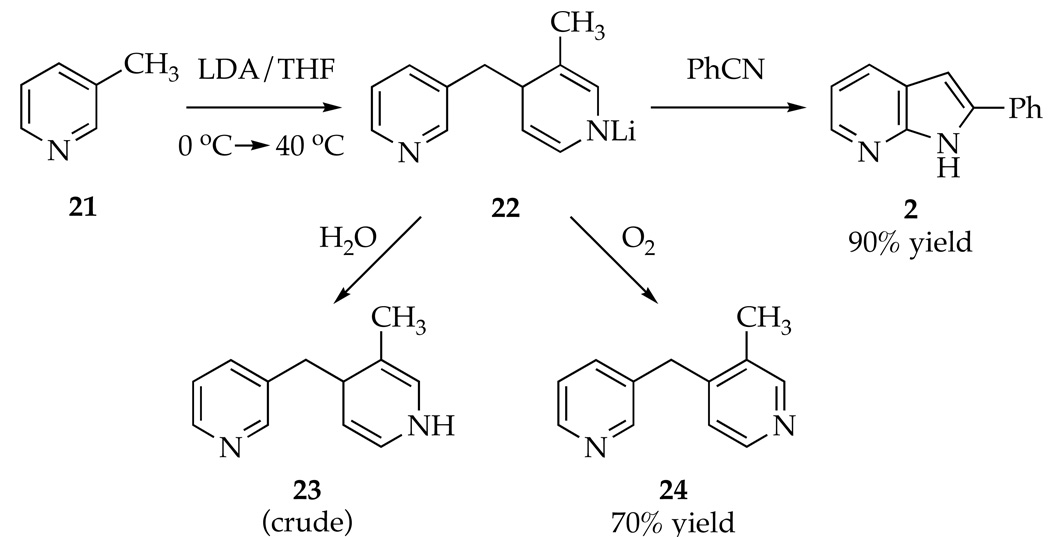

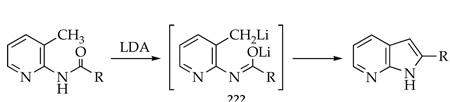

Chichibabin Cyclization Using 3-Picoline

To ascertain the role of the 2-fluoro moiety in 1 we briefly investigated the metalation of 3-picoline (21). As described by Wakefield and coworkers,3 treatment of 21 with 3.3 equiv of LDA at 0 °C followed by addition of PhCN with subsequent warming to 40 °C affords azaindole 2 in 90% yield (Scheme 5). Cursory rate studies using IR spectroscopy following the loss of 21 (1575 cm−1) show that 21 is at least 20-fold less reactive than 1, lithiating smoothly only on warming to 10 °C. 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis was thwarted by precipitation. Metalation of 21 in the absence of PhCN affords 22 as a bright yellow solid that could be isolated, but resisted spectroscopic characterization due to insolubility in THF.40 Quenching the yellow solid with THF-d8/H2O (40:1) afforded dihydropyridine 23 in ϩ0% spectroscopic purity that was surprisingly stable to further hydrolysis. Alternatively, treatment of the yellow solid suspended in THF with O2 followed by standard aqueous workup afforded aromatized dimer 24 (70% yield) previously detected by Goto and coworkers.41

Scheme 5.

Discussion

In the context of studies of 7-azaindoles and related bicyclic pyrrole-based heterocycles being carried out at sanofi-aventis,2c we investigated the Chichibabin cyclization illustrated in Scheme 1. Although the design is a straightforward adaptation of a protocol used by Wakefield and coworkers,3 the underlying organolithium chemistry is peculiar, and the potential ramifications are consequential. The results are summarized in the context of Scheme 2 and Scheme 6 as follows.

Scheme 6.

Summary

Sequential treatment of fluoropicoline 1 with LDA (2.0 equiv) and PhCN affords azaindole 2 in excellent (80–85%) yield. The order of mixing has no effect on the yield as long as the reaction is kept at ≤−40 °C. Products resulting from the condensation of benzyllithium 3 with fluoropicoline 1 offer a glimpse of underlying complexity (Scheme 2). Quenching solutions of LDA and 1 with H2O affords transiently stable (but fully characterized spectroscopically) dihydropyridine 7, which is converted to lactams 8a,b and traces of air oxidized dimer 9 on workup. Warming prior to quenching affords net 1,2-adduct 10 in high yield. Monitoring the reaction by 19F NMR spectroscopy reveals lithiated dihydropyridine 5 in >95% purity to the exclusion of benzyllithium 3. Rate studies show that 5 forms by a rate limiting metalation of 1 via highly solvated LDA monomer (see 12). Adding PhCN to solutions of 5 shows no fluorine-containing intermediates. The extruded 0.5 equiv of 1 reenters the reaction coordinate, as required by the high yields of 2.

Concurrent with the dimerization of picoline 1, LDA undergoes reversible condensation with PhCN to form amidinolithium 6, which exists as hetero- and homodimers 18 and 19. Rate studies reveal an LDA dimer-based mechanism via 16 or 17.15 If adduct 6 stands for several hours or is warmed above −40 °C, further oligomerization occurs, eventually affording trimer 15 (Scheme 4).31,32 Provided the cascade leading to 15 is not allowed to occur, formation of amidinolithium 6 does not preclude formation of azaindole 2.

The peculiarity of the Chichibabin cyclization is underscored by an inverse addition in which LDA and PhCN are mixed prior to addition of picoline 1 (eq 1): None of the original reagents are present in the vessel. Yet, somehow 5 and 6 are readily converted to azaindole 2. The simplest explanation is that 5 and 6 form reversibly. The conversion of 1,4-adduct 5 to 1,2-adduct 10 certainly hints at reversible addition (although 10 could, in principle, arise from an accelerated 1,3-sigmatropic rearrangement.)42 Crossover studies show that 5 does indeed form reversibly at −40 °C--conditions of the Chichibabin cyclization.

Ascertaining how amidinolithium 6 re-enters the reaction coordinate proved challenging. Crossover studies showed that i-Pr2N moiety of 6 exchanges with free LDA. However, the conclusion that 6 extrudes free PhCN is assailable. The conditions that elicit exchange of LDA with amidinolithium 6 are relatively forcing and the extent of crossover limited. Moreover, the LDA exchange could, at least in principle, proceed by a nucleophilic addition rather than by dissociation of PhCN. We considered the possibility that 6 acts as a nucleophile toward 2-fluoropyridino moieties (eq 8) or even as an electrophile, but found no support.

Consequences of Picoline Dimerization

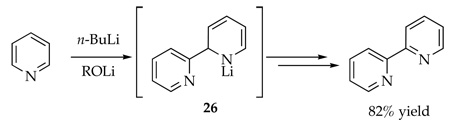

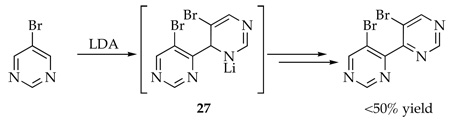

Optimized yields for metalation and functionalization of the nitrogen-based heterocycles can be highly substrate and electrophile dependent.5 In the case of the Chichibabin cyclization in Scheme 1, self-condensation of picoline 1 to form 5 ties up 50% of the starting picoline in the form of a lithiated dihydropyridino moiety, which also leaves residual LDA free to form adduct 6. Fortunately, neither of these chemical culde-sacs proves fatal. We got lucky. If one had used a different electrophile, however, the formation of 5 might not be benign. As a simple example, using H3O+ (or D3O+) as an electrophile affords dihydropyridine 7. If the goal had been to deuterate the benzylic position of 1, formation of 5 causes total failure.43 The dichotomous behavior of PhCN and D2O may be important to those interested in metalating picolines, pyridines, and related nitrogen-based heteroaromatics.5 One wonders, for example, how many reactions relying on ortho or benzylic metalations of aromatic heterocycles provide poor yields or completely fail because of self-condensations. There are anecdotal reports of 1,2- and 1,4-adducts as byproducts in metalations44–51 such as in pyridines (eq 11)48,49 and pyrimidines (eq 12).51 We do not know how many dimer-derived byproducts are buried in the enormous literature of heterocycles beyond our gaze. There may be many unpublished examples in pharmaceutical research labs and many more that have simply gone undetected.

|

(11) |

|

(12) |

We do not fully understand the consequences of dimerization. The self-condensation of 3-picoline (21, Scheme 5) is a particularly disturbing case in point. Wakefield3 and others52 obtained excellent results metalating and functionalizing 21. It seems unlikely that they suspected the intermediacy of 1,4-adduct 22. We believe that some attempts to functionalize 21--there may very well be many unreported--have been frustrated by either the failure of electrophiles to react with 22 or by the incompatibility of the electrophiles with excess base lurking in solution.53 One group attributes such a failure to the high pKA of 2154 whereas another group reports the pKA of 21 without realizing that 21 had dimerized.55 Are picoline dimers 5 and 22 as well as other putative dimers such as 26 and 27 problematic side products, or are they key intermediates en route to desired functionalizations 49,56

Conclusions

Nearly half of the top twenty largest selling pharmaceutical agents contain a pyridine or pyridine-like ring.57 One of us (DBC) once spent an entire day at a major pharmaceutical company discussing exclusively a number of problematic pyridine metalations. There is little doubt that the metalations and subsequent functionalizations of pyridines present important and confounding challenges.

Despite self condensation of 1 to form 5 and consequent condensation of leftover LDA with PhCN to form amidinolithium 6, the Chichibabin cyclization in eq 1 works remarkably well. A colleague astutely noted that 5 is, in essence, a protected benzyllithium, in which half of the starting picoline 1 is consumed as the protecting group. Thus, although one might view base-mediated self condensations of heteroaromatics as annoying side reactions to be avoided, maybe they should be embraced and exploited.

Experimental Section

Reagents and Solvents

THF, hexane, and pentane were distilled from blue or purple solutions containing sodium benzophenone ketyl. The hydrocarbon stills contained 1% tetraglyme to dissolve the ketyl. LDA, [6Li]LDA, and [6Li,15N]LDA35 were purified as crystalline solids using recrystallized n-BuLi.58 Air- and moisture sensitive materials were manipulated under argon or nitrogen using standard glove box, vacuum line, and syringe techniques. Solutions of n-BuLi and LDA were titrated using a literature method.59

NMR Spectroscopic Analyses

Samples for monitoring reactions using NMR spectroscopy were prepared by layering stock solutions at −196 °C, sealed under partial vacuum, and warmed to −78 °C. The samples were vigorously shaken in a −78 °C bath for about 30 s and then transferred to the NMR probe for acquisition of spectra. Standard 6Li, 13C, 15N, and 19F NMR spectra were recorded on a 500 MHz spectrometer at 76.73, 125.79, 50.66 and 470.35 MHz (respectively). The 6Li, 13C, 15N, and 19F resonances are referenced to 0.30 M [6Li]LiCl/MeOH at −90 °C (δ 0.0 ppm), the CH2O resonance of THF at −90 °C (δ 67.57 ppm), neat Me2NEt at −90 °C (δ 25.7 ppm), and C6F6 in neat THF at −90 °C (δ -162.5 ppm), respectively.

In situ preparation of dimer 5

A 1.6 M solution of n-butyllithium (1.33 mL, 2.1 mmol) in hexanes was added via syringe to dry THF (20.0 mL) at −40 °C under inert Ar atmosphere. Dry diisopropylamine (310 µL, 224 mg, 2.1 mmol) was added to the solution via syringe. After stirring for 5 min at −40 °C, 3-methyl-2-fluoropyridine 1 (200 µL, 220 mg, 2.0 mmol) was added to the LDA solution. The solution became a bright red as N-lithiodihydropyridine 5 forms over the course of 1.0 h. Carrying out an analogous procedure in an NMR tube using THF-d8 affords the following spectroscopic data: 1H NMR (THF-d8, −78 °C) δ 1.60 (d, JH,F=1.4 Hz, 3H), 2.43 (dd, JH,H=12.4, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.77 (dd, JH,H=12.4, 3.5Hz, 1H), 3.50 (ddd, JH,F=3.7, JH,H=6.7, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 3.69 (dddd, JH,F=6.8, JH,H=7.2, 3.4, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 5.84 (dd, JH,F=2.0, JH,H=6.7 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (dddd, JH,F=2.1, JH,H=7.0, 4.7, 0.4 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (ddd, JH,F=9.5, JH,H=7.0, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.96 (ddm, JH,H=4.7, 2.1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (THF-d8, −78 °C) δ 20.1 (d, JC,F=22.3 Hz), 47.0 (d, JC,F=6.6 Hz), 69.7 (d, JC,F=29.0 Hz), 80.1 (d, JC,F=7.0 Hz), 91.4, 121.6, 123.4 (d, JC,F=31.7 Hz), 139.3 (d, JC,F=21.8 Hz), 143.4 (d, JC,F=6.6 Hz), 144.7 (d, JC,F=15.0 Hz), 163.0 (d, JC,F=215.0 Hz), 163.3 (d, JC,F=235.0 Hz); 19F NMR (THF-d8, −78 °C) δ −93.5, −70.5; 6Li NMR (THF-d8, −78 °C) δ −0.01, 0.76.

Synthesis of Dihydropyridine 7

A solution of N-lithiodihydropyridine 5 (0.05 M) at −40 °C prepared in THF-d8 as described above was quenched by THF-d8–H2O at −78 °C to afford dihydropyridine 7. The N-H proton is not observable at 0 °C; spectra were recorded on 7 in situ at −70 °C: 1H NMR (THF-d8) δ 1H NMR (THF-d8) 1.61 (d, J=2.3Hz, 3H), 2.54 (m, 1H), 2.87 (m, 1H), 3.30 (m, 1H), 4.06 (dd, J=8.0, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 5.87 (dt, J=8.0, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (tt, J=7.0, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (br, 1H), 7.67 (dt, J=7.0, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.03 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (THF-d8) δ 11.5, 35.2, 41.5 (dd, J=4.0, 1.9 Hz), 80.7, 98.3, 121.8, 122.0, 126.2, 142.8, 145.3, 149.6, 162.8.

Synthesis of Azaindole 2

To a solution of N-lithiodihydropyridine 5 (0.05 M) at −40 °C prepared as described above was added benzonitrile (250 µL, 253 mg, 2.45 mmol). After stirring at −40 °C for 2 h the vessel was warmed to 0 °C for 30 min, the reaction was quenched with wet THF. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting yellow solid was redissolved in EtOAc (15 mL), and the organic layer was washed with aqueous NaHCO3 (3×10 mL) and aqueous NaCl (3×10 mL). The organic layer was dried with Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The bright yellow solid was recrystallized from 1:4 ethyl acetate:hexane or, alternatively, flash chromatographed eluting with 2:1 ethyl acetate:hexanes. Compound 2 (310 mg, 1.60 mmol) was isolated as an off-white solid in 80% yield. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 6.90 (s, 1H), 7.05 (dd, J=7.8, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (tt, J=7.3, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (t, J=7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.91 (dd, J=7.9, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.96 (dd, J=7.8, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 8.24 (dd, J=1.6, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 12.23 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 97.1, 116.0, 121.0, 125.4, 127.8, 128.0, 128.9, 131.7, 138.3, 142.9, 149.8. HRMS [C13H10N2] requires m/z 194.0844. Found: 194.0839.

Synthesis of Azaindole 2: Inverse Addition

A 1.6 M solution of n-butyllithium (2.66 mL, 4.2 mmol) in hexanes was added via syringe to dry THF (20.0 mL) at −40 °C under inert Ar atmosphere. Dry diisopropylamine (620 µL, 448 mg, 4.2 mmol) was added to the solution via syringe. After stirring for 5 min at −40 °C, benzonitrile (215 µL, 217 mg, 2.1 mmol) was added. After stirring at −40 °C for 2 h, and fluoropicoline 1 (200 µL, 220 mg, 2.0 mmol) was added and stirring was continued for 2 more hours. Workup and purification as described above afford 2 (320 mg, 1.65 mmol) as an off-white solid in 82% yield.

Synthesis of 8a and 8b

A solution of N-lithiodihydropyridine 5 (0.05 M) at −40 °C prepared as described above was cooled to −78 °C and quenched with THF/water (40:1, 10.3 mL) dropwise via syringe. After warming to rt, the solvent was evaporated in vacuo. The resulting residue was redissolved in EtOAc (15 mL), and the organic layer was washed with aqueous NaHCO3 (3×10 mL) and aqueous NaCl (3×10 mL). The organic extract was dried with Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. Flash chromatography (2:1 ethyl acetate:hexanes) afforded lactams 8a,b as a colorless liquid (196 mg, 0.89 mmol) in 89% yield. HPLC separation (degassed 5:1 pentane:diethyl ether) afforded analytically pure 8a and 8b for spectroscopic analysis. 8a: 1H NMR (acetone-d6) δ 1.20 (d, J=7.2 Hz, 3H), 2.49 (dd, J=13.0, 10.4 Hz, 1H), 2.63 (d, J=6.7 Hz, 1H), 2.75–2.81 (d, J=5.1 Hz, 1H), 2.82–2.86 (m, 1H), 2.86 (br s, 1H), 4.80 (dd, J=8.0, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (dd, J=7.7, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (tdd, J=6.1, 2.1, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.77–7.84 (m, J=8.8, 2.4, 1.7, 1H), 8.05–8.09 (m, J=5.2, 1H); 13C NMR (acetone-d6) δ 11.5, 28.9 (J=3.1); 37.5 (J=1.1), 40.1, 107.5, 122.6 (J=4.3), 122.8 (J=31.1), 126.6, 143 (J=5.6 Hz), 146.33 (J=15.4 Hz), 163 (J=235.4 Hz), 173.27; 19F NMR (acetone-d6) δ -74.5 (d, J=9.4); HRMS [C12H13N2OF] requires m/z 220.1012. Found: 220.1003; IR (film, cm−1): 1698, 1661, 1605, 1578, 1438. 8b: 1H NMR (acetone-d6) δ 1.19 (d, J=7.2 Hz, 3H), 2.30 (d, J=7.0 Hz, 1H), 2.45–2.52 (m, 1H), 2.64–2.71 (m, 1H), 2.76–2.82 (m, 1H), 2.84 (br s, 1H), 4.84 (dd, J=7.8, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (dd, J=7.7, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (tdd, J=6.1, 2.1, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.77–7.84 (m, 1H), 8.05–8.09 (d, J=5.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (acetone-d6) δ 11.5, 28.7 (J=3.1), 37.5 (J=1.1 Hz), 40.1, 107.4, 122.6 (J=4.3 Hz), 122.8 (J=31.1 Hz), 126.5, 142.9 (J=5.6 Hz), 146.33 (J=15.4 Hz), 162.97 (J=235.4 Hz), 173.3; 19F NMR (acetone-d6) δ −73.9 (d, J=9.1 Hz); IR (film, cm−1): 1698, 1661, 1605, 1578, 1438. HRMS [C12H13N2OF] requires m/z 220.1012. Found: 220.1028.

Synthesis of 9

A solution of N-lithiodihydropyridine 5 (0.05 M) at −40 °C prepared as described above was cooled to −78 °C and purged with gaseous O2. After stirring at −78 °C for 4 h, the reaction was quenched with a THF/water mixture (40:1, 10.3 mL). Water (250 µL, 250 mg) in THF (10 mL) was added to the reaction dropwise via syringe. After warming to rt, the solvent was evaporated in vacuo. The resulting residue was redissolved in EtOAc (15 mL), and the organic layer was washed with aqueous NaHCO3 (3×10 mL) and aqueous NaCl (3×10 mL). The organic extract was dried with Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. Flash chromatography (2:1 ethyl acetate:hexanes) afforded 9 as a white solid (90 mg, 0.41 mmol) in 41% yield. mp 78.5–80.5 °C; 1H NMR (acetone-d6) δ 2.24 (s, 3H), 4.14 (s, 2H), 7.01 (d, J=5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (dtt, J=5.5, 2.0, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (dtt, J=9.8, 2.0, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.97 (d, J=5.1 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (d, J=5.5 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (acetone-d6) δ 10.04, 31.20 (dd, J=4.0, 1.9 Hz), 118.4 (d, J=32.8 Hz), 120.7 (d, J=32.6 Hz), 122.7 (d, J=4.2 Hz), 123.5 (d, J=4.2 Hz), 141.8 (d, J=5.6 Hz), 144.6 (d, J=15.9 Hz), 146.3 (d, J=15.3 Hz), 151.5 (d, J=5.0 Hz), 161.4 (d, J=96.4 Hz), 162.7 (d, J=101.8 Hz); 19F NMR (acetone-d6) δ −69.59 (J=9.1), −71.59; HRMS [C12H10N2F2] requires m/z 220.0812. Found: 220.0819. An x-ray crystal structure of 9 is reported in supporting information.

Synthesis of 10

A solution of N-lithiodihydropyridine 5 (0.05 M) at −40 °C prepared as described above was warmed to 0 °C in a water/ice bath. Stirring was continued for 15 min. The reaction was quenched with a THF/water mixture (40:1, 10.3 mL). After warming to rt, the solvent was evaporated in vacuo. The resulting residue was redissolved in EtOAc (15 mL), and the organic layer was washed with aqueous NaHCO3 (3×10 mL) and aqueous NaCl (3×10 mL). The organic extract was dried with Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. Flash chromatography (2:1 ethyl acetate:hexanes) afforded 1,2-adduct 10 as a colorless liquid (178 mg, 0.88 mmol) in 88% yield. 1H NMR (acetone-d6) δ 2.34 (s, 3H), 4.16 (s, 2H), 7.14 (dd, J=7.6, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (dtt, J=6.1, 2.0, 0.9 Hz 1H), 7.56 (d, J=7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (dtt, J=8.6, 2.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.05–8.09 (m, 1H), 8.28 (dd, J=4.91, 1.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (acetone-d6) δ18.7 (d, J=1.9 Hz), 34.8 (d, J=1.9 Hz), 122.3, 122.7 (d, J=3.2 Hz), 122.8 (d, J=3.8 Hz), 132.3, 138.5, 142.6 (d, J=5.8 Hz), 146.2 (d, J=15.6 Hz), 147.6 (d, J=1.5 Hz) 157.6, 162.9 (d, J=236.2 Hz); 19F NMR (acetone-d6) δ −70.2 (d, J=8.6); HRMS [C12H11N2F] requires m/z 202.0906. Found: 202.0906.

Synthesis of Trimer 15

A 1.6 M solution of n-butyllithium (1.25 mL, 2.0 mmol) in hexanes was added via syringe to dry THF (10.0 mL) at −40 °C under inert Ar atmosphere. Dry diisopropylamine (280 µL, 202 mg, 2.0 mmol) was added to the solution via syringe. After stirring for 5 min at −40 °C, PhCN (408 µL, 512 mg, 4.0 mmol) was added to the LDA solution. The solution became bright yellow as amidinolithium 6 formed over the course of 15 min. After stirring for 4 h, quenching with a THF/water mixture (40:1, 10.3 mL) dropwise via syringe, and warming to rt, the solvent was evaporated in vacuo. The resulting residue was redissolved in copious amounts of EtOAc (100 mL) due to limited solubility, and the organic layer was washed with aqueous NaHCO3 (3×10 mL) and aqueous NaCl (3×10 mL). The organic extract was dried with Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated to dryness. The off-white solid was recrystallized from neat ethyl acetate. Known31 trimer 15 (340 mg, 1.10 mmol) was isolated as a white solid in 83% yield. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ, 8.74–8.78 (6H, m).

Preparation of Lithiated Picoline Dimer 22

A solution of 3-picoline (21, 1.50 mL, 1.44 g, 15.5 mmol) in 3.0 mL THF was added via syringe to LDA (800 mg, 7.5 mmol) in THF (5.0 mL) and hexanes (60 mL) at −78 °C under Ar. Warming to 0 °C and stirring for 1.0 hresulted in a bright yellow precipitate. The suspension was cooled by dry ice/acetone for 1 hr, and the solvent was removed via syringe. The yellow solid was washed by THF /hexanes (1:10) and vacuumed for 3 h to afford a yellow solid (yield 87%). The resulting stable, bright yellow solid was too insoluble for spectroscopic analysis but was characterized by quenching to form 23 as described below.

Preparation of Picoline Dimer 23

An NMR tube charged with lithiated 3-dimer 22 as a yellow solid (9.6 mg, 0.05 mmol), cooled to −78 °C, and treated with THF-d8 /H2O (40:1) via syringe. The yellow solid became a colorless solution containing dihydropyridine 23 in greater than 90% spectroscopic purity: 1H NMR (THF-d8) δ 1.59 (s), 2.54 (ddm, J=13.1, 7.4 Hz, 1H), 2.74 (ddm, J=13.1, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 3.19 (m, 1H), 3.97 (ddd, J=7.7, 4.2, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 5.76 (ddd, J=4.7, 1.5, 1.4 Hz, 1H); 5.90 (ddd, J=7.7, 4.7, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (br s 1H), 7.17 (ddd, J=7.7, 4.8, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (m, 1H), 8.32 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (THF-d8) δ 18.5, 39.7, 40.8, 96.3, 123.2, 123.8, 127.5, 35.4, 137.5, 146.9, 150.5.

1,4-Adduct 5: Crossover Studies

A solution of LDA (0.275 M, 100 µL, 0.030 mmol) in neat THF was added to one side of a double-well vessel (Figure 1) under inert Ar atmosphere at −40 °C. A solution of 1-d3 (0.250 M, 100 µL, 0.025 mmol) in THF was injected into the reaction vessel and allowed to stir at −40 °C for 24 h. To the other well of the vessel was added an aliquot of LDA solution (0.275 M, 100 µL, 0.030 mmol) followed by a solution of 1-d0 (0.250 M, 100 µL, 0.025 mmol) in THF. After 1.5 h, the reaction vessel was tilted in the bath to fully mix both wells. The reaction was allowed to stir for the desired amount of time and quenched with a THF/water mixture (40:1, 500 µL). The contents of the vessel were transferred to a 1.5 mL GC vial and analyzed via GC/MS.

Figure 1.

Vessel used for double crossover experiment.

Amidinolithium 6: Crossover Studies

A solution of [6Li,15N]LDA (0.30 M, 400 µL, 0.12 mmol) in neat THF was added to an NMR tube at −78 °C under Ar atmosphere capped by two septa. To the NMR tube was added benzonitrile solution (1.56 M, 100 µL, 0.16 mmol) in THF. The reaction was allowed to stand at −78 °C for 1 hour. Once conversion to 6 was complete as indicated by 6Li NMR, a solution of [6Li]LDA (1.20 M, 100 µL, 0.12 mmol) was added and warmed to −40 °C. Crossover was allowed to occur over the course of 12 h with periodic cooling to −90 °C to acquire spectra.

Kinetics of 3-Fluoropicoline Metalation

IR spectra were recorded using an in situ IR spectrometer fitted with a 30-bounce, silicon-tipped probe. The spectra were acquired in 16 scans at a gain of 1 and a resolution of 8 cm−1. A representative reaction was carried using the reaction of LDA and PhCN emblematically as follows: The IR probe was inserted through a nylon adapter and FETFE O-ring seal into an oven-dried, cylindrical flask fitted with a magnetic stir bar and a T-joint. The T-joint was capped by a septum for injections and an argon line. Pseudo-first-order conditions were established by maintaining low concentrations of 1 (0.005 M) at high, yet adjustable, concentrations of LDA (0.10–0.75 M) and THF (3.9–12.3 M)60 with pentane as the cosolvent. It was most convenient to follow the formation of 5 (1667 cm−1) by IR spectroscopy, which displays a first-order behavior to ≥ 5 half-lives.30,61 No evidence of LDA-picoline complexation was noted. The resulting pseudo-first-order rate constants (kobsd) are independent of picoline concentration (0.004 – 0.04 M), confirming the first-order substrate dependence. Re-establishing the IR baseline and monitoring a second injection reveals no significant change in the rate constant, showing that conversion-dependent autocatalysis or autoinhibition are unimportant under these conditions. Comparisons of 1 versus 1-d3, provided kH/kD = 29 ± 1, confirming a rate-limiting proton transfer. Unusually large isotope effects have been observed for other lithiations.62 Plots of kobsd versus THF concentration and kobsd versus LDA concentration (at 4.1 M THF affords the rate law described by eq 3. Data are included in supporting information.

Kinetics of LDA-PhCN Condensation

Pseudo-first-order conditions were established by maintaining the concentration of PhCN low (0.01 M) and the concentrations of LDA (0.10–0.30 M) and THF (2.0–12.3 M)60 high (yet adjustable) with pentane as the cosolvent. The loss of PhCN (1667 cm−1) by IR spectroscopy display a first-order behavior to ≥ 5 half-lives.30,61 No evidence of LDA-PhCN complexation was noted. Plots of kobsd versus LDA concentration (at 10.0 M THF) and kobsd versus THF concentration (supporting information) afford the reaction orders indicated in eq 5.

Supplementary Material

NMR spectra, x-ray crystallographic data, and rate data (51 pages). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

The Cornell group thanks the National Science Foundation and sanofi-aventis for support.

References and Footnotes

- 1.(a) Popowycz F, Routier S, Joseph B, Merour J-Y. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:1031. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fang Y-Q, Yuen J, Lautens M. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:5152. doi: 10.1021/jo070460b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Merour J-Y, Joseph B. Current Org. Chem. 2001;5:471. [Google Scholar]; (b) Song JJ, Reeves JT, Gallou F, Tan Z, Yee N, Senanayake CH. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1120. doi: 10.1039/b607868k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hopkins CR, Collar N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:8087. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis ML, Wakefield BJ, Wardell JA. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:939. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Vorbrugenn H. Adv. Hetercycl. Chem. 1990;49:117. [Google Scholar]; (b) McGill CK, Rappa A. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 1988;44:1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Queguiner G, Marsais F, Snieckus , Epsztajn J. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 1991;52:187. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mongin F, Queguiner G. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:5897. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mongin F, Queguiner G. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:4059. [Google Scholar]; (d) Merino P. Progr Heterocycl. Chem. 1999;11:21. [Google Scholar]; (e) Clayden J. In: The Chemistry of Organolithium Compounds. Rappoport Z, Marek I, editors. Vol. 1. New York: Wiley; 2004. p. 495. [Google Scholar]; (f) Caubere P. Reviews of Heteroatom Chemistry. vol. 4. Tokyo: MYU; 1991. pp. 78–139. [Google Scholar]; (g) Caubere P. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:2317. [Google Scholar]; (h) Marsais F, Queguiner G. Tetrahedron. 1983;39:2009. [Google Scholar]; (i) Collins I. Perkin 1. 2000:2845. [Google Scholar]; (i) Schlosser M, Mongin F. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1161. doi: 10.1039/b706241a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For a review of structural studies using 19F NMR spectroscopy, see: Gakh YG, Gakh AA, Gronenborn AM. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2000;38:551. McGill CA, Nordon A, Littlejohn D. J. Process Analyt. Chem. 2001;6:36.

- 7.Scheme 2 does not represent a comprehensive profile of byproducts.

- 8.Stout DM, Meyers AI. Chem. Rev. 1982;82:223. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nanney JR, Mahaffy CAL. J. Fluorine Chem. 1994;68:181. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Treating 5 with MnO2 prior to the aqueous quench affords 9 in 50%. For a related MnO2 rearomatization, see: Godard A, Jacquelin JM, Queguiner G. J. Organomet. Chem. 1988;354:273. Eynde JJ, Delfosse F, Mayence A, Haverbeke V. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:6511.

- 11.For the 1,2-addition of an aryllithium to 1, see: DuPriest MT, Schmidt CL, Kuzmich D, Williams SB. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:2021.

-

12.Dimer 9 was also characterized by x-ray crystallography. The product of oxidative coupling (i) was also characterized as a rogue crystal by x-ray crystallography. We were unable to intentionally produce detectable i by introducing oxygen to an LDA/1 mixture.

- 13.We find fluoropyridines to be sensitive to traces of acid, including the residual HCl in chlorinated solvents.

- 14.Galiano-Roth AS, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:6772. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Collum DB. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993;26:227. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schleyer PvR, Snaith R. Adv. Inorganic. Chem. 1991;37:47. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mulvey RE. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1991;20:167. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Traces (approx 5%) of 13 (δ −77.9 ppm) are also observed.

-

17.Lithiation of an isolated sample of 9 with LDA affords new 19F resonances at δ −78.9 and −75.0 ppm that we attribute to ii. These resonances were not observed in the reaction mixture.

- 18.For a review of rate studies of LDA-mediated reactions, see: Collum DB, McNeil AJ, Ramirez A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:3002. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603038.

- 19.We define the idealized rate law as that obtained by rounding the observed reaction orders to the nearest rational order.

- 20.Ma Y, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14818. doi: 10.1021/ja074554e. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.For leading references and discussion of high-coordinate lithium amides, see ref 20.

- 22.(a) van Eikema Hommes NJR, Schleyer PvR. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1992;31:755. [Google Scholar]; (b) Stalke D, Klingebiel U, Sheldrick GM. Chem. Ber. 1988;121:1457. [Google Scholar]; (c) Armstrong DR, Khandelwal AH, Kerr LC, Peasey S, Raithby PR, Shields GP, Snaith R, Wright DS. Chem. Commun. 1998:1011. [Google Scholar]; (d) Plenio H, Diodone R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:356. [Google Scholar]; (e) Henderson KW, Dorigo AE, Liu Q-Y, Williard PG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:11855. [Google Scholar]; (f) Chadwick ST, Rennels RA, Rutherford JL, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:8640. [Google Scholar]; (g) Chadwick ST, Ramirez A, Gupta L, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2259. doi: 10.1021/ja068057u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Williard PG, Liu Q-Y. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:1596. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carpenter BK. Determination of Organic Reaction Mechanisms. New York: Wiley; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.A deviation from statistical stems from difficulty in obtaining precisely equal proportions of 5-d0 and 5-d5 due to the especially large kinetic isotope effect on the metalation.

- 25.It has been suggested that the n-BuLi adduct of pyridine can reduce pyridine by extruding lithium hydride: Clegg W, Dunbar L, Horsburgh L, Mulvey RE. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1996;35:753.

- 26.(a) The fit to [A] = [A0]exp(kobsd)t showed some discrepancies (supporting information), yet a fit to a non-linear Noyes equation (ref 26b) to obtain the order by best-fit methods revealed an order of 1.0. Briggs TF, Winemiller MD, Collum DB, Parsons RL, Jr, Davulcu AK, Harris GD, Fortunak JD, Confalone PN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:6291. doi: 10.1021/ja0305813.

- 27.kobsd for the decay of 5 shows a minor (50%) rise with a three-fold decrease in THF concentration.

- 28.The crossover described in Scheme 3 occurs at substantially lower temperatures than the rearrangement to provide 10. As expected, analogous crossover is observed in 10.

- 29.We have never observed [6Li]LiF by NMR spectroscopy. This may derive from a very low solubility.

- 30.Rein AJ, Donahue SM, Pavlosky MA. Curr. Opin. Drug Discovery Dev. 2000;3:734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.(a) Compagnon PLouis, Gasquez F, Kimny T. Bull. Soc. Chim. Belges. 1986;95:57. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen X, Bai S-D, Wang L, Liu D-S. Heterocycles. 2005;65:1425. [Google Scholar]

- 32.(a) Davies RP, Raithby PR, Shields GP, Snaith R, Wheatley AEH. Organometallics. 1997;16:2223. [Google Scholar]; (b) Armstrong DR, Clegg W, MacGregor M, Mulvey RE, O'Neil PA. J. Chem. Soc, Chem. Commun. 1993:608. [Google Scholar]; (c) Armstrong DR, Henderson KW, MacGregor M, Mulvey RE, Ross MJ, Clegg W, O'Neil PA. J. Organomet. Chem. 1995;486:79. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crystal structures of amidinolithiums: Aharonovich S, Kapon M, Botoshanski M, Eisen MS. Organometallics. 2008;27:1869.

- 34.For calculated open dimer-based additions of methyllithium to nitriles, see: Uchiyama M, Matsumoto Y, Usui S, Hashimoto Y, Morokuma K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:926. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602664.

- 35.Romesberg FE, Gilchrist JH, Harrison AT, Fuller DJ, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:5751. [Google Scholar]

- 36.The nuclear spins of 6Li and 15N are 1 and 1/2, respectively.

- 37.(a) Armstrong DR, Barr D, Snaith R, Clegg W, Mulvey RE, Wade K, Reed D. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1987:1071. [Google Scholar]; (b) Barr D, Snaith R, Mulvey RE, Wade K, Reed D. Mag. Reson. Chem. 1986;24:713. [Google Scholar]; (c) Reed D, Barr D, Mulvey RE, Snaith R. J Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1986:557. [Google Scholar]; (d) Barr B, Clegg W, Mulvey RE, Snaith R, Wade K. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1986:295. [Google Scholar]

- 38.(a) Turner JA. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:3401. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hands D, Bishop B, Cameron M, Edwards JS, Cottrell IF, Wright SHB. Synthesis. 1996:877. [Google Scholar]; (c) Houlihan WJ, Parrino VA, Uike Y. J. Org. Chem. 1981;46:4511. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith K, El-Hiti GA, Hamilton A. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1998;24:4041. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dissolving the yellow solid with added N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA) resulted in very complex mixtures. We suspect that TMEDA mediates reversal of the 1,4-addition, allowing other reactions to occur.

- 41.Tagawa Y, Hama K, Goto Y. Heterocycles. 1992;34:1605. [Google Scholar]

- 42.(a) Zoeckler MT, Carpenter BK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:7661. [Google Scholar]; (b) Carpenter BK. Tetrahedron. 1978;34:1877. [Google Scholar]

- 43.By contrast, the relatively weak acid hexamethyldisilazane converts dimer 5 to picoline 1.

- 41. Knauss E, Ondrus T, Giam C. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1976;13:789. Thomas EW. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:2184. Giam CA, Stout JL. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1970:478. Ludt RE, Crowther GP, Hauser CR. J. Org. Chem. 1970;35:1288. Francis RF, Crews CD, Scott BS. J. Org. Chem. 1978;43:3227. Marsais F, Granger P, Queguiner G. J. Org. Chem. 1981;46:4494. Gronowitz S, Roe J. Acta Chem. Scand. 1965;19:1741. Marsais F, Le Nard G, Queguiner G. Synthesis. 1982:235. (i) Also, see ref 9.

- 45.(a) Abramovitch RA, Poulton GA. J. Chem. Soc. (B) 1969:901. [Google Scholar]; (b) Abramovitch RA, Giam C-S, Poulton GA. J. Chem. Soc. (C) 1970:128. [Google Scholar]; (c) Abramovitch RA, Giam C-S. Can. J. Chem. 1964;42:1627. [Google Scholar]; (d) Abramovitch RA, Giam C-S. Can. J. Chem. 1963;41:3127. [Google Scholar]; (e) Clegg W, Dunbar L, Horsburgh L, Mulvey RE. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1996;35:753. [Google Scholar]

- 46.(a) Abarca B, Hayles DJ, Jones G, Sliskovic DR. J. Chem. Res., Synop. 1983:181. [Google Scholar]; (b) Postigo A, Rossi RA. Org. Lett. 2001;3:1197. doi: 10.1021/ol015666s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Clayden J, Turnbull R, Pinto I. Org. Lett. 2004;6:609. doi: 10.1021/ol0364071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Overberger CG, Heron LP. J.Org. Chem. 1962;27:2423. [Google Scholar]; (e) Giam CS, Knaus EE. Tetrahedron Lett. 1971:4961. [Google Scholar]; (f) Gros P, Fort Y. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin 1. 1998:3515. [Google Scholar]; (g) Zhang L, Tan Z. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:3025. [Google Scholar]; (h) Kauffmann T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1979;18:1. and references cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mixed condensation of heteroaryllithiums with heteroarenes: Gros P, Fort Y. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin 1. 1998:3515. ; Kauffmann T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1979;18:1. and references cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- 48.(a) Gros P, Fort Y, Caubere P. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin I Trans. 1997:3597. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gros P, Fort Y, Caubere P. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin I Trans. 1997:3071. [Google Scholar]; (c) Gros P, Fort Y. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:2028. doi: 10.1021/jo026706o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kaufmann T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1979;18:1. [Google Scholar]; (e) Martens RJ, Den Hertzog HJ, van Ammers M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1964:3207. [Google Scholar]; (f) Marais RJ, Breant P, Ginguene A, Queguiner G. J. Organomet. Chem. 1981;216:139. [Google Scholar]; (g) Newkome GR, Hager DC. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:599. [Google Scholar]; (h) Clarke AJ, McNamara S, Meth-Cohn O. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974:2373. [Google Scholar]; (i) Wiessenfels M, Ulrici B. Z. Chem. 1978;18:382. [Google Scholar]; (j) Cottet F, Schlosser M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004:3793. [Google Scholar]

- 49.An alternative radical mechanism for the dimerization of pyridine has been proposed (ref 48g).

- 50.(a) Kress KJ. J. Org. Chem. 1979;44:2081. [Google Scholar]; (b) Plé N, Turck A, Couture K, Queguiner G. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:3781. [Google Scholar]

- 51.(a) Kaufmann T, Greving B, König J, Mitschker A, Wotermann A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1975;14:713. [Google Scholar]; (b) Seggio A, Chevalier F, Vaultier M, Mongin F. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:6602. doi: 10.1021/jo0708341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alkylations of 3-picoline proceed in high yield. See, for example: Gedig T, Dettner K, Seifert K. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:2670. Baldwinz JE, Melman A, Lee V, Firkin CR, Whitehead RC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:8559. Romeril SP, Lee V, Baldwin JE, Claridge TDW. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:1127. Perez-Balado C, Nebbioso A, Rodriguez-Grana P, Minichiello A, Miceli M, Altucci L, de Lera AR. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:2497. doi: 10.1021/jm070028m. Davies-Coleman MT, Faulkner JD, Dubowchik GM, Roth GP, Polson C, Fairchild C. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:5925.

- 53.(a) Kaiser EM, Petty JD. Synthesis. 1975:705. [Google Scholar]; (b) Salas M, Joule JA. J. Chem. Res., Synop. 1990:98. [Google Scholar]; (c) Raynolds S, Levine R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960;82:472. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fraser RR, Mansour TS, Savard S. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:3232. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mamane V, Aubert E, Fort Y. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:7294. doi: 10.1021/jo071209z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.There are discussions of reversible radical-based dimerizations of heteroaromatics: Shimoishimi H, Tero-Kubota S, Ikegami Y. Bull. Chem. Soc. Japan. 1985;58:553.

- 57.(a) http://www.drugtopics.com/Top+200+Drugs.; (b) http://www.chem.cornell.edu/jn96/outreach.html.

- 58.(a) Kottke T, Stalke D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1993;32:580. [Google Scholar]; (b) Rennels RA, Maliakal AJ, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:421. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kofron WG, Baclawski LM. J. Org. Chem. 1976;41:1879. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Precipitation occurs below 3.9 M THF.

-

61.Following product formation ([P]) and fitting the data to

affords the pseudo-first-order rate constant, kobsd. The quality of the fit, however,is not diagnostic of first-order behavior because this function also fits second-order data reasonably well. The problem stems from determining the concentration of P at t = ∞ ([P∞]) as an adjustable parameter. The first order dependence was confirmed by (1) monitoring the the value of kobsd at different initial concentrations of starting material, and (2) monitoring the loss of picoline 1 (δ −70.2 ppm) by 19F NMR spectroscopy and showing adequate fit to - 62.(a) Singh KJ, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13753. doi: 10.1021/ja064655x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rennels RA, Rutherford JL, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:8640. and references cited therein. [Google Scholar]; (c) Anderson DR, Faibish NC, Beak P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:7553. [Google Scholar]; (d) Meyers AI, Mihelich ED. J. Org. Chem. 1975;40:3158. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

NMR spectra, x-ray crystallographic data, and rate data (51 pages). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.