Abstract

Although mast cell functions classically relate to allergic responses1–3, recent studies indicate that these cells contribute to other common diseases such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis, aortic aneurysm, and cancer4–8. This study presents evidence that mast cells contribute importantly to diet-induced obesity and diabetes. White adipose tissues (WAT) from obese humans and mice contain more mast cells than WAT from their lean counterparts. Genetically determined mast cell deficiency and pharmacological stabilization of mast cells in mice reduce body weight gain and levels of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and proteases in serum and WAT, in concert with improved glucose homeostasis and energy expenditure. Mechanistic studies reveal that mast cells contribute to WAT and muscle angiogenesis and associated cell apoptosis and cathepsin activity. Adoptive transfer of cytokine-deficient mast cells established that these cells contribute to mice adipose tissue cysteine protease cathepsin expression, apoptosis, and angiogenesis, thereby promoting diet-induced obesity and glucose intolerance by production of IL6 and IFN-γ. Mast cell stabilizing agents in clinical use reduced obesity and diabetes in mice, suggesting the potential of developing novel therapies for these common human metabolic disorders.

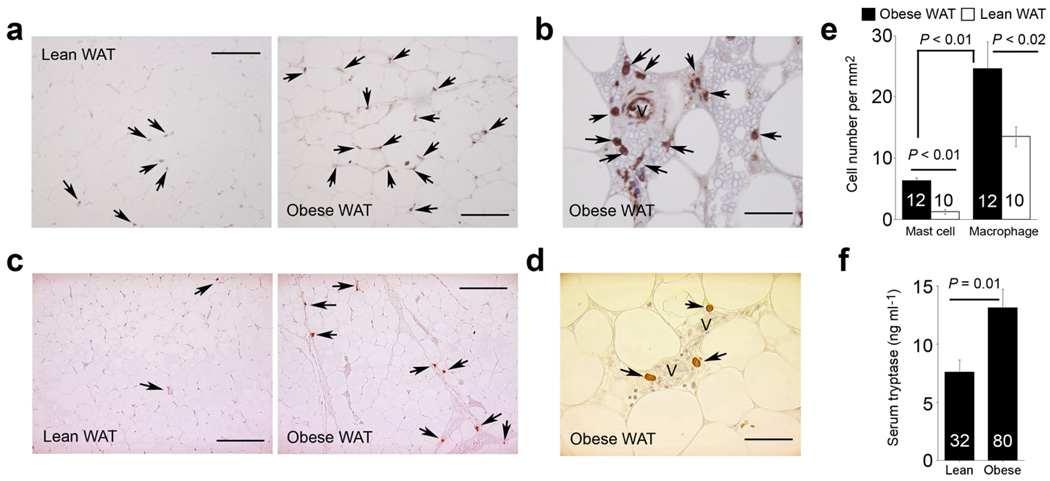

In addition to adipocytes, WAT in obese subjects contain macrophages and lymphocytes9–11. WAT from obese subjects contained more macrophages than found in lean donors as expected (Fig. 1a) with some of these macrophages bordered microvessels (Fig. 1b). These inflammatory cells furnish cytokines, growth factors, chemokines, and proteases in WAT11,12. However, the role of these cells in the pathogenesis of obesity and associated metabolic complications remains uncertain. Other heretofore under-recognized cells may also contribute critically. Staining WAT sections with a mast cell tryptase monoclonal antibody revealed increased numbers of mast cells in WAT from obese subjects compared with those from lean donors. Like macrophages, many of these mast cells adjoin microvessels (Fig. 1c, d), although WAT had significantly fewer mast cells than macrophages (Fig. 1e). Increased mast cell content of WAT from obese subjects suggests increased systemic mast cell protease levels. Obese subjects (body mass index: BMI ≥ 32 kg per mm2) had significantly higher serum tryptase levels than lean individuals (BMI < 26 kg per mm2) before (P = 0.01) and after adjusting for gender (P = 0.01, multivariate analysis) (Fig. 1f). These observations suggest an association of mast cells and obesity.

Figure 1.

Macrophages and mast cells in human WAT. a. Human HAM56 immunostaining of WAT from obese and lean subjects. b. HAM56+ macrophages near the microvessels in obese WAT. c. Human mast cell tryptase immunostaining of WAT from obese and lean subjects. d. Tryptase+ mast cells close to microvessels in obese WAT. e. Many more macrophages than mast cells were detected in WAT, and both cell types were significantly higher in obese WAT than in lean WAT (Mann-Whitney test). Mast cell number per mm2 in obese WAT vs. lean WAT increased independently of gender (P > 0.05) or diabetic status (P > 0.05) (Mann-Whitney test) and did not correlate with age (P > 0.05, Spearman’s correlation test). Arrows indicate HAM56+ macrophages or tryptase+ mast cells; V: microvessel; scale bars: 100 µm in a and c and 25 µm in b and d. f. ELISA analysis revealed significantly higher levels of serum mast cell tryptase in obese subjects than in lean donors (P = 0.01, unpaired t-test). This significance remained after adjusting for gender (P = 0.01), but disappeared after adjusting for fasting glucose, insulin, and homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) (P > 0.05, multivariate analysis). This suggests that the association between serum tryptase and obesity depends on blood glucose homeostasis, consistent with significant positive correlations between serum tryptase and fasting glycemia (R = 0.19, P < 0.05), insulin (R = 0.21, P < 0.04), and HOMA (R = 0.24, P < 0.02) (non-parametric Spearman’s correlation). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

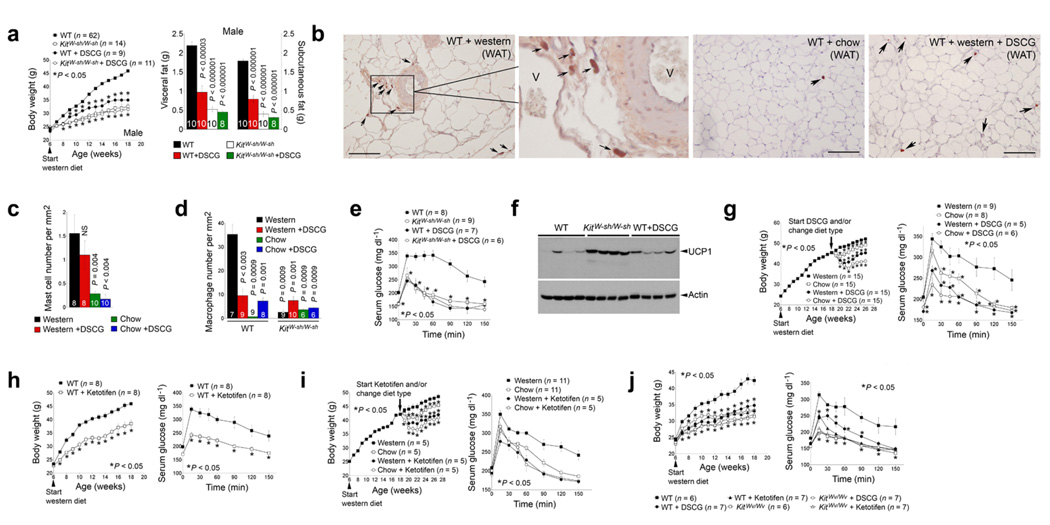

To assess direct participation of mast cells in obesity, we studied diet-induced obesity in mast cell-deficient Kit W-sh/W-sh mice, which lack mature mast cells due to an inversion mutation of the c-Kit promoter region13. Six-week-old male (Fig. 2a) and female (Supplementary Fig. 1a) KitW-sh/W-sh mice fed a Western diet for 12 weeks gained significantly less body weight than wild-type (WT) congenic controls. Similarly, WT mice receiving a daily intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of the mast cell stabilizer disodium cromoglycate (DSCG)14–16 also had attenuated body weight gain. DSCG treatment did not further affect the body weight of the KitW-sh/W-sh mice, suggesting it acted through mast cells. Consistent with reduced body weight, both male and female KitW-sh/W-sh mice or those receiving DSCG had significantly less total subcutaneous and visceral fat than untreated WT controls (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1a). Earlier studies revealed normal numbers and activities of monocytes or macrophages and neutrophils in WT and KitW-sh/W-sh mice 6,7,17. Using T or B lymphocytes from KitW-sh/W-sh mice we detected no significant activity differences in a mixed lymphocyte reaction assay from those of WT mice (data not shown). While Western diet-fed WT mice livers were steatotic with abundant c-Kit CD117+ mast cells, those from KitW-sh/W-sh or WT mice treated with DSCG under the same dietary conditions did not contain mast cells and had similar histologic appearance to chow diet-fed WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Histological analysis of the intestine, colon, stomach, and pancreas also did not reveal obvious phenotypic differences between chow diet-fed WT mice and any diet-fed KitW-sh/W-sh or DSCG-treated WT mice (data not shown). Body composition analysis revealed reduced fat mass but increased lean mass in KitW-sh/W-sh mice or those that received DSCG after 12 weeks of a Western diet (Supplementary Fig. 1c). These data provide no evidence that reduced obesity in KitW-sh/W-sh or DSCG-treated mice did not stem from the loss of mast cell function or resulted from a confounding general health issue.

Figure 2.

Mast cell deficiency and stabilization reduced diet-induced obesity and diabetes in male mice. a. Body weight gain and visceral and subcutaneous fat weight in WT and KitW-sh/W-sh mice (C57BL/6). b–c. CD117 immunostaining and CD117+ mast cells in WAT from WT mice with different treatments. Arrows indicate CD117+ mast cells; V: WAT microvessels, scale bars: 100 µm. d. Mac-2+ macrophage numbers in WAT from different groups of mice as indicated. e. Glucose tolerance assay in WT and KitW-sh/W-sh mice that consumed a Western diet for 12 weeks with and without DSCG treatments. f. Immunoblot analysis for UCP1 (32 kDa) in brown fat from WT, KitW-sh/W-sh and DSCG-treated WT mice that consumed a Western diet for 12 weeks. Actin (42 kDa) immunoblot was used for protein loading control. g. DSCG reduced pre-formed obesity and diabetes. Arrow indicates where pre-formed obese mice were divided into four groups. Mouse glucose tolerance assays for all four groups of mice after the treatments are shown to the right. h. Body weight gain and glucose tolerance assay in WT mice treated with or without ketotifen. i. Ketotifen reduced pre-formed obesity and diabetes in a similar protocol as in g. j. Reduced body weight and improved glucose tolerance in KitWv/Wv and WT mice (WBB6F1/J) treated with DSCG or ketotifen. The number of mice for each group is indicated in the bars or the parentheses. *Each time point was compared to Western diet-fed WT mice. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant; Mann-Whitney test. NS: no significant difference.

Similar to human WAT (Fig. 1c–e), immunostaining using a CD117 monoclonal antibody detected significantly more mast cells in WAT from Western diet-induced obese mice than those from chow diet-fed lean mice, with many of these mast cells located near microvessels (Fig. 2b, c). Notably, DSCG treatment did not significantly reduce WAT mast cell content in Western diet-fed WT mice (Fig. 2b, c), but these mice responded similarly to KitW-sh/W-sh mice in body weight gain, suggesting that DSCG inactivated mast cells but did not affect their recruitment to the WAT. In contrast, immunostaining using a Mac-2 monoclonal antibody detected significantly fewer macrophages in KitW-sh/W-sh and DSCG-treated mice than untreated Western diet-fed WT mice (Fig. 2d). High mast cell numbers but low macrophage numbers in WAT from DSCG-treated Western diet-fed WT mice suggest that mast cells appear in WAT before macrophages, a hypothesis that merits further examination.

Along with reduced body weight, male and female KitW-sh/W-sh mice or those receiving DSCG also had significantly lower levels of serum leptin than WT controls (Supplementary Fig. 1d). These mice also demonstrated greater glucose tolerance and more sensitivity to insulin than did Western diet-fed WT control mice. Glucose tolerance assay (Fig. 4e) and insulin sensitivity assay (Supplementary Fig. 1e) in Western diet-fed mice revealed significantly improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity of KitW-sh/W-sh mice or WT mice receiving DSCG. These mice also had lower serum insulin levels than the WT control mice (Supplementary Fig. 1f). To understand the mechanisms of these salutary effects of mast cell deficiency or inactivation, we performed energy expenditure assays and measured brown fat uncoupled protein-1 (UCP1). Measurement of food and water intake, fecal and urine production, and O2 consumption and CO2 production showed that KitW-sh/W-sh mice and DSCG-treated WT mice had an increased resting metabolic rate, illustrated by significantly greater O2 consumption and CO2 production than untreated WT mice (Supplementary Table 1). These mice had higher brown fat UCP1 expression, a marker of energy expenditure18,19, than WT control mice (Fig. 2f).

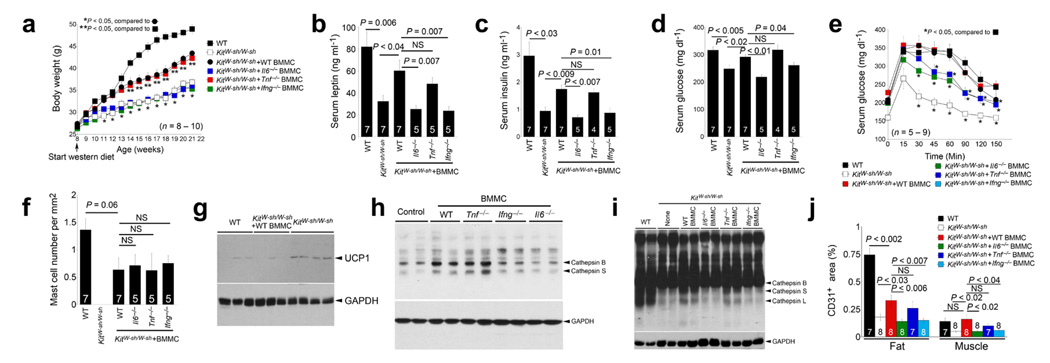

Figure 4.

Mast cell reconstitution in KitW-sh/W-sh mice. Reconstitution of KitW-sh/W-sh mice with BMMC from WT and Tnf–/– mice, but not from Ifng–/–and Il6–/– mice, partially restored body weight gain (a), serum leptin (b), serum insulin (c), serum glucose (d), and glucose tolerance (e). f. CD117+ mast cell numbers in WAT from WT, KitW-sh/W-sh and different reconstituted mice. g. Immunoblot analysis for UCP1 (32 kDa) in brown fat from WT, KitW-sh/W-sh and KitW-sh/W-sh mice received WT BMMC followed by 13 weeks of Western diet consumption. h. Cathepsin active site JPM labeling of cell lysate from 3T3-L1 cells treated with different BMMC. Active CatB and CatS are indicated. i. WAT extract JPM labeling to detect active cathepsins as indicated by arrowheads. Immunoblot analysis for GAPDH (37 kDa) was used for protein loading control. j. Quantification of CD31-positive areas in WAT and muscle from different groups of mice. All data in a–f and j are mean ± SEM. The number of mice for each group is indicated in the bars or in the parentheses. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, non-parametric Mann-Whitney test.

To test whether DSCG also reverses pre-formed obesity and diabetes, we fed WT mice a Western diet for 12 weeks to produce obesity and diabetes, and grouped these obese and diabetic mice into four treatment groups: I, continued on a Western diet; II, switched to a chow diet; III, continued on a Western diet but with a daily i.p. injection of DSCG; IV, switched to a chow diet and treated with DSCG. Although a change in diet (group II) also reduced body weight (8%) and improved glucose tolerance as expected, a combination of diet change and DSCG administration (group IV) yielded the greatest improvement of both body weight and glucose tolerance. Eight weeks after DSCG treatment, the body weight of group III mice decreased by 12%, but that of group IV mice decreased by 19% and stabilized around 40–41 grams, with these mice demonstrating the highest glucose tolerance among the four groups (Fig. 2g), suggesting the possibility of managing obesity and diabetes by stabilizing mast cells. Use of a second mast cell stabilizer, ketotifen, confirmed this hypothesis20,21. Like DSCG, daily i.p. injection of ketotifen reduced diet-induced body weight gain and enhanced glucose tolerance (Fig. 2h). As we anticipated, ketotifen also improved pre-formed obesity and diabetes in mice that had consumed 12 weeks of a Western diet (Fig. 2i). To affirm that the phenotypes we observed from the KitW-sh/W-sh mice or those receiving DSCG or ketotifen stemmed from the loss of mast cell functions, we used additional mast cell-deficient KitWv/Wv mice22. While WT mice (WBB6F1/J background) continued gaining body weight and developed glucose intolerance under a Western diet, KitWv/Wv mice and those receiving DSCG or ketotifen demonstrated reduced body weight gain and improved glucose tolerance (Fig. 2j). These observations provided further support for direct participation of mast cells in both obesity and diabetes.

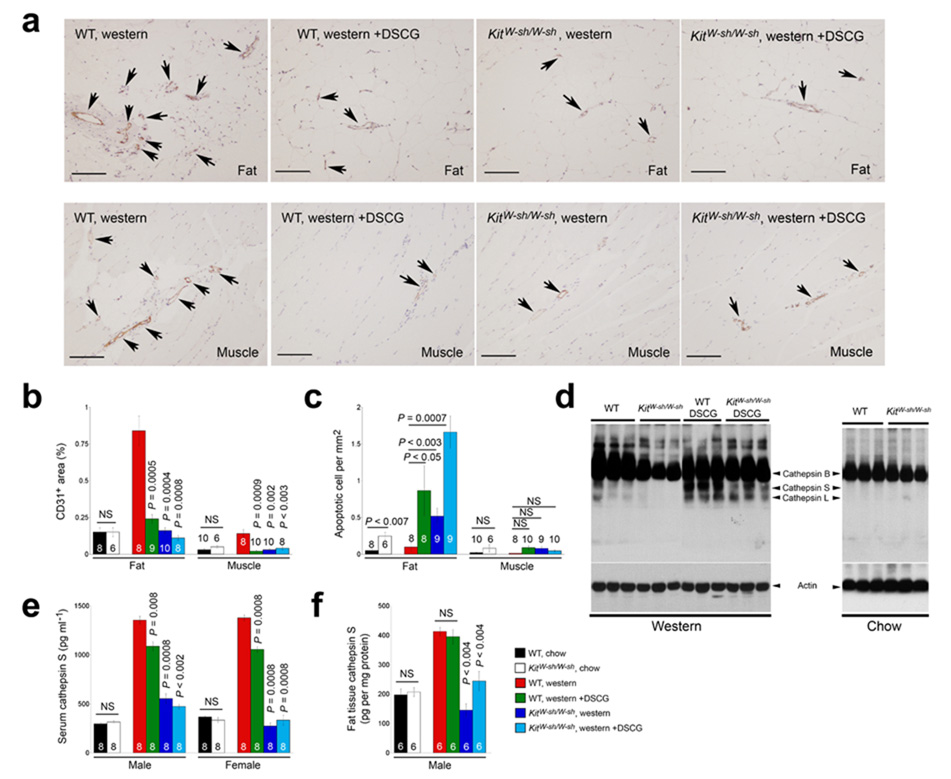

The development of obesity involves extracellular matrix remodeling and angiogenesis23. Inhibition of angiogenesis blocks adipose tissue development in mice24. Besides supplying the WAT with nutrients, microvessels provide a path for leukocyte infiltration followed by adipokine release25,26. The appearance of macrophages and mast cells next to the microvessels in WAT (Fig. 1b, d) supported this hypothesis. WAT and muscle tissue from obese WT mice showed substantial endothelial cell CD31 immunostaining. In contrast, Western diet-fed KitW-sh/W-sh mice or those receiving DSCG had CD31+ areas similar to those from chow diet-fed lean mice (Fig. 3a, b). Reduced angiogenesis should limit nutrient supply, impairing cell viability24,27. TUNEL staining demonstrated increased numbers of apoptotic cells in WAT from KitW-sh/W-sh mice or those receiving DSCG compared with WT controls (Fig. 3c). Reduced angiogenesis may also impair leukocyte infiltration (Fig. 2d) and therefore reduce WAT production of inflammatory mediators28. Consistent with this notion, KitW-sh/W-sh mice or those receiving DSCG had lower levels of IL6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, MCP-1, matrix metalloprotease-9 (MMP-9), and cathepsin S (CatS) in serum and WAT, although some adipokines (e.g., adiponectin and CatL) did not change significantly (Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 3.

Mast cell functions in angiogenesis, apoptosis, and protease expression. a. CD31 immunostaining of WAT and muscle from WT and KitW-sh/W-sh mice that consumed a Western diet for 12 weeks with or without receiving DSCG. Arrows indicate CD31+ microvessels in the WAT or muscle. Scale bars: 100 µm. b. Quantification (mean ± SEM) of CD31-positive areas in WAT and muscle. c. Quantification (mean ± SEM) of apoptotic cells in WAT and muscle. d. Cysteine protease cathepsin active site JPM labeling using WAT extracts from different groups of mice that consumed 12 weeks of a Western or chow diet. Arrowheads indicate active cathepsins. Actin immunoblot assured equal protein loading. e. Serum cathepsin S ELISA from different groups of mice. f. WAT extract cathepsin S ELISA from different groups of mice. In b, c, e, and fP < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. The number of mice in each group is indicated in each bar. NS: no significant differences.

Extracellular matrix proteolysis contributes to angiogenesis by releasing pro-angiogenic peptides29. We have previously shown that CatS plays a critical role in angiogenesis by degrading anti-angiogenic peptides and generating pro-angiogenic lamin-5 fragment γ230. Reduced angiogenesis in KitW-sh/W-sh and DSCG-treated mice accompanied low CatS levels in WAT and serum. After incubating WAT protein extracts with [125I]-JPM, which labeled selectively active cathepsins31, we found reduced active CatB, CatS, and CatL in KitW-sh/W-sh mice (Fig. 3d). Notably, WAT from DSCG-treated mice had levels of active cathepsins similar to WT controls, consistent with the observation of high numbers of mast cells in these tissues (Fig. 2c and Fig. 3d). CatS ELISA allowed us to quantify local and systemic levels among different mice. Similar to the observations from the JPM labeling experiment, both male and female KitW-sh/W-sh mice exhibited lower serum and WAT CatS levels than the WT controls (Fig. 3e). In contrast, DSCG treatment reduced significantly the CatS levels in serum but not in WAT extracts (Fig. 3f), suggesting that DSCG effectively stabilized mast cells in vivo.

To substantiate the hypothesis that improved metabolic disorders in KitW-sh/W-sh mice resulted from the loss of mast cells, rather than a generalized illness, we reconstituted KitW-sh/W-sh mice with bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMC) prepared in vitro from WT mice and mice lacking the three common mast cell cytokines IL6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, known stimulators of vascular cell cathepsin activity6,7. After 13 weeks on a Western diet, mice reconstituted with WT and Tnf−/− BMMC but not Il6−/− and Ifng−/− BMMC gained significantly more body weight than non-reconstituted mice, although they remained leaner than WT controls (Fig. 4a). Consistent with the body weight differences, those receiving WT and Tnf−/− BMMC had significantly higher serum leptin, insulin, and glucose levels than non-reconstituted mice or those receiving Il6−/− and Ifng−/− BMMC (Fig. 4b–d). KitW-sh/W-sh mice receiving Il6−/− and Ifng−/− BMMC but not WT or Tnf−/− BMMC also demonstrated improved glucose tolerance (Fig. 4e), suggesting that mast cell-derived IL6 and IFN-γ contribute to these metabolic derangements. Although we found smaller WAT adipocytes from KitW-sh/W-sh mice than WT controls, WAT adipocyte size did not vary significantly between different BMMC-reconstituted mice (data not shown). Notably, WAT from different BMMC-reconstituted KitW-sh/W-sh mice had similar numbers of mast cells between the groups but fewer than those in WT mice (Fig. 4f), which could explain the incomplete restoration of body weight gain and serum levels of leptin, insulin, and glucose (Fig. 4a–d). Along with increased body weight gain, reconstitution of WT BMMC also reduced brown fat UCP1 levels in KitW-sh/W-sh mice (Fig. 4g), affirming an important role of mast cells in energy expenditure. As discussed (Fig. 3), mast cells may contribute to obesity by stimulating WAT protease expression, thereby promoting microvessel growth. Body weight recovery in KitW-sh/W-sh mice after engraftment of WT BMMC and Tnf−/− BMMC but not Il6−/− or Ifng−/− BMMC suggests a role for mast cell-derived IL6 and IFN-γ in WAT protease expression and associated angiogenesis. To test this hypothesis, we incubated 3T3-L1 cells with degranulated BMMC extract (Fig. 4h) or live BMMC and demonstrated that both WT and Tnf−/− BMMC but not Il6−/− or Ifng−/− BMMC increased adipocyte cathepsin activities in a JPM-labeling assay. Indeed, reconstitution of WT and Tnf−/− BMMC but not Il6−/− or Ifng−/− BMMC in KitW-sh/W-sh mice increased WAT cathepsin activities (Fig. 4i). Consistent with our hypothesis, both WAT and muscle from KitW-sh/W-sh mice receiving WT and Tnf−/− BMMC but not Il6−/− or Ifng−/− BMMC had partially preserved CD31+ areas (Fig. 4j). Although other mechanisms might pertain, mast cell-mediated protease expression and associated angiogenesis may favor WAT growth.

This study establishes a novel role of mast cells in murine obesity and diabetes and suggests potential new therapies for these common human metabolic diseases using mast cell stabilizers.

Methods

Mice

Wild-type (C57BL/6 and WBB6F1/J), Il6−/− (C57BL/6, N11), Ifng−/−(C57BL/6, N10), and KitW-sh/W-sh (WBB6F1/J) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories. Congenic Tnf−/− (C56BL/6, N10) and KitWv/Wv (C57BL/6, N10) mice were generated as described6,32. Harvard Medical School Standing Committee on Animals approved all animal protocols. To induce obesity, we fed six-week-old mice (females and males) a Western diet (Research Diet, New Brunswick, NJ) for 12–13 weeks. Body weight was monitored weekly. By the end of each course of Western diet consumption, we performed glucose tolerance, insulin tolerance, energy expenditure assays, and body lean and fat mass determination as described33,34. Mouse blood samples were collected for serum adipokine measurement. Subcutaneous, visceral, and brown fat and skeletal muscle were harvested for protein extraction and paraffin section preparation. Tissue protein extracts were used for ELISA, immunoblot analysis, and cathepsin active site JPM labeling. For immunoblot, 30 µg of proteins were used to detect UCP1 (1:3000, Abcam), actin (1:500, Abcam), or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, 1:1000, Santa Cruz). Cathepsin active site labeling was performed as described31,33. The liver and gastrointestinal tract were harvested for histological analysis.

Patient selection

This study enrolled 80 obese subjects prospectively recruited between 2003 and 2007 at the Department of Nutrition of Hôtel-Dieu Hospital, Paris, France. Detailed clinical and biological parameters are listed in Supplementary Table 3. These subjects were candidates for either a dietary intervention or gastric surgery in a clinical investigation program. Those with evidence of inflammatory or infectious diseases, cancer, alcohol abuse, or kidney disease were excluded. At the time of gastric surgery, we obtained subcutaneous adipose tissue from the periumbilical area in a subset of the obese subjects (n = 12, Supplementary Table 4). Healthy, non-obese, age-matched (P = 0.11) individuals (n = 32) living in the same geographic area were recruited as controls (Supplementary Table 3). In ten lean controls (Supplementary Table 4), we obtained subcutaneous adipose tissue in the periumbilical area by needle biopsy. Serum insulin concentrations were determined with an IRMA kit (CisBio International, Gif-sur-Yvette, France). Insulin sensitivity was evaluated by the quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) =1/ [log fasting insulin (µM) + log fasting glycemia (mg dl−1)]. All tissue samples were processed under the same conditions. The Ethics Committees of the Hôtel-Dieu Hospital approved the clinical investigations, and all subjects gave written informed consent.

Immunohistology

Antibodies to human HAM56 (1:100, Dako), human tryptase (1:100, Dako), mouse Mac-2 (1:25,000, Cedarlane), mouse CD117 (1:10, eBiosciences), and mouse CD31 (1:400, Pharmingen) immunostained for macrophages, mast cells, and microvessels on WAT, muscle, and liver paraffin sections. Researchers blinded to the origin of tissue counted the total human HAM56+ macrophages, human tryptase+ and mouse CD117+ mast cells on each section, and data were presented as cell numbers per mm2. CD31+ areas in WAT and muscle were determined using Image-Pro Plus software as described30,35. Hematoxylin and eosin staining assisted histological assessment of the gastrointestinal tract.

ELISA

Frozen mouse WAT was pulverized and lysed in a RIPA buffer (Pierce). Both WAT and serum samples were subjected to ELISA analysis for IL6 (BD Biosciences), TNF-α, IFN-γ, MCP-1 (PeproTech), adiponectin, MMP-9, CatS (R&D Systems), and CatL (Bender MedSystems, Burlingame, CA) according to manufacturers’ instructions.

To measure human serum tryptase levels, a 96-well plate was pre-coated with a human tryptase polyclonal antibody (1:1000, Calbiochem). Diluted human serum samples (1:2) along with recombinant human tryptase as standard were added to the antibody-coated plate. After two h incubation at room temperature, the plate was washed and incubated for 1 hour with a human tryptase monoclonal antibody (1:2000, AbD Serotec). HRP-conjugated antibody to mouse lgG (1:1000, Thermo Scientific) was used as detecting antibody.

Cell Culture

BMMC were prepared and reconstitution experiments performed into six-week-old male KitW-sh/W-sh mice as we reported previously6,7. Two weeks after BMMC reconstitution, mice consumed a Western diet. Mouse body weight was recorded weekly, and glucose tolerance assay was performed before harvesting the WAT.

To assess a role of mast cells in 3T3-L1 cell cathepsin expression, we added either live BMMC (2,000,000 cells per well for six-well plate) or their degranulated protein extract (equivalent to the live cell numbers) into 100% confluent 3T3-L1 cells. Co-cultures were maintained for seven–nine days, and culture media with live BMMC or BMMC protein extracts were replaced every two days. 3T3-L1 cells were then used for cathepsin active site labeling as described31.

Statistics

All data from mice are expressed as mean ± SEM, and statistical significance was determined using a non-parametric Mann-Whitney test due to our small data size and abnormal data distribution. Human serum tryptase ELISA data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Student’s t test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Chi-square test for non-continuous values were used for comparisons between groups. Standard least squares were performed for multivariate analysis. P< 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. S. Rizkalla and C. Poitou (Inserm and Pitié-Salpêtriére Hospital), who contributed to the clinical investigation program. We also thank Drs. B. Spiegelman and R. K. Gupta (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School) for their help with the 3T3-L1 culture. This study was supported partially by the Established Investigator Award from the American Heart Association (0840118N) (to G-PS) and by National Institutes of Health grants HL60942, HL67283, HL81090, HL88547 (G-PS), HL34636 (PL), DK57521, and DK56116 (BBK). The clinical work was supported by the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique, Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris (AOR 02076), a grant from ANR (French National Agency of Research: RIOMA program N°ANR05-PCOD-030-02), and by the Commission of the European Communities (ADAPT project) (to KC).

References

- 1.Galli SJ, Nakae S, Tsai M. Mast cells in the development of adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:135–142. doi: 10.1038/ni1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bingham CO, Austen KF., 3rd Mast-cell responses in the development of asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000;105:S527–S534. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(00)90056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robbie-Ryan M, Brown M. The role of mast cells in allergy and autoimmunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2002;14:728–733. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Secor VH, Secor WE, Gutekunst CA, Brown MA. Mast cells are essential for early onset and severe disease in a murine model of multiple sclerosis. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:813–822. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee DM, et al. Mast cells: a cellular link between autoantibodies and inflammatory arthritis. Science. 2002;297:1689–1692. doi: 10.1126/science.1073176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun J, et al. Mast cells promote atherosclerosis by releasing proinflammatory cytokines. Nat. Med. 2007;13:719–724. doi: 10.1038/nm1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun J, et al. Mast cells modulate the pathogenesis of elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:3359–3368. doi: 10.1172/JCI31311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coussens LM, et al. Inflammatory mast cells up-regulate angiogenesis during squamous epithelial carcinogenesis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1382–1397. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weisberg SP, et al. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rocha VZ, et al. Interferon-gamma, a Th1 cytokine, regulates fat inflammation: a role for adaptive immunity in obesity. Circ. Res. 2008;103:467–476. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.177105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu H, et al. T-cell accumulation and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted upregulation in adipose tissue in obesity. Circulation. 2007;115:1029–1038. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.638379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fantuzzi G. Adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005;115:911–919. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duttlinger R, et al. The Wsh and Ph mutations affect the c-kit expression profile: c-kit misexpression in embryogenesis impairs melanogenesis in Wsh and Ph mutant mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U S A. 1995;92:3754–3758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eigen H, et al. Evaluation of the addition of cromolyn sodium to bronchodilator maintenance therapy in the long-term management of asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1987;80:612–621. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(87)90016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paterson WG. Role of mast cell-derived mediators in acid-induced shortening of the esophagus. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:G385–G388. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.2.G385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shin HY, Kim JS, An NH, Park RK, Kim HM. Effect of disodium cromoglycate on mast cell-mediated immediate-type allergic reactions. Life Sci. 2004;74:2877–2887. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grimbaldeston MA, Chen CC, Piliponsky AM, Tsai M, Tarn SY, Galli SJ. Mast cell-deficient W-sash c-kit mutant Kit W-sh/W-sh mice as a model for investigating mast cell biology in vivo. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;167:835–848. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62055-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol. Rev. 2004;84:277–359. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koban M, Swinson KL. Chronic REM-sleep deprivation of rats elevates metabolic rate and increases UCP1 gene expression in brown adipose tissue. Am.J. Physiol.Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E68–E74. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00543.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santone DJ, Shahani R, Rubin BB, Romaschin AD, Lindsay TF. Mast cell stabilization improves cardiac contractile function following hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008;294:H2456–H2464. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00925.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serna H, Porras M, Vergara P. Mast cell stabilizer ketotifen [4-(l-methyl-4-piperidylidene)-4h–enzo[4,5]cyclohepta[l,2-b]thiophen-10(9H)-one fumarate] prevents mucosal mast cell hyperplasia and intestinal dysmotility in experimental Trichinella spiralis inflammation in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;319:1104–1111. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galli SJ, Kitamura Y. Genetically mast-cell-deficient W/Wv and Sl/Sld mice. Their value for the analysis of the roles of mast cells in biologic responses in vivo. Am. J. Pathol. 1987;127:191–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crandall DL, Hausman GJ, Krai JG. A review of the microcirculation of adipose tissue: anatomic, metabolic, and angiogenic perspectives. Microcirculation. 1997;4:211–232. doi: 10.3109/10739689709146786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rupnick MA, et al. Adipose tissue mass can be regulated through the vasculature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99:10730–10735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162349799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pang C, et al. Macrophage Infiltration into Adipose Tissue May Promote Angiogenesis for Adipose Tissue Remodeling in Obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;295:E313–E322. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90296.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kintscher U, et al. T-lymphocyte infiltration in visceral adipose tissue: a primary event in adipose tissue inflammation and the development of obesity-mediated insulin resistance. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008;28:1304–1310. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.165100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sato K, et al. Autophagy is activated in colorectal cancer cells and contributes to the tolerance to nutrient deprivation. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9677–9684. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skoura A, et al. Essential role of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 2 in pathological angiogenesis of the mouse retina. J.Clin.Invest. 2007;117:2506–2516. doi: 10.1172/JCI31123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu J, et al. Proteolytic exposure of a cryptic site within collagen type IV is required for angiogenesis and tumor growth in vivo. J.Cell Biol. 2001;154:1069–1079. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang B, et al. Cathepsin S controls angiogenesis and tumor growth via matrix-derived angiogenic factors. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:6020–6029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi GP, Munger JS, Meara JP, Rich DH, Chapman HA. Molecular cloning and expression of human alveolar macrophage cathepsin S, an elastinolytic cysteine protease. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:7258–7262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolters PJ, et al. Tissue-selective mast cell reconstitution and differential lung gene expression in mast cell-deficient Kit(W-sh)/Kit(W-sh) sash mice. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2005;35:82–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang M, et al. Cathepsin L activity controls adipogenesis and glucose tolerance. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:970–977. doi: 10.1038/ncb1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hadigan C, et al. Fasting hyperinsulinemia and changes in regional body composition in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999;84:1932–1937. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.6.5738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wild R, Ramakrishnan S, Sedgewick J, Griffioen AW. Quantitative assessment of angiogenesis and tumor vessel architecture by computer-assisted digital image analysis: effects of VEGF-toxin conjugate on tumor microvessel density. Microvasc. Res. 2000;59:368–376. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1999.2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.