Abstract

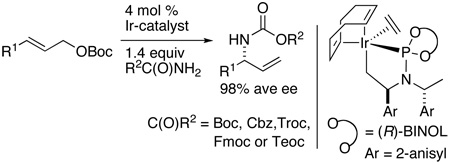

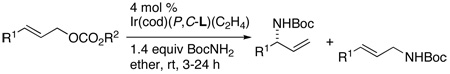

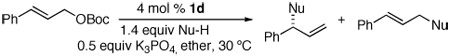

The direct reaction between carbamates and achiral allylic carbonates to form branched, conveniently protected primary allylic amines with high regioselectivity and enantioselectivity is reported. This process occurs without base or with 0.5 equiv K3PO4 in the presence of a metalacyclic iridium catalyst containing a labile ethylene ligand. The reactions of aryl, heteroaryl and alkyl-substituted allylic carbonates with BocNH2, FmocNH2, CbzNH2, TrocNH2, TeocNH2, and 2-oxazolidinone occur in good yields, with high selectivity for the branched isomer, and high enantioselectivities (98% average ee).

Chiral, non-racemic N-allyl carbamates are versatile intermediates for the synthesis of a variety of products,1 including α-, β-, and γ- amino acids and amino alcohols. One of the most direct methods for the synthesis of these materials would be a simple intermolecular, catalytic, enantioselective allylic substitution with carbamate nucleophiles (eq 1).2 However, this process has been reported to lead to little or no conversion in the presence of Pd3 or Ir4 catalysts. Related intermolecular Pd-catalyzed allylations of primary amides have been accomplished with O-allyl isoureas, but mixtures of mono- and di-allylation products were obtained.5

|

(1) |

In order to overcome this limitation, alternate protocols involving the use of alkali iminodicarboxylate3,4,6,7 nucleophiles, in situ generated benzyl N-carboxycarbamate nucleophiles,8 or the rearrangement of O-allylic trichloroimidates9 have been developed. However, these Ir-and Pd-catalyzed routes to N-allyl carbamates require manipulation of the products to generate primary amines with conventional protective groups or more extensive substrate synthesis than for a direct addition.10 Here, we report the discovery and development of a direct, enantioselective, iridium-catalyzed substitution of a series of allylic carbonates with carbamate nucleophiles to form branched N-allyl carbamates in high yields, branched-to-linear ratios and enantioselectivities. The reactions occur with Boc, Cbz, Troc, Fmoc, and Teoc carbamates to form conveniently protected primary allylic amines.

To assess the feasibility of preparing non-racemic, α-chiral, N-allyl carbamates by direct asymmetric allylic substitution, we investigated the reactions of BocNHM (M = Li, Na, K) with tert-butyl cinnamyl and tert-butyl dodecenyl carbonates. We conducted these reactions in the presence of the catalyst formed from a mixture of L1 (Figure 1) and [Ir(cod)Cl]2 activated in situ, as we have previously reported,11 by addition of propylamine. However, reactions of these carbamate salts led to modest yields of the desired product (≤25 %).3–5 Reactions of the neutral carbamate in the presence of weak bases12 provided the desired products in higher yields, but even the highest yielding reactions, which occurred with K3PO4 (100 mol %) as base, occurred in only 38% yield with tert-butyl dodecenyl carbonate and 64% yield with tert-butyl cinnamyl carbonate.

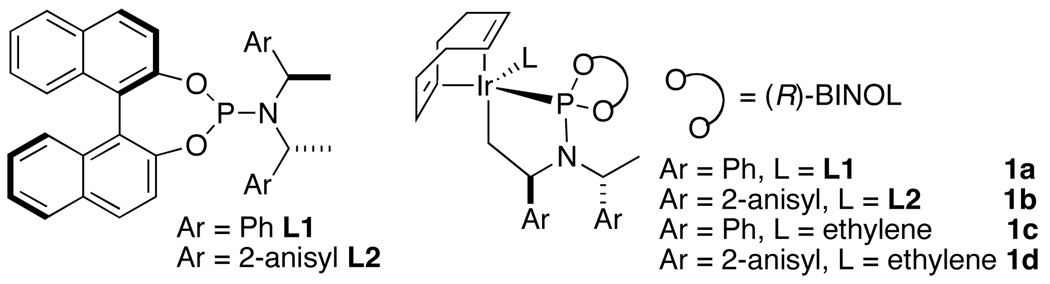

Figure 1.

Phosphoramidite ligands and cyclometallated Ir catalysts.

To improve this process further, we investigated a series of catalyst precursors (Figure 1). These studies showed that the most effective catalysts for the asymmetric allylation of tert-butyl carbamate are 1a–d. Complex 1c has been used for mechanistic analysis, and complexes 1c and 1d (derived from ligand L213–15) have recently been used for asymmetric allylation of azoles.16 The reactions conducted with 1d provided the desired branched products with the highest yields and branched-to-linear (b:l) selectivities. In general, reactions conducted with the ethylene catalyst 1d derived from ligand L2 occurred with somewhat higher b:l selectivities and faster rates than those conducted with the analogous catalyst 1c derived from ligand L1. For example, the branched-to-linear regioselectivity of reactions of linear aliphatic carbonates improved from 75:25 to 85:15. Moreover, the allylation reactions conducted with catalyst 1d occurred without the need for additional base or with only 0.5 equiv of K3PO4 as base.

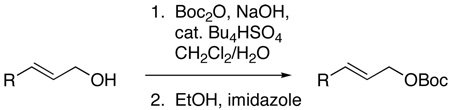

Studies on the reactions of allylic acetates and a series of allylic carbonates with tert-butylcarbamate showed that reactions conducted with allylic tert-butyl carbonates gave the highest yields of branched products from the carbonates tested (eq 1, R2 = Ac, MeO2C, EtO2C, t-BuO2C, MeOCH2C(O)). Lower yields were observed when the reaction was conducted with allylic ethyl or methyl carbonates. These lower yields were due to the formation of ether side products from decarboxylation.17 Reactions with allylic acetates were much slower (OAc) or low yielding (MeOCH2C(O)). Using a modified combination of two literature procedures,18,19 we realized a more convenient synthesis of pure allylic tert-butyoxy carbonates (eq 2, see supporting information).

|

(2) |

Studies on the effect of solvent (THF, 2-methyl-THF, CH2Cl2, toluene, ether, dioxane, and DME were tested) showed that reactions performed in THF or ether formed the highest yields of branched product. Although reactions in CH2Cl2 occurred with the highest regioselectivity, the yield of branched allylic carbamate remained low (40–60%). The yield, regioselectivity, and enantioselectivity were generally similar for reactions conducted in THF and ether, but the reactions in ether were typically faster.

The optimized conditions were then applied to the reactions of a variety of allylic tert-butyl carbonates, and the results of these experiments are summarized in Table 1. High yields of the desired product, and, with one exception, acceptable branched-to-linear ratios were obtained. In all cases the branched and linear products were separable using standard flash chromatography on silica gel. All reactions occurred with exceptional enantioselectivity.

Table 1.

Reaction of a variety of allylic carbonates with BocNH2.

| entrya | product | b:lb | yield (%)c | ee (%)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

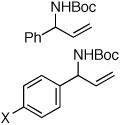

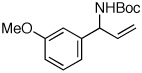

| 1e |  |

94:6 | 85 | 99 |

| 2f | X = CF3 | 81:19 | 65 | 99 |

| 3f | X = Br | 91:9 | 79 | 99 |

| 4 | X = OMe | 99:1 | 85 | 99 |

| 5 |  |

95:5 | 81 | 99 |

| 6 |  |

83:17 | 50 | 98 |

| 7 | 89:11 | 79 | 95 | |

| 8 |  |

85:15 | 65 | 97 |

| 9 | 83:17 | 61 | 97 | |

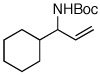

| 10f,g |  |

55:45 | 25 | 99 |

General conditions: 0.7 mmol BocNH2, 0.5 mmol carbonate, 0.02 mmol 1d, and 10 µL dodecane in 0.5 mL ether. Results are an average of two runs.

Determined by NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture or isolation.

Isolated yield of branched product.

Determined by chiral HPLC analysis, see Supporting Information for details.

THF was used as solvent.

K3PO4 (0.25 mmol) was added.

Reaction was run at 30 °C.

A pronounced electronic effect was seen in the reactions of substituted cinnamyl carbonates (entries 1–5). The reactions of more electron-rich carbonates occurred with higher b:l selectivity and faster rates than reactions of more electron-poor carbonates. Reactions of allylic carbonates containing heteroaromatic (furan, entry 6), dienyl (entry 7), and straight-chain aliphatic (entry 8) moieties also yielded the desired products in good yield and excellent enantioselectivity. The reaction of a benzyloxy-substituted allylic carbonate (entry 9) yielded results similar to the unfunctionalized straight-chain aliphatic carbonate. In contrast to a previously reported Ir-catalyzed reaction utilizing a benzyl carboxycarbamate nucleophile,20 the aminoalcohol derivative was formed with high enantioselectivity under our new conditions. Reaction of an aliphatic substrate with branching α-to the allyl unit (R1 = Cy, entry 10) occurred in a low isolated yield due to low reactivity (reactions required 48 h to consume starting material) and poor b:l selectivity. The enantioselectivity of the reaction, however, remained high.

Although Boc is among the most common protecting groups for primary amines, sometimes the acidic deprotection conditions are incompatible with other funcitonality in the molecule. In these cases other carbamate protecting groups are required. The reactivity of a representative sample of these carbamates toward the iridium-catalyzed asymmetric allylation is summarized in Table 2. The reactions with 2,2,2-trichloroethoxycarbamate (TrocNH2), benzyloxy-carbamate (CbzNH2), fluorenyloxycarbamate (FmocNH2), and 2-trimethylsilylethoxycarbamate (TeocNH2) that are deprotected with Zn0, H2, base, or F−, respectively, all afforded acceptable yields of the branched product.

Table 2.

Synthesis of a variety of different N-allyl carbamates.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entrya | Nu-H | time (h) | b:lb | yield (%)c | ee (%)d |

| 1 | FmocNH2 | 21 | 83:17 | 57 | 94 |

| 2 | CbzNH2 | 9 | 80:20 | 74 | 97 |

| 3e | TrocNH2 | 10 | 96:4 | 80 | 95 |

| 4 | TeocNH2 | 10 | 80:20 | 73 | 98 |

| 5e | 2-oxazolidinone | 12 | 99:1 | 72 | 99 |

General conditions: 0.7 mmol BocNH2, 0.5 mmol tert-butyl cinnamyl carbonate, 0.02 mmol 1d, 0.25 mmol K3PO4, and 10 µL dodecane in 0.5 mL ether. Reactions were heated to 30 °C. Results are an average of two runs.

Determined by NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture or by isolation.

Isolated yield of branched product.

Determined by chiral HPLC analysis, see Supporting Information for details.

DBU (0.1 mmol) was used in place of K3PO4.

In some cases, the reactions of the carbamates were accelerated by the addition of DBU. For example, the allylation of TrocNH2 and a secondary carbamate, 2-oxazolidinone (Table 2, entry 5) occurred in high yield, branched-to-linear selectivity and enantioselectivity when 20 mol % DBU was used in place of K3PO4 as the base. DBU did not improve reactions of BocNH2 or CbzNH2.

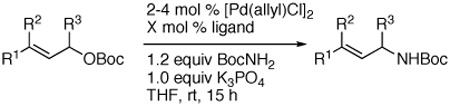

To determine if these conditions could be transferred to palladium-catalyzed, intermolecular allylation of carbamates, we tested the N-allylation of tert-butyl carbamate with tert-butyl cinnamyl carbonate in the presence of both achiral and chiral catalysts (Table 3). Of catalysts containing PPh3, Trost’s ligand,21 L2, and Xantphos (9,9-Dimethyl-4,5-bis(diphenylphosphino)-xanthene), only 4 mol % [{(η3-C3H5)PdCl}2] and 8 mol % Xantphos formed the substitution product in good yield (93% isolated yield). In this case, however, the allylic substitution formed exclusively the linear isomer (entry 1).22

Table 3.

Conditions tested for palladium-catalyzed N-allylation of tert-butyl carbamate.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R1,R2,R3 | ligand (X mol %) | yield (%) | b:l |

| 1a | Ph, H, H | Xantphos (8) | 93 | 1:>99b |

| 2 a | Ph, H, H | Trost’s ligand (8) | N.R.c | --- |

| 3 a | Ph, H, H | PPh3 (16) | N.R.c | --- |

| 4 a | Ph, H, H | (R,R,R)-L2 (16) | N.R.c | --- |

| 5 | Ph, H, Ph | PPh3 (8) | N.R.c | --- |

| 6 | H, -C3H6- | Xantphos (4)d | N.R.c | --- |

| 7 | H, -C3H6- | Trost’s ligand (4)d | N.R.c | --- |

| 8 | H, -C3H6- | Trost’s ligand (2)e | N.R.c | --- |

1.2 equiv K3PO4 was used.

Determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

N.R.: No Reaction.

2 mol % [Pd(allyl)Cl]2 was used as catalyst precursor.

2 mol % Pd(dba)2 was used as precursor.

In summary, we have identified conditions for Ir- and Pd-catalyzed intermolecular direct mono-allylation of carbamates, a process that has fallen outside the scope of allylic substitution chemistry. The simplicity and availability of the reagents, the mild conditions, and the broad scope – including the scope of carbamate nucleophile – are particular attributes of this protocol. Moreover, the Ir-catalyzed procedure is highly enantioselective. Although the regioselectivity is not as high as was observed for decarboxylative processes,8 the substrates are more available and the pure branched products are easily obtained by chromatrography on silica gel. Work to extend this method to the allylation of amides is ongoing.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures and spectral data for the synthesis of the allylic carbonates, catalyst 1d, and allylated carbamate products as well as two additional tables of reaction optimization experiments.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge financial support from the NIH (GM-55382 to JFH and GM075703 to DJW) and a gift of [Ir(cod)Cl]2 from Johnson-Matthey. We thank Sanjeev Dalavoy of the Univerity of Illinois for the synthesis of several allylic alcohols and Levi Stanley of the University of Illinois for assistance with NMR characterization.

References

- 1.Johannsen M, Jorgensen KA. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:1689–1708. doi: 10.1021/cr970343o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee A, Ellman JA. Org. Lett. 2001;3:3707–3709. doi: 10.1021/ol0166496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connell RD, Rein T, Aakermark B, Helquist P. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:3845–3849. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh OV, Han H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:7094–7098. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.01.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inoue Y, Taguchi M, Hashimoto H. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1985;58:2721–2722. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weihofen R, Tverskoy O, Helmchen G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:5546–5549. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pouy MJ, Leitner A, Weix DJ, Ueno S, Hartwig JF. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3949–3952. doi: 10.1021/ol701562p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh OV, Han H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:774–775. doi: 10.1021/ja067966g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Overman LE, Carpenter NE. Org. React. (N.Y.) 2005;66:1–107. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Defieber C, Ariger MA, Moriel P, Carreira EM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:3139–3143. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leitner A, Shu C, Hartwig JF. Org. Lett. 2005;7:1093–1096. doi: 10.1021/ol050029d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Many bases were tested, and only reactions conducted with K3PO4, Cs2CO3 and CsF resulted in high yields of the desired product. See Supporting Information for details.

- 13.Feringa BL. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:346–353. doi: 10.1021/ar990084k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexakis A, Polet D. Org. Lett. 2004;6:3529–3532. doi: 10.1021/ol048607y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leitner A, Shekhar S, Pouy MJ, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:15506–15514. doi: 10.1021/ja054331t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stanley LM, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131 doi: 10.1021/ja902243s. ASAP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ueno S, Hartwig JF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:1928–1931. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basel Y, Hassner A. Synthesis. 2001:550–552. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houlihan F, Bouchard F, Fréchet JMJ, Willson CG. Can. J. Chem. 1985;63:153–162. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh OV, Han H. Org. Lett. 2007;9:4801–4804. doi: 10.1021/ol702115h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Trost BM, Van Vranken DL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1992;31:228–230. see Supporting Information for the structures.

- 22.Initial attempts to conduct enantioselective Pd-catalyzed carbamate allylation reactions have been unsuccessful.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures and spectral data for the synthesis of the allylic carbonates, catalyst 1d, and allylated carbamate products as well as two additional tables of reaction optimization experiments.