Abstract

Left ventricular mass (LVM) and cardiac gene expression are complex traits regulated by factors both intrinsic and extrinsic to the heart. To dissect the major determinants of LVM, we combined expression quantitative trait locus1 and quantitative trait transcript2 (QTT) analyses of the cardiac transcriptome in the rat. Using these methods and in vitro functional assays, we identified osteoglycin (Ogn) as a major candidate regulator of rat LVM, with increased Ogn protein expression associated with elevated LVM. We also applied genome-wide QTT analysis to the human heart and observed that, out of ~22,000 transcripts, OGN transcript abundance had the highest correlation with LVM. We further confirmed a role for Ogn in the in vivo regulation of LVM in Ogn knockout mice. Taken together, these data implicate Ogn as a key regulator of LVM in rats, mice and humans, and suggest that Ogn modifies the hypertrophic response to extrinsic factors such as hypertension and aortic stenosis.

Elevated indexed LVM is a major cause of morbidity and mortality and is regulated, in part, by hemodynamic indices3. However, only a small proportion of LVM variation is determined by hemodynamic effects4, and it has been proposed that genetic influences may also be important5,6. Many studies have shown that gene expression is heritable and that the genetic control of transcription affects physiological traits and disease phenotypes1,7. We have shown that gene transcription is highly heritable in the rat heart8, which led us to hypothesize that the genetic control of cardiac gene expression may be important in regulating LVM. Here, we used an integrated approach combining correlation of expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL)1 and genome-wide expression profiles with physiological traits, previously designated as quantitative trait transcript (QTT) analysis2, to identify genetic determinants of LVM.

We examined regulation of LVM using the BXH/HXB panel of rat recombinant inbred (RI) strains, derived from a cross of the Brown Norway (BN) rat and the spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR)1. We generated blood pressure telemetry data across the RI strains to assess the influence of averaged blood pressure on LVM (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). Our data showed that LVM correlated poorly with physiological variation in blood pressure (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Previous studies have shown an effect of extreme pressure overload on cardiac gene expression9; however, apart from a small subset of genes (Supplementary Table 1 online), we observed limited correlation with systolic blood pressure (SBP, median r = 0.14, 25th–75th percentiles 0.07–0.23) or diastolic blood pressure (DBP, median r = 0.13, 25th–75th percentiles 0.06–0.22). These findings are consistent with a recent study that showed limited effects of blood pressure on cardiac gene expression in three hypertensive rat strains, including the SHR10.

We then carried out eQTL analysis in the rat heart and detected 1,444 cis and 2,300 trans eQTLs at a genome-wide corrected P value (PGW) of 0.05 (Supplementary Fig. 2a,b online), with a predominance of cis eQTLs at more stringent P values (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Robustly mapped cis-regulated transcripts (false discovery rate (FDR) <5%, relative change >1.5) in the heart that colocalize with previously mapped cardiac mass or LVM QTLs represent candidate genes for these traits in the rat (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 online). Two of these candidate genes, α1β-adrenergic receptor (Adra1b) and thioredoxin 2 (Txn2), are major determinants of cardiac hypertrophy in the mouse11,12.

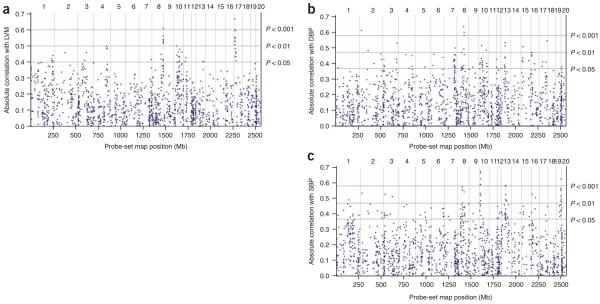

We next performed genome-wide QTT analysis for all eQTLs against LVM, SBP and DBP (Supplementary Table 4 online) to identify cis eQTLs that correlated with LVM but not with blood pressure as primary candidate genes for the regulation of LVM. We observed the most significant QTT for a group of nine cis-regulated transcripts that were highly correlated with LVM and were encoded on chromosome 17p14 (Fig. 1a). Neither SBP nor DBP showed significant association with LVM by QTT analysis at this locus (Fig. 1b,c). This genomic region contains a QTL for LVM in the BXH/HXB RI strains5 that we refined using additional microsatellite markers. A peak lod score of 3.98 was observed at the genetic marker Drd1a. Within the 2-lod support interval for this QTL (~7 cM), 113 transcripts (out of 151) reached nominal significance (P < 0.05) of cis linkage (Fig. 2a,b), and 23 transcripts remained significant after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. We prioritized cis eQTLs that correlated with LVM as candidate genes on the basis of the significance of their cis linkage and the extent of their differential expression, as previously described13. This identified two genes: the extracellular matrix (ECM) protein osteoglycin (Ogn; P = 1.9 × 10−8) and an iron-sulfur cluster assembly-1 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) homolog (Isca1; also known as HesB-like domain–containing 2 (Hbld2); P = 5.9 × 10−7) (Fig. 2b). We then fine-mapped the LVM QTL using SNPs, which excluded Hbld2 as a positional candidate (Supplementary Table 5 online). These analyses prioritized Ogn as the only cis-regulated transcript that was both highly differentially regulated and correlated with LVM, but they do not exclude influences from other genes within the refined QTL interval. Sequence analysis of Ogn revealed several SNPs and a 47-bp indel in the 3′ UTR of the gene (Fig. 2c).

Figure 1.

Quantitative trait transcripts analysis of cis eQTLs with physiological traits in the rat. Expression profiles of the 1,444 cis eQTLs (PGW = 0.05) were correlated with values of (a) indexed LVM, (b) DBP and (c) SBP measured in the BXH/HXB RI strain panel. For each cis eQTL across the rat genome, the absolute Pearson correlation coefficient with the physiological traits is plotted against the location of the probe set (Mb). Vertical lines, physical position of the end of each rat chromosome. The number of each chromosome is given on the upper y axis. The horizontal lines indicate empirical significance levels P = 0.05, P = 0.01 and P = 0.001 of the correlations (see Methods).

Figure 2.

Candidate cis-regulated genes within the rat QTL for left ventricular mass. (a) Interval mapping of LVM to chromosome 17p14 in the BXH/HXB RI strain panel. Horizontal dashed line, genome-wide threshold for significance (P = 0.05) of linkage derived by 10,000 permutations; 2-lod support interval region, by vertical box (dotted lines). Positions of the genetic markers are also indicated along the x axis. (b) Volcano plot of significance of cis eQTLs against their relative change in expression. Circles represent 113 transcripts physically encoded within the 2-lod support interval of the QTL and showing cis linkage at their nearest markers (nominal P < 0.05, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test). For each transcript, the negative log10 of the P value of linkage is plotted against the relative change in gene expression at the peak of linkage. Dashed horizontal line, significance threshold (P = 0.00033) after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing owing to the number of transcripts in the region that were tested for cis linkage. Transcripts representing Hbld2 (one probe set) and Ogn (two probe sets) are indicated by the arrows. (c) Sequence polymorphisms in Ogn genomic DNA from 2 kb upstream of the first exon to 3 kb downstream of the stop codon. For 5′ UTR, exonic and 3′ UTR variants, positions are reported relative to the start codon; for intronic variants, positions are given relative to the nearest exon. The sequences variation at position 348 in exon 3 of Ogn is synonymous. Ins, insertion. (d) Regulation of Ogn in a blood pressure–independent in vitro model of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy: neonatal rat ventricular myocytes stimulated with phenylephrine for the times shown and assayed by quantitative RT-PCR for changes in Ogn mRNA expression. Mean relative change (± s.e.m.) in gene expression as compared to control samples over the time course of the experiment; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Subsequently, we used primary cultures of neonatal cardiac myocytes to examine the regulation of Ogn in response to hypertrophic stimulation by phenylephrine; this is an established and blood pressure–independent in vitro model of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy14. During the course of the hypertrophic response, Ogn transcript levels were significantly downregulated (Fig. 2d). As expected, natriuretic peptide precursor A (Nppa), a biomarker of cardiac hypertrophy, was upregulated in the model14 (Supplementary Fig. 3a online). Adra1b and Txn2 (Supplementary Fig. 3b,c), established determinants of LVM in the mouse11,12 and candidate genes in the rat (Supplementary Table 2), showed dynamic regulation similar to that observed for Ogn. These eQTL, QTT and in vitro results, taken together with recent finding that ECM proteins are critical determinants of cardiac hypertrophy15,16, prioritize Ogn as a strong positional and biological candidate for LVM in the rat.

To translate our findings to humans, we generated genome-wide expression profiles of the human heart using biopsies collected from 20 individuals with aortic stenosis and elevated LVM and from seven control subjects. From this cohort, we selected subjects at the extremes of the distribution of LVM (see Methods) to identify genes that show strong differential regulation between individuals with high and low LVM. Differentially regulated genes (FDR ≤ 5%, relative change >1.5) that correlated most highly with LVM across the study population are reported in Table 1. Notably, out of the 22,284 transcripts considered, OGN, the human ortholog of rat Ogn, correlated most strongly with LVM, and this correlation remained significant after controlling for the presence or absence of aortic stenosis (r = 0.45, P = 0.02). NPPA and natriuretic peptide precursor B (NPPB), biomarkers of cardiac hypertrophy, were upregulated in individuals with aortic stenosis (aortic stenosis versus controls; relative change = 2.6, P = 0.006 and relative change = 9.5, P = 0.01, respectively); however, unlike OGN, they did not significantly correlate with LVM when the test was made conditional on aortic stenosis status. We then analyzed two more published microarray datasets and independently replicated the association of OGN with increased LVM and markers of hypertrophy in these cohorts (Supplementary Table 6 online).

Table 1.

Differentially expressed genes in human cardiac hypertrophy and associated with indexed left ventricular mass

| Probe identifier | Gene symbol | Gene name | Relative changea | FDRb (%) | Correlation with LVMc | P valued |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 218730_s_at | OGN | Osteoglycin | 2.2 | 2.7 | 0.62 | 1.2 × 10−3 |

| 202766_s_at | FBN1 | Fibrillin 1 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 0.55 | 4.5 × 10−3 |

| 209621_s_at | PDLIM3 | PDZ and LIM domain 3 | 1.6 | 5.0 | 0.52 | 6.5 × 10−3 |

| 219087_at | ASPN | Asporin | 1.9 | 5.0 | 0.52 | 7.5 × 10−3 |

| 213646_x_at | TUBA1B | Tubulin, alpha 1b | 1.5 | 2.7 | 0.52 | 5.7 × 10−3 |

| 213765_at | MFAP5 | Microfibrillar associated protein 5 | 1.8 | 5.0 | 0.51 | 6.8 × 10−3 |

| 203570_at | LOXL1 | Lysyl oxidase-like 1 | 1.5 | 5.0 | 0.51 | 8.1 × 10−3 |

| 208782_at | FSTL1 | Follistatin-like 1 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 0.51 | 1.1 × 10−2 |

| 213867_x_at | ACTB | Actin, beta | 1.5 | 2.7 | 0.49 | 1.1 × 10−2 |

| 212614_at | ARID5B | AT rich interactive domain 5B | 1.6 | 2.7 | 0.49 | 9.9 × 10−3 |

| 216442_x_at | FN1 | Fibronectin 1 | 1.9 | 5.0 | 0.49 | 1.1 × 10−2 |

| 211750_x_at | TUBA1C | Tubulin, alpha 1c | 1.6 | 2.7 | 0.48 | 1.3 × 10−2 |

| 212582_at | OSBPL8 | Oxysterol binding protein-like 8 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 0.48 | 1.1 × 10−2 |

| 221729_at | COL5A2 | Collagen, type V, alpha 2 | 1.9 | 5.0 | 0.48 | 1.3 × 10−2 |

| 201843_s_at | EFEMP1 | EGF- fibulin-like extracellular matrix protein 1 | 1.8 | 5.0 | 0.48 | 1.2 × 10−2 |

| 202007_at | NID1 | Nidogen 1 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 0.47 | 1.6 × 10−2 |

| 203548_s_at | LPL | Lipoprotein lipase | 1.8 | 2.7 | 0.47 | 1.7 × 10−2 |

| 205547_s_at | TAGLN | Transgelin | 2.1 | 2.7 | 0.46 | 1.7 × 10−2 |

| 202552_s_at | CRIM1 | Cysteine rich transmembrane BMP regulator 1 | 1.6 | 3.9 | 0.46 | 1.9 × 10−2 |

| 201012_at | ANXA1 | Annexin A1 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 0.46 | 1.7 × 10−2 |

| 209460_at | ABAT | 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase | 1.6 | 2.7 | 0.45 | 2.0 × 10−2 |

| 201302_at | ANXA4 | Annexin A4 | 1.5 | 3.9 | 0.44 | 2.1 × 10−2 |

| 219260_s_at | C17orf81 | Chromosome 17 open reading frame 81 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 0.44 | 2.4 × 10−2 |

| 209130_at | SNAP23 | Synaptosomal-associated protein, 23kda |

1.5 | 5.0 | 0.44 | 2.6 × 10−2 |

| 209392_at | ENPP2 | Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/ phosphodiesterase 2 |

1.6 | 2.7 | 0.43 | 2.7 × 10−2 |

| 200974_at | ACTA2 | Actin, alpha 2, smooth muscle, aorta | 1.6 | 2.7 | 0.43 | 2.8 × 10−2 |

| 210942_s_at | ST3GAL6 | ST3 beta-galactoside alpha-2,3-sialyltransferase 6 | 1.5 | 5.0 | 0.42 | 3.3 × 10−2 |

| 212063_at | CD44 | CD44 molecule | 1.9 | 3.9 | 0.42 | 3.0 × 10−2 |

| 212515_s_at | DDX3X | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 3, X-linked | 1.5 | 5.0 | 0.41 | 3.6 × 10−2 |

| 211509_s_at | RTN4 | Reticulon 4 | 1.6 | 3.9 | 0.41 | 3.7 × 10−2 |

| 209387_s_at | TM4SF1 | Transmembrane 4 L six family member 1 | 1.8 | 2.7 | 0.40 | 4.0 × 10−2 |

| 219922_s_at | LTBP3 | Latent transforming growth factor beta binding protein 3 | 1.5 | 5.0 | 0.40 | 4.3 × 10−2 |

| 202119_s_at | CPNE3 | Copine III | 1.5 | 3.9 | 0.40 | 4.8 × 10−2 |

| 210095_s_at | IGFBP3 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 0.39 | 5.0 × 10−2 |

Relative change in expression between subjects with low (≤93 g/m2) and high (≥142 g/m2) LVM in the study population.

False discovery rate for differential expression, estimated by SAM analysis.

Data are ranked according to decreasing values of the Pearson correlation with LVM (determined noninvasively by echocardiography).

Empirical P values for the correlations were calculated by 10,000 permutations.

In our cohort of all subjects considered for the biopsy studies, we observed a weak correlation of LVM with peak velocity across the aortic valve (Vmax; Fig. 3a) and aortic valve area index (AVAI; Fig. 3b), established clinical measures of aortic stenosis severity17. However, as calculation of LVM by echocardiography relies on assumptions of left ventricular geometry, we studied an independent cohort of subjects with aortic stenosis in which LVM, Vmax and AVAI were assessed by cardiac MRI. This confirmed limited effects of pressure indices on variation in LVM (Fig. 3c,d). Our data suggest that the severity of aortic valve narrowing, the major extrinsic stimulus for LVM in patients with aortic stenosis, determines only a limited amount of LVM variation.

Figure 3.

Correlation between hemodynamic indices and indexed LVM in individuals with aortic stenosis. (a–d) We observed little correlation between LVM and peak velocity across the aortic valve (Vmax) or indexed aortic valve area (AVAI), indices of aortic stenosis severity and hemodynamic pressure, in two independent cohorts of subjects with aortic stenosis characterized by echocardiography (a,b, n = 45) or cardiac MRI (c,d, n = 123), respectively. The percentage of variance of LVM accounted for by hemodynamic indices after including all significant covariates (R2) is indicated.

On review of the association of Ogn expression with LVM, we observed an apparent inconsistency in the direction of the correlation between species (r = −0.46, rat; r = 0.62, human). However, differential expression, as determined by microarrays, can reflect sequence variation or alternative splicing in the 3′ UTR18. Further analysis revealed that, of four microarray probe sets for rat Ogn, two mapped as cis eQTLs and correlated with LVM variation, whereas two did not (Supplementary Fig. 4 online), suggestive of alternative splicing in the 3′ UTR, which was confirmed by RT-PCR (Fig. 4a). This alternative splicing resulted in two isoforms of the 3′ UTR: a short isoform (~106 bp) that was more abundant in the BN strain and a long isoform (~1,560 bp) that was more abundant in the SHR strain (Fig. 4b). The allelic effect of the 47-bp sequence polymorphism (Fig. 2c) on the abundance of the 3′ UTR isoforms was confirmed across the RI strains (P < 10−11 for both isoforms; Fig. 4c). By luciferase assay, the short isoform was more efficient for protein production than the long isoform (Fig. 4d), and there was three times the expression of Ogn protein in BN heart as in SHR heart (Fig. 4e,f). To determine the cell types expressing Ogn in the heart, we examined primary cultures of neonatal cardiac myocytes and cardiac fibroblasts, which revealed equivalent Ogn protein expression in these cell types, with greater secretion of Ogn by fibroblasts (Supplementary Fig. 5 online). We confirmed expression of Ogn in isolated adult rat cardiac myocytes by confocal microscopy, which revealed association of Ogn with the sarcomere (Fig. 4g).

Figure 4.

Molecular characterization of rat Ogn. (a) PCR products of Ogn 3′ UTR generated from BN and SHR cDNA, showing the presence of two splice variants. (b) Abundance of the 3′ UTR isoforms and total coding mRNA in the parental strains. Each data point represents the relative expression in one BN (circle) or one SHR (triangle) rat of total coding, short and long isoforms of Ogn. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001. (c) Abundance of the 3′ UTR isoforms and total coding mRNA in the RI strains. Each data point represents relative Ogn expression in one rat from each of the RI strains carrying either the BN (circle) or SHR (triangle) allele; **P < 10−11. (d) Effects of the BN and SHR 3′ UTR isoforms on protein synthesis as determined by luciferase assay. Isoforms: BN long, BN-L; BN short, BN-S; SHR long SHR-L; SHR short, SHR-S. **P < 0.0001. (e) Immunoblot of Ogn protein expression in 20 μg total protein from three BN and three SHR hearts. Immature pre-Ogn, ~50 kDa, mature Ogn protein, ~20 kDa. (f) Semiquantitative densitometry of data shown in e. **P < 0.0001. (g) Immunofluorescence confocal micrographs of isolated adult rat ventricular cardiac myocytes. Top left, sarcomeric proteins labeled with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin; top right, DAPI counterstain of nuclei; bottom left, Ogn protein detected using antibodies to Ogn and a secondary antibody labeled with Alexa Fluor 488; bottom right, merged image. Mean ± s.e.m. (d,f); NS, not significant.

Our data showed that the BN genotype at chromosome 17p14, associated with the 47-bp insertion, accounted for a considerable amount (47%) of LVM variation in the RI strains; factors explaining the remaining phenotypic variation are unknown. As the Ogn sequence variant is associated with high LVM, independently of blood pressure, and correlates with increased Ogn protein expression (Fig. 4e,f), we suggest that the 47-bp insertion, present in the BN and other strains (Supplementary Figs. 4, 6 and 7 online), promotes splicing of the Ogn 3′ UTR, and that the greater abundance of the short isoform in the BN results in higher amounts of Ogn protein. We further determined the Ogn 3′ UTR indel across 30 rat strains, selected for protein studies four strains with the insertion and five strains without and confirmed the association of the insertion with increased Ogn (P = 0.008) (Supplementary Fig. 7).

The association of Ogn transcript abundance with LVM in rats and humans led us to hypothesize that Ogn protein expression might be central to hypertrophic response irrespective of the stimulus, which could be physiological or pathophysiological. To examine this, we studied an independent cohort of individuals with concentric hypertrophy secondary to aortic stenosis or hypertensive heart disease or eccentric hypertrophy secondary to ischemic heart failure (Supplementary Table 7 online). We observed that high amounts of OGN protein were associated with elevated LVM (Spearman's correlation = 0.7, P = 0.019) whereas neither SBP (Spearman's correlation =0.1, P = 0.4) nor DBP (Spearman's correlation = 0.02, P = 0.5) correlated with OGN protein (Supplementary Table 7 and Supplementary Fig. 8 online).

To validate functionally the role of Ogn in the in vivo regulation of LVM, we studied Ogn knockout (Ogn−/−) mice19. Although we observed no difference in LVM in Ogn−/− mice as compared to controls at baseline (Fig. 5a), it is established that permissive physiological perturbations are frequently required to reveal cardiovascular phenotypes in knockout mice9,20. Therefore, we used subcutaneous angiotensin II infusion as a pro-hypertrophic stimulus and observed that Ogn+/− and Ogn−/− mice showed a significant attenuation (P = 0.002 and P = 0.02, respectively) in LVM response as compared to Ogn+/+ controls. We then determined the expression of Nppa, Nppb and α-skeletal smooth muscle actin (Acta1, a structural cellular marker of hypertrophy). This showed a significant reduction in Acta1 (P = 0.02) in the Ogn−/− mice after angiotensin II infusion (Supplementary Table 8 online), in keeping with the effects of other ECM proteins on the hypertrophic response21. Although there was no difference in SBP or DBP between the Ogn+/+ controls and either Ogn+/− or Ogn−/− mice at baseline, we observed a significant increase in DBP in the Ogn−/− mice during angiotensin II infusion (Fig. 5b). The effect of Ogn on LVM remained apparent despite the Ogn−/− mice having a higher blood pressure, which may be due to noncardiac effects of Ogn deletion.

Figure 5.

In vivo regulation of LVM in Ogn knockout mice. (a) Indexed LVM in mice at baseline and after hypertrophic stimulation by angiotensin II infusion over a 2-week period (n = 14–18 for Ogn+/+, n = 6–10 for Ogn+/− or Ogn−/−). (b) SBP and DBP in mice at baseline and after angiotensin II infusion (n = 6 for Ogn+/+, n = 3–5 for Ogn+/− or Ogn−/−). All results are given as mean ± s.e.m. P values were generated by one-way analysis of variance with the Dunnett's post hoc test for multiple comparisons using the wild-type mice (Ogn+/+) as the reference group. *P < 0.05; **P = 0.002; NS, not significant.

In summary, our data implicate Ogn as an important regulator of LVM in rats, mice and humans. Our data show that sequence variation in the Ogn 3′ UTR in the rat, which has multiple forms in other species22, is associated with increased Ogn protein expression and elevated LVM. The ENCyclopedia Of Dna Elements (ENCODE) pilot project highlighted an enrichment in indel rates in 3′ UTRs, and alternative 3′ UTR splicing contributes to disease severity and susceptibility18,23. We suggest that, in addition to modifying disease, 3′ UTR variation may also account for phenotypic variation in physiological traits. Ogn is an ECM protein and a member of the small leucine-rich repeat protein family19,24. ECM proteins are increasingly recognized as major determinants of the hypertrophic response acting, in part, through modulation of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling pathway15,16. Furthermore, mouse studies have shown that the TGF-β signaling is important for cardiac hypertrophy secondary to aortic banding25. Therefore, we speculate that Ogn may influence LVM through modulation of the TGF-β pathway. A role for the TGF-β signaling pathway in the regulation of LVM is supported by our data that show an association of LVM in humans with several important genes in this pathway (ASPN, FBN1, FSTL1, LTBP, TUBA1B and TUBA1C) (Table 1). In conclusion, we propose that variation of LVM is explained by the interplay of genetic factors6 and hemodynamic components other than conventional measures of blood pressures or aortic stenosis26. Discovery of genes, such as Ogn, and pathways that intrinsically regulate LVM may help identify new approaches for treating human heart disease.

METHODS

Rats and mice

The BXH/HXB RI strain panel has been described in detail elsewhere1,5. We determined indexed LVM by averaging measurements of LVM corrected for body weight in four to six male rats within each RI strain5. For microarray studies, we collected hearts from four males of each RI strain and five from each parental strain; the apex of the left ventricle was isolated and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Immunoblotting was performed using 8-week-old male BN and SHR males (Charles River). Ogn−/− mice were made as previously described19 and backcrossed to C57BL/6 for more than 10 generations. Details of the 27 other rat strains used are given in Supplementary Table 9 online. We studied male mice between 9 and 17 weeks old in age-matched groups. All animal procedures were performed under license from the UK Home Office or in accordance with the Animal Protection Law of the Czech Republic.

Blood pressure measurements

In the rat studies, we implanted indwelling aortic radiotelemetry transducers (Data Sciences International) at 8 weeks of age and measured arterial pressure in conscious, unrestrained rats. Radiotelemetry pressure was collected in 5-s bursts every 10 min and recorded over a period of 8 d, using 6–12 rats within each RI strain. For studies in mice, we measured tail cuff blood pressures in conscious mice that were preacclimatized to experimental conditions for 2 weeks. Blood pressure values were averaged within each RI strains and across eight sequential readings, three times per week (2 weeks before and after pump insertion).

Microarray data

RNA was extracted from heart samples and prepared for microarray analysis as previously described1. We used the Affymetrix RAE 230 2.0 and the Affymetrix U133A microarrays for rat and human studies, respectively. Gene expression summary values for Affymetrix GeneChip data were computed using the Robust Multichip Average (RMA) algorithm as described1. Relative changes were determined by RMA values, backtransformed (anti-log2) to raw intensity scale.

Expression QTL mapping

For each transcript on the microarray, eQTL linkages and false discovery rate (FDR) at a given genome-wide significance level (PGW) were determined as previously described1. We determined which eQTLs were regulated in cis or in trans by defining cis eQTLs as those with a peak of linkage within 10 Mbp of the physical location of the probe set1. To avoid misclassification of cis and trans eQTLs, probe sets whose physical position mapped to more than one place in the genome were removed from the dataset8.

Quantitative trait transcript analysis

We assessed association between gene expression levels and phenotypic variation across the population by correlating transcript abundance with the values of physiological traits2. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) and Westfall-Young corrected P values based on 10,000 permutations were calculated using Matlab version 6 (Supplementary Table 4).

QTL mapping of LVM

We performed linkage analysis of LVM data in MapManager QTXb20 using the expanded 1,011 marker set1 with another 17 fluorescently labeled microsatellite markers within the region of interest on rat chromosome 17p14 (Supplementary Table 10 online). Amplification products of microsatellite markers across the RI strain panel were detected on a 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) and genotype data analyzed using GeneMapper version 3.7 (Applied Biosystems). To refine the boundaries of the LVM QTL on rat chromosome 17p14, we carried out fine mapping of LVM using 46 informative SNPs within the QTL region. SNPs were retrieved from the STAR project consortium (see URLs below).

RT-PCR of Ogn 3′ UTR

RNA was quantified by a standard curve (RiboGreen, Invitrogen), treated with DNase I (Invitrogen) and used to make cDNA with AMV reverse transcriptase (Roche). After cDNA clean up (MicroSpin G-50 columns, Amersham), we carried out PCR was with KOD Hot Start DNA Polymerase (Novagen). PCR conditions were 95 °C (12 min), then 30 cycles of 95 °C, 30 s; 62 °C, 30 s. PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel with ethidium bromide. Primer pairs are given in Supplementary Methods online.

Quantitative RT-PCR

We used the One-Step TaqMan RT-PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) with normalization to total RNA as previously described1. Quantification of the Ogn 3′ UTR variants and assays of mouse left ventricle were performed by two-step quantitative RT-PCR (iScript cDNA Synthesis, Bio-Rad; SYBR Green I JumpStart Taq Readymix, Sigma) as per manufacturer's instructions. Primers pairs and PCR conditions are given in Supplementary Methods.

Immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry

Protein extracts from heart samples were prepared and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as previously described27. Antibodies to mouse Ogn were from R&D Systems (goat, AF2949); those to human Ogn were from Chemicon (rabbit, AB2210), and secondary antibodies were from R&D or Dako, respectively. After immunoblotting, equal loading was confirmed using Ponceau S solution (Sigma). Proteins were quantified with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). For immunohistochemistry, adult cardiac myocytes were isolated, stained and imaged as described in the Supplementary Methods.

Cloning and luciferase assay

The 3′ UTR of Ogn was amplified by PCR from BN and SHR heart cDNA (conditions as above). PCR products were gel-purified and TA cloned into pTargeT (Promega). Sequence-verified BN and SHR Ogn 3′ UTRs were subcloned to psiCHECK-2 (Promega). For luciferase assays, we seeded COS-1 cells in 24-well dishes at a density of 105 cells per well and transfected them with 100 ng of psiCHECK-2–Ogn 3′ UTR using Lipofectamine 2000. Cells were collected after 24 h and Renilla and firefly luciferase activity detected using Dual-Glo Luciferase (Promega).

Neonatal rat cardiac myocytes and cardiac fibroblast cultures

We prepared primary cultures of neonatal rat ventricular cardiac myocytes as previously described27. After serum starvation (24 h), cells were stimulated with phenylephrine (100 μM) and RNA extracted (RNeasy, Qiagen) at the specified time-points. For cultures of cardiac fibroblasts, cells were seeded on 60-mm plates during purification of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Fibroblasts were grown to confluence and passaged using standard approaches and culture conditions as used for cardiac myocytes. Cells were used for experiments at the third passage.

Human myocardial biopsies for microarray and protein studies

We obtained cardiac needle biopsies specimens from 20 individuals with aortic stenosis undergoing valve replacement surgery, selected from an extended study group of 45 characterized by echocardiography, and from seven sex-matched subjects without aortic stenosis at the time of coronary bypass grafting as previously described28 (further details are given in Supplementary Methods). LVM and aortic valve area index (AVAI) were calculated using standard echocardiography techniques and normalized to body mass index17. For differential expression analysis, two groups were selected on the basis of their LVM: individuals with low LVM (≤93 g/m2, n = 7) and individuals with high LVM (≥142 g/m2, n = 7). The cut-offs were the 25th and 75th percentiles of the LVM distribution, respectively. The local Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Maastricht approved the study.

For protein studies, we used a distinct cohort of eight subjects; details are given Supplementary Table 7. Full-thickness myocardial biopsies were taken at the time of cardiac surgery with the approval of the Hammersmith Hospital Research Ethics Committee. We obtained written informed consent from all subjects.

Cardiac MRI study

Individuals with a diagnosis of aortic stenosis who attended the Royal Brompton Hospital, London cardiac MRI unit between 2002 and 2007 were retrospectively identified from a local database with the approval of the hospital Research Ethics Committee. This identified 474 people with a diagnosis of aortic stenosis. Of this cohort, 123 had isolated aortic stenosis in the absence of confounding cardiac valve or myocardial pathology and were used for the study. The mean age of the subjects was 61.7 years (range 9–89), with 64% males and 36% females. We acquired MRI cine images, aortic blood flow velocities and gadolinium-DTPA contrast-enhanced images (1.5 Tesla, Siemens Sonata). LVM, left ventricular ejection fraction and aortic valve area planimetry, from which LVM and AVAI were calculated, were determined using standard approaches29.

Angiotensin II infusion studies

We implanted osmotic pumps (1002, Alzet) subcutaneously under general anesthesia. AII was infused (1.5 μg/g/day) for 2 weeks, while mice were housed under standard conditions. After the infusion period, mice were weighed, hearts were collected and the left ventricle was isolated by removal of the great vessels, atria and the right ventricle; it was then rinsed and blotted dry. LVMs (expressed as a percentage of body mass) of Ogn−/− mice were compared to those of littermate or wild-type Ogn+/+ mice and those of littermate Ogn+/− mice. Data were collected in single-blinded fashion.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. and were compared using a Student's t-test (or Mann-Whitney U-test, as appropriate) or repeated-measures, one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. We analyzed differential expression in the human microarray data using Statistical Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) and used 10,000 permutations to estimate the false discovery rate30. Multivariate regression analysis was carried out to evaluate the effect of indices of disease severity (Vmax, peak velocity of aortic blood flow and AVAI) on LVM in the cohorts of individuals with aortic stenosis. We built regression models by adding all significant covariates (P < 0.05), including sex, age and ejection fraction, and calculated the unique contributions (R2 values) of Vmax and AVAI to variation of LVM. Calculations were done with SPSS 12.0.

URLs

STAR project consortium, http://www.snp-star.eu/.

Accession codes

ArrayExpress: rat microarray data have been deposited under experiment number E-MIMR-222. NCBI GEO: human expression data have been deposited with accession code GSE10161.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Mice used in this study were produced by Eli Lilly, Inc., and made available to the authors. We are grateful to R. Buchan for technical assistance, to P. Froguel, A. Angius, M. Falchi and M. Schneider for comments on the manuscript, to S. Harding (National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College, London) for providing the isolated adult rat cardiac myocytes and to J. Sassard (University of Lyon) for providing DNA from the Lyon rat strains. This work was primarily supported by funding from the UK Department of Health (S.A.C. and H.L.) and the British Heart Foundation (R.S., S.A.C.). In addition, studies were supported by research grants from the Medical Research Council of UK (T.J.A., S.A.C.), the Fondation Leducq (T.J.A., S.A.C., M.B.), the EU EURATools award (T.J.A., S.A.C., N.H., M.P.), the Wellcome Trust (I.G.), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Research Scholars Program (M.P.), the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic (M.P.), the Ministry of Education of the Czech Republic (M.P., V.K.), the 2003T302 grant of the Netherlands Heart Foundation (Y.M.P), the InterCardiology Institute Netherlands (Y.M.P.), a Rubicon grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO, to B.S.), the Wellcome Trust Functional Genomics Initiative and the Biological Atlas of Insulin Resistance (BAIR) (M.K.K.), the German National Genome Research Network (NGFN2, to N.H.), and the US National Institutes of Health's National Eye Institute EY000952 and EY13395 (G.W.C.).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Genetics website.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions

References

- 1.Hubner N, et al. Integrated transcriptional profiling and linkage analysis for identification of genes underlying disease. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:243–253. doi: 10.1038/ng1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Passador-Gurgel G, Hsieh WP, Hunt P, Deighton N, Gibson G. Quantitative trait transcripts for nicotine resistance in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:264–268. doi: 10.1038/ng1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorell BH, Carabello BA. Left ventricular hypertrophy: pathogenesis, detection, and prognosis. Circulation. 2000;102:470–479. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devereux RB, et al. Relations of left ventricular mass to demographic and hemo-dynamic variables in American Indians: The Strong Heart Study. Circulation. 1997;96:1416–1423. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.5.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pravenec M, et al. Mapping of quantitative trait loci for blood pressure and cardiac mass in the rat by genome scanning of recombinant inbred strains. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;96:1973–1978. doi: 10.1172/JCI118244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Post WS, Larson MG, Myers RH, Galderisi M, Levy D. Heritability of left ventricular mass: the Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension. 1997;30:1025–1028. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.5.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Koning DJ, Haley CS. Genetical genomics in humans and model organisms. Trends Genet. 2005;21:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petretto E, et al. Heritability and tissue specificity of expression quantitative trait loci. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoshijima M, Chien KR. Mixed signals in heart failure: cancer rules. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:849–855. doi: 10.1172/JCI15380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerutti C, et al. Transcriptional alterations in the left ventricle of three hypertensive rat models. Physiol. Genomics. 2006;27:295–308. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00318.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshioka J, et al. Thioredoxin-interacting protein controls cardiac hypertrophy through regulation of thioredoxin activity. Circulation. 2004;109:2581–2586. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129771.32215.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Connell TD, et al. The α(1A/C)- and α(1B)-adrenergic receptors are required for physiological cardiac hypertrophy in the double-knockout mouse. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:1783–1791. doi: 10.1172/JCI16100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goring HH, et al. Discovery of expression QTLs using large-scale transcriptional profiling in human lymphocytes. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1208–1216. doi: 10.1038/ng2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook SA, Novikov MS, Ahn Y, Matsui T, Rosenzweig A. A20 is dynamically regulated in the heart and inhibits the hypertrophic response. Circulation. 2003;108:664–667. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000086978.95976.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oka T, et al. Genetic manipulation of periostin expression reveals a role in cardiac hypertrophy and ventricular remodeling. Circ. Res. 2007;101:313–321. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.149047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berk BC, Fujiwara K, Lehoux S. ECM remodeling in hypertensive heart disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:568–575. doi: 10.1172/JCI31044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheitlin MD, et al. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2003;16:1091–1110. doi: 10.1016/S0894-7317(03)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birney E, et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tasheva ES, et al. Mimecan/osteoglycin-deficient mice have collagen fibril abnormalities. Mol. Vis. 2002;8:407–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirota H, et al. Loss of a gp130 cardiac muscle cell survival pathway is a critical event in the onset of heart failure during biomechanical stress. Cell. 1999;97:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80729-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schroen B, et al. Lysosomal integral membrane protein 2 is a novel component of the cardiac intercalated disc and vital for load-induced cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1227–1235. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tasheva ES, Corpuz LM, Funderburgh JL, Conrad GW. Differential splicing and alternative polyadenylation generate multiple mimecan mRNA transcripts. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:32551–32556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang GS, Cooper TA. Splicing in disease: disruption of the splicing code and the decoding machinery. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:749–761. doi: 10.1038/nrg2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kresse H, Schonherr E. Proteoglycans of the extracellular matrix and growth control. J. Cell. Physiol. 2001;189:266–274. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang D, et al. TAK1 is activated in the myocardium after pressure overload and is sufficient to provoke heart failure in transgenic mice. Nat. Med. 2000;6:556–563. doi: 10.1038/75037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hashimoto J, Imai Y, O'Rourke MF. Indices of pulse wave analysis are better predictors of left ventricular mass reduction than cuff pressure. Am. J. Hypertens. 2007;20:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook SA, Sugden PH, Clerk A. Regulation of bcl-2 family proteins during development and in response to oxidative stress in cardiac myocytes: association with changes in mitochondrial membrane potential. Circ. Res. 1999;85:940–949. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.10.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schroen B, et al. Thrombospondin-2 is essential for myocardial matrix integrity: increased expression identifies failure-prone cardiac hypertrophy. Circ. Res. 2004;95:515–522. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141019.20332.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caruthers SD, et al. Practical value of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for clinical quantification of aortic valve stenosis: comparison with echocardiography. Circulation. 2003;108:2236–2243. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000095268.47282.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]