Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the potential effect of computer support on general practitioners' management of familial breast and ovarian cancer, and to compare the effectiveness of two different types of computer program.

Design

Crossover experiment with balanced block design.

Participants

Of a random sample of 100 general practitioners from Buckinghamshire who were invited, 41 agreed to participate. From these, 36 were selected for a fully balanced study.

Interventions

Doctors managed 18 simulated cases: 6 with computerised decision support system Risk Assessment in Genetics (RAGs), 6 with Cyrillic (an established pedigree drawing program designed for clinical geneticists), and 6 with pen and paper.

Main outcome measures

Number of appropriate management decisions made (maximum 6), mean time taken to reach a decision, number of pedigrees accurately drawn (maximum 6). Secondary measures were method of support preferred for particular aspects of managing family histories of cancer; importance of specific information on cancer genetics that might be provided by an “ideal computer program.”

Results

RAGs resulted in significantly more appropriate management decisions (median 6) than either Cyrillic (median 3) or pen and paper (median 3); median difference between RAGs and Cyrillic 2.5 (95% confidence interval 2.0 to 3.0; P<0.0001). RAGs also resulted in significantly more accurate pedigrees (median 5) than both Cyrillic (median 3.5) and pen and paper (median 2); median difference between RAGs and Cyrillic 1.5 (1.0 to 2.0; P<0.0001). The time taken to use RAGs (median 178 seconds) was 51 seconds longer per case (95% confidence interval 36 to 65; P<0.0001) than pen and paper (median 124 seconds) but was less than Cyrillic (median 203 seconds; difference 23. (5 to 43; P=0.02)). 33 doctors (92% (78% to 98%)) preferred using RAGs overall. The most important elements of an “ideal computer program” for genetic advice in primary care were referral advice, the capacity to create pedigrees, and provision of evidence and explanations to support advice.

Conclusions

RAGs could enable general practitioners to be more effective gatekeepers to genetics services, empowering them to reassure the majority of patients with a family history of breast and ovarian cancer who are not at increased genetic risk.

Introduction

Continuing advances in the molecular genetics of common diseases mean that primary care will play an increasing role in providing genetic advice.1 The recent increase in referrals of people at low risk of inherited cancer, particularly breast cancer, to genetics clinics suggests that general practitioners need a range of new skills to be effective gatekeepers.2 The ability to obtain and interpret family history information accurately is fundamental to these new skills.3 Computers could support primary care in this new task by simplifying pedigree drawing and implementing management guidelines.4,5

We previously reported a qualitative evaluation of Risk Assessment in Genetics (RAGs), a computer program to support the assessment of familial breast and ovarian cancer in primary care.6 The results of this study informed the development of the software used in the current study so that it was more appropriate for primary care. The aim of the current study was to compare two different types of computer support—RAGs and Cyrillic (an established pedigree drawing program designed for clinical geneticists)—with traditional pen and paper methods in the recording and interpretation of family histories of cancer.

Participants and methods

Participants

We wrote to a random sample of 100 Buckinghamshire general practitioners inviting them to participate in the study. After one mailing, 41 doctors agreed to join the study, of whom the first 36 respondents were chosen. The participants were paid £80 for the two hours required to perform the study.

Computer support

RAGs was developed in a collaboration between JE and the ICRF Advanced Computation Laboratory. Pedigrees are generated by first entering information about the proband and then adding data about relatives by clicking on individual icons in the family tree. The program uses PROforma technology7 to categorise risk of breast and ovarian cancer. The program implements detailed referral guidelines that are based on the Claus model8 and then suggests appropriate management. The Claus model is a mathematical model that predicts risk of breast cancer and is based on data from a case-control study of 4730 breast cancer cases. Cyrillic draws pedigrees and assesses risk of breast cancer, also using the Claus model, and calculates the numerical risk of carrying a mutation that predisposes to breast cancer and the cumulative risks of developing breast cancer.9 Cyrillic was originally designed for use by clinical geneticists. This study used a modified version of Cyrillic that takes the user through a series of question and answer boxes to construct the pedigree.

Simulated cases and recommended management

We developed 18 hypothetical cases, designed to cover a range of risk levels, based on the types of referral received by the Oxford genetics clinic in the previous year. An expert panel comprising a general practitioner and a health services researcher with knowledge of cancer genetics and a clinical cancer geneticist agreed by consensus the appropriate management for each case. Management decisions were based on the strategy proposed at a UK national consensus meeting: low risk women are managed in primary care, moderate risk women at a breast unit, and high risk women at a genetics clinic.10 The panel decided that there were six high risk, five moderate risk, and seven low risk cases. The cases were randomly allocated into three sets of six.

Study design

Each doctor was asked to manage all 18 cases, six with each method of support (RAGs, Cyrillic, and pen and paper). We used a balanced block design. To avoid any learning effect, the order in which the methods and case sets were presented was completely balanced among the 36 doctors. We also ensured that each method was used equally often with each case set (see extra table on the BMJ website). For each case, the doctor was asked to create a pedigree and decide on management using the principle of triaging the patient as low, moderate, or high risk. The two computer programs were set up on a laptop computer in the doctor's consulting room. The participants were familiarised with each program with one or two test cases before conducting the study. When the doctors used pen and paper to manage cases they were allowed to use any paper referral guidelines that were available to them. Although all Buckinghamshire general practitioners had been mailed management guidelines in 1997, only three of the doctors in our study had access to these in their consulting room.

Outcome measures

The principal outcome measures were the number of appropriate management decisions made for each set of six cases, the mean time taken to reach a decision, and the number of pedigrees accurately drawn. A pedigree was considered correct only if it used standard symbols and lines and contained information about the age of the proband, type of cancer, and age of onset for each affected relative. After managing all 18 cases, the participants completed a questionnaire asking them to rate, on a five point Likert scale, the three methods for particular aspects of managing family histories of cancer, and the importance of specific functions or information on cancer genetics that might be provided by an “ideal computer program.”

Sample size and statistical analysis

From the results of a pilot study, we calculated that we required 25 doctors to detect a mean difference of 1.5 in management scores (SD 1.6) between RAGs and Cyrillic with 90% power and two sided α=0.05. The sample size was increased to 36 to make a completely balanced study design. We used Friedman's two way analysis of variance to compare effects overall for each outcome. To compare different pairs of support for each outcome, we used Wilcoxon's matched pairs signed rank test. We used SPSS for Windows (version 8) for the Friedman's and Wilcoxon's tests, and the confidence interval analysis program (CIA)11 to calculate differences in medians and associated confidence intervals.

Results

Characteristics of participants

The characteristics of the participants were similar to those who chose not to enter the study. Of the 36 doctors selected to participate, 69% were men, 61% held the MRCGP, and their median time since qualification was 21 (range 7-36) years. Of the 59 non-participants, 61% were men, 56% held the MRCGP, and their median time since qualification was 21 (range 8-39) years.

Outcomes

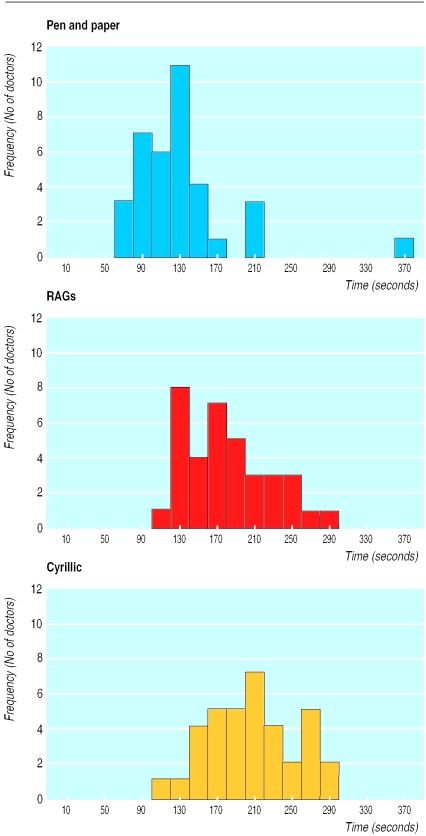

Table 1 shows the median outcomes for the three different types of support. RAGs resulted in significantly more appropriate management decisions and accurate pedigrees than both Cyrillic and pen and paper. The median difference in management scores between RAGs (median 6) and pen and paper (median 3) was 3 (95% confidence interval 2.5 to 3.5; P<0.0001) and between RAGs and Cyrillic (median 3) was 2.5 (2.0 to 3.0; P<0.0001). Pedigrees were more accurately drawn with RAGs than with pen and paper (median scores 5 v 2; difference 3 (2.5 to 3.5); P<0.0001) or with Cyrillic (5.0 v 3.5; difference 1.5 (1.0 to 2.0); P<0.0001). Cyrillic produced significantly more accurate pedigrees than pen and paper (median difference 1.5 (1.0 to 2.0); P<0.0001), but there was no difference in management scores between these two types of support (median difference 0.5 (0 to 1.5); P=0.08). It took significantly longer to reach a decision with RAGs than with pen and paper (median 178 seconds v 124 seconds; difference 51 (37 to 66); P<0.0001) but significantly less time than with Cyrillic (178 v 203 seconds; difference 23 (5 to 43); P=0.02). The figure shows the distributions of time taken with each method.

Table 1.

Median (range) outcome measures for 36 doctors managing family histories of cancer using three different methods of support—traditional pen and paper and computer programs RAGs and Cyrillic

| Outcome | RAGs | Cyrillic | Pen and paper | P value for difference* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct referrals (maximum 6) | 6.0 (4-6) | 3.0 (0-6) | 3.0 (0-5) | <0.0001 |

| Correct pedigrees (maximum 6) | 5.0 (2-6) | 3.5 (0-6) | 2.0 (0-5) | <0.0001 |

| Time to complete each case (seconds) | 178 (109-287) | 203 (120-299) | 124 (73-372) | <0.0001 |

Friedman's two way analysis of variance.

Table 2 shows which of the three methods of support the participants preferred for particular elements of managing patients with a family history of cancer. RAGs was preferred for all elements—drawing and understanding the pedigree, ease and speed of use, and information provided—and 92% (95% confidence interval 78% to 98%) of the doctors preferred RAGs overall.

Table 2.

Preference of 36 doctors for different methods of support—traditional pen and paper and computer programs RAGs and Cyrillic—for specific elements of managing family histories of cancer. Values are numbers (percentages)

| Preferred method

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| RAGs | Cyrillic | Pen and paper | |

| Overall | 33 (92) | 2 (6) | 1 (3) |

| Pedigree drawing | 27 (75) | 3 (8) | 6 (17) |

| Pedigree comprehension* | 28 (82) | 3 (9) | 3 (9) |

| Ease of use | 31 (86) | 3 (8) | 2 (6) |

| Speed | 19 (53) | 7 (19) | 10 (28) |

| Information | 31 (86) | 5 (14) | 0 |

Two doctors did not respond for this question.

Table 3 shows the importance the doctors placed on having specific functions or information provided by an “ideal computer program” for advice about cancer genetics. Providing accurate referral advice was most important, followed by the capacity to draw family trees and the facility for individualised explanations and evidence to support the advice provided.

Table 3.

Level of importance assigned by 36 doctors to specific functions and items of information in an ideal computer program for genetic advice. Values are numbers (percentages)

| Function or information | Level of importance*

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Most (scores 4-5) | Medium (score 3) | Least (scores 1-2) | |

| Referral advice | 34 (94) | 2 (6) | 0 |

| Individualised explanations for advice | 28 (78) | 7 (19) | 1 (3) |

| Evidence to support advice | 28 (78) | 7 (19) | 1 (3) |

| Pedigree drawing | 26 (72) | 9 (25) | 1 (3) |

| Use of HRT in context of family history of breast cancer | 20 (56) | 12 (33) | 4 (11) |

| Information on genetic testing | 19 (53) | 11 (31) | 6 (17) |

| Numerical risk calculation | 12 (33) | 15 (42) | 9 (25) |

| Information on genetics clinic (such as waiting times) | 14 (39) | 9 (25) | 13 (36) |

Assigned on a 5 point Likert scale.

HRT=hormone replacement therapy.

Discussion

In this study of 36 general practitioners, we have shown the potential for computer support, and in particular RAGs, to improve the management of patients with a family history of breast and ovarian cancer in primary care. RAGs led to more appropriate management decisions and more accurate pedigrees at the expense of an additional median 51 seconds per case.

Limitations of study

After a single letter of invitation to participate, only 41 of 100 doctors agreed, of whom only 36 entered the study for a fully balanced design. Our sample may therefore be unrepresentative of British general practitioners. However, the doctors studied were no different in their basic characteristics from those who chose not to participate. Thirteen of the doctors in the study were unfamiliar with a Windows interface, suggesting that our sample was not a self selected group of highly computer literate practitioners. Furthermore, by offering payment for participation, we were more likely to recruit a representative sample of general practitioners.12

This study used simulated paper cases to assess the potential effect of computer support on management of people with a family history of cancer. The results cannot be generalised to predict the actual effect of computer support on referrals to secondary care for familial cancer. Because the number of referrals made by an individual general practitioner is small, a large randomised controlled trial would be required to quantify these effects in real life. Until stronger evidence exists to support interventions for people with a genetic risk of breast and ovarian cancer, we believe it would be inappropriate to conduct a trial of computer support that involves actively identifying individuals with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer.

Comparison with other studies and implications for practice

This study confirms the ability of computer decision support systems to improve physicians' performance13 at the possible expense of longer consultations.14 It also shows the difficulty general practitioners have in appropriately managing patients with a family history of cancer. This is in keeping with a study of general practitioners in south east Scotland, who showed a tendency to overestimate risk of cancer on the basis of family history and who expressed a desire for computer aided risk assessment in this field.15

RAGs was significantly better than Cyrillic in all three outcomes. This is perhaps not surprising given that it was designed specifically for general practice, whereas Cyrillic was originally designed for clinical geneticists, for whom pedigrees and numerical risks have more meaning. The aim of our study was to compare three different levels of support—standard care, numerical risk assessment, and specific management advice—rather than comparing standard care with two computer programs that provide the same information in different formats. Cyrillic is the only commercially available pedigree drawing program that performs risk assessment for breast cancer. We therefore compared existing technology with a newly developed technology.

This study shows the importance of developing medical software to meet the specific needs of its intended users, and this may require considerable variation in the format and type of information provided.16 It supports the combination of qualitative and quantitative methods, with the early involvement of potential users, to develop medical software that is appropriate for a specific clinical context.17

There are several reasons why RAGs might be more appropriate for general practitioners than Cyrillic. RAGs has a simpler interface with fewer potential actions or choices for the user. This seemed to be particularly important for the less computer literate doctors. The method of generating a pedigree was more flexible and allowed mistakes to be corrected more easily. In particular, the graphical presentation of the family tree, with labels explaining the nature of the relationship with the proband, assisted doctors who were less familiar with pedigrees. Cyrillic assumes that users understand the nature of family relationships such as cousins and great aunts, but this knowledge was not universal in our sample of doctors. RAGs prompts users to enter a minimum dataset required for risk assessment, thus avoiding potential incorrect estimations of risk because of inadequate data. Most importantly, however, RAGs provides management advice, whereas Cyrillic gives only a numerical risk assessment. With the exception of extreme values, the numerical risks alone were insufficient to aid general practitioners in their decision making. The doctors in this study rarely ignored the advice provided by RAGs, and the main reason for incorrect management with RAGs was an error in entering data.

Molecular genetics is likely to have an increasing influence on the practice of clinical medicine.18 Primary care is poorly prepared for this new era, and general practitioners will need to acquire new skills and knowledge to play an important role in the delivery of genetics services.19,20 Guidelines have been suggested as a method of bridging this knowledge gap, but, as we found in this study, paper guidelines are rarely accessible in general practice when required.21

In the United Kingdom few general practitioners currently use their computer as a source of information during consultations.22 This reflects the limitations of existing hardware and software, which present a substantial barrier to integration of decision support into clinical practice.4 Field trials are needed to assess the real impact of computer support for cancer genetics in primary care and patients' responses to using such software in the consultation.23 This study shows that RAGs could enable general practitioners to be more effective gatekeepers to genetics services and empower them to reassure the majority of their patients with a family history of breast and ovarian cancer who are not at increased genetic risk.

What is already known on this topic

General practitioners will play an increasing role in providing genetic advice but currently lack the skills to be effective gatekeepers to genetics services

Computers have been proposed as a way of supporting primary care in this new task

What this study adds

RAGs, a program designed specifically for primary care, resulted in more appropriate management decisions and more accurate pedigrees than both Cyrillic, an established pedigree drawing program designed for clinical geneticists, and traditional methods but took an extra 51 seconds per case

For general practitioners, RAGs was superior to Cyrillic because it provided more relevant information and had a simpler interface

Computer support could empower general practitioners to reassure patients with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer who are not at increased genetic risk and avoid unnecessary referrals

Supplementary Material

Figure.

Distribution of time taken by 36 doctors to reach a management decision about cases of family history of cancer using three different methods of support—traditional pen and paper and computer programs RAGs and Cyrillic

Acknowledgments

We thank the general practitioners who took part in this study, and Peter Rose, Anneke Lucassen, and Eila Watson for forming the expert panel.

Access to software

Cyrillic is available commercially from Cherwell Scientific Publishing (www.cherwell.com). Experience from from the evaluation of RAGs and Cyrillic is being applied to the development of an online genetic risk assessment service that will be available shortly at www.familygenetix.com. Requests for copies of the version of RAGs used in this study should be made to Professor John Fox (jfox@acl.icnet.uk).

Footnotes

Funding: The Cancer Research Campaign funded this study. JE and JA are funded by the Cancer Research Campaign. RW, MM, PY, and JF are funded by the Imperial Cancer Research Fund. AC and DG are funded by the Economic and Social Research Council and the Imperial Cancer Research Fund.

Competing interests: CC has been paid as a consultant and has been reimbursed for attending conferences by Cherwell Scientific Publishing, which produces Cyrillic. After completion of this study, JE has been paid as a consultant by Cherwell Scientific Publishing.

An extra table detailing the study's balanced block design appear on the BMJ website

References

- 1.Gill M, Richards T. Meeting the challenge of genetic advance. BMJ. 1998;316:570. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7131.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinmonth AL, Reinhard J, Bobrow M, Pauker S. The new genetics: implications for clinical services in Britain and the United States. BMJ. 1998;316:767–770. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7133.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins FS. Preparing health professionals for the genetic revolution. JAMA. 1997;278:1285–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emery J. Computer support for genetic advice in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;1999:572–575. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kay C, editor. Genetics in primary care—A report from the North West England Faculty Genetics Group. London: Royal College of General Practitioners; 1998. . (Occasional paper 77.) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emery J, Walton R, Coulson A, Glasspool D, Ziebland S, Fox J. A qualitative evaluation of computer support for recording and interpreting family histories of breast and ovarian cancer in primary care (RAGs) using simulated cases. BMJ. 1999;319:32–36. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7201.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox J, Thomson R. Decision support and disease management: a logic engineering approach. IEEE Trans Information Technol Biomed. 1998;2:217–228. doi: 10.1109/4233.737577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Claus EB, Schildkraut JM, Thompson WD, Risch NJ. The genetic attributable risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Cancer. 1996;77:2318–2324. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960601)77:11<2318::AID-CNCR21>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cyrillic version 2.1. Oxford: Cherwell Scientific Publishing; 1997. www.cherwell.com . ( www.cherwell.com.) .) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Report of the consensus meeting on the management of women with a family history of breast cancer. London: Wellcome Trust; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Confidence interval analysis. London: BMJ Publishing; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foy R, Parry J, McAvoy B. Clinical trials in primary care: targeted payments for trials might help improve recruitment and quality. BMJ. 1998;317:1168–1169. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7167.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunt DL, Haynes RB, Hanna SE, Smith K. Effects of computer-based clinical decision support systems on physician performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 1998;280:1339–1346. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.15.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan F, Mitchell E. Has general practitioner computing made a difference to patient care? A systematic review of published reports. BMJ. 1995;311:848–852. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7009.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fry A, Campbell H, Gudmundsdottir H, Rush R, Porteous M, Gorman D, et al. General practitioners' views on their role in cancer genetics and current practice. Fam Pract. 1999;16:468–474. doi: 10.1093/fampra/16.5.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wyatt JC, Wright P. Design should help use of patients' data. Lancet. 1998;352:1375–1378. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman CP, Wyatt J. Evaluation methods in medical informatics. New York: Springer; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell J. The new genetics in clinical practice. BMJ. 1998;316:618–620. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7131.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emery J, Watson E, Rose P, Andermann A. A systematic review of the literature exploring the role of primary care in genetic services. Fam Pract. 1999;16:426–445. doi: 10.1093/fampra/16.4.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayflick S, Eiff M. Role of primary care providers in the delivery of genetics services. Community Genetics. 1998;1:18–22. doi: 10.1159/000016131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabana M, Rand C, Powe N, Wu A, Wilson M, Abboud P, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? JAMA. 1999;282:1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watkins C, Harvey I, Langley C, Faulkner A, Gray S. General practitioners' use of computers during the consultation. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49:381–383. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wyatt J, Spiegelhalter D. Evaluating medical expert systems: what to test and how? Med Inf. 1990;15:205–217. doi: 10.3109/14639239009025268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.