Abstract

X-Adrenoleukodystrophy (X-ALD) is a peroxisomal disorder characterized by accumulation of very long chain (VLC) fatty acids, which induces alterations in cellular redox and induction of inflammatory disease, both of which are reported to play a role in pathogenesis of the severe form of the disease (childhood ALD). Here we report on the status of oxidative stress (NADPH oxidase activity) and inflammatory mediators in a X-ALD lymphoblast cell line under non-stimulated conditions. X-ALD lymphoblasts contain near 7 fold higher levels of the C26:0 fatty acid, as compared to controls; levels that were down regulated by treatment with Sodium Phenylacetate (NaPA), lovastatin or combination of both drugs. In addition, free radical synthesis was elevated in X-ALD lymphoblasts, and protein levels of the NADPH oxidase gp91PHOX membrane subunit were significantly upregulated, but no changes were observed in the p47PHOX and p67PHOX cytoplasmic subunits. Unexpectedly, there was no increase in gp91PHOX mRNA levels in X-ALD lymphoblasts. Furthermore, X-ALD lymphoblasts produced higher levels of nitric oxide (NO) and cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β); and treatment with NaPA, or lovastatin decreased the synthesis of NO. Our data indicates that X-ALD lymphoblasts are significantly affected by the accumulation of VLC fatty acids, which in turn induces changes in the cell membrane properties/functions that may play a role in the development/progression of the pathogenesis of X-ALD disease.

Keywords: X-Adrenoleukodystrophy, NADPH oxidase, lymphoblasts, oxidative stress, nitric oxide, cytokines, TNFα, neuroinflammation, very long chain fatty acids, peroxisomal disorder

Introduction

X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (X-ALD) is a childhood genetic peroxisomal disorder characterized by altered metabolism of very long chain (VLC) fatty acids which take place in peroxisomes, through a set of β-oxidative reactions (1). The genetic defect is impaired expression of the adrenoleukodystrophy protein (ALDP), a protein belonging to the ABC family of transporters (2), and an integral membrane protein of peroxisome (3, 4). Although its function is still unknown at present, experimental evidence indicates that it is involved in the metabolism of VLC fatty acids in peroxisomes (5, 6). Clinically, the disease can develop as a severe form (cerebral form) which progresses very rapidly, with fatal consequences; and a mild form (adrenomyeloneuropathy), that affect axonal tracts of the spinal cord, inducing progressive physical disabilities towards adulthood (7). Both disease phenotypes can be originated by identical genetic mutation, indicating the participation of a modifier gene and/or environmental factors (8). The cerebral form begins with the accumulation of VLC fatty acids in peripheral and neural tissue (metabolic stage), then due to unknown event, the disease progresses to an inflammatory process characterized by activation of microglia, synthesis of nitric oxide, cytokines, chemokines and further infiltration of macrophages and T regulatory cells, finally inducing oligodendrocyte cell death (inflammatory stage) (7, 9-11). Interestingly, the findings that the animal models of X-ALD (ALDP knockout mouse) do not express a clear disease phenotype -although they accumulate VLC fatty acids in the central nervous system (12-14)- or do not show evidence of oxidative stress in nervous tissue as in X-ALD patients samples (15, 16), suggest that induction of an oxidative imbalance in X-ALD patients may play a role in the development/progression of the disease.

NADPH oxidases are a group of plasma membrane associated enzymes, of which the most studied is the leukocyte NADPH oxidase, found in professional phagocytes and B lymphocytes (17). The oxidase catalyzes the production of superoxide (O2-) which is utilize for the production of reactive oxidants that phagocytes use to kill microorganisms (18). The enzyme is a heterodimer consisting of one of each of five subunits, three of which are cytoplasmic (p40PHOX, p47PHOX, p67PHOX) and two of which are membrane anchored (p22PHOX, gp91PHOX) (17). NADPH oxidases have become the focus of attention due to the discovery that they may play a role in the development/progression of inflammation in disorders affecting the CNS (19).

Studies using X-ALD patient derived cells or mutant cells (C6) exposed to VLC fatty acids indicate that these cells have altered membrane signaling, and that they become prone to over-respond when stimulated. For example, peripheral blood mononuclear cells from X-ALD patients, when stimulated with bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), produce increased levels of cytokines typical of a Th1 cell response (IL-12, TNFα) as compared to cells from control patients (20, 21); skin fibroblasts derived from peroxisomal metabolic disorder patients (including X-ALD) have an increased basal as well as IL-1β stimulated arachidonic acid metabolism (22); and C6 cells enriched in the VLC fatty acid hexacosanoic acid (C26:0) and stimulated with oxidative stressors (LPS, oxidized LDL) produce higher levels of nitric oxide and superoxide products as compared to those by untreated cells (23). These reports support the hypothesis that accumulation of VLC fatty acids alters the plasma membrane properties (24, 25), and hence cell signaling functions in those cells (26).

Free radicals play a significant role in the development and progression of the pathobiology of most neurodegenerative diseases, including X-ALD (15). Indeed, studies performed with plasma, red blood cells, skin fibroblasts and nervous tissues from X-ALD patients, reported significant evidence of an oxidative imbalance in those samples (15, 16). However, the source of such oxidative imbalance remains unknown, as it is not known if it is a contributing cause and/or an effect of the development/progression of X-ALD disease pathology. Unfortunately, animal models of X-ALD express the mild form of the human disease, adrenomyeloneuropathy (AMN) (27), and signs of oxidative stress in the spinal cord (28). Consequently, study of the oxidative imbalance contribution to the development/progression of the X-ALD disease is limited, at present, to patient derived tissues only. Therefore, to gain an insight into what might be potential sources contributing to the observed oxidative stress in X-ALD patients; we studied the activity and expression of NADPH oxidase in control and X-ALD patient derived lymphoblasts. Here we report that X-ALD lymphoblasts are prone to synthesize NADPH oxidase-dependent free radicals, nitric oxide and cytokines as compared to control cells, with some of these products being susceptible to pharmacological treatment. These events are probably a consequence of the accumulation of VLC fatty acids in the cell membrane, which result in alterations of its properties and functions.

Methods Section

Materials

RPMI 1640 (containing l-Glutamine) was from Cellgro (Mediatech, Herndon, VA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from Atlanta Biologicals (Norcross, GA); Trypsin and Hank’s balanced solution (HBSS) were from Gibco (Grand Island, NY). Antibodies against gp91PHOX, p47PHOX and p67PHOX were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); anti-ALDP was from Chemicon Inc. (Temecula, CA); and anti-PMP70 and anti-ALDRP were custom made against C-terminal residues 644-659 of the human protein and C-terminal residues 722-741 of the mouse protein respectively. Diphenylene iodonium (DPI), bovine serum albumin (BSA), Imidazole, Triton X-100, Tween-20 and β-mercaptoethanol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). All chemicals and reagents used were of analytical grade or of the highest purity commercially available.

Methods

Cell culture

Human B-lymphoblasts derived from normal (control; GM03798), X-ALD (hemizygote; GM04673 and GM13496), and carrier (heterozygote; GM04674) patients were obtained from the NIGMS Human Genetic Mutant Cell Repository at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research (ccr.coriell.org/). The lymphoblasts were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS and antibiotic/antimicotic, at a cell density of less than 2 × 106 cells/ml. Most of the studies were performed with the X-ALD lymphoblast cell line GM04673 derived from a patient with positive family history of X-ALD (11-year-old male whose cultured fibroblasts presented elevated C26:0 fatty acids. Clinically, he had adrenal insufficiency, progressive white matter disease and progressively deteriorating intellectual and motor function). Lymphoblasts GM13496 were from a 9 year old boy that presented elevated very long chain (C26:0) fatty acids levels. Heterozygote lymphoblast (GM04674) was from a 30 year old female with a family history of X-ALD (ccr.coriell.org/). Normal (control) cells (GM03798) were from an apparently healthy 10-year-old male.

Measurement of very long chain (VLC) fatty acids

Fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) was prepared as described previously (29). Briefly, lymphoblasts were suspended in HBSS, and disrupted by sonication (10 sec at 8-9 watts output power in a VirSonic 100, VirTis, Gardiner, NY). An aliquot of this solution was transferred to a glass tube and an internal standard (heptacosanoic acid, 5 μg) was added, and the lipids were extracted by Folch partition. Fatty acids were trans-esterified with acetyl chloride in the presence of methanol and benzene (4:1) for 2 h at 100°C. The solution was cooled down to room temperature followed by addition of 5 ml 6% potassium carbonate solution at ice-cooled temperature. Isolation and purification of FAME were carried out as described elsewhere (29). Purified FAME, were suspended in chloroform and analyzed by a gas chromatography (GC-15A, Shimadzu Corporation, Durham, NC).

Preparation of total and carbonate membranes

Cells were harvested with sucrose buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 3 mM imidazole buffer, pH 7.4), and subjected to sonication (10 sec at 8-9 watts output power). The homogenate was centrifuged at 2,500 rpm for 5 min to remove unbroken cells. To isolate total membranes, control and ALD homogenates were centrifuged at 50,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C using a TLA-100.2 rotor (Beckman-Coulter), and the pellets were washed once with cold water and dissolved in an equal volume of electrophoresis sample loading buffer (100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 6.8), 250 mM sucrose, 4% (w/v) SDS, 0.01% (w/v) bromophenol blue and 5 % (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol). To isolate carbonate membranes (membrane sheets containing integral membrane proteins), equal protein amount from control and X-ALD cell homogenates were diluted with an ice-cold solution of 0.1 M sodium carbonate (pH 11.5) containing 30 mM iodoacetamide. After 30 minutes of incubation at 4°C, carbonate membranes were sedimented by centrifugation at 35,000 rpm for 1 hour in a 70Ti rotor (Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton, CA). The sedimented membranes were washed twice with cold water, lyophilized and stored at -70°C until use.

Western blot analysis

Equal amount of protein were heated in sample loading buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE (4–20% Tris-HCl Criterion gradient Gel; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA)(6). Proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad), blocked with 5% nonfat milk (Bio-Rad) in Tween-20-Tris-buffered saline (TTBS; 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6), 137 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20) for 1 h, and incubated overnight with specific antibodies at 4°C in 5% nonfat milk-TTBS. Blots were washed and incubated 90 min with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Signals were detected with Lumi-Phos WB chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce) and exposure to CL-Xposure films (Pierce).

Real-time Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was purified from lymphoblasts using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized from RNA by using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), a master mixture was prepared using the SYBRGreen PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and dispensed into microplate wells together with template and primers. Primers used were (SuperArray, Frederick, MD): gp91PHOX (CYBB, cat # PPH10407A); p67PHOX (NCF2, cat # PPH07033A); and p47PHOX (NCF1, cat # PPH07085E). Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: activation of DNA polymerase at 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of amplification at 95°C for 15 sec, and 60°C for 60 sec. The expression of target gene was normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, cat # PPH00150E). All samples were run in triplicate.

Measurement of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Intracellular ROS was determined using the membrane permeable fluorescent dye 6-carboxy 2’, 7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein (H2DCFDA; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Cell (1 × 106 cells/ml) were pre-incubated in the presence or absence of the NADPH oxidase inhibitor DPI (10 μM) for 30 min and then exposed to 10 μM H2DCFDA in PBS for 30 min. Changes in fluorescence was determined by reading after excitation at 485 nm and emission 530 nm using a SoftMax Pro spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Assay for nitric oxide (NO) synthesis

Synthesis of NO was determined in cell culture supernatants by measuring nitrite, a stable product of the reaction of NO with molecular oxygen. Briefly, 400 μl of culture supernatant was reacted with 200 μl of Griess reagent (30) for 15 min at room temperature, and the color developed was measured at 570 nm using a SpectraMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Cytokine Analysis

Lymphoblasts were cultured in serum-free RPMI for 72 hours. Cell-free supernatants were collected and TNF-α and IL-1β levels were determined by ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Drugs treatments

Lymphoblasts were incubated in complete medium containing either 1 μM lovastatin or 1 mM sodium phenylacetate (NaPA), during 7 days, with daily replacement of media-containing drugs. At the end of the treatment, VLC fatty acids levels were determined in harvested cells and nitrite was determined in the cell culture supernatants.

Determination of protein content

Protein determination was performed using the method of Bradford (31) (Bio-Rad reagent).

Statistics

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for n number of experiments. Statistical differences were analyzed using Student’s t-test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant difference.

Results

Molecular and biochemical alterations in X-ALD lymphoblasts

First, we characterized control (GM03798), X-ALD (ALD1: GM04673; ALD2: GM13496) and heterozygote (GM04674) lymphoblast cell in terms of the expression of the peroxisomal transporters adrenoleukodystrophy protein (ALDP, ABCD1), the gene product defective in X-ALD, and the peroxisomal membrane protein of 70kDa (PMP70; ABCD3). Western blots using antibodies against ALDP and PMP70 were performed on carbonate membranes (membrane preparation containing integral membrane proteins) obtained from control, X-ALD and heterozygote cultured lymphoblasts. The analysis indicated that ALDP was not detectable in ALD1 and barely detectable in ALD2, when compared with the levels expressed in control and heterozygote (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, screening of PMP70 did not show an appreciable difference between the signals obtained from the same four cell samples analyzed. Further studies were performed with ALD1 lymphoblasts, from a patient with positive family history of X-ALD disease (ccr.coriell.org/). Gas chromatography analysis of the levels of C26:0 fatty acids determined in whole cell homogenates of control and X-ALD (ALD1) lymphoblasts indicated a significant accumulation of C26:0 in X-ALD lymphoblasts (8.37 ± 0.3 fold; p < 0.0001), a biochemical hallmark of X-ALD disease (Fig. 1B). This observation was supported by a significant increase in the C26:0/C22:0 ratios in X-ALD lymphoblasts (Fig. 1C). Next, we tested two drugs (sodium phenylacetate (NaPA) and lovastatin) which in previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated to be of benefit in lowering the levels of VLC fatty acids in plasma of X-ALD patients and in X-ALD fibroblasts in culture (32-34). Treatment of X-ALD lymphoblasts with NaPA, lovastatin or a combination of both drastically reduced the elevated levels of C26:0 after 2 days (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that VLC fatty acid metabolism in X-ALD lymphoblasts is susceptible to NaPA and lovastatin treatment as reported previously on X-ALD fibroblasts (33).

Fig. 1.

Molecular and biochemical alterations in an X-ALD lymphoblast cell lines and pharmacological restoration of very long chain fatty acids levels. Human B-lymphoblasts derived from a healthy control (CTL: GM03798), cerebral X-ALD patients (ALD1: GM04673; ALD2: GM13496), and heterozygote (HZ: GM 03798) were cultured and used to analyze protein levels of the peroxisomal integral membrane proteins transporters ALDP (ABCD1) and PMP70 (ABCD3) (A); cellular levels of very long chain fatty acids (C26:0)(B, C), and the effect of lovastatin and NaPA on C26:0 levels (D). Protein levels of the peroxisomal transporters were analyzed by Western blot in membranes fractions obtained by carbonate treatment (membrane preparation containing integral membrane proteins), as indicated in Methods section. Lipid analysis was performed by gas chromatography of the total fatty acids methyl ester of a organic extract of whole cell and C26:0 values are expressed as percent of total fatty acids (B), and the ratio of C26:0 to C22:0 (C). Western blots are representative of three different experiments. Data represent the average ± SD of n = 3 experiments done in duplicated. (B, C) ***: p < 0.0001; (D) ***: p < 0.0001 vs. untreated X-ALD lymphoblasts.

NADPH oxidase dependent-synthesis of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in non-stimulated X-ALD lymphoblasts

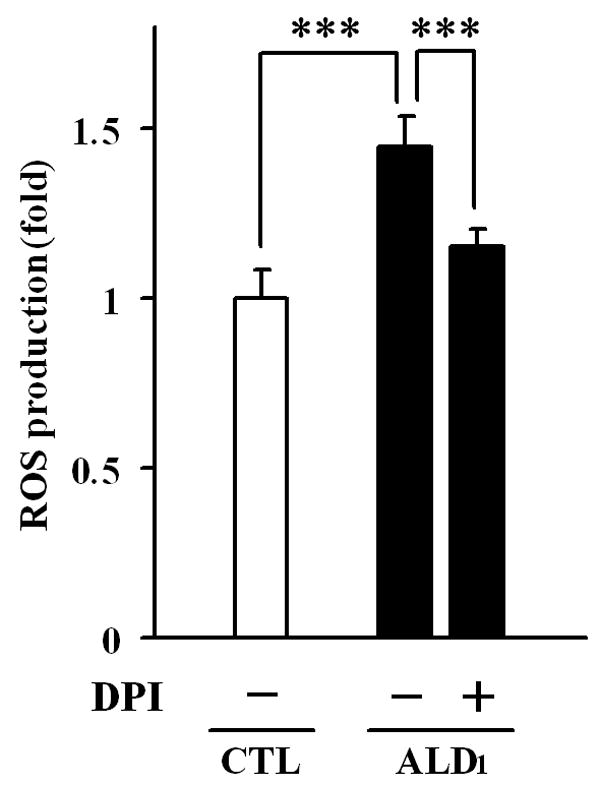

Based on published reports which indicate evidence of oxidative stress in X-ALD fibroblasts (16) and induction of free radicals in cell culture exposed to VLC fatty acids (23), we investigated whether X-ALD lymphoblasts could be prone to higher ROS synthesis under basal (non-stimulated) conditions, using the permeable fluorescent probe H2DCFDA. Determination of ROS levels in control and X-ALD lymphoblasts in culture indicated that X-ALD lymphoblasts synthesized significantly higher levels of free radicals as compared to control (1.45 ± 0.08 folds, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). To establish that the free radical synthesis was NADPH oxidase-dependent, we further treated the cells with diphenylene iodonium (DPI), an inhibitor of the enzyme (35). Pre-treatment of X-ALD lymphoblasts with DPI significantly reduced the free radical levels (Fig. 2), suggesting that the oxidase contributes, at least in part, to the observed synthesis of ROS in non-stimulated X-ALD lymphoblasts.

Fig. 2.

NADPH oxidase-dependent free radical production in control and X-ALD lymphoblasts. The fluorescent dye H2DCFDA was utilized to measure the synthesis of free radical in cultured control (white bar) and X-ALD (black bars) lymphoblasts under non-stimulated conditions. NADPH oxidase contribution to free radical synthesis in X-ALD was determined by pre-incubation of lymphoblasts with the enzyme’s inhibitor DPI, as indicated in Methods section. The data represent the average ± SD of n = 6 experiments done in triplicate. ***: p < 0.0001

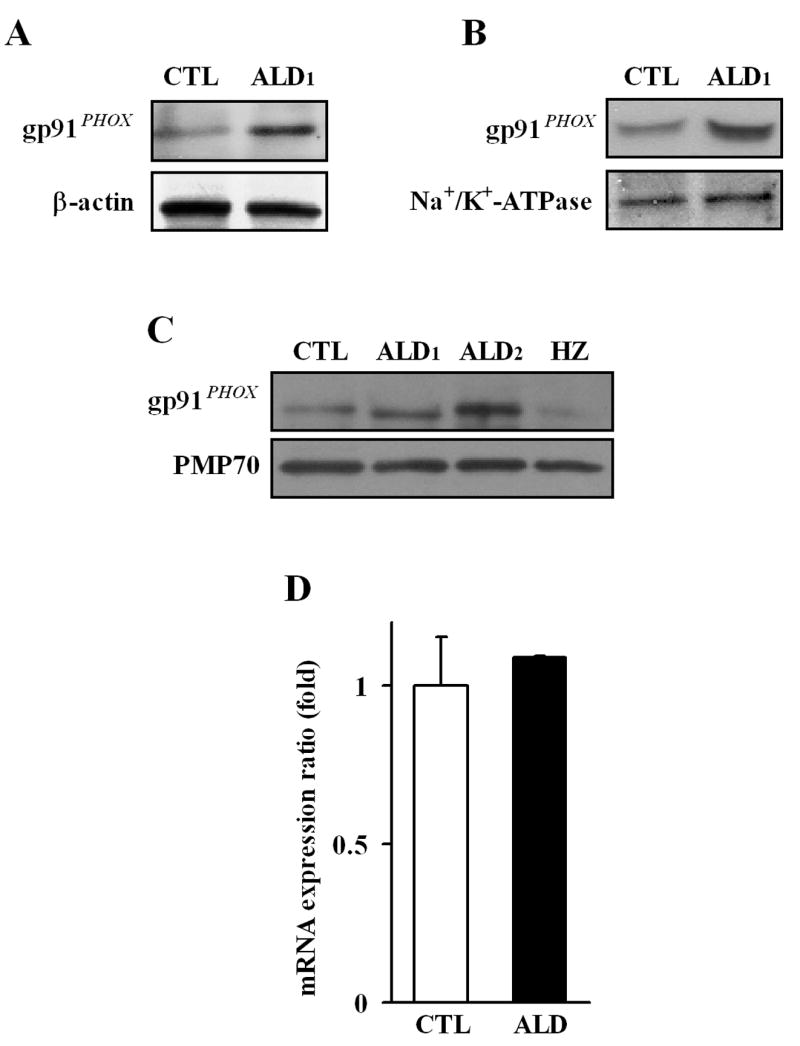

To investigate the possible mechanism of the observed increase in synthesis of ROS by NADPH oxidase, we assessed the protein levels and gene expression of gp91PHOX, the catalytic subunit of NADPH oxidase which is localized in the plasma membrane (17). The study of the catalytic subunit gp91PHOX protein levels by western blot in cell homogenate (Fig. 3A) and in total membranes (Fig. 3B), demonstrated a significant increase in the subunit in samples from X-ALD lymphoblasts, but not in those from control. To further evaluate whether the signal obtained from the membrane (fig. 3B) represents the gp91PHOX subunit which is anchored to or is associated with the cell membrane, we obtained carbonate membranes (i.e. membranes containing integral membrane proteins (36)) and screened them with antibodies against gp91PHOX and PMP70. In addition, we included a sample from ALD2 and heterozygote lymphoblasts to rule out individual cell line variations. The analysis using carbonate membranes demonstrated that gp91PHOX subunit is present at higher level in the samples from the X-ALD hemizygotes, than the samples from control and heterozygote lymphoblasts; whereas not much difference was observed in the levels of the integral membrane protein PMP70 when examined in those samples (Fig. 3C). Surprisingly, the mRNA level of gp91PHOX in X-ALD1 lymphoblasts was not significantly different from the levels found in control lymphoblasts (Fig. 3C). To evaluate whether this finding is specific for gp91PHOX or a phenomenon that affects all the subunits, western blot analysis was performed with specific antibodies against the two cytoplasmic subunits p47PHOX, p67PHOX in homogenate, total membranes, and cytosolic fractions. The analysis in total homogenate (Fig. 4A), as well as in the total membranes and cytosolic fractions (Fig. 4B) indicated that there were no significant changes in the protein levels of those subunits of NADPH oxidase in X-ALD lymphoblasts as compared to control. The mRNA analysis was consistent with the previous results, showing no appreciable differences in p47PHOX and p67PHOX mRNA levels (Fig. 4C, D). These data suggest that changes in the cell membrane properties of X-ALD lymphoblasts may be responsible for the higher protein levels of the gp91PHOX subunit observed in the X-ALD samples.

Fig. 3.

Protein level and expression of the NADPH oxidase membrane subunit gp91PHOX in different cell fractions from control and X-ALD lymphoblasts. Protein levels of the membrane anchored subunit gp91PHOX of NADPH oxidase was determined in total homogenate (A), and total membrane fractions (B), using specific antibodies. β-Actin and Na+/K+-ATPase (plasma membrane protein) were used as indicators of protein loading for homogenate (A) and membrane fractions (B) respectively. The levels of gp91PHOX subunit anchored in the cell membrane was analyzed by Western blot on the carbonate membrane fractions obtained from control (CTL: GM03798), cerebral X-ALD patients (ALD1: GM04673; ALD2: GM13496), and heterozygote (HZ: GM 03798)(C). PMP70 was screened as indicators of protein loading for the carbonate membranes preparations (integral membrane proteins). Western blots are representative of three different experiments. The gp91PHOX gene expression was determined by qRT-PCR analysis, and normalized to the expression of GAPDH (D), as indicated in Methods section. The data represent the average ± SD of n = 3 experiments done in triplicate.

Fig. 4.

Protein levels and expression of the NADPH oxidase cytoplasmic subunits p47PHOX and p67PHOX in control and X-ALD cultured lymphoblasts. Protein levels of the cytoplasmic subunits of NADPH oxidase (p47PHOX and p67PHOX) were determined in total cell homogenate (A), and membrane and cytosolic cell fractions (B), using Western blot analysis as indicated in Methods. β-Actin and Na+/K+-ATPase (plasma membrane protein) were used as indicator of protein loading for cell homogenate (A), and plasma membrane fractions (B) respectively. Levels of p47PHOX and p67PHOX gene expression were determined by quantitative qRT-PCR analysis and represented after normalization to the expression of GAPDH (C, D). Western blots are representative of three different experiments. Data represent the average ± SD of n = 3 experiments done in triplicate.

Nitric oxide and cytokines (TNFα and IL-1β) synthesis in non-stimulated X-ALD lymphoblasts

As reported earlier, peripheral blood mononuclear cells from X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy patients synthesize excessive levels of the proinflammatory cytokine Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF-α) when stimulated with bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (20, 21). Therefore, we investigated whether lymphoblasts are able to synthesize cytokines under non-stimulated conditions. We first determined the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO) released into the culture media in 24h under serum free conditions. The analysis showed that X-ALD lymphoblast production of NO is 2.1 folds that of controls (Fig. 5A). Further determination of the cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β indicated increased synthesis (2.1 and 2.3 folds respectively) of both cytokines in X-ALD lymphoblasts as compared to controls (Fig. 5B-C). In addition, we tested if the increased production of NO is susceptible to NaPA and lovastatin pharmacologic regulation. The synthesis of NO was markedly reduced by NaPA, and moderately by lovastatin; however combination of NaPA plus lovastatin did not reduced NO synthesis further than NaPA alone, after 7 days of treatment (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Nitric oxide production and cytokine synthesis in control and X-ALD cultured lymphoblasts and pharmacological regulation of nitric oxide synthesis. Nitric oxide (NO) levels (A) and cytokines synthesis (TNF-α (B) and IL-1β (C)) were determined in cell-free supernatants from cultured control (GM03798; white bars), and a cerebral X-ALD (GM04673; black bars) lymphoblasts as indicated in Methods sections. The pharmacologic effect of drugs (Lovastatin (1μM), NaPA (1 mM), or combination of both drugs) on the production of NO by Control and X-ALD lymphoblasts were analyzed after a week of treatment. The data represent the average ± SD of n = 3 experiments done in triplicate. (A-C) **: p < 0.003; ***: p < 0.0001; (D) *: p < 0.05; ***: p < 0.0001.

Discussion

The progression of X-ALD disease pathology encompasses two clear stages: a metabolic stage characterized by accumulation of VLC fatty acids in organs and body fluids and an inflammatory stage characterized by an immunoinflammatory response in the nervous system (7, 9). What triggers the transition from the metabolic to the inflammatory stage is still unknown, and the involvement of a modifier gene has been suggested (8). Differences found between X-ALD patients and the murine model of the disease (27), and the lack of clear expression of the disease in the animals, although they accumulate VLC fatty acids in the nervous system (12-14), suggest that oxidative stress may participate in the development/progression of the disease in X-ALD patients (16).

Here we report the activity of NADPH oxidase and the expression of its catalytic subunit gp91PHOX in control and X-ALD lymphoblast cell lines in culture, under non-stimulated conditions. Our data indicate that X-ALD lymphoblasts accumulate VLC fatty acids, and synthesize higher levels of free radicals. In addition, those cells present higher levels of the membrane anchored NADPH oxidase subunits gp91PHOX, but not of the cytoplasmic subunits p47PHOX or p67PHOX, without showing significant increase of its mRNA levels. This data suggest that the accumulation of VLC fatty acids in X-ALD lymphoblasts may cause the increase levels of the catalytic subunit of NADPH oxidase gp91PHOX observed in total cell homogenate and membrane fractions of those cells, and support previous reports that demonstrated that accumulation of VLC fatty acids induces changes in cell membrane properties that result in alteration of cell signaling (21, 23-26), Interestingly, the signal from gp91PHOX subunit observed by immuno-analysis of cell homogenates or total membranes samples is mainly the contribution of the protein being anchored in the membrane, as indicated by screening of membrane preparations that basically contain integral membrane proteins, and the use of the membrane protein PMP70 as a marker (36). Taken into consideration that gp91PHOX is an integral membrane protein (17), our data indicated that changes in the X-ALD cell membrane lipid environment may be interfering with its turnover, as we did not observe changes in its mRNA levels. Those results suggest that most of this protein is present as incorporated in the cell membrane, and base on the analysis of two different X-ALD lymphoblasts cell lines, the data indicates that this observation appears to be a characteristic of the oxidase subunit in X-ALD lymphoblasts, as it was present at low levels in the control and the heterozygote lymphoblasts analyzed. Unfortunately, there are no available lymphoblasts derived from the mild form of the disease (i.e. AMN), therefore, we can not test how they will behave. In addition, western blot analysis also indicates that a fraction of the other two cytoplasmic subunits of the NADPH oxidase (p47PHOX and p67PHOX) was found associated with the membranes at similar levels in control and X-ALD lymphoblasts, suggesting that the higher levels of synthesis of free radicals observed in X-ALD lymphoblasts under basal conditions, may be a consequence of the higher levels of the catalytic subunit gp91PHOX. The results also indicate that X-ALD lymphoblasts produce higher levels of NO and TNFα and IL-1β cytokines, suggesting additional alterations of other membrane proteins, and support previous studies reporting that cells derived from X-ALD patients have an increased proinflammatory response (20-22). Taken together, the data suggest that NADPH oxidase-produced free radicals may play an important role as a modulator of the development/progression of neuroinflammation in X-ALD disease.

Fatty acids have been described as potential NADPH oxidase activators in fibroblasts (37), neutrophils (38), and endothelial cells (39), therefore, activation of the enzyme in X-ALD lymphoblasts due to changes in the membrane fatty acids composition, is also possible. This assertion get additional supported by a study indicating that VLC fatty acids enriched C6 cells synthesize higher amounts of NO and superoxide products compared to native C6 cells when stimulated (23). Although the mechanism of superoxide synthesis was not investigated, this data support the reasoning that accumulation of VLC fatty acids may be altering membrane microdomains (lipid rafts) important for cell signaling (25, 26, 40).

Our observation that NaPA or lovastatin treatments can decrease the accumulation of VLC fatty acids levels and down regulate the synthesis of NO in X-ALD lymphoblasts suggest that these drugs may have pharmacological potential for the treatment of both the metabolic as well as the inflammatory disease of X-ALD, and support previously published data that indicated that lovastatin normalized the plasma levels of VLC fatty acids in X-ALD patients and that lovastatin or NaPA treatments normalized the VLC fatty acids levels of X-ALD fibroblasts in culture (32-34).

Acknowledgments

The fatty acids analysis done by Drs. M. Khan and S. Grewal is highly appreciated. We thank Dr. A.K. Singh for reviewing the manuscript. This work was supported by Grants from the Extramural Research Facilities Program of the National Center for Research Resources (C06 RR018823 and C06 RR015455) and from the National Institutes of Health (NS-22576; NS-34741; NS-37766; AG-25307).

References

- 1.Wanders RJ, Waterham HR. Biochemistry of mammalian peroxisomes revisited. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:295–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mosser J, Douar AM, Sarde CO, Kioschis P, Feil R, Moser H, Poustka AM, et al. Putative X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy gene shares unexpected homology with ABC transporters. Nature. 1993;361:726–730. doi: 10.1038/361726a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Contreras M, Mosser J, Mandel JL, Aubourg P, Singh I. The protein coded by the X-adrenoleukodystrophy gene is a peroxisomal integral membrane protein. FEBS Lett. 1994;344:211–215. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00400-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Contreras M, Sengupta TK, Sheikh F, Aubourg P, Singh I. Topology of ATP-binding domain of adrenoleukodystrophy gene product in peroxisomes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;334:369–379. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazo O, Contreras M, Hashmi M, Stanley W, Irazu C, Singh I. Peroxisomal lignoceroyl-CoA ligase deficiency in childhood adrenoleukodystrophy and adrenomyeloneuropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:7647–7651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makkar RS, Contreras MA, Paintlia AS, Smith BT, Haq E, Singh I. Molecular organization of peroxisomal enzymes: protein-protein interactions in the membrane and in the matrix. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006;451:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moser HW, Smith KD, Watkins PA, Powers J, M AB. X-Linked Adrenoleukodystrophy. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The Metabolic & Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. II. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 3257–3301. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith KD, Kemp S, Braiterman LT, Lu JF, Wei HM, Geraghty M, Stetten G, et al. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy: genes, mutations, and phenotypes. Neurochem Res. 1999;24:521–535. doi: 10.1023/a:1022535930009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powers JM, Liu Y, Moser AB, Moser HW. The inflammatory myelinopathy of adreno-leukodystrophy: cells, effector molecules, and pathogenetic implications. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1992;51:630–643. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilg AG, Singh AK, Singh I. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in the central nervous system of patients with X-adrenoleukodystrophy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:1063–1069. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.12.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paintlia AS, Gilg AG, Khan M, Singh AK, Barbosa E, Singh I. Correlation of very long chain fatty acid accumulation and inflammatory disease progression in childhood X-ALD: implications for potential therapies. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;14:425–439. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forss-Petter S, Werner H, Berger J, Lassmann H, Molzer B, Schwab MH, Bernheimer H, et al. Targeted inactivation of the X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy gene in mice. J Neurosci Res. 1997;50:829–843. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19971201)50:5<829::AID-JNR19>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi T, Shinnoh N, Kondo A, Yamada T. Adrenoleukodystrophy protein-deficient mice represent abnormality of very long chain fatty acid metabolism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;232:631–636. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu JF, Lawler AM, Watkins PA, Powers JM, Moser AB, Moser HW, Smith KD. A mouse model for X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9366–9371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powers JM, Pei Z, Heinzer AK, Deering R, Moser AB, Moser HW, Watkins PA, et al. Adreno-leukodystrophy: oxidative stress of mice and men. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:1067–1079. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000190064.28559.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vargas CR, Wajner M, Sirtori LR, Goulart L, Chiochetta M, Coelho D, Latini A, et al. Evidence that oxidative stress is increased in patients with X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1688:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babior BM. NADPH oxidase: an update. Blood. 1999;93:1464–1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segal AW. How neutrophils kill microbes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:197–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown GC. Mechanisms of inflammatory neurodegeneration: iNOS and NADPH oxidase. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1119–1121. doi: 10.1042/BST0351119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Biase A, Merendino N, Avellino C, Cappa M, Salvati S. Th 1 cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. J Neurol Sci. 2001;182:161–165. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00469-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lannuzel A, Aubourg P, Tardieu M. Excessive production of tumour necrosis factor alpha by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 1998;2:27–32. doi: 10.1016/1090-3798(98)01002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiffany CW, Hoefler S, Moser HW, Burch RM. Arachidonic acid metabolism in fibroblasts from patients with peroxisomal diseases: response to interleukin 1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1096:41–46. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(90)90010-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Biase A, Di Benedetto R, Fiorentini C, Travaglione S, Salvati S, Attorri L, Pietraforte D. Free radical release in C6 glial cells enriched in hexacosanoic acid: implication for X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy pathogenesis. Neurochem Int. 2004;44:215–221. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(03)00162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knazek RA, Rizzo WB, Schulman JD, Dave JR. Membrane microviscosity is increased in the erythrocytes of patients with adrenoleukodystrophy and adrenomyeloneuropathy. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:245–248. doi: 10.1172/JCI110963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho JK, Moser H, Kishimoto Y, Hamilton JA. Interactions of a very long chain fatty acid with model membranes and serum albumin. Implications for the pathogenesis of adrenoleukodystrophy. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1455–1463. doi: 10.1172/JCI118182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitcomb RW, Linehan WM, Knazek RA. Effects of long-chain, saturated fatty acids on membrane microviscosity and adrenocorticotropin responsiveness of human adrenocortical cells in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:185–188. doi: 10.1172/JCI113292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pujol A, Hindelang C, Callizot N, Bartsch U, Schachner M, Mandel JL. Late onset neurological phenotype of the X-ALD gene inactivation in mice: a mouse model for adrenomyeloneuropathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:499–505. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fourcade S, Lopez-Erauskin J, Galino J, Duval C, Naudi A, Jove M, Kemp S, et al. Early oxidative damage underlying neurodegeneration in X-adrenoleukodystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1762–1773. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan M, Contreras M, Singh I. Endotoxin-induced alterations of lipid and fatty acid compositions in rat liver peroxisomes. J Endotoxin Res. 2000;6:41–50. doi: 10.1177/09680519000060010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feinstein DL, Galea E, Roberts S, Berquist H, Wang H, Reis DJ. Induction of nitric oxide synthase in rat C6 glioma cells. J Neurochem. 1994;62:315–321. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62010315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh I, Khan M, Key L, Pai S. Lovastatin for X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:702–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh I, Pahan K, Khan M. Lovastatin and sodium phenylacetate normalize the levels of very long chain fatty acids in skin fibroblasts of X- adrenoleukodystrophy. FEBS Lett. 1998;426:342–346. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pai GS, Khan M, Barbosa E, Key LL, Craver JR, Cure JK, Betros R, et al. Lovastatin therapy for X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy: clinical and biochemical observations on 12 patients. Mol Genet Metab. 2000;69:312–322. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robertson AK, Cross AR, Jones OT, Andrew PW. The use of diphenylene iodonium, an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase, to investigate the antimicrobial action of human monocyte derived macrophages. J Immunol Methods. 1990;133:175–179. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90357-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujiki Y, Hubbard AL, Fowler S, Lazarow PB. Isolation of intracellular membranes by means of sodium carbonate treatment: application to endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 1982;93:97–102. doi: 10.1083/jcb.93.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossary A, Arab K, Steghens JP. Polyunsaturated fatty acids modulate NOX 4 anion superoxide production in human fibroblasts. Biochem J. 2007;406:77–83. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shao D, Segal AW, Dekker LV. Lipid rafts determine efficiency of NADPH oxidase activation in neutrophils. FEBS Lett. 2003;550:101–106. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00845-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cui XL, Douglas JG. Arachidonic acid activates c-jun N-terminal kinase through NADPH oxidase in rabbit proximal tubular epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3771–3776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang AY, Yi F, Zhang G, Gulbins E, Li PL. Lipid raft clustering and redox signaling platform formation in coronary arterial endothelial cells. Hypertension. 2006;47:74–80. doi: 10.1161/10.1161/01.HYP.0000196727.53300.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]