Abstract

Neutrality tests based on the frequency spectrum (e.g., Tajima's D or Fu and Li's F) are commonly used by population geneticists as routine tests to assess the goodness-of-fit of the standard neutral model on their data sets. Here, I show that these neutrality tests are specific instances of a general model that encompasses them all. I illustrate how this general framework can be taken advantage of to devise new more powerful tests that better detect deviations from the standard model. Finally, I exemplify the usefulness of the framework on SNP data by showing how it supports the selection hypothesis in the lactase human gene by overcoming the ascertainment bias. The framework presented here paves the way for constructing novel tests optimized for specific violations of the standard model that ultimately will help to unravel scenarios of evolution.

THE standard models of population genetics (i.e., the Wright–Fisher model and related ones) constitute null models for which an amazing amount of theory has been developed. Population geneticists have used some aspect of the theory (e.g., summary statistics) to test the goodness-of-fit of the standard model on a given data set. Rejection of the standard model typically suggests that alternative hypotheses, such as selection or demographic history, have to be accounted for. Although they test for more than neutrality, tests that compute the goodness-of-fit of the standard model have been referred to as “neutrality tests.” Since different neutrality tests have varying sensitivity to different violations of the standard model, one typically uses a plethora of tests on the data set of interest. One then hopes that the evolutionary processes that generated the data set will be, at least partially, uncovered by the tests. Although neutrality tests based on population samples exhibit important diversity, they can be assigned to families such as “haplotype tests” (e.g., Fu 1997; Depaulis and Veuille 1998) that use the distribution of haplotypes, “tree shape tests” that try to capture specific tree deformations (e.g., Ramos-Onsins and Rozas 2002), and “frequency spectrum tests” that are based on the frequency spectrum (e.g., Tajima 1989; Fu and Li 1993b; Fay and Wu 2000; Achaz 2008).

In this study, I investigate neutrality tests based on the frequency spectrum (hereafter referred to simply as neutrality tests) and show that they are all specific instances of a general framework. Neutrality tests compare two estimators of the population mutation parameter θ that characterizes the mutation–drift equilibrium. It is defined as θ = 2pNeμ, where p is the ploidy (1 for haploids and 2 for diploids), Ne is the effective population size, and μ is the locus neutral mutation rate. When the standard model is true, the expectations of the several unbiased estimators of θ are equal.

Typical estimators of θ, in a sample of n sequences, are  , where S is the number of polymorphic sites and

, where S is the number of polymorphic sites and  (Watterson 1975), and

(Watterson 1975), and  , where π is the average pairwise difference between all sequences in the sample (Tajima 1983). If an outgroup is available, mutations at frequency i/n can be distinguished from mutations at frequency 1 − i/n. Following Fu (1995)'s notations, ξ is a vector that represents the unfolded frequency spectrum composed of ξi, the number of polymorphic sites at frequency i/n in the sample (i ∈ [1, n − 1]). When no outgroup is available, the frequency spectrum is folded and is given by a vector η, composed of ηi, the number of polymorphic sites at both frequencies i/n and 1 − i/n. Accordingly, it has been shown that θ can be estimated from

, where π is the average pairwise difference between all sequences in the sample (Tajima 1983). If an outgroup is available, mutations at frequency i/n can be distinguished from mutations at frequency 1 − i/n. Following Fu (1995)'s notations, ξ is a vector that represents the unfolded frequency spectrum composed of ξi, the number of polymorphic sites at frequency i/n in the sample (i ∈ [1, n − 1]). When no outgroup is available, the frequency spectrum is folded and is given by a vector η, composed of ηi, the number of polymorphic sites at both frequencies i/n and 1 − i/n. Accordingly, it has been shown that θ can be estimated from  , with ξ1 the number of derived singletons (Fu and Li 1993b), from

, with ξ1 the number of derived singletons (Fu and Li 1993b), from  , with η1 the total number of singletons (derived and ancestral) (Fu and Li 1993b), and from

, with η1 the total number of singletons (derived and ancestral) (Fu and Li 1993b), and from  (Fay and Wu 2000). Recently, it has been suggested that singletons should be ignored when θ is estimated in samples with sequencing errors; this leads to estimators such as

(Fay and Wu 2000). Recently, it has been suggested that singletons should be ignored when θ is estimated in samples with sequencing errors; this leads to estimators such as  , and

, and  (Achaz 2008). Other estimators of θ, such as

(Achaz 2008). Other estimators of θ, such as  and

and  , were designed to minimize their variance (Fu 1994b), although they can be computed using recursions only for a given value of θ.

, were designed to minimize their variance (Fu 1994b), although they can be computed using recursions only for a given value of θ.

Neutrality tests compute the goodness-of-fit of a statistic T, which is the difference between two estimators of θ, normalized by its standard deviation:

|

(1) |

For a given θ, under the standard model, T has a mean of E[T] = 0 and a variance of Var[T] = 1. Lowercase letters (e.g., t) denote the absolute difference (i.e., the numerator only) and uppercase letters (e.g., T) denote the normalized difference (Equation 1) throughout this work. Interestingly, the variance in the denominator is a function of both θ and θ2. Because θ is unknown, the denominator cannot be computed as such. In practice, unbiased estimators of θ and θ2 must be used instead. Because the variance of  vanishes asymptotically in a very large sample (

vanishes asymptotically in a very large sample ( ), θ and θ2 are, in practice, substituted by estimators based on S (Tajima 1989), which changes the mean and the variance of T to E[T] ≈ 0 and Var[T] ≈ 1.

), θ and θ2 are, in practice, substituted by estimators based on S (Tajima 1989), which changes the mean and the variance of T to E[T] ≈ 0 and Var[T] ≈ 1.

Tajima's D (Tajima 1989) is defined by  ; the statistics proposed by Fu and Li (1993b) are

; the statistics proposed by Fu and Li (1993b) are  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . Another classical statistic is

. Another classical statistic is  (Fay and Wu 2000), even though its variance was not given by the authors. Finally, two other related neutrality tests that are, a priori, immune to sequencing errors were proposed:

(Fay and Wu 2000), even though its variance was not given by the authors. Finally, two other related neutrality tests that are, a priori, immune to sequencing errors were proposed:  and

and  (Achaz 2008). Other tests based on θξ and θη (which are optimized for a given θ-value) as well as the difference between the observed and the expected values of the frequency spectrum were also proposed (Fu 1996).

(Achaz 2008). Other tests based on θξ and θη (which are optimized for a given θ-value) as well as the difference between the observed and the expected values of the frequency spectrum were also proposed (Fu 1996).

Here, I show that when using a general weighted linear combination of  (or

(or  when no outgroup is available), any estimators of θ [i.e.,

when no outgroup is available), any estimators of θ [i.e.,  ] and consequently any neutrality tests can be derived. Nawa and Tajima (2008) recently advocated the use of the

] and consequently any neutrality tests can be derived. Nawa and Tajima (2008) recently advocated the use of the  spectrum, which is expected to be uniform under the standard model, as a visual test for neutrality instead of the classical frequency spectrum. This last proposal is in complete agreement with the current work. Importantly, it has been previously reported that some θ-estimators and neutrality tests could be expressed as specific linear combinations of ξi or ηi (Tajima 1997; Wakeley 2009). Furthermore, Fu (1997) shows that several θ-estimators can be expressed as specific linear combinations of

spectrum, which is expected to be uniform under the standard model, as a visual test for neutrality instead of the classical frequency spectrum. This last proposal is in complete agreement with the current work. Importantly, it has been previously reported that some θ-estimators and neutrality tests could be expressed as specific linear combinations of ξi or ηi (Tajima 1997; Wakeley 2009). Furthermore, Fu (1997) shows that several θ-estimators can be expressed as specific linear combinations of  (

( ) or in a related framework that uses

) or in a related framework that uses  instead of

instead of  .

.  was subsequently designed as

was subsequently designed as  (Fay and Wu 2000). However, some estimators (like

(Fay and Wu 2000). However, some estimators (like  ,

,  , or

, or  ) cannot be expressed using the Fu (1997) framework. To the best of my knowledge, no previous study has explicitly derived the framework presented here. No work has yet highlighted the striking simplicity of θ-estimators and related tests, when expressed in this framework. I further show how the use of such a simple framework greatly facilitates the study of previous θ-estimators and their related neutrality tests and how it opens the door for constructing yet undiscovered interesting θ-estimators and neutrality tests with enhanced power.

) cannot be expressed using the Fu (1997) framework. To the best of my knowledge, no previous study has explicitly derived the framework presented here. No work has yet highlighted the striking simplicity of θ-estimators and related tests, when expressed in this framework. I further show how the use of such a simple framework greatly facilitates the study of previous θ-estimators and their related neutrality tests and how it opens the door for constructing yet undiscovered interesting θ-estimators and neutrality tests with enhanced power.

MODEL

With an outgroup:

According to Fu (1995), we know that

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

where σii and σij depend only on n and are given in Equation 2 of Fu (1995). This shows that E[iξi] = θ and therefore that any ξi can be used to construct an unbiased estimator of θ:

|

(5) |

Consequently, a linear combination  of the

of the  's (in which the weights sum to 1) is also an unbiased estimator of θ. Mathematically, it is expressed as

's (in which the weights sum to 1) is also an unbiased estimator of θ. Mathematically, it is expressed as

|

(6) |

where ωi is the weight of each  in the combined estimator. Therefore, any estimator based on the frequency spectrum can be solely described by an

in the combined estimator. Therefore, any estimator based on the frequency spectrum can be solely described by an  -vector. Importantly, it should be mentioned that Fu (1997) also proposed a linear combination of iξi, but in which only a subset of the weight vectors was used. Namely, the proposed weight vectors were restricted to ωi = i−x.

-vector. Importantly, it should be mentioned that Fu (1997) also proposed a linear combination of iξi, but in which only a subset of the weight vectors was used. Namely, the proposed weight vectors were restricted to ωi = i−x.

Using Equations 3 and 4 the variance of  can be shown to be

can be shown to be

|

(7) |

Following Tajima (1989), using Equation 1, one can compute a normalized statistic that is, in the general framework,

|

(8) |

which can be expressed as a function of an Ω-vector,

|

(9) |

with

|

|

|

The Ω-vector results from the difference between two weight vectors normalized to 1. As a consequence, (1) all elements of the Ω-vector sum to 0 and (2) the sum of all positive values cannot be >1 and the sum of all negative values cannot be < −1. Any vector that fits these two constraints can be considered, along with Equation 9, as a neutrality test.

Without an outgroup:

If no adequate outgroup is available, the unfolded frequency spectrum and consequently the  spectrum, cannot be computed. This implies that one has to use the

spectrum, cannot be computed. This implies that one has to use the  folded frequency spectrum. Following Fu (1995), we define

folded frequency spectrum. Following Fu (1995), we define  and therefore we have

and therefore we have

|

(10) |

|

(11) |

|

(12) |

where δi,n−i is a Kronecker delta (1 if i = j, and 0 otherwise) and where

|

|

|

Although, we cannot compute the  spectrum (as defined above), we can compute a folded

spectrum (as defined above), we can compute a folded  spectrum defined as

spectrum defined as

|

(13) |

This folded  spectrum is the visual neutrality test proposed by Nawa and Tajima (2008). Using a similar reasoning to that above, a linear combination of

spectrum is the visual neutrality test proposed by Nawa and Tajima (2008). Using a similar reasoning to that above, a linear combination of  leads to a generic unbiased estimator of θ defined as

leads to a generic unbiased estimator of θ defined as

|

(14) |

whose variance is given by

|

(15) |

Consequently, the corresponding neutrality test  is

is

|

(16) |

with

|

|

|

It is important to mention that Tajima (1997) previously showed that D, F*, and  could be expressed as a linear combination of ηi. More precisely, the vectors used then correspond in the present framework to

could be expressed as a linear combination of ηi. More precisely, the vectors used then correspond in the present framework to  . This vector definition emphasizes the weight on each ηi rather than on each

. This vector definition emphasizes the weight on each ηi rather than on each  .

.

With or without an outgroup:

Using both definitions of  (Equation 5) and

(Equation 5) and  (Equation 13), it is easy to show that we have

(Equation 13), it is easy to show that we have

|

(17) |

As a consequence, the use of an  -vector along with the

-vector along with the  folded frequency spectrum is equivalent to the use of an

folded frequency spectrum is equivalent to the use of an  -vector with the

-vector with the  unfolded frequency spectrum only when we have

unfolded frequency spectrum only when we have

|

(18) |

This makes clear that there is an equivalent  -vector for any

-vector for any  -vector that adheres to the following constraint:

-vector that adheres to the following constraint:

|

(19) |

To fold the frequency spectrum, the weight iωi associated with ξi (and not with  ) has to be the same as the weight (n − i)ωn−i associated with ξn−i. This translates into an iωi vector that is symmetric around n/2. Furthermore, when the constraint (expressed in Equation 19) is fulfilled, we can write, for any 0 ≤ f ≤ 1,

) has to be the same as the weight (n − i)ωn−i associated with ξn−i. This translates into an iωi vector that is symmetric around n/2. Furthermore, when the constraint (expressed in Equation 19) is fulfilled, we can write, for any 0 ≤ f ≤ 1,

|

which leads interestingly for f = (n − i)/n to

|

(20) |

The weights on  simply result from the sums of the weights on

simply result from the sums of the weights on  and on

and on  that are pooled when the spectrum is folded. In that respect, any

that are pooled when the spectrum is folded. In that respect, any  -vector complying to Equation 19 can be used without the help of an outgroup. The

-vector complying to Equation 19 can be used without the help of an outgroup. The  -vectors are then a subset of all possible values of the

-vectors are then a subset of all possible values of the  -vectors. The former can be computed from the latter by using Equation 18 or 20.

-vectors. The former can be computed from the latter by using Equation 18 or 20.

Because  is the difference between two normalized

is the difference between two normalized  -vectors, all relationships between

-vectors, all relationships between  and

and  expressed above also hold for

expressed above also hold for  and

and  .

.

RESULTS

The model described above shows that all estimators of θ based on the frequency spectrum are linear combinations of  , weighted by a specific vector

, weighted by a specific vector  . When no outgroup is available, one can use a linear combination of

. When no outgroup is available, one can use a linear combination of  , weighted by a vector

, weighted by a vector  . Consequently, neutrality tests can be expressed as a linear combination of

. Consequently, neutrality tests can be expressed as a linear combination of  (or

(or  ) weighted by a vector

) weighted by a vector  (or

(or  ), for which a variance can be computed easily. Three applications of the model are developed below. First, I reinvestigate the previous estimators of θ and their corresponding neutrality tests and frame their intrinsic properties in terms of the

), for which a variance can be computed easily. Three applications of the model are developed below. First, I reinvestigate the previous estimators of θ and their corresponding neutrality tests and frame their intrinsic properties in terms of the  (

( ) spectrum. Then, since previous tests are only specific instances of the framework, I show how the model can be used to build new tests that are more powerful than previous ones. Finally, I exemplify the benefit of the framework on real data that are known to be subject to an ascertainment bias.

) spectrum. Then, since previous tests are only specific instances of the framework, I show how the model can be used to build new tests that are more powerful than previous ones. Finally, I exemplify the benefit of the framework on real data that are known to be subject to an ascertainment bias.

Previous θ-estimators and neutrality tests:

Using Equation 6, all previously reported θ-estimators are given by an  -vector (Table 1). When defined, the corresponding

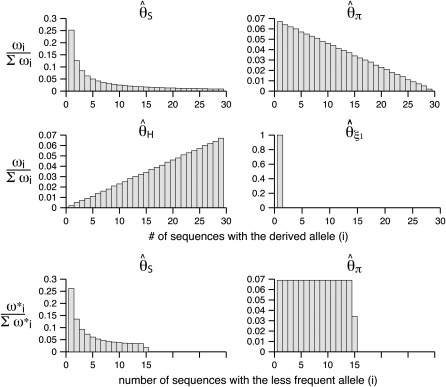

-vector (Table 1). When defined, the corresponding  -vectors are also provided (Table 1). A graphical representation of four estimators of θ is shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 highlights that both

-vectors are also provided (Table 1). A graphical representation of four estimators of θ is shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 highlights that both  and

and  emphasize the low-frequency polymorphic sites in their estimation of θ (although not as much as

emphasize the low-frequency polymorphic sites in their estimation of θ (although not as much as  , which is solely based on derived singletons) and that, on the contrary,

, which is solely based on derived singletons) and that, on the contrary,  gives more weight to ancestral polymorphisms. Framed in the folded spectrum,

gives more weight to ancestral polymorphisms. Framed in the folded spectrum,  still weights more low plus high frequencies whereas

still weights more low plus high frequencies whereas  has a uniform weight. Potentially, using other weight vectors, one could express any undiscovered estimator of θ based on the frequency spectrum.

has a uniform weight. Potentially, using other weight vectors, one could express any undiscovered estimator of θ based on the frequency spectrum.

TABLE 1.

Basic characteristics of previous estimators of θ

| ω* (when defined) | Variance (n = 30)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimators | ω | θ = 1 | θ = 10 | θ = 100 | |

|

|

|

0.36 | 12.8 | 1052 |

|

|

|

0.59 | 27.4 | 2419 |

|

|

|

1.22 | 35.1 | 2839 |

|

|

|

0.52 | 21.4 | 1833 |

|

|

|

0.68 | 31.9 | 2825 |

|

|

— | 1.15 | 25.0 | 1599 |

|

|

— | 1.55 | 65.0 | 5597 |

|

|

— | 0.51 | 20.3 | 1730 |

|

|

— | 0.68 | 31.5 | 2790 |

Figure 1.—

Estimators of θ. A graphical view of the weight vectors of four typical estimators of θ (for n = 30). All values of the normalized vector sum to 1. In the top four panels, the  -vectors that are defined for the unfolded frequency spectrum (

-vectors that are defined for the unfolded frequency spectrum ( ) are given, whereas the two bottom ones are the

) are given, whereas the two bottom ones are the  -vectors that are defined for the folded frequency spectrum (

-vectors that are defined for the folded frequency spectrum ( ). For estimators that can be defined in terms of both

). For estimators that can be defined in terms of both  and

and  (here

(here  and

and  ), the latter can be computed from the former with

), the latter can be computed from the former with  (when i ≠ n − i) or

(when i ≠ n − i) or  (when i = n − i).

(when i = n − i).

The numerical variances of the previous estimators of θ are reported in Table 1 (for n = 30 and θ = 1, 10, 100). They can be computed either by their original derivations or by Equation 7. This clearly shows that, among previous estimators of θ, the variance of  is the smallest and that of

is the smallest and that of  is the largest. This can be explained by the fact that the variance of

is the largest. This can be explained by the fact that the variance of  increases with i. As a consequence

increases with i. As a consequence  , which puts more weight on ancestral alleles, shows a larger variance. Interestingly, estimators without singletons have relatively small variances.

, which puts more weight on ancestral alleles, shows a larger variance. Interestingly, estimators without singletons have relatively small variances.

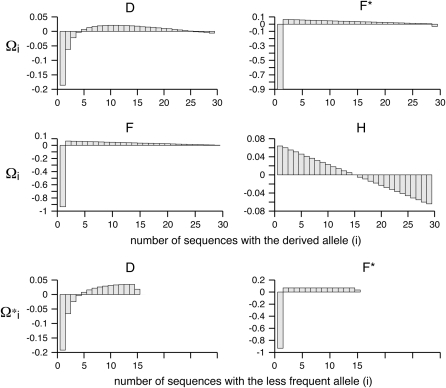

Previous neutrality tests are given in Table 2. A graphical representation of the  -vectors (and

-vectors (and  when defined) used in four previous tests is reported in Figure 2. Figure 2 shows that the sensitivity of the different tests differs although they share some common features. For example, D and F* both are negatively sensitive to both low and high frequencies (although more sensitive to low frequencies). D shows opposite sensitivity between medium frequencies and low/high frequency, whereas F* shows poor sensitivity to medium-frequency polymorphisms. F and F* have opposite effects on doubletons and singletons. Thus, deviations that enhance both will have opposite effects. Finally, H is oppositely skewed by low and high frequencies.

when defined) used in four previous tests is reported in Figure 2. Figure 2 shows that the sensitivity of the different tests differs although they share some common features. For example, D and F* both are negatively sensitive to both low and high frequencies (although more sensitive to low frequencies). D shows opposite sensitivity between medium frequencies and low/high frequency, whereas F* shows poor sensitivity to medium-frequency polymorphisms. F and F* have opposite effects on doubletons and singletons. Thus, deviations that enhance both will have opposite effects. Finally, H is oppositely skewed by low and high frequencies.

TABLE 2.

Basic characteristics of neutrality tests

| Mandatory outgroup | Variance (n = 30)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test |  |

|

θ = 1 | θ = 10 | θ = 100 | |

| d |  |

|

0.18 | 8.2 | 728 | |

| f |  |

|

No | 1.62 | 51.9 | 4,084 |

| d2 |  |

|

0.93 | 25.8 | 1,910 | |

| y |  |

|

0.12 | 6.2 | 558 | |

| h |  |

|

0.98 | 40.0 | 3,417 | |

| f * |  |

|

Yes | 1.71 | 63.8 | 5,314 |

| d2* |  |

|

0.99 | 34.5 | 2,805 | |

| y* |  |

|

0.12 | 5.8 | 524 | |

| TΩ | ω1i = e−0.9i | ω2i = 1 | 1.19 | 37.1 | 2,895 | |

|

ω2i = 1 | Yes | 2.48 | 151.4 | 14,167 | |

Figure 2.—

Neutrality tests. A graphical view of the weight vectors of four typical neutrality tests (for n = 30). Because the  -vectors used for neutrality tests are computed as a difference between two normalized vectors, all values of

-vectors used for neutrality tests are computed as a difference between two normalized vectors, all values of  sum to 0. In the top four panels, the

sum to 0. In the top four panels, the  -vectors that are defined for the unfolded frequency spectrum (

-vectors that are defined for the unfolded frequency spectrum ( ) are given, whereas the two bottom ones are the

) are given, whereas the two bottom ones are the  -vectors that are defined for the folded frequency spectrum (

-vectors that are defined for the folded frequency spectrum ( ). For estimators that can be defined in terms of both

). For estimators that can be defined in terms of both  and

and  (here D and F *), the latter can be computed from the former in the way that

(here D and F *), the latter can be computed from the former in the way that  can be deduced from ωi.

can be deduced from ωi.

One crucial aspect of neutrality tests is their important variance under the neutral model. This variance induces a large confidence interval and therefore decreases their power to detect a deviation. It has been argued that this variance is a consequence of the tree shape variance and that neutrality tests based on the frequency spectrum are doomed to exhibit low power (Felsenstein 1992b).

As a consequence, an ideal neutrality test should minimize its variance under the standard model. The variances of the denominator of previous neutrality tests are given in Table 2 (for n = 30 and θ = 1, 10, 100). It is also important to mention that previous derivations of f, f *, y, and y* variances give different values. Simulations show that the new derivations are the correct ones (supporting information, Table S1). First, it should be noted that the original D test has a very low variance when compared to all other tests. This is connected to the low variance of both  and

and  . Second, Y and Y * tests have also a small variance, although they ignore an important fraction of the data (i.e., singletons). All other tests have a similar variance.

. Second, Y and Y * tests have also a small variance, although they ignore an important fraction of the data (i.e., singletons). All other tests have a similar variance.

This predicts that D typically will be sensitive to low, medium, and high frequencies and should be more powerful because it has a relatively low variance under neutrality. Therefore, it has the potential to be an excellent neutrality test and it appears that it is often one of the most powerful tests (Simonsen et al. 1995; Fu 1997). H is sensitive either low or high frequencies; however, its larger variance predicts that it will be useful only when the distortion in the θ-spectrum is very strong. In practice, it is powerful only when there is a large excess of high-frequency polymorphisms. The singleton tests appear to be good candidates to capture an excess of singletons, although they neglect other deviations in the spectrum. The Y and Y * tests have low variance, although ignoring singletons can lead to low power especially when they are in excess (Achaz 2008).

Building new tests:

To design new neutrality tests using this framework I started by analyzing the deviation of the average  spectrum, which is expected to be uniform under the standard models. Furthermore, because Fu (1995) showed that the covariance between ξi's is weak when compared to their variance, visual inspection of the variance of

spectrum, which is expected to be uniform under the standard models. Furthermore, because Fu (1995) showed that the covariance between ξi's is weak when compared to their variance, visual inspection of the variance of  provides a first approximation to the expected variance of

provides a first approximation to the expected variance of  and therefore of their related Tω tests. I studied two deviations from the standard model: a severe bottleneck and isolated populations with migration.

and therefore of their related Tω tests. I studied two deviations from the standard model: a severe bottleneck and isolated populations with migration.

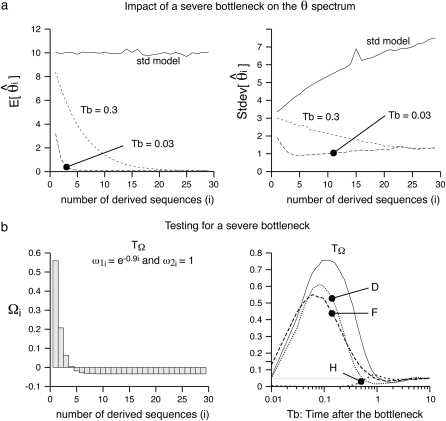

The severe bottleneck was simulated as a sudden change of size from N chromosomes to N/100 that lasts for a time Tl = 0.1 (in N generations). Accordingly, the coalescent rates within the bottleneck are accelerated by 0.01 and the simulations were performed as in Simonsen et al. (1995). Sampling was performed after a time Tb has elapsed after the bottleneck. The mean and the standard deviation of  are given in Figure 3a for two times, Tb = 0.03 and Tb = 0.3. Figure 3 shows that most of the deviation comes from the sites with low frequency. Therefore, I designed a new test that captures the deviations within low frequencies. In this test, I used a first vector of ω1i = e−αi, with α = 0.9 and a second uniform vector ω2i = 1. This results in an exponentially decreasing weight for low-frequency mutations (Figure 3) that is positive for frequency i/n ≤ 0.13. The choice of α = 0.9 was mostly empirical, although using α = 0.8 or α = 1 leads to similar results (data not shown). As stressed in the discussion, this study aims at illustrating how easy it is to create new tests with enhanced power; power optimization deserves an entire new study. A graphical view of the

are given in Figure 3a for two times, Tb = 0.03 and Tb = 0.3. Figure 3 shows that most of the deviation comes from the sites with low frequency. Therefore, I designed a new test that captures the deviations within low frequencies. In this test, I used a first vector of ω1i = e−αi, with α = 0.9 and a second uniform vector ω2i = 1. This results in an exponentially decreasing weight for low-frequency mutations (Figure 3) that is positive for frequency i/n ≤ 0.13. The choice of α = 0.9 was mostly empirical, although using α = 0.8 or α = 1 leads to similar results (data not shown). As stressed in the discussion, this study aims at illustrating how easy it is to create new tests with enhanced power; power optimization deserves an entire new study. A graphical view of the  -vector associated with this new TΩ test is given in Figure 3 and its variance is reported in Table 2. Most of the weight of this test is given to low frequencies and its variance is comparable to those of other neutrality tests. The power of this new test and of D, F, and H is reported in Figure 3. Results show that the new test outperforms the previous tests by 20% and is able to detect the deviation for a longer time.

-vector associated with this new TΩ test is given in Figure 3 and its variance is reported in Table 2. Most of the weight of this test is given to low frequencies and its variance is comparable to those of other neutrality tests. The power of this new test and of D, F, and H is reported in Figure 3. Results show that the new test outperforms the previous tests by 20% and is able to detect the deviation for a longer time.

Figure 3.—

Example of a severe bottleneck. (a) The mean and the standard deviation of the  spectrum that is observed in simulations (n = 30, 104 replicates) of a standard model or of a recent severe bottleneck (reduction of f = 1/100 for a time Tl = 0.1). In both times after the bottleneck (Tb = 0.03 and Tb = 0.3), the observed trend is similar: an excess in low frequency of

spectrum that is observed in simulations (n = 30, 104 replicates) of a standard model or of a recent severe bottleneck (reduction of f = 1/100 for a time Tl = 0.1). In both times after the bottleneck (Tb = 0.03 and Tb = 0.3), the observed trend is similar: an excess in low frequency of  , though stronger for Tb = 0.03. (b) Left, the weight vector of a new neutrality test (here TΩ) is reported. It focuses its sensitivity on low frequencies:

, though stronger for Tb = 0.03. (b) Left, the weight vector of a new neutrality test (here TΩ) is reported. It focuses its sensitivity on low frequencies:  . (b) Right, the power of four neutrality tests is compared in detecting a severe bottleneck as a function of the time elapsed after the bottleneck. The new test shows enhanced power to detect the bottleneck (more power for a longer time).

. (b) Right, the power of four neutrality tests is compared in detecting a severe bottleneck as a function of the time elapsed after the bottleneck. The new test shows enhanced power to detect the bottleneck (more power for a longer time).

The 95% confidence intervals were built using coalescent simulations under the standard model, using a fixed number of segregating sites (Hudson 1993; Depaulis and Veuille 1998). Although there has been much debate on how confidence intervals should be set (Depaulis et al. 2001; Markovtsova et al. 2001; Wall and Hudson 2001), it has been clearly shown that the choice of a particular method does not alter the results in standard models (Ramos-Onsins et al. 2007) and therefore is not discussed here.

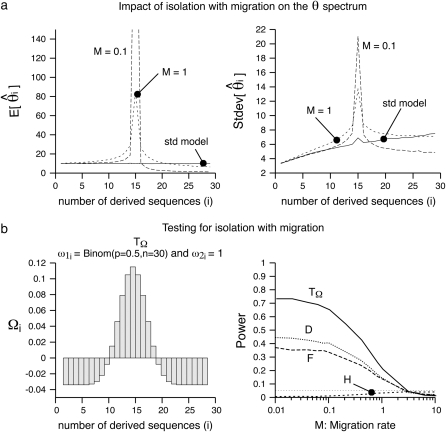

In the second scenario, I compared the power of neutrality tests in detecting a case of isolation with migration (e.g., Nielsen and Wakeley 2001). In the simulations, the isolation event happened at time Ti = 3 and both populations were sampled equally (na = nb = 15). The migration rate between the two populations is variable. Similar to the analysis of the bottleneck, I first report the mean and the standard deviation of the  spectrum. Figure 4 shows that most of the deviation comes from the sites at frequency 15/30. Additionally, for a small enough migration rate (M = 0.1), there are almost no polymorphisms with frequency >0.5. Although the standard deviations are large, the coefficients of variations (variance/mean) are relatively small. To design a new test, I used for the first

spectrum. Figure 4 shows that most of the deviation comes from the sites at frequency 15/30. Additionally, for a small enough migration rate (M = 0.1), there are almost no polymorphisms with frequency >0.5. Although the standard deviations are large, the coefficients of variations (variance/mean) are relatively small. To design a new test, I used for the first  -vector the probabilities given by a binomial law,

-vector the probabilities given by a binomial law,  with p = 0.5 and n = 30 and a uniform vector ω2i = 1 as a second vector.

with p = 0.5 and n = 30 and a uniform vector ω2i = 1 as a second vector.

Figure 4.—

Isolation with migration. (a) The mean and the standard deviation of the  spectrum that is observed in simulations (n = 30, 104 replicates) of a standard model or of an isolation with migration model (two populations equally sampled, na = nb = 15 that were a single ancestral panmictic population at time Ti = 3). In both sampling migration rates between the two populations (M = 0.1 and M = 1), the observed trend is similar: an excess of

spectrum that is observed in simulations (n = 30, 104 replicates) of a standard model or of an isolation with migration model (two populations equally sampled, na = nb = 15 that were a single ancestral panmictic population at time Ti = 3). In both sampling migration rates between the two populations (M = 0.1 and M = 1), the observed trend is similar: an excess of  , though much stronger for M = 0.1. (b) Left, the weight vector of a new neutrality test (Tω) that focuses its sensitivity on i = 15. The weight vector used here is

, though much stronger for M = 0.1. (b) Left, the weight vector of a new neutrality test (Tω) that focuses its sensitivity on i = 15. The weight vector used here is  , where

, where  is obtained using a binomial with p = 0.5 and n = 30. (b) Right, the power of four neutrality tests is compared when detecting the population structure as a function of the migration rate. The new test displays much more power to detect the population structure.

is obtained using a binomial with p = 0.5 and n = 30. (b) Right, the power of four neutrality tests is compared when detecting the population structure as a function of the migration rate. The new test displays much more power to detect the population structure.

This was motivated by the idea of designing a test that specifically captures an excess of medium-frequency polymorphisms. A graphical view of the resulting  -vector is given in Figure 4 and its variance is given in Table 2. Almost all the weight of this test is given to the 13 < i < 17 sites. The variance of this new test is large, and this is related to the large variance of

-vector is given in Figure 4 and its variance is given in Table 2. Almost all the weight of this test is given to the 13 < i < 17 sites. The variance of this new test is large, and this is related to the large variance of  in the sample with even n. Despite this large variance, the test clearly outperforms all previous tests (Figure 4).

in the sample with even n. Despite this large variance, the test clearly outperforms all previous tests (Figure 4).

Overcoming the ascertainment bias:

As an example of the power of designing new neutrality tests, I analyzed SNP data (from HapMap) around the Lactase gene (LCT), which has been shown to exhibit a footprint of a recent strong selective sweep in European populations (Bersaglieri et al. 2004) as well in eastern African populations (Tishkoff et al. 2007). This pattern of recent selection is one of the strongest in the human genome (Nielsen et al. 2005). Indeed, it has been advanced that the lactase-persistence phenotype (the ability to digest milk as an adult) has been advantageous in European populations of farmers (especially in Northern European ones). The SNPs that are tightly associated with the selective sweep in Europeans are located at 13–22 kb upstream of the gene start (Bersaglieri et al. 2004). From HapMap (release 27, February 2009) I gathered all SNPs in a window of 100 kb centered at the start of the lactase gene. This includes 50 kb upstream and the entire gene. I considered only SNPs whose sample size was at least 85 chromosomes. Because the sample size of all SNPs was not identical, I used the observed frequencies to generate a folded frequency spectrum of 85 chromosomes for the following populations: Utah residents with northern and western European ancestry from the CEPH collection (CEU); Han Chinese in Beijing, China (CHB); Japanese in Tokyo, Japan (JPT); and Yoruban in Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI).

According to the literature, one expects to find a trace of an ongoing selective event in the CEU population only. Without the help of an outgroup, this would translate into an excess of low-frequency polymorphism in the folded frequency spectrum (typically, negative D, F*, and  ). Computation of the standard neutrality tests shows a deficit of low-frequency polymorphism rather than an excess. This deficit is even often significant (Table 3). This is clearly caused by the ascertainment bias in the data set. Because the polymorphisms were first screened in a small group and further genotyped in larger groups, rare variants are underrepresented (e.g., Kuhner et al. 2000; Clark et al. 2005). This ascertainment bias has been subject to various corrections (e.g., Wakeley et al. 2001; Nielsen et al. 2004). To avoid any correction, I computed a

). Computation of the standard neutrality tests shows a deficit of low-frequency polymorphism rather than an excess. This deficit is even often significant (Table 3). This is clearly caused by the ascertainment bias in the data set. Because the polymorphisms were first screened in a small group and further genotyped in larger groups, rare variants are underrepresented (e.g., Kuhner et al. 2000; Clark et al. 2005). This ascertainment bias has been subject to various corrections (e.g., Wakeley et al. 2001; Nielsen et al. 2004). To avoid any correction, I computed a  test where the weights of both

test where the weights of both  and

and  vectors were set to 0 for i < 8. The remaining two vectors were computed using

vectors were set to 0 for i < 8. The remaining two vectors were computed using  and

and  . As a consequence, this test is D-like in that it considers only polymorphisms with frequencies in the range [0.09, 0.91]. This is reminiscent of ignoring the singletons data set where sequencing errors are suspected (Achaz 2008). Results (Table 3) show that this test significantly deviates from the standard model for the CEU population. Ignoring fewer polymorphisms (e.g., only the 5% that are of low frequency) or changing the minimum sample size leads to similar results (data not shown).

. As a consequence, this test is D-like in that it considers only polymorphisms with frequencies in the range [0.09, 0.91]. This is reminiscent of ignoring the singletons data set where sequencing errors are suspected (Achaz 2008). Results (Table 3) show that this test significantly deviates from the standard model for the CEU population. Ignoring fewer polymorphisms (e.g., only the 5% that are of low frequency) or changing the minimum sample size leads to similar results (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Neutrality tests in the lactase region

| Population | D | D2* | F * |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEU | −0.16 | 0.81 | 0.48 | −1.79* |

| CHB | 2.04* | 1.97** | 2.29* | 0.25 |

| JPT | 0.92 | 2.22** | 1.93* | 0.28 |

| YRI | 1.00 | 2.18** | 1.94* | −0.04 |

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Here I developed a unifying framework for θ-estimators on the basis of the frequency spectrum. Namely, all known estimators of θ are linear combinations of  (or

(or  ). Because neutrality tests based on the frequency spectrum are simple functions of these θ-estimators, the framework can be used to derive them. All tests (of this family) proposed so far are embedded in the framework. Using the model, I have shown that estimators of θ based on a folded spectrum always have an unfolded equivalent. The reciprocal, however, is not true.

). Because neutrality tests based on the frequency spectrum are simple functions of these θ-estimators, the framework can be used to derive them. All tests (of this family) proposed so far are embedded in the framework. Using the model, I have shown that estimators of θ based on a folded spectrum always have an unfolded equivalent. The reciprocal, however, is not true.

Besides its unifying appeal, the model developed here can be used in several ways. First, I showed how it can be used to compute the variance of all estimators of θ and consequently of statistics such as  . All variances of all estimators can be computed either using this framework or from their previous derived analytical formula. The same should be true for all t. Importantly, the computation of f, f *, y, and y* revealed differences between both methods. Simulations demonstrate that the previous formulas were not correct while the new ones are. Besides a minor error in the f and f * variance (corrected in Simonsen et al. 1995), it appears that the Cov[π, ξ1] that was derived by Fu and Li (1993b) is inexact. Therefore the variances of f and f * (Fu and Li 1993b) as well as the variances of y and y* (Achaz 2008) that were using this covariance carried along the error. Framed within the model presented here, all variances are correct. Finally, it can be used to compute the variance of h that was not given by the authors (Fay and Wu 2000).

. All variances of all estimators can be computed either using this framework or from their previous derived analytical formula. The same should be true for all t. Importantly, the computation of f, f *, y, and y* revealed differences between both methods. Simulations demonstrate that the previous formulas were not correct while the new ones are. Besides a minor error in the f and f * variance (corrected in Simonsen et al. 1995), it appears that the Cov[π, ξ1] that was derived by Fu and Li (1993b) is inexact. Therefore the variances of f and f * (Fu and Li 1993b) as well as the variances of y and y* (Achaz 2008) that were using this covariance carried along the error. Framed within the model presented here, all variances are correct. Finally, it can be used to compute the variance of h that was not given by the authors (Fay and Wu 2000).

One potentially interesting development is to find an ω-vector that minimizes variance of the associated estimator of θ. This problem was previously addressed thoroughly (Felsenstein 1992a,b; Fu and Li 1993a; Fu 1994a,b). Indeed, it was shown that phylogenetic estimates have lower variance than estimators based on summary statistics (Felsenstein 1992b; Fu and Li 1993a; Fu 1994b). Moreover, Fu (1994a,b) proposed a general method to find weight vectors that minimize the variance of the estimators and showed that the best vector actually depends on the value of θ itself. Nonetheless, it remains true that some estimators have less variance than others (i.e.,  vs.

vs.  ), whatever is the value of θ. This latter observation suggests that re-exploring this question of minimizing the variance may be of interest.

), whatever is the value of θ. This latter observation suggests that re-exploring this question of minimizing the variance may be of interest.

Nawa and Tajima (2008) recently proposed to use the  spectrum instead of the classical frequency spectrum as a visual test for neutrality. This can be extended to the unfolded

spectrum instead of the classical frequency spectrum as a visual test for neutrality. This can be extended to the unfolded  spectrum if an outgoup is available. The study presented here fully supports this idea. The visual inspection of the

spectrum if an outgoup is available. The study presented here fully supports this idea. The visual inspection of the  spectrum indicates why some tests will reject neutrality. Contrary to what intuition may suggest, when one is interested in θ-estimation, the appropriate representation for weight vectors is the

spectrum indicates why some tests will reject neutrality. Contrary to what intuition may suggest, when one is interested in θ-estimation, the appropriate representation for weight vectors is the  -vector as defined above rather than weights on the ξi themselves (or on the ηi as in Tajima 1997).

-vector as defined above rather than weights on the ξi themselves (or on the ηi as in Tajima 1997).

When an outgroup is used to unfold the spectrum, the choice of the appropriate outgoup is of critical importance. If the outgroup is not adequate (too distant or too close), misoriented sites will have a disastrous effect on θ-estimations and therefore on related neutrality tests (Baudry and Depaulis 2003). This adds to the difficulty of using tests based on the full ξ-spectrum. However, when low and high frequencies can be sorted apart, much power is gained in terms of choosing the adequate evolutionary scenario. For example, no high frequencies are overrepresented under recent growth or severe bottlenecks.

Specific problems that concern only some area of the spectrum can be handled easily by setting to 0 all weights in the suspicious area. For example, the sequencing errors can be avoided when the singletons are ignored (Achaz 2008). With the current framework, by ignoring the low-frequency polymorphisms, the ascertainment bias can be overcome and the pattern expected from selection at the lactase gene appears. This strategy has endless extensions as long as we have some prior knowledge of the suspicious area.

Finally, I think that this framework opens the door for new estimations of θ and the related neutrality tests. Using simple examples, I show how the power of neutrality tests can easily be improved to detect deviations from the standard model. To optimize the power of the future new tests, one could (1) minimize their variance under the standard model, (2) select their area of sensitivity on the basis of prior knowledge of the impact of specific deviations, and (3) use recombination estimates to compute smaller confidence intervals (Wall 1999) (because recombination results in quasi-independent replicates that lower the variance of the θ-estimators). By building specific tests that will be sensitive to specific deviations, one could envision how several selected tests will be able to help the population geneticist to choose between different possible scenarios for a given data set. Another interesting alternative would be to use the different θ-estimators as summary statistics to infer the best parameters for a given evolutionary scenario (e.g., using ABC analysis).

The source code for this study was designed as a C++ library for the simulations and a C library for sequence analysis and is available upon request. A dedicated web version of the tests is available at http://wwwabi.snv.jussieu.fr/achaz/neutralitytest.html. Furthermore, the tests will be incorporated in a future release of DNAsp.

Acknowledgments

I thank F. Tajima, E. P. C. Rocha, J. Wakeley, P. Nicolas, and D. Higuet for their interesting comments on the manuscript and T. Treangen for English language improvement. I also thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. This work was supported by grant 07-GMGE-004-04 from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche.

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.109.104042/DC1.

References

- Achaz, G., 2008. Testing for neutrality in samples with sequencing errors. Genetics 179: 1409–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry, E., and F. Depaulis, 2003. Effect of misoriented sites on neutrality tests with outgroup. Genetics 165: 1619–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersaglieri, T., P. C. Sabeti, N. Patterson, T. Vanderploeg, S. F. Schaffner et al., 2004. Genetic signatures of strong recent positive selection at the lactase gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74: 1111–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A. G., M. J. Hubisz, C. D. Bustamante, S. H. Williamson and R. Nielsen, 2005. Ascertainment bias in studies of human genome-wide polymorphism. Genome Res. 15: 1496–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depaulis, F., and M. Veuille, 1998. Neutrality tests based on the distribution of haplotypes under an infinite-site model. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15: 1788–1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depaulis, F., S. Mousset and M. Veuille, 2001. Haplotype tests using coalescent simulations conditional on the number of segregating sites. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18: 1136–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay, J. C., and C. I. Wu, 2000. Hitchhiking under positive Darwinian selection. Genetics 155: 1405–1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J., 1992. a Estimating effective population size from samples of sequences: a bootstrap Monte Carlo integration method. Genet. Res. 60: 209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J., 1992. b Estimating effective population size from samples of sequences: inefficiency of pairwise and segregating sites as compared to phylogenetic estimates. Genet. Res. 59: 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y. X., 1994. a Estimating effective population size or mutation rate using the frequencies of mutations of various classes in a sample of DNA sequences. Genetics 138: 1375–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y. X., 1994. b A phylogenetic estimator of effective population size or mutation rate. Genetics 136: 685–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y. X., 1995. Statistical properties of segregating sites. Theor. Popul. Biol. 48: 172–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y. X., 1996. New statistical tests of neutrality for DNA samples from a population. Genetics 143: 557–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y. X., 1997. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations against population growth, hitchhiking and background selection. Genetics 147: 915–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y. X., and W. H. Li, 1993. a Maximum likelihood estimation of population parameters. Genetics 134: 1261–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y. X., and W. H. Li, 1993. b Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations. Genetics 133: 693–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, R. R., 1993. The how and why of generating gene genealogies, pp. 23–36 in Mechanism of Molecular Evolution. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- Kuhner, M. K., P. Beerli, J. Yamato and J. Felsenstein, 2000. Usefulness of single nucleotide polymorphism data for estimating population parameters. Genetics 156: 439–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markovtsova, L., P. Marjoram and S. Tavaré, 2001. On a test of Depaulis and Veuille. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18: 1132–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawa, N., and F. Tajima, 2008. Simple method for analyzing the pattern of DNA polymorphism and its application to SNP data of human. Genes Genet. Syst. 83: 353–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, R., and J. Wakeley, 2001. Distinguishing migration from isolation: a Markov chain Monte Carlo approach. Genetics 158: 885–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, R., M. J. Hubisz and A. G. Clark, 2004. Reconstituting the frequency spectrum of ascertained single-nucleotide polymorphism data. Genetics 168: 2373–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, R., S. Williamson, Y. Kim, M. J. Hubisz, A. G. Clark et al., 2005. Genomic scans for selective sweeps using SNP data. Genome Res. 15: 1566–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Onsins, S. E., and J. Rozas, 2002. Statistical properties of new neutrality tests against population growth. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19: 2092–2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Onsins, S. E., S. Mousset, T. Mitchell-Olds and W. Stephan, 2007. Population genetic inference using a fixed number of segregating sites: a reassessment. Genet. Res. 89: 231–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen, K. L., G. A. Churchill and C. F. Aquadro, 1995. Properties of statistical tests of neutrality for DNA polymorphism data. Genetics 141: 413–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima, F., 1983. Evolutionary relationship of DNA sequences in finite populations. Genetics 105: 437–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima, F., 1989. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123: 585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima, F., 1997. Estimation of the amount of DNA polymorphism and statistical tests of the neutral mutation hypothesis based on DNA polymorphism, pp. 149–164 in Progess in Population Genetics and Human Evolution. Springer-Verlag, Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany/New York.

- Tishkoff, S. A., F. A. Reed, A. Ranciaro, B. F. Voight, C. C. Babbitt et al., 2007. Convergent adaptation of human lactase persistence in Africa and Europe. Nat. Genet. 39: 31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeley, J., 2009. Coalescent Theory, an Introduction. Roberts and Company. Greenwood Village, Colorado.

- Wakeley, J., R. Nielsen, S. N. Liu-Cordero and K. Ardlie, 2001. The discovery of single-nucleotide polymorphisms–and inferences about human demographic history. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69: 1332–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall, J. D., 1999. Recombination and the power of statistical tests of neutrality. Genet. Res. 74: 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, J. D., and R. R. Hudson, 2001. Coalescent simulations and statistical tests of neutrality. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18: 1134–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watterson, G. A., 1975. On the number of segregating sites in genetical models without recombination. Theor. Popul. Biol. 7: 256–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]