Summary

The entorhinal cortex provides both direct and indirect inputs to hippocampal CA1 neurons through the perforant path and Schaffer collateral synapses, respectively. Using both two-photon imaging of synaptic vesicle cycling and electrophysiological recordings, we found that the efficacy of transmitter release at perforant path synapses is lower than at Schaffer collateral inputs. This difference is due to the greater contribution to release by presynaptic N-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels at the Schaffer collateral than perforant path synapses. Induction of long-term potentiation that depends on activation of NMDA receptors and L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels enhances the low efficacy of release at perforant path synapses by increasing the contribution of N-type channels to exocytosis. This represents a novel presynaptic mechanism for fine-tuning release properties of distinct classes of synapses onto a common postsynaptic neuron and for regulating synaptic function during long-term synaptic plasticity.

Introduction

The hippocampus and medial temporal lobe are part of a neural circuit that is essential for the formation and storage of episodic memory (Eichenbaum, 2000). In this circuit the entorhinal cortex (EC) relays polymodal sensory information via two parallel excitatory inputs to CA1 pyramidal neurons, the major output of the hippocampus. Direct information from EC is relayed by layer III neurons, which project through the perforant path (PP) to the CA1 neuron distal apical dendrites in stratum lacunosum-moleculare (SLM). Indirect information is relayed through the trisynaptic pathway, in which layer II EC neurons project to dentate gyrus granule neurons, which excite CA3 pyramidal neurons, which then form synapses onto the CA1 neuron proximal apical dendrites in stratum radiatum (SR) through the Schaffer collateral (SC) pathway.

Long-term potentiation (LTP) of synaptic transmission throughout the trisynaptic pathway has been widely implicated in spatial learning and memory (Pastalkova et al., 2006). However, much less is known about the properties and plastic mechanisms of the direct PP synapses onto CA1 neurons. Although these synapses do exhibit LTP (Golding et al., 2002; Nolan et al., 2004; Remondes and Schuman, 2002), the molecular and synaptic mechanisms underlying this plasticity have not been characterized. This information is required to understand the emerging role of these inputs in regulating CA1 neuron output (Ang et al., 2005; Dudman et al., 2007; Jarsky et al., 2005; Remondes and Schuman, 2002; Takahashi and Magee, 2009) and in hippocampal-dependent memory storage (Brun et al., 2008; Brun et al., 2002; Nakashiba et al., 2008; Nolan et al., 2004; Remondes and Schuman, 2004).

The presence of converging glutamatergic PP and SC inputs onto a common CA1 postsynaptic neuron also raises the question whether the presynaptic properties of these synapses are similar or distinct. This question is of further interest as the postsynaptic membrane at PP synapses has a lower density of AMPA receptors compared to the SC synapses (Nicholson et al., 2006). Do the PP presynaptic terminals help counteract this postsynaptic difference by having a higher efficacy of vesicle release in response to a presynaptic action potential? What are the mechanisms of expression of PP LTP and how do they compare to SC LTP? Is PP LTP expressed purely postsynaptically (Kerchner and Nicoll, 2008), or is there also a presynaptic component of expression, similar to that observed for some forms of plasticity at SC synapses (Bayazitov et al., 2007; Choi et al., 2000; Enoki et al., 2009; Ward et al., 2006; Zakharenko et al., 2003; Zakharenko et al., 2001)? Such questions are important as presynaptic properties determine not only the strength of synaptic excitation but also influence the temporal dynamics with which synapses filter their inputs (Abbott and Regehr, 2004; Maass and Zador, 1999).

To address these questions, we examined the presynaptic properties of the PP to CA1 synapses and compared them to the properties of the SC synapses, under both basal conditions and following induction of PP LTP. Because the very thin apical dendrites prevent direct intracellular recordings, we relied on two-photon imaging of FM 1-43 fluorescence as an indicator of synaptic vesicle cycling (Betz and Bewick, 1992) and electrophysiological measurements of extracellular field EPSPs (fEPSPs). Our results reveal unique release properties of the PP versus SC terminals and demonstrate a previously unknown mechanism for enhancing presynaptic function of the PP inputs during LTP.

Results

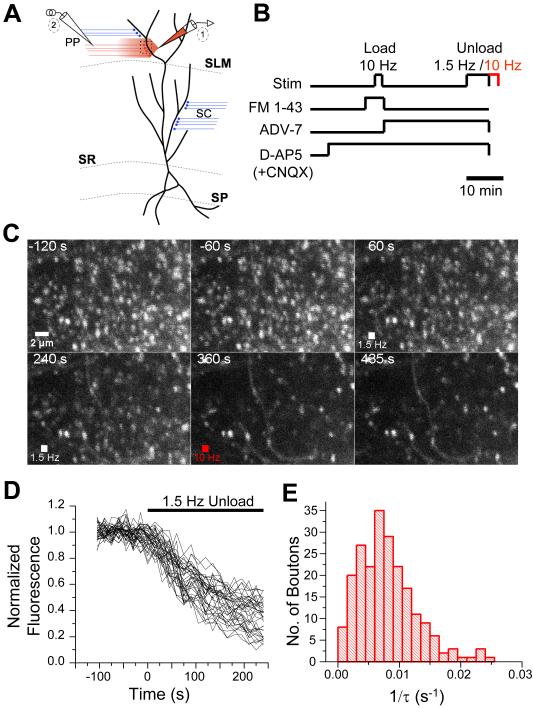

Presynaptic function at the PP inputs onto CA1 neurons in acute hippocampal slices from adult mice was assayed by imaging FM 1-43 fluorescence during synaptic stimulation (Betz and Bewick, 1992). Dye was first iontophoretically injected into a focal region of the slice from a patch pipette and then loaded into PP presynaptic terminals using a 2 min train of 10 Hz electrical stimulation to induce synaptic vesicle exocytosis and dye uptake through subsequent endocytosis (see Figure 1A,B and Experimental Procedures). Following FM 1-43 loading, slices were bathed with the cyclodextrin ADVASEP-7 to remove residual extracellular dye (Kay et al., 1999; Zakharenko et al., 2001), revealing bright spherical fluorescent puncta under observation with two-photon microscopy (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Two-photon imaging of FM 1-43 dye uptake and release at PP presynaptic terminals in acute hippocampal slices.

(A) Experimental set-up and CA1 architecture. One electrode (labeled ‘1’) was used both for fEPSP recordings and FM 1-43 delivery and was placed in the inner half of stratum lacunosum moleculare (SLM). A stimulating electrode (labeled ‘2’), placed in SLM > 200 μm from the recording electrode, was used to elicit PP fEPSPs and to load and unload dye from PP presynaptic boutons. Dashed box shows approximate imaging field. In experiments on SC synapses we used a similar arrangement but placed the recording (FM 1-43) and stimulating electrodes in stratum radiatum (SR) (not shown). (B) Protocol for assaying FM 1-43 release. Terminals were loaded with dye by a 2 min period of 10 Hz stimulation of PP inputs in presence of D-AP5 (50 μM) (and 10 μM CNQX in some experiments). ADVASEP-7 (ADV-7) was then applied to remove extracellular FM 1-43. Next, PP inputs were stimulated at 1.5 Hz for 4 min and then at 10 Hz for 2 min to release dye from terminals (Unload). (C) Two-photon images of fluorescent puncta in SLM loaded with FM 1-43 before (-120 s and -60 s), during (60 s, 240 s and 360 s), and after (435 s) unloading stimulation. Unloading started at 0 s. During 240-360 s interval, terminals were maximally destained with 10 Hz stimulation. (D) Time course of normalized FM 1-43 fluorescence intensity of individual boutons during 1.5 Hz unloading stimulation from experiment in C. (E) Histogram of FM 1-43 destaining rates (1/τ) from individual terminals in SLM (N=218 boutons, 5 slices). See Experimental Procedures for details.

In the absence of further PP stimulation, puncta fluorescence was stable over the course of several hours (>90% of initial fluorescence). However, subsequent stimulation of the PP at 1.5 Hz evoked a second round of vesicle exocytosis that caused greater than 80-90% of puncta to release FM 1-43, leading to a significant loss (~15-100%) of fluorescence intensity over several minutes (Figure 1D). The time course of fluorescence decay in each bouton was well fit by a single exponential function, reflecting the first order kinetics of vesicle release from presynaptic terminals (Liu and Tsien, 1995). The exponential time constant of dye loss was then converted to a rate of FM 1-43 destaining (1/τ), which has been shown to provide a reliable index of the probability of vesicle release (Pr) from SC terminals (Zakharenko et al., 2001). Dye release rate among individual PP terminals showed a broad distribution (Figure 1E), presumably reflecting a variability in Pr.

We next confirmed that the rate of dye loss provides a suitable assay for the efficacy of presynaptic release at PP synapses by showing that two manipulations known to enhance Pr produced corresponding changes in the rate of FM 1-43 release. First we found that an increase in Pr caused by elevating extracellular [Ca2+] produced a similar increase in the rate of dye destaining (Figure S1). Second, we found that an increase in Pr in response to the adenosine receptor antagonist 8-(p-sulfophenyl) theophylline (8-PST; 40 μM), which enhances release by relieving tonic presynaptic inhibition caused by basal levels of adenosine (Qian and Noebels, 2001; Yoon and Rothman, 1991), increased the fEPSP and produced a > two-fold enhancement in the rate of FM 1-43 destaining from the PP terminals (Figure S2), in agreement with results for SC terminals (Zakharenko et al., 2001).

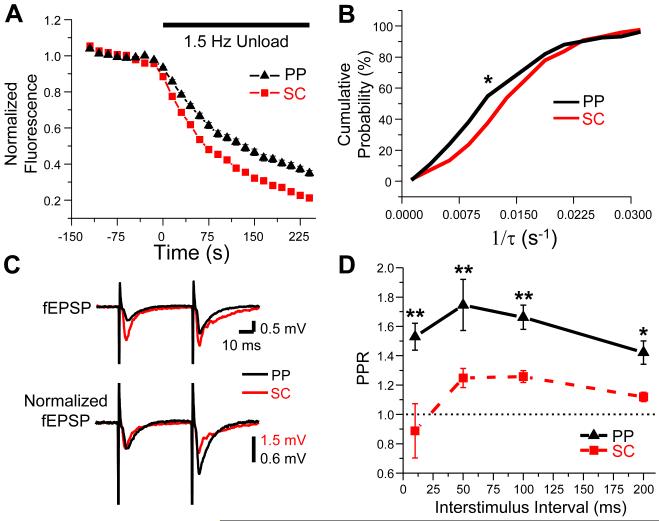

PP terminals on CA1 neurons have a lower efficacy of vesicle release compared to SC terminals

To determine whether the efficacy of release from the PP and SC terminals onto their common postsynaptic CA1 neuron target is similar, we compared the kinetics of FM 1-43 destaining at the two inputs (Figure 2A,B). Surprisingly, the mean rate of dye release from SC terminals (0.01575 ± 0.0013 s-1; N=276 boutons, 6 slices) was nearly two-fold faster than the rate of release from PP terminals (0.00811 ± 0.0047 s-1; N=133 boutons, 4 slices; P<0.01, unpaired t-test). There was also a shift in the cumulative distribution of destaining rates of individual terminals to higher values for SC synapses relative to PP inputs (Figure 2B; P=0.001, Kolmogorov-Smirnov two sample [K-S] test). Thus, PP synapses appear to have a lower efficacy of vesicle release than do the SC inputs.

Figure 2. PP synapses exhibit slower kinetics of FM 1-43 release and larger paired-pulse facilitation compared to SC synapses.

(A) Mean time course of FM 1-43 destaining for PP (black triangles) and SC (red squares) terminals. Error bars (SEM in all figures) are shown and are smaller than symbols for most points. (B) Cumulative probability histograms of FM 1-43 destaining rates (1/τ) from individual PP (black, N=133 boutons, 4 slices) and SC (red, N=276 boutons, 6 slices) terminals differ significantly (P=0.001, K-S test). (C) fEPSPs elicited by paired-pulse stimulation (50 ms ISI) of PP (black) and SC (red) inputs, recorded in SLM and SR, respectively. Top, average fEPSP from 3 consecutive sweeps. Bottom, average fEPSPs normalized to the peak of the first fEPSP of each pair to better show facilitation during second fEPSP. (D) Mean paired-pulse ratio (PPR = fEPSP2/fEPSP1) of PP (black triangles, n=9 slices) and SC (red squares, n=8 slices) inputs across a range of ISIs. Asterisks indicate significant differences (double asterisk, P<0.001; single asterisk, P<0.01; unpaired t-test).

Although the fields that we imaged contained both glutamatergic and GABAergic terminals, the latter account for less than 15% of terminals in SLM (Megias et al., 2001) and less than 2.5% of inputs in SR (Hiscock et al., 2000), indicating that our imaging results should largely reflect release from excitatory inputs. This view is supported by the above finding that the adenosine receptor antagonist increased the rate of FM 1-43 destaining in both SLM (Figure S2) and SR (Zakharenko et al., 2001), as adenosine selectively inhibits release from glutamatergic terminals (Cunha and Ribeiro, 2000; Yoon and Rothman, 1991).

To confirm the imaging results and provide a selective measure of release efficacy at excitatory synapses, we compared the magnitude of paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) of PP versus SC fEPSPs, using GABAA and GABAB receptor antagonists to block inhibitory synaptic transmission (see Experimental Procedures). Generally, the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) is thought to be inversely related to release probability, so that a larger PPR is indicative of a lower Pr, and vice versa (Zucker and Regehr, 2002). Consistent with the idea that PP synapses have a lower release efficacy than SC synapses, the perforant path fEPSPs showed much larger PPR compared to SC fEPSPs, across a range of interstimulus intervals (ISIs) (Figure 2C-D). At a 50 ms ISI, where we obtained maximal PPF, the perforant path inputs (n=9) showed a 40 ± 3% larger PPR than did the SC inputs (n=8; P<0.001, unpaired t-test). Although PPF is an indirect measure of release efficacy and can be complicated by postsynaptic effects or presynaptic changes not related to initial release probability, for example, due to inactivation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Zucker and Regehr, 2002), the agreement of the PPF data with our FM 1-43 imaging results provides strong evidence that the efficacy of vesicle release at PP inputs is indeed lower than that at SC inputs.

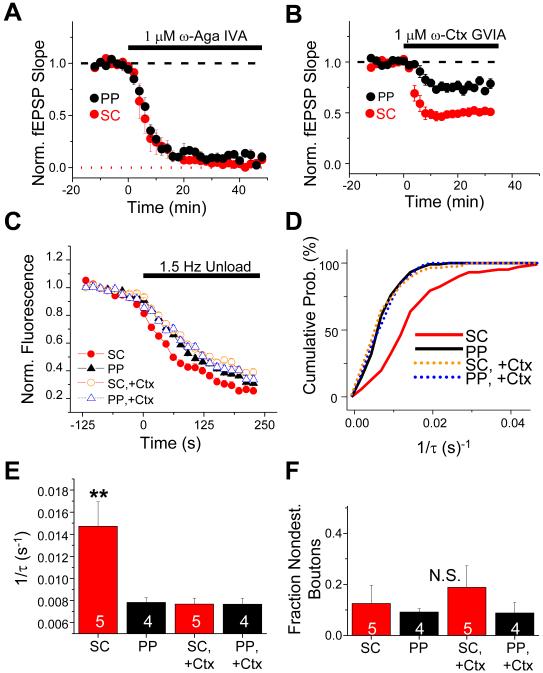

Lower contribution of N-type Ca2+ channels to release at PP versus SC inputs accounts for differences in efficacy of release

What molecular mechanisms might underlie the differences in presynaptic function between these two inputs? Previous studies have found that transmitter release at SC synapses depends largely on presynaptic Ca2+ entry through both P/Q-type and N-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) (Qian and Noebels, 2000; Wheeler et al., 1994). In contrast, transmission at perforant path inputs from layer II neurons of entorhinal cortex onto dentate gyrus granule neurons is mediated primarily by presynaptic P/Q-type channels (Qian and Noebels, 2001). Might the lower efficacy of release at PP inputs from layer III EC neurons onto CA1 neurons result from a low contribution of N-type channels to release?

To address this question we examined the relative importance of P/Q-type versus N-type channels for release at SC and PP synapses using specific toxins (Figure 3). Selective blockade of P/Q channels with 1 μM ω-Agatoxin IVA (ω-Aga IVA) resulted in a nearly complete block (~90-95%) of synaptic transmission at both SC (n=4) and PP (n=6) inputs (no significant difference in degree of block between inputs; P=0.86, unpaired t-test; Figure 3A). In contrast, selective blockade of N-type channels with 1 μM ω-Conotoxin GVIA (ω-Ctx GVIA) resulted in a significantly greater block of the SC fEPSP (49.2 ± 3% block; n=15) compared to the PP fEPSP (24.4 ± 3% block; n=14; P<0.00001, unpaired t-test; Figure 3B), suggesting that N-type channels preferentially contribute to release at SC synapses, although P/Q-type channels are the predominant Ca2+ source at both synapses (see pXXX of Discussion for a quantitative analysis of the relative contributions of these channels to release).

Figure 3. Differences in presynaptic function between PP and SC synapses are due to a differential contribution of N-type Ca2+ channels to release.

(A) Time course of mean normalized PP (black symbols, n=6 slices) and SC (red symbols, n=4 slices) fEPSP slope during block of P/Q-type channels with 1 μM ω-Aga IVA. (B) Time course of mean normalized PP (black symbols, n=14 slices) and SC (red symbols, n=15 slices) fEPSP slope during block of N-type channels with 1 μM ω-Ctx GVIA. (C) Mean time course of FM 1-43 destaining from PP and SC terminals under control conditions (PP: black filled triangles; SC: red filled circles) and with 1 μM ω-Ctx GVIA present during unloading (PP: blue open triangles; SC: orange open circles). (D) Cumulative probability histograms of FM 1-43 destaining rates (1/τ) under control conditions for PP (solid black line, n=116 boutons) and SC terminals (solid red line, n=102 boutons) and in presence of 1 μM ω-Ctx GVIA for PP (dotted blue line, n=86 boutons) and SC terminals (dotted orange line, n=114 boutons). (E) Mean rates of FM 1-43 destaining (1/τ) under the conditions in panels C, D. Asterisks, significant difference compared to PP control group (P<0.002, ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc pairwise comparisons). (F) Mean fraction of nondestaining boutons per microscopic field of view under conditions of panels C, D. Differences between groups are not significant (P=0.68; ANOVA). Number of slices in each group is shown in data bars.

To explore the presynaptic contributions of N-type channels more directly, we examined the effects of the toxins on the kinetics of FM 1-43 release. We first loaded PP or SC terminals with dye in the absence of toxin. Next we applied ω-Ctx GVIA to block the N-type channels and measured the kinetics of FM 1-43 release during synaptic stimulation. As illustrated in Figure 3C-E, the toxin caused a significant, ~two-fold decrease in the FM 1-43 destaining rate at SC terminals, from 0.01472 ± 0.0022 s-1 (N = 102 boutons, 5 slices) in the absence of toxin to 0.00768 ± 0.0005 s-1 (N =114 boutons, 5 slices) in the presence of toxin (P<0.002, ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis for all comparisons). In contrast, ω-Ctx GVIA had no effect on dye release kinetics at the PP synapses, with a destaining rate of 0.00783 ± 0.0004 s-1 (N = 116 boutons, 4 slices) in the absence of toxin versus 0.00765 ± 0.0005 s-1 (N = 86 boutons, 4 slices) in the presence of toxin (P>0.9). Importantly, the toxin did not alter the fraction of dye-loaded SC or PP terminals that failed to destain during synaptic stimulation (Figure 3F; P=0.68, ANOVA), indicating the absence of a subpopulation of terminals that relied solely on N-type channels for release.

These imaging results demonstrate that N-type channels normally make only a small contribution to vesicle release at PP terminals whereas they make a significant contribution to release at SC terminals. Importantly, when N-type channels were blocked, the rate of FM 1-43 destaining was virtually identical at the SC (0.00768 s-1) and PP inputs (0.00765 s-1; P>0.9). Thus, the enhanced efficacy of release at SC synapses relative to PP synapses may be largely due to the greater contribution of N-type channels to exocytosis at the SC synapses.

To explore further the relative importance of N-type channels to release at SC versus PP synapses, we compared the effects of ω-Ctx GVIA on PPF at these two inputs. Application of the toxin had no effect on PPF (50 ms ISI) at perforant path inputs (PPR was equal to 2.21 ± 0.1 in absence of toxin versus 2.22 ± 0.1 in presence of toxin; n=8; P=0.84, paired t-test). In contrast, the toxin significantly increased the amount of facilitation at SC inputs, consistent with a decrease in release probability (PPR was equal to 1.49 ± 0.1 in absence of toxin versus 1.79 ± 0.1 in presence of toxin; n=14; P=0.00005, paired t-test). These results provide independent support for the view that N-type channels make a significantly larger contribution to release at the SC synapses than at the PP synapses (see pYYY of Discussion as to why ω-Ctx GVIA produced a ~25% block in the PP fEPSP but failed to alter FM 1-43 release or PPF).

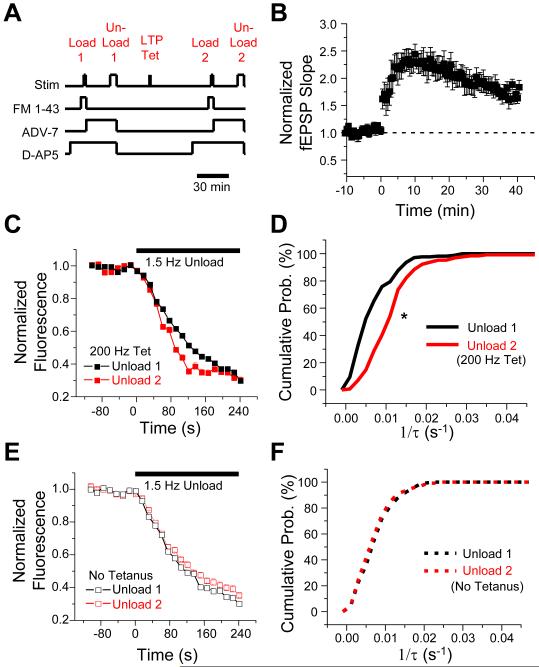

Induction of LTP at PP inputs enhances efficacy of vesicle release

Given our finding that basal presynaptic efficacy is low at PP terminals, we wondered whether release at these terminals could be enhanced by a 200 Hz tetanic stimulation protocol known to induce a presynaptic component of LTP at SC inputs that depends on both NMDARs and L-type VGCCs (Bayazitov et al., 2007; Zakharenko et al., 2003; Zakharenko et al., 2001). We therefore compared the kinetics of FM 1-43 release measured before and after induction of 200 Hz LTP (see protocol in Figure 4A). The 200 Hz tetanization gave rise to a robust LTP of the PP fEPSP, leading to a 71.0 ± 10% (n=5) potentiation above baseline ~40-45 min post-tetanus (Figure 4B). Importantly, the induction of LTP also led to a significant enhancement in the rate of FM 1-43 release, as seen by several measures (Figure 4C,D; Figure 5).

Figure 4. LTP induced at PP synapses with 200 Hz tetanization enhances the kinetics of FM 1-43 release.

(A) Protocol showing periods of PP stimulation, FM 1-43 iontophoresis, and applications of ADVASEP-7 and D-AP5. (B) Time course of LTP induced with 200 Hz tetanus protocol (protocol lasted 50 s starting at time 0). Mean normalized fEPSP slope is plotted between Unload 1 and Load 2 periods in A (n=5 slices). (C) Mean FM 1-43 destaining time course measured ~40 min before (Unload 1, black squares; averaged from 176 boutons from 5 slices) and ~80-90 min after induction of LTP (Unload 2, red squares; averaged from 129 individual boutons from the same 5 slices). (D) Cumulative probability histograms of FM 1-43 destaining rates of individual boutons (1/τ) before (black trace, n = 176 boutons) and after (red trace, n = 129 boutons) induction of LTP differ significantly (P<0.001; K-S test). FM 1-43 data in C,D is from same experiments shown in B. (E) Time course of average FM 1-43 destaining in interleaved, non-tetanized control experiments (n=5 slices; Unload 1, open black squares; Unload 2, open red squares). (F) Cumulative probability histograms of FM 1-43 destaining rates in non-tetanized, control experiments showed no significant difference between Unload 1 (black trace, n=229 boutons) and Unload 2 (red trace, n=130 boutons; P=0.38; K-S test).

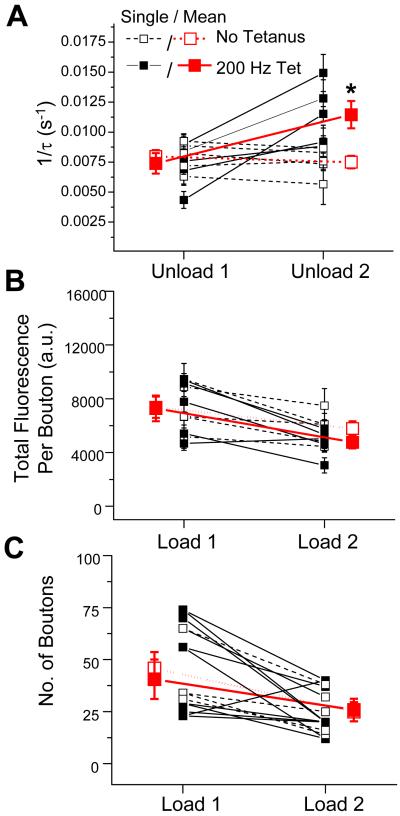

Figure 5. Data from individual slices show that LTP enhances the kinetics of FM 1-43 release without altering vesicle pool size or number of dye-loaded terminals.

For all panels, small symbols show average data for boutons from individual slices (same microscopic field in Unload 1 and Unload 2); large symbols show mean data from all slices in each group. (A) Effect of 200 Hz tetanic stimulation on FM 1-43 destaining rates (1/τ). Filled squares, experiments where 200 Hz tetanus was applied after Unload 1. Open squares, interleaved control experiments where no tetanus was delivered. Significant differences were only seen between Unload 1 and Unload 2 destaining rates for tetanized slices (P<0.02; paired t-test). (B) Mean total fluorescence intensity per bouton, a measure of recycling vesicle pool size, with (filled symbols) or without (open symbols) 200 Hz tetanus after Load 1. Fluorescence intensity between Load 1 and Load 2 was not altered by tetanus (P=0.28; unpaired t-test). (C) The total number of boutons that load with dye with (filled symbols) or without (open symbols) delivery of tetanus after Load 1. Number of boutons loaded with dye was not altered by tetanus (P=0.91; unpaired t-test).

First, we found that the mean time course of FM 1-43 fluorescence decay in response to synaptic stimulation after the induction of LTP was more rapid than the destaining time course obtained prior to induction of LTP in the same slices (Figure 4C). Second, the cumulative distribution of destaining kinetics of individual PP boutons was shifted to significantly higher rates of release after the 200 Hz tetanus (Figure 4D; P<0.001, K-S test). In contrast, destaining kinetics determined at similar time intervals in interleaved, non-tetanized control slices (n=5) were relatively constant (Figure 4E-F; P=0.38, K-S test; before LTP, n=229 boutons; after LTP, n=130 boutons). Third, a comparison of mean FM 1-43 release rates from boutons in the same optical field in individual slices before and after 200 Hz tetanization demonstrated an increase in the rate of FM 1-43 release after induction of LTP in all five experiments (Figure 5A). On average, there was a ~55% enhancement in the mean destaining rate after the 200 Hz stimulation, from 0.00740 ± 0.0008 s-1 before LTP (Unload 1) to 0.01145 ± 0.0011 s-1 after LTP (Unload 2; P<0.02, paired t-test). In contrast, there was no significant change in destaining rate at comparable time points in the non-tetanized control slices (Unload 1: 1/τ= 0.00797 ± 0.0004 s-1 vs. Unload 2: 1/τ= 0.00750 ± 0.0002 s-1; P>0.10, paired t-test, n=5). Thus, the long-term enhancement in dye release kinetics was a specific effect of the tetanization and not due to a time-dependent drift in release properties.

In addition to increasing release kinetics, does LTP enhance the size of the recycling vesicle pool or augment the number of functional release sites? To address these questions, we measured, respectively, the absolute fluorescence intensity of the boutons after maximal dye loading (which is proportional to vesicle pool size) and the total number of terminals that actively took up and released dye with PP stimulation. Similar to previous findings at SC inputs (Zakharenko et al., 2001), induction of LTP at PP inputs selectively enhanced the FM 1-43 release kinetics, with no increase in the total fluorescence per bouton (Figure 5B; P=0.28, unpaired t-test) or number of actively cycling presynaptic terminals (Figure 5C; P=0.91, unpaired t-test).

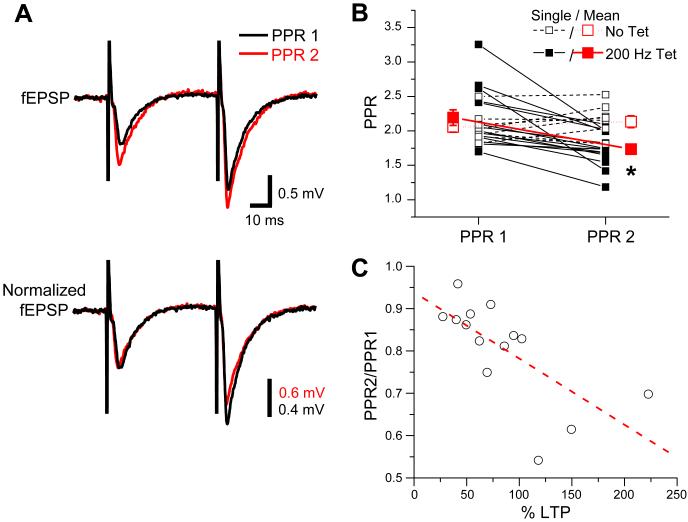

Independent evidence for enhanced presynaptic efficacy during LTP comes from an examination of PPF, whereby we found that the 200 Hz tetanus led to a reliable decrease in the magnitude of the PPR in all slices (14/14) tested (Figure 6A,B; pre-tetanus PPR: 2.19 ± 0.1; post-tetanus PPR: 1.74 ± 0.1; P<0.05, paired t-test). Furthermore, the change in PPR was linearly correlated with the magnitude of LTP (Figure 6C; P<0.01, R=-0.7, Pearson’s linear regression; see also Figure S4B). In contrast, there was no significant change in PPR in interleaved, non-tetanized control slices (n=8; P=0.24, paired t-test).

Figure 6. Induction of LTP with 200 Hz tetanization decreases paired-pulse facilitation.

(A) PP fEPSPs elicited by paired-pulse stimulation with 50 ms ISI ~15 min before (PPR 1, black traces) and ~40 min after (PPR 2, red traces) induction of LTP. Top traces, average fEPSPs from 5 consecutive sweeps. Bottom traces, average fEPSPs normalized to the peak of the first fEPSP. (B) Paired-pulse ratios (50 ms ISI) for individual slices before (PPR 1) and after (PPR 2) induction of 200 Hz LTP (filled squares, n=14) or for interleaved, non-tetanized, control slices (open squares, n=8). Small symbols, average PPR of 3-5 consecutive sweeps from individual slices. Large symbols, mean of all slices in each group. Asterisk indicates significant difference (P<0.05) between PPR 2 and PPR 1 in tetanized slices (paired t-test). (C) Fractional change in PPR following tetanus (PPR2/PPR1) versus magnitude of LTP (~40 min post-tetanus) for tetanized slices. Dashed red line shows linear fit (P<0.01; R=-0.7, Pearson’s linear regression).

Next we examined whether induction of PP LTP with a theta burst stimulation protocol (TBS) also enhanced presynaptic efficacy, as TBS is thought to represent a more natural pattern of hippocampal activity than 200 Hz tetanization. The TBS protocol produced a significant potentiation of the PP fEPSP (Figure S3A; 42.6 ± 9% potentiation; n=13), which was also associated with a significant increase in the rate of FM 1-43 destaining (Figure S3B-C; ~39% increase; P<0.05) and a reduction in PPF (Figure S3D; P<0.05, paired t-test). These presynaptic changes were smaller than those seen with the 200 Hz induction protocol, consistent with the smaller magnitude of TBS-LTP. Taken together, the above results indicate that the expression of LTP at glutamatergic PP inputs induced by either 200 Hz or TBS stimulation involves, at least in part, an increased efficacy of vesicle release.

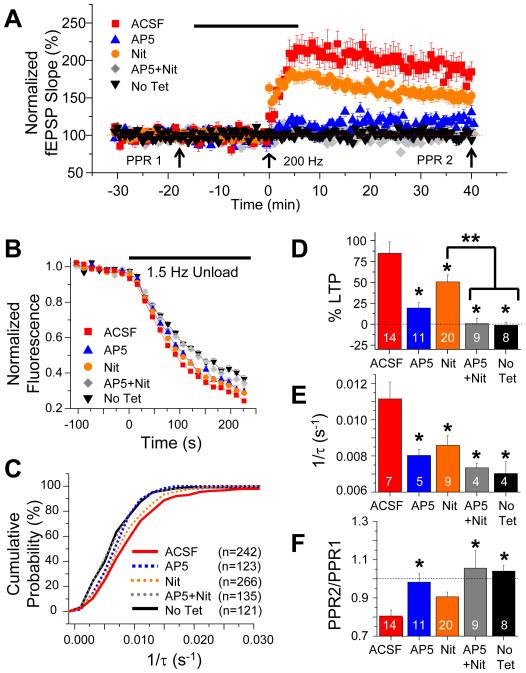

Enhancement in PP presynaptic function and LTP share a dependence on NMDARs and L-type VGCCs

Previous studies have found that LTP at PP synapses requires activation of NMDARs and L-type VGCCs (Golding et al., 2002; Remondes and Schuman, 2003). Therefore, if the enhancement in presynaptic function is related to LTP of the fEPSP, then the presynaptic enhancement should show a similar pharmacological sensitivity. We first confirmed that 200 Hz LTP at the PP synapses was sensitive to blockade of L-type Ca2+ channels and NMDARs (Figure 7A,D). Inhibition of L-type channels with 20 μM nitrendipine (n=20) produced a ~40% decrease in the magnitude of LTP (n=14; P<0.05 compared to the control ACSF group, ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis in all comparisons). Blockade of NMDARs with 50 μM D-AP5 during the 200 Hz tetanic stimulation (n=11) also produced a marked reduction in the magnitude of LTP, resulting in a ~65% block (P<0.05 compared to the control ACSF group). Finally, the combined application of 20 μM nitrendipine and 50 μM D-AP5 completely blocked potentiation (~99% decrease in LTP magnitude; n=9; P<0.05 compared to both ACSF and nitrendipine alone).

Figure 7. Enhancement in the kinetics of FM 1-43 release and decrease in PPF following 200 Hz tetanization share same pharmacological profile as PP LTP.

(A) Mean normalized PP fEPSP in response to 200 Hz tetanus (at 0 min, arrow) in absence or presence of pharmacological inhibitors. Red squares, ACSF alone (no inhibitors). Blue triangles, 50 μM D-AP5, applied during LTP induction protocol (black bar). Orange circles, 20 μM nitrendipine, present throughout experiment. Nitrendipine had no effect on basal synaptic transmission (data not shown). Gray diamonds, joint presence of 20 μM nitrendipine (throughout experiment) and 50 μM D-AP5 (black bar). Black triangles, ACSF alone without tetanus. Symbol key and color code apply to all panels. (B) Mean time course of FM 1-43 destaining ~80-90 min after 200 Hz tetanus in absence or presence of inhibitors as in A. Black triangles, no tetanus. (C) Cumulative probability histograms of FM 1-43 destaining rates (1/τ) showing effects of 200 Hz tetanus with or without pharmacological inhibitors. Legend gives number of boutons in each group. (D) Effect of pharmacological treatments on LTP magnitude measured as fEPSP slope ~40 min post-tetanus, expressed as percent of fEPSP slope during pretetanus baseline. No Tet group (black data bar) shows fEPSP measured at comparable times without tetanization. (E) Mean rates of FM 1-43 destaining (1/τ) measured ~80-90 min following 200 Hz tetanus, with or without indicated inhibitors. Destaining rate was measured at a comparable time in No Tet controls (black data bar). (F) Mean fractional change in PPR after LTP, PPR2 (after tetanus) divided by PPR1 (before tetanus), with or without inhibitors. (D-F) Numbers of slices in each group are shown in data bars. Single asterisks indicate significant difference compared to ACSF control group; double asterisks indicate significant difference between specified groups (P<0.05 in all comparisons; ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc pairwise comparisons).

Next we asked whether the pharmacological sensitivity of the enhancement in FM 1-43 destaining caused by the 200 Hz tetanus was similar to the profile of LTP. Application of either D-AP5 or nitrendipine on its own produced a significant but only partial block in the ability of the tetanus to enhance FM 1-43 release (Figures 7B,C, E). In contrast, the combined application of the two inhibitors completely blocked the increase in FM 1-43 destaining rate. Moreover, the decrease in PPF following 200 Hz stimulation shared the same pharmacological profile (Figure 7F). Overall, these data indicate that the enhancement in presynaptic function and LTP in response to 200 Hz tetanic stimulation share a similar dependence on activation of both L-type Ca2+ channels and NMDARs, and this similarity bears a tight quantitative relationship (Figure S4).

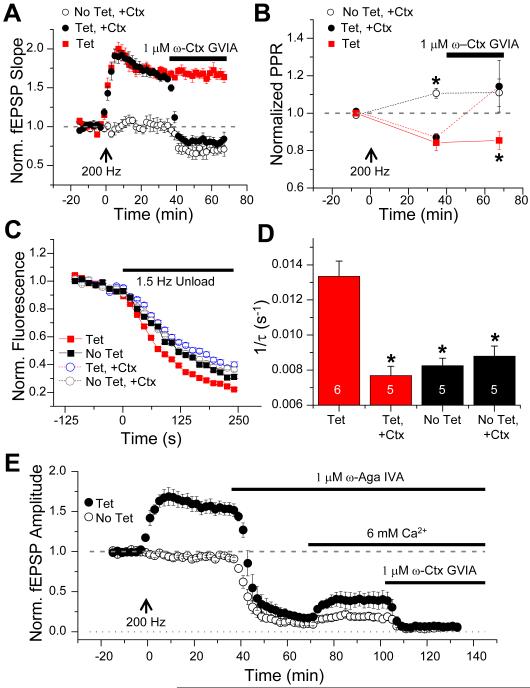

Increased contribution of N-type Ca2+ channels to release accounts for enhanced presynaptic function during PP LTP

Given the low basal contribution of N-type channels to release at PP inputs, we asked whether the enhancement in presynaptic function during LTP might result from an increased contribution of these channels to the release process. To explore this question, we compared the sensitivity of the PP fEPSP to blockade of N-type channels in tetanized versus non-tetanized slices (Figure 8A). Strikingly, application of 1 μM ω-Ctx GVIA produced a nearly two-fold larger inhibition of the PP fEPSP in tetanized slices (52 ± 3% block; n=8) compared to non-tetanized slices (28 ± 7% block; n=6; P<0.001, unpaired t-test). Moreover, in the presence of ω-Ctx GVIA, the fEPSP in tetanized slices was reduced to a level almost identical to that in nontetanized slices (P>0.5; Figure 8A). Thus, application of ω-Ctx GVIA almost fully reversed the expression of LTP that was induced in the absence of toxin. Thus, not only does PP LTP involve an increased contribution of N-type VGCCs to the fEPSP, but this increased contribution appears to account for much of the potentiation.

Figure 8. Increased contribution of N-type Ca2+ channels during expression of LTP accounts for decrease in PPF and enhancement of FM 1-43 release kinetics.

(A) Time course of mean normalized fEPSP and (B) mean normalized PPR for slices receiving 200 Hz tetanus (at 0 min, arrow) without (Tet, red squares, n=6) or with application of 1 μM ω-Ctx GVIA (Tet, +Ctx, black circles, n=8). Toxin was applied ~38 min after tetanus (black bar). In control experiments, 1 μM ω-Ctx GVIA was applied without preceding tetanus (No Tet, +Ctx, open circles, n=6). For each time point in (B), asterisks indicate significant difference between starred group and other groups at that time point (P<0.01 at ~35 min; P<0.05 at ~65 min; ANOVA). (C) Mean FM 1-43 destaining time course ~80-90 min after tetanus in absence (Tet, red squares, n=291 boutons) or presence of 1 μM ω-Ctx GVIA (Tet, +Ctx, blue circles, n=146 boutons). Destaining data without tetanization (No Tet) obtained in absence (No Tet, black squares, n=152 boutons) or presence of 1 μM ω-Ctx GVIA (No Tet, +Ctx, gray circles, n=174 boutons). Slices were loaded with dye in absence of toxin. (D) Mean FM 1-43 destaining rates ~80-90 min post-tetanus. Number of slices in each group are shown in data bars. Asterisks indicate significant difference from tetanized group in absence of toxin (Tet) (P<0.01; ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc pairwise comparisons). (E) Time course of mean normalized fEPSP with or without tetanus followed by successive applications of 1 μM ω-Aga IVA, high Ca2+ (6 mM), and 1 μM ω-Ctx GVIA. Solid circles, 200 Hz tetanus delivered at 0 min (Tet, n=4). Open circles, no tetanus given (No Tet, n=4).

Further evidence for an increased contribution of N-type channels to release comes from a comparison of the effects of ω-Ctx GVIA on PPF before and after induction of 200 Hz LTP (Figure 8B). As described above, ω-Ctx GVIA had no effect on PPF in non-tetanized slices (n=6; P>0.9). However, following induction of LTP, application of the toxin significantly increased PPF (n=8; P<0.05, paired t-test). Importantly, toxin application completely reversed the reduction in PPF seen during LTP (P>0.9 compared to non-tetanized control group, unpaired t-test).

As a further test of whether LTP increased the contribution of N-type channels to release, we compared the effects of ω-Ctx GVIA on the kinetics of FM 1-43 release in tetanized versus non-tetanized slices (Figure 8C). Whereas the toxin had no effect on the rate of FM 1-43 release in non-tetanized slices (P>0.9; Figures 8C,D; also see Figures 3C-E above), ω-Ctx GVIA produced a marked ~40% reduction in the rate of dye release after induction of LTP (Figures 8C,D; P<0.01, ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis). Moreover, in the presence of toxin, the rate of dye release following induction of LTP was reduced to a level identical to that in non-tetanized slices (P>0.9). Thus, ω-Ctx GVIA reversed the effect of LTP to enhance the rate of FM 1-43 dye release, similar to its effect to abolish the potentiation of the fEPSP and antagonize the changes in PPF. The above results on fEPSP amplitude, PPF and FM 1-43 release strongly support the idea that there is an increased contribution of N-type channels to release following induction of LTP that is largely responsible for the enhancement in presynaptic function.

If LTP does indeed enhance the N-type channel component of release, we might expect that, following tetanization, a significant residual fEPSP would be present when P/Q-type channels are blocked with ω-Aga IVA, in contrast to its ability to fully block the fEPSP in nontetanized slices (Figure 3A). However, ω-Aga IVA produced a nearly complete block of the potentiated fEPSP (by 88.5 ± 2%; n=4) following induction of LTP (n=4), similar to the block in nontetanized slices (Figure 8E; n=4; P=0.91 between groups, unpaired t-test). This suggests that even after induction of LTP P/Q-type channels are the predominant source of Ca2+ influx that triggers release.

To reveal a potential N-type-channel-dependent component of release in the presence of ω-Aga IVA, we increased Pr by elevating external Ca2+ from 2 mM to 6 mM (Figure 8E). This resulted in sizable fEPSPs (resolvable above recording noise) in both tetanized and non-tetanized slices and revealed that the N-type-channel-dependent component of the fEPSP was greatly enhanced following induction of LTP. Furthermore, these fEPSPs were completely blocked by ω-Ctx GVIA, indicating that transmitter release in ω-Aga IVA was fully dependent on N-type channels (fEPSP after tetanization reduced to 0.067 ± 0.02 of baseline; nontetanized fEPSP reduced to 0.058 ± 0.010 of baseline; P=0.64, unpaired t-test). This result is consistent with previous findings that R-type Ca2+ channels are not significant contributors to PP synaptic transmission (Golding et al., 2002; Takahashi and Magee, 2009; Tsay et al., 2007).

Final evidence for a role of N-type channels in the expression of LTP comes from our determination of the magnitude of LTP in the presence of ω-Aga IVA and elevated Ca2+. If LTP involves a selective increase in the N-type-channel component of release, there should be a larger fractional enhancement in the fEPSP during LTP when release is fully dependent on N-type channels compared to the size of LTP under normal conditions, when release contains a large, unchanging contribution from P/Q-type channels. Indeed, we found that the magnitude of LTP in 6 mM Ca2+ and ω-Aga IVA (117% potentiation in tetanized compared to nontetanized slices, Figure 8E) was over 2-fold greater than the size of LTP in 2 mM Ca2+ with no toxin present (54% potentiation, Figure 8E). This likely underestimates the true increase in LTP of the isolated N-type channel component as the Ca2+ elevation will enhance Pr on its own, and thus partially occlude any presynaptic contribution to LTP.

Discussion

In this study we find that the PP and SC glutamatergic inputs that converge onto common CA1 pyramidal neurons have distinct presynaptic release properties. The PP terminals have a two-fold lower basal efficacy of release than the SC inputs, and this is largely due to a smaller contribution of N-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels to vesicle release at the PP inputs. Moreover, we find that the low probability of release (Pr) of the PP inputs is enhanced upon induction of NMDAR- and L-type VGCC-dependent LTP. Finally we find that this presynaptic enhancement is due to the recruitment of N-type Ca2+ channels to the release process, which makes an important quantitative contribution to the increase in the fEPSP during LTP.

Basal function of PP versus SC synapses

Our measurements of FM 1-43 destaining kinetics not only allow a qualitative comparison of release efficacy at SC versus PP synapses but can also provide an estimate of the quantitative differences in Pr. Thus, at SC terminals a single stimulus at the start of the 1.5 Hz destaining protocol releases 0.38-0.50% of the fluorescence in a bouton maximally loaded with dye. As a typical SC bouton contains ~100 recycling vesicles (Harata et al., 2001a; Harata et al., 2001b; Ryan et al., 1997), this yields a Pr of ~0.4-0.5, in agreement with previous estimates from FM 1-43 imaging (Zakharenko et al., 2001) and quantal analysis (Bolshakov and Siegelbaum, 1995; Dobrunz and Stevens, 1997; Stevens and Wang, 1994). For PP terminals, a single stimulus initially releases only 0.22-0.29% of dye fluorescence, roughly half that released from the SC puncta. Although the size of the recycling vesicle pool at PP synapses has not been measured, the fluorescence intensity of PP boutons after maximal dye loading is similar to that of SC boutons (P>0.1, unpaired t-test), suggesting comparable numbers of recycling vesicles. This yields an estimate of Pr for the PP synapses of around ~0.2-0.3, roughly half the value at the SC terminals.

Our finding that PP synapses have a lower release efficacy than that of the SC inputs complements the finding that the postsynaptic membrane at PP synapses has a lower number and density of AMPARs compared to the SC postsynaptic membrane (Nicholson et al., 2006). In addition, the distal CA1 dendrites have a greater density of HCN1 channels compared to more proximal CA1 dendrites (Lorincz et al., 2002; Santoro et al., 2000), resulting in a marked decrease in distal dendritic integration and the triggering of dendritic Ca2+ spikes (Nolan et al., 2004; Tsay et al., 2007).

What might be the function of having distal synapses handicapped by both inefficient presynaptic release properties and low postsynaptic responsiveness? Nicholson et al. (2006) proposed that dendritic cable filtering leads to such a large attenuation of PP EPSPs at the CA1 neuron soma that effective information transfer requires the amplification of EPSPs through the firing of distal dendritic Ca2+ spikes. However, because the distal dendrites have a high input impedance, even a relatively weak excitatory input may be sufficient to trigger a local spike. The combination of a low Pr and a low postsynaptic AMPAR density ensures that dendritic spikes can only be elicited by the cooperative firing of multiple PP inputs. Thus, only salient entorhinal cortex activity sufficiently above background is able to propagate to the CA1 soma.

A second potential function of a low Pr is to render the flow of information from the entorhinal cortex to CA1 neurons dependent on input firing frequency. Thus, whereas isolated single presynaptic action potentials are poor triggers of exocytosis at PP synapses due to their low Pr, a burst of presynaptic spikes will elicit release more efficiently due to the marked PPF at these synapses. Typically, layer III entorhinal cortex neurons, which give rise to the CA1 PP inputs, fire single spikes (Frank et al., 2001; Fyhn et al., 2004; Yoshida and Alonso, 2007). However, pharmacological blockade of the M-type voltage-gated K+ current causes these neurons to fire high-frequency bursts (Yoshida and Alonso, 2007). Thus, modulatory transmitters that downregulate M-current in layer III neurons may provide a means of facilitating information flow to CA1 neurons.

Our finding of large PPF at the PP to CA1 synapses in hippocampal slices from 5-7 week old mice is in agreement with recent results for PP to CA1 synapses in slices from 4-6 week old rats (Speed and Dobrunz, 2008), suggesting this property is not species specific. However, this same study reported larger values for PPF at SC synapses than we find in mice, so that PPF values were similar at the rat SC and PP synapses. In contrast, other groups have reported lower PPF values at SC synapses in rats, more similar to our results (Kamiya and Ozawa, 1998; Mahmoud and Grover, 2006; Otmakhova and Lisman, 1999). Further studies will be needed to examine whether these discrepancies at SC inputs reflect genuine differences between species or some more subtle experimental difference.

Differential contribution of N-type Ca2+ channels to basal release at PP and SC synapses

Results from previous studies also suggest that distinct synapses in the hippocampus have different contributions from N-type versus P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. Thus a sizable contribution of N-type Ca2+ channels to release at SC synapses has been previously reported (Qian and Noebels, 2000; Wheeler et al., 1994), similar to our results. In contrast, release from the PP inputs from layer II EC neurons onto dentate gyrus granule cells shows little dependence on N-type channels (Qian and Noebels, 2001), similar to our results for the CA1 neuron inputs from layer III EC neurons. This suggests a generally low level of N-type channel involvement in the basal release efficacy of cortical inputs to the hippocampus.

One question raised by our results is why, under basal conditions, does ω-Ctx GVIA produce a ~25% decrease in the PP fEPSP but have no effect on the kinetics of FM 1-43 destaining or PPF at the same synapses (see Figure 3). This result could occur, in principle, if a small fraction (i.e. 25%) of PP terminals relied solely on N-type channels for release whereas the rest of the terminals relied on P/Q-type channels. In this case, the presence of ω-Ctx GVIA during the destaining stimulation or assay of PPF would completely block release at those terminals dependent on N-type channels (accounting for the 25% decrease in the fEPSP) but should not alter release from the majority of terminals dependent solely on P/Q-type channels, thus explaining the lack of effect of toxin on PPF or FM 1-43 kinetics. However, this hypothesis predicts that ω-Ctx GVIA should increase the fraction of PP terminals that fail to release dye during the destaining stimulation. In contrast, we found no change in this parameter, either at PP or SC terminals (Figure 3F; P=0.68, ANOVA). Thus, we suggest that the quantitative discrepancy may instead reflect either a relative lack of sensitivity of our measures of presynaptic function to small changes in release upon N-type channel blockade or that postsynaptic N-type Ca2+ channels in distal dendrites may be activated to some extent by the local EPSP (Bloodgood and Sabatini, 2007; Tsay et al., 2007) and thus make a small (that is, up to 25%) postsynaptic contribution to the fEPSP.

Enhancement of PP presynaptic function during LTP

Our study is the first to address a potential presynaptic contribution to the expression of LTP at PP to CA1 neuron synapses. Based on our findings that the induction of LTP enhances FM 1-43 release kinetics and reduces PPF at the PP synapses, we conclude that an enhancement in presynaptic release of glutamate is likely to be a major contributor to the enhancement of the EPSP during PP LTP. The presynaptic enhancement we observed at PP synapses upon induction of LTP with 200 Hz and TBS stimulation protocols is similar to the presynaptic enhancement observed at SC synapses with similar patterns of activity (Bayazitov et al., 2007; Zakharenko et al., 2001). Moreover, at both synapses the induction of LTP and the presynaptic enhancement depend on the activation of NMDARs and L-type VGCCs, supporting the existence of a general presynaptic module of LTP (Zakharenko et al., 2003). As this form of LTP requires postsynaptic receptor activation yet involves a presynaptic contribution to expression, it is likely to recruit a retrograde signal. However, it is also important to note that our results do not exclude a postsynaptic component of expression for PP LTP, such as that found at SC synapses (Kerchner and Nicoll, 2008). Indeed our finding that the induction of PP LTP results in a ~70% enhancement in the fEPSP but only a ~55% enhancement in the FM 1-43 destaining rate suggests that at least ~15% of the fEPSP potentiation might be caused by a postsynaptic mechanism.

Given the low initial efficacy of release at PP synapses, an enhancement in release during LTP would greatly increase the reliability of information transfer through this pathway. This might relieve the necessity for the firing of spike bursts by the layer III EC neurons, transforming these inputs from a conditional to a constitutive contributor to signal transmission. In addition, enhanced presynaptic function will increase activation of postsynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors, which participate in the induction of several forms of synaptic plasticity, including heterosynaptic input-timing-dependent-plasticity caused by paired activation of PP and SC inputs (Dudman et al., 2007).

Enhanced contribution of N-type Ca2+ channels to release at PP synapses during LTP

Perhaps the most novel finding of our study is that the increase in release efficacy at PP synapses during LTP depends on the recruitment of N-type Ca2+ channels to the release process. Such a potential mechanism was previously explored for SC LTP induced by 100 Hz tetanic stimulation (Wheeler et al., 1994) and for mossy fiber LTP at synapses from dentate gyrus granule neurons onto CA3 neurons (Castillo et al., 1994). In both instances, N-type channel contributions to synaptic transmission were not enhanced during LTP. However, at both of these synapses the N-type channels make a large contribution to release under basal conditions, unlike at the PP inputs studied here. Thus, an N-type-channel-dependent presynaptic mechanism of LTP may be recruited preferentially at synapses with lower basal contributions of N-type channels. Moreover, because induction of the presynaptic component of SC LTP requires relatively strong tetanization protocols, it will be important to re-examine the role of N-type channels in LTP at SC synapses specifically for those protocols that recruit a presynaptic component of LTP expression (Bayazitov et al., 2007; Choi et al., 2000, 2003; Emptage et al., 2003; Enoki et al., 2009; Ward et al., 2006; Zakharenko et al., 2003; Zakharenko et al., 2001).

If LTP increases the contribution of N-type channels to transmitter release, why do these channels fail to generate an EPSP on their own (in normal extracellular Ca2+) when P/Q type channels are blocked with ω-Aga IVA following induction of LTP (Figure 8E)? One possible explanation depends on the highly cooperative power relation between internal Ca2+ and release (~4th power law at many central synapses) (Borst and Sakmann, 1996; Mintz et al., 1995). Because of this non-linear relation, a small increase in Ca2+ influx through recruitment of N-type channels during LTP would be sufficient to produce a sizable increase in release, even if P/Q-type channels are the predominant source of Ca2+.

To provide an illustrative example, we start by assuming a 4th power relation between intracellular [Ca2+] and release (although we have not directly measured this for the PP synapses). The large effect of P/Q-type channel block and small effect of N-type channel block on the PP fEPSP in nontetanized slices can be accounted for quantitatively if we assume that P/Q-type channels provide ~93% of the Ca2+ coupled to release, with N-type channels providing the residual ~7%. Under these conditions blockade of P/Q-type channels will almost fully block transmission (residual N-type channel-dependent release as a fraction of initial release is given by 0.074 = 0.00002) whereas blockade of N-type channels will produce a ~25% reduction (fractional release given by 0.934 = 0.75), which is what we observed prior to induction of LTP.

To account for the ~70% potentiation of the fEPSP during LTP (in the absence of toxins), we need postulate only a ~14% increase in total Ca2+ influx coupled to release through recruitment of N-type channels (1.144 = 1.7). Thus, even after LTP, P/Q type channels will account for the vast majority of Ca2+ influx coupled to release (equal to 93%/114% of total Ca2+), with N-type channels contributing the minority share (21%/114%). As a result, blockade of P/Q-type channels following induction of LTP will decrease the terminal Ca2+ to 21% of its initial level before LTP, still producing a nearly complete block of the fEPSP (0.214 = 0.002), as we observed with application of ω-Aga IVA in normal extracellular Ca2+ during LTP (Figure 8E). Because of the contribution of P/Q-type channels to release is unchanged during LTP, blockade of N-type channels following tetanization should reduce release to the same level as when N-type channels are blocked prior to LTP (0.75 of the initial release level), similar to what we found (Figure 8A). This predicts a 56% reduction in the size of the fEPSP during LTP upon N-type channel blockade (given by [(1.7 - 0.75)/1.7] x 100%), consistent with the 52 ± 3% reduction we observed upon application of ω-Ctx GVIA after tetanization.

Although blockade of P/Q-type channels nearly eliminated the EPSP even after LTP, we were able to reveal a purely N-type-channel-dependent fEPSP by elevating external Ca2+ to 6 mM to increase Pr (Figure 8E). Importantly, the expression of LTP under these conditions was two-fold greater than the amount of LTP under normal conditions, where release depends on both P/Q-type and N-type channels (Figure 8E). These results strongly support the view that LTP is due in large part to a selective increase in the contribution of N-type channels to release, although P/Q-type channels remain the predominant source of Ca2+.

Potential mechanisms underlying the enhanced contribution of N-type Ca2+ channels to release at PP synapses during LTP

Several mechanisms may account for the increased contribution of N-type channels to release during LTP. First, there may be increased Ca2+ influx through these channels. This could occur through the insertion of additional N-type channels in the presynaptic membrane (Viard et al., 2004) or the reversal of a tonic G-protein-dependent inhibition of N-type channel function (Catterall and Few, 2008; Evans and Zamponi, 2006). Activation of protein kinase C (PKC), which has been implicated in LTP (Wikstrom et al., 2003), is an attractive candidate mechanism as PKC can enhance N-type channel activity directly and antagonize signaling cascades that inhibit N-type channel opening (Evans and Zamponi, 2006; Swartz et al., 1993).

Second, there may be an enhanced coupling between Ca2+ influx through the N-type channels and the release machinery. In many CNS terminals, including the EC layer II neuron projections to the dentate gyrus (Qian and Noebels, 2001), Ca2+ influx through N-type channels is less efficiently coupled to release compared to Ca2+ influx through P/Q-type channels (Mintz et al., 1995; Qian and Noebels, 2000; Wu et al., 1999). Such enhanced coupling could result from an increase in the proximity of N-type channels to vesicle release sites at active zones, for example, through an anchoring mechanism mediated by RIM1 (Kiyonaka et al., 2007), a presynaptic molecule important for long-term plasticity at a variety of CNS inputs (Chevaleyre et al., 2007; Lonart, 2002). Indeed, tightening of the spatial coupling between VGCCs and synaptic vesicles occurs during development at a central synapse and has been found to enhance release (Fedchyshyn and Wang, 2005; Wang et al., 2008).

A third potential mechanism involves increased Ca2+ influx through the broadening of the presynaptic action potential during LTP. Although spike broadening does indeed enhance the opening of N-type channels during an action potential, it should also enhance P/Q-type channel activation (Li et al., 2007). As we found no change in presynaptic efficacy during LTP when N-type channels were blocked and release was solely dependent on the P/Q-type channels (Figure 8), this mechanism appears unlikely. In principle, it may be possible to distinguish between enhanced Ca2+ influx versus enhanced coupling models for LTP by imaging Ca2+ in PP presynaptic terminals during LTP. However, it will be a daunting technical challenge to resolve the small ~14% increase in Ca2+ influx sufficient to account for LTP.

Importantly, whether due to increased N-type channel Ca2+ influx or increased coupling to release, our results indicate that perforant path LTP recruits an enhanced contribution of N-type channel Ca2+ microdomains to vesicle release that leads to a substantial increase in the low initial release probability at the PP synapses. Therefore, by characterizing mechanisms of PP presynaptic function and LTP, we have identified and highlighted the dual role of presynaptic N-type channels as a novel molecular substrate underlying both input-specific presynaptic release properties and long-term synaptic plasticity. Moreover, both of these regulatory mechanisms are poised to differentially regulate information flow through the hippocampal circuit.

Experimental Procedures

Slice preparation and electrophysiological recordings

Horizontal brain slices were prepared from 5-7 week-old C57Bl6 mice using standard procedures as described (Dudman et al., 2007; see Supplemental Procedures for details). ACSF contained (in mM): NaCl (125), NaH2PO4 (1.25), KCl (2.5), NaHCO3 (25), glucose (25), CaCl2 (2), MgCl2 (1), and Na-pyruvate (2), bubbled to pH ~7.4 with 95% O2/5% CO2. Excitatory responses were isolated with blockers of GABAA (2 μM SR95531) and GABAB (1 μM CGP55845A) receptors. The CA3 region was surgically removed to prevent epileptiform activity and activation of the trisynaptic circuit during stimulation of the PP. Slices were perfused (~2-3 ml/min) with standard ACSF and held at 33-35 °C throughout all experiments. fEPSPs were recorded in current-clamp mode with an Axoclamp-2A amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Data was digitized on a Windows PC using an EPC-9 amplifier controlled by PULSE acquisition software (Heka Instruments). Recording pipettes (3-5 MΩ) were filled with ACSF alone or ACSF containing 125 μM FM 1-43 (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA).

Extracellular field stimuli (0.1 ms square current pulses) were applied with concentric bipolar stimulating electrodes positioned >200 μm from sites of recording/imaging and placed in either the inner half of SLM or middle of SR to activate CA1 PP or SC inputs, respectively (Dudman et al., 2007; Nolan et al., 2004). Stimulation intensity was set to give a half-maximal fEPSP slope and inputs were stimulated at 0.033 Hz to monitor synaptic transmission (responses were binned into 2 min intervals in experiments involving ω-Ctx GVIA and ω-Aga IVA).

PPF was measured in the presence of D-AP5 (50 μM) in experiments not involving LTP but in the absence of D-AP5 in LTP experiments. The D-AP5 had no effect on PPF. For experiments involving ω-Aga IVA, the magnitude of the small residual fEPSP was measured as the difference between the response in the absence and presence of CNQX (10 μM; applied at end of experiments) to reduce contamination of the small fEPSP by the stimulus artifact and fiber volley. See Supplemental Procedures for details of drug and toxin application.

PP LTP was induced with either: (1) A 200 Hz protocol consisting of 10 trains of 200 ms periods of stimulation at 200 Hz, delivered once every 5 s; (2) A theta-burst stimulation (TBS) protocol consisted of 4 theta-burst trains of stimuli once every 20 s. Each theta-burst train consisted of 5 bursts every 200 ms, with each burst containing 10 stimuli at 100 Hz.

FM 1-43 Loading and Unloading

FM 1-43 was loaded into presynaptic terminals using a protocol similar to that described previously (Zakharenko et al., 2003; Zakharenko et al., 2001). However, here we applied dye using a 5 min, 200 nA positive iontophoretic current pulse from a patch pipette filled with 125 μM FM 1-43, instead of using pressure ejection of dye from a patch pipette as done previously, as the current pulse produced less movement in the slice. The pipette was placed ~100 μm below the surface of the slice in either the inner half of SLM or middle of SR and dye delivery was monitored using 2-photon imaging. Blockers of ionotropic glutamatergic transmission (50 μM D-AP5, with or without 10 μM CNQX as noted below) were added to the external solution to prevent excitotoxic damage and induction of plasticity caused by synaptic stimulation during the loading and unloading procedures. Presynaptic terminals were imaged in a region 15-30 μm away from the tip of the recording/dye delivery electrode to ensure that imaged terminals were likely to contribute to recorded fEPSPs. After 2 min of dye iontophoresis, input pathways were stimulated at 10 Hz for 2 min to trigger exocytosis of synaptic vesicles and load dye into recycling vesicles. The dye iontophoresis period lasted an additional minute past the end of axonal stimulation to ensure the completion of endocytosis and, thus, of dye uptake. This protocol loaded dye into terminals maximally.

Once terminals were loaded with dye, 200 μM ADVASEP-7 (Cydex, Lenexa, KS) was added to the external solution and slices were further perfused for 20-30 min to remove any dye bound to extracellular tissue (Kay et al., 1999). We also included ADVASEP-7 during the unloading period to prevent the reuptake of dye into terminals following exocytosis. To determine FM 1-43 destaining rates during the unloading procedure, we stimulated the input pathways at 1.5 Hz for 4 min. At the end of this stimulation, we immediately applied a second round of stimulation at 10 Hz for 2 min to maximally unload dye and to calculate residual fluorescence for subsequent background subtraction and normalization. Only those terminals showing a significant (>15%) loss of fluorescence upon electrical stimulation were considered for analysis.

Previously, we found that loading and unloading of SC terminals with dye was not altered by CNQX (Zakharenko et al., 2001). In preliminary experiments, we found that CNQX similarly did not affect dye loading and unloading at PP terminals, indicating that the dye release was not complicated by activation of postsynaptic neurons. Therefore, in experiments involving FM 1-43 assays before and after induction of LTP, we did not include CNQX since D-AP5 alone was sufficient to prevent dendritic damage and induction of plasticity caused by synaptic stimulation during the load/unload periods.

Two-Photon Imaging and Analysis

Two-photon microscopy was performed using a custom-modified BioRad (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) 1024-MP or Radiance 2100-MP (for Figure S2 only) microscope as described (Tsay et al., 2007; Zakharenko et al., 2001). Images in a z-stack were maximally projected, aligned in time series, and fluorescence time course of puncta in imaging fields analyzed with custom-written software in Interactive Data Language (IDL, Research Systems, Inc., Boulder, CO), as described previously. See also Supplemental Procedures for further details.

All error bars represent standard error. Statistical tests were performed using Origin software (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA). The normal distribution of all data groups in which t-test and ANOVA comparisons were made was first confirmed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used for groups of data that were not normally distributed (P<0.05, Shapiro-Wilk test).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Leonard Zablow for indispensable help with custom-written IDL software, David Tsay and Jayeeta Basu for help with experiments in Figure S2, and Bernardo Sabatini for suggesting the experiments in Fig. 8E. We thank Jayeeta Basu, Vivien Chevaleyre, Cindy Lang, Rebecca Piskorowski, and Bina Santoro for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (S.A.S.) and an NIH MSTP training grant (M.S.A.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbott LF, Regehr WG. Synaptic computation. Nature. 2004;431:796–803. doi: 10.1038/nature03010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang CW, Carlson GC, Coulter DA. Hippocampal CA1 circuitry dynamically gates direct cortical inputs preferentially at theta frequencies. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9567–9580. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2992-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayazitov IT, Richardson RJ, Fricke RG, Zakharenko SS. Slow presynaptic and fast postsynaptic components of compound long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11510–11521. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3077-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz WJ, Bewick GS. Optical analysis of synaptic vesicle recycling at the frog neuromuscular junction. Science. 1992;255:200–203. doi: 10.1126/science.1553547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloodgood BL, Sabatini BL. Ca(2+) signaling in dendritic spines. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolshakov VY, Siegelbaum SA. Regulation of hippocampal transmitter release during development and long-term potentiation. Science. 1995;269:1730–1734. doi: 10.1126/science.7569903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JG, Sakmann B. Calcium influx and transmitter release in a fast CNS synapse. Nature. 1996;383:431–434. doi: 10.1038/383431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun VH, Leutgeb S, Wu HQ, Schwarcz R, Witter MP, Moser EI, Moser MB. Impaired spatial representation in CA1 after lesion of direct input from entorhinal cortex. Neuron. 2008;57:290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun VH, Otnass MK, Molden S, Steffenach HA, Witter MP, Moser MB, Moser EI. Place cells and place recognition maintained by direct entorhinal-hippocampal circuitry. Science. 2002;296:2243–2246. doi: 10.1126/science.1071089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo PE, Weisskopf MG, Nicoll RA. The role of Ca2+ channels in hippocampal mossy fiber synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation. Neuron. 1994;12:261–269. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Few AP. Calcium channel regulation and presynaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008;59:882–901. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevaleyre V, Heifets BD, Kaeser PS, Sudhof TC, Castillo PE. Endocannabinoid-mediated long-term plasticity requires cAMP/PKA signaling and RIM1alpha. Neuron. 2007;54:801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Klingauf J, Tsien RW. Postfusional regulation of cleft glutamate concentration during LTP at ‘silent synapses’. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:330–336. doi: 10.1038/73895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Klingauf J, Tsien RW. Fusion pore modulation as a presynaptic mechanism contributing to expression of long-term potentiation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003;358:695–705. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha RA, Ribeiro JA. Purinergic modulation of [(3)H]GABA release from rat hippocampal nerve terminals. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:1156–1167. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrunz LE, Stevens CF. Heterogeneity of release probability, facilitation, and depletion at central synapses. Neuron. 1997;18:995–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudman JT, Tsay D, Siegelbaum SA. A role for synaptic inputs at distal dendrites: instructive signals for hippocampal long-term plasticity. Neuron. 2007;56:866–879. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H. A cortical-hippocampal system for declarative memory. Nature reviews. 2000;1:41–50. doi: 10.1038/35036213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emptage NJ, Reid CA, Fine A, Bliss TV. Optical quantal analysis reveals a presynaptic component of LTP at hippocampal Schaffer-associational synapses. Neuron. 2003;38:797–804. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoki R, Hu YL, Hamilton D, Fine A. Expression of long-term plasticity at individual synapses in hippocampus is graded, bidirectional, and mainly presynaptic: optical quantal analysis. Neuron. 2009;62:242–253. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RM, Zamponi GW. Presynaptic Ca2+ channels--integration centers for neuronal signaling pathways. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:617–624. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedchyshyn MJ, Wang LY. Developmental transformation of the release modality at the calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4131–4140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0350-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank LM, Brown EN, Wilson MA. A comparison of the firing properties of putative excitatory and inhibitory neurons from CA1 and the entorhinal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:2029–2040. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.4.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyhn M, Molden S, Witter MP, Moser EI, Moser MB. Spatial representation in the entorhinal cortex. Science. 2004;305:1258–1264. doi: 10.1126/science.1099901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding NL, Staff NP, Spruston N. Dendritic spikes as a mechanism for cooperative long-term potentiation. Nature. 2002;418:326–331. doi: 10.1038/nature00854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harata N, Pyle JL, Aravanis AM, Mozhayeva M, Kavalali ET, Tsien RW. Limited numbers of recycling vesicles in small CNS nerve terminals: implications for neural signaling and vesicular cycling. Trends Neurosci. 2001a;24:637–643. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)02030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harata N, Ryan TA, Smith SJ, Buchanan J, Tsien RW. Visualizing recycling synaptic vesicles in hippocampal neurons by FM 1-43 photoconversion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001b;98:12748–12753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171442798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscock JJ, Murphy S, Willoughby JO. Confocal microscopic estimation of GABAergic nerve terminals in the central nervous system. J Neurosci Methods. 2000;95:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(99)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarsky T, Roxin A, Kath WL, Spruston N. Conditional dendritic spike propagation following distal synaptic activation of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1667–1676. doi: 10.1038/nn1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya H, Ozawa S. Kainate receptor-mediated inhibition of presynaptic Ca2+ influx and EPSP in area CA1 of the rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 1998;509(Pt 3):833–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.833bm.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay AR, Alfonso A, Alford S, Cline HT, Holgado AM, Sakmann B, Snitsarev VA, Stricker TP, Takahashi M, Wu LG. Imaging synaptic activity in intact brain and slices with FM1-43 in C. elegans, lamprey, and rat. Neuron. 1999;24:809–817. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerchner GA, Nicoll RA. Silent synapses and the emergence of a postsynaptic mechanism for LTP. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:813–825. doi: 10.1038/nrn2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyonaka S, Wakamori M, Miki T, Uriu Y, Nonaka M, Bito H, Beedle AM, Mori E, Hara Y, De Waard M, et al. RIM1 confers sustained activity and neurotransmitter vesicle anchoring to presynaptic Ca2+ channels. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:691–701. doi: 10.1038/nn1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Bischofberger J, Jonas P. Differential gating and recruitment of P/Q-, N-, and R-type Ca2+ channels in hippocampal mossy fiber boutons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13420–13429. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1709-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Tsien RW. Properties of synaptic transmission at single hippocampal synaptic boutons. Nature. 1995;375:404–408. doi: 10.1038/375404a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonart G. RIM1: an edge for presynaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:329–332. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorincz A, Notomi T, Tamas G, Shigemoto R, Nusser Z. Polarized and compartment-dependent distribution of HCN1 in pyramidal cell dendrites. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1185–1193. doi: 10.1038/nn962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maass W, Zador AM. Dynamic stochastic synapses as computational units. Neural Comput. 1999;11:903–917. doi: 10.1162/089976699300016494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud GS, Grover LM. Growth hormone enhances excitatory synaptic transmission in area CA1 of rat hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:2962–2974. doi: 10.1152/jn.00947.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megias M, Emri Z, Freund TF, Gulyas AI. Total number and distribution of inhibitory and excitatory synapses on hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. Neuroscience. 2001;102:527–540. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz IM, Sabatini BL, Regehr WG. Calcium control of transmitter release at a cerebellar synapse. Neuron. 1995;15:675–688. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashiba T, Young JZ, McHugh TJ, Buhl DL, Tonegawa S. Transgenic inhibition of synaptic transmission reveals role of CA3 output in hippocampal learning. Science. 2008;319:1260–1264. doi: 10.1126/science.1151120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson DA, Trana R, Katz Y, Kath WL, Spruston N, Geinisman Y. Distance-dependent differences in synapse number and AMPA receptor expression in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Neuron. 2006;50:431–442. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan MF, Malleret G, Dudman JT, Buhl DL, Santoro B, Gibbs E, Vronskaya S, Buzsaki G, Siegelbaum SA, Kandel ER, Morozov A. A behavioral role for dendritic integration: HCN1 channels constrain spatial memory and plasticity at inputs to distal dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons. Cell. 2004;119:719–732. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otmakhova NA, Lisman JE. Dopamine selectively inhibits the direct cortical pathway to the CA1 hippocampal region. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1437–1445. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-04-01437.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastalkova E, Serrano P, Pinkhasova D, Wallace E, Fenton AA, Sacktor TC. Storage of spatial information by the maintenance mechanism of LTP. Science. 2006;313:1141–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.1128657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J, Noebels JL. Presynaptic Ca(2+) influx at a mouse central synapse with Ca(2+) channel subunit mutations. J Neurosci. 2000;20:163–170. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00163.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J, Noebels JL. Presynaptic Ca2+ channels and neurotransmitter release at the terminal of a mouse cortical neuron. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3721–3728. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-11-03721.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remondes M, Schuman EM. Direct cortical input modulates plasticity and spiking in CA1 pyramidal neurons. Nature. 2002;416:736–740. doi: 10.1038/416736a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remondes M, Schuman EM. Molecular mechanisms contributing to long-lasting synaptic plasticity at the temporoammonic-CA1 synapse. Learn Mem. 2003;10:247–252. doi: 10.1101/lm.59103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remondes M, Schuman EM. Role for a cortical input to hippocampal area CA1 in the consolidation of a long-term memory. Nature. 2004;431:699–703. doi: 10.1038/nature02965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan TA, Reuter H, Smith SJ. Optical detection of a quantal presynaptic membrane turnover. Nature. 1997;388:478–482. doi: 10.1038/41335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro B, Chen S, Luthi A, Pavlidis P, Shumyatsky GP, Tibbs GR, Siegelbaum SA. Molecular and functional heterogeneity of hyperpolarization-activated pacemaker channels in the mouse CNS. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5264–5275. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-05264.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speed HE, Dobrunz LE. Developmental changes in short-term facilitation are opposite at temporoammonic synapses compared to Schaffer collateral synapses onto CA1 pyramidal cells. Hippocampus. 2008 doi: 10.1002/hipo.20496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens CF, Wang Y. Changes in reliability of synaptic function as a mechanism for plasticity. Nature. 1994;371:704–707. doi: 10.1038/371704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz KJ, Merritt A, Bean BP, Lovinger DM. Protein kinase C modulates glutamate receptor inhibition of Ca2+ channels and synaptic transmission. Nature. 1993;361:165–168. doi: 10.1038/361165a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Magee JC. Pathway interactions and synaptic plasticity in the dendritic tuft regions of CA1 pyramidal neurons. Neuron. 2009;62:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsay D, Dudman JT, Siegelbaum SA. HCN1 channels constrain synaptically evoked Ca2+ spikes in distal dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons. Neuron. 2007;56:1076–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viard P, Butcher AJ, Halet G, Davies A, Nurnberg B, Heblich F, Dolphin AC. PI3K promotes voltage-dependent calcium channel trafficking to the plasma membrane. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:939–946. doi: 10.1038/nn1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LY, Neher E, Taschenberger H. Synaptic vesicles in mature calyx of Held synapses sense higher nanodomain calcium concentrations during action potential-evoked glutamate release. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14450–14458. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4245-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward B, McGuinness L, Akerman CJ, Fine A, Bliss TV, Emptage NJ. State-dependent mechanisms of LTP expression revealed by optical quantal analysis. Neuron. 2006;52:649–661. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DB, Randall A, Tsien RW. Roles of N-type and Q-type Ca2+ channels in supporting hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science. 1994;264:107–111. doi: 10.1126/science.7832825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikstrom MA, Matthews P, Roberts D, Collingridge GL, Bortolotto ZA. Parallel kinase cascades are involved in the induction of LTP at hippocampal CA1 synapses. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:828–836. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LG, Westenbroek RE, Borst JG, Catterall WA, Sakmann B. Calcium channel types with distinct presynaptic localization couple differentially to transmitter release in single calyx-type synapses. J Neurosci. 1999;19:726–736. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00726.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon KW, Rothman SM. Adenosine inhibits excitatory but not inhibitory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1375–1380. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-05-01375.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Alonso A. Cell-type specific modulation of intrinsic firing properties and subthreshold membrane oscillations by the M(Kv7)-current in neurons of the entorhinal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:2779–2794. doi: 10.1152/jn.00033.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharenko SS, Patterson SL, Dragatsis I, Zeitlin SO, Siegelbaum SA, Kandel ER, Morozov A. Presynaptic BDNF required for a presynaptic but not postsynaptic component of LTP at hippocampal CA1-CA3 synapses. Neuron. 2003;39:975–990. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]