Abstract

Spin relaxation taking place during radiofrequency (RF) irradiation can be assessed by measuring the longitudinal and transverse rotating frame relaxation rate constants (R1ρ and R2ρ). These relaxation parameters can be altered by utilizing different settings of the RF irradiation, thus providing a useful tool to generate contrast in MRI. In this work we investigate the dependencies of R1ρ and R2ρ due to dipolar interactions and anisochronous exchange (i.e., exchange between spins with different chemical shift δω≠0) on the properties of conventional spin-lock and adiabatic pulses, with particular emphasis on the latter ones which were not fully described previously. The results of simulations based on relaxation theory provide a foundation for formulating practical considerations for in vivo applications of rotating frame relaxation methods. Rotating frame relaxation measurements obtained from phantoms and from the human brain at 4T are presented to confirm the theoretical predictions.

Keywords: rotating frame relaxations, spin-lock, adiabatic pulses, dipolar interactions, anisochronous exchange, MR contrast

A. Introduction

Rotating frame relaxation rate constants, R1ρ and R2ρ, characterize relaxation during radiofrequency (RF) irradiation when the magnetization vector is aligned with or perpendicular to the direction of the effective magnetic field (), respectively. R1ρ and R2ρ reflect the features of the spin dynamic processes, and depend on the properties of the RF irradiation [1-4]. The latter feature creates the possibility to “manipulate” the measured R1ρ and R2ρ by choosing different settings of the RF irradiation, thus leading to the generation of MR contrast [5,6]. Whereas the spin-lattice relaxation rate constant R1 is sensitive to dynamic processes close to the Larmor frequency (ω0/(2π)), which is in the order of MHz for standard in vivo applications, in the majority of cases the rotating frame relaxations are additionally sensitive to fluctuations close to the effective frequency (ωeff/(2π), where ωeff = γBeff and γ is the gyromagnetic ratio), which is in the order of kHz. The enhanced sensitivity of R1ρ and R2ρ to molecular dynamics in the kHz range makes rotating frame relaxations a practical tool for gaining information about water spin dynamics and interactions with endogenous macromolecules [7]. Application of these methods holds great potential for addressing several biological questions, especially at high magnetic fields.

A typical method to measure R1ρ and R2ρ is the conventional spin-lock (SL) experiment, where a continuous-wave (CW) pulse is applied on- or off-resonance (for review see [4]). In the presence of the CW pulse, relaxations due to different relaxation channels, such as dipolar interaction and exchange, are well investigated [3,8]. Advances in RF pulse design and experimental capabilities have led to the routine use of pulse sequences based on adiabatic RF pulses for in vivo applications [9]. Rotating frame relaxation experiments can also be performed with adiabatic pulses [10]. Although the theoretical investigation of rotating frame relaxations during adiabatic RF pulses has been recently extended [10,11], much work remains to be done to characterize the influence of the experimental parameters on the measured relaxations.

The aim of the present work is to describe the effects of different RF irradiation parameters on either CW (spin-lock) or adiabatic R1ρ and R2ρ, due to dipolar interactions in the weak field limit (i.e., fast motional regime) and in the presence of anisochronous exchange (i.e., exchange between spins with different chemical shifts, δω ≠ 0) in the fast exchange regime (FXR). Specifically, the simulations presented here exploit the dependencies of R1ρ and R2ρ on i) the amplitude and direction of the effective field during the CW SL pulse, and ii) the pulse length, bandwidth, and RF peak amplitude during adiabatic rotation. Finally the effect on relaxations introduced by different pulse modulation functions of adiabatic pulses is discussed, and a practical perspective of rotating frame relaxation methods for in vivo applications is provided. Experimental results obtained from phantoms and from the human brain at 4T are presented to confirm some relevant theoretical predictions.

B. Theoretical overview

B.1. Properties of the effective magnetic field during SL versus adiabatic rotation

During the CW SL pulse, is tilted from the quantization axis z' (i.e., the longitudinal axis of the first rotating frame) by the angle α (Figure 1a), defined as:

| [1] |

where ω1 is the amplitude of the SL pulse in rad/s and Δω = (ω0 - ωRF) is the frequency offset in rad/s. The amplitude of the effective frequency ωeff (= γBeff, where γ is the gyromagnetic ratio) is given by:

| [2] |

During an adiabatic pulse, both amplitude and frequency are typically modulated (Figure 2a). In the present study, we use adiabatic pulses of the hyperbolic secant (HSn) family [9,12,13]. The amplitude of HSn pulses is given by:

| [3] |

where is the maximum value of ω1(t) in rad/s, β is a truncation factor (sech(β) = 0.01), Tp is the pulse duration, t∈[0, Tp], and n = 1 and 4 for HS1 and HS4 pulses, respectively. With respect to the carrier frequency ωc, i.e., the center frequency in the bandwidth (BW) of interest, the frequency modulation for HS1 pulse is given by:

| [4] |

and for the HS4 pulse is given by:

| [5] |

where A is the amplitude of the frequency sweep in rad/s, with the bandwidth of the pulse being BW = 2A. One fundamental property of the adiabatic pulse is the so time-bandwidth product given by:

| [6] |

From Eq. [6], it is evident that at a given Tp settings, the amplitude of the frequency sweep (A) is determined by the R-value. Note that if A is given in Hz, then R = 2ATp, and consequently:

| [7] |

During the application of adiabatic pulses, both magnitude and orientation of the effective field vary continuously (Figure 2c,d); therefore, ωeff(t) and α(t) are functions of time:

| [8] |

| [9] |

The time-dependent precession angle around the effective field direction is given by:

| [10] |

The adiabatic condition is well satisfied when the change in orientation of the effective field is significantly slower than the rotation of around the effective field: ωeff>>|dα/dt|. An adiabatic pulse which performs a π rotation of (Figure 2b) is called adiabatic full passage (AFP).

Figure 1.

Effective magnetic field during conventional spin-lock pulse (a) and during adiabatic rotation (b). The effective magnetic field () is the vector sum of the RF generated magnetic field B1x' and a longitudinal field component [B0 - ωRF/γ] z'. In the first rotating frame is kept in the x'z' plane, since the frame rotates around z' (≡z) with frequency ωRF. In the second rotating frame, z" is aligned with the direction of , and therefore this frame is tilted compared to z' by the angle α. The magnitude and the direction of are kept stationary in the first rotating frame during the conventional spin-lock pulse, whereas they are time-dependent during the adiabatic rotation, since is a function of the amplitude and frequency modulation functions.

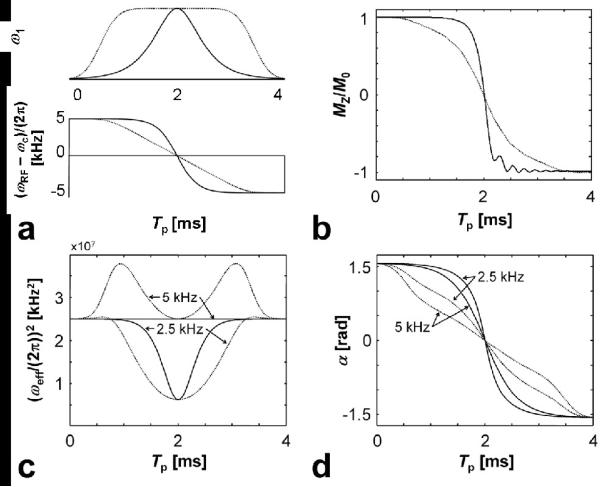

Figure 2.

Properties of adiabatic full passage (AFP) pulses, namely the hyperbolic secant HS1 (solid lines) and HS4 (dotted lines) pulses. a) amplitude and frequency modulation functions., with Tp = 4 ms, R-value = 40, corresponding to B = 10 kHz, ; b) trajectories showing the inversion of the magnetization for the isochromat centered at the carrier frequency of the pulse. Note that during the AFP, the magnetization of each isochromat within the BW becomes inverted by the end of the pulse; c-d) evolution of α(t) and (ωeff/(2π))2 during the pulses. Since α(t) and ωeff/(2π))2 depend not only on the modulation functions but also on the pulse parameters, the cases corresponding to and 5 kHz are presented. Note that when , i.e. when , then ωeff/(2π))2 during the HS1 pulse becomes time-independent. This is because the known trigonometric identity ω2eff = A·[sech2(β(2t/Tp-1)) + tan2(β(2t/Tp-1))] = A.

B.2. Relaxations during conventional spin-lock versus adiabatic rotation

The relaxation mechanisms occurring during the application of CW pulses depend on the initial orientation of relative to . Specifically, when is collinear with , the relaxation is governed solely by R1ρ process; if the angle between and is 90°, the relaxation is governed by R2ρ. For any other orientation, the relaxation is governed by the combination of R1ρ and R2ρ. Typically, the CW SL R1ρ experiment is performed by tilting to the x'y' plane, followed by application of the CW pulse with a 90° phase difference relative to the phase of the excitation pulse phase [14]; for the R2ρ measurements the phase difference needs to be 0° or 180°, as was originally proposed by Solomon [15].

When applying adiabatic pulses, the relaxation mechanisms occurring during the RF irradiation depend on the initial orientation of [10]. In fact, when is originally aligned along the z' axis and the adiabatic pulse is applied, remains oriented along the time-dependent direction of the effective field. In this case the decay of is characterized by the time-dependent rate contrast R1ρ(t). If is instead initially in the x'y' plane and the adiabatic pulse is applied, precesses in the plane perpendicular to , and the relaxation is characterized by R2ρ(t).

In the following, we will overview the formalism utilized to describe relaxation due to dipolar interactions in the case of two identical spins and anisochronous exchange. The formalism was initially formulated to describe relaxation during CW SL experiments, where ωeff and α are constant during the RF irradiation [1,2,16,17]. Recently, the theoretical expressions of R1ρ(t) and R2ρ(t) have been generalized to the case of time-dependent ωeff(t) and α(t) [6,18,19]. It has been shown that the relaxations during adiabatic rotation in the weak field approximation could be represented as an average of instantaneous time-dependent contributions due to the different relaxation channels:

| [11] |

where R1,2ρ,dd and R1,2ρ,ex are the rotating frame relaxations due to dipolar interactions and anisochronous exchange, respectively.

B.2.a. Relaxations due to dipolar interactions: two identical (like) spins

For a system of two equivalent nuclei of spin I = ½ and gyromagnetic ratio γ = 2π · 42.576 · 106 rad/(sT) in a single site, R1ρ,dd(t) and R2ρ,dd(t) due to dipolar fluctuations can be given by a simple, isolated two-spin description [6,11,16,18]:

| [12] |

| [13] |

where b= - μ 0ℏγ2/(4πr3), μ0 = 4π · 10-7 H/m is the vacuum permeability, ℏ = 1.055 · 10-34 Js is Planck's constant, r is the internuclear distance in m, τc is the rotational correlation time in s characterizing the tumbling of the magnetic dipole. Eqs. [12-13] are written in a general form where ωeff and α are time-dependent, and they can be used to calculate the time-courses of R1ρ,dd or R2ρ,dd values during the adiabatic pulse (Eq. [11]). Eqs. [12-13] apply also for a CW SL experiment, with the only difference being that ωeff and α are time-invariant [16]. For comparison purposes, the equations for the free precession relaxation rate constants are provided [20]:

| [14] |

| [15] |

B.2.b. Relaxations due to anisochronous exchange

We consider a two-site chemical exchange process between sites m and . The difference in chemical shifts between sites m and q is defined by δω in rad/s. Here k1 and k-1 represent the forward and backward exchange rate constants obeying the McConnell relationship [21]:

| [16] |

and for anisochronous exchange in the fast regime

| [17] |

Exchange-induced R1ρ,ex and R2ρ,ex under CW SL irradiation were derived in [1,2]:

| [18] |

| [19] |

The corresponding time-dependent relaxation functions during adiabatic rotation were detailed in [19]. Theory shows R1ρ,ex and R2ρ,ex to be dependent on the choice of the amplitude- and frequencymodulation functions of adiabatic pulses via their α(t) and ωeff(t) dependencies. The exchange-induced R1ρ,ex(t) during adiabatic rotation follows from the relaxation functions derived in [10]:

| [20] |

In the FXR, Eq. [20] simplifies to

| [21] |

The exchange-induced R2ρ,ex in the FXR during the adiabatic pulses is given by [18]:

| [22] |

Note that the time-dependence of R2ρ,ex (t) originates from the time-dependence of α(t) and not from ωeff(t). As in the presence of dipolar interactions, Eqs. [21-22] can be used to calculate the time-courses of the instantaneous contributions to be used in Eq. [11] to calculate the average relaxation rates during adiabatic pulses.

Finally, it is well known that anisochronous exchange does not contribute to the free precession longitudinal relaxation R1, but it generates a free precession transverse relaxation rate which is given by [3]

| [23] |

.

C. Material and methods

Simulations

The RF pulses with different amplitude and frequency modulation functions were generated using an even time scale with 500 points per millisecond according to Eqs. [3-5]. Then, ωeff(t) and α(t) were computed according to Eqs. [8] and [9], respectively. Relaxation rates in the presence of dipolar interactions and anisochronous exchange were calculated separately for each time point, i.e. for certain α(t) and ωeff(t), according to Eqs. [12,13], and [18,19,21,22] respectively. The time average over the pulse time duration was then estimated by numerical integration, according to Eq. [11]. All simulations were carried out using Matlab 7.3 platform (Mathworks Inc., Natick, CA).

Phantom experiments

Phantom experiments were performed on 4-T/90-cm Oxford magnet interfaced to Varian INOVA console. A linear coil consisting of a single loop with a 2-cm diameter was used. A water/ethanol sample was prepared at the molar ratio ~1.1:0.9 to investigate the dependencies of adiabatic R1ρ and R2ρ on RF parameters in the case of anisochronous exchange. Relaxation measurements were performed on the single line resulting from the fast exchange between protons from water and the hydroxyl group of ethanol. Adiabatic R1ρ and R2ρ measurements were performed by placing a train of HSn pulses prior to or after the coherent excitation by adiabatic half passage (AHP) pulse, respectively. Localization was achieved by adiabatic selective refocusing (LASER) [9] for 5 × 5 × 5 mm3 voxel selection. The pulse trains consisted of a variable number of HS1 or HS4 pulses (4, 8, 16, 32 and 64 pulses), with phases prescribed according to MLEV-4,-8,-12,-16,-32 [22] and Tp = 6 ms. For exploiting the ω1max dependence, ω1max/(2π) values from 1.75 kHz to 4.4 kHz were used. For exploiting the BW dependency, R-values of 15, 20, 30 and 40 were used, corresponding to BW = 2.5, 3.3, 5.0 and 6.6 kHz for Tp = 6ms, respectively. The relaxation rate constants were calculated from the signal intensities using a linear regression algorithm with a mono-exponential decay function.

In vivo experiments

Two healthy subjects were investigated on the same 4-T/90-cm magnet used for phantoms experiments. A shielded quadrature transmit/receive half-volume RF coil consisting of two geometrically decoupled single-turn coils with diameter of 12 cm was used for spectroscopic measurements similar to the ones performed on phantoms, while a TEM volume coil [23] was used for imaging experiments. For the MRS experiments, the localization (VOI = 20 × 20 × 20 mm3) was performed as described for phantom experiments, with TE = 39 ms, TR = variable from 4.5 to 13 s (to comply with the FDA limits on the specific absorption rate, SAR). Other parameters were: number of pulses in the AFP pulse train was 4, 8, 16 and 32; Tp = 6ms. To investigate the BW dependency, we used R-values of 10 and 20 which correspond to BW = ~ 1.6 and 3.3 kHz, respectively, with ω1max/(2π) = 1.25 kHz; to investigate the ω1max dependency, we used ω1max/(2π) values of 0.9 and 1.7 kHz, with R-value = 10; finally, to investigate the dependency on the modulation functions, we used HS1 or HS4 pulses with R-value = 20 and ω1max/(2π) = 1.25 kHz.

The purpose of the imaging experiments was to compare the contrast (defined as the relative change in measured relaxation rate constants) generated by varying RF parameters of CW SL and adiabatic irradiation in the R1ρ configuration. Images were acquired by fast spin echo readout, TR = 5 s, TE = 0.60 s, matrix 128 × 128, FOV = 20 cm × 20 cm, and slice-thickness = 3mm. In the adiabatic R1ρ configuration, a train of 4, 8, 12, or 16 HS1 or HS4 pulses was placed prior to the spectroscopic or imaging readout. The RF parameters of the adiabatic pulses were: Tp = 6 ms, HS1 modulation functions with R-value = 20 and ω1max/(2π) = 1.25 kHz, or HS4 modulation function with R-value = 20, and ω1max/(2π) = 0.885 kHz. RF parameters of the two adiabatic pulses were chosen to achieve comparable RF power depositions. For the CW SL experiment, composite pulses were generated by placing a CW pulse with varying Tp between two 8-ms adiabatic half passage (AHP) pulses as described in [24]. The duration of the spin-locking time was the same as that used for the adiabatic R1ρ measurements (namely 24, 48, 72 and 96 ms), while ω1max/(2π) = 0.625 kHz, which resulted in RF power deposition similar to the adiabatic R1ρ experiment. The carrier frequency of these composite pulses was chosen on resonance, or 0.625 kHz off-resonance from the water resonance, thus locking at α =0° or 45°, respectively. The acquisition time of each relaxation map was ~ 5 min.

SAR monitoring for human studies

The RF power delivered to the coil was limited to a safe operating range using the hardware monitoring module of the Varian console. In addition, the RF power output over the full range of settings used in these experiments was measured with an oscilloscope connected to the coil port. From these measured values, the average RF power delivered to the coil was computed by integration of all RF pulses in the sequence, and SAR was estimated assuming a tissue load of 3 kg in the coil. When using the longest pulse train, the estimated SAR was always below the FDA limit of 3 W/kg averaged over the head for 10 min (http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/ode/mri340.pdf).

D. Simulation Results

D. 1 R1ρ and R2ρ during continuous-wave spin-lock

Dependency of rotating frame relaxation rate constants on angle α

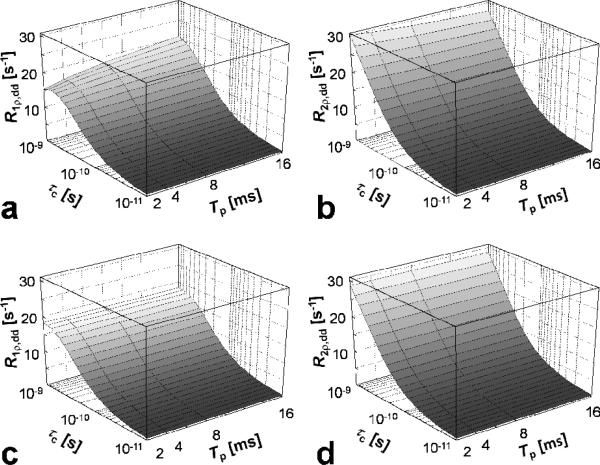

The dependencies of R1ρ,dd and R2ρ,dd during CW SL pulse on the rotational correlation time (τc) and a in the presence of dipolar interactions are shown in Figure 3a,b. It can be seen that, for dipolar interactions in the extreme narrowing case (ω0τc<<1, ω1<<ω0), the R1ρ reaches its maximum value for α = 90°. In this condition (α = 90°), for dipolar interaction between identical spins, R1ρ,dd ≡ R2ρ,dd (Eqs. [12,15]) [16]. On the other hand, the transverse relaxation R2ρ,dd reaches its minimal value at α = 90°, and at this angle R2ρ,dd < R1ρ,dd. This feature is inherently different from the relationship between free precession relaxation rate constants R1 and R2, since R2 ≥ R1. It can be seen also from Figure 3a,b that the dependence of the rate constants on α is pronounced for τc > ~ 5·10-9 s, and becomes negligible for shorter correlation times (fast tumbling).

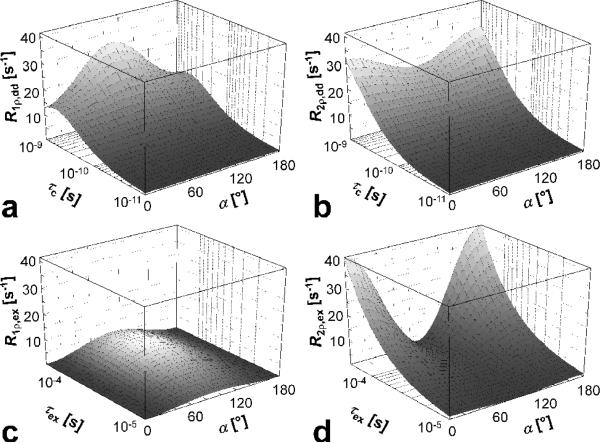

Figure 3.

Dependency of rotating frame relaxation rate constants on tilt angle a during CW SL pulse, for dipolar interactions (a,b) and for anisochronous exchange (c,d). The range of rotational correlation times (τc) and exchange correlation times (τex) were chosen in order to satisfy the weak field approximation and the fast exchange limit, respectively. The R1,2ρ,dd and R1,2ρ,ex values were obtained using Eqs. [12-13] and [21-22], respectively. The effective frequency was chosen as ωeff/(2π) = 2 KHZ. Other parameters: ω0/(2π) = 169 MHz, which corresponds to proton frequency at 4 T; δω = 0.85 ppm (= 170 Hz at 4 T), Pm = Pq = 0.5; r = 0.158 nm.

In Figure 3c,d the dependency of R1ρ,ex and R2ρ,ex on the exchange correlation time (τex) and the angle a are shown. The calculations were performed using Eqs. [21-22]. In the FXR, R1ρ,ex increases from zero to its maximum value and then decreases, reaching its maximum around τex = 2π/ωeff. In this region the greatest change of R1ρ,ex is observed. For R2ρ,ex a significant dependence of the rate constant on τex is apparent as the system moves toward the slower correlation times and approaches (still in the FXR) the intermediate exchange regime. On the other hand, in the fast exchange limit, R2ρ,ex → 0.

Dependency of rotating frame relaxation rate constants on ωeff

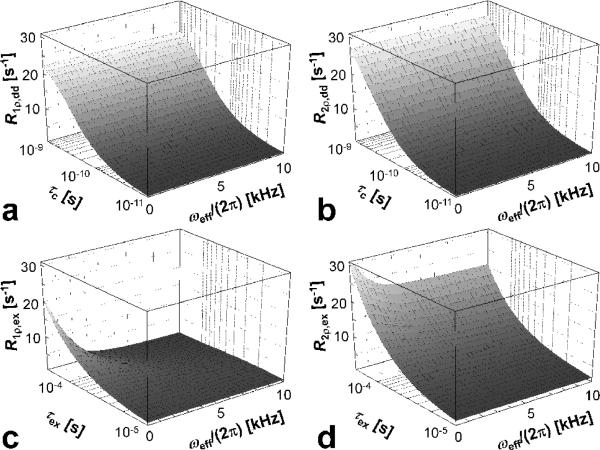

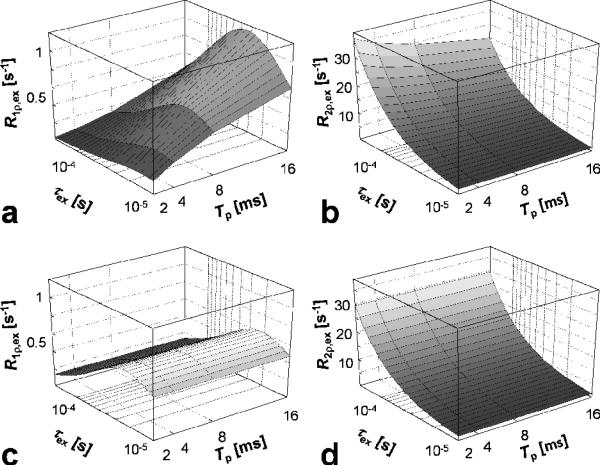

The dependencies of R1ρ,dd and R2ρ,dd during CW SL pulse on τc and ωeff are shown in Figure 4a,b for α = 45°. It can be seen that over a wide range of τc values in the fast tumbling regime [10-11-10-9] the dependence of the rate constants on ωeff (in the range of 0 < ωeff/(2π) < 10 kHz) is negligibly small at ω0/(2π) =169 MHz. On the other hand, the dependence of the relaxation rates on τc is pronounced. The exchange-induced relaxation rate constants, R1ρ,ex and R2ρ,ex, exhibit greatest change near τex = 2π/ωeff. Figure 4 c,d show a smaller change of R2ρ,ex as a function of ωeff as compared to the R1ρ,ex, as predicted by Eqs. [21-22]. Indeed, the dependence of R2ρ,ex on ωeff (the second term in Eq. [21]) is a factor of ½ smaller than the R1ρ,ex dependence on ωeff. As in the case for the dipolar interactions, the dependence of R1ρ,ex and R2ρ,ex on τex is pronounced.

Figure 4.

Dependency of rotating frame relaxation rate constants on ωeff/(2π) during CW SL pulse, for dipolar interactions (a,b) and for anisochronous exchange (c,d). The range of rotational correlation times (τc) and exchange correlation times (τex) were chosen in order to satisfy the weak field approximation and the fast exchange limit, respectively. The pulse frequency was placed off-resonance to satisfy the condition α = 45°. Other parameters: ω0/(2π) = 169 MHz, which corresponds to proton frequency at 4 T; δω = 0.85 ppm (= 170 Hz at 4 T), Pm = Pq = 0.5; r = 0.158 nm.

The generation of contrast with continuous-wave spin-lock

The dependency of rotating frame relaxations using CW SL pulses on α and ωeff provides the possibility to generate contrast in vivo. We have shown that the dependence of R1ρ and R2ρ on α is more significant as compared to ωeff in the fast motional regime. From a practical perspective, α can be changed by changing either or the frequency offset (Eq. [1]). In fact, it is common to apply the CW SL pulse both on- or off-resonance and with different power settings in order to obtain independent relaxation measurements, thus generating contrast in MRI [25,26]

D. 2 R1ρ and R2ρ during adiabatic rotation

In the following section, we describe relaxations during AFP pulses, when the adiabatic condition is well satisfied.

Dependency of rotating frame relaxation rate constants on pulse duration and bandwidth

In Figure 5 the dependencies of R1ρ,dd and R2ρ,dd on the time duration (Tp) and bandwidth (BW) of the AFP pulse are shown. The calculations demonstrate an important property of the frequency swept pulses: the relaxation rates are affected by how the frequency sweep is achieved during the pulse rather than for how long the AFP pulse is applied. Indeed, when Tp increases, but the time-bandwidth product (R-value) of the pulse is constant (Figure 5a,b), R1ρ,dd and R2ρ,dd change with Tp. In this case, when increasing Tp, the BW of the pulse decreases according to R/Tp (Eq. [7]). The maximum variation observed in the range of the correlation times investigated corresponds to ~25 % increase for R1ρ,dd and ~10% decrease for R2ρ,dd, when Tp increases from 2 to 16 ms, in the case of R-value = 80 and . As shown in Figure 5c,d, such variations are not observed increasing Tp for fixed BW, which is achieved by matching accordingly the R-value of the pulse (Eq. [7]). Similarly to R1,2ρ,dd, the exchange-induced relaxation rate constants (R1,2ρ,ex) depend on Tp when BW varies (Fig 6a,b), but remain constant when the R-value of the pulse scaled with Tp, keeping the BW constant (Figure 6c,d). Note that when both BW and are kept constant (Figure 6c), the maximum of R1ρ,ex occurs at the same τex for different Tp values.

Figure 5.

Dependency of rotating frame relaxation rate constants on the adiabatic pulse duration (Tp), in the presence of dipolar interactions. The adiabatic pulse was HS1. a,b) R-value = 80, thus resulting in BW = 40, 20, 10 and 5 kHz for Tp = 2, 4, 8 and 16 ms, respectively, according to the relationship BW = R/Tp; c,d) the R-values were adjusted to keep BW = 10 kHz, namely R-value = 20, 40, 80 and 160 for Tp= 2, 4, 8 and 16 ms, respectively. The peak RF amplitude was chosen to satisfy the adiabatic condition for all pulses investigated . The R1p,dd and R2p,dd values were calculated using Eqs. [12-13], with parameters: ω0/(2π) = 169 MHz and r = 0.158 nm. The range of rotational correlation times (τc) was chosen in order to satisfy the weak field approximation.

Figure 6.

Dependency of rotating frame relaxation rates on adiabatic pulse duration (Tp), in the presence of anisochronous exchange. The adiabatic pulse was HS1. a-d) as in Figure 5. The R1p,ex and R2p,ex were calculated according to Eqs. [11-13], respectively, with parameters: ω0/(2π) = 169 MHz, δω = 0.85 ppm (= 170 Hz at 4 T) and Pm = Pq = 0.5. The range of exchange correlation times (τex) was chosen in order to satisfy the fast exchange limit.

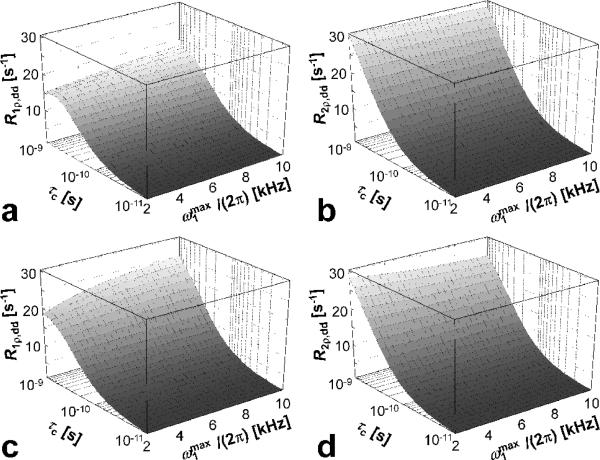

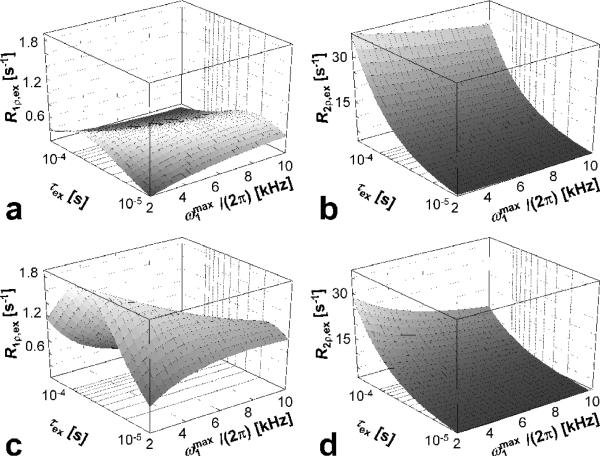

Dependency of rotating frame relaxation rate constants on and pulse modulation functions

The dependencies of R1ρ,dd and R2ρ,dd on are shown in Figure 7 a,b for the HS1 pulse and in Figure 7 c,d for the HS4 pulse. It can be seen that, in the range of between 2 - 10 kHz, R1ρ,dd increases by 20% for HS1 and by 44% for HS4, whereas R2ρ,dd decreases by 6% for HS1 and by 10% for HS4. The range of the chosen here ensures the adiabatic condition to be satisfied. The reason why relative changes are larger for HS1 compared to HS4 pulse originates from the different amplitude modulation functions of the pulses. The modulation functions of HS4 are in fact stretched versions of those used in HS1 (Figure 2a), and resemble more closely the case of a CW pulse, for which the dependency of rates on is maximum (Figure 4).

Figure 7.

Dependency of rotating frame relaxation rates on during the HS1 pulses (a,b) and the HS4 pulses (c,d), in the presence of dipolar interactions. For both pulses, R = 80 and Tp = 8 ms, corresponding to BW = 10 kHz. The R1p,dd and R2p,dd values were calculated using Eqs. [12-13], with parameters: ω0/(2π) = 169 MHz and r = 0.158 nm. The range of rotational correlation times (τc) was chosen in order to satisfy the weak field approximation.

As predicted by Eqs. [21-22], R1ρ,ex but not R2ρ,ex exhibits a Lorentzian - like dependency both on τex and on via its ωeff dependence (Figure 7). Similarly to the previous case of dipolar interactions, R2ρ,ex decreases with , and relative changes of R1ρ,ex and R2ρ,ex are larger for HS4 as compared to HS1 pulses.

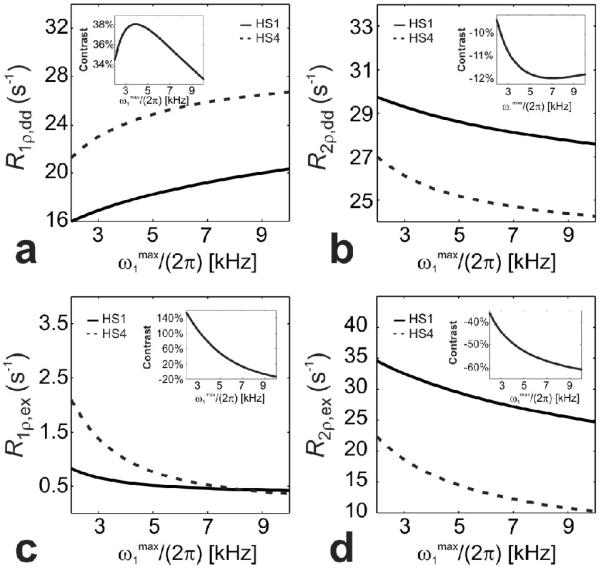

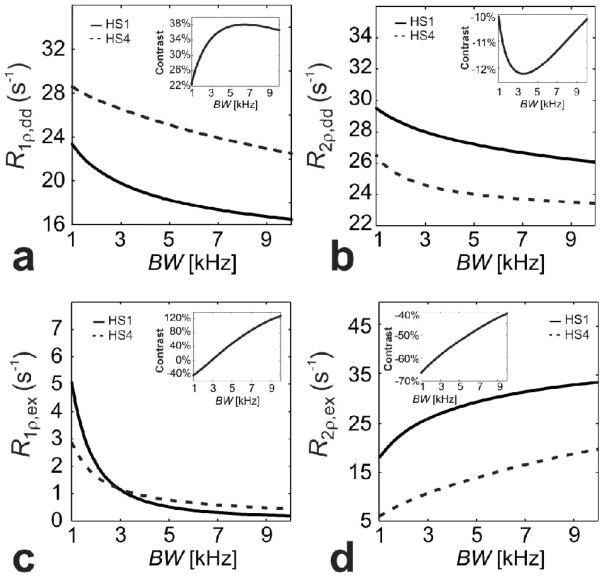

Generating contrast by altering the modulation functions of adiabatic pulses

Figures 9 and 10 show the contrast generated by HS1 and HS4 pulses in the case of dipolar interactions and anisochronous exchange, defined as (R1,2ρ,dd,ex(HS4) - R1,2ρ,dd,ex(HS1))/R1,2ρ,dd,ex(HS1)·100, as a function of at a fixed BW, and as a function of BW at a fixed , respectively. The plots demonstrate how the choice of BW and of HS1 and HS4 pulses can result in different contrasts. The contrast generated by different pulse modulation functions can be drastically different between anisochronous exchange and dipolar interaction at similar and BW, to the point that the contribution of one relaxation pathway can be eventually neglected from the contrast generated by alternating HS1 vs HS4 pulses. For instance, for the choice of intrinsic parameters shown in Figures 9 and 10, the R1ρ,ex contrast is zero when ~ 8 kHz (Figure 9c) and when BW ~ 3 kHz (Figure 10c).

Figure 9.

Comparison of rotating frame relaxation rate constants in the presence of dipolar interactions (a,b) and anisochronous exchange (c,d) as a function of during HS1 (solid lines) and HS4 (dashed lines) pulses, with BW = 10 kHz. The relaxation rate calculations were obtained, respectively, according to Eqs. [12-13] with parameters: ω0/(2π) = 169 MHz, r = 0.158 nm and τc = 10-9 s, and according to Eqs. [21,22] with parameters: ω0/(2π) = 169 MHz, δω = 0.85 ppm (= 170 Hz at 4 T) and Pm = Pq = 0.5 and τex = 2·10-4 s. The range of was chosen to satisfy the adiabatic condition. The insets depicts the % contrast defined as (R1,2p(HS4) - R1,2p(HS1))/R1,2p(HS1)·100.

Figure 10.

Comparison of rotating frame relaxation rate constants in the presence of dipolar interactions (a,b) and anisochronous exchange (c,d) as a function of BW during HS1 (solid lines) and HS4 (dashed lines) pulses, with . The relaxation rate calculations were obtained, respectively, according to Eqs. [12-13] with parameters: ω0/(2p) = 169 MHz, r = 0.158 nm and τc = 10-9 s, and according to Eqs. [21,22] with parameters: ω0/(2π) = 169 MHz, δω = 0.85 ppm (= 170 Hz at 4 T) and Pm = Pq = 0.5 and τex = 2·10-4 s. was chosen to satisfy the adiabatic condition. The insets depicts the % contrast defined as (R1,2r(HS4) - R1,2p(HS1))/R1,2p(HS1)·100.

To summarize, results from simulations show that MR contrast can be generated with adiabatic pulses by using different pulse modulation functions, different , and different amplitudes of the frequency sweep (A) of the AFP pulses, whereas the pulse length of the AFP pulse in itself does not affect the relaxations. The influence of these parameters on the rotating relaxation rate constants strongly depends on the relaxation channel. For example, whereas the dependency of R1,2ρ,dd on is relatively small (Figure 7), it becomes significant in the case of the anisochronous exchange (Figure 8). This may provide a possibility to separate relaxation mechanisms in vivo.

Figure 8.

Dependency of rotating frame relaxation rates on during HS1 pulse (a,b) and HS4 pulse (c,d), in the presence of an anisochronous exchange. For both pulses, R = 80 and Tp = 8 ms, corresponding to BW = 10 kHz. The R1p,ex and R2p,ex were calculated according to Eqs. [11-13], respectively, with parameters: ω0/(2π) = 169 MHz, δw = 0.85 ppm (= 170 Hz at 4 T) and Pm = Pq = 0.5. The range of exchange correlation times (τex) was chosen in order to satisfy the fast exchange limit.

E. Experimental Results

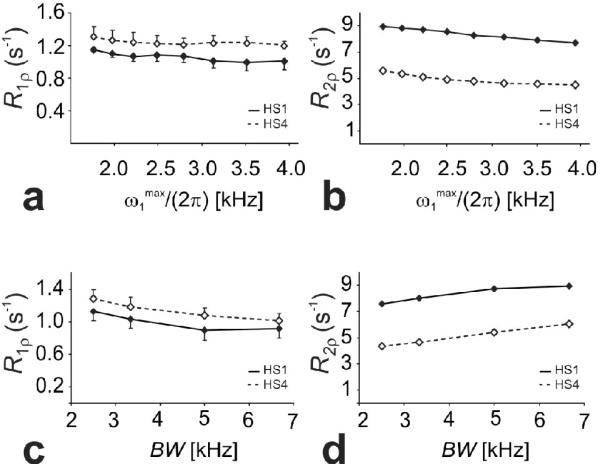

Results from the ethanol phantom (Figure 11) confirmed the theoretical predictions of the dependencies of adiabatic RR1ρ,ex and R2ρ,ex on (Figure 9c,d) and BW (Figure 10 c,d). In fact, R1ρr values decreased with both and BW, while R2ρ values decreased with but increased with BW. In addition, R1ρ,ex (HS4) was found to be greater than R1ρ,ex (HS1), while R2ρ,ex (HS4) was found to be smaller than R2ρ,ex (HS1).

Figure 11.

Adiabatic R1p and R2p as a function of and BW (c,d) measured from a phantom containing a mixture of water and ethanol at 4T during HS1 (bold symbols, solid lines) and HS4 (empty lines, dashed lines) pulses. The BW was varied by changing the amplitude of the frequency sweep, while remained constant (i.e. the pulse patterns were created using R = 15, 20 30 and 40)

Results from the human MRS experiments demonstrate that altering the modulation functions of the adiabatic pulses is the most effective way to generate contrast in vivo when changing the RF parameters of adiabatic pulses. Indeed, R1ρ and R2ρ values measured from the voxel localized in the visual cortex changed by 4% and -9% when increasing from 0.9 to 1.7 kHz at R-value = 10, respectively, and changed by 20% and 4% when increasing BW from 1.7 to 3.3 kHz at , respectively. However, differences in R1ρ and R2ρ values were considerably bigger, 63% and -13%, respectively, when alternating between the modulation functions of HS1 vs HS4 pulses at similar BW and .

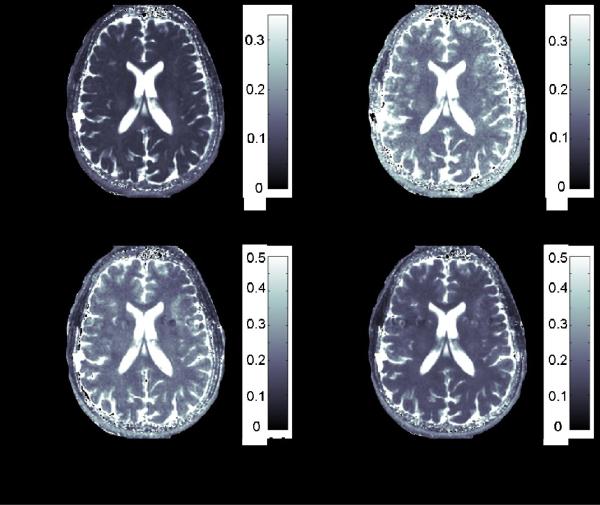

Results from the human MRI experiments were in agreement with theoretical predictions and with results obtained by MRS. In CW SL R1ρ experiments, varying the angle of the spin-lock α relatively to z' axis resulted in different R1ρ values (Figure 12a,b). Likewise, relaxation rates changed in adiabatic R1ρ experiments when varying the pulse modulation functions at constant BW and (Figure 12c,d). Specifically, the average CW SL T1ρ (= 1/R1ρ) values measured from an ROI localized in the visual cortex were (84 ± 9) ms and (163 ± 20) ms for α = 0° and 45°, respectively; the average adiabatic T1ρ values from the same ROI were (231 ± 30) ms and (160 ± 14) ms for HS1 and HS4 pulses, respectively.

Figure 12.

T1p (= 1/R1p) relaxation maps from the human brain at 4T. a) SL T1p map obtained with on resonance CW irradiation and ; b) SL T1p map obtained with CW irradiation off resonance by 0.625 kHz and , which corresponds to α = 45°; c) adiabatic T1p map obtained with HS1 pulse, R-value = 20, ; d) adiabatic T1p map obtained with HS4 pulse, R-value = 20, , Tp = 6 ms.

F. Contrast generated by spin-lock and adiabatic pulses: a practical perspective

Rotating frame relaxation methods offer a powerful tool to generate MR contrast in vivo which can assess motional regimes relevant for biological applications. Notably, by proper modeling of the relaxation processes (see section B), the simultaneous analysis of several independent measurements of R1,2ρ obtained with different experimental settings of the RF irradiation potentially allows the extraction of fundamental relaxation parameters, as for instance rotational, translational or exchange correlation times. The estimation of these fundamental parameters holds great potential to quantitatively characterize the functionality of the tissue in vivo, since the intrinsic relaxation parameters might provide sensitive markers to differentiate healthy from diseased state [25]. Due to enhanced sensitivity to slow molecular motion as compared to the free precession relaxation rates, R1ρ MRI has proven to be sensitive to different factors related to cell death in several experimental disease models [27,28]. For example, in rat models of cerebral ischemia, the change in R1ρ relaxation measurements were associated with the tissue changes resulting from cessation of blood flow [29]. Importantly, the acute changes in R1ρ correlated with the outcome of the tissue even in those cases where initial changes in water diffusion transiently recovered upon reperfusion [27,30]. R1ρ MRI has been shown to be useful in detecting cartilage degeneration [31], in revealing tissue damage occurring in the amygdala stimulation model of epilepsy [28], in characterizing neoplastic tissue [32] and in providing an early surrogate marker for treatment response in tumors receiving chemotherapy [32] or gene therapy [33]. However, clinical exploitation of R1ρ contrast using clinical scanners has been delayed because of several technical obstacles, such as high RF energy deposition into the tissue. In addition, the paucity of R2ρ relaxation studies in vivo is a consequence of experimental challenges affecting accurate measurements obtained with CW SL methods.

Whereas the CW SL method is particularly flexible due to its great sensitivity to experimental settings (RF amplitude and frequency offset), the in vivo implementation of CW SL sequences has been shown to be problematic due to a variety of experimental problems, such as uncertainty of tilt angles due to variations of B0 and B1 [34,35]. These artifacts could be partially removed by proper pulse sequence design, although often such techniques are not easily implementable on clinical scanners. In addition, even if in principle CW SL can utilize low locking power, at high magnetic field this choice might be insufficient to lock spins, thus leading to severe image artifacts. On the other hand, the utilization of high is limited by SAR. With respect to adiabatic pulses, contrast can be generated by using different pulse modulation functions (for example HS1 and HS4), , and BW. However, for in vivo applications in humans, the generation of the contrast based on increasing is not usually feasible. Indeed, for short pulse lengths (e.g., Tp = 2 ms) just the minimum that achieves adiabaticity can be beyond the achievable range of for human studies. Overall, the preferable choice to generate contrast in vivo by adiabatic pulses is by using different pulse modulation functions. Additionally, the insensitivity of the adiabatic pulses to B1 inhomogeneities makes the utilization of these methods advantageous as compared to CW SL. These properties of adiabatic pulses have been already used to generate tissue contrast in the human brain [5,6] and applied for treatment monitoring in rat glioma [26]. Some studies have shown that adiabatic rotating frame relaxation measurements can be more informative than T1 and T2 in detecting certain pathologic changes occurring in neurodegenerative diseases. For example, in a recent pilot study of patients with Parkinson's disease, adiabatic R2ρ was more sensitive than T2 to pathological changes occurring in the brain, which is likely due to iron accumulation in substantia nigra. In addition, adiabatic R1ρ reflected likely nigral neural degeneration [36], as confirmed by experiments performed on animal models of loss of dopaminergic neurons [37].

We conclude that changing the parameters of RF irradiation is a powerful and flexible tool to generate NMR contrast in the context of rotating frame relaxation measurements, which rely both on conventional spin lock methods and on adiabatic pulses. These methodologies offer potential to access water spin dynamics for addressing critical biological questions. However, several experimental limitations, ultimately related to SAR issues, need to be taken into account when applying both adiabatic and CW SL methodologies for human applications.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the following agencies for financial support: Instrumentarium Science Foundation (TL), Orion Corporation Research Foundation (TL), Finnish Cultural Foundation Northern Savo (TL), NIH grants P30 NS057091, P41 RR008079, R01NS061866 and R21NS059813.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abergel D, AG Palmer I. On the use of the stochastic Liouville equation in nuclear magnetic resonance: application to R1p relaxation in the presence of exchange. Concepts in Magnetic Resonance Part A. 2003;19A(2):134–48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis D, Perlman M, London R. Direct measurements of the dissociation-rate constant for inhibitor-enzyme complexes via the T1p and T2 (CPMG) methods. J Magn Reson B. 1994;104:266–75. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1994.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer M, Majumdar A, Zuiderweg E. Protein NMR relaxation: theory, applications and outlook. Progr NMR Spectr. 1998;33:207–72. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desvaux H, Berthault P. Study of dynamic processes in liquids using off-resonance RF irradiation. Progr NMR Spectr. 1999;35:295–340. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michaeli S, Grohn H, Grohn O, Sorce D, Kauppinen R, Springer C, Ugurbil K, Garwood M. Exchange-Influenced T2p contrast in human brain images measured with adiabatic radio frequency pulses. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:823–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michaeli S, Sorce D, Springer C, Ugurbil K, Garwood M. T1p MRI contrast in the human brain: modulation of the longitudinal rotating frame relaxation shutter-speed during an adiabatic RF pulse. J Magn Reson. 2006;181:138–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liepinsh E, Otting G. Proton exchange rates from amino acid side chains--implications for image contrast. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:30–42. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korzhnev D, Billeter M, Arseniev A, Orekhov V. NMR studies of Brownian tumbling and internal motions in proteins. Prog NMR Spectrosc. 2001;38:197–266. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garwood M, DelaBarre L. The return of the frequency sweep: designing adiabatic pulses for contemporary NMR. J Magn Reson. 2001;153:155–77. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michaeli S, Sorce D, Garwood M. T1p and T2p adiabatic relaxations and contrasts. Current Analytical Chemistry. 2008;4:8–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sorce D, Michaeli S, Garwood M. Relaxation During Adiabatic Radiofrequency Pulses. Current Analytical Chemistry. 2007;3:239–51. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silver M, Joseph R, Hoult D. Highly selective π/2 and π pulse generation. J Magn Reson. 1984;59:347–51. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tannus A, Garwood M. Improved performance of frequency-swept pulses using offset-independent adiabaticity. J Magn Reson A. 1996;120:133–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ostroff E, Waugh J. Multiple spin echo and spin locking in solids. Phys Rev Lett. 1966;16:1097–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solomon I. Rotary spin echoes. Phys Rev Lett. 1959;2:301–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blicharski J. Nuclear magnetic relaxation in rotating frame. Acta Physica Polonica. 1972;A41:223–36. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones G. Spin-Lattice Relaxation in the Rotating Frame: Weak Collision Case. Physical Review. 1966;148:332–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michaeli S, Sorce D, Idiyatullin D, Ugurbil K, Garwood M. Transverse relaxation in the rotating frame induced by chemical exchange. J Magn Reson. 2004;169:293–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorce D, Michaeli S, Garwood M. The time-dependence of exchange-indiced relaxation during modulated radio-frequency pulses. J Magn Reson. 2006;179(1):136–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abragam A. Principles of nuclear magnetism. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McConnell H. Reaction rates by nuclear magnetic resonance. J Chem Phys. 1958;28:430–1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levitt M, Freeman R, Frenkel T. Broadband heteronuclear decoupling. J Magn Reson. 1982;47:328–30. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaughan JT, Hetherington HP, Otu JO, Pan JW, Pohost GM. High frequency volume coils for clinical NMR imaging and spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 1994;32:206–18. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910320209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grohn OH, Makela HI, Lukkarinen JA, DelaBarre L, Lin J, Garwood M, Kauppinen RA. Onand off-resonance T1p MRI in acute cerebral ischemia of the rat. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:172–6. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jokivarsi KT, Niskanen JP, Michaeli S, Grohn HI, Garwood M, Kauppinen RA, Grohn OH. Quantitative assessment of water pools by T1p and T2r MRI in acute cerebral ischemia of the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:206–16. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sierra A, Michaeli S, Niskanen JP, Valonen PK, Grohn HI, Yla-Herttuala S, Garwood M, Grohn OH. Water spin dynamics during apoptotic cell death in glioma gene therapy probed by T1r and T2r. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:1311–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grohn O, Lukkarinen J, Silvennoinen M, Pitkanen A, Zijl Pv, Kauppinen R. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging assessment of cerebral ischemia in rat using on-resonance T1 in rotating frame. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:268–76. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199908)42:2<268::aid-mrm8>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pitkanen A, Nissinen J, Nairismagi J, Lukasiuk K, Grohn O, Miettinen R, Kauppinen R. Progression of neuronal damage after status epilepticus and during spontaneous seizures in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Prog Brain Res. 2002;135:67–83. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(02)35008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kettunen M, Grohn O, Penttonen M, Kauppinen R. Cerebral T1p relaxation time increases immediately upon global ischemia in the rat independently of blood glucose and anoxic depelarization. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:565–72. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grohn O, Kettunen M, Makela H, Penttonen M, Pitkanen A, Lukkarinen J, Kauppinen R. Early detection of irreversible cerebral ischemia in the rat using dispertion of the MRI relaxation time, T1p. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:1457–66. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200010000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duvvuri U, Goldberg A, Kranz J, Hoang L, Reddy R, Wehrli F, Wang A, Englander S, Leigh J. Water magnetic relaxation dispersion in biological systems: the contribution of proton exchange and implications for the noninvasive detection of cartilage degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12479–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221471898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duvvuri U, Poptani H, Feldman M, Nadal-Desbarats L, Gee M, Lee W, Reddy R, Leigh J, Glickson J. Quantitative T1p magnetic resonance image of RIF-1 tumor in-vivo:detection of early response to cyclophosphamid therapy. Cancer Research. 2001;61:7747–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hakumaki J, Grohn O, Tyynala K, Valonen P, Yla-Hertuala S, Kauppinen R. Early gene therapy-induced apoptotic response in BT4C gliomas by magnetic resonance relaxation T1 in the rotating frame. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9:338–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Witschey WR, 2nd, Borthakur A, Elliott MA, Mellon E, Niyogi S, Wallman DJ, Wang C, Reddy R. Artifacts in T1ρ-weighted imaging: compensation for B1 and B0 field imperfections. J Magn Reson. 2007;186:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witschey WR, Borthakur A, Elliott MA, Mellon E, Niyogi S, Wang C, Reddy R. Compensation for spin-lock artifacts using an off-resonance rotary echo in T1rhooff-weighted imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:2–7. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michaeli S, Oz G, Sorce D, Garwood M, Ugurbil K, Majestic S, Tuite P. Assessment of brain iron and neuronal integrity in patients with Parkinson's disease using novel MRI contrasts. Movement Disorders. 2007;22:334–40. doi: 10.1002/mds.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michaeli S, Burns TC, Kudishevich E, Harel N, Hanson T, Sorce DJ, Garwood M, Low WC. Detection of neuronal loss using T1ρ MRI assessment of 1H2O spin dynamics in the aphakia mouse. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2009;177:160–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]