Abstract

Integral membrane proteins are amphiphilic molecules. In order to enable chromatographic purification and crystallization, a complementary amphiphilic microenvironment must be created and maintained. Various types of amphiphilic phases have been employed in crystallizations and intricate amphiphilic microenvironmental structures have resulted from these and are found inside membrane protein crystals. In this review the process of crystallization is put into the context of amphiphile phase transitions. Finally, practical factors are considered and a pragmatic way is suggested to pursue membrane protein crystallization trials.

Keywords: Membrane protein crystallization, Amphiphile, Crystal packing, Lipid, Detergent

1. Introduction

Integral membrane proteins are amphiphilic molecules, they “love both”, water as well as oil. This duality is rooted in the physical nature of their surfaces: they all possess two fundamentally different types of surfaces, a hydrophobic perimeter and two hydrophilic caps (Fig. 1). While soluble proteins interact with water molecules and ions in an aqueous medium, membrane proteins do this only with a fraction of their surface. The hydrophobic perimeter faces alkyl chains of lipids and hydrophobic surfaces of other integral membrane proteins. Indeed, both of these media need to be arranged within certain dimensions into a suitable microenvironment in order to maintain the native conformation of the protein molecule. However, having individual particles is required to subject these proteins to chromatographic purification procedures and to arrange them into well-ordered three-dimensional arrays, crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction experiments. These particles have to be free to translate and rotate in space to bind, aggregate, form a crystal nucleus and associate with the faces of a growing crystal. The restrictions set by these two requirements, (i) maintaining an amphiphilic microenvironment and, (ii) allowing essentially free diffusion of small units are severe and are at the heart of the challenge to grow crystals of integral membrane proteins.

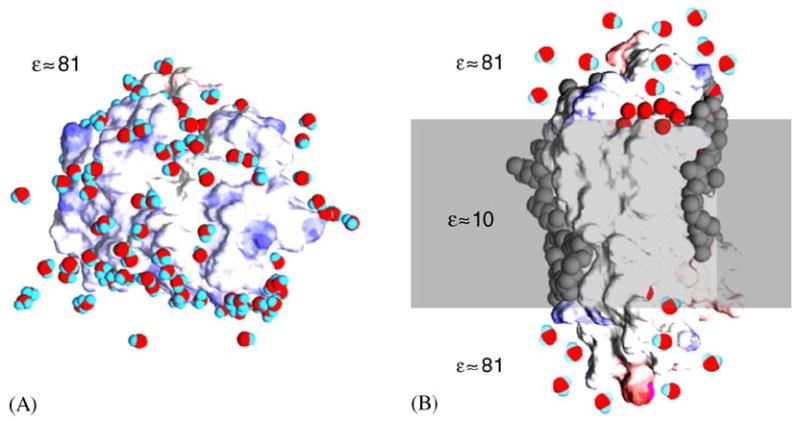

Fig. 1.

Schematic depiction of a soluble protein and a transmembrane protein in their native environment, an aqueous solution and a membrane bilayer, respectively. Both models are based on high-resolution X-ray crystallographic experimental structures showing protein, water and lipids. Water molecules are red and blue, the surface of the protein is blue where there is negative charge and red where there is positive charge, hydrophobic core and lipids are colored gray. (A) Soluble protein particles are dissolved in a homogenous medium with a dielectric constant ε close to that of distilled water. On their surface they interact with water molecules and with ions. (B) Integral protein particles are dissolved a low dielectric amphipilic medium, the lipid bilayer membrane, contacting the hydrophobic core, while their hydrophilic caps are exposed to an aqueous medium similar to that shown in A for soluble proteins.

Nonetheless, many membrane protein crystallizations have been reported (for a current update on published membrane protein structures visit http://www.mpibp-frankfurt.mpg.de/michel/public/memprotstruct.html or http://blanco.biomol.uci.edu/Membrane_Proteins_xtal.html) and it is the goal of this review to point out practical as well as theoretical considerations these crystallizations are based on. The focus is on highlighting the delicate interplay between small molecule amphiphiles, detergents and lipids, and integral membrane proteins before, during and after crystallization.

The critical role of amphiphiles in crystallization cannot be fully addressed in the context of this review and the reader is therefore directed to reviews and monographs by Garavito and Ferguson-Miller (2001), Garavito and Picot (1990), Wiener (2001), Michel (1983, 1991), Hunte et al. (2003) and Iwata (2003). For a fundamental introduction to the physical chemistry of detergents consult Tanford (1980), Rosen (1978) and Wennerstroem and Lindman (1979).

2. Amphiphilic microenvironments conducive to crystallization

The first reports of successful membrane protein crystallizations (Michel and Oesterhelt, 1980; Henderson and Shotton, 1980; Garavito and Rosenbusch, 1980) created a paradigm for membrane protein crystallization: transfer membrane proteins from their native environment into particulate detergent micelles in order to purify and to crystallize them in the same way as soluble proteins. It was reasoned that homogenous, lipid-free protein detergent micelles of uniform size would be most suitable for crystallization experiments. At the time the choice of the detergent for crystallization purposes was based on three factors: (i) stabilization of the native conformation of the membrane protein in monodisperse form, (ii) enabling protein–protein contacts in the packed crystal and, (iii) preventing detrimental phase separations during crystal growth. This line of thinking was expanded in the recent years, particularly with respect to lipids being recognized as beneficial and sometimes crucial crystallization components.

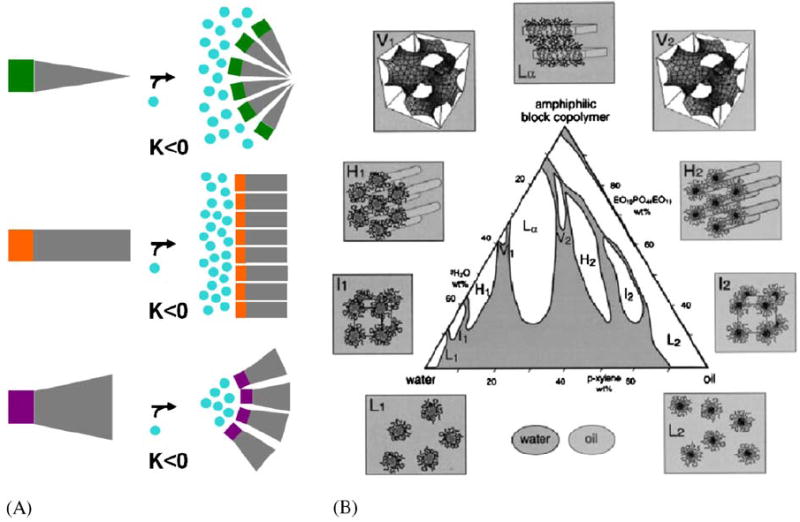

Most detergents belong into one of the following categories: ionic, non-ionic or zwitterionic. Their characteristic behavior depends on their shape, stereochemistry of the head group and tail. According to the ‘intrinsic curvature hypothesis’ (Gruner, 1985) they form supramolecular structures in water due to the hydrophobic effect (Tanford, 1980) and their shape (Fig. 2A). At sufficiently high concentrations, i.e. above the critical micellar concentration (CMC), detergents form micelles. These form roughly spherical objects in which detergent molecules are primarily packed with their alkyl chains towards the center and their head groups towards the surface (Rosen, 1978; Wennerstroem and Lindman, 1979). Detergent molecules in these micelles are flexible and exhibit a high degree of mobility, allowing for dramatic fluctuations in overall micellar shape including deformations, fusion and fission (Tieleman et al., 2000). Amphiphiles generally display a rich phase behavior commonly described in phase diagrams (Fig. 2B). Detergents typically have consolute boundaries, separating a single-phase micellar region from a dual micellar phase, the latter of which consists of a detergent rich and a detergent depleted phase. At the cloud point a clear homogenous detergent solution turns turbid upon heating. Importantly, the addition of salt, variations of pH, etc. and in particular the introduction of additional components may have profound but essentially unpredictable effects on amphiphile phase behavior. The fact that a ‘simple’ ternary system consisting of oil, water and block co-polymer amphiphile may form nine different isothermal phases spectacularly illustrates this polymorphism that is a typical feature of amphiphiles (Alexandridis et al., 1998). Lipid polymorph phases include fluid isotropic phases, planar, positively and negatively curved bilayer phases, rod-shaped hexagonal phases, micellar phases and bicontinuous cubic phases (Epand, 1997) and they occur, among other things, as a function of composition, hydration, pressure, and temperature.

Fig. 2.

Introduction to small molecule amphiphile classes and an example for amphipile polymorphism. (A) According to the ‘intrinsic curvature hypothesis’ (Gruner, 1985) amphiphiles form supramolecular structures in water due to the hydrophobic effect (Tanford, 1980). In this simplistic view the shape, more specifically the ratio of cross section of hydrophilic headgroup and hydrophobic tail, determines the type of structure they self-assemble into. I.e. wedge-shaped amphiphiles assemble into structures with positive Gaussian curvature K such as micelles, cylinder-shaped amphiphiles assemble into structures with zero Gaussian curvature K such as planar lipid bilayers and, cone-shaped amphiphiles assemble into structures with negative Gaussian curvature K such as bicontinuous cubic phases. (B) Amphiphiles may adopt a multitude of such supramolecular assemblies, macroscopic phases when mixed with water. For a particular three component system, oil, water, amphiphilic block copolymer, Alexandris et al. (1998) describe a record nine different isothermal phases including four cubic, two hexagonal and one lamellar lyotropic liquid crystalline phase and two micellar solutions.

Some integral membrane proteins may be introduced into detergent micelles via refolding (Dornmair et al., 1990). Indeed, since β-barrel proteins can be expressed in Escherichia coli as inclusion bodies, membrane proteins such as OmpA or NspA can be purified in unfolded form and crystallized without ever having had contact with lipids (Pautsch and Schulz, 1998; Buchanan, 1999), thus ensuring that once reconstituted into detergent micelles they form true detergent–protein micelles (Fig. 3A).

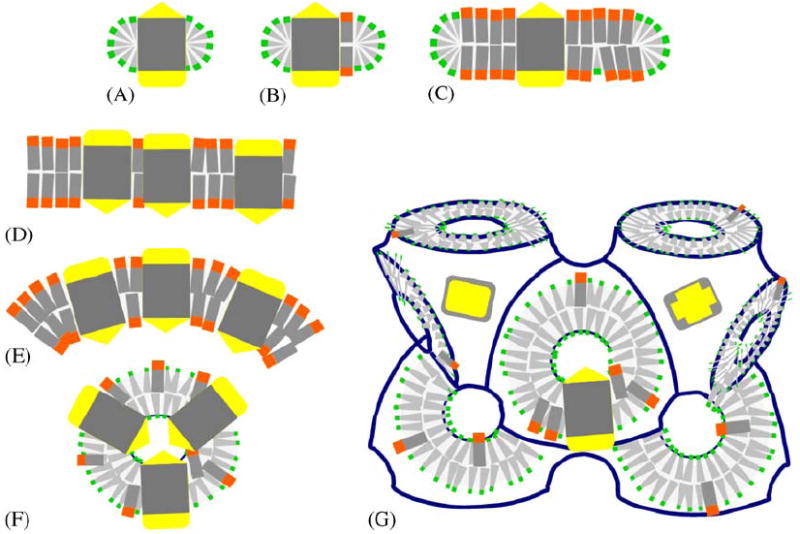

Fig. 3.

Schematic depiction of different amphiphilic micro-environments that membrane proteins have been incorporated into for crystallization purposes. Membrane proteins are shown with two hydrophilic caps (yellow) and a hydrophobic core (gray), and lipids (orange head) and detergents (green head) provide discrete (A, B, C) or continous (D, E, F, G) amphiphilic assemblies. (A) Protein detergent micelle; (B) Protein detergent complex (PDC); (C) Bicelle protein complex; (D) Planar membrane bilayer with embedded protein; (E) Curved proteoliposome; (F) High-curvature regular spherical shell assembly; (G) Membrane proteins reconstituted in bicontinuous curved membranes of a lipidic cubic phase of the diamond type. In all of these structures the amphiphile molecules are highly mobile (Zulauf, 1991) and thus constitute a ‘fluid’ hydrophobic host medium in which the integral membrane protein is embedded.

In most cases however, membrane proteins are extracted concomitantly with associated lipids from their native environment, cellular membranes. Such mixed systems, consisting of detergent, lipids and membrane proteins form the so-called, protein detergent complexes (PDCs) (Fig. 3B). The phase behavior of PDCs is expectedly complex and only in some select cases portions of phase diagrams have been mapped out. It is this state however that is usually employed in membrane protein crystallization trials and in many cases detergents as well as lipids are present in membrane protein crystals (Table 1). Two methodological advances have substantially aided many membrane protein crystallizations based on PDCs: (i) the introduction of small amphiphiles such as 1,2,3-heptanetriol to modify micelle dynamics and size (Michel, 1983) and, (ii) the increase of the size of the hydrophilic portion by complexing with monoclonal antibodies or fragments thereof (Iwata et al., 1995; Hunte and Michel, 2002).

Table 1.

Amphiphile moieties detected by X-ray diffraction in membrane protein crystals reported in the protein data bank

| Protein and organism | Attributed identity | Reference and PDB accession code |

|---|---|---|

| Photosynthetic reaction centre, Rhodopseudomonas viridis | Lauryl dimethylamine-N-Oxide | Lancaster et al. (2000) (1DXR) |

| Photosynthetic reaction centre, Rhodobacter sphaeroides | Di-Stearoyl-3-SN-Phosphatidylcholine cardiolipin | Camara-Artigas et al. (2002) (1M3X) |

| Photosynthetic reaction centre, Thermochromatium tepidum | Di-Palmitoyl-3-SN-phosphatidylethanolamine lauryl dimethylamine-N-oxide | Nogi et al. (2000) (1EYS) |

| Photosynthetic reaction centre, Thermosynechococcus elongates | Dodecyl-beta-D-maltoside | Ferreira et al. (2004) (1S5L) |

| Photosystem I, Synechococcus elongatus | 1,2-Distearoyl-monogalactosyl-diglyceride 1,2-Dipalmitoyl-phosphatidyl-glycerole | Jordan et al. (2001) (1JB0) |

| Bacteriorhodopsin, Halobacterium salinarum | 2,10,23-Trimethyl-tetracosane 1-[2,6,10.14-Tetramethyl-hexadecan-16-YL]- 2-[2,10,14-Trimethylhexadecan-16-YL] glycerol | Luecke et al. (1999) (1C3W) |

| Bacteriorhodopsin, Halobacterium salinarum | O3-Sulfonylgalactose | Essen et al. (1998) (1BRR) |

| Halorhodopsin, Halobacterium salinarum | 1-Monooleoyl-RAC-glycerol palmitic acid | Kolbe et al. (2000) (1E12) |

| Sensory Rhodopsin II, Natronobacterium pharaonis complexed with transducer fragment | B-Octylglucoside | Gordeliy et al. (2002) (1H2S) |

| Light-harvesting complex II, spinach chloroplasts | 1,2-Dipalmitoyl-phosphatidyl-glycerole Digalactosyl diacyl glycerol B-Nonylglucoside | Liu et al. (2004) (1RWT) |

| Light-harvesting complex 2, Rhodopseudomonas acidophila | B-Octylglucoside | Papiz et al. (2003) (1NKZ) |

| Cytochrome C Oxidase, Paracoccus denitrificans | Di-Stearoyl-3-SN-phosphatidylcholine | Harrenga and Michel (1999) (1QLE) |

| Cytochrome c oxidase, Paracoccus denitrificans | Lauryl dimethylamine-oxide | Ostermeier et al. (1997) (1AR1) |

| Cytochrome C oxidase, bovine heart mitochondria | Tristearoylglycerol decyl-beta-D-maltopyranoside | Tsukihara et al. (2003) (1V55) |

| Cytochrome C oxidase, Thermus thermophilus | B-Nonylglucoside | Soulimane et al. (2000) (1EHK) |

| Cytochrome C oxidase, Rhodobacter sphaeroides | Di-Stearoyl-3-SN-Phosphatidylethanolamine | Svensson-Ek et al. (2002) (1M57) |

| Cytochrome bc1 complex, Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1,2-Diacyl-SN-glycero-3-phoshocholine Di- Palmitoyl-3-SN-phosphatidylethanolamine 1,2-diacyl-SN-glycero-3-phosphoinositol undecyl-maltoside | Lange et al. (2001) (1KB9) |

| Cytochrome B6F, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | Eicosane 1,2-Distearoyl-monogalactosyl-diglyceride 1,2-DI-O-acyl-3-O-[6-deoxy-6-sulfo-alpha-D-glucopyranosyl]-SN-glycerol | Stroebel et al. (2003) (1Q90) |

| Fumarate reductase, Escherichia coli | O-Dodecanyl octaethylene glycol | Verson et al. (1999) (1FUM) |

| Fumarate reductase, Wolinella succinogenes | Dodecyl-beta-D-maltoside | Lancaster et al. (2001) (1E7P) |

| Succinate dehydrogenase, E. coli | Cardiolipin L-Alpha-phosphatidyl-beta-oleoyl-gamma-palmitoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine | Yankovskaya et al. (2003) (1NEK) |

| Potassium channels KcsA, Streptomyces lividans | Diacyl glycerol Nonan-1-ol | Valiyaveetil et al. (2002) (1K4C) |

| Rhodopsin, bovine rod outer segments | B-Nonylglucoside palmitoyl | Okada et al. (2002) (1L9H) |

| Aquaporin AQP1, bovine red blood cells | B-Nonylglucoside | Sui et al. (2001) (1J4N) |

| Glycerol facilitator GlpF E. coli | B-Octylglucoside | Fu et al. (2000) (1FX8) |

| Aquaporin Z, E. coli | B-2-Octylglucoside | Savage et al. (2003) (1RC2) |

| Chloride channels, E. coli | N-Octane pentadecane | Dutzler et al. (2002) (1KPL) |

| Formate dehydrogenase, E. coli | Cardiolipin | Jormakka et al. (2002) (1KQF) |

| Nitrate reductase A, E. coli | 1,2-Diacyl-glycerol-3-SN-phosphate | Bertero et al. (2003) (1Q16) |

| ADP/ATP carrier, bovine heart mitochondria | Cardiolipin di-Stearoyl-3-SN-phosphatidylcholine 3-Laurylamido-N,N′-dimethylpropylaminoxyde | Pebay-Peyroula et al. (2003) (1OKC) |

| Porin, Rhodopseudomonas blastica | (Hydroxyethyloxy)tri(ethyloxy)octane | Kreusch et al. (1994) (1PRN) |

| OmpK36 (osmoporin), Klebsiella pneumoniae | Dodecane | Dutzler et al. (1999) (1OSM) |

| OmpA-fragment, E. coli | (Hydroxyethyloxy)tri(ethyloxy)octane | Pautsch and Schulz (1998) (1BXW) |

| OmpX, E. coli | (Hydroxyethyloxy)tri(ethyloxy)octane | Vogt and Schulz (1991) (QJ8) |

| NspA, Neisseria meningitidis | Pentaethylene glycol monodecyl ether | Vandeputte et al. (2003) (1P4T) |

| FhuA, E. coli | 3-Deoxy-D-manno-OCT-2-ulosonic acid | Ferguson et al. (1998) (1FCP) |

| 2-Tridecanoyloxy-pentadecanoic acid | ||

| 3-Oxo-pentadecanoic acid | ||

| FhuA, E. coli | N-Octyl-2-hydroxyethyl sulfoxide | Locher et al. (1998) (1BY3, 1BY5) |

| FhuA, E. coli | Decylamine-N,N-dimethyl-N-oxide Lauric acid 3-Hydroxy-tetradecanoic acid 3-Deoxy-D-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid Myristic acid | Ferguson et al. (2000) (1QFF) |

| Ferric citrate transporter (FecA) E. coli | Lauryl dimethylamine Heptane | Ferguson et al. (2002) (1KMO) |

| Cobalamine transporter BtuB, E. coli | (Hydroxyethyloxy)tri(ethyloxy)octane | Chimento et al. (2003) (1NQF) |

| outer membrane phospholipase A (OMPLA), E. coli | B-Octylglucoside | Snijder et al. (1999) (1QD5) |

| protease OmpT, E. coli | B-Octylglucoside 2-Methyl-2,4-pentanediol | Vandeputte-Ruttenet al. (2001) (1I78) |

| Outer-membrane adhesion OpcA, Neisseria meningitidis | Pentaethylene glycol | Prince et al. (2002) (1K24) |

| Long-chain fatty acid transporter FadL, E. coli | (Hydroxyethyloxy)tri(ethyloxy)octane Lauryl dimethylamine-N-oxide | van den Berg et al. (2004) (1T16) |

The proteins listed represent a subset of currently determined membrane protein structures and they were selected to document the variability and abundance of lipids and detergents found in membrane protein crystals (the list was built from http://www.mpibp-frankfurt.mpg.de/michel/public/memprotstruct.html, version of June 29th, 2004, 75 entries). The identification of the complete structure of these amphiphiles is somewhat tentative. At resolutions above 2.5 Å crystallographers often resort to interpreting weak electron density maps around the hydrophobic perimeter of membrane proteins with the crystallization condition in mind, e.g. what detergent was used. However, in several cases the identity of amphiphiles were carefully determined independently (Belrhali et al., 1999; Essen et al., 1998).

The range of alternative amphiphilic vehicles for membrane proteins useful for crystallization purposes has increased in the recent years. Besides protein–detergent micelles and PDCs, membrane protein crystallizations were started from membraneous structures. The latter may be obtained by adding lipids to create structures that are small in size and planar such as bicelles (Faham and Bowie, 2002) (Fig. 3C) or that are large such as in extended planar membranes (Fig. 3D) or those that exhibit positive (Figs. 3E, F), or negative curvature (Fig. 3G). Curved membrane protein containing bilayers include proteoliposomes (Takeda et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2004) or bincontinuous lipidic cubic phases (Landau and Rosenbusch, 1996). Of course, the quantity and type of lipid added to PDCs determine the nature of the resulting amphiphile phase.

For some membrane proteins it is very difficult to identify detergent-based conditions that preserve their native conformation. This predicament has inspired several research groups to expand the range of solubilization tools by designing new amphiphiles and to investigate the richness of their phase behavior for the purpose of membrane protein crystallization (Fig. 4). Among these amphiphiles are the so-called peptitergents (Schafmeister et al., 1993), lipopeptide detergents (McGregor et al., 2003), amphiphols (Tribet et al., 1996; Popot et al., 2003) and new detergents with reduced alkyl chain mobility such as tripod amphiphiles (Yu et al., 2000). They all self-assemble into small micelles, can disperse lipid membranes and are gentle, non-denaturing amphiphiles preserving the native structure of the test protein bacteriorhodopsin and other membrane proteins in solution for extended periods of time.

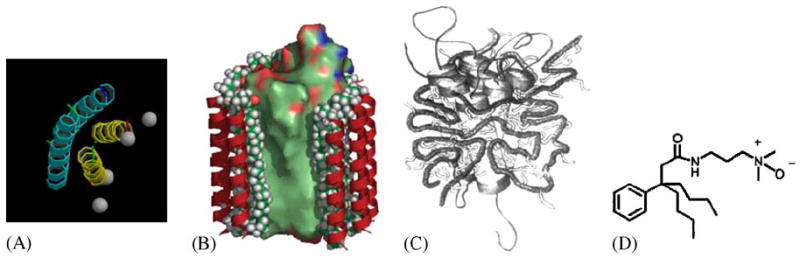

Fig. 4.

Cartoons of recently developed new classes of amphiphile molecules. (A) Peptitergents are designed peptides that form amphiphatic α-helices. Their hydrophobic faces were made to interact with the hydrophobic face of integral membrane proteins (Schafmeister et al., 1993). (B) Lipopeptides consist of a peptide scaffold supporting two alkyl chains each anchored at the end of an α-helix. They were designed to provide a rigid outer hydrophilic shell surrounding an inner ‘soft’ lipidic core (McGregor, 2003). (C) Amphiphols are amphiphilic polymers with a hydrophilic backbone and hydrophobic grafted chains. They exhibit favorable phase transitions that are expected to be useful for membrane protein crystallization experiments (Tribet et al., 1996). (D) The design of tripod amphiphiles such as #8 in Yu et al. (2000) is based on the rationale that detergents with diminished flexibility should be more prone to form ordered crystal lattices. The core is a terasubstituted carbon atom that limits the flexibility of three attached hydrophobic and a hydrophilic substitutent.

3. The amphiphilic microenvironment inside membrane protein crystals

Membrane protein crystals consist of three major molecular species: water, amphiphile and membrane protein. Water and dissolved solutes form a fluid phase within the rigidly packed protein network, while amphiphiles may tightly bind to the protein surface and/or form a disordered state. The morphology and the strength of intermolecular contacts in protein crystals were investigated by Matsuura and Chernov (2003). It was found that soluble proteins form crystal contacts frequently involving water molecules, which form specific intermolecular hydrogen bonds on top of non-specific attractive electrostatic interactions. Similar contacts are present between hydrophilic protein surfaces of membrane proteins in crystals. In some cases amphiphiles form interactions that are crucial to crystal packing.

The structures that amphiphiles from within membrane protein crystals are remarkably diverse (Fig. 5) and go beyond the simple two-type classification introduced by Michel (1983). According to these categories type I crystals consist of stacked membraneous layers (Fig. 5B). They stick together via hydrophobic interactions in the plane of the layers, resembling 2D crystals, and polar contacts mediate interlayer interactions. Conversely, type II crystals possess contacts involving the polar regions of membrane proteins only. The hydrophobic perimeter is embedded in a torus of detergent molecules. Typical type I crystals have been found in all cases where membrane proteins were crystallized with the cubic phase method (Landau and Rosenbusch, 1996; Kolbe et al., 2000; Royant et al., 2001; Katona et al., 2003). Subtle differences in symmetry and layer arrangement exist though. Bacteriorhopsin packs in a unidirectional way “head to tail” (Belrhali et al., 1999), while halorhodopsin packs in layers where heads interact with heads and tails with tails (Kolbe et al., 2000), and sensory rhodopsin II packs in layers with mixed up–down arrangements (Royant et al., 2001). Bacteriorhodopsin crystals were shown by mass spectrometry to contain native lipids that were co-purified, namely 2,3-di-O-phytanyl derivatives of phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylglycerol sulfate, phosphatidylglycerol phosphate methylester, triglycosyldiether, sulfated triglycoside lipid and sulfated tetraglycosyldiphytanylglycerol (Belrhali et al., 1999) when crystallized from lipidic cubic phases and they contained similar lipids when crystallized as PDCs (Essen et al., 1998). A detailed description of the interaction of lipids within bacteriorhodopsin crystals is provided by Belrhali et al. (1999) and by Cartailler and Luecke (2003).

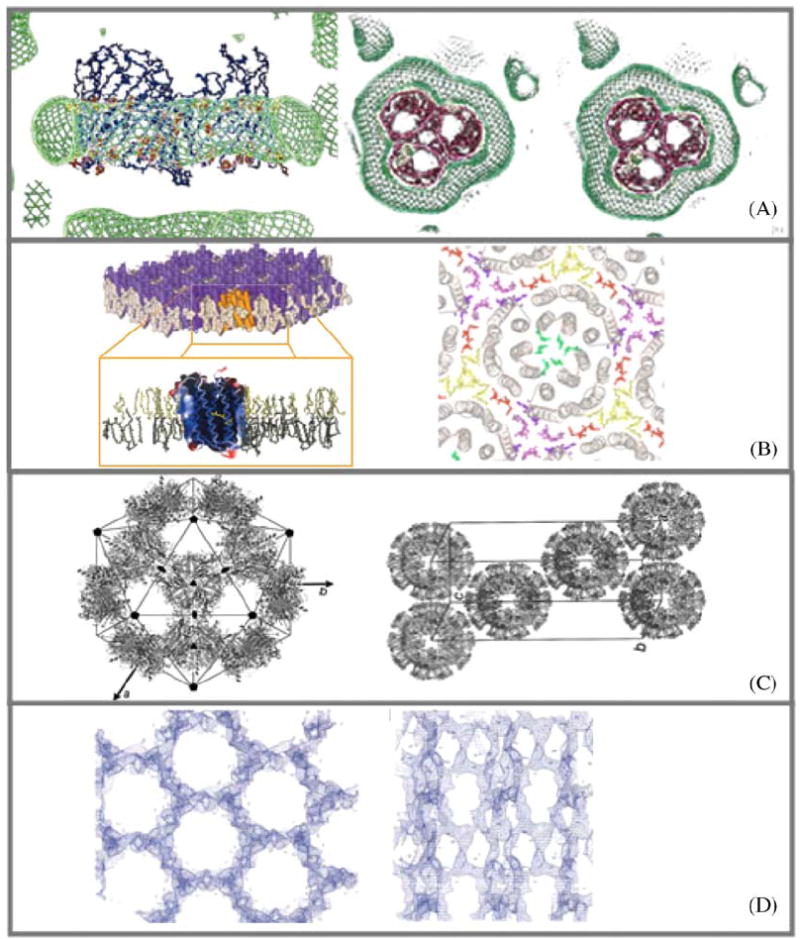

Fig. 5.

Samples of experimentally determined and deduced amphiphile arrangements in crystals of membrane proteins. (A) ‘Type II’ discontinuous arrangement of micellar Octyl-POE around the hydrophobic perimeter of the detergent C8E4 and OmpF porin (E. coli) R3 crystal (Pebay-Peyroula et al., 1995). Protein detergent micelle with a belt of detergent as shown by neutron density (green). (B) ‘Type I’ continuous arrangement of stacked layers consisting of extended two-dimensional sheets of purple membrane (Halobacterium Salinarum). Bacteriorhodopsin trimers are separated in plane by a belt of native lipids (Belrhali et al., 1999). (C) Discontinuous icosahedral packing of spherical LHC-II proteoliposomes (Liu et al., 2004). (D) Continuous network of β-Octylglucoside extending throughout the entire P3121 crystal of phospholipase A OmplA (E. coli) (Snijder et al., 2003).

Recently Liu et al. (2004) have described crystals of the Light harvesting chlorophyll a/b protein complex from pea thylacoid membranes. Hollow spherical shell assemblies were produced and packed into well-ordered three-dimensional crystals (Fig. 5C). The icosahedral spheres have a diameter of 250 Å and contain 20 protein trimers and several disordered lipid molecules. Apparently the space between the LHC-II trimers in the icosahedral structure is completely filled with digalactosyl diacylglycerol and/or phosphatidylglycerol and/or nonylglucoside and thus resemble small proteoliposomes.

Snijder et al. (2003) describe the packing of outer membrane phospholipase A in crystals where a crystal-penetrating continuous three-dimensional detergent network exists (Fig. 5D). They denote this arrangement as type III. Here hydrophobic and polar contacts contribute to the integrity of the crystal.

It is instrumental to compare these packing arrangements with those that can form by small molecule amphiphiles themselves. Type I packing corresponds to lamellar phases, type II packing to micellar phases. Type III and the icosahedral shell packing do not have an immediate counterpart in amphiphile polymorph structures, however, continuous three-dimensional networks such as those formed in bicontinuous cubic phases share some structural and topological similarities with membrane protein crystals (Fig. 2B). This resemblance is not unexpected since one can understand the membrane protein as a modifying component of amphiphile polymorphism and phase behavior. Generally crystals represent lowest enthalpy states and in the case of these membrane protein/amphiphile co-crystals it is not clear which of the two components (membrane protein or amphiphile) dominates in providing crystal forming enthalpy.

4. Amphiphile phase transitions during crystallization

The crystallization process consists of two steps, nucleation and crystal growth. Nucleation is a critical phenomenon and hardly anything is known specifically for membrane protein crystallizations. Soluble protein crystallization growth is mainly driven by modification of the water structure, creating conditions that allow and favor the defined association of proteins (Kam et al., 1978; Weber, 1991). Similar conditions need to be created for the hydrophilic sections of membrane proteins, i.e. screening of repulsive electrostatic surface charges by ions and providing conditions where the protein is at supersaturation. The latter effect was investigated by Rosenow et al. (2003) who concluded from biochemical studies that membrane protein crystallization is favored with those amphiphiles that optimize the solubility of integral membrane proteins. At the same time conditions need to be provided that allow the hydrophobic sections to maintain or to rearrange into the suprastructures exemplified in Fig. 5. How is this achieved?

Crystallizations involve phase transitions: an initial homogenous medium separates into a depleted phase and a rich in amphiphile and membrane protein, the crystal (Fig. 6). The association of protein/detergent micelles or PDCs into a type II packed crystal can easily be understood within the framework of present crystallization theory. The mechanism for PDC crystallization was investigated by Marone et al. (1998) for Photosynthetic reaction centers. These were shown to exist predominantly in the monomeric form throughout the entire crystallization process. Small-angle neutron scattering experiments suggested that initial crystal nuclei are kinetically transient and thermodynamically unstable intermediates and single monomer complexes serve as crystal growth units. Comparable experiments were used to characterize the effects of crystallization additives on the shape of pure detergent micelles (Littrell et al., 2000). It was found that micelles were elongated and rod-like in form and that their size grew by increasing the ionic strength and shrunk when glycerol or PEG was added. Studies like these provide a rational basis for detergent-specific formulation screen development.

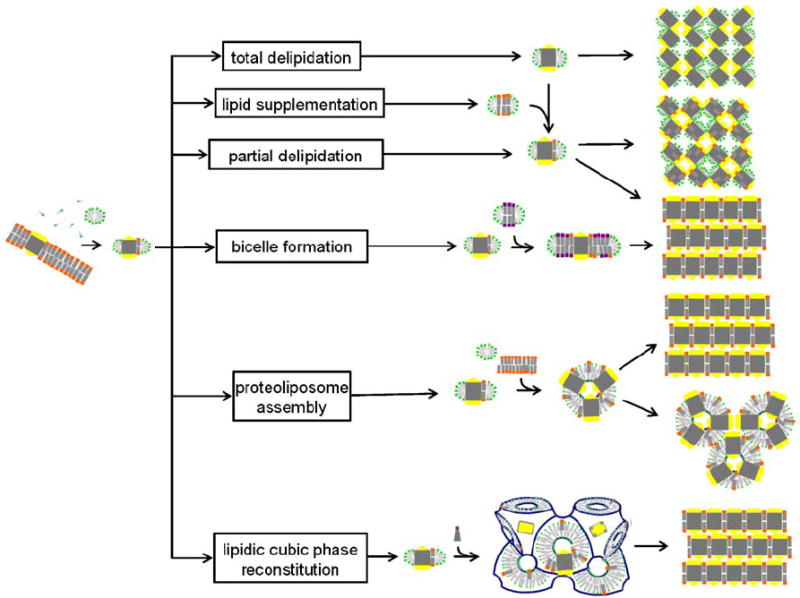

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of membrane protein crystallization concepts, routes and examples for the resulting packing arrangements. The detergent-solubilized membrane protein may be delipidated (Pautsch and Schulz, 1998) or may carry affine lipids throughout the purification process. Alternatively, membrane-forming lipids may be added to form a PDC, a protein/detergent/lipid complex (Zhang et al., 2003) or bicelles (Faham and Bowie, 2002). Structured amphiphilic phases can form when lipids with zero or negative spontaneous curvature are added to detergent solubilized membrane protein preparations. Proteoliposomes may fuse and form layered stacks or they may directly assemble into a regular array. Bicontinuous lipidic cubic phases can provide a matrix for embedding membrane proteins and allow these to nucleate and form layered crystals (Nollert et al., 2001).

In order to form continuous structures such as layered type I crystals or crystals with a continuous network of amphiphile phase, PDCs need to fuse and allow detergent and lipid molecules to rearrange into the supramolecular architecture described above. Snijder et al. (2003) point out that the continuous detergent network in their crystals and the hydrophobic crystal contacts suggest that OmplA molecules approach each other closely and coalesce their detergent belts. The formation of the polar contacts might actually drive crystallization and induce this merging of micelles. They hypothesized that micelle fusion and the stabilization of a continuous network is mediated by the organic solvent and the amphiphile 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol. Indeed, many of the putative type III crystal yielding conditions include the use of rather high concentrations of organic solvents or small molecule amphiphiles such as 1,2,3-heptanetriol. The picture emerges that this crystallization process may be driven partly or possibly be dominated by amphiphiles undergoing a phase transition prompted by the increase in system complexity.

The formation of regular bilayer stacks from bicelles may be understood along similar lines of reasoning (Faham and Bowie, 2002). An interesting twist though is brought about by the incorporation of membrane proteins into membrane-like vehicles (Figs. 3D–G). Doing so reduces two rotational degrees of freedom and one translational degree of freedom, effectively reducing the entropic penalty for crystallization. This penalty is paid already at the step of reconstitution, prior to the actual crystallization event and may thus positively offset enthalpic crystallization energy contributions.

The crystallization of LHC-II proteoliposomes is a special case with a significant contribution from the amphiphiles. The mechanism was explained as that of electrostatically driven particle aggregation (Hino et al., 2004). Spherical shell assemblies were not visible by electron microscopy prior to crystallization. However, when the KCl concentration was increased above 20 mM, spherical shell assemblies formed and above 30 mM KCl crystallization into octahedral crystals was observed. The authors speculate that it is not the protein but the amphiphiles that determine the small size of the proteoliposomes, i.e. by virtue of the asymmetric charge distribution on the protein and subsequent asymmetric association with charged lipids. Specifically, the predominantly negative charge on the stromal side faces outward and during the formation of proteoliposomes their electrostatic repulsion is shielded and allows the membrane curvature to increase. Ready built spheres then stack into octahedral crystals. Proteoliposomes may also fuse to layers, possible by a mechanism resembling biological fusion (Zhang et al., 2003).

The formation of type II crystals from initial homogenously dispersed membrane proteins in bicontinuous lipidic cubic phases was rationalized qualitatively as a phase separation process (Nollert et al., 2001) and a quantitative theory (Grabe et al., 2003) was developed based on this hypothesis. In short, it was shown that it is energetically favorable for membrane proteins to cluster together in flattened regions of the otherwise highly curved membrane of the cubic phase. A kinetic barrier model was developed that together with the energetics predicts a limitation of the lipidic cubic phase method to membrane proteins with more than five α-helices and confines a window for the cubic lattice parameter within which crystallization may occur.

5. Practical considerations

Hunte et al. (2003) and Iwata et al. (2003) provide very useful practical guides for bench scientists to attempt membrane protein crystallizations. Strategies for rational and random screen design and procedures for re-lipidation and lipid supplementation are summarized in this section.

Tools are currently being developed by several groups to design screens for specific amphipile systems. Piazza et al. (2002) aim at gaining control over the phase behavior of LDAO. They modulate the ionization of LDAO, a pH-sensitive surfactant, to phase segregate Photosynthetic Reaction Center by adjusting temperature, salt and pH. Tanaka et al. (2003) rationalize PEG-based cytochrome bc1 complex crystallizations with a simple model. They use dynamic light scattering to estimate interactions between PDCs of the bc1 complex. They control the stability of the liquid phase of BC1 solutions via the ratio of (the range of depletion zone)/(the radius of a BC1 particle). The subsequent crystallizations were most successful at conditions where the stability of the liquid phase changed from stable to unstable.

Apart from such detailed characterizations, membrane protein crystallographers have traditionally paid close attention to occurrences of phase separation (Michel, 1991; Wiener, 2001; Garavito and Ferguson-Miller, 2001). For instance, Trimeric Photosystem I from Cyanobacterium (Synechococcus elongates) can be isolated as PDCs with stereochemically pure β-dodecylmaltoside (Fromme and Witt, 1998) and crystals readily grow from small amphiphile-rich droplets during dialysis against low salt concentrations (Fromme, 2003). Supposedly these droplets form a separate, amphiphile and protein-rich phase and serve as nucleation and growth sites (P. Fromme, personal communication). It is possible that the crystallization mechanism resembles that hypothesized for the crystallization of bacteriorhodopsin in lipidic cubic phases.

Furthermore, crystallizers may systematically investigate amphiphile systems close to macroscopically observable phase separations and bias crystallization screening formulations towards conditions that produce such features (Hitscherich et al., 2001). Wiener and Snook (2001) for instance, base their screen development on the hypothesis that the properties of the pure detergent solutions and their phase behavior plays a significant role during the membrane protein crystallization process. They characterize detergent phase properties and utilize dye partitioning in detergent/solute mixtures to determine phase boundaries. Ultimately they arrive at new detergent-specific screening formulation kits.

Until recently membrane protein crystallizers faced a paradoxical situation. On one hand it was well established that lipids may aid the crystallization process with lipids regularly showing up in the final crystal (Table 1), on the other hand their identity and quantity are rarely reported in the methods section of the corresponding publications. This lack of critical information makes it very difficult to reproduce membrane protein crystallizations. Fortunately, simple procedures to monitor lipid and detergent in membrane protein samples have been worked out. daCosta and Baenziger (2003) describe using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy for this purpose. This method reduces the sample volume to 10 μl and molar lipid:protein ratios down to 5:1 (for a 300 kDa protein) can be determined. Their ratiometric assay utilizes the intensity of the lipid ester carbonyl band at 1740 cm−1 and the protein amide I band at 1650 cm−1. Detergent analysis can be included by observation of vibrations in the 1200–1000 cm−1 region and quantified using a standard curve.

Crucially, the types of lipids that membrane proteins are associated with originate form their host membrane. Therefore, lipid compositions in membrane protein sample preparations depend on tissue and cell types. For the insect cell baculovirus expression system the lipid profile was shown to vary as a function of cell line (Spodoptera frugiperda vs. Trichoplusia ni) and infection state (Marheineke et al., 1998). Lipid supplementation and its use for the crystallization of cytochrome b6f in defined protein–detergent–lipid complexes are described by Zhang et al. (2003). Crystallization of the delipidated protein was not possible but when supplemented with a synthetic, non-native lipid, dioleoyl-phosphatidylcholine, well-diffracting crystals formed. Similarly, five to 13 lipid molecules per protein particle were required for crystal formation of the human erythrocyte anion-exchanger membrane domain (Lemieux et al., 2002).

The advent of high-throughput crystallization techniques and microcrystallization methods (Santarsiero, 2002; Nollert, 2002) have helped substantially to cover larger portions of the multidimensional crystallization phase space and it is expected that membrane protein crystallization projects may be initiated even though only small amounts of protein samples can be produced.

Regardless of these and future latest ‘tips and tricks’—some membrane proteins crystallize more readily than others. In this respect, bacteriorhodopsin has been named ‘the lysozyme of membrane proteins’. It can be crystallized starting from purple membranes, from PDCs or proteoliposomes (Fig. 3) with several crystallization methods (Fig. 7). Unfortunately, not every membrane protein is that well-behaved.

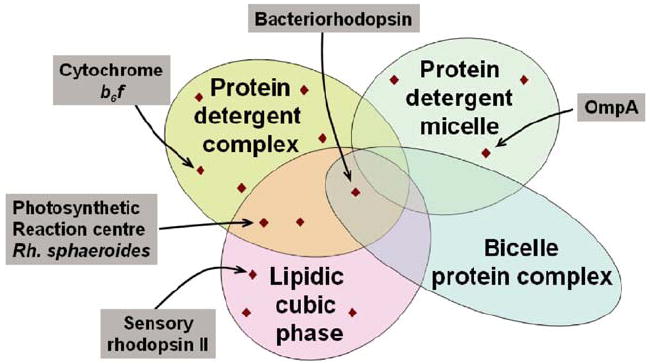

Fig. 7.

Venn diagram schematizing crystallization method space. Depicted are four different amphiphilic micro-environments that support membrane protein crystallization. For illustration purposes representative examples are pointed out.

6. Conclusions

The rate at which new membrane protein structures are reported has steadily increased over time. This progress should be attributed to a greater willingness of investigators to initiate such projects, shifts in funding preferences and in the availability of molecular biological methods, i.e. homology screening and expression of fragments, rather than to a thorough understanding and application of amphiphile phase science. So does it help at all to invest resources into the understanding of amphiphile phase behavior (Caffrey, 2003) when tackling the crystallization of a particular membrane protein? Although one would certainly wish so, the truth is that many, if not most successful crystallizations were initially discovered by trial and error, with little or no insight into the phase behavior of the components. One might argue though, that these crystallizations would have been found in a more expedient way, if the phase behavior would have been known ahead of time and properly applied. Likewise, for some of the many membrane proteins that have failed crystallization attempts, insight into the amphiphile phase behavior might have turned these unreported failures into success stories.

What would then constitute a sensible and pragmatic way to efficiently conduct membrane protein crystallization trials? Along the way to overcome the barriers of expression and purification crucial insight into the compatibility with certain detergents and biochemical procedures is often gained. This information is very useful for crystallization trial design. Furthermore, since the co-purified lipids play an important role in crystallization it is advisable to monitor their type and quantities. Micro-analytical techniques such as mass spectrometry (Belrhali et al., 1999; Cohen and Chait, 2001) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (DaCosta and Baenziger, 2003) provide means to monitor and adjust the lipid content. Such characterizations help to assure sample consistency and increase the odds to arrive at reproducible crystallization conditions.

Once compatible detergents are found and samples are available crystallization setups can be set up. At this point even a rudimentary understanding of the phase behavior of the detergent of choice can help to prevent wasting sample. For instance, if the crystallization of partially delipidated PDCs are pursued, crystallization formulation screens may be specifically designed for that particular detergent or detergent/lipid composition (Wiener and Snook, 2001). The crux is that such screens can be developed without the precious membrane protein present, using detergent or detergent/lipid mixes only. Granted, the phase behavior is prone to change once the membrane protein is introduced, however, the fine details of phase transitions necessary for crystallization to occur are then part of the screening procedure carried out with actual crystallization set ups. For instance, slow systematic changes in the environment such as temperature shifts, dehydration over time or dissipating gradients provide means to modulate amphiphile phase behavior in a sensible way.

If the message of the Venn diagram shown in Fig. 7 holds, i.e. some proteins preferentially crystallize in PDCs whereas others rather crystallize in lipidic cubic phase, then it would be beneficial to try different crystallization conditions as well as different crystallization methods. Based on statistical analyses, Segelke et al. (2000) have inferred for soluble proteins that it is of limited value to screen an additional 400 conditions after the first ca. 400 conditions have not yielded any crystal hits. Although the statistics may be different for membrane proteins, switching to a different crystallization methodology after an unsucessful trial may well ‘reset the clock’ and allow to take a fresh start.

Acknowledgments

I greatly appreciate initial discussions with A. Snijder.

References

- Alexandridis P, Olsson U, Lindman B. A record nine different phases (four cubic, two hexagonal, and one lamellar lyotropic liquid crystalline and two micellar solutions) in a ternary isothermal system of an amphiphilic block copolymer and selective solvents (water and oil) Langmuir. 1998;14:2627–2638. [Google Scholar]

- Belrhali H, Nollert P, Royant A, Menzel C, Rosenbusch J, Landau EM, Pebay-Peyroula E. Protein, lipid and water organization in bacteriorhodopsin crystals: a molecular view of the purple membrane at 1.9 angstrom resolution. Structure. 1999;7:909–917. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan SK. β-Barrel proteins in bacterial outer membranes: structure, function and refolding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9:455–461. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(99)80064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey M. Membrane protein crystallization. J Struct Biol. 2003;142:108–132. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(03)00043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartailler J-P, Luecke H. X-ray crystallographic analysis of lipid-protein interactions in the bacteriorhodopsin purple membrane. Ann Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2003;32:285–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.142516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SL, Chait BT. Mass spectrometry as a tool for protein crystallography. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2001;30:67–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.30.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- daCosta CJB, Baenziger JE. A rapid method for assessing lipid: protein and detergent:protein ratios in membrane-protein crystallization. Acta Crystallogr D. 2003;59:77–83. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902019236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornmair K, Kiefer H, Jahnig F. Refolding of an integral membrane protein. OmpA of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:18907–18911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand R, Fambrough DM, Benos DJ. Current Topics in Membranes Lipid Polymorphism and Membrane Properties. Academic Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Essen L-O, Siegert R, Lehmann WD, Oesterhelt D. Lipid patches in membrane protein oligomers: crystal structure of the baacteriorhodopsin–lipid complex. PNAS. 1998;95:11673–11678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faham S, Bowie JU. Bicelle crystallization: a new method for crystallizing membrane proteins yields a monomeric bacteriorhodopsin structure. J Mol Biol. 2002;316:1–6. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme P. Crystallization of Photosystem I. In: Iwata S, editor. Methods and Results in Membrane Protein Crystallization. University Line; La Jolla, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fromme P, Witt HT. Improved isolation and crystallization of photosystem I for structural analysis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1365:175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Garavito RM, Ferguson-Miller S. Detergents as Tools in Membrane Biochemistry. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(35):32403–32406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavito RM, Rosenbusch JP. Three-dimensional crystals of an integral membrane protein: an initial X-ray analysis. J Cell Biol. 1980;86(1):327–329. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.1.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavito RM, Picot D. The art of crystallizing membrane proteins. Method: A Companion to Methods Enzymology. 1990;1:57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Grabe M, Neu J, Oster G, Nollert P. Protein interactions and membrane geometry. Biophys J. 2003;84:854–868. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74904-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruner SM. Intrinsic curvature hypothesis for biomembrane lipid composition: a role for nonbilayer lipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:3665–3669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.11.3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson R, Shotton D. Crystallization of purple membrane in three dimensions. J Mol Biol. 1980;139:99–109. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hino T, Kanamori E, Shen J-R, Kouyama T. An icosahedral assembly of the light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b protein complex from pea chloroplast thylakoid membranes. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60(5):803–809. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904003233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitscherich C, Jr, Aseyev V, Wiencek J, Loll PJ. Effects of PEG on detergent micelles: implications for the crystallization of integral membrane proteins. Acta Crystallogr D. 2001;57:1020–1029. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901006242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunte C, Michel H. Crystallisation of membrane proteins mediated by antibody fragments. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:503–508. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00354-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunte CC, von Jagow G, Schagger H. Membrane Protein Purification and Crystallization: A Practical Guide. Academic Press; San Diego: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata S. In: Methods and Results in Crystallization of Membrane Proteins. Iwata S, editor. International University Line, Biotechnology Series; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata S, Ostermeier C, Ludwig B, Michel H. Structure at 2.8 Å resolution of cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Nature. 1995;376:660–669. doi: 10.1038/376660a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam Z, Shore HB, Feher G. On the Crystallization of Proteins. J Mol Biol. 1978;123:539–555. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90206-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona G, Andreasson U, Landau EM, Andreasson LE, Neutze R. Lipidic cubic phase crystal structure of the photosynthetic reaction centre from Rhodobacter sphaeroides at 2.35 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2003;331(3):681–692. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00751-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe M, Besir H, Essen LO, Oesterhelt D. Structure of the light-driven chloride pump halorhodopsin at 1.8 Å resolution. Science. 2000;288(5470):1390–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau EM, Rosenbusch JP. Lipidic cubic phases: a novel concept for the crystallization of membrane proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14532–14535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux MJ, Reithmeier RAF, Wang D-N. Importance of detergent and phospholipids in the crystallization of the human erythrocyte anion-exchanger membrane domain. J Struct Biol. 2002;137:322–332. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(02)00010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Yan H, Wang K, Kuang T, Zhang J, Gui L, An X, Chang W. Crystal structure of spinach major light-harvesting complex at 2.72 Å resolution. Nature. 2004;428(6980):287–292. doi: 10.1038/nature02373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littrell K, Urban V, Tiede D, Thiyagarajan P. Solution structure of detergent micelles at conditions relevant to membrane protein crystallizations. J Appl Cryst. 2000;33:577–581. [Google Scholar]

- Marheineke K, Gruenewald S, Christie W, Reilaender H. Lipid composition of Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) and Trichoplusia ni (Tn) insect cells used for baculovirus infection. FEBS Lett. 1998;441:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01523-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marone PA, Thiyagarajan P, Wagner AM, Tiede DM. The association state of a detergent-solubilized membrane protein measured during crystal nucleation and growth by small-angle neutron scattering. J Cryst Growth. 1998;191:811–819. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor CL, Chen L, Pomroy NC, Hwang P, Go S, Chakrabatty A, Prive GG. Lipopeptide detergents designed for the structural study of membrane proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(2):171–176. doi: 10.1038/nbt776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura Y, Chernov AA. The morphology and the strength of intermolecular contacts in protein crystals. Acta Crystallogr D. 2003;59:1347–1356. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903011107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel H. General and practical aspects of membrane protein crystallization. In: Michel H, editor. Crystallization of Membrane Proteins. CRC Press Inc.; Boca Raton, FL: 1991. pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Michel H. Crystalization of membrane proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1983;8:56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Michel H, Oesterhelt D. Three-dimensional crystals of membrane proteins: bacteriorhodopsin. PNAS. 1980;77(3):1283–1285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.3.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misquitta Y, Caffrey M. Rational design of lipid molecular structure: a case study involving the C19:1c10 monoacylglycerol. Biophys J. 2001;81:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75762-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nollert P. From test tube to plate: a simple procedure for the rapid preparation of microcrystallization experiments using the cubic phase method. J Appl Cryst. 2002;35:637–640. [Google Scholar]

- Nollert P, Qiu H, Caffrey M, Rosenbusch JP, Landau EM. Molecular mechanism for the crystallization of bacteriorhodopsin in lipidic cubic phases. FEBS Lett. 2001;504:179–186. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02747-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pebay-Peyroula E, Garavito RM, Rosenbusch JP, Zulauf M, Timmins PA. Detergent structure in tetragonal crystals of OmpF porin. Structure. 1995;3(10):1051–1059. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza R, Pierno M, Vignati E, Venturoli G, Francia F, Mallardi A, Palazzo G. Liquid–liquid phase separation of a surfactant-solubilized membrane protein. 2002 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.208101. arXiv:cond-mat/0211505 v1 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pautsch A, Schulz GE. Structure of the outer membrane protein A transmembrane domain. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:1013–1017. doi: 10.1038/2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popot, et al. Amphipols: polymeric surfactants for membrane biology research. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3169-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen . Surfactants and Interfaceial Phenomena. Wiley; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenow MA, Brune D, Allen JP. The influence of detergents and amphiphiles on the solubility of the light-harvesting I complex. Acta Crystallogr D. 2003;59:1422–1428. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903011909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royant A, Nollert P, Edman K, Neutze R, Landau EM, Pebay-Peyroula E, Navarro J. X-ray structure of sensory rhodopsin II at 2.1 Å resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10131–10136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181203898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarsiero BD, Yegian DT, Lee CC, Spraggon G, Gu J, Scheibe D, Uber DC, Cornell EW, Nordmeyer RA, Kolbe WF, Jin J, Jones AL, Jaklevic JM, Schultz PG, Stevens RC. An approach to rapid protein crystallization using nanodroplets. J Appl Cryst. 2002;35:278–281. [Google Scholar]

- Schafmeister CE, Miercke LJW, Stroud RM. Structure at 2.5 Å of a designed peptide that maintains solubility of membrane proteins. Science. 1993;262:734–738. doi: 10.1126/science.8235592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sennoga C, Heron A, Seddon JM, Templer RH, Hankamer B. Membrane-protein crystallization in cubo: temperature-dependent phase behavior of monoolein–detergent mixtures. Acta Crystallogr D. 2003;59:239–246. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902020772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijder HJ, Timmins PA, Kalk KH, Dijkstra BW. Detergent organization in crystals of monomeric outer membrane phospholipase A. J Struct Biol. 2003;141:122–131. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(02)00579-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Sato H, Hino T, Kono M, Fukuda K, Sakurai I, Okada T, Kouyama T. A novel three-dimensional crystal of bacteriorhodopsin obtained by successive fusion of the vesicular assemblies. J Mol Biol. 1998;283(2):463–474. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanford C. The Hydrophobic Effect—Formation of Micelles and Biological Membranes. Wiley Interscience; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Tanford C. The Hydrophobic Effect. Wiley; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Ataka M, Onuma K, Kubota T. Rationalization of membrane protein crystallization with polyethylene glycol using a simple depletion model. Biophys J. 2003;84(5):3299–3306. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70054-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tielemann DP, van der Spoel D, Berendsen HJC. Molecular dynamics simulations of dodecylphosphocholine micelles at three different aggregate sizes: micellar structure and chain relaxation. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:6380–6388. [Google Scholar]

- Tribet C, Audebert R, Popot J-L. Amphipols: Polymers that keep membrane proteins soluble in aqueous solutions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15047–15050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber PC. Advances in Protein Chemistry. 1991:41. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60196-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennerstroem H, Lindman B. Phys Reports. 1979;52:1–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener MC. Existing and emergent roles for surfactants in the three-dimensional crystallization of integral membrane proteins. Curr Opin Coll Int Sci. 2001;6:412–419. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener MC, Snook F. The development of membrane protein crystallization screens based upon detergent solution properties. J Cryst Growth. 2001;232:426–431. [Google Scholar]

- Yu SM, McQuade DT, Quinn MA, Hackenberger CP, Krebs MP, Polans AS, Gellman SH. An improved tripod amphiphile for membrane protein solubilization. Protein Sci. 2000;9(12):2518–2527. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.12.2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Kurisu G, Smith J, Cramer WA. A defined protein–detergent–lipid complex for crystallization of integral membrane proteins: the cytochrome b6f complex of oxygenic photosynthesis. PNAS. 2003;100(9):5160–5163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931431100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulauf M. In: Crystallization of Membrane Proteins. Michel H, editor. CRC Press Inc.; Boca Raton, FL,: 1991. pp. 54–71. [Google Scholar]