Abstract

Background and Aims

Flavonoids have the potential to serve as antioxidants in addition to their function of UV screening in photoprotective mechanisms. However, flavonoids have long been reported to accumulate mostly in epidermal cells and surface organs in response to high sunlight. Therefore, how leaf flavonoids actually carry out their antioxidant functions is still a matter of debate. Here, the distribution of flavonoids with effective antioxidant properties, i.e. the orthodihydroxy B-ring-substituted quercetin and luteolin glycosides, was investigated in the mesophyll of Ligustrum vulgare leaves acclimated to contrasting sunlight irradiance.

Methods

In the first experiment, plants were grown at 20 % (shade) or 100% (sun) natural sunlight. Plants were exposed to 100 % sunlight irradiance in the presence or absence of UV wavelengths, in a second experiment. Fluorescence microspectroscopy and multispectral fluorescence microimaging were used in both cross sections and intact leaf pieces to visualize orthodihydroxy B-ring-substituted flavonoids at inter- and intracellular levels. Identification and quantification of individual hydroxycinnamates and flavonoid glycosides were performed via HPLC-DAD.

Key Results

Quercetin and luteolin derivatives accumulated to a great extent in both the epidermal and mesophyll cells in response to high sunlight. Tissue fluorescence signatures and leaf flavonoid concentrations were strongly related. Monohydroxyflavone glycosides, namely luteolin 4′-O-glucoside and two apigenin 7-O-glycosides were unresponsive to changes in sunlight irradiance. Quercetin and luteolin derivatives accumulated in the vacuoles of mesophyll cells in leaves growing under 100 % natural sunlight in the absence of UV wavelengths.

Conclusions

The above findings lead to the hypothesis that flavonoids play a key role in countering light-induced oxidative stress, and not only in avoiding the penetration of short solar wavelengths in the leaf.

Keywords: Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM), flavonoid glycosides, fluorescence microimaging, fluorescence microspectroscopy, hydroxycinnamates, intra-cellular flavonoid localization, Ligustrum vulgare, photoprotection, UV stress

INTRODUCTION

The idea that flavonoids may counter oxidative damage, in addition to attenuating the highly energetic UV-B wavelengths reaching sensitive targets in a leaf, in response to high solar irradiance, may be inferred from several lines of evidence.

Firstly, it is unlikely that the widely reported UV-B-induced increase in the flavonoid to hydroxycinnamate ratio (Ollson et al., 1999; Burchard et al., 2000; Tattini et al., 2004) depends on their relative abilities to absorb the UV-B wavelengths. Hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives (εmax between 310 and 325 nm) have a greater ability to absorb over the UV-B waveband with respect to most flavonoids (εmax > 330 nm and εmin around 300 nm; Sheahan, 1996; Harborne and Williams, 2000; Tattini et al., 2004).

Secondly, in high light-treated leaves, the biosynthesis of orthodihydroxy B-ring-substituted flavonoids is strongly favoured over that of its monohydroxy B-ring-substituted counterparts (Markham et al., 1998; Ryan et al., 1998; Gould et al., 2000; Tattini et al., 2004, 2005). Nevertheless, the molar extinction coefficient, over the 300–390-nm waveband, of the monohydroxy flavone apigenin 7-O-rutinoside (12·2 mm−1 cm−1) considerably exceeds that of the orthodihydroxy flavonol quercetin 3-O-rutinoside (9·8 mm−1 cm−1; Tattini et al., 2004).

Finally, UV-B radiation is not a pre-requisite for flavonoid biosynthesis (Christie and Jenkins, 1996; Brosché and Strid, 1999; Jenkins et al., 2001; Ibdah et al., 2002). An increase in the concentration of leaf flavonoids was observed in grapevine in response to visible light (Kolb et al., 2001), and the very same flavonoids increased in Lemma gibba in response to both natural sunlight and visible light and excess copper ions (Babu et al., 2003). Bilger et al. (2007) observed an increase in UV-screening compounds in response to low-temperature stress in the absence of UV radiation.

These findings lead to the hypothesis that flavonoids may actually serve a key function to counter UV-induced oxidative stress (Close and McArthur, 2002; Winkel-Shirley, 2002; Tattini et al., 2005), as concluded by Landry et al. (1995): ‘Arabidopsis thaliana responds to UV-B as to an oxidative stress, and sunscreen compounds reduce the oxidative damage caused by UV-B’. Orthodihydroxy B-ring-substituted flavonoids have the potential to effectively inhibit the generation of, as well as to quench, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and structural/antioxidant relationships are well-established (Saskia et al., 1996; Rice-Evans et al., 1997; Brown et al., 1998; Nguyen et al., 2006). It has been suggested previously that metal-chelating and quenching properties, not just the UV-screening features of flavonoids, need to be considered to conclusively explain their roles in land-plant evolution (Swain, 1986; Cooper-Driver and Bhattacharya, 1998; Cockell and Knowland, 1999).

However, it is a matter of fact that flavonoids accumulate mostly in surface organs and epidermal cells because of high-light stress (Schnitzler et al., 1996; Fishback et al., 1997; Tattini et al., 2000, 2007). Yamasaki et al. (1997) proposed that orthodihydroxy B-ring-substituted flavonoids help quench hydrogen peroxide freely diffusing from the mesophyll to enter the vacuoles of the epidermal cells (i.e. serving as substrates for class III peroxidases; Takahama and Oniki, 1997; Pérez et al., 2002). By contrast, few data are available on light-induced accumulation of ‘potentially antioxidant’ flavonoids in chlorophyll-containing tissues, which is a pre-requisite for flavonoids to actually carry out antioxidant functions within the sites of ROS generation (Gould et al., 2002; Kytridis and Manetas, 2006; Agati et al., 2007).

To gain new insights on the complex issue of the multiple functional roles, particularly the antioxidant one, of ‘UV-absorbing’ flavonoids in photoprotection, experiments were performed aimed at visualizing them in ROS-generating cells of leaves exposed to different solar irradiances. For this purpose, ‘new’ techniques of fluorescence microspectroscopy and multispectral fluorescence microimaging were used. Leaves of Ligustrum vulgare, acclimated to (a) 20 % or 100 % natural sunlight and (b) to full sunlight irradiance by cutting or not cutting the UV waveband, were studied. The distribution of hydroxycinnamates and flavonoids was estimated in the leaves paying special emphasis to the mesophyll tissues. Finally, the intracellular distribution of orthodihydroxy B-ring-substituted flavonoids in mesophyll cells was analysed using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) analysis in intact leaves. As far as is known this is the first report on this subject.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material and growth conditions

In the first experiment, Ligustrum vulgare L. plants were grown outside under 20 % (shade) or 100 % natural sunlight (sun) over a 5-week period. Plants at the full-sun site received a daily dose of 12·1 and 1·05 MJ m−2 and 19·4 KJ m−2 in the PAR (photosynthetic active radiation over 400–700 nm), UV-A and UV-B wavebands, respectively. Mean daily doses of 2·4 and 0·19 MJ m−2 and 3·6 KJ m−2 in the PAR, UV-A and UV-B wavebands, respectively, were detected at the shade site.

In the second experiment, L. vulgare plants were grown in greenhouses constructed with the roof and walls made from plastic foil with specific transmittances, over an 8-week experimental period. The greenhouses were north–south exposed, with small shielded openings below the front roof at the north-east and north-west corners to permit air circulation. Solar UV radiation was excluded by LEE 226 UV foils (LEE Filters, Andover, UK) in the PAR100 treatment, whereas in the PAR100 + UV treatment plants were grown under a 100-μm ETFE fluoropolymer film (NOWOFLON® ET-6235; NOWOFLON Kunststoffprodukte GmbH & Co. KG, Siegsdorf, Germany). Control plants were grown under 25 % PAR irradiance (PAR25), which was obtained by adding a proper black polyethylene frame to the LEE 226 UV foil. UV irradiance (280–400 nm) and PAR inside the greenhouses were measured with a SR9910-PC double-monochromator spectroradiometer (Macam Photometric Ltd, Livingstone, UK) and a calibrated Li-190 quantum sensor (Li-Cor Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA), respectively. Total UV irradiance was 24·5 or 1·1 W m−2 in the PAR100 + UV and PAR100 treatments, respectively, at midday on a clear day (PAR was 1450 ± 46 µmol m−2 s−1 at both sites).

Identification and quantification of phenylpropanoids, and analysis of their spectral features

Hydroxycinnamates and flavonoids were extracted, identified and quantified by HPLC-DAD as reported previously in Tattini et al. (2004, 2005). Hydroxycinnamates were p-coumaric acid and echinacoside (a caffeic glycoside ester), and flavonoids were identified as the orthodihydroxy B-ring-substituted quercetin 3-O-rutinoside and luteolin 7-O-glucoside, and the monohydroxy B-ring-substituted luteolin 4′-O-glucoside and apigenin 7-O-glycosides (both glucoside and rutinoside; Tattini et al., 2004). P-coumaric acid was calibrated at 310 nm, echinacoside at 330 nm and flavonoids at 350 nm, using calibration curves of individual compounds operating in the range 0–30 µg. Echinacoside was isolated with semi-preparative HPLC using protocols previously reported in Romani et al. (2000, 2002). The extinction coefficient spectra of 40 µm phenolic solutions (authentic standards purchased from Extrasynthese, Lyon, Nord, Genay, France) with or without the addition of 200 µm of 2-amino ethyl diphenyl boric acid [0·1 %, w/v, Naturstoff reagent (NR)] in phosphate buffer (pH 6·8) with addition of 1 % NaCl (w/v), were recorded using a diode array spectrophotometer (HP8453, Agilent, Les Ulis, France). Fluorescence spectra of 10 µm solutions (in phosphate buffer, pH 6·8) of echinacoside, luteolin 7-O-glucoside and quercetin 3-O-rutinoside with the addition of 50 µm NR were recorded under UV- (λexc = 365 ± 5 nm) and blue-light excitation (λexc = 488 ± 5 nm). A 1 × 1 cm quartz cuvette was horizontally positioned on the sample-holder of a Diaphot epifluorescence microscope (Nikon, Japan) equipped with a high-pressure mercury lamp (HBO 100 W; OSRAM, The Netherlands). Fluorescence spectra were recorded with a CCD multichannel spectral analyser, described in detail in the next section.

Fluorescence microspectroscopy and multispectral fluorescence microimaging

Fluorescence microspectroscopy and multispectral fluorescence microimaging were performed on cross-sections (approx. 100 µm thick) cut from leaves with a vibratory microtome (Vibratome 1100 Plus; St Louis, MO, USA), and stained with NR. The multispectral fluorescence microscope unit has been detailed previously (Tattini et al., 2004; Agati et al., 2007). Fluorescence spectra were recorded using the 365-nm excitation wavelength, which was selected using a 10-nm bandwidth interference filter 365FS10-25 (Andover Corporation, Salem, NH, USA) and an ND 400 Nikon dichroic mirror. Fluorescence spectra (over the 400–800-nm waveband) were measured with a CCD multichannel spectral analyser (PMA 11-C5966; Hamamatsu, Photonics Italia, Arese, Italy) connected to the microscope through an optical fibre bundle, with a ×40 Plan Fluor objective. Fluorescence imaging (on a 404 × 404 µm area) was performed at 580 ± 5 nm using both the 365- and 488-nm excitation wavelengths using a ×10 objective, as described previously (Agati et al., 2007).

CLSM analysis was conducted on a leaf-half infiltrated with approx. 100 µL of NR solution using a plastic syringe without the needle, through a pinhole (made with a 100 µL pipette tip), on the upper leaf end. A leaf piece of approx. 5 × 5 mm, was cut at a distance of 4–5 mm from the pinhole, mounted in the staining buffer, and observed from the adaxial surface. Images were recorded using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems CMS, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with an acusto-optical beam splitter, and an upright microscope stand (DMI6000). A 246 × 246 µm area was imaged using a ×63 objective (HCX PL APO lambda blue 63·0 × 1·40 OIL UV), and image spatial calibration was 0·5 µm pixel−1. The pinhole was set to one ‘Airy unit’. A microscope was used in the sequential scan mode to detect (a) flavonoids: λexc = 488 nm, λem over the 560–600 nm spectral band; and (b) chlorophyll: λexc = 514 nm, λem over the 670–750 nm spectral band. Fluorescence spectra of NR-stained mesophyll cells were recorded (over the 500–640 nm waveband, using the Leica LAS-AF software package) through measurements in the λ-scan mode with a detection window of 10 nm.

RESULTS

Spectral features of hydroxycinnamates and flavonoids, and their tissue-specific localization

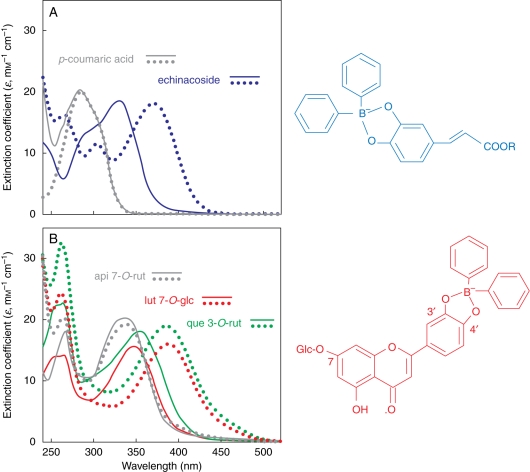

UV spectra of p-coumaric acid and apigenin derivatives, which have a monohydroxy substitution in the benzene ring or in the B-ring of the flavonoid skeleton, respectively, did not undergo a bathochromic shift upon treatment with Naturstoff reagent, in contrast to that observed with the orthodihydroxy structures (Fig. 1A, B). We propose the adduct formation for echinacoside (in blue) and for the orthodihydroxy B-ring-substituted luteolin 7-O-glucoside (in red) upon reaction with NR. It is likely that the same adduct is formed after reaction of quercetin 3-O-rutinoside with the fluorescence enhancer.

Fig. 1.

Extinction coefficient spectra of 40 µm solutions (phosphate buffer, pH 6·8) of hydroxycinnamates (A) and flavonoid glycosides (B) with the addition (continuous lines) or without the addition (dotted lines) of 200 µm 2-amino ethyl diphenyl boric acid (NR). api 7-O-rut, Apigenin 7-O-rutinoside; lut 7-O-glc, luteolin 7-O-glucoside; que 3-O-rut, quercetin 3-O-rutinoside.

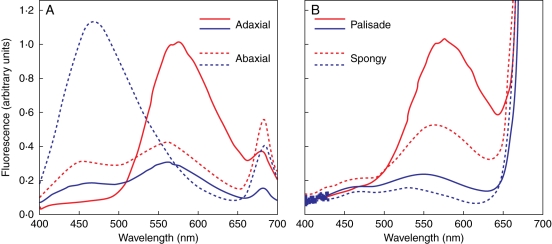

The fluorescence spectra of the mesophyll, not only those of the epidermal tissues, greatly differed between UV-excited cross-sections of L. vulgare leaves acclimated to contrasting sunlight irradiance (Fig. 2). The fluorescence intensity of the adaxial epidermis in sun leaves (λem = 573 nm) was three times greater than the fluorescence intensity in shade leaves (λem = 559 nm; Fig. 2A). Fluorescence spectra of the abaxial epidermises differed mostly for the shape, more than for the intensity, when comparing shade (λem = 470 nm) and sun leaves (λem = 562 nm). The fluorescence intensity of ‘sunny’ mesophyll tissues (both palisade and spongy parenchyma tissues) was more than four times greater than the fluorescence intensity of ‘shade’ mesophyll tissues (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Fluorescence emission spectra of horizontal cross-sections of the epidermis (A) and the mesophyll (B) of Ligustrum vulgare leaves exposed to 20 % (blue lines) or 100 % solar radiation (red lines). Cross-sections (100 µm thick) were stained with 0·1 % (w/v) 2-amino ethyl diphenyl boric acid in phosphate buffer (NR) and excited at 365 ± 5 nm. Spectra have been normalized to fluorescence intensity at 570 nm of adaxial epidermis (A) or palisade tissue (B) of sun leaves, respectively.

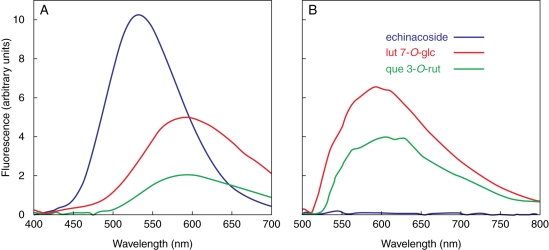

These findings are consistent with the concentration and composition of the ‘soluble’ phenylpropanoid pool detected in shade or sun L. vulgare leaves. Indeed, the concentration of the ‘highly fluorescent’ (NR-treated) orthodihydroxy-substituted compounds (Fig. 3A), i.e. echinacoside (+75 %), and particularly luteolin 7-O-glucoside (+275 %) and quercetin 3-O-rutinoside (+520 %), mostly varied because of high sunlight (Table 1). In contrast, the concentrations of p-coumaric, apigenin 7-O-glycosides and luteolin 4′-O-glucoside, which have negligible fluorescence yields upon staining with NR (Agati et al., 2002), decreased on average by 20 % passing from shade to sun leaves (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Fluorescence spectra of 10 µm solutions (phosphate buffer, pH 6·8) of echinacoside, luteolin 7-O-glucoside (lut 7-O-glc) and quercetin 3-O-rutinoside (que 3-O-rut) with the addition of 50 µm NR under (A) UV- (λexc = 365 ± 5 nm) and (B) blue-light excitation (λexc = 488 ± 5 nm).

Table 1.

The concentration of soluble individual phenylpropanoids in Ligustrum vulgare leaves exposed to 20 % or 100 % natural sunlight irradiance over a 5-week period

| Phenylpropanoid (μmol g−1 d. wt) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Sunlight | p-coumaric | echinacoside | que 3-O-rut | lut 7-O-glc | lut 4′-O-glc | api 7-O-gly |

| 20 | 12·7 ± 1·6 a | 10·8 ± 1·2 b | 2·4 ± 0·2 b | 3·2 ± 0·3 b | 3·9 ± 0·5 | 3·5 ± 0·4 |

| 100 | 9·8 ± 1·5 b | 18·9 ± 2·0 a | 14·9 ± 2·3 a | 12·1 ± 2·1 a | 3·3 ± 0·4 ns | 3·0 ± 0·4 ns |

Data are means ± s.d., n = 6.

Values in a column not accompanied by the same letter are significantly different at P < 0·05 based on a least significant difference (LSD) test. ns, Not significant

Abbreviations: que 3-O-rut, quercetin 3-O-rutinoside; lut 7-O-glc, luteolin 7-O-glucoside; lut 4′-O-glc, luteolin 4′-O-glucoside; api 7-O-gly includes apigenin 7-O-glucoside and apigenin 7-O-rutinoside.

However, note that changes in tissue anatomy and in the tissue-specific content in wall-bound phenolics may contribute considerably to tissue fluorescence signatures under UV-light excitation. Furthermore, the phenolic content varies considerably among different leaf tissues (Fig. 4) and, hence, the whole-leaf phenolic concentration is unlikely to relate to tissue-specific fluorescence signatures.

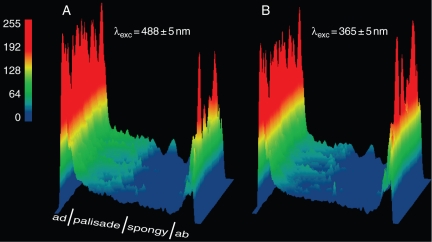

Fig. 4.

Distribution of the fluorescence at 580 nm, F580, as false-colour surface plots, in leaves of Ligustrum vulgare acclimated to full-sunlight irradiance. Cross-sections were stained with NR and excited with (A) far blue- (λexc = 488 ± 5 nm) or (B) UV light (λexc = 365 ± 5 nm).

The mesophyll distribution of UV-responsive phenylpropanoids, i.e. quercetin 3-O-rutinoside, luteolin 7-O-glucoside and echinacoside, was visualized by exciting cross-sections with UV- (λexc = 365 ± 5 nm; Fig. 4B) or blue-light (λexc = 488 ± 5 nm; Fig. 4A), and recording fluorescence at 580 nm (F580). First, note that only orthodihydroxy B-ring-substituted flavonoids have detectable fluorescence yields when treated with the fluorescence enhancer (NR) and excited with far blue-light (Fig. 3B), as previously reported (Sheahan and Rechnitz, 1993; Sheahan et al., 1998). It is assumed that flavonoids are dissolved in the cellular milieu. Indeed, the monohydroxy B-ring-substituted kaempferol 3-O-glucoside (astragalin) is autofluorescent when conjugated to the epidermal cell walls or ‘dissolved’ in lipid bilayers, and quercetin non-covalently bound to proteins emits in the green-yellow waveband under the 488-nm excitation wavelength (Strack et al., 1988; Bondar et al., 1998; Nifli et al., 2007; Tattini et al., 2007).

Flavonoids largely occurred in the adaxial cells of the palisade parenchyma of sun leaves, and their tissue-specific distribution did not markedly differ between UV-excited (λexc = 365 ± 5 nm; Fig. 4B) and blue light-excited cross-sections (λexc = 488 ± 5 nm; Fig. 4A). These data are consistent with a preferential accumulation of quercetin and luteolin derivatives in the adaxial palisade cells, as echinacoside, if present in appreciable amounts, would have enhanced greatly F580 emitted from those cells (fluorescence intensity of echinacoside is greater than that of luteolin 7-O-glucoside and above all of quercetin 3-O-rutinoside, under UV-excitation; Fig. 3A). Changes in the relative intensities of the 365- and 488-nm excitation wavelengths may have partially contributed to slight variations in F580 between UV- and blue light-excited cross-sections (Tattini et al., 2004). Finally, it is noted that fluorescence quenching, as a consequence of re-absorption and dimer annhiliation processes (Ferrer et al., 2003; Rodríguez et al., 2004), which is of increasing significance as tissue flavonoid concentration increases, is more likely to have underestimated, rather than enhanced, light-induced increase in F580.

Distribution of ‘antioxidant’ flavonoids in mesophyll cells

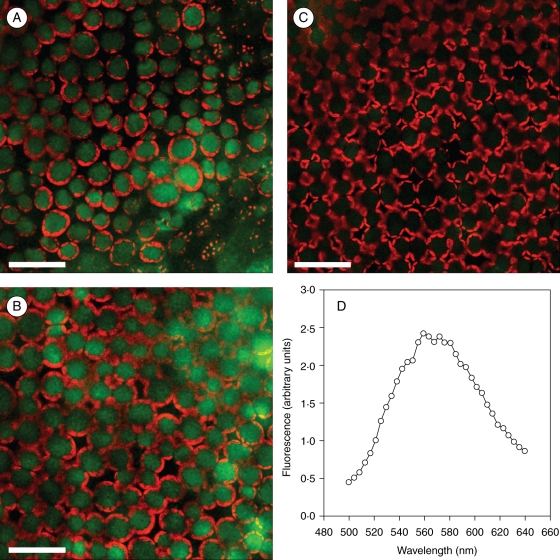

Quercetin and luteolin glycosides did not accumulate in the mesophyll of leaves acclimated to 25 % natural sunlight in the absence of UV wavelengths (PAR25; Fig. 5C). Noticeably, the green-yellow fluorescence due to these orthodihydroxy flavonoids did not vary substantially in intensity when comparing the adaxial palisade cells of leaves exposed to 100 % natural sunlight in presence (PAR100 + UV; Fig. 5A) or absence (PAR100; Fig. 5B) of UV radiation. These findings are consistent with the leaf concentrations of quercetin 3-O-rutinoside and luteolin 7-O-glucoside that increased from 1·1 ± 0·17 µmol g−1 d. wt under PAR25 (means ± s.d., n = 4) to 8·6 ± 0·8 and 11·3 ± 1·9 µmol g−1 d. wt, under PAR100 or PAR100 + UV treatments, respectively. The fluorescence spectrum of blue-light excited (λexc = 488 nm) adaxial palisade cells in PAR100 leaves, which peaked at 565 nm (Fig. 5D), conclusively confirmed the occurrence of these orthodihydroxy B-ring-substituted flavonoids in the cell vacuole (Fig. 5A, B). Chlorophyll-induced attenuation of the excitation wavelength is unlikely to have affected the imaging of flavonoid distribution, as chlorophyll fluorescence did not differ in the adaxial palisade cells of leaves exposed to contrasting sunlight irradiance (Fig. 5A–C).

Fig. 5.

Images of the green and red fluorescence at a depth of 20 µm from the adaxial leaf surface of Ligustrum vulgare growing at different sunlight irradiance: (A) leaves exposed to 100 % natural sunlight over the 300–1100-nm waveband (PAR100 + UV); (B) leaves exposed to 100 % natural sunlight over the 400–1100-nm waveband (PAR100); (C) leaves exposed to 25 % natural sunlight over the 400–1100 nm waveband (PAR25). Measurements were performed on leaf pieces (approx. 25 mm2) infiltrated with 100 µL of NR. CLSM analysis performed in two-channel sequential mode: flavonoid fluorescence was recorded in the green channel (λexc = 488 nm, acquisition in the 560–600-nm band), and the chlorophyll fluorescence in the red channel (λexc = 514 nm, detection in the 670–750-nm band), respectively. (D) In vivo emission spectrum of blue-light excited (λexc = 488 nm) palisade cells of leaves in the PAR100 treatment. Fluorescence signal was integrated, in the λ-scan mode at 10-nm spectral resolution, over a 246 × 246 µm area. Scale bars = 50 µm.

DISCUSSION

In the present experiments, the ‘new’ techniques of fluorescence micro-spectroscopy and multispectral fluorescence microimaging, aimed to visualize leaf flavonoids at inter- and intracellular levels, were used to give new insights on their antioxidant functions in photoprotective mechanisms.

It is shown that antioxidant flavonoids occurred to a great extent in the adaxial (both epidermal and mesophyll) cells of leaves acclimated to high sunlight. This finding, taken together with the preferential distribution of hydroxycinnamates (potentially, the best UV-B screening compounds; Landry et al., 1995; Sheahan, 1996; Harborne and Williams, 2000) in deeper leaf tissues (Fig. 4; Ollson et al., 1999; Tattini et al., 2004), suggest that the functional roles of flavonoids in photoprotective mechanisms, do not depend merely on their UV-absorbing features (Markham et al., 1998; Gould et al., 2000).

Conclusive evidence is offered on the mesophyll distribution of the ‘antioxidant’ quercetin 3-O-rutinoside and luteolin 7-O-glucoside in leaves of L. vulgare exposed to natural sunlight in the presence or absence of UV irradiance. These compounds are vacuolar, which conforms to the findings of Neill et al. (2002) and of Kytridis and Manetas (2006) on the vacuolar compartmentation of ‘flavonoid anthocyanins’ in the mesophyll cells of Elatostema rugosum and Cistus creticus, respectively. It is suggested that mechanical pressure on the tonoplast membrane, using the present infiltration technique, allowed NR to enter the vacuole of mesophyll cells, although the pH gradient across the tonoplast would drive its exclusion from the vacuole (Sheahan et al., 1998). Our fluorescence imaging avoided the generation of artefacts during cross-sectioning (Hutzler et al., 1998), and conclusively localized the flavonoids in ROS-generating cells (Gould et al., 2002; Kytridis and Manetas, 2006). Hence, major criticisms on the localization/functional relationship of flavonoids in photoprotection, which mostly concerns their almost exclusive occurrence in epidermal cells (Yamasaki et al., 1997), have been addressed in the present experiment. With the multispectral fluorescence micro-imaging it was not possible to visualize the distribution of flavonoids in other cellular compartments (e.g. the cytoplasm and the chloroplasts; Sheahan et al., 1998; Agati et al., 2007), probably due to the relatively low resolution of fluorescence imaging.

We hypothesize that flavonoids with a catechol group in the B-ring may quench free radicals and hydrogen peroxide (i.e. serving as substrates for class III peroxidases; Yamasaki et al., 1997; Pérez et al., 2002; Pourcel et al., 2006) in mesophyll cells suffering from severe high-light stress, not only to help scavenge H2O2 freely diffusing from them to enter the vacuole of the epidermal ones. These scavenger activities against H2O2 have been previously reported to be effectively served by orthodihydroxy substituted hydroxycinnamates, like echinacoside (Grace et al., 1998; Tattini et al., 2004). As a consequence, the differential tissue-specific distribution of orthodihydroxy B-ring-substituted flavonoids and echinacoside in high-light exposed leaves may merit a deep comment. Here it is highlighted that the flavonoid skeleton, and not only the presence of the catechol group in the B-ring, confers to flavonoids a greater ability to inhibit the generation of free radicals as compared with other phenylpropanoids. Metal-chelating properties are enhanced by the presence of the C = O group in the C-ring of the flavonoid skeleton, and metal-flavonoid complexes mimic superoxide dismutase activity (Morel et al., 1998; Kostyuk et al., 2004). As a consequence, the overall scavenger activity of ‘antioxidant’ flavonoids may exceed that of ‘antioxidant’ hydroxycinnamates. Also it is not excluded that the light-induced biosynthesis of caffeic derivatives from p-coumaric acid, as observed in the present experiment, may have enhanced lignin biosynthesis, more than increasing the concentration of soluble hydroxycinnamic intermediates in highly irradiated cells. This process may be of key significance in cells suffering from high light-induced oxidative damage, i.e. the adaxial palisade parenchyma cells. In wounded tissues of Arabidopsis thaliana, the unusual substrate used by CYP98A3, a 3′-hydroxylase of phenolic esters, which synthesizes caffeic from p-coumaric acid, was to give priority to the synthesis of flavonoids (Schoch et al., 2001), which further corroborates the idea of an involvement of flavonoids in both preventing and repairing light-induced oxidative damage. Nevertheless, the present experimental data do not allow the issue of tissue-specific accumulation of different phenylpropanoid classes because of high sunlight to be conclusively addressed. This matter has, however, great physiological and biochemical significance, and merits further and in-depth investigation.

The accumulation of mesophyll orthodihydroxy B-ring-substituted flavonoids in leaves acclimated to natural sunlight in the absence of UV radiation, adds further evidence for an important role of flavonoids in countering the oxidative stress generated under excess-light conditions, not only to attenuate the highly energetic UV wavelengths from reaching ROS-generating cells. We hypothesize that UV stress (Gerhardt et al., 2008) does not differ from other stressful agents, of both biotic and abiotic origin (Wojtaszek, 1997; Schoch et al., 2001; Roberts and Paul, 2006; Agati et al., 2007; Lillo et al., 2008), in up-regulating the phenylpropanoid branch pathway leading to the biosynthesis of antioxidant flavonoids.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Stefano Mancuso (Dipartimento di Ortoflorofrutticoltura, Università di Firenze) for his decisive contribution in CLSM analyses, Zoran G. Cerovic (Laboratoire d'Ecologie Systématique et Evolution, CNRS – Université Paris-Sud) for help in extinction coefficient measurements, and D. Grifoni and F. Sabatini (IBIMET-CNR, Italy) for performing spectroradiometric detections. G.S. is supported by a grant from Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze.

LITERATURE CITED

- Agati G, Galardi C, Gravano E, Romani A, Tattini M. Flavonoid distribution in tissues of Phillyrea latifolia as estimated by microspectrofluorometry and multispectral fluorescence microimaging. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2002;76:350–360. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2002)076<0350:fditop>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agati G, Matteini P, Goti A, Tattini M. Chloroplast-located flavonoids can scavenge singlet oxygen. New Phytologist. 2007;174:77–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.01986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu TS, Akhtar TA, Lampi MA, Tripuranthakam S, Dixon DG, Greenberg BM. Similar stress responses are elicited by copper and ultraviolet radiation in the aquatic plant Lemma gibba: implication of reactive oxygen species as common signals. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2003;44:1320–1329. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilger W, Rolland M, Nybakken L. UV screening in higher plants induced by low temperature in the absence of UV-B radiation. Photochemical and Photobiological Sciences. 2007;6:190–195. doi: 10.1039/b609820g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondar OP, Pivovarenko VG, Rowe ES. Flavonols – new fluorescent membrane probes for studying the interdigitation of lipid bilayers. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1998;1369:119–130. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(97)00218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosché M, Strid Ä. Cloning, expression, and molecular characterization of a small pea gene family regulated by low levels of ultraviolet B radiation and other stresses. Plant Physiology. 1999;121:479–487. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.2.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JE, Khodr H, Hider RC, Rice-Evans CA. Structural dependence of flavonoid interactions with Cu2+ ions: implication for their antioxidant properties. Biochemical Journal. 1998;330:1173–1178. doi: 10.1042/bj3301173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchard P, Bilger W, Weissenböck G. Contribution of hydroxycinnamates and flavonoids to epidermal shielding of UV-A and UV-B radiation in developing rye primary leaves as assessed by ultraviolet-induced chlorophyll fluorescence measurements. Plant, Cell & Environment. 2000;23:1373–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Christie JM, Jenkins GI. Distinct UV-B and UV-A/blue light signal transduction pathways induce chalcone synthase gene expression in Arabidopsis cells. The Plant Cell. 1996;8:1555–1567. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.9.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Close DC, McArthur C. Rethinking the role of many plant phenolics – protection from photodamage not herbivores? Oikos. 2002;99:166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Cockell CS, Knowland J. Ultraviolet radiation screening compounds. Biological Reviews. 1999;74:311–345. doi: 10.1017/s0006323199005356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Driver GA, Bhattacharya M. Role of phenolics in plant evolution. Phytochemistry. 1998;49:1165–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer ML, del Monte F, Levy D. Rhodamine 19 fluorescent dimers resulting from dye aggregation on the porous surface of sol-gel silica glasses. Langmuir. 2003;19:2782–2786. [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach RJ, Kossman B, Panten H, et al. Seasonal accumulation of ultraviolet-B screening pigments in needles of Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) Plant, Cell & Environment. 1999;22:27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt KE, Lampi MA, Greenberg BM. The effects of far-red light on plant growth and flavonoid accumulation in Brassica napus in the presence of ultraviolet B radiation. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2008;84:1445–1454. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould KS, Markham KR, Smith RH, Goris JJ. Functional role of anthocyanins in the leaves of Quintinia serrata A. Cunn. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2000;51:1107–1115. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.347.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace SC, Logan BA, Adams WW., III Seasonal differences in foliar content of chlorogenic acid, a phenylpropanoid antioxidant in Mahonia repens. Plant, Cell & Environment. 1998;21:513–521. [Google Scholar]

- Gould KS, McKelvie J, Markham KR. Do anthocyanins function as antioxidants in leaves? Imaging of H2O2 in red and green leaves after mechanical injury. Plant, Cell & Environment. 2002;25:1261–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Harborne JB, Williams CA. Advances in flavonoid research since 1992. Phytochemistry. 2000;55:481–504. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutzler P, Fischbach R, Heller W, et al. Tissue localization of phenolic compounds in plants by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1998;49:953–965. [Google Scholar]

- Ibdah M, Krins A, Seidlitz K, Heller W, Strack D, Vogt T. Spectral dependence of flavonol and betacyanin accumulation in Mesembryanthemum crystallinum under enhanced ultraviolet radiation. Plant, Cell & Environment. 2002;25:1145–1154. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins GI, Long JC, Wade HK, Shenton R, Bibikova TN. UV and blue light signalling: pathways regulating chalcone synthase gene expression in Arabidopsis. New Phytologist. 2001;151:121–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2001.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb CA, Käser MA, Kopecký J, Zotz G, Riederer M, Pfündel EE. Effects of natural intensities of visible and ultraviolet radiation on epidermal ultraviolet screening and photosynthesis in grape leaves. Plant Physiology. 2001;127:863–875. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostyuk VA, Potapovich AI, Strigunova EN, Kostyuk TV, Afanas'ev IB. Experimental evidence that flavonoid metal complexes may act as mimics of superoxide dismutase. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2004;428:204–208. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kytridis V-P, Manetas Y. Mesophyll versus epidermal anthocyanins as potential in vivo antioxidants: evidence linking the putative antioxidant role to the proximity of oxy-radical source. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2006;57:2203–2210. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry LG, Chapple CCS, Last RL. Arabidopsis mutants lacking phenolic sunscreens exhibit enhanced ultraviolet-B injury and oxidative damage. Plant Physiology. 1995;109:1159–1166. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.4.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillo C, Lea US, Ruoff P. Nutrient depletion as a key factor for manipulating gene expression and product formation in different branches of the flavonoid pathway. Plant, Cell & Environment. 2008;31:587–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham KR, Ryan KG, Bloor SJ, Mitchell KA. An increase in luteolin : apigenin ratio in Marchantia polymorpha on UV-B enhancement. Phytochemistry. 1998;48:791–794. [Google Scholar]

- Morel I, Cillard P, Cillard J. Flavonoid-metal interactions in biological systems. In: Rice-Evans C, Packer L, editors. Flavonoids in health and diseases. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1998. pp. 163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Neill SG, Gould KS, Kilmartin PA, Mitchell KA, Markham KR. Antioxidant activity of red versus green leaves in Elatostema rugosum. Plant, Cell & Environment. 2002;25:539–547. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen MT, Awale S, Tezuka Y, Ueda J-Y, Tran Q, Kadota S. Xanthine oxidase inhibitors from the flowers of Chrysanthemum sinense. Planta Medica. 2006;72:46–51. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-873181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nifli A-P, Theodoropoulos PA, Munier S, et al. Quercetin exhibits a specific fluorescence in cellular milieu: a valuable tool for the study of its intracellular distribution. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2007;55:2873–2878. doi: 10.1021/jf0632637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollson LC, Veit M, Bornman JF. Epidermal transmittance and phenolic composition of atrazine-tolerant and atrazine-sensitive cultivars of Brassica napus grown under enhanced UV-B radiation. Physiologia Plantarum. 1999;107:259–266. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez FJ, Villegas D, Mejia N. Ascorbic acid and flavonoid-peroxidase reaction as a detoxifying system of H2O2 in grapevine leaves. Phytochemistry. 2002;60:573–580. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourcel L, Routaboul J-M, Cheynier V, Lepiniec L, Debeaujon I. Flavonoid oxidation in plants: from biochemical properties to physiological functions. Trends in Plant Science. 2006;12:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice-Evans CA, Miller NJ, Papanga G. Antioxidant properties of phenolics compounds. Trends in Plant Science. 1997;2:152–159. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts MR, Paul ND. Seduced by the dark side: integrating molecular and ecological perspectives on the influence of light on plant defence against pests and pathogen. New Phytologist. 2006;170:677–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez HB, Lagorio MG, San Román E. Rose Bengal adsorbed on microgranular cellulose: evidence on fluorescent dimmers. Photochemical and Photobiological Science. 2004;1:581–587. doi: 10.1039/b402484b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani A, Pinelli P, Mulinacci N, Vincieri FF, Gravano E, Tattini M. HPLC analysis of flavonoids and secoiridoids in leaves of Ligustrum sinensis L. (Oleaceae) Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2000;48:4091–4096. doi: 10.1021/jf9913256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani A, Pinelli, Galardi C, Mulinacci N, Tattini M. Identification and quantification of galloyl derivatives, flavonoid glycosides and anthocyanins in leaves of Pistacia lentiscus. Phytochemical Analysis. 2002;13:79–86. doi: 10.1002/pca.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan KG, Markham KR, Bloor SJ, Bradley JM, Mitchell KA, Jordan BR. UV-B radiation induces increase in quercetin : kaempferol ratio in wild-type and transgenic lines of Petunia. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 1998;68:323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Saskia AB, van Acker E, van den Bergh D-J, et al. Structural aspects of antioxidant activity of flavonoids. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1996;20:331–342. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler J-P, Jungblut TP, Heller W, et al. Tissue localization of UV-B screening pigments and of chalcone synthase nRNA in needles of Scots pine seedlings. New Phytologist. 1996;132:247–258. [Google Scholar]

- Schoch G, Goepfert S, Morant M, et al. CYP98A3 from Arabidopsis thaliana is a 3′-hydroxylase of phenolic esters, a missing link in the phenylpropanoid pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:36566–36574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104047200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheahan JJ. Sinapate esters provide greater UV-B attenuation than flavonoids in Arabidopsis thaliana (Brassicaceae) American Journal of Botany. 1996;83:679–686. [Google Scholar]

- Sheahan JJ, Rechnitz GA. Differential visualization of transparent testa mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana. Analytical Chemistry. 1993;65:961–963. [Google Scholar]

- Sheahan JJ, Cheong H, Rechnitz GA. The colorless flavonoids of Arabidopsis thaliana (Brassicaceae). I. A model system to study the orthodihydroxy structure. American Journal of Botany. 1998;85:467–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack D, Heilemann J, Momken M, Wray V. Cell-wall conjugated phenolics from coniferae leaves. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:3517–3521. [Google Scholar]

- Swain T. Plant flavonoids in biology and medicine. In: Cody V, Middleton E Jr, Harborne JB, editors. Progress in clinical and biological research. New York, NY: Liss; 1986. pp. 1–14. 213. [Google Scholar]

- Takahama U, Oniki T. A peroxidase/phenolics/ascorbate system can scavenge hydrogen peroxide in plant cells. Physiologia Plantarum. 1997;101:845–852. [Google Scholar]

- Tattini M, Gravano E, Pinelli P, Mulinacci N, Romani A. Flavonoids accumulate in leaves and glandular trichomes of Phillyrea latifolia exposed to excess solar radiation. New Phytologist. 2000;148:69–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tattini M, Galardi C, Pinelli P, Massai R, Remorini D, Agati G. Differential accumulation of flavonoids and hydroxycinnamates in leaves of Ligustrum vulgare under excess light and drought stress. New Phytologist. 2004;163:547–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tattini M, Guidi L, Morassi-Bonzi L, et al. On the role of flavonoids in the integrated mechanisms of response of Ligustrum vulgare and Phillyrea latifolia to high solar radiation. New Phytologist. 2005;167:457–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tattini M, Matteini P, Saracini E, Traversi ML, Giordano C, Agati G. Morphology and biochemistry of non-glandular trichomes in Cistus salvifolius L. leaves growing in extreme habitats of the Mediterranean basin. Plant Biology. 2007;9:411–419. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkel-Shirley B. Biosynthesis of flavonoids and effect of stress. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2002;5:218–223. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(02)00256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtaszek P. Oxidative burst: an early response to pathogen infection. Biochemical Journal. 1997;322:681–692. doi: 10.1042/bj3220681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki H, Sakihama Y, Ikehara N. Flavonoid-peroxidase reaction as a detoxification mechanism of plant cells against H2O2. Plant Physiology. 1997;115:1405–1412. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.4.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]