Abstract

IL-4 and IL-13 are instrumental in the development and progression of allergy and atopic disease. Basophils represent a key source of these cytokines and produce IL-4 and IL-13 when stimulated with IL-18, a member of the IL-1 family of cytokines. Comparative analyses of the effects of caspase-1-dependent IL-1 family cytokines on basophil IL-4 and IL-13 production have not been performed, and the signaling pathway proteins required for FcεRI-independent Th2 cytokine production from basophils remain incompletely defined. Using mouse bone marrow-derived cultured basophils, we found that IL-4 and IL-13 are produced in response to IL-18 or IL-33 stimulation. IL-18- or IL-33-mediated Th2 cytokine production is dependent on MyD88 and p38α signaling proteins. In addition, basophil survival increased in the presence of IL-18 or IL-33 as a result of increased Akt activation. Studies in vivo confirmed the potency of IL-18 and IL-33 in activating cytokine release from mouse basophils.

Keywords: IL-4, IL-1, signaling

Introduction

IL-1 family cytokines play established roles in inflammatory, infectious, and autoimmune diseases [1]. Some members of this cytokine family (IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-33) are produced as precursor proteins and require caspase-1-mediated cleavage to produce mature, secreted proteins. IL-1α and IL-1β are produced by a variety of cells including macrophages, lymphocytes, epithelial cells, and endothelial cells [2]. IL-18 is secreted by macrophages and Kupffer cells, and IL-33 mRNA expression is constitutively expressed in airway epithelial cells and in bronchial, coronary, and pulmonary artery smooth muscles [3, 4].

Recently, caspase-1-dependent IL-1 family cytokines have been implicated in the development of Th2 responses and atopic diseases [5, 6]. Injection of IL-18 into mice increases basophil IL-4 production and enhances antigen-induced eosinophil recruitment, serum IgE, and Th2 cytokine levels in the lung [7,8,9]. In vitro, IL-18 increases the production of IL-4 and IL-13 by basophils and mast cells [9, 10]. Treatment of mice with rIL-33 causes blood eosinophilia and splenomegaly and increases serum levels of IgE, IgA, IL-5, and IL-13. Exposure to IL-33 also results in severe pathological changes in the gastrointestinal tract and lungs, including eosinophilic and mononuclear infiltrates, increased mucus production, and epithelial cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy [3]. In human subjects, IL-18 and IL-1β concentrations increase significantly during pollen season compared with baseline, and increased serum concentrations of soluble ST2, a component of the IL-33R, have been reported in patients with asthma and allergic airways inflammation [11,12,13].

IL-4 and IL-13 play pivotal roles in the induction of allergy and asthma. Basophils can produce both cytokines after FcεRI cross-linking. However, the stimuli and pathways that elicit an FcεRI-independent IL-4/IL-13 response from basophils are incompletely defined. It has been reported that IL-18 induces bone marrow-derived basophils and mast cells to produce IL-4 and IL-13 independent of FcεRI cross-linking [10]. Similarly, IL-33 causes mast cells to produce IL-13 in an FcεRI-independent manner [14]. Careful studies in basophils remain difficult because of the rarity of basophils in vivo, as these cells represent fewer than 0.5% of blood leukocytes [15]. Here, we used purified mouse bone marrow-derived basophils to conduct in vitro analyses comparing the effects of IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-33 on cytokine production and cell signaling networks. Our studies conclude that IL-18 and IL-33 use a MyD88- and p38α-dependent pathway to elicit IL-4 and IL-13 from basophils.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cytokines and antibodies

mIL-3 and SCF were purchased from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA, USA). mIL-1β was purchased from Fitzgerald Industries (Concord, MA, USA). mIL-18 and mIL-33 were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Antibodies to p38α MAPK, p38β MAPK, phospho-Akt, phospho-c-Jun, GAPDH, phospho-IκB-α, phospho-IRAK1, phospho-SAPK/JNK, phospho-NF-κB, phospho-p38 MAPK, phospho-p38 MAPK (28B10), phospho-STAT3, TAB1, and phospho-TAK1 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Antibodies to protein kinase B, Akt, ERK, phospho-ERK, JNK/SAPK1, STAT3, and phosphotyrosine-RC20:biotin were purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY, USA). Antibodies to caspase 1/IL-1β-converting enzyme, IRAK, IRAK4, phospho-STAT6, phospho-Syk, and TRAF6 were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). Antiphosphoserine was purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA, USA), and antiphosphoserine/threonine was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Antibodies to Fyn, Zap70, and Syk were gifts from the Arthur Weiss lab at UCSF (CA, USA). Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG, goat anti-mIgG, and goat-anti-mIgG light chain-specific were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA, USA). Chemical inhibitors included PD98059 (BioSource, Camarillo, CA, USA; #PHZ1164), SB239063 (Axxora, San Diego, CA, USA; #ALX-270-351), Wortmannin PI3K inhibitor (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA; #681675), NF-κB SN50 inhibitor peptide (Calbiochem; #481480), and JNK inhibitor (Calbiochem; #420116) and were reconstituted according to manufacturers’ instructions.

Mice

C57BL/6 female mice and BALB/c female mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). MyD88−/− mice have been described [16]. Mice were housed in the pathogen-free animal facility at UCSF according to institutional guidelines.

Bone marrow-derived basophil and mast cell growth and purification

Bone marrow was harvested from the femurs and tibiae of 8- to 12-week-old mice and cultured at a density of 1 million cells/mL in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin and streptomycin, and 2 mM glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Depending on experimental needs, bone marrow from each mouse was cultured separately, or bone marrow from up to nine mice was pooled and grown as a single culture. IL-3 (10 ng/mL) was added on Days 0, 3, and 6 to promote basophil differentiation. On Day 9 or Day 10 of culture, the cells were washed with PBS and then incubated for 5 min with anti-CD16/CD32. The cells were then stained with PE-anti-CD49b (DX5), APC-anti-c-kit, and DAPI. Cells were sorted using a MoFlo® high-speed cell sorter (DakoCytomation, Denmark) to obtain pure basophils (DX5+/c-kit–/DAPI–). Subsequent analysis of sorted basophils by flow cytometry was carried out by staining cells with biotinylated-anti-FcεRI, anti-Siglec-F (rat IgG2a isotype), and the following antibodies conjugated to PerCP/Cy5.5: anti-NK1.1, anti-CD3ε, anti-CD19, and anti-CD4. Anti-Siglec-F was stained in a second step with biotinylated anti-rat IgG2a. Samples stained with biotinylated antibodies were subsequently stained with streptavidin-PerCP/Cy5.5. Cells were analyzed on a LSRII instrument (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA, USA), and data were analyzed using FlowJo® software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

To obtain mast cells, cultures were grown as described above until Day 10, at which point, SCF (20 ng/mL) was added. Cultures were refreshed every 7 days with new media, IL-3 (10 ng/mL), and SCF (20 ng/mL). After 5 weeks, >97% of the cells were mast cells, as determined by cell-surface staining (c-kit+FcεRI+CD131+DX5–; Supplemental Fig. 1).

Flow cytometry

Bone marrow-derived basophils and mast cells were washed with PBS and then incubated for 5 min with anti-CD16/CD32 prior to staining. Antibody staining was carried out in non-azide buffer (PBS, 2% FCS) for sorting and in azide-containing buffer (PBS, 2% FCS, 1 mg/ml sodium azide) for flow analysis using 1:100 antibody concentrations. Cells were stained for 30 min at 4°C in the dark and then washed with buffer. In the case of multistep staining, subsequent stainings were performed under the same conditions. The cells were then resuspended in buffer containing DAPI (100 μg/mL). Sorting was carried out using a MoFlo® cell sorter (DakoCytomation), and flow analysis was conducted using a LSRII instrument (BD Immunocytometry Systems). Cell analysis was carried out using the following BD PharMingen antibodies: PE-anti-DX5, APC-anti-c-kit, PE-anti-CD131, PE-anti-Siglec-F, anti-CD4, anti-NK1.1, anti-CD3ε, and anti-CD19, which were conjugated to PerCP/Cy5.5. Biotin-conjugated FcεRI was purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). Biotinylated anti-rat IgG and APC750-anti-CD4 were purchased from Caltag (South San Francisco, CA, USA). Streptavidin-APC was purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti-human CD2-PE and mIgG2a-PE isotype control were purchased from Invitrogen.

RNA isolation and analysis

RNA was isolated from lung cells or from 2 × 106 bone marrow-derived basophils (grown from the bone marrow of a single mouse) or bone marrow-derived mast cells using a Qiagen RNeasy kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (including the DNase digestion step). To generate cDNA, 1 μg RNA was reverse-transcribed using a Superscript III RT kit (Invitrogen) with oligo dT primers. The total reaction volume was 20 μL. For PCR analysis, 2 μL of the RT reactions was analyzed using the following conditions: The first cycle of 10 min at 94°C was followed by 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C for 25 cycles (except β-actin, which was run for 22 cycles). The conditions were chosen so that RNAs were analyzed in the exponential phase of amplification. PCR primers were purchased from Elim Biopharmaceuticals (Hayward, CA, USA), and primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 1. An equal volume of each reaction was loaded onto a 1% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and visualized under UV light. Signals were analyzed by densitometry. Band intensities for cytokine receptor RNA were normalized to β-actin. Band intensities for IL-4 mRNA were normalized to β-actin and then calculated relative to the IL-3-alone cytokine condition.

Cytokine stimulation

Sorted basophils or mast cells cultured for 5 weeks were aliquoted into 48-well plates at a concentration of 1 million cells/mL and allowed to rest in complete RPMI for 2 h at 37°C. The cytokines IL-3 (10 ng/mL), IL-18 (20 ng/mL), IL-33 (10 ng/mL), and IL-1β (10 ng/mL) were added as indicated. Ionomycin was added at a concentration of 1 μm for basophils and mast cells where indicated. PMA was added to mast cells at a concentration of 0.1 μg/mL. For samples stimulated for 24 h, anti-IL-4Rα1 (5 μg/mL) was added to block IL-4 and IL-13 binding, and samples were restimulated with cytokines after 12 h. For inhibition studies, chemical inhibitors [PD98059 (2 μM), SB239063 (500 nM), wortmannin PI3K inhibitor (1, 10, and 50 μM), NF-κB SN50 inhibitor peptide (50 μM), and JNK inhibitor (1 μM)] were added 1 h prior to cytokine addition. Experiments were performed in triplicate. For ELISA assays, cytokine incubations were carried out for 24 h, at which time, the supernatants were collected for analysis. For Western blot analysis, cytokine stimulation was carried out for 15 min or 24 h. The cells were then washed twice with ice-cold PBS. Whole cell lysate samples were prepared using 30–50 μl PhosphoSafe™ extraction reagent (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA). Lysates were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels immediately.

Western blot analysis

Whole cell lysates and immunoprecipitated protein samples were heated for 10 min at 90°C and then loaded onto 4–20% SDS-PAGE gels (Invitrogen). Gels were run at 150 V for 1 h 45 min. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using a Bio-Rad transfer cell, running at 30 V overnight at 4°C. Membranes were then rinsed briefly in 1× TBS-Tween-20 and then used for Western blotting.

Protein transfer blots were blocked in 5% BSA in 1× TBS-Tween 20 for 1 h. Fresh blocking solution containing primary antibody (at the manufacturer’s recommended antibody dilution) was then added, and the blots were rocked gently overnight at 4°C. The blots were washed three times with 1× TBS-Tween 20. Biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit IgG, goat anti-mIgG, goat-anti-mIgG light chain-specific) were added at the manufacturer’s recommended dilution and incubated by rocking gently at room temperature for 1 h. ECL Plus was used for detection. Bands were visualized using film (Kodak BioMax light autoradiography film) and a Kodak Image Station 440.

Cytokine ELISA

IL-4, IL-13, and IL-1β in basophil culture supernatants were determined by ELISA. To detect IL-4, anti-mIL-4 (clone 11B11, BD PharMingen) was used as a capture antibody, and biotinylated anti-mIL-4 (clone BVD6-24G2, BD PharMingen) was used as the detection antibody. rmIL-4 was used as a standard. For IL-13 quantification, anti-mIL-13 (clone 38213.11, R&D Systems) was used as a capture antibody, and biotinylated anti-mIL-13 (#BAF413, R&D Systems) was used as the detection antibody. rmIL-13 was used as a standard. IL-1β (clone B122, eBioscience) was used as a capture antibody, and biotinylated anti-mIL-1β (#13-7112, eBioscience) was used as the detection antibody and rmIL-1β as a standard. Streptavidin-HRP was added, and the plates were developed by the addition of 4-nitrophenyl phosphate as a substrate and measured using a Spectra Max 340 PC instrument (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The lower detection limit for rmIL-4 and rmIL-1β was 15 pg/mL. The lower detection limit for rmIL-13 was 32.5 pg/mL.

Lung cell harvest

Whole lungs were harvested from mice, minced, and dispersed through a 70-μm filter to create single-cell suspensions. Erythrocytes were lysed in RBC lysis buffer [KHCO3 (10 mM), NH4Cl (150 mM), EDTA (pH 8.0; 0.1 mM)]. Cells were washed in PBS and then used to prepare RNA.

Basophil viability

Viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h after sorting by flow cytometry.

Analysis of basophil activation in vivo

IL-4 dual reporter mice, designated 4 get x KN2, have been described previously [9]. Cells from these mice spontaneously mark IL-4-competent cells by expressing GFP and recent IL-4 secretion by expressing surface human CD2. Mice were infected s.c. with 500 third-stage larvae of Nippostrongylus brasiliensis to raise spleen basophil numbers as described [17]. On Day 7 after infection, mice were injected i.v. with IL-3 (1 μg) in combination with IL-1β, IL-18, or IL-33 (1 μg). After 4 h, the spleens were harvested and processed for FACS analysis. Basophils were gated as GFP+, CD4–, DX5+, side-scatter-lo, as described [17] and analyzed for human CD2 surface expression as a measure of IL-4 cytokine secretion.

Statistical analysis

P values were calculated using independent, two-tailed Student’s t-tests.

RESULTS

Generation of bone marrow-derived basophils

Culturing dispersed murine bone marrow-derived cells in IL-3 generates a large population of basophils within 9–10 days, and a majority of the remaining cells develops into mast cells (Supplemental Fig. 2A). From these cultures, basophils (which express DX5 but not c-kit) can be readily distinguished and purified from mast cells (which express c-kit but not DX5) using flow cytometry. For these studies, basophils (DX5+c-kit-) were sorted from bone marrow-derived cultures on Day 9 or Day 10 of culture to yield a 98–99% pure population of basophils (Supplemental Fig. 2B). Analysis of sorted basophils confirmed that these cells are FcεRI+ and negative for eosinophil, NK cell, NK T cell, CD4 T cell, and B cell surface markers (Supplemental Fig. 2C).

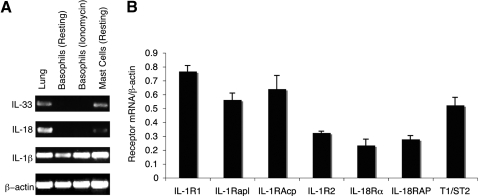

Basophil IL-1 family cytokine and cytokine receptor expression profile

Murine bone marrow-derived basophils express IL-1β mRNA but not mRNA transcripts for IL-18 or IL-33 cytokines, even after ionomycin stimulation (Fig. 1A). Similar findings have been reported in human basophils, which express IL-1β but not IL-18 mRNA [18]. Transcripts for IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-33 were detected in mouse whole lung tissue and in mast cells (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

IL-1 family receptor and cytokine mRNA expression in basophils. (A) RT-PCR detection of cytokine gene expression in mouse whole lung tissue, purified resting basophils, purified ionomycin (1 μm)-stimulated basophils, and mast cells. (B) RNA was isolated from bone marrow-derived basophils, and receptor mRNA levels were analyzed along with β-actin as a housekeeping gene by semiquantitative PCR. Results are the mean of three experiments ± sem.

Microarray and cell-surface expression studies have reported that basophils express receptors for IL-1, IL-18, and IL-33 [10, 18,19,20]. Semiquantitative PCR analysis of mRNA from bone marrow-derived basophils showed that transcripts for IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-33 receptors and receptor-associated proteins are expressed (Fig. 1B). Thus, we sought to compare the effects of IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-33 on IL-4 and IL-13 cytokine production in basophils.

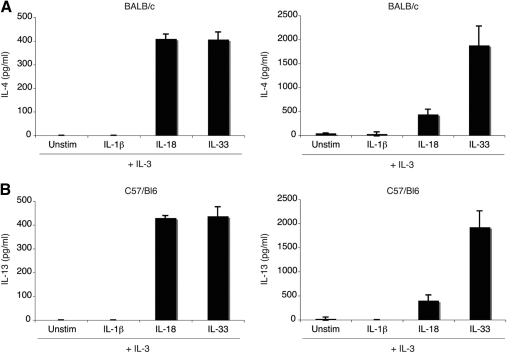

IL-18 and IL-33 induce IL-4 and IL-13 production from basophils

To evaluate the effects of IL-1 family cytokines on Th2 cytokine production in basophils, purified bone marrow-derived basophils were incubated for 24 h in media containing IL-3 (10 ng/mL), alone or in combination with IL-1β (10 ng/mL), IL-18 (20 ng/mL), or IL-33 (10 ng/mL), with the cytokine concentrations optimized in preliminary experiments (data not shown). IL-3 was added to all of the conditions, as basophils survive poorly without this cytokine. As shown previously, IL-18 was a potent stimulus for IL-4 and IL-13 release, although the combination of IL-3 with IL-33 was even more potent at releasing IL-13 under these conditions (Fig. 2, A and B) [10]. The amount of IL-4 produced after stimulation with IL-18 or IL-33 is roughly equivalent (∼400 pg/mL). However, IL-13 production is fourfold higher in the presence of IL-33 as opposed to IL-18. Results are comparable using basophils from C57BL/6 or BALB/c mice. Combining two or more IL-1 family cytokines did not affect the amounts of IL-4 or IL-13 produced (data not shown).

Figure 2.

IL-4 and IL-13 production from bone marrow-derived basophils. Basophils from BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice, were stimulated with IL-3 (10 ng/mL) alone or in combination with IL-1β (10 ng/mL), IL-18 (20 ng/mL), or IL-33 (10 ng/mL) for 24 h. Supernatants were harvested and analyzed by ELISA to quantify IL-4 (A) and IL-13 (B). Results are the mean of three experiments ± sem.

As basophils do not express IL-18 or IL-33 mRNA, the production of IL-4 and IL-13 is unlikely to reflect autocrine amplification of expression. Furthermore, although basophils are competent for IL-1β production, ELISA analysis demonstrated that no IL-1β protein could be detected from basophils, while resting or after incubation in IL-18 or IL-33.

Helminth infection results in basophil accumulation in the spleen that allowed us to assess the relative efficacy of these IL-1 family members in eliciting cytokine release from basophils in vivo. Dual IL-4 reporter, 4 get x KN2, mice were used after infection with N. brasiliensis to assess IL-4 expression in vivo without the need for restimluation, as described previously [9]. Cytokines were injected at Day 7, when basophils increase in the spleen, and the splenic basophils were analyzed for IL-4 secretion by human CD2 expression 4 h later. In agreement with the in vitro data, IL-18 and IL-33 were more potent than IL-1β in inducing cytokine secretion from mouse basophils in vivo (Supplemental Fig. 3).

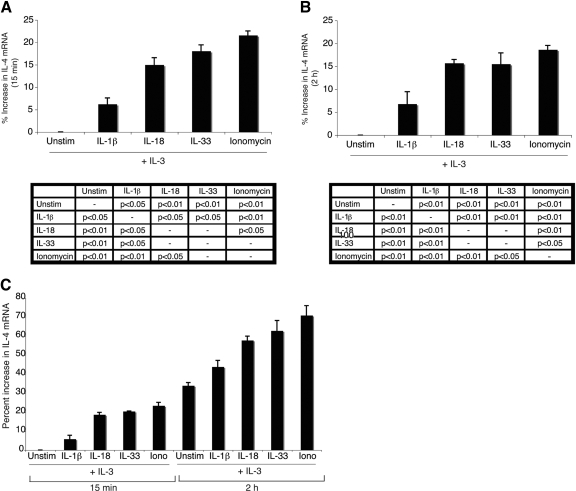

IL-4 mRNA transcription in basophils is increased with IL-1β, IL-18, or IL-33 stimulation

IL-4 mRNA is constitutively expressed in basophils [21]. To determine whether these IL-1 family cytokines promote additional IL-4 mRNA transcription, semiquantitative PCR was used. RNA was harvested from basophils that had been cultured in IL-3 alone or in combination with IL-1β, IL-18, IL-33, or ionomycin. Cells were analyzed after 15 min and 2 h of cytokine stimulation (Fig. 3, A and B, respectively). Ionomycin-treated cells represent the maximum level of IL-4 transcription in basophils, and cells incubated in IL-3 alone (unstimulated) represent the basal level of IL-4 mRNA transcription, which increases over time with incubation in IL-3 alone, with an ∼33% increase in IL-4 mRNA at the 2-h time-point as compared with the 15-min time-point (Fig. 3C). At 15 min and 2 h, all three IL-1 family cytokines up-regulate IL-4 mRNA transcription over levels induced by IL-3 alone. However, this increase is greater for cells stimulated with IL-18 and IL-33 (∼15% increase as compared with IL-3 alone) than those incubated with IL-1β (∼7% increase as compared with IL-3 alone).

Figure 3.

IL-4 mRNA expression in cytokine-stimulated basophils. Basophils were stimulated with IL-3 (10 ng/mL) alone or in combination with IL-1β (10 ng/mL), IL-18 (20 ng/mL), IL-33 (10 ng/mL), or ionomycin (1 μm) for 15 min (A and C) or 2 h (B and C). IL-4 mRNA levels were analyzed along with β-actin as a housekeeping gene by semiquantitative PCR. IL-4 mRNA levels were normalized to β-actin and graphed as the percent increase relative to IL-3-only stimulation at 15 min (A and C) or IL-3-only stimulation at 2 h (B). A representative gel is shown in Supplemental Figure 4. Results are the mean of three experiments ± sem. Statistical significance data are reported for each time-point below the respective graph.

Although IL-1β induces an increase in IL-4 mRNA transcription, albeit to a lower extent than IL-18 or IL-33, it does not lead to the detectable secretion of IL-4 or IL-13. To determine the molecular basis for this distinction, we analyzed the status of signaling proteins in basophils after treatment with the IL-1 family cytokines.

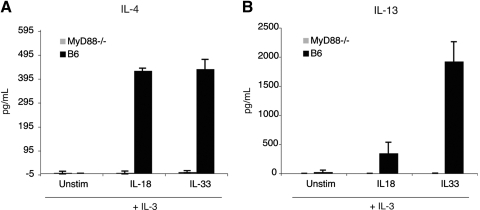

MyD88 is essential for IL-4 and IL-13 production

TLR/IL-1 signaling proteins engaged after the activation of the receptors for IL-1, IL-18, and IL-33 include MyD88, IRAK4, IRAK1, TRAF6, TAB1, TAK1, and NF-κB as part of a canonical pathway. It was unexpected that IL-18 and IL-33 promoted the release of IL-4 and IL-13 from basophils, and IL-1β did not. To examine whether MyD88 was necessary for IL-4 secretion, purified bone marrow-derived basophils from MyD88−/− mice were incubated in IL-3 alone or in combination with IL-18, IL-33, or ionomycin. In contrast to wild-type basophils, neither IL-18 nor IL-33 elicited IL-4 or IL-13 cytokine production from MyD88−/− basophils (Fig. 4, A and B). However, MyD88−/− as well as wild-type basophils produced ∼2.2 ng/mL IL-4 and ∼2.5 ng/mL IL-13 after stimulation with 1 μm ionomycin (data not shown). These results suggest that MyD88 is required at a post-transcriptional stage for IL-4 and IL-13 production. However, it is also possible that the absence of MyD88 affects cellular processes, which may indirectly impede the release of IL-4 and IL-13 from basophils.

Figure 4.

MyD88 is required for IL-4 and IL-13 production. Wild-type C57BL/6 or MyD88−/− basophils were stimulated with IL-3 (10 ng/mL), alone or in combination with IL-18 (20 ng/mL) or IL-33 (10 ng/mL). IL-4 production (A) and IL-13 production (B) were determined by ELISA. Results are the mean of three experiments ± sem.

Canonical IL-1R signaling proteins are not phosphorylated

The signaling proteins IRAK1, TRAF6, and TAB1 are each present in basophils, as revealed by immmunoblotting (Supplemental Fig. 5A). These proteins were also detected in bone marrow-derived mast cells, which were used as a positive control (Supplemental Fig. 5B). However, immunoblotting with antibodies against phosphorylated IRAK1, phosphorylated TAK1, and activated NF-κB revealed that none of these proteins were activated in IL-1β-, IL-18-, or IL-33-stimulated basophils (Supplemental Fig. 5C). A minor amount of phosphorylated TAK1 was noted in basophils incubated in IL-3 only, which indicates that this pathway has the potential for activation in murine basophils. In contrast, mast cells stimulated with IL-33 or PMA/ionomycin show phosphorylation of IRAK1, TAK1, and NF-κB (Supplemental Fig. 5, C and D), suggesting that this pathway is active in mast cells but not in basophils. IL-33-mediated phosphorylation of NF-κB in mast cells is consistent with reported data [3].

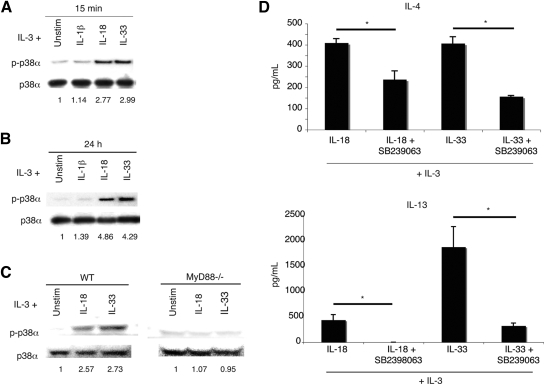

p38α is used by IL-18 and IL-33 to induce IL-4 and IL-13 production from basophils

To gain an understanding of downstream signaling events, we examined phosphorylation of MAPK proteins. To identify signaling proteins activated by IL-18 and IL-33, basophils were stimulated for 15 min and 24 h in IL-3 alone or in combination with IL-1β, IL-18, or IL-33. Whole cell lysates were then analyzed by Western blot.

Probing basophil lysates with anti-p38α and anti-p38β antibodies revealed that only the p38α isoform is present (data not shown). Basophils stimulated for 15 min with IL-18 or IL-33 showed a nearly threefold increase in p38α phosphorylation (Fig. 5A). After 24 h of stimulation, the phosphorylation of p38 by IL-18 or IL-33, compared with basophils incubated in only IL-3, was increased nearly fourfold (Fig. 5B). In contrast, basophils incubated with IL-1β showed p38α phosphorylation levels comparable with those cells stimulated with IL-3 alone. In addition, p38 activation is MyD88-dependent, as MyD88−/− basophils do not activate p38 upon IL-18 or IL-33 stimulation (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

IL-4 and IL-13 production from basophils is p38α-dependent. Basophils were stimulated for 15 min (A) and 24 h (B) in the indicated cytokines. Western blot analyses of basophil whole cell lysates were carried out using antibodies to total p38α and phosphotyrosine-specific p38 (p-p38α). Quantitation was performed by densitometry, and phospho-p38α was normalized to total p38α. Fold induction is relative to IL-3 stimulation alone. Blots are representative of three or four independent experiments, quantified in Supplemental Table 2A. (C) Basophils from wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 or MyD88−/− mice were stimulated in the indicated cytokine conditions for 15 min, and then whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot. Bands were quantified densitometrically, and phospho-p38 was normalized to total p38. Fold-induction is relative to IL-3 stimulation alone. Blots are representative of three independent experiments. (D) IL-4 and IL-13 production from basophils is reduced in the presence of the p38 inhibitor SB239063. Basophils were stimulated in the indicated cytokine conditions with or without SB239063 (500 nM). Results are the mean of three experiments ± sem (*, P<0.05).

To evaluate the effect of p38 inhibition, basophils were incubated with SB239063 (500 nM) for 1 h prior to cytokine addition (IL-18 or IL-33). Compared with cells never exposed to SB239063, inhibited cells show an ∼50% reduction in IL-4 production (Fig. 5D). IL-13 output was reduced by ∼80% for cells incubated in IL-33 and eliminated in cells stimulated with IL-18 (Fig. 5D). The reduction in cytokine production is not a result of inhibitor-induced cell death, as SB239063-treated cells show only a 5% decrease in survival as compared with cells not treated with the inhibitor (data not shown). Live and dead cells were quantified by flow cytometry using DAPI to identify dead cells.

In basophils, p38 is the only MAPK activated by IL-18 and IL-33. ERK is phosphorylated constitutively and equivalently in all cytokine conditions, including IL-3 alone (data not shown). JNK was not phosphorylated in any of the cytokine conditions. In keeping with these findings, chemical inhibition of JNK does not affect IL-4 or IL-13 output, and chemical inhibition of ERK results in significant cell death (data not shown).

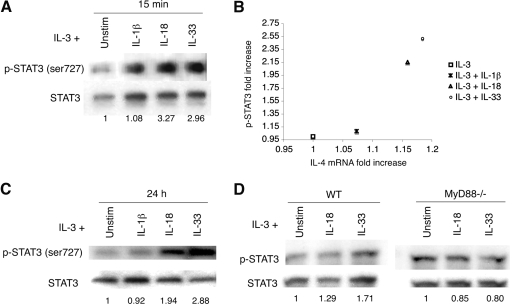

Up-regulation of STAT3 serine phosphorylation

Tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 is essential for its activation, and phosphorylation of serine 727 can regulate STAT3-mediated transcriptional activation and DNA binding [22]. Regulation of STAT3 phosphorylation by p38 has been described [23,24,25]. Furthermore, it has been reported that IL-18 activates STAT3 in NK cells [26]. Therefore, we investigated STAT3 phosphorylation in basophils stimulated with IL-1β, IL-18, or IL-33.

As STAT3 can be phosphorylated on tyrosine and serine, we examined each site separately by immunoprecipitation of basophil lysates. STAT3 was found to be constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated, even in the presence of IL-3 alone, and serine phosphorylation is induced only by IL-18 or IL-33 (data not shown). When basophils are stimulated with IL-1β, IL-18, or IL-33 for 15 min, total STAT3 protein and total serine-phosphorylated STAT3 increase as compared with IL-3 stimulation alone (Fig. 6A). This increase correlates with the enhanced IL-4 mRNA transcription observed after treating basophils with IL-1β, IL-18, or IL-33, respectively (Fig. 6B). However, after normalizing for total STAT3 protein in each cytokine stimulation condition, only basophils stimulated with IL-18 or IL-33 show up-regulated phosphorylation of STAT3 (Fig. 6A). A threefold increase in STAT3 phosphorylation is evident after 15 min of IL-18 or IL-33 stimulation. This threefold induction holds steady for 24 h after stimulation with IL-33 but decreases to twofold after stimulation with IL-18 (Fig. 6C). Although IL-1β-treated basophils experience a slight increase in phosphorylated STAT3 after 15 min, this increase is not observed at 24 h.

Figure 6.

Phosphorylation of STAT3. (A) Basophils were stimulated for 15 min with the indicated cytokines. Western blot analyses of basophil whole cell lysates were carried out using antibodies to total STAT3 and phosphoserine-specific STAT3. Quantitation was performed by densitometry, and phospho-STAT3 was normalized to total STAT3. Fold-induction is relative to IL-3 stimulation alone. Blots are representative of three independent experiments, quantified in Supplemental Table 2B. (B) The fold-increase in phospho-STAT3 after 15 min cytokine stimulations is graphed relative to the fold-increase in IL-4 mRNA transcripts after 15 min cytokine stimulations. For each, the fold-increase value is relative to IL-3 stimulation alone. Data points are calculated using the mean value from three independent experiments. (C) Basophils were stimulated for 24 h with the indicated cytokines. Western blot analyses of basophil whole cell lysates were carried out using antibodies to total STAT3 and phosphoserine-specific STAT3. Quantitation was performed by densitometry, and phospho-STAT3 was normalized to total STAT3. Fold-induction is relative to IL-3 stimulation alone. Blots are representative of three independent experiments, quantified in Supplemental Table 2B. (D) Basophils from wild-type C57BL/6 or MyD88−/− mice were stimulated in the indicated cytokine conditions for 15 min, and then whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot. Bands were quantified densitometrically, and phospho-STAT3 was normalized to total STAT3. Fold-induction is relative to IL-3 stimulation alone. Blots are representative of three independent experiments.

Notably, in MyD88−/− basophils, STAT3 phosphorylation decreases slightly in the presence of IL-18 and IL-33 (Fig. 6D). As MyD88−/− cells do not activate p38α, this would suggest that serine phosphorylation is induced by p38α in wild-type cells. When p38 is chemically inhibited in wild-type IL-18-stimulated basophils, STAT3 phosphorylation decreases fivefold, further indicating that serine phosphorylation is likely mediated by p38 (Supplemental Fig. 6). There is a small basal level of phosphorylated STAT3 in wild-type and MyD88−/− basophils in the presence of IL-3 alone. This could occur through a p38α-independent mechanism, or it is also possible that IL-3 leads to a small amount of p38α activation.

It is reported that STAT3 can increase Akt expression, thereby serving an antiapoptotic function [27]. Therefore, we investigated basophil survival and Akt activation after stimulation with the caspase-1-dependent IL-1 family cytokines.

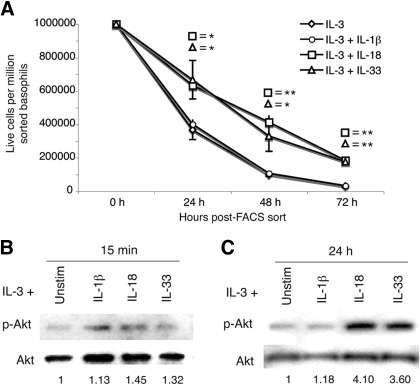

Enhanced basophil survival and increased Akt phosphorylation are evident after IL-18 or IL-33 stimulation

Basophils, purified by flow cytometric sorting, were incubated in the presence of IL-3 alone or IL-3 with IL-1β, IL-18, or IL-33. Cell survival was assessed by trypan blue exclusion after 24, 48, and 72 h in culture. Cells incubated in IL-18 or IL-33 survived significantly longer than basophils incubated in IL-1β or IL-3 alone (Fig. 7A). Cell survival increased twofold at 24 h, fourfold at 48 h, and sixfold at 72 h compared with cells incubated in IL-3 alone.

Figure 7.

Relative survival and Akt phosphorylation increases in the presence of IL-18 and IL-33. (A) Basophils were cultured in the indicated cytokine conditions and analyzed by trypan blue exclusion 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h post-FACS sort. Results are the mean of three experiments ± sem (*, P<0.05; **, P<0.01). Basophils were stimulated for 15 min (B) and 24 h (C) with the indicated cytokines. Western blot analyses of basophil whole cell lysates were carried out using antibodies to total Akt and phospho-Akt. Quantitation was performed by densitometry, and phospho-Akt was normalized to total Akt. Fold-induction is relative to IL-3 stimulation alone. Blots are representative of three independent experiments, quantified in Supplemental Table 2C.

When normalized to total Akt protein, Akt phosphorylation was increased in basophils stimulated for 15 min or 24 h in IL-18 or IL-33 (Fig. 7, B and C). Phosphorylation increased 1.3- to 1.4-fold after 15 min and rose to 3.6- to 4.1-fold after 24 h. Assessing whether Akt plays a role in IL-4 and IL-13 production using chemical inhibitors was not possible, as inhibition of PI3K/Akt with Wortmannin resulted in substantial (>90%) cell death (data not shown). This has also been observed in myeloid cells, where PI3K inhibition decreased cell survival and also partially reduced the phosphorylation of Bad [28]. Therefore, Akt is necessary for basophil survival, and enhanced activation of this protein induced by IL-18 and IL-33 correlates with increased basophil survival. However, nonspecific effects of inhibitor treatment on other PI3K-related enzymes cannot be ruled out.

No phosphorylation of Syk is evident, and no Zap70 is detected in basophils

In T cells, Zap70 can direct the autophosphorylation of p38α, independent of TRAF6, TAB1, or TAK1 [29]. However, p38 activation is not mediated by Syk or Zap70 in IL-18- or IL-33-stimulated basophils. Zap70 was not detectable in murine basophils by immunoblot, and there was no detectable phosphorylation of Syk using an anti-phospho-Syk antibody (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Basophils are a prominent source of IL-4 and IL-13. These cytokines are instrumental for the induction of Th2 immunity and are central effectors in allergy and asthma, promoting eosinophilia, airway hyper-responsiveness, and IgE class-switching [30]. Identification and characterization of the mediators and pathways leading to IL-4 and IL-13 production from basophils may lead to new treatments for Th2-related diseases.

The caspase-1-dependent IL-1 family cytokines play a complex and often contradictory role in the induction of Th2 responses. This complexity is evidenced further by the distinct effects that IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-33 have on basophil IL-4 and IL-13 production. IL-18 and IL-33, but not IL-1β, led to the secretion of IL-4 and IL-13 from basophils. These results are distinct from the reported effects of these IL-1 family cytokines on mast cells [14, 31]. In the absence of IgE, mast cells do not produce IL-4 after stimulation with any IL-1 family cytokine. In addition, although IL-33 prompts FcεRI-independent IL-13 production, IL-18 does not [14]. However, IL-1β or IL-18 can enhance IL-13 production in mast cells stimulated through the FcεRI receptor [14].

Receptors for IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-33 share several signaling components and often activate similar pathway proteins, including MyD88, IRAK, TRAF6, TAB1, and TAK1 [32]. As predicted by this model, IL-4 and IL-13 production from basophils mediated by IL-18 or IL-33 is MyD88-dependent. Similarly, IL-33 induced IL-13 production from mast cells by a MyD88-dependent pathway [14]. In contrast to the canonical signaling pathway, however, there was no detectable activation of IRAK1, TAB1, TAK1, or NF-κB in IL-18- or IL-33-stimulated basophils. Although these results were unexpected, signaling by IL-1 family members can also activate MAPK proteins and even act in an IRAK-independent manner. Although no prior studies have been carried out using basophils, mast cell studies have shown that IL-33 can activate p38, ERK, and NF-κB in mouse and human mast cells [3, 31]. Similarly, IL-18 signaling in human epithelial cells stably transfected with the IL-18Rβ chain activates p38 but not NF-κB [33]. Additionally, an IRAK-independent signaling pathway has been detected in NK cells in which IL-18 activates STAT3, p38, and ERK to produce IFN-γ [26]. We have found a similar activation profile in IL-18- and IL-33-treated basophils, which activate p38 and STAT3. However, in contrast to IL-18 signaling in NK cells, ERK is activated as a result of IL-3 cytokine stimulation.

IL-4 production from human basophils has been linked to the activation of p38 for IgE-dependent and -independent (fMLP or A23187) stimuli [34]. Furthermore, IgE-dependent signaling in basophils has been shown to involve PI3K, p38, and ERK but not JNK [35]. We have found that IL-18 and IL-33, but not IL-1β, induce the phosphorylation of p38α, which leads to IL-4 and IL-13 production. As with IgE-dependent signaling, the importance of p38α in IL-18- and IL-33-mediated IL-4 and IL-13 production is evident after chemical inhibition of p38α. Basophils treated with SB239063 prior to these IL-1 family cytokines show a significant reduction in IL-4 and IL-13 production. These results support the idea that p38 may be a therapeutic target for allergic diseases.

IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-33 increase IL-4 mRNA transcription in basophils. The relative increase in IL-4 mRNA corresponds to the relative increase in total serine-phosphorylated STAT3 (IL-33∼IL-18>IL-1β). This is consistent with prior studies showing that serine phosphorylation of STAT3 affects its ability to activate transcription. Transcriptional activation may enhance but does not directly induce or result from IL-4 or IL-13 production. This is illustrated by IL-1β-stimulated basophils, which demonstrated increased IL-4 mRNA transcription but failed to produce IL-4 or IL-13. Additionally, MyD88−/− basophils are transcriptionally competent but do not produce IL-4 or IL-13. Thus, IL-18 and IL-33 mediate IL-4 and IL-13 production from basophils at the translational and/or secretory level. These findings were supported by the increased potency of IL-18 and IL-33 in activating IL-4 release from basophils in vivo.

Akt activity is induced rapidly by IL-3 in the myeloid progenitor cell line 32D [36]. We have found this to be true also in basophils. Activated Akt is present in cells stimulated with IL-3 only or in combination with IL-1β, IL-18, or IL-33. However, after 24 h of cytokine stimulation, Akt activation is increased significantly only in the presence of IL-18 or IL-33, which also promote increased basophil survival. These results suggest that Akt activation is serving an antiapoptotic function in IL-18- and IL-33-treated cells. Although basophil survival is extended in the presence of IL-18 or IL-33, it is unaffected by IL-1β. In contrast, mast cell survival is extended in the presence of IL-33 and IL-1β but is unaffected by IL-18 [14].

Upon IL-18 or IL-33 stimulation, basophils use a MyD88-dependent pathway to activate p38α, leading to IL-4 and IL-13 production. However, the requisite signaling proteins downstream of MyD88 and upstream of p38α remain unknown. The lack of IRAK1, TAB1, and TAK1 phosphorylation indicates that the canonical IL-1 pathway is not present. Further studies will be required to elucidate the full scope of this pathway. Additionally, studies in vivo using models for allergic immunity will be necessary to assess the contributions of IL-18 and IL-33 to basophil release of IL-4 and IL-13 in primary states before IgE antibodies are produced and decorate the cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by AI026918 from the National Institutes of Health, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the SABRE Centre at UCSF. The authors thank the laboratory of Dr. A. Weiss for reagents, N. Flores for animal husbandry, and C. McArthur for expert technical assistance.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: APC=allophycocyanin, DAPI=4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, IRAK=IL-1R-associated kinase, m=murine, SAPK=stress-activated protein kinase, SCF=stem cell factor, TAB1=TAK-binding protein 1, TAK1=TGF-β-activated kinase 1, TRAF6=TNF-associated receptor factor 6, UCSF=University of California San Francisco

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

References

- Dinarello C A. Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood. 1996;87:2095–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daun J M, Fenton M J. Interleukin-1/Toll receptor family members: receptor structure and signal transduction pathways. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2000;20:843–855. doi: 10.1089/10799900050163217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan T K, Zurawski G, Moshrefi M, Qin J, Li X, Gorman D M, Bazan J F, Kastelein R A. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura H, Tsutsi H, Komatsu T, Yutsudo M, Hakura A, Tanimoto T, Torigoe K, Okura T, Nukada Y, Hattori K. Cloning of a new cytokine that induces IFN-γ production by T cells. Nature. 1995;378:88–91. doi: 10.1038/378088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima H, Takatsu K. Role of cytokines in allergic airway inflammation. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2007;142:265–273. doi: 10.1159/000097357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi K, Yoshimoto T, Tsutsui H, Okamura H. Interleukin-18 regulates both Th1 and Th2 responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:423–474. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumano K, Nalao A, Nakajima H, Hayashi F, Kurimoto M, Okamura H, Saito Y, Iwamoto I. Interleukin-18 enhances antigen-induced eosinophil recruitment into the mouse airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:873–878. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.3.9805026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild J S, Sigounas A, Sur N, Siddiqui M S, Alam R, Kurimoto M, Sur S. IFN-γ-inducing factor (IL-18) increases allergic sensitization, serum IgE, Th2 cytokines, and airway eosinophilia in a mouse model of allergic asthma. J Immunol. 2000;164:2701–2710. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohrs K, Wakil A E, Killeen N, Locksley R M, Mohrs M. A two-step process for cytokine production revealed by IL-4 dual-reporter mice. Immunity. 2005;23:419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto T, Tsutsui H, Tominaga K, Hoshino K, Okamura H, Akira S, Paul W E, Nakanishi K. IL-18, although antiallergic when administered with IL-12, stimulates IL-4 and histamine release by basophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13962–13966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghe B, Gevaert P, Holtappels G, Lukat K F, Lange B, Van Cauwenberge P, Bachert C. Up-regulation of IL-18 in allergic rhinitis. Allergy. 2002;57:825–830. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.23539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshikawa K, Kuroiwa K, Tago K, Iwahana H, Yanagisawa K, Ohno S, Tominaga S I, Sugiyama Y. Elevated soluble ST2 protein levels in sera of patients with asthma with an acute exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:277–281. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.2.2008120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshikawa K, Yanagisawa K, Tominaga S I, Sugiyama Y. Expression and function of the ST2 gene in a murine model of allergic airway inflammation. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:1520–1526. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.01494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho L H, Ohno T, Oboki K, Kajiwara N, Suto H, Iikura M, Okayama Y, Akira S, Saito H, Galli S J, Nakae S. IL-33 induces IL-13 production by mouse mast cells independently of IgE-FceRI signals. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:1481–1490. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min B, Paul W E. Basophils and type 2 immunity. Curr Opin Hematol. 2008;15:59–63. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3282f13ce8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi O, Kawai T, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Tsutsui H, Sakagami M, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity. 1998;9:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voehringer D, Shinkai K, Locksley R M. Type 2 immunity reflects orchestrated recruitment of cells committed to IL-4 production. Immunity. 2004;20:267–277. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H, Tsukidate T, Nakajima T, Okayama Y. Gene expression profiles of human mast cells and basophils. Clin Exp Allergy Rev. 2006;6:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Tschopp C M, Spiegl N, Didichenko S, Lutmann S, Julius P, Virchow J C, Hack C E, Dahinden C A. Granzyme B, a novel mediator of allergic inflammation: its induction and release in blood basophils and human asthma. Blood. 2006;108:2290–2299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-010348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund R, Vogelsang H, Machnik A, Herrmann D. Surface membrane antigen alteration on blood basophils in patients with hymenoptera venom allergy under immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:1190–1195. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.110928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessner A, Mohrs K, Mohrs M. Mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils acquire constitutive IL-4 and IL-13 transcripts during lineage differentiation that are sufficient for rapid cytokine production. J Immunol. 2005;174:1063–1072. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker T, Kovarik P. Serine phosphorylation of STATs. Oncogene. 2000;19:2628–2637. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkson J, Bowman T, Adnane J, Zhang Y, Djeu J Y, Sekharam M, Frank D A, Holzman L B, Wu J, Sebti S, Jove R. Requirement for Ras/Rac1-mediated p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling in Stat3 transcriptional activity induced by the Src oncoprotein. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7519–7528. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Bhattacharjee A, Roy B, Xu H-M, Anthony D, Frank D A, Feldman G M, Cathcart M K. Interleukin-13 induction of 15-lipoxygenase gene expression requires p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-mediated serine 727 phosphorylation of Stat1 and Stat3. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3918–3928. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.11.3918-3928.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollob J A, Schnipper C P, Murphy E A, Ritz J, Frank D A. The functional synergy between IL-12 and IL-2 involves p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and is associated with the augmentation of STAT serine phosphorylation. J Immunol. 1999;162:4472–4481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalina U, Kauschat D, Koyama N, Nuernberger H, Ballas K, Koschmieder S, Bug G, Hofmann W K, Hoelzer D, Ottmann O G. IL-18 activates STAT3 in the natural killer cell line 92, augments cytotoxic activity, and mediates IFN-γ production by the stress kinase p38 and by the extracellular regulated kinases p44erk-1 and p42erk-21. J Immunol. 2000;165:1307–1313. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Kim D, Kaneko S, Szewczyk K M, Nicosia S V, Yu H, Jove R, Cheng J Q. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human AKT1 promoter uncovers its up-regulation by the Src/Stat3 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38932–38941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid M P, Duronio V. Dissociation of cytokine-induced phosphorylation of Bad and activation of PKB/Akt: involvement of MEK upstream of Bad phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7439–7444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvador J M, Mittelstadt P R, Guszczynski T, Copeland T D, Yamaguchi H, Appella E, Fornace A J, Jr, Ashwell J D. Alternative p38 activation pathway mediated by T cell receptor−proximal tyrosine kinases. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:390–395. doi: 10.1038/ni1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townley R G, Horiba M. Airway hyperresponsiveness: a story of mice and men and cytokines. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2003;24:85–100. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:24:1:85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iikura M, Suto H, Kajiwara N, Oboki K, Ohno T, Okayama Y, Saito H, Galli S J, Nakae S. IL-33 can promote survival, adhesion and cytokine production in human mast cells. Lab Invest. 2007;87:971–978. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill L A, Greene C. Signal transduction pathways activated by the IL-1 receptor family: ancient signaling machinery in mammals, insects, and plants. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:650–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J-K, Kim S-H, Lewis E C, Azam T, Reznikov L L, Dinarello C A. Differences in signaling pathways by IL-1β and IL-18. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8815–8820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402800101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs B F, Plath K E S, Wolff H H, Grabbe J. Regulation of mediator secretion in human basophils by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase: phosphorylation is sensitive to the effects of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors and calcium mobilization. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:391–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs B F, Wolff H H, Zillikens D, Grabbe J. Differential role for mitogen-activated protein kinases in IgE-dependent signaling in human peripheral blood basophils: in contrast to p38 MAPK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase is poorly expressed and does not appear to control mediator release. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2005;136:329–339. doi: 10.1159/000084226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songyang Z, Baltimore D, Cantleydagger L C, Kaplan D R, Frankedagger T F. Interleukin 3-dependent survival by the Akt protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11345–11350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.