Abstract

IL-18 is a proinflammatory cytokine known to cause tissue injury by inducing inflammation and cell death. Increased levels of IL-18 are associated with myocardial injury after ischemia or infarction. IL-18-binding protein (IL-18BP), the naturally occurring inhibitor of IL-18 activity, decreases the severity of inflammation in response to injury. In the present study, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from mice transgenic for over expression of human IL-18BP were tested in rat models of global myocardial ischemia and acute myocardial infarction. Improved myocardial function is associated with production of VEGF, and in vitro, IL-18BP MSCs secreted higher levels of constitutive VEGF compared to wild-type MSCs. Whereas IL-18 increased cell death and reduced VEGF in wild-type MSCs, IL-18BP MSCs were protected. In an isolated heart model, intracoronary infusion of IL-18BP MSCs before ischemia increased postischemic left ventricular (LV) developed pressure to 79.5 ± 9.47 mmHg compared to 59.3 ± 7.8 mmHg in wild-type MSCs and 37.8 ± 5 mmHg in the vehicle group. Similarly, using a coronary artery ligation model, intramyocardial injection of IL-18BP MSCs improved LV ejection fraction to 67.8 ± 1.76% versus wild-type MSCs (57.4 ± 1.33%) and vehicle (39.2 ± 2.07%), increased LV fractional shortening 1.25-fold over wild-type MSCs and 1.95-fold over vehicle, decreased infarct size to 38.8 ± 2.16% compared to 46.4 ± 1.92% in wild-type MSCs and 60.7 ± 2.2% in vehicle, reduced adverse ventricular remodeling, increased myocardial VEGF production, and decreased IL-6 levels. This study provides the concept that IL-18BP genetically modified stem cells improve cardioprotection over that observed with unmodified stem cells.

Keywords: IL-1 family, inflammation, vascular endothelial growth factor

Stem cells are a promising therapeutic modality for myocardial ischemia (1). Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in particular have been shown to protect the heart from ischemic injury (2). It is unclear how much the benefit of MSCs is due to stem cell differentiation into cardiomyocytes or due to the paracrine signaling associated with stem cells (3, 4). However, a growing body of evidence indicates a relatively low rate of stem cell differentiation following transplantation, suggesting that the paracrine action of stem cells may be of greater importance to stem cell mediated cardioprotection (5, 6). Indeed, we have reported that preischemic infusion of MSCs into isolated rodent hearts improved myocardial function after 25 min of ischemia followed by 40 min of reperfusion, indicating that MSC cardiac protection is achieved acutely without cell differentiation (7).

The function and survival of transplanted MSCs are likely limited due to the inflammatory environment of the injured heart. However, genetic modification of MSCs may partially mitigate this problem. For example, MSCs engineered to overexpress myocardial protective factors such as VEGF and protein kinase B (Akt) exhibit significantly improved survival and enhanced cardiac protection (8, 9). Genetic modification of stem cells, therefore, may offer a means by which the protective characteristics of the stem cell can be optimized for clinical use.

Although recognized for its role with IL-12 in the induction of IFN gamma (IFNϒ), in the absence of IL-12 and other immunostimulatory cytokines, IL-18 is itself a uniquely proinflammatory cytokine (10) and participates in myocardial suppression and the atherosclerotic process (11, 12). In addition, IL-18 induces the Fas ligand causing cell death (13). Furthermore, increased IL-18 expression has been observed in the hearts subjected to ischemia (11, 14). Therefore, elevated levels of IL-18 following myocardial infarction (MI) may attenuate the protective effects of MSCs.

IL-18-binding protein (IL-18BP) is the naturally occurring inhibitor of IL-18 that exhibits a higher affinity for IL-18 than that of the IL-18 cell surface receptor (15). In fact, the balance between free IL-18 and IL-18BP affects the severity of some inflammatory diseases (16). Transgenic mice overexpressing human IL-18BP (IL-18BP Tg) produce high levels of bioactive IL-18BP in the circulation providing protection against inflammatory stimuli (17). However, it remains unknown whether stem cells engineered to overexpress IL-18 BP (IL-18BP MSCs) provide greater cardiac protection against ischemia compared to wild-type (WT) MSCs. Therefore, the purposes of this study were to determine whether overexpression of IL-18BP improves MSC function and enhances MSC-mediated cardiac protection after acute ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) or infarction.

Results

IL-18BP Counteracted the Down-Regulation of IL-18 on MSC VEGF Production.

Supernatants from WT and IL-18BP MSCs were analyzed for IL-18BP secretion. Levels of IL-18BP were undetectable in the WT MSC supernatants but high in IL-18BP MSC medium (13,611 ± 1,159 pg/mL). During acute myocardial ischemia, substantial amount of IFNγ is produced (18, 19). Therefore, we examined the effects of IFNγ on the induction of IL-18BP production in IL-18BP MSCs. In WT MSCs exposed to recombinant IFNγ, levels of IL-18BP secretion were still undetectable. In IL-18BP MSCs, however, 10 and 100 ng/mL, but not 1 ng/mL recombinant IFNγ increased IL-18BP production 1.28-fold (17,230 ± 1,035 pg/ml, P = 0.006) and 1.35-fold (18,134 ± 455 pg/mL, P < 0.001) over constitutive levels (13,450 ± 293 pg/mL), respectively. With respect to importance of VEGF in MSC-mediated protection, constitutive VEGF production was measured in WT and IL-18BP MSCs. Basal levels of VEGF production and VEGF mRNA were higher in IL-18BP MSCs compared to WT cells (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Constitutive VEGF expression in wild-type and IL-18BP MSCs. (A) Constitutive levels of VEGF secretion. After 24-h incubation, cell supernatants from wild-type and IL-18BP MSCs were collected and measured for VEGF levels by ELISA (Mean ± SEM, n = 3 individual experiments). (B) Steady-state mRNA levels of VEGF. Total RNA was isolated from wild-type and IL-18BP MSCs after 24-h incubation and analyzed for VEGF mRNA by RT real-time PCR. (Mean ± SEM, n = 4 individual experiments).

Although similar levels of basal IL-18 were measured in both lysates and supernatants from the WT and IL-18BP MSCs, incubation with exogenous IL-18 decreased VEGF production in WT MSCs (Table S1). In contrast to WT MSCs, VEGF production was unchanged in IL-18BP MSCs exposed to recombinant IL-18.

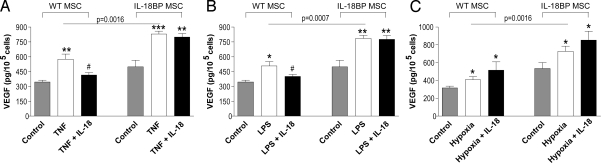

Effects of TNFα, LPS or Hypoxia on MSC VEGF Production.

Transplanted stem cells face a hostile environment to local TNFα and hypoxic conditions in ischemic tissues as well as to LPS during endotoxemia. Thus, we investigated the role of naturally produced IL-18 and these stresses with regard to MSC VEGF production. In WT MSCs, recombinant TNFα increased VEGF production 1.7-fold over constitutive levels (P = 0.004). In IL-18BP MSCs, constitutive production of VEGF was elevated compared to WT MSCs and when stimulated with TNFα, VEGF production increased further. These data suggest that endogenous IL-18 may be a negative regulator of TNFα-induced VEGF. Indeed, when recombinant IL-18 was added to TNFα-stimulated WT MSCs, there was a reduction in VEGF production. This reduction was not observed in IL-18BP MSCs (Fig. 2A). As shown in Fig. 2 B and C, similar differences were observed in LPS-treated MSCs as well as MSCs exposed to hypoxia. Thus, endogenous IL-18 appears to exert an inhibitory influence on VEGF production and constitutive production of IL-18BP by IL-18BP MSCs provides for neutralization of IL-18 and reversal of this inhibition.

Fig. 2.

VEGF production in wild-type and IL-18BP MSCs exposed to TNFα, LPS, or hypoxia. MSCs from wild-type and IL-18BP transgenic mice were stimulated with 50 ng/mL TNFα (A), 100 ng/mL LPS (B), or 1% O2–hypoxia (C) in the absence or presence of IL-18 (100 ng/mL). After 24 h of incubation, cell supernatants were collected for the measurement of VEGF production by ELISA. (Mean ± SEM, n = 3 individual experiments, *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 vs. control; #, P < 0.05 vs. TNF or LPS)

IL-18 Increased Apoptosis and Decreased MSC Proliferation.

Increased cytoplasmic levels of mono- and oligonucleosomes, indicators of apoptosis, were observed in WT MSCs after exposure to IL-18 for 24 and 48 h (Fig. S1A). In contrast, these levels did not change in IL-18-treated IL-18BP MSCs. A TUNEL assay also indicated that DNA fragments were more than two-fold higher in the WT MSCs after exposure to IL-18 but not in IL-18BP MSCs (Fig. S1 B and C). Similarly, decreased MSC proliferation was noted after 24 and 48 h incubation with IL-18 in WT MSCs but not in IL-18BP MSCs (Fig. S1D).

Effects of MAPKs on MSC Function after Exposure to IL-18.

In this study, activation of p38 MAPK (phosphorylated-p38 [p-p38]) was observed 2 h after incubation with IL-18 and was maintained until 6 h in WT MSCs (Fig. S2A Upper). However, phosphorylated p38 did not change in IL-18BP MSCs (Fig. S2A Lower). Adding a p38 inhibitor (SB 203580) to WT MSCs decreased IL-18-induced apoptosis (Fig. S2B). However, cell proliferation and VEGF production were not affected (Fig. S2 C and D).

ERK1/2 activation was decreased after 6 h of incubation with IL-18 in WT MSCs (Fig. 3A Upper). However, increased ERK1/2 activation at 2 h until 6 h was observed in IL-18BP MSCs in the presence of IL-18 (Fig. 3A Lower). Addition of an ERK1/2 inhibitor (328006) increased apoptosis by 44% and decreased cell proliferation, but did not affect VEGF production in IL-18BP MSCs (Fig. S3 B–D).

Fig. 3.

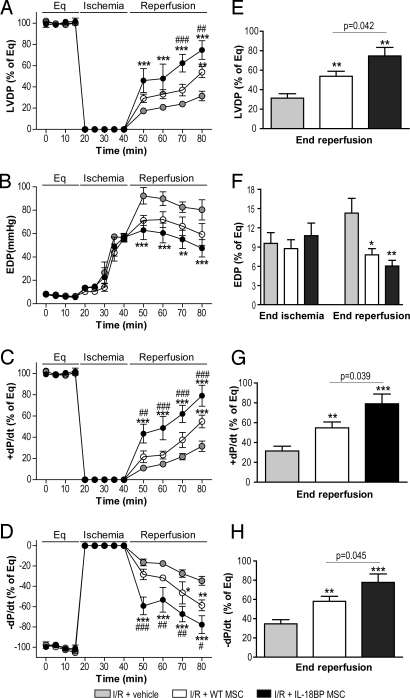

Effect of IL-18BP MSCs on postischemic myocardial function following acute global I/R. 1 × 106 MSCs from WT and IL-18BP Tg mice were infused over 1 min immediately before inducing global ischemia. The left ventricular function in vehicle (shaded, n = 6 rat hearts), WT MSCs (open, n = 5), and IL-18BP MSCs (solid, n = 6) is presented. Left ventricular function parameters over time included LVDP (% of equilibration [Eq], A), EDP (B), + dP/dt (% of Eq, C), and - dP/dt (% of Eq, D). Recovery at end reperfusion is indicated in bar graph form: LVDP (E), EDP (folds of Eq; F), + dP/dt (G), and - dP/dt (H). All results are reported as the mean ± SEM. (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 vs. I/R + vehicle; #, P < 0.05; ##, P < 0.01; ###, P < 0.001 vs. I/R + WT MSCs).

Increased IL-18 Levels after Myocardial Ischemia.

Global I/R increased myocardial IL-18 production 1.7-fold (14.3 pg/mg protein, P = 0.022) over normal hearts. In addition, higher levels of IL-18 production were noted in the at-risk area of heart tissue in the group of ischemia + vehicle (13.8 ± 0.95 pg/mg protein, P = 0.016) at 28 days post left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) ligation compared to sham group (8.1 ± 0.58 pg/mg protein).

IL-18BP Expression Increased Stem Cell-Mediated Cardioprotection after Global I/R.

We next tested the hypothesis that endogenous IL-18 exerts a detrimental effect on myocardial function. Using the Landgendorff isolated heart perfusion model, intracoronary infusion of WT MSCs before global I/R significantly increased post-ischemic recovery of myocardial function as exhibited by improved left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP), the maximal positive and negative values of the first derivative of pressure (+/- dP/dt) at end reperfusion (Fig. 3). Preischemic infusion of IL-18BP MSCs resulted in improved cardiac contractility and compliance following I/R compared to WT MSCs (P < 0.01). These protective effects of IL-18BP MSCs on myocardial function were observed during the early period of reperfusion as shown by increased recovery of +/- dP/dt at 10 min of reperfusion compared to WT MSCs (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3 C and D). These results demonstrated that IL-18BP MSCs provided a faster and greater protection of the myocardium from I/R. Notably, the value of end-diastolic pressure (EDP), an index of myocardial injury, progressively increased following ischemia and was similar in each of the three groups at the end of ischemia (Fig. 3F), indicating similar ischemia-induced injury. IL-18BP MSC pretreatment decreased the value of EDP during the reperfusion compared to vehicle group. This suggests that IL-18BP MSCs did not reduce ischemic injury, but rather protected the heart after endogenous IL-18 produced by the induction of ischemia or alternatively, the mechanism of protection may require more time to attain a measureable effect.

I/R induced proinflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 play an important role in worsening myocardial function, and therefore we measured myocardial production of these cytokines. Compared to I/R + vehicle, hearts infused with MSCs demonstrated lower levels of TNFα (Fig. S4A). However, infusion of IL-18BP MSC significantly decreased myocardial levels of TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6, and increased VEGF production following acute I/R (Fig. S4).

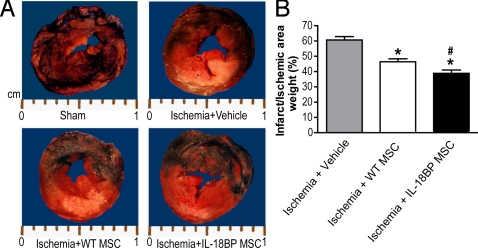

IL-18BP MSCs Enhanced Cardioprotection after Myocardial Infarction.

We next turned to a model of acute coronary occlusion and infarction. The effects of IL-18BP MSCs on cardioprotection were measured using an in vivo model in which the LAD was ligated to induce an MI. Twenty-eight days postoperatively, a visible difference in infarct size was noted among the vehicle, WT MSC and IL-18BP MSC groups (Fig. 4A), whereas the ischemic area (risk area + infarct area) caused by LAD was similar in these groups. Myocardial injection of WT MSCs decreased myocardial infarct size to 46.4% compared to vehicle 60.7%, with significantly further reduction to 38.8% in infarct size noted in the IL-18BP MSC group (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Effect of IL-18BP MSC on left ventricular infarct size after LAD ligation. Ten minutes after ligation, a solution of 100 μL PBS (vehicle), WT MSCs, or IL-18BP MSCs (1 × 107 cells/mL) was injected into the myocardium at two sites around the infarct border zone. (A) Representative transverse sections of rat hearts at 28 days post-LAD ligation in sham, ischemia + vehicle, ischemia + WT MSC and ischemia + IL-18BP MSC groups. The non-ischemic area (blue region) was stained with 2% Evans Blue Dye. The at-risk area (red region) was stained with 1% TTC. The infarct area (pale/white zone) did not stain with Evans or TTC. (B) The percentage of the infarct area weight to the ischemic area weight is represented. The results are the mean ± SEM. (n = 6 rats/group; *, P < 0.05 vs. ischemia + vehicle; #, P < 0.05 vs. ischemia + WT MSC).

Ventricular function as measured by left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) and fractional shortening (FS) was significantly improved in the MSC groups with greater protection provided by IL-18BP MSCs (Table 1). Improved myocardial function was also observed using the Langendorff model in which findings demonstrated greater cardiac function (LVDP and +/- dP/dt) in the IL-18BP MSC treatment group (Fig. 5).

Table 1.

Echocardiographic assessment of heart function, ventricular dimension, and wall thickness

| Sham (n = 5) | Ischemia + Vehicle (n = 13) | Ischemia + WT MSC (n = 12) | Ischemia + IL-18BP MSC (n = 12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF, % | 85.63 ± 2.10 | 39.19 ± 2.07*** | 57.43 ± 1.33***## | 67.84 ± 1.76***##††† |

| FS, % | 56.00 ± 2.60 | 20.22 ± 1.11*** | 31.51 ± 1.74***## | 39.29 ± 1.70***##†† |

| LVESD, mm | 2.34 ± 0.08 | 6.28 ± 0.20*** | 5.08 ± 0.23***## | 3.88 ± 0.24**##†† |

| LVEDD, mm | 6.08 ± 0.38 | 7.95 ± 0.22*** | 7.55 ± 0.33* | 6.74 ± 0.34# |

| AWTs, mm | 2.46 ± 0.11 | 1.08 ± 0.06*** | 1.25 ± 0.07*** | 1.47 ± 0.07***##† |

| AWTd, mm | 1.50 ± 0.12 | 0.80 ± 0.03*** | 0.86 ± 0.04*** | 1.03 ± 0.04***##†† |

| RWT | 0.46 ± 0.05 | 0.25 ± 0.01*** | 0.32 ± 0.01**# | 0.38 ± 0.02##† |

Data are mean ± SEM.

*, P < 0.05;

**, P < 0.01;

***, P < 0.001 vs. Sham;

#, P < 0.01;

##, P < 0.001 vs. Ischemia + Vehicle;

†, P < 0.05;

††, P < 0.01;

†††, P < 0.001 vs. Ischemia + WT MSC

Fig. 5.

Effect of IL-18BP MSCs on left ventricular function at 28 days post-LAD ligation. The left ventricular function was measured in the sham (n = 5), ischemia + vehicle (n = 6), ischemia + WT MSC (n = 6), and ischemia + IL-18BP MSC (n = 6) groups using isolated heart perfusion system. (A) LVDP, (B) + dP/dt, and (C) - dP/dt. The results are the mean ± SEM. (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001 vs. sham; #, P < 0.01; ##, P < 0.001 vs. ischemia + vehicle).

Ventricular remodeling was evident by the increased LV dimensions (end-diastolic/systolic diameter [LVEDD/LVESD]), decreased LV wall thickness (anterior wall thickness at end diastole/systole [AWTd/AWTs]), and decreased relative wall thickness (RWT). Although direct injection of WT MSCs improved primarily the LVESD and RWT parameters, all indices of detrimental LV remodeling were reduced in the IL-18BP MSC group (Table 1).

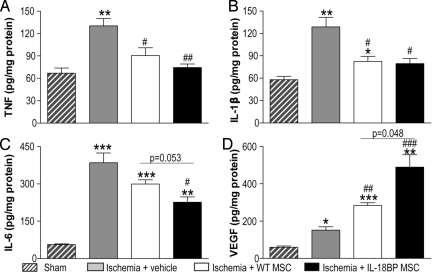

As shown in Fig. 6, LAD ligation increased myocardial TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels 28 days after the procedure. WT MSC treatment decreased levels of myocardial TNFα and IL-1β (Fig. 6 A and B); but injection of IL-18BP MSCs also reduced myocardial IL-6 levels (Fig. 6C). Similarly, myocardial VEGF levels were significantly higher in MSC-treated groups but further increased in the IL-18BP MSC group (Fig. 6D). Of note, following global I/R or LAD ligation, treatment with MSCs did not affect myocardial IL-10 production (Fig. S5), which has been shown to inhibit synthesis of TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6. This suggested that IL-10 is not responsible for the decreased production of proinflammatory cytokines observed in the IL-18BP MSC group.

Fig. 6.

Effect of IL-18BP MSC on myocardial cytokine production. Cardiac TNFα (A), IL-1β (B), IL-6 (C), and VEGF (D) at 28 days post-LAD ligation were presented. Heart tissue in the at-risk area was analyzed for cytokine production by ELISA in the sham (n = 3), ischemia + vehicle (n = 6), ischemia + WT MSC (n = 3) and ischemia + IL-18BP MSC groups (n = 4). The results are the mean ± SEM. (*, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 vs. sham, #, P < 0.05; ##, P < 0.01; ###, P < 0.001 vs. ischemia + vehicle).

Discussion

There is a growing recognition that ex vivo genetic modification of stem cells before transplant into myocardium may enhance survival of the donor cells as well affect host myocytes associated with increased neovascularization and improved cardiac function (8, 9, 20). Since IL-18 is a proinflammatory cytokine that induces Fas ligand (13), it would expect that endogenous IL-18 decreases the function and survival of MSCs and cardiomyocytes. IL-18BP is a naturally occurring inhibitor of IL-18 activity with an affinity greater than that of its receptor (15, 21). IL-18BP Tg mice were generated to overexpress human IL-18BP to study the biological and physiological effects of endogenous IL-18 in models of inflammation and autoimmunity (15, 17, 21). In the present study, we compared MSCs from WT and IL-18BP Tg mice to determine possible benefits of these genetically modified MSCs in the setting of myocardial I/R and infarction. The data demonstrated that: 1) IL-18BP MSCs constitutively secrete high levels of IL-18BP (13,611 pg/mL) associated with higher basal levels of VEGF compared to WT MSCs; 2) IL-18BP MSCs provided greater cardiac protection compared to WT MSCs in rodent models of global I/R and MI.

The IL-18BP modified stem cells may have provided increased cardioprotective effects via paracrine signaling. As previously reported, VEGF is a paracrine mediator of MSC-mediated cardiac protection (5, 7, 22). Delivery of MSCs into the ischemic myocardium increases local VEGF levels and thereby improves myocardial function (23). Bone marrow cells genetically modified to overexpress VEGF have also been reported to provide greater repair of cardiac function (8). Conversely, silencing VEGF in MSCs using siRNA abolished MSC-mediated cardioprotection in ischemic hearts (7).

In the present study, higher levels of constitutive as well as TNFα- and LPS-inducible VEGF production were observed in IL-18BP MSCs, indicating that these MSCs may provide greater protection against myocardial ischemia compared to WT MSCs. Indeed, improved myocardial function was observed in the IL-18BP MSC-treated group following acute I/R. In addition, enhanced cardioprotection was also observed in the MI model with myocardial implantation of IL-18BP MSCs compared to the WT MSC group. From previous studies, locally produced VEGF not only improves implanted stem cell survival but mediates cardiac protection by reducing apoptosis and decreasing proinflammatory cytokine production (8, 23, 24). Therefore, it was not unexpected that intramyocardial IL-18BP MSC injection improved MSC survival and provided protection in the ischemic hearts to a greater extent than WT MSCs.

After delivery/transplantation into ischemic myocardium, stem cells face a foreign, inflammatory environment that is detrimental toward their survival. IL-18 is constitutively expressed in various types of cells and is involved induction of apoptosis (13, 25). Elevated IL-18 levels have been observed in ischemic myocardium (11, 14). Indeed, our current study also indicated that ischemic injury was able to induce more myocardial IL-18 secretion. In addition, decreased cell proliferation and reduced VEGF production were observed in WT MSCs after exposing the cells to exogenous IL-18. Hence, MSCs modified to overexpress IL-18BP have greater resistance to the inflammatory/ischemic environment, confirmed by the findings that IL-18BP MSCs conferred greater benefit after global I/R. In addition, markedly increased LV function in the setting of MI and decreased infarct size were also observed.

During and after MI, the myocardium produces substantial amounts of proinflammatory cytokines including TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6. These proinflammatory cytokines lead to cardiomyocyte apoptosis, negative inotropy, and ventricular remodeling (26–29). In this study, myocardial ischemia increased levels of these cytokines while MSC treatment decreased myocardial TNFα and IL-1β levels. However, only IL-18BP MSCs significantly decreased myocardial IL-6, which has been demonstrated to increase adverse LV remodeling (30). Following MI observable changes occur in the shape and size of the LV including wall thinning in the infarct area, progressive ventricular chamber dilatation, and compensatory eccentric hypertrophy. These changes lead to increased wall stress, fibrosis of extracellular matrix, decreased contractility, and heart failure (31). Here, we found that LAD ligation resulted in increased LV dimensions and significant thinning of the ventricular wall. However, IL-18BP MSCs decreased LV dimensions and reduced scar formation in infarcted myocardium as exhibited by increased LV AWTs and AWTd. Therefore, IL-18BP MSCs may partially prevent some of the adverse remodeling of the heart through decreased myocardial IL-6.

Of note, IFNγ is a natural stimulant for IL-18BP production (32). Increased IFNγ levels have been observed in the sera and in the infarcted myocardium of patients with acute MI and other acute coronary syndromes (18, 19). It is possible that after MI, local and systemic IFNγ subsequently induces IL-18BP production and thereby increases IL-18BP leading to improved MSC-mediated cardiac protection. We demonstrated in this study that the WT MSCs did not provide the same extent of cardioprotection as did IL-18BP MSCs. This implies that the amount of naturally occurring IL-18BP is not sufficient to provide protection. Moreover, addition of recombinant IFNγ to IL-18BP MSCs further increased IL-18BP secretion, suggesting that IFNγ may improve the therapeutic potential of IL-18BP MSCs in the treating acute tissue injury. Therefore, the present study supports the using of genetically modified stem cells overexpressing IL-18BP or exogenous IL-18BP administration concurrent with stem cell therapy.

Materials and Methods

All animal studies conformed to the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (National Institutes of Health publication No. 85–23, revised 1996). The protocols were reviewed and approved by the Indiana Animal Care and Use Committee of Indiana University.

Cells, Cytokines, and Reagents.

A single-step purification method using adhesion to cell culture plastic was used as previously described (33). Mouse bone marrow MSCs were harvested from female 16 ± 2-week-old WT littermates and IL-18BP Tg mice (17). MSCs preferentially attached to the polystyrene surface; after 48 h, non-adherent cells in suspension were discarded. MSCs were measured for cluster of differentiation (CD) markers at passage 3 with flow cytometry. They were double negative for the hematopoietic markers CD34 and CD45 (>90%), and positive for the stem cell marker CD44 (>95%) (7). MSCs used in the experiments were limited to passages 5–7.

Recombinant rat IL-18 and LPS were from Sigma, recombinant human TNFα was from Millipore Corporation, and recombinant murine IFNγ was from Peprotech. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to p-p38 MAPK, p38 MAPK, p-ERK1/2, and ERK1/2 were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. GAPDH was from Biodesign International. The p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 and the ERK1/2 inhibitor 328006 were purchased from EMD Chemicals Inc.

Cell Culture Experiments

Cell Proliferation.

MSCs were plated in 96 microtiter wells (1,000 cells/well) and incubated for 24 and 48 h. Cell proliferation was analyzed using a 5-bromo-2′-deoxy-uridine labeling and detection kit (Roche Diagnostics Corporation).

Apoptosis.

MSC lysates were analyzed for apoptosis using a Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS kit (Roche Diagnostics) that detects mononucleosomes and oligonucleosomes. DNA fragmentation was also assessed in the 24-h incubation groups using a DeadEnd Fluorimetric TUNEL System (Promega Corporation). DAPI was used to stain the nuclei blue. Fluorescein-12-dUTP incorporation resulted in localized green fluorescence within the nucleus of only the apoptotic cells.

ELISA of IL-18, IL-18BP, and VEGF.

ELISA was performed using standard methodologies. Please see the SI Text for details.

Real-Time RT PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from WT and IL-18BP MSCs using RNA STAT-60 (TEL-TEST). Total RNA (0.1 μg) was reversed transcribed to cDNA using a Cloned AMV First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Real-time PCR was performed on the 7300 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using primers of 18S and VEGFa (Applied Biosystems).

Western Blotting.

Details of Western blot procedure and antibodies used can be found in the SI Text.

Animal Experiments

Isolated Rat Heart Experiments (Langendorff Model).

Hearts were isolated from male Sprague-Dawley rats (275–300 g) as previously described and were perfused in the isovolumetric Langendorff mode (70 mmHg) with paced at 350 bpm/min except during ischemia (7). Data were continuously recorded using a PowerLab 8 preamplifier/digitizer (AD Instruments Inc.) and an Apple G4 PowerPC computer (Apple Computer Inc.). For details and MSC infusion, please see the SI Text.

Myocardial Infarction Model.

Myocardial infarction was induced as previously described in the literature by ligating the LAD between the main pulmonary artery trunk and left atrial appendage (34). Please see the SI Text for details of procedures.

Myocardial Function and Dimensions.

Parasternal short-axis two-dimensional M-mode echocardiograms (VisualSonics Vevo-770) of the LV at the level of the papillary muscle were obtained in all animals on post-operative day 28. FS, EF, LVEDD/LVESD, AWTd/AWTs, and posterior wall thickness at end diastole (PWTd) were measured over three adjacent cardiac cycles. RWT was calculated according to the following formula: RWT = 2 × PWTd/LVEDD (35).

Isolated heart function was also evaluated using the Langendorff perfusion system as previously described (7).

Measurement of Infarct and At-Risk Areas.

The measurement of infarct size and risk area was performed as described previously (36). Intravenous injection of 1 mL of 2% Evans Blue Dye (Sigma) was used to identify the viable area of the myocardium. The heart was sectioned and incubated in 1% triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, Sigma). TTC stained the at-risk area of the myocardium red. The infarct size was calculated as the percentage of the infarct area weight to the ischemic area weight using the following formula: Infarct area weight/Ischemic area weight (%) = 100% × Σ infarct area weight of each slice/[Σ (risk area + infarct area weight of each slice)] (36).

Myocardial Cytokine Production.

Myocardial levels of rat IL-18, VEGF, TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 after acute I/R and in the at-risk area at post-operative day 28 were determined by ELISA (R&D Systems; Biosciences).

Presentation of Data and Statistical Analysis.

Data were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc Tukey test or Student's t test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Mr. Nicholas Vornehm (medical student), Mr. Randall Morgan (Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine), and the Fortune Fry MicroUltrasound Imaging Core for their expert technical assistance. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01GM070628 (to D.R.M.), R01HL085595 (to D.R.M.), K99/R00 HL0876077 (to M.W.), K08DK065892 (to K.K.M.), and R01AI015614 (to C.A.D.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0908924106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Crisostomo PR, Meldrum DR. Stem cell delivery to the heart: Clarifying methodology and mechanism. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2654–2656. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000288086.96662.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dai W, et al. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in postinfarcted rat myocardium: Short- and long-term effects. Circulation. 2005;112:214–223. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.527937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagaya N, et al. Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells improves cardiac function in a rat model of dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005;112:1128–1135. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.500447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson KA, et al. Regeneration of ischemic cardiac muscle and vascular endothelium by adult stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1395–1402. doi: 10.1172/JCI12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uemura R, Xu M, Ahmad N, Ashraf M. Bone marrow stem cells prevent left ventricular remodeling of ischemic heart through paracrine signaling. Circ Res. 2006;98:1414–1421. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000225952.61196.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balsam LB, et al. Haematopoietic stem cells adopt mature haematopoietic fates in ischaemic myocardium. Nature. 2004;428:668–673. doi: 10.1038/nature02460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markel TA, et al. VEGF is critical for stem cell-mediated cardioprotection and a crucial paracrine factor for defining the age threshold in adult and neonatal stem cell function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H2308–2314. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00565.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, et al. Combining pharmacological mobilization with intramyocardial delivery of bone marrow cells over-expressing VEGF is more effective for cardiac repair. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:736–745. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangi AA, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells modified with Akt prevent remodeling and restore performance of infarcted hearts. Nat Med. 2003;9:1195–1201. doi: 10.1038/nm912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura K, Okamura H, Wada M, Nagata K, Tamura T. Endotoxin-induced serum factor that stimulates gamma interferon production. Infect Immun. 1989;57:590–595. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.2.590-595.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mallat Z, et al. Evidence for altered interleukin 18 (IL)-18 pathway in human heart failure. FASEB J. 2004;18:1752–1754. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2426fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerdes N, et al. Expression of interleukin (IL)-18 and functional IL-18 receptor on human vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and macrophages: Implications for atherogenesis. J Exp Med. 2002;195:245–257. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsutsui H, et al. IFN-gamma-inducing factor up-regulates Fas ligand-mediated cytotoxic activity of murine natural killer cell clones. J Immunol. 1996;157:3967–3973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woldbaek PR, et al. Increased cardiac IL-18 mRNA, pro-IL-18 and plasma IL-18 after myocardial infarction in the mouse: A potential role in cardiac dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;59:122–131. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novick D, et al. Interleukin-18 binding protein: A novel modulator of the Th1 cytokine response. Immunity. 1999;10:127–136. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazodier K, et al. Severe imbalance of IL-18/IL-18BP in patients with secondary hemophagocytic syndrome. Blood. 2005;106:3483–3489. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fantuzzi G, et al. Generation and characterization of mice transgenic for human IL-18-binding protein isoform a. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:889–896. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0503230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garlichs CD, et al. Delay of neutrophil apoptosis in acute coronary syndromes. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:828–835. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0703358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naito K, et al. Differential effects of GM-CSF and G-CSF on infiltration of dendritic cells during early left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. J Immunol. 2008;181:5691–5701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dzau VJ, Gnecchi M, Pachori AS. Enhancing stem cell therapy through genetic modification. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1351–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SH, et al. Structural requirements of six naturally occurring isoforms of the IL-18 binding protein to inhibit IL-18. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1190–1195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye L, et al. Transplantation of nanoparticle transfected skeletal myoblasts overexpressing vascular endothelial growth factor-165 for cardiac repair. Circulation. 2007;116:I113–120. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.680124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang YL, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation induce VEGF and neovascularization in ischemic myocardium. Regul Pept. 2004;117:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinnaird T, et al. Local delivery of marrow-derived stromal cells augments collateral perfusion through paracrine mechanisms. Circulation. 2004;109:1543–1549. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124062.31102.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandrasekar B, et al. The pro-atherogenic cytokine interleukin-18 induces CXCL16 expression in rat aortic smooth muscle cells via MyD88, interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6, c-Src, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, Akt, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and activator protein-1 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26263–26277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502586200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meldrum DR. Tumor necrosis factor in the heart. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R577–595. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.3.R577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finkel MS, et al. Negative inotropic effects of cytokines on the heart mediated by nitric oxide. Science. 1992;257:387–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1631560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cain BS, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta synergistically depress human myocardial function. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1309–1318. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki K, et al. Overexpression of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist provides cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury associated with reduction in apoptosis. Circulation. 2001;104:I308–I303. doi: 10.1161/hc37t1.094871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirota H, Yoshida K, Kishimoto T, Taga T. Continuous activation of gp130, a signal-transducing receptor component for interleukin 6-related cytokines, causes myocardial hypertrophy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4862–4866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.St John Sutton M, et al. Cardiovascular death and left ventricular remodeling two years after myocardial infarction: Baseline predictors and impact of long-term use of captopril: Information from the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement (SAVE) trial. Circulation. 1997;96:3294–3299. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hurgin V, Novick D, Werman A, Dinarello CA, Rubinstein M. Antiviral and immunoregulatory activities of IFN-gamma depend on constitutively expressed IL-1alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5044–5049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611608104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peister A, et al. Adult stem cells from bone marrow (MSCs) isolated from different strains of inbred mice vary in surface epitopes, rates of proliferation, and differentiation potential. Blood. 2004;103:1662–1668. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Askari A, et al. Cellular, but not direct, adenoviral delivery of vascular endothelial growth factor results in improved left ventricular function and neovascularization in dilated ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1908–1914. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ono K, Matsumori A, Shioi T, Furukawa Y, Sasayama S. Cytokine gene expression after myocardial infarction in rat hearts: Possible implication in left ventricular remodeling. Circulation. 1998;98:149–156. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu BQ, et al. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke increases myocardial infarct size in rats. Circulation. 1994;89:1282–1290. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.3.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.